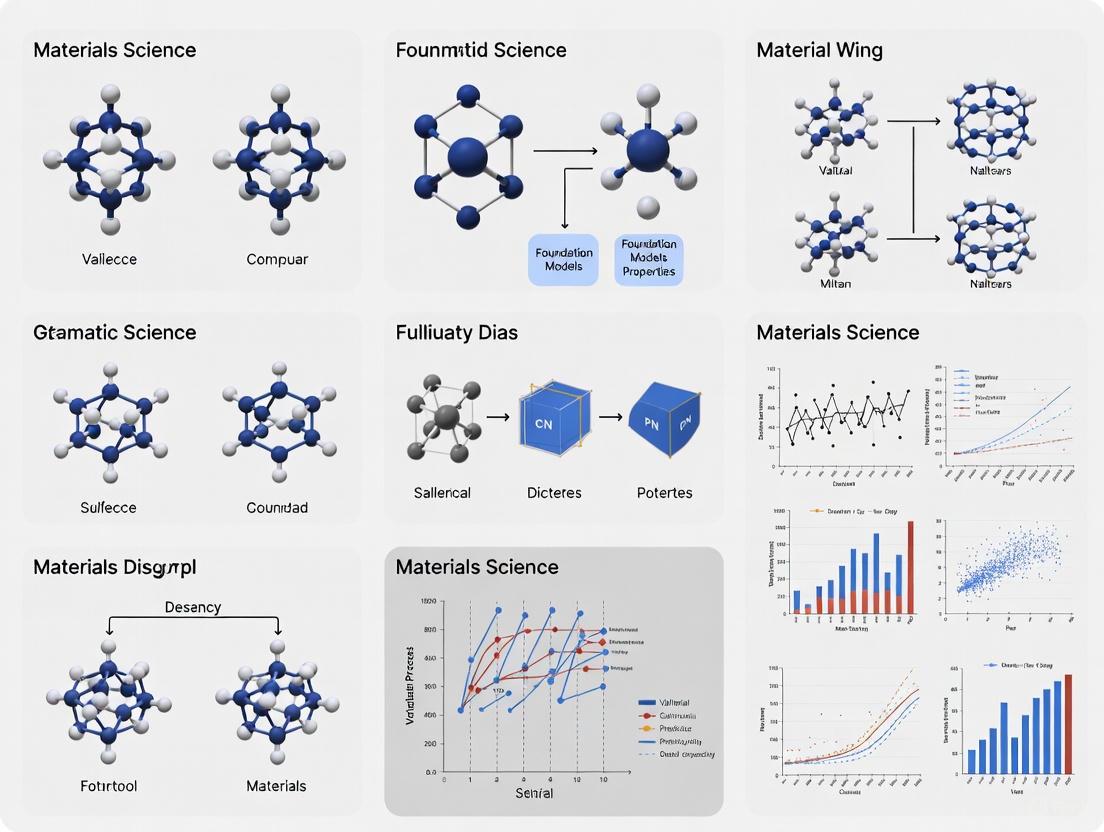

Validating Foundation Models for Materials Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientific Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating foundation models in materials property prediction, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Foundation Models for Materials Property Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating foundation models in materials property prediction, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of scientific foundation models and their distinctions from traditional deep learning approaches. The content covers diverse methodological architectures, practical optimization strategies for enhanced efficiency, and robust validation protocols incorporating domain-specific benchmarks. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this guide aims to establish trustworthy validation standards that accelerate reliable materials discovery and development workflows.

Understanding Foundation Models: Core Concepts and Scientific Applications

The advent of foundation models represents a fundamental transformation in how artificial intelligence is applied to scientific discovery, particularly in domains like materials science and drug development. Unlike traditional deep learning models that are typically trained on limited, task-specific datasets, scientific foundation models are large-scale AI systems pre-trained on extensive, diverse scientific data using self-supervised methods, then adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks through fine-tuning [1]. This paradigm shift decouples the data-hungry representation learning phase from target-specific applications, enabling researchers to build sophisticated predictive capabilities with significantly less labeled data than traditional approaches required [1].

The critical distinction between general-purpose foundation models (like ChatGPT) and their scientific counterparts lies in their specialized architecture, training data, and capabilities. Scientific foundation models incorporate domain-specific knowledge, must adhere to physical constraints and laws, and are designed to handle the complex, multimodal nature of scientific information [2] [3]. For materials property prediction specifically, these models are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in accelerating property prediction, guiding materials discovery, and providing insights that would be computationally prohibitive using traditional simulation-based approaches [1] [4].

Defining Characteristics of Scientific Foundation Models

Scientific foundation models exhibit several distinguishing characteristics that set them apart from both traditional deep learning models and general-purpose foundation models:

Cross-Modal Alignment: They integrate multiple representations of scientific data (text, molecular structures, spectral information, property data) into a unified latent space, enabling knowledge transfer across different modalities and data types [3] [5]. The MultiMat framework, for instance, aligns crystal structures, density of states, charge density, and textual descriptions in a shared representation space [5].

Physical Constraint Satisfaction: Unlike general-purpose models, scientific foundation models must obey fundamental physical laws and constraints, such as conservation of mass, energy, and momentum, which is critical for generating physically plausible predictions [2].

Uncertainty Quantification: These models incorporate probabilistic forecasting and uncertainty quantification essential for scientific decision-making in safety-critical domains like drug development and materials design [2].

Multiscale Modeling Capability: They can integrate information across different spatial and temporal scales, from atomic-level interactions to macroscopic material properties, addressing a fundamental challenge in computational materials science [6].

Comparative Analysis of Leading Scientific Foundation Models

Performance Benchmarking Across Model Architectures

Rigorous evaluation against standardized benchmarks reveals significant performance differences across model architectures and training approaches. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics for prominent foundation models in materials science:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Scientific Foundation Models for Materials Property Prediction

| Model Name | Architecture/Approach | Training Data | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MultiMat [5] | Multimodal contrastive learning (CLIP-inspired) | Materials Project database | State-of-the-art on challenging property prediction tasks; enables discovery via latent-space similarity | Crystal property prediction, stable materials screening |

| IBM FM4M Family [7] | Multi-view Mixture of Experts (MoE) | 1B+ molecules (PubChem, ZINC-22) | Outperforms single-modality models on MoleculeNet benchmarks; optimal expert activation for different tasks | Molecular property prediction, sustainable materials discovery |

| Chronos [2] | Time series foundation model (T5-based) | Synthetic time series data + Gaussian processes | Superior performance on chaotic/dynamical systems compared to classical methods | Probabilistic forecasting of scientific time series data |

| EquiformerV2 [8] | Universal machine learning potential | OMat24 dataset (2,429 materials) | Strongest performance for phonon properties and lattice thermal conductivity prediction | Atomic force prediction, thermal transport properties |

| Battery Foundation Models [4] | Transformer-based molecular representations | Billions of molecular compounds | Unifies multiple property predictions; outperforms single-property models developed over years | Battery electrolyte and electrode design, conductivity prediction |

Specialized Capabilities Comparison

Beyond general performance metrics, scientific foundation models exhibit specialized capabilities tailored to different research needs:

Table 2: Specialized Capabilities of Scientific Foundation Models

| Model/Approach | Multimodal Fusion | Interpretability Features | Physical Constraint Handling | Generalization Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MultiMat [5] | Crystal structure, DOS, charge density, text | Emergent features correlating with material properties | Implicit through training data | Cross-property transfer learning |

| IBM Multi-view MoE [7] | SMILES, SELFIES, molecular graphs | Expert activation patterns reveal task-modality relationships | Limited for 3D molecular constraints | Strong cross-task generalization |

| Chronos [2] | Univariate and spatiotemporal data | Probabilistic forecasting with uncertainty quantification | Explicit constraint enforcement via ProbConserv | Robust to chaotic system dynamics |

| EquiformerV2 [8] | Atomic coordinates, forces | Force constant derivation interpretable | Physically constrained force fields | Broad chemical space coverage |

| Battery Models [4] | SMILES, SMIRK representations | Interactive chatbot for exploration | Validation against experimental data | Large chemical space exploration (10^60 molecules) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multimodal Pre-training and Alignment

The MultiMat framework employs a sophisticated multimodal pre-training approach inspired by Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) but extended to handle more than two modalities [5]. The experimental workflow involves:

Modality Encoding: Separate neural network encoders process each modality - PotNet Graph Neural Network for crystal structures, Transformer architectures for density of states, 3D-CNN for charge density, and MatBERT for textual descriptions [5].

Latent Space Alignment: A contrastive learning objective aligns the embeddings from different modalities in a shared latent space, encouraging representations of the same material across different modalities to be similar while pushing apart representations of different materials [5].

Transfer Learning: The pre-trained encoders, particularly the crystal structure encoder, are fine-tuned on specific property prediction tasks with limited labeled data, demonstrating superior performance compared to models trained from scratch [5].

Multimodal Foundation Model Architecture

Multi-view Mixture of Experts Implementation

IBM's foundation model family employs a sophisticated Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture that dynamically combines multiple molecular representations [7]:

Expert Specialization: Independent foundation models are pre-trained on different molecular representations - SMILES-TED (91 million validated SMILES strings), SELFIES-TED (1 billion SELFIES), and MHG-GED (1.4 million molecular graphs) [7].

Router Training: A gating network learns to assign appropriate weights to each expert based on the specific task, with the model automatically learning which representations are most relevant for different types of predictions [7].

Fusion Mechanism: The MoE architecture combines embeddings from the three data modalities, with experiments revealing that the router preferentially activates different experts depending on task requirements - sometimes favoring SMILES and SELFIES-based models, while in other cases utilizing all three modalities equally [7].

Evaluation Methodologies and Benchmarking

Standardized evaluation protocols are critical for comparing foundation models across different research groups:

Materials Project Benchmarking: MultiMat was evaluated on the Materials Project database using standardized train/validation/test splits, with performance measured on formation energy and bandgap prediction tasks [5].

MoleculeNet Comprehensive Evaluation: IBM's models were tested on the MoleculeNet benchmark, which includes both classification tasks (e.g., toxicity prediction) and regression tasks (e.g., solubility prediction) across diverse molecular datasets [7].

Phonon Property Benchmarking: EquiformerV2 and other universal machine learning potentials were systematically evaluated on 2,429 crystalline materials from the Open Quantum Materials Database, with predictions compared against density functional theory calculations and experimental data for lattice thermal conductivity [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The development and application of scientific foundation models rely on sophisticated computational infrastructure and datasets:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Foundation Model Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Key Functionality | Access/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project [5], PubChem [1], ZINC [1], ChEMBL [1] | Provide structured materials data for training | Public access with some licensing restrictions |

| Supercomputing Resources | ALCF Polaris & Aurora [4], DOE Leadership Computing Facilities | Enable training on billions of molecules with thousands of GPUs | Competitive allocation through INCITE program |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES [1], SELFIES [1], Molecular Graphs [7], SMIRK [4] | Text-based and structural representations of molecules | Open standards and formats |

| Benchmarking Suites | MoleculeNet [7], Open Quantum Materials Database [8] | Standardized evaluation metrics and datasets | Publicly available for research use |

| Pre-trained Models | IBM FM4M family [7], MultiMat [5], Battery foundation models [4] | Starting point for transfer learning and fine-tuning | Open-source availability on GitHub/Hugging Face |

The comprehensive benchmarking and experimental validation of scientific foundation models demonstrate their significant advantages over traditional deep learning approaches for materials property prediction. The multi-modal alignment strategies employed by MultiMat, the adaptive expert selection in IBM's MoE architecture, and the physical constraint incorporation in models like Chronos collectively represent a paradigm shift in how AI is applied to scientific discovery [5] [7] [2].

These models consistently outperform single-task, specialized models while providing enhanced interpretability and generalization capabilities. However, challenges remain in areas including full 3D structural representation, seamless multimodal fusion, and ensuring physical plausibility across all predictions [1] [2]. The rapid adoption of these models - with IBM's foundation models being downloaded over 100,000 times in just a few months - indicates their transformative potential for accelerating materials discovery and property prediction across diverse scientific domains [7].

As the field evolves, future developments will likely focus on scalable pre-training methods, improved continual learning capabilities, enhanced uncertainty quantification, and more sophisticated physics integration, further bridging the gap between AI capabilities and the fundamental requirements of scientific discovery [6] [3].

The application of foundation models in materials property prediction represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science. These models, trained on broad data and adaptable to diverse downstream tasks, are accelerating the discovery of novel materials with desired properties [1]. The architectural choice between encoder-only, decoder-only, and multimodal frameworks significantly influences model performance, capability, and applicability within materials science research. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these architectural paradigms, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental methodologies, and suitability for various materials discovery tasks.

Each architecture brings distinct advantages: encoder-only models excel at property prediction from structured representations, decoder-only models generate novel molecular structures, and multimodal frameworks integrate diverse data types to create more comprehensive material representations [1]. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for researchers selecting appropriate architectures for specific materials informatics challenges.

Core Architectural Differences

The three architectural paradigms employ fundamentally different mechanisms for processing information and generating outputs, each with distinct implications for materials science applications.

Encoder-Only Models utilize bidirectional attention mechanisms, allowing each token in the input sequence to attend to all other tokens. This architecture generates comprehensive contextual representations of input data, making it ideal for understanding tasks. In materials science, encoder-only models based on the BERT architecture have been widely adopted for property prediction from molecular representations like SMILES or SELFIES [1] [9]. These models excel at capturing complex relationships within molecular structures but are limited in generative capabilities.

Decoder-Only Models employ unidirectional attention, where each token can only attend to previous tokens in the sequence. This autoregressive approach is naturally suited for sequential generation tasks. In materials discovery, decoder-only models can generate novel molecular structures token-by-token, facilitating inverse design [1] [9]. However, their unidirectional nature may limit their ability to incorporate global context during representation learning compared to bidirectional encoders.

Encoder-Decoder Models combine both components, using a bidirectional encoder to process input and a unidirectional decoder to generate output. This architecture effectively separates understanding from generation, potentially offering benefits for tasks requiring both comprehensive input analysis and structured output generation [10].

Architectural paradigms for materials foundation models. Encoder-only models use bidirectional attention for understanding, decoder-only models use unidirectional attention for generation, and encoder-decoder models combine both approaches.

Attention Mechanisms and Rank Considerations

The attention mechanisms in these architectures fundamentally differ in their information flow and mathematical properties. Encoder-only models utilize bidirectional self-attention, allowing each token to attend to all other tokens in the sequence. This creates a comprehensive context but can lead to a low-rank bottleneck when the head dimension is smaller than the sequence length, potentially reducing expressive power [9].

Decoder-only models employ unidirectional self-attention, where each token only attends to previous tokens. This preserves higher rank in attention weight matrices, maintaining unique information for each token and enhancing generative capabilities [9]. The unidirectional approach is particularly suited for sequential generation tasks in molecular design.

Encoder-decoder architectures implement a hybrid approach, with bidirectional attention in the encoder for input understanding and unidirectional attention in the decoder for output generation. This separation can improve efficiency for sequence-to-sequence tasks in materials informatics [10].

Performance Comparison in Materials Science Tasks

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of architectural paradigms on materials property prediction tasks

| Architecture | Model Examples | Property Prediction Accuracy | Generative Capability | Data Efficiency | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | DeBERTa v3 Large, MatBERT | High (State-of-the-art on many benchmarks) [11] [5] | Limited | Moderate to High | Lower than decoder counterparts [12] |

| Decoder-Only | GPT-4, Mistral-7B, LLaMA | Moderate (Improves with scale) [11] [9] | High (Novel material generation) [1] | Lower (Requires substantial scale) | High (Especially for large models) |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5, UL2, RedLLM | Moderate to High (After instruction tuning) [10] | Moderate | Varies | Moderate (Efficient inference) [10] |

Table 2: Specialized capabilities for materials science applications

| Architecture | Strength Areas | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | Property prediction from structure [1], Classification tasks, Transfer learning with limited data | Limited generative capability, Primarily works with 2D representations [1] | High-throughput screening, Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) |

| Decoder-Only | Novel material generation [1], Inverse design, Textual descriptions of materials | Requires careful prompting for discriminative tasks, Computationally intensive | Generative design of materials, Composition generation, Conditioned synthesis planning |

| Encoder-Decoder | Sequence-to-sequence tasks, Structured prediction, Instruction following [10] | Less parallelization capability [9] | Multi-step reasoning, Text-to-material generation, Complex workflow formulation |

Scaling Properties and Efficiency Considerations

The scaling behavior of these architectures significantly impacts their practical deployment in materials research. Recent comprehensive studies comparing encoder-decoder LLMs (RedLLM) with decoder-only LLMs (DecLLM) across scales from ~150M to ~8B parameters reveal important trade-offs [10]:

- Decoder-only models generally dominate the compute-optimal frontier during pretraining, making them efficient for large-scale training.

- Encoder-decoder models demonstrate comparable scaling exponents and context length extrapolation capabilities despite being less compute-optimal during pretraining.

- Inference efficiency favors encoder-decoder architectures after instruction tuning, with RedLLM achieving comparable or better performance on various downstream tasks while enjoying substantially better inference efficiency [10].

For materials science applications where inference efficiency is crucial for high-throughput screening, encoder-decoder models may provide the optimal balance between performance and computational requirements.

Multimodal Frameworks for Materials Science

The MultiMat Framework

Multimodal foundation models represent a significant advancement for materials science by integrating diverse data types into a unified representation. The Multimodal Learning for Materials (MultiMat) framework enables self-supervised multi-modality training by aligning latent spaces of different material representations [5] [13]. This approach addresses a key limitation of single-modality models, which fail to leverage the rich diversity of material information available.

MultiMat incorporates four key modalities for each material:

- Crystal structure (C): Atomic coordinates and lattice vectors

- Density of states (ρ(E)): Electronic structure information

- Charge density (nₑ(𝐫)): Electron distribution

- Textual descriptions (T): Machine-generated crystal descriptions [5]

The framework employs specialized encoders for each modality, with a PotNet graph neural network for crystal structures, transformer-based encoders for density of states, 3D-CNN for charge density, and a frozen MatBERT model for textual descriptions [5]. These encoders are trained to project all modalities into a shared latent space where representations of the same material are aligned.

MultiMat framework for multimodal materials representation. Diverse material modalities are encoded into a shared latent space using specialized encoders, enabling various downstream tasks.

Performance of Multimodal Approaches

Multimodal frameworks demonstrate significant advantages over single-modality approaches across multiple dimensions:

- State-of-the-art property prediction: MultiMat achieves superior performance on challenging material property prediction tasks by leveraging complementary information across modalities [5] [13].

- Novel material discovery: The aligned latent space enables screening for stable materials with desired properties via similarity search, facilitating efficient materials discovery [13].

- Interpretable emergent features: MultiMat encodes interpretable features that correlate with material properties, potentially providing novel scientific insights [5].

- Improved generalization: By learning from multiple complementary representations, multimodal models develop more robust representations that generalize better to unseen materials [14].

Experimental results demonstrate that multimodal approaches consistently enhance predictive accuracy compared to single-modality models, particularly when integrating text and image data [14]. However, certain complex properties like band gaps remain challenging to predict accurately even with multimodal integration.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Methodologies for Architectural Comparisons

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for valid comparisons between architectural paradigms. Key methodological considerations include:

Dataset Selection and Preparation

- Using curated materials science benchmarks like Materials Project [5], Alexandria [14], or specialized STEM datasets [11]

- Ensuring balanced representation across material classes and properties

- Proper train/validation/test splits to avoid data leakage

- Careful handling of multimodal data alignment and representation

Evaluation Metrics

- Property prediction accuracy (MAE, RMSE, classification metrics)

- Generative quality (validity, novelty, uniqueness for generated structures)

- Computational efficiency (training time, inference latency, memory usage)

- Data efficiency (performance with limited training data)

Training Protocols

- Consistent pretraining and fine-tuning procedures across architectures

- Appropriate hyperparameter optimization for each model type

- Fair computational budget comparisons (fixed FLOPs or training time)

- Careful prompt engineering for decoder-only models in discriminative tasks [9]

Case Study: STEM MCQ Evaluation Protocol

A comparative analysis of encoder-only and decoder-only models for challenging LLM-generated STEM multiple-choice questions provides insights into architectural trade-offs [11]. The experimental protocol included:

- Dataset Generation: Various LLMs (Vicuna-13B, Bard, GPT-3.5) generated MCQs on STEM topics curated from Wikipedia

- Model Evaluation: Open-source models (Llama 2-7B, Mistral-7B) and encoder model (DeBERTa v3 Large) evaluated on inference with context

- Training Variations: Models fine-tuned with and without context

- Benchmarking: Results compared against closed-source models (Gemini, GPT-4) on inference with context

Key findings demonstrated that DeBERTa v3 Large and Mistral-7B Instruct outperformed Llama 2-7B, highlighting the potential of appropriately contextualized models with fewer parameters [11]. This approach showcases how challenging tasks generated by LLMs can serve as effective self-evaluation mechanisms for other models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key resources for developing and evaluating foundation models in materials science

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project [5], PubChem [1], Alexandria [14] | Structured material properties and crystal structures | Publicly available, varying licensing |

| Extraction Tools | Named Entity Recognition (NER) [1], Vision Transformers [1], Plot2Spectra [1] | Extract materials data from scientific literature and patents | Specialized algorithms for different modalities |

| Representation Methods | SMILES [1], SELFIES [1], Crystal Graphs [5] | Standardized representations of molecular and crystal structures | Impact model performance and interpretability |

| Multimodal Frameworks | MultiMat [5] [13], CLIP-based approaches [5] | Align multiple material representations in shared latent space | Enable cross-modal reasoning and retrieval |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | Materials Property Prediction Tasks [5], STEM MCQs [11] | Standardized performance assessment | Ensure comparable results across studies |

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The field of foundation models for materials science is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions emerging:

Extrapolative Prediction Capabilities Traditional machine learning models generally excel at interpolative predictions within the distribution of training data but struggle with extrapolation to unexplored domains. Recent developments in meta-learning algorithms like E2T (extrapolative episodic training) address this limitation by training models on artificially generated extrapolative tasks [15]. This approach demonstrates improved predictive accuracy for materials with elemental and structural features not present in training data, potentially enhancing exploration of novel material spaces.

Architectural Hybridization Future architectures may increasingly blend components from different paradigms, such as incorporating bidirectional attention mechanisms into primarily decoder-only models to enhance their understanding capabilities while preserving strong generative performance [10]. The introduction of rotary positional embedding with continuous positions in encoder-decoder models represents one such innovation [10].

Modality Expansion Current multimodal frameworks primarily integrate crystal structure, density of states, charge density, and textual descriptions. Future frameworks may incorporate additional modalities such as spectroscopic data, synthesis parameters, mechanical properties, and experimental characterization results to create even more comprehensive material representations [14].

Efficiency Optimization As model complexity increases, techniques for improving computational efficiency become increasingly important. Approaches such as parameter-efficient fine-tuning, model distillation, and specialized hardware acceleration will be essential for practical deployment of foundation models in materials research workflows [12].

The architectural landscape for materials foundation models continues to evolve, with each paradigm offering distinct advantages for specific applications. Encoder-only models provide strong performance for property prediction, decoder-only models excel at generative tasks, and multimodal frameworks enable comprehensive material representation. Understanding these trade-offs allows researchers to select appropriate architectures for their specific materials discovery challenges, ultimately accelerating the development of novel materials with tailored properties.

Critical Data Requirements and Challenges in Materials Science

The adoption of data-driven methodologies is heralded as a new paradigm in materials science, representing a fourth scientific paradigm following historically experimental, theoretical, and computationally propelled discoveries [16]. This field, often termed materials informatics, systematically extracts knowledge from materials datasets that are too large or complex for traditional human reasoning, with the ultimate intent to discover new or improved materials or materials phenomena [16] [17]. The vision of a "Materials Ultimate Search Engine" (MUSE) drives the community forward, yet the path is fraught with challenges related to data quality, distribution, and applicability [16]. This guide objectively compares the current landscape of data requirements and methodological challenges within the broader thesis of validating foundation models for materials property prediction, providing researchers with a framework for critical evaluation.

Critical Data Challenges in Materials Informatics

Dataset Redundancy and Performance Overestimation

A fundamental challenge skewing the evaluation of materials property prediction models is the widespread redundancy in benchmark datasets. Materials databases such as the Materials Project and Open Quantum Materials Database are characterized by many highly similar materials, a legacy of the historical "tinkering" approach to material design [18]. When machine learning (ML) models are trained and tested using random splits on these redundant datasets, the performance is significantly overestimated because the test sets contain materials highly similar to those in the training sets. This leads to impressive but misleading interpolation performance that does not translate to real-world discovery tasks, which often require extrapolation to truly novel materials [18].

The MD-HIT algorithm was developed specifically to address this redundancy, functioning similarly to CD-HIT in bioinformatics. It controls dataset redundancy by ensuring no pair of samples exceeds a specified structural or compositional similarity threshold, creating more realistic evaluation conditions [18]. Studies demonstrate that when models are evaluated on MD-HIT-processed datasets, prediction performances tend to be relatively lower compared to models evaluated on high-redundancy data, but these scores better reflect the models' true predictive capability for out-of-distribution samples [18].

The Out-of-Distribution Generalization Problem

The core objective of materials discovery is identifying extremes with property values that fall outside known distributions. However, most ML models face significant challenges in extrapolating to out-of-distribution (OOD) property values, which is precisely what is needed for discovering high-performance materials [19]. This OOD problem manifests in two key dimensions:

- Range Extrapolation: Generalizing to property values beyond those seen in training data [19]

- Domain Extrapolation: Generalizing to unseen classes of materials, structures, and chemical spaces [19]

Traditional virtual screening approaches often fail when target property values lie outside the training data distribution. For material discovery, the critical challenge lies in enhancing extrapolative capabilities to improve the screening of large candidate spaces, thereby boosting precision in identifying promising compounds with exceptional properties [19].

Table 1: Comparative Performance on OOD Property Prediction Tasks

| Model | MAE on Bulk Modulus (GPa) | MAE on Debye Temperature (K) | Extrapolative Precision | OOD Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge Regression | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| MODNet | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge |

| CrabNet | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge | Comparable to Ridge |

| Bilinear Transduction (MatEx) | 1.8× improvement | 1.8× improvement | 1.8× improvement | 3× improvement |

Data Veracity, Integration, and Longevity

Beyond distribution challenges, data-driven materials science faces fundamental issues with data quality and sustainability. Data veracity concerns arise from inconsistent measurement techniques, computational approximations, and experimental artifacts across diverse sources [16] [19]. The integration of experimental and computational data remains particularly challenging due to differing scales, resolutions, and underlying assumptions [16]. Furthermore, data longevity presents an ongoing concern, as materials data infrastructures require sustained investment and community engagement to remain operational and useful [16]. The lack of universal data standardization compounds these issues, creating barriers to interoperability and reproducibility across research initiatives [16].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Rigorous Dataset Splitting Methodologies

Proper experimental design is crucial for objectively evaluating foundation models. The following protocols represent current best practices:

MD-HIT Redundancy Control: For composition-based predictions, MD-HIT-composition calculates pairwise distances using composition descriptors (e.g., Magpie, MatScholar features). For structure-based predictions, MD-HIT-structure uses structural similarity metrics. A similarity threshold (typically 0.6-0.8) is applied to ensure no two samples exceeding this threshold are separated across training and test splits [18].

Leave-One-Cluster-Out Cross-Validation (LOCO CV): This method groups materials into chemically or structurally similar clusters, then systematically leaves out entire clusters for testing. This evaluates true extrapolation capability to novel material families rather than interpolation within similar chemistries [18].

K-fold Forward Cross-Validation (FCV): Samples are sorted by their property values before splitting, explicitly testing extrapolation to higher or lower property ranges than those represented in training data [18].

Evaluation Metrics for Discovery-Oriented Tasks

Beyond conventional metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), materials discovery requires specialized evaluation criteria:

Extrapolative Precision: Measures the fraction of true top OOD candidates correctly identified among the model's top predicted OOD candidates. This metric penalizes incorrectly classifying in-distribution samples as OOD, reflecting real discovery workflows [19].

OOD Recall: Quantifies the model's ability to recover high-performing candidates from the true OOD distribution, particularly important for identifying material extremes [19].

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) Overlap: Assesses how well the predicted OOD distribution aligns with the ground truth distribution shape, providing a distribution-level performance assessment [19].

Diagram 1: Rigorous model validation workflow for foundation models in materials science.

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

Performance Across Material Systems

Different modeling approaches demonstrate varying strengths depending on the material system, data representation, and target properties:

Table 2: Modeling Approach Comparison Across Material Systems

| Model Type | Solid-State Materials | Molecular Systems | Interpretability | Extrapolation Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical ML (RF, Ridge) | Moderate MAE on AFLOW, Matbench | Moderate MAE on MoleculeNet | Moderate (feature importance) | Limited for OOD ranges |

| Graph Neural Networks | Improved MAE on formation energy | Improved on molecular properties | Low (black box) | Moderate, degrades on OOD |

| Bilinear Transduction | 1.8× improvement in OOD precision | 1.5× improvement in OOD precision | Moderate (analogy-based) | Strong for value extrapolation |

| Interpretable Linear | Comparable accuracy on TCOs | Not widely applied | High (coefficient analysis) | Varies with basis functions |

Trade-offs Between Complexity and Interpretability

The pursuit of model interpretability presents significant trade-offs against predictive performance:

Black-box Models (Neural Networks, Kernel Methods): These often provide state-of-the-art predictive accuracy but operate as "black boxes" with limited explanatory capability. For example, the winning model in the NOMAD Kaggle competition used kernel ridge regression, which provides predictions based on similarity to training data but offers no fundamental understanding of underlying physical relationships [20].

Interpretable Linear Models: Research demonstrates that simple linear combinations of nonlinear basis functions can achieve accuracy comparable to black-box methods for several material systems, including transparent conducting oxides and elpasolite crystals [20]. These models enable direct coefficient analysis, validation against physical principles, and clear understanding of failure modes.

Specialized Architectures: Approaches like Bilinear Transduction reparameterize the prediction problem to focus on how property values change as a function of material differences rather than predicting absolute values from new materials [19]. This analogy-based approach shows improved extrapolation while maintaining some interpretability through its difference-based reasoning.

Critical Data Infrastructure and Algorithms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Materials Informatics

| Resource | Type | Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project Database | Computational Database | Provides calculated properties for known and hypothetical materials | Training data for property prediction, benchmark comparisons |

| Matbench | Benchmarking Platform | Automated leaderboard for ML algorithms predicting material properties | Standardized model evaluation, performance comparisons |

| MD-HIT | Data Processing Algorithm | Controls dataset redundancy by ensuring similarity thresholds | Realistic model evaluation, avoiding overestimated performance |

| Bilinear Transduction | Prediction Algorithm | Enables extrapolation by learning property changes via material differences | OOD property prediction, discovering high-performance materials |

| SISSO | Feature Selection | Creates analytical formulas from physical properties via symbolic regression | Interpretable model development, physical insight discovery |

Implementation Considerations for Foundation Models

Successfully validating foundation models requires attention to several practical implementation factors:

Data Provenance: Documenting the origin, computational methods (e.g., DFT functional type), and potential biases of training data is essential for understanding model limitations and applicability domains [16] [21].

Uncertainty Quantification: Implementing rigorous uncertainty estimates enables models to express confidence levels and guides targeted experimental validation, particularly important for extrapolative predictions [18].

Multi-fidelity Data Integration: Combining high-accuracy computational data with noisy experimental measurements requires specialized approaches to leverage the strengths of each data type while mitigating their respective weaknesses [16].

Diagram 2: Interdependencies of critical requirements for foundation models in materials science.

The validation of foundation models for materials property prediction research hinges on addressing critical data requirements and methodological challenges. Dataset redundancy, out-of-distribution generalization, and the interpretability-accuracy trade-off represent fundamental hurdles that must be overcome to achieve the vision of a "Materials Ultimate Search Engine." Rigorous experimental protocols, including proper dataset splitting techniques and discovery-oriented evaluation metrics, provide essential frameworks for objective model comparison. As the field progresses, the integration of physically-informed architectures with robust uncertainty quantification appears most promising for developing foundation models that are not only predictive but also trustworthy and actionable for accelerating materials discovery. The convergence of improved data infrastructure, specialized algorithms, and rigorous validation standards positions the materials informatics community to substantially reduce the traditional 20-year timeline for materials development and deployment.

Distinction from Universal Interatomic Potentials (UIPs) and Traditional Models

The field of computational materials science has undergone a paradigm shift with the emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), which bridge the critical gap between the high accuracy but computational cost of quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the efficiency but limited accuracy of traditional empirical potentials [22]. Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) represent the latest advancement—foundational models trained on extensive datasets that aim to achieve high accuracy across diverse chemical spaces and crystal structures without system-specific retraining [23] [24]. This guide provides a structured comparison between uMLIPs and traditional models, detailing their performance differences, validation methodologies, and practical applications to inform researchers in selecting appropriate tools for materials property prediction.

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Accuracy

Foundational Principles and Architectural Comparison

The fundamental distinction between traditional and machine learning potentials lies in their approach to modeling the Potential Energy Surface (PES). Traditional empirical potentials rely on fixed physical functional forms with limited parameters (e.g., Lennard-Jones, Embedded-Atom Method, Stillinger-Weber) fitted to reproduce specific material properties [25] [26]. While computationally efficient, this approach sacrifices transferability and struggles with complex chemical environments. In contrast, uMLIPs employ flexible, data-driven models (e.g., graph neural networks, message-passing architectures) that learn the PES directly from reference quantum mechanical data, enabling them to capture complex many-body interactions without predefined physical constraints [23] [27].

Architecturally, uMLIPs incorporate geometric equivariance, embedding rotational and translational symmetries directly into their network structures to ensure physical consistency for predictions of scalar (energy), vector (forces), and tensor (stress) quantities [27]. Modern uMLIP frameworks like MACE implement explicit many-body messages through hierarchical expansions, while models like CHGNet incorporate charge information via magnetic moment constraints to capture electronic structure effects [28].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Potential Types for Material Properties Prediction

| Property Category | Traditional Potentials | Specific MLIPs | Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) | Key Benchmark Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy & Forces | Moderate accuracy near equilibrium; deteriorates significantly for distorted structures | High accuracy (MAE: ~1-5 meV/atom) within training domain | Variable accuracy (MAE: ~35 meV/atom for CHGNet); near-DFT for equilibrium structures [23] [27] | uMLIPs excel for equilibrium/near-equilibrium configurations |

| Phonon Properties | Often inadequate for complex lattices; may predict imaginary frequencies | Highly accurate when trained with relevant data | Substantial variation: MACE-MP-0 and MatterSim-v1 achieve high accuracy, while others show significant errors despite good force predictions [23] | Phonon benchmarking reveals limitations not apparent from energy/force metrics alone |

| Elastic Properties | Reasonable for simple metals; poor for complex ceramics and anisotropic materials | Accurate for trained systems; requires specialized training | SevenNet highest accuracy; MACE and MatterSim balance accuracy with efficiency; CHGNet less effective overall [28] | Elastic constants require precise second derivatives of PES, presenting distinct challenges |

| Structural Optimization | Limited transferability; may stabilize unphysical structures | High reliability for known configurations | CHGNet and MatterSim-v1 most reliable (failure rate: ~0.1%); models with non-derivative forces (ORB, eqV2-M) show higher failure rates (up to 0.85%) [23] | Force consistency critical for geometry convergence |

| Computational Efficiency | Fastest (orders of magnitude faster than DFT) | Moderate (100-1000x faster than DFT) | Moderate to high (varies by architecture); MACE offers favorable accuracy-efficiency balance [28] | uMLIPs enable large-scale MD simulations inaccessible to DFT |

Table 2: uMLIP Model Performance Specialization

| uMLIP Model | Strengths | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP-0 | High-order equivariant messages; excellent phonon and elastic property prediction [23] [28] | Higher computational cost | Mechanical properties, vibrational spectra |

| CHGNet | Charge-informed embedding; reliable structural relaxation [23] [28] | Lower energy accuracy; moderate elastic property performance | Phase stability, crystal structure prediction |

| MatterSim-v1 | Active learning across chemical space; balanced accuracy [23] [28] | — | General-purpose materials screening |

| SevenNet | Superior elastic property prediction [28] | — | Mechanical property prediction |

| M3GNet | Pioneering universal model; successful in crystal structure prediction [24] | — | Materials discovery, stable phase identification |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Workflows

Standardized Validation Methodologies

Robust validation is crucial for assessing uMLIP reliability, particularly given their "black-box" nature compared to physics-based traditional potentials. A recommended three-stage sequential workflow includes [25]:

- Preliminary Validation: Evaluating numerical performance on energies, forces, and stresses for configurations similar to training data.

- Static Property Prediction: Testing transferability to properties not explicitly included in training (lattice constants, elastic constants, phonon spectra).

- Dynamic Property Prediction: Assessing performance in molecular dynamics simulations (diffusion coefficients, phase transitions, thermal conductivity).

This methodology emphasizes the importance of going beyond energy and force errors to evaluate performance for specific scientific applications. For example, a uMLIP might exhibit excellent force metrics yet fail to reproduce correct phonon dispersion spectra due to insufficient curvature information in the training data [23].

Benchmarking Studies and Protocols

Recent benchmarking initiatives have established standardized protocols for uMLIP evaluation. Phonon property benchmarks employ datasets of approximately 10,000 non-magnetic semiconductors to assess harmonic phonon properties, including phonon band structures and density of states [23]. Elastic property benchmarks evaluate nearly 11,000 elastically stable materials from the Materials Project database, calculating elastic constants through stress-strain relationships and deriving mechanical moduli (bulk, shear, Young's) [28]. For materials discovery applications, benchmarking involves testing the ability to rediscover known experimental structures excluded from training data and predict novel stable compounds [24].

Diagram 1: Sequential workflow for MLIP validation. This three-stage process progresses from basic numerical metrics to application-specific property prediction [25].

Computational Frameworks and Databases

Table 3: Essential Resources for uMLIP Research and Application

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| uMLIP Implementations | M3GNet, CHGNet, MACE, SevenNet, MatterSim | Pretrained universal potentials for diverse materials systems [23] [28] [24] |

| Training Frameworks | DeePMD-kit, Allegro, NequIP | Software packages for developing custom system-specific MLIPs [25] [27] |

| Reference Databases | Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW, NOMAD | Sources of DFT reference data for training and validation [23] [28] |

| Specialized Benchmarks | Matbench Discovery, Phonon Database (MDR) | Curated datasets for specific property validation [23] [28] |

| Simulation Packages | LAMMPS, ASE | Molecular dynamics engines with MLIP integration [25] [24] |

Universal MLIPs represent a transformative advancement in atomistic simulation, offering unprecedented combination of accuracy and transferability across broad chemical spaces. However, their performance varies significantly across different property classes, with particular strengths in energy, force, and structural relaxation tasks, while exhibiting more variable performance for second-derivative properties like phonons and elastic constants [23] [28]. Traditional potentials remain relevant for applications requiring maximum computational efficiency where their simplified physical forms provide sufficient accuracy.

Future developments in uMLIPs will likely focus on improving their robustness for far-from-equilibrium configurations, enhancing computational efficiency, and increasing physical interpretability through techniques like symbolic regression [26]. The establishment of standardized benchmarking protocols and validation workflows will be crucial for guiding model selection and advancing the field toward truly reliable foundation models for materials property prediction [25] [29].

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional trial-and-error methods and computational screening toward a new era of artificial intelligence-driven design. Foundation models—large-scale AI systems trained on broad data that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks—are catalyzing this shift by enabling scalable, general-purpose systems for scientific discovery [1] [6]. Unlike traditional machine learning models limited to narrow tasks, foundation models exhibit cross-domain generalization and emergent capabilities that make them particularly valuable for materials research challenges spanning diverse data types and scales [6].

This evolution represents a fundamental reorientation in how researchers approach materials discovery. The traditional paradigm relied heavily on human intuition and expensive, time-consuming experimental cycles. The emerging paradigm leverages AI to directly generate novel materials tailored to specific property requirements, dramatically accelerating the path from conception to realization [30] [31]. This article examines the current state of foundation models in materials science, comparing their capabilities in property prediction versus generative design, and explores the experimental frameworks validating their potential for revolutionizing materials innovation.

Foundation Models: Architectural Foundations and Modalities

Model Architectures and Their Applications

Foundation models in materials science primarily utilize transformer-based architectures, which can be categorized into distinct types optimized for different scientific tasks. The architectural choice fundamentally determines a model's capabilities and applications in materials research.

Table: Foundation Model Architectures in Materials Science

| Architecture Type | Primary Function | Materials Science Applications | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | Understanding and representing input data | Property prediction, materials classification | BERT-based models [1] |

| Decoder-Only | Generating new outputs token-by-token | Molecular generation, materials design | GPT-based models [1] |

| Diffusion Models | Generating structures through iterative denoising | 3D materials generation, crystal structure prediction | MatterGen, DiffCSP [32] [30] |

Encoder-only models, drawing from the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) architecture, excel at understanding and representing input data, making them ideal for property prediction tasks [1]. These models generate meaningful representations that can be used for further processing or predictions. Decoder-only models, inspired by Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT) architectures, are designed specifically for generating new outputs by predicting one token at a time based on given input and previously generated tokens, making them suitable for creating new chemical entities [1].

A significant limitation in current materials foundation models is their predominant training on 2D molecular representations such as SMILES or SELFIES, which omits critical 3D conformational information [1]. This shortcoming exists primarily due to the disparity in available datasets—current foundation models train on datasets containing approximately 10^9 molecules, a scale not readily available for 3D data [1]. Notable exceptions include models for inorganic solids like crystals, which often leverage 3D structures through graph-based or primitive cell feature representations [1].

Data Requirements and Multimodal Integration

The performance of foundation models hinges on both the volume and quality of training data. Materials with intricate dependencies where minute details significantly influence properties—a phenomenon known as "activity cliffs"—present particular challenges [1]. For instance, in high-temperature cuprate superconductors, critical temperature (Tc) can be profoundly affected by subtle variations in hole-doping levels, requiring models with rich training data to capture these effects [1].

Chemical databases including PubChem, ZINC, and ChEMBL provide structured information commonly used to train chemical foundation models [1]. However, these sources face limitations in scope, accessibility due to licensing restrictions, dataset size, and biased data sourcing [1]. Modern data extraction approaches must therefore parse multiple modalities—text, tables, images, and molecular structures—from scientific documents, patents, and presentations to construct comprehensive datasets [1].

Advanced data extraction techniques are evolving beyond traditional named entity recognition (NER) approaches to incorporate multimodal learning. Specialized algorithms like Plot2Spectra demonstrate how data can be extracted from spectroscopy plots in scientific literature, enabling large-scale analysis of material properties inaccessible to text-based models [1]. Similarly, DePlot converts visual representations like charts into structured tabular data for reasoning by large language models [1].

Property Prediction: Current Capabilities and Methodologies

Experimental Frameworks for Validating Predictive Models

Property prediction represents a core application of foundation models in materials science, enabling researchers to bypass prohibitively expensive physics-based simulations. The validation of these models follows rigorous experimental protocols centered on benchmark datasets and standardized evaluation metrics.

The methodology for validating property prediction models typically involves several key stages. First, models are pre-trained on large, unlabeled datasets such as the 608,000 stable materials from the Materials Project and Alexandria databases [30]. This pre-training occurs through self-supervised learning, where models learn general representations of materials structures without specific property labels. Following pre-training, models undergo fine-tuning on smaller, labeled datasets specific to target properties such as electronic band gap, bulk modulus, or magnetic properties [1].

The evaluation phase employs holdout test sets with known properties to assess predictive accuracy. Standard metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for continuous properties, and accuracy or F1 score for classification tasks. Cross-validation techniques ensure robustness, and models are frequently tested on out-of-distribution examples to assess generalization capabilities [1]. For quantum materials, additional validation through first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations provides physics-based verification [32].

Diagram: Property Prediction Model Validation Workflow

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Analysis

Encoder-only models based on the BERT architecture currently dominate property prediction tasks, though GPT-based approaches are gaining traction [1]. These models demonstrate particular strength in predicting properties from 2D molecular representations, though this introduces limitations for properties dependent on 3D conformation.

Table: Performance Comparison of Property Prediction Models

| Model/Approach | Architecture Type | Data Modality | Key Properties Predicted | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BERT-based Models [1] | Encoder-only | 2D (SMILES/SELFIES) | General chemical properties | Varies by specific implementation |

| MatterSim [30] | Not specified | 3D structures | Multiple material properties | AI emulator for rapid simulation |

| Graph Neural Networks [1] | Graph-based | 3D structures | Material properties for inorganic solids | State-of-the-art for crystals |

| Traditional QSPR | Hand-crafted features | 2D/3D | Approximate initial screening | Lower than FM approaches |

The integration of AI emulators like MatterSim exemplifies the fifth paradigm of scientific discovery, significantly accelerating material property simulations [30]. When combined with generative models, these systems create a "flywheel" effect that speeds both simulation and exploration of novel materials [30].

For property prediction tasks, the key advantage of foundation models lies in transfer learning—where models pre-trained on vast datasets can be fine-tuned with limited labeled data for specific applications. This approach effectively addresses the data scarcity problem common in materials science, where comprehensive property data may be available for only a fraction of known compounds [1].

Generative Design: Emerging Paradigms and Applications

Architectures for Generative Materials Design

Generative design represents a paradigm shift from screening existing materials to actively creating novel materials tailored to specific applications. Diffusion models have emerged as particularly powerful architectures for this task, operating on the 3D geometry of materials to generate novel structures [30].

These models work analogously to image diffusion models: where image models generate pictures from text prompts by modifying pixel colors from noisy images, materials diffusion models generate proposed structures by adjusting positions, elements, and periodic lattice from random structures [30]. The diffusion architecture is specifically designed for materials to handle specialties like periodicity and 3D geometry, enabling the generation of physically plausible crystal structures [30].

MatterGen exemplifies this approach, implementing a novel diffusion architecture that achieves state-of-the-art performance in generating novel, stable, and diverse materials [30]. The model can be fine-tuned with labeled datasets to generate novel materials given desired conditions including target chemistry, symmetry, and electronic, magnetic, and mechanical property constraints [30]. This capability enables a fundamentally new approach to materials discovery—moving beyond the limited set of known materials to explore the full space of chemically plausible compounds.

Constrained Generation Methodologies

A significant advancement in generative design is the ability to incorporate specific design rules or constraints during the generation process. The SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model) framework demonstrates this capability, enabling diffusion models to adhere to user-defined geometric constraints at each iterative generation step [32].

This approach addresses a critical limitation in mainstream generative models from major technology companies, which typically optimize for stability but struggle to create materials with exotic quantum properties [32]. With SCIGEN, researchers can steer models to create materials with unique structural patterns like Kagome and Lieb lattices that give rise to quantum properties but are rare in training datasets [32].

The methodology involves blocking generations that don't align with structural rules during the sampling process. In testing, researchers applied SCIGEN to the DiffCSP model to generate materials with Archimedean lattices—2D lattice tilings associated with quantum phenomena like spin liquids and flat bands [32]. The system generated over 10 million candidate materials with these specialized lattices, with approximately one million surviving stability screening [32]. This constrained generation capability is particularly valuable for quantum materials research, where specific geometric patterns are necessary (though not sufficient) conditions for desired quantum behaviors.

Diagram: Generative Design and Experimental Validation Pipeline

Comparative Analysis: Performance Across Design Tasks

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparison between generative and screening approaches reveals distinct advantages for generative models in exploring novel chemical spaces. In head-to-head evaluations, MatterGen continued to generate novel candidate materials with high bulk modulus above 400 GPa, while screening baselines saturated due to exhausting known candidates [30]. This demonstrates the generative approach's ability to access regions of materials space beyond existing databases.

The experimental validation of generative models provides compelling evidence of their practical utility. In one case, researchers synthesized a novel material, TaCr2O6, whose structure was generated by MatterGen after conditioning on a bulk modulus value of 200 GPa [30]. The synthesized material's structure aligned with MatterGen's prediction, exhibiting compositional disorder between Ta and Cr atoms [30]. Experimentally measured bulk modulus was 169 GPa compared to the 200 GPa design specification, representing a relative error below 20%—considered very close from an experimental perspective [30].

In another validation, SCIGEN-equipped models generated two previously undiscovered compounds, TiPdBi and TiPbSb, which were subsequently synthesized experimentally [32]. Subsequent experiments showed the AI model's predictions largely aligned with the actual material's properties, confirming the method's ability to create viable quantum material candidates [32].

Task-Specific Capability Assessment

The relative performance of property prediction versus generative design models varies significantly across different materials research tasks. Each approach exhibits distinct strengths and limitations.

Table: Capability Comparison Across Materials Research Tasks

| Research Task | Property Prediction Strength | Generative Design Strength | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening | Excellent: Fast property estimation | Limited: Not designed for screening | Prediction limited to known chemical spaces |

| Novel Materials Discovery | Limited: Can only assess known materials | Excellent: Creates new structures | May generate unstable structures |

| Quantum Materials Design | Moderate: Can predict properties if trained | Excellent: Constrained generation possible | Limited by training data scarcity |

| Inverse Design | Not applicable | Transformative: Direct generation from properties | Requires accurate property-conditioning |

Generative models particularly excel at inverse design problems—where researchers begin with desired properties and work backward to identify structures that exhibit them. This capability fundamentally inverts the traditional materials discovery workflow [30]. Whereas screening methods are limited to existing databases, generative models can propose entirely novel compounds, significantly expanding the explorable materials space [30].

However, generative approaches face their own limitations, particularly regarding stability assessment. While models can generate millions of candidate structures, only a fraction (approximately 10% in the case of SCIGEN-generated Archimedean lattices) typically survive stability screening [32]. This limitation underscores the importance of integrating generative models with robust stability predictors in practical workflows.

Experimental Validation Frameworks

Synthesis and Characterization Protocols

The ultimate validation of AI-discovered materials occurs through experimental synthesis and characterization. The protocol for validating generative model outputs follows a rigorous multi-stage process that transitions from computational prediction to physical realization.

For computationally generated materials, the first validation stage involves stability screening using established metrics like energy above hull, which assesses thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases [30]. Promising candidates then undergo detailed property simulation using first-principles computational methods, typically density functional theory (DFT), to verify predicted electronic, magnetic, or mechanical properties [32].

Successful computational candidates proceed to experimental synthesis, which varies by material class but often employs techniques like solid-state reaction for inorganic compounds or solvothermal methods for metal-organic frameworks [32] [30]. In the case of MatterGen-generated TaCr2O6, researchers successfully synthesized the material and confirmed its structure primarily through X-ray diffraction, which aligned with the predicted model despite some compositional disorder [30].

Experimental property characterization provides the final validation step. For TaCr2O6, the measured bulk modulus of 169 GPa compared to the 200 GPa design specification demonstrates the model's ability to guide synthesis toward materials with desired mechanical properties, even with moderate error margins expected in experimental materials science [30].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

The experimental validation of AI-predicted materials relies on specialized research reagents and characterization tools that enable synthesis and property measurement.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | High-purity elemental powders (Ta, Cr, Ti, Pd, etc.) | Source materials for solid-state synthesis | Synthesis of novel inorganic compounds [32] [30] |

| Characterization Equipment | X-ray diffractometer (XRD) | Crystal structure verification | Comparison with AI-predicted structures [30] |

| Property Measurement | Physical property measurement system (PPMS) | Measurement of mechanical, electronic, magnetic properties | Experimental validation of predicted properties [32] |

| Computational Resources | DFT codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | First-principles property validation | Screening candidate materials pre-synthesis [32] |

| High-Throughput Synthesis | Automated laboratories | Accelerated synthesis and testing | Rapid experimental iteration [31] |

The integration of automated experimental platforms represents a particularly promising development, creating closed-loop systems where AI both designs materials and directs their experimental validation [31]. These systems enable iterative cycles informed by rapid AI feedback, dramatically accelerating the optimization of material formulations [31].

The comparison between property prediction and generative design capabilities reveals complementary strengths that suggest their integration will drive future advances in materials research. Property prediction models excel at rapid assessment of known materials spaces, while generative models enable exploration beyond existing databases. The most powerful workflows will likely combine both approaches, using generative models to propose novel candidates and prediction models to screen them before experimental investment.

Significant challenges remain before foundation models achieve widespread industrial implementation in materials science. Data limitations persist, as AI model effectiveness depends on access to vast amounts of high-quality experimental data, yet materials development datasets often suffer from incompleteness, inconsistency, and inaccuracy [31]. The generalization of models beyond controlled laboratory settings to complex production environments presents additional hurdles, as materials performance varies significantly across different application contexts [31].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: scalable pretraining with multimodal materials data, continual learning systems that incorporate newly published research, improved data governance frameworks, and enhanced trustworthiness through uncertainty quantification [6]. As these technical challenges are addressed, foundation models are poised to transform materials science from a discovery-driven discipline to a design-oriented field, unlocking the advanced materials required for more efficient solar cells, higher-capacity batteries, and critical carbon capture technologies [31].

Implementation Frameworks and Domain-Specific Applications

The emergence of atomistic foundation models (FMs) represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and drug development. These models, pre-trained on massive, diverse datasets, learn fundamental representations of atomic structures and their interactions, capturing the universal physical principles that govern the potential energy surface (PES) [33]. Unlike traditional task-specific models that require extensive labeled data for each new application, foundation models can be efficiently fine-tuned with limited data for diverse downstream tasks, offering unprecedented potential for accelerating materials discovery and property prediction [34] [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of five leading atomistic foundation models—JMP, MatterSim, ORB, MACE, and EquiformerV2—focusing on their architectural innovations, performance metrics, and applicability for validating materials properties in research settings.

Model Architectures and Technical Specifications

Atomistic foundation models employ sophisticated geometric deep learning architectures that incorporate fundamental physical principles, particularly invariance and equivariance to Euclidean symmetries (rotation, translation, and reflection) [34] [33]. The table below summarizes the key technical specifications of the five models examined in this guide.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Atomistic Foundation Models

| Model | Release Year | Architecture Type | Key Architectural Features | Training Objectives | Parameter Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JMP | 2024 | Not Specified | Jointly pre-trained on diverse molecular systems [35] | Energy, Forces [34] | 30M (JMP-S), 235M (JMP-L) [34] |

| MatterSim | 2024 | Not Specified | Designed for broad materials simulation [36] [34] | Energy, Forces, Stress [34] | 4.55M [34] |

| ORB | 2024 | Not Specified | Combines denoising with supervised targets [34] | Denoising + Energy, Forces, Stress [34] | 25.2M [34] |

| MACE | 2023 | Equivariant GNN | Higher-order message passing; Many-body interactions [34] [35] | Energy, Forces, Stress [34] | 4.69M (MACE-MP-0) [34] |

| EquiformerV2 | 2024 | Equivariant Transformer | Equivariant attention; Transformer architecture [34] | Energy, Forces, Stress [34] | 31.2M (EqV2-S), 86.6M (EqV2-M) [34] |

These models vary significantly in their parameter counts and architectural approaches. MACE employs a higher-order message passing scheme to efficiently capture many-body interactions, while EquiformerV2 adapts the powerful transformer architecture to equivariant graph representations [34] [35]. ORB utilizes a unique hybrid approach combining denoising objectives with traditional supervised learning targets [34].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for validating the performance of atomistic foundation models across diverse chemical systems and prediction tasks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent evaluations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Benchmark Tasks

| Model | Force MAE (meV/Å) | Energy MAE (meV/atom) | Notable Strengths | Primary Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JMP | Not Specified | Not Specified | Large-scale pretraining on 120M structures [34] | Diverse molecular systems [35] |

| MatterSim | Not Specified | Not Specified | Balanced architecture for broad materials [34] | General materials simulation [36] |

| ORB | Not Specified | Not Specified | Hybrid training approach [34] | Not Specified |

| MACE | 19.4-42.5* [35] | 0.23-1.2* [35] | High accuracy on materials with complex interactions [35] | Molecules, bulks, surfaces [35] |

| EquiformerV2 | Competitive on OC20 [35] | 0.24 eV (OC20) [35] | Strong energy prediction on catalysis datasets [35] | Catalysis, molecular systems [35] |

Note: MAE values for MACE represent ranges across different datasets (formate decomposition, defected graphene); Performance data for other models was not fully quantified in the search results.

According to the LAMBench benchmark, which evaluates Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) on generalizability, adaptability, and applicability, current models still show a significant gap from the ideal universal potential energy surface [37]. The benchmark emphasizes that enhancing performance requires training with data from diverse research domains and maintaining model conservativeness (where forces are derived as gradients of energy) for proper physical behavior in molecular dynamics simulations [37].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

The validation of atomistic foundation models follows rigorous protocols using standardized datasets and evaluation metrics. The LAMBench framework provides a comprehensive approach assessing three critical capabilities [37]:

- Generalizability: Performance on both in-distribution and out-of-distribution test datasets

- Adaptability: Efficiency in fine-tuning for tasks beyond potential energy prediction

- Applicability: Stability and efficiency in real-world simulations like molecular dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the core validation workflow for atomistic foundation models:

Key Validation Datasets and Metrics

Researchers employ several established datasets to evaluate model performance across different chemical domains and task types:

- OC20 (Open Catalyst 2020): Focuses on catalytic surface reactions with Structure-to-Energy-and-Force (S2EF) tasks; uses Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energy (eV) and forces (meV/Å) [35]

- Matbench Discovery: Evaluates material stability predictions using F1 scores and DAF (Displacement Above Fermi) metrics [35]

- MD17: Contains molecular dynamics trajectories of small molecules; assesses force and energy prediction accuracy [37]

- Formate Decomposition Dataset: Represents catalytic surface reactions; measures MAE for forces and energies [35]

- Zeolite Dataset: Tests performance on complex porous materials with 16 distinct zeolite types [35]

Performance metrics must be interpreted in the context of the specific dataset and task requirements. For applications requiring energy conservation in molecular dynamics, conservative models (where forces are gradients of energy) are essential despite potentially higher force errors in static predictions [37].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing and validating atomistic foundation models requires specialized software frameworks and computational resources. The following table outlines essential "research reagents" for working with these models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Atomistic Foundation Models

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Foundation Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterTune | Software Framework | Fine-tuning platform for atomistic FMs [36] [34] | Supports all five models; enables transfer learning |

| LAMBench | Benchmarking System | Evaluation of Large Atomistic Models [37] | Standardized performance assessment |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Software Library | Atomistic simulations and data handling [34] | Standardized data abstraction |

| ALCF Supercomputers | Computational Resource | High-performance computing for training [4] | Enables billion-molecule training |

| SMILES/SMIRK | Data Representation | Text-based molecular representations [4] | Input formatting for molecular FMs |

These tools collectively support the end-to-end workflow for foundation model validation, from data preparation and model training to performance benchmarking and deployment in production research environments.