Unlocking Microbial Worlds: A Comprehensive Guide to Illumina Sequencing for Ecology Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in microbial ecology.

Unlocking Microbial Worlds: A Comprehensive Guide to Illumina Sequencing for Ecology Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in microbial ecology. It covers foundational principles, from the historical context of microbial ecology to the specific advantages of Illumina platforms for characterizing unculturable microbes and complex communities. Detailed methodological workflows are presented, including sample preparation, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing for various applications like outbreak monitoring and host-pathogen interaction studies. The guide also addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for sampling, DNA extraction, and data analysis, alongside a comparative analysis of Illumina sequencing against other methodological approaches. Finally, it explores the future implications of these technologies for environmental sustainability, restoration ecology, and biomedical research, highlighting the paradigm shift towards understanding and managing microbial communities for ecosystem health.

The Microbial Ecology Revolution: From Leeuwenhoek to Next-Gen Sequencing

Defining Microbial Ecology and Its Impact on Human and Environmental Health

Microbial ecology is the scientific discipline dedicated to the study of the relationships and interactions within microbial communities, as well as the interactions between these microbes and their environment, within a defined space [1]. We live in a microbial world where microorganisms are fundamental to virtually every ecosystem on Earth, influencing processes from the human gut to global biochemical cycles [2] [3]. The field examines microbes—including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists, and viruses—not as isolated entities but as dynamic communities that form complex, interactive networks [2] [3].

The core concepts of microbial ecology are essential for understanding life on Earth. All macroorganisms, including humans, have co-evolved with microbial communities, which are now understood to be critical to their hosts' fitness and phenotypic expression [2]. The holobiont concept, first proposed by Lynn Margulis, describes the entity formed by a host and its symbionts, while the hologenome refers to the sum of the genetic information of both the host and its symbiotic microorganisms [2]. This framework recognizes the holobiont as a complex unit and an essential entity in biological evolution, with the microbiome being transmitted between generations [2].

Microbial ecology has expanded our understanding of life by revealing that humans and other animals are supraorganisms, composed of both their own cells and a vast number of microbial cells that perform essential functions [2]. These microbiomes provide vital ecosystem services that benefit health through homeostasis, and their disruption, known as dysbiosis, can have significant consequences for disease development [2].

The Human and Environmental Microbiome

The Human as a Supraorganism

The human body is colonized by a diverse array of microbial communities, with the number of microbial cells exceeding human cells by at least tenfold [4]. These microbial cells are not merely passengers; they are integral to human physiology, metabolism, nutrition, and immunity [2]. The collective genomes of this host-associated microbial life are called the microbiome, while the term microbiota refers to the microbial cells themselves [2] [1].

Humans acquire their initial microbiota during birth. Seminal work by Dominguez-Bello demonstrated that vaginally delivered babies acquire bacteria primarily from the mother's vagina (mostly Lactobacilli), while babies born via C-section acquire microbes mainly from the skin [2]. This initial microbial exposure is crucial for priming the neonatal immune system. Postnatal development of the microbiome continues with feeding; breast milk provides Lactobacilli and Bifidobacterium, which are influential in shaping the immune system, while formula feeding alters the baby's microbiota [2]. The introduction of solid food around six months introduces new bacterial diversity that steadily increases until about three years of age [2].

The composition of the human microbiota varies significantly across different body sites, each maintaining a careful balance between host response and microbial colonizers [2]. The following table summarizes the key microbial niches in the human body.

Table 1: Microbial Niches in the Human Body

| Body Site | Dominant Microbial Phyla/Genera | Key Functions & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gut | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes; Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia [2] [4] | Development of immunity, physiology, nutrition, resistance to pathogens; highest bacterial diversity [2]. |

| Oral Cavity | Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Actinomyces, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas [2] | - |

| Skin | Corynebacteriaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, Staphylococcaceae; Propionibacterium spp. in sebaceous areas [2] [4] | - |

| Respiratory Tract | Corynebacterium, Cutibacterium, Streptococcus, Dolosigranulum [4] | - |

| Vagina | Often dominated by Lactobacillus (varies by ethnicity) [2] | Lactic acid production maintains low pH; glycogen-rich environment [2]. |

The Environmental Microbiome and Its Connection to Human Health

Environmental microbiomes are vastly more diverse than human-associated microbiomes [4]. These microbial communities are critical for global biochemical cycles, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon cycles, through processes like nitrogen fixation, mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification [4].

There is an intrinsic and dynamic link between environmental and human microbiomes. Humans have evolved over millions of years in direct and intimate contact with environmental microbes, and human physiology is now intrinsically linked to them [5]. However, modern urbanization has reduced exposure to diverse environmental microbiota, which may contribute to a hidden disease burden, including immune dysregulation [5]. This has led to recommendations for urban planning to incorporate large public green spaces, which can function as ecosystems that deliver diverse aerobiomes, potentially improving public health by re-introducing health-giving microbial exposures [5].

The interaction between environmental and human microbiomes is a critical area of research. While pathogenic microbes have received more attention due to their immediate health effects, beneficial environmental microbes may act as modulators of the human microbiome [4]. Conservation and thoughtful design of our environments are thus crucial for maintaining the microbial diversity essential for human health.

Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease

Homeostasis and Dysbiosis

A healthy, balanced microbiome is in a state of homeostasis and supplies essential ecosystem services that benefit the host [2]. Beneficial microbes protect against pathogen colonization through various mechanisms, including resource competition, production of anti-microbial compounds, and modulation of the host immune system [4]. For example, gut bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus stimulate the immune system and provide protection against gastrointestinal infections, while Faecalibacterium has a protective role in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer [4].

The loss of the indigenous microbiota or a shift in its composition leads to dysbiosis, an imbalance that can have significant disease consequences [2]. Dysbiosis can be triggered by various factors, including antibiotic use, diet changes, and other ecological pressures [1]. When a person takes antibiotics, for instance, the drugs kill both pathogenic germs and beneficial microbes, resulting in an unbalanced microbiome [1]. This creates an opportunity for pathogens, including antimicrobial-resistant ones, to dominate, increasing the risk of infection [1].

Microbial Ecology in Disease Pathogenesis

Dysbiosis and specific microbial actors are implicated in a wide range of diseases. The link between microbes and cancer was highlighted decades ago when Helicobacter pylori was identified as a Group 1 carcinogen for gastric cancer [2]. More recently, Fusobacterium nucleatum, an opportunistic oral commensal, has been found to be dominant in the colons of patients with colorectal cancer [2]. This bacterium produces the virulence factor FadA, which increases colonic epithelial cell permeability [2].

The process of how colonization can lead to infection is clearly demonstrated in healthcare settings [1]. A patient colonized with an antimicrobial-resistant pathogen (e.g., on the skin or in the gut) may not initially have an infection. However, when the patient's microbiome is disrupted by antibiotics, the resistant pathogen is not killed and can outcompete the beneficial germs, becoming dominant. Subsequently, this dominant pathogen can invade the body, causing a life-threatening infection that is difficult to treat [1].

Table 2: Microbial Ecology Concepts in Health and Disease

| Concept | Definition | Impact on Health |

|---|---|---|

| Homeostasis | The careful balance between the host response and its colonizing microbiota [2]. | Maintains health through development of immunity, physiology, and nutrition [2]. |

| Dysbiosis | The loss of the indigenous microbiota or a shift to an imbalanced state [2]. | Contributes to many pathologies, including infectious diseases, inflammatory conditions, and cancer [2]. |

| Colonization | When a germ is found on or in the body but does not cause symptoms or disease [1]. | Can represent a reservoir for potential future infection, especially if the microbiome is disrupted [1]. |

| Dominance | When a particular microbe makes up a large portion (>30%) of a microbial community [1]. | Increased portion of a pathogen is associated with higher risk for development of infection, sepsis, or other adverse outcomes [1]. |

Fundamentals of Illumina Sequencing in Microbial Ecology

From Sanger to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The field of microbial ecology was revolutionized by the advent of DNA sequencing technologies. Early studies relied on Sanger sequencing, which, while highly accurate, was labor-intensive, time-consuming, and low-throughput [6]. The development of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, such as those developed by Illumina, enabled massive parallel analysis, reducing the cost and time required for sequencing while dramatically increasing throughput [6].

Illumina's NGS platforms use sequencing by synthesis (SBS) technology, which relies on DNA polymerase and the detection of fluorescent signals as nucleotides are incorporated into the nascent DNA strand [6]. This allows for millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced simultaneously, making it possible to profile complex microbial communities from environmental or human samples in unprecedented detail [7].

Key Sequencing Approaches for Microbial Ecology

Two primary NGS approaches are used in microbial ecology studies: amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics.

- 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: This targeted approach sequences a specific hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which serves as a phylogenetic marker [8]. It is a cost-effective method for determining the taxonomic composition of a bacterial community and comparing diversity (alpha and beta diversity) across samples [8]. However, it primarily profiles bacteria and archaea, offers limited functional insight, and is susceptible to amplification biases [8].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This untargeted approach sequences all the DNA fragments in a sample [8]. It allows for the simultaneous assessment of taxonomic composition (potentially at the strain level) and the functional genetic potential of the entire community, including viruses and eukaryotes [8]. Its disadvantages include higher cost, greater computational demands, and the fact that it reveals functional potential rather than actual activity [8].

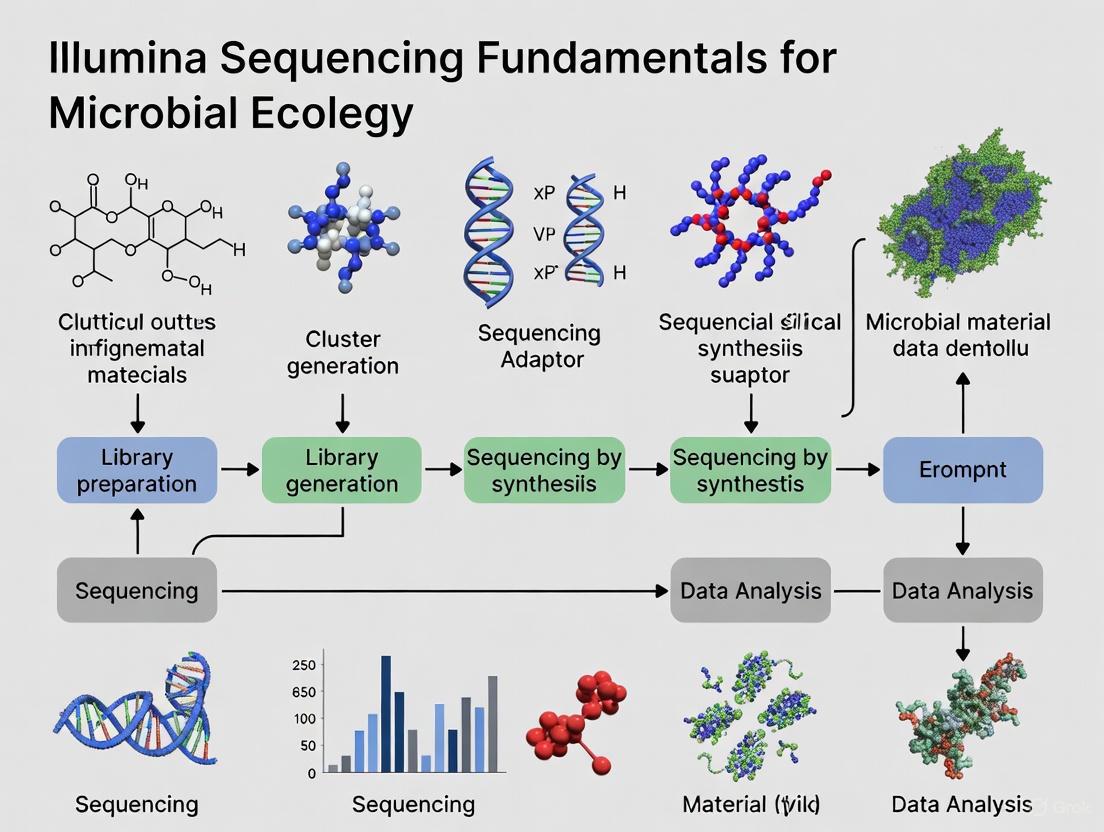

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for an Illumina-based microbiome study, from sample collection to biological insight.

Diagram 1: Workflow for an Illumina-based microbiome study. The process begins with sample collection and proceeds through DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing on an Illumina platform, bioinformatic analysis, and finally, biological interpretation.

The Critical Importance of Strain-Level Resolution

It has become increasingly apparent that microbial functions, including those relevant to human health, are often strain-specific [8]. A strain is defined as germs with very similar genetics and one or more genetic traits that make them different from other strains [1]. For example, while some strains of Escherichia coli are harmless gut commensals, others are enterohemorrhagic pathogens or probiotics [8].

Strain-level analysis is crucial for translational applications but presents challenges. Traditional 16S amplicon sequencing often clusters sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold, which typically groups organisms at the genus or species level, obscuring strain-level differences [8]. While newer algorithms can resolve finer differences, shotgun metagenomics is better suited for strain-level identification. This can be achieved by calling single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or by identifying the presence or absence of variable genomic elements, such as genes from the pangenome [8]. Achieving sufficient sequencing depth for strain-level resolution via SNV calling requires deep coverage, often 10x or more, which can be computationally intensive and expensive for complex communities [8].

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Design

Multi-Omics Integration

To move beyond a catalog of "who is there" and "what they could do," microbial ecology increasingly relies on multi-omics approaches that integrate various data types to understand what microbes are actually doing in their environment [8].

- Metatranscriptomics: Sequences all the RNA in a community, revealing which genes are actively being transcribed under specific conditions [8]. This provides a dynamic view of community activity but requires careful sample preservation and is sensitive to the exact timing of collection.

- Metaproteomics: Identifies and quantifies the proteins present in a community, linking genetic potential to functional molecules [8].

- Metabolomics: Profiles the small-molecule metabolites, which represent the end products of microbial activity and can directly influence the host [8].

Integrating these data layers with metagenomics provides a powerful, holistic view of microbial community structure and function. However, this integration requires sophisticated computational tools and careful experimental design to ensure that samples for different 'omics' layers are collected and processed in a parallel and comparable manner [8].

Quantitative Fundamentals and Experimental Robustness

A critical challenge in microbiome science is ensuring that analyses reflect the underlying biology rather than technical artifacts. Amplicon sequencing data are compositional, meaning they convey relative abundance (proportions) rather than absolute abundance [9]. This property has major implications for data analysis, as an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon necessarily leads to a decrease in others.

Robust experimental design for microbial ecology must account for several key factors:

- Library Size Normalization: Samples have different numbers of sequence reads (library sizes), which must be normalized before comparison. Common methods include rarefying (subsampling), proportions, and variance-stabilizing transformations [9].

- Confounding Factors: The microbiome is highly sensitive to environmental exposures like diet, medications, and host genetics. These covariates must be measured and accounted for in epidemiological studies [8].

- Replication and Power: Studies must be sufficiently powered to detect effects, which requires adequate sample sizes and technical replication to account for variability in sample processing and sequencing [8].

The following table outlines key reagents and materials used in Illumina-based microbiome studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Illumina-Based Microbial Ecology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation Kits | Stabilizes microbial community DNA/RNA at the moment of collection to prevent shifts. | Sample Collection [8] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Lyses microbial cells and purifies genomic DNA from complex sample matrices (e.g., stool, soil). | DNA Extraction [7] |

| PCR Enzymes & Primers | For 16S studies: Amplifies target hypervariable regions. For shotgun: Amplifies library fragments. | Library Preparation [7] |

| Illumina Library Prep Kits | Prepares DNA fragments for sequencing by adding flow-cell binding adapters and sample indices. | Library Preparation [7] |

| Illumina Sequencing Kits | Contains enzymes, buffers, and fluorescently labeled nucleotides for Sequencing-by-Synthesis. | Illumina Sequencing [7] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Software for quality control, read assembly, taxonomic assignment, and functional profiling. | Bioinformatic Analysis [8] |

Experimentally Capturing Microbial Interactions

Microbial interactions are context-dependent and can result in a range of ecological outcomes, including mutualism, commensalism, competition, and exploitation [3]. Mapping these interactions experimentally is a non-trivial task. A variety of innovative culture systems have been developed to capture these different dimensions, moving beyond traditional liquid co-cultures [3].

These systems are often combined with various methods to measure microbial fitness and growth, including optical density, quantitative PCR (qPCR) with specific primers, amplicon sequencing combined with optical density, and plate counts [3]. The choice of experimental system determines which attributes of an interaction can be captured, such as whether it is bidirectional, contact-dependent, involves volatile compounds, or incorporates ecological feedback and dynamics [3]. High-throughput versions of these assays are essential for systematically mapping interaction networks and understanding community architecture [3]. The diagram below illustrates the process of moving from sample collection to the mapping of microbial interaction networks.

Diagram 2: Workflow for mapping microbial interaction networks. This involves collecting samples, cultivating microbial communities in high-throughput systems, characterizing phenotypic outcomes, constructing an interaction matrix from the data, and finally generating a network map of the interactions.

The study of microbial ecology, supercharged by Illumina and other NGS technologies, has fundamentally altered our understanding of human and environmental health. We now recognize that health is not merely the absence of pathogens but is deeply dependent on the stability and function of our associated microbial ecosystems. The implications for drug development and clinical practice are profound.

Future directions in the field include the development of microbiome therapeutics. Strategies like fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and live biotherapeutic products (e.g., Rebyota and VOWST) are already approved for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection and are known to reduce the number of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in treated patients [1]. Other emerging strategies include the use of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) for precise pathogen reduction and the application of probiotic consortia designed to restore a healthy microbial community [1].

Furthermore, the concept of One Health—which recognizes the close interdependence between the health of humans, animals, plants, and the environment—is now a key element of global health initiatives [6]. Understanding the structure and function of microbial communities across these ecosystems is essential for addressing global challenges such as antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic diseases, and climate change [6]. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, becoming more accurate, affordable, and portable, they will further empower researchers to decipher the complex rules of microbial ecology and leverage this knowledge to improve health outcomes across the planet.

The field of microbial ecology has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of genomic technologies, moving from traditional culture-dependent methods to sophisticated culture-independent approaches centered on next-generation sequencing (NGS). This evolution has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of microbial communities, revealing unprecedented diversity and functional capabilities that were previously inaccessible through conventional techniques [10]. For decades, culture-dependent methods served as the cornerstone of microbiology, relying on the growth of microorganisms in laboratory conditions using various nutrient media to isolate and identify individual microbial species [10]. While these techniques enabled detailed study of microbial physiology and biochemistry, they suffered from a fundamental limitation now known as the "great plate count anomaly"—the observation that only a small fraction (typically <1%) of microbial diversity in most environments can be cultivated under laboratory conditions [10].

The development of culture-independent methods, particularly those leveraging Illumina sequencing technology, has enabled researchers to analyze microbial communities without cultivation, providing a more comprehensive view of microbial ecosystems in their natural habitats [10]. This transition represents more than just a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental paradigm shift in how we investigate, understand, and utilize the microbial world. By allowing direct analysis of genetic material from environmental samples, culture-independent NGS approaches have uncovered vast reservoirs of previously unknown microbial diversity and enabled new discoveries across diverse fields including human health, environmental science, and biotechnology [11] [12].

The Era of Culture-Dependent Methods

Principles and Techniques

Culture-dependent methods encompass traditional microbiological techniques that rely on growing microorganisms in artificial laboratory environments. These approaches use various selective and non-selective nutrient media to either stimulate the growth of microbial populations as a whole or select for particular types of microorganisms [10]. Common non-selective media include R2A agar, tryptic soy broth, and plate count agar, which support the growth of diverse aerobic microbes [13]. Selective media such as cetrimide for Pseudomonas species, MacConkey agar for Gram-negative bacteria, and BYCE agar for Legionella species enable targeted isolation of specific microbial groups [13].

In field settings, practical tools like dip slides for aerobic microbes and Biological Activity Reaction Tests (BARTs) provide convenient alternatives to laboratory plating [13]. BARTs employ selective media in specialized tubes to encourage growth of various microbial types when inoculated with water samples. The visual reaction patterns and timing of microbial growth in these systems help identify and quantify microorganisms present in industrial water systems and other environments [13].

Applications and Limitations

Culture-dependent techniques have proven invaluable for numerous applications in microbial research and diagnostics. These methods allow for isolation and preservation of pure microbial strains essential for detailed physiological studies and biotechnological applications [10]. They enable comprehensive assessment of microbial growth characteristics, nutrient requirements, and metabolic capabilities, and facilitate antimicrobial susceptibility testing crucial for clinical microbiology [10]. Furthermore, culture-based approaches provide opportunities for discovery of novel bioactive compounds including antibiotics and antifungals, and enable genetic manipulation and strain improvement for industrial applications [10].

Despite these advantages, culture-dependent methods face significant limitations that restrict their effectiveness for comprehensive microbial community analysis:

- Limited representation: They detect only cultivable microorganisms, missing the vast majority (>99%) of microbial diversity in most environments [10]

- Selection bias: They preferentially select for fast-growing or easily cultivable microorganisms, potentially misrepresenting true community structure [10]

- Artificial conditions: Laboratory media cannot replicate complex environmental conditions, potentially altering microbial behavior and interactions [10]

- Time-intensive nature: These methods require specialized media, long incubation times, and rigorous sterile techniques, making them unsuitable for large-scale ecological studies [10]

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of Culture-Dependent Methods

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Enables detailed physiological study of isolated strains | Only detects <1% of total microbial diversity |

| Allows antimicrobial susceptibility testing | Introduces bias toward fast-growing organisms |

| Supports discovery of novel bioactive compounds | Cannot replicate complex environmental conditions |

| Facilitates genetic manipulation | Time-consuming and labor-intensive |

| Provides pure cultures for biotechnological applications | May alter native microbial behavior and interactions |

The Rise of Culture-Independent NGS

Historical Development of Sequencing Technology

The transition from culture-dependent to culture-independent methods represents one of the most significant advancements in modern microbiology. This shift began with the development of first-generation sequencing methods, notably the chain-termination technique developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977 [11]. The commercial launch of the Applied Biosystems ABI 370 automated sequencer in 1987 marked a critical milestone, significantly increasing the speed and accuracy of DNA sequencing through fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides and capillary electrophoresis [11].

The true revolution began with the emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies in the mid-2000s, which enabled massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [11] [14]. A pivotal development occurred in the mid-1990s at Cambridge University, where scientists Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman pioneered the concept of sequencing by synthesis (SBS) while using fluorescently labeled nucleotides to observe polymerase activity at the single molecule level [15]. Their creative discussions during the summer of 1997 led to breakthroughs in using clonal arrays and massively parallel sequencing of short reads using solid phase sequencing with reversible terminators—concepts that became the foundation for SBS technology [15].

The commercialization journey began with the formation of Solexa in 1998, which secured initial seed funding and established corporate facilities by 2000 [15]. Critical technological integration occurred in 2004 when Solexa acquired molecular clustering technology from Manteia, enabling amplification of single DNA molecules into clusters that enhanced sequencing fidelity and accuracy while generating stronger signals for detection [15]. In 2005, the company sequenced the complete genome of bacteriophage phiX-174—the same genome Sanger had first sequenced using his method—generating over 3 million bases from a single run and demonstrating the unprecedented power of SBS technology [15]. Following a reverse merger with Lynx Therapeutics that same year, Solexa launched the Genome Analyzer in 2006, giving scientists the power to sequence 1 gigabase (Gb) of data in a single run [15]. The acquisition of Solexa by Illumina in early 2007 accelerated the commercialization and refinement of NGS technology, leading to the powerful sequencing platforms widely used today [15].

Fundamental Principles of NGS

Next-generation sequencing represents a fundamental departure from both traditional Sanger sequencing and culture-dependent methods. The basic NGS process involves fragmenting DNA or RNA into multiple pieces, adding adapters, sequencing the libraries, and reassembling them to form a genomic sequence [14]. While conceptually similar to capillary electrophoresis in its reconstruction approach, the critical difference lies in NGS's ability to sequence millions to billions of fragments in a massively parallel fashion, dramatically improving speed and accuracy while reducing costs [14].

The core NGS workflow consists of four essential steps:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolation of DNA or RNA from samples through cell lysis and purification from other cellular components [14]

- Library Preparation: Fragmentation of purified DNA or RNA samples into smaller pieces, followed by addition of specialized adapters to fragment ends—a crucial process for enabling efficient amplification and sequencing [14]

- Sequencing: Placement of flow cells into sequencing systems where sequencing-by-synthesis occurs; Illumina's proven SBS chemistry detects single bases as they are incorporated into growing DNA strands [14]

- Data Analysis: Conversion of raw sequence data into biological insights through connected data platforms with integrated secondary and tertiary analysis [14]

Table 2: Evolution of Key DNA Sequencing Technologies

| Sequencing Technology | Sequencing Principle | Amplification Method | Read Length (bp) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Chain termination | PCR | 400-900 | Low throughput, high cost per base |

| 454 Pyrosequencing | Sequencing by synthesis | Emulsion PCR | 400-1000 | Homopolymer errors |

| Ion Torrent | Sequencing by synthesis (H+ detection) | Emulsion PCR | 200-400 | Homopolymer signal degradation |

| Illumina | Sequencing by synthesis (reversible terminators) | Bridge PCR | 36-300 | Signal crowding at high densities |

| SOLiD | Sequencing by ligation | Emulsion PCR | 75 | Substitution errors, short reads |

| PacBio SMRT | Real-time sequencing | Without amplification | 10,000-25,000+ | Higher cost per sample |

| Oxford Nanopore | Electrical signal detection | Without amplification | 10,000-30,000+ | Higher error rate (~15%) |

NGS Workflows and Methodologies in Microbial Ecology

Sample Processing and Sequencing Approaches

The application of NGS in microbial ecology primarily utilizes two complementary approaches: marker gene studies and whole-genome shotgun (WGS) metagenomics [12]. Each method offers distinct advantages and addresses different research questions, with the choice depending on study objectives, sample type, and available resources.

Marker gene analysis focuses on sequencing specific phylogenetic marker genes to reveal the diversity and composition of taxonomic groups present in environmental samples [12]. The most commonly used marker genes include:

- 16S rRNA gene: For analyzing bacteria and archaea [12]

- Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region: For characterizing fungal communities [12]

- 18S rRNA gene: For profiling microbial eukaryotes [12]

This approach involves targeted amplification of hypervariable regions of these marker genes, which provides taxonomic signals for classifying microorganisms. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene is frequently targeted using primers such as 515F (GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) and 806R (GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT) [13]. After amplification, the resulting libraries are sequenced, typically using Illumina MiSeq or similar platforms with paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2 × 250 bp or 2 × 300 bp) to obtain sufficient overlap for constructing high-quality consensus sequences [13] [12].

In contrast, WGS metagenomics takes an untargeted approach by sequencing all genomic material present in a sample, enabling simultaneous analysis of biodiversity and functional potential of microbial communities [12]. This method sequences the entire DNA content without prior amplification of specific genes, allowing identification of all domains of life—including bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, viruses, and plasmids—along with their genomic content [12]. WGS metagenomics provides several advantages over marker gene approaches, including identification of organisms at species and strain levels, recovery of whole-genome sequences through metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), and characterization of functional genes and metabolic pathways [12].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipelines

The massive datasets generated by NGS platforms require sophisticated bioinformatics processing to extract biologically meaningful information. While specific tools and workflows vary depending on the sequencing approach and research questions, several common steps form the foundation of most analysis pipelines.

For marker gene studies, the bioinformatics workflow typically includes:

- Quality Filtering and Preprocessing: Removal of low-quality sequences, sequencing adapters, and short reads using tools like Trimmomatic, PRINSEQ, or FASTX-Toolkit [12]

- Paired-end Read Joining: Merging of forward and reverse reads using programs such as PEAR or fastq-join to create longer, higher-quality consensus sequences [12]

- Clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): Grouping sequences based on similarity thresholds (typically 97%) using algorithms like UPARSE to define taxonomic units [13]

- Taxonomic Classification: Assignment of taxonomic identities using reference databases such as SILVA, Greengenes, or the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) [13] [16]

- Diversity and Statistical Analysis: Calculation of alpha and beta diversity metrics and statistical testing using packages like vegan, picante, and ggplot2 in R [13]

For WGS metagenomics, the analysis pipeline involves additional complex steps:

- Quality Control: Similar initial quality filtering as marker gene analysis, with exploratory quality assessment using FASTQC or SeqKit [12]

- Sequence Assembly: Reconstruction of longer contiguous sequences (contigs) from short reads using assemblers designed for complex metagenomic data [12]

- Binning and Genome Reconstruction: Grouping contigs into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance patterns [12]

- Gene Prediction and Annotation: Identification of coding sequences and functional annotation using databases like KEGG, COG, and eggNOG [12]

- Taxonomic and Functional Profiling: Characterization of community composition and metabolic potential through alignment to reference databases or de novo analysis [12]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for NGS Microbial Ecology

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, MO-BIO UltraClean Fecal DNA Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from various sample types |

| PCR Amplification | 16S rRNA primers (515F/806R), Taq polymerase, dNTPs | Target amplification for marker gene studies |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera XT, TruSeq DNA PCR-Free, adapter sequences | Preparation of DNA fragments for sequencing |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput DNA sequencing |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer, FASTQC | Assessment of DNA quality and sequence data |

| Sequence Processing | Trimmomatic, PEAR, USEARCH, MOTHUR | Quality filtering, read joining, and preprocessing |

| Taxonomic Classification | SILVA database, Greengenes, RDP Classifier | Taxonomic assignment of sequence data |

| Functional Analysis | KEGG, COG, eggNOG, MetaCyc | Functional annotation of genes and pathways |

Comparative Analysis: Culture-Dependent vs. Culture-Independent Methods

Technical Comparisons and Complementary Applications

Direct comparisons between culture-dependent and culture-independent methods reveal both stark contrasts and complementary strengths. A landmark 2014 study examining bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid specimens from lung transplant recipients provided compelling evidence for the superior detection sensitivity of NGS approaches [16]. The researchers found that bacteria were identified in 44 of 46 (95.7%) BAL fluid specimens by culture-independent pyrosequencing, significantly more than the number detected by conventional culture (37 of 46, 80.4%) or reported as pathogens (18 of 46, 39.1%) [16]. This study also established important correlations between culture results and culture-independent indices, finding that culture growth above 10^4 CFU/ml was significantly associated with increased bacterial DNA burden, decreased community diversity, and increased relative abundance of specific pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa [16].

Similarly, a 2024 study comparing microbial populations in industrial water samples using both BARTs (culture-dependent) and NGS (culture-independent) demonstrated that while overall agreement existed between the methods, in some cases the most abundant taxa found in water samples differed significantly from those detected in BARTs [13]. This highlights how growth-based methods may select for certain microorganisms based on their adaptability to laboratory conditions rather than their actual abundance in the original environment.

The integration of both approaches often yields the most comprehensive understanding of microbial systems. Culture-dependent methods remain invaluable for obtaining pure isolates necessary for detailed physiological studies, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and biotechnological applications [10]. Meanwhile, culture-independent NGS approaches provide unprecedented insights into total microbial diversity, community dynamics, and functional potential [10]. This complementary relationship is particularly powerful when NGS guides targeted cultivation efforts by revealing which microorganisms warrant isolation attempts based on their abundance and potential ecological significance.

Applications in Water Quality and Clinical Diagnostics

The transition from culture-dependent to culture-independent methods has produced particularly significant impacts in water quality assessment and clinical diagnostics. In water quality research, the decades-old "gold standard" of culture-based enumeration of fecal indicator bacteria (FIB)—including total coliforms, Escherichia coli, and Enterococci—is being complemented and in some cases replaced by molecular approaches [17]. While FIB cultivation has proven useful for assessing microbial water safety, these proxies are imperfect as they may originate from non-human sources and their predictive power for pathogen presence can be compromised by environmental interactions [17].

NGS-based methods have enabled development of more specific microbial source tracking approaches using human-associated genetic markers from genera like Bacteroides [17]. Beyond source tracking, metagenomic analyses of waterborne microbial communities provide insights into processes affecting water quality, including algal blooms, contaminant biodegradation, and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes [17]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has recognized this paradigm shift by approving DNA-based methods for quantification of the fecal indicator Enterococcus [17].

In clinical diagnostics, NGS has revolutionized pathogen identification and outbreak investigation. Metagenomic sequencing (mNGS) enables agnostic analysis of all nucleic acids in clinical samples, allowing detection of rare, atypical, or unexpected pathogens without prior knowledge of their presence [18]. This approach proved crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic, when RNA-based mNGS of a respiratory sample from a patient in Wuhan enabled identification of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 [18]. Beyond pathogen discovery, NGS has become indispensable for tracking viral variants, investigating foodborne illness outbreaks, and assessing antimicrobial resistance [18]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's GenomeTrakr Network exemplifies how WGS data from foodborne pathogens is being aggregated and shared across public health laboratories to enable real-time comparison and analysis, leading to numerous public health interventions including food recalls and outbreak investigations [18].

The evolution from culture-dependent methods to culture-independent NGS represents one of the most transformative developments in modern microbiology. This transition has fundamentally expanded our understanding of microbial diversity, revealing that the microbial world is vastly more complex and diverse than previously imagined from culture-based studies alone. The continued advancement of NGS technologies—characterized by decreasing costs, increasing throughput, and improving accuracy—promises to further democratize access to genomic tools and expand their applications across diverse fields [11] [14].

Looking ahead, several trends are likely to shape the future of microbial ecology research. The integration of multiple sequencing technologies—combining the high accuracy of Illumina short-read sequencing with the long-read capabilities of PacBio and Oxford Nanopore platforms—will enable more comprehensive genome reconstruction from complex samples [12]. The development of single-cell genomics approaches will allow characterization of microbial functionality at the individual cell level, providing insights into heterogeneity within microbial populations [10]. Advancements in meta-omics integration—combining metagenomics with metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics—will enable more complete understanding of microbial community functions and activities in situ [10].

Furthermore, the ongoing reduction in sequencing costs—exemplified by Illumina's achievement of the $200 human genome—will make NGS increasingly accessible for routine monitoring and diagnostic applications [19]. This accessibility, combined with improvements in bioinformatics tools and computational methods, will support the development of more sophisticated models predicting microbial community dynamics and their impacts on human health and ecosystem functioning.

In conclusion, while culture-dependent methods retain important roles in microbiology for obtaining isolates and conducting functional studies, culture-independent NGS approaches have irrevocably transformed our ability to characterize microbial communities in their natural complexity. The continued evolution of these technologies, framed within the context of Illumina sequencing advancements, promises to further unravel the profound influence of microorganisms on human health, ecosystem functioning, and biotechnological innovation. As these tools become increasingly integrated into research and applied settings, they will undoubtedly continue to reveal new dimensions of microbial life and enable novel approaches to addressing some of humanity's most pressing challenges.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed microbial ecology research by providing unprecedented insights into complex microbial communities. Among the various NGS platforms, Illumina sequencing technology stands out for its high accuracy, scalability, and throughput. This technical guide details the core principles of Illumina sequencing, focusing on its proprietary sequencing by synthesis (SBS) chemistry and massively parallel sequencing approach. We examine the complete NGS workflow from sample preparation to data analysis, highlight key methodological considerations for microbial studies, and explore applications in environmental microbiology, food safety, and ecosystem restoration. The comprehensive overview provided herein serves as a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage genomic insights in their microbial investigations.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) represents a revolutionary approach to genetic analysis that enables rapid, high-throughput sequencing of DNA and RNA fragments. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, NGS processes millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously in a massively parallel fashion, dramatically reducing costs and time requirements while expanding the scale of genomic studies [14] [20]. This technological advancement has proven particularly transformative in microbial ecology, where researchers routinely characterize complex microbial communities, track pathogen evolution, and investigate microbial functions in environmental systems.

Illumina's NGS technology has emerged as a widely adopted platform for microbial investigations due to its exceptional data accuracy, broad dynamic range, and application flexibility [20]. The technology can be applied to entire genomes, targeted regions of interest, or transcriptomes, allowing researchers to address diverse biological questions about microbial identity, function, and activity [21]. In restoration ecology and environmental monitoring, NGS enables deep characterization of microbial communities that drive critical ecosystem processes, providing insights that were previously inaccessible with culture-based methods [22].

Fundamental Principles of Illumina Sequencing

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) Chemistry

The core technology underlying Illumina sequencing platforms is sequencing by synthesis (SBS), a sophisticated biochemical process that tracks nucleotide incorporation in real-time as DNA chains are synthesized. This method employs fluorescently-labeled reversible terminators that enable single-base resolution during sequencing [23]. In each cycle, all four deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) compete for incorporation, minimizing sequence context bias and ensuring highly accurate base calling.

The SBS process operates through a repeating cycle of nucleotide incorporation, imaging, and cleavage. Specifically, each dNTP contains a fluorescent label and a reversible terminator that halts further extension after incorporation. Following each nucleotide addition, the flow cell is imaged to identify the incorporated base based on its fluorescent signal. The terminator and fluorescent label are then cleaved, allowing the next cycle to begin [24] [23]. This cyclical process repeats for a predetermined number of cycles, generating sequence reads of specific lengths tailored to application requirements.

Recent advancements in SBS chemistry, particularly the development of XLEAP-SBS, have delivered significant improvements in sequencing speed, fidelity, and robustness. This enhanced chemistry features up to 2× faster incorporation speed and up to 3× greater accuracy compared to standard Illumina SBS chemistry [23], enabling researchers to obtain higher quality data in less time for their microbial ecology studies.

Massive Parallelization

A defining characteristic of Illumina NGS technology is its massive parallel sequencing capability. While conventional Sanger sequencing processes individual DNA fragments sequentially, Illumina platforms simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments [14] [20]. This parallel processing capability enables extraordinary throughput, allowing researchers to sequence entire microbial genomes in a single run or to multiplex hundreds of samples in targeted sequencing approaches.

The scale of parallelization in Illumina systems is made possible by the flow cell, a glass surface containing immobilized oligonucleotides that serve as anchors for DNA fragment attachment. Each fragment is amplified and sequenced in situ, forming distinct clusters that can be individually detected during the imaging process [24]. The massive parallelism of Illumina sequencing provides the depth of coverage necessary for detecting rare microbial variants in complex environmental samples and for assembling complete genomes from metagenomic data.

Key Technological Differentiators

Several technological innovations distinguish Illumina sequencing from other NGS platforms. The reversible terminator chemistry fundamentally eliminates errors associated with homopolymer sequences (strings of identical nucleotides), a common challenge in alternative sequencing technologies [23]. Furthermore, the natural competition between all four reversible terminator-bound dNTPs during each sequencing cycle minimizes incorporation bias, ensuring balanced representation of all nucleotide sequences.

Illumina sequencing supports both single-read and paired-end library approaches. Paired-end sequencing, which sequences both ends of each DNA fragment, provides significant advantages for microbial genome assembly, structural variant detection, and gene expression analysis through improved mappability and resolution [23]. The combination of short inserts with longer reads increases the ability to fully characterize microbial genomes, including repetitive regions that are challenging for alternative technologies.

The Illumina NGS Workflow

The standard Illumina NGS workflow comprises four integrated steps: nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [25] [14]. Each step requires careful execution and quality control to ensure optimal results for microbial ecology studies.

Nucleic Acid Extraction

The initial step in any NGS workflow involves isolating genetic material from microbial samples, which may include pure cultures, complex environmental samples, or clinical isolates. The quality of extracted nucleic acids critically impacts downstream sequencing results, making this a crucial stage for obtaining reliable data [24].

Key considerations for nucleic acid extraction include:

- Yield: Sufficient quantities of DNA or RNA must be obtained for library preparation, typically ranging from nanograms to micrograms depending on the application. For samples with limited material, such as single cells or low-biomass environments, whole genome amplification (WGA) or whole transcriptome amplification (WTA) may be employed [24].

- Purity: Isolated nucleic acids must be free of contaminants that could inhibit enzymatic reactions during library preparation, including phenol, ethanol, heparin, or humic acids from environmental samples [24].

- Quality: DNA integrity and RNA preservation are essential for generating representative sequencing libraries. Microbial DNA should be of high molecular weight and intact, while RNA should show minimal degradation [24].

Quality assessment typically involves UV spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios), fluorometric quantification, and gel-based or microfluidic electrophoresis to evaluate fragment size distribution [24]. For RNA sequencing, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) provides a quantitative measure of RNA quality [24].

Library Preparation

Library preparation converts extracted nucleic acids into sequenceable fragments compatible with Illumina platforms. This process involves several key steps that vary depending on the specific application but generally include [24]:

- Fragmentation: DNA or cDNA is fragmented into appropriate sizes for sequencing, typically ranging from 200-500 bp, though longer inserts are possible with certain applications.

- Adapter Ligation: Platform-specific oligonucleotide adapters (P5 and P7) are ligated to fragment ends, enabling hybridization to flow cell oligonucleotides and serving as priming sites for sequencing and amplification.

- Size Selection: Libraries may undergo size selection to remove fragments outside the desired size range, improving sequencing efficiency and data quality.

- Library Amplification: PCR amplification may be performed to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments, particularly when working with limited starting material.

- Library Quantification: Final libraries are quantified using fluorometric methods or quantitative PCR to ensure optimal loading concentrations for sequencing.

For microbial ecology studies, additional steps such as target enrichment may be incorporated to focus sequencing on specific genomic regions of interest, such as marker genes (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria) or virulence factors [21].

Clonal Amplification and Sequencing

Prior to sequencing, library fragments undergo clonal amplification to create sufficient copies for detection. In Illumina systems, this occurs on the flow cell surface through either bridge amplification or exclusion amplification (ExAmp) chemistry [24].

In bridge amplification, each library fragment anneals to complementary oligonucleotides on the flow cell and undergoes repeated rounds of amplification, forming clusters of identical DNA molecules. Each cluster originates from a single library fragment and generates sufficient signal intensity for base detection during sequencing [24]. The ExAmp chemistry, used with patterned flow cells, enables instantaneous amplification of individual fragments while preventing cross-contamination between sites [24].

Following cluster generation, sequencing proceeds using the SBS chemistry described previously. The flow cell is loaded into an Illumina sequencer, where cycles of nucleotide incorporation, imaging, and cleavage generate sequence reads of predetermined length [24]. Modern Illumina platforms offer run times ranging from several hours to days, depending on the instrument type and read length requirements.

Data Analysis

The final NGS workflow stage converts raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information through bioinformatics analysis. This process typically involves three stages [24]:

- Primary Analysis: Base calling, demultiplexing of indexed samples, and quality control assessment.

- Secondary Analysis: Read alignment to reference genomes or de novo assembly, variant calling, and quantitative analysis.

- Tertiary Analysis: Biological interpretation, including pathway analysis, variant annotation, and comparative genomics.

For microbial ecology applications, specialized bioinformatics tools are employed for tasks such as taxonomic classification, functional annotation, metagenomic assembly, and phylogenetic analysis [26]. Illumina offers integrated data analysis solutions through its DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform, which provides highly accurate, rapid secondary analysis, and BaseSpace Sequence Hub, a cloud computing environment with specialized applications for microbial genomics [26].

NGS Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Comprehensive NGS Workflow for Microbial Ecology. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps in Illumina next-generation sequencing, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints that ensure data reliability for microbial community analysis.

Key NGS Platforms and Their Applications in Microbial Ecology

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Technologies for Food Science Applications (Adapted from [27])

| NGS Technology | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Microbial Ecology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by synthesis | High throughput and accuracy | Short reads, high initial investment | Metagenetics for evaluating environmental quality; Whole Genome Sequencing of environmental pathogens; Metatranscriptomics for microbial function |

| Ion Torrent | Sequencing by synthesis, detection of H+ ions | Small sample size needed, fast sequencing | Short reads, relatively higher error rate | Metagenetics for aquatic systems; Investigation of microbial communities in specialized habitats |

| PacBio | Single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing | Long reads, high accuracy, minimal bias | High initial investment, large sequencer size | Complete genome sequencing of unculturable microbes; Analysis of complex microbial communities |

| Nanopore | Nanopore electrical signal sequencing | Long reads, portability, easy to use | Relatively high error rates | In-field identification of environmental pathogens; Real-time antimicrobial resistance gene monitoring; Spoilage microorganism detection |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in NGS Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in NGS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | DNA/RNA isolation kits for various sample types | Lyses cells and purifies genetic material from environmental samples, ensuring yield, purity, and quality needed for library preparation [24] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera XT | Fragments nucleic acids and attaches platform-specific adapters, converting samples into sequenceable libraries [25] |

| Sequence Adapters | P5 and P7 oligos | Oligonucleotides with sequences complementary to flow cell primers, enabling fragment attachment and cluster generation [24] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Microbial pathogen panels, 16S rRNA panels | Captures genomic regions of interest through hybridization, allowing focused sequencing on specific genes or microbial groups [21] |

| Quality Control Reagents | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Bioanalyzer DNA chips | Quantifies and qualifies nucleic acids and prepared libraries at critical workflow stages to ensure optimal sequencing performance [24] |

Applications in Microbial Ecology and Environmental Research

Illumina NGS technologies have enabled significant advances in microbial ecology by providing culture-independent methods for characterizing complex microbial communities. Several key applications demonstrate the transformative impact of these technologies:

Environmental Monitoring and Ecosystem Assessment

In environmental microbiology, NGS enables comprehensive analysis of microbial communities driving critical ecosystem processes. Researchers can track microbial population dynamics in response to environmental changes, monitor ecosystem health through bioindicator taxa, and characterize novel microorganisms without culturing requirements [22]. The deep sequencing capability of Illumina platforms allows detection of rare taxa that may serve as early warning indicators of environmental stress or ecosystem disruption.

Restoration ecology particularly benefits from NGS approaches, as microbial communities provide sensitive metrics of ecosystem recovery. By comparing microbial composition and functional potential between disturbed and reference sites, researchers can assess restoration progress and identify missing functional groups that may require intervention [22]. The ability to sequence entire microbial communities rather than relying on culturable representatives has revealed the astonishing diversity of microbial life and its importance in ecosystem functioning.

Food Safety and Quality Management

NGS has revolutionized food microbiology by enabling precise tracking of foodborne pathogens, monitoring microbial communities during food production, and authenticating food products. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) of foodborne pathogens allows for high-resolution strain typing and source tracking during outbreak investigations, significantly improving public health responses [27].

In fermented food production, NGS tools monitor starter culture performance, track microbial succession during fermentation, and identify spoilage organisms. Metatranscriptomic approaches reveal gene expression patterns underlying flavor development and quality attributes, enabling optimization of fermentation processes [27]. The application of NGS in food authentication helps detect fraud and verify product provenance, supporting food safety and regulatory compliance.

Microbial Source Tracking and Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance

NGS technologies provide powerful approaches for tracking microbial contamination in environmental samples and monitoring the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Metagenomic sequencing can identify sources of fecal pollution in water systems by characterizing the full microbial community composition, offering advantages over traditional marker-based methods [27].

The expanding capability to sequence complex microbial communities directly from environmental samples without culturing has revealed extensive reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. This information is critical for understanding the emergence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance and developing mitigation strategies [27] [22].

Methodological Considerations for Microbial Ecology Studies

Experimental Design and Sampling Strategies

Robust experimental design is particularly important in microbial ecology studies due to the inherent complexity and variability of microbial communities. Appropriate sampling strategies must account for spatial and temporal heterogeneity in microbial distributions [22]. Sample replication is essential for distinguishing biological patterns from technical variability, though the high cost of NGS has sometimes led to inadequate replication in previous studies [22].

Modern approaches recommend collecting sufficient replicates to capture system variability while considering sequencing depth requirements for detecting rare taxa. For composite sampling strategies, researchers should maintain individual samples for variability assessment before pooling [22]. Metadata collection encompassing environmental parameters (temperature, pH, nutrient levels, etc.) is crucial for interpreting sequencing results and identifying environmental drivers of microbial community structure.

Technical Considerations and Quality Control

Successful NGS experiments in microbial ecology require careful attention to technical details throughout the workflow. Sample collection and storage conditions must preserve nucleic acid integrity and represent in vivo microbial communities. Snap freezing, rapid drying, or chemical preservatives may be employed to prevent nucleic acid degradation or microbial growth after sampling [27].

Library preparation methods must be selected based on application requirements, with consideration for potential biases introduced during amplification or adapter ligation. For quantitative applications like metatranscriptomics, methods preserving original abundance relationships are essential [27]. Sequencing depth must be sufficient for the research question, with deeper sequencing required for detecting rare community members or for de novo genome assembly.

Bioinformatic analysis requires appropriate parameter settings and algorithm selection for specific data types and research questions. Validation of bioinformatic pipelines with mock microbial communities of known composition helps identify technical biases and optimize analytical approaches [22].

Illumina next-generation sequencing has fundamentally transformed microbial ecology research by providing powerful tools for characterizing microbial communities with unprecedented depth and resolution. The core technology, based on sequencing by synthesis with reversible terminators, enables highly accurate, massive parallel sequencing of DNA fragments, making it possible to address complex biological questions about microbial diversity, function, and dynamics.

The standardized NGS workflow—encompassing nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis—provides a robust framework for investigating microbial systems across diverse environments, from natural ecosystems to engineered systems. As sequencing costs continue to decline and analytical methods improve, NGS technologies will undoubtedly yield further insights into microbial ecology, enabling more precise monitoring of environmental systems, enhanced tracking of microbial contaminants, and improved understanding of ecosystem functioning.

For researchers in microbial ecology and environmental science, understanding the fundamental principles of Illumina sequencing technologies provides a foundation for selecting appropriate experimental approaches, interpreting sequencing data, and leveraging genomic insights to address pressing challenges in environmental sustainability, public health, and ecosystem management.

Why Illumina? Key Advantages for Microbial Community Analysis

Within the field of microbial ecology, the accurate characterization of diverse microbial communities is fundamental to advancing our understanding of environmental and human health. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized this field, with Illumina sequencing emerging as a predominant platform for 16S rRNA gene-based surveys. This whitepaper details the core technical advantages of Illumina technology, framing it as an essential tool for researchers. We examine its high data accuracy, cost-effective throughput, and robust, standardized bioinformatics pipelines that together provide a reliable foundation for broad-scale microbial community profiling, while also acknowledging its limitations relative to emerging long-read platforms.

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a cornerstone for microbial ecology research, containing conserved regions that serve as universal primer-binding sites and hypervariable regions (V1–V9) that provide taxonomic specificity for bacterial classification [28]. The choice of sequencing platform is a critical methodological decision that directly influences the resolution, accuracy, and scope of microbial community data.

Illumina sequencing has established itself as a benchmark for high-accuracy, short-read sequencing. It typically targets specific hypervariable regions, such as V3-V4, generating millions of short, paired-end reads (~300 bp) with an exceptionally low error rate of less than 0.1% [28]. This whitepaper explores the fundamental technical strengths of Illumina sequencing that make it particularly suited for microbial community analysis, especially within large-scale or reproducibility-focused studies.

Core Technical Advantages of Illumina Sequencing

A comparative analysis of sequencing technologies reveals a clear set of advantages for Illumina in specific application contexts.

Superior Sequencing Accuracy and Data Fidelity

Illumina's core strength lies in its high base-call accuracy. This technology produces sequences with an error rate of <0.1%, a figure that is crucial for distinguishing between closely related microbial taxa and for detecting rare taxa within a community [28]. This high fidelity minimizes false positives in variant calling and provides a reliable foundation for quantitative analyses. In contrast, while improving, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has historically exhibited higher error rates in the range of 5–15% [28] [29].

High-Throughput and Cost-Efficiency for Large-Scale Studies

Illumina platforms provide an unparalleled combination of high throughput and cost-efficiency, making them ideal for population-level studies and projects with large sample sizes. One study noted an average of 30,184 ± 1,146 reads per sample for Illumina, which, while lower in count than ONT in some direct comparisons, represents a highly cost-effective and accurate data generation method [30]. This scalability enables researchers to achieve the statistical power necessary for robust ecological inference.

High-Resolution Taxonomic Classification

The high accuracy of Illumina sequencing enables reliable taxonomic classification down to the genus level. A comparative study on gut microbiota demonstrated that Illumina successfully classified 80% of sequences to the genus level [30]. While this was lower than ONT's 91%, it remains a robust performance for many ecological questions focused on community shifts at the genus level or above. The high throughput ensures sufficient sequence depth to capture a broad range of taxa, with studies indicating that Illumina can capture greater species richness compared to some long-read platforms in certain sample types [28] [29].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sequencing Platforms for 16S rRNA Analysis

| Feature | Illumina (e.g., NextSeq, MiSeq) | Oxford Nanopore (e.g., MinION) | PacBio HiFi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Short (~300 bp, targets hypervariable regions) | Long (~1,500 bp, full-length 16S) | Long (~1,453 bp, full-length 16S) |

| Error Rate | Very Low (<0.1%) | Historically Higher (5-15%) | Very Low (~Q27) |

| Typical Output/Throughput | High (e.g., 30,184 ± 1,146 reads/sample [30]) | Variable, can be very high (e.g., 630,029 ± 92,449 reads/sample [30]) | Moderate (e.g., 41,326 ± 6,174 reads/sample [30]) |

| Primary Strength | High accuracy, cost-effectiveness, large-scale studies | Species-level resolution, real-time portability | High accuracy long reads for species-level resolution |

| Optimal Use Case | Genus-level profiling, broad microbial surveys, large cohort studies | Applications requiring species/strain resolution in the field or lab | Applications demanding high accuracy and species-level resolution |

Established and Standardized Bioinformatics Ecosystems

Illumina data is supported by a mature and robust bioinformatics ecosystem, which simplifies data analysis and ensures reproducibility. Workflows like nf-core/ampliseq provide standardized, containerized pipelines that handle data from quality control (using tools like FastQC and MultiQC) through primer trimming (Cutadapt), error correction, and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) generation using DADA2 [28]. This well-supported computational environment lowers the barrier to entry and facilitates comparative meta-analyses across different studies.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Illumina 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The following section outlines a standard laboratory protocol for preparing 16S rRNA gene sequencing libraries for the Illumina platform, as cited in recent literature [28].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Respiratory samples (e.g., from ventilator-associated pneumonia patients) are collected and immediately stored at -80°C to preserve microbial DNA integrity.

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted using a commercial kit (e.g., Sputum DNA Isolation Kit, Norgen Biotek). The protocol follows the manufacturer's instructions, with potential modifications to optimize DNA yield and purity for challenging sample types.

- Quality Control: The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA are assessed using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop 2000) and a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit 4).

Library Preparation for Illumina Sequencing

This protocol uses the QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel (Qiagen) [28].

- First-Stage PCR (Target Amplification): The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene is amplified using region-specific primers.

- Amplification Program:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- 20 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 60°C for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds.

- Final Elongation: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Amplification Program:

- Second-Stage PCR (Index Attachment): A second, limited-cycle PCR is performed to attach unique dual indices and Illumina adapter sequences (e.g., from the QIAseq 16S/ITS Index Kit). This enables sample multiplexing.

- Library Validation and Pooling: The final PCR products are validated (e.g., using an Agilent Bioanalyzer) and pooled in equimolar ratios to create the final sequencing library.

Sequencing

- The pooled library is loaded onto an Illumina sequencing platform, such as the NextSeq, for paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp) according to the manufacturer's specifications.

The following workflow diagram summarizes this standardized experimental process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and kits used in a standard Illumina 16S rRNA sequencing workflow, as featured in the cited experimental protocol [28].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Illumina 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Item | Function / Application | Example Product (from cited protocol) |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from complex biological samples. | Sputum DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek) [28] |

| 16S Amplicon Panel | Provides primers and master mix for targeted amplification of specific 16S rRNA hypervariable regions. | QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel (Qiagen) [28] |

| Indexing Kit | Provides unique nucleotide barcodes for multiplexing multiple samples in a single sequencing run. | QIAseq 16S/ITS Index Kit (Qiagen) [28] |

| Library Quantification | Accurate quantification of DNA library concentration prior to sequencing. | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher) [31] |

| Sequencing Platform | High-throughput instrument for generating short-read sequence data. | Illumina NextSeq [28] |

Limitations and Complementary Technologies

A complete understanding of Illumina's role requires acknowledging its limitations. The primary constraint is the short read length, which often prevents reliable classification down to the species level due to insufficient informational content in the short, targeted hypervariable regions [28] [30]. In contrast, long-read platforms like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio sequence the entire ~1,500 bp 16S rRNA gene, providing higher taxonomic resolution and enabling better differentiation of closely related species [28] [31].

Furthermore, PCR amplification steps, common to most amplicon sequencing approaches including Illumina, can introduce amplification biases, preferentially amplifying certain templates and potentially distorting true quantitative relationships [32] [33].

Consequently, while Illumina is ideal for broad microbial surveys and genus-level profiling, studies requiring species- or strain-level resolution may benefit from a hybrid sequencing approach, leveraging the strengths of both short- and long-read technologies [28] [29] [33].

Illumina sequencing remains a powerful and preferred platform for microbial community analysis, particularly for studies where high accuracy, cost-effective throughput, and reproducible genus-level classification are the primary objectives. Its well-established protocols and mature bioinformatics ecosystem make it a reliable and accessible choice for large-scale microbial surveys in both environmental and clinical settings. As the field advances, the strategic combination of Illumina's broad profiling capabilities with the high resolution of long-read technologies promises to further deepen our understanding of complex microbial ecosystems.

In the field of microbial ecology, precise terminology is foundational for interpreting data and communicating findings. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), particularly platforms developed by Illumina, has revolutionized our capacity to study complex microbial communities [34] [35]. This technical guide defines four core terms—Microbiota, Microbiome, Metagenomics, and Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs)—within the context of Illumina sequencing. A clear grasp of these concepts is essential for researchers and drug development professionals designing and interpreting microbial ecology studies.

Defining the Core Concepts

The following table provides concise definitions and key characteristics of the core terminology.

Table 1: Core Terminology in Microbial Ecology Research

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiota | The assemblage of living microorganisms present in a defined environment [36]. | • Refers to the microorganisms themselves (bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses) [36].• Often used to describe taxonomic composition (e.g., phylum, genus) [34]. |

| Microbiome | The entire ecological niche of a microbiota, including the microorganisms, their genomes, and the surrounding environmental conditions [36]. | • A broader term that encompasses the microbiota [36].• Includes the collective genomic material of the microbiota (the metagenome) and microbial functions and activities [34] [36]. |

| Metagenomics | The direct genetic analysis of genomes contained within an environmental sample, bypassing the need for cultivation [34] [37]. | • A sequencing-based approach to study the microbiome [34].• Shotgun metagenomics sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling taxonomic and functional profiling [34] [38].• 16S rRNA gene sequencing (metataxonomics) targets a specific marker gene for taxonomic profiling [38]. |

| Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) | A cluster of similar DNA sequences (e.g., 16S rRNA reads) used to classify and quantify microbial taxa in a sample [39] [37]. | • An operational proxy for a microbial species or genus, typically defined by a sequence similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [39].• Reduces dataset complexity by grouping sequences into biologically relevant units for diversity analysis [39]. |

The Technological Driver: Illumina Sequencing in Microbial Ecology

The progress in microbiome research is intrinsically linked to advancements in NGS technology. Illumina's next-generation sequencing platforms provide the high-throughput, scalable, and cost-effective data generation required to dissect complex microbial communities [35].

The paradigm shift from studying single microorganisms in isolation to analyzing entire communities was enabled by massively parallel sequencing [34]. This technology allows for the simultaneous detection, quantification, and characterization of thousands of microbial taxa and their genes from a single sample [34]. For microbiome research, two primary metagenomic sequencing strategies are employed: 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing [38].

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Metagenomic Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing (Metataxonomics) | Whole Genome Shotgun Sequencing (Metagenomics) |

|---|---|---|