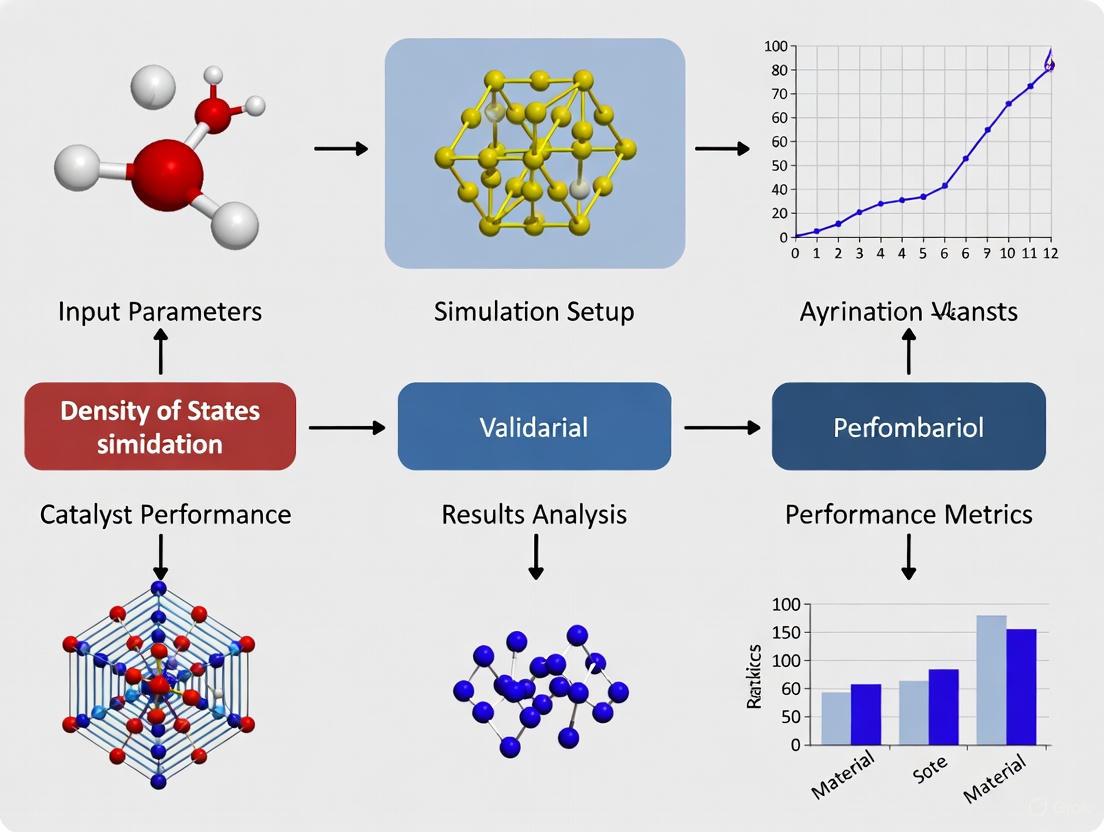

Validating Density of States Similarity for Predictive Catalyst Design: From DFT Fundamentals to Experimental Confirmation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to validate the use of Density of States (DOS) similarity as a predictive descriptor for catalyst performance.

Validating Density of States Similarity for Predictive Catalyst Design: From DFT Fundamentals to Experimental Confirmation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to validate the use of Density of States (DOS) similarity as a predictive descriptor for catalyst performance. It covers the foundational role of DOS in determining catalytic properties, practical methodologies for calculating and comparing DOS, strategies for troubleshooting computational results and optimizing predictions, and rigorous approaches for validating DOS similarity against experimental performance metrics like activity, selectivity, and stability. By synthesizing insights from density functional theory (DFT) and experimental characterization, this guide aims to establish DOS similarity as a reliable tool for accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation catalysts in energy and chemical applications.

The Electronic Structure Link: Why DOS is a Fundamental Descriptor in Catalysis

The Projected Density of States (PDOS) is a critical computational tool in catalysis research that decomposes the total electronic density of states (DOS) of a system into contributions from specific atomic orbitals, such as s, p, or d orbitals, or from individual atoms or molecular fragments. While the total DOS provides the number of electronically allowed states at each energy level, the PDOS reveals which specific atomic components these states originate from. This decomposition is fundamental for understanding a catalyst's electronic fingerprint, as it directly links electronic structure features—such as the presence of frontier orbitals or specific d-band characteristics—to catalytic activity and selectivity. In the context of catalyst discovery, validating similarity in PDOS between different materials provides a powerful rationale for predicting similar catalytic performance, moving beyond structural comparisons to electronic-structure-based design principles.

The utility of PDOS extends across various catalytic domains, from heterogeneous electrocatalysis on solid surfaces to molecular catalysis. For instance, in the design of single-atom catalysts (SACs) for the two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e- ORR) to produce hydrogen peroxide, the coordination environment of the metal center dictates its catalytic performance. PDOS analysis can reveal how modifications in the coordination sphere (e.g., changing coordinating atoms from N to S or C) alter the metal's d-band center and the resulting adsorption strengths of key reaction intermediates, thereby influencing activity and selectivity [1]. Similarly, in molecular electrochemistry, analyzing the PDOS of metalloporphyrins can pinpoint the specific metal d-orbitals involved in CO₂ binding during electrochemical CO₂ reduction, guiding the rational selection of metal centers and ligand structures [2].

Computational Analysis of PDOS

Core Methodology: Density Functional Theory (DFT)

The primary method for calculating the PDOS is Density Functional Theory (DFT), a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems.

- Fundamental Principle: DFT operates on the principle that the ground-state energy and properties of a system are uniquely determined by its electron density. This simplifies the many-body Schrödinger equation into a set of solvable equations, making it feasible to study complex catalytic systems.

- Modeling the Electrochemical Interface: For electrocatalysis, standard DFT must be adapted to model the electrochemical solid-liquid interface. Methodologies such as the implicit solvation model (e.g., COSMO) and the Grand-Canonical DFT framework are employed to account for the effects of solvent, electrolytes, and applied electrode potential [3].

- Software and Codes: Common software packages for these calculations include VASP (Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package), Gaussian, and NWChem. These codes are used for geometry optimization, electronic structure calculation, and subsequent PDOS analysis [2] [4].

Protocol: Calculating and Analyzing PDOS for a Catalyst

Objective: To compute and analyze the PDOS of a model catalyst to identify the electronic origins of its catalytic activity.

Materials/Software Requirements:

- Computational Software: A DFT-compatible software package such as VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, or Gaussian.

- Structure Visualization Tool: Software like VESTA or CrystalMaker for building and visualizing atomic structures.

- Post-Processing Tool: Codes like VASPkit or pymatgen for extracting and plotting PDOS data from DFT output files.

Procedure:

- Model Construction:

- Build the atomic structure of the catalyst. For a surface reaction, this typically involves creating a periodic slab model with sufficient vacuum thickness (e.g., 15-20 Å) to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images [2].

- For supported catalysts (e.g., single-atom catalysts), construct a model of the support (e.g., graphene, CeO₂ surface) with the catalytic metal atom anchored in the desired coordination environment.

Geometry Optimization:

- Perform a full geometry optimization of the constructed model until the forces on all atoms are below a selected convergence threshold (typically 0.01 to 0.03 eV/Å) and the total energy is converged [4]. This step finds the most stable atomic configuration.

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation:

- Run a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure with a dense k-point mesh to obtain the accurate charge density and Hamiltonian of the system. This is the input for the DOS calculation.

DOS and PDOS Calculation:

- Execute a non-self-consistent calculation (using the pre-converged charge density) with an even denser k-point grid to obtain a smooth DOS and PDOS. The projection is typically done using the projected augmented wave (PAW) method in VASP or a similar population analysis in other codes.

Data Analysis:

- Extract the total DOS and the PDOS onto the relevant atoms and orbitals (e.g., d-orbitals of the metal center, p-orbitals of coordinating atoms).

- Analyze the PDOS to identify key features:

- Locate the Fermi energy (EF) and note the DOS at EF, which can indicate metallic or insulating behavior.

- Identify the position and shape of specific orbital bands, most notably the d-band center for transition metal catalysts, a common descriptor for adsorption energy.

- Examine the overlap between PDOS of different atoms to infer bonding and antibonding interactions.

Table 1: Key Post-Processing Analyses for PDOS Data.

| Analysis Type | Description | Relevance to Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center (ε_d) | The first moment of the d-band PDOS; average energy of the d-states relative to the Fermi level. | A key descriptor for adsorption strength on transition metals; higher ε_d typically correlates with stronger binding. |

| Orbital Overlap/COHP | Analysis of bonding interactions (e.g., Crystal Orbital Hamiltonian Population). | Identifies the strength and character (bonding/antibonding) of interactions between catalyst and adsorbate [4]. |

| Band Gap | Energy difference between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied states. | Indicates whether the material is a metal, semiconductor, or insulator, influencing electron transfer. |

| PDOS Comparison | Comparing PDOS of a catalyst before and after adsorption or between different catalyst designs. | Reveals which catalyst orbitals interact with adsorbates, guiding rational design [2]. |

Experimental Validation of PDOS

Computational PDOS requires validation against experimental techniques that probe the electronic structure of materials. Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS) is a direct method for measuring the local density of states (LDOS).

Protocol: Measuring LDOS with STS

Objective: To experimentally determine the LDOS of a catalyst surface to validate computed PDOS.

Principle: STS extends Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) by measuring the differential conductance (dI/dV) at a specific location on the surface. At a small bias voltage, the dI/dV signal is approximately proportional to the LDOS of the sample at the energy corresponding to the bias voltage [5].

Materials:

- STM/STS Instrumentation: A scanning tunneling microscope capable of spectroscopy measurements, housed in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber to ensure surface cleanliness.

- Sample: A clean, well-defined single-crystal surface of the catalyst material.

- STM Probe: An electrochemically etched sharp metallic tip (e.g., tungsten or Pt-Ir).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clean the catalyst sample in the UHV chamber using cycles of sputtering (e.g., with Ar⁺ ions) and annealing to achieve an atomically clean and ordered surface.

- Tip Preparation: Characterize and sharpen the STM tip on a clean metal surface to ensure atomic resolution.

- STM Imaging: Acquire a constant-current STM image of the surface to identify the region of interest (e.g., a specific atomic site or defect).

- STS Measurement:

- Position the STM tip over the desired location.

- Disable the feedback loop.

- Ramp the bias voltage (V) between the tip and the sample while recording the tunneling current (I).

- Perform this I-V measurement multiple times for averaging.

- Data Processing:

- Numerically differentiate the I-V curve to obtain the dI/dV vs. V spectrum.

- Normalize the dI/dV spectrum by (I/V) to correct for the exponential dependence of the tunneling current on the barrier width, yielding a quantity that is more directly proportional to the LDOS [5].

- Comparison with Computation:

- Compare the experimentally obtained LDOS spectrum with the computed total DOS or PDOS. Alignment is typically done using a prominent spectral feature or the Fermi edge.

Table 2: Key Techniques for Electronic Structure Validation.

| Technique | What It Measures | Role in PDOS Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS) | Local Density of States (LDOS) | Directly measures LDOS, providing a spatial map of electronic states for comparison with atom-projected PDOS [5]. |

| X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental composition and chemical states. | Validates the oxidation state of atoms in the catalyst, which should be consistent with the electronic structure in the PDOS calculation. |

| Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) | Occupied density of states near the Fermi level. | Provides experimental data on the valence band structure, crucial for calibrating the energy alignment of computed PDOS. |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Machine Learning

The concept of PDOS is being leveraged by machine learning (ML) to dramatically accelerate materials discovery. ML models can predict the DOS/PDOS directly from the atomic structure, bypassing the computational cost of DFT.

One advanced framework, Mat2Spec, uses graph neural networks (GNNs) to encode crystalline structures and predicts spectral properties like the phonon DOS (phDOS) and electronic DOS (eDOS) [6]. This approach employs contrastive learning and probabilistic embedding to handle the complexity of spectral data, achieving state-of-the-art performance in predicting ab initio eDOS. This capability allows for the high-throughput screening of candidate materials for specific electronic features, such as identifying materials with band gaps below the Fermi level—a characteristic valuable for thermoelectric and transparent conductor applications [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PDOS Studies.

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian) | Performs the core quantum mechanical calculations to determine the electronic structure, total DOS, and PDOS. |

| Structure Visualization Software (VESTA, CrystalMaker) | Used to build, visualize, and manipulate atomic models of catalysts and surfaces for input into DFT codes [2]. |

| Post-Processing Codes (pymatgen, VASPKIT) | Scripts and software tools to analyze the output of DFT calculations, extract PDOS, and calculate derived properties like d-band centers. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System | Provides the necessary environment for preparing clean surfaces and performing STM/STS measurements without contamination. |

| STM/STS Instrument | The primary experimental apparatus for obtaining real-space atomic imagery and local electronic density of states spectra [5]. |

| Sputtering Gun (e.g., Ar⁺ Ion Source) | Used in situ within the UHV system to clean crystal surfaces by bombarding them with inert gas ions to remove contaminants. |

The quest for novel catalysts is a cornerstone of advancing sustainable energy and efficient chemical production. A fundamental relationship exists between the electronic structure of a catalyst surface and its chemical reactivity, primarily governed by how strongly intermediate molecules bind to the surface. The density of states (DOS), which describes the distribution of electronic energy levels in a material, serves as a critical link between the atomic structure of a catalyst and its observed catalytic activity. The central thesis of this research is that similarity in DOS profiles can serve as a robust, validated descriptor for predicting catalyst performance, enabling the accelerated discovery of materials with tailored reactive properties. This Application Note provides the theoretical framework, quantitative data, and detailed protocols for using DOS analysis to predict key catalytic descriptors, specifically adsorption energies.

Theoretical Framework: From DOS to Adsorption Energy

The interaction between an adsorbate and a catalyst surface involves a complex rearrangement of electron densities. A pivotal concept is that the strength of this interaction—the adsorption energy ((E{ads}))—is largely determined by the coupling between the adsorbate's molecular orbitals and the electronic states of the surface. Seminal theories, such as the d-band model, posit that the average energy of the d-band electrons ((εd)) in transition metals is a primary descriptor for surface reactivity; a higher (ε_d) typically correlates with stronger adsorption [7].

However, the d-band center is a simplified metric. The full DOS profile contains vastly more information, including the shape, width, and higher moments (skewness, kurtosis) of the d-band, as well as the contribution of other orbitals, all of which influence the bonding and anti-bonding states formed upon adsorption [7]. For instance, the filling of states near the Fermi level is a key factor governing both repulsive and attractive interactions. Machine learning (ML) models that utilize the entire DOS, rather than a single feature, have demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting adsorption energies across a wide range of materials and adsorbates, validating the premise that the complete DOS is a more comprehensive descriptor of reactivity [7] [8].

Table 1: Key Electronic Features Derived from Density of States and Their Influence on Adsorption.

| Electronic Feature | Description | Theoretical Impact on Adsorption |

|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center ((ε_d)) | The first moment (average energy) of the d-band DOS. | A higher (ε_d) generally strengthens adsorption by upshifting anti-bonding states [7]. |

| d-Band Width | The variance or second moment of the d-band DOS. | A wider band leads to greater overlap and hybridization with adsorbate states [7]. |

| d-Band Skewness | The third moment, describing the asymmetry of the DOS. | Influences the relative position and occupancy of bonding vs. anti-bonding states [7]. |

| State Filling | Electron occupation near the Fermi level. | Affects the degree of Pauli repulsion and the stability of the surface-adsorbate bond [7]. |

| Local DOS (LDOS) | DOS projected onto a specific atom or orbital. | Directly determines the mode and strength of local interactions with adsorbates [8]. |

Performance Benchmarking of DOS-Based Prediction Models

The integration of DOS analysis with machine learning has led to the development of powerful predictive models for catalytic properties. These models bypass the need for costly ab initio calculations for every candidate material, enabling high-throughput virtual screening.

DOSnet, a convolutional neural network (CNN) model, automatically extracts relevant features from the orbital-projected DOS of surface atoms to predict adsorption energies [7]. Evaluated on a diverse dataset of 37,000 adsorption energies on bimetallic surfaces, it achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of approximately 0.14 eV across various adsorbates, with hydrogen adsorption predictions as low as 0.071 eV MAE [7].

More recent advancements leverage equivariant graph neural networks (equivGNNs), which enhance atomic structure representation. These models have demonstrated remarkable performance, achieving MAEs below 0.09 eV for binding energies even on highly complex surfaces like high-entropy alloys and supported nanoparticles [9]. This underscores the power of combining electronic structure information with advanced geometric featurization.

For predicting the DOS itself, thereby circumventing DFT calculations, methods using descriptors like the Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) with gradient boosting models (LightGBM, XGBoost) have proven highly effective. These can accurately predict the local DOS of individual atoms in large, multi-element nanoparticles (e.g., >500 atoms) based on training data from smaller systems [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Selected Machine Learning Models for Predicting Catalytic Descriptors.

| Model / Approach | Input Data | Output / Prediction | Reported Performance (MAE) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOSnet [7] | Orbital-projected DOS | Adsorption Energy | ~0.14 eV (avg.); 0.071 eV (H*) | Directly uses electronic structure; physically interpretable. |

| equivGNN [9] | Atomic structure (Graph) | Binding Energy | < 0.09 eV | Universally accurate across simple and complex surfaces. |

| SOAP + GBDT [8] | Atomic structure (SOAP) | Local DOS / Band Center | Closely matches DFT results | Scalable to large nanoalloys; high computational efficiency. |

| GAT (with CN) [9] | Atomic structure (Graph) | M-C Bond Formation Energy | 0.128 eV | Mitigates need for manual feature engineering. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Predicting Adsorption Energy Using a Pre-Trained DOSnet Model

This protocol details the process of using a DOS-based convolutional neural network to predict adsorption energies, as exemplified by the DOSnet architecture [7].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Reagents.

| Item / Software | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | To calculate the electronic DOS of the catalyst surface. | Quantum ESPRESSO [10], VASP |

| ML Framework | To build and train the neural network model. | TensorFlow, PyTorch |

| DOSnet Architecture | A specialized CNN for featurizing DOS data. | As described in [7] |

| Orbital-Projected DOS | The fundamental input feature for the model. | Projected onto s, p, d orbitals of surface atoms. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- System Preparation: Generate the atomic structure of the clean catalyst surface and perform a DFT geometry optimization to obtain its ground-state configuration.

- DOS Calculation: Conduct a single-point DFT calculation on the optimized structure to obtain the electronic structure. Extract the site-projected and orbital-projected DOS for the surface atoms involved in chemisorption (e.g., the three nearest neighbors for a hollow site).

- Data Preprocessing: Format the DOS data as input channels for the network. Each orbital type (s, py, pz, px, dxy, etc.) for each relevant atom constitutes a separate channel. The DOS should be discretized (e.g., at a resolution of 0.01 eV) and normalized.

- Model Application: Feed the preprocessed DOS data into the pre-trained DOSnet model.

- The model employs convolutional layers to automatically identify and extract key features from the DOS shapes across all input channels.

- These features are then passed through fully connected layers to output a numerical prediction of the adsorption energy.

Diagram 1: DOSnet Prediction Workflow.

Protocol 4.2: High-Throughput Screening Using Local DOS (LDOS) Prediction

This protocol describes a scalable approach to predicting the local DOS of large nanoalloy systems using ML models trained on smaller structures, enabling efficient screening [8].

I. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Training Set Construction: Perform DFT calculations on a diverse set of small nanoparticle models (e.g., < 100 atoms) with varying shapes, compositions, and atomic configurations. For each atom in these models, compute its local DOS and its corresponding SOAP descriptor.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., LightGBM or GPR) to map the SOAP descriptors of the atoms to their respective local DOS. The model learns to associate the local atomic environment with its electronic structure.

- Target System Analysis: For a large, target nanoparticle, calculate the SOAP descriptor for every atom in its structure. This is computationally cheap compared to a full DFT DOS calculation.

- LDOS Prediction & Analysis: Use the trained model to predict the LDOS for every atom in the large nanoparticle. The total DOS can be reconstructed by summing all LDOS. Key electronic descriptors, such as local band centers, can be extracted from the predicted LDOS for each unique surface site.

Diagram 2: LDOS Prediction for Large Systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for DOS-Reactvity Studies.

| Category | Item / Software | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Quantum ESPRESSO [10], VASP | Performs first-principles DFT calculations to obtain geometries and electronic DOS. |

| ML Libraries | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Provides frameworks for developing and training deep learning models like DOSnet. |

| Structure Featurization | SOAP Descriptor [8] | Generates a mathematical representation of an atom's local chemical environment. |

| Graph Neural Networks | equivGNN [9] | Creates enhanced atomic structure representations that resolve complex chemical-motif similarities. |

| Data Visualization | Linkurious Enterprise [11], D3.js | Visually explores and investigates complex connected data, such as structure-property relationships. |

In the pursuit of optimizing chemical reactivity and material functionality, researchers increasingly rely on fundamental electronic descriptors to predict and rationalize performance. Among these, frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs)—specifically the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO)—and the d-band center of transition metals have emerged as critical parameters for understanding and designing systems with tailored properties. The HOMO-LUMO gap (Egap) governs molecular reactivity, charge transfer, and optoelectronic behavior, while the d-band center, describing the average energy of d-electron states relative to the Fermi level, serves as a powerful predictor of surface adsorption characteristics and catalytic activity in transition metal-based systems [12] [13]. This Application Note details experimental and computational protocols for employing these descriptors within a research framework focused on validating density of states (DOS) similarity for catalyst performance assessment, providing researchers with standardized methodologies for electronic structure-guided materials discovery.

Theoretical Foundations and Significance of Electronic Descriptors

Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory in Practice

Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) theory posits that the chemical reactivity of a molecule is largely determined by the properties of its HOMO and LUMO. The energy difference between these orbitals, known as the HOMO-LUMO gap (Egap), serves as a crucial indicator of molecular stability and reactivity. A smaller Egap generally correlates with higher chemical reactivity and kinetic instability, as electrons can be more readily excited from HOMO to LUMO [14]. This relationship makes Egap invaluable for designing molecules with specific optoelectronic properties or targeted reactivity.

Quantitatively, the energies of these orbitals directly influence a molecule's nucleophilic and electrophilic character. A higher HOMO energy indicates a greater tendency to donate electrons (nucleophilicity), while a lower LUMO energy suggests a stronger ability to accept electrons (electrophilicity) [12]. This principle was effectively demonstrated in halogenation reactions, where the calculated LUMO energies of N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS, 1.09 eV), dichlorohydantoin (DCH, 0.37 eV), and trichloroisocyanuric acid (TCCA, -0.79 eV) directly correlated with their experimental reactivity as chlorination reagents, with lower LUMO energies corresponding to enhanced electrophilic character [12].

d-Band Center Theory in Transition Metal Systems

For transition metal-based catalysts, the d-band center (εd) serves as an essential electronic descriptor for surface adsorption processes. Originally proposed by Professor Jens K. Nørskov, this theory defines the d-band center as the weighted average energy of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS), typically referenced relative to the Fermi level [13]. The position of this center relative to the Fermi level profoundly influences adsorption strength: a higher εd (closer to the Fermi level) strengthens bonding interactions between catalyst d-orbitals and adsorbate s/p-orbitals, while a lower εd (further below the Fermi level) weakens these interactions by increasing the population of anti-bonding states [13].

This theoretical framework has been extensively generalized beyond pure metals to include alloys, oxides, sulfides, and other complex transition metal systems, becoming indispensable for explaining and predicting catalytic behavior across numerous applications. These include oxygen evolution reaction (OER), carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO₂RR), nitrogen fixation, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), and electrooxidation processes [13]. The broad utility of εd stems from its fundamental connection to the electronic factors governing surface reactivity.

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: HOMO-LUMO Guided Reactivity Assessment for Organic Synthesis

Principle: This protocol utilizes the energy difference between frontier molecular orbitals to predict reaction feasibility and optimize conditions for organic transformations, particularly cyclization reactions [12].

Experimental Workflow:

- Computational Modeling: Optimize the ground-state geometry of reaction intermediates using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the B3LYP functional and 6-311++G(d,p) basis set [15].

- Orbital Calculation: Calculate the HOMO and LUMO energies from the optimized structures. Identify orbitals with lobe distributions at the predicted reaction sites. If the primary HOMO/LUMO lack appropriate distribution, examine HOMO-1/HOMO-2 or LUMO+1/LUMO+2 orbitals.

- Energy Gap Calculation: Determine the HOMO-LUMO energy gap (ΔEL-H) as ΔEL-H = ELUMO - EHOMO.

- Reactivity Prediction: Correlate the calculated energy gap with experimental feasibility. For Pictet-Spengler reactions, gaps below approximately 9.09 eV typically proceed, while larger gaps may require stronger acids, higher temperatures, or may not proceed under standard conditions [12].

- Acidity Consideration: For substrates containing basic nitrogen atoms, calculate the HOMO-LUMO energy gap of the protonated species, as protonation under acidic conditions can significantly alter the orbital energy gap and thus the reaction outcome.

Table 1: HOMO-LUMO Energy Gaps and Reactivity in Pictet-Spengler Reaction [12]

| Substrate Analogue | HOMO Energy (eV) | LUMO Energy (eV) | ΔEL-H (eV) | Reactivity Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indole (Reactive) | -5.90 | -2.20 | 8.10 | Proceeds with TFA, 60°C |

| Pyrazole (9) | -6.74 | -2.35 | 9.09 | Threshold of reactivity |

| Phenyl (10) | -6.41 | -2.32 | 9.09 | No reaction under conditions studied |

| 5-Azaindole (11) | -5.38 | -2.00 | 8.38 | Predicted to proceed, but no reaction observed |

| 5-Azaindole (11+H⁺) | -7.12 | -2.99 | 10.11 | No reaction (protonation explains failure) |

| 12 (MeO-substituted) | -5.33 | -2.40 | 7.93 | Successfully synthesized |

| 13 (Cl-substituted) | -5.65 | -2.88 | 8.53 | Successfully synthesized |

Protocol 2: Density of States Similarity Screening for Bimetallic Catalysts

Principle: This protocol accelerates the discovery of bimetallic catalysts by using the similarity of their full electronic Density of States (DOS) pattern to a known reference catalyst (e.g., Pd) as a primary screening descriptor, hypothesizing that similar electronic structures yield comparable catalytic properties [16].

Computational Workflow:

- High-Throughput DFT Calculation: For a large library of candidate bimetallic structures (e.g., 4350 alloy structures across 10 ordered phases), perform DFT calculations to determine formation energy (ΔEf) and project the DOS of the most stable close-packed surface (e.g., (111) facet).

- Thermodynamic Screening: Filter candidates based on thermodynamic stability (ΔEf < 0.1 eV) to ensure synthetic feasibility and operational stability, identifying miscible alloys.

- DOS Similarity Quantification: For thermodynamically stable candidates, calculate the DOS similarity (ΔDOS2-1) relative to the reference catalyst (e.g., Pd(111)) using a Gaussian-weighted difference metric [16]: ΔDOS2-1 = { ∫ [ DOS2(E) - DOS1(E) ]² g(E;σ) dE }^½ where g(E;σ) is a Gaussian function centered at the Fermi level (EF) with standard deviation σ (e.g., 7 eV) to emphasize states near EF.

- Candidate Selection: Identify top candidates exhibiting the lowest ΔDOS2-1 values, indicating the highest electronic structure similarity to the reference.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the screened candidates and evaluate their performance for the target reaction (e.g., H2O2 direct synthesis) to validate the predictive power of the DOS similarity descriptor.

Table 2: DOS Similarity Screening Results for Pd-like Bimetallic Catalysts [16]

| Bimetallic Catalyst | Crystal Structure | ΔDOS2-1 (Similarity Metric) | Experimental H₂O₂ Synthesis Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | B2 | Low (High Similarity) | Comparable to Pd, 9.5x cost-normalized productivity |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | N/A | Low (High Similarity) | Comparable to Pd |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | N/A | Low (High Similarity) | Comparable to Pd |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | N/A | Low (High Similarity) | Comparable to Pd |

| CrRh | B2 | 1.97 | Candidate (Performance not specified) |

| FeCo | B2 | 1.63 | Candidate (Performance not specified) |

Advanced Applications and Machine Learning Integration

Inverse Design of Materials with Target d-Band Centers

The dBandDiff model represents a cutting-edge application of diffusion-based generative models for the inverse design of crystal structures conditioned on target d-band center values and space group symmetry [13]. This approach addresses the limitations of traditional high-throughput screening and regression models by directly generating novel crystal structures with pre-specified electronic properties.

Methodology: The model uses a periodic feature-enhanced graph neural network (GNN) as a denoiser within a Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) framework. It incorporates space group constraints during both noise initialization and reconstruction to ensure generated structures adhere to symmetry requirements [13]. The model is trained end-to-end to learn the mapping between conditional inputs (d-band center, space group) and physically plausible crystal structures.

Performance: When tasked with generating structures with a target d-band center of 0 eV, dBandDiff identified 17 theoretically reasonable compounds within an error margin of ±0.25 eV from only 90 generated candidates. High-throughput DFT validation confirmed that 72.8% of generated structures were geometrically and energetically reasonable, demonstrating significantly higher accuracy compared to random generation [13].

Machine Learning for Spectral Property Prediction

Machine learning frameworks like Mat2Spec (Materials-to-Spectrum) enable the prediction of fundamental spectral properties, including phonon density of states (phDOS) and electronic density of states (eDOS), directly from crystal structures [6]. This capability is vital for high-throughput screening of electronic properties relevant to catalysis and materials science.

Architecture: Mat2Spec employs a graph attention network for encoding crystalline materials, coupled with a probabilistic embedding generator based on multivariate Gaussians and supervised contrastive learning. This design explicitly captures relationships between different points in the spectrum, outperforming state-of-the-art methods for predicting ab initio phDOS and eDOS [6].

Application: The model successfully identified eDOS gaps below the Fermi energy in metallic systems, validating predictions with ab initio calculations to discover candidate materials for thermoelectrics and transparent conductors [6].

Electronic Structure-Infused Networks for Molecular Property Prediction

For organic molecules, the Electronic Structure-Infused Network (ESIN) integrates frontier molecular orbital information directly into deep learning models for predicting excited-state properties critical to functionality, such as photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) emitters [17].

Strategy: ESIN uses a "frontier molecular orbitals weight-based representation and modeling" feature, where atoms with the largest contributions to HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO+1 are selected as topological centers. A Chemical Groups-Based Sampling and Aggregate (CGB-SAGE) method then generates local representations of molecular orbitals, integrating both FMO information and 3D coordinate relationships [17]. This approach provides an interpretable model that associates critical structural elements with target properties.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Perform DFT calculations for geometry optimization and electronic structure analysis. | Software packages implementing B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) for molecules; VASP for periodic systems [15] [13]. |

| Halogenation Reagents | Experimental reagents with calibrated electrophilic strength based on LUMO energy. | NCS (ELUMO = 1.09 eV), DCH (ELUMO = 0.37 eV), TCCA (ELUMO = -0.79 eV) [12]. |

| Materials Databases | Source of crystal structures and calculated properties for training and validation. | Materials Project database providing DFT-calculated structures and DOS data [13] [6]. |

| Descriptor-Based Screening Models | High-throughput identification of candidate materials based on electronic similarity. | DOS similarity screening (ΔDOS2-1) [16]; d-band center conditioned generative models (dBandDiff) [13]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Machine learning architecture for learning structure-property relationships in molecules and materials. | Used in CGCNN, MEGNet, GATGNN, Mat2Spec, and ESIN for property prediction [6] [17]. |

The integration of frontier molecular orbital and d-band center analysis provides a robust framework for understanding and predicting chemical reactivity and catalytic performance. The protocols outlined herein—from HOMO-LUMO guided organic synthesis to DOS similarity screening for bimetallic catalysts—offer researchers standardized methodologies for leveraging these electronic descriptors in materials design and discovery. The emerging integration of these fundamental principles with advanced machine learning models, such as generative networks and electronic structure-infused neural networks, heralds a new paradigm in inverse materials design. These approaches enable the targeted discovery of materials with predefined electronic characteristics, substantially accelerating the development of next-generation catalysts and functional materials while validating the critical role of density of states similarity in governing functional performance.

Electronic Metal-Support Interactions (EMSI) represent a cornerstone concept in heterogeneous catalysis, describing the electronic interplay between metal nanoparticles or single atoms and their supporting materials. These interactions induce charge transfer at the metal-support interface, leading to modifications in the electronic structure of the active metal sites [18] [19]. A critical manifestation of EMSI is its direct influence on the local density of states (LDOS), which determines the availability of electronic states at specific energy levels. The LDOS serves as a fundamental descriptor for catalytic activity, as it governs the adsorption strengths of key reaction intermediates and the energy barriers for catalytic steps [8]. This case study, framed within a broader thesis validating density of states similarity for catalyst performance research, provides a detailed analysis of how EMSI modulates the DOS to enhance catalytic processes. We present quantitative data, detailed protocols for probing these effects, and essential tools for researchers in the field.

Quantitative Data on EMSI and Catalytic Performance

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies on EMSI, highlighting the correlation between electronic structure modifications and catalytic performance.

Table 1: Charge Transfer and Catalytic Activity in Supported Ni Clusters for Ethylene Hydrogenation [18]

| Catalyst System | Charge State of Ni Cluster | H₂ Adsorption Energy (eV) | C₂H₄ Adsorption Energy (eV) | Activation Energy (Low H coverage, eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₄/BNO | Lowest positive charge | -0.45 | -1.32 | 0.75 |

| Ni₄/CeO₂ | Intermediate positive charge | -0.39 | -1.25 | 0.85 |

| Ni₄/TiO₂ | Highest positive charge | -0.35 | -1.18 | 0.95 |

Table 2: EMSI-Enhanced Electro-oxidation Performance for Wastewater Purification [20]

| Anode Material | Steady-State •OH Concentration Increase (Fold) | Pseudo-First-Order Rate Constant for SMX Degradation (min⁻¹) | Charge Transfer Resistance (Rct) | OER Overpotential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bare ATO | Baseline | ~0.01 k' | High | High |

| Ni/ATO (with EMSI) | >5 | ~0.10 k' (10-fold enhancement) | Minimal | Moderate |

Table 3: Valence Restrictive MSI in Rh/CeO₂ for CO₂ Hydrogenation [19]

| Catalyst Structure | Average Oxidation State of Rh | H Adsorption Energy (eV) | Preferred Reaction Intermediate | Main Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh₁-CeO₂ (Single Atom) | Rh³⁺ | ~0.10 eV (at Rh site) | COOH* | CO |

| Rhₙ/CeO₂ (Small Cluster, n=3) | Rh²⁺ (average) | -1.23 eV | HCOO* | CH₄ |

| Rh₂₂/CeO₂ (Large Cluster) | Metallic (low charge) | ~ -0.44 eV | - | - |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Probing EMSI via DFT Calculations and DOS Analysis

This protocol details a computational approach to quantify EMSI and its electronic effects, foundational for validating DOS similarity.

1. System Modeling:

- Model Construction: Build atomic models of the support surfaces (e.g., CeO₂(111), TiO₂(101), 2D materials like BNO) and the metal clusters (e.g., Ni₄, Rhₙ) [18] [19].

- Geometry Optimization: Perform full relaxation of the supported catalyst model using DFT with van der Waals corrections (e.g., DFT-D3) to obtain the stable adsorption structure [18].

2. Electronic Structure Analysis:

- Bader Charge Analysis: Quantify the net charge transfer between the metal cluster and the support to determine the charge state of the metal [18] [19].

- Density of States (DOS) Calculation: Calculate the projected density of states (PDOS) for the metal

d-orbitals in the supported system and compare it to the PDOS of an isolated metal cluster. - Key Observation: A shift in the

d-band center of the metal and changes in the intensity of specific electronic states near the Fermi level are direct manifestations of EMSI [8].

3. Correlation with Catalytic Activity:

- Adsorption Energy Calculations: Compute the adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates (e.g., C₂H₄, H, COOH) on the supported metal cluster [18] [19].

- Energy Barrier Calculations: Use the nudged elastic band (NEB) method to determine the activation energies for the rate-limiting steps of the target reaction (e.g., hydrogenation) [18].

- Descriptor Validation: Correlate the calculated charge states and

d-band features (from DOS) with the adsorption energies and activation barriers to establish the DOS-activity relationship [18] [8].

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation using Operando XPS

This protocol describes an experimental procedure to directly measure the electronic states of metal sites under working conditions, providing critical validation for computational predictions.

1. Catalyst Synthesis and Preparation:

- Synthesis: Prepare the supported catalyst (e.g., Pt/CeO₂, Ni/ATO) using methods such as wet impregnation, precipitation, or magnetron sputtering to achieve well-dispersed metal species [20] [21].

- Calibration: Introduce the catalyst powder into the operando Ambient Pressure XPS (AP-XPS) system and establish a base line at room temperature under ultra-high vacuum (UHV).

2. Operando Measurement:

- Reaction Conditions: Introduce the reactant gas mixture (e.g., 0.1 mbar CO + 0.3 mbar H₂O for WGS) to the analysis chamber [21].

- Data Acquisition:

- Temperature Program: Heat the catalyst in steps (e.g., 100°C, 250°C, 300°C) under the reaction gas mixture.

- Spectral Collection: At each temperature, collect high-resolution XPS spectra for the metal core levels (e.g., Pt 4f, Ni 2p) and support elements (e.g., Ce 3d, O 1s) [21].

3. Data Analysis:

- Peak Deconvolution: Fit the metal core-level spectra with multiple components assigned to different species (e.g., metallic Pt⁰ in bulk, terraces, corners; ionic Pt²⁺ single atoms) based on their binding energies (BE) [21].

- Electronic State Monitoring: Track the evolution of these species' concentrations with temperature. A decrease in ionic species BE and an increase in metallic species BE indicates cluster formation and electron transfer due to EMSI [21].

- Correlation with Activity: Simultaneously monitor reaction products (e.g., H₂) via mass spectrometry and correlate the appearance of specific metal electronic states with catalytic activity [21].

Protocol 3: Machine Learning for High-Throughput DOS Prediction

This protocol leverages machine learning (ML) to predict the DOS of complex catalytic systems, enabling rapid screening and validation of EMSI effects.

1. Data Set Preparation:

- DFT Calculations: Generate a diverse dataset of atomic structures (e.g., nanoparticles, alloys, supported clusters) and their corresponding electronic DOS using DFT. This serves as the training data [8] [22].

- Feature Extraction: For each atom in a structure, compute a descriptor that encodes its local chemical environment. The Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) descriptor is highly effective for this purpose [8].

2. Model Training and Validation:

- Model Selection: Train machine learning models (e.g., LightGBM, XGBoost, Gaussian Process Regression, or Equivariant Graph Neural Networks) to map the SOAP descriptors of all atoms in a structure to the total or local DOS [8] [22].

- Validation: Assess model performance on a held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for DOS prediction and band gap accuracy [8] [22].

3. Prediction and Screening:

- Deployment: Use the trained ML model to predict the DOS for new, unknown catalyst structures at a fraction of the computational cost of DFT.

- Analysis: Use the predicted DOS to derive electronic descriptors (e.g.,

d-band center) and statistically evaluate the local electronic variations across complex materials like high-entropy alloys to identify promising candidates driven by EMSI [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMSI and DOS Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Source of active metal component for catalyst synthesis. | Rh chloride (Rh/CeO₂) [19], Ni salts (Ni/ATO) [20], Pt salts (Pt/CeO₂) [21]. |

| Oxide Supports | Provide anchoring sites for metal species, induce EMSI. | CeO₂ (111) facet [18] [19] [21], TiO₂ (anatase, 101) [18], Antimony-doped Tin Oxide (ATO) [20]. |

| 2D Material Supports | Model supports with tunable electronic properties. | Boron Nitride doped with Oxygen (BNO) [18], MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) [23]. |

| DFT Software | Computational modeling of structure, electronic properties, and reaction pathways. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO; Used for geometry optimization, DOS, and Bader charge analysis [18] [19]. |

| SOAP Descriptor | Machine learning feature describing local atomic environments. | Critical for building accurate ML models to predict DOS and other electronic properties [8]. |

| Operando AP-XPS | In-situ characterization of electronic states under reaction conditions. | Identifies metal oxidation states (Pt⁰, Pt²⁺) and charge transfer in working catalysts [21]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Machine learning architecture for learning from graph-structured data (atoms=bonds). | Equivariant GNNs, PET-MAD-DOS model; Achieves high accuracy in predicting DOS for complex systems [9] [22]. |

A Practical Workflow: Calculating and Comparing DOS for Catalyst Screening

In computational catalysis research, the Density of States (DOS) serves as a fundamental electronic structure descriptor that provides deep insights into a material's catalytic properties. For transition metal catalysts, the projected DOS (pDOS), particularly the d-band model, has long been established as a powerful predictor of surface reactivity and adsorption behavior. More recently, DOS similarity analysis has emerged as a robust descriptor for high-throughput catalyst discovery, enabling researchers to identify novel catalytic materials that mimic the electronic structures of known high-performance catalysts.

The accuracy of DOS calculations depends critically on the chosen computational parameters, primarily the exchange-correlation functional and basis set (or pseudopotential). These choices introduce varying levels of uncertainty that must be understood and managed, especially when DOS comparisons form the basis for predicting catalytic performance. This Application Note provides a structured framework for selecting and validating these computational tools to ensure reliable DOS similarity assessments in catalyst research.

Core Concepts: DFT Fundamentals for DOS Calculations

The Physical Significance of DOS in Catalysis

The DOS represents the number of electronic states per unit energy at each energy level, with the projected DOS (pDOS) decomposing this information by atomic orbital contributions. In catalytic systems, key features of the DOS—particularly near the Fermi energy (EF)—directly influence an adsorbate's binding strength through coupling with metal states. The d-band center, a weighted average of the d-states relative to EF, has proven exceptionally successful in predicting adsorption energies and catalytic activity trends across transition metal surfaces.

Recent advances have leveraged full DOS pattern matching as a screening descriptor, operating on the principle that materials with similar electronic structures exhibit similar catalytic properties. This approach successfully identified bimetallic catalysts (e.g., Ni-Pt) with performance comparable to Pd for H₂O₂ synthesis by quantifying DOS pattern similarity using a Gaussian-weighted difference metric [16].

Critical Computational Considerations

Several computational factors significantly impact the accuracy and reliability of calculated DOS:

- Self-interaction error: Spurious electron self-repulsion that artificially delocalizes states

- Exchange-correlation treatment: Approximations for quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects

- Basis set completeness: The flexibility of mathematical functions describing electron orbitals

- Pseudopotential accuracy: The treatment of core-valence electron interactions

- k-point sampling: Density of points used to sample the Brillouin Zone for periodic systems

Each factor can systematically shift DOS features, particularly the positions and shapes of crucial d-band states near the Fermi level, potentially affecting catalytic activity predictions.

Quantitative Comparison of Computational Methods

Table 1: Performance of Exchange-Correlation Functionals for DOS-Related Properties

| Functional | Class | Strengths | Limitations | Recommended Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | Computational efficiency; reasonable lattice parameters | Band gap underestimation; delocalization error | Compare d-band center to RPBE/BEEF-vdW |

| PBE+U | GGA+U | Improved d/f-electron localization; better band gaps | U parameter selection critical | Validate U value against experimental band structure [24] |

| RPBE | GGA | Improved adsorption energies over PBE | Similar delocalization issues as PBE | Benchmark against hybrid functionals for adsorption [25] |

| BEEF-vdW | GGA+vdW | Superior adsorption energetics; error estimation | Increased computational cost | Use built-in ensemble error analysis [25] |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | Accurate band gaps; improved electronic structure | High computational cost | Reserve for final validation of promising candidates |

Table 2: Basis Set and Pseudopotential Selection Guide

| Type | Description | Applications | Convergence Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave | Basis of plane waves with kinetic energy cutoff | Periodic systems (surfaces, bulk); most surface catalysis | Cutoff energy (typically 400-600 eV); pseudopotential compatibility |

| PAW | Projector Augmented-Wave pseudopotentials | Accurate core-valence interactions; all-electron properties | Cutoff energy; projector completeness; specifically treat d-electrons in transition metals [24] |

| Norm-Conserving | Strict electron density conservation | Rapid calculations; molecular systems | Higher cutoff requirements than PAW |

| Ultrasoft | Reduced plane-wave requirements | Faster structure optimizations | Potential accuracy loss for electronic properties |

Experimental Protocols for DOS Validation

Protocol: DOS Similarity Assessment for Catalyst Screening

This protocol outlines the methodology for using DOS similarity to identify novel bimetallic catalysts, based on the high-throughput screening approach demonstrated by [16].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DOS Calculations

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | Electronic structure calculation | Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, GPAW |

| Structure Database | Initial catalyst models | Materials Project, OQMD, Catalysis-Hub.org [25] |

| Post-Processing Tools | DOS similarity analysis | Custom Python scripts with NumPy/SciPy |

| Validation Database | Experimental benchmark data | Catalysis-Hub.org Surface Reactions database [25] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reference Catalyst Selection

- Choose a reference catalyst with known high performance for the target reaction

- Calculate the reference DOS using optimized computational parameters

- For Pd-like catalysts, use Pd(111) surface as reference [16]

High-Throughput Screening Calculations

- Generate candidate catalyst structures (e.g., 4350 bimetallic alloys [16])

- Perform thermodynamic stability screening: discard structures with ΔEf > 0.1 eV

- For stable structures, calculate surface DOS using consistent parameters:

- Plane-wave cutoff: 400-550 eV (convergence tested)

- k-point sampling: Γ-centered grid appropriate for surface slab

- Pseudopotentials: PAW method with consistent treatment of valence electrons

DOS Similarity Quantification

- Extract total DOS including both d-states and sp-states

- Calculate similarity metric using Gaussian-weighted difference:

- Set σ = 7 eV to emphasize the energy range near E_F where most d-states reside [16]

Experimental Validation

- Synthesize top candidate materials (lowest ΔDOS values)

- Evaluate catalytic performance for target reaction

- Compare to reference catalyst performance

Protocol: Functional and Basis Set Benchmarking

This protocol provides a systematic approach for validating computational parameters against known experimental or high-level computational data.

Materials

- Reference systems with well-characterized electronic structure (e.g., Cu(111), Pt(111))

- Test set of adsorption energies from Catalysis-Hub.org [25]

- Multiple exchange-correlation functionals (PBE, PBE+U, RPBE, BEEF-vdW)

- Multiple pseudopotential types (PAW, norm-conserving)

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Selection

- Choose benchmark systems with reliable experimental or high-level computational data

- Include diverse chemical environments (metals, oxides, adsorbates)

Parameter Testing

- Calculate DOS for each system with multiple functionals and basis sets

- Compare key electronic properties: d-band center, band gap, Fermi energy

- Compute adsorption energies for probe molecules (CO, O, H)

Error Quantification

- Calculate mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) relative to reference

- Assess systematic biases (e.g., consistent over/under-binding)

Protocol Establishment

- Select functional/basis set combination that minimizes error within computational constraints

- Document expected error ranges for future predictions

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for DOS similarity-based catalyst discovery, integrating parameter validation and experimental verification.

Advanced Approaches and Future Directions

Embedding Methods for Metallic Systems

For challenging systems where standard DFT approaches suffer from delocalization errors, embedding methods offer a promising alternative. Projection-based embedding theory (PBET) enables high-level treatment of active sites while embedding them in a periodic DFT environment. Key requirements for metallic systems include:

- Consistent active orbital space maintained across reaction coordinates

- Fraction of exact exchange in nonadditive exchange-correlation functional to mitigate delocalization

- SPADE algorithm for appropriate system partitioning that preserves delocalized nature of metallic states [26]

Machine Learning Accelerated Workflows

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) are increasingly capable of reproducing DFT-quality adsorption energies at significantly reduced computational cost. The CatBench framework provides systematic benchmarking of MLIPs, with best models achieving ~0.2 eV accuracy for adsorption energy predictions [27]. These tools enable rapid screening of vast material spaces while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy.

Accurate DOS calculations form the foundation for reliable catalyst discovery through electronic structure similarity analysis. The choice of exchange-correlation functional and basis set/pseudopotential must be guided by systematic validation against experimental data or high-level computations. PBE+U often provides improved treatment of transition metal d-states, while hybrid functionals offer higher accuracy at increased computational cost. Emerging methodologies including quantum embedding and machine learning potentials promise to further enhance the accuracy and efficiency of computational catalyst screening. By adopting the standardized protocols and benchmarking approaches outlined in this Application Note, researchers can establish validated computational workflows for DOS-driven catalyst discovery with well-characterized uncertainty bounds.

The Density of States (DOS) is a fundamental concept in computational materials science, describing the number of electronic states available at each energy level within a material. In the context of catalyst research, analyzing the DOS provides crucial insights into the electronic structure that governs catalytic activity, stability, and selectivity. For researchers validating density of states similarity for catalyst performance, DOS analysis serves as a bridge between a catalyst's atomic structure and its macroscopic functionality. Particularly in the study of transition metal catalysts and perovskite materials, the DOS reveals key features such as d-band center position, band gaps, and orbital hybridization effects that directly influence adsorption energies and reaction pathways [28] [29].

The integration of DOS analysis with machine learning approaches has further enhanced its predictive power for catalytic properties, enabling high-throughput screening of novel materials without exhaustive experimental testing [7]. This protocol details the comprehensive workflow for generating and analyzing DOS profiles, with specific application to catalyst validation studies.

Theoretical Background and Significance

Fundamental Principles of DOS

The DOS, denoted as g(E), represents the number of electronic states per unit volume per unit energy. In catalytic materials, the region near the Fermi level (E_F) is of particular importance as it governs electron transfer during chemical reactions. The projected density of states (PDOS) further decomposes this information into contributions from specific atoms, orbitals, or angular momentum components, enabling researchers to identify which electronic states are responsible for catalytic behavior [30].

For transition metal-based catalysts, the d-band model has proven exceptionally valuable in understanding adsorption strength of reaction intermediates. According to this model, the position of the d-band center (ε_d) relative to the Fermi level correlates with adsorption energies - a central relationship in catalyst design [29]. The d-band center represents the first moment of the d-band DOS, but higher moments including d-band width, skewness, and kurtosis provide additional dimensions for understanding electronic structure-property relationships [29].

DOS Similarity Metrics for Catalyst Validation

In validation studies of density of states similarity for catalyst performance, researchers employ both qualitative comparison and quantitative metrics. The similarity between two DOS spectra (ρ₁ and ρ₂) can be quantified using functions that calculate the difference between spectra according to the formula:

Δρ = (1/N) × Σ|ρ₁ᵢ - ρ₂ᵢ|

where N denotes the number of data points in the spectra and ρ₁ᵢ and ρ₂ᵢ are the i-th data points in the spectra [29]. These similarity descriptors, when correlated with catalytic performance metrics, enable the identification of electronic structure descriptors that predict catalyst efficiency across diverse materials spaces.

Computational Methodology for DOS Generation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for generating and analyzing DOS profiles in catalyst research:

Initial DFT Setup and Self-Consistent Field Calculation

The first step in DOS generation involves obtaining converged self-consistent charges through Density Functional Theory calculations. This requires careful attention to k-point sampling and convergence criteria to ensure accurate representation of the electronic structure [30].

Protocol: SCF Calculation for DOS

- Geometry Optimization: Begin with a fully optimized crystal structure. For surface calculations, ensure sufficient vacuum spacing (typically ≥15 Å) to prevent periodic interactions [29].

- K-point Grid Selection: Use a Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid of sufficient density. For accurate DOS calculations, an 8×8×8 grid or equivalent is typically required for bulk materials, while surfaces may require adjusted sampling [30].

- Convergence Parameters: Set the SCF tolerance to at least 1e-5 eV for energy convergence. For DOS-specific calculations, use a finer k-point mesh along high-symmetry directions [30].

- Electronic Structure Method: Employ the PBE functional or hybrid alternatives depending on accuracy requirements. Use Gaussian smearing (0.2 eV) or tetrahedron method for Brillouin zone integration [29].

Table 1: Key DFT Parameters for DOS Calculations

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-point Grid | 8×8×8 for bulk | Brillouin zone sampling | Test convergence with denser grids |

| SCF Tolerance | 1e-5 eV | Charge convergence | Tighter tolerance (1e-6 eV) for metallic systems |

| Energy Cutoff | 520 eV for PAW pseudopotentials | Plane-wave basis | Increase for harder pseudopotentials |

| Smearing | Gaussian, 0.2 eV | Partial occupancies | Methfessel-Paxton for metals |

| Functional | PBE | Exchange-correlation | HSE06 for improved band gaps |

DOS Calculation and Band Structure Analysis

After obtaining converged charges, the DOS can be calculated along specific k-point paths to generate band structure information [30].

Protocol: DOS and Band Structure Calculation

- Fixed Charge Calculation: Use the converged charge density from the SCF calculation with

ReadInitialCharges = YesandMaxSCCIterations = 1to calculate eigenvalues along high-symmetry paths without recalculating charges [30]. - K-path Selection: Define a k-path through high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone. For example, in anatase TiO₂, use the path Z-Γ-X-P for comprehensive band structure analysis [30].

- DOS Smearing: Apply Gaussian smearing with appropriate width (typically 0.1-0.2 eV) to the calculated eigenvalues to generate continuous DOS profiles [31].

- Projected DOS Setup: Specify atoms and orbitals for PDOS calculation to decompose contributions by atomic species and orbital type [30].

DOS Analysis Techniques

Feature Extraction from DOS Profiles

Protocol: Electronic Feature Identification

- Band Gap Determination: Identify the energy difference between the highest occupied state (valence band maximum) and lowest unoccupied state (conduction band minimum) [28].

- d-Band Descriptors Calculation: Compute moments of the d-band DOS for transition metal catalysts [29]:

- d-band center (ε_d): First moment of d-band DOS

- d-band width: Second moment representing bandwidth

- d-band skewness: Third moment indicating asymmetry

- d-band kurtosis: Fourth moment describing peakedness

- Fermi Level Analysis: Examine DOS at the Fermi level to characterize metallic vs. insulating behavior.

- Orbital Hybridization: Identify regions of overlapping PDOS from different elements that indicate chemical bonding.

Table 2: Key Electronic Descriptors from DOS Analysis

| Descriptor | Calculation Method | Catalytic Significance | Reference Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Gap | Energy between VBM and CBM | Optical activity, conductivity | 2.6 eV for RbPbCl₃ [28] |

| d-Band Center (ε_d) | First moment of d-band DOS | Adsorption strength | Pt(111): ~ -2.0 eV [29] |

| d-Band Width | Second moment of d-band DOS | Orbital delocalization | Element-dependent [29] |

| d-Band Skewness | Third moment of d-band DOS | Distribution asymmetry | Positive for early transition metals [29] |

| Upper d-Band Edge | Highest peak of Hilbert-transformed DOS | Anti-bonding state position | Correlates with adsorption [29] |

PDOS Analysis and Orbital Decomposition

Protocol: Projected DOS Analysis

- Atomic Projection: Calculate PDOS for each relevant atomic species in the catalyst. For example, in TiO₂, separate Ti and O contributions [30].

- Orbital Resolution: Resolve PDOS by angular momentum (s, p, d orbitals) to identify orbital-specific contributions to catalytic activity.

- Surface Atom Focus: Prioritize analysis on surface atoms where catalysis occurs, as their electronic structure often differs from bulk atoms.

- Comparison Strategy: Compare PDOS of candidate catalysts with known reference materials (e.g., Pt(111)) to identify electronic similarity [29].

Validation of DOS Similarity for Catalyst Performance

DOS Similarity Metrics

Protocol: Quantitative DOS Similarity Assessment

- Descriptor-Based Similarity: Calculate similarity in key electronic descriptors (d-band center, width, etc.) between reference and candidate catalysts [29].

- Full-Spectrum Comparison: Implement similarity functions that compare entire DOS profiles rather than reduced descriptors:

- Use Δρ = (1/N) × Σ|ρ₁ᵢ - ρ₂ᵢ| for discrete DOS comparison

- Consider cross-correlation methods for shape similarity

- Machine Learning Approaches: Employ convolutional neural networks (e.g., DOSnet) to automatically extract relevant features from DOS for adsorption energy prediction [7].

- Performance Correlation: Establish correlation between DOS similarity metrics and experimental catalytic performance measurements.

Stability and Practical Implementation Analysis

Protocol: Stability Assessment from DOS

- Formation Energy Calculation: Compute energy above hull to assess synthetic accessibility [29].

- Pourbaix Diagram Construction: Evaluate aqueous stability under operational conditions to identify stable catalyst compositions [29].

- Decomposition Energy: Determine energy released when decomposing into ground states under reaction conditions [29].

- Electronic Stability Indicators: Identify DOS features correlated with stability, such as band gap magnitude and Fermi level position relative to band edges.

Implementation Tools and Visualization

Computational Tools for DOS Analysis

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DOS Analysis

| Tool/Software | Function | Application in DOS Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DFTB+ | DFTB-based electronic structure | Band structure, DOS and PDOS calculation [30] |

| VASP | DFT calculations | High-throughput DOS screening [29] |

| ASE | Atomistic simulation environment | DOS analysis and moment calculation [31] |

| dp_dos | DOS processing | Converting eigenvalues to plottable DOS [30] |

| Pymatgen | Materials analysis | DOS similarity and comparison [29] |

DOS Visualization and Interpretation

Protocol: Effective DOS Visualization

- Plot Generation: Use tools like

dp_dosto process eigenlevels and generate plottable DOS data with appropriate smearing [30]. - Comparative Visualization: Plot total DOS alongside PDOS components to identify contributions to catalytic activity.

- Reference Highlighting: Include DOS of reference catalysts (e.g., Pt(111)) for direct comparison with candidate materials.

- Fermi Level Alignment: Align all DOS plots at the Fermi level (set to 0 eV) for consistent energy reference.

The following diagram illustrates the DOS similarity validation workflow for catalyst discovery:

Application in Catalyst Discovery

Case Study: Intermetallic Catalyst Screening

A recent study demonstrated the application of DOS analysis in screening 2,358 binary and ternary intermetallic compounds for hydrogen evolution (HER) and oxygen reduction (ORR) reactions [29]. The methodology included:

- High-Throughput DOS Calculation: Generation of 12,057 surface slabs with DFT-calculated DOS profiles

- Descriptor-Based Filtering: Application of seven electronic-structure-based descriptors to identify promising catalysts

- Stability Assessment: Construction of Pourbaix diagrams to evaluate aqueous stability

- Validation: Identification of both known and new intermetallic catalysts with reduced noble metal content

This approach successfully identified catalysts with electronic structures similar to benchmark Pt(111) and Ir(111) surfaces while minimizing noble metal content, demonstrating the power of DOS similarity analysis in catalyst design [29].

Machine Learning Integration

The DOSnet framework exemplifies advanced DOS analysis, where convolutional neural networks automatically extract relevant features from DOS for adsorption energy prediction [7]. This approach:

- Achieved mean absolute errors of ~0.1 eV for adsorption energies across diverse adsorbates and surfaces

- Eliminated the need for manual descriptor selection

- Provided physical insights by predicting responses to external perturbations in electronic structure

- Demonstrated applicability across a wide range of chemical environments

This integration of DOS analysis with machine learning represents the cutting edge in computational catalyst discovery, enabling rapid screening of materials based on electronic structure similarity to known high-performance catalysts.

The electronic Density of States (DOS) has emerged as a powerful descriptor for predicting the properties of solid-state materials, particularly in the field of catalysis. The core thesis is that materials with similar electronic structures are likely to exhibit similar chemical properties [16]. This application note details the quantitative metrics and experimental protocols for validating DOS similarity to accelerate the discovery of novel catalysts, enabling researchers to identify promising candidates with performance comparable to known noble metals while reducing reliance on costly elements.

Quantitative Metrics for DOS Similarity

Quantifying the similarity between two DOS spectra requires moving beyond qualitative comparison to robust numerical metrics. The table below summarizes the primary metrics developed for this purpose.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying DOS Similarity

| Metric Name | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Primary Application | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔDOS (Euclidean-based) [16] | ΔDOS₂₋₁ = { ∫ [DOS₂(E) - DOS₁(E)]² · g(E;σ) dE }^{½} |

σ (width of Gaussian weighting function, e.g., 7 eV) |

High-throughput screening of bulk alloy surfaces; identifying Pd-like catalysts. | ||||

| Tanimoto Coefficient [32] | `Tc(fᵢ, fⱼ) = (fᵢ · fⱼ) / ( | fᵢ | ² + | fⱼ | ² - fᵢ · fⱼ)` | Binary fingerprint vectors (fᵢ, fⱼ) derived from DOS. |

Unsupervised learning and clustering of materials databases (e.g., 2D materials). |

| DOS-Similarity Descriptor [29] | `Δρ = (1/N) Σ | ρ₁ᵢ - ρ₂ᵢ | ` | Total DOS (ρ₁) and valence DOS (ρ₂) spectra. |

Assessing resemblance between different projections of the DOS. |

Metric Selection and Interpretation

- ΔDOS (Euclidean-based): This metric is particularly valuable for focused catalyst screening. The Gaussian function

g(E;σ)weights the region near the Fermi level more heavily, which is often critical for catalytic activity. A value approaching 0 indicates high similarity, and a threshold (e.g., ΔDOS < 2.0) can be set for candidate selection [16]. - Tanimoto Coefficient (Tc): Ideal for exploratory data analysis of large materials databases. The Tc ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates identical DOS fingerprints. This method is highly effective for grouping materials into clusters with similar electronic properties [32].

- Moment-Based Descriptors: While not a direct similarity metric, the comparison of d-band moments (center, width, skewness, kurtosis) provides a complementary, compressed representation of the DOS shape for rapid assessment [29].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

This section provides a detailed workflow for employing DOS similarity in catalyst discovery, from initial computation to experimental validation.

Computational Screening Protocol

Objective: To identify catalyst candidates with DOS similar to a reference material (e.g., Pd) from a large pool of potential compositions.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define the Reference System:

- Select a high-performance reference catalyst (e.g., Pd for H₂O₂ synthesis).

- Obtain its stable surface (e.g., Pd(111)) and compute its projected DOS using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This serves as

DOS₁(E).

Generate Candidate Structures:

- Construct a library of potential candidate structures. For bimetallics, this may involve numerous stoichiometries and crystal phases (e.g., B2, L1₀).

- DFT Settings: Use standardized parameters for accuracy and comparability.

Calculate DOS for Candidates:

- Perform DFT calculations to obtain the total DOS for the most stable surface of each candidate. This is

DOS₂(E). - It is critical to include both d-band and sp-band states, as sp-states can play a dominant role in certain reactions, such as O₂ adsorption [16].

- Perform DFT calculations to obtain the total DOS for the most stable surface of each candidate. This is

Compute Similarity Metric:

- For each candidate, calculate the ΔDOS value relative to the reference using the formula in Table 1 with a chosen

σ(e.g., 7 eV). - Rank all candidates based on their ΔDOS values, where lower values indicate greater similarity.

- For each candidate, calculate the ΔDOS value relative to the reference using the formula in Table 1 with a chosen

Apply Secondary Filters:

- Filter candidates based on:

Experimental Validation Protocol

Objective: To synthesize and test the catalytic performance of the computationally screened candidates.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Catalyst Synthesis:

- Synthesize the top-ranked candidate materials. For bimetallic alloys, methods may include impregnation, co-precipitation, or solvothermal synthesis to achieve the desired phase and nanostructure.

Physicochemical Characterization:

- Confirm the composition, crystal structure, and morphology using techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

- Verify the electronic structure using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to provide experimental correlation with the computed DOS.

Catalytic Performance Testing:

- Evaluate the catalytic activity for the target reaction (e.g., H₂O₂ direct synthesis, HER, ORR) under relevant conditions.

- Measure key performance indicators such as conversion, selectivity, yield, and stability over time.

Validation of the Descriptor:

- Compare the performance of the identified candidates with the reference material and with control materials that have low DOS similarity.

- A successful screening is demonstrated when candidates with high DOS similarity exhibit performance comparable to, or better than, the reference [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Resources for DOS Similarity Studies in Catalysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| VASP Software [29] [16] | Performs ab initio DFT calculations to obtain electronic structures, including DOS. | Core engine for computing the DOS of reference and candidate surfaces. |

| Materials Project Database [29] | A repository of computed material properties for over 100,000 structures; provides initial crystal structures and stability data. | Source of candidate intermetallic compounds and their thermodynamic data. |

| pymatgen Library [29] | A robust Python library for materials analysis; useful for structure manipulation, analysis, and generating surfaces. | Used to construct surface slabs from bulk crystals and analyze calculated DOS. |

| Projected Augmented-Wave (PAW) Pseudopotentials [29] [16] | Treats the interaction between core and valence electrons in DFT calculations. | Essential for accurate and efficient computation of valence electron DOS. |

| Pourbaix Diagram Toolkit [29] | Predicts the thermodynamic stability of materials in aqueous electrolytes as a function of pH and potential. | Assessing the electrochemical stability of candidate catalysts under operating conditions. |

The protocols outlined provide a robust framework for using DOS similarity as a predictive descriptor in catalyst design. The quantitative metrics, particularly the Gaussian-weighted ΔDOS and the Tanimoto coefficient, offer a direct path from electronic structure calculation to candidate selection. The successful application of this method, demonstrated by the discovery of high-performance, low-cost alternatives to Pd catalysts, validates its power and promises to significantly accelerate the discovery cycle for a wide range of catalytic materials.