Ultimate Guide to Illumina Library Preparation for Microbiome Sequencing: From 16S to Shotgun Metagenomics

This comprehensive guide details Illumina library preparation for microbiome sequencing, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Ultimate Guide to Illumina Library Preparation for Microbiome Sequencing: From 16S to Shotgun Metagenomics

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details Illumina library preparation for microbiome sequencing, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of 16S rRNA amplicon and shotgun metagenomic sequencing, provides step-by-step methodological protocols for the Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep and related workflows, offers troubleshooting strategies for common challenges like low biomass and contamination, and presents comparative validation data against emerging long-read platforms. By integrating latest research and technological comparisons, this article serves as an essential resource for designing robust, high-quality microbiome studies with clinical and translational applications.

Foundations of Microbiome Sequencing: Understanding 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Approaches

Microbiome sequencing represents a transformative approach in microbial ecology, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex microbial communities that inhabit various environments, including the human body. By leveraging high-throughput sequencing technologies, researchers can decipher the taxonomic composition and functional potential of microbiota, providing crucial insights into their roles in health and disease. The human gut microbiome, in particular, has captured widespread scientific interest due to its complex composition, functional capabilities, and significant influence on host physiology [1]. Advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized our ability to discern gut microbiota variances associated with a broad range of diseases including cancer, obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), neurological disorders, and antibiotic resistance [1].

Two principal methodological approaches dominate microbiome research: 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon sequencing and whole metagenome sequencing (WMS). While WMS provides in-depth insights into microbial communities and functional data, it requires substantial computational resources and ongoing reference database updates [1]. In contrast, 16S rRNA sequencing remains a cost-effective and efficient alternative for specific applications, particularly when using methodologies that minimize inherent biases [1]. The 16S rRNA gene contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that provide taxonomic signatures for bacterial identification and classification, making it an ideal target for amplicon-based sequencing approaches [2].

Key Applications in Human Health and Disease

Microbiome sequencing has enabled significant advances in understanding microbial ecology and its relationship to human health. By providing insights into microbial diversity, community structure, and function, these techniques have become indispensable tools for biomedical research:

- Disease Association Studies: Microbiome sequencing has revealed distinct microbial signatures associated with various disease states, enabling the identification of potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [1].

- Therapeutic Development: Understanding microbiome alterations in disease states provides opportunities for developing targeted interventions, including probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation [1].

- Personalized Medicine: Individual variations in microbiome composition can influence drug metabolism and treatment responses, paving the way for microbiome-informed personalized treatment strategies [3].

- Microbial Ecology: Beyond clinical applications, microbiome sequencing helps elucidate the complex interactions between microbial communities and their environments, including soil ecosystems and agricultural systems [2].

Workflow for Illumina Microbial Amplicon Sequencing

The Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (iMAP) protocol provides a streamlined workflow for microbiome sequencing studies. This optimized approach enables efficient library preparation from various sample types, including extracted DNA and RNA [4].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Proper sample collection and DNA extraction are critical steps that significantly impact sequencing results:

- Sample Types: The iMAP kit works with a wide variety of sample types, including nasal swabs, skin swabs, fecal samples, and wastewater [4].

- Input Requirements: Input quantity varies depending on sample source, with optimization recommended for different sample matrices [4].

- Extraction Methods: Commercial kits such as the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep kit (Zymo Research) or DNeasy PowerSoil kit (QIAGEN) provide reliable DNA extraction for diverse sample types [2] [5].

Library Preparation with iMAP Kit

The iMAP kit offers a flexible, amplicon-based library preparation solution built on the same chemistry as COVIDSeq [4]. The protocol includes:

Table 1: Key Specifications for Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Assay Time | < 9 hours |

| Hands-on Time | ~3 hours for 48 samples |

| Input Material | DNA or RNA |

| Mechanism of Action | Multiplex PCR |

| Method | Amplicon Sequencing |

| Automation Capability | Liquid handling robot(s) |

| Compatible Instruments | MiSeq, iSeq, NextSeq, NovaSeq Systems |

The library preparation process follows these key steps:

- cDNA Synthesis (for RNA samples): Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcription.

- Target Amplification: Amplify variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using target-specific primers.

- Library Construction: Tag amplified products with Illumina sequencing adapters.

- Indexing: Add dual indices to enable sample multiplexing.

- Library Quantification and Normalization: Pool libraries at equimolar concentrations.

- Sequencing: Process libraries on compatible Illumina sequencing systems.

Primer Selection and Target Regions

A critical consideration in amplicon sequencing is the selection of appropriate primer sets and target regions:

- Primer Options: The iMAP kit can be used with custom, published, or commercially available primer sets (note: primer oligos are not included in the kit) [4].

- Region Selection: Different hypervariable regions provide varying levels of taxonomic resolution. The V3-V4 region is commonly used for bacterial community analysis [5].

- Validated Protocols: Illumina provides tested protocols for various pathogens including Chikungunya, Dengue, Mpox, RSV, and Zika, with customer-demonstrated protocols available for numerous additional targets [4].

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Target Regions and Applications

| Target Region | Read Length | Taxonomic Resolution | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| V4 | 250-300 bp | Genus to Family Level | General community profiling |

| V3-V4 | 400-500 bp | Genus Level | Standard gut microbiome studies |

| V1-V3 | 500-600 bp | Species to Genus Level | Detailed taxonomic classification |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | ~1500 bp | Species Level | High-resolution studies [5] |

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

Following sequencing, raw data undergoes a series of computational processing steps to generate biologically meaningful results:

Primary Data Processing

The initial stage involves quality control and feature table construction:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to corresponding samples based on their unique dual indices.

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality sequences and sequencing artifacts using tools like DADA2 or DEBLUR [3] [5].

- Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) Generation: Denoise sequences to identify biological true sequence variants.

- Chimera Removal: Filter out artificial chimeric sequences formed during PCR amplification.

Taxonomic Classification and Diversity Analysis

Following data processing, taxonomic assignment and ecological analyses are performed:

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs against reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes, RDP) using classifiers like QIIME2 or mothur [1].

- Alpha Diversity Analysis: Calculate within-sample diversity metrics including richness, evenness, and phylogenetic diversity [3].

- Beta Diversity Analysis: Assess between-sample differences using distance metrics (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, Weighted Unifrac) and visualization methods (PCoA, NMDS) [5].

Key Diversity Metrics and Their Interpretation

A comprehensive analysis of microbial communities should include multiple alpha diversity metrics to capture different aspects of community structure [3]:

Table 3: Essential Alpha Diversity Metrics for Microbiome Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Biological Interpretation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | Number of different species in a sample | Highly dependent on sequencing depth; requires careful normalization |

| Evenness/Dominance | Berger-Parker, Simpson, ENSPIE | Distribution of abundances among species | Berger-Parker has clear interpretation (proportion of most abundant taxon) |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Faith's PD | Evolutionary relationships within community | Incorporates phylogenetic distances between taxa |

| Information Theory | Shannon, Pielou, Brillouin | Combined measure of richness and evenness | Most commonly reported but has complex mathematical foundation |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of microbiome sequencing requires carefully selected reagents and computational tools:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Illumina Microbiome Sequencing

| Reagent/Tool | Manufacturer/Developer | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep | Illumina | Library preparation | Flexible workflow for DNA/RNA targets; <9 hr assay time |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | QIAGEN | DNA extraction | Optimized for difficult samples; inhibitor removal |

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep | Zymo Research | DNA extraction | High-yield purification from complex samples |

| DRAGEN Targeted Microbial App | Illumina | Bioinformatic analysis | Pre-loaded targets for simplified analysis |

| SILVA Database | SILVA NRG | Taxonomic reference | Curated database of ribosomal RNA sequences |

| QIIME 2 | QIIME 2 Development Team | Analysis pipeline | Integrated workflow for microbiome data analysis |

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust microbiome studies require careful experimental design:

- Sample Size and Power: Include sufficient biological replicates to account for individual variability and achieve statistical power.

- Controls: Incorporate extraction controls, PCR negatives, and positive controls (mock communities) to monitor technical variability and potential contamination [1].

- Batch Effects: Process samples in randomized order to minimize batch effects introduced during library preparation and sequencing.

- Metadata Collection: Document comprehensive sample metadata including collection method, storage conditions, and processing details.

Methodological Comparisons

Different sequencing approaches offer complementary strengths:

- Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing: While Illumina provides high accuracy and throughput, long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enable full-length 16S rRNA sequencing, potentially improving species-level resolution [2] [5].

- Region Selection Impact: The choice of 16S rRNA region significantly affects taxonomic resolution, with different regions recommended for specific sample types [1].

- Data Processing Methods: Alternative approaches to read processing, such as direct joining (DJ) of paired-end reads rather than merging (ME), can improve retention of taxonomic information [1].

Microbiome sequencing using Illumina platforms represents a powerful approach for investigating microbial communities in human health and disease. The Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep kit provides a standardized, scalable solution for generating high-quality sequencing libraries from diverse sample types. By following optimized protocols and implementing comprehensive bioinformatic analyses, researchers can obtain robust insights into microbial community structure and dynamics. As reference databases expand and analytical methods refine, microbiome sequencing will continue to enhance our understanding of host-microbe interactions and enable development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

The choice between 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and whole-genome shotgun metagenomics represents a critical decision point in the design of microbiome studies. This application note provides a structured comparison of these two foundational sequencing technologies, focusing on their methodological principles, analytical outputs, and applications within Illumina-based microbiome research. We detail experimental protocols from recent studies, present quantitative performance comparisons, and provide guidance on technology selection based on research objectives, sample type, and resource constraints. Framed within the context of library preparation for Illumina sequencing, this resource equips researchers with the information needed to optimize their microbial profiling strategies for diverse biomedical and biopharmaceutical applications.

Next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling comprehensive profiling of complex microbial communities without the need for cultivation. The two predominant approaches—16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing—offer complementary insights with distinct applications and limitations [6] [7]. While 16S sequencing targets a specific phylogenetic marker gene for taxonomic identification, shotgun sequencing randomly fragments all genomic DNA in a sample, providing a more comprehensive view of the microbial community including functional potential [8]. Understanding the technical specifications, performance characteristics, and practical considerations of each method is essential for designing robust microbiome studies, particularly in the context of Illumina library preparation protocols which form the foundation of reproducible microbial profiling.

Methodological Principles

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing leverages the highly conserved 16S ribosomal RNA gene present in all bacteria and archaea. This targeted approach amplifies and sequences specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) through PCR, followed by clustering of sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) for taxonomic classification [7] [9]. The method relies on conserved primer binding sites flanking variable regions that provide taxonomic discrimination power. Common variable region choices include V3-V4 and V4, though optimal selection depends on the microbial community under study [10].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing takes an untargeted approach by fragmenting all DNA in a sample into short fragments that are sequenced randomly across all genomes present. These sequences are then assembled into contigs or aligned directly to reference databases, allowing for taxonomic profiling at higher resolution and simultaneous assessment of functional gene content [7] [8]. This method captures all genomic DNA regardless of taxonomic origin, enabling identification of bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms in a single assay.

Performance Comparison in Controlled Studies

Recent comparative studies using matched samples demonstrate significant differences in microbial community characterization between these technologies. A 2024 study comparing both methods on 156 human stool samples from healthy controls, advanced colorectal lesion patients, and colorectal cancer cases found that 16S sequencing detects only part of the gut microbiota community revealed by shotgun sequencing [6]. The 16S abundance data was sparser and exhibited lower alpha diversity, with particularly pronounced differences at lower taxonomic ranks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of 16S rRNA vs. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Performance Metric | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level (sometimes species) [7] | Species and strain level [7] [8] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [7] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Protozoa [6] [8] |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect prediction only (e.g., PICRUSt) [7] | Direct assessment of functional genes and pathways [7] [8] |

| Alpha Diversity | Lower values observed [6] | Higher diversity measures [6] [11] |

| Sensitivity to Rare Taxa | Limited detection of low-abundance species [12] | Enhanced detection of rare and low-abundance species [12] [11] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD [7] | Starting at ~$150 USD (varies with depth) [7] |

| Host DNA Contamination Sensitivity | Low (due to targeted amplification) [7] | High (requires depletion strategies or deep sequencing) [7] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to intermediate [7] | Intermediate to advanced [7] [8] |

A 2021 chicken gut microbiome study provided quantitative support for these observations, demonstrating that shotgun sequencing identified a statistically significant higher number of taxa compared to 16S sequencing, particularly among less abundant genera [12]. When comparing the fold changes of genera abundances between different gastrointestinal tract compartments, shotgun sequencing identified 256 statistically significant differences, while 16S sequencing detected only 108, with 152 changes uniquely identified by shotgun sequencing [12].

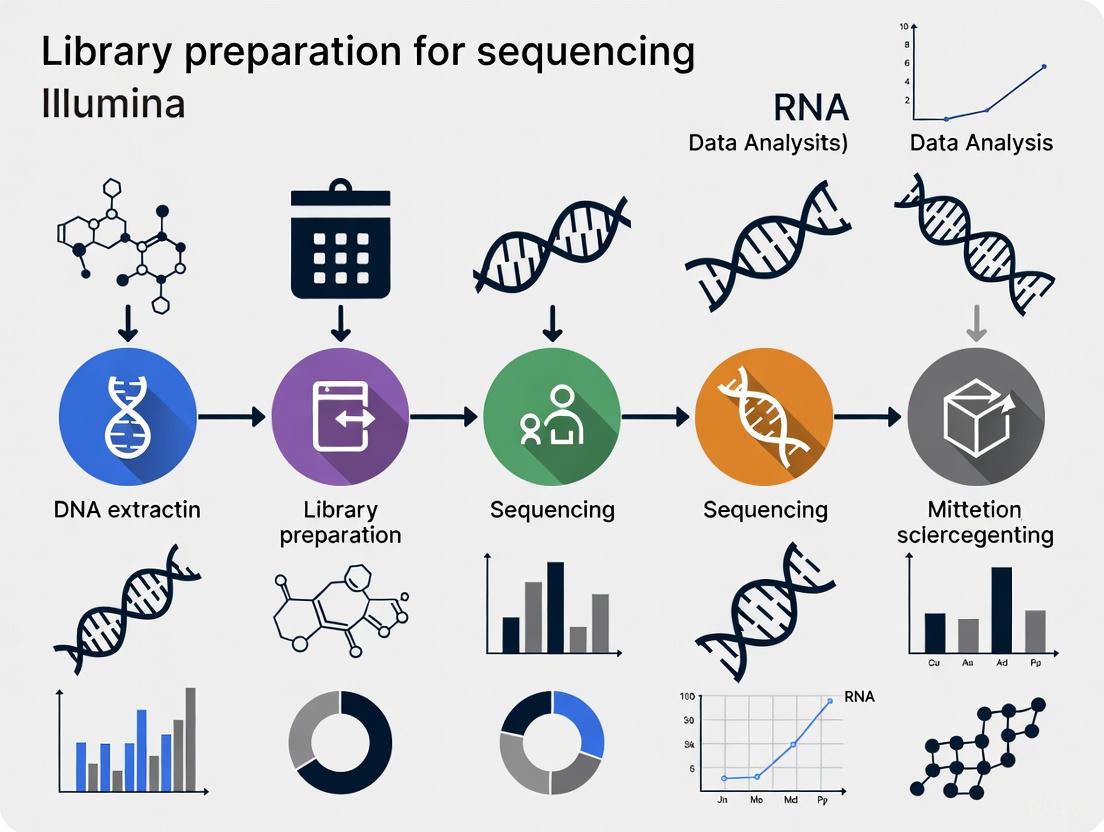

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows for 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing. Both methods begin with sample collection and DNA extraction, then diverge in library preparation approaches, resulting in different analytical outputs and resolution.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (stool, tissue, swabs, environmental) using sterile techniques. For human stool samples, immediate freezing at -20°C or -80°C is recommended to preserve microbial composition [6]. Tissue samples may require specialized stabilization buffers.

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits optimized for microbial lysis (e.g., NucleoSpin Soil Kit, Dneasy PowerLyzer Powersoil kit) [6]. Include mechanical lysis steps (bead beating) to ensure disruption of tough bacterial cell walls. Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and assess quality via spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280 ~1.8-2.0).

Library Preparation for Illumina Sequencing

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) using region-specific primers with Illumina adapter overhangs. Reaction conditions typically include: 25-35 cycles, annealing temperature 50-60°C, and high-fidelity polymerase to minimize amplification errors [6] [9].

- Amplicon Cleanup: Purify PCR products using magnetic bead-based cleanups (e.g., AMPure XP beads) to remove primers, dimers, and contaminants.

- Index PCR: Add dual indices and sequencing adapters using a limited-cycle PCR program (typically 8 cycles) to enable multiplexing.

- Library Normalization and Pooling: Quantify libraries by fluorometry, normalize to equal concentration, and pool multiplexed samples. Perform size verification via capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer).

- Sequencing: Load pooled library onto Illumina platforms (MiSeq, NextSeq 1000/2000, or NovaSeq) with 2×250bp or 2×300bp paired-end chemistry for adequate overlap [9].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples based on dual indices.

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality reads, trim adapters, and filter based on expected errors.

- Sequence Variant Inference: Use DADA2 [6] [13] or Deblur to resolve amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or cluster with UPARSE [13] into OTUs at 97% similarity.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify sequences against reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes, RDP) using classifiers like Naive Bayes or BLAST [6] [10].

- Diversity Analysis: Calculate alpha and beta diversity metrics using QIIME 2, mothur, or phyloseq.

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Protocol

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Follow standardized collection protocols appropriate for sample type. For low-biomass samples, consider extraction methods that maximize yield while minimizing contamination.

- DNA Extraction and QC: Use kits that yield high-molecular-weight DNA (e.g., MagAttract PowerSoil DNA KF Kit). Assess DNA integrity via pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer. DNA input recommendations range from 1ng-1μg depending on application.

Illumina Library Preparation

- DNA Fragmentation: Fragment genomic DNA to ~350-800bp using acoustic shearing (Covaris) or enzymatic fragmentation (Nextera tagmentation) [8].

- Size Selection: Clean and select appropriately sized fragments using magnetic beads (SPRIselect) to optimize library fragment distribution.

- Library Assembly: Perform end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using Illumina-compatible reagents. For low-input samples, incorporate whole-genome amplification steps.

- Library Amplification: Enrich adapter-ligated DNA using limited-cycle PCR (typically 4-10 cycles) with index-containing primers.

- Library QC and Normalization: Quantify libraries by qPCR (for accurate molarity) and assess size distribution by capillary electrophoresis. Normalize libraries to 4nM based on qPCR values.

- Sequencing: Pool normalized libraries and sequence on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq preferred for high throughput) with 2×150bp configuration. Target 10-50 million reads per sample depending on complexity and host DNA contamination [11].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Quality Control and Host Depletion: Remove low-quality reads and filter host-derived sequences (e.g., human genome) using Bowtie2 or BWA [6] [11].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Align reads to reference databases (NCBI RefSeq, GTDB, UHGG) using Kraken2 [11] or MetaPhlAn, or perform assembly-based analysis with metaSPAdes/MEGAHIT followed by binning into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [8].

- Functional Annotation: Align reads to functional databases (KEGG, eggNOG, CAZy) using HUMAnN2 or directly annotate predicted genes from MAGs.

Protocol Variations for Challenging Samples

Museum and Archival Specimens: For degraded DNA from museum specimens (e.g., fluid-preserved specimens), employ modified phenol-chloroform extraction protocols with additional purification steps to remove inhibitors [11]. Consider lower sequencing depth requirements for 16S sequencing compared to shotgun approaches with such suboptimal samples.

Low-Microbial-Biomass Samples: For samples with high host-to-microbial DNA ratios (e.g., skin swabs, tissue biopsies), implement host DNA depletion methods (e.g., selective lysis, enzymatic degradation) or increase sequencing depth for shotgun approaches [7]. 16S sequencing may be preferred for such sample types due to targeted amplification.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Microbiome Sequencing

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | NucleoSpin Soil Kit, Dneasy PowerLyzer Powersoil kit, MagAttract PowerSoil DNA KF Kit [6] [11] | Microbial DNA isolation from diverse sample types | Lysis efficiency varies; bead beating improves Gram-positive bacterial recovery |

| 16S Amplification Primers | 341F/806R (V3-V4), 27F/338R (V1-V2), other region-specific primers [6] [10] | Target-specific amplification of 16S variable regions | Primer selection impacts taxonomic resolution and bias; V3-V4 offers general utility |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera XT, NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit [11] [9] | Fragment processing and adapter ligation for Illumina sequencing | Input DNA requirements vary; some kits optimized for low-input samples |

| Taxonomic Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP (16S); NCBI RefSeq, GTDB, UHGG (shotgun) [6] [7] | Taxonomic classification of sequencing reads | Database choice impacts classification accuracy and resolution |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | QIIME 2, mothur (16S); MetaPhlAn, HUMAnN, Kraken2 (shotgun) [7] [8] | End-to-end processing of raw sequencing data | Pipeline selection depends on expertise and analysis goals |

| Mock Communities | ZymoBIOMICS, ZIEL-II Mock Community [13] [10] | Method validation and quality control | Essential for benchmarking laboratory and computational methods |

Applications and Limitations in Research Contexts

Technology Selection Guidelines

Choose 16S rRNA Sequencing When:

- Research budget is constrained and sample number is large [7]

- Primary research question focuses on bacterial/archaeal community structure at genus level [6]

- Sample types have high host DNA contamination (e.g., tissue biopsies, skin swabs) [7]

- Study aims to compare with existing 16S datasets or conduct meta-analyses

- Computational resources or bioinformatics expertise are limited [7]

Choose Shotgun Metagenomics When:

- Species- or strain-level taxonomic resolution is required [7] [8]

- Research questions extend beyond taxonomy to functional potential [7] [8]

- Comprehensive profiling of all microbial domains (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea) is needed [6]

- Sample material is precious and allows for only one sequencing approach

- Detection of low-abundance or rare taxa is critical [12] [11]

- Study aims to generate metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [14]

Integrated and Emerging Approaches

Hybrid Study Designs: Some studies employ a cost-effective strategy where 16S sequencing is used for all samples, with shotgun sequencing applied to a representative subset to enable functional insights and validate 16S-based observations [7].

Shallow Shotgun Sequencing: An emerging approach that sequences at lower depth (1-5 million reads/sample) at a cost comparable to 16S sequencing while maintaining species-level taxonomic profiling capability, though with limited functional analysis depth [7].

Long-Read Metagenomics: Third-generation sequencing platforms (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) generate long reads that improve metagenome assembly, resolve repetitive regions, and enable more complete genome reconstruction, though with higher error rates that require computational correction [14].

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Between 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing. This flowchart guides researchers through key considerations including research questions, required resolution, sample type, and resource constraints.

Both 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics offer powerful approaches for microbial community profiling, each with distinct advantages and limitations. 16S sequencing remains a cost-effective method for large-scale taxonomic surveys of bacterial and archaeal communities, particularly when studying sample types with high host DNA content or when research budgets are constrained. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics provides superior taxonomic resolution, enables strain-level discrimination, and affords direct access to functional genetic elements across all microbial domains, at a higher cost and computational requirement.

The choice between these technologies should be guided by specific research questions, sample types, and available resources. As sequencing costs continue to decline and computational methods improve, shotgun metagenomics is becoming increasingly accessible for routine microbiome studies. However, 16S sequencing maintains particular utility for massive sample sizes, longitudinal studies with frequent sampling, and when comparing with existing 16S datasets. By understanding the technical specifications, performance characteristics, and practical considerations outlined in this application note, researchers can make informed decisions that optimize their microbiome study designs within the framework of Illumina library preparation and sequencing.

The integrity of microbiome sequencing data is fundamentally rooted in the initial steps of the experimental workflow. For Illumina sequencing, which relies on high-accuracy short reads generated via Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) [15], the quality of the final library is critically dependent on pre-analytical conditions. Variations in sample collection, storage parameters, and DNA extraction methodologies can introduce significant biases, impacting downstream taxonomic profiling and functional analysis. This application note details standardized protocols and key considerations for these foundational stages to ensure the generation of robust and reproducible data for microbiome research.

Sample Collection and Storage

The goal of sample collection and storage is to preserve the in vivo microbial composition and integrity from the moment of collection until nucleic acid extraction.

Storage Temperature and Duration

The gold standard for long-term sample storage is -80°C. However, recent evidence suggests that domestic freezers (typically -18°C to -20°C) provide a viable and accessible alternative for temporary storage, facilitating large-scale at-home collection initiatives.

Table 1: Effect of Domestic Freezer Storage on Microbiome Integrity

| Storage Duration | Alpha Diversity | Beta Diversity | Microbial Community Structure | AMR Gene Profiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Week | No significant change [16] | No significant change [16] | Stable, no significant deviations [16] | Consistent detection [16] |

| 2 Months | No significant change [16] | No significant change [16] | Stable, no significant deviations [16] | Consistent detection [16] |

| 6 Months | No significant change [16] | No significant change [16] | Stable, no significant deviations [16] | Consistent detection [16] |

A pivotal study utilizing shotgun metagenome sequencing demonstrated that stool samples stored in domestic freezers for up to six months showed no significant degradation or variation in microbial composition, alpha diversity, or beta diversity [16]. Furthermore, inter-individual differences remained the strongest factor influencing microbial community structure, underscoring that the biological signal is preserved over temporal storage effects [16].

Critical Considerations for Neonatal and Low-Biomass Samples

Sample collection is particularly critical for low-biomass samples, such as neonatal stool. A comparative evaluation of DNA extraction protocols highlighted that DNA yield drops most significantly within the first 24 hours of storage post-collection [17]. Therefore, same-day processing is highly recommended to maximize yield and minimize bias. When immediate processing is not feasible, the use of charcoal swabs has been shown to enable DNA recovery even after 6 weeks of storage at 4°C [17].

DNA Extraction Protocols

The DNA extraction method is a major source of bias in microbiome studies, impacting DNA yield, quality, and the representation of microbial communities, especially from complex matrices like stool.

Comparative Performance of Extraction Kits

The choice of DNA extraction kit significantly impacts downstream results. Bead-beating-based kits are essential for effectively lysing tough microbial cell walls, particularly Gram-positive bacteria.

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Extraction Kits for Neonatal Stool

| Extraction Kit | Relative DNA Yield | Key Findings and Performance | Suitability for Illumina |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro | High [17] | Longer sequencing read N50; faster processing time; highest yields with fresh processing [17] | Excellent |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep | High [17] | Similar yield to PowerSoil; performance declines with storage [17] | Good |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini | Negligible [17] | Produced negligible yields across conditions [17] | Not Recommended |

An evaluation on neonatal stool samples concluded that bead-beating kits (PowerSoil and ZymoBIOMICS) consistently and significantly outperformed the non-bead-beating QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini kit [17]. Among the bead-beating kits, the PowerSoil kit demonstrated a potential advantage by producing longer read N50 values and having a shorter processing time, making it particularly suitable for workflows in resource-limited settings [17].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation Workflow

The journey from sample to sequencing library involves several critical steps to ensure that the final data is of high quality. The following workflow outlines the key stages for preparing DNA for Illumina sequencing, based on the manufacturer's typical workflow [18].

DNA Fragmentation and End Repair

The first step in library preparation for Illumina systems is fragmentation of DNA to a desired size, typically 200-600 bp [18].

- Fragmentation Methods: The two primary methods are:

- Mechanical Shearing: Methods like focused acoustics (Covaris) provide unbiased fragmentation and consistent fragment sizes with minimal sample loss and contamination risk [18].

- Enzymatic Digestion: This approach uses enzyme cocktails to cleave DNA and is advantageous for automated workflows due to lower DNA input requirements and the ability to perform reactions in a single tube [18].

- End Repair and A-Tailing: After fragmentation, the resulting DNA fragments have mixed end types. They are processed to create blunt ends, 5' phosphorylation, and 3' A-tailing. This is a critical step to prepare the fragments for ligation with Illumina's sequencing adapters [18].

Adapter Ligation and Quality Control

- Adapter Ligation: Adapters are short, double-stranded oligonucleotides that are ligated to both ends of the A-tailed DNA fragments. These adapters contain the sequences that allow the library fragments to bind to the flow cell and serve as priming sites for the sequencing reactions [18].

- Final Library QC: Before sequencing, the prepared library must undergo rigorous quality control. This includes quantification using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) and assessment of size distribution and integrity via electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent TapeStation or Bioanalyzer) [19]. A quality score (Q score) above 30 is generally considered good quality for most sequencing experiments, representing an error rate of 1 in 1000 (99.9% accuracy) [15] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Microbiome DNA Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Bead-Beating DNA Extraction Kit | Efficiently lyses diverse microbial cells; purifies DNA | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro, ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep [17] |

| DNA Fragmentation Reagents | Fragments DNA to optimal size for library prep | Covaris AFA reagents, NEBNext dsDNA Fragmentase [18] |

| Library Preparation Kit | End-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, library PCR | Illumina DNA Prep kits [18] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Quantifies DNA and assesses fragment size distribution | Thermo Scientific NanoDrop, Agilent TapeStation/Bioanalyzer [19] |

| Indexing Primers (Barcodes) | Enables multiplexing of samples | Illumina CD Indexes, IDT for Illumina UD Indexes [18] |

The reliability of Illumina-based microbiome sequencing data is contingent upon a rigorously controlled pre-analytical phase. Key recommendations emerge from current research:

- Sample Storage: Domestic freezer storage (-20°C) is a valid and accessible method for preserving stool microbiome integrity for up to six months, facilitating broader participant recruitment [16].

- DNA Extraction: Bead-beating-based DNA extraction kits, such as the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro, are paramount for achieving high DNA yield and quality, especially from challenging sample types like neonatal stool [17].

- Timing: For the most accurate representation of the in vivo state, particularly in low-biomass contexts, same-day sample processing is ideal, as DNA yield and quality can degrade significantly within 24 hours [17].

Adherence to these standardized protocols in sample collection, storage, and DNA extraction will significantly enhance the quality and reproducibility of microbiome data, thereby strengthening the conclusions drawn from Illumina sequencing research.

Microbiome research has dramatically advanced our understanding of microbial communities in human health and disease. However, the accuracy and reproducibility of this research are challenged by numerous sources of variation that can compromise data quality from sample collection through data analysis [20]. Recognizing and controlling these variables is crucial for generating reliable, clinically meaningful insights, particularly in the context of Illumina sequencing library preparation which forms the foundation of many microbiome studies.

This document outlines the major sources of variation in microbiome research and provides detailed protocols to minimize their impact, ensuring high-quality data for research and diagnostic applications.

Variability in microbiome research arises from multiple technical and biological factors. The table below summarizes these key sources and their impact on data quality.

Table 1: Key Sources of Variation in Microbiome Research and Their Impacts

| Source of Variation | Stage of Workflow | Impact on Data Quality | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection Method [20] | Pre-analytical | High risk of contamination and microbial composition shifts | Standardize tools, timing, and storage; use sterile collection kits |

| DNA Extraction & Library Prep [21] | Analytical | Bias in microbial representation due to lysis efficiency and PCR artifacts | Optimize and standardize protocols; include quality control checks |

| Sequencing Technology & Depth [22] [21] | Analytical | Incomplete profiling, missed rare taxa, and technical artifacts | Select appropriate sequencing method; ensure sufficient sequencing depth |

| Bioinformatic Analysis [22] [21] | Post-analytical | Inaccurate taxonomic assignment and functional profiling | Use standardized pipelines; apply careful statistical modeling |

| Host & Environmental Factors [20] | Biological | High inter-individual variability obscuring true signals | Collect comprehensive metadata; standardize collection times |

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Variation

Standardized Sample Collection and Storage Protocol

Proper sample collection is the first and most critical step in minimizing variation.

Materials:

- Sterile collection tools (e.g., swabs, sterile containers)

- Standardized storage buffers or stabilization solutions

- Cryogenic vials and labels

- -80°C freezer or liquid nitrogen for long-term storage

Procedure:

- Pre-collection Planning: Define and document all collection parameters including time of day, recent medication use (especially antibiotics), and dietary intake [20].

- Sample Acquisition:

- Use the same brand and type of sterile collection device for all samples in a study.

- For stool samples, collect from multiple sites within the specimen to account for heterogeneity.

- For swabs, use a standardized rolling technique and pressure.

- Sample Preservation:

- Immediately place samples in appropriate preservation buffer or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen.

- Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles.

- Document exact storage time and conditions.

- Storage:

- Store samples at -80°C within 2 hours of collection.

- Maintain consistent storage conditions for all samples in a study.

- Use organized systems to prevent sample degradation or misidentification.

Quality Control:

- Include sample collection blanks to monitor contamination.

- Document any deviations from the standard protocol.

- Record storage time and conditions for each sample.

Optimized DNA Extraction and Library Preparation for Illumina Sequencing

This protocol utilizes the Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) kit, which enables various microbial research applications including bacterial and fungal identification [23].

Materials:

- Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep Kit (Catalog #: 20097857) [23]

- Custom or commercially available primer sets (not included in kit)

- DNA extraction kit with bead-beating capability

- Qubit fluorometer or similar DNA quantification system

- Thermal cycler

- Agilent TapeStation or Bioanalyzer for quality control

Procedure: A. DNA Extraction:

- Cell Lysis: Use mechanical lysis (bead beating) combined with enzymatic lysis to ensure maximal disruption of diverse microbial cell walls [21].

- DNA Purification: Follow manufacturer's protocol for DNA binding and washing steps.

- DNA Quantification: Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) rather than spectrophotometry for accuracy.

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis systems.

B. Library Preparation using IMAP Kit:

- Amplification Setup:

- Set up multiplexed PCR reactions using the IMAP kit components.

- Use 1-10 ng of input DNA, varying based on sample source [23].

- Include negative controls to detect contamination.

- PCR Conditions:

- Follow the IMAP thermal cycling protocol: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 25-35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min [23].

- Library Cleanup:

- Purify amplified products using the provided cleanup beads.

- Elute in the provided resuspension buffer.

- Library Normalization and Pooling:

- Quantify each library using fluorometric methods.

- Normalize libraries to equal concentration.

- Pool libraries according to the experimental design (up to 96 samples per run).

- Quality Control:

- Verify library size distribution using TapeStation or Bioanalyzer.

- Quantify the final pooled library to ensure optimal loading concentration.

Troubleshooting:

- If amplification is low, increase input DNA quantity or PCR cycles (up to 35 cycles).

- If primer dimers are present, optimize primer concentrations or increase cleanup stringency.

- If library yield is low, check DNA quality and quantity inputs.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete microbiome analysis workflow, highlighting key control points for managing variation.

Diagram 1: Microbiome analysis workflow with quality control points. Key variation control points are highlighted in each phase.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential reagents and materials for robust microbiome library preparation and analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiome Library Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Product | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep [23] | Library preparation for amplicon sequencing | Illumina IMAP Kit (20097857) | Flexible for DNA/RNA; requires separate primer purchase; 3 hr hands-on time |

| 16S rRNA Primers [21] | Amplification of bacterial taxonomic marker | Custom or published primer sets | Target hypervariable regions (V3-V4); avoid primer degeneracies to reduce bias |

| DNA Extraction Kit with Bead Beating [21] | Microbial cell lysis and DNA purification | Various commercial kits | Must include mechanical lysis for Gram-positive bacteria; minimize contamination |

| Library Quantification Kits | Accurate library quantification for pooling | Fluorometric quantification kits | Avoid spectrophotometric methods; ensure accurate normalization |

| Quality Control Assays | Assess DNA and library quality | Automated electrophoresis systems | Verify fragment size distribution; detect adapter dimers or degradation |

Understanding and controlling for sources of variation throughout the microbiome research workflow is essential for producing high-quality, reproducible data. By implementing standardized protocols from sample collection through bioinformatic analysis, researchers can minimize technical noise and enhance biological discovery. The protocols and guidelines provided here offer a framework for robust microbiome studies using Illumina sequencing technologies, ultimately supporting more reliable research outcomes and potential diagnostic applications.

Microbiome profiling represents a critical first step in determining the composition and function of bacterial and protist organisms within a biome and how they interact with and influence their environment [24]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized this field, enabling high-throughput, culture-independent analysis of microbial communities. Among these technologies, Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry has emerged as a gold standard for microbiome profiling due to its exceptional accuracy, high throughput, and cost-effectiveness [25] [26]. This application note details the principles of Illumina sequencing chemistry and its specific advantages for microbiome research, providing detailed protocols for library preparation within the context of a broader thesis on library preparation for Illumina microbiome sequencing.

Illumina Sequencing Chemistry and Technology

Sequencing-by-Synthesis Fundamentals

Illumina's sequencing technology is based on the sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry, a robust method that utilizes fluorescently-labeled, reversible-terminator nucleotides [15]. During each sequencing cycle, a single nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA strand by DNA polymerase. Each nucleotide is tagged with a fluorescent dye and a reversible terminator that blocks further extension. After incorporation, the flow cell is imaged to determine the identity of the base at each cluster, followed by cleavage of both the fluorescent dye and the terminator, allowing the next cycle to begin [15]. This process generates millions of parallel reads in a massively parallel fashion.

Quality Metrics and Accuracy

A key strength of Illumina sequencing is its high base-calling accuracy. Quality is measured by Phred-scaled quality scores (Q-scores), where the probability of an incorrect base call is defined by the equation Q = -10log₁₀(e), with 'e' representing the estimated error probability [15]. Illumina chemistry consistently delivers a vast majority of bases with Q30 scores or higher, translating to a base call accuracy of 99.9% or greater [15]. This high accuracy is paramount for distinguishing true biological variants from sequencing errors in microbiome data. When compared to emerging platforms like the Ultima Genomics UG 100, Illumina's NovaSeq X Series demonstrates superior performance, resulting in 6× fewer single-nucleotide variant (SNV) errors and 22× fewer indel errors when assessed against the full NIST v4.2.1 benchmark [27].

Recent Technological Advancements

Illumina continues to innovate with new technologies that enhance microbiome profiling. The newly announced Constellation Mapped Read Technology, slated for commercial release in the first half of 2026, builds upon standard SBS chemistry to unlock long-range genomic insights with a streamlined workflow [28]. This technology uses long, unfragmented DNA applied directly to the flow cell, eliminating manual library preparation and enabling accurate mapping of homologous or repetitive genomic regions that are often challenging for short-read technologies [28]. This promises to resolve complex variant types relevant to microbial genomics.

Advantages for Microbiome Profiling

The combination of high accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness makes Illumina sequencing particularly advantageous for microbiome studies, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Illumina Sequencing for Microbiome Profiling

| Advantage | Technical Basis | Impact on Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| High Accuracy | Q30 scores (99.9% accuracy) for the vast majority of bases [15]. | Reduces false positives in variant calling; enables confident detection of rare taxa and subtle community shifts [24] [27]. |

| High Throughput | Capacity to generate hundreds of millions to billions of reads per run. | Enables saturating or near-saturating analysis of complex samples (e.g., soil) and large cohort studies [24] [29]. |

| Low Per-Sample Cost | Highly multiplexed sequencing with combinatorial barcoding [24]. | Makes deep sequencing economical for hundreds of samples, facilitating robust statistical analysis [24]. |

| Short-Read Length | Paired-end reads (e.g., 2x300 bp) that overlap for short amplicons [24] [25]. | Ideal for sequencing taxonomically informative variable regions (V3-V4, V4, V6) of the 16S rRNA gene with high fidelity [24] [25]. |

| Standardized Workflows | Optimized kits like Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) and automated analysis [23] [29]. | Simplifies library prep, reduces hands-on time, and ensures reproducibility across laboratories. |

Comparative studies consistently validate the performance of Illumina platforms. A 2025 study comparing sequencing platforms for 16S rRNA profiling of respiratory microbiomes found that Illumina NextSeq, targeting the V3-V4 region, captured greater species richness compared to Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [25]. Similarly, a 2025 evaluation of soil microbiome profiling confirmed that while long-read platforms (PacBio, ONT) offer superior species-level resolution, Illumina technology reliably clusters samples based on soil type, demonstrating its robustness for community-level analyses [30].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing (V6 Region)

This protocol, adapted from a seminal 2010 study, is ideal for low-cost, high-throughput microbiome profiling [24].

Primer Design:

- Target: V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene (amplicon size ~110-130 bp).

- Forward Primer (E. coli 967-985): 5'-CAACGCGARGAACCTTACC-3'

- Reverse Primer (E. coli 1078-1061): 5'-ACAACACGAGCTGACGAC-3'

- Combinatorial Barcoding: Incorporate unique sequence tags at the 5' end of both the forward and reverse PCR primers. This allows hundreds of samples to be multiplexed with far fewer primers than single-end tagging [24].

PCR Amplification:

- Cycling Conditions:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 45 sec

- Annealing: 57°C for 45 sec

- Extension: 72°C for 45 sec

- Number of Cycles: 25

- Validation: Test primers on control organisms (e.g., Lactobacillus iners, Gardnerella vaginalis) to ensure equivalent amplification [24].

Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Pool purified PCR products in equimolar ratios.

- Sequence using an Illumina paired-end protocol (e.g., 2x75 bp) to generate overlapping reads that cover the entire V6 region [24].

Shotgun Metagenomics for Soil Microbiomes

This end-to-end workflow is designed for comprehensive, unbiased characterization of complex microbial communities, such as soil [29].

DNA Extraction:

- Use inhibitor-removal kits designed for environmental samples (e.g., PerkinElmer's chemagic 360 instrument with specialized chemistry) to isolate pure, high-quality DNA [29].

Library Preparation:

- Use the Illumina DNA Prep library preparation kit. This method fragments DNA and attaches adapters in a single, streamlined workflow, avoiding the amplification biases of amplicon sequencing [29].

Sequencing & Analysis:

- Sequence on a high-throughput platform like the NextSeq 550.

- Analyze data using software apps on Illumina's BaseSpace Sequence Hub for species identification and functional profiling [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core sequencing-by-synthesis process that underlies these protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of Illumina-based microbiome profiling relies on a suite of specialized reagents and kits. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Illumina Microbiome Sequencing

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) [23] | An amplicon-based library prep kit for DNA and RNA samples. | Enables various applications including viral WGS, AMR analysis, and bacterial/fungal ID. Offers a hands-on time of ~3 hours for 48 samples [23]. |

| Illumina DNA Prep [29] | A library preparation kit for metagenomic shotgun sequencing. | Used in automated workflows for unbiased DNA sequencing from complex samples like soil and stool [29]. |

| Combinatorial Indexed PCR Primers [24] | PCR primers with unique sequence tags for sample multiplexing. | Critical for high-throughput studies; tagging both ends of amplicons reduces the number of primers required [24]. |

| QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel [25] | A panel for targeted amplification of 16S rRNA variable regions. | Provides a standardized, ISO-certified system for 16S library prep, including positive controls [25]. |

| PhiX Control Kit [15] | A sequencing control with a known genome. | Serves as an in-run control for monitoring sequencing accuracy, cluster density, and base calling on the flow cell [15]. |

Illumina sequencing chemistry, with its foundation in high-accuracy SBS technology, provides a powerful and versatile platform for microbiome profiling. Its key advantages—including exceptional base-call accuracy, high throughput, and cost-effectiveness—make it ideally suited for both targeted 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and unbiased shotgun metagenomics. As evidenced by recent comparative studies, Illumina platforms consistently deliver robust and reproducible data for microbial community analysis, from clinical specimens to complex environmental samples like soil. The availability of standardized, streamlined workflows and ongoing technological innovations, such as the forthcoming Constellation technology, ensures that Illumina will remain at the forefront of tools empowering researchers and drug development professionals to unravel the complexities of microbial ecosystems.

Step-by-Step Protocols: Implementing Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep and Shotgun Sequencing

Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) is a flexible, amplicon-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation kit designed for a wide spectrum of public health surveillance and microbial research applications [23]. Built on the robust chemistry of the COVIDSeq assay, this kit enables versatile pathogen characterization, including viral whole-genome sequencing, antimicrobial resistance marker analysis, and bacterial and fungal identification [23]. The streamlined workflow supports both DNA and RNA inputs from diverse sample sources, such as cultures, swabs, and wastewater, making it a powerful tool for comprehensive microbiome and pathogen research [23]. This application note details the kit components, specifications, and experimental protocols to guide researchers in implementing this technology.

Kit Specifications and Components

Key Specifications

The IMAP kit is designed for efficiency and flexibility, with a workflow that accommodates a variety of experimental needs. Its core specifications are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Specifications of the Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep Kit

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Assay Time | < 9 hours [23] |

| Hands-on Time | ~3 hours for 48 samples [23] |

| Input Quantity | Varies depending on sample source [23] |

| Nucleic Acid Input | DNA, RNA, or both (purified separately) [23] [31] |

| Method | Amplicon Sequencing [23] |

| Mechanism of Action | Multiplex PCR [23] |

| Automation Capability | Liquid handling robot(s) [23] |

| Variant Classes Detected | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) [23] |

Compatible Sequencing Instruments

Libraries prepared with the IMAP kit are compatible with nearly all Illumina sequencing systems, providing significant platform flexibility [23]. This includes:

- iSeq 100 System [23]

- MiSeq System (including MiSeqDx and MiSeq i100 Series) [23]

- MiniSeq System [23]

- NextSeq Series (500, 550, 550Dx, 1000, 2000) [23]

- NovaSeq 6000 System (including NovaSeq 6000Dx) [23]

Kit Components and The Scientist's Toolkit

The IMAP kit is comprised of multiple reagent boxes that require storage at different temperatures to ensure stability and performance. The table below catalogs the essential research reagent solutions included in the kit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Kit Components

| Component | Function Description | Storage Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Purification Beads (IPB) | Magnetic beads for post-reaction clean-up and size selection [32]. | Room Temperature [32] |

| Stop Tagment Buffer 2 (ST2) | Halts the tagmentation reaction [32]. | Room Temperature [32] |

| Enrichment BLT (EBLTS) | Contains reagents for the enrichment PCR reaction [32]. | 2°C to 8°C [32] |

| Tagmentation Wash Buffer (TWB) | Used to wash beads during the tagmentation step [32]. | 2°C to 8°C [32] |

| Elution Prime Fragment 3HC Mix (EPH3) | Prepares fragments for adapter ligation [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Enhanced PCR Mix (EPM) | Enzyme mix for the amplification of generated libraries [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| First Strand Mix (FSM) | Contains reagents for first-strand cDNA synthesis [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Illumina PCR Mix (IPM) | Master mix for the initial amplicon PCR [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Resuspension Buffer (RSB) | Low TE buffer for resuspending and diluting libraries [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Reverse Transcriptase (RVT) | Enzyme for reverse transcribing RNA into cDNA [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Tagmentation Buffer 1 (TB1) | Facilitates the tagmentation (fragmentation and tagging) of DNA [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

| Illumina Unique Dual Indexes, LT | Contains unique barcodes for multiplexing up to 48 samples [32]. | -25°C to -15°C [32] |

It is critical to note that primer oligos are not included in the kit and must be sourced separately [23]. Illumina provides a list of tested and customer-demonstrated protocols for various pathogens, which can guide primer selection [23].

Experimental Protocol

The following section provides a detailed methodology for the IMAP library preparation workflow, which has been validated for multiple viral targets including SARS-CoV-2, Mpox, and Dengue virus [31].

The library preparation process begins with extracted nucleic acids and branches based on the input type, as visualized in the following workflow diagram.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Input-Specific Starting Point

The protocol is initiated at different stages depending on the nature of the nucleic acid input [31]:

- RNA-only inputs: Begin at the "Anneal RNA" step.

- DNA-only inputs: Start directly at the "Amplicon PCR" step.

- Combined RNA and DNA inputs: For DNA and RNA purified separately from the same sample, begin at the "Synthesize First Strand cDNA" step using the RNA input. The resulting cDNA and the purified DNA are then combined for the Amplicon PCR step [31].

Step 2: First-Strand cDNA Synthesis (For RNA-containing inputs)

- Anneal RNA: Combine RNA sample with the appropriate, target-specific RT primer pool in a PCR plate.

- Synthesize cDNA: Add the First Strand Mix (FSM) and Reverse Transcriptase (RVT) to the annealed RNA/primer mix. Incubate the plate to synthesize the first-strand cDNA.

- Inactivate Enzyme: Heat-inactivate the reverse transcriptase to stop the reaction [31].

Step 3: Amplicon PCR

- Prepare PCR Mix: Combine the Illumina PCR Mix (IPM) with the appropriate, target-specific primer pool in a new PCR plate.

- Add Template: Transfer the synthesized cDNA (for RNA inputs), purified DNA, or combined cDNA/DNA (for dual inputs) into the PCR mix.

- Amplify: Perform PCR amplification using a verified thermal cycler protocol to generate the target amplicons [31].

Step 4: Library Construction and Clean-up

- Clean Up Amplicons: Use Illumina Purification Beads (IPB) to purify the PCR amplicons, removing enzymes, salts, and primers.

- Tagment DNA: Combine the purified amplicons with Tagmentation Buffer 1 (TB1) to fragment and tag the DNA. The reaction is then stopped with Stop Tagment Buffer 2 (ST2).

- Wash Beads: Use Tagmentation Wash Buffer (TWB) to wash the beads during this step.

- Amplify Libraries: Add the Elution Prime Fragment 3HC Mix (EPH3), Enrichment BLT (EBLTS), and Enhanced PCR Mix (EPM) to the tagmented DNA. Introduce the unique dual indexes for each sample. Perform a final PCR to enrich for the tagmented fragments and incorporate the sample indexes [32].

Step 5: Final Library Clean-up and Quality Control

- Purify Final Library: Use Illumina Purification Beads (IPB) for a final clean-up of the amplified libraries.

- Quantify and Pool: Elute the libraries in Resuspension Buffer (RSB). Quantify each library using a fluorometric method, normalize, and pool as required for sequencing [32].

- Sequence: Dilute the pooled library to the appropriate loading concentration for the chosen Illumina sequencing platform.

Applications and Demonstrated Protocols

The flexibility of the IMAP kit is evidenced by its use in a wide array of published and customer-demonstrated protocols for infectious disease research and surveillance. Analysis is streamlined using the DRAGEN Targeted Microbial App on BaseSpace Sequence Hub, which supports pre-loaded targets and custom analyses [23].

Table 3: Selected Demonstrated Protocols for IMAP

| Pathogen / Application | Specific Target/Note | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Virus | SARS-CoV-2 (ARTIC v5.4.2) | [23] |

| Influenza A/B (Whole Genome) | [33] | |

| Mpox (MPXV) | [23] | |

| Dengue I-IV (Pan-serotype) | [23] | |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | [23] | |

| HIV-1 (Drug Resistance) | [23] | |

| Bacterium | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [23] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | [23] | |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | [23] | |

| Fungus | Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii | [23] |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | [23] |

The Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep kit provides a robust, streamlined, and highly flexible solution for NGS-based microbial research. Its ability to handle diverse sample types and nucleic acid inputs, combined with extensive compatibility with Illumina sequencing platforms and a growing repository of community-developed protocols, makes it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals focused on pathogen genomics, outbreak surveillance, and microbiome studies.

In Illumina-based microbiome sequencing, the selection of which hypervariable region(s) of the 16S rRNA gene to target is a critical first step in library preparation that profoundly influences all downstream results. The 16S rRNA gene contains nine variable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved sequences, and the choice of primer pairs determines the taxonomic resolution, specificity, and accuracy of the microbial community profile [34]. This application note provides a structured comparison of commonly targeted regions and detailed experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing optimal primer strategies for specific research contexts.

Performance Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Hypervariable Regions

The table below summarizes key characteristics and comparative performance of primer sets targeting different hypervariable regions, based on recent empirical studies.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Hypervariable Regions

| Target Region | Common Primer Pairs | Recommended Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Taxonomic Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | 27F-338R, 68F-338R (V1-V2M) | Human biopsy samples (esp. low bacterial biomass), respiratory microbiota, forensic samples | Low off-target human DNA amplification; High taxonomic richness in upper GI tract; Highest AUC (0.736) for respiratory taxa [35] [36] | May miss some taxa (e.g., Fusobacteriota with standard primers) [36] | Significantly higher in esophagus and duodenum vs. V4 [36] |

| V3-V4 | 341F-785R, 515F-806R | General microbiome studies, Environmental samples | Widely used with standardized protocols; Good for general bacterial diversity [34] [37] | Susceptible to off-target human DNA amplification; Variable performance across environments [34] [36] | Primer performance varies significantly by sample type [34] |

| V4 | 515F-806R | Earth Microbiome Project standard, Stool samples | Extensive published comparisons; Standardized bioinformatic pipelines [34] | Poor performance with human DNA-rich samples; Misses specific phyla [34] [36] | Lower in human biopsy samples vs. V1-V2 [36] |

| V4-V5 | 515F-944R, 515F-Y/926R | Arctic marine environments, Studies requiring archaeal coverage | Concurrent coverage of bacteria and archaea; Similar bacterial profile to V3-V4 in marine systems [38] | Misses Bacteroidetes phylum [34] | Reveals higher diversity in Planctomycetes [38] |

| V6-V8 | 939F-1378R | Specialized applications | Complementary data for multi-region approaches | Limited independent validation data | Region-specific biases observed [34] |

Experimental Protocol: Library Preparation for V3-V4 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Reagents and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification/Function | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kit | Amplicon-based library preparation | Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) [23] |

| Primers | Target-specific amplification | V3-V4: 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 785R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) [37] |

| Sequencing System | High-throughput sequencing platform | Illumina MiSeq System (2×300 bp for V3-V4) [39] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data processing and analysis | QIIME2, DADA2, SILVA database [34] [37] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

DNA Extraction and Quantification

- Extract genomic DNA using a kit appropriate for your sample type (soil, stool, biopsy, etc.).

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and assess quality via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0).

- Standardize to a working concentration of 5-10 ng/μL for PCR amplification.

First-Stage PCR – Amplicon Generation

- Prepare PCR reactions as follows (volumes per sample):

- 2.5 μL Template DNA (5-10 ng/μL)

- 5.0 μL Each forward and reverse primer (1 μM stock)

- 12.5 μL 2X PCR Master Mix

- 0.0 μL Nuclease-free water to 25 μL total volume

- Use the following thermal cycling conditions for V3-V4 amplification:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 55°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

- Prepare PCR reactions as follows (volumes per sample):

PCR Clean-up

- Purify amplicons using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Elute in 25 μL nuclease-free water or elution buffer.

- Verify amplification and purity by running 1 μL on Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar fragment analyzer.

Index PCR and Library Normalization

- Add Illumina sequencing adapters and dual indices in a second, limited-cycle PCR reaction using the IMAP kit or equivalent [23].

- Clean up indexed libraries as in Step 3.

- Quantify libraries using fluorometric methods and normalize to 4 nM concentration.

Pooling and Sequencing

- Combine equal volumes of normalized libraries to create a sequencing pool.

- Denature with NaOH and dilute to appropriate loading concentration for the MiSeq system.

- Sequence using MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle) for 2×300 bp paired-end reads [39].

Critical Parameters and Optimization

- Truncation Settings: For V3-V4 amplicons (~464 bp) with 2×300 bp sequencing, calculate overlap as: (300 + 300 - 464) = 136 bp overlap. Adjust truncation parameters in DADA2 (

--p-trunc-len-fand--p-trunc-len-r) to maintain sufficient overlap (e.g., 280F/250R yields 66 bp overlap) while trimming low-quality bases [37]. - Negative Controls: Include negative extraction controls and PCR blanks to monitor contamination.

- Mock Communities: Use defined microbial mock communities of sufficient complexity to validate primer performance and bioinformatic pipeline accuracy [34].

Environment-Specific Primer Selection Guidelines

Human Tissue Samples with High Host DNA

For biopsy samples, blood, or other samples where human DNA predominates, V1-V2 primers demonstrate superior performance:

- Modified V1-V2 Primers: Use 68F_M (5'-...-3') with 338R to eliminate off-target human DNA amplification that plagues V4 primers (reduction from 70% to 0% human DNA alignment) [36].

- Protocol Modifications: One-step amplification protocol generates ~260 bp amplicons suitable for cost-efficient Illumina platforms (MiniSeq, iSeq) [36].

- Performance: Significantly higher taxonomic richness in esophagus and duodenum biopsies compared to V4 primers.

Respiratory Microbiota

For sputum samples from patients with chronic respiratory diseases:

- Optimal Region: V1-V2 demonstrates highest resolving power (AUC=0.736) for accurate taxonomic identification of respiratory bacteria [35].

- Comparative Performance: V1-V2, V3-V4, and V5-V7 show significantly higher alpha diversity than V7-V9 regions.

Marine and Environmental Samples

For aquatic environments, particularly Arctic marine communities:

- Bacterial-Only Focus: V3-V4 primers (341F/785R) provide comprehensive bacterial community analysis [38].

- Bacterial-Archaeal Communities: V4-V5 primers (515F-Y/926R) are recommended when concurrent archaeal coverage is needed, as they capture 10-20% archaeal communities in deep waters and sediments [38].

Bioinformatic Considerations and Data Interpretation

Figure 1: Bioinformatic workflow for 16S rRNA gene sequencing data

Database Selection and Nomenclature

Different reference databases employ varying taxonomic nomenclature that can impact cross-study comparisons:

- Database Comparison: GreenGenes (GG), RDP, SILVA, GRD, and Living Tree Project (LTP) vary in taxonomic classification and updating frequency [34].

- Nomenclature Challenges: Identical taxa may have different names across databases (e.g., Enterorhabdus versus Adlercreutzia), complicating comparisons [34].

- Recommendation: Use SILVA database for most applications and maintain consistency within a study to ensure comparable results.

Cross-Study Comparison Limitations

Comparative analyses reveal significant challenges in comparing datasets generated with different primer sets:

- Primer-Specific Biases: Microbial profiles cluster primarily by primer choice rather than sample origin, making cross-primer comparisons problematic [34].

- Independent Validation Required: Comparisons between datasets using different V-regions require independent cross-validation with matching regions and uniform data processing [34].

Primer selection for 16S rRNA gene sequencing requires careful consideration of the specific research question, sample type, and analytical goals. The V3-V4 region remains a solid choice for general bacterial community analysis, while V1-V2 demonstrates superior performance for human tissue samples with high host DNA content, and V4-V5 is preferable for environments where archaea represent a meaningful component of the microbial community. Regardless of the target region chosen, validation with appropriate mock communities, consistency in bioinformatic processing, and cautious interpretation of cross-study comparisons are essential for robust and reproducible microbiome research.

Within the framework of Illumina microbiome sequencing research, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a critical step for amplifying target regions of the 16S rRNA gene prior to library preparation. The quality and fidelity of this amplification directly impact sequencing results, influencing downstream analyses of microbial diversity and abundance. This application note provides a detailed, optimized protocol for PCR amplification, ensuring high yield and specificity for complex microbial community templates. The guidelines herein are designed to help researchers avoid common pitfalls and generate robust, reproducible sequencing libraries.

Reaction Setup and Component Optimization

A successful PCR amplification for microbiome sequencing relies on the precise combination and concentration of each reaction component. The following section outlines the function and optimal concentration for each reagent, providing a foundation for reliable amplification of microbial DNA.

Table 1: Optimized Reaction Components for Microbiome PCR Amplification

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Function & Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | 10–100 ng genomic DNA (microbiome sample) [40] [41] | Determines reaction specificity; excess template can cause non-specific amplification. |

| Forward/Reverse Primer | 0.1–0.5 µM each [42] [41] | Binds target sequence; higher concentrations increase spurious binding [43]. |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM of each dNTP [42] [41] | DNA synthesis building blocks; lower concentrations (50-100 µM) can enhance fidelity [41]. |

| MgCl₂ | 1.5–2.0 mM (Taq polymerase) [41] | Essential polymerase cofactor; critical optimization parameter [43] [40]. |

| PCR Buffer | 1X | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions for the polymerase. |

| DNA Polymerase | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [42] [41] | Catalyzes DNA synthesis; hot-start enzymes are recommended to prevent primer-dimer formation [43]. |

| Water | To final volume (e.g., 50 µL) | Nuclease-free water to bring the reaction to its final volume. |

| Additives (Optional) | DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M) [44] [40] | Disrupts secondary structures in GC-rich templates (>65% GC) [43] [40]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for PCR in Microbiome Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity for accurate amplification, crucial for reducing errors before sequencing [43]. |

| Hot-Start Polymerase | Enzyme activated only at high temperatures, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [43]. |

| GC-Rich Enhancer/Additives | Chemical additives like DMSO or Betaine that help denature hard-to-amplify, GC-rich genomic regions common in some bacteria [43] [40]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Separate magnesium chloride solution for fine-tuning the Mg²⁺ concentration, a critical factor for polymerase activity and specificity [40] [41]. |

| Universal PCR Buffer | Specially formulated buffer that allows primer annealing at a universal temperature (e.g., 60°C), simplifying protocol standardization [45]. |

Thermocycler Conditions and Cycle Optimization

The thermal cycling protocol is a multi-step process where each segment must be carefully controlled. The following workflow outlines the logical sequence for establishing and optimizing thermocycler conditions.

Initial Denaturation

The initial denaturation is critical for separating double-stranded DNA into single strands at the start of the reaction. For complex microbiome genomic DNA, a temperature of 94–98°C for 1–3 minutes is recommended [45] [40]. This step also serves to activate hot-start DNA polymerases. Prolonged incubation should be avoided unless amplifying GC-rich templates, as it can lead to unnecessary enzyme inactivation [45] [41].

Cycling Parameters: Denaturation, Annealing, and Extension

The core amplification cycle is typically repeated 25–35 times. The optimal number of cycles is a balance between obtaining sufficient yield and avoiding the plateau phase where reagents become depleted and by-products accumulate [45].

Table 3: Standard Three-Step PCR Cycling Parameters

| Step | Temperature | Time | Key Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 94–98°C | 15–30 seconds [40] [41] | Higher temperatures (98°C) may be needed for GC-rich templates [45] [40]. |

| Annealing | 45–65°C | 15–60 seconds [40] [41] | Most critical for specificity. Set 3–5°C below the primer Tm [45] [46]. Use a gradient for optimization [43]. |

| Extension | 68–72°C | 1 minute per kb [45] [41] | Time depends on polymerase speed and amplicon length. "Fast" enzymes may require only 10-15 sec/kb [40]. |