The Complete Guide to gRNA Design: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Application in CRISPR Genome Editing

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the design and function of guide RNA (gRNA) in CRISPR systems.

The Complete Guide to gRNA Design: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Application in CRISPR Genome Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the design and function of guide RNA (gRNA) in CRISPR systems. It covers foundational concepts of gRNA biology and CRISPR mechanisms, then advances to methodological guides for diverse applications like gene knockout, knock-in, and modulation. The content details critical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing on-target efficiency and minimizing off-target effects, and concludes with rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of contemporary tools and libraries. By synthesizing established principles with the latest advancements, including AI-powered design and clinical trial insights, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to execute precise and effective genome editing experiments.

Understanding gRNA: The Core Component of CRISPR Precision

Deconstructing the Single Guide RNA (sgRNA) Molecule

The single guide RNA (sgRNA) is a fundamental, programmable component of the CRISPR-Cas system, responsible for directing the Cas nuclease to a specific target DNA sequence with precision. This synthetic, chimeric RNA molecule combines two natural RNA elements—the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA)—into a single strand, simplifying the CRISPR system for experimental and therapeutic applications [1] [2]. The sgRNA's primary function is to serve as a homing device, ensuring that the Cas nuclease creates a double-strand break at the intended genomic location. The design and functionality of the sgRNA are, therefore, critical to the success of any CRISPR experiment, framing the broader thesis that meticulous guide RNA design is paramount for optimizing on-target activity and minimizing off-target effects in CRISPR research [3].

Structural Anatomy of the sgRNA

The sgRNA molecule can be deconstructed into two primary functional domains:

Target-Specific Sequence (crRNA segment): This is a 20-nucleotide segment located at the 5' end of the sgRNA that defines the target site through Watson-Crick base pairing with the complementary DNA strand [2]. It is homologous to a specific region in the gene of interest, and its sequence is unique to each experimental target.

Cas Nuclease-Recruiting Scaffold (tracrRNA segment): This is a constant, structured RNA scaffold that follows the target-specific sequence. Its role is to bind directly to the Cas nuclease (such as Cas9), forming a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that is essential for the DNA cleavage activity [1] [2].

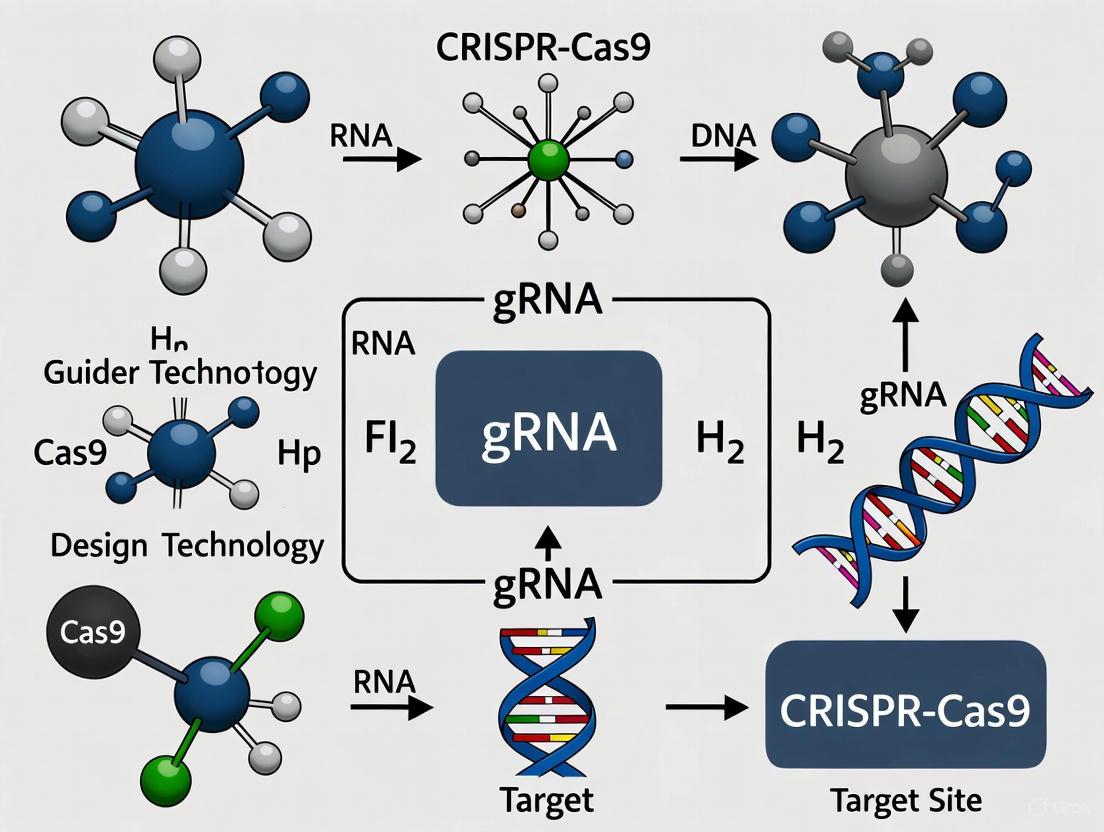

The relationship between these components and their interaction with the Cas nuclease and target DNA is illustrated below.

- The Critical Role of the PAM Sequence: It is crucial to recognize that the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, conserved DNA sequence (5'-NGG-3' for the commonly used S. pyogenes Cas9, or SpCas9) that is not part of the sgRNA molecule [4] [2]. The PAM is located directly adjacent to the 3' end of the DNA target sequence and is absolutely required for the Cas nuclease to recognize and bind to the target site [4] [1]. When designing an sgRNA, the 20-nucleotide target sequence is selected to be immediately upstream of the PAM sequence, but the PAM itself is not included in the final sgRNA construct [2].

Functional Mechanism: From sgRNA Expression to DNA Cleavage

The journey from sgRNA design to successful DNA editing follows a defined pathway. The following workflow outlines the key experimental and cellular steps, highlighting the central role of the sgRNA.

The mechanism of action begins after the sgRNA and Cas nuclease are delivered into a cell and form the RNP complex. The complex randomly interrogates genomic DNA. The Cas nuclease first checks for the presence of a compatible PAM sequence [4]. If the correct PAM (e.g., NGG) is present, it triggers local DNA melting, allowing the 20-nucleotide guide sequence of the sgRNA to form an R-loop structure by base-pairing with the target DNA strand [4] [5]. If the complementarity is sufficient, the Cas nuclease induces a double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [4] [2]. The cell then repairs this break through either the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in insertion or deletion mutations (indels) that disrupt the gene, or the precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, which can be co-opted to introduce specific edits using a donor DNA template [3] [5].

Strategic sgRNA Design for Research Applications

The universal "perfect sgRNA" does not exist; its optimal design is fundamentally dictated by the experimental goal [3]. Key design parameters vary significantly depending on whether the objective is a gene knockout, a precise knock-in, or transcriptional modulation.

Table 1: Key sgRNA Design Parameters for Different CRISPR Applications

| Application | Primary Goal | Critical Design Parameter | Recommended Target Location | Repair Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout | Disrupt gene function via indels [3] | On-target activity and specificity [3] | Early, essential exons; avoid protein termini [3] | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) [3] [5] |

| Gene Knock-in | Insert a new DNA fragment via HDR [3] | Proximity of cut site to the edit [3] | Immediate vicinity of the desired insertion point [3] | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [3] [5] |

| CRISPRa / CRISPRi | Activate or inhibit gene transcription [3] | Balance of complementarity and location [3] | Narrow window within the gene's promoter region [3] | N/A (Uses catalytically "dead" Cas9) |

Ensuring Specificity: Minimizing Off-Target Effects

A major challenge in sgRNA design is minimizing off-target activity, where the sgRNA directs cleavage at unintended genomic sites with sequence similarity to the target. Advanced algorithms have been developed to score sgRNAs for both on-target efficiency and off-target potential. For example, the scoring rules established by Doench et al. are implemented in many modern design tools to predict and minimize these effects [3]. Furthermore, a 2025 benchmark study highlighted that tools like the Vienna Bioactivity CRISPR (VBC) score can effectively predict sgRNA efficacy, and that using the top-scoring guides allows for the creation of smaller, more efficient genome-wide libraries without sacrificing performance [6].

Quantitative Evaluation of sgRNA Efficiency

Following the assembly of the CRISPR-Cas9 system and delivery into cells, it is critical to quantitatively evaluate the editing efficiency at the target site and assess potential off-target activity. Several methods exist, each with limitations.

The qEva-CRISPR method provides a robust, quantitative approach for evaluating CRISPR editing efficiency. This method is a ligation-based dosage-sensitive assay that allows for parallel (multiplex) analysis of a target site and its potential off-targets [5]. Unlike mismatch cleavage assays (e.g., T7E1), which can overlook single-nucleotide changes and large deletions, qEva-CRISPR detects all mutation types (indels, point mutations, large deletions) with high sensitivity and is not confounded by polymorphisms near the target site [5].

Table 2: Common Cas Nucleases and Their Corresponding PAM Sequences

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | The most commonly used nuclease; canonical PAM [4] [1] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRR(T/N) | Shorter protein, useful for viral delivery [4] |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | Creates staggered cuts; simplifies multiplexing [4] [1] |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN | Engineered high-fidelity variant with relaxed PAM [4] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | Another variant of the Cas12 family [4] |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-generated | Varies (Designed in silico) | AI-designed editor demonstrating comparable or improved activity/specificity [7] |

Experimental Protocol: qEva-CRISPR Workflow

The following is a generalized protocol based on the qEva-CRISPR method for quantifying editing efficiency [5]:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest transfected cells and isolate genomic DNA using a standard protocol.

- Probe Design: Design short oligonucleotide probes that are complementary to the target DNA region. Each probe set consists of two oligonucleotides that hybridize adjacently to the target sequence.

- Hybridization and Ligation: The probes are hybridized to the denatured genomic DNA. If the target sequence is perfectly complementary, the two probes will ligate, forming a single amplifiable fragment.

- PCR Amplification: The ligated products are amplified by PCR using universal fluorescently labeled primers.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: The PCR products are separated by size, and their peak intensities are quantified. The relative ratio of the peak corresponding to the edited allele versus the wild-type allele provides a quantitative measure of editing efficiency.

This method's key advantage is its ability to distinguish between different allelic states (wild-type, heterozygous, homozygous) and even between NHEJ and HDR products in a single, multiplex reaction [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for sgRNA Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for sgRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Utility in sgRNA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System | Provides synthetic sgRNAs and Cas enzyme [1] | Enables formation of RNP complexes for highly specific editing with reduced off-target effects. |

| Guide-it sgRNA In Vitro Transcription Kit | sgRNA synthesis and production [2] | Generates high-yield sgRNAs from a PCR-derived template for testing and transduction. |

| Guide-it sgRNA Screening Kit | Pre-transduction efficiency validation [2] | Allows for robust in vitro assessment of sgRNA activity before resource-intensive cell work. |

| qEva-CRISPR Assay | Quantitative evaluation of editing efficiency [5] | Provides a sensitive, multiplexable method to quantify INDELs and distinguish repair pathways. |

| Synthego Halo Platform & CRISPR Design Tool | sgRNA design and synthetic guide RNA production [4] [3] | Automates guide design for knockouts and provides high-quality synthetic RNAs for screening. |

The field of sgRNA design and CRISPR technology is rapidly evolving. The discovery and engineering of novel Cas nucleases with diverse PAM specificities continue to expand the targeting range of CRISPR systems [4] [7]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence is paving the way for a new generation of genome editors. For instance, AI-designed proteins like OpenCRISPR-1 demonstrate that it is possible to create highly functional editors with optimal properties that are hundreds of mutations away from any known natural protein [7]. These advances, coupled with the development of more sophisticated sgRNA design algorithms and benchmarking studies [6], promise to further enhance the precision and broaden the therapeutic applicability of CRISPR-based technologies.

In conclusion, the single guide RNA molecule is the linchpin of CRISPR genome engineering, conferring both specificity and programmability. A deep understanding of its structure, functional mechanism, and design principles is non-negotiable for researchers aiming to harness this powerful technology. As the field progresses, the interplay between computational design, empirical validation, and the development of novel reagents will continue to drive innovations, enabling more precise and effective genetic interventions in basic research and clinical therapeutics.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their associated protein (Cas-9) represent a revolutionary genome editing tool derived from an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [8]. This system enables organisms to defend themselves against viruses or bacteriophages by incorporating fragments of foreign DNA into their own genome, which subsequently serves as a guide to recognize and cleave invading genetic material [8] [9]. The significance of CRISPR-Cas9 in modern biotechnology stems from its remarkable efficiency, accuracy, and ease of design compared to previous gene-editing technologies like Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) [8] [10]. Whereas these earlier methods required complex protein engineering for each new target, CRISPR-Cas9 can be redirected to different genomic locations simply by redesigning the guide RNA (gRNA) component [10]. This programmability has made CRISPR-Cas9 the most widely adopted genome editing platform across diverse disciplines including medicine, agriculture, and basic research [8].

The CRISPR-Cas system is categorized into two main classes (Class I and Class II) and several types (I-VI) based on their architecture and Cas protein composition [9]. The Type II CRISPR-Cas system, from which the CRISPR-Cas9 tool is derived, is characterized by the signature Cas9 protein and falls under Class II systems that utilize a single Cas protein for effector functions [9]. This relative simplicity has made Type II systems particularly amenable for adaptation as a programmable genome editing tool [8]. The core components of the engineered CRISPR-Cas9 system include the Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), which have been optimized from the natural system that originally comprised separate crRNA and tracrRNA molecules [8] [11] [12].

Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The Cas9 Nuclease: A Programmable Molecular Scissor

The Cas9 protein serves as the executive component of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, functioning as a programmable DNA endonuclease that creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations [8]. The most commonly used Cas9 protein is derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), consisting of 1,368 amino acids that form a multi-domain architecture [8] [10]. Structurally, Cas9 comprises two primary lobes: the recognition lobe (REC) and the nuclease lobe (NUC) [8]. The REC lobe, containing REC1 and REC2 domains, is primarily responsible for binding the guide RNA [8]. The NUC lobe contains three critical domains: the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand; the HNH domain, which cleaves the complementary DNA strand; and the PAM-interacting domain, which recognizes a specific short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [8] [10].

The PAM sequence is essential for target recognition and varies depending on the bacterial source of the Cas9 protein [11] [13]. For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide base [8] [10]. This requirement means that potential target sites in the genome must be adjacent to this short sequence, which influences where in the genome CRISPR-Cas9 can be targeted [10]. The PAM recognition mechanism serves as an important safety feature that prevents the Cas9 nuclease from attacking the bacterial genome itself, as the CRISPR array in the host genome lacks these adjacent PAM sequences [8].

Guide RNA: The Targeting Component

The guide RNA (gRNA) constitutes the target-recognition component of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, dictating its specificity and precision [8] [11]. In its natural context, the CRISPR system utilizes two separate RNA molecules: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains the target-complementary sequence, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [8] [12]. For experimental applications, these two elements are typically combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) molecule through a synthetic linker [11] [12]. This sgRNA chimera maintains the functionality of the natural two-RNA system while offering greater experimental convenience [12].

The sgRNA consists of two critical regions [11]:

- The target-specific sequence (crRNA-derived, 17-20 nucleotides): A customizable region that determines genomic targeting through Watson-Crick base pairing with the target DNA.

- The scaffold sequence (tracrRNA-derived): A structural component that binds to the Cas9 protein and facilitates the formation of an active ribonucleoprotein complex.

The sgRNA's target-specific sequence must be complementary to the genomic target immediately upstream of the PAM sequence [10]. The design of this targeting region is paramount to the success of CRISPR experiments, as it directly influences both on-target efficiency and off-target effects [11] [13] [12].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Structure | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Multi-domain protein with REC and NUC lobes | Creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA | Requires PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9); Contains RuvC and HNH nuclease domains |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | chimeric RNA molecule with target-specific and scaffold regions | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic locations | 17-20 nt target sequence; Scaffold binds Cas9; Determines system specificity |

| PAM Sequence | Short DNA sequence (2-5 bp) | Recognition signal for Cas9 binding | Prevents autoimmunity in bacteria; Restricts potential target sites |

Molecular Mechanism of gRNA-Directed DNA Cleavage

The CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing mechanism can be systematically divided into three sequential stages: recognition, cleavage, and repair [8]. Each stage involves precise molecular interactions between the gRNA, Cas9 protein, and target DNA that ultimately result in targeted genetic modifications.

Target Recognition and Binding

The process initiates with the formation of the Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex, wherein the sgRNA binds to the Cas9 protein, inducing a conformational change that activates the nuclease for DNA binding [10]. This complex then surveys the genome for potential target sites by scanning for the presence of the appropriate PAM sequence [8]. Once Cas9 identifies a PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9), it triggers local DNA melting, enabling the formation of an RNA-DNA hybrid between the sgRNA's target-specific region and the complementary DNA strand [8] [10].

The annealing process proceeds directionally from the 3' end of the gRNA (adjacent to the PAM) toward the 5' end [10]. The seed sequence—an 8-10 nucleotide region at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence—plays a particularly critical role in target recognition [10]. Mismatches within this seed region are far more detrimental to Cas9 cleavage activity than mismatches in the distal 5' region, highlighting the importance of precise complementarity in this segment [10]. This PAM-dependent binding mechanism ensures that Cas9 only engages with DNA sites that contain both the correct adjacent motif and sufficient complementarity to the gRNA spacer sequence [8].

DNA Cleavage Mechanism

Following successful target recognition and hybridization, Cas9 undergoes a second conformational change that positions its nuclease domains for DNA cleavage [10]. The HNH domain cleaves the complementary DNA strand that is hybridized to the gRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand [8] [10]. This coordinated action results in a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [8] [10].

The cleavage efficiency is influenced by multiple factors, including the degree of complementarity between the gRNA and target DNA, the chromatin accessibility of the target region, and specific sequence features of the gRNA [10] [12]. Structural studies indicate that the accessibility of the seed region at the 3' end of the gRNA is particularly important for efficient cleavage, as impaired accessibility in this region significantly reduces CRISPR activity [12].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Cleavage Mechanism. The process begins with Cas9-sgRNA complex formation and proceeds through PAM recognition, DNA melting, and sequential cleavage by HNH and RuvC nuclease domains, resulting in a double-strand break repaired by cellular mechanisms.

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

The cellular response to CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks determines the final editing outcome. Eukaryotic cells possess two primary pathways for repairing DSBs: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [8] [10].

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is the dominant and more efficient repair pathway in most cells, operating throughout the cell cycle without requiring a repair template [8]. This pathway directly ligates the broken DNA ends but is inherently error-prone, often resulting in small random insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [8] [10]. When these indels occur within the coding sequence of a gene, they can produce frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons, effectively knocking out the target gene [10]. This makes NHEJ particularly useful for gene knockout applications.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a more precise repair mechanism that requires a homologous DNA template and is most active during the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [8]. In CRISPR applications, researchers can exploit this pathway by providing an exogenous donor DNA template containing desired modifications flanked by homology arms complementary to the region surrounding the cleavage site [8] [10]. This enables precise gene insertion or specific nucleotide changes, making HDR valuable for gene correction or knock-in experiments [10]. However, HDR is generally less efficient than NHEJ and requires more sophisticated experimental design [8].

Table 2: DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

| Repair Pathway | Mechanism | Efficiency | Editing Outcomes | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Direct ligation of broken ends without template | High (active throughout cell cycle) | Random insertions/deletions (indels) | Gene knockouts, Gene disruption |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Repair using homologous DNA template | Low (active in S/G2 phases) | Precise nucleotide changes, Gene insertions | Gene correction, Gene knock-in, Precise edits |

Guide RNA Design Principles and Optimization

The design of the guide RNA is arguably the most critical determinant of success in CRISPR experiments, directly influencing both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity [11] [13] [12]. Advances in bioinformatics and machine learning have identified numerous sequence and structural features that characterize highly functional sgRNAs.

Sequence-Based Design Parameters

The target-specific sequence of the sgRNA must satisfy several key parameters to ensure optimal performance. First and foremost, the sequence must be unique within the genome to minimize off-target effects [13]. This requires thorough genome-wide homology analysis to identify sequences with minimal similarity to other genomic regions, particularly those with few mismatches, especially in the seed region adjacent to the PAM [13] [12].

The nucleotide composition of the guide sequence significantly impacts cleavage efficiency. While early designs emphasized the importance of GC content, contemporary research indicates that optimal GC content falls between 40-80%, with extremes at either end associated with reduced activity [11] [12]. Functional sgRNAs are characterized by specific nucleotide preferences at particular positions relative to the PAM [12]. For instance, positions adjacent to the PAM are significantly depleted of cytosines and thymines in highly active guides [12].

The presence of certain sequence motifs can also impair sgRNA functionality. Repetitive nucleotides, particularly four contiguous guanines (GGGG), are associated with poor CRISPR activity due to both synthetic challenges during oligo production and their propensity to form complex secondary structures like G-quadruplexes [12]. Similarly, stretches of uracils (especially UUU in the seed region) can act as premature termination signals for RNA Polymerase III, which typically drives sgRNA expression from U6 promoters [12].

Structural Considerations in gRNA Design

Beyond primary sequence, the secondary structure of the sgRNA plays a crucial role in determining CRISPR efficiency [12]. The structural accessibility of the seed region (positions 18-20 at the 3' end of the guide sequence) is particularly important, as impaired accessibility in this region significantly reduces cleavage activity [12]. Highly functional sgRNAs demonstrate greater accessibility in these terminal positions, facilitating optimal interaction with the target DNA [12].

The self-folding free energy of the guide sequence itself is another important structural parameter. Guide sequences with high propensity to form stable secondary structures (more negative ΔG values) typically show reduced activity, with non-functional sgRNAs having significantly lower free energy (ΔG = -3.1) compared to functional ones (ΔG = -1.9) [12]. This relationship highlights the importance of selecting target sequences with minimal self-complementarity to ensure the guide region remains accessible for hybridization with the target DNA.

Additionally, the stability of the RNA-DNA heteroduplex formed between the sgRNA and target DNA influences cleavage efficiency. Contrary to what might be intuitively expected, extremely stable heteroduplexes (with more negative ΔG values) are characteristic of less functional sgRNAs, with non-functional guides forming more stable duplexes (ΔG = -17.2) than functional ones (ΔG = -15.7) [12]. This suggests that moderate binding affinity may allow for the necessary proofreading and rejection of off-target sites.

Advanced Design Considerations and AI Approaches

Recent advances in gRNA design have incorporated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to improve prediction accuracy of both on-target efficiency and off-target effects [14]. These models leverage large-scale CRISPR screening data to identify complex patterns and relationships that may not be apparent through traditional rule-based approaches [14].

State-of-the-art tools like CRISPRon integrate sequence features with epigenomic information such as chromatin accessibility to predict Cas9 knockout efficiency with improved accuracy [14]. Similarly, multitask learning approaches simultaneously model both on-target and off-target activities, enabling the design of guides that balance high efficiency with minimal off-target risk [14]. These models have revealed that certain GC-rich motifs might boost on-target cutting but simultaneously increase off-target propensity, highlighting the complex trade-offs in guide optimization [14].

Explainable AI (XAI) techniques are increasingly being applied to interpret these predictive models, providing insights into which nucleotide positions contribute most significantly to guide activity and specificity [14]. These interpretability approaches not only build confidence in the models but can also reveal biologically meaningful patterns, such as sequence motifs that affect Cas9 binding or cleavage [14].

Diagram 2: gRNA Design and Optimization Workflow. The process involves identifying PAM sites, generating candidate guides, evaluating both on-target efficiency and off-target risks using multiple parameters, and applying AI-driven optimization to select the final guide.

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow

gRNA Design and Synthesis

The initial step in any CRISPR experiment involves the computational design and physical synthesis of guide RNAs targeting the gene of interest. The following protocol outlines the standard workflow for gRNA design and preparation:

Target Identification: Select a target region within your gene of interest that contains a PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) positioned appropriately for your desired edit [13] [10]. For gene knockouts, target sequences near the 5' end of the coding sequence are preferred to maximize the probability of generating frameshift mutations [13].

gRNA Design: Use established bioinformatics tools such as CRISPick, CHOPCHOP, or CRISPOR to identify potential gRNA sequences [11] [13]. These tools employ various scoring algorithms (Rule Set 2, CRISPRscan, Lindel) to predict on-target efficiency and off-target effects [13]. Select 3-5 candidate gRNAs with high predicted efficiency and minimal off-target risks for experimental validation.

gRNA Synthesis: Choose an appropriate synthesis method based on your experimental needs [11]:

- Plasmid-expressed sgRNA: Clone the gRNA sequence into a plasmid vector under a U6 promoter for stable expression in cells. This method requires 1-2 weeks for cloning but provides sustained gRNA expression [11].

- In vitro transcription (IVT): Transcribe gRNA from a DNA template using T7 RNA polymerase. This approach takes 1-3 days but may yield lower-quality RNA requiring additional purification steps [11].

- Chemical synthesis: Synthesize gRNA through solid-phase chemical synthesis, resulting in high-purity RNA suitable for sensitive applications. Synthetic sgRNA offers advantages including higher editing efficiency, reduced off-target effects, and lot-to-lot consistency [11].

Delivery Methods and Validation

Following gRNA preparation, the next critical steps involve delivering the CRISPR components to target cells and validating the resulting edits:

Component Delivery: Co-deliver the Cas9 nuclease and gRNA to your target cells using appropriate methods [10]:

- Transfection: For cell lines with high transfection efficiency, use plasmid DNA or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Viral transduction: For primary cells or in vivo applications, use lentiviral or adenoviral vectors for efficient delivery.

- Microinjection: For zygotes or single cells, use direct microinjection of RNP complexes.

Editing Validation: After allowing time for editing and repair (typically 48-72 hours), validate the genetic modifications [10]:

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplify the target region and perform Sanger or next-generation sequencing to detect indels.

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay: Use mismatch-sensitive enzymes to detect and quantify editing efficiency.

- Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE): Analyze sequencing chromatograms to quantify editing efficiency and characterize mutation spectra.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | SpCas9, SaCas9, SpCas9-NG, xCas9 | DNA cleavage with different PAM specificities | Genome editing with varying PAM requirements |

| gRNA Formats | Plasmid-expressed, IVT, Synthetic sgRNA | Target recognition and Cas9 guidance | Different experimental setups and efficiency requirements |

| Design Tools | CRISPick, CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR | gRNA selection and optimization | Predicting efficiency and specificity before synthesis |

| Delivery Systems | Plasmid transfection, RNP electroporation, Lentiviral transduction | Introducing CRISPR components into cells | Different cell types and experimental contexts |

| Detection Kits | T7EI assay, TIDE analysis, NGS platforms | Validation of editing efficiency | Quantifying and characterizing genetic modifications |

The CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a paradigm shift in genome editing technology, with the guide RNA serving as the programmable component that dictates its remarkable specificity. The mechanism by which gRNA directs targeted DNA cleavage involves a sophisticated interplay of molecular recognition, structural rearrangement, and precise enzymatic activity [8] [10]. The guide RNA's target-specific sequence hybridizes with complementary DNA, positioning the Cas9 nuclease to create double-stranded breaks at predetermined genomic locations [8]. Understanding the principles governing gRNA design—including sequence composition, structural accessibility, and specificity considerations—is fundamental to harnessing the full potential of this technology [11] [13] [12].

Ongoing advancements in gRNA design methodologies, particularly the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, continue to refine our ability to predict and optimize CRISPR activity [14]. These developments, coupled with engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities and improved fidelity, are expanding the targeting scope and safety profile of CRISPR-based applications [10] [14]. As our understanding of gRNA biology deepens, CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to drive further innovations across diverse fields including therapeutic development, agricultural improvement, and basic biological research [8]. The continued elucidation of gRNA function and optimization of design principles will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities for precise genetic manipulation, solidifying CRISPR-Cas9's position as a transformative technology in the life sciences.

The CRISPR-Cas system, an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, has been repurposed as a revolutionary genome-editing tool. Its core function relies on the precise interaction between nucleic acid targeting elements and effector nucleases [15]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a nuanced understanding of the fundamental components—crRNA, tracrRNA, and Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sites—is critical for designing effective experiments and therapeutic strategies. These components collectively determine the specificity and efficiency of DNA target recognition and cleavage, forming the foundation upon which all advanced CRISPR applications are built [16] [17]. The simplicity of the CRISPR system, where target specificity is programmed by a short RNA sequence rather than protein engineering (as required by earlier technologies like ZFNs and TALENs), is the key feature that has accelerated its widespread adoption [18].

Core Terminology and Molecular Anatomy

crRNA (CRISPR RNA)

The crRNA is a short, customizable RNA molecule, typically 17-20 nucleotides in length, that defines the genomic target sequence through Watson-Crick base-pairing [11] [16]. It is the component that provides the "address" for the Cas nuclease by containing the spacer sequence complementary to the foreign DNA acquired during the adaptive immune response in bacteria [15] [17]. In natural CRISPR systems, the crRNA is processed from a long precursor transcript containing repeat-spacer arrays [17].

tracrRNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA)

The tracrRNA is a non-coding RNA that serves as a scaffold for Cas nuclease binding [11] [18]. It is essential for the maturation of crRNA in the native Type II CRISPR system and facilitates the formation of the effector complex [17]. The tracrRNA contains a stem-loop structure that is recognized by the Cas9 protein, acting as a handle that anchors the guide RNA to the nuclease [18].

sgRNA (Single-Guide RNA)

The sgRNA is a synthetic fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA, connected by a linker loop [11] [16]. This chimeric RNA molecule combines the target-specificity of crRNA with the structural scaffolding function of tracrRNA, simplifying the system to a two-component setup (Cas protein and sgRNA) for laboratory applications [16] [18]. The development of sgRNA was a pivotal innovation that dramatically simplified CRISPR experimental design [17].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of CRISPR Guide RNA Components

| Component | Full Name | Primary Function | Length & Characteristics | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| crRNA | CRISPR RNA | Specifies target DNA sequence via complementarity | 17-20 nt spacer sequence | Natural/Engineered |

| tracrRNA | trans-activating CRISPR RNA | Binds Cas protein; facilitates crRNA maturation | Scaffold with stem-loop structures | Natural/Engineered |

| sgRNA | Single-Guide RNA | Combines crRNA and tracrRNA functions into one molecule | ~100 nt synthetic RNA chimera | Engineered for research |

PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif)

The PAM is a short, nuclease-specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that must be present immediately adjacent to the target sequence for Cas protein recognition and cleavage [15] [10]. The PAM sequence is not part of the guide RNA and is not targeted for cleavage, but serves as a critical "self vs. non-self" discrimination signal that prevents the CRISPR system from targeting the bacterial genome itself [16] [17]. Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, which fundamentally constrains their targetable genomic space [19].

Diagram 1: Assembly of sgRNA from crRNA and tracrRNA

Cas Nuclease Specificity and PAM Requirements

The Molecular Basis of PAM Recognition

The PAM-interacting domain (PID) within the Cas protein is responsible for recognizing the specific PAM sequence in the target DNA [18]. For the widely used SpCas9 (from Streptococcus pyogenes), this domain recognizes a short 5'-NGG-3' sequence on the non-target DNA strand, where "N" can be any nucleotide base [10] [19]. This initial PAM recognition triggers local DNA melting, allowing the guide RNA to base-pair with the target DNA strand [18]. If complementarity is sufficient, particularly in the seed sequence (8-12 bases adjacent to the PAM), the Cas nuclease undergoes a conformational change that activates its cleavage domains [10] [20].

PAM-Dependent Target Specificity Across Cas Variants

Different Cas nucleases exhibit distinct PAM requirements, which directly impacts their targeting scope and applications [15] [19]. The PAM sequence essentially functions as a primary licensing signal—without its presence, Cas cleavage cannot occur, even with perfect guide RNA complementarity [17].

Table 2: PAM Requirements and Characteristics of Commonly Used Cas Nucleases

| Cas Nuclease | Source Organism | PAM Sequence | PAM Location | Cleavage Pattern | Size (aa) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 5'-NGG-3' | 3' | Blunt ends | 1368 | Standard gene editing; most widely used |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | 5'-NNGRRT-3' | 3' | Blunt ends | 1053 | In vivo applications (fits in AAV) |

| NmCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | 5'-NNNNGATT-3' | 3' | Blunt ends | 1082 | Editing in regions with specific sequence contexts |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Francisella novicida | 5'-TTN-3' | 5' | Staggered ends | 1300 | Multiplexing; HDR applications |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered (Cas12i) | 5'-TN-3' | 5' | Staggered ends | 1080 | Therapeutic development; high fidelity |

| SpRY | Engineered (SpCas9) | 5'-NRN > NYN-3' | 3' | Blunt ends | ~1368 | Near-PAMless editing; maximal targeting flexibility |

Engineered Cas Variants with Altered PAM Specificities

The limitation imposed by natural PAM requirements has driven the development of engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities [10] [19]. For example:

- xCas9: Recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs with increased fidelity [10]

- SpCas9-NG: Recognizes NG PAMs with improved activity [10]

- SpG: Recognizes NGN PAMs with increased nuclease activity [10]

- SpRY: Functions as a near-PAMless nuclease, recognizing NRN and NYN PAMs (where R = A/G and Y = C/T) [21] [10]

These engineered variants significantly expand the targetable genomic space, enabling editing in regions previously inaccessible with wild-type nucleases [10] [19].

Diagram 2: PAM-Mediated Target Recognition and Cleavage

Experimental Protocols for PAM Characterization and Guide RNA Validation

GenomePAM: A Method for Direct PAM Characterization in Mammalian Cells

Characterizing PAM requirements is essential for developing and utilizing novel Cas nucleases. The GenomePAM method enables direct PAM characterization in mammalian cells by leveraging genomic repetitive sequences as natural target libraries [21].

Protocol Steps:

- Identification of Genomic Repeats: Select highly repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu elements) with diverse flanking sequences. For example, sequence 5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′ (Rep-1) occurs ~8,471 times in the human haploid genome with nearly random flanking sequences [21].

- gRNA Construction: Clone the repeat sequence (Rep-1 for 3' PAM nucleases like SpCas9; Rep-1RC for 5' PAM nucleases like FnCas12a) into a guide RNA expression cassette [21].

- Delivery System: Co-transfect mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T) with plasmids encoding the candidate Cas nuclease and the repeat-targeting gRNA [21].

- Capture of Cleavage Events: Adapt the GUIDE-seq method to identify cleaved genomic sites by capturing double-strand oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN)-integrated fragments through anchor multiplex PCR sequencing (AMP-seq) [21].

- PAM Identification: Analyze cleaved sites to identify the flanking PAM sequences. The unknown PAM is initially set as "NNNNNNNNNN" during sequencing analysis, and significant motifs are identified through iterative "seed-extension" computational methods [21].

- Validation: Stratify results by perfect-match and mismatch targets to determine PAM stringency and assess potential off-target effects [21].

Guide RNA Design and Validation Workflow

Optimal guide RNA design is critical for successful CRISPR experiments and requires careful consideration of multiple parameters [3].

Protocol Steps:

- Target Selection: Identify the genomic region of interest based on experimental goal (knockout, knock-in, activation, repression) [3].

- PAM Identification: Scan the target region for available PAM sequences compatible with your selected Cas nuclease [10] [3].

- Guide Sequence Design: Select a 17-23 nucleotide target sequence immediately adjacent to the PAM with the following considerations:

- Off-Target Assessment: Use computational tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder, Synthego Design Tool) to predict and minimize potential off-target sites [11] [3].

- Synthesis and Delivery: Choose appropriate sgRNA format (synthetic, IVT, or plasmid-expressed) based on experimental needs [11].

- Validation: Assess editing efficiency and specificity using targeted sequencing and off-target detection methods (e.g., GUIDE-seq, targeted amplicon sequencing) [21] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Variants | SpCas9, SaCas9, hfCas12Max, eSpOT-ON | DNA recognition and cleavage; different variants offer trade-offs in size, fidelity, and PAM requirements | Select based on PAM availability, delivery constraints (e.g., AAV size limit), and fidelity requirements [10] [19] |

| Guide RNA Formats | Synthetic sgRNA, IVT sgRNA, Plasmid-expressed sgRNA | Direct Cas nuclease to specific genomic targets | Synthetic sgRNA offers highest consistency and lowest off-target effects; plasmid-based enables stable expression [11] |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation | Introduce CRISPR components into target cells | AAV has limited cargo capacity; LNPs suitable for RNP delivery; method impacts efficiency and cell viability [19] [17] |

| Design Tools | Synthego Design Tool, Benchling, CHOPCHOP | Predict optimal guide RNA sequences with high on-target and low off-target activity | Tools use algorithms (e.g., "Doench rules") to score guides; species-specific designs available [11] [3] |

| Off-Target Assessment | GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, Targeted Amplicon Sequencing | Identify and quantify unintended editing events | Essential for therapeutic applications; sensitivity varies by method [21] [20] |

| HDR Donor Templates | ssODN, dsDNA with homology arms | Enable precise gene editing through homology-directed repair | Design with ~800bp homology arms for dsDNA; position cut site close to edit [16] [3] |

The precise interplay between crRNA, tracrRNA, and PAM sites forms the molecular foundation of Cas nuclease specificity in CRISPR systems. For research and therapeutic development, understanding these core components enables rational design of CRISPR experiments, from selecting appropriate Cas variants with compatible PAM requirements to designing highly specific guide RNAs. The ongoing development of engineered Cas proteins with expanded PAM recognition and enhanced fidelity continues to broaden the applicability of CRISPR technologies while mitigating limitations such as off-target effects. As these tools evolve, they promise to unlock new possibilities in functional genomics and therapeutic genome editing, provided researchers maintain a rigorous understanding of these fundamental principles governing CRISPR specificity and function.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system has revolutionized genetic engineering, offering an unprecedented ability to modify genomes with high precision. At the core of this technology lies the guide RNA (gRNA), a programmable component that dictates the specificity and efficiency of CRISPR-mediated edits. The gRNA functions as a molecular GPS, directing the Cas nuclease to specific genomic loci through complementary base pairing [11]. In bacterial adaptive immunity, the natural CRISPR system utilizes two separate RNA molecules—the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) for target recognition and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) for Cas nuclease complex formation [22]. For biotechnological applications, these are typically combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) molecule, simplifying delivery and implementation [11]. This technical guide examines the critical role of gRNA design across diverse CRISPR applications, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for optimizing experimental outcomes in genome engineering projects.

Fundamental Components of CRISPR gRNAs

Structural Architecture of Guide RNAs

The functional gRNA comprises two essential structural components: the target-specific spacer sequence and the scaffold region. The spacer sequence consists of 17-20 nucleotides located at the 5' end of the gRNA that are complementary to the target DNA site, determining specificity through Watson-Crick base pairing [11]. This sequence must be carefully designed to match the target locus while minimizing off-target effects. The scaffold region represents the remaining portion of the gRNA that forms a complex secondary structure essential for Cas nuclease binding and stabilization [22] [11]. In sgRNA configurations, a synthetic linker loop connects these functional domains, creating a single RNA molecule that streamlines experimental implementation [11].

Table 1: Core Components of a Single Guide RNA (sgRNA)

| Component | Length | Function | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spacer Sequence | 17-20 nt | Targets specific DNA locus via complementarity | Perfect complementarity to target site required; begins with G if using U6 promoter |

| Linker Loop | ~4 nt | Connects crRNA and tracrRNA components in sgRNA | Minimal sequence requirements; maintains structural flexibility |

| tracrRNA Scaffold | ~42 nt | Binds Cas nuclease; enables complex activation | Highly conserved sequence; critical for Cas9 conformational change |

PAM Requirements and Cas Nuclease Compatibility

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) represents a critical determinant in gRNA design, serving as a recognition sequence that must be present immediately adjacent to the target site for successful Cas nuclease binding and cleavage [22]. Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, constraining the genomic loci available for targeting. The most widely implemented Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence located directly 3' of the target site [22] [23]. Emerging Cas variants recognize diverse PAM sequences, significantly expanding the targetable genomic landscape. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) recognizes 5'-NNGRR(N)-3', while Cas12 nucleases exhibit different PAM preferences such as 5'-TN-3' or 5'-(T)TNN-3' [11]. The PAM sequence itself is not included in the gRNA design but must be present in the target genomic DNA [11].

Diagram 1: gRNA and PAM in CRISPR Complex. The gRNA directs the Cas nuclease to the target DNA, with PAM recognition required for activation.

gRNA Design Principles for Specific CRISPR Applications

Gene Knockout via Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

CRISPR-mediated gene knockout represents the most straightforward application, leveraging the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway to introduce frameshift mutations that disrupt gene function [3] [23]. Successful knockout strategies require careful positioning of gRNA target sites within protein-coding exons, prioritizing regions where indels will maximally disrupt protein function. Optimal gRNAs for knockout experiments target exonic regions between 5-65% of the protein-coding sequence, avoiding domains near the N-terminus where alternative start codons might restore function and C-terminal regions that might encode non-essential protein domains [3] [23]. With potential target sites occurring approximately every 8 nucleotides in a 1 kilobase gene, researchers can select gRNAs with optimized on-target activity scores while maintaining positional constraints [23].

Table 2: gRNA Design Parameters by CRISPR Application

| Application | Primary Repair Mechanism | Optimal Target Location | Sequence Priority | Key Design Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout | NHEJ | 5-65% of protein coding region | High on-target activity | Avoid N/C-terminal regions; maximize indel potential |

| Knock-in/HDR | HDR | <30 bp from edit site | Location-critical | Proximity to edit overrides sequence optimization |

| CRISPRa | dCas9-Fusion Recruitment | ~100 bp upstream of TSS | Balance of location and sequence | Requires precise TSS annotation; FANTOM database recommended |

| CRISPRi | dCas9-Fusion Recruitment | ~100 bp downstream of TSS | Balance of location and sequence | Same TSS precision requirements as CRISPRa |

| Base Editing | DNA Deamination | Within 5-10 bp window of PAM | Location-critical | Narrow editing window; potential bystander edits |

Precision Genome Editing via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Precision editing through homology-directed repair (HDR) enables the introduction of specific genetic changes, including point mutations, epitope tags, and gene insertions [22] [23]. Unlike knockout approaches, HDR experiments impose stringent locational constraints on gRNA design, as cutting efficiency decreases dramatically when the double-strand break occurs more than 30 nucleotides from the intended edit site [23]. This locational priority means researchers must often compromise on gRNA sequence quality when only suboptimal targets are available near the desired edit. Successful HDR experiments typically employ single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) as repair templates for small edits (<200 nucleotides), with the PAM site centered in the ssODN and incorporating silent mutations to prevent re-cleavage after editing [22]. For larger inserts (>200 nucleotides), double-stranded DNA templates with extended homology arms (up to 800 bp) are recommended [22].

Gene Regulation via CRISPRa and CRISPRi

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and interference (CRISPRi) technologies repurpose nuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional regulators to fine-tune gene expression without altering DNA sequence [3] [23]. These approaches demand precision targeting of promoter-proximal regions, with CRISPRa requiring gRNAs within a ~100 nucleotide window upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) and CRISPRi operating most effectively within a ~100 nucleotide window downstream of the TSS [23]. Accurate TSS annotation is critical, with the FANTOM database (which utilizes CAGE-seq data) providing the most reliable TSS mapping [23]. In these applications, location and sequence quality share approximately equal importance—an optimally scoring gRNA in the wrong location will prove ineffective, while the limited target window often prevents selective use of only the highest-scoring sequences [23].

Specialized Applications: Imaging and Beyond

Beyond editing and regulation, gRNAs enable specialized CRISPR applications including chromosomal imaging in live cells. Multicolor CRISPR imaging systems employ orthogonal Cas9 orthologs from Streptococcus pyogenes, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus thermophilus, each fused to distinct fluorescent proteins and programmed with cognate gRNAs to visualize multiple genomic loci simultaneously [24]. These systems permit assessment of spatial nuclear organization, chromosome territories, and dynamic genomic interactions in living cells [24]. Similarly, engineered CRISPR-Tag systems incorporating approximately 600-bp synthetic sequences into viral genomes enable real-time tracking of herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) replication through dCas9-fluorescent protein labeling, revealing replication compartment dynamics and virus-host interactions [25].

Diagram 2: gRNA Design Workflow. Application-specific design pathway from goal definition to validation.

Advanced Design Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Predicting On-Target Activity and Minimizing Off-Target Effects

Computational prediction of gRNA efficacy represents a critical step in experimental design, with modern algorithms incorporating multiple sequence-based features to nominate gRNAs with high on-target activity. The widely adopted "Doench rules"—developed through analysis of thousands of gRNAs in genome-wide libraries—provide robust scoring metrics for on-target activity prediction [3] [23]. These rules have been implemented in various bioinformatics tools to guide researcher selection. Off-target effects remain a significant concern in CRISPR applications, with potential mismatches between gRNA and target DNA leading to unintended editing at genomic sites with sequence similarity [3] [11]. While whole-genome sequencing of CRISPR-modified cells has revealed that off-target mutations occur at low frequency in many experimental contexts, prudent design strategies incorporate specificity screening using tools like Cas-OFFinder and Off-Spotter to identify and avoid gRNAs with high off-target potential [23] [11].

Multiplexing and Experimental Validation

A key strategy for strengthening functional genomics conclusions involves implementing multiple gRNAs targeting the same gene, which controls for both off-target effects and variable editing efficiencies between individual gRNAs [3] [23]. In knockout experiments, multiplexing several gRNAs against different regions of the same gene dramatically increases the probability of complete gene disruption and enables phenotypic validation across independent targeting events [3]. For all CRISPR applications, validation remains essential—Sanger sequencing or next-generation amplicon sequencing confirms intended edits, while functional assays verify expected phenotypic outcomes [26] [27]. In HDR experiments, the gold standard requires not only introducing the desired edit but also reverting it to wild-type through a second round of editing to confirm phenotype linkage [23].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The CRISPR field continues to evolve rapidly, with artificial intelligence now enabling the design of novel Cas proteins with optimized properties. Recent advances demonstrate that large language models trained on diverse CRISPR sequences can generate functional Cas9-like effectors with comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to natural counterparts, despite being hundreds of mutations distant in sequence space [7]. One exemplar, OpenCRISPR-1, shows compatibility with base editing while maintaining high efficiency [7]. Base editing and prime editing technologies represent additional advancements with distinct gRNA design constraints—base editors require targets within a narrow 5-10 nucleotide window relative to the PAM, while prime editing maintains PAM proximity requirements but offers broader editing capabilities without double-strand breaks [23]. These technologies further expand the CRISPR toolkit while introducing new design considerations for researchers.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, Cas12 variants, OpenCRISPR-1 | DNA recognition and cleavage; base editing | Choice determines PAM requirements and editing window |

| gRNA Expression Formats | Plasmid vectors, synthetic sgRNA, IVT sgRNA | Delivery of guide RNA component | Synthetic sgRNA offers highest efficiency and lowest off-target effects [11] |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs (<200 nt), dsDNA with homology arms | HDR donor template for precise edits | Include silent PAM-disrupting mutations to prevent re-cleavage [22] |

| Design Tools | Synthego Design Tool, Benchling, CHOPCHOP | Computational gRNA design and optimization | Incorporate on-target and off-target scoring algorithms [3] [11] |

| Validation Reagents | Sanger sequencing primers, NGS amplicon panels | Confirmation of intended edits | Essential for verifying editing efficiency and specificity |

The guide RNA serves as the programmable core of the CRISPR system, with its design requirements fundamentally shaped by the specific application. While gene knockout prioritizes gRNAs with high predicted on-target activity within protein-coding regions, HDR experiments demand location-based selection near the intended edit site. CRISPRa/i applications require precise positioning relative to transcription start sites, while emerging technologies like base editing and chromosomal imaging introduce additional specialized constraints. By understanding these application-specific design principles and leveraging continuously improving computational tools and AI-generated editors, researchers can maximize CRISPR efficacy across diverse experimental contexts, from basic research to therapeutic development.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Designing gRNAs for Your Experimental Goals

In CRISPR research, the guide RNA (gRNA) serves as the precision targeting system that directs Cas proteins to specific genomic locations. While the fundamental components remain consistent—a 20-nucleotide spacer sequence and a scaffold structure—the optimal design of a gRNA varies dramatically depending on the experimental goal. Knockout (KO), knock-in (KI) via homology-directed repair (HDR), CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) each present unique constraints and priorities that fundamentally shape gRNA design strategy. This technical guide examines how researchers must adapt their gRNA design principles to align with these distinct applications, providing a structured framework for selecting gRNAs that maximize experimental success across different genome engineering approaches.

Core gRNA Design Principles Across Applications

All CRISPR gRNAs share basic structural components: a customizable 20nt spacer sequence that determines genomic targeting through Watson-Crick base pairing, and a structural scaffold that binds to the Cas protein [13]. The target sequence must be unique within the genome and immediately precede a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which varies depending on the Cas nuclease used [13]. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [22].

Two fundamental considerations guide all gRNA design: on-target efficiency (predicting successful editing at the intended target) and off-target risk (minimizing unintended edits at similar genomic sites) [13]. Multiple scoring algorithms have been developed to quantify these parameters, including Rule Set 3, CRISPRscan, and Lindel for on-target efficiency, and cutting frequency determination (CFD) and MIT scoring for off-target assessment [13]. However, the relative importance of location versus sequence optimization shifts significantly across different CRISPR applications, requiring researchers to prioritize different design parameters based on their specific experimental goals.

Application-Specific gRNA Design Strategies

Gene Knockout (CRISPRko)

Mechanism and Goals: Knockout strategies utilize functional Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the target DNA, which are repaired via the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway [28]. This repair often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the coding sequence, leading to frameshifts and premature stop codons that abolish gene function [28].

gRNA Design Priorities:

- Target Location: Ideal gRNAs target exonic regions early in the coding sequence (between 5%-65% of the protein-coding region) to maximize likelihood of complete gene disruption [23]. This minimizes the chance that alternative start codons downstream of the edit could restore function, and ensures edits occur before critical functional domains [23].

- Sequence Optimization: With many potential target sites available, sequence optimization takes priority. gRNAs should be selected based on high predicted on-target efficiency scores using established algorithms [13] [23].

- Practical Considerations: For essential genes, where complete knockout may be cell-lethal, alternative approaches like CRISPRi may be preferable [29]. Always design multiple gRNAs targeting different regions of the gene to control for variable efficiency and confirm phenotypes are consistent across guides [23].

Gene Knock-in via HDR

Mechanism and Goals: Knock-in approaches introduce specific DNA sequences—such as point mutations, epitope tags, or fluorescent reporters—using a donor DNA template with homology to the target region [28]. This requires creation of a DSB by Cas9 followed by repair via the HDR pathway, which uses the provided donor as a template [28] [22].

gRNA Design Priorities:

- Target Location: The gRNA cut site must be immediately adjacent (within ~30 nucleotides) to the intended edit, as HDR efficiency decreases dramatically with increasing distance [23]. This location constraint severely limits gRNA options compared to knockout approaches.

- Sequence Optimization: With limited location options, sequence optimization becomes secondary. Researchers must work with whatever gRNAs are available near their target edit, even if they have suboptimal efficiency scores [23].

- Practical Considerations: Include silent mutations in the donor template's PAM site to prevent re-cutting after successful HDR [22]. HDR efficiency is typically low, requiring careful screening and possibly multiple rounds of single-cell cloning [23]. For large inserts (>200 nucleotides), use double-stranded DNA templates with homology arms of 800bp; for smaller edits, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) of 80-200 nucleotides are sufficient [22].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

Mechanism and Goals: CRISPRi utilizes catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains like KRAB to sterically block transcription or recruit chromatin modifiers that suppress gene expression [29] [30]. This results in reversible, tunable gene knockdown without permanent DNA alteration.

gRNA Design Priorities:

- Target Location: gRNAs should target a window approximately 100 nucleotides downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) to effectively block RNA polymerase progression [23]. Accurate TSS annotation is critical, with FANTOM database (which uses CAGE-seq data) recommended for precise mapping [23].

- Sequence Optimization: With a relatively narrow targeting window, fewer gRNA options are available, making both location and sequence considerations equally important [23].

- Practical Considerations: dCas9-KRAB fusions achieve more robust repression (60-80%) than dCas9 alone, especially in mammalian cells [29]. CRISPRi is particularly valuable for studying essential genes where complete knockout would be lethal [29].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa)

Mechanism and Goals: CRISPRa recruits transcriptional activators like VP64, p65, or SunTag systems to promoters via dCas9, leading to enhanced gene expression [29] [30]. This enables gain-of-function studies without permanent genomic integration.

gRNA Design Priorities:

- Target Location: gRNAs should target a window approximately 100 nucleotides upstream of the TSS for optimal recruitment of transcriptional machinery [23].

- Sequence Optimization: Similar to CRISPRi, the narrow targeting window means location constraints and sequence optimization are both important considerations [23].

- Practical Considerations: Multi-domain activator systems like SunTag or SAM significantly enhance activation potency compared to single domains [29]. Recent research indicates that gRNA folding kinetics—specifically the energy barrier to adopting the active structure—strongly influence CRISPRa efficacy, with folding barriers ≤10 kcal/mol predicting optimal function [31].

Table 1: Key Design Parameters Across CRISPR Applications

| Parameter | Knockout | Knock-in (HDR) | CRISPRi | CRISPRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Protein | Active Cas9 | Active Cas9 | dCas9-repressor | dCas9-activator |

| Repair Mechanism | NHEJ | HDR | N/A | N/A |

| Optimal Target Location | Early coding region (5-65%) | Within ~30 nt of edit | ~100 nt downstream of TSS | ~100 nt upstream of TSS |

| Sequence Optimization Priority | High | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Persistence of Effect | Permanent | Permanent | Transient | Transient |

| Key Constraints | Avoids N/C-termini | Limited by edit location | Requires precise TSS mapping | Requires precise TSS mapping |

Advanced Design Considerations and Tools

gRNA Folding Considerations

Recent evidence indicates that gRNA secondary structure significantly impacts efficacy, particularly for CRISPRa applications. The folding barrier—the energy required for a gRNA to transition from its most stable structure to the active conformation—strongly correlates with CRISPRa performance (rS = 0.8) [31]. gRNAs with folding barriers ≤10 kcal/mol consistently show high activity, while those with higher barriers frequently underperform. This kinetic parameter outperforms traditional thermodynamic stability measures in predicting gRNA efficacy for transcriptional modulation [31].

Bioinformatics Tools for gRNA Design

Multiple web-based tools incorporate the design principles discussed above:

- CRISPick (Broad Institute): Implements Rule Set 3 for on-target scoring and CFD for off-target assessment [13].

- CHOPCHOP: Supports multiple Cas variants and provides visual off-target representations [13].

- CRISPOR: Offers detailed off-target analysis with position-specific mismatch scoring [13].

- GenScript gRNA Design Tool: Utilizes Rule Set 3 and CFD scoring with intuitive transcript visualization [13].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | SpCas9, SaCas9, AsCas12a | Engineered nucleases with different PAM specificities and sizes [13] [30] |

| CRISPRa/i Effectors | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR | Transcriptional repressors/activators for gene regulation [29] [30] |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Enable efficient cellular delivery of CRISPR components [32] |

| Donor Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA with homology arms | Provide repair templates for HDR-mediated knock-in [22] |

| gRNA Production | Synthetic gRNA, U6-driven expression plasmids | Options for transient or stable gRNA expression [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating gRNA Efficacy: A Multi-Guide Approach

Regardless of application, validating gRNA function requires a systematic approach:

- Design Multiple gRNAs: For any gene target, design 3-5 gRNAs targeting different positions to control for variable efficiency [23].

- Empirical Testing: Transfert constructs into relevant cell lines and assess outcomes:

- For knockout: Measure indel frequency via T7E1 assay or sequencing 72-96 hours post-transfection [28].

- For CRISPRa/i: Quantify mRNA expression changes via qRT-PCR 48-72 hours post-transfection [29].

- For knock-in: Use a combination of selection markers and PCR screening to identify successful events [22].

- Confirm Phenotype Consistency: Require that multiple gRNAs against the same target produce concordant phenotypes before attributing effects to on-target activity [23] [33].

Addressing Off-Target Effects

While computational prediction of off-target sites has improved, empirical validation remains essential:

- For knockout studies, sequence top predicted off-target sites (especially those with ≤3 mismatches) in final clones [13] [33].

- For CRISPRa/i, demonstrate that multiple gRNAs against the same gene produce similar phenotypic effects [29].

- Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) to reduce off-target editing in therapeutic applications [22].

gRNA design is not a one-size-fits-all process but requires careful consideration of experimental goals and application-specific constraints. Researchers must prioritize different elements of gRNA design based on whether they seek permanent gene disruption (knockout), precise sequence insertion (knock-in), or transient transcriptional modulation (CRISPRa/i). Location constraints dominate HDR-based knock-in approaches, while sequence optimization takes precedence in knockout strategies where target options are abundant. CRISPRa and CRISPRi occupy a middle ground, requiring both precise TSS-proximal targeting and attention to gRNA sequence quality. By aligning gRNA design strategies with experimental objectives and employing rigorous validation using multiple guides, researchers can maximize the success of their CRISPR experiments across diverse applications. As CRISPR technology continues evolving—with emerging approaches like base editing, prime editing, and AI-designed editors—gRNA design principles will likewise advance, offering ever more sophisticated tools for precision genome engineering [7] [32].

Diagram: gRNA Design Decision Workflow

The precision of CRISPR-based genome editing hinges on the critical interplay between genomic context and the availability of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences. This technical guide examines the foundational principles governing target site selection, focusing on how PAM requirements constrain targetable loci and how genomic features influence editing efficiency and specificity. Within the broader thesis of guide RNA design and function, we explore computational prediction tools, experimental validation methodologies, and advanced strategies for navigating target site limitations. With the FDA now recommending genome-wide off-target analysis for therapeutic development, the strategic integration of PAM selection with genomic context has become paramount for clinical applications. This whitepaper provides drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for optimizing target site selection to maximize editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects in therapeutic contexts.

The CRISPR-Cas system requires two fundamental components for successful genome editing: a guide RNA (gRNA) that confers sequence specificity through complementary base pairing, and a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) that serves as a recognition signal for the Cas nuclease [4]. The PAM is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) adjacent to the target DNA region that is essential for Cas nuclease activation [34]. This dual requirement creates the central challenge in target site selection: identifying genomic loci where the target sequence aligns with both gRNA complementarity and PAM availability.

From a structural perspective, the PAM enables Cas nuclease activation through direct protein-DNA interactions. When the Cas nuclease identifies a valid PAM sequence, it initiates local DNA unwinding, allowing the gRNA to probe for complementarity with the target DNA strand [34]. The stringency of PAM recognition varies among Cas nuclease variants, with implications for both target range and specificity. The seed sequence—the PAM-proximal 10–12 nucleotide region of the sgRNA—plays a crucial role in specific recognition and cleavage of target DNA [34].

The genomic context further complicates this relationship. Chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, DNA methylation status, and local DNA repair mechanisms all influence the ultimate editing outcome [35]. These biological variables interact with the biochemical constraints imposed by the PAM requirement, creating a multidimensional optimization problem for researchers designing CRISPR experiments.

Computational Approaches for gRNA Design and Specificity Analysis

Computational tools for gRNA design have evolved significantly to address the dual challenges of efficiency prediction and off-target assessment. These tools employ various algorithms to identify potential off-target sites by scanning the reference genome for sequences with similarity to the intended target, while accounting for factors such as PAM recognition rules, sequence homology, and thermodynamic properties [34].

GuideScan2: Advanced gRNA Design Platform

GuideScan2 represents a significant advancement in gRNA design technology, utilizing a novel search algorithm based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform for genome indexing combined with simulated reverse-prefix trie traversals for identifying gRNAs and their off-targets [36]. This approach enables memory-efficient (3.4 Gb for hg38, a 50× improvement over original GuideScan), parallelizable construction of high-specificity CRISPR gRNA databases.

The platform allows user-friendly design and analysis of individual gRNAs and gRNA libraries for targeting both coding and non-coding regions in custom genomes [36]. GuideScan2's specificity analysis has identified widespread confounding effects of low-specificity gRNAs in published CRISPR screens, demonstrating that gRNAs with particularly low specificity can produce strong negative cell fitness effects even for non-essential genes, likely through toxicity from numerous non-specific cuts [36].

Table 1: Comparison of gRNA Design Tools and Their Features

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Specificity Assessment | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuideScan2 | gRNA design and specificity analysis | Genome-wide off-target enumeration | Memory-efficient Burrows-Wheeler transform; designed libraries reduce off-target effects |

| CRISPR-GPT | AI-assisted experimental design | Predicts off-target edits and their likelihood | Leverages 11 years of published data; explains recommendations |

| Cas-OFFinder | Off-target prediction | Identifies potential off-target sites | Based on sequence similarity and PAM rules |

| CRISPOR | gRNA design and efficiency prediction | Off-target identification and scoring | Integrates multiple scoring algorithms; user-friendly interface |

AI-Powered Design with CRISPR-GPT

Stanford researchers have developed CRISPR-GPT, an AI tool that acts as a gene-editing "copilot" to help researchers generate designs, analyze data, and troubleshoot design flaws [37]. The model was trained on 11 years' worth of expert discussions and scientific papers, creating an AI that "thinks" like a scientist [37]. CRISPR-GPT can predict off-target edits and their likelihood of causing damage, allowing experts to choose optimal gRNAs [37].

In practice, researchers initiate a conversation with the AI through a text chat box, providing experimental goals, context, and relevant gene sequences. CRISPR-GPT then creates a plan that suggests experimental approaches and identifies problems that have occurred in similar experiments [37]. The tool offers three modes: beginner mode (provides answers with explanations), expert mode (functions as a collaborative partner without extra context), and Q&A mode (for specific questions) [37].

PAM Sequences and Nuclease Variants

The PAM requirement represents the primary constraint on targetable genomic loci, with different Cas nucleases recognizing distinct PAM sequences. Understanding these variations enables researchers to select the most appropriate nuclease for their specific target of interest.

PAM Diversity Across Cas Nucleases

The most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence, where "N" can be any nucleotide base [4]. This relatively simple PAM occurs approximately every 8-12 base pairs in the human genome, providing substantial targeting flexibility. However, when targeting specific genomic regions without an NGG PAM, alternative nucleases must be considered.

Table 2: PAM Sequences of Commonly Used CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| LbCpf1 (Cas12a) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AsCpf1 (Cas12a) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV |

| BhCas12b v4 | Bacillus hisashii | ATTN, TTTN and GTTN |

| Cas3 | Various prokaryotes | No PAM sequence requirement |