Unlocking Microbial Function: A Comprehensive Guide to Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing for Biomedical Research

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has emerged as a powerful, culture-independent method for comprehensively profiling the genetic and functional potential of complex microbial communities.

Unlocking Microbial Function: A Comprehensive Guide to Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has emerged as a powerful, culture-independent method for comprehensively profiling the genetic and functional potential of complex microbial communities. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed exploration of its foundational principles, methodological workflows, and diverse applications—from tracking antimicrobial resistance to discovering novel therapeutics. We address key challenges such as host DNA contamination and data analysis complexity, offering optimization strategies and comparing its performance against 16S rRNA sequencing. By synthesizing current methodologies and validating its utility through case studies and benchmark data, this guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging functional metagenomic insights to advance biomedical and clinical research.

Beyond Taxonomy: Core Principles and Advantages of Functional Shotgun Metagenomics

Defining Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing and Its Core Principle of Unbiased Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a transformative approach in microbial ecology and functional genomics, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex microbial communities without prior cultivation. This technique operates on the core principle of unbiased sequencing, whereby all DNA fragments from a heterogeneous sample are randomly sequenced, thereby circumventing the amplification biases inherent in targeted approaches. By providing direct access to the collective genetic material of all organisms present in a sample, shotgun metagenomics facilitates simultaneous taxonomic profiling at high resolution and functional characterization of metabolic potential. This application note delineates the foundational methodologies, analytical frameworks, and practical implementations of shotgun metagenomics, with particular emphasis on its application in functional profiling research for pharmaceutical and therapeutic development.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a high-throughput, culture-independent method that involves the random fragmentation and sequencing of all DNA extracted from an environmental or clinical sample [1] [2]. The term "shotgun" derives from the methodical fragmentation of total community DNA into numerous small pieces, analogous to the scatter pattern of a shotgun blast [3]. Unlike targeted amplification techniques such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which focus on specific phylogenetic markers, shotgun metagenomics employs an untargeted approach that sequences all genomic content without preference for specific taxonomic groups or genetic elements [4]. This fundamental characteristic enables researchers to reconstruct the genomic composition of microbial communities comprehensively, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and eukaryotic microbes, while simultaneously elucidating their functional capabilities through analysis of protein-coding sequences [2] [4].

The core principle of unbiased sequencing establishes shotgun metagenomics as a hypothesis-free discovery tool that makes no a priori assumptions about community composition [5]. By avoiding targeted amplification with universal primers, this method eliminates the primer bias that can skew community representation in amplicon-based studies [6] [4]. The resultant data provides a more accurate quantitative representation of microbial abundances and enables detection of novel microorganisms that lack conserved primer binding sites or established phylogenetic markers [6]. Furthermore, the random sampling of genomic regions permits identification and characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding specialized metabolites with pharmaceutical potential, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents [7] [8].

Core Principle: Unbiased Sequencing

The foundational principle of shotgun metagenomic sequencing is its comprehensive and unbiased nature, which differentiates it fundamentally from targeted molecular approaches. This unbiased methodology manifests through several key characteristics:

Random Fragmentation and Sequencing

In shotgun metagenomics, the total DNA extracted from a sample is randomly sheared into small fragments using mechanical (e.g., sonication) or enzymatic methods [3]. These fragments are sequenced independently without selective amplification, ensuring that all genomic regions have an approximately equal probability of being sequenced [6] [2]. This process stands in direct contrast to amplicon sequencing, which relies on conserved primer binding sites and preferentially amplifies specific genomic regions, thereby introducing amplification biases that distort true microbial abundances [6] [4].

Hypothesis-Free Community Profiling

The unbiased nature of shotgun metagenomics makes it particularly valuable for exploratory studies of complex microbial communities where the composition is unknown or poorly characterized [5]. By sequencing all DNA content without predetermined targets, researchers can detect unexpected organisms, including novel microbial taxa that would be missed by targeted approaches due to sequence divergence in conserved marker genes [6]. This capability was demonstrated in a recent study of natural farmland soils, where shotgun metagenomics revealed substantial proportions of unassigned bacteria at the phylum level, indicating the presence of potentially novel microbial lineages [7].

Equal Access to All Genomic Niches

Unlike targeted approaches that focus exclusively on specific phylogenetic markers (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria/archaea, ITS for fungi), shotgun metagenomics provides equivalent access to all genomic components across all domains of life within a single assay [2] [4]. This comprehensive coverage enables researchers to study cross-domain interactions and community dynamics between bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotic microbes without requiring separate experimental procedures for each microbial group [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing vs. Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

| Feature | Shotgun Metagenomics | Amplicon Sequencing (16S/ITS) |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Approach | Untargeted; sequences all DNA | Targeted; amplifies specific gene regions |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Strain-level identification | Typically genus/species level |

| Functional Data | Yes (genes, pathways, AMR markers) | No, requires inference |

| Organisms Detected | Bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea | Bacteria (16S) or fungi/yeasts (ITS) only |

| Primer Bias | None | High (affected by primer choice) |

| Cost per Sample | Higher | Lower |

| Computational Requirements | High (complex bioinformatics) | Moderate |

| Best Applications | Functional potential, novel discoveries | Taxonomic profiling, large sample numbers |

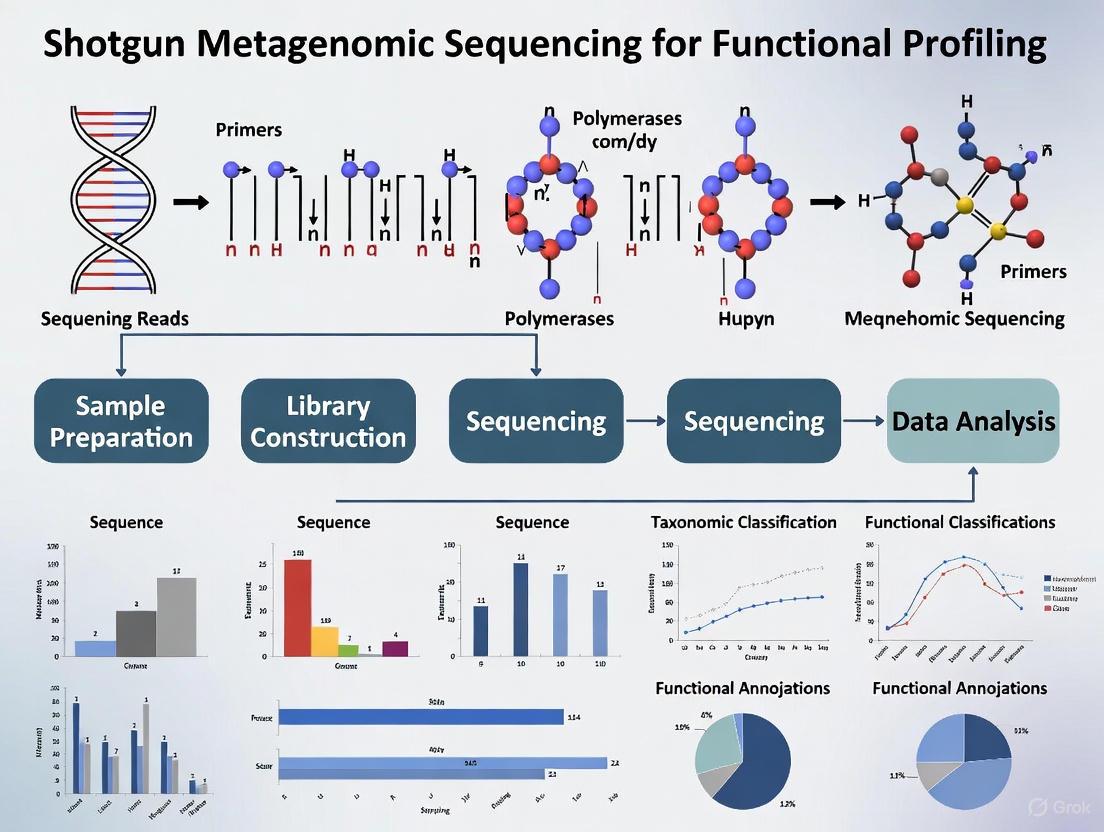

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual difference between the unbiased nature of shotgun metagenomics and targeted amplicon sequencing:

Experimental Workflow and Protocols

The successful implementation of shotgun metagenomic sequencing requires meticulous execution of a multi-stage experimental workflow, from sample collection through data analysis. Each step introduces potential biases that must be carefully managed to preserve the unbiased nature of the approach.

Sample Collection and Preservation

Sample collection represents the first critical step in maintaining community representation. Protocols must be optimized for specific sample types:

- Human-derived samples (stool, saliva, skin swabs): Collect using sterile containers, freeze immediately at -20°C or -80°C, and avoid freeze-thaw cycles [2]. For fecal samples, preservation buffers may be used if immediate freezing is not possible.

- Environmental samples (soil, water): Process immediately or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Soil samples may require homogenization and sieving to remove debris [7].

- Clinical samples (tissue, blood, CSF): Adhere to sterile collection procedures and consider host DNA depletion methods due to high human-to-microbial DNA ratios [5].

Proper documentation of metadata, including sampling time, location, and environmental parameters (e.g., pH, temperature), is essential for contextual interpretation of results [2] [7].

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

DNA extraction represents a significant source of bias in metagenomic studies. The protocol must efficiently lyse diverse microbial cell types while minimizing DNA shearing:

- Cell Lysis: Employ a combination of mechanical (bead beating), chemical (detergents), and enzymatic (lysozyme, proteinase K) methods to ensure comprehensive lysis of Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and spores [2].

- DNA Purification: Use commercial kits or phenol-chloroform extraction to remove inhibitors (e.g., humic acids in soil samples, bile salts in fecal samples) [2] [7].

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis, quantify using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit), and assess purity via spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280 ~1.8-2.0, A260/230 >2.0) [2].

The selection of DNA extraction method significantly influences the observed microbial community structure and must be consistent across all samples within a study [2].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation converts purified DNA into a format compatible with high-throughput sequencing platforms:

- DNA Fragmentation: Fragment 1-100 ng of DNA to 200-800 bp fragments using acoustic shearing (Covaris) or enzymatic fragmentation (tagmentation) [2] [3].

- Size Selection: Perform solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) bead-based clean-up to remove very short fragments and select the desired size distribution.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters containing unique dual indices (UDIs) to enable sample multiplexing [2].

- Library Amplification: Perform limited-cycle PCR (typically 4-8 cycles) to amplify the library while minimizing amplification biases.

- Library Quantification: Quantify using qPCR (for absolute molecule counting) and qualify via bioanalyzer or tape station analysis.

For Illumina platforms, sequence with 2×150 bp or 2×250 bp paired-end reads to facilitate accurate assembly and downstream analysis. The required sequencing depth varies by application: 5-10 million reads per sample for taxonomic profiling, 20-50 million reads for functional analysis, and >50 million reads for genome assembly from complex communities [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Bioinformatic Analysis Framework

The analysis of shotgun metagenomic data involves multiple computational steps to transform raw sequencing reads into biological insights. The following protocols outline the primary analytical pathways for taxonomic and functional profiling.

Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Adapter Trimming: Remove sequencing adapters and indices using tools such as Cutadapt or Trimmomatic.

- Quality Filtering: Discard low-quality reads using predetermined thresholds (e.g., Phred score >20, read length >50 bp).

- Host DNA Removal: Align reads to reference genomes of host organisms (e.g., human, mouse, plant) using BWA or Bowtie2 and remove aligning reads [5] [7].

- Quality Assessment: Generate quality reports using FastQC before and after preprocessing.

Taxonomic Profiling

Two primary approaches exist for determining microbial community composition:

Read-Based Taxonomy Assignment:

- Align quality-filtered reads to reference databases (NCBI nt, RefSeq) using alignment tools (BWA, Bowtie2) or k-mer based classifiers (Kraken2, Kaiju) [2].

- Estimate taxonomic abundances from alignment counts, normalizing for genome size and read length.

- MetaPhlAn4 utilizes clade-specific marker genes for efficient and accurate taxonomic profiling [9].

Assembly-Based Taxonomy Assignment:

- Perform de novo co-assembly of all reads using metaSPAdes or MEGAHIT to reconstruct longer contiguous sequences (contigs) [7].

- Bin contigs into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance profiles.

- Classify MAGs taxonomically using tools like GTDB-Tk against the Genome Taxonomy Database [9].

Functional Profiling

Functional characterization identifies metabolic pathways and biological processes encoded in the metagenome:

Gene Prediction and Annotation:

Pathway Reconstruction:

- Map annotated genes to metabolic pathways using HUMAnN3 or KEGG Mapper.

- Reconstruct metabolic modules to identify complete pathways present in the community [9].

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Identification:

- Scan contigs for BGCs encoding secondary metabolites (polyketide synthases, non-ribosomal peptide synthetases) using antiSMASH [7].

- Analyze domain architecture of identified BGCs to predict novel bioactive compounds.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Modern Metagenomic Profiling Tools

| Tool | Primary Function | Processing Time (10M reads) | Memory Usage | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteor2 | Taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling | 2.3 min (taxonomic), 10 min (strain) | 5 GB RAM | Integrated TFSP using environment-specific gene catalogues |

| MetaPhlAn4 | Taxonomic profiling | ~15-30 minutes | 8-16 GB RAM | Species-level resolution using marker genes |

| HUMAnN3 | Functional profiling | 1-2 hours | 16-32 GB RAM | Comprehensive pathway coverage |

| Kraken2 | Taxonomic classification | ~30 minutes | 16-64 GB RAM | Rapid k-mer based assignment |

| antiSMASH | BGC identification | Hours to days | 8-32 GB RAM | Specialized in secondary metabolite discovery |

Applications in Functional Profiling Research

Shotgun metagenomics provides unparalleled insights into the functional potential of microbial communities, with significant applications across pharmaceutical development and clinical research.

Drug Discovery and Biosynthetic Potential

The unbiased nature of shotgun metagenomics enables comprehensive mining of microbial communities for novel biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding pharmaceutically relevant compounds:

- Novel Antibiotic Discovery: Analysis of soil metagenomes from natural farmland in Ethiopia revealed numerous known and novel BGCs responsible for secondary metabolites, including polyketide synthases (PKS), non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) [7]. These BGCs represent promising candidates for developing new antibiotics to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens.

- Bioactive Compound Identification: Shotgun metagenomics facilitates identification of diverse chemical classes, including polyethers, terpenoids, alkaloids, and macrolides from unculturable microbial species [8]. For example, analysis of marine sponge microbiomes revealed seven bacterial species producing biologically active compounds with therapeutic potential [8].

Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring

Shotgun metagenomics enables comprehensive surveillance of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes within complex microbial communities:

- Resistome Profiling: Global analysis of 4,728 metagenomic samples from 60 cities created detailed profiles of microbial strains and their AMR markers, revealing distinct geographical patterns of resistance gene distribution [8].

- Resistance Mechanism Elucidation: The technique identifies not only known resistance genes but also novel mechanisms by detecting genetic rearrangements and horizontal gene transfer events that contribute to the spread of AMR [8].

Microbiome-Drug Interactions

The unbiased sequencing approach reveals complex interactions between administered pharmaceuticals and the human microbiome:

- Drug Metabolism by Microbes: Shotgun metagenomics identified Eggerthella lenta as capable of inactivating the cardiac drug digoxin, explaining treatment failure in some patients [8].

- Therapeutic Efficacy Modulation: Analysis of cancer patients undergoing PD-1 immunotherapy revealed that treatment response correlates with specific gut microbiome compositions, particularly the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila [8].

- Drug-Drug Interactions: Metagenomic approaches elucidated how amoxicillin reduces intestinal microbial diversity and slows aspirin metabolism by altering the gut community responsible for its processing [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of shotgun metagenomic sequencing requires carefully selected reagents, materials, and computational resources. The following table details essential components for conducting comprehensive metagenomic studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Storage | Sterile containers, DNA/RNA shield buffer, cryovials, liquid nitrogen | Maintain sample integrity, prevent degradation, inhibit microbial growth | Zymo DNA/RNA Shield, Streck Cell-Free DNA Tube |

| DNA Extraction | Bead beating tubes, lysis buffers, proteinase K, lysozyme, commercial extraction kits | Comprehensive cell lysis, inhibitor removal, high-quality DNA extraction | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN), MagAttract PowerSoil DNA Kit |

| Library Preparation | Fragmentation enzymes/beads, end-repair mix, A-tailing enzyme, ligation mix, unique dual indices, size selection beads | Convert DNA to sequencing-compatible libraries, enable multiplexing | Illumina DNA Prep Kit, Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit |

| Sequencing Reagents | Flow cells, sequencing primers, buffer solutions, polymerase | Generate sequence data from prepared libraries | Illumina NovaSeq S4 Reagent Kit, MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Quality control tools, aligners, assemblers, taxonomic classifiers, functional annotators | Process raw data, perform taxonomic and functional analysis | FastQC, Trimmomatic, metaSPAdes, Kraken2, HUMAnN3, antiSMASH |

| Reference Databases | Genomic, taxonomic, and functional databases | Provide reference for sequence identification and annotation | NCBI RefSeq, GTDB, KEGG, eggNOG, CARD, ResFinder |

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a paradigm shift in microbial community analysis, offering an unbiased, comprehensive approach to exploring taxonomic composition and functional potential without cultivation. The core principle of random, unbiased sequencing of all DNA content enables researchers to overcome the limitations of targeted methods and access the full genetic diversity of complex microbial ecosystems. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and analytical tools become more sophisticated, shotgun metagenomics will play an increasingly central role in functional profiling research, particularly in pharmaceutical development where understanding microbial communities' metabolic capabilities is essential for drug discovery, antimicrobial resistance monitoring, and elucidating microbiome-drug interactions. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide a foundation for researchers to implement this powerful technology in their functional profiling investigations, contributing to the advancement of this rapidly evolving field.

Within modern microbiome research, the selection of a sequencing strategy is a foundational decision that directly determines the breadth and depth of actionable biological insights. For years, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing has served as the workhorse for microbial census studies, providing a cost-effective snapshot of bacterial and archaeal composition. However, the increasing focus on the functional roles of microbial communities in health, disease, and biotechnological applications demands a more comprehensive approach. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing addresses this need by moving beyond taxonomic census to enable functional profiling. This Application Note delineates the key technical and analytical differences between these two methods, providing a framework for researchers to align their sequencing strategy with their scientific objectives.

Core Methodological Principles

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: A Targeted Approach

16S rRNA gene sequencing is a form of amplicon sequencing that targets and reads specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) of the 16S rRNA gene, a genetic marker present in all Bacteria and Archaea [10] [11]. Its methodology is PCR-dependent, involving the amplification of a single, selected gene region, which inherently limits its scope to the taxonomy encoded within that fragment [10] [12].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: An Untargeted Approach

In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing adopts an untargeted, whole-genome strategy. DNA is randomly fragmented into small pieces, and all fragments are sequenced, generating reads from across all genomic DNA present in a sample—whether from bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, or other microorganisms [10] [12]. This method is PCR-free in its core sequencing step, avoiding the amplification biases associated with primer selection and allowing for the reconstruction of complete metabolic pathways and the identification of microbial genes [10].

The fundamental difference in library preparation and data output is illustrated below.

Head-to-Head Comparative Analysis

A direct comparison of 16S and shotgun metagenomic sequencing reveals critical trade-offs in cost, resolution, and information output, which should guide experimental design.

Table 1: Key comparison between 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Approximate Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD [10] | Starting at ~$150 USD [10] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (sometimes species) [10] | Species-level and strain-level [10] [12] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [10] | All taxa: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Viruses, Protists [10] [12] |

| Functional Profiling | No direct profiling; requires prediction (e.g., PICRUSt) [10] | Yes, direct profiling of microbial genes and pathways [10] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to Intermediate [10] | Intermediate to Advanced [10] |

| Sensitivity to Host DNA | Low (due to targeted PCR) [10] [12] | High (can be mitigated with enrichment or depth) [10] [12] |

| Primary Bias | Medium to High (primer and region selection) [10] | Lower (untargeted, though analytical biases exist) [10] |

Interpreting Comparative Data

Empirical studies consistently validate the distinctions outlined in Table 1. A 2024 study comparing 156 human stool samples demonstrated that shotgun sequencing provides a more detailed snapshot in both depth and breadth, revealing a significant portion of the community that 16S sequencing misses [13]. Conversely, 16S sequencing tends to over-represent dominant bacteria, showing sparser data and lower alpha diversity [13] [14]. While abundance estimates for shared taxa are often positively correlated, the agreement between the two methods decreases substantially at the species level due to the limited resolution of short 16S reads and discrepancies between reference databases [13] [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

1. DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from the sample using a commercial kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit [13]). The integrity and concentration of the DNA should be quantified via fluorometry.

2. PCR Amplification: Amplify the target hypervariable region(s) (e.g., V3-V4) using locus-specific primers that include Illumina adapter overhangs and sample-specific barcodes to enable multiplexing [10] [13].

- Primer Example (V3-V4): Forward: 5´-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3´; Reverse: 5´-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3´ [16].

3. Library Preparation: Clean up the amplified PCR products to remove primers, enzymes, and impurities. This often involves bead-based size selection to retain the expected amplicon size [10].

4. Pooling and Quantification: Combine the barcoded libraries in equimolar proportions into a single pool. Quantify the final pooled library accurately using qPCR to ensure optimal cluster density on the sequencer [10].

5. Sequencing: Sequence the pooled library on an Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq 1000/2000, or similar platform, typically generating 150 bp or 250 bp paired-end reads [10] [11].

Protocol: Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

1. DNA Extraction & QC: Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. For samples with high host contamination, consider implementing an enrichment protocol, such as centrifugation-based size separation to enrich for microbial cells [17].

2. Library Preparation (Tagmentation): This typically involves a tagmentation step, which simultaneously fragments the DNA and adds adapter sequences using an enzyme like Th5 (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep kit) [10]. This step replaces traditional restriction enzyme digestion and ligation.

3. PCR Amplification and Indexing: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to amplify the tagmented DNA and add unique dual indices (UDIs) to each sample [10].

4. Size Selection and Clean-up: Purify the final library to remove leftover PCR reagents and perform size selection to remove very short or long fragments, ensuring a uniform library [10].

5. Pooling, Quantification, and Sequencing: Pool the indexed libraries, quantify precisely, and sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq or similar high-output platform. Sequencing depth is critical; for human gut samples, 10-20 million paired-end reads per sample is a common starting point, though "shallow shotgun" at lower depths (e.g., 2-5 million reads) is a cost-effective alternative for large cohort studies [10] [12] [18].

The following diagram summarizes the two experimental workflows.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pathways

The analytical pathways for 16S and shotgun data diverge significantly, reflecting the complexity and information content of the underlying data.

16S rRNA Data Analysis

The primary goal is taxonomic classification.

- Quality Filtering & Denoising: Tools like DADA2 or QIIME 2 are used to filter low-quality reads, remove chimeras, and infer exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [13].

- Taxonomic Assignment: ASVs are classified by comparing them to reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) [10] [13]. Resolution is typically reliable to the genus level, with species-level assignment often being tentative [10] [16].

- Functional Prediction: Tools like PICRUSt predict functional potential based on the identified taxonomy and known genomic content, but this is an inference, not a direct measurement [10].

Shotgun Metagenomic Data Analysis

This allows for a multi-layered, comprehensive analysis.

- Quality Control & Host Removal: Tools like FastQC and KneadData are used for quality trimming and to remove host-derived reads.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Reads can be aligned to comprehensive genome databases (e.g., GTDB) using tools like MetaPhlAn4 or Meteor2 for accurate species and strain-level profiling [18] [13].

- Functional Profiling: Reads are mapped to functional databases (e.g., KEGG, CAZy) using tools like HUMAnN3 or Meteor2 to quantify the abundance of specific genes and metabolic pathways directly from the community [10] [18].

- Strain-Level Analysis: Tools like StrainPhlAn can track strain-level single nucleotide variants (SNVs) across samples, enabling high-resolution studies of microbial transmission and evolution [18].

Table 2: Essential bioinformatics tools for shotgun metagenomic analysis

| Analysis Type | Tool | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Profiling | MetaPhlAn4 [18] | Uses clade-specific marker genes for efficient taxonomy assignment. |

| Taxonomic, Functional &\nStrain Profiling | Meteor2 [18] | An all-in-one tool for Taxonomic, Functional, and Strain-level Profiling (TFSP) using ecosystem-specific gene catalogues. |

| Functional Profiling | HUMAnN3 [10] [18] | Quantifies the abundance of microbial metabolic pathways in a community. |

| Strain-Level Analysis | StrainPhlAn [18] | Infers strain-level population genetics from metagenomic data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and kits for metagenomic sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| High-Yield DNA\nExtraction Kit | To efficiently lyse diverse microbial cells (gram-positive, gram-negative, fungal) and recover high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA. | NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) [13] |

| 16S Amplicon\nLibrary Prep Kit | Provides optimized primers and master mix for specific amplification of 16S variable regions with minimal bias. | Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Prep [11] |

| Shotgun Metagenomic\nLibrary Prep Kit | Enables efficient fragmentation (tagmentation) and preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from whole genomic DNA. | Illumina DNA Prep [11] |

| Metagenomic\nStandard | A defined, mock microbial community used as a positive control to assess sequencing accuracy, pipeline performance, and cross-batch variability. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard |

The choice between 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the research question. 16S sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for large-scale, hypothesis-generating studies focused specifically on bacterial and archaeal composition at the genus level. It is particularly suited for sample types with high host DNA contamination where targeted amplification is advantageous [10] [12].

In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing is the unequivocal method of choice for studies demanding resolution, breadth, and functional insight. When the research objectives require species- or strain-level discrimination, profiling of non-bacterial kingdoms (viruses, fungi), or direct assessment of the functional potential encoded in the metagenome, shotgun sequencing is indispensable [10] [13] [17]. As sequencing costs continue to fall and analytical tools like Meteor2 mature, shotgun metagenomics is poised to become the new gold standard for holistic functional profiling of complex microbial ecosystems [18].

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, enabling unparalleled comprehensive analysis of complex microbial communities. Unlike targeted approaches, this method involves randomly fragmenting the total DNA extracted from an environmental, clinical, or experimental sample into numerous small pieces, which are sequenced and subsequently reconstructed bioinformatically [10] [19]. This culture-independent technique facilitates a holistic view of the microbiome's taxonomic composition and functional potential, providing insights that are critical for advanced research and therapeutic development [18].

The principal advantage driving its adoption is its capacity to simultaneously identify and characterize all domains of life—Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, and Viruses—from a single sequencing experiment, and to link this taxonomic information to specific metabolic functions, resistance genes, and community dynamics [10] [20]. This application note details the protocols and quantitative advantages that make shotgun metagenomics an indispensable tool for scientists and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Advantages Over Targeted Sequencing

The selection of a sequencing methodology is a critical first step in experimental design. While 16S rRNA gene sequencing has been widely used for bacterial community analysis, shotgun metagenomics provides a far more extensive and functionally informative dataset. The table below summarizes a direct, head-to-head comparison of the two methods, highlighting the key metrics that are vital for research and development.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Factor | 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost (per sample) | ~$50 USD [10] | Starting at ~$150 USD; price depends on sequencing depth [10] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Bacterial genus (sometimes species) [10] | Bacterial species and often strains [10] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [10] [19] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, and Viruses [10] [19] |

| Functional Profiling | No (only predicted via tools like PICRUSt) [10] | Yes, direct profiling of microbial genes and pathways [10] |

| Bioinformatics Requirements | Beginner to Intermediate [10] | Intermediate to Advanced [10] |

| Sensitivity to Host DNA | Low [10] | High; requires mitigation via sequencing depth or enrichment [10] |

Beyond the comparative advantages listed in Table 1, the performance of modern shotgun metagenomics tools is exceptional. For instance, the Meteor2 pipeline, which leverages environment-specific microbial gene catalogues, has demonstrated a ≥45% improvement in species detection sensitivity in shallow-sequenced datasets compared to other established tools like MetaPhlAn4. Furthermore, it improves functional abundance estimation accuracy by at least 35% compared to HUMAnN3 and can track more strain pairs, capturing an additional 9.8-19.4% in model datasets [18] [21]. In its fast configuration, Meteor2 can complete taxonomic analysis in approximately 2.3 minutes and strain-level analysis in 10 minutes for 10 million paired reads, using a modest 5 GB RAM footprint [18].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Shotgun Metagenomics

The following section outlines a standard end-to-end protocol for shotgun metagenomic sequencing, from sample preparation to data analysis. This workflow is designed to ensure comprehensive profiling of all microbial domains present in a sample.

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

Principle: The goal is to extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA that accurately represents the entire microbial community. The choice of extraction method can significantly impact the recovery of DNA from different microbial taxa, especially those with tough cell walls like Gram-positive bacteria or fungi [10] [19].

Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (e.g., stool, soil, water) in sterile containers and immediately freeze at -80°C to preserve nucleic acid integrity.

- Cell Lysis: Employ a combination of mechanical (e.g., bead beating), chemical (e.g., detergents), and enzymatic (e.g., lysozyme, proteinase K) lysis methods to ensure the rupture of a wide variety of microbial cell walls.

- DNA Purification: Purify the total DNA using spin-column-based kits or magnetic beads to remove contaminants, inhibitors, and humic substances.

- Quality Control: Assess DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) and purity/integrity using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) and gel electrophoresis.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Principle: The extracted DNA is fragmented and prepared for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters. The fragmentation can be achieved via mechanical shearing or enzymatic tagmentation [10].

Protocol:

- DNA Fragmentation: Fragment the purified DNA to a uniform size (typically 300-800 bp) using acoustic shearing or enzymatic tagmentation.

- Adapter Ligation: Repair the ends of the DNA fragments and ligate sequencing adapters containing unique molecular barcodes (indexes) to allow for multiplexing of samples.

- Library Amplification: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to amplify the adapter-ligated fragments. Clean up the final library to remove PCR reagents and size-select for the desired fragment range.

- Library QC and Pooling: Quantify the final libraries using qPCR and pool them in equimolar ratios.

- Sequencing: Sequence the pooled libraries on a high-throughput platform such as Illumina, PacBio, or MGI, aiming for a minimum of 10-20 million reads per sample for complex communities, though deeper sequencing is required for low-abundance members or strain-level resolution [10].

Specialized Protocol: Fungal Enrichment for Mycobiome Analysis

Principle: Fungi often constitute a minor fraction of the total microbial biomass in communities like the gut, making their detection challenging with standard shotgun sequencing. An enrichment protocol based on the differential centrifugation of fungal and bacterial cells can significantly improve fungal sequence recovery [20].

Protocol:

- Sample Homogenization: Resuspend the sample (e.g., 0.5 g of feces) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and homogenize thoroughly.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Perform an initial low-speed centrifugation (e.g., 500 × g for 5 minutes) to pellet large debris and some fungal cells.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and perform a series of higher-speed centrifugations (e.g., 2,000-4,000 × g for 10-20 minutes) to pellet the larger fungal cells while leaving many bacterial cells in suspension.

- The pellet is enriched for fungal cells, while the supernatant is enriched for bacterial cells.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA separately from the fungal-enriched pellet and the bacterial-enriched supernatant using a robust lysis method.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Proceed with library preparation and sequencing as described in Section 3.2. This enrichment protocol, combined with comprehensive fungal databases, provides a cost-effective and reliable approach for integrated bacteria-fungi (mycobiome) analysis at the species level [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in a standard shotgun metagenomics experiment.

Bioinformatic Analysis for Comprehensive Profiling

The raw sequencing data (reads) must be processed through a bioinformatic pipeline to generate biological insights. A robust pipeline integrates taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP) [18].

Core Steps:

- Quality Control & Preprocessing: Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to assess read quality and remove low-quality sequences, adapters, and host-derived reads (e.g., human DNA) [20].

- Taxonomic Profiling: This can be achieved via:

- Read-based Alignment: Directly align reads to comprehensive reference databases (e.g., RefSeq, GTDB) using tools like Kraken [21] or Meteor2 [18].

- De novo Assembly: Assemble reads into longer contiguous sequences (contigs) using tools like MEGAHIT. Contigs can then be binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) for higher-resolution analysis [10].

- Functional Profiling: Align reads or assembled genes against functional databases to determine the abundance of:

- Strain-Level Profiling: Track single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in core genes to distinguish between closely related strains, which can have divergent functional roles, using tools like StrainPhlAn or Meteor2 [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Shotgun Metagenomics

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Robust lysis and purification for diverse sample types; critical for unbiased representation. | Extraction from soil, stool, or swab samples with complex matrices. |

| Library Prep Kits | Enzymatic (e.g., Tagmentation) or mechanical fragmentation and adapter ligation. | Preparing sequencing-ready libraries from purified genomic DNA. |

| Functional Databases (e.g., KEGG, CARD, dbCAN) | Curated collections of genes and pathways for functional annotation. | Annotating metabolic pathways, antibiotic resistance, and CAZymes. |

| Taxonomic Databases (e.g., GTDB, RefSeq) | Reference genomes for classifying sequencing reads. | Determining the relative abundance of microbial species. |

| Analysis Pipelines (e.g., Meteor2, bioBakery) | Integrated software suites for end-to-end analysis. | Performing unified taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP) [18]. |

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a powerful and now accessible technology that provides a definitive advantage for the comprehensive profiling of Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, and Viruses. Its ability to move beyond mere cataloging of species to deliver deep functional insights and strain-level resolution makes it an essential methodology for researchers aiming to understand the complex role of microbial communities in health, disease, and the environment. The continued development of sophisticated computational tools like Meteor2 and expanding reference databases are further enhancing its accuracy, speed, and accessibility, solidifying its position as the cornerstone of modern microbiome research.

Direct Access to Microbial Gene Content for Functional Interpretation

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling researchers to decode the genetic potential of entire microbial communities without the need for cultivation. A primary goal of this approach is the direct access and functional interpretation of microbial gene content, moving beyond taxonomic census to understand the biochemical capabilities of a microbiome [23]. This direct linkage between genetic content and ecosystem function is crucial for applications ranging from human health diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

However, a significant portion of genes in any microbial community are uncharacterized, creating a substantial "functional dark matter" problem [24]. Overcoming this challenge requires robust bioinformatic tools and well-validated experimental protocols that together enable accurate gene-centric profiling. This Application Note details the methodologies for directly accessing and interpreting microbial gene content, providing researchers with a structured framework for functional metagenomics.

Quantitative Profiling Tools for Gene-Centric Analysis

Specialized bioinformatics tools are essential for transforming raw sequencing data into quantitative profiles of gene abundance and function. The table below summarizes key tools for direct gene content analysis.

Table 1: Bioinformatics Tools for Direct Microbial Gene Content Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Type of Analysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meteor2 [18] | Taxonomic, Functional, & Strain-level Profiling (TFSP) | Integrated TFSP using microbial gene catalogs | - Supports 10 ecosystems; 63+ million genes- Annotates KO, CAZymes, ARGs- Fast mode: ~12.3 min for 10M reads |

| MIDAS v3 & StrainPGC [25] | Strain-level gene content estimation | Pangenome profiling & strain-specific gene content | - Resolves intraspecific gene content variation- Uses UHGG reference collection- Integrates data across multiple samples |

| FUGAsseM [24] | Protein function prediction | Assigns functions to uncharacterized proteins | - Leverages metatranscriptomic coexpression- Uses two-layer random forest classifier- Predicts Gene Ontology (GO) terms |

These tools address different aspects of the functional interpretation pipeline. Meteor2 provides a comprehensive solution for quantitative profiling, leveraging environment-specific microbial gene catalogs to deliver integrated taxonomic, functional, and strain-level insights [18]. Its benchmark performance shows a 45% improvement in species detection sensitivity for shallow-sequenced datasets compared to alternatives, with a 35% improvement in functional abundance estimation accuracy [18].

For investigating strain-level functional variation, MIDAS v3 with the StrainPGC method enables precise estimation of gene content in individual strains by combining pangenome profiling with strain tracking across multiple samples [25]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying strain-specific traits such as antibiotic resistance or virulence factors that may be missed in community-level analyses.

To address the challenge of uncharacterized genes, FUGAsseM employs a novel machine learning approach that integrates multiple data types, including metatranscriptomic coexpression patterns, genomic proximity, and sequence similarity, to assign putative functions to previously unannotated protein families [24]. This method has successfully provided high-confidence functional predictions for over 443,000 protein families, many of which had weak or no homology to previously characterized proteins [24].

Experimental Protocol for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

This section details a standardized protocol for generating high-quality metagenomic data suitable for gene-centric functional analysis, with specific examples from digestive microbiota studies.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Sterile swabs (for rectal/vaginal/penile sampling) | Microbial biomass collection with minimal contamination [26] [27] |

| Storage tubes (sterile) | Sample integrity maintenance during transport | |

| DNA Extraction | MP-soil FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil [27] | Comprehensive cell lysis and DNA purification from complex samples |

| Inhibitor removal reagents | Elimination of PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids) | |

| Library Prep & Sequencing | Illumina DNA Prep kits | Illumina-compatible library construction |

| PacBio SMRTbell libraries | HiFi long-read library preparation [28] | |

| Bioinformatics | MIMIC2 murine gene catalog [26] | Reference for mouse gut microbiome studies |

| UHGG collection [25] | Comprehensive human gastrointestinal genome reference |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Sample Collection and Preservation For human gut microbiome studies, collect fecal samples or rectal swabs. For rectal swabs, clean the perianal area with soap, water, and 70% alcohol. Insert a sterile saline-moistened swab 4-5 cm into the anal canal, rotate gently, and place immediately into a sterile tube [27]. Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen or store at -80°C until DNA extraction. For other body sites or environmental samples, use appropriate collection methods to minimize contamination.

Step 2: DNA Extraction and Quality Control Extract genomic DNA using a standardized kit such as the MP-soil FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, following manufacturer instructions with bead-beating for comprehensive cell lysis [27]. Assess DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit), purity via spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio ~1.8-2.0), and integrity through gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer. High-molecular-weight DNA is particularly critical for long-read sequencing approaches [28].

Step 3: Library Preparation and Sequencing For short-read sequencing: Fragment DNA by sonication or enzymatic digestion, then perform end-repair, adapter ligation, and size selection. For Illumina platforms, use platform-specific kits [27]. For long-read sequencing: For PacBio HiFi metagenomics, prepare SMRTbell libraries without fragmentation and sequence on Revio or Sequel II/IIe systems to generate highly accurate long reads that enable improved metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) and strain resolution [28]. The required sequencing depth depends on the application, but 10-20 Gb per sample is typical for deep functional profiling [27].

Step 4: Bioinformatic Processing and Quality Control

- Read QC and Adapter Trimming: Use tools like Fastp (v0.23.0) to remove adapters and low-quality reads (average quality score <20, length <50 bp after trimming) [27].

- Host DNA Depletion: Map reads to host genome (e.g., human, mouse) using BWA (v0.7.17) or Bowtie2 (v2.5.4) and remove matching reads [18] [26].

- Gene Abundance Profiling: Map quality-controlled reads to an appropriate reference gene catalog using SOAPaligner (v2.21) or Bowtie2 with stringent identity thresholds (typically ≥95%) [18] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from sample to functional interpretation:

Advanced Computational Methods for Functional Interpretation

Integrated Taxonomic and Functional Profiling

Meteor2 exemplifies the modern approach to integrated analysis by using microbial gene catalogs organized into Metagenomic Species Pan-genomes (MSPs) as its fundamental analytical unit. The tool identifies "signature genes" within each MSP as reliable indicators for detecting, quantifying, and characterizing species [18]. For functional annotation, Meteor2 integrates three complementary approaches: KEGG Orthology (KO) terms for general metabolic pathways, carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) for carbohydrate metabolism, and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) using multiple databases including ResFinder and ResFinderFG [18].

The functional abundance of a specific pathway or category is computed by aggregating the normalized abundances of all genes associated with that function. This approach enables researchers to link community composition directly to functional potential, revealing how taxonomic shifts influence ecosystem capabilities.

Novel Function Prediction Using Natural Language Processing

For the substantial portion of microbial genes lacking functional annotations, novel computational approaches show significant promise. Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms, repurposed for genomic analysis, can model "gene semantics" by treating gene families as "words" and their genomic neighborhoods as "sentences" [29].

In this approach, researchers compile a genomic corpus from publicly available genomes and metagenomes, cluster genes into families based on sequence similarity, and train word embedding models (e.g., word2vec) to create a "gene annotation space" where genes with similar contexts are adjacent [29]. These embeddings then serve as input to deep neural network classifiers that can assign functional categories to uncharacterized genes with high accuracy, even across large evolutionary distances [29].

The following diagram illustrates this NLP-based function prediction workflow:

Multi-Omics Integration for Enhanced Functional Insights

Integrating metagenomic data with metatranscriptomic information provides a powerful approach for distinguishing carried genes from actively expressed functions. The FUGAsseM method exemplifies this by leveraging community-wide coexpression patterns from metatranscriptomes alongside genomic context and sequence similarity [24].

This method employs a two-layered random forest classifier system where the first layer trains individual classifiers for each type of association evidence (coexpression, genomic proximity, etc.), and the second layer integrates these predictions using an ensemble classifier to produce final functional assignments with confidence scores [24]. This approach is particularly valuable for characterizing protein families with weak or no homology to known proteins, expanding the functional landscape of well-studied microbiomes like the human gut.

Application to Disease-Associated Microbial Communities

Direct access to microbial gene content has proven particularly valuable in clinical research, where functional potential often provides more insight than taxonomic composition alone. In a study of acute pancreatitis (AP) patients, researchers used shotgun metagenomic sequencing to investigate gut microbiome changes during disease recovery [27].

Rectal swab samples from 12 AP patients across severity levels were sequenced during both acute and recovery phases. Functional profiling revealed opposing trends in key signaling pathways during recovery from mild versus severe AP, providing potential mechanistic insights into disease resolution [27]. The study demonstrated that microbial gene content and functional potential recovery lag behind clinical symptom improvement, suggesting extended microbiome-targeted interventions might benefit patient outcomes.

This application highlights how direct functional analysis can reveal clinically relevant insights that would be missed by taxonomic profiling alone, particularly for complex diseases where microbial metabolism interacts with host physiology.

Resolving Microbial Communities to the Strain Level for Precision Insights

The human microbiome, a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, plays a fundamental role in host physiology, immunity, and metabolic processes [30]. While early microbiome research focused on genus- or species-level classification, it has become increasingly clear that substantial functional heterogeneity exists within bacterial species. Different strains of the same species can exhibit dramatically different biological properties, including variations in virulence, antibiotic resistance, metabolic capabilities, and immunomodulatory effects [31] [32]. For example, certain strains of Escherichia coli are harmless commensals that aid digestion, while others such as E. coli O157:H7 are pathogenic and can cause serious illness [33]. This functional diversity stems from the fact that microbial strains can differ by as much as 30% of their gene content despite high sequence similarity in conserved regions [32].

The transition from species-level to strain-level analysis represents a paradigm shift in microbiome research, enabling unprecedented precision in understanding microbial influences on health and disease. Strain-level variations have been linked to diverse conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, cancer treatment response, mental health disorders, and metabolic diseases [34]. Consequently, strain-level resolution has become indispensable for identifying mechanistic links between microbes and host physiology, discovering biomarkers, and developing targeted therapeutic interventions [33] [31].

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has emerged as the primary tool for achieving strain-level resolution, as it provides access to the complete genetic content of microbial communities without the limitations of amplification-based approaches [30] [35]. This application note outlines current methodologies, computational tools, and practical protocols for resolving microbial communities to the strain level, with emphasis on applications in precision medicine and drug development.

Methodological Approaches: From 16S to Shotgun Metagenomics

Technology Comparison for Varied Resolution Needs

Different sequencing technologies offer varying capabilities for strain-level analysis, with the choice depending on research goals, budget, and desired resolution [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Microbiome Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Required | Yes (targeting specific hypervariable regions) | No |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Limited (genus/species level) | High (species/strain level) |

| Functional Gene Analysis | No | Yes (full genetic content) |

| Novel Species Detection | Limited | Yes |

| Microbial Coverage | Mostly bacteria and archaea | All microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea) |

| Strain-Level Discrimination | Limited capability | High capability |

| Cost & Data Volume | Lower cost, smaller datasets | Higher cost, large datasets |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Low | High |

While 16S rRNA sequencing targets conserved regions and provides limited strain discrimination, shotgun metagenomics sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling comprehensive strain-level analysis [35]. The full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing with long-read technologies offers improved taxonomic resolution but still lacks the comprehensive functional insights provided by whole-genome shotgun approaches [33].

Advanced Strain-Resolved Bioinformatic Tools

Several specialized computational tools have been developed specifically for strain-level analysis from metagenomic data. These tools employ different algorithms and reference databases to achieve high-resolution microbial profiling.

Table 2: Strain-Level Metagenomic Analysis Tools

| Tool | Methodology | Key Features | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meteor2 [18] | Environment-specific microbial gene catalogs | Taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP); 10 ecosystem databases | 45% improved species detection sensitivity; 35% better functional abundance estimation vs. HUMAnN3 |

| StrainScan [31] | Hierarchical k-mer indexing with Cluster Search Tree (CST) | Distinguishes highly similar strains (>99.9% ANI) in complex mixtures | 20% higher F1 score for multi-strain identification vs. state-of-the-art tools |

| StrainPhlAn [18] | Species-specific marker genes | Strain tracking and identification; part of bioBakery suite | Meteor2 tracked 9.8-19.4% more strain pairs in validation |

| StrainGE [31] | K-mer based representation | Identifies representative strains in clusters (90% Jaccard similarity) | Limited resolution for highly similar strains |

| Pathoscope2 [31] [36] | Bayesian read reassignment | Maps reads to custom strain databases for identification | Used successfully in airway microbiome strain analysis |

These tools address the significant computational challenges in strain-level analysis, particularly the need to distinguish between highly similar strains (with Average Nucleotide Identity >99.9%) that may coexist in complex communities [31].

Experimental Protocols for Strain-Level Metagenomics

Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, and Library Preparation

Proper sample handling is critical for successful strain-resolved metagenomic studies. The following protocol outlines key steps for sample processing:

Sample Collection and Preservation

- Collect samples using sterile techniques to minimize contamination [36]

- For clinical samples (e.g., airway, gut), collect with appropriate swabs or containers

- Immediately place samples on dry ice or store at -80°C to preserve DNA integrity [36]

- Document patient metadata, including comorbidities, medications, and antibiotic use [36]

DNA Extraction and Host DNA Depletion

- Extract DNA using kits specifically designed for microbial DNA (e.g., QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit) [36]

- Implement host DNA depletion strategies to increase microbial sequencing depth

- Quantity DNA concentration using fluorometric methods

- Assess DNA purity (OD260/280 ratio of 1.8-2.0) and integrity [35]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Use library preparation kits compatible with metagenomic sequencing (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit) [36]

- For Illumina platforms: aim for 2×150 bp or 2×300 bp read lengths [35]

- Sequence to sufficient depth: minimum ~25 million reads/sample for complex communities [36]

- Higher sequencing depth improves detection of low-abundance strains

Computational Analysis Pipeline for Strain Resolution

Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Perform quality checks and trim low-quality reads using Trimmomatic or similar tools [36]

- Remove host-derived sequences using alignment to host genome (e.g., with Bowtie2) [36]

- Use Kneaddata for integrated quality control and contaminant removal [36]

Taxonomic and Strain-Level Profiling

- For initial community assessment, use MetaPhlAn4 for species-level profiling [18] [36]

- For strain-level resolution, apply specialized tools:

- For custom strain tracking:

Functional Profiling and Strain Characterization

- Annotate genes for KEGG orthology, carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [18]

- Identify functional modules: Gut Brain Modules (GBMs), Gut Metabolic Modules (GMMs), and KEGG modules [18]

- Track single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in signature genes for strain-level dynamics [18]

Key Applications in Precision Medicine and Therapeutics

Therapeutic Areas Transformed by Strain-Level Insights

Strain-level microbiome analysis is opening new frontiers in therapeutic development across multiple disease areas:

Targeted Live Biotherapeutics

- Strain-level resolution enables development of precise microbial consortia for therapeutic restoration of microbiome function [33]

- Example: FDA-approved SER-109 for recurrent C. difficile infection represents a new class of live biotherapeutic products [33]

- Knowing exact strain composition ensures safety and prevents unintended disruption of microbial ecosystems [33]

Cancer Therapy Personalization

- Specific bacterial strains modulate responses to cancer immunotherapy [33] [34]

- Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains potentiate PD-L1 blockade through IL-12 induction [34]

- Faecalibacterium prausnitzii strains demonstrate anti-tumoral effects through IL-12 and NK cell stimulation [34]

- Strain-level profiling could identify patients likely to respond to specific immunotherapies

Antibiotic Resistance Management

- Strain-level tracking enables monitoring of antibiotic resistance gene dissemination [33]

- Understanding strain-specific responses to antibiotics informs smarter antibiotic stewardship [33]

- Meteor2 provides specialized annotation for antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) using multiple databases [18]

Gut-Brain Axis Modulation

- Early research links specific bacterial strains to mental health conditions [33]

- Example: Alistipes strains associated with anxiety disorders can be modulated through targeted interventions [33]

- Strain-level insights may lead to novel interventions for neuropsychiatric conditions

Drug-Microbiome Interaction Prediction

Computational approaches now enable prediction of how pharmaceuticals impact specific microbial strains:

- Machine learning models integrate drug chemical properties and microbial genomic features to predict growth inhibition [37]

- Random forest models demonstrate high accuracy (ROC AUC 0.972) in predicting drug-microbe interactions [37]

- These models facilitate drug safety evaluation and personalized treatment planning based on individual microbiome composition [37]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful strain-level metagenomic research requires specialized reagents and computational resources. The following table outlines essential components of the strain-level analysis toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Strain-Level Metagenomics

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Qiagen) | Enriches for microbial DNA while minimizing host DNA contamination [36] |

| Library Prep | NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB) | Prepares high-quality sequencing libraries from metagenomic DNA [36] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq 2000, PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore | Generate short or long reads for strain discrimination; choice depends on resolution needs [33] [36] |

| Reference Databases | Custom species-specific RefSeq databases, Meteor2 catalogs | Enable precise strain identification through comprehensive reference collections [18] [36] |

| Quality Control | Kneaddata, Trimmomatic | Perform read quality control, adapter trimming, and host sequence removal [36] |

| Taxonomic Profiling | MetaPhlAn4, Meteor2 | Provide species-level community profiling as foundation for strain-level analysis [18] [36] |

| Strain-Level Analysis | StrainScan, Meteor2, Pathoscope2 | Specialized tools for discriminating closely related strains in complex communities [18] [31] [36] |

| Functional Annotation | KEGG, dbCAN3, ResFinder | Decode functional capabilities of identified strains (metabolism, CAZymes, ARGs) [18] |

Strain-level resolution of microbial communities represents a transformative advance in microbiome research, enabling unprecedented precision in understanding host-microbe interactions. The integration of sophisticated sequencing technologies, specialized computational tools, and standardized experimental protocols provides researchers with a powerful framework for uncovering strain-specific effects on health and disease. As these methodologies continue to mature and become more accessible, strain-level microbiome analysis is poised to become a fundamental component of precision medicine, therapeutic development, and personalized health interventions.

From Sample to Insight: Workflow, Tools, and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized the study of microbial communities by enabling comprehensive analysis of genetic material directly from environmental or host-associated samples. Unlike amplicon sequencing, which targets specific genomic markers, this approach sequences all DNA in a sample, allowing researchers to simultaneously answer "who is there?" and "what are they capable of doing?" [6]. This culture-independent method provides deep insights into the diversity, functional potential, and dynamics of microbial ecosystems, making it indispensable for modern microbiome research and drug development [18] [6]. The power of shotgun metagenomics lies in its ability to support Taxonomic, Functional, and Strain-level Profiling (TFSP), which is crucial for a complete understanding of microbial community structures and their roles in various environments, from the human gut to environmental biomes [18].

The reliability of this powerful analytical tool, however, is entirely dependent on the pre-analytical phases of the workflow. The end-to-end process, from sample collection to library preparation, introduces multiple critical points where suboptimal practices can compromise data quality, leading to biased or erroneous conclusions. This document provides a detailed guide to these foundational steps, framed within the context of functional profiling research, to ensure the generation of high-integrity, actionable metagenomic data.

Sample Collection and Preservation

The first and often most critical phase of the metagenomic workflow is the proper collection and stabilization of samples. The integrity of the entire project hinges on decisions made at this initial stage.

Sample-Type Specific Considerations

- Whole Blood: Collect using EDTA tubes to preserve DNA integrity better than heparin or citrate. For short-term storage, keep samples at 4°C. For long-term storage, freeze at -80°C and strictly avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles to prevent DNA degradation [38]. For mammalian blood, a volume of 200 μL is typically sufficient for DNA extraction, targeting white blood cells [39].

- Saliva and Buccal Swabs: Use sterile, DNA-free containers or specialized commercial saliva collection kits like Oragene devices, which stabilize samples at room temperature [39] [38].

- Stool and Complex Biological Samples: These represent highly complex microbial communities. Ensure rapid processing or immediate freezing at -80°C to preserve the native microbial composition and prevent overgrowth of certain taxa.

- Tough and Fibrous Samples (e.g., plant matter, insect exoskeletons, bone): These require specialized lysis strategies. For insects, chitin in the exoskeleton makes DNA extraction tricky; only 30 mg of body mass is needed with modern kits [39]. For bone, a combination of chemical agents like EDTA for demineralization and powerful mechanical homogenization is often necessary [40].

Universal Preservation Principles

The overarching goal of sample preservation is to halt all biological activity, including microbial growth and enzymatic degradation of DNA. Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen, followed by storage at -80°C, is considered the gold standard for most sample types [40]. When freezing is not logistically feasible, chemical preservatives designed to stabilize nucleic acids are an effective alternative. The choice of preservation method must be tailored to the sample type, intended storage duration, and planned downstream analysis.

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

DNA extraction is the cornerstone of the metagenomic workflow. The objective is to obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA that accurately represents the entire microbial community present in the sample, without introducing Gram-positive or Gram-negative bias.

Critical Considerations for DNA Extraction

- Lysis Method: The choice between mechanical and enzymatic lysis significantly impacts community representation.

- Mechanical Lysis (e.g., bead beating) is highly effective for disrupting tough cell walls, particularly of Gram-positive bacteria, and is often essential for complete community profiling [41] [40].

- Enzymatic Lysis is gentler but may be insufficient for robust Gram-positive species, potentially leading to their under-representation [41].

- For comprehensive coverage, a combination of chemical, mechanical, and enzymatic lysis is recommended for complex samples [41].

- Input Quantity: Respect the input requirements of your extraction kit. Excessive input can overwhelm the system chemistry, leading to suboptimal enzymatic reactions and lower DNA quality [39].

- Inhibitor Removal: Samples like blood, stool, and soil contain compounds that can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions (e.g., PCR). Use kits with robust inhibitor removal technology to ensure clean DNA extracts [41].

Evaluation of DNA Extraction Methods

A 2024 study systematically evaluated DNA extraction kits for long-read metagenomics, highlighting the performance of different lysis and purification strategies [41]. The findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods for Metagenomics [41]

| Extraction Kit | Lysis Method | Purification Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA | Chemical & Mechanical (Bead Beating) | Spin-Column | Identified all bacterial species (8/8 and 6/6) in mock communities; best overall taxonomy and AMR identification. |

| Maxwell RSC Cultured Cells | Enzymatic (Lysozyme) | Magnetic Beads | Retrieved fewer aligned bases for Gram-positive species compared to mechanical lysis. |

| QIAamp DNA Mini | Enzymatic (Lysozyme & Proteinase K) | Spin-Column | Performance dependent on sample type and community composition. |

| Maxwell RSC Buccal Swab | Enzymatic (Proteinase K) | Magnetic Beads | Performance dependent on sample type and community composition. |

For long-read sequencing, which requires HMW DNA, a 2025 interlaboratory study compared HMW DNA extraction methods, with results relevant to metagenomic studies involving complex communities or host DNA depletion [42].

Table 2: Comparison of HMW DNA Extraction Kits for Long-Read Sequencing [42]

| Extraction Kit | Average Read Length (N50) | Proportion of Ultra-Long Reads (>100 kb) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire Monkey | Highest N50 values | Moderate | Excellent for achieving long read lengths. |

| Nanobind | High | Highest | Consistent yield; prominent HMW DNA profile. |

| Genomic-tip | High Sequencing Yield | Lower | High throughput sequencing yield. |

| Puregene | Moderate | Moderate | Variable performance between laboratories. |

DNA Quality Control (QC)

Rigorous QC is non-negotiable. The following metrics should be assessed:

- Quantity: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate DNA concentration measurement, as spectrophotometry can be influenced by contaminants.

- Purity: Assess via spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio ~1.8, A260/230 ratio ~2.0) to detect protein or organic compound contamination [42].

- Integrity and Fragment Size: For long-read sequencing, confirm DNA is HMW.

- Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) can visualize fragment size distribution [42].

- Digital PCR (dPCR) linkage assays provide a quantitative measure of DNA integrity, reporting the percentage of linked molecules over specific distances (e.g., 100 kb, 150 kb), which is predictive of ultra-long read sequencing performance [42].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points and steps in the sample collection and DNA extraction process.

Library Preparation for Next-Generation Sequencing

Library preparation is the process of converting the purified, fragmented DNA into a format compatible with the sequencing platform. This step is a known source of bias and must be optimized for metagenomic applications.

Standard Workflow and Innovations

The standard NGS library preparation workflow consists of four main steps [43]:

- DNA Fragmentation or Target Selection: For shotgun metagenomics, DNA is randomly sheared to a desired size. For long-read sequencing, this step focuses on preserving HMW DNA and potentially removing short fragments.

- Adapter Ligation: The addition of platform-specific adapter sequences to the ends of the DNA fragments.

- Size Selection: Critical for long-read sequencing. Methods like the Short Read Eliminator (SRE) kit use size-selective precipitation to remove DNA fragments below 10 kb, enriching for HMW DNA and improving sequencing efficiency [39].

- Library Quantification and QC: Accurate quantification of the final library is essential for pooling multiple samples and loading the sequencer at optimal density.

Innovations in library preparation are focused on reducing bias and improving efficiency. A significant advancement is the move away from traditional fixed-cycle PCR amplification. Over-amplification creates PCR duplicates, chimeric sequences, and artifacts that consume expensive sequencing reads without providing useful data. Under-amplification results in insufficient library yield and sample dropouts [44]. New technologies, such as iconPCR, now provide per-sample real-time fluorescence monitoring and dynamically adjust cycle numbers for each individual well, normalizing output and preventing the biases associated with fixed-cycle PCR [44]. This results in reduced duplicates, fewer chimeras, and improved data quality, while also saving significant time and reagents by integrating quantification and normalization into a single step [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HMW DNA Extraction Kits | Extract long, intact DNA molecules, crucial for long-read sequencing and detecting large SVs. | Nanobind kits [39], QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA [41], Fire Monkey [42]. |

| Short Fragment Removal Kits | Size-selects HMW DNA by removing fragments below a threshold (e.g., 10 kb). | Short Read Eliminator (SRE) [39]. |

| Intelligent PCR Systems | Automates and optimizes amplification, reducing over-/under-amplification bias and improving data quality. | iconPCR with AutoNorm technology [44]. |

| Bead-Free NA Extraction | Automatable nucleic acid extraction without risk of magnetic bead carryover, which can inhibit downstream reactions. | DPX NiXTips [38]. |

| Specialized Collection Kits | Stabilize specific sample types (e.g., saliva) at room temperature, preserving DNA integrity. | Oragene devices [39]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Analyze sequencing data for integrated taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP). | Meteor2 [18]. |

Integrated Experimental Protocol: From Swab to Sequence

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for a rapid shotgun metagenomic workflow, adapted from a 2024 clinical study for taxonomic and Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) gene detection [41].

Materials

- Samples: Microbial mock communities (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Standard) or clinical swab samples.

- DNA Extraction Kit: QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen), or other kits validated for HMW DNA [41] [42].

- Library Prep Kit: Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding Kit (RBK004) or equivalent for PacBio HiFi sequencing.

- Equipment: TissueLyser II (Qiagen) or Bead Ruptor Elite (Omni) for mechanical lysis, thermocycler, fluorometer (Qubit), Nanodrop, GridION/PromethION (ONT) or Revio/Sequel IIe (PacBio) sequencer.

Procedure

Sample Processing:

- For swab samples, centrifuge eSwab solution at 5000 g for 15 minutes. Discard supernatant and use the pellet for extraction [41].

- For mock communities, use 75 μL of thawed standard directly.

DNA Extraction (QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit):

- Add samples to PowerBead Pro Tubes.

- Add CD1 and CD2 solutions to lyse cells and remove inhibitors.

- Perform mechanical lysis on the TissueLyser II at 25 Hz for 5 minutes [41].

- Centrifuge and transfer supernatant to a new tube.

- Complete the extraction per manufacturer's instructions, including washing and elution steps.

- Elute DNA in a low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

DNA Quality Control:

- Quantity: Measure DNA concentration using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay.

- Purity: Check A260/280 and A260/230 ratios with Nanodrop. Ideal ranges are ~1.8 and ~2.0, respectively [42].

- Integrity: Assess fragment size. For long-read sequencing, use PFGE or a dPCR linkage assay to confirm the presence of HMW DNA (>20 kb) [42].

Library Preparation and Sequencing (ONT Rapid Barcoding):

- For HMW DNA, perform size selection using a Short Read Eliminator (SRE) kit, inputting > 2 μg DNA [39] [42].

- Use the Rapid Barcoding Kit (RBK004) for library construction, following the standard protocol.

- Load the library onto a FLO-MIN106D (R9.4.1) flow cell.

- Sequence on a GridION or PromethION instrument. For rapid AMR detection, sequencing can be stopped after ~2 hours, as a median time of 1.9 hours has been shown to be sufficient for reliable gene detection [41].

Bioinformatic Analysis: