Strategies for Editing Hard-to-Transfect Cells: A 2025 Guide to Optimization and Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tackling the significant challenge of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in hard-to-transfect cell types, such as primary cells, stem...

Strategies for Editing Hard-to-Transfect Cells: A 2025 Guide to Optimization and Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tackling the significant challenge of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in hard-to-transfect cell types, such as primary cells, stem cells, and immune cells. It covers the foundational understanding of why these cells are difficult to modify, explores advanced delivery methods from electroporation to direct nuclear injection, and offers systematic troubleshooting and optimization protocols to maximize editing efficiency while minimizing cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the guide details rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of different strategies to ensure the generation of high-quality, reliable data for preclinical and therapeutic applications.

Understanding Hard-to-Transfect Cells: A Foundational Guide for Researchers

Cell transfection, the process of introducing foreign nucleic acids into cells, is a foundational technique for genetic research and therapeutic development [1]. However, primary cells, stem cells, and immune cells are notoriously "hard-to-transfect." These cells are often more sensitive, may not divide frequently, and possess robust innate defense mechanisms, making standard transfection protocols ineffective [2] [3]. Successfully editing these cell types is crucial for advancing research in regenerative medicine, cancer immunotherapy, and fundamental biology [4] [5]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to address the specific challenges you may encounter in your experiments.

▷ FAQ: Defining the Challenge

What makes primary cells, stem cells, and immune cells hard to transfect?

These cell types present a unique combination of biological barriers that hinder efficient transfection [3] [1]:

- Limited Division Cycles: Primary cells have a finite number of cell divisions. Many transfection methods, particularly those using DNA, rely on the breakdown of the nuclear envelope during cell division for the genetic material to access the nucleus.

- Sensitivity to Manipulation: These cells are highly sensitive to physical and chemical perturbations. Techniques like electroporation can induce significant cell death if not carefully optimized [1].

- Robust Immune Recognition: Immune cells, in particular, are specialized to detect and respond to foreign molecules, including transfected nucleic acids, which can trigger cytotoxic responses and reduce viability [5].

- Low Proliferation Rates: Many stem cells and primary cells divide slowly or can be maintained in a non-dividing state, creating a challenge for nucleic acids to enter the nucleus.

What are the main considerations when choosing a transfection method?

Selecting the right protocol depends on several key factors [3]:

- Transient vs. Stable Transfection: Determine if you need short-term expression (transient) or permanent genomic integration (stable) for your application.

- Cell Viability vs. Efficiency: A balance must be struck. High-efficiency methods can often be more cytotoxic.

- Format of CRISPR Components: You can deliver the CRISPR machinery as DNA, mRNA, or pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. RNP delivery is often favored for hard-to-transfect cells due to its rapid activity and reduced off-target effects [2] [3].

- Throughput and Equipment: Consider the number of samples and the specialized equipment available in your lab.

How can I improve gene editing efficiency in hard-to-transfect cells?

Improving efficiency requires a multi-faceted approach [2] [6]:

- Use High-Quality Reagents: Ensure nucleic acids are pure and endotoxin-free. For synthetic sgRNA, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification is recommended [7].

- Optimize Delivery Conditions: Systematically test parameters like voltage, pulse time, and reagent concentration. One survey found researchers test an average of seven conditions to find the optimal protocol [6].

- Utilize Engineered Cas9 Variants: High-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) can reduce off-target effects, improving the reliability of your edits [8].

- Employ Chemical Modifications: Chemically modifying sgRNAs can enhance their stability and genome editing efficiency in primary cells [2].

▷ Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient Delivery: Your transfection method may not be optimal for your specific cell type.

- Poor gRNA Design: The guide RNA may have low on-target activity.

- Suboptimal Expression: Cas9/gRNA expression may be too low.

- Solution: Verify that your promoter is active in your cell type. Use a positive control gRNA (e.g., targeting a housekeeping gene) to confirm your system is working [6].

Problem: High Cell Death or Toxicity Post-Transfection

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Delivery Method Toxicity: The physical or chemical stress of transfection is killing your cells.

- Cytotoxic Reagents: Chemical transfection reagents can be toxic at high concentrations.

Problem: High Off-Target Effects

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Prolonged Cas9 Expression: Stable expression or long-lasting activity of Cas9 increases the chance of off-target cutting.

- Solution: Use transient delivery methods. RNP delivery is ideal because the complex degrades quickly, limiting the window for off-target activity [3].

- Non-Specific gRNA: The gRNA sequence may bind to multiple genomic sites.

Problem: Inability to Detect Successful Edits (Mosaicism)

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Mosaicism: The target site is not edited in all cells, or edits are heterogeneous.

- Solution: Enrich for successfully edited cells. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with fluorescently labeled donor DNA or a co-selection strategy (e.g., introducing a concurrent, selectable edit at another locus) to isolate a pure population of edited cells [2].

▷ Experimental Protocol: RNP Nucleofection of Primary T Cells

This protocol is adapted for transfecting primary human T cells using Cas9 RNP complexes via nucleofection, a method noted for high efficiency and low toxicity in these sensitive cells [2].

Key Advantages of RNP Delivery:

- Rapid editing, reducing time for off-target effects.

- No risk of genomic integration of plasmid DNA.

- High efficiency and reduced cytotoxicity in primary cells.

Materials:

- Primary human T cells

- Cas9 protein (with nuclear localization signal)

- Synthetic sgRNA (targeting your gene of interest)

- Nucleofector Device and appropriate Cell Line Kit

- Pre-warmed culture medium

Procedure:

- Prepare RNP Complex: Complex a purified Cas9 protein with synthetic sgRNA at a predetermined optimal ratio (e.g., 3:1 mass ratio) in a microcentrifuge tube. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow RNP formation.

- Harvest Cells: Isolate and activate T cells as required by your experimental design. Count and centrifuge 1-2 x 10^6 cells per condition.

- Nucleofection: Resuspend the cell pellet in the provided Nucleofector Solution. Combine the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex. Transfer the entire mixture to a certified cuvette and nucleofect using the pre-optimized program for primary T cells (e.g., program EH-100).

- Recovery: Immediately after pulsing, add pre-warmed culture medium to the cuvette and transfer the cells to a culture plate. Incubate cells at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Analysis: Assess editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-transfection using genomic DNA extraction followed by T7 Endonuclease I assay or next-generation sequencing.

▷ The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table: Key research reagents and their applications for editing hard-to-transfect cells.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized single-guide RNA; offers high purity, consistency, and reduced immune activation compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) RNA [7]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) with point mutations that reduce off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity [8]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed complex of Cas9 protein and sgRNA; the preferred format for hard-to-transfect cells due to rapid kinetics and minimal off-target effects [2] [3]. |

| Nucleofector System | An electroporation-based technology optimized for direct nuclear delivery of cargo, achieving high efficiency in primary and stem cells [2]. |

| Chemical Modifications (sgRNA) | Incorporation of specific chemical groups into the sgRNA backbone to enhance nuclease resistance and improve editing efficiency in primary cells [2]. |

| Positive Control gRNAs | Validated gRNAs targeting essential genes (e.g., PPIB); used to distinguish between delivery/editing failures and target-specific gRNA issues during optimization [6]. |

▷ Decision Workflow for Transfection Methods

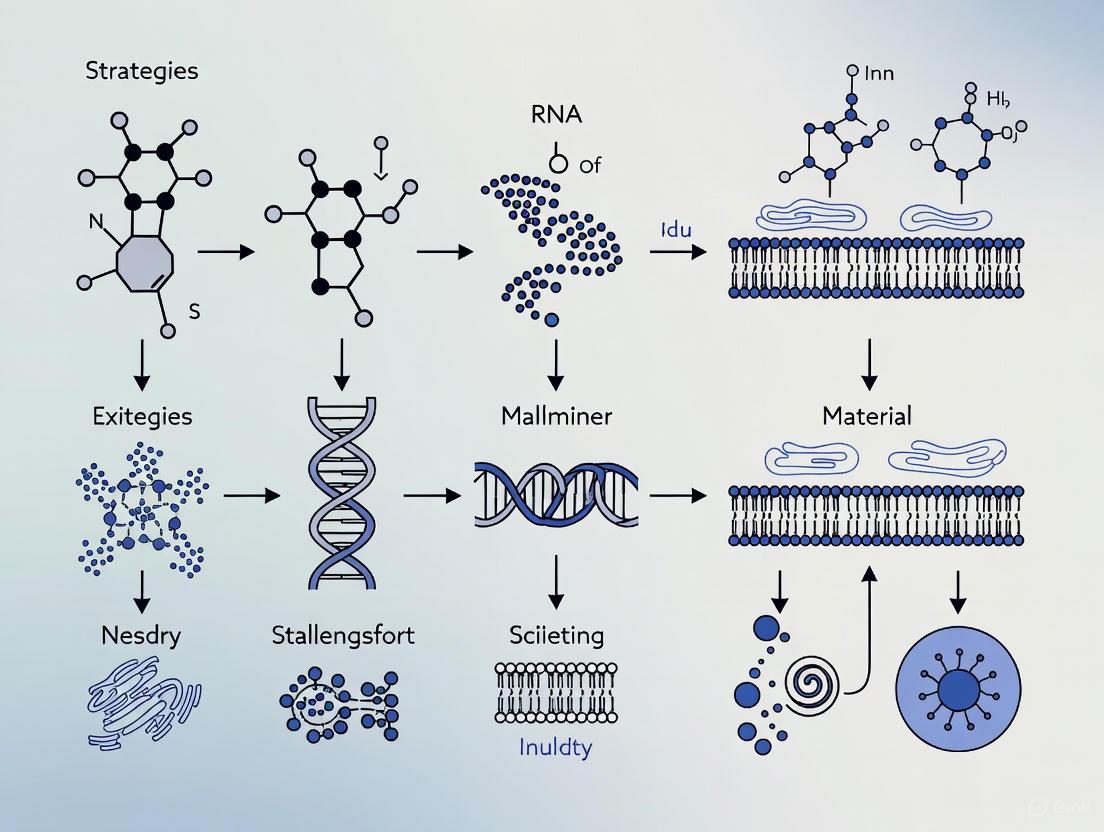

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate transfection method and CRISPR component format based on your cell type and experimental goals.

▷ Comparison of Transfection Methods

Table: A comparison of common transfection methods for hard-to-transfect cells, highlighting key advantages and limitations [2] [3] [1].

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipofection | Lipid complexes fuse with cell membrane. | Cost-effective, high throughput. | Low efficiency in hard-to-transfect cells. | Immortalized cell lines. |

| Electroporation | Electric pulse forms pores in the membrane. | Easy, fast, broad applicability. | Can cause significant cell death; requires optimization. | Many cell types, including some primary cells. |

| Nucleofection | Electroporation optimized for nuclear delivery. | High efficiency, direct nuclear transfer, works in non-dividing cells. | Requires specialized reagents and equipment. | Primary cells, stem cells, immune cells. |

| Microinjection | Mechanical injection via fine needle. | High precision. | Very low throughput, technically demanding. | Zygotes, oocytes. |

| Viral Transduction | Uses viral vectors (e.g., Lentivirus, AAV). | Very high efficiency. | Time-consuming, safety concerns, potential immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis. | Hard-to-transfect cells for stable expression. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes a cell type "hard-to-transfect"? Several biological barriers contribute to this classification. Key factors include:

- Membrane Composition: The cell membrane, composed of lipids and proteins, is the primary physical barrier to nucleic acid delivery [9]. Its specific composition can hinder the uptake of transfection complexes.

- Division Rates: Actively dividing cells are more amenable to transfection than quiescent (non-dividing) cells. Methods like viral transduction or electroporation are often required for non-dividing cells [10].

- Innate Immune Responses: Cells can recognize foreign nucleic acids, triggering an immune response that can shut down transgene expression and cause cytotoxicity [11]. Furthermore, specific immune cells, like macrophages, are specialized to phagocytose (engulf) foreign particles, which can include transfection complexes, thereby clearing them before they can deliver their cargo [12].

FAQ 2: My CRISPR knockout efficiency is low in primary T cells. What should I check first? Low knockout efficiency often stems from poor delivery or suboptimal experimental conditions. Prioritize these checks:

- Transfection Method: Standard chemical methods often fail with sensitive primary cells. Use optimized electroporation protocols or lipid nanoparticles designed for immune cells [13] [6].

- sgRNA Design: Ensure your single-guide RNA (sgRNA) has high predicted activity and specificity. Test multiple (3-5) sgRNAs for your target gene to identify the most effective one [13].

- Cell Health: Use cells with high viability (>90%) and at the correct density. For T cells, a density of 5 × 10^5 to 2 × 10^6 cells/mL at the time of transfection is a good starting point [10].

FAQ 3: How does the innate immune system, particularly phagocytes, interfere with transfection? Immune phagocytes, such as macrophages, are programmed to engulf and clear foreign particles, a process highly dependent on the particle's physical properties [12]. Transfection complexes can be recognized as foreign material. The mode of uptake—whether through receptor-mediated phagocytosis for larger particles or endocytosis for smaller ones—can lead to the degradation of the nucleic acid payload in lysosomes before it reaches the nucleus, thereby reducing transfection efficiency [12].

FAQ 4: Are there methods to bypass the biological barriers in hard-to-transfect cells? Yes, advanced strategies focus on precision delivery to circumvent these barriers:

- Direct Nuclear Injection: For the ultimate bypass of cytoplasmic and membrane barriers, methods are being developed to gently inject CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) directly into the nucleus of single cells, ensuring delivery and drastically improving editing efficiency in recalcitrant cells [14].

- Engineered Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): EVs are natural delivery vesicles that can be bioengineered to carry therapeutic cargo. They can bypass biological barriers, including immune recognition, and show promise for delivering to sensitive sites like the central nervous system [15].

- Viral Transduction: Viral vectors (e.g., lentiviruses, AAVs) are highly effective at bypassing cellular barriers but carry risks such as immunogenicity and insertional mutagenesis [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Transfection/Knockout Efficiency

Problem: Low percentage of cells expressing the transgene or showing gene editing after a CRISPR experiment.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal sgRNA | Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., Benchling) to check for specificity and predicted efficiency. | Design and test 3-5 different sgRNAs for the same target gene [13]. |

| Inefficient Delivery | Check transfection efficiency with a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP). If low, the method is unsuitable. | Switch to a more effective method (see Table 1). For CRISPR, use pre-complexed RNP and electroporation [13] [14]. |

| Poor Cell Health | Check viability before transfection. Ensure cells are not over-confluent. | Use cells with >90% viability and passage cells 24 hours before transfection to ensure they are actively dividing [10]. |

| Strong Immune Response | Look for signs of cytotoxicity (e.g., rounded, detached cells). | Use purified nucleic acids and consider using reagents that mitigate immune activation. For advanced models, use engineered EVs [11] [15]. |

Issue 2: High Cell Death Post-Transfection

Problem: Excessive cell death observed 24-48 hours after the transfection procedure.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic Transfection Method | Compare death rates between transfected and non-transfected control cells. | Titrate the amount of transfection reagent and nucleic acid. Optimize electroporation voltage and pulse length [6] [10]. |

| Serum or Antibiotics in Medium | Review your transfection protocol. | Form lipid-nucleic acid complexes in serum-free medium. Avoid antibiotics during the transfection step [10]. |

| Toxic Transgene | Transfect with a non-toxic control vector (e.g., GFP). If death is high, the method is the issue. | Use an inducible expression system to control the timing and level of toxic gene expression. |

Visual Guide: Cellular Uptake Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates how physical properties of delivery complexes influence their uptake by immune cells, which can lead to degradation and failed transfection.

Issue 3: Inconsistent Results Across Replicates

Problem: Transfection efficiency or cell viability varies significantly between experimental repeats.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Cell Passage Number | Record the passage number of cells used. High passage numbers (>30) can behave differently. | Use low-passage cells (<30 passages after thawing) and establish a frozen stock of low-passage vials [10]. |

| Inconsistent Cell Seeding Density | Check confluency at the time of transfection. It should be consistent (e.g., 70-90% for adherent cells). | Maintain a standard seeding protocol and ensure consistent timing between seeding and transfection [10]. |

| Poor Quality or Quantity of Nucleic Acid | Check the purity and concentration of DNA/RNA. | Use high-quality, endotoxin-free plasmid preparations. Ensure the nucleic acid is free of RNases or DNases [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Transfection in a New Cell Line

This protocol provides a systematic approach to establishing a transfection workflow for a hard-to-transfect cell type.

1. Pre-Optimization Preparation:

- Cell Line Validation: Ensure your cell line is healthy, mycoplasma-free, and used at a low passage number [10].

- Positive Control: Include a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP plasmid or mRNA) to distinguish delivery failure from expression failure [6].

- Nucleic Acid Quality: Use high-purity, endotoxin-free DNA or highly purified RNA.

2. Selection and Titration of Transfection Method:

- Method Selection: Choose a method based on your cell type (see Table 1).

- Titration: Set up a matrix experiment to titrate the key parameters. The example below is for lipid-based transfection.

| Plate Well | Nucleic Acid (µg) | Transfection Reagent (µL) | Cell Density (% Confluency) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 60% |

| A2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 60% |

| A3 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 60% |

| B1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 60% |

| B2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 60% |

| B3 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 60% |

| C1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 80% |

| C2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 80% |

3. Analysis:

- At 24-48 hours post-transfection, analyze cells for efficiency (e.g., % GFP-positive cells via flow cytometry) and viability (e.g., using a dye exclusion test or metabolic assay) [6].

- Select the condition that offers the best balance of high efficiency and low cell death.

Protocol 2: High-Efficiency CRISPR Knockout in Immune Cells

This protocol is adapted for difficult-to-edit immune cells like THP-1 or primary T cells.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- sgRNA Preparation: Design 3-4 sgRNAs using a bioinformatics tool (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling). Synthesize high-quality, chemically modified sgRNAs for improved stability [13] [6].

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex the purified Cas9 protein with the sgRNA at a predetermined molar ratio. Incubate at room temperature for 10-15 minutes to form the RNP complex.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells and wash them with PBS. Resuspend the cell pellet in an electroporation buffer at a concentration of 1-2 x 10^6 cells/100 µL. Keep cells on ice.

- Electroporation:

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex.

- Transfer the mixture to an electroporation cuvette.

- Apply the optimized electroporation program. For THP-1 cells, this might be a single pulse of 1350V for 10ms, but this must be determined empirically [6].

- Post-Transfection Recovery: Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells to pre-warmed, antibiotic-free culture medium. Allow the cells to recover in an incubator for at least 24-48 hours before analysis.

- Validation:

- Genomic DNA Analysis: Extract genomic DNA and use T7 Endonuclease I assay or TIDE sequencing to quantify indel formation [13].

- Protein Analysis: Confirm knockout at the protein level by Western blotting 3-5 days post-editing [13].

- Functional Assays: Perform a reporter assay or other relevant functional test to confirm loss of gene function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Chemical vector for encapsulating and delivering nucleic acids (siRNA, mRNA, CRISPR RNP) into cells via endocytosis [13]. | Delivery of CRISPR components into immune cells. |

| Electroporation Systems | Physical method using electrical pulses to create transient pores in the cell membrane, allowing nucleic acids or RNPs to enter the cytoplasm [13] [10]. | High-efficiency RNP delivery for CRISPR knockout in primary T cells. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Viral vector for stable gene integration; can transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells [11]. | Creating stable cell lines with integrated transgenes or Cas9 protein. |

| WGA Conjugates | Fluorescent lectins that bind to sugars on the cell membrane; useful for outlining cell boundaries and studying membrane dynamics [9]. | Visualizing cell morphology and confirming membrane integrity post-transfection. |

| CellMask Stains | Lipophilic fluorescent dyes that intercalate into the plasma membrane, providing uniform labeling for live-cell imaging [9]. | Cell segmentation in high-content screening and monitoring plasma membrane health. |

| BioTracker Organelle Dyes | Live-cell permeable fluorescent dyes targeting specific organelles (mitochondria, lysosomes, nucleus) to monitor cell health and function [16]. | Assessing metabolic activity and cytotoxicity post-transfection. |

| Stably Expressing Cas9 Cell Lines | Cell lines engineered to constitutively express the Cas9 nuclease, eliminating the need for its delivery and improving editing reproducibility [13]. | Streamlining CRISPR screens and knockout experiments by only requiring sgRNA delivery. |

Why CRISPR-Cas9 Poses Unique Challenges in Sensitive Cell Types

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, yet its application in sensitive cell types—such as primary human T cells, stem cells, and neurons—presents unique challenges. These delicate systems, crucial for therapeutic development and basic research, are particularly vulnerable to the genotoxic stress, delivery inefficiencies, and unintended consequences associated with conventional CRISPR-Cas9 editing. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance for researchers working within the broader context of hard-to-transfect cell type research, addressing the specific hurdles that arise when manipulating these biologically precious resources.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

What makes sensitive cell types more vulnerable to CRISPR-Cas9 editing?

Sensitive cells, including primary human T cells, stem cells, and terminally differentiated cells, are particularly vulnerable due to their low tolerance for DNA damage, limited division capacity, and complex native physiology.

- DNA Damage Sensitivity: The fundamental mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 involves creating double-strand breaks (DSBs), which can trigger apoptosis (programmed cell death) in sensitive cells that have robust DNA damage surveillance, such as primary human T cells and stem cells [17].

- Proliferation State: Non-dividing or slowly dividing cells have reduced activity of the Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, favoring the more error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway. This limits precise editing and increases the frequency of undesirable indels (insertions/deletions) [18] [19].

- Delivery Stress: Physical delivery methods like electroporation, often required for hard-to-transfect cells, can induce significant cellular stress, reduce viability, and compromise cell function, thereby diminishing editing outcomes [18].

How can I minimize off-target effects in my sensitive cell cultures?

Off-target effects—unintended edits at genomic sites similar to the target sequence—pose significant safety risks. Mitigation requires a multi-faceted approach.

- Use High-Fidelity Nucleases: Consider engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) or alternative nucleases like Cas12f1Super, which demonstrate improved specificity, though sometimes with a potential trade-off in on-target efficiency [19] [20] [21].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Utilize sophisticated design tools to select guide RNAs (gRNAs) with high specificity. Prioritize gRNAs with high GC content and consider chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl analogs) to enhance stability and specificity [21]. Using truncated gRNAs (17-18 nucleotides instead of 20) can also reduce off-target binding [21].

- Choose the Right Cargo and Delivery: Transient delivery methods, such as Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, minimize the time the nuclease is active in the cell, thereby reducing the window for off-target activity. Avoid plasmid DNA which leads to prolonged nuclease expression [22] [21].

What delivery strategies are most effective for sensitive cells?

Efficient delivery is one of the most significant bottlenecks. The goal is to maximize editing efficiency while minimizing cellular toxicity.

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes: Delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and gRNA as an RNP complex is highly recommended for sensitive cells. This method is transient, reducing off-target effects and immune responses, and often achieves faster editing onset compared to nucleic acid-based methods [22] [17].

- Optimized Electroporation: For non-viral delivery, fine-tune electroporation parameters. For example, in primary human T cells, specific pulse codes like DS-137 have been successfully used for RNP delivery with high viability and efficiency [17].

- Viral Vector Alternatives: While AAV and lentiviral vectors are efficient, they have packaging size constraints and can elicit immune responses. Newer non-viral solutions, such as engineered Virus-Like Particles (eVLP) or lipid nanoparticles (LNP), are emerging as promising alternatives for in vivo applications [23] [20].

Table: Comparison of Delivery Methods for Sensitive Cell Types

| Delivery Method | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNP + Electroporation | Fast action, low off-targets, high efficiency in immune cells [22] [17] | Potential cell stress/toxicity from electroporation | Primary T cells, stem cells, ex vivo therapies |

| Virus-Like Particles (eVLP) | High efficiency, transient delivery, improved safety profile vs. viruses [23] | Still an emerging technology, optimization required | Retinal cells, in vivo editing |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | High transduction efficiency, tropism for specific tissues | Small packaging capacity (<4.7 kb), immunogenicity [18] | In vivo gene therapy (requires compact editors) |

| Lentivirus (LV) | Stable integration, infects dividing & non-dividing cells | Risk of insertional mutagenesis, persistent expression [18] | Engineering cell lines, ex vivo cell therapies |

Beyond double-strand breaks, what other on-target damage should I worry about?

Traditional focus has been on small indels, but advanced detection methods have revealed more severe on-target genomic damage that is particularly concerning for clinical applications.

- Structural Variations (SVs): CRISPR editing can lead to large, unintended on-target DNA rearrangements, including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions, chromosomal translocations, and even chromothripsis (a catastrophic shattering and reassembly of chromosomes) [19].

- Exacerbation by Repair Modulators: Using small molecule inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency (e.g., DNA-PKcs inhibitors) can dramatically increase the frequency of these large SVs [19]. It is critical to assess the necessity of such enhancers and validate editing outcomes with long-read sequencing or other structural variant detection assays (e.g., CAST-Seq) [19].

Are there safer alternatives to standard CRISPR-Cas9 for these cells?

Yes, several next-generation editing platforms can circumvent the primary source of genotoxicity—the double-strand break.

- Epigenetic Editors (CRISPRoff/on): These systems use a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to epigenetic modifiers (e.g., DNA methyltransferases or TET demethylases) to turn genes on or off without cutting the DNA. This allows for durable, reversible gene silencing or activation that is maintained through cell division, with significantly reduced cytotoxicity and no observed chromosomal abnormalities [17].

- Prime Editing & Base Editing: These "search-and-replace" systems enable precise nucleotide changes without creating DSBs. They are associated with a much lower risk of generating structural variations and are excellent for correcting point mutations [23] [20].

- SMART Template Design: For knock-in experiments, the "Silently Mutate And Repair Template" (SMART) strategy can significantly improve efficiency. By introducing silent mutations in the repair template's "gap sequence," it prevents the template from re-annealing to the target incorrectly, allowing the use of gRNAs that cut farther from the desired insertion site. This provides more flexibility and higher success rates for precise insertions [22].

The diagram below illustrates the key difference between the standard HDR repair template and the innovative SMART design.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR Editing Outcomes in Key Studies

| Cell Type / Model | Intervention / System | Key Efficiency Metric | Key Safety Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Human T Cells | CRISPRoff (Epigenetic Editing) | Durable silencing (>93% cells) for 28+ days | No cytotoxicity or chromosomal abnormalities | [17] |

| Mouse Retina (in vivo) | SMART Template Design | Up to 2x improvement in knock-in efficiency vs. standard template | Not explicitly measured, but higher precision implied | [22] |

| Human HSPCs (Sickle Cell Model) | Base Editing vs. CRISPR-Cas9 | Higher editing efficiency & reduced sickling | Fewer genotoxicity concerns | [20] |

| Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes | Prime Editing (PE4 system) | 34.8% correction of RBM20 mutation | Phenotypic rescue in post-mitotic cells | [23] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Sensitive Cell Genome Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Reduces off-target edits; crucial for therapeutic safety. | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1 [21] |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer | Boosts homology-directed repair (HDR) rates in challenging cells like stem cells. | Recombinant protein; improves HDR efficiency up to 2-fold [23] |

| CRISPRoff/on System Plasmids | Enables durable gene silencing/activation without DNA breaks. | All-in-one RNA systems available for primary T cells [17] |

| Synthetic gRNA with Modifications | Increases stability and editing efficiency; reduces off-target effects. | Chemically modified gRNAs (e.g., 2'-O-Methyl) [21] |

| RNP Complexes | The gold standard for transient, efficient delivery with low toxicity. | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA [22] [17] |

Advanced Protocol: Epigenetic Silencing in Primary Human T Cells

This protocol outlines a method for stable gene silencing using the CRISPRoff system, which avoids DSBs and is highly effective in sensitive primary cells [17].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Methodology

Component Preparation

- CRISPRoff mRNA: Use a highly optimized, base-modified mRNA (e.g., CRISPRoff 7 mRNA with Cap1 and 1-Me-ps-UTP) for maximum potency and durability in T cells [17].

- sgRNAs: Design a pool of 3-6 sgRNAs targeting within 250 bp downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of your gene of interest, focusing on promoters with CpG islands for robust silencing. Clone them into an appropriate sgRNA-MS2 backbone [17].

Cell Electroporation

- Isolate primary human T cells from donor blood.

- Activate T cells using anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 soluble antibodies for 1-2 days.

- Co-electroporate the CRISPRoff mRNA and the pooled sgRNAs into the activated T cells using a 4D-Nucleofector (or similar system) with a pre-optimized pulse code. The protocol in [17] successfully used pulse code DS-137 with the Lonza P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit.

Post-Transfection Culture

- Culture the electroporated cells in appropriate T cell media with IL-2.

- Restimulate cells every 9-10 days with anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 soluble antibodies to promote division and assess the stability of the epigenetic silencing over multiple cell divisions (e.g., over a 28-day time course).

Validation & Analysis

- Flow Cytometry: Monitor the loss of target cell surface protein expression over time.

- RNA-seq: Confirm specific silencing of the target gene and assess transcriptome-wide specificity.

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Verify the deposition of DNA methylation specifically at the target gene's promoter [17].

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most critical cell line characteristics to check before transfection? The most critical characteristics are the cell type (primary, immortalized, or stem), passage number, health and viability (should be >90%), and confluency at the time of transfection (typically 70-90% for adherent cells) [10] [24] [25]. The cell's origin and biological properties also dictate its response to specific transfection reagents and protocols [10].

Why do I consistently get low transfection efficiency even when following a protocol? Low efficiency is often due to one or more of the following factors [26] [25]:

- Poor DNA quality: DNA should be pure, with an A260/A280 ratio of at least 1.7, and free of contaminants like endotoxins [26] [27].

- Suboptimal cell health: Use low-passage-number cells (generally under 30 passages) and ensure they are free from contamination like mycoplasma [10] [26] [24].

- Incorrect complex formation: Transfection complexes are often best formed in serum-free medium, as serum proteins can interfere [10] [26] [25].

- Wrong reagent:DNA ratio: This ratio is critical and requires optimization for each cell line by testing a range of ratios [27].

How can I reduce high cell mortality after transfection? High cell death can be mitigated by [26] [24] [25]:

- Avoiding reagent toxicity: Optimize the amount of transfection reagent and DNA used; using less than the manufacturer's recommendation can sometimes improve viability [24].

- Ensuring cell readiness: Do not use freshly thawed cells. Passage cells at least 2-3 times after thawing before transfection [27].

- Omitting antibiotics: Antibiotics in the transfection medium can increase cytotoxicity when combined with reagents that increase membrane permeability [10].

- Validating DNA purity: Ensure the DNA is not contaminated, as contaminants are a common cause of toxicity [26].

My cells are hard-to-transfect primary cells. What are my options? For hard-to-transfect cells like primary cells, consider switching delivery methods. Electroporation or nucleofection can be more effective than standard chemical methods [24] [3]. Viral transduction also offers high efficiency for primary cells, though it comes with higher cost and biosafety requirements [25] [3]. Furthermore, using the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) format for CRISPR delivery can enhance efficiency in sensitive cells [3].

Should transfection complexes be prepared in serum-free medium? As a general rule, yes. Serum proteins can interfere with the formation of complexes between cationic transfection reagents and nucleic acids [10] [25]. However, some newer commercial reagents (e.g., Xfect) are specifically designed to be serum-compatible. Always refer to the manufacturer's protocol for your specific reagent [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Transfection Efficiency [26] [25] | Degraded or contaminated DNA | Check DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis and A260/A280 ratio (should be ≥1.7) [26]. |

| Incorrect cell confluency | Plate cells to reach 70-90% confluency at the time of transfection [10] [26]. | |

| Suboptimal reagent:DNA ratio | Systematically test a range of reagent:DNA ratios while keeping DNA amount constant [27]. | |

| Mycoplasma contamination | Routinely test cells for mycoplasma and discard contaminated cultures [10] [24]. | |

| High Cell Mortality [26] [25] | Cytotoxic transfection reagent | Reduce reagent amount or switch to a less cytotoxic reagent (e.g., polymer-based like Xfect) [28] [29]. |

| Antibiotics in medium | Perform transfection in antibiotic-free medium [10]. | |

| Excessive DNA amount | Titrate down the amount of DNA used in the transfection [24] [27]. | |

| Poor cell health pre-transfection | Use low-passage, healthy cells with >90% viability. Passage cells 24 hours pre-transfection [10] [26]. | |

| Inconsistent Results Between Experiments | Variable cell passage number | Use cells within a consistent, low-passage range (e.g., passages 5-20) [10] [24]. |

| Fluctuations in serum quality | Use the same brand and lot of serum throughout a project to minimize variability [10]. | |

| Slight changes in complex formation | Standardize incubation time (e.g., 20-30 min at RT) and conditions for complex formation [27]. |

Quantitative Data for Common Reagents and Cell States

The table below summarizes data on the performance of different reagent types and the impact of cell state, synthesized from the search results.

| Characteristic | Liposomal Reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine 2000) | Cationic Polymer Reagents (e.g., PEI, Xfect) | Physical Methods (e.g., Electroporation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Transfection Efficiency | High for many cell lines [30] [29] | High; >90% in HEK293 reported [28] [29] | Highly efficient, good for hard-to-transfect cells [29] [3] |

| Relative Cytotoxicity | Higher at elevated concentrations [30] | Lower cytotoxicity profile reported for some polymers [28] | Can be high if parameters are not optimized [25] |

| Nucleic Acid Compatibility | DNA, RNA, siRNA [27] | Primarily DNA; some are versatile [27] | DNA, RNA, RNP [3] |

| Cost Factor | High commercial cost [30] | Lower cost; in-house options available [30] | Requires expensive equipment [24] |

| Optimal Cell Confluency | 70-90% (adherent cells) [10] | 60-80% (adherent cells) [27] | Varies by cell type and protocol |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Transfection |

|---|---|

| Cationic Lipids (e.g., DOTAP, DOTMA) | Amphiphilic molecules that form positively charged lipoplexes with nucleic acids, facilitating cellular uptake via endocytosis and endosomal escape [30] [27]. |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., Linear PEI, Xfect) | Synthetic polycations that form polyplexes with nucleic acids. Some, like PEI, facilitate endosomal escape via the "proton sponge" effect [30] [27]. |

| Helper Lipids (e.g., DOPE) | Often mixed with cationic lipids to improve the stability and fusion properties of lipoplexes, enhancing endosomal escape and overall transfection efficiency [30]. |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | A widely used, highly efficient commercial liposomal reagent for delivering both DNA and RNA into a broad variety of cell types, though it can be cytotoxic at high concentrations [30] [29]. |

| TurboFect | A cationic polymer reagent shown in a study to provide superior transfection efficiency in Vero cells compared to other chemical methods and electroporation [29]. |

| Opti-MEM | A reduced-serum medium commonly used for diluting nucleic acids and transfection reagents to form complexes without serum interference [29]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. This format allows for rapid editing and is ideal for hard-to-transfect cells, minimizing off-target effects [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Methodical Approach to Transfection Optimization

This workflow provides a systematic, step-by-step guide to diagnosing and resolving common transfection problems.

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Verify Nucleic Acid Quality: Begin by confirming the purity and integrity of your DNA. Use spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio should be 1.7-1.9) and gel electrophoresis to ensure the DNA is not degraded or contaminated [26] [27].

- Assess Cell Health and Passage Number: Use low-passage cells (recommended less than 30 passages after thawing) that are actively dividing. Cells should be at least 90% viable and allowed to recover for at least 24 hours after passaging before transfection [10] [24] [27].

- Check Cell Confluency: Plate cells so they are 70-90% confluent at the time of transfection. Too few cells can lead to poor growth, while over-confluent cells can cause contact inhibition and reduce uptake [10] [26].

- Optimize Reagent:DNA Ratio: This is a critical parameter. Using a fixed amount of DNA, test a range of transfection reagent volumes to find the optimal ratio that provides the best efficiency with minimal toxicity. Manufacturer protocols are a starting point but often require optimization [24] [27].

- Review Complex Formation Protocol: Form complexes in a serum-free medium like Opti-MEM or PBS. Allow the nucleic acid-reagent mixture to incubate at room temperature for the recommended time (often 20-30 minutes) for optimal complex formation before adding it dropwise to cells [27].

- Consider Alternative Methods: If optimization of chemical transfection fails, especially for hard-to-transfect cells like primaries or stem cells, switch to a more robust method. Electroporation/Nucleofection or viral transduction can be more effective. For CRISPR applications, delivering pre-complexed RNPs can significantly improve editing efficiency and reduce toxicity [25] [3].

Advanced Delivery Methods for CRISPR in Hard-to-Transfect Cells

For researchers aiming to edit hard-to-transfect cell types, selecting the right delivery vector is a critical hurdle. While traditional chemical methods like lipofection are a starting point, they often fall short with sensitive or primary cells. This guide provides a technical deep dive into the world of viral and non-viral vectors, offering troubleshooting and strategic advice to navigate the complexities of advanced gene delivery.

FAQ: Vector Selection and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between transfection and transduction?

- Transfection refers to the introduction of naked or carrier-complexed nucleic acids (DNA, RNA) into eukaryotic cells using chemical (e.g., liposomes, cationic polymers), physical (e.g., electroporation), or other non-viral biological methods. No viral machinery is involved. [31]

- Transduction is a gene delivery method mediated by viral vectors (e.g., lentivirus, adenovirus, AAV), which relies on the virus's natural infection mechanism to enter cells. [31]

Q2: My transfection efficiency is low in hard-to-transfect primary cells. How can I improve it?

Low efficiency in sensitive cells is a common challenge. Systematic troubleshooting is key [31]:

| Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor Cell Health | Use low-passage-number cells (less than 20), ensure they are freshly passaged and in an actively dividing state. [31] [26] |

| Incorrect Reagent Ratio | Optimize the reagent-to-nucleic acid ratio via titration experiments. Use reagents specifically validated for primary cells. [31] |

| High Toxicity | Reduce the reagent concentration or shorten the complex incubation time. Consider switching to low-toxicity reagents or physical methods. [31] |

| Suboptimal Confluency | Transfect at a cell confluency between 60-90%, as this can vary significantly by cell type. [31] [32] [26] |

| Serum Interference | Prepare transfection complexes in serum-free medium, unless using a reagent specifically designed for serum compatibility. [31] [32] |

Q3: Why do my cells die after transfection, and how can I prevent it?

Cell death can stem from several issues. Identifying the symptoms helps pinpoint the cause [31]:

| Cause | Typical Symptoms | Prevention / Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent Toxicity | High cell death within 12-24 hours; cell rounding and detachment. | Reduce reagent amount; choose low-toxicity reagents; use a reagent validated for your specific cell type. [31] |

| Poor Cell Health | Low baseline viability before transfection. | Use healthy, actively dividing cells; avoid using overconfluent or stressed cultures. [31] [26] |

| Contamination | Gradual cell death unrelated to transfection conditions. | Test for mycoplasma/bacterial contamination and replace with clean cultures. [31] |

| Physical Stress (e.g., Electroporation) | Immediate cell swelling, lysis, or vacuolization. | Optimize electroporation parameters (voltage, pulse duration); ensure gentle handling; use a suitable electroporation buffer. [31] [32] |

Q4: When should I use a viral vector over a non-viral method for hard-to-transfect cells?

The choice hinges on your experimental needs and constraints [33]:

- Choose viral vectors when you require high transduction efficiency in challenging cells (e.g., neurons, immune cells), need long-term, stable gene expression (e.g., creating stable cell lines), or are conducting in vivo studies where delivery efficiency is paramount. Lentiviruses (LVs) and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are common choices for this. [34] [35]

- Choose non-viral vectors when safety and low immunogenicity are critical (e.g., for therapeutic applications), you need to deliver large genetic cargo (e.g., massive CRISPR constructs), require the flexibility to re-dose, or need a more scalable and cost-effective manufacturing process. [36] [33] [37] Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are a leading non-viral platform. [34]

Vector Selection Guide: A Technical Comparison

Choosing the right vector requires balancing cargo, application, and safety. The following table provides a structured comparison to guide your decision-making process.

Decision Framework for Vector Selection

Quantitative Vector Comparison

For a detailed, side-by-side comparison of the most common vectors, refer to the table below.

| Vector Type | Cargo Capacity | Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Safety | Best for Hard-to-Transfect... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentivirus (LV) | ~8 kb [35] | Yes (into genome) | High efficiency; stable, long-term expression; infects dividing & non-dividing cells [33] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis; complex manufacturing [34] | Immune cells, stem cells (often used ex vivo) [34] |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | ~4.7 kb [34] [35] | No (episomal) | Low immunogenicity; high safety profile; good for in vivo delivery [34] [33] | Pre-existing immunity; very limited cargo size; high doses can be toxic [38] [34] | Neurons, muscle, retinal cells (in vivo) [34] |

| Adenovirus (AdV) | Up to ~36 kb [35] | No | Very large cargo capacity; high transduction efficiency [35] | High immunogenicity; strong inflammatory response; pre-existing immunity common [33] | Dividing & non-dividing cells (where immune response is manageable) [34] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) | >10 kb (flexible) | No | Low immunogenicity (can re-dose); large cargo; scalable manufacturing; versatile cargo (DNA, RNA, RNP) [34] [36] [37] | Lower gene transfer efficiency; can be trapped in endosomes; mostly liver-targeted (standard LNPs) [34] [33] | A broad range, especially with targeted LNP designs (e.g., SORT nanoparticles for lung, spleen) [35] |

| Electroporation | Flexible | No | Bypasses chemical pathways; direct delivery to cytoplasm/nucleus [32] | Can cause high cell death; requires specialized equipment; optimization intensive [31] [32] | Primary T-cells, hematopoietic stem cells (common for ex vivo therapies) [31] |

Experimental Protocol: Transient vs. Stable Expression

Understanding the workflow for transient and stable gene expression is fundamental to experimental planning. The following diagram outlines the key steps and decision points.

Transient vs. Stable Expression Workflow

Detailed Methodologies

Transient Transfection/Transduction (for rapid results):

- Introduction: Introduce nucleic acids (plasmid DNA, mRNA, or siRNA) via chemical transfection or viral transduction into target cells at 60-80% confluency. [31]

- Expression: The delivered genetic material remains in the cell without integrating into the host genome. Expression is temporary as the nucleic acids degrade or are diluted during cell division. [31]

- Timeline: Protein expression or gene knockdown can typically be assayed within 24 to 96 hours. For siRNA, assess mRNA knockdown at 24-48 hours and protein knockdown at 48-72 hours. [31]

- Key Consideration: No selection step is required. This method is ideal for short-term functional studies or rapid screening. [31]

Stable Cell Line Generation (for long-term studies):

- Introduction: Transfect or transduce cells with a nucleic acid construct that contains your gene of interest and a selectable marker (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene like neomycin or puromycin). [31]

- Integration: For non-viral methods, the DNA must randomly integrate into the host genome. Lentiviral vectors are engineered to efficiently integrate your gene into the host cell's DNA, enabling long-term expression. [31] [33]

- Selection: 48 hours post-transfection, begin applying the appropriate selection antibiotic. Continue selection for 2-3 weeks to eliminate all non-transfected/transduced cells that lack the resistance gene. [31] [32]

- Validation: Confirm stable integration and expression via genomic PCR, Western blot, or long-term monitoring of a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP). [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and materials used in vector-based research for hard-to-transfect cells.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Cationic Lipids / Polymers (e.g., Lipofectamine, PEI) | Chemical transfection reagents that form complexes with nucleic acids, facilitating cellular uptake through endocytosis. Broadly used but can have variable efficiency and toxicity. [31] [33] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic vesicles that encapsulate and protect nucleic acids (mRNA, siRNA, CRISPR RNP). Crucial for in vivo delivery and hard-to-transfect cells, with emerging organ-targeting capabilities (e.g., SORT LNPs). [34] [35] [37] |

| N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) | A targeting ligand conjugated to RNA therapeutics (siRNA, ASO) for highly specific delivery to hepatocytes in the liver, enabling subcutaneous administration for treating liver diseases. [34] |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Short peptide sequences that facilitate the cellular uptake of various molecular cargoes (proteins, nucleic acids). A tool for delivering CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) with low toxicity. [37] |

| Virus-like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered viral capsids that lack viral genetic material. Used as a safer, non-integrating alternative to viral vectors for transient delivery of CRISPR components like base editors. [35] |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of Cas protein and guide RNA. The preferred cargo for CRISPR editing due to immediate activity, high precision, and reduced off-target effects compared to DNA delivery. [35] [36] |

Genetic manipulation of hard-to-transfect cell types, such as primary cells, stem cells, and non-dividing cells, presents a significant bottleneck in therapeutic development and basic research. These cells are often resistant to conventional transfection methods because their cargo must not only cross the plasma membrane but also efficiently reach the nucleus to induce genetic changes. Electroporation, and its advanced counterpart Nucleofection, use controlled electrical pulses to create transient pores in the cell membrane, enabling the direct delivery of macromolecules into the cytoplasm or even directly into the nucleus. Optimizing the electrical parameters of these pulses is the critical factor that balances high transfection efficiency with sufficient cell viability for downstream applications. This guide provides a detailed troubleshooting and optimization framework to overcome the unique challenges associated with editing hard-to-transfect cell types.

Core Concepts: Electroporation vs. Nucleofection

While both electroporation and Nucleofection use electrical pulses for transfection, they are designed for different outcomes, particularly regarding nuclear delivery.

- Electroporation traditionally uses electrical pulses to permeabilize the plasma membrane, allowing cargo to enter the cytoplasm. The subsequent entry of DNA into the nucleus is often a major limiting factor, especially in non-dividing cells [3].

- Nucleofection is a specialized form of electroporation that combines specific electrical pulse parameters with proprietary cell-type-specific reagents. This technology is optimized to facilitate the direct translocation of cargo, such as plasmids or ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), directly into the nucleus [3] [39]. This is a crucial advantage for hard-to-transfect cells that are not actively dividing.

The choice of cargo format also influences the success of nuclear delivery and editing efficiency, as summarized in the table below [3].

Table 1: CRISPR Component Delivery Formats and Their Journeys to the Nucleus

| Cargo Format | Delivery Destination | Subsequent Steps to Achieve Editing | Best Suited Transfection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (Plasmid) | Cytoplasm | Entry into nucleus → Transcription → Translation → RNP formation → Nuclear entry of RNP | Nucleofection for direct nuclear delivery |

| Cas9 mRNA + gRNA | Cytoplasm | Translation of mRNA → RNP formation in cytoplasm → Nuclear entry of RNP | Electroporation or Nucleofection |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Cytoplasm or Nucleus | If delivered to cytoplasm: Nuclear entry of RNP.If delivered to nucleus: Immediate editing. | Nucleofection (for direct nuclear delivery) |

The following diagram illustrates the different cellular pathways taken by these cargo formats.

Optimizing Electrical Parameters: A Systematic Approach

Achieving high efficiency in hard-to-transfect cells requires systematic optimization of electrical parameters. A "Design of Experiments" (DoE) approach, which varies multiple parameters in a structured way, is highly effective. One study using this method on a high-definition microelectrode array achieved 98% transfection efficiency in primary fibroblasts by optimizing five key parameters [40].

Table 2: Key Electrical Parameters for Optimization and Their Effects

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Efficiency & Viability | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Strength (kV/cm) | Voltage across the cuvette gap. | Too high: Excessive cell death.Too low: Inefficient pore formation. | Smaller cells require higher field strength [41]. Adjust voltage for cuvette gap size (e.g., 0.2 cm vs. 0.4 cm) [42]. |

| Pulse Waveform | Shape of the electrical pulse (Exponential Decay vs. Square Wave). | Exponential decay: Common for bacteria, yeast, plant, and insect cells [41].Square wave: Often gentler and preferred for mammalian cells [41]. | Start with the waveform recommended for your cell type. Square waves offer more control over pulse duration [41]. |

| Pulse Duration (ms) | How long the voltage is applied. | Longer durations increase molecular uptake but also increase cell damage [41]. | For square waves, set directly. For exponential decay, it's controlled by the time constant (T). Chilled cells may need longer pulses [41]. |

| Pulse Number | The number of pulses delivered. | Multiple lower-voltage pulses can be gentler than a single high-voltage shock, improving viability in fragile cells [40] [41]. | Varying the pulse number can modulate delivery dosage and protein expression levels [40]. |

| Cell Health & Density | The state and concentration of cells during electroporation. | Low viability or incorrect density drastically reduces outcomes. | Use healthy, log-phase cells. Optimal density is often 1-10 x 10⁶ cells/mL; avoid very high densities [43] [41]. |

The process for systematically optimizing these parameters is shown in the workflow below.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for successfully implementing electroporation and Nucleofection protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electroporation and Nucleofection

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleofector System & Kits | Provides device, cell-type-specific solutions, and pre-optimized protocols for direct nuclear delivery. | The broad-spectrum "Ingenio Solution" is a cost-effective alternative compatible with various electroporators [43]. |

| Specialized Electroporation Buffers | Low-conductivity solutions minimize arcing and improve cell health during and after pulses. | In-house buffers like "Chicabuffers" offer a cost-effective option shown to work with various cell lines and primary cells [39]. |

| Quality Nucleic Acids/RNP | The cargo to be delivered. High purity is essential. | For mRNA, ensure it is capped, polyadenylated, and chemically modified for enhanced stability and translation [44]. For DNA, use high-purity, endotoxin-free preps [43]. |

| Electroporation Cuvettes | Disposable chambers that hold the cell-sample mixture during pulsing. | Choose the correct gap size (e.g., 0.2 cm for 100 µL). Do not reuse cuvettes. Ensure they are dry externally to prevent arcing [43] [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: I consistently observe arcing (a "snap" sound) during electroporation. What should I do? Arcing is often caused by excessive salt in the sample, which increases conductivity [42] [41].

- Desalt your DNA: Use microcolumn purification or ethanol precipitation to remove salts from your nucleic acid preparation [42].

- Check cell density: Overly concentrated cells can contribute to arcing. Try diluting your cell sample [42].

- Ensure cuvettes are dry: Thoroughly wipe the outside of the cuvette, especially if it was on ice, to prevent current traveling along the outside [41].

- Avoid cuvette reuse: Reused cuvettes can have residual debris that causes arcing [43].

Q2: I get high cell viability but very low transfection efficiency. How can I improve this?

- Confirm cell quality: Use cells in an active growth phase and at a consistent, low passage number [43]. Split cells 18-24 hours before electroporation.

- Optimize cell density: The optimal density is cell-type-specific but generally falls between 1-10 x 10⁶ cells/mL [43]. Test a range of densities.

- Verify cargo quality and quantity: Use highly purified, endotoxin-free DNA [43]. For DNA transfection, a final concentration of 5–50 µg/mL is a good starting point for optimization [43].

- Re-optimize electrical parameters: The existing protocol may be suboptimal. Use a systematic (DoE) approach to test a wide range of conditions [40] [45].

Q3: My hard-to-transfect primary cells are dying after Nucleofection. What can I adjust?

- Use a gentle pulse code: If using a Nucleofector device, select a program designed for high viability in sensitive cells.

- Optimize post-transfection care: Cells are fragile immediately after pulsing. Add pre-warmed recovery media immediately and transfer cells to culture vessels quickly. Allow a 24-48 hour recovery period before applying any selection agents [41].

- Titrate cargo amount: Using excessive DNA or RNP can be toxic. Find the minimum amount required for efficient editing [14].

- Consider the RNP format: For CRISPR editing, delivering pre-complexed RNP is often less toxic and more efficient than DNA-based methods in primary cells [3] [14].

Q4: When should I choose mRNA over DNA for transfection? The choice depends on your experimental needs, as summarized below [44].

Table 4: mRNA vs. DNA Transfection Guide

| Use Case | Choose mRNA if... | Choose DNA if... |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | Working with primary, stem, or non-dividing cells. | Using immortalized, dividing cell lines. |

| Speed | You need protein expression within 2-6 hours. | You can wait 12-24 hours for expression. |

| Expression Duration | You require short, controllable, transient expression. | You need sustained expression or stable cell line generation. |

| Safety | Avoiding any risk of genomic integration is critical. | Genomic integration is desired or not a concern. |

Advanced Protocol: CRISPR Editing of Primary Cells using RNP Nucleofection

This protocol is designed for high-efficiency, low-toxicity gene editing in hard-to-transfect primary cells like peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or stem cells, based on established methodologies [3] [39].

Step 1: Prepare the RNP Complex

- Synthesize or purchase high-quality, chemically modified sgRNA and purified Cas9 protein.

- Complex the sgRNA and Cas9 protein at a molar ratio of 3:1 (sgRNA:Cas9) in a sterile microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

Step 2: Harvest and Count Cells

- Harvest the primary cells using gentle methods. For adherent cells, use a mild enzyme like Accutase.

- Wash the cells once in PBS to remove serum and contaminants.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in the appropriate Nucleofector Solution (e.g., SE Cell Line Solution for PBMCs). Do not use antibiotic-containing buffers.

- Count the cells and prepare a suspension at a concentration of 5-10 x 10⁶ cells per 100 µL of solution.

Step 3: Perform Nucleofection

- Combine 100 µL of cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex (e.g., 2-10 µg of RNP). Mix gently by pipetting.

- Transfer the entire mixture into a certified cuvette, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped.

- Cap the cuvette and insert it into the Nucleofector device.

- Run the pre-optimized program for your specific cell type (e.g., "U-014" for human PBMCs).

- Upon completion, you will see a small cell pellet at the bottom of the cuvette.

Step 4: Post-Transfection Recovery

- Immediately after the pulse, add 500 µL of pre-warmed culture medium directly to the cuvette.

- Gently transfer the cells using the provided pipette into a culture plate or flask containing pre-warmed complete medium.

- Place the cells in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂) and do not disturb for at least 24 hours to allow recovery.

- Assess editing efficiency and viability 48-72 hours post-transfection via flow cytometry, genotyping, or other functional assays.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Plasmid DNA (pDNA)

Q1: My plasmid DNA transfection in primary T-cells shows high cytotoxicity and low editing efficiency. What is the cause and how can I mitigate this?

A: This is a common issue when using pDNA in hard-to-transfect cells. The primary causes are:

- Continuous Cas9/gRNA Expression: The plasmid persists and expresses Cas9 protein for extended periods, increasing off-target effects and cellular stress.

- Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) Activation: Bacterial genomic DNA contaminants in the plasmid prep can trigger innate immune responses.

Mitigation Protocol:

- Use High-Purity, Endotoxin-Free Plasmid Kits: Employ plasmid purification kits specifically rated for endotoxin removal.

- Implement a Delivery Wash-Out: Transfect cells, allow a 24-hour window for expression, then trypsinize and wash the cells to remove residual plasmid.

- Utilize a Inducible System: Use a doxycycline-inducible Cas9 plasmid to control the timing and duration of expression precisely.

- Alternative Payload: Switch to RNP complexes for a transient, rapid activity profile that minimizes cytotoxicity.

Q2: How long after pDNA transfection should I assay for editing events?

A: Due to the time required for transcription and translation, editing events occur later than with other methods. Assay editing efficiency 72-96 hours post-transfection. Genotypic analysis (e.g., T7E1 assay, NGS) should be performed after the cells have undergone at least one round of cell division to allow for repair.

Cas9 mRNA

Q3: I am getting poor editing efficiency with Cas9 mRNA in human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). What could be wrong?

A: The main challenges are the instability of mRNA and the need for it to be translated into functional protein.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check mRNA Integrity: Run the mRNA on a denaturing gel to confirm it is intact and not degraded.

- Optimize Transfection Reagent: Screen multiple transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine MessengerMAX, specialized electroporation kits) known to be effective for your cell type.

- Modify the mRNA: Use chemically modified mRNAs (e.g., with 5-methylcytidine and pseudouridine) to reduce innate immune recognition and increase stability.

- Co-deliver gRNA: Ensure the gRNA is being delivered efficiently, typically as a synthetic, chemically modified RNA.

Q4: The Cas9 mRNA I purchased is triggering a strong interferon response in my iPSCs. How can I prevent this?

A: This is a known immunogenicity issue with exogenous RNA.

- Solution: Source synthetic Cas9 mRNA that incorporates modified nucleosides (e.g., pseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine). These modifications evades detection by cellular pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) receptors, thereby dampening the interferon response.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP)

Q5: My RNP complex formation seems inconsistent. What is the optimal protocol for assembling functional RNPs?

A: Consistent RNP formation is critical for high efficiency.

Detailed Protocol:

- Components:

- Recombinant Cas9 protein (commercial source, e.g., IDT, Thermo Fisher).

- Synthetic crRNA and tracrRNA (or a single-guide RNA, sgRNA).

- Assembly:

- If using a two-part system, first anneal the crRNA and tracrRNA to form the gRNA. Combine equimolar amounts (e.g., 1 µM each) in duplex buffer, heat to 95°C for 5 minutes, and cool slowly to room temperature.

- For RNP complex formation, mix the pre-annealed gRNA (or sgRNA) with Cas9 protein at a molar ratio of 1:1 to 1:2 (Cas9:gRNA). A typical starting point is 2 µM Cas9 with 2.4 µM gRNA.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow the RNP to form.

- Delivery: Use immediately for transfection, typically via electroporation (e.g., Neon, Amaxa systems).

Q6: RNP is touted as the best for hard-to-transfect cells, but my editing efficiency in primary neurons is still low. What can I do?

A: While RNP is highly effective, delivery remains the bottleneck.

- Optimize Electroporation Parameters: Systematically test voltage, pulse width, and pulse number using a cell-type specific kit.

- Use a Delivery Enhancer: Incorporate commercial delivery enhancers like TaRGET-1 or other small molecules that temporarily perturb the cell membrane or endosomal vesicles to facilitate RNP escape.

- Verify Protein and gRNA Quality: Ensure the Cas9 protein is fresh, nuclease-free, and the gRNA is HPLC-purified to remove truncated species.

Table 1: Payload Characteristics and Performance

| Feature | Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | Cas9 mRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Activity | Slow (24-48 hrs) | Moderate (12-24 hrs) | Fast (< 4 hrs) |

| Duration of Activity | Long (days-weeks) | Moderate (1-3 days) | Short (< 48 hrs) |

| Typical Editing Efficiency | Low-Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Off-Target Effects | High | Moderate | Low |

| Cytotoxicity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Immunogenicity | High (TLR9) | Moderate (TLR3/7/8) | Low |

| Ease of Use | Simple (familiar) | Moderate | Moderate (requires assembly) |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Best Suited For | Stable cell lines, screening | Cells sensitive to DNA but amenable to RNA | Hard-to-transfect cells (primary, stem, immune) |

Table 2: Recommended Delivery Methods by Payload and Cell Type

| Payload | Easy-to-Transfect (HEK293, HeLa) | Hard-to-Transfect (T-cells, HSCs, Neurons) |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | Lipofection, PEI | Nucleofection |

| Cas9 mRNA | Lipofection (mRNA-specific) | Nucleofection |

| RNP Complex | Lipofection (some cell lines) | Nucleofection (Gold Standard) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: RNP Delivery via Electroporation in Primary Human T-Cells

Method:

- Isolate and Activate T-cells: Isolate PBMCs and activate T-cells with CD3/CD28 beads for 48-72 hours.

- Prepare RNP Complexes: As described in FAQ A5, complex 5 µg of Cas9 protein with 6 µg of sgRNA (1:1.2 molar ratio) in a total volume of 10 µL. Incubate 10 min at room temp.

- Prepare Cells: Harvest activated T-cells, count, and resuspend in the appropriate electroporation buffer (e.g., P3 Primary Cell Solution) at a concentration of 1-2 x 10^7 cells/mL.

- Electroporate: Mix 20 µL of cell suspension with the pre-formed 10 µL RNP complex. Transfer to a certified cuvette. Electroporate using a pre-optimized program (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector, program EO-115).

- Recovery: Immediately add pre-warmed culture medium and transfer cells to a plate. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Analysis: Assess editing efficiency by flow cytometry (if targeting a surface protein) or genomic DNA extraction followed by T7E1 assay or NGS at 48-72 hours post-electroporation.

Protocol 2: Assessing Editing Efficiency via T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay

Method:

- Extract Genomic DNA: 48-72 hours post-editing, harvest and lyse cells. Purify genomic DNA using a commercial kit.

- PCR Amplify Target Locus: Design primers flanking the CRISPR target site (~500-800 bp product). Perform PCR using a high-fidelity polymerase.

- DNA Denaturation and Renaturation: Purify the PCR product. Take 200 ng of the product in a 10 µL volume. Denature at 95°C for 5 minutes, then reanneal by ramping down to 85°C at -2°C/sec, then down to 25°C at -0.1°C/sec. This allows heteroduplex formation if indels are present.

- T7E1 Digestion: Add 1 µL of T7 Endonuclease I enzyme (NEB) to the reannealed DNA and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Analysis: Run the digested product on a 2% agarose gel. Cleaved bands indicate the presence of indel mutations. Efficiency can be quantified using gel analysis software.

Visualization

Diagram 1: CRISPR Payload Activity Timeline

Diagram 2: Payload Mechanism & Immune Activation

Diagram 3: Workflow for Hard-to-Transfect Cell Editing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Vendor/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The core enzyme for genome cutting in RNP delivery. | IDT Alt-R S.p. Cas9, Thermo Fisher TrueCut Cas9 |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic guide RNA with modifications to enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity. | IDT Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA, Synthego |

| Electroporation System | Device for delivering payloads via electrical pulses into hard-to-transfect cells. | Lonza 4D-Nucleofector X Unit, Thermo Fisher Neon |

| Cell-Type Specific Electroporation Kits | Optimized buffers and solutions for specific cell types to maximize viability and efficiency. | Lonza SE Cell Line / P3 Primary Cell Kits |

| Endotoxin-Free Plasmid Prep Kit | For purifying plasmid DNA with minimal contaminating endotoxins that trigger immune responses. | Qiagen EndoFree Plasmid Kits |

| Modified Cas9 mRNA | Synthetic mRNA with base modifications (5mC, ψ) to reduce interferon response and increase translation. | TriLink CleanCap Cas9 mRNA |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Enzyme for detecting indel mutations post-editing via mismatch cleavage. | New England Biolabs |

| Lipofectamine MessengerMAX | A lipid-based transfection reagent optimized for mRNA delivery. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

Editing the genome of hard-to-transfect cell types—such as primary cells, stem cells, and neurons—remains a significant bottleneck in therapeutic development. Among the various strategies employed, the direct nuclear microinjection of CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes represents a precision-based approach that overcomes critical limitations associated with conventional transfection methods. RNP delivery offers distinct advantages, including reduced off-target effects due to transient cellular presence and elimination of viral vector integration risks [46]. When combined with microinjection, this technique enables unparalleled control over dosage and localization, making it particularly valuable for working with sensitive, valuable, or difficult-to-transfect cell samples where bulk delivery methods fail [47].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNP Microinjection Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common RNP Microinjection Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Optimizations |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability | Excessive injection volume/pressure; RNP toxicity; physical membrane damage [47] [48]. | Optimize injection pressure and time to minimize volume [47]. Titrate RNP complex concentration to find the balance between efficiency and toxicity [48]. |

| Inconsistent Editing Efficiency | Variable injection volumes; improper RNP complex assembly; poor nuclear import [47] [46]. | Calibrate injection system using fluorescent dyes to ensure volume precision [47]. Use Cas9 proteins with nuclear localization signals (NLS) to enhance nuclear entry [46]. |

| Clogged Micropipettes | Particulates in RNP solution; protein aggregation [47]. | Centrifuge the RNP solution at high speed before loading to remove aggregates. Use filtered pipettes and clean sample preparation techniques. |

| Low Throughput | Manual, single-cell injection process [47]. | Employ automated cell patterning and injection systems to process cells in arrays, significantly improving throughput [47]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why choose RNP microinjection over viral delivery or electroporation for hard-to-transfect cells?

Each method has its place, but RNP microinjection excels in scenarios demanding precision and minimal risk. Viral delivery can cause persistent Cas9 expression and immune responses [46], while electroporation can be highly toxic to sensitive primary cells [49]. RNP microinjection provides rapitediting onset and quick degradation of the editing machinery, minimizing off-target effects and cellular toxicity. It allows for the selective editing of specific cells within a heterogeneous population, which is impossible with bulk methods [47] [46].

Q2: How do I verify that my RNP complexes are correctly assembled before injection?

A common method is the Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). When the guide RNA binds to the Cas9 protein to form the RNP complex, its migration through a gel is slowed down. A successful assembly is indicated by a band shift compared to the free gRNA lane [49].

Q3: What is a reliable way to quantify the injection volume for reproducibility?

You can calibrate your system by injecting a fluorescent dye (like TRITC-dextran) into water droplets suspended in oil. By measuring the fluorescence intensity of the droplets post-injection and comparing it to a standard curve of known dye concentrations, you can accurately calculate the delivered volume. Studies have shown this method can achieve a high degree of reproducibility (SD-to-Mean ratio of 0.124) [47].

Q4: Can I use this method for other CRISPR applications beyond gene knockout?

Absolutely. The RNP strategy has been successfully adapted for various CRISPR systems. Pre-assembled complexes of base editor proteins (e.g., adenine base editors) with their guide RNA can be microinjected for precise single-base editing without creating double-strand breaks. Similarly, complexes involving dCas9 fused to effector domains can be used for epigenome editing [46] [48].

Quantitative Data and Protocol Optimization

Table 2: Optimized Microinjection Parameters for Precise RNP Delivery

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Value | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Injection Pressure | Calibrated for ~420 fL delivery [47] | Linear control over injection volume; critical for dose-dependent editing. |

| Injection Time | ~100 ms [47] | Works in tandem with pressure to define volume; shorter times require higher pressure. |

| Cell Confluency | Patterned in arrays for single-cell access [47] | Ensures consistent targeting and minimizes damage to neighboring cells. |

| RNP Concentration | e.g., modRNA at 5-100 ng/μL [47] | Higher concentrations can increase editing efficiency but may impact viability. |

| Post-Injection Analysis | 18-48 hours for protein expression [47] | Timeframe to assess initial editing outcomes and protein expression levels. |

Essential Workflow for Single-Cell RNP Microinjection

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for achieving precise single-cell RNP microinjection, from sample preparation to validation.