The Materials Genome Initiative: Principles, Applications, and Breakthroughs in Accelerated Materials Discovery

This article explores the fundamental principles of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), a transformative U.S.

The Materials Genome Initiative: Principles, Applications, and Breakthroughs in Accelerated Materials Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the fundamental principles of the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), a transformative U.S. effort to halve the time and cost of advanced materials development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details the integrated framework of computation, data, and experiment that forms the Materials Innovation Infrastructure. The content covers foundational concepts, practical methodologies including AI and autonomous experimentation, current challenges in implementation, and validation through real-world case studies, with particular emphasis on biomedical applications such as point-of-care tissue-mimetic materials.

The MGI Blueprint: Core Principles and Strategic Vision for Accelerated Materials Discovery

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a transformative U.S. multi-agency initiative designed to advance a new paradigm for materials discovery and design. Launched in 2011, its core mandate is to double the speed and reduce the cost of translating new materials from the laboratory to commercial application by seamlessly integrating computation, data, experiment, and theory [1] [2] [3]. This whitepaper delineates the fundamental principles of MGI research, tracing its historical context, defining its core infrastructure, and examining its modern imperative through current applications and methodologies. Framed within a broader thesis on MGI's foundational tenets, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with a technical guide to the initiative's evolving landscape, including the critical role of data science and autonomous experimentation in accelerating materials innovation for healthcare and biotechnology.

Historical Context and Genesis

The MGI was formally announced in June 2011, with President Barack Obama articulating its mission to help businesses "discover, develop, and deploy new materials twice as fast" [3]. The initiative's name, inspired by the Human Genome Project, reflects a similarly ambitious goal: to understand the essential components of materials and how they function, thereby enabling the deft design of materials tailored for specific uses [2] [4]. The historical problem MGI sought to address was a lengthy and costly development cycle, which traditionally took 10 to 20 years to move a new material from discovery to market deployment [2].

The philosophical underpinning of the MGI emerged from a growing recognition that the integration of computational tools, experimental tools, and digital data could shift the traditional "design-test-build" model to a more integrated approach where significant design and experimentation are performed in silico before physical prototyping [2]. This new paradigm was inspired by early successes, such as a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency project that used computational models to design a lighter, stronger turbine engine disk and reduced design time by 50% [2]. The MGI was conceived as a national infrastructure effort, akin to the U.S. railroad, highway, and Internet systems, with the potential to achieve an inflection point in the pace of materials discovery [4].

Core Principles and Strategic Goals

The MGI is predicated on a core research paradigm that advances materials discovery through the synergistic interaction of computation, experiment, and theory [5] [4]. This integrated approach is designed to create a closed-loop system where vast materials datasets are generated, analyzed, and shared, enabling researchers to collaborate across conventional boundaries and identify the attributes underpinning materials functionality [5].

The 2021 MGI Strategic Plan, marking the initiative's first decade, formalized this paradigm into three overarching goals that guide its ongoing efforts [1] [6]:

- Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII): This refers to a framework of integrated advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data that forms the backbone of accelerated materials development [1].

- Harness the power of materials data: This involves developing the standards, tools, and protocols for data sharing, curation, and mining to maximize the value of materials data [1].

- Educate, train, and connect the materials R&D workforce: Cultivating a skilled workforce that can operate effectively within this new, integrated research modality is essential for the MGI's long-term success [1].

These strategic goals are supported by the development of a specific "materials innovation infrastructure," which comprises four interdependent pillars, as detailed in Table 1 [3].

Table 1: Core Components of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure

| Component | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Software for predictive modeling, simulation, design, and exploration of materials. | Density functional theory (DFT), phase-field models, kinetic Monte Carlo, CALPHAD [7]. |

| Experimental Tools | Synthesis, processing, characterization, and rapid prototyping techniques. | High-throughput synthesis robotics, autonomous experimentation platforms, advanced microscopy [1] [5]. |

| Digital Data | Data standards, repositories, and analytic tools for material properties. | The Materials Project, Open Quantum Materials Database, NIST data repositories [6] [7] [8]. |

| Collaborative Networks | Integrated centers and partnerships for sharing best practices and data. | Materials Innovation Platforms (MIPs), public/private partnerships [3] [9]. |

The MGI Workflow and Logical Framework

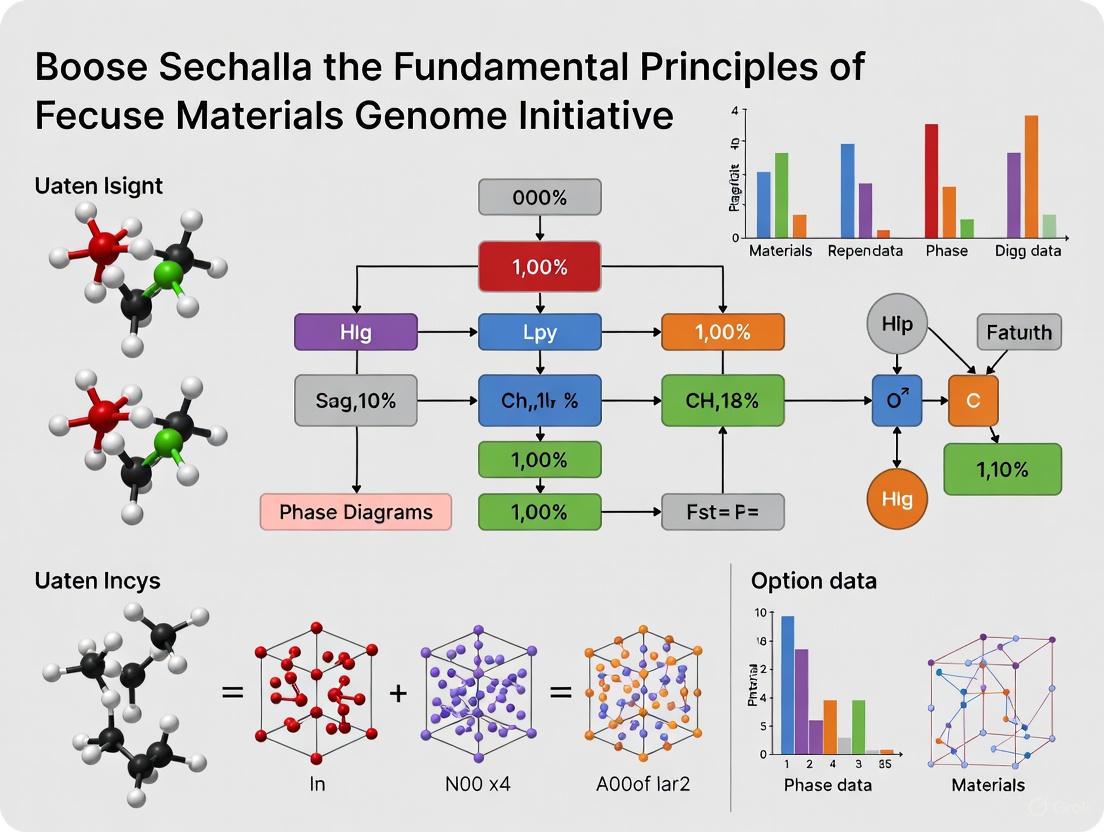

The MGI research paradigm can be visualized as a continuous, iterative cycle that tightly integrates computation, experiment, and data. This workflow eliminates traditional sequential barriers, fostering a collaborative environment where insights from one modality directly inform and refine the others. The following diagram illustrates this integrated logic.

This seamless interplay is essential for accelerating discovery. A representative scenario involves a researcher using a centralized database to identify candidate materials, performing more detailed simulations to narrow the list, and then conducting targeted experiments. The resulting experimental data, including both successful and failed attempts, are fed back into the database, where they can be used by other researchers to calibrate new computational models or refine processing protocols, thus seeding the next phase of investigation [5]. This democratization of research, driven by shared data and tools, is a hallmark of the MGI mode of operation [4].

The Modern Imperative: MGI in Practice

Key Application Domains and Success Stories

The MGI paradigm has demonstrated significant impact across diverse technological sectors. Key application domains identified by the community include Materials for Health and Consumer Applications, Materials for Information Technologies, Materials for Energy and Catalysis, and Multicomponent Materials and Additive Manufacturing [5]. Notable successes exemplifying the integrated MGI approach include:

- Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLEDs): A tightly integrated approach combining theory, quantum chemistry, machine learning, and experimental characterization was used to explore a space of 1.6 million candidate molecules. This effort resulted in a set of synthesized molecules with state-of-the-art external quantum efficiencies [5].

- Polar Metals: Quantum mechanical simulations were used to design a room-temperature polar metal in silico, which was subsequently synthesized using high-precision pulsed laser deposition, revealing a new member of an exceedingly rare class of materials [5].

- Biomaterial Innovation: Modern MGI efforts are heavily focused on biotechnology. For example, the NSF-funded BioPACIFIC MIP develops novel high-throughput methods for synthesizing biopolymers to replace petroleum-based products, while GlycoMIP focuses on automated synthesis of glycomaterials for applications in drug development and food science [9].

The Rise of Machine Learning and Autonomous Experimentation

Machine Learning (ML) has become a cornerstone of the modern MGI, serving as a bridge between large-scale data and accelerated material property prediction [8]. The main processes of ML in materials science involve data preparation, descriptor selection, algorithm/model selection, model prediction, and model application, forming a complete cycle from data collection to experimental validation [8]. ML applications in materials science are diverse, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Applications of Machine Learning in MGI Research

| Application Field | Specific Task Examples | Common ML Algorithms/Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Property Prediction | Predicting atomization energies, band gaps, sintered density, and critical temperature of superconductors [8]. | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Neural Networks [8]. |

| Structure Prediction | Predicting the crystallinity of molecular materials [8]. | SVM with RBF kernel [8]. |

| Process Optimization | Predicting the feasibility of untested reactions from data collected in failed experiments [8]. | Support Vector Machines (SVM) [8]. |

| Advanced Simulation | Constructing high-precision atomic interaction potentials; improving the accuracy of quantum mechanics (QM) calculations [8]. | Neural Networks, ML-interpolation of potential energy surfaces [8]. |

Concurrently, Autonomous Experimentation (AE) is emerging as a critical frontier. The U.S. Department of Energy has released a Request for Information (RFI) to inform interagency coordination around AE platform research, recognizing its potential to revolutionize materials R&D [1]. These "self-driving labs" combine robotics, advanced detectors, and AI to rapidly evaluate material properties and establish large-scale, curated archival data sets, ultimately empowering faster and more effective theoretical-computational-experimental iterations [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The practical implementation of the MGI relies on a suite of key research reagents, tools, and cyberinfrastructure. The following table details several essential components that form the scientist's toolkit for conducting MGI-aligned research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for MGI

| Item/Tool Name | Type | Function in MGI Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Robotics | Experimental Tool | Automates the creation of material libraries with varying composition or processing parameters, dramatically accelerating the experimental data generation phase [5] [9]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Tool | A foundational quantum mechanical method for predicting fundamental properties of materials (e.g., electronic structure, stability) from first principles, serving as a primary data source for high-throughput screening [7] [8]. |

| CALPHAD (CALculation of PHAse Diagrams) | Computational Tool | A proven, indispensable tool for calculating phase equilibria and phase transformations, which is critical for designing new materials and processing methods, especially in metallurgy and alloy development [6] [7]. |

| Materials Data Repositories/Curated Databases | Digital Data Infrastructure | Systems like the Materials Project and Open Quantum Materials Database provide critical, centrally stored data from both computation and experiment, enabling data mining, model training, and collaborative research [7] [8]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Data Analytics Tool | A machine learning algorithm used for classification and regression tasks; notably used to predict material crystallinity and the feasibility of synthetic reactions, including learning from "failed" experimental data [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Material Discovery

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for an integrated MGI research campaign, exemplified by the discovery of novel organic molecules for electronic applications, such as OLEDs [5].

1. Project Initiation and Target Definition

- Input: Define the target application and the key material properties required (e.g., high external quantum efficiency for an OLED, specific band gap for a photovoltaic).

- Action: Form an interdisciplinary team encompassing expertise in computation, synthesis, and characterization to ensure seamless integration throughout the project lifecycle.

2. High-Throughput Virtual Screening

- Descriptor Selection: Identify relevant molecular or structural descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, orbital energies, topological indices) that correlate with the target properties.

- Computational Setup: Use high-performance computing (HPC) resources to perform quantum chemical calculations (e.g., DFT) on a large library of candidate structures (e.g., 1.6 million molecules) to predict the target properties [5].

- Machine Learning Integration: Train machine learning models (e.g., neural networks) on a subset of the computed data to rapidly predict properties for the rest of the library, accelerating the screening process [8].

- Output: A ranked shortlist of candidate materials predicted to exhibit the best performance.

3. Targeted Synthesis and Characterization

- Guided Synthesis: Prioritize the synthesis of the top candidate materials identified from the computational screening.

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Where possible, employ automated synthesis platforms (e.g., robotic liquid handlers) to parallelize the synthesis of candidate materials [5] [9].

- Validation Characterization: Use techniques such as UV-Vis spectroscopy, photoluminescence, and cyclic voltammetry to measure the key properties of the synthesized materials.

- Output: Experimentally validated property data for the synthesized candidates.

4. Data Management, Analysis, and Feedback

- Data Curation: Upload all data—including computational predictions, synthetic protocols (both successful and failed), and characterization results—into a shared, standardized database [5].

- Model Refinement: Use the experimental data to validate and refine the computational and machine learning models, improving their predictive accuracy for subsequent design-test cycles [8].

- Feedback Loop: The refined models are used to initiate a new round of virtual screening, further optimizing the material structure. This creates the closed-loop, iterative process that is central to the MGI paradigm.

The Materials Genome Initiative represents a fundamental and enduring shift in the philosophy and practice of materials research. By championing an integrated infrastructure that unifies computation, experiment, theory, and data, it has created a collaborative and accelerated pathway for materials innovation. From its historical launch a decade ago to its current strategic focus on data harnessing and workforce development, the MGI continues to evolve, increasingly powered by machine learning and autonomous experimentation. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing the MGI paradigm is no longer optional but a modern imperative to tackle complex challenges in healthcare, biotechnology, and beyond, ensuring the rapid discovery and deployment of advanced materials that will define the future technological landscape.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a multi-agency federal initiative designed to achieve a transformative aspiratory goal: discovering, manufacturing, and deploying advanced materials twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost compared to traditional methods [1]. Launched in June 2011, MGI is inspired by the scale and ambition of the Human Genome Project and is predicated on a fundamental shift in materials research methodology [2]. This shift integrates advanced computational modeling, experimental tools, and data science into a unified framework, moving away from the traditional sequential "design-test-build" cycle toward a concurrent approach where materials discovery and development are profoundly accelerated [6] [2].

The initiative's core premise is that by harnessing the power of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII)—an integrated framework of computational tools, experimental data, and digital platforms—researchers can dramatically reduce the typical 10- to 20-year timeline for moving a new material from the laboratory to commercial application [1] [2]. This accelerated pathway is critical for enhancing U.S. economic competitiveness and national security, as advanced materials are foundational to sectors ranging from healthcare and communications to energy, transportation, and defense [1].

The Strategic Framework: Goals and Implementation

The strategic vision of MGI, as outlined in its 2021 Strategic Plan, is built upon three interconnected pillars that guide its implementation and the development of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure [1].

Strategic Goals

Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII): This goal focuses on creating a deeply integrated ecosystem of advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data. The MII serves as the foundational framework that enables researchers to seamlessly share data and methodologies across institutions and disciplines [1].

Harness the Power of Materials Data: Effective data management is central to MGI's mission. This involves developing robust protocols for data curation, exchange, and critical evaluation to ensure data quality, reproducibility, and interoperability. The initiative promotes open-access policies to maximize the utility of federally funded research data while recognizing the need to balance transparency with proprietary industry interests [6] [2].

Educate, Train, and Connect the Materials R&D Workforce: Building a skilled community of practice is essential for widespread adoption of the MGI paradigm. This involves developing interdisciplinary training programs and fostering collaborations across academia, national laboratories, and industry to accelerate the integration of MGI methodologies into mainstream materials research [1].

Quantitative Objectives and Progress

Table: MGI Objectives and Measurable Outcomes

| Objective Category | Traditional Timeline/Cost | MGI Target | Documented Progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 10-20 years [2] | Reduced by 50% (5-10 years) [2] | DARPA turbine engine disk project achieved ~50% reduction in design time [2] |

| Development Cost | High (industry-specific) | Significantly reduced [1] | Federal investment of $63M (2012) to $100M request (2014) [2] |

| Data & Tool Accessibility | Limited/Fragmented | Unified infrastructure & open-access data policies [6] | NIST development of data exchange protocols & quality assessment [6] |

Core Methodologies for Accelerated Materials Development

The operationalization of MGI's goals relies on the synergistic application of computational, experimental, and data-driven methodologies. These are not applied in sequence but are deeply integrated throughout the materials development lifecycle.

The Integrated Computational Materials Engineering (ICME) Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the foundational, iterative workflow of the MGI methodology, demonstrating how computation, data, and experimentation are interwoven.

This workflow demonstrates the core MGI paradigm. It begins with Computational Design & Prediction, where materials are modeled in silico to screen thousands of potential candidates, moving beyond calculating one molecule at a time [2]. This generates massive datasets that feed into Data Curation & Analysis, supported by platforms like the NIST Materials Resource Registry [6]. Promising candidates then proceed to physical Synthesis & Digital Prototyping and High-Throughput Experimentation, where autonomous experimentation platforms can rapidly iterate [1]. The loop is closed as Performance Validation data refines the computational models and enriches the shared databases, creating a continuous learning cycle [2].

The Role of Autonomous Experimentation

A key advancement in operationalizing this workflow is the move toward autonomous experimentation (AE). As identified in a recent MGI workshop, AE platforms represent a crucial infrastructure component that can self-drive the iterative cycle of synthesis, characterization, and analysis with minimal human intervention [1]. This represents the ultimate realization of the accelerated MGI workflow, potentially reducing the experimental timeline from years to days for certain material classes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Infrastructure

The practical implementation of MGI relies on a suite of specialized tools, databases, and computational resources. This "toolkit" enables researchers to execute the integrated workflow described above.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Infrastructure Solutions for MGI

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Example | Function & Application in MGI |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Modeling Software | µMAG Micromagnetic Modeling [6] | Provides a public reference implementation and standard problems for micromagnetic simulation, enabling benchmarking and reproducibility. |

| Critical Evaluated Databases | NIST Standard Reference Data [6]NIST XPS Database [6]Harvard Clean Energy Database [2] | Provides critically evaluated scientific data (e.g., 2.3M molecules for solar cells) as essential inputs for predictive models and validation. |

| Data Registration & Discovery | Materials Resource Registry [6] | Bridges the gap between data resources and end-users by creating a searchable registry of available materials data assets. |

| Autonomous Experimentation (AE) Platforms | MGI AMII Infrastructure [1] | Integrated robotic systems that execute the "test" phase of the MGI loop, using AI to plan and perform experiments without human intervention. |

| CALPHAD Tools | NIST Uncertainty Assessment [6] | Indispensable tools for calculating phase diagrams and predicting phase equilibria, which is fundamental to alloy and process development. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: The Accelerated Development of a Turbine Engine Disk

A landmark project conducted by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) serves as a concrete, successful implementation of the MGI methodology and provides a template for an accelerated development protocol [2].

Background and Objective

- Challenge: To design a new, lighter, and stronger turbine engine disk for aerospace applications.

- Traditional Approach: A lengthy series of iterative "design-test-build" cycles, where scientists design a material, create it in the lab, test it, and then tweak it based on results [2].

- MGI Approach: A parallel, integrated approach where a significantly greater portion of the design and experimentation was conducted using computer models before physical prototyping [2].

Methodology and Workflow

The protocol involved two parallel tracks running concurrently:

High-Fidelity Computational Modeling:

- Step 1: Developed sophisticated multi-scale models to predict the microstructure, mechanical properties, and performance of candidate nickel-based superalloy compositions under extreme operating conditions (high temperature and stress).

- Step 2: Used these models to screen thousands of virtual compositions and processing parameters (e.g., heat treatment temperatures and times).

- Step 3: Identified a narrow band of promising candidate compositions with predicted optimal strength-to-weight ratios and fatigue resistance.

Targeted Physical Validation:

- Step 4: Synthesized only the top-performing candidate alloys identified by the models, using techniques like vacuum induction melting and isothermal forging.

- Step 5: Conducted high-throughput characterization of the synthesized candidates, focusing on validating the key properties predicted by the models, such as creep resistance and microstructural stability.

- Step 6: Fed the experimental results directly back to refine the computational models, improving their predictive accuracy for future iterations.

The group employing the MGI-inspired protocol achieved a reduction in design time by approximately 50% compared to the traditional approach running in parallel [2]. Furthermore, the resulting turbine engine disk was lighter and stronger than the one developed through traditional methods, demonstrating that the model-driven approach not only accelerates development but can also lead to superior material performance [2]. This case study stands as a powerful validation of MGI's core aspirational goal.

The Materials Genome Initiative represents a fundamental paradigm shift in materials science and engineering. By championing an integrated, data-driven infrastructure that unifies computation, experiment, and digital data, MGI has created a viable pathway to achieving its aspirational goal of halving the development time and cost for advanced materials [1] [2]. The continued development of strategic tools—including autonomous experimentation, open-data repositories, and standardized protocols—is critical to overcoming traditional barriers. As these methodologies become more widely adopted, the potential for accelerated innovation across critical sectors from semiconductors to healthcare is immense, promising to enhance economic competitiveness and address pressing global challenges through the rapid deployment of advanced materials.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a multi-agency initiative designed to advance a new paradigm for materials discovery and deployment, with the goal of bringing new materials to market twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost compared to traditional methods [10] [1]. At the heart of this paradigm shift is the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), a foundational framework that integrates advanced computation, experimental tools, and data infrastructure to create a seamless, accelerated pathway for materials research and development [11] [1]. The MII represents the practical embodiment of the MGI's core philosophy: that the synergistic integration of computation, experiment, and theory can dramatically accelerate the discovery and development of advanced materials [10].

The MGI's strategic vision, as outlined in its 2021 strategic plan, identifies three overarching goals: (1) Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure; (2) Harness the power of materials data; and (3) Educate, train, and connect the materials research and development workforce [1]. The MII directly addresses the first goal by providing the interconnected resources—digital and physical—that enable researchers to navigate the complex materials development landscape more efficiently. This infrastructure supports the entire materials development continuum, from basic research through manufacturing and deployment, creating an ecosystem where data, models, and insights can be shared and built upon across traditional disciplinary boundaries [11] [12].

The Core Components of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure is architected as an interoperable suite of tools and capabilities that support the integrated MGI approach to materials development. Its core components work in concert to enable rapid iteration and knowledge generation across diverse materials classes and applications [11].

Computational Tools and Theory

The computational pillar of the MII encompasses theory, modeling, and simulation tools that enable predictive materials design across multiple length and time scales [11]. These tools range from quantum-mechanical calculations predicting fundamental electronic properties to mesoscale and continuum modeling of materials processing and performance. A key objective is to address gaps in computational tools that present barriers to accessibility for diverse stakeholders along the materials development continuum [11]. The national computational infrastructure serves as a foundation, with efforts focused on nurturing community codes and incorporating advanced techniques into commercial software [11].

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of these computational approaches. For instance, Kim et al. applied quantum mechanical simulations to design, in silico, a room-temperature polar metal exhibiting unexpected stability, which was subsequently synthesized using high-precision pulsed laser deposition [10]. Similarly, Gomez-Bombarelli et al. utilized high-throughput virtual screening combining theory, quantum chemistry, machine learning, and cheminformatics to explore a space of 1.6 million organic light-emitting diode (OLED) molecules, resulting in experimentally synthesized molecules with state-of-the-art external quantum efficiencies [10].

Table 1: Key Computational Techniques in the MII

| Technique Category | Representative Methods | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Calculations | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Quantum Monte Carlo | Prediction of band gaps, thermodynamic stability [10] |

| Atomistic Simulations | Molecular Dynamics, Monte Carlo | Phase stability, defect properties [10] |

| Mesoscale Modeling | Phase Field, Cellular Automata | Microstructure evolution, polymer self-assembly [10] |

| Continuum Modeling | Finite Element Analysis, CALPHAD | Process optimization, mechanical performance [6] |

| Data-Driven Modeling | Machine Learning, Cheminformatics | Property prediction, molecular design [10] |

Experimental Tools and Platforms

The experimental component of the MII includes synthesis, processing, and characterization tools that generate critical validation data and enable the fabrication of designed materials [11]. A strategic priority is expanding these tools to more materials classes and developing multimodal characterization capabilities [11]. The MII particularly emphasizes leveraging advances in modular, autonomous, integrated, high-throughput experimental tools that can accelerate the transition from laboratory discovery to manufacturing scale [11].

The MII also focuses on removing barriers that limit access to state-of-the-art instrumentation, particularly for historically black colleges and universities and other minority serving institutions [11]. This commitment to accessibility ensures that the benefits of the infrastructure are widely distributed across the research community. Integrated materials platforms serve as physical hubs where these advanced tools are co-located and operated with a focus on collaborative, interdisciplinary research [11]. The Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP) program by the National Science Foundation exemplifies this approach, supporting mid-scale infrastructure that advances materials discovery through integrated synthesis, characterization, and modeling while promoting collaboration and knowledge sharing [13].

Data Infrastructure and Analytics

The data infrastructure of the MII provides the digital backbone that enables the integration of computational and experimental components [11]. This includes tools, standards, and policies to encourage FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) across the materials community [11]. A central challenge addressed by this component is the development of a framework for coupling and integrating public and private data repositories, creating what amounts to a national materials data network [11].

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) plays a particularly important role in developing the data infrastructure, establishing essential data exchange protocols and the means to ensure the quality of materials data and models [6]. NIST is working with stakeholders in industry, academia, and government to develop the standards, tools and techniques enabling acquisition, representation, and discovery of materials data; interoperability of computer simulations across multiple length and time scales; and quality assessment of materials data, models, and simulations [6].

Integrated Workflows: The "Closed-Loop" Research Paradigm

The true power of the MII emerges when its components are integrated into seamless workflows that accelerate materials discovery and development. The MGI promotes a "closed-loop" research paradigm where computation, experiment, and data analytics interact in an iterative, tightly coupled manner [10] [14].

The Integrated Workflow Process

A representative integrated workflow, as envisioned under the MGI paradigm, might unfold as follows [10]:

- A researcher submits a query to a user facility that synthesizes and characterizes a new class of materials in a high-throughput manner using advanced, modular robotics

- The results automatically populate a centralized database, reporting both successful and failed synthetic routes alongside materials properties

- A computational researcher uses the experimentally measured properties to calibrate a new computational model that predicts materials properties based on structure

- Using an inverse-design optimization framework, that researcher runs high-throughput computations to identify candidate structures that optimize the target property

- These candidates are flagged to the community and posted in the online database alongside the experimental results

- Another researcher with expertise in materials processing refines a data-driven model predicting optimum processing routes given molecular structure

- This researcher determines processing protocols for the flagged structures and adds these to the database

- The original researcher uses these structures and processing protocols to seed the next phase of experimental investigation

This workflow exemplifies the MGI vision of tightly integrated, collaborative research that leverages distributed expertise and shared infrastructure [10]. The following diagram illustrates this integrated, closed-loop methodology:

Closed-Loop Materials Innovation Workflow

Exemplary Implementation: The DMREF Program

The Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF) program is NSF's primary mechanism for implementing the integrated MGI approach [12]. DMREF supports interdisciplinary teams of researchers working synergistically in a "closed-loop" fashion to build the fundamental knowledge base needed to advance materials design and development [14]. The program drives the integration of experiment, theory, computation, data analytics, and artificial intelligence, as well as the development of new tools, processing approaches, and infrastructure [14].

DMREF unifies the materials enterprise across nine Divisions and three Directorates at NSF, creating an interdisciplinary endeavor that spans materials, physics, mathematics, chemistry, engineering, and computer science [12]. Through an iterative feedback loop among computation, theory, artificial intelligence, and experiment that includes different physical models to capture specific processes or phenomena, interdisciplinary DMREF projects provide molecular pathways to functional materials with desirable properties and harness new paradigms for knowledge generation and sharing [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MII Implementation

Successful implementation of the MII paradigm requires access to specialized research reagents, computational resources, and experimental tools. The following table details key components of the "scientist's toolkit" for MII-enabled research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MII Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in MII Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | ACCESS/PaTH cyberinfrastructure, quantum chemistry codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO), molecular dynamics packages (LAMMPS, GROMACS) | Enable high-throughput screening, multi-scale modeling, and data generation [12] |

| Experimental Synthesis | High-throughput synthesis robots, pulsed laser deposition systems, modular polymer synthesis platforms | Accelerate materials fabrication and processing optimization [11] [10] |

| Characterization Tools | Small-angle X-ray scattering, high-resolution TEM, automated SEM, XPS databases | Provide structural and chemical information for model validation and refinement [10] [6] |

| Data Management | NIST Materials Resource Registry, standardized data formats, FAIR data repositories | Ensure data findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability [11] [6] |

| Specialized Libraries | OLED molecular libraries, MOF/zeolite structures, polymer building blocks | Serve as starting points for computational screening and experimental synthesis [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Computational-Experimental Studies

To illustrate the practical implementation of the MII approach, this section provides detailed methodologies for key research activities that integrate computation and experiment.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Functional Organic Molecules

This protocol outlines an integrated approach for discovering novel organic electronic materials, based on the methodology described by Gomez-Bombarelli et al. [10]:

Virtual Library Construction:

- Enumerate chemical space using combinatorial combination of known synthetic building blocks

- Apply functional group compatibility filters and synthetic accessibility scoring

- Generate 3D conformers for each candidate structure using rule-based algorithms

Multi-stage Computational Screening:

- Perform DFT calculations for preliminary electronic property assessment

- Apply machine learning models trained on existing experimental data to predict target properties

- Use evolutionary algorithms for inverse design of molecules optimizing multiple target properties

- Apply toxicity and environmental impact predictors for green materials design

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top candidate compounds using high-throughput robotic synthesis platforms

- Characterize optical and electronic properties using automated spectroscopy systems

- Perform device fabrication and testing using standardized measurement protocols

- Document both successful and failed synthesis attempts in shared databases

Data Integration and Model Refinement:

- Feed experimental results back into computational models to improve prediction accuracy

- Update machine learning training sets with new experimental data

- Identify structure-property relationships to guide subsequent design cycles

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization of Self-Assembling Materials

This protocol describes the iterative approach combining physics-based modeling, small-angle X-ray scattering, and evolutionary optimization as demonstrated by Khaira et al. [10]:

Initial Structure Characterization:

- Prepare thin film samples using controlled processing conditions

- Collect small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) patterns with high angular resolution

- Analyze scattering data to determine primary structural parameters (domain spacing, orientation)

Physics-Based Modeling:

- Develop coarse-grained molecular models capturing essential chemical features

- Implement self-consistent field theory (SCFT) simulations of self-assembly behavior

- Calculate theoretical scattering patterns from simulated structures

Iterative Refinement:

- Compare experimental and theoretical scattering patterns using quantitative similarity metrics

- Adjust simulation parameters to improve agreement with experimental data

- Utilize evolutionary algorithms to efficiently explore parameter space

- Identify molecular features controlling assembly behavior through sensitivity analysis

Structure Validation:

- Prepare additional samples predicted to exhibit targeted structural features

- Perform detailed structural characterization using TEM and AFM

- Correlate local structure with bulk properties through multimodal characterization

Current Implementation and Future Directions

The MII continues to evolve through coordinated federal investments and community engagement. Key implementation mechanisms include:

Federal Programs and Partnerships

Multiple federal agencies coordinate to advance the MII through targeted programs and partnerships. The National Science Foundation supports fundamental research through DMREF, provides infrastructure via Materials Innovation Platforms (MIPs), and fosters workforce development [12]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology focuses on developing data standards, reference data, and measurement science to underpin the MII [6]. Current initiatives include pilot projects to develop superalloys and advanced composites, both targeting new, energy-efficient materials for transportation applications [6].

International partnerships are also expanding, as evidenced by the collaboration between NSERC (Canada) and NSF, offering funding for Canadian researchers to team up with U.S. colleagues as interdisciplinary teams working synergistically to advance materials design and development [15].

Emerging Frontiers

The MII is expanding into new scientific frontiers and technological domains. Autonomous Experimentation (AE) represents a particularly promising direction, with recent workshops and reports exploring how AI-enabled autonomous materials platforms can further accelerate the research cycle [1]. The integration of quantum materials foundries through programs like Q-AMASE-i is creating specialized infrastructure for advancing quantum information science and engineering [12].

The application of the MII paradigm to sustainable materials represents another critical frontier, with recent initiatives focusing on developing sustainable semiconductor materials using AI-assisted approaches [1]. These emerging directions demonstrate how the MII continues to adapt to new scientific opportunities and national needs.

The Materials Innovation Infrastructure represents a transformative approach to materials research and development that integrates computation, data, and experiment into a cohesive, accelerated workflow. By providing the tools, standards, and collaborative frameworks that enable researchers to work in new ways, the MII embodies the core principles of the Materials Genome Initiative. The infrastructure's power derives not from any single component, but from the synergistic integration of computational design, high-throughput experimentation, and data-driven discovery into iterative, closed-loop workflows. As the MII continues to evolve and expand, it promises to significantly accelerate the design and deployment of advanced materials that address critical needs in healthcare, energy, communications, and national security.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a multi-agency U.S. government initiative designed to propel the discovery, development, and deployment of advanced materials at an accelerated pace. Launched in 2011, its ambitious goal is to halve the time and cost traditionally required to bring new materials from the laboratory to the marketplace [16]. This initiative responds to a critical national need: in an increasingly competitive global economy, the United States must find ways to rapidly integrate advanced materials into innovative products such as lightweight vehicles, more efficient solar cells, and tougher body armor [17]. The MGI strategic approach involves fostering a fundamental paradigm shift from traditional, sequential, trial-and-error methods to an integrated framework where computation, data, and experiment are tightly interwoven [17] [18]. This new paradigm, known as the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), provides the foundational tools, data, and standards that enable this accelerated development [12] [1]. The coordinated efforts of key federal agencies—including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Department of Energy (DOE), and the Department of Defense (DOD)—are central to realizing this vision, each contributing unique capabilities and resources to a unified national strategy [17] [16].

Agency-Specific Roles and Quantitative Investments

The core strength of the Materials Genome Initiative lies in the specialized, complementary roles undertaken by its lead federal agencies. The strategic alignment and financial investments of these agencies form the backbone of the MGI ecosystem, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Federal Agency Roles and Investments in the Materials Genome Initiative

| Agency | Primary Role & Focus | Key Programs & Tools | Reported Investments & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Science Foundation (NSF) | Supports fundamental, fundamental research and workforce development across the materials continuum [12]. | DMREF (Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future): Unifies materials research across nine divisions and three directorates [12]. Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP): Creates scientific ecosystems for sharing tools, codes, samples, and data [12]. | FY 2012: $11 million in DMREF grants [16]. FY 2013 Request: >$30 million [16]. As of 2018, DMREF had awarded 258 grants to teams at 80 academic institutions in 30 states [17]. |

| National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) | Develops essential data exchange protocols, quality standards, and metrologies for materials data and models [6] [18]. | Advanced Composites Pilot: Develops new, energy-efficient materials for transportation [6]. µMAG (Micromagnetic Modeling Activity Group): Establishes standard problems and reference software [6]. Materials Resource Registry: Registers materials resources to bridge the gap with end-users [6]. | FY 2012 Investment: Part of a $60+ million multi-agency total [16]. FY 2013 Request: An additional $10 million (bringing total to $14 million) [16]. |

| Department of Energy (DOE) | Focuses on energy-related materials challenges, leveraging national laboratory capabilities and high-performance computing [17] [19]. | The Materials Project: A database of computed information on known and predicted materials properties [17]. Energy Materials Network: A network of consortia providing industry access to national lab capabilities [17]. Predictive Materials Science and Chemistry program [16]. | FY 2012: $18 million for Predictive Materials Science [16]. The Materials Project includes data on >600,000 materials and has >20,000 users [17]. |

| Department of Defense (DOD) | Funds research to improve prediction and optimization of materials for defense applications [16]. | Lightweight Innovations for Tomorrow (LIFT) Institute: For metals processing and structural design [17]. Research integrated through Office of Naval Research, Army Research Laboratory, and Air Force Research Laboratory [16]. | FY 2012 Investment: $17.3 million [16]. FY 2013 Plan: "Significant increase" [16]. |

The Core MGI Methodology: An Integrated Computational-Experimental-Theoretical Workflow

The fundamental principle of MGI research is the replacement of linear, empirical development with a tightly integrated, iterative cycle that combines computation, theory, and experiment. This methodology, often referred to as "materials by design," allows researchers to navigate the complex landscape of material composition, structure, and properties with unprecedented efficiency [18] [16].

The Integrated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative feedback loop that defines the MGI approach, integrating computation, experiment, and theory to accelerate discovery.

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

To realize the workflow above, researchers employ a suite of specific, interconnected protocols. The methodologies below detail the key components of the MGI research paradigm.

Protocol for Integrated Computational Materials Design (ICMD)

The ICMD protocol uses simulation to guide experimental efforts, drastically reducing the number of trial experiments needed.

- A. Objective: To identify candidate material compositions and structures with a high probability of exhibiting target properties before resource-intensive synthesis is undertaken.

- B. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Problem Definition: Define the target performance criteria and operating environment for the new material (e.g., high strength-to-weight ratio at elevated temperatures).

- Multi-scale Modeling Cascade:

- Ab Initio/Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Compute fundamental electronic structure, phase stability, and defect properties at the atomic scale.

- Mesoscale Modeling (Phase Field, Kinetic Monte Carlo): Simulate microstructural evolution, grain growth, and phase transformations.

- Continuum-Level Modeling (Finite Element Analysis): Predict macroscopic engineering properties and performance under applied loads or environments.

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: Automate the multi-scale modeling cascade to computationally screen thousands of candidate compositions, down-selecting to a shortlist of the most promising candidates.

- Data Output for Experimental Validation: Deliver a ranked list of candidate compositions with predicted structures and key properties to guide the targeted synthesis protocol.

Protocol for Targeted Synthesis & High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

This protocol focuses on the rapid synthesis and characterization of candidates identified through computational screening.

- A. Objective: To efficiently synthesize and characterize the shortlist of computationally-predicted materials, generating high-fidelity data for model validation and refinement.

- B. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Sample Library Fabrication: Use combinatorial methods (e.g., composition spreads deposited via sputtering or inkjet printing) to create libraries of the candidate materials on a single substrate.

- High-Throughput Characterization: Employ automated, parallelized techniques to characterize the libraries.

- Structural Analysis: Automated X-ray Diffraction (XRD) or electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) for phase identification and crystal structure.

- Chemical Analysis: Automated X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) for composition and chemical state.

- Functional Property Mapping: Automated scanning probe microscopy (SPM) for localized property measurement (e.g., hardness, electronic properties).

- Data Management: All data generated must be tagged with comprehensive metadata (sample history, processing parameters) and stored in formats compliant with the Materials Resource Registry and other FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [6] [20].

Protocol for Autonomous Experimentation (AE)

This emerging protocol represents the cutting edge of the MGI paradigm, leveraging artificial intelligence to create a closed-loop discovery system.

- A. Objective: To automate the entire "make-measure-analyze" cycle, enabling AI-driven autonomous discovery of materials without constant human intervention.

- B. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Setup: Define the objective function (e.g., maximize electrical conductivity) and constraints (e.g., phase stability, non-toxicity).

- Active Learning Loop:

- The AI agent proposes a set of experimental conditions or compositions based on prior data and its internal model.

- An automated robotic platform executes the synthesis and characterization (as in the HTE protocol).

- The resulting data is fed back to the AI agent.

- The agent updates its model and proposes the next most informative set of experiments to approach the objective.

- Output: The system converges on an optimal material or provides a refined model mapping the composition-structure-property landscape. This approach is a key focus of recent MGI challenges and interagency coordination [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The practical execution of MGI research relies on a suite of shared cyber-infrastructure, data resources, and physical platforms. These "reagent solutions" are the essential components of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for MGI Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to MGI Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Materials Project (DOE) [17] | Database | Provides computed properties of over 600,000 known and predicted materials. | Serves as the starting point for computational screening and hypothesis generation in the ICMD protocol. |

| NIST Standard Reference Data [6] | Database | Provides critically evaluated scientific and technical data, including XPS data. | Provides trusted, high-quality reference data for calibrating experiments and validating computational models. |

| DMREF Website & Associated Repositories [12] | Data Portal / Tool Hub | Serves as a platform for researchers to share science highlights, data repositories, software, and machine-learning tools. | Facilitates data sharing and reuse, and provides access to specialized software tools developed by the community. |

| ACCESS & PaTH [12] | Cyberinfrastructure | Provides diverse computational resources and services to the research community. | Supplies the high-performance computing power required for resource-intensive multi-scale modeling. |

| Materials Innovation Platforms (MIP) [12] | Physical Research Center | Acts as a scientific ecosystem sharing cutting-edge tools, codes, samples, and data. | Provides access to state-of-the-art, often expensive, instrumentation required for high-throughput experimentation and characterization. |

| Materials Resource Registry [6] | Registry | Allows for the registration of materials resources, bridging the gap between existing resources and end-users. | Makes data and tools findable, a core principle of the FAIR data guiding the entire MGI data infrastructure. |

The Materials Genome Initiative represents a transformative, collaborative framework for materials research in the United States. Through the coordinated, specialized efforts of NSF, NIST, DOE, and DOD, the MGI has cultivated a paradigm where an integrated Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII) supports a continuous feedback loop between simulation, data, and experiment [6] [17] [12]. This foundational principle of integration is what enables the accelerated discovery and deployment of advanced materials. The ongoing development of shared data protocols, trusted repositories, and advanced cyberinfrastructure ensures that this research paradigm continues to evolve. By educating a new generation of scientists in this integrated approach and tackling grand challenges through focused interagency programs, the MGI positions the U.S. to maintain its global leadership in materials science and technology, fueling innovation across critical sectors from energy and computing to national security and economic competitiveness [1].

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) is a multi-agency U.S. government initiative designed to advance a new paradigm for materials research and development. Its core mission is to discover, manufacture, and deploy advanced materials at twice the speed and a fraction of the cost of traditional methods [1]. Launched in 2011, the MGI aims to overcome the traditional, sequential approach of materials discovery, which often takes 10 to 20 years from conception to commercial deployment [2] [18]. The initiative fosters a tightly integrated research ecosystem where computation, data, experiment, and theory interact synergistically to accelerate progress [10].

In 2021, upon marking its first decade, the MGI released a new strategic plan to guide its efforts over the subsequent five years. This plan establishes three interconnected strategic goals to expand the initiative's impact [1]:

- Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII)

- Harness the power of materials data

- Educate, train, and connect the materials R&D workforce

This whitepaper delves into the technical specifics of this strategic plan, framing it within the fundamental principles of MGI research and providing a practical guide for researchers, scientists, and development professionals aiming to align their work with this accelerated framework.

Unifying the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII)

The first goal of the strategic plan focuses on creating a unified Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII), defined as a framework of integrated advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data [1]. This infrastructure is the bedrock of the MGI paradigm, enabling a closed-loop, high-throughput approach to materials science.

Core Principles and Definition

The MII is not merely a collection of tools, but an integrated system designed for interoperability. It provides the foundational resources—data, models, and experimental capabilities—that researchers need to accelerate materials development [1]. The vision is to create a seamless workflow where, for example, a computational researcher's model can be directly validated against high-throughput experimental data, the results of which then populate a shared database that informs the next cycle of computational design [10].

Key Technical Components and Methodologies

The development of a unified MII requires advances in several technical domains. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a key leader in the MGI, is actively working to establish the essential protocols and quality standards for this infrastructure [6] [18].

Table: Key Technical Components of the Materials Innovation Infrastructure

| Component | Description | Exemplary Projects & Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Data Exchange Protocols & Standards | Standards and formats that enable seamless sharing and integration of materials data from diverse sources. | Development of the Materials Resource Registry to help users discover relevant data resources [6]. |

| Multi-Scale Modeling & Simulation | Computational tools that bridge phenomena across different length and time scales, from quantum to continuum. | The µMAG (Micromagnetic Modeling Activity Group) establishes standard problems and reference software for micromagnetics [6]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | The use of automated, modular robotics to synthesize and characterize large libraries of materials rapidly. | The Advanced Composites Pilot at NIST develops new, energy-efficient materials for transportation using high-throughput methods [6]. |

| Integrated Workflows | Frameworks that combine computation, data, and experiment in a closed-loop, iterative manner. | The Center for Hierarchical Materials Design combined molecular modeling, evolutionary optimization, and small-angle X-ray scattering to deduce polymer nanostructures with unprecedented detail [10]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these components interact within an integrated MGI research paradigm, demonstrating the continuous feedback loop between simulation, data, and experiment.

Diagram 1: Integrated MGI Research Workflow showing the closed-loop interaction between computation, data, and experiment.

Case Study: Accelerated Organic Light-Emitting Diodes (OLED) Discovery

A seminal example of the MII in action is the work by Gomez-Bombarelli et al., which explored a space of 1.6 million potential OLED molecules [10]. The methodology involved:

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: Using a combination of quantum chemistry, cheminformatics, and machine learning to predict molecular properties.

- Data-Driven Down-Selection: The vast computational dataset was analyzed to identify a small subset of the most promising candidates.

- Targeted Experimental Synthesis & Characterization: The shortlisted molecules were synthesized and their performance (e.g., external quantum efficiency) was measured.

- Model Refinement: Experimental results were used to validate and refine the computational models.

This integrated approach resulted in the identification of new molecules with state-of-the-art performance, demonstrating a significant acceleration of the materials discovery pipeline [10].

Harnessing the Power of Materials Data

The second strategic goal recognizes that data is the lifeblood of the MGI. Harnessing its power involves addressing the entire data lifecycle—from generation and curation to sharing and analysis—to transform raw data into actionable knowledge and predictive models.

The Data Challenge in Materials Science

Traditional materials research often produces data that is siloed, inconsistently formatted, and poorly documented. This makes it difficult to reuse, combine, or extract broader insights. Key challenges include [2] [18]:

- Variable Data Quality: Data from different labs can be of highly variable quality and obtained using incompatible formats.

- Inaccessibility: Critical data is often held privately by companies or buried in unpublished research.

- Lack of Standardization: Without standards for data representation, it is difficult to link data from different scales (atomic to macro) or from different techniques.

Strategic Pillars for Data Management

To overcome these challenges, the MGI strategic plan and supporting efforts from agencies like NIST focus on several key pillars, which are summarized in the following table.

Table: Strategic Pillars for Materials Data Management

| Pillar | Objective | Implementation & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sharing & Curation | Make high-quality data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). | NIST maintains several Data Repositories, including the NIST Standard Reference Data program and the X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database, which provide critically evaluated scientific data [6]. |

| Data Quality & Metrology | Establish confidence in materials data and models through standardized measurement science. | NIST is developing new methods, metrologies, and capabilities necessary to assess the quality of materials data and models [6] [18]. |

| Advanced Data Analytics & Machine Learning | Extract hidden patterns and create predictive models from large, complex datasets. | Machine learning was used to screen 1.6M OLED molecules [10]. Data-mining has identified correlations in thermoelectric materials [10]. |

| Open Data Protocols | Encourage and facilitate the sharing of federally funded research data. | The White House and agencies have worked on open-access policies to make data from publicly funded research available to the community [2]. |

Educating, Training, and Connecting the Materials R&D Workforce

The third goal acknowledges that technological infrastructure and data are useless without a skilled workforce capable of leveraging them. This strategic goal focuses on developing human capital and fostering a collaborative community.

The Need for a New Skillset

The MGI paradigm requires a new breed of materials scientist and engineer—one who is not only an expert in a traditional domain (e.g., metallurgy or polymer science) but is also proficient in computational tools, data science, and collaborative, cross-disciplinary work [10]. The goal is to move from a culture of individual artisanship to one of integrated, team-based science.

Strategic Implementation and Programs

The 2021 plan calls for initiatives to:

- Integrate Computational and Data Skills into Curricula: Universities and training programs are encouraged to blend materials science education with instruction in coding, data analysis, and computational modeling.

- Promote Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration: The MGI inherently breaks down silos between chemistry, physics, engineering, and computer science. Funding programs, such as the NSF's Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF), are structured to require integrated teams of theorists, computational experts, and experimentalists [10].

- Develop Community Resources and Platforms: By creating shared databases, software tools, and online collaboratories, the MGI helps to connect researchers across institutions and sectors, fostering a more unified and efficient global materials community.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

For researchers embarking on MGI-aligned projects, the "toolkit" consists of both physical research reagents and, crucially, digital and computational resources. The following table details key components essential for operating within the Materials Innovation Infrastructure.

Table: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for MGI-Aligned Research

| Item / Solution | Category | Function in MGI Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursors | Chemical Reagents | Essential for synthesizing materials with precise compositions, especially in high-throughput experimentation where consistency is critical. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Measurement Standard | Certified materials provided by organizations like NIST used to calibrate instruments and validate experimental measurements, ensuring data quality and interoperability [6]. |

| Automated Synthesis Robotics | Experimental Equipment | Enables high-throughput creation of material libraries (e.g., polymers, alloys) by automating mixing, deposition, and reaction processes, dramatically accelerating the experimental loop [10]. |

| Multi-Scale Simulation Codes | Computational Tool | Software for modeling materials across scales (e.g., quantum mechanics, molecular dynamics, phase field) used for in silico design and screening before physical experimentation [18]. |

| Curated Materials Database | Data Resource | Repositories of critically evaluated data (e.g., crystal structures, phase diagrams, properties) used to train machine learning models and inform new designs [6] [10]. |

| Data Exchange Protocol | Software/Standard | A standardized format (e.g., specific to CALPHAD, microstructure) that allows different software and databases to communicate, which is fundamental to a unified MII [6]. |

The 2021 MGI Strategic Plan, with its three pillars of unifying infrastructure, harnessing data, and educating the workforce, provides a comprehensive roadmap for transforming materials science into a more predictive, accelerated, and collaborative discipline. The fundamental principle underpinning this initiative is the shift from a sequential, trial-and-error approach to an integrated, systems-level paradigm where computation, data, and experiment feed into and reinforce one another.

For researchers and drug development professionals, engaging with this paradigm means adopting the tools and collaborative mindset championed by the MGI. This includes leveraging shared digital resources, contributing to open data ecosystems, participating in cross-disciplinary teams, and continuously developing new skills at the intersection of materials science and data. By aligning with these strategic goals, the research community can collectively work towards realizing the MGI's ultimate vision: dramatically accelerating the deployment of advanced materials that address pressing challenges in healthcare, energy, national security, and beyond.

The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) represents a transformative paradigm in materials science, advancing a future where the discovery, manufacture, and deployment of advanced materials occurs twice as fast and at a fraction of the cost of traditional methods [1]. Drawing a powerful bio-inspired analogy, the "Materials Genome" conceptualizes the fundamental building blocks, structure-property relationships, and processing pathways of materials as an encodable genome. Just as the biological genome provides a blueprint for an organism, the materials genome encompasses the essential information that determines a material's characteristics and functions [10]. This framework is catalyzing a shift from empirical, trial-and-error research to an integrated, data-driven approach where theory, computation, and experiment synergistically interact to decode the complex sequences that give rise to materials performance.

This whitepaper examines the core principles of MGI research, framing them within the bio-inspired analogy to elucidate this transformative concept for researchers and drug development professionals. The MGI creates policy, resources, and infrastructure to support U.S. institutions in adopting methods for accelerating materials development, which is critical to sectors as diverse as healthcare, communications, energy, transportation, and defense [1]. By harnessing the power of materials data and unifying the materials innovation infrastructure, the MGI aims to ensure that the United States maintains global leadership in emerging materials technologies [1].

The Core Analogy: From Biological DNA to Materials Information

Deconstructing the Analogy: A Comparative Framework

The metaphor of a "genome" for materials is more than a superficial comparison; it establishes a robust conceptual framework for understanding and manipulating matter. The table below delineates the core components of this analogy, mapping biological concepts to their corresponding elements in materials science.

Table 1: Core Components of the Bio-inspired Analogy

| Biological Concept | Materials Science Equivalent | Description and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequence | Atomic Composition & Structure | The fundamental "code" specifying elemental identity, atomic arrangement, and bonding that defines a material's innate potential. |

| Gene Expression | Structure-Property Relationships | The process by which a given atomic/microstructure (genotype) manifests as observable macroscopic properties (phenotype), such as strength or conductivity. |

| Genetic Regulation | Processing Pathways | The external parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure, synthesis method) that "turn on" or "modulate" specific microstructures and, consequently, final properties. |

| Genomics | Materials Informatics | The high-throughput, data-driven science of acquiring, curating, analyzing, and modeling vast datasets to extract meaningful patterns and predictive insights. |

| Genetic Engineering | Materials Design & Optimization | The targeted manipulation of the "materials genome" (e.g., via alloying, defect engineering, or process control) to design new materials with tailored performance. |

The MGI Paradigm: A Closed-Loop Innovation Cycle

The operationalization of this analogy is embodied in the MGI's integrated paradigm, which moves beyond sequential workflows to create a tightly coupled, iterative cycle of discovery. This closed-loop system seamlessly integrates computation, data, and experiment, enabling a continuous refinement of understanding and acceleration of development [10]. The goal is a future where a researcher can submit a query to a user facility that synthesizes and characterizes a new class of materials in a high-throughput manner, with the results automatically populating a centralized database. This data can then be used by a computational researcher elsewhere to calibrate a new model, which in turn identifies optimal candidate structures for further experimental validation [10]. This vision represents the MGI paradigm at play, with initial pilot programs now emerging [6].

Quantitative Foundations: Data and Tools for Decoding the Genome

The MGI Strategic Plan: Foundational Goals

The 2021 MGI Strategic Plan formalizes the infrastructure needed to support this new paradigm, identifying three core goals to expand the initiative's impact over a five-year horizon [1]. These goals provide the structural framework for the entire MGI enterprise.

Table 2: The Three Strategic Goals of the Materials Genome Initiative (2021)

| Goal | Key Objectives | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Unify the Materials Innovation Infrastructure (MII) | Integrate advanced modeling, computational and experimental tools, and quantitative data into a connected framework [1]. | Provides a common platform and standards for researchers to share data and tools, breaking down silos and enabling collaboration. |

| 2. Harness the Power of Materials Data | Develop methods for data acquisition, representation, discovery, and curation to fuel AI and machine learning [1]. | Creates the "raw material" for data-driven science, allowing for the discovery of previously hidden structure-property relationships. |

| 3. Educate, Train, and Connect the R&D Workforce | Foster interdisciplinary skills and knowledge sharing across materials science, computation, and data science [1]. | Cultivates a new generation of scientists capable of working within the integrated MGI paradigm to solve complex challenges. |

Key Research Reagent Solutions: The Experimental Toolkit

The practical execution of MGI principles relies on a suite of advanced "research reagents"—both physical and digital—that form the essential toolkit for modern materials scientists. NIST plays a critical role in developing and providing these tools, establishing essential data exchange protocols and quality assessment methods [6].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Digital Tools for MGI Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in the MGI Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Synthesis Robotics | Experimental | Automates the creation of vast material libraries (e.g., polymers, alloys) under varying conditions, generating consistent data for the "materials genome" [10]. |

| Autonomous Experimentation (AE) Platforms | Experimental | Uses AI to control instrumentation, decide on next experiments based on real-time data, and rapidly converge on optimal materials or formulations without constant human intervention [1]. |

| CALPHAD (Calculation of Phase Diagrams) | Computational & Data | A critical computational method that uses thermodynamic databases to predict phase stability and microstructure, essential for designing alloys and other inorganic materials [6]. |

| NIST Standard Reference Data | Data | Provides critically evaluated scientific and technical data (e.g., XPS databases), serving as a trusted benchmark for validating models and experimental results [6]. |

| Materials Resource Registry | Data & Infrastructure | A registry system that bridges the gap between existing materials data resources and end-users, making it easier to discover and utilize relevant datasets [6]. |

| µMAG (Micromagnetic Modeling) | Computational & Standards | Provides a public reference implementation of micromagnetic software and standard problems, ensuring consistency and quality in model development and simulation [6]. |

Exemplary Protocols: The MGI in Action

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Virtual Screening of Organic Molecules

This methodology, exemplified by the discovery of novel organic light-emitting diode (OLED) molecules, demonstrates the power of computational screening to explore vast chemical spaces before any wet-lab experimentation begins [10].

- Define the Chemical Search Space: Identify the core molecular scaffolds and functional groups of interest. In the seminal work by Gomez-Bombarelli et al., this involved a space of 1.6 million candidate OLED molecules [10].

- High-Throughput Property Prediction: Utilize high-performance computing (HPC) to run quantum chemical calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) on all candidates to predict key properties such as excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and frontier molecular orbital levels.

- Data-Driven Model Calibration: Employ machine learning and cheminformatics to build surrogate models that correlate molecular structure (represented as descriptors or fingerprints) with the computed properties. This accelerates subsequent screening cycles.

- Inverse-Design Optimization: Apply an optimization algorithm (e.g., evolutionary algorithms) to navigate the chemical space and identify molecules that maximize or minimize a target property, such as external quantum efficiency.

- Candidate Selection and Flagging: Select a shortlist of the most promising candidate structures (e.g., the top 5). These candidates and their predicted data are flagged and published in an online, shareable database for the community [10].

- Experimental Validation and Feedback: Synthesize and characterize the flagged candidates. The experimental results (both successful and failed) are added back to the database, closing the loop and refining future computational models [10].

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop Inference of Nanoscale Structure

This protocol, developed by Khaira et al., combines physics-based simulation and experiment in a tightly integrated loop to deduce complex nanostructures, such as in self-assembled block copolymer films, with unprecedented detail [10].

- Initial Experimental Characterization: Synthesize the material (e.g., a block copolymer thin film) and characterize it using a high-throughput technique like small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) to obtain a 1D scattering profile.

- Physics-Based Model Generation: Create a physics-based molecular model (e.g., using self-consistent field theory) that can simulate the self-assembly process and predict the resulting nanostructure and its corresponding SAXS pattern.

- Iterative Optimization: Use an evolutionary optimization algorithm to iteratively adjust the simulation parameters (e.g., polymer chain length, interaction parameter, processing conditions).

- The algorithm generates a population of candidate structures.

- For each candidate, it computes a simulated SAXS pattern.

- It compares the simulated pattern to the experimental data.