Strategies for Reducing Host DNA Contamination in Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is revolutionizing pathogen detection and microbiome studies, but its accuracy is critically limited by high levels of host nucleic acids in clinical samples.

Strategies for Reducing Host DNA Contamination in Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is revolutionizing pathogen detection and microbiome studies, but its accuracy is critically limited by high levels of host nucleic acids in clinical samples. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate host DNA depletion strategies. We explore the fundamental challenges posed by host contamination across different sample types, benchmark current methodological approaches including physical separation, enzymatic digestion, and commercial kits, and present optimization and troubleshooting protocols for low-biomass scenarios. Finally, we validate methods through comparative performance analysis and discuss emerging solutions for achieving reliable, clinically actionable metagenomic data in biomedical research.

The Host DNA Problem: Understanding the Fundamental Challenge in Metagenomic Sequencing

The Impact of Host DNA on Sequencing Sensitivity and Specificity

Host DNA contamination presents a major challenge in metagenomic sequencing, particularly for samples derived from host-associated environments. The overwhelming abundance of host genetic material can severely impair the detection and accurate characterization of microbial communities. This technical support article details the specific impacts of host DNA on sequencing sensitivity and specificity, provides troubleshooting guidance, and outlines effective strategies to mitigate these issues within the broader context of reducing host DNA contamination in metagenomic research.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

How does host DNA proportion affect the sensitivity of microbe detection?

Increasing proportions of host DNA directly decrease the sensitivity of detecting low-abundance microorganisms. In a controlled study using a synthetic microbial community, samples with 99% host DNA showed a significant drop in sensitivity, leading to an increased number of undetected species, especially those at very low and low abundance levels [1] [2]. This occurs because, at a fixed sequencing depth, a higher fraction of host DNA means fewer sequencing reads are available to cover the microbial genomes.

What is the relationship between sequencing depth and host DNA levels?

Reduced sequencing depth has a major negative impact on the sensitivity of whole metagenome sequencing for profiling samples with high host DNA content (e.g., 90%) [1] [2]. When host DNA dominates a sample, a much greater total sequencing depth is required to obtain sufficient microbial reads for reliable analysis. Analysis of simulated datasets with a fixed depth of 10 million reads confirmed that microbiome profiling becomes increasingly inaccurate as the level of host DNA increases [1] [2].

Can bioinformatic tools compensate for high host DNA content?

Yes, the choice of bioinformatic tools can influence sensitivity. While one study using MetaPhlAn2 reported nine species became undetectable in samples with 99% host DNA, a reanalysis of the same data with Kraken 2 and Bracken detected all 20 expected organisms across all host DNA levels (10%, 90%, 99%) [3]. Read binning tools like Kraken 2 can remain sensitive to low-abundance organisms even with high host DNA content. However, high host DNA content exacerbates the impact of contamination, as off-target reads can come to represent over 10% of microbial reads [3]. Tools like Decontam can help remove a significant percentage of these off-target reads [3].

What are the main methods for depleting host DNA before sequencing?

Host DNA depletion methods can be categorized as pre-extraction and post-extraction methods. A recent benchmark of seven pre-extraction methods for respiratory samples showed all methods significantly increased microbial reads and reduced host DNA, but they also introduced varying levels of contamination and altered microbial abundance [4]. The following table summarizes the performance of these methods in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) samples:

Table 1: Performance of Host DNA Depletion Methods in BALF Samples

| Method | Description | Microbial Read Increase (Fold vs. Raw) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K_zym | HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit (Commercial) | 100.3-fold | Best performance in increasing microbial reads [4] |

| S_ase | Saponin Lysis + Nuclease Digestion | 55.8-fold | High host DNA removal efficiency [4] |

| F_ase | 10μm Filtering + Nuclease Digestion | 65.6-fold | Balanced performance (new method) [4] |

| K_qia | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Commercial) | 55.3-fold | High bacterial retention rate in OP samples [4] |

| O_ase | Osmotic Lysis + Nuclease Digestion | 25.4-fold | - |

| R_ase | Nuclease Digestion | 16.2-fold | Highest bacterial retention rate in BALF [4] |

| O_pma | Osmotic Lysis + PMA Degradation | 2.5-fold | Least effectiveness [4] |

Why is host contamination a particular concern for low-biomass samples?

In low microbial biomass samples, the quantity of contaminant DNA from reagents, kits, or the environment can remain constant. Therefore, its relative contribution to the total DNA in the sample becomes much larger, potentially dominating the signal and leading to spurious results [3] [5]. The problem is proportional: the lower the target microbial DNA, the more influential the contaminant "noise" becomes [5].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Generating Synthetic Samples to Benchmark Host DNA Impact

This protocol is based on the methodology used in Pereira-Marques et al. (2019) [1] [2].

- Objective: To systematically evaluate the impact of known ratios of host DNA on microbiome taxonomic profiling.

- Materials:

- Genomic DNA from a defined mock microbial community (e.g., BEI Resources HM-277D).

- Host genomic DNA (e.g., from a mouse or human cell line).

- DNA quantification instrument (e.g., NanoDrop).

- Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay.

- Method:

- Quantify the DNA concentration of both the mock microbial community and the host DNA stock.

- Mix the DNA in precise volumes to generate synthetic samples with defined host DNA ratios (e.g., 10%, 90%, 99%).

- Normalize all samples to the same final DNA concentration (e.g., 0.2 ng/μL) using a fluorescence-based assay like PicoGreen.

- Proceed with standard metagenomic library preparation (e.g., Nextera XT kit) and sequencing on a platform such as Illumina NextSeq to a fixed depth (e.g., 5.5 Gb per sample).

- Downstream Analysis:

- Process raw reads through a quality control and host read removal pipeline (e.g., KneadData).

- Perform taxonomic profiling using different tools (e.g., MetaPhlAn2, Kraken 2/Bracken) and compare the sensitivity and accuracy of microbial detection and abundance estimates across the different host DNA levels.

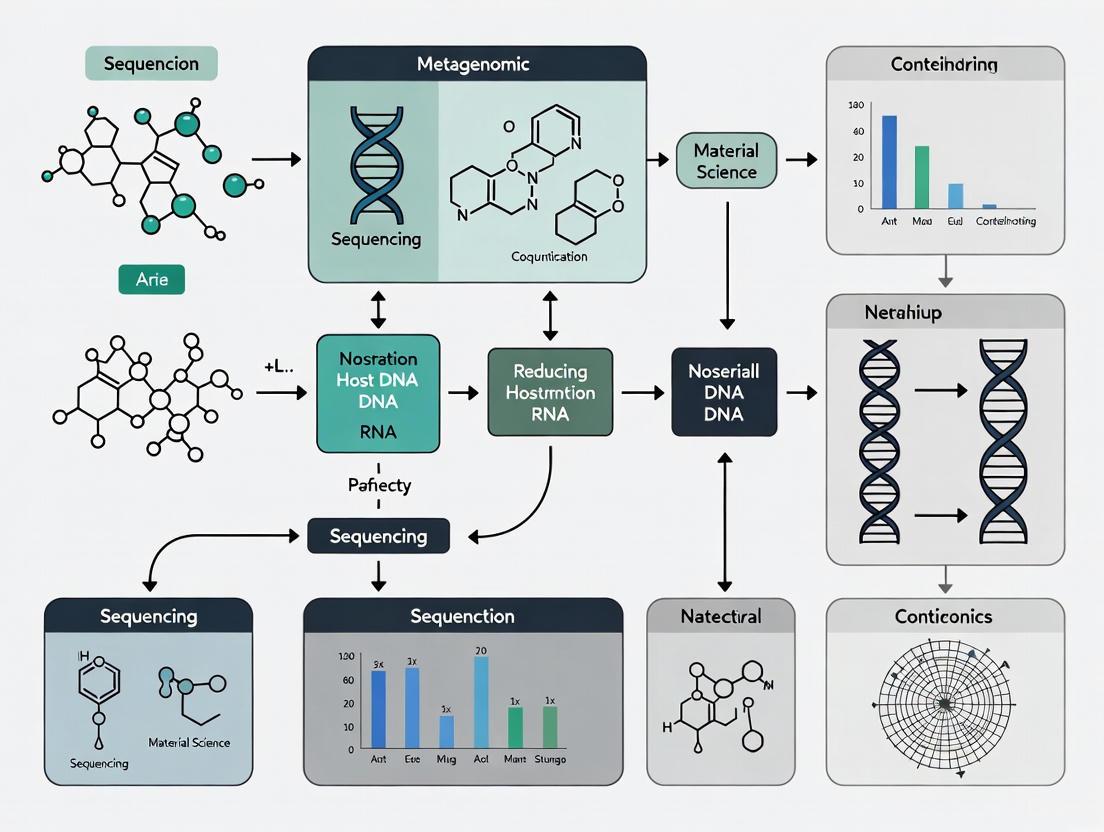

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for assessing host DNA impact.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Host DNA Depletion Methods

This protocol is adapted from the comprehensive comparison in Chen et al. (2025) [4].

- Objective: To evaluate the performance of different host DNA depletion methods on a specific sample type.

- Materials:

- Respiratory samples (e.g., BALF, oropharyngeal swabs) or other target sample.

- Reagents for host depletion methods (e.g., saponin, nucleases, PMA, commercial kits like QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit or HostZERO).

- qPCR equipment for quantifying host and bacterial DNA loads.

- Method:

- Aliquot a single, well-homogenized sample for each depletion method to be tested and a "Raw" (no depletion) control.

- Apply the host depletion methods according to their optimized protocols. For example:

- Sase: Treat with low-concentration saponin (e.g., 0.025%) to lyse host cells, followed by nuclease digestion to degrade released DNA.

- Fase: Pass sample through a 10μm filter to separate microbial cells from host cells, followed by nuclease digestion of cell-free DNA.

- Commercial Kits: Follow manufacturer's instructions.

- Extract DNA from all processed samples and the raw control using the same extraction kit.

- Quantify the residual host DNA and bacterial DNA load in each sample using targeted qPCR assays.

- Subject all samples to shotgun metagenomic sequencing under identical conditions.

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Effectiveness: Host DNA load post-depletion, fold-increase in microbial reads.

- Fidelity: Bacterial DNA retention rate, changes in microbial community composition (using a mock community).

- Contamination: Presence of new species not in the raw sample or mock community.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Host DNA Contamination Research

| Item | Function | Example Products / Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Communities | Provides a defined standard with known microbial abundances to benchmark performance and quantify bias. | BEI Resources Mock Community B (HM-277D) [1] [2] |

| Host DNA Depletion Kits | Selectively removes host DNA from a sample to increase microbial sequencing yield. | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit, HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [4] |

| Probe-based qPCR Assays | Highly sensitive and specific quantification of residual host cell DNA in samples [6] [7]. | Cygnus AccuRes kits, in-house designed TaqMan assays |

| Bioinformatic Classification Tools | Assigns taxonomy to sequencing reads; some are more resilient to high host DNA content. | Kraken 2, Bracken, MetaPhlAn2 [3] |

| Contaminant Identification Tools | Statistically identifies and removes contaminant sequences from feature tables post-sequencing. | Decontam (R package) [3] |

| Comprehensive Decontamination Pipelines | Removes unwanted sequences (host, spike-ins, rRNA) from reads or assemblies in a reproducible workflow. | CLEAN pipeline [8] |

| Foreign Contamination Screeners | Rapidly identifies and removes cross-species contaminant sequences from genome assemblies. | FCS-GX (NCBI) [9] |

Best Practices and Visual Workflow for Mitigation

Effective management of host DNA requires a multi-faceted approach, integrating both laboratory and computational strategies. The following workflow outlines a decision process for tackling host DNA issues:

Diagram 2: Decision workflow for host DNA mitigation.

Key best practices derived from recent guidelines and studies include [3] [4] [5]:

- Pre-analytical Precautions: For low-biomass samples, use single-use DNA-free consumables, decontaminate equipment with bleach or UV-C light, and wear appropriate PPE to limit contamination from operators [5].

- Include Comprehensive Controls: Collect and process negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, sampling fluids) alongside samples to identify contamination sources introduced during the entire workflow [5].

- Select a Balanced Depletion Method: Choose a host depletion method that offers a good balance between high host removal efficiency and minimal loss of or bias against specific microbial taxa. Methods like F_ase (filtering + nuclease) have been noted for their balanced performance [4].

- Combine Wet and Dry-lab Strategies: Utilize laboratory-based host depletion methods in conjunction with sensitive bioinformatic tools (Kraken 2) and post-hoc contamination filters (Decontam, CLEAN) for the most robust results [3] [8].

In metagenomic sequencing, the quantity of microbial material, or biomass, varies dramatically across sample types. High-biomass samples, like stool, contain abundant microbial DNA. In contrast, low-biomass samples—such as those from the respiratory tract, urine, or blood—contain minimal microbial material, making them exceptionally vulnerable to contamination by foreign DNA [10] [5]. This technical guide provides targeted strategies to mitigate host and environmental DNA contamination, ensuring the integrity of your sequencing results across diverse sample types.

Key Characteristics of Sample Types

| Sample Type | Typical Microbial Biomass | Primary Contamination Risks | Key Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool (High-Biomass) | High (e.g., ~1012 CFU/g) [10] | Lower relative impact of contaminants; cross-contamination between samples. | Standard protocols often sufficient; focus on preventing cross-contamination [5]. |

| Urine (Low-Biomass) | Low (often < 105 CFU/mL) [10] | Contaminants from collection equipment, reagents, skin flora (in voided samples) [10]. | Larger collection volumes (e.g., 30-50 mL); catheter collection preferred for bladder studies; critical need for negative controls [10] [5]. |

| Respiratory (Low-Biomass) | Low (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs) [11] | Contaminants from sampling kits, reagents, and the laboratory environment [11]. | Consistent use of the same DNA extraction kit batch; extensive negative controls are mandatory [11]. |

Best Practices for Contamination Control

Contamination control is a continuous process that must be integrated from the initial sampling design through to data analysis.

Sample Collection and Handling

The procedures at the collection stage are critical for preserving sample integrity.

- Urine Specimens: For bladder microbiota studies, transurethral catheterization is superior to clean-catch midstream collection, as the latter is frequently contaminated by microbiota from the vulvovaginal area or urethra [10]. If clean-catch is used, techniques like labial separation supervised by trained personnel can help minimize contamination.

- General Low-Biomass Collection:

- Decontaminate Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection tools. Reusable equipment should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) [5].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Operators should wear gloves, masks, coveralls, and other appropriate PPE to reduce contamination from human skin, hair, or aerosols [5].

- Standardize Storage: Freeze samples at -80°C immediately after collection to minimize microbial changes. The impact of freezing delays on urine microbiota is not fully understood and should be avoided [10].

Laboratory Processing and Reagent Management

Low-biomass samples are highly susceptible to contamination from the laboratory environment and the reagents themselves.

- DNA Extraction Kits: Reagents and kits are a well-documented source of contaminating bacterial DNA [11]. For a single project, use the same batch of DNA extraction kits to minimize batch-to-batch variability [11].

- Include Comprehensive Controls: The use of negative controls is non-negotiable.

- Negative Controls: Include "blank" controls that contain no sample (e.g., sterile water) but are processed alongside your samples through DNA extraction and PCR. These controls identify contaminants present in your reagents and kits [5] [11].

- Sampling Controls: For environmental or surgical sampling, include controls such as swabs of the air, gloves, or sampling equipment to account for contaminants from the collection environment [5].

The following workflow outlines the critical phases for preventing contamination in low-biomass studies, from initial planning to final data interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and their functions for contamination-aware research are detailed in the table below.

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| DNA-free Water | Serves as a solvent in reactions where no background DNA is acceptable; used for preparing negative controls [11]. |

| Single-batch DNA Extraction Kits | Minimizes variability and background contamination introduced by different lots of commercial kits [11]. |

| Nucleic Acid Degrading Solutions | Destroys contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment. Sodium hypochlorite is a common example [5]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment | Creates a barrier between the operator and the sample, reducing contamination from skin and aerosols [5]. |

| UV-C Light Chamber | Sterilizes plasticware and tools by degrading nucleic acids on surfaces, making them DNA-free [5]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: Our sequencing results from low-biomass urine samples show a high abundance of taxa not typically associated with the bladder. What is the most likely cause?

This pattern strongly suggests contamination. The first step is to compare your results with the sequencing data from your negative controls (extraction and PCR blanks) [5] [11]. Taxa present in both your samples and the negative controls are likely reagent or kit-derived contaminants. Ensure you used a sufficient urine volume (e.g., 30-50 mL for catheter-collected urine) to maximize microbial DNA yield [10].

Q2: When extracting DNA from respiratory swabs, how can we minimize the impact of contaminating DNA present in the extraction kits themselves?

The most effective strategy is to use the same batch of DNA extraction kits for all samples in a study [11]. This ensures that the contaminant profile is consistent across all samples, making it easier to identify and subtract bioinformatically. Furthermore, always include multiple negative controls from the same kit batch to define this contaminant profile accurately [5] [11].

Q3: What are the best practices for decontaminating laboratory surfaces and equipment to protect low-biomass samples?

A two-step process is recommended:

- Apply 80% ethanol to kill viable microorganisms on surfaces.

- Follow with a DNA-degrading solution, such as diluted sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or a commercial DNA removal product, to destroy residual free DNA [5]. Note that autoclaving and ethanol alone do not effectively remove persistent environmental DNA.

Experimental Protocols for Low-Biomass Research

Protocol: Processing Catheter-Collected Urine for Microbiota Analysis

This protocol is designed to maximize target DNA yield while monitoring contamination.

- Collection: Collect a minimum of 30-50 mL of urine via transurethral catheterization directly into a sterile, DNA-free container [10].

- Storage: Immediately freeze the sample at -80°C. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles [10].

- Centrifugation: Thaw sample on ice and concentrate microbial cells by centrifugation (e.g., 20,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C). Carefully decant the supernatant.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from the pellet using a chosen kit. Critical Step: Process at least one "blank" negative control (sterile water) alongside every batch of samples using the same kit and reagents [5] [11].

- Amplification & Sequencing: Proceed with library preparation and sequencing. Include a negative PCR control (water instead of DNA template) to detect contamination during amplification.

Protocol: Implementing and Using Negative Controls

- Types of Controls: Prepare both "extraction blanks" (no sample, carried through extraction) and "PCR blanks" (no template, carried through amplification) [11].

- Processing: Process all controls in parallel with actual samples under identical conditions, using the same reagents and equipment.

- Data Analysis: Sequentially analyze the control data first. Any taxa detected in these blanks are potential contaminants. Use this information to filter the experimental sample data via bioinformatic tools.

The diagram below illustrates how contaminants from various sources can enter a sample at different stages of the research workflow.

In metagenomic sequencing, the presence of host DNA is not just a technical nuisance; it represents a significant and direct economic burden on research and development. In samples with high host content, such as alveolar lavage fluid, over 90% of sequencing resources can be consumed ineffectively by host genetic material [12]. This guide details the economic impact of host contamination and provides actionable, cost-effective strategies for researchers to mitigate these losses, thereby increasing the value and output of their sequencing projects.

FAQs: The Economic Impact of Host DNA

Q1: How does host DNA directly increase my sequencing costs?

Host DNA increases costs through several direct mechanisms:

- Resource Dilution: Over 99% of sequences in metagenomic data can originate from the host, drastically reducing the number of reads available for target microorganisms and requiring deeper, more expensive sequencing to achieve sufficient microbial coverage [12].

- Wasted Sequencing Depth: In high-host-content samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), over 90% of sequencing resources can be wasted on host reads [12]. To detect a microbial signal, you may need to sequence 10-100 times deeper than in a host-depleted sample, directly multiplying library preparation and sequencing costs.

Q2: Which sample types are most susceptible to cost overruns from host DNA?

Clinical and tissue samples typically have the highest risk of cost inflation due to their high host DNA content. The following table summarizes the economic risk for common sample types:

| Sample Type | Relative Host DNA Load | Potential Microbial Read Ratio (without depletion) | Primary Cost Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | Very High | ~1:5,263 [13] | Extreme sequencing depth required |

| Tissue Biopsies (e.g., colon) | High | >99% host reads [12] | High resource waste; low sensitivity |

| Oropharyngeal Swabs | Medium | ~1:7 [13] | Moderate need for deeper sequencing |

| Saliva | Medium | ~65% host DNA (untreated) [14] | Moderately increased costs |

| Stool (Healthy donor) | Low | Low host DNA [14] | Lower risk of host-driven cost overruns |

Q3: Besides sequencing, what other parts of my budget are affected by host DNA?

The economic impact extends throughout the workflow:

- Data Storage and Transfer: Larger sequencing datasets from deeper runs require more server space and longer to transfer and process, increasing computing and cloud storage costs [15].

- Bioinformatics Personnel Time: More computational resources and analyst time are required to process, quality-check, and store the massive datasets, which are predominantly composed of unused host sequences [15].

- Reagent Costs: While host depletion methods have an upfront cost, they can lead to net savings by allowing shallower, more focused sequencing runs.

Q4: Can I just use bioinformatics to remove host reads instead of experimental depletion?

Bioinformatic removal is a crucial final step, but it is not a cost-saving alternative to experimental host DNA depletion. Tools like Bowtie2, BWA, and KneadData are highly effective at filtering out host sequences after sequencing [12]. However, this process does not recover the sequencing resources already spent on the host reads. You have already paid to generate, store, and process those useless sequences. Experimental depletion prevents this waste from the start.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Insufficient Microbial Sequencing Depth Despite High Sequencing Output

Symptoms:

- Final metagenomic report shows a very high percentage of reads mapped to the host genome (e.g., >95%).

- Low number of microbial reads, resulting in poor genome coverage and an inability to detect low-abundance species.

Root Cause: The sample contains a high concentration of host DNA that dominates the sequencing library.

Solutions:

- Implement a pre-sequencing host DNA depletion method. The choice of method depends on your sample type, budget, and required fidelity. The table below benchmarks several methods based on a 2025 study using Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) [13]:

For 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing, consider the Cas-16S-seq method. This technique uses CRISPR/Cas9 with specifically designed guide RNAs (gRNAs) to cleave host-derived 16S rRNA genes (from mitochondria/plastids) after the initial PCR, preventing their amplification in the final library. This method reduced rice host sequences from 63.2% to 2.9% in root samples, dramatically increasing bacterial detection sensitivity without taxonomic bias [16].

Always include negative controls. Process blank reagent controls through your entire workflow. Sequence these controls and use bioinformatic tools like the decontam R package to identify and remove contaminant sequences present in both your controls and true samples. This prevents spending money to analyze external contaminants [17].

Problem: Inaccurate Microbial Community Profiling After Host DNA Depletion

Symptoms: Microbial abundance profiles appear skewed compared to unprocessed samples or expected compositions; certain species are unexpectedly diminished.

Root Cause: Some host depletion methods can introduce taxonomic bias by differentially affecting microorganisms with more fragile cell walls or by failing to lyse certain robust microbes [13].

Solutions:

- Choose a depletion method with low bias. Refer to the benchmarking table above. Methods like F_ase (filter-based) were noted for more balanced performance [13].

- Validate with a mock microbial community. During method development, include a sample with a known mixture of microbial cells. After applying your host depletion protocol, sequence this mock community to check if the relative abundances of the known members have been preserved [13].

- Be aware of method-specific biases. The aforementioned 2025 study found that some commensals and pathogens, including Prevotella spp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, were significantly diminished by certain host depletion methods. Knowing the expected microbiota in your samples can help you select an appropriate method [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Host DNA Depletion

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Example Product | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Depletion Kits | Integrated protocols for selective host cell lysis and DNA degradation. | HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [14], QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit [13] | Validate for your specific sample type (e.g., saliva, BALF); check for taxonomic bias. |

| Chemical Lysis Agents | Selectively disrupt eukaryotic host cell membranes. | Saponin [13] | Concentration must be optimized to balance host lysis with microbial integrity [13]. |

| Enzymes | Degrade free host DNA after cell lysis. | DNase I [12] | Effective on free DNA but cannot access DNA within intact microbial cells. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Identify and remove remaining host reads from sequencing data post-hoc. | Decontam [17], Bowtie2/BWA [12], KneadData [12] | Does not save on sequencing costs but is critical for final data cleanliness. |

Workflow Diagrams

Host DNA Depletion and Cost Control Strategy

Choosing a Host DNA Depletion Method

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the host-to-microbe read ratio, and why is it a critical metric in metagenomic sequencing?

The host-to-microbe read ratio indicates the proportion of sequencing reads that originate from the host organism (e.g., human, cow) compared to those from microbial communities. It is a fundamental metric because a high ratio of host DNA can overwhelm the sequencing capacity, drastically reducing the depth and coverage of microbial reads. This reduction compromises the accuracy and sensitivity of downstream analyses, including taxonomic profiling, functional characterization, and the recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [18] [1]. In essence, a high host read percentage means that sequencing resources and costs are being wasted on non-informative data.

Q2: What is considered an acceptable or good host-to-microbe ratio?

The "acceptable" ratio is highly context-dependent and varies by sample type. However, general patterns exist:

- High-host samples: Samples like bovine vaginal swabs, human saliva, milk, and respiratory tract samples often have over 90% host DNA prior to any depletion efforts [18] [1] [4].

- Low-host samples: Fecal samples typically contain less than 10% host DNA [1]. A successful host depletion method can shift the ratio dramatically. For example, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples, methods have been shown to increase microbial reads from a baseline ratio of 1:5263 (microbe-to-host) by several orders of magnitude [4].

Q3: How does a high host DNA percentage impact the detection of microbial species?

High host DNA levels directly reduce the sensitivity of species detection. As the proportion of host DNA increases, the sequencing depth available for microbial genomes decreases. This leads to a higher number of undetected species, particularly those that are very low or low in abundance [1]. Reducing host DNA allows for a greater number of microbial reads, which improves the detection of rare taxa and increases the confidence of taxonomic assignments.

Q4: Can host depletion methods introduce bias into the microbial community profile?

Yes, different host depletion methods can exhibit taxonomic biases. Methods that involve lysis, filtration, or nuclease digestion can disproportionately affect certain types of microbes based on their cell wall structure (Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative) or physical size. For instance, some methods have been shown to significantly diminish the recovery of specific commensals and pathogens like Prevotella spp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae [4]. It is crucial to validate methods using mock microbial communities to understand and account for these potential biases.

Q5: Beyond read ratios, what other metrics should I monitor to assess data quality after host depletion?

While the host-to-microbe read ratio is primary, other key metrics include:

- Alpha Diversity: The within-sample microbial diversity should be assessed to ensure depletion methods do not artificially reduce diversity [18].

- Mock Community Concordance: When using a spiked mock community, the recovered taxonomic profile should closely match the expected composition [18] [19].

- Functional Coverage: The depth of coverage for microbial genes and pathways should be extensive enough for robust functional profiling [18].

- MAG Quality and Quantity: The number and completeness of recovered Metagenome-Assembled Genomes are key indicators of success for genome-resolved metagenomics [20] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Persistently High Host DNA Ratio After Depletion

If your sequencing data continues to show a high percentage of host reads after applying a depletion protocol, consider the following checklist.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective Method for Sample Type | Review literature for your specific sample matrix (e.g., milk, urine, tissue). | Switch to a method proven effective for your sample. For bovine vaginal samples, Soft-spin + QIAamp is highly effective [18]. For milk, MolYsis has shown success [19]. |

| High Cell-Free DNA | Treat samples with a nuclease (e.g., in a MolYsis or similar protocol) to degrade free-floating DNA before cell lysis. | Incorporate a nuclease digestion step designed to target unprotected host DNA outside of intact microbial cells [4]. |

| Low Microbial Biomass | Quantify bacterial DNA load via qPCR. Be aware that samples with very low microbial biomass are challenging. | Increase the starting sample volume where possible [21]. Consider using Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) post-extraction to increase microbial DNA for sequencing, though this can introduce bias [20]. |

| Inefficient Lysis of Microbial Cells | Check protocol for bead-beating or other mechanical lysis steps, crucial for Gram-positive bacteria. | Ensure your DNA extraction protocol includes a robust mechanical lysis step to break open a wide range of microbial cell types [19]. |

Problem: Depletion Method Introduces Significant Microbial Bias

If your post-depletion data shows a skewed microbial community that does not match expected profiles (e.g., from a mock community), follow this guide.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Method-Related Taxon Loss | Process a defined mock community alongside your samples and compare the results to the expected composition. | If a specific method consistently under-recovers certain taxa (e.g., Gram-positives), consider an alternative method. The QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit has been noted for good recovery of Gram-positive bacteria [18]. |

| Overly Harsh Lysis or Filtration | If using a filtration-based method (e.g., F_ase), large or filamentous microbes may be lost. | For filtration methods, optimize the pore size or omit this step if those microbial groups are of interest [4]. |

| Carry-Over Contamination | Include negative controls (e.g., blank extraction controls) throughout the process. | Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., Decontam [21]) to identify and remove contaminating sequences derived from reagents or the kit itself. Always run and sequence negative controls. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Host Depletion Methods

Below are detailed methodologies for some of the most commonly cited and effective host depletion techniques as referenced in the literature.

Protocol 1: Soft-Spin Centrifugation & QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit

This combination was identified as the most effective for bovine vaginal samples for reducing host genomic content [18].

Workflow Diagram: Soft-Spin & QIAamp Depletion

Detailed Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend the vaginal swab in an appropriate buffer.

- Soft-Spin Centrifugation: Subject the sample suspension to a slow-speed centrifugation step (e.g., 100-500 x g for 5-10 minutes). This pellets large host cells and debris while leaving most microbial cells in suspension.

- Supernatant Transfer: Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new tube. This supernatant is now enriched with microbial cells.

- Nuclease Treatment (QIAamp Kit): Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit. This involves treating the sample with an enzyme to digest free-floating host DNA that is not protected within a microbial cell wall.

- Microbial DNA Extraction: Proceed with the kit's protocol for the lysis of microbial cells and subsequent binding, washing, and elution of the microbial DNA.

- DNA Quantification and Quality Control: Quantify the DNA using a fluorometric method and check for the presence of microbial DNA via 16S rRNA gene PCR or qPCR.

Protocol 2: Saponin Lysis and Nuclease Digestion (S_ase)

This pre-extraction method demonstrated one of the highest host DNA removal efficiencies in respiratory samples [4].

Workflow Diagram: Saponin Lysis Depletion

Detailed Steps:

- Saponin Treatment: To the sample, add a low concentration of saponin (e.g., 0.025% optimized in [4]) to lyse host cells by disrupting their membranes. Incubate for a specified time at room temperature.

- Nuclease Digestion: Add a potent nuclease enzyme (e.g., Benzonase) to the lysate. This enzyme will digest the host DNA that has been released from the lysed host cells. Intact microbial cells protect their DNA from digestion. Incubate according to the enzyme's specifications.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Heat-inactivate the nuclease or use a chelating agent (like EDTA) to stop the reaction.

- Microbial Pellet Collection: Centrifuge the sample at high speed (e.g., 10,000 x g for 10 minutes) to pellet the intact microbial cells. Carefully discard the supernatant containing the digested host DNA.

- DNA Extraction: Proceed with a standard DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro) on the microbial pellet to isolate the microbial DNA.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key commercial kits and reagents commonly used and evaluated in host depletion studies.

| Kit / Reagent Name | Type (Pre/Post Extraction) | Primary Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MolYsis Complete5 [19] [21] | Pre-extraction | Nuclease digestion of free DNA, followed by microbial cell lysis and DNA capture. | Effective for milk microbiome; preserves microbial DNA while removing host background. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit [18] [4] [21] | Pre-extraction | Selective lysis of host cells and nuclease digestion, followed by microbial DNA extraction. | Shows balanced performance and good recovery of Gram-positive bacteria. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [4] [21] | Pre-extraction | Proprietary method to remove host cells and DNA. | Reported to have high host DNA removal efficiency, but may have variable bacterial retention. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit [18] [19] | Post-extraction | Magnetic bead-based capture of methylated host DNA, leaving microbial DNA in supernatant. | Can be combined with other kits; performance varies by sample type (less effective in respiratory samples [4]). |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) [21] | Pre-treatment | Photo-activatable dye that penetrates compromised (host) cells and cross-links DNA, making it unamplifiable. | Can be used to target free DNA and dead host cells; requires light exposure setup. |

Host DNA Depletion Techniques: From Laboratory Bench to Bioinformatics

In metagenomic sequencing research, the overwhelming abundance of host DNA in samples like blood and respiratory fluids presents a significant challenge. It consumes sequencing resources and obscures the detection of microbial pathogens. Physical separation methods, including filtration and centrifugation, are critical first-line techniques for depleting host nucleic acids and enriching microbial content, thereby enhancing the sensitivity and diagnostic yield of downstream analyses.

Troubleshooting Guides

Centrifuge Operational Issues

Problem: Excessive Vibration During Operation

- Causes: Unbalanced load due to uneven sample distribution; damaged or misaligned rotor; worn-out bearings; uneven placement on the surface [22] [23] [24].

- Solutions:

- Ensure samples are distributed evenly by weight across the rotor. Use balance tubes if you have an odd number of samples [23] [25].

- Inspect the rotor for cracks, damage, or signs of metal fatigue. Replace damaged rotors immediately [23] [24].

- Verify that the centrifuge is placed on a level, stable surface [23].

- Check for and remove any foreign objects or debris from the rotor chamber [22] [23].

Problem: Failure to Start or Power Issues

- Causes: Disconnected or faulty power cord; blown fuse or tripped circuit breaker; faulty power switch; internal electrical faults [22] [23] [25].

- Solutions:

- Verify the power cord is securely connected to the instrument and the outlet [22] [23].

- Test the power outlet with another device to confirm it is functional [22] [23].

- Check and replace any blown fuses or reset tripped circuit breakers [22] [23].

- If the issue persists, contact a service technician for internal inspection [22] [25].

Problem: Lid or Door Will Not Close

- Causes: Obstructions from debris or misplaced samples in the door seal; misaligned or damaged door latch; worn or deformed sealing gasket [22] [23] [25].

- Solutions:

Problem: Overheating

- Causes: Blocked ventilation grilles; failed cooling system or fan; continuous use without adequate cooldown intervals [23] [25] [24].

- Solutions:

- Turn off the centrifuge and allow it to cool down completely before inspecting [25].

- Clean vents and fans to remove any dust or obstructions [23] [25].

- Ensure the centrifuge is operated with recommended rest periods between long cycles [23] [24].

- If the problem continues, have the cooling system inspected by a technician [23].

Filtration Workflow Issues

Problem: Slow Filtration Flow Rate

- Causes: Filter membrane clogging, especially from viscous samples or high cellular debris; incorrect pore size selection; excessive pressure application.

- Solutions:

- Pre-process viscous samples (e.g., sputum) with a gentle centrifugation or dilution step to remove coarse debris.

- Ensure the filter pore size is appropriate for the application. For host cell depletion, pore sizes that allow microbes to pass while retaining human cells are key [26].

- Avoid applying excessive pressure, which can force debris to clog the membrane. Use gentle, consistent pressure.

Problem: Low Microbial Recovery Post-Filtration

- Causes: Microbes adhering to the filter membrane; excessive washing; lysis of delicate microbial cells (e.g., some Gram-negative bacteria) due to harsh handling.

- Solutions:

- Incorporate a controlled back-flushing step if the filter design allows it.

- Optimize wash buffer volume and composition to minimize microbial loss.

- Validate the filtration process with spiked control samples to ensure it preserves the viability and integrity of target pathogens [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is host DNA depletion critical in metagenomic sequencing for sepsis diagnosis? Host DNA can constitute over 99.9% of the genetic material in a blood sample, consuming the vast majority of sequencing reads and dramatically reducing the sensitivity for detecting pathogenic microbes. Effective host DNA depletion enriches microbial signals, enabling faster and more accurate pathogen identification, which is crucial for timely treatment of sepsis [27] [4].

Q2: What are the key advantages of novel filtration technologies like the ZISC-based filter over traditional methods? Novel filters like the ZISC-based device offer highly selective physical separation. They are designed to bind and retain host leukocytes with high efficiency (>99% removal) while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through unimpeded. This method is less labor-intensive than many other techniques, better preserves microbial composition, and significantly enriches microbial DNA for sequencing, leading to a tenfold or greater increase in microbial reads [27] [26].

Q3: My centrifuge is making a grinding noise. What should I do? Immediately stop the run. Grinding noises often indicate serious mechanical issues such as worn bearings, loose components, or debris in the rotor chamber. Do not attempt to restart the centrifuge. Contact a qualified service technician for inspection and repair [23] [25] [24].

Q4: How do I choose between centrifugation and filtration for my sample type? The choice depends on your sample and goal.

- Centrifugation-based methods (e.g., differential centrifugation) are versatile and good for initial separation of blood components but may require additional steps for high purity [26].

- Filtration is excellent for selectively removing intact host cells based on size and is highly efficient for liquids like blood or BALF [27] [26]. Consider a combined approach: an initial low-speed centrifugation to remove heavy debris followed by a specific filtration step for host cell depletion.

Experimental Protocols for Host DNA Depletion

Protocol 1: ZISC-Based Filtration for Blood Samples

This protocol details the use of a novel Zwitterionic Interface Ultra-Self-assemble Coating (ZISC)-based filtration device for depleting white blood cells from whole blood prior to microbial DNA extraction [27].

- Objective: To efficiently remove host white blood cells, thereby reducing host DNA background and enriching for microbial pathogens in blood samples for metagenomic sequencing.

Principle: The ZISC-coated filter selectively binds and retains host leukocytes and other nucleated cells while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through due to surface charge properties and pore size [27] [26].

Materials:

- ZISC-based fractionation filter (e.g., Devin from Micronbrane)

- Fresh whole blood sample (3-13 mL volume)

- Syringe

- 15 mL Falcon tube

- Low-speed centrifuge

- High-speed centrifuge

- Microbial DNA extraction kit

Procedure:

- Transfer approximately 4 mL of fresh whole blood into a syringe.

- Securely connect the syringe to the ZISC-based filter.

- Gently depress the syringe plunger to push the blood sample through the filter into a 15 mL Falcon tube.

- Centrifuge the filtered blood at low speed (e.g., 400g for 15 minutes) to separate plasma.

- Transfer the plasma to a new tube and perform high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 16,000g) to pellet microbial cells.

- Proceed with DNA extraction from the pellet using a specialized microbial DNA enrichment kit [27].

Protocol 2: Pre-extraction Host Depletion for Respiratory Samples

This protocol compares several methods, including saponin lysis and nuclease digestion (S_ase), for removing host DNA from frozen respiratory samples [4].

- Objective: To benchmark and apply host depletion methods to increase microbial sequencing reads from high-host-content respiratory samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF).

Principle: Saponin lyses human cells without a rigid cell wall, and subsequent nuclease digestion degrades the released host DNA, leaving intact microbial cells for DNA extraction [4].

Materials:

- Respiratory sample (BALF, sputum, or oropharyngeal swab)

- Saponin solution

- Nuclease enzyme (e.g., Benzonase)

- Nuclease reaction buffer

- Centrifuge

- DNA extraction kit

Procedure:

- Aliquot the respiratory sample.

- Add saponin to a final concentration of 0.025% and incubate to lyse human cells.

- Add nuclease enzyme and its corresponding buffer to digest released host DNA.

- Inactivate the nuclease as per the manufacturer's instructions.

- Centrifuge the sample to pellet the intact microbial cells.

- Discard the supernatant and proceed with DNA extraction from the pellet [4].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Methods

| Method | Principle | Reported Host DNA Reduction | Key Advantages | Reported Microbial Read Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZISC-based Filtration [27] | Physical retention of host cells via surface coating | >99% WBC removal | Preserves microbial composition; less labor-intensive; suitable for gDNA-based mNGS | >10-fold increase in RPM vs. unfiltered |

| Human Cell-Specific Filtration Membrane [26] | Electrostatic attraction to leukocytes | >98% reduction in host DNA | Increases pathogen concentration; streamlines pre-treatment | 6- to 8-fold boost in pathogen reads |

| Saponin Lysis + Nuclease (S_ase) [4] | Lysis of human cells + DNA digestion | High efficiency (1.1‱ host DNA remaining in BALF) | High host removal efficiency | 55.8-fold increase in microbial reads in BALF |

| Commercial Kit (HostZERO) [4] | Not specified in detail | High efficiency (0.9‱ host DNA remaining in BALF) | Effective host removal for various sample types | 100.3-fold increase in microbial reads in BALF |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Physical Separation Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Immediate Action | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive Vibration | Unbalanced load; damaged rotor [22] [23] | Stop the run immediately. Check and redistribute samples [25] | Always balance tubes by mass; regularly inspect and service the rotor [24] |

| Slow Filtration | Membrane clogging | Do not apply excessive force. Pre-clear sample if viscous. | Choose the appropriate pore size; pre-filter or centrifuge sample first. |

| Poor Host Depletion | Inefficient method for sample type; incorrect protocol | Verify protocol steps and sample volume. | Validate method with spiked controls; use methods proven for your sample type (e.g., filtration for blood) [27]. |

| Low Microbial Yield | Harsh processing lysing microbes; target adhesion to filter [4] | Use gentler handling techniques. | Optimize buffer conditions; include a validation step with a control organism [27]. |

Workflow Visualization

Host DNA Depletion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| ZISC-based Filtration Device | A novel filter for selectively depleting host white blood cells from whole blood with high efficiency, significantly improving microbial DNA recovery for mNGS [27]. |

| Human Cell-Specific Filtration Membrane | A filter designed with surface charge properties to electrostatically attract and capture leukocytes, depleting host DNA from clinical samples [26]. |

| Saponin | A detergent used in pre-extraction methods to selectively lyse mammalian cells without a rigid cell wall, releasing host DNA for subsequent degradation [4]. |

| Nuclease Enzyme (e.g., Benzonase) | Digests free DNA (such as host DNA released after lysis) in pre-extraction protocols, reducing host background [4] [28]. |

| Microbial DNA Enrichment/Extraction Kit | Specialized kits optimized for extracting DNA from microbial cells after host depletion, often providing higher yields and purity for challenging samples [27] [29]. |

| Reference Microbial Community (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS) | Defined mixes of microorganisms with known genome equivalents, used as spike-in controls to validate the efficiency and sensitivity of the host depletion and sequencing workflow [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my microbial DNA yield low after saponin-based host DNA depletion?

A significant reduction in total DNA yield is expected after host depletion, as the procedure is designed to remove host nucleic acids. However, a drastic loss of microbial DNA indicates a problem.

- Potential Cause: Saponin Concentration is Too High. Excessive saponin can lyse not only host cells but also specific microbial cells, particularly Gram-negative bacteria, leading to their loss during subsequent DNase digestion [30].

- Solution: Titrate the saponin concentration. Studies have found that even a low concentration of 0.0125% wt/vol can alter the bacterial profile, and 2.5% wt/vol can drastically reduce Gram-negative bacterial DNA [30]. A more recent study optimized and selected a 0.025% saponin concentration for respiratory samples to balance host depletion with microbial integrity [13].

- Solution: Ensure the correct osmotic shock and washing steps are followed to remove the saponin and DNase completely before proceeding to microbial cell lysis and DNA extraction.

My host DNA depletion was successful, but my microbial community profile seems biased. What happened?

Host DNA depletion methods can sometimes introduce taxonomic biases, distorting the true representation of the microbial community.

- Potential Cause: Differential Lysis of Bacterial Cells. If the chemical lysis step (e.g., with saponin) is too harsh, it may preferentially lyse Gram-negative bacteria because of their thinner cell wall structure compared to Gram-positive bacteria. The released DNA from these lysed bacteria is then vulnerable to nuclease digestion, leading to their under-representation in the final sequencing data [30] [13].

- Solution: Visually inspect your data for a sudden drop in Gram-negative abundance compared to untreated controls. If bias is detected, consider switching to a gentler host depletion method. Physical separation methods or kits designed for minimal bias, such as the MolYsis Complete5 kit, have shown better performance in preserving the original community structure in some sample types like milk [19].

- Solution: Always include a non-depleted control sample (if sample quantity permits) to assess the potential bias introduced by the depletion protocol.

I used a nuclease digestion protocol, but the host DNA removal seems inefficient. Why?

Inefficient host DNA depletion after nuclease treatment usually points to an issue with the accessibility of the host DNA to the enzyme.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete Lysis of Host Cells. The nuclease enzyme can only degrade DNA that has been released from within the host cells. If the lysis step (e.g., with saponin or other detergents) is incomplete, a significant portion of host DNA remains protected inside intact cells [12] [31].

- Solution: Optimize the host cell lysis step. Ensure fresh lysis reagents are used and the incubation time/temperature is sufficient. A two-step lysis protocol involving saponin treatment followed by an osmotic shock with sterile water can significantly improve host cell lysis efficiency [31].

- Solution: Check the activity of your nuclease enzyme. Ensure it is active in the buffer conditions used and that inhibitors from the sample or lysis reagents are not carry over.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key advantages and disadvantages of enzymatic/chemical host DNA depletion methods?

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these approaches:

| Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Potential Biases |

|---|---|---|

| Saponin Lysis + Nuclease | High efficiency for host DNA removal; widely used and studied [31]. | Can introduce taxonomic bias by preferentially depleting Gram-negative bacteria [30] [13]. |

| Methylation-Based Depletion (Post-extraction) | No experimental manipulation of original sample; highly compatible with automated workflows. | Requires a complete host reference genome; cannot remove sequences homologous to the host (e.g., human endogenous retroviruses) [12]. |

| Benzonase Nuclease | Wide range of operating conditions; exceptionally high specificity; cleaves DNA into very short fragments [31]. | Efficiency is dependent on complete host cell lysis; may require optimization for different sample matrices. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Lower cost and fewer processing steps than enzymatic methods; no washing steps required [31]. | Requires light exposure for inactivation; efficiency can vary. |

How do I choose the right saponin concentration for my sample type?

The optimal saponin concentration is sample-dependent and must be balanced between host depletion efficiency and microbial DNA preservation.

- General Guidance: Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies on respiratory samples have optimized and selected a 0.025% saponin concentration for an effective and relatively balanced performance [13].

- Titration is Key: Earlier studies used a wide range of concentrations, from 0.0125% to 2.5% wt/vol [30] [13]. It is strongly recommended to perform a concentration gradient test (e.g., 0.025%, 0.1%, and 0.5%) on a representative subset of your samples. Evaluate the host DNA depletion efficiency (via qPCR) and the impact on microbial community structure (via 16S rRNA gene sequencing) to determine the best condition for your specific research goals [13].

My sequencing depth is high, but I still struggle to detect low-abundance microbes. Will host depletion help?

Yes, absolutely. Without host depletion, the vast majority of your sequencing reads (often over 99% in samples like BAL fluid and sputum) are wasted on host DNA, resulting in a very shallow effective sequencing depth for microbes [12] [28].

- Data Insight: In respiratory samples, untreated samples can have 94-99% host reads. Host depletion methods can increase the final microbial reads by 10-fold to over 100-fold, dramatically improving the detection of low-abundance species and increasing functional gene coverage [28] [13].

- Example: One study showed that after host DNA removal, the rate of bacterial gene detection increased by 33.89% in human colon biopsies and by 95.75% in mouse colon tissues [12].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Saponin Lysis and Nuclease Digestion

This is a common wet-lab protocol for pre-extraction host DNA depletion, synthesized from multiple studies [30] [31].

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge liquid samples (e.g., 1 mL) at 6,000 g for 3 minutes. Carefully discard the supernatant. For tissue samples, first homogenize a small piece in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then centrifuge.

- Host Cell Lysis: Resuspend the pellet in PBS containing a pre-optimized concentration of saponin (e.g., 0.025% to 0.5% wt/vol). Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes with gentle mixing.

- Osmotic Shock (Optional but Recommended): Add 350 µL of sterile molecular biology-grade water to the suspension and incubate for 30 seconds to lyse the damaged host cells. Then, add 12 µL of 5 M NaCl to restore isotonicity and protect microbial cells.

- Nuclease Digestion: Centrifuge the sample at 6,000 g for 5 minutes. Remove the supernatant, which contains the released host DNA. Resuspend the pellet in an appropriate buffer and add a potent nuclease (e.g., Benzonase or Turbo DNase). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to degrade the exposed host DNA.

- Washing: Centrifuge the sample and discard the supernatant. Wash the pellet twice with PBS to remove nuclease and digestion products.

- Microbial DNA Extraction: The resulting pellet, now enriched in intact microorganisms, is ready for standard DNA extraction using a commercial kit, typically involving mechanical lysis (bead-beating) to ensure rupture of robust microbial cell walls [30].

Quantitative Data Comparison of Host Depletion Methods

The following table summarizes performance data from recent studies comparing different enzymatic/chemical host depletion methods across various sample types.

| Method | Sample Type | Reported Host DNA Reduction | Reported Increase in Microbial Reads | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saponin (S_ase) | Human BALF & Oropharyngeal Swabs [13] | Most effective; reduced host DNA to 0.9‱ - 1.1‱ of original [13] | 55.8-fold (BALF) [13] | High host depletion but can significantly alter microbial abundance; reduces Gram-negative bacteria [30] [13]. |

| HostZERO (K_zym) | Human BALF & Oropharyngeal Swabs [13] | Highly effective; host DNA below detection in many OP samples [13] | 100.3-fold (BALF) [13] | Showed best performance in increasing microbial reads for BALF [13]. |

| QIAamp Microbiome Kit | Human BALF & Oropharyngeal Swabs [13]; Nasal Swabs, Sputum [28] | 73.6% decrease (Nasal) [28] | 55.3-fold (BALF), 13-fold (Nasal), 25-fold (Sputum) [28] [13] | Good host depletion with high bacterial retention rate in OP samples [13]. |

| MolYsis Complete5 | Human and Bovine Milk [19] | Significantly improved microbial read percentage [19] | Microbial reads: 38.31% (average) vs. 8.54% in untreated [19] | Minimal impact on community structure; no significant biases introduced for milk samples [19]. |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function in Host Depletion | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Saponin (from Quillaja Saponaria) | Detergent that selectively lyses eukaryotic (host) cell membranes by complexing with cholesterol [30] [31]. | Concentration is critical; must be titrated for each sample type to avoid lysing Gram-negative bacteria [30] [13]. |

| Benzonase Nuclease | Potent endonuclease that degrades all forms of DNA and RNA (linear, circular, single- and double-stranded). Used to digest host DNA released after lysis [31]. | Preferred for its broad buffer compatibility and ability to reduce nucleic acids to short oligonucleotides [31]. |

| Turbo DNase | A powerful recombinant DNase that rapidly degrades DNA. Used similarly to Benzonase for host DNA digestion [30]. | Effective but requires specific buffer conditions. Heat-inactivation may be required post-digestion [30]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | A DNA intercalating dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised (lysed) cells. Upon light exposure, it cross-links the DNA, making it unamplifiable [31]. | An alternative to enzymatic digestion; fewer processing steps but requires a light-activation step [31]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Qiagen) | Commercial kit that integrates saponin-based host cell lysis with Benzonase digestion for a standardized workflow [28] [13] [31]. | Shows good host depletion efficiency and high bacterial retention in respiratory samples [28] [13]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit (Zymo Research) | A commercial kit designed to remove host DNA prior to extraction, using a proprietary method [28] [13]. | Demonstrated as one of the most effective methods for increasing microbial reads in BALF samples [28] [13]. |

In metagenomic sequencing research, the overwhelming abundance of host DNA in samples derived from tissues, blood, or other clinical materials presents a significant barrier to sensitive microbial detection. Effective host DNA depletion is crucial for improving the sequencing depth of microbial genomes and achieving accurate pathogen identification. This technical support center provides a comparative analysis and troubleshooting guide for four commercial host DNA depletion kits: the QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit, the HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit, the MolYsis MolYsis Basic kit, and the NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit. The information is framed within the broader thesis of reducing host DNA contamination to enhance the quality and reliability of metagenomic data.

Kit Comparison and Performance Data

The selection of an appropriate host depletion method depends on your sample type and experimental goals. The following table summarizes core characteristics and performance metrics of the four kits, compiled from recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Host DNA Depletion Kits

| Kit Name | Core Technology (Method Category) | Recommended Sample Types | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit [32] [21] | Selective lysis of human cells and degradation of released DNA (Pre-extraction) | Human intestinal tissue [32], Urine [21], Respiratory samples [4] | Effective for intestinal tissue (28% bacterial reads vs. <1% in control) [32]. In urine, yielded greatest microbial diversity and effective host DNA depletion [21]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [32] [4] [21] | Selective lysis of host cells (Pre-extraction) | Human intestinal tissue [32], Respiratory samples (BALF and oropharyngeal swabs) [4], Urine [21] | Most effective in increasing microbial reads in BALF (2.66% of total reads, 100.3-fold increase) [4]. Performance varies by sample type. |

| MolYsis MolYsis Basic Kit [33] | Selective lysis of host cells and DNase degradation (Pre-extraction) | Prosthetic joint sonicate fluid [33], Respiratory samples [4] | Achieved 76 to 9580-fold enrichment of bacterial DNA in joint fluid samples [33]. Effective for low microbial burden clinical samples [33]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit [32] [33] [21] | Enrichment of microbial DNA by binding CpG-methylated host DNA (Post-extraction) | Human intestinal tissue [32], Prosthetic joint sonicate fluid [33], Urine [21] | Effective for intestinal tissue (24% bacterial reads) [32]. Showed 6 to 85-fold enrichment in joint fluid [33]. Less effective for respiratory samples [4]. |

Table 2: Summary of Kit Performance in Different Sample Types from Recent Studies

| Sample Type | Best Performing Kit(s) | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Intestinal Tissue | QIAamp DNA Microbiome, NEBNext | Both kits efficiently reduced host DNA, resulting in 28% and 24% bacterial sequences, respectively, compared to <1% in controls. | [32] |

| Respiratory Samples (BALF) | HostZERO, Saponin Lysis + Nuclease (S_ase) | HostZERO showed the highest microbial read proportion (2.66%); S_ase had the highest host DNA removal efficiency. | [4] |

| Urine (Canine Model) | QIAamp DNA Microbiome | Yielded the greatest microbial diversity in sequencing data and maximized metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) recovery. | [21] |

| Prosthetic Joint Sonicate Fluid | MolYsis Basic | Achieved dramatically higher enrichment (481-9580 fold) compared to the NEBNext kit (13-85 fold). | [33] |

Experimental Protocols from Cited Studies

This protocol is derived from a study that benchmarked kits for shotgun metagenomic sequencing of human intestinal biopsies.

- Sample Preparation: Human intestinal tissue samples are collected and stored at -80°C. Tissue is minced into small pieces using a sterile scalpel.

- Host DNA Depletion: The chosen kit (QIAamp DNA Microbiome, HostZERO, MolYsis, or NEBNext) is used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The study noted that additional optimization steps, such as the use of detergents and bead-beating, can improve the efficacy of some protocols.

- DNA Extraction: Following host depletion, total DNA is extracted using a standard method or the corresponding kit's extraction steps.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Shotgun metagenomic libraries are prepared and sequenced on platforms such as Illumina or Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). The study also evaluated the software-based enrichment method "adaptive sampling" (AS) available on ONT platforms.

- Data Analysis: Sequencing reads are analyzed bioinformatically to determine the percentage of bacterial reads, microbial community composition, and assembly metrics like contig completeness.

This protocol outlines methods for host depletion from low-biomass urine samples.

- Sample Collection and Processing: Midstream urine is collected and stored at -80°C. For analysis, a minimum volume of 3.0 mL is recommended for consistent profiling. Samples are centrifuged at 4°C and 20,000 × g for 30 minutes. The supernatant is discarded, and the pellet is retained.

- Host Depletion and DNA Extraction: The pellet is subjected to DNA extraction using one of the tested kits with host depletion (QIAamp DNA Microbiome, MolYsis, NEBNext, or HostZERO). A kit without host depletion (QIAamp BiOstic Bacteremia) is used as a control. The protocol includes bead-beating for mechanical lysis.

- Inhibitor Removal and Purification: Samples are treated with an inhibitor removal solution and processed through a silica membrane for DNA purification.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Extracted DNA undergoes both 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Data is processed to assess microbial diversity, host DNA depletion efficiency, and to reconstruct Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs).

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues with Host DNA Depletion Kits

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Microbial DNA Yield | Incomplete microbial cell lysis, especially from tough gram-positive bacteria. | Incorporate a bead-beating step during lysis to ensure thorough disruption of all microbial cell walls [32] [21]. |

| Excessive loss of microbial DNA during purification steps. | Avoid over-drying of silica membranes or beads during wash steps. Ensure accurate pipetting to prevent sample loss [34]. | |

| High Residual Host DNA | Sample input exceeds kit's recommended capacity. | Ensure you are not overloading the system; use the recommended amount of starting material [35]. |

| Inefficient depletion due to sample type. | Consider that post-extraction methods (e.g., NEBNext) may be less effective for some sample types like respiratory fluids [4]. A pre-extraction method (e.g., MolYsis, QIAamp) may be more suitable. | |

| Inhibition in Downstream PCR/NGS | Carryover of purification reagents or salts. | Perform the recommended post-enrichment clean-up steps, such as using Agencourt Ampure XP beads, to remove binding buffer reagents [33]. Ensure wash buffers are fresh and used in correct volumes [36]. |

| Skewed Microbial Community Composition | Method-induced bias; some depletion methods can selectively lyse certain bacteria or cause unequal DNA loss [4]. | Use a method known for minimal bias for your sample type. For instance, one benchmarking study found the F_ase (filtering + nuclease) method to have the most balanced performance in respiratory samples [4]. Always include a mock microbial community in initial experiments to validate your chosen protocol. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Should I choose a pre-extraction or post-extraction host depletion method? The choice depends on your sample and goals. Pre-extraction methods (QIAamp, HostZERO, MolYsis) physically remove or degrade host cells and DNA before microbial DNA is extracted. They are generally very effective but can sometimes introduce bias or damage fragile microbes [4]. Post-extraction methods (NEBNext) work on purified DNA and are easier to implement but may be less effective in samples with extremely high host DNA content [4] [33].

Q2: Can host depletion methods affect the representation of the true microbial community? Yes, taxonomic bias is a recognized challenge. Studies have shown that some methods can significantly diminish the recovery of specific commensals and pathogens, such as Prevotella spp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae [4]. It is critical to test methods with mock communities or validate findings with complementary techniques.

Q3: For a new sample type not listed here, how should I proceed? Conduct a pilot experiment. Compare several kits side-by-side using your specific sample type. Include a no-depletion control and use metrics like the percentage of microbial reads, species richness, and the fidelity of a known microbial community (if available) to evaluate performance [4] [21].

Q4: My sample has very low microbial biomass (e.g., urine). What special considerations are needed? Low-biomass samples are highly susceptible to contamination and significant data loss from host DNA. Use a kit that effectively deplets host DNA without introducing significant microbial DNA loss. The QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit has shown promise in urine samples [21]. Always process negative controls (no-template blanks) in parallel to identify and bioinformatically subtract contaminating sequences [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Host DNA Depletion Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Agencourt Ampure XP Beads [33] | SPRI (Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization) beads used for post-enrichment DNA clean-up to remove enzymes, salts, and short fragments that can interfere with sequencing. |

| Proteinase K [35] | A broad-spectrum serine protease used to digest proteins and inactivate nucleases that could degrade DNA during the lysis step of many extraction protocols. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards [27] [21] | Defined mock microbial communities spiked into samples as an internal control to evaluate the efficacy, bias, and sensitivity of the host depletion and sequencing workflow. |

| DNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater) [35] | Used to preserve tissue and other samples immediately after collection, preventing degradation of DNA by nucleases present in tissues like intestine and pancreas. |

| Bead Beating Lysing Matrix [21] | Microbeads used in conjunction with a homogenizer to mechanically disrupt tough microbial cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, fungi), ensuring unbiased DNA extraction. |

Workflow Diagrams for Host DNA Depletion

Pre-extraction vs. Post-extraction Host Depletion

Decision Workflow for Kit Selection

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Kneaddata completes its run but shows an error: "Error, fewer reads in file specified with -2 than in file specified with -1". What is wrong?

This error indicates that your two paired-end input files are out of sync, meaning the R1 and R2 files no longer have their reads in the same order. This leads to discordant alignments during the decontamination step.

- Cause: This often happens if the input FASTQ files were trimmed or processed independently, corrupting the paired relationship.

- Solution: Always process paired-end reads together. If the original files are unavailable, you can attempt to repair the files using tools like

repair.shfrom the BBMap suite to remove singleton reads and re-synchronize the pairs [37].

2. I ran Kneaddata on my non-human metagenomic data, but the decontaminated output has zero reads. What could be the cause?

A zero-read output suggests that all reads were classified as contaminants and removed.

- Cause: A common issue, especially with non-standard host genomes (e.g., giant panda), is the format of sequence identifiers (seq IDs) in your FASTQ files. If the seq IDs contain spaces, it can interfere with Bowtie2's internal sorting and matching of read pairs [38].

- Solution: Check the headers in your FASTQ files using

zcat Sample_R1.fastq.gz | head -n 4. If spaces are present, you may need to reformat the sequence identifiers. The Kneaddata utilities include a function for this, which can be activated by ensuring your files are properly formatted [38].

3. My Kneaddata run fails with only the message "Killed" in the log. How do I resolve this?

The "Killed" message almost always indicates that the operating system terminated the process due to insufficient memory.

- Cause: The "reordering" step in Kneaddata, which ensures read pairs are in the same order, is particularly memory-intensive. This is exacerbated with large files from modern sequencers like NovaSeq [39].

- Solution:

- Increase Memory: Use a machine with more RAM (e.g., 32 GB or more for large datasets).

- Monitor Resources: Use tools like

htopto monitor memory usage during execution. - Adjust Parameters: Reducing the number of parallel threads (

-t) might lower memory pressure [39].

4. How stringent is Kneaddata's filtering with Bowtie2, and can I make it more strict?

By default, Kneaddata uses Bowtie2's --un-conc option, which outputs read pairs where one or both reads fail to align to the reference database. This means a pair is kept if at least one read is unmapped [40].

- Current Behavior: A read pair is discarded only if both R1 and R2 align to the host genome.

- Desired Strict Behavior: To keep only pairs where both reads fail to align.

- Solution: Kneaddata does not have a built-in option for this stricter filtering. To achieve it, you would need to run Bowtie2 and SAMtools separately from the Kneaddata pipeline. A workflow for this is provided in the Experimental Protocols section [40].

5. Besides Kneaddata, what is a reliable standalone method for host read removal using Bowtie2 and SAMtools?

A robust two-step method provides greater control over which reads are filtered.

- Step 1: Alignment. Map reads against the host genome, keeping all aligned and unaligned reads.

- Step 2: Filtering. Use SAMtools to extract only the pairs where both reads are unmapped.

The

-f 12flag specifically extracts reads that are unmapped and whose mate is also unmapped [41] [42]. - Step 3: Convert to FASTQ. Finally, convert the filtered BAM file back to paired FASTQ files.

bash samtools sort -n -m 5G -@ 2 SAMPLE_bothReadsUnmapped.bam -o SAMPLE_bothReadsUnmapped_sorted.bam samtools fastq -@ 8 SAMPLE_bothReadsUnmapped_sorted.bam \ -1 SAMPLE_host_removed_R1.fastq.gz \ -2 SAMPLE_host_removed_R2.fastq.gz[41]

Experimental Protocols and Performance

Comparative Evaluation of Host DNA Depletion Methods

The following table summarizes key findings from a study that evaluated different methods for depleting host DNA in bovine and human milk microbiome samples, which are challenging due to low microbial biomass and high host DNA content [19].

Table 1: Efficiency of Host DNA Depletion Methods in Milk Microbiome Samples

| Method | Description | Average Microbial Reads (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| MolYsis complete5 | Commercial kit for host cell lysis and DNA degradation | 38.31% (Range: 2.01 - 93.12%) | Significantly higher microbial read percentage; no significant biases introduced. |

| NEBNext Microbiome Enrichment Kit | Enzymatic enrichment of microbial DNA | 12.45% (Range: 1.03 - 41.63%) | Moderate improvement over standard extraction. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (Standard) | Standard DNA extraction without specific host depletion | 8.54% (Range: 1.22 - 30.28%) | Serves as a baseline; results in inefficient sequencing of the microbiome. |

Optimized Wet-Lab Protocol for Host and Extracellular DNA Depletion

For complex clinical samples like sputum, a combination of physical and enzymatic methods can effectively deplete both host cellular and extracellular DNA (eDNA). The following workflow, based on a method tested on cystic fibrosis sputum, maximizes the yield of microbial DNA from viable cells [43].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Depleting Host and Extracellular DNA.

This protocol enhances microbial sequencing depth by selectively removing human and eDNA, which allows for better detection of low-abundance taxa and coverage of functional genes [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Databases

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Databases for Host Sequence Removal

| Item | Type | Function in Host Removal |

|---|---|---|

| Bowtie2 | Software | An alignment tool used to map sequencing reads against a host reference genome to identify and separate contaminating reads [44] [45]. |

| Kneaddata | Pipeline | An integrated quality control pipeline that uses Trimmomatic for adapter/quality trimming and Bowtie2 for decontamination against one or more reference databases [44] [45]. |

| BMTagger | Software | An alternative to Bowtie2 for decontamination, designed to filter out human reads from metagenomic datasets. It may require more memory (≥8 GB) [44] [45]. |

| Human Genome Database (hg38) | Reference Database | A pre-formatted Bowtie2 index of the human genome. Used as a reference to identify and remove human-derived sequences from metagenomic data [44] [41]. |