wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS: A Comprehensive Comparison for Pathogen Identification in Clinical and Research Applications

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection, yet the optimal choice of genetic material—whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA)—remains a critical methodological question.

wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS: A Comprehensive Comparison for Pathogen Identification in Clinical and Research Applications

Abstract

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection, yet the optimal choice of genetic material—whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA)—remains a critical methodological question. This article provides a definitive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals, synthesizing the latest evidence from 2025 and 2024. We explore the foundational principles of both approaches, detail their specific applications across diverse sample types like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and blood, and address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome challenges like high host DNA background. Finally, we present a rigorous validation and comparative analysis, evaluating the sensitivity, specificity, and clinical performance of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS for detecting bacteria, viruses, fungi, and intracellular pathogens, empowering informed methodological selection for diagnostic development and biomedical research.

Decoding the Core Technologies: An Introduction to wcDNA and cfDNA in mNGS

Whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) refers to the total genomic DNA extracted from intact microbial cells within a sample. Unlike microbial cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is derived from extracellular DNA fragments, wcDNA provides a comprehensive genetic snapshot of the viable microbial community, making it a fundamental component in metagenomic studies of host-associated and environmental microbiomes [1]. The analysis of wcDNA via metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) offers researchers a powerful tool for pathogen identification, microbial ecology studies, and therapeutic development by capturing genetic material from intact microorganisms.

The distinction between wcDNA and cfDNA is particularly crucial in microbiome research and clinical diagnostics, where understanding the source and representation of genetic material can significantly impact data interpretation. wcDNA extraction involves lysing intact cells to release genomic DNA, thereby representing the living microbial population at the time of sample collection [2]. This comprehensive representation makes wcDNA especially valuable for research requiring complete microbial profiling, including studies of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) where bacterial species such as Enterococcus faecium and Bifidobacterium spp. are enriched, and Escherichia coli with its associated antibiotic resistance genes are characteristic of Crohn's disease [3]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of wcDNA methodologies, extraction protocols, and performance characteristics relative to cfDNA alternatives for pathogen identification research.

Sourcing and Extraction of wcDNA

Whole-cell DNA can be sourced from diverse clinical and environmental samples, each presenting unique challenges and considerations for optimal DNA recovery. Common sources include:

- Bodily fluids: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), blood, saliva, urine, and other sterile body fluids [2] [1]. These samples typically contain inhibitors like heme or mucin that require specialized lysis approaches.

- Tissue samples: Liver, muscle, heart, brain, and other tissues often necessitate mechanical disruption through homogenization or bead beating due to their fibrous and tough nature [4].

- Stool samples: Provide access to complex gut microbial communities but require stabilization media to prevent degradation from environmental factors and bacterial growth [4] [3].

- Swab samples: Buccal or dry swabs that may contain high concentrations of bacteria and contaminants, requiring optimized drying, storage, and extraction protocols [4].

- Environmental samples: Filter membranes from water sources requiring specialized processing for long DNA fragment acquisition [5].

- Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples: Among the most challenging sources, requiring dewaxing and deparaffinization steps before nucleic acid access [4].

The selection of appropriate sample types directly impacts wcDNA yield and quality, with each source demanding tailored extraction approaches to address specific compositional characteristics and potential inhibitors.

Extraction Methodologies and Protocols

Effective wcDNA extraction follows a fundamental sequence: cellular lysis, binding or precipitation of DNA, washing of bound DNA, and elution or resuspension in a working buffer [4]. The following section details specific protocols and methodologies optimized for wcDNA recovery.

Standardized wcDNA Extraction from Body Fluids

For body fluid samples such as BALF, a standardized protocol yields high-quality wcDNA suitable for downstream mNGS applications [2] [1]:

- Sample Preparation: Begin with direct use of BALF sample without centrifugation.

- Mechanical Lysis: Add two 3-mm nickel beads to the sample and shake at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes to facilitate complete cell lysis.

- DNA Extraction: Use the Qiagen DNA Mini Kit according to manufacturer's protocol [2].

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA concentration and quality using spectrophotometric methods (e.g., Nanodrop) with optimal A260/A280 ratios typically ≥1.6 [4].

This method emphasizes mechanical disruption to ensure comprehensive cell lysis, particularly important for robust bacterial cell walls in microbial samples.

Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol Method for Environmental Samples

For environmental DNA samples preserved on filter membranes, an organic isolation method optimized for long fragment acquisition provides superior results [5]:

- Filter Preparation: Place ½ filter membrane in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube with 900 µL of Longmire buffer. For filters preserved in 96% ethanol, dry completely before transfer to Longmire buffer.

- Heat Shock Treatment: Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes, then cool to room temperature.

- Vortexing: Mix for 5-10 seconds to ensure homogenization.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add 9 µL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) for a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. Vortex for 30 seconds and incubate for 2 hours at 56°C.

- Organic Extraction:

- Add 800 µL of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, pH 8), vortex until homogenized, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 13,300 rpm.

- Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube containing 800 µL of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1), vortex, and centrifuge again.

- DNA Precipitation: Transfer the upper phase to a new tube, add 800 µL of isopropanol and 34 µL of 5M NaCl. Mix by inversion and incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Washing and Elution: Centrifuge for 30 minutes at 13,300 rpm, pour off the supernatant, wash with 800 µL of 80% iced ethanol, and repeat centrifugation. Dry the pellet and resuspend in 50-75 µL of ultrapure water at 37°C.

This method maximizes DNA recovery from challenging environmental samples while preserving fragment length, crucial for long-read sequencing technologies.

Magnetic Silica Bead-Based Rapid Extraction

Recent advancements have led to the development of SHIFT-SP (Silica bead-based High-yield Fast Tip-based Sample Prep), a magnetic bead-based method that significantly reduces extraction time while maintaining high yield [6]:

- Binding Optimization: Use lysis binding buffer (LBB) at pH 4.1 instead of pH 8.2 to enhance DNA binding to silica beads by reducing electrostatic repulsion.

- Tip-Based Binding: Employ pipette tip-based mixing (aspirating and dispensing repeatedly) for 1-2 minutes instead of orbital shaking, increasing binding efficiency from ~47% to ~85% for 100 ng input DNA.

- Bead Volume Adjustment: Utilize 30-50 µL of magnetic silica beads for higher DNA inputs (1000 ng), achieving 92-96% binding efficiency.

- Elution Conditions: Elute bound DNA using optimized buffers at appropriate pH and temperature to maximize recovery.

- Process Completion: Entire process requires only 6-7 minutes compared to 25-40 minutes for conventional column or bead-based methods [6].

This rapid, high-yield method is particularly valuable for clinical diagnostics where turnaround time is critical, and has demonstrated effectiveness with low microbial concentrations from enriched whole blood.

wcDNA Performance Comparison with cfDNA

Methodological Comparison and Detection Efficacy

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance characteristics of wcDNA and cfDNA for mNGS-based pathogen detection, revealing significant differences in their applications and effectiveness.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS Performance

| Performance Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host DNA Proportion | 84% [2] | 95% [2] | Lower host DNA in wcDNA improves microbial detection sensitivity |

| Concordance with Culture | 63.3% [2] | 46.7% [2] | wcDNA shows better alignment with gold standard methods |

| Detection Rate | 83.1% [1] | 91.5% [1] | cfDNA demonstrates superior overall detection capability |

| Fungi Detection | 19.7% exclusive detection [1] | 31.8% exclusive detection [1] | cfDNA more effective for fungal identification |

| Virus Detection | 14.3% exclusive detection [1] | 38.6% exclusive detection [1] | cfDNA superior for viral pathogen detection |

| Intracellular Microbes | 6.7% exclusive detection [1] | 26.7% exclusive detection [1] | cfDNA better for obligate intracellular pathogens |

| Bacterial Detection Consistency with Culture | 70.7% [2] | Not reported | wcDNA more reliable for bacterial pathogen detection |

| Sensitivity | 74.07% [2] | Not reported | Moderate sensitivity for pathogen detection |

| Specificity | 56.34% [2] | Not reported | Compromised specificity requires careful result interpretation |

The data reveals a fundamental divergence in application strengths: wcDNA mNGS demonstrates superior performance for bacterial detection with better concordance to culture methods, while cfDNA mNGS excels in detecting fungi, viruses, and intracellular microbes with low loads [2] [1].

Microbial Community Representation

The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA significantly influences the resulting microbial community profile and subsequent data interpretation in research settings.

Table 2: Microbial Community Representation in wcDNA vs. cfDNA

| Representation Aspect | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity Assessment | Represents intact cellular community | Skewed toward lysing or degrading organisms | wcDNA more accurate for viable community structure |

| Bacterial Pathogen Detection | Enhanced detection of abundant bacteria | May miss some intact bacteria | wcDNA preferable for bacterial infection studies |

| Low Load Microbe Detection | Lower sensitivity for microbes with low abundance | Higher sensitivity for fungi, viruses with low loads | Choice depends on target pathogen type |

| Antibiotic Resistance Gene Detection | Effective for associated resistance genes | May miss some intracellular resistance markers | wcDNA better for resistome analysis in bacterial pathogens |

| Functional Gene Analysis | Comprehensive genomic representation | Fragmented genetic information | wcDNA superior for functional potential assessment |

wcDNA provides a more accurate representation of the viable microbial community, as demonstrated in gut microbiome studies where wcDNA analysis revealed distinct bacteriome signatures between ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients, including enriched Enterococcus faecium in both diseases and Escherichia coli characteristic of CD [3]. This representation is crucial for understanding functional potential and microbial ecology in research settings.

Research Reagent Solutions for wcDNA Studies

Successful wcDNA extraction and analysis requires carefully selected reagents and kits optimized for different sample types and research objectives.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for wcDNA Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context | Sample Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiagen DNA Mini Kit | Standardized silica-column DNA purification | Routine wcDNA extraction from various samples | Body fluids, tissues, cultures [2] |

| MagMAX DNA Multi-Sample Ultra 2.0 | Magnetic bead-based DNA purification | High-throughput automated extraction | Blood, bone marrow, saliva, tissue [4] |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion for cell lysis | Enzymatic disruption of cellular structures | Tough samples (tissue, spores) [5] |

| Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol | Organic nucleic acid separation | Maximum DNA recovery, long fragments | Environmental samples, difficult tissues [5] |

| RNase A | RNA degradation | Reduction of RNA contamination | Tissue samples with high RNA content [4] |

| Lysis Binding Buffer (pH 4.1) | Enhanced DNA binding to silica | Magnetic bead-based rapid extraction | All sample types with low input DNA [6] |

| EDTA | Demineralization and nuclease inhibition | Bone samples and nuclease-rich samples | Forensic samples, ancient DNA, bone [7] |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Polyphenol binding | Plant samples with high polyphenols | Plant tissues, soil samples [4] |

Selection of appropriate reagents depends on sample characteristics, downstream applications, and throughput requirements. For clinical diagnostics with body fluids, optimized kits like the Qiagen DNA Mini Kit provide reproducibility, while research involving challenging samples may require specialized additives like PVP for plant materials or EDTA for demineralization of tough matrices [4] [7].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

wcDNA mNGS Experimental Workflow

The complete workflow for wcDNA-based metagenomic analysis involves multiple critical steps from sample collection to data interpretation, each requiring careful optimization to ensure representative microbial community data.

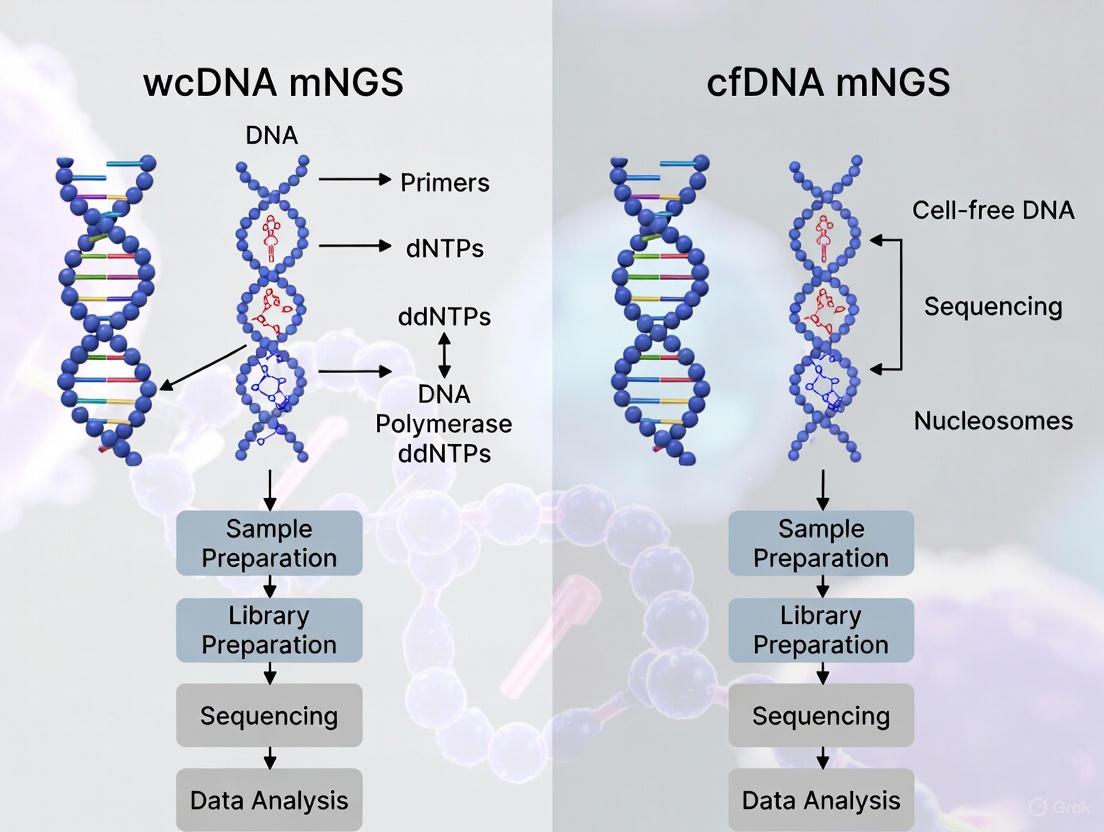

Figure 1: wcDNA mNGS Experimental Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process from sample collection to data interpretation, highlighting key steps including mechanical lysis and quality control specific to wcDNA analysis.

Method Selection Decision Pathway

Choosing between wcDNA and cfDNA approaches requires careful consideration of research goals, sample types, and target microorganisms, as each method offers distinct advantages for specific applications.

Figure 2: Method Selection Decision Pathway. This flowchart provides a systematic approach for selecting between wcDNA and cfDNA methods based on research objectives, sample characteristics, target microbes, and resource considerations.

Whole-cell DNA extraction and analysis represents a cornerstone approach in microbial metagenomics, providing researchers with a comprehensive tool for assessing viable microbial communities. The methodological comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that wcDNA mNGS offers distinct advantages for bacterial detection and community structure analysis, while cfDNA excels in identifying intracellular pathogens, fungi, and viruses with low microbial loads.

The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA methodologies should be guided by specific research objectives, sample types, and target microorganisms. For drug development professionals and clinical researchers, understanding these distinctions is crucial for appropriate experimental design and accurate data interpretation. As metagenomic technologies continue to evolve, the strategic application of wcDNA analysis will remain essential for advancing our understanding of microbiome dynamics in human health, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic development.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on reducing host DNA contamination in wcDNA extracts, enhancing sensitivity for low-abundance taxa, and streamlining automated workflows for high-throughput applications. By leveraging the appropriate extraction methodologies and analytical frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can maximize the research value of wcDNA in diverse microbiological studies.

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) refers to short fragments of extracellular nucleic acids circulating in bodily fluids such as blood plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Since its initial discovery in human blood by Mandel and Metais in 1948 [8] [9], cfDNA analysis has evolved into a powerful clinical tool across medical specialties. In infectious disease diagnostics, the application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to cfDNA has emerged as a particularly promising approach for pathogen identification, offering a non-invasive method to detect microbial sequences without the need for invasive tissue biopsies [9].

The fundamental distinction in mNGS testing approaches lies between microbial cell-free DNA (mcfDNA) sequencing and whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) sequencing. The wcDNA approach extracts genetic material from intact microorganisms and human cells in a sample, while cfDNA protocols specifically target extracellular DNA released into bodily fluids through various biological processes [2] [1]. Understanding the biological origins and characteristics of cfDNA is essential for optimizing its diagnostic application and interpreting results accurately within the context of pathogen detection.

Biological Origins of Cell-Free DNA

Primary Mechanisms of cfDNA Release

The pool of cfDNA in circulation originates through several distinct biological processes, with apoptosis and necrosis representing the most significant pathways.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is considered the primary source of circulating cfDNA in both healthy individuals and those with disease [8] [10]. This highly regulated process occurs continuously in the human body, with an estimated 50 to 70 billion cells undergoing apoptosis daily [8]. During apoptosis, caspase-activated DNase (CAD) and DNaseI L-3 enzymatically cleave nuclear DNA at internucleosomal linker regions, producing characteristic DNA fragments of approximately 167 base pairs in length—the size classically associated with mononucleosomes [8]. Recent genetic evidence from CRISPR screening studies has definitively confirmed apoptosis as a major mediator of cfDNA release, identifying genes involved in apoptotic processes as primary effectors [10].

Necrosis

In contrast to the controlled process of apoptosis, necrosis represents accidental cell death resulting from pathological insults such as ischemia, trauma, or toxicity. This unregulated process leads to cellular swelling and membrane rupture, releasing larger, more variable DNA fragments that often exceed 1000 base pairs in length [8] [10]. While these larger fragments are susceptible to rapid degradation by plasma nucleases, they nevertheless contribute to the circulating cfDNA pool, particularly in conditions involving significant tissue damage [8].

Other Contributing Mechanisms

Additional processes contribute to cfDNA populations, though to a lesser extent. Active secretion of DNA through extracellular vesicles represents a potential mechanism, though the exact significance remains debated [10]. Erythroblast enucleation during red blood cell maturation has also been hypothesized as a cfDNA source, though experimental evidence remains limited [8].

cfDNA Fragment Characteristics and Clearance

Regardless of origin, cfDNA fragments typically exist as double-stranded molecules ranging between 100-200 base pairs, though larger fragments have been reported [8]. Following release into circulation, cfDNA exhibits a remarkably short half-life, estimated between 16 minutes to 2.5 hours [11]. Clearance occurs primarily through degradation by plasma nucleases, with the liver, spleen, and kidneys also contributing to elimination [8]. This rapid turnover makes cfDNA an excellent dynamic biomarker for monitoring disease progression or treatment response.

Figure 1: Biological Origins and Clearance Pathways of Cell-Free DNA. This diagram illustrates the primary cellular sources of cfDNA, including apoptosis and necrosis, the characteristic fragment sizes produced by each mechanism, and the major clearance pathways that determine cfDNA half-life in circulation.

Comparative Analysis: wcDNA mNGS vs. cfDNA mNGS for Pathogen Detection

Technical Workflows and Methodological Considerations

The fundamental distinction between wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS approaches lies in sample processing and DNA extraction procedures.

wcDNA mNGS Protocol: This approach processes the entire clinical sample, typically employing mechanical (e.g., bead-beating) or enzymatic lysis to liberate genomic DNA from both host cells and intact microorganisms [2] [1]. The resulting DNA represents the complete genetic material present in the sample, including high molecular weight genomic DNA from viable organisms.

cfDNA mNGS Protocol: This method begins with centrifugation to generate a low-cellularity supernatant, followed by extraction of extracellular DNA from this supernatant using specialized kits designed to capture short nucleic acid fragments [2] [1]. This process selectively enriches for DNA released into bodily fluids through cell death or active secretion while depleting intact cellular material.

Figure 2: Comparative Workflows for wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS Testing. This diagram illustrates the distinct sample processing pathways for whole-cell DNA versus cell-free DNA metagenomic next-generation sequencing, highlighting key methodological differences from sample collection through library preparation.

Performance Comparison in Clinical Studies

Recent head-to-head comparisons have revealed significant differences in the diagnostic performance of wcDNA versus cfDNA mNGS approaches across various clinical scenarios and sample types.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of wcDNA mNGS vs. cfDNA mNGS in Body Fluid Samples

| Performance Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 74.07% | Not reported | Compared to culture in body fluid samples (n=125) [2] |

| Specificity | 56.34% | Not reported | Compared to culture in body fluid samples (n=125) [2] |

| Concordance with Culture | 63.33% (19/30) | 46.67% (14/30) | Direct comparison in 30 body fluid samples [2] |

| Host DNA Proportion | Mean 84% | Mean 95% (p<0.05) | Significantly lower host DNA in wcDNA [2] |

| Detection Rate in BALF | 83.1% | 91.5% | Pulmonary infections (n=130) [1] |

| Total Coincidence Rate in BALF | 63.9% | 73.8% | Compared to composite clinical diagnosis [1] |

Table 2: Pathogen-Type Detection Capabilities of wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS

| Pathogen Category | Exclusively Detected by wcDNA mNGS | Exclusively Detected by cfDNA mNGS | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | 19.7% (13/66) | 31.8% (21/66) | cfDNA superior for fungal detection [1] |

| Viruses | 14.3% (10/70) | 38.6% (27/70) | cfDNA superior for viral detection [1] |

| Intracellular Microbes | 6.7% (2/30) | 26.7% (8/30) | cfDNA better for obligate intracellular pathogens [1] |

| Consistency with 16S rRNA NGS | 70.7% (29/41) | Not reported | wcDNA shows better concordance with 16S method [2] |

The differential performance between these approaches reflects their fundamental biological distinctions. The wcDNA mNGS demonstrates strength in detecting a broad spectrum of pathogens, particularly extracellular bacteria, with higher concordance to traditional culture methods [2]. In contrast, cfDNA mNGS excels in identifying intracellular pathogens, fungi, and viruses, likely because these microorganisms release their nucleic acids into host circulation during infection or through host cell lysis [1].

Advantages and Limitations in Clinical Practice

Each approach presents a distinct profile of strengths and limitations that must be considered in diagnostic applications.

wcDNA mNGS Advantages: This method provides more comprehensive genomic information, potentially enabling strain-level characterization and detection of antimicrobial resistance genes due to the presence of intact microbial genomes [9]. It typically generates higher microbial reads per million (RPM), with one study reporting an average of 2,359 RPM for wcDNA versus 95 RPM for cfDNA [9]. The approach also demonstrates higher sensitivity for certain bacterial pathogens and better correlation with culture results for common microorganisms [2].

wcDNA mNGS Limitations: The presence of high levels of background host DNA (approximately 84% of total sequences) can reduce sensitivity for low-abundance pathogens unless host depletion strategies are employed [2] [9]. The extraction process may be harsher, potentially leading to DNA fragmentation, and the approach may be less effective for detecting pathogens that are primarily intracellular or that release their DNA into circulation [1].

cfDNA mNGS Advantages: This method excels for detecting intracellular pathogens, fungi, and viruses, with significantly higher exclusive detection rates for these categories of microorganisms [1]. The minimal invasiveness of blood-based testing enables serial monitoring of infection dynamics and treatment response. The approach also demonstrates higher overall detection rates in respiratory infections (91.5% vs. 83.1% for wcDNA) [1].

cfDNA mNGS Limitations: Microbial cfDNA typically represents an extremely small fraction of total cfDNA, creating challenges for detection and increasing vulnerability to contamination [9]. The fragmented nature of cfDNA limits opportunities for strain-level characterization or comprehensive resistance profiling. The approach shows lower concordance with culture results (46.67% vs. 63.33% for wcDNA) and may miss extracellular pathogens that do not release significant DNA into circulation [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Micro Kit [2] | Extraction of high-quality DNA from clinical samples | Both wcDNA & cfDNA |

| cfDNA Specialized Kits | VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit [2] | Optimized extraction of short cfDNA fragments | cfDNA mNGS |

| Library Preparation | QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit [1] | Library construction from low-input DNA | Both wcDNA & cfDNA |

| Host Depletion | Devin Microbial DNA Enrichment Kit [9] | Selective removal of human DNA to enhance microbial signal | Primarily wcDNA |

| Sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq platform [2] | High-throughput sequencing | Both wcDNA & cfDNA |

| Bioinformatics | Pavian, Bowtie2, Custom pipelines [2] [1] | Taxonomic classification, host sequence removal | Both wcDNA & cfDNA |

Clinical Applications and Future Directions

The complementary strengths of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS suggest context-specific applications in clinical practice. The wcDNA mNGS may be preferred for samples from sterile sites where comprehensive pathogen characterization is required, or when antimicrobial resistance profiling is clinically essential [9]. Conversely, cfDNA mNGS shows particular promise for blood-based testing in febrile immunocompromised patients, suspected deep-seated infections, and cases where intracellular pathogens are considered likely [1] [9].

In oncology, cfDNA analysis has established utility for non-invasive tumor profiling and monitoring, with applications now extending to infectious disease diagnostics [11] [12]. The high concordance between tumor mutations detected in tissue biopsies and plasma cfDNA (median 88% for oncogenic mutations) demonstrates the reliability of cfDNA-based approaches [12].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both techniques. Potential innovations include parallel sequencing of both fractions, optimized host-depletion strategies for wcDNA protocols, and targeted enrichment methods to enhance sensitivity for low-abundance pathogens in cfDNA assays. As our understanding of cfDNA biology deepens and sequencing technologies evolve, mNGS-based pathogen detection promises to play an increasingly central role in clinical microbiology and infectious disease diagnostics.

The comparative analysis of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS approaches reveals a complex landscape where each method offers distinct advantages depending on clinical context, suspected pathogen spectrum, and sample type. The wcDNA mNGS demonstrates higher sensitivity for bacterial detection and better concordance with conventional culture methods, while cfDNA mNGS excels in detecting intracellular pathogens, fungi, and viruses. Understanding the biological origins of cfDNA in apoptosis and necrosis provides crucial context for interpreting diagnostic results and optimizing test selection. As methodological refinements continue to enhance performance characteristics, both approaches will undoubtedly play increasingly important roles in the rapid, precise diagnosis of infectious diseases, ultimately supporting improved patient outcomes through targeted therapeutic interventions.

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection by providing a hypothesis-free approach to infectious disease diagnosis. This technology enables the simultaneous identification of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites directly from clinical samples without prior knowledge of the causative agent [13] [14]. The workflow encompasses a series of complex steps from sample collection to bioinformatic analysis, each critical for achieving accurate diagnostic results. Within this domain, a key methodological distinction exists between whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS, which sequences DNA from intact microbial cells, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS, which targets freely circulating microbial nucleic acids often from plasma [14]. This guide objectively compares these approaches, detailing their workflows, performance characteristics, and applications in pathogen identification research.

Wet Lab Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

Sample Collection and Processing

The initial phase of the mNGS workflow focuses on obtaining quality specimens while minimizing exogenous contamination. Appropriate sample collection varies significantly between wcDNA and cfDNA approaches.

Sample Types: Common specimens for wcDNA mNGS include bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum, tissue biopsies, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [15] [16]. These samples contain intact microorganisms. For cfDNA mNGS, blood collected in specialized cell-free DNA blood collection tubes is the primary source, enabling detection of pathogen nucleic acids released into the bloodstream [14].

Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extraction methods must be optimized for different sample matrices. The wcDNA protocol typically involves mechanical or enzymatic lysis of microbial cells followed by nucleic acid purification using commercial kits [15] [17]. The cfDNA approach requires specialized extraction to isolate short, fragmented nucleic acids from plasma while excluding longer genomic DNA [14].

Host Depletion and Library Preparation

Reducing host nucleic acid background is particularly crucial for wcDNA mNGS of low-biomass infections where microbial reads may be overwhelmed by host DNA.

Host Depletion Methods: Techniques include saponin lysis of host cells, differential centrifugation, filtration, and nuclease treatment [17] [18]. For example, one respiratory sample protocol uses 0.2% saponin treatment followed by filtration through 0.22 µm filters to remove host cells and debris [18].

Library Preparation: This process converts extracted nucleic acids into sequencing-ready libraries. Methods vary by platform:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mNGS Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Nucleic acid purification | Isolates DNA/RNA from samples | MatriDx MD013 [15] |

| MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Kit | Nucleic acid isolation | Concentrates pathogen nucleic acids | MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit [17] |

| Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit | Library preparation | Tags DNA with barcodes for multiplexing | SQK-RPB114.24 [17] |

| TURBO DNase | Host depletion | Degrades residual host DNA | TURBO DNase [18] |

| Agencourt AMPure XP beads | Library clean-up | Purifies and size-selects DNA fragments | Beckman Coulter AMPure XP [17] |

Sequencing Platforms

The choice between short-read and long-read technologies significantly impacts mNGS capabilities:

Illumina (Short-Read): Provides high accuracy (Q30 >85%) but shorter read lengths (2×150 bp to 2×300 bp) [19] [13]. Ideal for high-sensitivity pathogen detection and abundance quantification.

Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read): Generates longer reads (thousands of bases) with real-time sequencing capability, enabling rapid pathogen identification [13] [18]. The portable MinION device facilitates field deployment [14].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of mNGS data transforms raw sequencing reads into actionable pathogen identification through a multi-step process [19] [20].

Quality Control and Preprocessing

Initial processing ensures data integrity and removes low-quality sequences:

Quality Assessment: Tools like FastQC visualize read quality distributions, while MultiQC aggregates metrics across multiple samples [19]. Minimum thresholds typically require ≥85% of bases with Phred scores ≥30 (Q30) [19].

Adapter Trimming: Trimmomatic or KneadData remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases [19].

Host Sequence Removal: Alignment to host reference genomes (e.g., GRCh38) using Bowtie2, BWA, or Kraken2 eliminates residual host reads, significantly improving microbial detection sensitivity [19].

Taxonomic Classification and Functional Analysis

The core identification process involves comparing non-host reads to microbial databases:

Alignment-Based Methods: Kraken2 uses k-mer hashing for rapid taxonomic classification, while Bowtie2 provides precise alignment to reference genomes [19] [16].

Marker-Based Approaches: MetaPhlAn 4 leverages clade-specific marker genes for species-level precision [19].

Assembly-Based Methods: For novel pathogen discovery, de novo assembly with MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes reconstructs contigs and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) without reference databases [19] [20].

Functional Annotation: Tools like Prokka predict open reading frames, while specialized databases (* CAZy, *MEROPS, AMRFinderPlus) identify carbohydrate-active enzymes, proteases, and antimicrobial resistance genes [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of mNGS Platforms and Methods

| Parameter | wcDNA mNGS (BALF/Tissue) | cfDNA mNGS (Plasma) | Conventional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 56.5% for pulmonary infections [16] | 63% for CNS infections [14] | 39.1% for culture [16] |

| Turnaround Time | 24-72 hours [13] | 24-72 hours [14] | 3-5 days (culture) [13] |

| Pathogen Spectrum | Comprehensive (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) [15] [16] | Primarily bloodborne pathogens [14] | Target-specific |

| Host DNA Interference | High (requires depletion) [14] | Low (naturally enriched) [14] | Not applicable |

| Ability to Detect Co-infections | Excellent (7% additional cases) [18] | Moderate | Limited |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

wcDNA mNGS Protocol for Respiratory Samples

This protocol is adapted from clinical studies of pulmonary cryptococcosis and lower respiratory tract infections [15] [16]:

Sample Collection: Collect ≥5 mL BALF in sterile containers and transport on dry ice within 2 hours.

DNA Extraction: Use automated systems (e.g., MatriDx MAR002) with commercial kits (e.g., MatriDx MD013) following manufacturer protocols.

Library Preparation: Fragment DNA to 200-500 bp, ligate platform-specific adapters, and amplify with barcoded primers.

Sequencing: Load libraries onto Illumina (NextSeq500) or Nanopore (MinION) platforms to generate 10-20 million reads per sample.

Quality Control: Include negative (sterile water) and positive controls with spike-in molecules to monitor contamination and sensitivity.

cfDNA mNGS Protocol for Blood Samples

This protocol is adapted from liquid biopsy approaches for pathogen detection [14]:

Plasma Separation: Centrifuge blood collection tubes at 1600×g for 10 minutes within 2 hours of collection.

cfDNA Extraction: Use specialized cell-free DNA extraction kits to isolate short-fragment DNA from 1-5 mL plasma.

Library Construction: Employ unique molecular identifiers to distinguish true microbial signals from background noise.

Sequencing: Sequence to higher depth (20-30 million reads) to compensate for lower pathogen DNA concentration.

Bioinformatic Filtering: Apply stringent thresholds to distinguish circulating microbial DNA from contamination.

Performance Comparison and Applications

Diagnostic Performance Metrics

Clinical validation studies demonstrate the complementary strengths of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS approaches:

Sensitivity and Specificity: wcDNA mNGS shows superior sensitivity (56.5%) for localized respiratory infections compared to conventional methods (39.1%) [16]. cfDNA mNGS achieves 63% diagnostic yield in central nervous system infections where conventional methods fall below 30% [14].

Turnaround Time: mNGS significantly reduces time to results (1.00 day vs. 4.50 days for culture) and accelerates clinical decision-making (3.50 days vs. 9.00 days from admission) [15].

Co-infection Detection: mNGS identifies polymicrobial infections in 7% of cases missed by routine tests, including influenza C virus and Sapporovirus [18].

Unique Applications

wcDNA mNGS Applications:

cfDNA mNGS Applications:

- Disseminated and bloodstream infections

- Culture-negative sepsis

- Infections in critically ill patients

- Monitoring treatment response [14]

The mNGS workflow represents a paradigm shift in pathogen identification, offering unprecedented capabilities for comprehensive microbial detection. The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA approaches depends on clinical context, with wcDNA excelling in localized infections and cfDNA providing value for systemic illnesses. As sequencing technologies advance and bioinformatic tools become more sophisticated, mNGS is poised to become an integral component of precision infectious disease management, particularly for complex diagnostic challenges. Future developments in standardization, reimbursement models, and point-of-care applications will determine the broader implementation of these powerful diagnostic tools across diverse healthcare settings.

Comparative Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each DNA Source

The choice between whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as the optimal input for metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) in pathogen identification is a pivotal decision that significantly impacts diagnostic outcomes. Current research reveals that this choice is highly context-dependent, with each source demonstrating distinct advantages and limitations influenced by sample type, target pathogens, and laboratory workflow. wcDNA mNGS generally offers higher sensitivity for common bacterial pathogens in sterile body fluids. In contrast, cfDNA mNGS shows superior performance for detecting intracellular microbes, fungi, and viruses, particularly from samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these two methods to inform researcher selection for specific diagnostic scenarios.

Performance Data at a Glance

The following tables summarize key comparative findings from recent clinical studies across various sample types.

Table 1: Overall Diagnostic Performance Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Reference Standard | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Body Fluids (n=125) | Sensitivity | 74.07% | - | Culture | [2] |

| Specificity | 56.34% | - | Culture | [2] | |

| Concordance with Culture | 63.33% (19/30) | 46.67% (14/30) | Culture | [2] | |

| Pulmonary Infections (BALF, n=130) | Detection Rate | 83.1% | 91.5% | Conventional Methods + Clinical Diagnosis | [1] |

| Total Coincidence Rate | 63.9% | 73.8% | Conventional Methods + Clinical Diagnosis | [1] | |

| Non-Neutropenic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (BALF) | Clinical Value (AUC) | - | Superior to wcDNA | Conventional Microbiological Tests | [21] |

Table 2: Pathogen-Type Detection Capabilities

| Pathogen Type | Detection Capability | Key Findings | Sample Type | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi, Viruses, Intracellular Microbes | Higher with cfDNA mNGS | 31.8% of fungi, 38.6% of viruses, 26.7% of intracellular microbes detected only by cfDNA mNGS. | BALF | [1] |

| Gram-positive Bacteria | Variable; can be lower with cfDNA mNGS | In preservation fluids, mNGS (cfDNA-based) detected only 22.2% (2/9) of culture-positive Gram-positive bacteria. | Organ Preservation Fluids | [22] [23] |

| Atypical Pathogens | Effectively detected by mNGS | Mycobacterium, Clostridium tetanus, and parasites detected solely via mNGS. | Organ Preservation & Drainage Fluids | [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Understanding the methodological differences is crucial for interpreting performance data and selecting the appropriate protocol.

Core Protocol for wcDNA and cfDNA Extraction from Body Fluids

A seminal study comparing both methods on the same 125 clinical body fluid samples (pleural, pancreatic, drainage, ascites, and CSF) detailed the following protocol [2]:

- Sample Processing: A 30-minute centrifugation at 20,000 × g separates the cellular pellet from the cell-free supernatant.

- wcDNA Extraction:

- The retained precipitate is subjected to mechanical lysis (e.g., bead beating).

- DNA is then extracted from the lysed pellet using a commercial kit (e.g., Qiagen DNA Mini Kit).

- cfDNA Extraction:

- Cell-free DNA is extracted from the supernatant (e.g., 400 μL) using a specialized circulating DNA kit (e.g., VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit).

- This typically involves proteinase K digestion, binding to magnetic beads, washes, and elution.

Workflow Comparison

The diagram below illustrates the key procedural differences between the wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS pathways.

Advanced Workflow: Integrated Host Depletion for wcDNA

A significant limitation of wcDNA mNGS is high background host DNA. A 2025 study evaluated a novel Zwitterionic Interface Ultra-Self-assemble Coating (ZISC)-based filtration device for host depletion prior to DNA extraction [24].

Protocol Enhancement [24]:

- Host Cell Depletion: Whole blood is passed through the ZISC filter, achieving >99% white blood cell removal while allowing unimpeded passage of bacteria and viruses.

- Microbial Enrichment: The filtered sample is centrifuged to obtain a microbial cell pellet.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: DNA is extracted from this enriched pellet for subsequent library preparation and sequencing.

Key Finding: This gDNA-based workflow with pre-extraction host depletion detected all expected pathogens in 100% (8/8) of clinical sepsis samples, with a tenfold increase in microbial read counts compared to unfiltered gDNA-based mNGS, and outperformed cfDNA-based mNGS in consistency [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for mNGS Workflows

| Product Name | Function in Workflow | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Qiagen DNA Mini Kit | Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from cellular pellets. | Standard for wcDNA extraction from various sample types [2]. |

| VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit | Optimized extraction of short-fragment, low-concentration cfDNA from supernatant/plasma. | Critical for obtaining usable cfDNA templates [2]. |

| QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Prep Kit | Library construction from minimal DNA input, preserving complexity. | Suitable for both wcDNA and cfDNA libraries where input is limiting [1] [21]. |

| ZISC-Based Filtration Device (e.g., Devin) | Pre-extraction physical depletion of host white blood cells from whole blood. | Dramatically improves signal-to-noise ratio in gDNA-based mNGS for sepsis [24]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Post-extraction enzymatic depletion of host DNA via differential lysis. | An alternative method for host depletion in complex samples [24]. |

The evidence clearly indicates that neither wcDNA nor cfDNA mNGS is universally superior. The optimal choice is a strategic decision based on the clinical or research question, target pathogen, and sample matrix.

- Choose wcDNA mNGS when investigating sterile body fluid infections (e.g., abdominal), especially when targeting common bacteria, and when the workflow can be coupled with effective host depletion methods to maximize sensitivity [2] [24].

- Choose cfDNA mNGS when dealing with pulmonary infections, particularly when fungi, viruses, or intracellular pathogens (like Mycobacterium tuberculosis) are suspected, or when the pathogen load in the sample is expected to be low [1] [25] [21].

For the most critical and challenging cases, a dual approach utilizing both DNA sources may provide the most comprehensive diagnostic picture, leveraging the unique strengths of each method to overcome their respective limitations. The ongoing development of host depletion techniques continues to shift the performance landscape, making wcDNA an increasingly powerful option for blood-based diagnostics.

The Impact of Host DNA Background on Sequencing Efficiency and Diagnostic Yield

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a powerful, hypothesis-free tool for pathogen detection in clinical infectious diseases. However, its effectiveness is significantly challenged by the presence of host DNA, which can constitute up to 95-99% of the total DNA in clinical samples [2] [26]. This high host DNA background consumes valuable sequencing throughput and reduces the microbial reads available for analysis, ultimately compromising diagnostic sensitivity. Two primary approaches have been developed to address this challenge: whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS, which sequences all DNA in a sample, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS, which specifically targets freely circulating microbial DNA fragments. This review comprehensively compares these approaches, examining their performance characteristics across different sample types and clinical scenarios to guide researchers and clinicians in test selection and optimization.

Core Concepts: wcDNA versus cfDNA mNGS

Whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS involves extracting and sequencing the complete genomic content from a clinical sample, including both intact microbial cells and human host cells. This method captures intracellular and cell-associated pathogens but also co-extracts substantial host genomic DNA, which can dominate sequencing libraries [2] [26]. Specialized host depletion strategies, such as filtration or differential lysis, can be applied to wcDNA samples to enrich microbial content before sequencing [27] [9].

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS targets short fragments of DNA (typically <300 bp) circulating in biofluids like plasma or supernatant from centrifuged samples. These fragments are released through processes such as apoptosis, necrosis, or pathogen lysis [9]. This approach inherently avoids the high host DNA background associated with intact cells but faces different challenges related to low absolute quantities of microbial cfDNA (mcfDNA) in samples [9] [28].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS Approaches

| Characteristic | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS |

|---|---|---|

| Source Material | Precipitate/cell pellet after centrifugation | Supernatant/plasma after centrifugation |

| DNA Targets | Intact microbial genomes, host genomic DNA | Microbial and host DNA fragments |

| Typical Host DNA Percentage | ~84% in body fluids [2] | Can exceed 95% [2] |

| Key Advantage | Captures intracellular pathogens; amenable to host depletion | Minimizes interference from human cells; reflects active infection |

| Primary Challenge | High host DNA background requiring depletion methods | Very low concentration of microbial targets |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two approaches:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Diagnostic Performance Across Sample Types

Multiple clinical studies have directly compared the diagnostic performance of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS across various sample matrices, with results demonstrating significant context-dependent performance.

Table 2: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS

| Sample Type | Performance Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Fluids (n=125) | Concordance with culture | 63.33% (19/30) | 46.67% (14/30) | [2] |

| Sensitivity | 74.07% | Not reported | [2] | |

| Specificity | 56.34% | Not reported | [2] | |

| BALF (n=130) | Detection rate | 83.1% | 91.5% | [1] [29] |

| Total coincidence rate | 63.9% | 73.8% | [1] [29] | |

| Blood (culture-positive sepsis, n=8) | Pathogen detection rate | 100% (8/8) | Inconsistent sensitivity | [27] |

| Average microbial RPM | 9,351 (with filtration) | 95-1,488 | [27] [9] |

In body fluids, wcDNA mNGS demonstrated superior concordance with culture results (63.33% vs. 46.67%) and a sensitivity of 74.07%, though with compromised specificity (56.34%) [2]. Conversely, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from patients with pulmonary infections, cfDNA mNGS showed significantly higher detection rates (91.5% vs. 83.1%) and total coincidence with clinical diagnoses (73.8% vs. 63.9%) [1] [29].

For blood samples from sepsis patients, gDNA-based mNGS (equivalent to wcDNA) with host depletion filtration detected all expected pathogens with an average of 9,351 microbial reads per million (RPM), over tenfold higher than cfDNA-based methods (95-1,488 RPM) [27] [9].

Pathogen-Type Detection Capabilities

The performance of each method varies significantly depending on the type of pathogen targeted, reflecting biological differences in pathogen localization and DNA release.

Table 3: Pathogen-Type Detection Performance

| Pathogen Type | wcDNA mNGS Performance | cfDNA mNGS Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | Detected 45/60 species in BALF [1] | Detected 60/60 species in BALF; 31.8% exclusively by cfDNA [1] | cfDNA superior for low-load fungi |

| Viruses | Detected 43/53 species in BALF [1] | Detected 53/53 species in BALF; 38.6% exclusively by cfDNA [1] | cfDNA superior for viral detection |

| Intracellular Bacteria | Limited detection for some species [1] | 26.7% detected exclusively by cfDNA in BALF [1] | cfDNA better for intracellular microbes |

| General Bacteria | 70.7% consistency with culture in body fluids [2] | Lower consistency vs. culture (46.67%) [2] | wcDNA superior for standard bacterial detection |

In BALF samples, cfDNA mNGS demonstrated particular advantages for detecting fungi (31.8% detected exclusively by cfDNA), viruses (38.6% exclusive to cfDNA), and intracellular microbes (26.7% exclusive to cfDNA) [1]. These patterns suggest cfDNA may be more effective for pathogens that reside intracellularly or release DNA fragments into biofluids.

Impact of Host DNA and Sequencing Depth

The proportion of host DNA in a sample directly impacts the sequencing depth required for adequate microbial genome coverage. Research shows that as host DNA percentage increases, sensitivity for detecting low-abundance microorganisms decreases significantly, particularly when sequencing depth is compromised [26]. Samples with 90% host DNA require substantially deeper sequencing to achieve comparable sensitivity to samples with lower host DNA content [26].

Host depletion techniques applied to wcDNA samples can dramatically improve microbial recovery. One study utilizing a Zwitterionic Interface Ultra-Self-assemble Coating (ZISC)-based filtration device achieved >99% white blood cell removal, reducing host DNA background and increasing microbial reads from 925 RPM to 9,351 RPM in clinical blood samples - a tenfold enrichment [27]. This approach significantly enhanced the sensitivity of gDNA-based mNGS, enabling 100% detection of pathogens in culture-positive sepsis samples [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflows for wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS

The methodological differences between wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS begin at the sample processing stage and extend through library preparation:

cfDNA mNGS Protocol:

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge clinical sample (e.g., BALF, blood) at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes [2]

- DNA Extraction: Extract cfDNA from 400 μL supernatant using specialized kits (e.g., VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit) [2]

- Library Preparation: Use ultra-low input library prep kits (e.g., QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit) [1] [29]

- Sequencing: Sequence on platforms such as Illumina NextSeq 550 or NovaSeq with ~26 million reads per sample [2]

wcDNA mNGS Protocol:

- Sample Processing: Retain precipitate after centrifugation; add beating beads for mechanical lysis [2]

- Optional Host Depletion: Apply filtration (e.g., ZISC-based filter) or other depletion methods [27]

- DNA Extraction: Extract wcDNA from precipitate using standard kits (e.g., Qiagen DNA Mini Kit) [2]

- Library Preparation: Prepare libraries using standard DNA library prep kits (e.g., VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit) [2]

- Sequencing: Sequence on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq with ~26 million reads per sample [2]

Host Depletion Techniques

For wcDNA mNGS, various host depletion strategies can significantly improve microbial signal:

- Filtration-based methods: Novel devices like the ZISC-based filter physically remove host cells while allowing microbes to pass through, achieving >99% white blood cell depletion [27]

- Differential lysis: Kits such as the QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit selectively lyse human cells before microbial cell lysis [27]

- Methylation-based depletion: Techniques like the NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit target CpG-methylated host DNA for removal [27]

These methods reduce host DNA background from >95% to more manageable levels, dramatically increasing microbial read counts and improving detection sensitivity for low-abundance pathogens [27] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS requires specific reagent systems optimized for different sample types and applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for mNGS Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit (Vazyme) [2] | Extracts short DNA fragments from supernatant/plasma |

| wcDNA Extraction Kits | Qiagen DNA Mini Kit [2] | Extracts genomic DNA from cell pellets |

| Ultra-Low Input Library Prep | QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit (QIAGEN) [1] [29] | Constructs sequencing libraries from minimal DNA input |

| Standard DNA Library Prep | VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit (Vazyme) [2] | Prepares sequencing libraries from sufficient DNA inputs |

| Host Depletion Filters | ZISC-based filtration device (Micronbrane) [27] | Physically removes host cells from whole blood samples |

| Differential Lysis Kits | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Qiagen) [27] | Selectively lyses human cells before microbial lysis |

| Methylation-Based Depletion | NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit (NEB) [27] | Removes CpG-methylated host DNA via magnetic beads |

Integrated Analysis and Future Directions

The comparative data reveals that neither wcDNA nor cfDNA mNGS is universally superior; instead, they offer complementary strengths. wcDNA mNGS, particularly when coupled with effective host depletion strategies, demonstrates excellent performance for bacterial detection in body fluids and blood [2] [27]. Conversely, cfDNA mNGS shows distinct advantages for detecting viruses, fungi, and intracellular pathogens in respiratory samples [1] [29].

This synergy suggests that a combined approach may optimize diagnostic yield. One clinical study evaluating both methods in parallel found that integrating cfDNA and cellular DNA mNGS results achieved higher diagnostic efficacy (ROC AUC: 0.8583) than either method alone (cfDNA AUC: 0.8041; cellular DNA AUC: 0.7545) [28].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on enhancing host depletion efficiency for wcDNA protocols and improving sensitivity for low-abundance mcfDNA in cfDNA approaches. Additionally, standardized bioinformatics pipelines and reporting criteria are needed to ensure consistent interpretation across laboratories and sample types [2] [30]. As sequencing costs continue to decline and methodologies refine, dual-mode mNGS testing may become increasingly feasible for challenging diagnostic scenarios where conventional methods have failed.

Strategic Application: Selecting wcDNA or cfDNA mNGS for Different Clinical Specimens and Pathogens

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection by enabling unbiased identification of microorganisms without prior knowledge of the causative agent. Within this field, a critical methodological consideration is the choice between whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) approaches for optimal diagnostic yield. wcDNA mNGS targets intact microbial cells and intracellular pathogens through DNA extraction from pelleted samples or tissue homogenates, whereas cfDNA mNGS sequences extracellular DNA released from lysed cells into body fluids. Understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and optimal applications of wcDNA mNGS is essential for researchers and clinicians seeking to implement this technology effectively in infectious disease diagnostics. This guide synthesizes current evidence to objectively compare wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS approaches, with particular emphasis on sample type selection to maximize detection sensitivity and specificity across diverse clinical scenarios.

Performance Comparison: wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS

Recent comparative studies reveal distinct performance profiles for wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS across different sample types and pathogen categories. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from clinical evaluations:

Table 1: Overall diagnostic performance of wcDNA vs. cfDNA mNGS

| Performance Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Combined Approach | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 74.07% | Not reported | Higher than individual methods | Body fluids (n=125) [2] |

| Specificity | 56.34% | Not reported | Not reported | Body fluids (n=125) [2] |

| Concordance with culture | 63.33%-70.7% | 46.67% | Not reported | Body fluids (n=30-41) [2] |

| Detection rate | 83.1% | 91.5% | Not reported | BALF (n=130) [1] |

| ROC AUC | 0.7545 | 0.8041 | 0.8583 | Body fluids (n=248) [31] [28] |

| Limit of Detection | 27-466 CFU/mL | 9.3-149 GE/mL | Not reported | Laboratory validation [31] |

Performance by Pathogen Type

The effectiveness of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS varies significantly depending on the microbial category:

Table 2: Performance comparison by pathogen type

| Pathogen Category | wcDNA mNGS Advantages | cfDNA mNGS Advantages | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Superior detection in high-host background samples [31] | Lower host DNA proportion improves detection sensitivity | Abdominal infections, sterile body fluids [2] [31] |

| Fungi | 19.7% exclusively detected | 31.8% exclusively detected | Pulmonary infections [1] |

| Viruses | Limited detection capability | Excellent detection (ROC AUC: 0.9814 in blood) [31] | Bloodstream infections [31] |

| Intracellular Microbes | 6.7% exclusively detected | 26.7% exclusively detected | Pulmonary infections [1] |

Performance by Sample Type

The optimal choice between wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS is heavily influenced by the sample matrix being tested:

Table 3: Performance across sample types

| Sample Type | Recommended Method | Rationale | Study Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | cfDNA preferred | Higher detection rate (91.5% vs 83.1%) and total coincidence rate (73.8% vs 63.9%) | Pulmonary infections (n=130) [1] |

| High Host-Background Samples | wcDNA superior | Better performance in samples with abundant human DNA | Body fluids [31] |

| Blood | cfDNA superior | Optimal for viral detection (ROC AUC: 0.9814) | Multicenter evaluation [31] |

| Sterile Body Fluids | Combined approach | Maximizes diagnostic efficacy | Pleural, pancreatic, ascites, CSF (n=248) [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized wcDNA mNGS Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core experimental procedures for wcDNA mNGS:

Figure 1: Standardized workflow for wcDNA mNGS testing

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Sample Processing and DNA Extraction

For body fluid samples (pleural fluid, ascites, BALF, CSF), the standardized protocol involves:

- Centrifugation: 20,000 × g for 15 minutes to separate cellular components from supernatant [2]

- Cell Lysis: Addition of nickel beads (3-mm) to retained precipitate, shaken at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes [2]

- DNA Extraction: Using commercial kits (Qiagen DNA Mini Kit) following manufacturer's protocol [2]

- DNA Quantification: Fluorometric methods (Qubit 4.0) for accurate quantification prior to library preparation [1]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina [2]

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina NovaSeq with 2×150 paired-end configuration [2]

- Sequencing Depth: Approximately 8 GB of data per sample (≈26.7 million reads) [2]

- Controls: Negative controls (sterile deionized water) and positive controls with each batch [1]

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Quality Control: Removal of adapter sequences, low-quality, and short reads (<35bp) [1]

- Host DNA Depletion: Mapping to human reference genome (hg38) using bowtie2 [1]

- Pathogen Identification: Alignment against comprehensive microbial genome databases [1]

- Validation: Comparison with culture results, 16S/ITS amplicon sequencing, or qPCR [31]

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS depends on multiple experimental and clinical factors:

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting between wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential research reagents for wcDNA mNGS workflows

| Reagent/Kits | Manufacturer | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qiagen DNA Mini Kit | Qiagen | wcDNA extraction from cell pellets | Body fluids, tissue specimens [2] |

| VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit | Vazyme Biotech | NGS library preparation | Low-input DNA samples [2] |

| QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit | QIAGEN | Library preparation for limited DNA | Single-cell or low biomass samples [1] |

| gentleMACS Dissociator | Miltenyi Biotec | Tissue dissociation for single-cell suspension | Tissue specimens [32] |

| PythoN Tissue Dissociation System | Singleron | Integrated tissue dissociation | Multiple tissue types (200+ validated) [32] |

| Singulator Platform | S2 Genomics | Automated cell/nuclei isolation | Fresh, frozen, and FFPE tissues [32] |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

Integrated Interpretation of Findings

The comparative data presented reveals that neither wcDNA nor cfDNA mNGS universally outperforms the other across all clinical scenarios. Instead, these methods exhibit complementary strengths that can be strategically leveraged based on clinical context, suspected pathogen category, and sample type availability. wcDNA mNGS demonstrates particular value in scenarios involving high host-background samples and bacterial infections, where intact microbial cells are likely to be present in sufficient quantities for detection [2] [31]. The higher specificity of wcDNA mNGS for bacterial pathogens in body fluids makes it particularly valuable for abdominal infections and other non-bloodstream infections where intracellular pathogens may be present.

Conversely, cfDNA mNGS excels in detecting viral pathogens and intracellular microorganisms that may be released into the extracellular space through cell lysis or active secretion [31] [1]. The superior performance of cfDNA mNGS in blood samples aligns with the natural distribution of cell-free microbial DNA in circulation, making it the method of choice for bloodstream infections and systemic viral infections.

Limitations and Technical Challenges

Despite its advantages, wcDNA mNGS presents several technical challenges that require consideration:

- Lower sensitivity for viruses and intracellular pathogens compared to cfDNA approaches [1]

- Variable performance across different sample types and pathogen categories [2] [31]

- Compromised specificity (56.34%) in some clinical evaluations, necessitating careful result interpretation [2]

- Dependence on sample processing protocols that preserve cellular integrity [32]

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

The emerging consensus from recent studies supports a combined approach utilizing both wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS when feasible, as this strategy achieves the highest diagnostic efficacy (ROC AUC: 0.8583) compared to either method alone [31] [28]. For resource-limited settings or when sample volume is constrained, the decision framework provided in this guide offers evidence-based guidance for method selection.

Future research directions should focus on standardizing extraction protocols, establishing validated cutoff values for pathogen identification, and developing integrated bioinformatic pipelines that can simultaneously analyze both wcDNA and cfDNA sequencing data. Additionally, more comprehensive cost-benefit analyses are needed to guide the implementation of these technologies in routine clinical practice.

For clinical researchers and diagnostic developers, these findings underscore the importance of aligning methodological approaches with clinical questions and sample characteristics rather than seeking a universal solution for pathogen detection across all scenarios.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection by enabling unbiased identification of microorganisms in clinical samples. Two primary approaches have emerged for nucleic acid extraction: whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) sequencing, which targets genomic DNA from intact microorganisms, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) sequencing, which targets microbial DNA fragments circulating in body fluids. The optimal specimen type and processing method vary significantly depending on the clinical context, pathogen characteristics, and infection site. This guide objectively compares the performance of cfDNA mNGS across three key sample types—plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) supernatant—within the broader framework of comparing wcDNA versus cfDNA methodologies for pathogen identification, providing researchers with evidence-based selection criteria.

Performance Comparison Across Sample Types

Analytical and Diagnostic Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance characteristics of cfDNA mNGS across different sample types

| Sample Type | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Bloodstream infections, disseminated infections, immunocompromised hosts | Minimally invasive, ideal for detecting circulating pathogen DNA, reflects disseminated infection | Lower pathogen DNA concentration, susceptible to background human DNA interference | 76.44%-77.70% (BSI diagnosis) [33] | Higher for viral detection (AUC: 0.9814) [31] |

| CSF | Central nervous system infections, meningitis, encephalitis | Low host background, high clinical relevance for CNS pathogens | Invasive collection procedure, limited volume typically obtained | Associated with disease progression/metastasis in MB [34] | Specificity not explicitly quantified in available studies |

| BALF Supernatant | Pulmonary infections, pneumonia, fungal detection | Higher fungal/viral detection vs. wcDNA, better performance for intracellular pathogens | Potential contamination from colonizing microbes in respiratory tract | 91.5% detection rate [29] | Improved RPM values for Aspergillus detection [21] |

Quantitative Pathogen Detection Metrics

Table 2: Comparison of quantitative detection capabilities across sample types

| Sample Type | Optimal Pathogen Targets | Superiority Over wcDNA mNGS | Read Thresholds | Limits of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Viruses, disseminated bacterial/fungal infections | Comparable accuracy to mNGS at reduced cost (tNGS) [33] | RPM ≥6 for common bacteria; ≥0.5 for fungi/mycobacteria [33] | 9.3-149 GE/mL [31] |

| CSF | CNS pathogens, particularly in high-grade infections | Shorter fragment size (150-200bp) indicates true cfDNA [34] | Not explicitly stated in studies | Not quantified in pathogen detection context |

| BALF Supernatant | Fungi (31.8%), viruses (38.6%), intracellular microbes (26.7%) [29] | Higher RPM for Aspergillus (cut-off >4.5 predicts true PA) [21] | Standard mNGS thresholds apply | Not explicitly determined |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized cfDNA Extraction and Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for cfDNA mNGS that is commonly adapted across different sample types:

Diagram 1: Core cfDNA mNGS workflow. This generalized protocol is adapted specifically for plasma, CSF, and BALF supernatant samples with modifications at key steps.

Sample-Specific Processing Protocols

Plasma Processing for Bloodstream Infections

For plasma cfDNA analysis, blood samples are collected in anticoagulant tubes and processed following a standardized protocol [33] [35]. Samples are centrifuged at 1900 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes to separate cellular components. The resulting supernatant (plasma) is transferred to a fresh tube and subjected to a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove any remaining cellular debris. cfDNA is extracted from 0.5-1 mL of plasma using specialized kits (QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit or PathoXtract Plasma Nucleic Acid Kit) according to manufacturers' protocols [33] [34]. The extracted cfDNA undergoes library preparation using kits such as the KAPA DNA HyperPrep Kit or QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit, followed by sequencing on platforms like Illumina NextSeq 550 or MGISEQ-2000 [29] [33] [35].

CSF Processing for CNS Infections

CSF samples collected via lumbar puncture or during surgical procedures are processed with particular attention to potential low biomass [34]. Fresh CSF is centrifuged at 4°C (1400 × g for 5 minutes) within 2-3 hours of collection. The supernatant is carefully transferred to cryotubes and stored at -80°C until processing. cfDNA extraction employs the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, with critical verification of fragment size distribution (150-200 bp) using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer to confirm true cfDNA rather than cellular genomic DNA [34]. Library preparation typically requires amplification kits designed for low input DNA, such as the KAPA Library Amplification Kit, with targeted capture approaches sometimes employed to enhance sensitivity for CNS pathogens.

BALF Supernatant Processing for Pulmonary Infections

BALF samples are centrifuged at varying forces (12,075 × g for 5 minutes to 20,000 × g for 15 minutes) to separate supernatant from cellular components [36] [31] [21]. The supernatant is carefully collected for cfDNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or similar systems. For comprehensive pathogen detection, simultaneous RNA extraction may be performed for RNA viruses, followed by reverse transcription to cDNA [35]. Library preparation utilizes kits such as the QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit or VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit, with sequencing typically on Illumina platforms (NextSeq 550, NovaSeq) [29] [21].

Complementary Value of cfDNA and wcDNA mNGS

Integrated Testing Approach

The relationship between cfDNA and wcDNA mNGS testing is complementary rather than competitive, as illustrated in the following decision pathway:

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for sample type selection. This flowchart guides appropriate sample selection based on clinical presentation and demonstrates the complementary relationship between cfDNA and wcDNA testing approaches.

Performance Synergy

Research demonstrates that combining cfDNA and wcDNA mNGS achieves superior diagnostic efficacy compared to either method alone. A comprehensive evaluation of 248 specimens showed the area under the ROC curve increased to 0.8583 for combined testing, compared to 0.8041 for cfDNA alone and 0.7545 for cellular DNA alone [31] [28]. In pulmonary aspergillosis, combining BALF-cfDNA mNGS with conventional tests significantly improved sensitivity (89.47% vs. 47.37%) and ROC analysis (0.813 vs. 0.66) compared to conventional tests alone [21]. For pneumonia-derived sepsis, simultaneous plasma and BALF mNGS testing identified definite causative pathogens in 55.6% of cases, substantially higher than either sample type alone (20.8% for plasma, 18.8% for BALF) [35].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and kits for cfDNA mNGS research

| Reagent/Kits | Specific Examples | Application Function | Sample Type Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, PathoXtract Plasma Nucleic Acid Kit, VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit | Isolation of short-fragment cfDNA from body fluids while removing cellular genomic DNA | Plasma, CSF, BALF supernatant |

| Library Preparation Kits | QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit, KAPA DNA HyperPrep Kit, VAHTS Universal Pro DNA Library Prep Kit | Construction of sequencing libraries from low-input cfDNA samples | Universal across sample types |

| Nucleic Acid Quantification | Qubit Fluorometer with dsDNA HS Assay, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Accurate quantification and quality assessment of low-concentration cfDNA | Universal across sample types |

| Host DNA Depletion Reagents | Custom probes for human genome sequences | Reduction of host background to improve microbial signal detection | Plasma (high host background) |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Ultra-broad hybrid capture panels (e.g., 1872 pathogen panel) | Enhanced detection of low-abundance pathogens through probe-based enrichment | Plasma (tNGS applications) |

The selection of optimal sample types for cfDNA mNGS depends on the clinical scenario, target pathogens, and analytical priorities. Plasma cfDNA excels for bloodstream and disseminated infections, particularly in immunocompromised hosts, and shows special utility for viral detection. BALF supernatant cfDNA demonstrates superior performance for respiratory fungi, viruses, and intracellular pathogens compared to wcDNA approaches. CSF cfDNA offers unique value in neuro-infections and is strongly associated with disease progression in central nervous system pathologies. Rather than considering these approaches in isolation, researchers should recognize the complementary value of cfDNA and wcDNA mNGS, as their combined application consistently demonstrates enhanced diagnostic efficacy across multiple sample types and clinical scenarios.

Superiority of cfDNA for Detecting Viruses, Fungi, and Intracellular Pathogens

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has revolutionized pathogen detection by enabling unbiased, comprehensive analysis of microbial nucleic acids in clinical samples. Two primary approaches have emerged for sample processing: whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS, which sequences DNA from intact microbial cells, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS, which targets freely circulating microbial DNA fragments. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methods, with a specific focus on the demonstrated superiority of cfDNA mNGS for detecting viruses, fungi, and intracellular pathogens. Understanding the technical basis for these performance differences is critical for researchers and clinicians to select the optimal method for specific diagnostic and research applications.

Fundamental Technical Differences Between cfDNA and wcDNA mNGS

The divergent performance characteristics of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS stem from fundamental differences in their source materials and processing workflows.