Validating High-Throughput Computational Screening: A Framework for Robust Hit Identification and Lead Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating results from High-Throughput Computational Screening (HTCS).

Validating High-Throughput Computational Screening: A Framework for Robust Hit Identification and Lead Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating results from High-Throughput Computational Screening (HTCS). It covers the foundational principles of HTCS validation, explores advanced methodological and statistical frameworks for ensuring data reliability, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous protocols for experimental and comparative validation. By integrating insights from recent advancements in machine learning, artificial intelligence, and statistical analysis, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools necessary to enhance the accuracy and predictive power of their computational screening campaigns, thereby accelerating the drug discovery pipeline and reducing late-stage failures.

The Critical Role of Validation in High-Throughput Computational Screening

Defining Validation in the Context of HTCS and its Impact on Drug Discovery

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and its computational counterpart, High-Throughput Computational Screening (HTCS), have revolutionized early drug discovery by enabling the rapid evaluation of vast chemical libraries against biological targets. Validation in this context refers to the rigorous process of ensuring that screening assays and computational models are biologically relevant, pharmacologically predictive, and robustly reproducible before their implementation in large-scale campaigns. For researchers and drug development professionals, proper validation serves as the critical gatekeeper, determining which screening results can be trusted to guide costly downstream development efforts. Without comprehensive validation, HTS/HTCS initiatives risk generating misleading data that can derail entire drug discovery programs through false leads and wasted resources.

Core Principles of HTS/HTCS Validation

Validation of HTS assays and computational models encompasses multiple dimensions, each addressing specific aspects of reliability and relevance. The process begins with assay validation, which ensures that the biological test system accurately reflects the target interaction and produces consistent, measurable results. For computational HTCS, method validation confirms that the chosen algorithms, force fields, and parameters can reliably predict biological activity or material properties.

A cornerstone of assay validation is the statistical assessment of performance using metrics that measure the separation between positive and negative controls. The Z'-factor is widely used for this purpose, providing a quantitative measure of assay quality and robustness [1]. Additionally, Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) has been recognized as a more recent statistical approach for assessing data quality in HTS assays, particularly for evaluating the strength of difference between two groups [2].

For computational screening methods, validation often involves comparison against experimental data or higher-level theoretical calculations to establish predictive accuracy. In material science applications, such as screening metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), studies have demonstrated that the choice of force fields and partial charge assignment methods significantly impacts material rankings, highlighting the necessity of quantifying this uncertainty [3].

Experimental Validation Protocols and Metrics

Plate Uniformity and Signal Variability Assessment

A fundamental requirement for HTS assay validation involves comprehensive plate uniformity studies to assess signal consistency across the entire microplate format. The Assay Guidance Manual recommends a structured approach using three types of control signals [4]:

- "Max" signal: Represents the maximum assay response, typically measured in the absence of test compounds for inhibition assays or with a maximal agonist concentration for activation assays.

- "Min" signal: Represents the background or basal signal, measured in the absence of the target activity.

- "Mid" signal: An intermediate response point, typically generated using an EC~50~ concentration of a reference compound.

These studies should be conducted over multiple days (2-3 days depending on whether the assay is new or being transferred) using independently prepared reagents to establish both within-day and between-day reproducibility [4]. The data collected enables the calculation of critical quality metrics that determine an assay's suitability for HTS implementation.

Key Statistical Parameters for Assay Validation

The following table summarizes essential quantitative metrics used in HTS/HTCS validation:

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for HTS/HTCS Assays

| Metric | Formula/Definition | Application | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor [1] | 1 - (3σ~p~ + 3σ~n~) / |μ~p~ - μ~n~| | Assay quality assessment | Z' > 0.5: Excellent; Z' > 0: Acceptable |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio [2] | (μ~p~ - μ~n~) / σ | Assay robustness | Higher values indicate better detection power |

| Signal Window [2] | (μ~p~ - μ~n~) / √(σ~p~² + σ~n~²) | Assay quality assessment | ≥2 for robust assays |

| Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) [2] | (μ~p~ - μ~n~) / √(σ~p~² + σ~n~²) | Hit selection in replicates | Custom thresholds based on effect size |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (σ/μ) × 100% | Signal variability | Typically <20% for HTS |

Reagent Stability and Compatibility Testing

Comprehensive validation requires characterization of reagent stability under both storage conditions and actual assay environments. Key considerations include [4]:

- Determining freeze-thaw cycle tolerance for reagents subjected to repeated freezing and thawing

- Assessing DMSO compatibility by testing assay performance across expected solvent concentrations (typically 0-10%, with <1% recommended for cell-based assays)

- Establishing storage stability for both individual reagents and prepared mixtures

- Verifying reaction stability over the projected assay timeline to accommodate potential operational delays

Validation in Computational Screening (HTCS)

While experimental HTS relies heavily on statistical validation of physical assays, computational HTCS requires distinct validation approaches to ensure predictive accuracy. The validation process for HTCS must address multiple sources of uncertainty inherent in virtual screening methodologies.

Force Field and Parameter Validation

In molecular simulations for drug discovery or materials science, the choice of computational parameters significantly impacts screening outcomes. Studies examining the screening of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for carbon capture demonstrate that partial charge assignment is the prevailing source of uncertainty in material rankings [3]. Additionally, the selection of Lennard-Jones parameters represents a considerable source of variability. These findings highlight that obtaining high-resolution material rankings using a single molecular modeling approach is challenging, and uncertainty estimation is essential for MOFs shortlisted via HTCS workflows [3].

Methodological Validation in Predictive Modeling

For computational models predicting chemical-protein interactions, validation must address the significant class imbalance characteristic of HTS data, where active compounds represent only a small fraction of screened libraries [5]. The DRAMOTE method, for instance, employs modified minority oversampling techniques to enhance prediction precision for activity status in individual assays [5]. Model performance is typically validated through k-fold cross-validation (often 5-fold for large datasets) to compute representative, non-biased estimates of predictive accuracy [5].

Advanced Validation Techniques

High-Content and Phenotypic Screening Validation

As HTS evolves beyond target-based approaches toward phenotypic screening, validation requirements have expanded to include morphological and functional endpoints. These complex assays require validation of [6]:

- Cell health and viability parameters under screening conditions

- Specificity of phenotypic readouts for the biological process being investigated

- Reproducibility of complex multiparameter outputs

- Benchmarking against reference compounds with known mechanisms of action

Stem Cell and Complex Model System Validation

The integration of human stem cell (hESC and iPSC)-derived models in toxicity screening introduces additional validation challenges [7]. These include:

- Characterizing differentiation consistency to ensure uniform cellular models across screening plates

- Establishing biological relevance through functional validation of target engagement

- Demonstrating scalability compatible with HTS formats while maintaining physiological relevance

Impact on Drug Discovery Outcomes

Enhancing Lead Identification and Optimization

Properly validated HTS/HTCS approaches directly impact drug discovery efficiency by [6]:

- Reducing false positive rates through robust assay design and computational modeling

- Accelerating hit-to-lead transitions with high-quality structure-activity relationship (SAR) data

- Enabling identification of novel chemotypes through reliable phenotypic screening

- Supporting lead optimization with predictive ADME/Tox profiling early in discovery

Risk Mitigation in Development Pipelines

Comprehensive validation serves as a crucial risk mitigation strategy by [6]:

- Identifying ineffective compounds early, reducing downstream development costs

- Preventing late-stage failures due to inadequate target engagement or unexpected toxicity

- Providing high-quality data for informed decision-making on program progression

- Enabling resource allocation to the most promising therapeutic candidates

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS/HTCS Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates (96-, 384-, 1536-well) [2] | Platform for assay miniaturization | Higher density plates require reduced volumes (1-10 μL) |

| Reference Agonists/Antagonists [4] | Generation of control signals (Max, Min, Mid) | Well-characterized potency and selectivity required |

| Cell Lines (Engineered or primary) [7] | Biological relevance for cell-based assays | Cryopreserved cells facilitate consistency across screens |

| Charge Equilibration Schemes (EQeq, PQeq) [3] | Partial charge assignment in computational screening | Less accurate but computationally efficient vs. ab initio methods |

| Ab Initio Charge Methods (DDEC, REPEAT) [3] | Accurate electrostatic modeling in molecular simulations | Computationally demanding but higher accuracy for periodic structures |

| Fluorescent/Luminescent Probes [6] | Signal generation for detection | Must demonstrate minimal assay interference |

| Label-Free Detection Reagents (SPR-compatible) [6] | Real-time monitoring of molecular interactions | Eliminates potential artifacts from labeling |

Validation Workflows and Decision Pathways

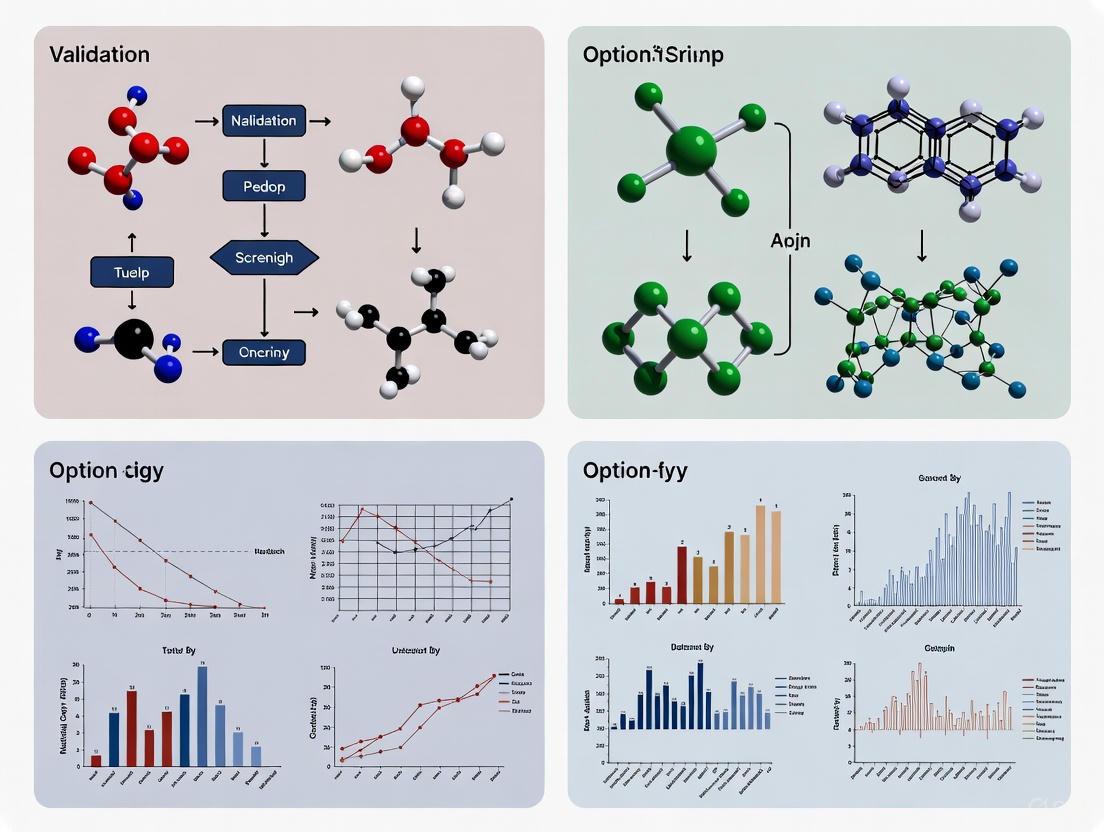

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive validation pathway for HTS assays and computational screening methods, integrating both experimental and computational approaches:

HTS/HTCS Validation Workflow

Validation constitutes the foundational framework that ensures the reliability and translational value of both experimental HTS and computational screening data. As screening technologies continue to evolve toward increasingly complex phenotypic assays and sophisticated in silico models, validation strategies must similarly advance to address new challenges in reproducibility and predictive accuracy. For drug development professionals, investing in comprehensive validation protocols represents not merely a procedural hurdle but a strategic imperative that directly impacts development timelines, resource allocation, and ultimately, the success of drug discovery programs. Future directions in HTS/HTCS validation will likely incorporate greater integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to further enhance predictive capabilities while maintaining the rigorous standards necessary for pharmaceutical development.

The paradigm of discovery in biology and materials science has fundamentally shifted, driven by an explosion in data volume and computational power. The global datasphere is projected to reach 181 Zettabytes by the end of 2025, within which biological data, especially from "omics" technologies, is growing at a hyper-exponential rate [8]. In this context, high-throughput computational screening (HTCS) has emerged as a cornerstone methodology, enabling researchers to rapidly interrogate thousands to millions of chemical compounds, materials, or drug candidates in silico before committing to costly laboratory experiments. The core challenge, however, has evolved from merely generating vast datasets to ensuring their quality, reliability, and most critically, their biological relevance. This transition is redefining the competitive landscape, where the ability to connect data and ensure its precision is becoming a greater advantage than the ability to generate it in the first place [8]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of HTCS methodologies, focusing on the core principles that bridge the gap from raw data quality to physiologically and therapeutically meaningful insights.

Comparative Analysis of High-Throughput Screening Methodologies

The selection of an appropriate computational screening methodology is a critical first step that dictates the balance between throughput, accuracy, and cost. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of four prominent approaches, highlighting their respective performance characteristics, computational demands, and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of High-Throughput Computational Screening Methods

| Method | Typical Throughput (Molecules/Day)* | Relative Computational Cost | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Empirical xTB (sTDA/sTD-DFT-xTB) [9] | Hundreds | Very Low (~1%) | MAE for ΔEST: ~0.17 eV [9] | Extreme speed; good for relative ranking and large library screening | Quantitative inaccuracies for absolute property values |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [10] | Tens | High (Benchmark) | High correlation with experimental piezoelectric constants (e.g., for γ-glycine, predicted d33 = 10.72 pC/N vs. experimental 11.33 pC/N) [10] | High accuracy for a wide range of electronic properties; considered a "gold standard" | Computationally expensive; less suitable for the largest libraries |

| Classical Machine Learning (RF, SVM) [11] | Thousands to Millions | Very Low (after training) | Varies by model and dataset; excels at classification and rapid interaction prediction [11] | Highest throughput for pre-trained models; excellent for initial triage | Dependent on quality and breadth of training data; limited extrapolation |

| Deep Learning (GNNs, Transformers) [11] [12] | Thousands to Millions | High (training) / Low (deployment) | Superior performance on complex tasks like multi-target drug discovery and DDI prediction [11] [12] | Ability to learn complex, non-linear patterns from raw data | "Black box" nature; requires large, curated datasets; risk of poor generalizability [12] |

*Throughput is highly dependent on system complexity, computational resources, and specific implementation.

The data reveals a clear trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy. Semi-empirical methods like xTB offer an unparalleled >99% reduction in cost compared to conventional Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT), making them indispensable for the initial stages of screening vast chemical spaces, despite a noted mean absolute error (MAE) of ~0.17 eV for key properties like the singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔEST) [9]. In contrast, DFT provides higher quantitative accuracy, validated against experimental measurements, but at a significantly higher computational cost, positioning it for lead optimization and validation [10]. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models operate on a different axis, offering immense throughput after the initial investment in model training, but their performance is intrinsically linked to the quality and representativeness of the underlying training data [11] [12].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating the predictions of any HTCS protocol is paramount to establishing biological and physical relevance. The following sections detail two representative experimental frameworks from recent literature: one for materials informatics and another for drug discovery.

Validation Protocol for Organic Piezoelectric Materials Screening

This protocol, adapted from a benchmark study of 747 molecules, outlines the steps for validating semi-empirical quantum mechanics methods against higher-fidelity calculations and experimental data [9].

- 1. Dataset Curation: A large, diverse set of experimentally characterized TADF emitters (747 molecules) was assembled from the literature using automated text mining. The set included diverse molecular architectures (donor-acceptor, multi-resonance). Initial 3D structures were generated from SMILES strings using RDKit [9].

- 2. Conformational Sampling & Geometry Optimization: A systematic conformational search for each molecule was performed using the Conformer-Rotamer Ensemble Sampling Tool (CREST) coupled with the GFN2-xTB semi-empirical Hamiltonian. The lowest-energy conformer was then subjected to a final, tight geometry optimization at the GFN2-xTB level to obtain the equilibrium ground-state (S0) structure [9].

- 3. Excited-State Calculations (Hybrid Protocol): Single-point excited-state property calculations were performed on the GFN2-xTB-optimized geometries using two efficient methods:

- Simplified Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (sTDA-xTB)

- Simplified Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (sTD-DFT-xTB)

- These calculations employed the ALPB implicit solvent model (e.g., toluene) to approximate environmental effects [9].

- 4. Data Analysis and Benchmarking: Key photophysical properties (e.g., ΔEST, emission wavelengths) were extracted. The internal consistency between sTDA-xTB and sTD-DFT-xTB was assessed using Pearson correlation (r ≈ 0.82 for ΔEST). The methods were then validated against 312 experimental ΔEST values, calculating the Mean Absolute Error (MAE ~0.17 eV). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to reduce dimensionality and identify key design rules [9].

Validation Protocol for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

This protocol summarizes a common ML workflow for predicting drug-target interactions, a critical task in systems pharmacology [11].

- 1. Data Source Integration: Data is aggregated from multiple public and proprietary sources. Key databases include:

- DrugBank: For drug-target pairs, mechanisms, and chemical data.

- ChEMBL: For bioactivity data of drug-like small molecules.

- TTD: For therapeutic target and pathway information.

- KEGG: For genomic and pathway data integration [11].

- 2. Feature Representation: Molecules are encoded into a machine-readable format using:

- Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP): Boolean vectors representing molecular substructures.

- Graph Representations: Atoms and bonds represented as nodes and edges for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

- Target (Protein) Representation: Sequences from amino acid strings or 3D structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Pre-trained protein language models (e.g., ESM, ProtBERT) can also be used to generate informative embeddings [11].

- 3. Model Training and Multi-Task Learning: A model (e.g., a GNN or Random Forest) is trained on known drug-target interaction pairs. For multi-target prediction, a multi-task learning framework is often employed, where the model learns to predict interactions against a panel of targets simultaneously, leveraging shared information across tasks to improve generalizability [11].

- 4. Experimental Validation and Hit Triage: Predicted active compounds are prioritized for experimental validation in assays. This often involves:

- Primary Screening: Testing against the intended target(s) to confirm activity.

- Counter-Screening: Testing against unrelated targets to assess selectivity and identify potential off-target effects (promiscuity).

- Cellular Assays: Moving from biochemical to cell-based assays to establish efficacy and preliminary toxicity in a more physiologically relevant context [11].

Workflow Visualization: From Computation to Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for high-throughput computational screening and its validation, as described in the protocols above.

Diagram 1: Integrated High-Throughput Screening Workflow. This diagram maps the parallel paths of quantum mechanics (left) and machine learning (right) approaches, converging on hit prioritization and essential experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of HTCS and its subsequent experimental validation relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources that form the foundation of a modern screening pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTCS

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Screening | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CREST & xTB [9] | Computational Software | Semi-empirical quantum chemical calculation for conformational sampling and geometry optimization. | Enables fast, automated conformational searches and geometry optimization for large molecular datasets. |

| CrystalDFT [10] | Computational Database | A curated database of DFT-predicted electromechanical properties for organic molecular crystals. | Provides a benchmarked resource for piezoelectric properties, accelerating materials discovery. |

| Cell-Based Assays [13] [14] | Experimental Reagent / Platform | Provides physiologically relevant data in early drug discovery by assessing compound effects in living systems. | Critical for functional assessment; the leading technology segment in the HTS market (39.4% share) [13]. |

| ChEMBL & DrugBank [11] | Data Resource | Manually curated databases providing bioactivity, drug-target, and pharmacological data. | Essential for training, benchmarking, and validating machine learning models in drug discovery. |

| ToxCast Database [15] | Data Resource | EPA's high-throughput screening data for evaluating potential health effects of thousands of chemicals. | Provides open-access in vitro screening data for computational toxicology and safety assessment. |

| RDKit [9] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics and machine learning, used for converting SMILES to 3D structures. | Fundamental for molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and structure manipulation. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [11] | Computational Model | A class of deep learning models that operate directly on molecular graph structures. | Excels at learning from molecular structure and biological networks for multi-target prediction. |

| Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) [13] | Technology Platform | Automated screening systems capable of testing millions of compounds in a short timeframe. | Enables comprehensive exploration of chemical space; a rapidly growing segment (12% CAGR) [13]. |

The journey from data quality to biological relevance is the defining challenge in contemporary high-throughput computational screening. As the field advances, driven by ever-larger datasets and more sophisticated AI models, the principles of rigorous validation, multi-method triangulation, and constant feedback from experimental reality become non-negotiable. The competitive advantage no longer lies solely in generating data but in the robust frameworks that ensure its precision, interpretability, and ultimate translation into biologically and therapeutically meaningful outcomes [8]. Success in this new frontier demands a synergistic approach, leveraging the speed of semi-empirical methods and ML for breadth, the accuracy of DFT for depth, and the irreplaceable validation of wet-lab experiments for truth.

High-throughput computational screening (HTS) has revolutionized discovery processes across scientific domains, from drug development to materials science. By leveraging computational power to evaluate thousands to millions of candidates in silico, researchers can rapidly identify promising candidates for further experimental validation. This approach significantly reduces the time and cost associated with traditional trial-and-error methods. However, as with any methodological approach, computational screening carries inherent limitations and potential sources of error that can significantly impact the validity, reliability, and real-world applicability of its predictions. This guide examines these limitations through a comparative analysis of screening methodologies across multiple disciplines, providing researchers with a framework for critical evaluation and validation of computational screening results.

Computational screening methodologies share several common limitations that can introduce errors and biases into screening outcomes. Understanding these fundamental constraints is essential for proper interpretation of screening data.

Data Quality and Availability Issues

The foundation of any computational screening endeavor is the data used for training, validation, and testing. Multiple factors related to data can introduce significant errors:

Limited Dataset Size: Many screening initiatives, particularly in specialized domains, suffer from insufficient training data. In ophthalmic AI screening for refractive errors, researchers noted that previous models "did not undergo the testing phase due to the small-size dataset limitation; thus, the actual accuracy score is not yet determined" [16]. Small datasets increase the risk of overfitting and reduce model generalizability.

Data Imbalance: Screening datasets frequently exhibit extreme imbalance between active and inactive compounds or materials. As noted in drug discovery screening, "the number of hits in databases is small, there is a huge imbalance in favor of inactive compounds, which makes it hard to extract substructures of actives" [17]. This imbalance can skew model performance metrics and reduce sensitivity for identifying true positives.

Inconsistent Data Quality: Variability in experimental protocols, measurement techniques, and data reporting standards introduces noise and systematic errors. In nanomaterials safety screening, researchers highlighted challenges with "manual data processing" and the need for "automated data FAIRification" to ensure data quality and reproducibility [18].

Methodological and Algorithmic Limitations

The computational methods themselves introduce specific limitations and potential error sources:

Model Generalization Challenges: Models trained on specific populations or conditions often fail to generalize to new contexts. Researchers developing ophthalmic screening tools noted that models "trained with the eye image of the East Asian population, mainly of Chinese and Korean ethnicity" necessitated "further validation" for other ethnic groups [16]. This highlights the importance of population-representative training data.

Approximation in Simulations: Computational screening often relies on approximations that may not fully capture real-world complexity. In screening bimetallic nanoparticles for hydrogen evolution, researchers found that "favorable adsorption energies are a necessary condition for experimental activity, but other factors often determine trends in practice" [19]. This demonstrates how simplified models may miss critical contextual factors.

Architectural Constraints: The choice of computational architecture can limit detection capabilities. In vision screening, researchers found that "single-branch CNNs were not able to differentiate well enough the subtle variations in the morphological patterns of the pupillary red reflex," necessitating development of more sophisticated multi-branch architectures [16].

Validation and Experimental Translation Gaps

A critical phase in any screening pipeline is the validation of computational predictions against experimental results:

Silent Data Errors: In semiconductor screening, "silent data errors" (SDEs) represent a significant challenge where "if engineers don't look for them, then they don't know they exist" [20]. These errors can cause "intermittent functional failures" that are difficult to detect with standard testing protocols.

Low Repeatability: Some screening errors manifest as low-repeatability failures. As noted in semiconductor testing, "low repeatability of some SDE failures points to timing glitches, which can result from longer or shorter path delays" [20]. This intermittent nature makes detection and validation particularly challenging.

Experimental Disconnect: Computational predictions often fail to account for practical experimental constraints. In materials screening, researchers emphasized the importance of assessing "dopability and growth feasibility, recognizing that a material's theoretical potential is only valuable if it can be reliably produced and incorporated into devices" [21].

Comparative Analysis of Screening Limitations Across Domains

Table 1: Domain-Specific Limitations in Computational Screening

| Domain | Primary Screening Objectives | Key Limitations | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ophthalmic Disease Screening | Refractive error classification from corneal images [16] | Limited dataset size, ethnic representation bias, architectural constraints in pattern recognition | Reduced accuracy for underrepresented populations, misclassification of subtle refractive patterns |

| Drug Discovery | Compound activity prediction, toxicity assessment [17] [22] | Data imbalance, assay interference, compound artifacts, high false positive rates | Missed promising compounds, resource waste on false leads, limited predictive accuracy for novel chemistries |

| Materials Science | Identification of novel semiconductors, MOFs for gas capture [21] [23] [24] | Approximation in density functional theory, incomplete property prediction, synthesis feasibility gaps | Promising theoretical candidates may not be synthesizable, overlooked materials due to incomplete property profiling |

| Nanomaterials Safety | Hazard assessment, toxicity ranking [18] | Challenges in dose quantification, assay standardization, data FAIRification | Inaccurate toxicity rankings, limited reproducibility, difficulties in cross-study comparison |

| Semiconductor Development | Performance prediction, defect detection [20] | Silent data errors, low repeatability failures, testing exhaustion | Field failures in data centers, difficult-to-detect manufacturing defects, reliability issues |

Experimental Protocols for Error Mitigation

Cross-Domain Validation Framework

Robust validation requires multiple complementary approaches to identify and mitigate screening errors:

Diagram 1: Multi-stage validation workflow for computational screening. This iterative process identifies errors at different stages of development.

Data Quality Assurance Protocol

Ensuring data quality requires systematic approaches to data collection, annotation, and processing:

Standardized Data Collection: In vision screening, researchers implemented rigorous protocols including "uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), slit lamp biomicroscope examination, fundus photography, objective refraction using an autorefractor, and subjective refraction" to ensure consistent, high-quality input data [16].

Automated Data Processing: For nanomaterial safety screening, researchers developed "automated data FAIRification, preprocessing and score calculation" to reduce manual processing errors and improve reproducibility [18].

Multi-Source Validation: Leveraging multiple data sources helps identify systematic biases. PubChem provides access to HTS data from "various sources including university, industry or government laboratories" enabling cross-validation of screening results [22].

Advanced Architectural Solutions

Addressing methodological limitations often requires specialized computational architectures:

Multi-Branch Feature Extraction: For challenging pattern recognition tasks such as refractive error detection from corneal images, researchers developed a "multi-branch convolutional neural network (CNN)" with "multi-scale feature extraction pathways" that were "pivotal in effectively addressing overlapping red reflex patterns and subtle variations between classes" [16].

Multi-Algorithm Validation: In co-crystal screening, researchers compared "COSMO-RS implementations" with "random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and deep neural network (DNN) ML models" to identify the most accurate approach for their specific application [25].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Error Rates and Mitigation Effectiveness Across Screening Domains

| Screening Domain | Reported Performance Metrics | Limitation Impact | Mitigation Strategy Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ophthalmic AI Screening | 91% accuracy, 96% precision, 98% recall, AUC 0.989 [16] | Ethnic bias reduced generalizability | Multi-branch CNN architecture improved subtle pattern recognition |

| Hydrogen Evolution Catalysis | ~50% of bimetallic space excludable via adsorption screening [19] | Necessary but insufficient condition | Combined screening criteria improved prediction accuracy |

| Semiconductor Screening | SDE rates of 100-1000 DPPM attributed to single core defects [20] | Silent data errors required extensive testing | Improved test coverage, path delay defect screening |

| Co-crystal Prediction | COSMO-RS more predictive than ML models for co-crystal formation [25] | Method-dependent accuracy variations | Multi-method comparison identified optimal approach |

| MOF Iodine Capture | Machine learning prediction with multiple descriptor types [24] | Incomplete feature representation | Structural + molecular + chemical descriptors improved accuracy |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources for Screening Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Error Mitigation | Domain Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repository Platforms | PubChem, ChEMBL, eNanoMapper [17] [22] [18] | Standardized data access, cross-validation, metadata management | Drug discovery, nanomaterials safety, chemical toxicity |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, SVM, Deep Neural Networks [25] [24] | Pattern recognition, predictive modeling, feature importance analysis | Materials discovery, co-crystal prediction, toxicity assessment |

| Computational Architecture | Multi-branch CNN [16] | Multi-scale feature extraction, subtle pattern discrimination | Medical image analysis, complex pattern recognition |

| Validation Software | ToxFAIRy, Orange3-ToxFAIRy [18] | Automated data preprocessing, toxicity scoring, FAIRification | Nanomaterials hazard assessment, high-throughput screening |

| Simulation Methods | Density Functional Theory, Monte Carlo simulations [21] [24] | Property prediction, adsorption behavior modeling, stability assessment | Materials discovery, semiconductor development, MOF screening |

Computational screening represents a powerful approach for accelerating discovery across numerous scientific domains, yet its effectiveness is constrained by characteristic limitations and error sources. Data quality issues, methodological constraints, and validation gaps can significantly impact screening reliability if not properly addressed. Through comparative analysis of screening applications across ophthalmology, drug discovery, materials science, and semiconductor development, consistent patterns of limitations emerge alongside domain-specific challenges. Successful implementation requires robust validation frameworks, multi-method verification, and careful consideration of practical constraints. By understanding and addressing these limitations, researchers can more effectively leverage computational screening while critically evaluating its results within appropriate boundaries of confidence and applicability. Future advances will likely focus on improved data quality, more sophisticated algorithmic approaches, and better integration between computational prediction and experimental validation.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a method for scientific discovery especially used in drug discovery and relevant to the fields of biology, materials science, and chemistry [2]. Using robotics, data processing/control software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors, HTS allows a researcher to quickly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [2]. The validation workflow serves as a critical bridge between initial screening activities and confirmed hits, ensuring that results are both reliable and reproducible before committing significant resources to development. In the context of drug discovery, this process is particularly crucial as it helps mitigate the high failure rates observed in clinical trials, where approximately one-third of developed drugs fail at the first clinical stage, and half demonstrate toxicity in humans [26].

The validation framework in computational screening shares similarities with other scientific domains, such as the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) validation process which emphasizes determining "the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the intended uses of the model" [27]. For HTS, this translates to establishing confidence that screening results accurately predict biological activity and therapeutic potential. The process validation and screen reproducibility in HTS constitutes a major step in initial drug discovery efforts and involves the use of large quantities of biological reagents, hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds, and the utilization of expensive equipment [28]. These factors make it essential to evaluate potential issues related to reproducibility and quality before embarking on full HTS campaigns.

The Validation Workflow: From Screening to Confirmation

The validation workflow for high-throughput computational screening follows a structured pathway designed to progressively increase confidence in results while efficiently allocating resources. This systematic approach ensures that only the most promising compounds advance through increasingly rigorous evaluation stages.

Workflow Diagram

Figure 1: The multi-stage validation workflow progresses from initial screening through rigorous confirmation steps to identify validated hits.

Stage Descriptions

The validation workflow begins with assay development and optimization, where the biological or biochemical test system is designed and validated for robustness [26]. This foundational stage ensures the screening platform produces reliable, reproducible data before committing substantial resources to large-scale screening. Key considerations at this stage include pharmacological relevance, assay reproducibility across plates and screen days (potentially spanning several years), and assay quality as measured by metrics like the Z' factor, with values above 0.4 considered robust for screening [26].

Primary screening involves testing large compound libraries—often consisting of hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds—against the target of interest [2] [29]. This stage utilizes automation systems consisting of one or more robots that transport assay-microplates from station to station for sample and reagent addition, mixing, incubation, and finally readout or detection [2]. An HTS system can usually prepare, incubate, and analyze many plates simultaneously, further speeding the data-collection process [2].

Hit identification employs statistical methods to distinguish active compounds from non-active ones in the vast collection of screened samples [28]. The process of selecting hits, called hit selection, uses different statistical approaches depending on whether the screen includes replicates [2]. For screens without replicates, methods such as the z-score or strictly standardized mean difference (SSMD) are commonly applied, while screens with replicates can use t-statistics or SSMD that directly estimate variability for each compound [2].

Confirmatory screening retests the initial "hit" compounds in the same assay format to eliminate false positives resulting from random variation or compound interference [2]. This stage often involves "cherrypicking" liquid from the source wells that gave interesting results into new assay plates and re-running the experiment to collect further data on this narrowed set [2].

Dose-response studies determine the potency of confirmed hits by testing them across a range of concentrations to generate concentration-response curves and calculate half-maximal effective concentration (EC₅₀) values [2]. Quantitative HTS (qHTS) has emerged as a paradigm to pharmacologically profile large chemical libraries through the generation of full concentration-response relationships for each compound [2].

Counter-screening and selectivity assessment evaluates compounds against related targets or antitargets to assess specificity and identify compounds with potentially undesirable off-target effects [26]. Understanding that all assays have limitations, researchers create counter-assays that are essential for filtering out compounds that work in undesirable ways [26].

Final hit validation employs secondary assays with different readout technologies or more physiologically relevant models to further verify compound activity and biological relevance [26]. This often includes cell-based assays that provide deeper insight into the effect of small molecules in more complex biological systems [26].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Assay Design and Development

Assay development represents the foundational stage of the validation workflow, where researchers create test systems to assess the effects of drug candidates on desired biological processes [26]. Three primary assay categories support HTS validation:

Biochemical assays test the binding affinity or inhibitory activity of drug candidates against target enzymes or receptor molecules [26]. Common techniques include:

- Quenched fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology-based assays for screening inhibitors and monitoring proteolytic activity

- High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) techniques for assessing proteolytic action

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for analyzing inhibitory activity

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) techniques for studying compound-target interactions [26]

Cell-based assays evaluate drug efficacy in more complex biological contexts than biochemical assays, providing deeper insight into compound effects in systems more closely resembling human physiology [26]. These include:

- On-chip, cell-based microarray immunofluorescence assays for high-throughput target protein analysis

- Beta-lactamase protein fragment complementation assays for studying protein-protein interactions

- The ToxTracker assay for assessing compound toxicity

- Reporter gene assays for detecting primary signal pathway modulators

- Mammalian two-hybrid assays for studying mammalian protein interactions in cellular environments [26]

In silico assays represent computational approaches for screening compound libraries and evaluating affinity and efficacy before experimental testing [26]. These methods include:

- Ligand-based methods utilizing topological fingerprints and pharmacophore similarity

- Target-based methods such as docking and consensus scoring to estimate binding affinity

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) techniques predicting relationships between chemical structure and biological activity [26]

Statistical Validation Methods

Robust statistical analysis forms the backbone of effective hit identification and validation in HTS. The selection of appropriate statistical methods depends on the screening design and replication strategy.

Table 1: Statistical Methods for Hit Identification in HTS

| Screen Type | Statistical Method | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary screens without replicates | z-score [2] | Standardizes activity based on plate controls | Sensitive to outliers |

| Primary screens without replicates | SSMD (Strictly Standardized Mean Difference) [2] | Measures effect size relative to variability | Assumes compounds have same variability as negative reference |

| Primary screens without replicates | z*-score [2] | Robust version of z-score | Less sensitive to outliers |

| Screens with replicates | t-statistic [2] | Tests for significant differences from controls | Affected by both sample size and effect size |

| Screens with replicates | SSMD with replicates [2] | Directly estimates effect size for each compound | Directly assesses size of compound effects |

Quality control represents another critical component of HTS validation, with several metrics available to assess data quality:

- Signal-to-background ratio: Measures assay window between positive and negative controls

- Signal-to-noise ratio: Assesses signal detectability above background variation

- Z-factor: Comprehensive metric evaluating assay quality and robustness [2]

- Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD): Recently proposed for assessing data quality in HTS assays [2]

Advanced Validation Techniques

Recent technological advances have enhanced HTS validation capabilities:

Affinity selection mass spectrometry (ASMS)-based screening platforms, including self-assembled monolayer desorption ionization (SAMDI), enable discovery of small molecules engaging specific targets [29]. These platforms are amenable to a broad spectrum of targets, including proteins, complexes, and oligonucleotides such as RNA, and can serve as leading assays to initiate drug discovery programs [29].

CRISPR-based functional screening elucidates biological pathways involved in disease processes through gene editing for knock-out and knock-in experiments [29]. By selectively tagging proteins of interest, CRISPR advances understanding of target engagement and functional effects of drug treatments.

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) represents an advanced paradigm that generates full concentration-response relationships for each compound in a library [2]. This approach yields half maximal effective concentration (EC₅₀), maximal response, and Hill coefficient (nH) values for the entire library, enabling assessment of nascent structure-activity relationships (SAR) [2].

High-content screening utilizes automated imaging and multi-parametric analysis to capture complex phenotypic responses in cell-based assays [29]. When combined with 3D cell cultures, these approaches provide more physiologically relevant data, though challenges remain in developing high-throughput methods for analyzing cells within 3D environments [26].

Data Analysis and Visualization in Validation

Data Analysis Frameworks

The massive datasets generated by HTS campaigns require sophisticated analysis approaches. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have significantly enhanced data analysis capabilities in recent years [29]. New AI algorithms can analyze data from high-content screening systems, detecting complex patterns and trends that would otherwise be challenging for humans to identify [29]. AI/ML algorithms can identify patterns and predict the activity of small-molecule candidates, even when the data are noisy or incomplete [29].

Cloud technology has revolutionized data storage, sharing, and analysis, enabling real-time collaboration between research teams across multiple sites [29]. This infrastructure supports the application of machine learning models on large datasets and reduces data redundancy while improving collaboration [29]. The integration of AI into HTS processes can also improve assay optimization, with additional advantages including the ability to adapt to new data in real time compared to traditional HTS relying on pre-determined conditions [29].

Effective Data Visualization Principles

Effective data visualization is essential for interpreting HTS results and communicating findings. The following principles guide effective visual communication of screening data:

Diagram First: Before creating a visual, prioritize the information you want to share, envision it, and design it [30]. This principle emphasizes focusing on the information and message before engaging with software that might limit or bias visual tools [30].

Use the Right Software: Effective visuals typically require good command of one or more software packages specifically designed for creating complex, technical figures [30]. Researchers may need to learn new software or expand their knowledge of existing tools to create optimal visualizations [30].

Use an Effective Geometry and Show Data: Geometries—the shapes and features synonymous with figure types—should be carefully selected to match the data characteristics and communication goals [30]. The data-ink ratio (the ratio of ink used on data compared with overall ink used in a figure) should be maximized, with high data-ink ratios generally being most effective [30].

Table 2: Visualization Geometries for Different Data Types

| Data Category | Recommended Geometries | Applications in HTS Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Amounts/Comparisons | Bar plots, Cleveland dot plots, heatmaps [30] | Comparing potency values across compound series |

| Compositions/Proportions | Stacked bar plots, treemaps, mosaic plots [30] | Showing chemical series distribution in hit lists |

| Distributions | Box plots, violin plots, density plots [30] | Visualizing potency distributions across screens |

| Relationships | Scatterplots, line plots [30] | Correlation between different assay readouts |

Common visualization pitfalls to avoid in scientific publications include misused pie charts (identified as the most misused graphical representation) and size-related issues (the most critical visualization problem) [31]. The findings also showed statistically significant differences in the proportion of errors among color, shape, size, and spatial orientation [31].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of HTS validation workflows depends on specialized reagents and tools designed to support robust, reproducible screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter plates [2] | Testing vessels with wells for compound and reagent containment | Primary and confirmatory screening |

| Automated liquid-handling robots [29] | Precise liquid transfer with minimal volume requirements | Compound reformatting, assay assembly |

| Multimode plate readers [29] | Detection of multiple signal types (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance) | Assay readout and multiplexing |

| Target-directed compound libraries [29] | Curated chemical collections enriched for target classes | Primary screening with increased hit rates |

| Specialized assay reagents (e.g., FRET probes, enzyme substrates) [26] | Detection of specific biochemical activities | Biochemical assay implementation |

| Cell culture systems (2D and 3D) [26] | Physiologically relevant models for compound testing | Cell-based assay development |

| CRISPR-modified cell lines [29] | Genetically engineered systems for target validation | Functional screening and mechanism studies |

Recent advances in HTS reagents include the development of more stable assay components, specialized compound libraries such as Charles River's Lead-Like Compound Library (which includes compounds with lead-like properties and diversity while excluding problem chemotypes), and standardized protocols and data formats that simplify implementation and operation of HTE assays [29]. The trend toward miniaturization has also driven development of reagents optimized for low-volume formats, reducing consumption of valuable compounds and biological materials [29].

The validation workflow from screening to confirmation represents a critical pathway for transforming raw screening data into reliable, biologically relevant hits. This multi-stage process progressively increases confidence in results through rigorous experimental design, statistical analysis, and orthogonal verification. Recent advances in automation, miniaturization, and data analysis—particularly the integration of AI and ML—have significantly enhanced the efficiency and accuracy of this process [29].

The essential elements of successful validation include robust assay design, appropriate statistical methods for hit identification, thorough confirmation through dose-response and selectivity testing, and effective visualization and communication of results. As HTS technologies continue to evolve, with emerging approaches such as 3D cell culture models, advanced mass spectrometry techniques, and CRISPR-enabled functional genomics, validation workflows must similarly advance to ensure they effectively address new challenges and opportunities [29] [26].

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain, including the analysis of large HTE datasets that require substantial computational resources and difficulties in handling very small amounts of solids in miniaturized formats [29]. Addressing these challenges will require continued development of innovative technologies and methodologies, as well as collaborative approaches that leverage expertise across multiple disciplines. Through the consistent application of rigorous validation principles, researchers can maximize the value of HTS campaigns and improve the success rates of drug discovery programs.

Methodological Frameworks and Statistical Protocols for HTCS Validation

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a standard method in drug discovery that enables the rapid screening of large libraries of biological modulators and effectors against specific targets, accelerating the identification of potential therapeutic compounds [7]. The effectiveness of this process hinges on the robustness and reproducibility of the assays employed. A critical component of assay development is the establishment of a rigorous validation process to ensure that the data generated is reliable, predictive, and of high quality. This guide focuses on two fundamental analytical performance parameters in this validation process: plate uniformity and signal variability. We will objectively compare the validation data and methodologies from different HTS assays to provide a clear framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts: Plate Uniformity and Signal Variability

Before delving into experimental comparisons, it is essential to define the key metrics that underpin a robust HTS validation process.

- Plate Uniformity: This refers to the consistency of assay signal measurements across all wells on a microplate in the absence of any test compounds. It assesses the spatial homogeneity of the assay system. A high degree of plate uniformity indicates that the assay reagents are distributed evenly and that the equipment (e.g., dispensers, washers, readers) is functioning correctly, minimizing well-to-well and edge-based variations.

- Signal Variability: This measures the random fluctuations in the assay signal over multiple replicates. It is typically expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV), which is the standard deviation expressed as a percentage of the mean (CV% = [Standard Deviation / Mean] x 100). Low signal variability is crucial for distinguishing true positive or negative results from background noise.

- The Z'-Factor: This is a definitive, widely adopted metric that combines the dynamic range of an assay (the difference between the positive and negative control signals) with the data variation associated with these signals (their standard deviations) [32]. It is a robust indicator of assay quality and suitability for HTS. The formula is:

Z' = 1 - [3*(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|]whereσpandσnare the standard deviations of the positive and negative controls, andμpandμnare their respective means. An assay with a Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally considered excellent for HTS purposes [32].

Comparative Experimental Data and Validation Metrics

The following tables summarize quantitative validation data from two optimized antiradical activity assays and a bacterial whole-cell screening system, providing a direct comparison of their performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimized HTS Assay Conditions and Performance

| Validation Parameter | DPPH Reduction Assay [32] | ABTS Reduction Assay [32] | Bacterial HPD Inhibitor Assay [33] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay Principle | Electron transfer to reduce purple DPPH radical, monitored at 517 nm. | Electron transfer to reduce bluish-green ABTS radical, monitored at 750 nm. | Colorimetric detection of pyomelanin pigment produced by human HPD enzyme activity in E. coli. |

| Optimized Conditions | DPPH 280 μM in ethanol; 15 min reaction in the dark. | ABTS adjusted to 0.7 AU; 70% ethanol; 6 min reaction in the dark. | Human HPD expressed in E. coli C43 (DE3); induced with 1 mM IPTG; substrate: 0.75 mg/mL L-tyrosine. |

| Linearity Range | 7 to 140 μM (R² = 0.9987) | 1 to 70% (R² = 0.9991) | Dose-dependent pigment reduction with increasing inhibitor concentration. |

| Key Application | Suited for hydrophobic systems [32]. | Applicable to both hydrophilic and lipophilic systems [32]. | Identification of human-specific HPD inhibitors for metabolic disorders. |

Table 2: Comparison of Assay Validation and Robustness Metrics

| Performance Metric | DPPH Reduction Assay [32] | ABTS Reduction Assay [32] | Bacterial HPD Inhibitor Assay [33] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Variability (Precision) | Within acceptable limits for HTS. | Within acceptable limits for HTS. | Assessed via spatial uniformity; shown to be robust. |

| Plate Uniformity | Evaluated and confirmed. | Evaluated and confirmed. | Evaluated and confirmed; ideal for HTS. |

| Z'-Factor | > 0.89 | > 0.89 | Not explicitly stated, but described as "robust". |

| Throughput | High-throughput, microscale. | High-throughput, microscale. | High-throughput, cost-effective. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Assessment

To ensure the reliability of the data presented in the comparisons, the following standardized protocols for key experiments should be implemented.

Protocol for Plate Uniformity and Signal Variability Assessment

This protocol is fundamental for validating any HTS assay before screening compounds.

- Plate Selection: Use the appropriate microplate (e.g., 96-well, 384-well) for the assay.

- Solution Dispensing:

- Dispense the assay buffer or solvent into all wells of the microplate using a calibrated liquid handler to ensure consistent volume across the plate.

- For the negative control, add the solvent or buffer used for the test compounds to a designated set of wells (e.g., 32 wells).

- For the positive control, add a known inhibitor or activator at a concentration that gives a consistent signal to a separate set of wells (e.g., 32 wells).

- Assay Execution: Run the entire assay protocol as if it were a real screen, including all incubation steps, reagent additions, and final signal detection on a plate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean (

μ) and standard deviation (σ) for both the positive and negative control wells. - Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV%) for each control group:

CV% = (σ / μ) * 100. A CV of less than 10% is generally acceptable. - Calculate the Z'-Factor:

Z' = 1 - [3*(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|]. - Visually inspect the plate map for any spatial patterns (e.g., edge effects, column-wise trends) that would indicate poor plate uniformity.

- Calculate the mean (

Protocol for the Colorimetric Bacterial HPD Inhibitor Assay

This protocol exemplifies a robust whole-cell HTS system [33].

- Strain Preparation: Transform the expression vector containing the cDNA for wild-type human 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPD) into the E. coli C43 (DE3) strain. This specific strain is more resistant to the toxicity of human HPD expression compared to BL21 gold (DE3).

- Cell Culture and Induction: Inoculate Lysogeny Broth with Kanamycin (LBKANA) medium with a single colony. Grow the culture to the mid-log phase and induce human HPD expression with 1 mM Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Substrate Addition: Supplement the culture with 0.75 mg/mL L-tyrosine (TYR), which is converted by endogenous bacterial transaminases to 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (HPP), the substrate for human HPD.

- Assay Execution in Microplates: Dispense the bacterial culture into microplates. Add the test compounds (potential inhibitors) or controls.

- Incubation and Detection: Incubate the plates under physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours). During this time, active HPD converts HPP to homogentisate, which auto-oxidizes and polymerizes into a soluble brown, melanin-like pigment (pyomelanin).

- Signal Measurement: Quantify the pigment production using a plate reader by measuring the absorbance at an appropriate wavelength. The presence of an HPD inhibitor will reduce or prevent pigment production in a dose-dependent manner.

Visualizing the HTS Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in establishing a robust HTS validation process, incorporating the critical assessments of plate uniformity and signal variability.

Diagram 1: HTS assay validation and quality control workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of validated HTS assays relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The table below details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTS Validation | Example from Featured Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | High-density arrays of microreaction wells that form the foundation of HTS. Trends are towards miniaturization (384, 1536 wells) to reduce reagent costs and increase throughput [7]. | Polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plates [32]. |

| Control Compounds | Well-characterized substances used to define the maximum (positive) and minimum (negative) assay signals. Critical for calculating Z'-factor and assessing performance. | Quercetin and Trolox were used as positive controls for the DPPH and ABTS assays, respectively [32]. Nitisinone is a known HPD inhibitor [33]. |

| Chemical Standards & Radicals | The core reagents that generate the detectable signal in an assay. Their purity and stability are paramount. | DPPH and ABTS radicals [32]. |

| Buffer & Solvent Systems | The medium in which the assay occurs. It must maintain pH and ionic strength, and ensure solubility of all components without interfering with the signal. | Ethanol was the optimized solvent for both DPPH and ABTS methods [32]. Lysogeny Broth (LB) for bacterial culture [33]. |

| Expression Systems | Engineered cells used to produce the target protein of interest for cell-based or biochemical assays. | E. coli C43 (DE3) strain for robust expression of human HPD [33]. |

| Induction Agents | Chemicals used to trigger the expression of a recombinant protein in an engineered cell line. | Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalhydrazyl (IPTG) for inducing human HPD expression in E. coli [33]. |

The objective comparison of validation data from diverse HTS assays underscores a consistent theme: rigorous assessment of plate uniformity and signal variability is non-negotiable for generating reliable screening data. As demonstrated, successful assays, whether biochemical like DPPH and ABTS or cell-based like the bacterial HPD system, share common traits. They are optimized through systematic experimentation and are characterized by high Z'-factors (>0.5), low signal variability (CV < 10%), and excellent plate uniformity. By adhering to the detailed experimental protocols and utilizing the essential research reagents outlined in this guide, scientists can establish a robust validation process. This ensures that their high-throughput computational screening results are grounded in high-quality, reproducible experimental data, thereby de-risking the drug discovery pipeline and accelerating the development of new therapeutics.

High-throughput screening (HTS) represents a fundamental approach in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of chemical compounds against biological targets. The reliability of these campaigns hinges on robust statistical metrics that quantify assay performance and data quality. Within this framework, the Z'-factor and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) have emerged as cornerstone parameters for evaluating assay suitability and instrument sensitivity. These metrics provide objective criteria for assessing whether an assay can reliably distinguish true biological signals from background variability, a critical consideration in the validation of high-throughput computational screening results [34] [35]. The strategic application of Z'-factor and S/N allows researchers to optimize assays before committing substantial resources to full-scale screening, thereby reducing false positives and improving the probability of identifying genuine hits [36].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two essential metrics, detailing their theoretical foundations, calculation methodologies, interpretation guidelines, and practical applications within HTS workflows. Understanding their complementary strengths and limitations enables researchers to make informed decisions about assay validation and quality control throughout the drug discovery pipeline.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Z'-factor

The Z'-factor is a dimensionless statistical parameter specifically developed for quality assessment in high-throughput screening assays. Proposed by Zhang et al. in 1999, it serves as a quantitative measure of the separation band between positive and negative control populations, taking into account both the dynamic range of the assay signal and the data variation associated with these measurements [36] [37]. The Z'-factor is defined mathematically using four parameters: the means (μ) and standard deviations (σ) of both positive (p) and negative (n) control groups:

Formula: Z' = 1 - [3(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|] [36] [34] [38]

This formulation effectively captures the relationship between the separation of the two control means (the signal dynamic range) and the sum of their variabilities (the noise). The constant factor of 3 is derived from the properties of the normal distribution, where approximately 99.7% of values occur within three standard deviations of the mean [36]. The Z'-factor characterizes the inherent quality of the assay itself, independent of test compounds, making it particularly valuable for assay optimization and validation prior to initiating large-scale screening efforts [36] [34].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N)

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio is a fundamental metric used across multiple scientific disciplines to quantify how effectively a measurable signal can be distinguished from background noise. In the context of HTS, it compares the magnitude of the assay signal to the level of background variation [34]. The S/N ratio is calculated as follows:

Formula: S/N = (μp - μn) / σn [34]

Unlike the Z'-factor, which incorporates variability from both positive and negative controls, the standard S/N ratio primarily considers variation in the background (negative controls). This makes it particularly useful for assessing the confidence with which one can quantify a signal, especially when that signal is near the background level [34]. The metric is widely applied for evaluating instrument sensitivity and detection capabilities, as it directly reflects how well a signal rises above the inherent noise floor of the measurement system.

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

Core Characteristics and Computational Formulae

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, formulae, and components of the Z'-factor and Signal-to-Noise Ratio:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Z'-factor and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Characteristic | Z'-factor | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | Z' = 1 - [3(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|] [36] [38] | S/N = (μp - μn) / σn [34] |

| Parameters Considered | Mean & variation of both positive and negative controls [34] | Mean signal, mean background, & background variation [34] |

| Primary Application | Assessing suitability of an HTS assay for hit identification [36] [37] | Evaluating instrument sensitivity and detection confidence [34] |

| Theoretical Range | -∞ to 1 [36] | -∞ to ∞ |

| Key Strength | Comprehensive assay quality assessment | Simplicity and focus on background interference |

Interpretation Guidelines and Quality Assessment

The interpretation of these metrics follows established guidelines that help researchers qualify their assays and instruments:

Table 2: Quality Assessment Guidelines for Z'-factor and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Metric Value | Interpretation | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Z' > 0.5 | Excellent assay [36] [38] | Ideal for HTS; high probability of successful hit identification |

| 0 < Z' ≤ 0.5 | Marginal to good assay [36] [38] | May be acceptable for complex assays; consider optimization |

| Z' ≤ 0 | Poor assay; substantial overlap between controls [36] [34] | Unacceptable for HTS; requires significant re-optimization |

| High S/N | Signal is clearly distinguishable from noise [34] | Confident signal detection and quantification |

| Low S/N | Signal is obscured by background variation [34] | Difficult to reliably detect or quantify signals |

For the Signal-to-Noise Ratio, unlike the Z'-factor, there are no universally defined categorical thresholds (e.g., excellent, good, poor). Interpretation is often context-dependent, with higher values always indicating better distinction between signal and background noise.

Relative Strengths and Limitations

Each metric offers distinct advantages and suffers from specific limitations that influence their appropriate application:

Z'-factor Advantages: The principal strength of the Z'-factor lies in its comprehensive consideration of all four key parameters: mean signal, signal variation, mean background, and background variation [34]. This holistic approach makes it uniquely suited for evaluating the overall quality of an HTS assay and its ability to reliably distinguish between positive and negative outcomes. Furthermore, its standardized interpretation scale (with a Z' > 0.5 representing an excellent assay) facilitates consistent communication and decision-making across different laboratories and projects [36] [38].

Z'-factor Limitations: The Z'-factor can be sensitive to outliers due to its use of means and standard deviations in the calculation [36]. In cases of strongly non-normal data distributions, its interpretation can be misleading. To address this, robust variants using median and median absolute deviation (MAD) have been proposed [36]. Additionally, the Z'-factor is primarily designed for single-concentration screening and may be less informative for dose-response experiments.

S/N Advantages: The Signal-to-Noise Ratio provides an intuitive and straightforward measure of how well a signal can be detected above the background, making it exceptionally valuable for evaluating instrument performance and detection limits [34]. Its calculation is simple, and it directly answers the fundamental question of whether a signal is detectable.

S/N Limitations: A significant limitation of the standard S/N ratio is its failure to account for variation in the signal (positive control) itself [34]. This can be problematic, as two assays with identical S/N ratios could have vastly different signal variabilities, leading to different probabilities of successful hit identification. It therefore provides a less complete picture of assay quality compared to the Z'-factor.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for Metric Calculation

The reliable calculation of both Z'-factor and S/N requires a structured experimental approach. The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow from experimental design to final metric calculation and interpretation.

Protocol for Assay Validation Using Z'-factor and S/N

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the quality and robustness of a high-throughput screening assay prior to full-scale implementation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Positive Control: A compound or treatment known to produce a strong positive response (e.g., a potent inhibitor for an inhibition assay).

- Negative Control: A compound or treatment known to produce a minimal or background response (e.g., buffer or vehicle control).

- Assay Plates: Standard microplates (e.g., 96-, 384-, or 1536-well) compatible with the detection system.

- Liquid Handling System: Automated pipetting station for precise reagent dispensing.

- Detection Instrument: Plate reader or imager appropriate for the assay technology (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence).

Procedure:

- Plate Design: Distribute positive and negative controls across the assay plate(s). A minimum of 3 replicates per control is essential, but 8-16 replicates are recommended for robust statistics [39]. Controls should be randomized to account for potential spatial biases like edge effects or dispensing gradients.

- Assay Execution: Run the assay protocol under the same conditions planned for the full HTS campaign. This includes identical reagent concentrations, incubation times, temperatures, and detection settings.

- Data Collection: Record the raw signal measurements for all control wells.

- Quality Inspection: Generate a plate heatmap to visually identify any spatial artifacts (e.g., trends, evaporation effects). Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV) for control replicates; a CV < 10% is typically targeted for biochemical assays [38].

- Metric Calculation:

- Calculate the mean (μp, μn) and standard deviation (σp, σn) for the positive and negative control populations, respectively.

- Compute the Z'-factor: 1 - [3(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|].

- Compute the S/N ratio: (μp - μn) / σn.

- Interpretation: Use the guidelines in Table 2 to assess assay quality. An assay with Z' ≥ 0.5 is considered excellent for HTS. Simultaneously, a high S/N ratio confirms that the instrument can confidently detect the signal above background.

Decision Framework for Metric Selection

The choice between using Z'-factor, S/N, or both depends on the specific question being asked in the experiment. The following decision workflow guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate metric.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of the aforementioned protocols relies on a suite of key reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their functions within the HTS validation workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Assay Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Control Compound | Provides a known strong signal; defines the upper assay dynamic range and is crucial for calculating both Z'-factor and S/N. | A well-characterized, potent agonist/antagonist for a receptor assay; a strong inhibitor for an enzyme assay. |

| Negative Control (Vehicle) | Defines the baseline or background signal; essential for quantifying the assay window and noise level. | Buffer-only wells, cells treated with DMSO vehicle, or a non-targeting siRNA in a functional genomic screen. |

| Validated Assay Kits | Provide optimized, off-the-shelf reagent formulations that reduce development time and improve inter-lab reproducibility. | Commercially available fluorescence polarization (FP) or time-resolved fluorescence (TRFRET) kits for specific target classes. |

| Quality Control Plates | Pre-configured plates containing control compounds used for routine instrument and assay performance qualification. | Plates with pre-dispensed controls in specific layouts for automated calibration of liquid handlers and readers. |

| Normalization Reagents | Used in data processing algorithms (e.g., B-score) to correct for systematic spatial biases across assay plates. | Controls distributed across rows and columns to enable median-polish normalization and remove plate patterns. |