Validating the Future: How the Materials Genome Initiative is Proving Predictive Models in Materials Science

This article explores the critical frameworks and methodologies for validating predictions generated under the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), a major effort to accelerate materials discovery and deployment.

Validating the Future: How the Materials Genome Initiative is Proving Predictive Models in Materials Science

Abstract

This article explores the critical frameworks and methodologies for validating predictions generated under the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), a major effort to accelerate materials discovery and deployment. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines the foundational role of integrated computation, experiment, and data. The scope spans from core validation concepts and cutting-edge applications like Self-Driving Labs (SDLs) to troubleshooting predictive model failures and comparative analyses of validation success stories across sectors such as biomedicine and energy. The article synthesizes how a robust validation paradigm is transforming materials innovation from an Edisonian pursuit into a predictive science.

The MGI Validation Paradigm: Integrating Computation and Experiment

The discovery and development of new materials have historically been a slow and arduous process, heavily reliant on intuition and extensive experimentation. The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) represents a paradigm shift, aiming to double the speed and reduce the cost of bringing advanced materials to market by transitioning from this "Edisonian" trial-and-error approach to a new era of predictive design [1] [2]. This guide examines the core methodologies of this new paradigm, comparing its performance against traditional techniques and detailing the experimental protocols that make it possible.

Table of Contents

- The Paradigm Shift in Materials Development

- Quantitative Performance Comparison

- Experimental Protocols for Predictive Design

- Visualizing the MGI Workflow

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

The Paradigm Shift in Materials Development

The traditional process for discovering new materials is often described as craft-like, where skilled artisans test numerous candidates through expensive and time-consuming trial-and-error experiments [2]. For example, a slight alteration in a metal alloy's composition can change its strength by over 50%, but investigating all possible variations is prohibitively expensive. This results in slow progress and missed opportunities for innovation in sectors from healthcare to energy [2].

The MGI vision counters this by leveraging computational materials design. Using physics-based models and simulation, researchers can now predict material properties and performance before ever entering a lab. This approach is a major enabler for modern manufacturing, transforming materials engineering from an art into a data-driven science [2].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The superiority of the MGI-informed predictive design approach is demonstrated by tangible improvements in development efficiency and cost-effectiveness across multiple industries. The table below summarizes key performance indicators, contrasting traditional methods with the MGI approach.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. MGI-Informed Materials Development

| Metric | Traditional Trial-and-Error Approach | MGI Predictive Design Approach | Data Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 10-20 years [2] | 9 years, aiming for further 50% reduction [2] | Jet engine alloy development (GE) |

| Design Time Savings | Baseline | ~17 years saved in a single year [2] | Virtual computing in product design (Procter & Gamble) |

| Primary Method | Empirical experimentation [2] | Computational models & simulation [2] | Core MGI methodology |

| Data Handling | Spotty, uncoordinated, incompatible formats [2] | Structured, accessible repositories with community standards [3] | MGI Data Infrastructure Goal |

| Exploration Capability | Limited investigation of major composition alterations [2] | Ability to probe atomic-scale interactions and properties [2] | Quantum-scale modeling |

Experimental Protocols for Predictive Design

The successful implementation of the MGI framework relies on well-defined experimental and computational protocols. Here, we detail the core methodologies that generate the data essential for validating predictions.

Protocol: Multi-Scale Modeling for Alloy Development

This protocol integrates computational models across different physical scales to design new alloy compositions with targeted properties.

Atomic-Scale Modeling (Quantum Mechanics):

- Function: Calculate fundamental physical properties based on atomic and molecular interactions. Provides data that is often too expensive or impossible to measure experimentally, such as interface energies between solid phases and barriers to atomic diffusion [2].

- Input: Proposed atomic composition and structure.

- Output: Energetics and properties at the nanoscale.

Micro-Scale Modeling (Crystal Defects):

- Function: Simulate the behavior of crystal grain defects and microstructures. This scale bridges the gap between atomic arrangements and macroscopic material properties [2].

- Input: Results from atomic-scale modeling.

- Output: Predictions of microstructural evolution and its impact on properties like strength.

Macro-Scale Modeling (Engineering Performance):

- Function: Predict the performance of a material at the component level (e.g., a turbine blade or steel I-beam) [2].

- Input: Results from micro-scale modeling.

- Output: Engineering parameters such as tensile strength, fatigue resistance, and corrosion behavior.

Experimental Validation:

- Function: Test a subset of the most promising candidates identified by the computational models to confirm their predicted properties.

- Methods: Laboratory synthesis of alloys followed by mechanical testing and microstructural analysis to validate model accuracy [2].

Protocol: Building and Utilizing a Materials Data Infrastructure

A robust data infrastructure is the backbone of MGI, ensuring that data from both experiments and calculations is accessible and usable.

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Function: Generate and collect high-quality materials data from diverse sources, including published literature, high-throughput experiments, and computational simulations [3].

- Standards: Apply community-developed standards for data format, metadata, and types to ensure consistency and reliability [3].

Data Repository Management:

Data Utilization and Analysis:

- Function: Use the aggregated data to identify gaps in available knowledge, limit redundancy in research efforts, and provide evidence for the validation of MGI predictions [3].

- Workflow Integration: Incorporate data capture methods into existing research workflows to continuously enrich the infrastructure [3].

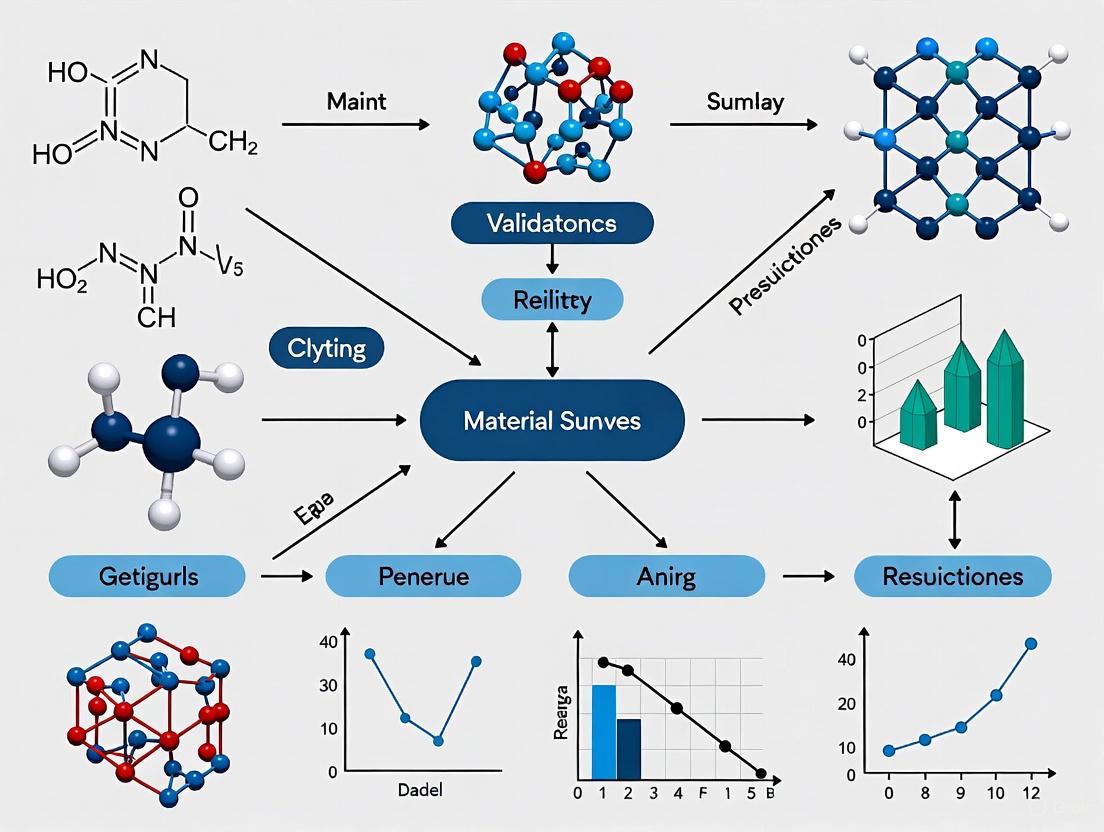

Visualizing the MGI Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical workflow of the Materials Genome Initiative, from initial computational design to final deployment and data feedback.

MGI Integrated Innovation Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

The effective execution of MGI-related research requires a suite of tools and resources. The table below details key components of the materials innovation infrastructure.

Table 2: Essential Tools for Accelerated Materials Research and Development

| Tool / Solution | Function | Role in MGI Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Physics-Based Material Models | Computational models that simulate material behavior based on fundamental physical principles. | Enable "computational materials by design," predicting properties and performance before synthesis [2]. |

| Materials Data Repositories | Online platforms for housing, searching, and curating materials data from experiments and calculations. | Provide the medium for knowledge discovery and evidence for validating predictions [3]. |

| Community Data Standards | Protocols defining data formats, metadata, and types for interoperability. | Ensure seamless data transfer and integration across different research groups and tools [3]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Automated systems that rapidly synthesize and characterize large numbers of material samples. | Generate large, consistent datasets for model validation and training, accelerating the experimental loop. |

| Multi-Scale Simulation Software | Software that links models across atomic, micro, and macro scales. | Allows investigation of how atomic-scale interactions impact macroscopic engineering properties [2]. |

| Automated Data Capture Tools | Methods and software for integrating data generation directly into research workflows. | Ensures valuable data is systematically captured and added to the shared infrastructure [3]. |

| Path-Finder Project Models | Exemplar projects that demonstrate integrated MGI infrastructure. | Serve as practical blueprints for overcoming challenges in accelerated materials development [2]. |

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) has established a bold vision for accelerating materials discovery through the integration of computation, data, and experiment [4]. While substantial progress has been made through computational methods and curated data infrastructures, a critical barrier remains: the need for empirical validation to bridge digital predictions with real-world performance [4]. This gap is particularly evident in fields ranging from materials science to biomedical research, where digital workflows offer tremendous promise but require rigorous physical validation to establish scientific credibility. Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent a transformative approach to closing this loop, integrating robotics, artificial intelligence, and autonomous experimentation to create a continuous feedback cycle between digital prediction and physical validation [4].

The concept of "closing the loop" refers to creating a continuous, iterative process where computational models generate hypotheses, physical experiments test these predictions, and experimental results refine the computational models [4]. This creates a virtuous cycle of improvement that enhances both predictive accuracy and experimental efficiency. As research increasingly relies on digital workflows—from computer-aided design (CAD) in prosthodontics to high-throughput virtual screening in materials informatics—the role of physical validation becomes not merely supplementary but essential for establishing scientific credibility and functional reliability [5] [4].

Comparative Analysis: Digital Workflows Versus Conventional Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Domains

Digital workflows demonstrate significant advantages across multiple domains, though their effectiveness must be validated through physical testing. The table below summarizes key comparative findings from systematic reviews and clinical studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of digital versus conventional workflows across research and clinical domains

| Performance Metric | Digital Workflows | Conventional Workflows | Domain/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | 100× to 1000× acceleration [4] | Baseline manual pace | Materials discovery via SDLs |

| Process Efficiency | Reduced working time, eliminated tray selection [5] | Time-intensive manual procedures | Dental restorations [5] |

| Accuracy/Precision | Lower misfit rate (15%) [6] | Higher misfit rate (25%) [6] | Implant-supported restorations |

| Patient/User Satisfaction | Significantly higher VAS scores (p < 0.001) [6] | Lower comfort and acceptance scores [5] | Clinical dental procedures |

| Material Consumption | Minimal material consumption [5] | Significant material consumption [5] | Dental prosthesis fabrication |

| Adaptive Capability | Real-time experimental refinement [4] | Fixed experimental sequences | Materials optimization |

Validation Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The transition from digital prediction to validated outcome requires rigorous methodological frameworks. Across domains, several established protocols provide the structural foundation for physical validation.

Table 2: Experimental protocols for validating digital workflow predictions

| Validation Method | Application Context | Key Procedures | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sheffield Test & Radiography | Implant-supported restorations [6] | Clinical assessment of prosthesis fit at implant-abutment interface using mechanical testing and radiographic imaging | Misfit rates, marginal bone resorption, screw loosening [6] |

| Closed-Loop DMTA Cycles | Molecular and materials discovery [4] | Iterative design-make-test-analyze cycles using robotic synthesis and online analytics | Convergence on high-performance molecules, structure-property relationships [4] |

| Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization | Autonomous experimentation [4] | Balance trade-offs between conflicting goals (cost, toxicity, performance) with uncertainty-aware models | Optimization efficiency, navigation of complex design spaces [4] |

| High-Throughput Screening | Functional materials development [4] | Parallel synthesis and characterization of multiple material compositions | Identification of optimal compositional ranges, validation of computational predictions [4] |

Implementation Framework: Architectural Components for Physical Validation

The Self-Driving Laboratory Infrastructure

Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent the most advanced implementation of integrated physical validation systems. Their architecture provides a template for effective digital-physical integration across multiple domains.

Diagram 1: The five-layer architecture of Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) enabling continuous physical validation. Each layer contributes to closing the loop between digital prediction and experimental validation.

The Validation Feedback Cycle

The core mechanism for closing the loop between digital prediction and physical reality involves a continuous feedback process that refines both models and experiments.

Diagram 2: The validation feedback cycle demonstrating how physical experimental results continuously refine digital models and experimental designs.

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

The implementation of robust validation workflows requires specific research tools and materials. The following table details essential solutions for establishing physical validation systems.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and instrumentation for physical validation workflows

| Research Solution | Function in Validation Workflow | Specific Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoral Scanners (TRIOS 3, Medit i700) | Digital impression capture for comparison with physical outcomes [6] | Dental restoration fit assessment | Scan accuracy, stitching algorithms, reflective surface handling [6] |

| Autonomous Experimentation Platforms | High-throughput robotic synthesis and characterization [4] | Materials discovery, optimization | Integration with AI planners, modularity, safety protocols [4] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Efficient navigation of complex experimental spaces [4] | Multi-objective materials optimization | Acquisition functions, uncertainty quantification, constraint handling [4] |

| Polyvinyl Siloxane (PVS) & Polyether | Conventional impression materials for control comparisons [6] | Dental prosthesis fabrication | Dimensional stability, polymerization shrinkage, hydrophilic properties [6] |

| Generative Molecular Design Algorithms | Inverse design of molecules with target properties [4] | Dye discovery, pharmaceutical development | Chemical space exploration, synthesizability prediction, property prediction [4] |

Case Studies: Successful Integration of Physical Validation

Dental Restorations: Digital Versus Conventional Workflows

In prosthodontics, the comparison between digital and conventional workflows provides a compelling case study in physical validation. A systematic review of fixed partial dentures found that digital workflows reduced working time, eliminated tray selection, minimized material consumption, and enhanced patient comfort and acceptance [5]. Crucially, these digital workflows resulted in greater patient satisfaction and higher success rates than conventional approaches [5].

A clinical study on implant-supported restorations demonstrated a lower misfit rate in the digital group (15%) compared to the conventional group (25%), with no final-stage misfits in digital cases [6]. Digital workflows demonstrated shorter impression times, fewer procedural steps, and reduced the need for prosthetic adjustments [6]. Patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the digital group across all Visual Analog Scale parameters (p < 0.001), particularly in comfort and esthetic satisfaction [6]. These physical validation metrics confirm the superiority of digital approaches while highlighting the importance of clinical testing for verifying digital predictions.

Autonomous Materials Discovery

The development of an autonomous multiproperty-driven molecular discovery (AMMD) platform exemplifies cutting-edge physical validation in materials science. This SDL united generative design, retrosynthetic planning, robotic synthesis, and online analytics in a closed-loop format to accelerate the design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycle [4]. The platform autonomously discovered and synthesized 294 previously unknown dye-like molecules across three DMTA cycles, showcasing how an SDL can explore vast chemical spaces and converge on high-performance molecules through autonomous robotic experimentation [4].

This case study demonstrates the power of integrated validation systems, where digital predictions are continuously tested and refined through physical experimentation. The AMMD platform exemplifies how closing the loop between computation and experiment can dramatically accelerate discovery while ensuring practical relevance through continuous physical validation.

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

As physical validation technologies evolve, several challenges must be addressed to maximize their impact. Interoperability between different SDL systems requires open application programming interfaces (APIs), shared data ontologies, and robust orchestrators [4]. Cybersecurity is critical given the physical risks associated with autonomous experimentation [4]. Sustainability considerations, such as reagent use, waste generation, and energy consumption, must be integrated into SDL design and operation [4].

Two dominant deployment models are emerging for scaling validation infrastructure: Centralized SDL Foundries that concentrate advanced capabilities in national labs or consortia, and Distributed Modular Networks that enable widespread access through low-cost, modular platforms in individual laboratories [4]. A hybrid model offers the best of both worlds, where preliminary research is conducted locally using distributed SDLs, while more complex tasks are escalated to centralized SDL facilities [4].

The continued development of autonomous validation systems promises to transform materials and drug development by creating a continuous, evidence-driven dialogue between digital prediction and physical reality. As these systems become more sophisticated and accessible, they will play an increasingly essential role in closing the loop between computational aspiration and practical application.

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII) represents a foundational framework established by the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) to unify the essential components required for accelerating materials discovery and development. Conceived to address the traditionally lengthy timelines of materials research and development (R&D)—often spanning decades—the MII integrates three core pillars: data, computation, and experiment into a cohesive, iterative workflow [7]. This paradigm shift from sequential, siloed research to an integrated approach enables the "closed-loop" innovation essential for discovering, manufacturing, and deploying advanced materials twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost [1] [8].

The MII's significance extends across numerous sectors, including healthcare, communications, energy, and defense, where advanced materials are critical for technological progress [7]. By framing research within the context of the Materials Development Continuum (MDC), the MII promotes continuous information flow and iteration across all stages, from discovery and development to manufacturing and deployment [7]. This article examines the three pillars of the MII, comparing their components, presenting experimental data validating their efficacy, and detailing the protocols that enable their integration, providing researchers with a practical guide for leveraging this transformative infrastructure.

The Three Core Pillars: A Comparative Analysis

The MII's power derives from the synergistic integration of its three pillars. The table below provides a structured comparison of their key components, primary functions, and implementation requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Three Core Pillars of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure

| Pillar | Key Components & Tools | Primary Function | Infrastructure & Implementation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Infrastructure | Data repositories, FAIR data principles, data exchange standards, data workflows [9]. | Harness the power of materials data for discovery and machine learning; enable data sharing and reuse [1]. | Data policies, cloud/data storage, semantic ontologies, data curation expertise, data science skills [9] [10]. |

| Computation | Theory, modeling, simulation, AI/ML, high-throughput virtual screening, surrogate models, digital twins [9] [7]. | Guide experimental design; predict material properties and behavior; accelerate simulation [11] [7]. | High-performance computing (HPC), community/commercial codes, AI/ML algorithms, domain knowledge for physics-informed models [9] [12]. |

| Experiment | Synthesis/processing tools, characterization, integrated research platforms, high-throughput & autonomous experimentation [9]. | Generate validation data; synthesize and characterize new materials; close the loop with computation [11]. | State-of-the-art instrumentation, robotics, modular/autonomous tools, physical laboratory space [9] [8]. |

The Data Pillar: Foundation for AI-Driven Discovery

The data pillar serves as the foundational element of the MII, enabling the data-centric revolution in materials science. Its primary objective is to create a National Materials Data Network that unifies data generators and users across the entire materials ecosystem [9]. Key initiatives focus on developing tools, standards, and policies to encourage the adoption of FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), which are critical for ensuring the usability and longevity of materials data [9] [10].

A major challenge in this domain is the nature of materials science data, which is often sparse, high-dimensional, biased, and noisy [12]. Progress hinges on resolving issues related to metadata gaps, developing robust semantic ontologies, and building data infrastructures capable of handling both large-scale and small datasets [10]. Successfully addressing these challenges unlocks the potential for materials informatics, where data-centric approaches and machine learning are used to design new materials and optimize processes, as demonstrated in applications ranging from CO₂ capture catalysts to digital scent reproduction [12] [13].

The Computation Pillar: Predictive Power and Digital Twins

The computation pillar provides the predictive power for the MII, moving materials science from a descriptive to a predictive discipline. This pillar encompasses a wide spectrum of tools, from foundational physics-based models and simulations to emerging AI and machine learning technologies. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are generating predictive and surrogate models that can potentially replace or augment more computationally intensive physics-based simulations, dramatically accelerating the design cycle [7].

A key concept enabled by advanced computation is the materials digital twin—a virtual replica of a physical material system that is continuously updated with data from experiments and simulations [7]. These twins allow researchers to test hypotheses and predict outcomes in silico before conducting physical experiments. Furthermore, computational methods are essential for solving complex "inverse problems" in materials design, where the goal is to identify the optimal material composition and processing parameters required to achieve a set of desired properties [12]. The integration of high-performance computing (HPC) and emerging quantum computing platforms is pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible in materials modeling [13].

The Experiment Pillar: Validation and Autonomous Discovery

The experiment pillar grounds the MII in physical reality, providing the critical function of validating computational predictions and generating high-quality training data for AI/ML models. The paradigm is shifting from purely human-driven, low-throughput experimentation to high-throughput and autonomous methodologies. A transformative advancement in this area is the development of Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs), which integrate AI, robotics, and automated characterization in a closed-loop system to design, execute, and analyze thousands of experiments in rapid succession without human intervention [7].

These autonomous experimentation platforms are being developed for various synthesis techniques, including physical vapor deposition and chemical vapor deposition, which are vital for producing advanced electrical and electronic materials [7]. The evolution of instrumentation is also remarkable, with progress toward fully autonomous electron microscopy and scanning probe microscopy, transitioning from human-operated tools to AI/ML-enabled systems for physics discovery and materials optimization [7]. The expansion of synthesis and processing tools to more materials classes and the development of multimodal characterization tools are key objectives for bolstering this pillar [9].

Validating the Integrated Approach: Experimental Evidence and Protocols

The true validation of the MII lies in its ability to accelerate the development of real-world materials. The following case studies and data demonstrate the tangible impact of integrating data, computation, and experiment.

Case Study 1: Accelerated Catalyst Discovery for CO₂ Capture

A project led by NTT DATA in collaboration with Italian universities provides a compelling validation of the MGI approach for discovering molecules that efficiently capture and catalyze the transformation of CO₂.

- Objective: To accelerate the discovery and design of novel molecular catalysts for CO₂ capture and conversion [13].

- Integrated Workflow:

- Data & Computation: Leveraged High-Performance Computing (HPC) and Machine Learning (ML) models to screen vast chemical spaces. Generative AI was used to propose new molecular structures with optimized properties, expanding the search beyond traditional design paradigms [13].

- Experiment: The most promising candidate molecules identified by the computational workflow were passed to chemistry experts for experimental validation [13].

- Outcome: The integrated protocol successfully identified promising molecules for CO₂ catalysis, significantly accelerating the discovery timeline compared to traditional, sequential methods. The workflow is designed to be transferable to other chemical systems [13].

Case Study 2: High-Throughput Development of Functional Materials

The U.S. National Science Foundation's Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP) program is a prime example of the MII implemented at a national scale. MIPs are mid-scale infrastructures that operate on the principle of "closed-loop" research, iterating continuously between synthesis, characterization, and theory/modeling/simulation [8].

- Experimental Protocol of a MIP:

- Sample Synthesis/Processing: Using high-throughput or autonomous methods to create a library of material samples with varied compositions or processing conditions [8].

- Rapid Characterization: Employing advanced, often automated, characterization tools to collect data on the structure and properties of the synthesized samples.

- Data Analysis & Modeling: Feeding the experimental data into AI/ML models and simulations to refine the understanding of processing-structure-property relationships. The model then recommends the next set of synthesis parameters to test.

- Iteration: The loop continues, with each cycle refining the material design until the target performance is achieved [8].

- Validation Data: The MIP program has demonstrated success in specific domains. For instance, the Air Force Research Laboratory has manufactured and tested "thousands of transistors within unique devices having varied micrometer-scale physical dimensions" using a materials genome approach, a task that would be prohibitively time-consuming with traditional methods [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of MGI Approaches in Applied Research

| Application Area | Traditional Development Timeline | MGI-Accelerated Timeline | Key Enabling MII Pillars |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Materials Commercialization [14] | 10 - 20 years | 2 - 5 years | Data (Informatics), Computation (AI/ML), Experiment (High-throughput) |

| Deodorant Formulation [13] | Not specified | ≈ 95% reduction in production time | Computation (Proprietary Optimization Algorithms), Data (Scent Quantification) |

| Novel Alloys for Defense [11] | Several years | Developed "in a fraction of the traditional time" | Computation (ICME, CALPHAD), Experiment (Integrated Validation) |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, closed-loop workflow that is central to the MGI approach, as implemented in platforms like MIPs and Self-Driving Labs.

Diagram 1: The MGI Closed-Loop Innovation Workflow

Engaging with the Materials Innovation Infrastructure requires familiarity with a suite of tools and resources. The table below details key "research reagent solutions"—both digital and physical—that are essential for conducting research within the MGI paradigm.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for MII-Based Materials Research

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function & Application | Example Platforms/Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Experimentation (AE) Platforms | Experiment | Robotics and AI to run experiments without human intervention, enabling high-throughput discovery. | Self-Driding Laboratories (SDLs) for material synthesis [7]. |

| AI/ML Materials Platforms | Computation | SaaS platforms providing specialized AI tools for materials scientists with limited data science expertise. | Citrine Informatics, Kebotix, Materials Design [14]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Computation | Provides the computational power for high-fidelity simulations and training complex AI/ML models. | NSF Advanced Cyberinfrastructure; Cloud HPC services [13]. |

| FAIR Data Repositories | Data | Stores and shares curated materials data, ensuring findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. | Various public and institutional repositories promoted by MGI [9] [10]. |

| Integrated Research Platforms | All Pillars | Scientific ecosystems offering shared tools, expertise, and collaborative in-house research. | NSF Materials Innovation Platforms (MIPs) [8]. |

| Collaborative Research Programs | All Pillars | Funding vehicles that mandate interdisciplinary, closed-loop collaboration for materials design. | NSF DMREF (Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future) [15]. |

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure, built upon the integrated pillars of data, computation, and experiment, has fundamentally reshaped the materials research landscape. Validation through real-world case studies confirms its power to dramatically compress development timelines from decades to years, offering a decisive competitive advantage in fields from energy storage to pharmaceuticals [13] [14]. The core of this success lies in the iterative, closed-loop workflow where each pillar informs and strengthens the others, creating a cycle of continuous learning and optimization.

Looking ahead, the maturation of the MII will be driven by the expansion of data infrastructures adhering to FAIR principles, the advancement of physics-informed AI models and digital twins, and the widespread adoption of autonomous experimentation and self-driving labs [7] [10]. For researchers, embracing this paradigm requires a cultural shift toward collaboration and data sharing, as well as engagement with the tools and platforms that constitute the modern materials research toolkit. Sustained investment and interdisciplinary collaboration are essential to fully realize the MII's potential, ensuring that the accelerated discovery and deployment of advanced materials continue to address pressing global challenges and drive technological innovation.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), launched in 2011, aims to accelerate the discovery and deployment of advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost of traditional methods [7] [1]. A core paradigm of the MGI is the integration of computation, data, and experiment to create a continuous innovation cycle [7]. Central to this mission is validating computational predictions with rigorous experimental data, thereby building trust in models and reducing reliance on costly, time-consuming empirical testing.

This case study examines the critical process of validating computational models for predicting the properties of polymer nanocomposites. These materials, which incorporate nanoscale fillers like graphene or carbon nanotubes into a polymer matrix, are central to advancements in sectors from aerospace to energy storage. We objectively compare model predictions against experimental results for key mechanical and functional properties, providing a framework for assessing the reliability of computational tools within the MGI infrastructure.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Validation

To ensure consistent and reproducible validation, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols for synthesizing nanocomposites and characterizing their properties.

Nanocomposite Fabrication

The solution casting method is a common technique for preparing polymer nanocomposite films, as used in the development of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) films loaded with lead tetroxide (Pb₃O₄) nanoparticles for radiation shielding [16]. The detailed protocol is as follows:

- Dissolution: A base polymer (e.g., 2 grams of PVA) is dissolved in a solvent (e.g., 50 ml of distilled water) at an elevated temperature (70°C) under continuous stirring for ~3 hours to achieve a homogeneous solution.

- Dispersion: Pre-determined weight percentages of nanofillers (e.g., 0.04 to 0.2 grams of Pb₃O₄) are added to the polymer solution. The mixture is stirred vigorously for ~1 hour to ensure uniform dispersion of the nanoparticles within the polymer matrix.

- Casting and Drying: The final mixture is cast onto a clean, level surface (e.g., a Petri dish) and allowed to dry slowly at a controlled temperature (50°C) for approximately 24 hours, forming a solid film [16].

Mechanical and Functional Characterization

Validating predictions for mechanical and functional properties requires standardized tests:

- Tensile Testing: This test measures fundamental mechanical properties like maximum stress (strength) and elastic modulus (stiffness). Specimens are loaded uniaxially until failure, and the resulting stress-strain data are analyzed [17].

- Dielectric Energy Storage Characterization: For capacitors, key properties include discharged energy density (Ue) and charge-discharge efficiency (η). These are derived from D-E loops (Electric Displacement-Electric Field loops) measured under high electric fields at various temperatures [18].

- Radiation Shielding Assessment: The shielding effectiveness of composites is evaluated by measuring the attenuation of gamma-ray photons from radioactive sources. A calibrated sodium iodide (NaI(Tl)) detector connected to a multichannel analyzer records the spectrum of photons transmitted through the sample. The linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) is a key metric derived from this data [16].

- Electromagnetic (EM) Reflection Loss: For EM absorption materials, the reflection loss (RL) spectrum is measured using a two-port vector network analyzer (VNA). The scattering parameters obtained are used to calculate the EM properties and overall performance [19].

Comparative Analysis: Prediction vs. Experiment

The following sections present quantitative comparisons between computational predictions and experimental results for different nanocomposite systems and properties.

Validating Micromechanical Models for Stiffness

The Halpin-Tsai model is a widely used analytical model for predicting the elastic modulus of fiber-reinforced composites. However, its accuracy diminishes for nanocomposites, especially at higher filler loadings, due to factors like nanoparticle agglomeration and imperfect orientation.

Table 1: Validation of Elastic Modulus Predictions for Graphene-Epoxy Nanocomposites

| Nanoparticle Type | Weight Percentage | Experimental Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Halpin-Tsai Prediction (GPa) | Modified Semi-Empirical Model Prediction (GPa) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene (Gr) | 0.6% | ~4.79 (19.7% increase) [17] | Significant over-prediction [17] | Greatly improved accuracy [17] | The traditional model fails at high loadings. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | 0.15% | Highest maximum stress (15.7% increase) [17] | Not Specified | Not Specified | GO provides superior strength enhancement. |

A study on graphene (Gr), graphene oxide (GO), and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) epoxy nanocomposites demonstrated this limitation. While the Halpin-Tsai model provided reasonable estimates at low filler contents, it showed significant deviation from experimental values at higher weight percentages (e.g., 0.6 wt% Gr), where it over-predicted the stiffness [17]. To address this, researchers presented a semi-empirical modified model that incorporated the impact of agglomeration and the Krenchel orientation factor. This enhanced model demonstrated significantly improved predictive accuracy when validated against experimental data, both from the study and external literature [17].

Validating Machine Learning Predictions for Strength

Machine learning (ML) models offer a powerful alternative for capturing the complex, non-linear relationships in nanocomposites. A 2025 study employed Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) coupled with Monte Carlo simulation to predict the tensile strength of carbon nanotube (CNT)-polymer composites [20].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Machine Learning Models Predicting Nanocomposite Tensile Strength

| Machine Learning Model | Mean Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | 0.96 | 12.14 MPa | 7.56 MPa | Provides uncertainty quantification [20] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Lower | Higher | Higher | Deterministic point estimates [20] |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Lower | Higher | Higher | "Black-box" model, hard to interpret [20] |

| Regression Tree (RT) | Lower | Higher | Higher | Prone to overfitting [20] |

The GPR model was trained on a comprehensive dataset of 25 polymer matrices, 22 surface functionalization methods, and 24 processing routes. Over 2000 randomized Monte Carlo iterations, it achieved a mean R² of 0.96, substantially outperforming conventional ML models like SVM, ANN, and RT [20]. The sensitivity analysis further revealed that CNT weight fraction, matrix tensile strength, and surface modification methods were the dominant features influencing predictive accuracy [20]. This highlights the power of data-driven models to not only predict but also identify key governing parameters.

Validating Performance for Functional Properties

Dielectric Energy Storage

Research on high-temperature dielectric capacitors showcases a successful validation loop for a complex material design. Researchers designed bilayer nanocomposites using high-entropy ferroelectric nanoparticles (NBBSCT-NN) coated with Al₂O₃ and incorporated into a polyetherimide (PEI) matrix [18]. The predicted combination of high dielectric constant from the filler and high breakdown strength from the polymer matrix was experimentally confirmed. The optimized composite achieved a record-high discharged energy density of 12.35 J cm⁻³ at 150°C, with a high efficiency of 90.25%—data that validated the initial computational design hypotheses [18].

Radiation Shielding

Studies on PVA/Pb₃O₄ nanocomposites for gamma-ray shielding show a strong correlation between computational and experimental methods. The shielding performance was evaluated both experimentally using a NaI(Tl) detector and theoretically using Phy-X/PSD software [16]. The results were consistent, confirming that higher concentrations of Pb₃O₄ nanoparticles improved the gamma-ray shielding effectiveness of the flexible PVA films [16]. This agreement between simulation and experiment provides confidence for using such tools in the design of novel shielding materials.

Electromagnetic Reflection Loss

An integrated approach was used to design multiphase composites with ceramic (BaTiO₃, CoFe₂O₄) and carbon-based (MWCNTs) inclusions for electromagnetic absorption [19]. An in-house optimization tool was used to extract the EM properties of individual nanoparticles, which were then validated by comparing the simulated reflection loss with experimental measurements from a two-port VNA [19]. The validated model was then used for parametric studies, revealing that Composites with high BaTiO₃ or MWCNT contents caused impedance mismatch, while CoFe₂O₄-dominant composites achieved broadband reflection loss (< -10 dB) over a 4.4 GHz bandwidth [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Nanocomposite Validation Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Nanoscale reinforcement; improves mechanical strength and stiffness [17]. | Epoxy nanocomposites for enhanced tensile strength [17]. |

| High-Entropy Ferroelectric Ceramics | Fillers for dielectric composites; enhance energy density and thermal stability [18]. | Bilayer polymer nanocomposites for high-temperature capacitors [18]. |

| Lead Tetroxide (Pb₃O₄) Nanoparticles | High-density filler for radiation shielding; attenuates gamma rays [16]. | Flexible PVA films for radiation protection applications [16]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Conductive filler; tailors electromagnetic absorption properties [19]. | Multiphase composites for broadband reflection loss [19]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Water-soluble polymer matrix; enables flexible composite films [16]. | Matrix for Pb₃O₄ nanoparticles in shielding films [16]. |

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | High-glass-transition-temperature polymer matrix for high-temperature applications [18]. | Matrix for dielectric nanocomposites in capacitors [18]. |

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for validating nanocomposite property predictions, a cornerstone of the MGI approach.

Figure 1: The MGI Validation Feedback Loop.

This case study demonstrates that while traditional analytical models like Halpin-Tsai have limitations in predicting nanocomposite behavior, particularly at higher filler loadings, advanced approaches show great promise. Semi-empirical models that account for real-world imperfections and, more importantly, data-driven machine learning models like Gaussian Process Regression can achieve high predictive accuracy with quantified uncertainty.

The consistent validation of computational predictions across diverse properties—from mechanical strength to dielectric and shielding performance—underscores a key achievement of the MGI paradigm. The integrated workflow of design-predict-synthesize-test-validate creates a virtuous cycle that accelerates materials development. As autonomous experimentation and self-driving labs mature, this feedback loop will become faster and more efficient, further realizing the MGI's goal of slashing the time and cost required to bring new advanced materials to market [7] [4].

Next-Generation Validation Tools: From Digital Twins to Self-Driving Labs

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), launched in 2011, aims to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost of traditional methods [4]. While computational models and data infrastructures have seen substantial progress, a critical bottleneck remains: the experimental validation of theoretically predicted materials [4]. Self-Driving Labs (SDLs) represent a transformative solution to this challenge, serving as autonomous validation engines that physically test and refine MGI predictions. These systems integrate robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and laboratory automation to create closed-loop environments capable of rapidly designing, executing, and analyzing thousands of experiments with minimal human intervention [4] [21]. By providing high-throughput empirical validation, SDLs close the critical feedback loop between MGI's computational predictions and real-world material performance, accelerating the entire materials innovation continuum from discovery to deployment [7].

Technical Architecture of a Self-Driving Lab

The architecture of a modern SDL functions as an integrated system of specialized layers working in concert to automate the entire scientific method. This multi-layered framework transforms digital hypotheses into physical experiments and validated knowledge.

The Five-Layer SDL Architecture

At a technical level, an SDL consists of five interlocking layers that enable autonomous operation [4]:

- Actuation Layer: Robotic systems that perform physical tasks such as dispensing, heating, mixing, and characterizing materials.

- Sensing Layer: Sensors and analytical instruments that capture real-time data on process and product properties.

- Control Layer: Software that orchestrates experimental sequences, ensuring synchronization, safety, and precision.

- Autonomy Layer: AI agents that plan experiments, interpret results, and update experimental strategies through model refinement.

- Data Layer: Infrastructure for storing, managing, and sharing data, including metadata, uncertainty estimates, and provenance.

The diagram below illustrates how these architectural layers interact to form a complete autonomous validation engine:

SDL Architecture Layers The autonomy layer represents the cognitive core of the SDL, distinguishing it from simple laboratory automation. This layer employs AI decision-making algorithms—such as Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning, and multi-objective optimization—to navigate complex experimental spaces efficiently [4]. Unlike fixed-protocol automation, the SDL can interpret unexpected results and dynamically adjust its experimental strategy, mimicking the adaptive approach of a human researcher while operating at superhuman speeds.

Classifying SDL Capabilities: Autonomy Levels and Performance

Not all automated laboratories possess the same capabilities. The autonomy spectrum ranges from basic instrument control to fully independent research systems, with significant implications for validation throughput and application scope.

SDL Autonomy Classification Framework

SDL capabilities can be classified using adapted vehicle autonomy levels, providing a standardized framework for comparing systems [22]:

| Autonomy Level | Name | Description | Key Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Assisted Operation | Machine assistance with laboratory tasks | Robotic liquid handlers, automated data analysis |

| Level 2 | Partial Autonomy | Proactive scientific assistance | Protocol generation, experimental planning tools |

| Level 3 | Conditional Autonomy | Autonomous performance of at least one cycle of the scientific method | Interpretation of routine analyses, testing of supplied hypotheses |

| Level 4 | High Autonomy | Capable of automating protocol generation, execution, and hypothesis adjustment | Can modify hypotheses based on results; operates as skilled lab assistant |

| Level 5 | Full Autonomy | Full automation of the scientific method | Not yet achieved; would function as independent AI researcher |

This classification system reveals that most current SDLs operating as validation engines exist at Levels 3 and 4, capable of running multiple cycles of hypothesis testing with decreasing human intervention [22]. The distinction between hardware and software autonomy is particularly important—some systems may have advanced physical automation (hardware autonomy) but limited AI-driven experimental design capabilities (software autonomy), and vice versa [22].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of SDL Platforms

Different SDL architectures demonstrate varying performance characteristics depending on their design focus and technological implementation. The table below compares representative SDL platforms based on key operational metrics:

| SDL Platform | Application Domain | Reported Acceleration Factor | Experimental Throughput | Key Validation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAMA BEAR [23] | Energy-absorbing materials | ~60x reduction in experiments needed [23] | 25,000+ experiments conducted [23] | 75.2% energy absorption efficiency [23] |

| AMMD [4] | Molecular discovery | 100-1000x faster than status quo [4] | 294 new molecules discovered [4] | Multiple targeted physicochemical properties [4] |

| Cloud-based SDLs [21] | Multiple domains | Up to 1000x faster than manual methods [21] | Thousands of remote experiments [21] | Variable by application domain |

| Acceleration Consortium [22] | Materials & chemistry | 100-1000x faster than status quo [22] | Large-scale parallel experimentation [22] | Optimization of multiple objectives |

Performance data demonstrates that SDLs can achieve significant acceleration—from 60x to 1000x faster than conventional methods—in validating materials predictions [4] [21] [23]. This extraordinary speed stems from both physical automation (parallel experimentation, 24/7 operation) and intellectual automation (AI-directed experimental selection that minimizes redundant tests). The throughput advantage makes previously intractable validation problems feasible, such as comprehensively exploring multi-dimensional parameter spaces that would require human centuries to test manually.

Deployment Models for MGI Validation

SDL platforms can be implemented through different operational frameworks, each offering distinct advantages for integrating with MGI validation workflows.

Comparative Analysis of SDL Deployment Architectures

Three primary models have emerged for deploying SDLs within research ecosystems, each with different implications for MGI validation efforts:

| Deployment Model | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized Facilities | Shared, facility-based access to advanced capabilities [21] | Economies of scale; high-end equipment; standardized protocols [21] | Limited flexibility; access scheduling required [21] | Large-scale validation campaigns; hazardous materials [4] |

| Distributed Networks | Modular platforms across multiple locations [21] | Specialization; flexibility; local control [21] | Coordination challenges; potential interoperability issues [21] | Niche validation tasks; iterative method development [21] |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combines local and centralized resources [21] | Balance of flexibility and power; risk mitigation [21] | Increased management complexity [21] | Multi-stage validation pipelines; collaborative projects [21] |

The hybrid model is particularly promising for MGI validation, as it allows preliminary testing to be conducted locally using distributed SDLs, while more complex, resource-intensive validation tasks are escalated to centralized facilities [21]. This approach mirrors cloud computing architectures and provides a practical pathway for balancing accessibility with capability across the materials research community.

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Validation

The operational workflow of an SDL can be understood through its experimental protocols, which transform MGI predictions into empirically validated materials properties.

Workflow of an Autonomous Validation Experiment

The end-to-end operation of an SDL follows an iterative workflow that automates the core of the scientific method. The process begins with computational predictions from the MGI framework and culminates in empirically validated materials data:

Autonomous Validation Workflow The experimental execution phase employs specific methodologies tailored to materials validation:

Bayesian Optimization Protocols: These algorithms efficiently navigate complex parameter spaces by building probabilistic models of material performance and selecting experiments that balance exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of promising areas [4] [23]. This approach has demonstrated 60-fold reductions in experiments needed to identify high-performance parametric structures compared to grid-based searches [23].

Multi-Objective Optimization: For validating materials that must balance competing properties (e.g., strength vs. weight, conductivity vs. cost), SDLs employ Pareto optimization techniques that identify optimal trade-off surfaces rather than single solutions [4].

Closed-Loop Synthesis and Characterization: Integrated platforms combine automated synthesis with inline characterization techniques (e.g., spectroscopy, chromatography) to create continuous feedback loops where material production directly informs subsequent synthesis parameters [4].

Case Study: Validating Energy-Absorbing Materials

The MAMA BEAR SDL at Boston University provides a compelling case study in autonomous validation [23]. This system specialized in discovering and validating mechanical energy-absorbing materials through thousands of autonomous experiments:

Experimental Protocol:

- Hypothesis Generation: AI algorithms proposed novel material configurations predicted to maximize energy absorption per unit mass.

- Automated Fabrication: Robotic systems prepared material samples according to specified architectural parameters.

- Mechanical Testing: Automated compression testing quantified energy absorption capacity.

- Data Analysis: Immediate processing of stress-strain curves to calculate performance metrics.

- Model Update: Bayesian optimization algorithms refined understanding of structure-property relationships.

- Iteration: The system designed subsequent experiments based on accumulated knowledge.

Validation Outcomes: Through over 25,000 autonomous experiments, MAMA BEAR discovered material structures with unprecedented energy absorption capabilities—doubling previous benchmarks from 26 J/g to 55 J/g [23]. This validated the hypothesis that non-intuitive architectural patterns could dramatically enhance mechanical performance, a finding that directly informs MGI predictive models for lightweight protective materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

SDL operations depend on both physical and digital resources. The table below details key components of an SDL validation toolkit for materials research:

| Toolkit Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Software | AI-driven experimental planning | Custom Python implementations; Ax Platform; BoTorch |

| Laboratory Robotics | Automated physical experimentation | Liquid handlers; robotic arms; automated synthesis platforms |

| In-line Characterization | Real-time material property measurement | HPLC; mass spectrometry; automated electron microscopy |

| Materials Libraries | Starting points for experimental exploration | Polymer formulations; nanoparticle precursors; catalyst libraries |

| Data Provenance Systems | Tracking experimental metadata and conditions | FAIR data practices; electronic lab notebooks; blockchain-based logging |

| Cloud Laboratory Interfaces | Remote access to centralized SDL facilities | Strateos; Emerald Cloud Lab; remotely operated characterization tools |

This toolkit enables the reproducible, traceable validation essential for verifying MGI predictions. Particularly critical are the data provenance systems that ensure all validation experiments are thoroughly documented with complete metadata, enabling other researchers to replicate findings and integrate results into broader materials knowledge graphs [23].

Self-Driving Labs represent a paradigm shift in how computational materials predictions are empirically validated. By serving as autonomous validation engines for the Materials Genome Initiative, SDLs close the critical gap between theoretical promise and practical material performance. The architectural frameworks, deployment models, and experimental protocols discussed herein demonstrate that SDLs are not merely automation tools but collaborative partners in the scientific process [23]. As these systems evolve toward higher autonomy levels and greater integration with MGI's digital infrastructure, they promise to accelerate the transformation of materials discovery from a slow, iterative process to a rapid, predictive science. The future of materials validation lies in hybrid human-AI collaboration, where researchers focus on creative problem formulation while SDLs handle the intensive work of empirical testing and validation—ultimately fulfilling MGI's vision of faster, cheaper, and more reliable materials innovation.

Co-Evolution of Simulation and Nanoscale Experimentation for Direct Model Validation

The paradigm of materials discovery and development is undergoing a revolutionary shift, moving from traditional sequential approaches to an integrated framework where simulation and experimentation co-evolve to directly validate and refine predictive models. This synergistic interaction lies at the heart of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) vision, which aims to accelerate the pace of new materials deployment by tightly integrating computation, experiment, and theory [24]. The fundamental premise of this co-evolution is that computational models guide experimental design and prioritize candidates for synthesis, while experimental results provide crucial validation and reveal discrepancies that drive model refinement. This continuous feedback loop creates a virtuous cycle of improvement that significantly reduces the time and cost associated with traditional materials development approaches.

Within the MGI context, validation represents the critical bridge between prediction and application. As computational methods advance to screen millions of potential materials in silico, the challenge shifts from mere prediction to trustworthy prediction – requiring rigorous experimental validation to establish confidence in computational results [24]. This guide examines how researchers are addressing this challenge through innovative methodologies that blend state-of-the-art simulation techniques with nanoscale experimentation, creating a new paradigm for materials innovation that is both accelerated and empirically grounded across multiple application domains.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methodologies

The co-evolution of simulation and experimentation manifests differently across various materials systems and scientific domains. The table below compares four distinct methodological approaches that exemplify this synergy, highlighting their unique characteristics and validation strengths.

Table 1: Comparison of Integrated Simulation-Experimental Validation Approaches

| Methodology | Materials System | Computational Approach | Experimental Technique | Primary Validation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Computation [25] | Nanoscale plate-like metastructures | Evolutionary algorithms evolving millions of microstructures | Nanoscale fabrication via photolithography/ALD, mechanical testing | Tensile and postbuckling compressive stiffness |

| Deep Generative Modeling [26] | Gold nanoparticles, copper sulfidation | GANs for intermediate state reconstruction | TEM, SEM, coherent X-ray diffraction imaging | Statistical similarity of generated intermediate states |

| Molecular Dynamics [27] | Stearic acid with graphene nanoplatelets | Classical MD simulations with force fields | Rheometry, densimetry | Density and viscosity measurements |

| Multi-Objective Optimization [4] | Functional molecules, battery materials | Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning | Self-driving labs with robotic synthesis & characterization | Target property achievement (e.g., conductivity, efficiency) |

Each methodology represents a distinct approach to the simulation-experimentation interplay. Evolutionary computation employs a generate-test-refine cycle where algorithms evolve populations of design candidates, with experimental validation providing the fitness criteria for selection [25]. Deep generative models learn the underlying distribution of experimental observations and generate plausible intermediate states, effectively filling gaps in experimental temporal resolution [26]. Molecular dynamics simulations model interactions at the atomic and molecular level, with experimental measurements of bulk properties validating the force field parameters and simulation setup [27]. The self-driving lab approach represents the ultimate integration, where AI-driven decision-making directly controls experimental execution in a closed-loop system [4].

Experimental Protocols for Direct Model Validation

Nanoscale Fabrication and Mechanical Characterization of Metastructures

The validation of evolutionary computation models for nanoscale metastructures requires precisely controlled fabrication and mechanical testing protocols [25]:

Fabrication Process: Metastructures with corrugated patterns are fabricated using photolithography and atomic layer deposition (ALD) techniques. These methods enable precise control at the nanoscale, creating structures with defined geometric parameters including hexagonal diameter (Dhex), rib width (ghex), thickness (t), height (h), length (L), and width (W).

Mechanical Testing: Experimental calibration of mechanical characteristics involves both tensile testing and compressive postbuckling analysis. Samples are subjected to axial displacement control testing while clamped at both ends, mimicking the boundary conditions used in corresponding finite element simulations.

Finite Element Validation: Experimentally tested structures are replicated in Abaqus R2017x finite element software using dynamic/implicit analysis with nonlinear geometry (Nlgeom) to introduce structural imperfection. The close agreement between experimental results and simulation outputs validates the numerical models, which then generate thousands of data points for developing evolutionary computation models.

Molecular Dynamics Validation for Thermal Energy Storage Materials

The protocol for validating molecular dynamics simulations of nano-enhanced phase change materials involves coordinated computational and experimental approaches [27]:

Sample Preparation: Stearic acid (SA) is combined with graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) of 6-8 nm thickness using a two-step method. Nanoparticles are dispersed at concentrations of 2 wt.%, 4 wt.%, and 6 wt.% through mechanical stirring and ultrasonication to ensure homogeneous distribution.

Experimental Characterization: Viscosity measurements are performed using a rheometer with concentric cylinder geometry, with temperature controlled from 343 K to 373 K. Density measurements employ an oscillating U-tube densimeter calibrated with Milli-Q water at atmospheric pressure.

Molecular Dynamics Setup: Simulations model a system containing one GNP nanoparticle (18-layer graphene nanoplate) embedded in 2123 SA molecules. Simulations run in a temperature range from 353 K to 378 K at 0.1 MPa pressure, using the TraPPE force field for SA and AIREBO potential for graphene-carbon interactions.

Validation Metrics: The radial distribution function analyzes molecular orientation and alignment near nanoparticle surfaces, while simulated density and viscosity values are directly compared against experimental measurements to validate the force field parameters and simulation methodology.

Workflow Visualization of Integrated Validation Approaches

The co-evolution of simulation and experimentation follows systematic workflows that enable continuous model refinement. The diagram below illustrates the generalized validation cycle that underpins these approaches.

Figure 1: Cyclical Workflow for Model Validation

This workflow highlights the iterative nature of model validation, where discrepancies between predicted and measured properties drive model refinement. The materials database serves as a cumulative knowledge repository, capturing both successful and failed predictions to inform future computational campaigns [24]. This cyclical process continues until models achieve sufficient predictive accuracy for the target application space.

For specific applications like analyzing material transformations from sparse experimental data, specialized computational workflows are employed, as shown in the following diagram of the deep generative model approach:

Figure 2: Generative Model Validation Workflow

This specialized approach addresses the common challenge of sparse temporal observations in nanoscale experimentation. By training generative adversarial networks (GANs) on experimental images, the method creates a structured latent space that captures the essential features of material states [26]. Monte Carlo sampling within this latent space generates plausible intermediate states and transformation pathways that have not been directly observed experimentally, effectively augmenting sparse experimental data with statistically grounded interpolations.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of integrated simulation-experimentation approaches requires specific materials and instrumentation. The table below details key research reagents and their functions in these validation workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Integrated Validation

| Category | Specific Materials/Instruments | Function in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles | Graphene nanoplatelets (6-8 nm thickness) [27] | Enhance thermal conductivity in phase change materials; enable study of nanoparticle-matrix interactions |

| Phase Change Materials | Stearic acid, lauric acid, palmitic acid [27] | Serve as model organic energy storage materials with well-characterized properties for validation |

| Fabrication Materials | Photoresists, silicon substrates [25] [28] | Enable nanoscale patterning of metastructures via photolithography and electron-beam lithography |

| Characterization Instruments | Atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) [28] | Provide nanoscale chemical imaging with ~10 nm resolution for subsurface feature characterization |

| Computational Software | Abaqus FEA, molecular dynamics packages [25] [27] | Implement finite element analysis and molecular simulations for model prediction and validation |

| AI Frameworks | Generative adversarial networks, evolutionary algorithms [25] [26] | Create models that learn from experimental data and generate design candidates or intermediate states |

These research reagents enable the precise nanoscale fabrication, characterization, and computational modeling required for direct model validation. The selection of graphene-based nanomaterials is particularly notable due to their exceptional properties and widespread use across multiple validation studies [25] [27]. Similarly, organic phase change materials like stearic acid provide excellent model systems due to their well-understood chemistry and relevance to energy applications.

The co-evolution of simulation and nanoscale experimentation represents a paradigm shift in materials validation, moving beyond simple correlative comparisons to deeply integrated approaches where each modality informs and refines the other. As the Materials Genome Initiative advances, the closed-loop validation approaches exemplified by self-driving labs promise to further accelerate this process, creating autonomous systems that continuously refine models based on experimental outcomes [4].

The future of model validation will likely see increased emphasis on uncertainty quantification and data provenance, ensuring that both computational predictions and experimental measurements include well-characterized uncertainty bounds [24]. Additionally, the development of standardized data formats and shared infrastructure will be crucial for creating the collaborative ecosystems needed to validate materials genome predictions across institutions and disciplines. As these trends converge, the vision of accelerated materials discovery and deployment through integrated simulation and experimentation will become increasingly realized, ultimately transforming how we discover, design, and deploy advanced materials for addressing society's most pressing challenges.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Generating Predictive Surrogate Models

Surrogate models, also known as metamodels or reduced-order models, are simplified mathematical constructs that emulate the behavior of complex, computationally expensive systems. By using machine learning (ML) algorithms to learn the input-output relationships from a limited set of full-scale simulations or experimental data, these models can predict system responses with high accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) has been instrumental in advancing this paradigm, fostering a culture where computation, data, and experiment are tightly integrated to accelerate materials discovery and design. The core premise of the MGI is that such integration can dramatically speed up the process of bringing new materials from the laboratory to practical deployment.

Artificial intelligence has transformed surrogate modeling from a niche technique to a powerful, scalable approach. Modern AI surrogate models can process vast multidimensional parameter spaces, handle diverse data types, and provide predictions in milliseconds rather than hours. This capability is particularly valuable in fields like materials science and drug development, where traditional simulation methods often present prohibitive computational bottlenecks. Research demonstrates that AI-surrogate models can predict properties of materials with near-ab initio accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling the screening of thousands of materials in the time previously needed for one.

Core Methodologies and Algorithmic Approaches

Fundamental Workflow for Surrogate Model Development

The development of robust AI-surrogate models follows a systematic workflow that ensures accuracy and generalizability. The process begins with data acquisition, where a representative set of input parameters and corresponding output responses are collected through high-fidelity simulations or experiments. This dataset is then partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets. The next critical step involves selecting an appropriate numerical representation of the input data that captures essential features while maintaining physical invariances. For materials systems, representations must be invariant to translation, rotation, and permutation of atoms, while also being unique, differentiable, and computationally efficient to evaluate.

Following data preparation, machine learning algorithms are trained to map the input representations to the target outputs. The training process typically involves minimizing a loss function that quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and ground truth values. Model performance is then rigorously evaluated on the held-out test data using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). Finally, the validated model can be deployed for rapid prediction and exploration of the design space. This workflow embodies the MGI approach of tightly integrating computation, data, and experiment.

Key Algorithmic Frameworks

Several algorithmic frameworks have emerged as particularly effective for constructing surrogate models across different domains:

Kernel-Based Methods including Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) provide probabilistic predictions and naturally quantify uncertainty. These methods are especially valuable when data is limited and uncertainty estimation is crucial. GPR employs kernels to measure similarity between data points, constructing a distribution over possible functions that fit the data.

Neural Network Approaches range from standard Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) to specialized architectures like Moment Tensor Potentials (MTP). Deep neural networks can automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw input data, making them particularly suited for complex, high-dimensional problems. Research shows MLP models achieving up to 98.4% accuracy in predicting construction schedule status, demonstrating their capability for practical forecasting applications.

Tree-Based Ensemble Methods such as Random Forests and XGBoost combine multiple decision trees to create robust predictions that resist overfitting. These methods typically provide feature importance metrics, offering insights into which input parameters most significantly impact outputs. Studies applying XGBoost to predict academic performance achieved an R² of 0.91, highlighting the power of these approaches for educational forecasting.

Polynomial and Radial Basis Functions represent more traditional approaches that remain effective for certain problem types, particularly those with smooth response surfaces and lower dimensionality.

Performance Comparison Across Domains

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The effectiveness of surrogate modeling approaches is quantitatively assessed through multiple metrics that capture different aspects of predictive performance.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Surrogate Models Across Applications

| Domain | Algorithm | Performance Metric | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Science | MBTR + KRR | Mean Absolute Error | <1 meV/atom | [29] |

| Materials Science | Multiple Representations | Relative Error | <2.5% | [29] |

| Educational Analytics | XGBoost | R² | 0.91 | [30] |

| Educational Analytics | XGBoost | MSE Reduction | 15% | [30] |

| Construction Management | MLP | Schedule Prediction Accuracy | 98.4% | [31] |

| Construction Management | MLP | Quality Prediction Accuracy | 94.1% | [31] |

| CO2 Capture Optimization | ALAMO | Computational Efficiency | Highest | [32] |

| CO2 Capture Optimization | Kriging/ANN | Convergence Iterations | 2 | [32] |

Materials Science Applications

In materials science, surrogate models have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting formation enthalpies across diverse chemical systems. Research on ten binary alloy systems (AgCu, AlFe, AlMg, AlNi, AlTi, CoNi, CuFe, CuNi, FeV, and NbNi) encompassing 15,950 structures found that multiple state-of-the-art representations and learning algorithms consistently achieved prediction errors of approximately 10 meV/atom or less across all systems. Crucially, models trained simultaneously on multiple alloy systems showed deviations in prediction errors of less than 1 meV/atom compared to systems-specific models, demonstrating the transfer learning capability of these approaches.

The MGI framework has been particularly instrumental in advancing these capabilities. By promoting standardized data formats, shared computational tools, and integrated workflows, the initiative has enabled the development of surrogate models that can generalize across material classes and composition spaces. This infrastructure allows researchers to build on existing knowledge rather than starting from scratch for each new material system.

Drug Discovery and Development Applications

In pharmaceutical research, AI-driven surrogate models are accelerating multiple stages of drug development. These models can predict protein structures with high accuracy, forecast molecular properties, and optimize clinical trial designs. For target identification, AI algorithms analyze complex biological datasets to uncover disease-causing targets, with machine learning models subsequently predicting interactions between these targets and potential drug candidates. DeepMind's AlphaFold system has revolutionized protein structure prediction, providing invaluable insights for therapeutic discovery.