Strategies for Minimizing PCR Amplification Bias in 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

PCR amplification is an integral but problematic step in 16S rRNA gene sequencing, introducing significant bias that distorts microbial community profiles and threatens the validity of scientific conclusions.

Strategies for Minimizing PCR Amplification Bias in 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

PCR amplification is an integral but problematic step in 16S rRNA gene sequencing, introducing significant bias that distorts microbial community profiles and threatens the validity of scientific conclusions. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, quantify, and mitigate these biases. Covering foundational concepts through advanced validation techniques, we detail how factors including primer selection, PCR conditions, enzyme choice, and GC content affect amplification efficiency. We present optimized wet-lab protocols, computational correction models, and rigorous validation strategies using mock communities to ensure accurate representation of microbial abundances in diverse research and clinical applications.

Understanding the Sources and Impact of PCR Bias in 16S rRNA Studies

In 16S rRNA gene sequencing, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification is a critical step that can systematically distort the representation of microbial communities in your samples. These distortions, collectively known as PCR amplification bias, can be categorized into two primary sources based on their underlying mechanisms. Primer-mismatch bias originates from incomplete complementarity between the primer and template DNA, primarily affecting the initial PCR cycles. In contrast, non-primer-mismatch bias (PCR NPM-bias) arises from factors such as template GC content, amplicon length, and secondary structures, which influence amplification efficiency throughout all PCR cycles. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to designing robust experiments and implementing appropriate corrective strategies for accurate microbial community analysis [1] [2].

Defining the Bias: Mechanisms and Key Differences

Primer-Mismatch Bias

This form of bias occurs when sequences in the primer binding sites of the template DNA are not perfectly complementary to the primers used in the amplification reaction.

- Mechanism: A mismatch, particularly near the 3' end of the primer, reduces the efficiency with which the DNA polymerase can extend the primer. This leads to preferential amplification of templates with perfectly matching sequences.

- Phase of PCR Impacted: This bias is introduced almost exclusively during the first three cycles of PCR. After these initial cycles, the original primer-binding sequence on the template is replaced by a sequence that is perfectly complementary to the primer, effectively eliminating the mismatch in subsequent cycles [1] [2].

- Impact: One study demonstrated that a single mismatch in a universal bacterial primer could lead to an almost exponential increase in preferential amplification as the annealing temperature was raised from 47°C to 61°C [3]. This can cause the under-representation or complete dropout of specific taxa from your community profile.

Non-Primer-Mismatch Bias (PCR NPM-bias)

This bias stems from the physicochemical properties of the DNA template itself and the kinetics of the PCR process, independent of primer binding.

- Mechanism: Factors such as GC content, secondary structures, and overall template complexity can affect the denaturation and elongation efficiency during each PCR cycle. For example, GC-rich templates are harder to denature, leading to lower amplification efficiency [4].

- Phase of PCR Impacted: This bias operates throughout all cycles of the PCR reaction, from the mid-cycles (e.g., cycles 10-35) all the way to the late stages [1] [5].

- Impact: PCR NPM-bias can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more, significantly misrepresenting the true structure of the community [1]. One investigation found that as few as ten PCR cycles could deplete loci with a GC content >65% to about 1/100th of the mid-GC reference loci [4].

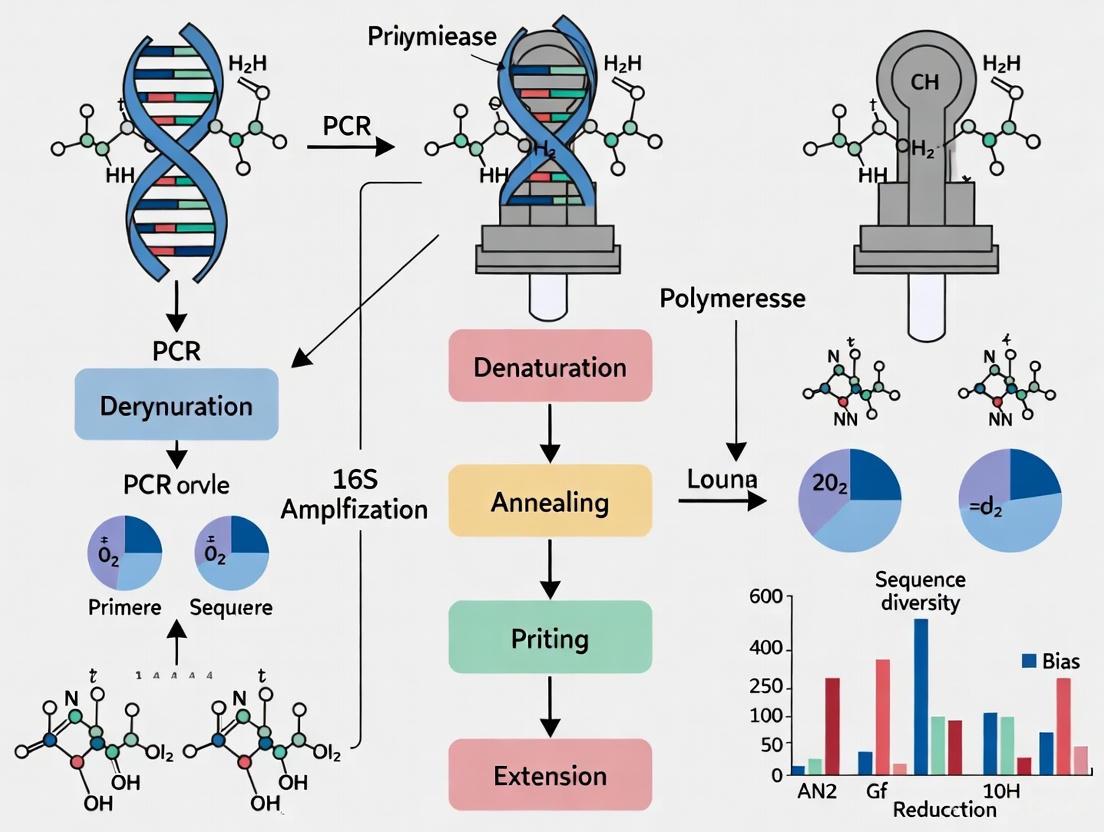

The following diagram illustrates the temporal dynamics and primary causes of these two distinct bias types during a typical PCR process.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of both bias types, highlighting their distinct causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies.

| Feature | Primer-Mismatch Bias | Non-Primer-Mismatch Bias (NPM-Bias) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Incomplete complementarity between primer and template DNA sequence [2] [3]. | Template GC content, secondary structure, and PCR stochasticity [1] [4]. |

| Key Mechanism | Reduced primer annealing and extension efficiency due to mismatches, especially at the 3' end [3]. | Incomplete denaturation of GC-rich templates and differential amplification efficiency per cycle [4]. |

| Phase of PCR | First 3 cycles [1]. | All cycles, with significant effects in mid-to-late cycles (cycles 10-35) [1] [5]. |

| Major Impact | Preferential amplification of perfect-match templates; failure to amplify taxa [2]. | Skewing of relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more [1]. |

| Primary Mitigation | Use of degenerate primers; lower annealing temperature; PEX-PCR method [2] [3]. | Use of PCR enhancers (e.g., betaine); optimized thermocycling; computational correction [1] [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My negative controls are clean, but my low-biomass samples show high variability in rare species. What could be the cause? A: This is a classic sign of PCR stochasticity, a form of NPM-bias. In early PCR cycles, the random amplification of a limited number of starting DNA molecules can dramatically skew representation. This is particularly pronounced in low-biomass samples where template copies are scarce. To mitigate this, you can:

- Increase template input where possible.

- Perform technical replicates to identify and average out stochastic effects.

- Use a mock community as a positive control to quantify this variability [5] [6].

Q2: I am using well-established, "universal" primers, but I suspect I am missing certain archaeal groups. What type of bias is this likely to be? A: This is most likely primer-mismatch bias. Even "universal" primers may have mismatches to specific, often under-represented, taxonomic groups. For example, it was found that adding degeneracy to the 515F primer helped remove biases against Crenarchaeota/Thaumarchaeota [7]. To address this:

- Review the literature for primer updates targeting your missed groups.

- Consider using a primer pool with higher degeneracy.

- Lower the annealing temperature slightly to allow for some mismatch tolerance, though this may reduce specificity [3] [7].

Q3: My sequencing data under-represents GC-rich organisms despite using a validated protocol. How can I confirm and fix this NPM-bias? A: You can confirm this by running a qPCR bias assay on a panel of GC-varied amplicons [4]. To fix it, focus on wet-lab optimizations:

- Add PCR enhancers like betaine (1-2 M) or DMSO to lower strand separation temperatures.

- Optimize thermocycling conditions by extending denaturation times (e.g., from 10 s to 80 s per cycle) to ensure complete denaturation of GC-rich templates.

- Evaluate different polymerase blends known for better performance on complex templates [8] [4].

Experimental Protocol: PEX-PCR for Reducing Primer-Mismatch Bias

The Polymerase-exonuclease (PEX) PCR method is a novel strategy that separates the primer-template and primer-amplicon interactions to minimize biases from degenerate primer pools and primer-template mismatches [2].

Workflow Summary:

- Initial Limited-Cycle PCR: Perform a small number of PCR cycles (e.g., 3-5) using your degenerate primer pool and genomic DNA template.

- Exonuclease Digestion: Treat the product with an exonuclease to degrade the remaining primers from the first PCR. This step can often be performed without a reaction cleanup.

- Second PCR Amplification: Use a fresh, non-degenerate primer set (lacking the original degeneracies) to amplify the products from the first PCR for the remaining cycles.

Key Advantage: This method allows the initial primer binding to occur under low-stringency conditions if needed, reducing the impact of mismatches. The subsequent amplification with uniform primers ensures that all templates are amplified with equal efficiency in the later stages, substantially improving the evenness of sequence recovery from mock communities [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their specific roles in mitigating different types of PCR bias in 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism | Relevant Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Betaine | Reduces melting temperature differences; equalizes amplification efficiency of GC-rich and AT-rich templates by acting as a destabilizer [8] [4]. | Non-Primer-Mismatch (GC Bias) |

| DMSO | Disrupts base pairing, helping to denature secondary structures and lower the melting temperature of DNA [8]. | Non-Primer-Mismatch (GC Bias) |

| PEX-PCR Method | Separates primer-template and primer-amplicon interactions; reduces bias from primer degeneracies and mismatches [2]. | Primer-Mismatch |

| Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix | A premixed mastermix that provides high fidelity and robust performance, reducing manual handling errors and batch effects [6]. | General Protocol Variability |

| AccuPrime Taq HiFi Blend | An alternative polymerase blend shown to amplify sequencing libraries more evenly than some standard enzymes [4]. | Non-Primer-Mismatch |

| Degenerate Primers (e.g., 515F-Y/806R) | Primer pools with added degeneracy to cover sequence variants, improving the detection of specific taxa like Crenarchaeota and SAR11 [7]. | Primer-Mismatch |

Computational Correction of PCR Bias

For biases that cannot be fully eliminated experimentally, computational post-processing offers a solution. A prominent approach involves using log-ratio linear models to correct for PCR NPM-bias [1].

Conceptual Framework: This model builds on the principle that each cycle of PCR amplifies each template with a taxon-specific efficiency. If the true ratio of two taxa prior to PCR is A/B, then after x cycles, the ratio becomes A/B × (EA/EB)x, where E is the per-cycle amplification efficiency.

Implementation: By using calibration data (e.g., from mock communities) or Bayesian modeling techniques applied to sample data, these efficiency ratios can be estimated. The observed sequencing data can then be transformed to estimate the true relative abundances before amplification, thereby correcting for the systematic bias introduced during PCR [1]. This method is particularly powerful because it can mitigate bias even after data collection, though it requires careful statistical implementation.

In 16S rRNA gene sequencing, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification is an integral experimental step for profiling microbial communities. However, PCR is known to introduce multiple forms of bias, which can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of four or more [9]. These biases impede accurate evaluation of community structure and present a substantial source of error in microbiome studies [9] [10]. Among the numerous sources of bias, primer specificity, GC-content, and amplicon length represent three critical and controllable factors. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and methodologies to identify, understand, and mitigate these key sources of amplification bias.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Bias Concepts

Q1: What is PCR amplification bias and why is it a problem in 16S sequencing? PCR amplification bias refers to the non-random, preferential amplification of some bacterial 16S rRNA gene templates over others during the PCR process. This bias is problematic because it distorts the true biological signal, causing the final sequencing data to misrepresent the actual abundance, diversity, and composition of the microbial community in the original sample. This can lead to incorrect conclusions in research and diagnostics [9] [11].

Q2: Are biases consistent and can they be corrected? Yes, a body of research suggests that PCR bias is often reproducible and predictable. Because the bias is partly induced by sequence composition, it is often similar in closely related taxonomic groups. This predictability allows for the development of computational correction factors and experimental calibration methods to mitigate its effects [9] [11].

Primer Specificity

Q3: How does primer specificity contribute to amplification bias? Primer specificity bias occurs due to sequence divergence in the primer binding sites on the 16S rRNA gene. Even single nucleotide mismatches between the primer and the template, especially near the 3' end, can lead to preferential amplification of up to 10-fold [9]. This means taxa with perfect matches to the primers will be overrepresented, while those with mismatches may be undetected or severely underrepresented [9] [10] [11].

Q4: What are the best practices for selecting and designing primers to minimize bias?

- Use Degenerate Primers: Incorporate degenerate bases at variable positions to account for sequence diversity, which can broaden taxonomic coverage and reduce bias [11] [12].

- Optimize for Coverage and Efficiency: Utilize computational tools like mopo16S or Primer-BLAST to design primers that simultaneously maximize coverage (the fraction of bacterial sequences targeted), efficiency (predictable PCR performance), and minimize matching-bias (differences in how many primers bind to each taxon) [12].

- Validate Experimentally: Always test primer pairs on mock communities of known composition to assess their performance and potential biases for your specific sample type [10].

GC-Content

Q5: How does template GC-content cause amplification bias? Templates with very low or very high GC-content amplify less efficiently than those with moderate GC-content. This is because low GC-content sequences form less stable duplexes, while high GC-content sequences can form stable secondary structures that impede polymerase progression, leading to their under-representation in the final sequencing library [11] [12].

Q6: What is the optimal GC-content for PCR primers? For reliable amplification, primers should have a GC-content generally between 40%–60% [12] [13]. A "GC clamp" (one or two G or C bases at the 3' end) can promote stable binding, but avoid more than 3 G/C in the final five bases to prevent non-specific priming [13].

Amplicon Length

Q7: Why does amplicon length matter for amplification bias? Amplicon length influences bias in two primary ways:

- Amplification Efficiency: During PCR, shorter sequences are often amplified preferentially over longer ones. Furthermore, in samples with degraded DNA (e.g., from formalin-fixed tissues or processed foods), longer amplicons may fail to amplify altogether, leading to false negatives [11] [14].

- Viability qPCR (v-qPCR) Specificity: In techniques like v-qPCR that use dyes to distinguish live/dead cells, longer amplicons increase the probability of dye binding and effectively blocking amplification of DNA from dead cells. However, this comes at the cost of overall PCR efficiency [15].

Q8: Is there an optimal amplicon length to minimize bias? The "optimal" length is a trade-off and depends on the application:

- For standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing, shorter amplicons (e.g., single variable regions like V4) can reduce length-dependent bias and are compatible with short-read sequencing. However, longer amplicons (e.g., full-length 16S) can provide superior taxonomic resolution [10] [16].

- For v-qPCR, a range of ~200-400 bp is suggested as a working compromise, providing good live/dead distinction while maintaining reasonable PCR efficiency [15].

- For highly degraded DNA, amplicons of 50-80 bp are crucial for successful detection and to avoid false negatives [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

| Symptom in Data | Potential Cause | Next Steps for Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic under-representation of a specific phylum (e.g., Bacteroidetes). | Primer mismatch due to poor binding site conservation. | Check in silico coverage of your primers against a database like SILVA. Compare with a different primer set. |

| Poor representation of taxa with very high or very low GC genomes. | GC-content bias. | Analyze the GC-content of under-represented taxa. Use PCR additives like DMSO or betaine in optimization. |

| Low library diversity or failure to amplify in samples with degraded DNA. | Amplicon length is too long for the template. | Re-attempt PCR with a shorter amplicon target. Check DNA quality via bioanalyzer. |

| Inconsistent community profiles between technical replicates. | PCR drift due to stochastic early-cycle amplification. | Reduce PCR cycle number and/or pool multiple PCR replicates [6]. |

Guide 2: Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol 1: A Paired Experimental and Computational Approach to Measure PCR NPM-Bias This protocol allows you to measure and correct for non-primer-mismatch (NPM) bias directly from your samples [9].

- Create a Calibration Sample: Pool aliquots of extracted DNA from all study samples.

- Generate Cycle Series: Split the pooled sample and amplify aliquots for different numbers of PCR cycles (e.g., 15, 20, 25, 30 cycles).

- Sequence and Model: Sequence all aliquots and use a log-ratio linear model (e.g., with the

fidoR package) to relate the observed composition to the PCR cycle number. - Apply Correction: The intercept of this model estimates the sample's composition prior to PCR NPM-bias, allowing for computational correction of your study data.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Amplicon Length for v-qPCR This method helps determine the optimal amplicon length for viability qPCR [15].

- Design Multiple Primer Sets: Design several primer sets targeting incrementally increasing amplicon lengths (e.g., from 68 bp to 906 bp) for your target organism.

- Treat with PMA: Split a sample of your bacteria into live and heat-killed portions, treating both with a viability dye (PMA).

- Run qPCR: Perform qPCR on both live and killed samples using all primer sets.

- Calculate ΔCq: For each amplicon length, calculate the difference in quantification cycle (ΔCq) between live and killed cells.

- Identify Optimal Range: Plot ΔCq against amplicon length. The optimal range is where ΔCq is high (good live/dead distinction) while maintaining acceptable PCR efficiency (minimal Cq increase in live samples). This typically falls between 200-400 bp [15].

Table 1: The Trade-off Between Amplicon Length, Live/Dead Distinction, and PCR Efficiency in v-qPCR [15]

| Bacterium | Minimum Amplicon Length (bp) for ~79% of Max ΔCq | ΔCq at Minimum Length | Maximum Amplicon Length (bp) for ~98.5% of Max ΔCq | ΔCq at Maximum Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | 200 - 224 | 16.1 - 16.2 | 355 - 403 | 20.1 - 20.3 |

| P. intermedia | 227 | 18.3 | 414 | 22.9 |

| F. nucleatum | 156 | 12.6 | 278 | 15.7 |

| E. coli | 201 | 14.4 | 380 | 18.0 |

| General Guideline | ~200 bp | Good distinction | ~400 bp | Max distinction, lower efficiency |

Table 2: Impact of Short Amplicons on Detectability in Challenging Samples [14]

| Sample Type | Target | Short Amplicon Result (50-80 bp) | Long Amplicon Result (86-170 bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean Oil | Lectin gene | Detected (Ct = 29) | Detected with higher Ct (Ct = 38) |

| Peanut Oil | Arah gene | Detected (Ct = 31) | No Amplification |

| Rapeseed Oil | CruA gene | Detected (Ct = 34) | No Amplification |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Workflow for measuring and correcting PCR NPM-bias using a calibration experiment.

Diagram 2: Process for determining the optimal amplicon length for a v-qPCR assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Bias Mitigation

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Community Standards | Positive control with known composition to quantify primer bias and bioinformatic pipeline performance. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards (D6300, D6331) [10] [16] |

| Spike-in Controls | Internal standards added to samples to convert relative abundance data to absolute abundance. | ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I (D6320) [16] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces PCR-introduced errors and can improve amplification uniformity of complex mixtures. | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix [6] |

| PCR Additives | Helps ameliorate biases from GC-content and secondary structures. | DMSO, Betaine |

| Viability Dyes (PMA/EMA) | Suppresses amplification of DNA from membrane-compromised (dead) cells in v-qPCR. | Propidium Monoazide (PMA) [15] |

| Primer Design Software | Computationally optimizes primers for coverage, specificity, and efficiency before synthesis. | NCBI Primer-BLAST, mopo16S, DegePrime [12] |

The Impact of PCR Cycle Number on Community Representation and Diversity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does increasing the PCR cycle number impact the sequencing of low microbial biomass samples? Increasing the PCR cycle number is a common strategy to improve sequencing coverage for low microbial biomass samples (e.g., blood, milk, tissue biopsies). While higher cycles (e.g., 35-40) significantly increase the number of usable sequences, they do not necessarily alter core ecological metrics like alpha-diversity or beta-diversity patterns compared to lower cycle numbers (e.g., 25). This allows for the successful profiling of samples that would otherwise yield uninterpretable data due to low coverage [17].

Q2: What is PCR amplification bias and how does it relate to cycle number? PCR amplification bias refers to the distortion of true microbial abundances because different DNA templates are amplified with varying efficiencies. This bias can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more. During mid-to-late stage PCR cycles, this bias becomes increasingly pronounced as templates with higher amplification efficiencies out-compete others, making cycle number a critical parameter to control [9].

Q3: Can I reduce the number of PCR replicates to save on costs and time? Yes, for standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing, evidence suggests that pooling multiple PCR amplifications per sample (a common practice to reduce PCR drift) may not be necessary. Studies have found no significant difference in high-quality read counts, alpha diversity, or beta diversity between libraries prepared from single, duplicate, or triplicate PCR reactions. This can streamline your protocol and reduce reagent use [6].

Q4: What is a major cause of failed 16S rRNA sequencing in human-derived samples? A major issue is off-target amplification of human DNA, particularly when using primers for the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. In human biopsy samples, this can lead to an average of 70% of sequenced reads aligning to the human genome instead of bacterial targets. Switching to optimized primers targeting the V1-V2 region can drastically reduce this problem and improve taxonomic resolution [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Library Yield or No Amplification from Low Biomass Samples

This is a common issue when working with samples containing low bacterial DNA, such as blood, milk, or sterile tissues.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient PCR cycles | For low biomass samples, increase the PCR cycle number to 35 or 40 cycles to enhance detection probability [17]. |

| Inhibitors in DNA template | Re-purify the DNA sample using bead-based or column-based cleanups to remove salts, phenols, or other contaminants [19]. |

| Suboptimal primer selection | If working with human-associated samples, use primers less prone to off-target human DNA amplification (e.g., V1-V2 primers instead of V4) [18]. |

| Inaccurate DNA quantification | Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) rather than UV absorbance for quantifying input DNA, as the latter can overestimate usable concentration [19]. |

Problem: Over-Amplification Artifacts and Bias

Excessive PCR cycling can introduce artifacts and bias, even while improving coverage.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Too many PCR cycles | For high-biomass samples (e.g., stool, soil), limit cycles to 25-30 to minimize over-amplification artifacts and bias. For low-biomass samples, balance the need for coverage with the potential for increased chimeras [17] [20]. |

| High-fidelity polymerase error | Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase and ensure balanced dNTP concentrations to reduce sequencing errors introduced during amplification [21] [22]. |

| Chimera formation | Implement a robust chimera detection and removal step in your bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., using Uchime). Chimera rates can be as high as 8% in raw reads [20]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Impact of PCR Cycle Number

The following table summarizes key findings from a study that directly evaluated the effect of PCR cycle number on 16S rRNA sequencing results from low-biomass samples [17].

| Sample Type | PCR Cycles Tested | Impact on Coverage | Impact on Alpha & Beta Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Milk | 25, 30, 35, 40 | Significantly increased with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

| Murine Pelage | 25, 40 | Significantly increased with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

| Murine Blood | 25, 40 | Significantly increased with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

Detailed Protocol: Mitigating Bias via a Calibration Experiment

This protocol, based on contemporary research, allows for the measurement and correction of PCR bias without relying on mock communities [9].

Objective: To computationally correct for non-primer-mismatch PCR bias (NPM-bias) in microbiota datasets.

Workflow Steps:

- Create a Calibration Sample: Prior to PCR, pool aliquots of extracted DNA from every study sample into a single, representative pooled sample.

- Generate Calibration Curve: Split the pooled sample into several aliquots. Amplify each aliquot for a different number of PCR cycles (e.g., 10, 15, 20, 25, 30), covering a wide range.

- Sequence All Samples: Sequence the calibration aliquots alongside your main study samples, which are all amplified with a standard cycle number.

- Computational Correction: Use a log-ratio linear model (e.g., with the

fidoR package) to analyze the calibration data. The model infers the original sample composition (intercept) and the taxon-specific amplification efficiencies (slope) to correct the bias in the main study data.

Below is a workflow diagram of this calibration experiment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Hot-Start Polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Reduces non-specific amplification and errors during the initial PCR cycles, improving specificity and yield [6] [22]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Provides absolute quantification of bacterial load and initial community ratios without amplification bias, serving as a gold standard for validating NGS data and bias correction models [23]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | A DNA mixture of known bacterial composition. It is essential for validating your entire workflow, quantifying batch effects, and estimating error rates [23] [20]. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits (e.g., AMPure XP) | Used for consistent purification and size-selection of PCR products, effectively removing primer dimers and other unwanted artifacts [17] [6]. |

| Optimized Primer Sets (e.g., for V1-V2) | Primer pairs designed to minimize off-target amplification (e.g., of human host DNA) are crucial for successful sequencing of host-derived samples like biopsies [18]. |

How Genomic GC-Content Correlates with Amplification Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary consequences of GC-content bias in 16S sequencing? GC-content bias leads to non-homogeneous amplification of template DNA, where some sequences are preferentially amplified over others. This results in skewed representation of microbial taxa in your final sequencing data, compromising the accuracy and sensitivity of both alpha and beta diversity analyses. Widely used metrics like Shannon diversity and Weighted-Unifrac are particularly sensitive to this bias [24].

My amplification of a GC-rich region has failed. What should I check first? Your initial troubleshooting should focus on three key areas:

- Polymerase Choice: Standard polymerases often stall at complex secondary structures. Switch to a polymerase specifically engineered for high GC content, such as OneTaq or Q5, which are often supplied with a specialized GC buffer and enhancer [25].

- Reaction Additives: Incorporate additives like DMSO, betaine, or formamide. These work by reducing secondary structure formation (e.g., hairpins) and increasing primer annealing stringency, which helps denature stable GC-rich templates [26] [27].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: Optimize your annealing temperature. A higher temperature can improve specificity and help denature secondary structures. Also, consider using a 2-step PCR protocol or a "slowdown PCR" method with adjusted ramp speeds to improve the amplification of long, GC-rich targets [27].

How can I predict if my target sequence will be difficult to amplify based on its sequence? While overall GC content is a good initial indicator, regionalized GC content is a much more powerful predictor. Research has shown that calculating GC content within a sliding window (e.g., 21 bp) and identifying regions that exceed a threshold (e.g., 61% GC) significantly improves the ability to predict PCR success. Templates with high localized GC regions are far more challenging to amplify than those with evenly distributed GC content [28].

Are there ways to correct for GC bias bioinformatically after sequencing? Yes, bioinformatic normalization approaches can help correct sequencing biases. Tools like FastQC and Picard can first help you identify and quantify the level of GC bias in your data. Subsequent bioinformatic algorithms can then adjust read depth based on local GC content, improving coverage uniformity and the accuracy of downstream analyses like variant calling [29].

GC Content as a Predictor of PCR Efficiency

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings on the relationship between template GC characteristics and PCR amplification success.

| GC Characteristic | Impact on Amplification Efficiency | Experimental Context | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall GC Content >60% | Major challenge; often leads to failed amplification or low yield [25] [26] | Amplification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits (GC=58-65%) [26] | Requires optimized protocols with additives and specialized polymerases. |

| Regionalized GC >61% | Stronger predictor of failure than overall GC content [28] | Amplification of 1,438 human exons [28] | Improved specificity (84.3%) and sensitivity (94.8%) in predicting PCR outcome. |

| Local GC-rich stretches | Forms stable secondary structures (hairpins), blocking polymerase [27] | Amplification of Mycobacterium bovis gene Mb0129 (77.5% GC) [27] | Causes severe drop-off in efficiency; necessitates specialized cycling conditions. |

| Progressive Skewing | A small subset (~2%) of sequences can have efficiencies as low as 80% relative to the mean [30] | Multi-template PCR on 12,000 synthetic DNA sequences [30] | Leads to drastic under-representation after as few as 30 PCR cycles. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating GC-Bias

Protocol 1: Optimized Workflow for GC-Rich Amplicons

This workflow is designed for amplifying difficult, GC-rich targets, such as those encountered in 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Detailed Steps:

- Polymerase and Buffer System: Replace standard Taq polymerase with a high-fidelity enzyme engineered for GC-rich templates, such as Q5 or OneTaq DNA Polymerase. Use the specialized GC buffer and GC enhancer supplied with these systems. The enhancer typically contains a proprietary mix of additives that lower the melting temperature of DNA and disrupt secondary structures [25].

- Additive Optimization: If further optimization is needed, test the addition of 1-10% DMSO or 0.5 M to 2.5 M betaine to the reaction mix. These compounds are known to equalize the melting temperatures of DNA, preventing the formation of secondary structures like hairpins and improving the yield of GC-rich amplicons [26] [27].

- Mg2+ Concentration: Set up a reaction series testing MgCl2 concentrations in 0.5 mM increments from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM. Magnesium is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity, and its optimal concentration can vary significantly for difficult templates [25].

- Thermal Cycling Parameters:

- Annealing Temperature: Perform a temperature gradient PCR to determine the optimal annealing temperature (Ta). A higher Ta (e.g., 5°C higher than the calculated Tm) can significantly improve specificity by preventing non-specific primer binding [25].

- Advanced Cycling: For particularly long (>1 kb) or difficult targets, employ a 2-step PCR protocol that combines annealing and extension at a higher temperature (e.g., 68°C). Using a thermal cycler with adjustable ramp speed and setting it to a slower speed (e.g., 1-2°C/second) can dramatically improve success rates by allowing more time for the polymerase to unwind and replicate highly structured DNA [27].

Protocol 2: Validating Primer Efficiency for Quantitative Analysis

For applications like qPCR, ensuring uniform and high amplification efficiency is critical for accurate quantification. This protocol ensures primers meet strict efficiency standards before use in 16S sequencing studies [31].

Procedure:

- Sequence-Specific Primer Design: For each target gene (e.g., a 16S rRNA hypervariable region), retrieve all homologous sequences. Design primers based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) unique to the target to ensure specificity and avoid co-amplification of closely related sequences.

- Generate a Standard Curve: Using a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10) of your template cDNA, run a qPCR assay for each primer pair.

- Calculate Efficiency and R²: Plot the log of the template concentration against the Ct value for each dilution. Perform linear regression analysis. The slope of the line is used to calculate the amplification efficiency (E) using the formula: ( E = 10^{(-1/slope)} - 1 ). An ideal primer pair will have an efficiency (E) of 100% ± 5% and a correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.9999 [31].

- Validation: Only primer pairs that meet these stringent criteria should be used for subsequent quantitative experiments to ensure that observed abundance differences reflect biology and not technical bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for GC-Rich PCR

| Reagent Category | Example Products | Function in GC-Rich PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, OneTaq DNA Polymerase [25] | Engineered to resist stalling at stable secondary structures; often supplied with proprietary GC buffers. |

| PCR Enhancers/Additives | Betaine, DMSO, Formamide [26] [27] | Disrupt hydrogen bonding, lower DNA melting temperature, and prevent secondary structure formation. |

| GC-Enhanced Master Mixes | OneTaq Hot Start 2X Master Mix with GC Buffer, Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix [25] | Pre-mixed convenience with optimized buffer/enhancer formulations for robust amplification of difficult targets. |

| Magnesium Salts (MgCl₂) | Supplied with polymerase buffers | A critical cofactor; fine-tuning its concentration (1.0-4.0 mM) is essential for polymerase activity and primer annealing in GC-rich contexts [25]. |

FAQ: Understanding and Troubleshooting PCR Bias in 16S Sequencing

What are the primary consequences of PCR amplification bias in my 16S rRNA data?

PCR amplification bias systematically distorts your data in two key ways:

- Skewed Abundance Estimates: The relative proportions of organisms in your data no longer accurately reflect their true ratios in the original sample. This bias can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more [32] [33]. This means a microbe representing 10% of the actual community could appear as either 40% or 2.5% in your results.

- Generation of Spurious OTUs: Bias can create artificial diversity. Chimeric sequences formed during PCR [34] and the differential amplification of intragenomic 16S gene copies [35] can be misinterpreted as unique Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), inflating diversity metrics and leading to false biological discoveries.

Why does my amplicon data show high levels of an archaeon (likeMethanobrevibacter) that doesn't match my biological expectations?

This is a classic sign of amplification bias, often caused by extensive length polymorphisms in the target gene region [36]. In a mixed community, templates with shorter amplicon lengths will amplify more efficiently than longer ones, especially when the sample DNA is fragmented (common in ancient or low-quality samples). If a particular organism's 16S gene is shorter for your chosen primer set, it will be disproportionately over-represented in your final data [36].

My sequencing library yield is low, and my electropherogram shows a sharp peak at ~70-90 bp. What is wrong?

A sharp peak at 70-90 bp is a clear indicator of adapter dimer contamination [19]. This occurs during library preparation due to:

- Inefficient Ligation: Poor ligase performance or suboptimal reaction conditions.

- Adapter-to-Insert Molar Imbalance: An excess of adapters in the reaction promotes adapter-dimer formation.

- Inadequate Purification: Failure to effectively remove these small artifacts after library construction [19]. These dimers consume sequencing resources and can result in low yields of usable data. You should re-optimize your ligation protocol and ensure a thorough cleanup with size selection.

How much can the DNA extraction protocol alone impact my microbial community profiles?

The choice of DNA extraction kit is one of the most significant sources of bias. Studies have shown that using different kits on the same mock community can lead to dramatically different results [37]. One kit might increase the observed proportion of Enterococcus by 50% while suppressing other genera, compared to another kit [37]. The bias introduced by DNA extraction is often much larger than that introduced by sequencing and classification [37].

Quantifying the Impact: Data on Bias Magnitude

The following table summarizes quantitative findings on the magnitude of bias from key studies.

Table 1: Documented Magnitude of PCR and Sample Preparation Biases

| Source of Bias | Observed Impact | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| PCR (NPM-bias) | Skewed abundance estimates by a factor of 4 or more [32]. | Mock bacterial communities and human gut microbiota. |

| DNA Extraction | Error rates from bias of over 85% in some samples; technical variation was less than 5% for most bacteria [37]. | 80 mock communities comprised of seven vaginally-relevant bacterial strains. |

| Template Concentration | A significant impact on sample profile variability; low concentration (0.1-ng) templates showed higher variability [38]. | Soil and fecal DNA extracts sequenced on Illumina MiSeq. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Characterization

Protocol 1: Using Mock Communities to Quantify Total Bias

This protocol allows you to quantify the total bias introduced by your entire sample processing pipeline [37].

- Select Bacterial Strains: Decide on a small subset of bacteria relevant to your study that can be cultured.

- Generate Experimental Design: Create a D-optimal mixture design with prescribed proportions for the mock communities. Include replicate runs to estimate pure error variance.

- Prepare Mock Communities: Grow each isolate to exponential phase and determine cell density. Combine the bacteria in the prescribed proportions to create the mock community samples.

- Process Samples: Subject the mock communities to your standard pipeline: DNA extraction, PCR amplification, sequencing, and taxonomic classification.

- Analyze Data: Compare the observed proportions from sequencing with the known, prescribed proportions from the experimental design. The difference is your total measured bias.

Protocol 2: Paired Modeling to Mitigate PCR NPM-Bias

This approach uses a statistical model to correct for non-primer-mismatch (NPM) PCR bias [32].

- Generate Standard Curves: Create a dilution series of a mock community with known composition. Include this as a standard in every sequencing run.

- Sequence Standards and Samples: Process both the mock community standards and your environmental samples (e.g., human gut microbiota) using the same 16S rRNA gene sequencing protocol.

- Model the Bias: Use the data from the mock standard to fit a log-ratio linear model. This model characterizes the relationship between the true relative abundances (known from the mock) and the observed relative abundances (from sequencing).

- Apply the Correction: Use the fitted model to predict and correct the true microbial relative abundances in your environmental samples based on your observed data [32].

Research Reagent Solutions for Bias Mitigation

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Roles in Managing 16S Sequencing Bias

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Rationale | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Communities | Ground-truthing for quantifying bias introduced by the entire wet-lab workflow [37]. | Defined mixtures of cultured bacterial strains (e.g., 7 vaginally-relevant species) [37]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces PCR errors and chimera formation during amplification. | LongAmp Taq MasterMix (used in full-length 16S protocols) [34]. |

| Emulsion (Micelle) PCR | Physically separates template molecules to prevent chimera formation and PCR competition, enabling absolute quantification [34]. | micPCR protocol for full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification [34]. |

| Full-Length 16S Primers | Provides superior taxonomic resolution compared to short variable regions, helping to resolve species and strains [35] [34]. | Primers 16SV1-V9F and 16SV1-V9R [34]. |

| Internal Calibrator (IC) | Allows for absolute quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies, enabling subtraction of background contaminating DNA [34]. | Synechococcus 16S rRNA gene copies added to each sample [34]. |

| Barcoded Primers | Enables multiplex sequencing of multiple samples, reducing inter-lane sequencing variability [38]. | Unique barcodes for each sample, part of the cDNA-PCR sequencing kit (ONT) [34]. |

Workflow Diagrams

PCR Bias Consequences and Mitigation

Experimental Protocol for Bias Quantification

Practical Laboratory Protocols to Reduce Bias During Library Preparation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my "universal" 16S rRNA primers fail to detect all target microorganisms in my complex gut microbiome samples?

Even well-established "universal" primers cannot achieve 100% coverage of all microorganisms. In silico evaluations reveal that commonly used primers may miss tens of thousands of bacterial and archaeal species due to sequence mismatches in priming sites [39]. This limitation stems from unexpected variability even within traditionally conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene [40]. For example, the widely used 515F-806R primer pair covers approximately 83.6% of bacteria and 83.5% of archaea but misses 62,406 bacterial species and 3,306 archaeal species [39]. This coverage gap becomes particularly problematic when studying specific taxa of interest that may be systematically underrepresented.

Q2: How does primer degeneracy improve coverage, and what are the practical limits for degeneracy in primer design?

Degenerate primers incorporate mixtures of similar sequences with different nucleotides at variable positions, enabling recognition of multiple genetic variants within microbial communities [41]. This approach significantly enhances coverage of diverse microorganisms, as demonstrated when Hugerth et al. increased archaeal coverage from 53% to 93% by changing one position in a primer from C to Y (C/T) [39]. However, practical guidelines recommend:

- Avoiding degeneracy in the last 3 nucleotides at the 3' end [41]

- Designing primers with less than 4-fold degeneracy at any single position [41]

- Beginning with a primer concentration of 0.2 µM and increasing in 0.25 µM increments if PCR efficiency is poor [41] Excessive degeneracy reduces the effective concentration of primer molecules complementary to any specific template and increases the risk of non-specific amplification [41].

Q3: Which 16S rRNA variable region provides the best taxonomic resolution for microbiome studies?

No single variable region can differentiate all bacteria, but some regions outperform others for specific applications. The table below summarizes the discriminatory power of different hypervariable regions based on in silico analysis:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of 16S rRNA Variable Regions

| Target Region | Strengths | Limitations | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V3 | Good for Escherichia/Shigella; reasonable approximation of 16S diversity | Poor performance with Proteobacteria | General diversity surveys when full-length sequencing unavailable |

| V3-V5 | Suitable for Klebsiella | Poor classification of Actinobacteria | Targeted studies of specific pathogens |

| V4 | Most commonly used | Worst performance for species-level discrimination (56% fail accurate classification) | High-level taxonomic profiling |

| V6 | Distinguishes most bacterial species except enterobacteriaceae; differentiates CDC-defined select agents | Limited length for phylogenetic analysis | Diagnostic assays for specific pathogens |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | Highest taxonomic accuracy; enables species and strain-level discrimination | Requires third-generation sequencing platforms | Studies requiring maximum taxonomic resolution |

Sequencing the entire ~1500 bp 16S gene provides significantly better taxonomic resolution than any single sub-region, with nearly all sequences correctly classified to species level compared to substantial failure rates for sub-regions [35].

Q4: How can I computationally evaluate and improve the coverage of my custom primers?

The "Degenerate Primer 111" tool provides a user-friendly approach to enhance primer coverage by systematically adding degenerate bases to existing universal primers [39]. The workflow involves:

- Aligning your universal primer with the SSU rRNA gene of an uncovered target microorganism

- Iteratively generating a new primer that maximizes coverage for target microorganisms

- Maintaining or reducing coverage of non-target microorganisms This tool successfully modified eight pairs of universal primers, generating 29 new primers with increased coverage of specific targets [39]. Alternatively, the mopo16S software uses multi-objective optimization to simultaneously maximize efficiency, coverage, and minimize primer matching-bias [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Microbial Community Profiles Between Technical Replicates

Potential Cause: PCR amplification bias from non-primer-mismatch sources (NPM-bias), which can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more [9].

Solution:

- Implement log-ratio linear models: These models can correct for NPM-bias by estimating relative amplification efficiencies across taxa [9]

- Standardize PCR conditions: Limit cycle numbers (typically 25-30 cycles) and maintain consistent template concentrations across replicates [9] [11]

- Use mock communities: Include control communities with known composition to quantify and correct for amplification biases [9]

Validation Experiment:

- Pool aliquots of extracted DNA from each study sample into a single calibration sample

- Split into aliquots and amplify for different PCR cycle numbers (e.g., 15, 20, 25, 30 cycles)

- Sequence all aliquots and apply log-ratio linear models to estimate pre-PCR composition [9]

Diagram 1: Workflow for PCR bias mitigation

Problem: Low Amplification Efficiency with Degenerate Primers

Potential Cause: Suboptimal primer design or PCR conditions that reduce annealing specificity, particularly problematic with highly degenerate primer mixtures where only a limited number of primer molecules complement the template [41].

Solution:

- Follow degenerate primer design guidelines:

- Place degenerate positions toward the 5' end rather than the 3' end

- Use Met- or Trp-encoding triplets at the 3' end when possible (these amino acids have single codons)

- Limit total degeneracy to avoid excessive sequence variety [41]

- Optimize PCR conditions:

- Increase primer concentration gradually from 0.2 µM to 0.45-0.7 µM if needed

- Adjust annealing temperature using gradient PCR

- Include betaine or DMSO to stabilize annealing when using highly degenerate primers

Validation Method: Test primer efficiency using in silico evaluation with TestPrime against the SILVA SSU database before wet-lab experimentation [39] [40]. Aim for ≥70% coverage across target phyla and ≥90% coverage for key genera of interest [40].

Problem: Inadequate Taxonomic Resolution at Species/Strain Level

Potential Cause: Short-read sequencing of limited variable regions provides insufficient phylogenetic information for fine-scale discrimination [35].

Solution:

- Transition to full-length 16S sequencing: Third-generation sequencing platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enable sequencing of the entire ~1500 bp 16S gene, dramatically improving taxonomic resolution [35]

- Account for intragenomic variation: Bacterial genomes often contain multiple polymorphic 16S copies; properly resolving these variants can provide strain-level discrimination [35]

- Select optimal variable regions: If full-length sequencing is unavailable, choose variable regions based on your target taxa (see Table 1)

Experimental Design: For strain-level discrimination:

- Implement PacBio Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) with ≥10 passes to minimize errors

- Cluster sequences accounting for intragenomic 16S copy variants

- Validate putative strain-specific polymorphisms with complementary methods (e.g., qPCR, WGS)

Table 2: In silico Coverage of Selected Primer Pairs Across Dominant Gut Phyla

| Primer Set | Target Region | Actinobacteriota | Bacteroidota | Firmicutes | Proteobacteria | Overall Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3_P3 | V3 | 92% | 88% | 85% | 90% | High coverage across all phyla |

| V3_P7 | V3 | 90% | 86% | 82% | 88% | Balanced performance |

| V4_P10 | V4 | 85% | 92% | 80% | 83% | Strong for Bacteroidota |

| V1-V3_P5 | V1-V3 | 88% | 85% | 87% | 75% | Weak for Proteobacteria |

| V6-V8_P12 | V6-V8 | 82% | 80% | 90% | 85% | Strong for Firmicutes |

Note: Coverage percentages represent in silico amplification efficiency against SILVA database [40].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Optimal Primer Design and Validation

| Resource | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SILVA SSU Ref NR | Database | Reference for in silico primer evaluation | 510,495 aligned rRNA sequences; TestPrime tool for coverage calculation [39] [40] |

| Degenerate Primer 111 | Software | Adding degenerate bases to existing primers | Iterative approach to maximize target coverage without increasing non-target amplification [39] |

| mopo16S | Algorithm | Multi-objective primer optimization | Maximizes efficiency, coverage, minimizes matching-bias; avoids degenerate primers [12] |

| FAS-DPD | Software | Family-specific degenerate primer design | Scores primers weighting 3' end conservation more heavily; works from protein alignments [42] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard | Mock Community | Experimental validation | 19 bacterial/archaeal strains with known 16S copy variation [40] |

| TestPrime | Online Tool | In silico primer evaluation | Calculates coverage against SILVA database with user-defined mismatch parameters [39] [40] |

Diagram 2: Primer selection decision tree

In 16S rRNA sequencing for microbiome research, the choice of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enzyme is a critical experimental decision. PCR amplification bias, wherein some templates are amplified more efficiently than others, can significantly skew the representation of microbial communities, leading to erroneous biological conclusions. This technical support guide provides a detailed, evidence-based framework for selecting high-fidelity DNA polymerases to minimize these biases and ensure the accuracy and reliability of your 16S sequencing data.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is polymerase fidelity critical for 16S rRNA sequencing?

PCR enzymes inherently incorporate errors during DNA amplification. In 16S sequencing, where community composition is inferred from sequence counts, these errors can create spurious sequences that are misinterpreted as novel taxa or rare biosphere members, artificially inflating diversity estimates [43] [20]. High-fidelity polymerases possess 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity, which allows them to identify and correct misincorporated nucleotides. This results in significantly lower error rates, preserving the true biological sequence and ensuring that the observed microbial diversity reflects the actual sample composition.

FAQ 2: How does PCR enzyme choice contribute to amplification bias?

Amplification bias occurs when DNA from different microbial taxa is amplified with varying efficiencies, distorting their true relative abundances. This bias can originate from several factors, including:

- Primer-Template Mismatches: Sequence variation in the primer-binding region across different taxa can lead to dramatic differences in amplification efficiency [9].

- Non-Primer-Mismatch (NPM) Bias: Even with perfect primer matches, differences in template properties (e.g., GC-content, secondary structure) can cause certain sequences to be amplified more efficiently than others throughout the PCR process [9].

- Enzyme Processivity: An enzyme's ability to synthesize long DNA fragments can vary, potentially biasing against longer amplicons.

One study demonstrated that PCR NPM-bias alone can skew estimates of microbial relative abundances by a factor of 4 or more [9]. High-fidelity enzymes, often paired with optimized buffers, can help mitigate these biases by providing more uniform amplification across diverse templates.

FAQ 3: What are the key performance metrics when comparing high-fidelity polymerases?

When selecting an enzyme for 16S sequencing, consider the following performance metrics, which are summarized in the table below:

- Fidelity (Error Rate): The frequency of misincorporated nucleotides, typically expressed as errors per base per duplication. Lower values are better.

- Processivity: The number of nucleotides a polymerase can incorporate in a single binding event, important for amplifying longer targets.

- Specificity: The ability to amplify only the intended target, minimizing non-specific products and primer-dimer formation. Hot-start enzymes are engineered to remain inactive at room temperature, greatly enhancing specificity [22] [44].

- Speed: The extension rate (e.g., seconds per kilobase), which can reduce overall cycling time.

- Inhibitor Tolerance: The enzyme's resistance to common PCR inhibitors found in sample types like soil or blood [22].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DNA Polymerase Performance

| DNA Polymerase | Published Error Rate (Errors/bp/duplication) | Fidelity Relative to Taq | Proofreading Activity | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | ( 1 - 20 \times 10^{-5} ) [45] | 1x | No | Standard for routine PCR; lower cost but high error rate |

| Pfu | ( 1 - 2 \times 10^{-6} ) [45] | 6–10x better [45] | Yes | Classic high-fidelity enzyme |

| Phusion | (\sim 4.0 \times 10^{-7}) (HF buffer) [45] | >50x better [45] | Yes | High fidelity and fast extension time |

| Platinum SuperFi II | Not specified in data | >300x better [44] | Yes | Very high accuracy, suitable for complex cloning |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PCR Issues in 16S Sequencing

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems in 16S Sequencing Workflows

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Errors / High Error Rate | Low-fidelity polymerase | Use a high-fidelity, proofreading polymerase (e.g., Pfu, Phusion, Q5) [46]. |

| Suboptimal reaction conditions | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; decrease Mg2+ concentration; use fresh, balanced dNTPs [46]. | |

| No Product or Low Yield | Poor template quality or inhibitors | Re-purify template DNA; use polymerases with high inhibitor tolerance; add BSA [22] [47]. |

| Incorrect annealing temperature | Recalculate primer Tm and optimize annealing temperature using a gradient cycler [22] [48]. | |

| Insufficient polymerase | Increase the amount of polymerase or use an enzyme with higher sensitivity [22]. | |

| Non-Specific Bands / Multiple Bands | Lack of specificity / mispriming | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature [44]. |

| Annealing temperature too low | Increase the annealing temperature stepwise [22]. | |

| Excess Mg2+ or primers | Optimize Mg2+ concentration; titrate primer concentrations (typically 0.1–1 µM) [22] [46]. | |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | Primer self-complementarity | Redesign primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity [48] [47]. |

| High primer concentration | Lower the primer concentration in the reaction [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing PCR Amplification Bias Using a Mock Community

Purpose: To empirically quantify the amplification bias introduced by different PCR enzymes in your 16S sequencing pipeline.

Background: Using a mock microbial community with known, defined composition allows you to directly compare the sequencing results to the expected abundances, providing a ground truth for measuring bias [9] [43].

Materials:

- Mock Community: Genomic DNA from a defined set of bacterial strains (e.g., 20-30 strains from ZymoBIOMICS or ATCC).

- Test Polymerases: The high-fidelity enzymes you wish to compare (e.g., Q5, Phusion, Pfu).

- 16S rRNA Primers: Your standard primers targeting the V3-V4 or other hypervariable region.

- qPCR Instrument or Gel Electrophoresis System: For quantifying amplification efficiency.

Method:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the mock community DNA in triplicate with each test polymerase, strictly controlling the number of cycles (e.g., 25-30 cycles) [22].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified products and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the raw sequencing data using your standard 16S pipeline (e.g., DADA2, QIIME2) to obtain Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or OTUs and their counts.

- Bias Calculation:

- Map the resulting ASVs to the known sequences of the mock community.

- For each taxon, calculate the Observed/Expected Ratio:

(Observed Read Count / Total Reads) / (Expected Genomic DNA Input / Total Input) - The variation in this ratio across taxa quantifies the bias introduced by each polymerase. An ideal enzyme would show a ratio close to 1 for all taxa.

The following workflow summarizes the experimental design for assessing PCR bias:

Protocol 2: A Paired Modeling and Experimental Approach to Mitigate Bias

Purpose: To measure and computationally correct for PCR NPM-bias directly from your experimental samples without a mock community.

Background: This method, adapted from [9], involves creating a calibration curve from your own samples to model how bias increases with PCR cycle number.

Method:

- Create Calibration Sample: Pool aliquots of extracted DNA from all study samples into a single calibration sample.

- Cycle Gradient PCR: Split the calibration sample into multiple aliquots. Amplify each aliquot for a different number of PCR cycles (e.g., 15, 20, 25, 30 cycles) using your chosen high-fidelity polymerase.

- Sequence and Model: Sequence all aliquots and use a log-ratio linear model (e.g., as implemented in the R package

fido) to analyze the data [9]. The model estimates the true starting composition (intercept) and the taxon-specific amplification efficiencies (slope). - Apply Correction: Use the fitted model to correct the bias in your main experimental dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Minimizing PCR Bias in 16S Sequencing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target DNA with minimal sequence errors. | Select enzymes with proofreading activity (e.g., Phusion, Q5, Pfu). Verify error rates from vendor data [45] [44]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | Provides a known standard for quantifying accuracy and bias. | Choose communities with complexity relevant to your sample type (e.g., HC227 for high complexity) [43]. |

| Hot-Start Polymerase | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation prior to the initial denaturation step. | Critical for improving specificity and yield in 16S PCR [44]. |

| PCR Additives (BSA, Betaine) | Enhances amplification of difficult templates (e.g., high GC-content) and mitigates effects of inhibitors. | BSA can bind inhibitors; betaine helps denature GC-rich secondary structures [22] [48]. |

| Gel Extraction / PCR Cleanup Kit | Purifies the target amplicon from non-specific products, primer-dimers, and unused reagents. | Essential for obtaining a clean library for sequencing. |

| Standardized 16S rRNA Primer Set | Ensures specific and uniform amplification of the target variable region. | Use well-validated, high-purity primers. Consider degenerate primers to reduce primer bias [11]. |

In 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a critical step for amplifying target genes from complex microbial communities. However, standard thermocycling conditions can introduce significant biases by preferentially amplifying certain bacterial templates over others, leading to a distorted view of the true microbial composition. This guide addresses how the precise control of denaturation time and ramp rates—often overlooked parameters—can be optimized to minimize these biases, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reproducibility of your microbiome research.

FAQ: Thermocycling and PCR Bias in 16S Sequencing

1. How does denaturation time specifically influence bias in 16S amplicon sequencing? Insufficient denaturation time can lead to incomplete separation of DNA strands, particularly for templates with high GC content or secondary structures. This results in inefficient primer binding and biased amplification of certain sequences in the community. Overly long denaturation times, however, can reduce polymerase activity over many cycles, also skewing results [19] [22]. The goal is to use the minimum denaturation time that ensures complete template separation for your specific community profile.

2. What is the impact of ramp rates on amplification fidelity and bias? Ramp rates—the speed at which the thermocycler transitions between temperatures—can influence the specificity of primer annealing. Very fast ramp rates may not allow sufficient time for nonspecific primer-template complexes to dissociate, potentially increasing off-target amplification. Slower ramp rates can enhance specificity but also prolong the total protocol time and may increase enzyme exposure to sub-optimal temperatures. The optimal rate is a balance that maximizes specific product yield while minimizing nonspecific amplification and maintaining polymerase integrity [22].

3. Can optimized thermocycling compensate for suboptimal primer choice? While optimized thermocycling can improve the performance of a given primer set, it cannot fully overcome fundamental flaws in primer design, such as a lack of universality. Different primer pairs targeting various variable regions (V-regions) of the 16S rRNA gene produce markedly different microbial profiles [10]. Thermocycling optimization should therefore be viewed as a fine-tuning step that works in concert with, not as a replacement for, well-validated, specific primer selection.

4. How do I determine the optimal number of PCR cycles to minimize bias? Mathematical modeling and experimental data suggest that the optimal number of PCR cycles for multitemplate amplification like 16S sequencing is typically between 15 and 20 cycles [49]. Amplification with fewer than 15 cycles may not yield sufficient product, while exceeding 20 cycles can lead to a sharp increase in bias and artifacts due to the exponential nature of PCR and the depletion of reagents. The use of more than 20 cycles is detrimental to both the detection of community members and the accuracy of abundance estimates [49].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Thermocycling-Related Issues

Problem 1: Low Library Complexity and High Duplicate Reads

- Symptoms: High duplication rates in sequencing data; low number of unique reads.

- Potential Thermocycling Causes: Excessive number of PCR cycles leading to over-amplification of dominant sequences [19].

- Solutions:

Problem 2: Chimeras and Spurious Amplicons

- Symptoms: Presence of artificial hybrid sequences and non-target amplification products.

- Potential Thermocycling Causes: Overly long extension times and insufficient denaturation conditions can promote mis-priming and template switching [22].

- Solutions:

Problem 3: Skewed Microbial Abundance Profiles

- Symptoms: Known or expected microbial ratios from mock communities are not reproduced in sequencing data.

- Potential Thermocycling Causes: Non-homogeneous amplification efficiencies between different templates, exacerbated by suboptimal ramp rates and denaturation [30].

- Solutions:

- Consider thermal-bias PCR: Explore novel protocols that use a large difference in annealing temperatures between stages to improve amplification of mismatched targets without degenerate primers [50].

- Apply bias correction models: Use computational post-processing with reference-based models to correct for known, protocol-specific biases [23].

Optimized Thermocycling Parameters

The following table summarizes key thermocycling parameters to minimize amplification bias, based on experimental data and modeling.

Table 1: Key Thermocycling Parameters for Minimizing 16S Amplification Bias

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Rationale & Impact on Bias |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Cycles | 15 - 20 cycles | Maximizes species detection and abundance accuracy; more cycles increase bias and artifacts [49]. |

| Denaturation Time | As short as 5-30 sec at 95-98°C | Must be sufficient for complete strand separation without unnecessarily degrading polymerase activity [22]. |

| Annealing Temperature | 3-5°C below the lowest primer Tm | Critical for specificity; can be optimized stepwise in 1-2°C increments [22]. |

| Template Input | ≤ 50 ng | Higher amounts can be detrimental to accuracy; optimal yield and bias correction occur at or below this level [49]. |

Table 2: Impact of PCR Cycle Number on Data Quality (Mathematical Model Predictions) [49]

| Number of PCR Cycles | Species Detection | Accuracy of Abundance Estimates |

|---|---|---|

| < 15 cycles | Sub-optimal | Sub-optimal |

| 15 - 20 cycles | Optimal | Optimal |

| > 20 cycles | Detrimental | Detrimental |

Experimental Protocol: Reference-Based Bias Correction

For labs requiring high-fidelity abundance data, using a reference-based bias correction model can significantly improve results. The following workflow, derived from a published model, corrects for biases introduced by different sequencing platforms, 16S rRNA regions, and polymerases [23].

Diagram 1: Bias correction workflow.

Step-by-Step Methodology [23]:

- Establish Reference Communities: Use well-characterized mock microbial communities with known genomic compositions. These can be commercially available or custom-made.

- Absolute Quantification: Use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) with specific primer-probe assays (e.g., targeting the single-copy

rpoBgene) to establish the true, absolute abundances of each species in the community. This serves as the gold standard. - Sequencing and Analysis: Process the same mock communities through your standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing pipeline (including DNA extraction, library prep with your thermocycling protocol, and sequencing).

- Calculate Bias Coefficients: Bioinformatically determine the observed abundance of each species from the sequencing data. For each species, calculate a bias correction factor by comparing its ddPCR-derived abundance to its sequencing-derived abundance.

- Apply the Model: In subsequent experimental samples, apply these pre-determined correction factors to the observed sequencing abundances to calculate a bias-corrected profile. The model has been shown to be effective even when the reference contains only ~40% of the species present in the test sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimizing 16S Sequencing

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance in Bias Reduction |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity, Hot-Start Polymerase | Reduces nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup, improving library complexity and specificity [22]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) System | Provides absolute quantification of bacterial load and species ratios in mock communities, serving as a ground truth for bias correction models [23]. |

| Synthetic Mock Communities | Comprised of genomes from known bacterial species in defined ratios. Essential for validating and correcting for protocol-specific biases [23] [10]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., GC Enhancers) | Co-solvents that help denature GC-rich templates and sequences with secondary structures, promoting more uniform amplification across diverse templates [22]. |

| Non-Degenerate Primers / Thermal-Bias PCR Kit | Using non-degenerate primers in a thermal-bias protocol can yield more proportional amplification than degenerate primers, which can act as inhibitors [50]. |

Strategic Reduction of PCR Amplification Cycles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I consider reducing the number of PCR cycles in my 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow? Reducing PCR cycle numbers is a key strategy to minimize amplification bias, which can skew the representation of microbial communities in your samples. Fewer cycles limit the exponential amplification of more efficiently copied templates, preventing the over-representation of certain taxa and providing a more accurate profile of the original microbial composition [11] [51]. While higher cycles can increase coverage in very low biomass samples [17], for standard samples, a lower cycle number enhances quantitative accuracy.

Q2: What is a typical, recommended PCR cycle number for 16S rRNA gene amplification? Commonly used PCR cycle numbers in the literature vary. Some laboratories standardly use 25 cycles for high microbial biomass samples, such as feces [17]. However, for samples with low microbial biomass, such as milk or blood, studies often use much higher cycle numbers, such as 35 or 40, to obtain sufficient library coverage [17]. The optimal number should be determined empirically, balancing sufficient yield with the need to minimize bias.

Q3: What are the consequences of using too many PCR cycles? Over-amplification (e.g., exceeding 35 cycles) can lead to several issues:

- Increased Amplification Bias: Taxa with higher amplification efficiencies become disproportionately over-represented [9] [11].

- Higher Chimera Formation: Incomplete PCR products can act as primers, leading to chimeric sequences that are not derived from a single organism. One study found that 8% of raw reads could be chimeric [20].

- Elevated Contaminant Levels: A high number of PCR cycles can lead to an increase in contaminants detected in negative controls [51].

- Rise in Spurious OTUs: Sequencing errors and chimeras that escape detection can lead to the identification of false operational taxonomic units (OTUs) [20].

Q4: Can I simply reduce cycles without adjusting other parts of my protocol? Not always. Simply reducing cycles may result in insufficient library yield for sequencing. To compensate, you should consider:

- Increasing Template DNA Input: Using more input DNA provides more starting templates, reducing the need for excessive amplification [11] [51]. One study suggests using ~125 pg input DNA as an optimal parameter [51].

- Optimizing Purification: Ensure your DNA extraction and library purification are efficient to remove PCR inhibitors and avoid sample loss [19].

Q5: How does PCR bias affect my data analysis? PCR bias can significantly impact both alpha and beta diversity measures. It can lead to incorrect estimates of microbial richness (alpha diversity) and distort the perceived differences between microbial communities (beta diversity) [11]. Computational corrections can be applied, but the most robust solution is to minimize the bias experimentally during library preparation [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Library Yield After Reducing PCR Cycles

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Input DNA | Low quantification readings (Qubit); faint or no bands on gel. | Re-quantify DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit). Concentrate or use more input DNA if possible [11] [51]. |

| PCR Inhibitors | Failed amplification even in positive controls; degraded DNA signs in electropherogram. | Re-purify the DNA using a clean-up kit (e.g., bead-based purification) to remove contaminants like salts or phenol [19]. |

| Suboptimal PCR Reagents/Conditions | Inconsistent amplification across samples. | Use a high-fidelity polymerase mastermix. Optimize primer annealing temperatures. Ensure all reagents are fresh and properly stored [19]. |

Problem: Increased Variability Between Replicates After Cycle Reduction

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Amplification | Large differences in community profiles between technical replicates from the same sample. | Ensure a sufficient amount of template DNA is used to reduce the impact of random sampling effects during the initial PCR cycles [11]. |

| Pipetting Errors | Inconsistent yields and profiles, particularly in manual preps. | Use master mixes for PCR reagents to reduce pipetting steps and variability. Calibrate pipettes regularly [19]. |

| Inconsistent Bead-Based Cleanup | Variable size selection and sample loss. | Standardize bead-to-sample ratios and mixing techniques across all samples. Avoid over-drying bead pellets [19]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from published studies on the effects of PCR cycle number.

| Study Sample Type | Cycle Numbers Compared | Key Findings on Coverage & Diversity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine milk, murine pelage and blood (low biomass) | 25, 30, 35, 40 | Coverage: Increased with higher cycle numbers.Richness/Beta-diversity: No significant differences detected. | [17] |

| Human fecal samples | ~25 vs higher cycles | Contamination: A high number of PCR cycles lead to an increase in contaminants detected in negative controls. | [51] |

| Arthropod mock communities | 4, 8, 16, 32 | Bias: Reduction of PCR cycles did not have a strong effect on amplification bias. The association of taxon abundance and read count was less predictable with fewer cycles. | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Optimizing PCR Cycles for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

This protocol is adapted from methods used in the search results to systematically evaluate and reduce PCR cycle-induced bias [17] [11] [51].

Title: Protocol for Systematic Evaluation of PCR Cycle Number in 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

1. Objective: To determine the optimal PCR cycle number that provides sufficient library yield while minimizing amplification bias for a specific sample type and DNA extraction method.

2. Materials:

- Extracted genomic DNA from your sample set.

- PCR Primers: Tailored primers targeting the desired hypervariable region (e.g., V4 region with U515F/806R primers) [17].

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase Master Mix: (e.g., Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix) [17] [6].

- Thermal Cycler