Systematic Review vs Narrative Review in Materials Science: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical distinctions between systematic and narrative literature reviews within materials science.

Systematic Review vs Narrative Review in Materials Science: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical distinctions between systematic and narrative literature reviews within materials science. It explores the foundational principles of both review types, detailing their specific methodological approaches and application areas, from exploring novel nanomaterials to assessing the efficacy of clinical materials. The content offers practical solutions for common challenges, including resource constraints and avoiding AI-generated bias, and provides a direct comparative analysis to validate review findings. By synthesizing evidence-based guidance with field-specific examples, this article empowers scientists to select the optimal review methodology to robustly support research, inform policy, and accelerate innovation in biomedicine and materials development.

Systematic and Narrative Reviews: Defining Your Research Path in Materials Science

What is a Narrative Review? Understanding its Broad Exploratory Role

In the realm of scientific research, particularly within fields as dynamic as materials science and drug development, the ability to synthesize existing knowledge is as crucial as generating new data. Among the various synthesis methods, the narrative review holds a distinct and vital position. Unlike its more structured counterpart, the systematic review, a narrative review provides a flexible, interpretive synthesis of literature on a broad topic, allowing authors to describe and critically evaluate an entire body of knowledge [1]. It is a form of knowledge synthesis grounded in interpretivist paradigms, emphasizing that reality is subjective and dynamic, and it harnesses the unique perspectives of the review team to shape the analysis [1]. For researchers in materials science navigating a complex landscape of new polymers, composites, and characterization techniques, or for drug development professionals assessing the theoretical foundations of a novel therapeutic approach, the narrative review offers a practical tool to map the territory, identify trends and gaps, and provide a comprehensive, readable summary. This article frames the narrative review within the broader context of evidence synthesis, clarifying its exploratory role and defining its place alongside the more prescriptive systematic review.

Defining Narrative and Systematic Reviews

At its core, a narrative review is a type of literature review that summarizes, interprets, and critiques a body of literature on a broad topic without being confined to the rigid protocols mandatory for systematic reviews [2]. It is also referred to as a traditional or literature review and is characterized by its flexible and exploratory nature [3] [4]. The primary aim is to provide a broad, overall summary of the existing research, often organized thematically or chronologically, to deepen the understanding of a specific research area [3] [5].

In direct contrast, a systematic review is designed to answer a specific, focused research question by systematically searching, appraising, and synthesizing all available evidence using explicit, pre-specified methods [3] [6]. Its methodology is robust, reproducible, and transparent, aiming to minimize bias at every stage [3]. Systematic reviews are considered the gold standard in evidence-based medicine for answering focused questions on, for example, the efficacy of a specific intervention [3] [7].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these two review types, highlighting their distinct objectives, methodologies, and outputs.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Narrative and Systematic Reviews

| Feature | Narrative Review | Systematic Review |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | Broad in scope, often exploratory [3] [1] | Narrow, focused, and specific [3] |

| Search Strategy | May not be comprehensive; often iterative; not necessarily reproducible [6] [5] | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching; documented and reproducible [8] [6] |

| Study Selection | No strict inclusion/exclusion criteria; selection can be subjective [3] [1] | Pre-specified, strict inclusion/exclusion criteria applied systematically [3] [7] |

| Quality Assessment | No formal quality assessment typically required [8] [5] | Formal critical appraisal of included studies is mandatory [8] [7] |

| Synthesis | Typically narrative, summarizing and interpreting literature [8] [6] | Often involves quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) or structured qualitative synthesis [3] [7] |

| Primary Application | Providing context, exploring debates, identifying gaps, speculating on future research [3] [1] | Providing definitive evidence to guide clinical decisions and inform policy [3] [7] |

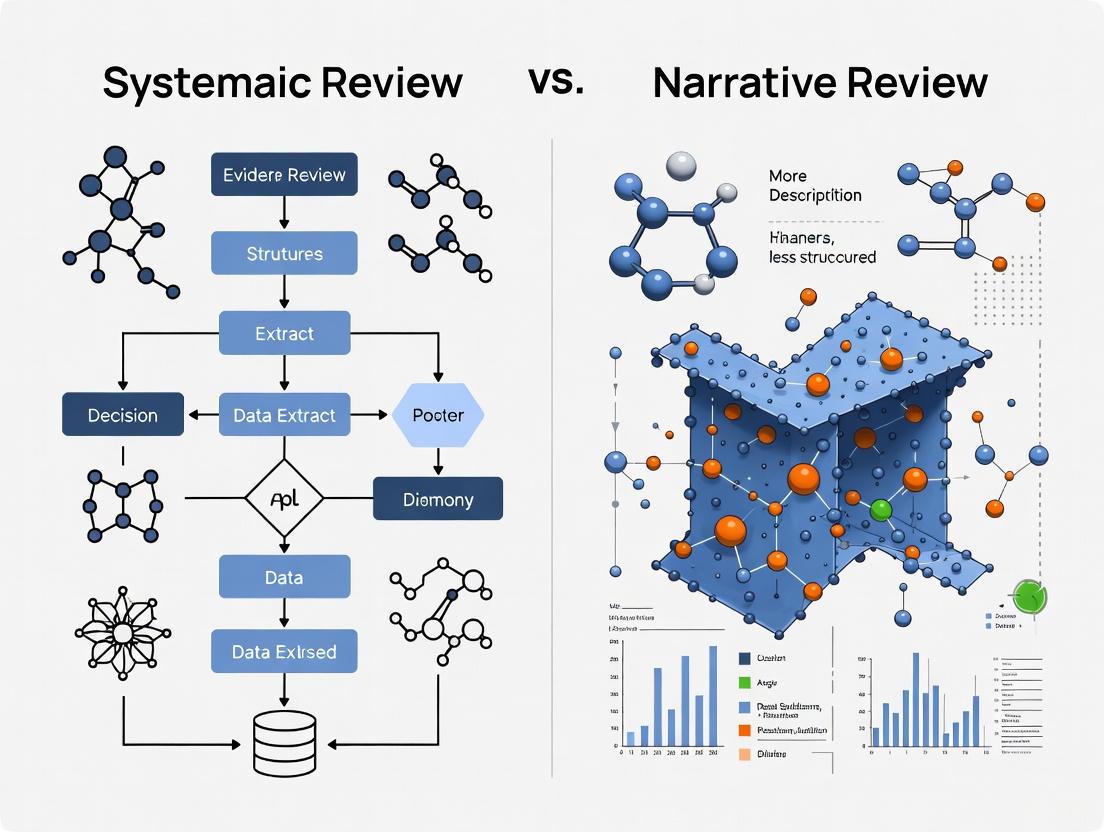

The following workflow diagram illustrates the divergent paths taken by these two review methodologies, from initial conception through to final output.

The Methodology of a Narrative Review

While a narrative review does not follow a rigid, standardized protocol like a systematic review, conducting a high-quality narrative review requires a deliberate and rigorous approach. The process is often iterative, involving multiple cycles of searching, analysis, and interpretation [1]. The following section outlines a recommended methodology, providing a practical guide for researchers.

Step-by-Step Guide

- Define Your Topic and Scope: The first step is to narrow your focus and craft a clear, purposeful research question [2]. Unlike a systematic review question, this question should be broad enough to allow for exploration but specific enough to provide direction. For example, instead of "What are the properties of hydrogels?", a more focused narrative review question might be, "How have smart hydrogel scaffolds advanced tissue engineering in the last decade?".

- Search the Literature: A narrative review does not require an exhaustive search of all possible databases, but the search must be strategic and well-documented to ensure the inclusion of pivotal and relevant literature [1] [2]. This involves:

- Selecting Databases: Use relevant academic databases (e.g., PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and subject-specific databases like those for materials science or chemistry) [7] [2].

- Using Grey Literature: Include conference proceedings, dissertations, and reports to access cutting-edge developments and avoid publication bias [2].

- Employing Citation Tracking: Use backward tracking (reviewing reference lists of key papers) and forward tracking (finding newer papers that cite key works) to build a robust literature set [2].

- Select and Analyze Key Studies: The goal is to prioritize high-impact, relevant studies that directly contribute to the research question [2]. This involves evaluating the credibility of sources (prioritizing peer-reviewed journals), assessing methodological soundness, and identifying patterns, consensus, and contradictions within the literature [2]. During this phase, it is crucial to take strategic notes, summarizing key points, recording strengths and weaknesses of studies, and highlighting gaps.

- Structure and Write the Review: A strong structure is key to a readable and influential narrative review. A standard outline includes:

- Introduction: Define the topic, state its importance, and present the research question and objectives [2].

- Background: Provide necessary context, including historical development and definitions of key terms [2].

- Thematic Sections: Organize the body of the review by themes, debates, or methodologies, not just as a series of study summaries. Use subheadings to guide the reader and compare and contrast different studies [2].

- Discussion and Conclusion: Synthesize the major insights, address inconsistencies, propose directions for future research, and provide a clear summary of the key takeaways [2].

Ensuring Rigor and Quality

Despite its flexibility, a narrative review must be conducted with rigor. The Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) is a validated tool developed to help critique and improve the quality of narrative reviews [9]. Its six items, rated from 0 (low standard) to 2 (high standard), provide a framework for assessing key areas of quality:

Table 2: The SANRA Scale for Quality Assessment of Narrative Reviews

| SANRA Item | Description | High Standard (Score of 2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Importance of Review | Explains the importance and rationale for the review | Clearly states why the review is needed and important for the field [9]. |

| 2. Aims of the Review | Clearly states the aims or objectives | Explicitly lists the goals of the review article [9]. |

| 3. Literature Search | Describes the methods used for the literature search | Provides a description of search sources and key terms, making the process transparent [9]. |

| 4. Referencing | Provides appropriate and current references | Cites key and up-to-date works; references are accurate and relevant [9]. |

| 5. Scientific Reasoning | Addresses the level of evidence of the cited literature | Acknowledges and discusses the quality of the evidence presented (e.g., RCTs vs. preclinical studies) [9]. |

| 6. Relevant Data Presentation | Presents appropriate endpoint data | Includes relevant and concrete data to support statements, not just general summaries [9]. |

Furthermore, authors should practice reflexivity—that is, clearly specify any factors that may have shaped their interpretations and analysis, such as their own expertise or theoretical preferences [1]. Finally, authors should justify how they determined that their analysis was sufficient and acknowledge the boundaries and limitations of their review, including potential selection bias [1] [2].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Narrative Reviews

Successfully navigating and synthesifying a broad body of literature requires a specific set of conceptual and practical tools. This toolkit is essential for ensuring the review is comprehensive, well-organized, and insightful.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Conducting a Narrative Review

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Narrative Review |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Framework | Thematic Analysis | To identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) within the literature, moving beyond simple summary to interpretation [8]. |

| Chronological Mapping | To track the development of a concept, material, or technique over time, highlighting pivotal advances [8] [6]. | |

| Gap Analysis | To identify under-researched areas or contradictions in the existing literature, suggesting future research directions [5]. | |

| Literature Search & Management | Academic Databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, subject-specific databases) | To locate peer-reviewed, high-impact literature relevant to the field (e.g., materials science, pharmacology) [7] [2]. |

| Citation Tracking Software (e.g., Litmaps, Research Rabbit) | To visually map relationships between articles and identify seminal and emerging papers efficiently [2]. | |

| Reference Management Software (e.g., EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) | To store, organize, and annotate retrieved literature and generate citations and bibliographies [7]. | |

| Quality Assurance | SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) | A checklist to ensure methodological rigor, transparency, and overall quality during writing and revision [9]. |

| Peer Debriefing | To get feedback from colleagues or supervisors on the review's structure, clarity, and argument, reducing interpretive bias [2]. |

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between the different stages of the narrative review process and the primary tools used at each stage to ensure a successful outcome.

Within the evidence synthesis ecosystem, the narrative review and systematic review serve complementary rather than competing roles. The choice between them is not a matter of hierarchy but is wholly dependent on the research question at hand [8]. Systematic reviews are unparalleled for answering focused questions on specific interventions, providing the highest level of evidence for clinical and policy decisions [3] [7]. In contrast, narrative reviews are ideally suited for exploring broad, complex, or evolving topics where a flexible, interpretive synthesis is more valuable than a rigid, quantitative summary [1] [2].

For materials scientists and drug development professionals, this distinction is critical. A narrative review is the superior tool for tracking the historical development of a class of biomaterials, for critiquing the application of various characterization techniques across a field, or for building a new theoretical framework from disparate interdisciplinary studies. Its ability to provide a wide-ranging, critical, and readable overview makes it an indispensable mechanism for advancing understanding, stimulating innovation, and guiding future research trajectories in fast-paced scientific domains. When conducted with the rigor and transparency outlined in this article, a narrative review is not merely a summary but a significant scholarly contribution in its own right.

What is a Systematic Review? The Gold Standard for Evidence-Based Answers

A systematic review is a rigorous research methodology that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise all relevant studies on a specific research question, and to collect and analyze data from the included studies [3]. It represents the pinnacle of the evidence hierarchy, designed to minimize bias and provide reliable findings that can inform clinical decision-making, policy development, and guide future research [10]. This in-depth guide details the core principles, protocols, and applications of systematic reviews, contextualizing their value against traditional narrative reviews, particularly for researchers in fields like materials science and drug development.

In an era of rapidly expanding scientific literature, the ability to synthesize high-quality research findings is paramount for evidence-based practice. Systematic reviews have emerged as an essential component of secondary research to meet this need [10].

Unlike a narrative review—which provides a broad, often thematic summary of the literature without a strict protocol—a systematic review is characterized by its robust, reproducible, and transparent methodology [3]. The primary distinction lies in their objectives and application; while narrative reviews are excellent for exploring historical developments and broad concepts, systematic reviews are structured to answer a specific, focused research question with a pre-specified plan that leaves no room for ad hoc decisions [3] [5]. This methodological rigor is what establishes systematic reviews as the gold standard for evidence-based answers, especially in applied and clinical fields [3].

Core Principles: Systematic vs. Narrative Review

The choice between a systematic and narrative review is fundamental and should be guided by the research aim. The table below summarizes the key distinctions.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Systematic and Narrative Reviews

| Aspect | Systematic Review | Narrative (Traditional) Review |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Answers a specific, focused research question using qualitative/quantitative methods [3]. | Explores one or more questions with a broader scope; tracks the development of a concept or field [3]. |

| Research Question | Well-defined, often using frameworks like PICO [10]. | Can be broad and flexible, not necessarily predefined [5]. |

| Protocol | Requires a pre-specified, explicit, and transparent protocol [3]. | No strict protocol; design depends on author preference and journal conventions [3]. |

| Search Strategy | Comprehensive, systematic search across multiple databases to identify all relevant studies [10]. | May or may not include comprehensive searching; often not explicitly stated [8]. |

| Study Selection | Uses strict, pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria to minimize selection bias [3]. | Study selection is often not systematic and can be subjective [5]. |

| Quality Assessment | Critical appraisal of included studies is a mandatory step using standardized tools [10]. | No formal quality assessment; evaluation may be based on contribution to the topic [8]. |

| Synthesis | Data synthesis can be qualitative, quantitative (meta-analysis), or both [10]. | Typically narrative, can be conceptual, thematic, or chronological [5]. |

| Output | Valid evidence to guide clinical decisions and inform policy [3]. | Deepens understanding, identifies gaps, and sets the context for new research [5]. |

| Limitations | Can be time and resource-intensive; rigid framework may limit exploratory analysis [3]. | Author's perspective can introduce bias; harder to replicate due to less transparency [5]. |

For materials scientists, this distinction is critical. A narrative review is invaluable for understanding the evolution of a material class (e.g., high-entropy alloys) and identifying overarching challenges. In contrast, a systematic review is the appropriate tool to definitively answer a specific question, such as, "In pre-clinical in vivo studies, does coating titanium-based orthopedic implants with hydroxyapatite (I) compared to uncoated titanium (C) improve bone-implant integration (O)?"

The Systematic Review Workflow: A Detailed Experimental Protocol

Conducting a systematic review is a multi-stage process that demands meticulous planning and execution. The following workflow, adapted from established guidelines, provides a detailed protocol [3] [10].

Diagram: Systematic Review Workflow. The process flows from defining the question to reporting, with key stages for screening, appraisal, and synthesis.

Formulating the Research Question

The process begins with a well-defined research question. A structured framework ensures the question is focused and actionable. The most commonly used framework is PICO, which stands for [10]:

- Population/Patient/Problem: The specific group, material, or condition being studied.

- Intervention or Exposure: The experimental therapy, material, or process being investigated.

- Comparator: The control group or standard against which the intervention is compared.

- Outcome: The measured result or endpoint of interest.

For non-intervention questions, alternative frameworks like CoCoPop (Condition, Context, Population) for prevalence questions or PICo (Population, Interest, Context) for qualitative reviews may be used [10].

Developing a Protocol

A mandatory step is developing a detailed research protocol. This pre-specified plan minimizes bias and ensures transparency and reproducibility. The protocol should define [3]:

- The research question and PICO/other framework elements.

- Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies.

- The detailed search strategy for each database.

- Plans for quality assessment (risk of bias) and data extraction.

- The planned method for data synthesis.

Registering the protocol on platforms like PROSPERO is considered best practice.

Comprehensive Literature Search

A systematic search aims to identify all published and unpublished studies relevant to the question. This involves [10]:

- Searching multiple bibliographic databases (e.g., PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central, Web of Science, Scopus, and field-specific databases like Compendex for engineering).

- Supplementing with searches of grey literature (e.g., clinical trial registries, conference proceedings, theses, and government reports) to mitigate publication bias.

- Using a search strategy crafted with controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) and keywords, often with the assistance of a research librarian.

Study Selection, Appraisal, and Data Extraction

This phase involves applying the protocol's criteria to the search results in a multi-stage process, often visualized using a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart [11].

Table 2: Key Stages in the Screening and Appraisal Process

| Stage | Process Description | Tools & Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| De-duplication | Removing duplicate records from multiple database searches. | Reference managers (EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) or specialized software (Covidence, Rayyan) [10]. |

| Screening (Title/Abstract) | Initial screening of records against inclusion/exclusion criteria. | Typically performed by two or more independent reviewers to reduce bias [10]. |

| Eligibility (Full-Text) | Retrieving and assessing the full text of potentially relevant studies. | Reasons for excluding studies at this stage are recorded and reported [11]. |

| Critical Appraisal | Assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias of included studies. | Standardized tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for RCTs, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies) [10]. |

| Data Extraction | Systematically extracting relevant data from included studies. | Using pre-piloted, standardized data extraction forms to ensure consistency [10]. |

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The extracted data is then synthesized. This can be performed qualitatively, where findings are summarized narratively and often tabulated, or quantitatively via meta-analysis [10].

A meta-analysis is a statistical technique that combines the numerical results of multiple independent studies that are sufficiently similar. It uses specialized software (e.g., R, RevMan) to compute pooled effect estimates, confidence intervals, and assess heterogeneity (the degree of variability between studies) using statistics like I² [10]. Results are typically displayed visually using forest plots. When a meta-analysis is not appropriate, other synthesis methods, such as qualitative synthesis or Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM), are employed [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for a Systematic Review

In the context of a systematic review, "research reagents" refer to the essential digital tools, databases, and resources required to conduct the review efficiently and accurately.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systematic Reviews

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Covidence | Review Management | A web-based platform that streamlines title/abstract screening, full-text review, risk-of-bias assessment, and data extraction, enabling collaboration among reviewers [10]. |

| Rayyan | Review Management | A tool that assists in the screening phase by allowing collaborative work and suggesting inclusion/exclusion criteria [10]. |

| PubMed / MEDLINE | Bibliographic Database | A free primary life sciences and biomedical database maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, essential for any biomedical review [10]. |

| Embase | Bibliographic Database | A comprehensive biomedical and pharmacological database, known for its extensive coverage of drug and conference literature [10]. |

| Cochrane Library | Bibliographic Database | A collection of databases that includes published systematic reviews and trial registries, fundamental for evidence-based healthcare [10]. |

| EndNote / Zotero | Reference Manager | Software for collecting search results, removing duplicate records, and managing citations throughout the review process [10]. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) | Quality Assessment | A standardized tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [10]. |

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) | Quality Assessment | A tool for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies, such as case-control and cohort studies [10]. |

| R / RevMan | Data Analysis | Statistical software (R) and the Cochrane's Review Manager (RevMan) used for performing meta-analysis and generating forest and funnel plots [10]. |

| PRISMA Statement | Reporting Guideline | An evidence-based minimum set of items (including a flowchart) for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses, ensuring transparency and completeness [11]. |

For researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development, mastering the systematic review methodology is no longer optional but essential. It provides a powerful mechanism to consolidate pre-clinical and clinical data, assess the true strength of evidence for a new material or drug delivery system, and make informed decisions for future research trajectories and regulatory submissions. By rigorously adhering to its structured protocol, scientists can produce the most reliable and unbiased syntheses of existing evidence, truly earning the designation as the gold standard for evidence-based answers.

In the rigorous field of materials science research, particularly for drug development professionals and scientists, the selection of an appropriate literature review methodology is a critical first step that shapes the entire research trajectory. The core objective of a research project—whether a broad exploration of a nascent field or a focused clinical question about a specific intervention—dictates whether a narrative review or a systematic review is the more appropriate tool [3]. These two methodologies represent fundamentally different approaches to evidence synthesis. Narrative reviews offer a flexible, conceptual overview, ideal for mapping the theoretical landscape and identifying emerging trends. In contrast, systematic reviews provide a structured, protocol-driven process designed to minimize bias and deliver reliable, reproducible answers to precisely defined questions [12] [13]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these methodologies, enabling researchers to make an informed choice aligned with their core research objectives.

Defining the Core Objectives and Methodologies

Narrative Reviews: Objective of Broad Exploration

A narrative literature review, often termed a traditional or qualitative review, aims to provide a comprehensive summary and interpretation of the existing literature on a topic [5] [13]. Its primary strength lies in its flexibility, allowing the author to explore a wide range of studies and synthesize them conceptually, thematically, or chronologically. This methodology is not designed to be exhaustive but rather to provide a contextual backdrop, identify overarching trends and theories, and pinpoint gaps in the current knowledge base [3] [14]. Consequently, narrative reviews are exceptionally valuable for exploring new or interdisciplinary topics, formulating new hypotheses, and providing the foundational understanding necessary for more focused research [5].

Systematic Reviews: Objective of Answering Focused Clinical Questions

A systematic review is a structured and comprehensive research methodology designed to answer a specific, focused research question by identifying, appraising, and synthesizing all relevant empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria [3] [15]. Its core objective is to provide a definitive summary of the evidence, minimizing bias through a transparent and reproducible process. This rigor makes systematic reviews the gold standard for informing evidence-based practice, clinical guideline development, and policy decisions [3] [12]. They often employ quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) to provide a statistical summary of results, offering the most valid evidence on the efficacy of interventions or the accuracy of diagnostic tools [8] [15].

Table 1: Core Objectives and Methodological Characteristics

| Feature | Narrative Review | Systematic Review |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Broad exploration; contextual understanding; hypothesis generation [3] [5] | Answering a focused question; informing practice and policy with robust evidence [3] [15] |

| Research Question | Can be broad or consist of multiple questions [3] | Narrow, specific, and defined using frameworks like PICO [3] |

| Protocol | No pre-specified protocol; methodology can be adaptive [3] | Mandatory pre-published protocol with pre-defined plans [3] [12] |

| Search Strategy | May not be comprehensive; often not fully reported; can use diverse sources [5] [14] | Comprehensive, systematic search across multiple databases; fully reported for reproducibility [12] [13] |

| Study Selection | No formal inclusion/exclusion criteria; potentially susceptible to selection bias [3] [12] | Strict, pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria applied systematically to minimize bias [3] |

| Quality Appraisal | Typically no formal critical appraisal of individual studies [8] | Rigorous critical appraisal of included studies (e.g., risk of bias assessment) [8] [13] |

| Evidence Synthesis | Qualitative, narrative summary; often thematic or conceptual [8] | Structured synthesis (narrative, tabular); may include quantitative meta-analysis [3] [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Conducting Reviews

Protocol for a Narrative Review

While narrative reviews are more flexible, a methodical approach enhances their credibility and usefulness.

- Define the Topic and Scope: Establish a clear research problem or topic. Determine the review's purpose—for example, to explore historical development, discuss a controversy, or summarize a complex field [14].

- Develop a Search Strategy: Identify key concepts and relevant keywords. Select appropriate databases and resources (e.g., PubMed, Scopus, specialized materials science databases). The search may be iterative, expanding as new relevant terms and sources are identified [5].

- Literature Search and Selection: Execute the search. Selection of literature is often based on the researcher's expertise and judgment, aiming to capture seminal works and representative perspectives rather than an exhaustive list [13].

- Critical Analysis and Data Extraction: Read selected papers critically. Extract information thematically, such as key findings, methodologies, strengths, weaknesses, and conceptual contributions. This step involves interpreting and integrating ideas across studies [8] [5].

- Structuring and Writing the Review: Organize the synthesized information logically. Common structures include chronological (tracking development over time), thematic (grouping by concept or theory), or methodological (grouping by research approach) [5]. The writing should tell a coherent "story" about the state of knowledge on the topic.

Protocol for a Systematic Review

Systematic reviews follow a strict, pre-defined protocol to ensure rigor and transparency. Key guidelines include PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and the Cochrane Handbook [3] [15].

- Formulate a Precise Research Question: Define the question using the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) or its variants to ensure specificity [3].

- Develop and Register a Protocol: Create a detailed protocol that outlines the rationale, objectives, and specific methods for the review. This includes search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction items, and synthesis plans. Register the protocol in a platform like PROSPERO [12].

- Systematic Search for Evidence: Design a comprehensive search strategy with a librarian or information specialist. Search multiple electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central), clinical trial registries, and grey literature. The search strategy should be documented in full [12] [15].

- Study Selection Based on Criteria: Screen records (titles/abstracts, then full-text) against the pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. This process is typically performed by two reviewers independently to minimize error and bias, with disagreements resolved through consensus or a third reviewer [3].

- Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal: Extract relevant data from included studies using a standardized data extraction form. Simultaneously, critically appraise the methodological quality or risk of bias of each study using validated tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials) [3] [12].

- Synthesis of Extracted Evidence: Synthesize the findings from the included studies. This can be a narrative synthesis with tabular accompaniment or a quantitative meta-analysis if the studies are sufficiently homogeneous. Meta-analysis statistically combines results to produce an overall effect size [8] [15].

- Report and Disseminate Findings: Write the final review following PRISMA reporting guidelines, transparently presenting the methods, results, and conclusions, including limitations and implications for practice and research [3].

Visualization of Review Workflows and Logical Relationships

Diagram 1: Review methodology selection and workflow.

Conducting a high-quality review requires a suite of conceptual and practical "research reagents." The following table details essential tools and resources for researchers undertaking either a narrative or systematic review.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Literature Reviews

| Tool/Resource | Function | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| PICO Framework | Structures a research question into key components: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome. Ensures focus and specificity [3]. | Systematic Review |

| PRISMA Guidelines | An evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Ensures transparency and completeness of reporting [3]. | Systematic Review |

| Cochrane Handbook | The official guide to the conduct of systematic reviews of interventions in healthcare. Provides detailed methodology [15]. | Systematic Review |

| Bibliographic Database | Platforms (e.g., MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Scopus, specialized materials science DBs) for identifying published scientific literature. Used in all reviews, but search comprehensiveness varies [5] [15]. | Both |

| Reference Management SW | Software (e.g., EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) to store, organize, and cite references. Essential for managing the volume of literature in any review [15]. | Both |

| Critical Appraisal Tool | Standardized checklists (e.g., Cochrane RoB 2, ROBINS-I, CASP) to evaluate the methodological quality and risk of bias in primary studies [12] [13]. | Systematic Review |

| Data Extraction Form | A standardized, pre-piloted form (often in Excel or specialized software) to consistently capture key data from each included study [3]. | Systematic Review |

| Thematic Analysis Framework | A qualitative method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. Provides structure for narrative synthesis [8] [5]. | Narrative Review |

| Systematic Review Software | Specialized platforms (e.g., DistillerSR, Rayyan, Covidence) to manage the screening, selection, and data extraction phases of a systematic review [3]. | Systematic Review |

The choice between a narrative and a systematic review is not a matter of hierarchy but of strategic alignment with the core research objective. For materials scientists and drug development professionals, this decision is paramount. When the goal is to explore a broad, complex field, generate novel hypotheses, or understand the theoretical landscape, a narrative review provides the necessary flexibility and conceptual depth. Conversely, when a precise, clinically relevant question demands an unbiased, definitive answer to inform a critical decision or practice guideline, a systematic review is the unequivocal methodology of choice due to its rigor, transparency, and reliability [3] [12]. By understanding the distinct purposes, methodologies, and tools associated with each approach, researchers can effectively select and execute the review type that will most robustly advance their scientific and clinical inquiries.

In materials science research, the synthesis and evaluation of knowledge are foundational to progress. Two predominant methodological frameworks govern this process: the rigorous, pre-specified protocols of systematic reviews and the flexible narration of traditional narrative reviews. Systematic reviews aim to minimize bias via a predefined, structured protocol, offering a comprehensive and reproducible summary of evidence relevant to a focused research question [3]. Conversely, narrative reviews provide a broader, more descriptive overview of a topic, often organized thematically or chronologically, and are valued for contextualizing a field, identifying trends, and discussing theoretical perspectives in a more flexible manner [5]. This guide delineates the typical workflows, experimental protocols, and practical applications of each approach, providing researchers with the tools to select and execute the appropriate methodology for their investigative goals.

Core Methodological Comparison

The fundamental differences between these review types are rooted in their objectives, methodologies, and final applications. The table below provides a structured comparison of their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between narrative and systematic reviews

| Aspect | Narrative Review | Systematic Review |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | To provide a broad overview, explore existing debates, and identify gaps or new research directions [5]. | To answer a specific, well-defined research question by analyzing all available evidence using explicit, pre-specified methods [3]. |

| Research Question | Can address one or more questions; often broad in scope [3]. | Focused, typically formulated using frameworks like PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) [3]. |

| Protocol & Methodology | No strict, pre-specified protocol; methodology is flexible and depends on author choices and journal conventions [3] [5]. | Rigorous, explicit, and transparent pre-specified protocol with strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [3]. |

| Literature Search | Often less systematic; may use a range of databases and tools without full reporting of sources or search strategy [5]. | Comprehensive, broad search across multiple databases with a documented strategy to identify all eligible studies [3]. |

| Study Selection & Appraisal | No formal critical appraisal requirement; selection can be subjective, potentially introducing author bias [5]. | Mandatory critical appraisal of selected studies; study selection and data extraction are typically performed by multiple reviewers to reduce bias [3]. |

| Data Synthesis | Qualitative, narrative summary and synthesis of findings [5]. | Qualitative and/or quantitative synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis) of data extracted from primary studies [3]. |

| Key Applications | Tracking development of a field, demonstrating the need for new research, assessing research methods [5]. | Informing evidence-based guidelines, clinical decision-making, policy development, and regulatory submissions [3]. |

Workflow Visualization and Breakdown

The distinct methodologies of narrative and systematic reviews can be visualized as two separate workflows, each with defined stages and decision points, as shown in the diagram below.

Diagram: Comparative workflows for narrative and systematic reviews

Workflow A: Flexible Narration (Narrative Review)

The narrative review workflow is characterized by its iterative and non-linear nature, allowing for refinement and discovery throughout the process.

- Define Broad Research Scope: The process begins by establishing a wide-ranging area of interest, such as "recent advances in biodegradable polymers for drug delivery," without the constraints of a highly focused question [5].

- Conduct Exploratory Literature Search: The researcher performs searches using academic databases, often starting with a few key terms and expanding based on discovered references. The search strategy may evolve and is not necessarily documented in full [5].

- Identify Key Themes and Theories Subjectively: The reviewer immerses themselves in the literature, identifying prevailing concepts, debates, and trends through a qualitative and subjective analysis. This stage relies heavily on the reviewer's expertise and perspective [5].

- Write Descriptive Synthesis: Findings are organized thematically or chronologically to provide a narrative summary of the field. This synthesis explores different viewpoints and charts the evolution of ideas without a formal quantitative analysis [5].

- Identify Gaps and Suggest Future Research: The review concludes by highlighting areas where knowledge is lacking or conflicting, using this as a basis to propose directions for future scientific inquiry [5].

Workflow B: Rigorous, Pre-Specified Protocols (Systematic Review)

In stark contrast, the systematic review workflow is a linear, strictly planned process designed to minimize bias at every stage.

- Formulate Precise Research Question (PICO): The review is initiated by defining a narrow, focused question. The PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) is commonly used to structure this question, for example: "In metastatic breast cancer (P), do nanoparticle-based chemotherapeutics (I) compared to traditional solvent-based chemotherapeutics (C) improve progression-free survival (O)?" [3].

- Develop and Register Detailed Protocol: A comprehensive protocol is written a priori, specifying the study selection criteria, search strategy, data extraction methods, and approach to quality assessment and synthesis. This protocol is often registered in a platform like PROSPERO to prevent duplication and reduce reporting bias [3].

- Execute Comprehensive Systematic Search: A librarian or information specialist is often consulted to design a search strategy that spans multiple electronic databases (e.g., Scopus, MEDLINE, Web of Science) with precise, complex Boolean queries. The search is documented in full to ensure reproducibility [3].

- Screen Studies Against Pre-defined Criteria: The identified records are screened, first by title and abstract, then by full text, against the pre-specified eligibility criteria. This process is typically performed by two or more independent reviewers to minimize error and bias, with a method for resolving disagreements [3].

- Critically Appraise Studies and Extract Data: The methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies are assessed using standardized tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, QUADAS-2). Data relevant to the research question and outcomes are extracted from each study, again often in duplicate [3].

- Synthesize Data (Qualitative/Quantitative): The extracted data are synthesized. This may be a qualitative summary (tabulating and describing findings) or a quantitative meta-analysis, which uses statistical methods to combine numerical results from multiple studies to produce a single summary estimate [3].

- Report Findings and Assess Certainty: The results are reported, including the strength of the evidence (e.g., using GRADE methodology) and the limitations of the review. Reporting follows guidelines such as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) to ensure transparency and completeness [3].

Experimental Protocols in Practice: A Blinded Comparison Study

To illustrate the application of a rigorous protocol, consider a prospective, blinded study comparing two laryngoscopy techniques, which serves as an analogue for the level of methodological rigor required in systematic reviews.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for a comparative laryngoscopy study

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Rigid 70° Telescope (RTL) | High-resolution optical instrument for laryngeal examination. Provides superior image quality for anatomical detail [16]. |

| Flexible Distal-Chip Laryngoscope (FDL) | A flexible scope passed through the nasal passage, allowing for examination during natural speech and in patients with a strong gag reflex [17] [16]. |

| Laryngeal Stroboscope Light Source | Provides intermittent light pulses that create a slow-motion illusion of vocal fold vibration, essential for assessing vocal fold function [17]. |

| Video Recording System | Used to capture and store examination videos for subsequent blinded and randomized review by multiple raters, ensuring objective comparison [16]. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The following protocol is adapted from a study comparing image quality between flexible and rigid laryngoscopy [16].

- Study Design: Prospective cohort study; blinded comparison.

- Subject Recruitment: Eighteen normal adult subjects were recruited. Written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment.

- Intervention/Comparison: Each subject underwent two examination procedures:

- Rigid Telescopic Laryngoscopy (RTL): Performed using a 70° rigid scope with an outer diameter of 10 mm.

- Flexible Distal-Chip Laryngoscopy (FDL): Performed using a flexible distal-chip endoscope.

- Video Processing and Randomization: Recorded videos from both modalities were normalized and then randomized to blind the raters to the technique used for each video.

- Outcome Measurement: Three blinded, experienced laryngologists rated the randomized videos independently. They assessed the following image quality parameters, indicating superiority for RTL, FDL, or no difference:

- Color fidelity

- Illumination

- Resolution

- Tissue vascularity

- Visualization of abnormalities

- Data Analysis: Differences in responses were analyzed using non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Fleiss' kappa, and intra-rater reliability was assessed via percent agreement.

Quantitative Results from the Protocol

The rigorous application of this protocol yielded clear, quantifiable results.

Table 3: Summary of quantitative findings from the laryngoscopy comparison study [16]

| Assessment Category | RTL Superior | FDL Superior | No Difference | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color Fidelity | 47 | 5 | 8 | < 0.01 |

| Illumination | 47 | 7 | 6 | < 0.01 |

| Resolution | 51 | 5 | 4 | < 0.01 |

| Tissue Vascularity | 44 | 9 | 7 | < 0.01 |

| Visualization of Abnormalities | 29 | 4 | - | < 0.01 |

The data synthesis showed a significant superiority of RTL in all assessed categories of image quality. Furthermore, when abnormalities were visualized by both methods, they were significantly better seen with RTL [16]. This demonstrates how a pre-specified, blinded protocol produces objective, high-quality evidence for comparing two techniques.

The choice between a flexible narrative review and a rigorous systematic review is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is the correct tool for the specific research objective at hand. Narrative reviews, with their flexible workflow, are invaluable for mapping a vast and complex field, providing context, and generating novel hypotheses. They are the starting point for deep exploration. In contrast, systematic reviews, governed by their rigorous, pre-specified protocols, are the definitive tool for answering focused questions, validating efficacy, and generating evidence that can reliably inform clinical practice and policy in materials science and drug development. By understanding and correctly implementing these distinct workflows, researchers can ensure their contributions are both meaningful and methodologically sound.

This technical guide explores two advanced domains within materials science—multifunctional nanoparticles and the mechanical analysis of fibrous networks—to illustrate the distinct applications of narrative and systematic review methodologies. The field of materials science is characterized by rapid innovation in areas such as nanotechnology and biomaterials, which present unique challenges and opportunities for evidence synthesis [18] [19]. Through detailed experimental protocols, data quantification, and visual workflows, this whitepaper demonstrates how the complementary strengths of systematic and narrative reviews address different research questions within materials science. The comparative analysis provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a framework for selecting appropriate review methodologies based on research objectives, scope, and required evidentiary standards.

Materials science represents an interdisciplinary field that investigates the relationships between structure, processing, properties, and performance of materials [19]. The relentless march of progress across industries—from aerospace and healthcare to renewable energy and consumer electronics—is underpinned by profound revolutions in materials science [19]. As the discipline evolves toward increasingly complex material systems, researchers face challenges in synthesizing evidence from diverse experimental and computational approaches.

The selection of an appropriate literature review methodology is pivotal for advancing materials science research. Systematic reviews and narrative reviews offer complementary approaches for evidence synthesis, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings and methodological frameworks [3] [20]. Systematic reviews employ explicit, reproducible methods to minimize bias, making them ideal for clinical questions about material effectiveness or safety [20]. In contrast, narrative reviews provide flexible, thematic syntheses that contextualize broad research landscapes, making them valuable for exploring emerging fields or theoretical frameworks [2].

This whitepaper examines how these review methodologies apply to materials science through two illustrative examples: multifunctional nanoparticle applications and fibrous network biomechanics. These domains exemplify the diverse character of materials science research, from applied nanotechnology to fundamental mechanical analysis.

Methodological Foundations: Systematic vs. Narrative Reviews

Defining Characteristics and Applications

The fundamental distinction between review methodologies lies in their approach to evidence synthesis. Systematic reviews follow prespecified protocols with explicit, replicable methods to minimize bias, while narrative reviews employ thematic organization to provide conceptual clarity and theoretical frameworks [3] [20] [2].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Systematic and Narrative Reviews

| Characteristic | Systematic Review | Narrative Review |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Answer specific clinical/research questions through evidence synthesis | Provide contextual overview, identify gaps, develop theoretical foundations |

| Methodology | Strict protocol, predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria, comprehensive search | Flexible approach, thematic organization, selective literature use |

| Bias Management | Explicit quality assessment, attempts to minimize bias | Potential for selection and interpretation bias |

| Evidence Synthesis | Quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative systematic integration | Critical interpretation, thematic synthesis |

| Applications in Materials Science | Efficacy of biomaterials, safety assessments, comparative performance | Emerging material trends, historical perspectives, interdisciplinary connections |

Methodological Workflows

The conducted methodologies follow distinct processes tailored to their respective objectives. Systematic reviews employ a linear, predefined protocol, whereas narrative reviews follow an iterative, thematic approach.

Illustrative Example 1: Multifunctional Nanoparticle Applications

Research Context and Appropriate Review Methodology

Nanoparticles exhibit distinctive physicochemical characteristics that facilitate progress across domains including biomedicine, energy, environment, and electronics [21]. The multifunctionality of nanoparticles stems from their unique physical properties—mechanical, thermal, electrical, and optical—which enable diverse applications from targeted drug delivery to environmental remediation [21].

For this rapidly evolving, interdisciplinary field, a narrative review methodology is particularly appropriate. The breadth of applications, diversity of synthesis methods, and emerging character of the evidence base make a rigid systematic review impractical for exploring the full scope of nanoparticle multifunctionality [2]. A narrative approach allows researchers to trace conceptual developments, identify emerging trends, and synthesize knowledge across disciplinary boundaries.

Quantitative Analysis of Nanoparticle Applications

The diverse applications of nanoparticles leverage different physical properties and synthesis approaches, creating a complex landscape of functionality.

Table 2: Multifunctional Applications of Nanoparticles by Domain and Key Characteristics

| Application Domain | Key Nanoparticle Types | Primary Physical Properties Leveraged | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Delivery Systems | Polymeric NPs, Liposomes, Dendrimers | Size, surface functionality, release kinetics | Clinical trials for targeted therapies |

| Medical Imaging | Quantum dots, Iron oxide NPs, Gold NPs | Optical, magnetic, plasmonic properties | Preclinical and clinical development |

| Energy Storage | Metal oxide NPs, Carbon NPs | High surface area, electrical conductivity | Commercialization in batteries and supercapacitors |

| Environmental Remediation | Iron NPs, Titanium dioxide NPs | Catalytic activity, reactivity, surface area | Field testing for groundwater treatment |

| Electronics | Semiconductor NPs, Metallic NPs | Quantum confinement, electrical properties | Commercial use in displays, R&D in computing |

Experimental Protocol: Hybrid Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

The development of multifunctional nanoparticles increasingly employs hybrid approaches that combine organic and inorganic components to enhance stability, functionality, and reduce negative impacts [21].

Objective: To synthesize and characterize hybrid nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery applications.

Materials and Equipment:

- Precursors: Biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA), therapeutic agent, targeting ligand

- Solvents: Dichloromethane, aqueous surfactant solution

- Equipment: Sonicator, centrifuge, freeze-dryer, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument, transmission electron microscope (TEM)

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Dissolve polymer and drug in organic solvent

- Emulsify using probe sonication in aqueous surfactant solution

- Evaporate organic solvent under reduced pressure

- Purify nanoparticles by centrifugation

- Lyophilize with cryoprotectant for storage

Physicochemical Characterization:

- Size and Distribution: Analyze by DLS and TEM

- Surface Charge: Determine zeta potential using electrophoretic light scattering

- Drug Loading: Quantify using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy

- Surface Functionality: Confirm using FTIR or X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

In Vitro Evaluation:

- Drug Release: Use dialysis method with sink conditions

- Cellular Uptake: Employ flow cytometry and confocal microscopy

- Cytotoxicity: Assess using MTT or similar assays

The hybrid synthesis approach improves stability and functionality while reducing negative impacts, addressing key challenges in nanoparticle implementation [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoparticle Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix Materials | PLGA, Chitosan, PEG, PCL | Biodegradable backbone for nanoparticle structure, controlled release |

| Surface Modifiers | PEG derivatives, PVA, Poloxamers | Stabilize nanoparticles, reduce opsonization, enhance circulation time |

| Characterization Kits | Zeta potential standards, Size calibration beads | Instrument calibration, measurement standardization |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cell lines (HeLa, HEK293), FBS, culture media | In vitro assessment of biocompatibility and efficacy |

| Analytical Standards | HPLC standards, Reference materials | Quantification of drug loading and release kinetics |

Illustrative Example 2: Fibrous Network Analysis - Fibrin Clots

Research Context and Appropriate Review Methodology

Fibrous networks constitute a fundamental structural motif in biological systems and engineered materials. Fibrin clots, the mechanical scaffold of blood clots, represent an important model system for understanding the rupture mechanisms that underlie embolization of intravascular thrombi—a major cause of ischemic stroke and pulmonary embolism [22].

For this focused, mechanistic research domain, a systematic review methodology is most appropriate. The well-defined research question ("What are the mechanisms of fibrin rupture and how does fracture toughness predict embolization risk?") and the availability of quantitative experimental data make this domain suitable for systematic synthesis [22]. The systematic approach enables rigorous comparison of mechanical properties across studies and statistical analysis of structure-function relationships.

Quantitative Analysis of Fibrin Clot Mechanics

Multiscale mechanical testing reveals fundamental relationships between fibrous network structure and failure mechanisms.

Table 4: Mechanical Properties of Fibrin Clots Under Various Conditions

| Mechanical Parameter | Testing Method | Representative Values | Significance/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture Toughness | Crack propagation experiments | 2.5-7.7 J/m² at physiological volume fraction | Determines rupture resistance with defects |

| Critical Strain | Tensile testing | >50% strain for damage initiation | Point at which network damage begins |

| Failure Threshold | Combined experimental and computational | ~5% of fibers and branch points break | Minimal structural failure leading to rupture |

| Rupture Zone Size | In silico modeling | ~150 µm opening in rupture zone | Spatial scale of catastrophic failure |

| Volume Reduction | Uniform tensile stressing | ~90% decrease in volume | Dramatic densification under stress |

Experimental Protocol: Multiscale Mechanical Analysis

A multiscale approach combining discrete particle-based simulations and large-deformation continuum mechanics has been developed to explore the mechanobiology, damage, and fracture of fibrous materials [22].

Objective: To characterize the strength, deformability, damage progression, and fracture toughness of fibrin networks through integrated computational and experimental approaches.

Materials and Equipment:

- Biological: Purified fibrinogen, thrombin, calcium chloride buffer

- Experimental: Rheometer with custom fixtures, confocal microscope, traction force microscopy

- Computational: Molecular dynamics software, finite element analysis platform, custom MATLAB/Python scripts

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Form fibrin networks at physiological concentration (2-5 mg/mL)

- Control polymerization conditions (thrombin concentration, ionic strength) to modulate network structure

- Allow complete polymerization before testing

Mechanical Testing:

- Rheometry: Perform strain sweeps (0.1-100% strain) to determine linear viscoelastic region

- Confocal Rheometry: Image network deformation during shear using fluorescent fibrinogen

- Tensile Testing: Measure stress-strain response to failure using microtensile fixtures

Computational Modeling:

- Discrete Network Simulation: Implement mesoscale model with individual fibers and crosslinks

- Damage Incorporation: Introduce stochastic failure rules for fibers and branch points

- Continuum Model Development: Construct constitutive model from discrete simulations

- Fracture Prediction: Compute fracture toughness using continuum model

Data Integration:

- Correlate experimental stress-strain data with computational predictions

- Map damage progression from simulation to experimental observations

- Validate fracture toughness predictions against experimental measurements

This protocol's multiscale approach is applicable to a wide range of fibrous network-based biomaterials, enabling prediction of fracture toughness and damage evolution [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Fibrous Network Analysis

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Fibrin Clot and Fibrous Network Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Clotting Components | Purified fibrinogen, Thrombin, Factor XIII | Controlled formation of fibrin networks with defined structure |

| Fluorescent Labels | FITC-fibrinogen, Alexa Fluor conjugates | Visualization of network structure and deformation during mechanical testing |

| Protease Inhibitors | Aprotinin, Leupeptin, PMSF | Prevent clot degradation during extended experiments |

| Computational Tools | Custom MATLAB scripts, LAMMPS, Abaqus | Multiscale modeling from discrete networks to continuum mechanics |

| Calibration Standards | Rheometer calibration fluids, Microsphere size standards | Instrument validation and measurement accuracy |

Workflow Visualization: Multiscale Analysis of Fibrous Networks

The integrated experimental-computational approach enables comprehensive characterization of fibrous network mechanics across length scales.

Comparative Analysis: Methodology Selection in Materials Science

Decision Framework for Review Methodology Selection

The selection between systematic and narrative review methodologies depends on multiple factors related to the research question, evidence base, and intended application.

Table 6: Decision Framework for Selecting Review Methodologies in Materials Science

| Consideration | Favor Systematic Review | Favor Narrative Review |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | Focused, specific (e.g., efficacy comparison) | Broad, exploratory (e.g., emerging trends) |

| Evidence Base | Substantial existing studies, potential for statistical synthesis | Limited or heterogeneous studies, qualitative insights needed |

| Time/Resources | Sufficient for comprehensive search and appraisal | Limited timeframe, need for rapid overview |

| Methodological Context | Established protocols exist (e.g., PRISMA, Cochrane) | Emerging field with diverse methodologies |

| Intended Application | Clinical guidance, policy decisions, regulatory submissions | Hypothesis generation, theoretical development, educational purposes |

Comparative Strengths and Limitations in Materials Science Context

Each review methodology offers distinct advantages and faces particular challenges when applied to materials science research questions.

Systematic Review Strengths:

- Minimizes bias in evaluating material efficacy or safety

- Supports evidence-based decision making in regulatory contexts

- Enables statistical synthesis through meta-analysis when appropriate

- Provides definitive answers to focused research questions

Systematic Review Limitations:

- May exclude emerging or preliminary evidence

- Resource-intensive process requiring specialized skills

- Less suitable for highly interdisciplinary or exploratory topics

- Potential for "empty reviews" when evidence is limited

Narrative Review Strengths:

- Accommodates diverse evidence types and quality

- Identifies conceptual connections across disciplines

- Provides historical context and traces theoretical developments

- Adaptable to emerging research trends and innovations

Narrative Review Limitations:

- Vulnerable to selection and interpretation bias

- Limited reproducibility of search and selection methods

- Challenges in comprehensively covering rapidly expanding fields

- Difficult to assess thoroughness of literature coverage

The illustrative examples presented in this whitepaper demonstrate how systematic and narrative review methodologies serve complementary roles in advancing materials science research. The multifunctional applications of nanoparticles benefit from narrative review approaches that can synthesize knowledge across disciplinary boundaries and identify emerging trends [21] [2]. In contrast, the mechanical analysis of fibrin clots exemplifies how systematic review methodologies provide rigorous evidence synthesis for focused research questions with established experimental paradigms [22].

Materials science continues to evolve toward increasingly complex material systems, with emerging areas such as metamaterials, aerogels, smart materials, and sustainable composites presenting new challenges for evidence synthesis [18] [19]. The ongoing integration of computational methodologies, including machine learning and multiscale modeling, further expands the methodological toolkit available to materials researchers [22] [19]. By strategically applying systematic and narrative review methodologies to appropriate research contexts, materials scientists and drug development professionals can effectively navigate this complex landscape, accelerating the translation of material innovations to practical applications that address global challenges in healthcare, sustainability, and technology.

Executing Your Review: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide for Materials Scientists

A systematic review is a comprehensive literature search that attempts to answer a focused research question using existing research as evidence [23]. Unlike narrative reviews, which provide descriptive summaries with more flexibility in methodology, systematic reviews employ robust, reproducible, and transparent methods to collate and critically appraise all eligible literature on a specific topic [3]. The primary aims of systematic reviews are to recommend best practices, support regulatory submissions, inform reimbursement decisions, and guide policy development, establishing them as the gold standard in evidence-based medicine [3].

The critical importance of the systematic review protocol lies in its role as the foundational blueprint for the entire review process. A well-developed protocol outlines the study methodology before the review begins, minimizing the risk of selective reporting and reducing arbitrary decision-making by the review team [23] [24]. Protocol registration through platforms like PROSPERO, INPLASY, or Open Science Framework helps avoid research duplication, increases transparency, and enhances the credibility of the final review by demonstrating that methods were established a priori [23] [24].

Table: Comparison of Systematic and Narrative Reviews

| Characteristic | Systematic Review | Narrative Review |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Answers specific clinical/research question | Broad exploration of topic, identifies gaps |

| Methodology | Explicit, pre-specified, reproducible protocol (e.g., PICO) | Flexible structure, often IMRAD format |

| Search Strategy | Comprehensive, multiple databases, documented | Often unspecified, potentially non-reproducible |

| Study Selection | Pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria | Subjective selection by author |

| Bias Management | Rigorous critical appraisal, risk of bias assessment | Variable quality assessment |

| Application | Evidence-based guidelines, policy, regulatory decisions | Background, context, theory development |

The PICO Framework: Formulating the Research Question

Framework Components and Application

The PICO framework is the most commonly used structure for formulating research questions in health-related systematic reviews [25] [24]. A well-formulated question guides all aspects of the review process, including determining eligibility criteria, searching for studies, collecting data, and presenting findings [25]. PICO specifies the type of:

- P (Patient, Population, or Problem): The disease, condition, or patient group under investigation, including relevant characteristics like age, gender, or other demographic factors when appropriate [25] [24].

- I (Intervention, Prognostic Factor, or Exposure): The main therapy, diagnostic test, exposure, or other intervention being considered [25] [24].

- C (Comparison): The alternative against which the intervention is compared, which may include placebo, standard care, no treatment, or a different active intervention [25] [24].

- O (Outcome): The measurable outcomes of interest, including clinical endpoints, quality of life measures, or other relevant effects [25] [24].

Table: PICO Framework in Practice: An Intervention Example

| PICO Element | Description | Example from a Therapeutic Question |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Women who have experienced domestic violence | |

| Intervention | Advocacy programs | |

| Comparison | General practice or routine treatment | |

| Outcome | Quality of Life (measured by the SF-36 scale) | |

| Research Question | "For women who have experienced domestic violence, how effective are advocacy programmes as compared with routine general practice treatment for improving women's quality of life (as measured by the SF-36 scale)?" |

Alternative Frameworks for Different Research Questions

While PICO is most common for intervention questions, other frameworks may be more suitable depending on the review topic and discipline [24]:

- PECO: Population | Environment | Comparison | Outcome – for questions about exposure effects

- SPICE: Setting | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Evaluation – adds contextual setting

- SPIDER: Sample | Phenomenon of Interest | Design | Evaluation | Research Type – better suited for qualitative and mixed-methods research

The type of question being asked directly influences the study designs to be included in the review [25]. For therapeutic questions, Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) provide the highest level of evidence, while other study designs may be more appropriate for diagnostic, prognostic, or qualitative questions [25].

Developing the Systematic Search Strategy

Building Search Concepts and Vocabulary

A systematic review requires a search strategy that is comprehensive, explicit, and sufficiently detailed to be reproducible [26]. The search strategy should be informed by the main concepts from the PICO framework, though not every PICO element may be needed in the search [26]. A thorough approach involves:

Identifying Synonyms and Alternative Terms: Authors may use different words to describe the same concept, so comprehensive synonym development is essential [26]. Consider:

- Different spellings (e.g., paediatric/pediatric)

- Different terminology (e.g., physiotherapy/physical therapy)

- Medical terminology versus natural language (e.g., hypertension/high blood pressure)

- Brand names versus generic names for medications

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Plural and singular word forms

- Hyphenated words [26]

Incorporating Subject Headings: Databases use controlled vocabularies (e.g., MeSH for MEDLINE, APA Thesaurus for PsycINFO, CINAHL Headings for CINAHL) that are consistently applied to articles on the same topic [26]. Combining subject headings with free-text terms ensures a comprehensive search [26].

Applying Search Techniques: Use Boolean operators (OR within concepts, AND between concepts), truncation for word variants, phrase searching with quotation marks, and field codes to restrict searches to title/abstract fields when appropriate [26].

Structuring and Executing the Search

There are three main approaches to structuring systematic search strategies:

- Line by line: Each search term on its own line

- Block by block: Each search concept (PICO element) on its own line

- Single line: All search terms and concepts combined into one line [26]

The block-by-block approach is often preferred, with each PICO concept structured as: (Concept1[tiab] OR synonym1[tiab] OR synonym2[tiab] OR "subject heading"[MeSH]) [26]. The search strategy should be translated and adapted for each database, accounting for differences in subject headings and search syntax [26].

Systematic Search Strategy Development Workflow

Search Documentation and Reporting

Thorough documentation of the search process is essential for transparency and reproducibility. For each database search, record [25] [26]:

- Date the search was run

- Database name and platform used

- Complete search strategy (copied and pasted exactly as run)

- Any limits applied (date, language, study design)

- Number of studies identified

- Any published search filters used

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram provides a standardized way to depict the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review, mapping the number of records identified, included, and excluded, with reasons for exclusions [25]. The PRISMA-S extension offers specific guidance for reporting search strategies [26].

Defining Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Developing Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Well-defined eligibility criteria form the backbone of a systematic review, specifying attributes studies must have (inclusion criteria) or must not have (exclusion criteria) to be selected [23] [24]. These criteria should be sufficiently clear and detailed to enable accurate assessment of each study's relevance and are typically structured using the PICO framework [25]. The criteria should explicitly define:

- Population characteristics: Specific diagnoses, age ranges, demographic factors, disease stages, or other relevant population attributes

- Intervention specifics: Dosage, delivery method, duration, intensity, and implementation details

- Comparator specifications: Standard care, placebo, active comparator, or other control conditions

- Outcome measures: Primary and secondary outcomes, measurement tools, timing of assessment

- Study designs: Accepted methodologies (RCTs, observational studies, etc.) based on the question type

- Other practical considerations: Publication date ranges, language restrictions, publication status [25] [23] [24]

Study Selection Process

The study selection process typically involves multiple screening phases [25]:

- Title/Abstract Screening: Initial assessment of search results against eligibility criteria

- Full-Text Review: Detailed evaluation of potentially relevant studies

- Final Inclusion Decision: Application of all criteria to determine included studies

Using a review management tool such as Covidence or Rayyan can streamline this process, particularly for large reviews. At least two reviewers should independently assess studies, with procedures established for resolving disagreements [23]. The reasons for excluding studies at the full-text stage should be recorded and reported in the PRISMA flow diagram [25].

Table: Essential Materials for Systematic Review Execution

| Research Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function in Systematic Review |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Registration | PROSPERO, INPLASY, Open Science Framework, Research Registry | Public protocol registration to avoid duplication and reduce bias [23] [24] |

| Search Platforms | MEDLINE (PubMed/Ovid), EMBASE, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, Scopus | Comprehensive literature searching across multiple databases [26] |

| Reference Management | EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley | Storage, organization, and duplicate removal of search results [26] |

| Review Management | Covidence, Rayyan, RevMan (Cochrane) | Screening, data extraction, and quality assessment workflow management [24] |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA, PRISMA-P, PRISMA-S | Standardized reporting of methods and findings [25] [23] |

| Quality Assessment | Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, ROBINS-I, GRADE | Critical appraisal of included studies [23] |

The systematic review protocol, encompassing the PICO framework, comprehensive search strategy, and explicit eligibility criteria, represents the critical foundation for a methodologically sound evidence synthesis. By investing substantial effort in developing and registering a detailed protocol before commencing the review, researchers ensure their work meets the highest standards of transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. This structured approach differentiates systematic reviews from traditional narrative reviews and provides the reliable, bias-minimized evidence needed to inform clinical decision-making, policy development, and regulatory standards across scientific disciplines, including materials science and drug development.