Strategic Keyword Selection for Scientific Publications: A Guide for Researchers to Boost Visibility and Impact

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on selecting effective keywords to maximize the discoverability and impact of their scientific publications.

Strategic Keyword Selection for Scientific Publications: A Guide for Researchers to Boost Visibility and Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on selecting effective keywords to maximize the discoverability and impact of their scientific publications. It covers the foundational principles of how search engines and academic databases utilize keywords, offers methodological strategies for identifying and applying relevant terms—including the use of controlled vocabularies like MeSH—and addresses common challenges such as low-search-volume terminology and keyword cannibalization. Furthermore, it outlines techniques for validating and comparing keyword effectiveness to ensure optimal article indexing. By implementing these strategies, authors can significantly enhance their work's visibility, readership, and citation potential in an increasingly crowded digital landscape.

Why Keywords Matter: The Foundation of Research Discoverability

How Search Engines and Academic Databases Index Your Work

What does it mean for my work to be "indexed"?

Indexing is the process by which search engines and academic databases systematically collect, organize, and store information about scholarly publications to make them discoverable. When your research paper is indexed, its details (title, authors, abstract, keywords, and sometimes full text) are added to a searchable database, allowing other researchers to find your work through queries. Without proper indexing, your research remains effectively invisible to the scientific community, regardless of its quality or significance.

Why is proper indexing critical for scientific publications?

Effective indexing directly impacts the visibility, citation rate, and ultimate influence of your research. When your work is properly indexed in relevant databases, it reaches the appropriate scientific audience, facilitates knowledge dissemination, and contributes to scholarly conversation in your field. Indexing in prestigious databases like Scopus and Web of Science also serves as a quality marker, as these platforms employ selective criteria for inclusion, which many institutions consider in evaluation and promotion decisions.

Key Platforms and Their Indexing Methods

Major Academic Search Engines

Table 1: Comparison of Major Academic Search Engines

| Platform | Coverage | Indexing Method | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | ~200 million articles [1] | Automated web crawling; includes peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed content [2] | "Cited by" tracking, author profiles, links to full text [1] [2] | Free [2] |

| Semantic Scholar | ~40 million articles [1] | AI-powered analysis of paper content and citations [1] [3] | AI-powered recommendations, visual citation graphs, relevance filtering [3] | Free [3] |

| BASE | ~136 million articles [1] | Focus on open access academic resources [1] | Advanced search with Boolean operators, clear open access labeling [2] | Free [1] |

| CORE | ~136 million articles [1] | Dedicated to open access research [1] | Direct links to full-text PDFs, all content open access [1] | Free [1] |

Major Academic Research Databases

Table 2: Comparison of Major Academic Research Databases

| Platform | Coverage | Indexing Method | Subject Focus | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 90.6 million core records [4] | Selective inclusion with editorial review; citation indexing [4] [3] | Multidisciplinary [4] | Institutional subscription [4] |

| Web of Science | ~100 million items [4] | Selective inclusion with rigorous editorial process; citation indexing [3] | Multidisciplinary [4] | Institutional subscription [4] |

| PubMed | ~35 million citations [4] [5] | MEDLINE curation with NCBI indexing; biomedical focus [4] [3] | Medicine & Life Sciences [4] | Free [4] |

| IEEE Xplore | ~6 million documents [4] [5] | Selective indexing of IEEE publications and standards [3] | Engineering & Computer Science [4] | Subscription [4] |

| ERIC | ~1.6 million items [4] [5] | Education-specific curation with peer-reviewed and grey literature [4] [3] | Education [4] | Free [4] |

| JSTOR | ~12 million items [4] | Archival focus with moving wall for recent content [3] | Humanities & Social Sciences [4] [3] | Subscription with limited free access [4] |

Indexing Pathways for Research Discovery

Optimizing Your Work for Indexing

How can I select optimal keywords to improve indexing?

Effective keyword selection requires strategic consideration of how both automated systems and human searchers will encounter your work. Implement these proven strategies:

- Terminology Analysis: Identify technical terms, conceptual synonyms, and methodological descriptors specific to your field. A study on ReRAM research successfully classified keywords using the Processing-Structure-Properties-Performance (PSPP) relationship, demonstrating how systematic categorization improves discoverability [6].

- Boolean Search Testing: Test potential keywords using Boolean operators in target databases. Search using "(keyword1 OR synonym) AND (keyword2 OR broader_term)" to verify your selected terms return relevant literature [7] [8].

- Natural Language Processing: Utilize tools like spaCy for tokenization and lemmatization to identify key terms from your title and abstract, mirroring how AI-powered platforms like Semantic Scholar analyze content [6].

- Cross-Database Validation: Check keyword effectiveness across multiple platforms (e.g., PubMed for medical terms, IEEE Xplore for engineering) to ensure comprehensive coverage [3].

Keyword Optimization Workflow

What technical elements directly affect indexing?

Search engines and databases prioritize specific metadata fields when indexing content. Ensure these elements are optimized:

- Title Structure: Include primary keywords within the first 5-7 words of your title, as many platforms truncate longer titles in search results.

- Abstract Completeness: Incorporate secondary keywords and methodological terms naturally throughout your abstract, as this text is fully indexed by most platforms.

- Author Affiliation: Consistently use the same institutional naming format across publications to improve author profile aggregation in systems like Scopus and Google Scholar.

- Reference Quality: Include citations from well-indexed publications, as some algorithms use citation networks to determine relevance and thematic classification.

- Digital Identifier Management: Ensure your DOI (Digital Object Identifier) is properly registered and links directly to the definitive version of your work.

Troubleshooting Common Indexing Issues

Why isn't my published work appearing in search results?

If your work isn't appearing in searches, investigate these potential issues:

- Crawl Blocking: Check if your publisher's robots.txt file inadvertently blocks search engine crawlers from indexing content.

- Metadata Inconsistency: Verify that title, author, and abstract metadata matches between your submission and the published version.

- Database Selection: Confirm the database you're searching actually covers your specific discipline—PubMed won't index engineering papers, just as IEEE Xplore won't index education research [3].

- Timing Considerations: Recognize that indexing delays vary significantly—Google Scholar may index within days, while Scopus and Web of Science can take several months after publication.

How can I fix incorrect author attribution in databases?

Author name disambiguation issues are common in academic indexing. Take these corrective actions:

- Platform-Specific Profiles: Claim and update your author profile in Scopus, Google Scholar, and ORCID to consolidate your publications.

- Citation Management: Use author identification tools like ORCID iD and ResearcherID consistently across submissions to create persistent digital identifiers.

- Direct Requests: Contact database customer support with your publication list and identifiers to request merging of duplicate author entries.

What should I do if my work is indexed incorrectly?

Incorrect indexing (wrong title, abstract, or subject categorization) diminishes discoverability. Resolution strategies include:

- Publisher Coordination: Contact your publisher first, as most databases receive metadata directly from publishers rather than authors.

- Database Error Reporting: Use the "Feedback" or "Correct record" features available in most database interfaces to report specific errors.

- Metadata Verification: Check your DOI registration at doi.org to ensure foundational metadata is correct.

Advanced Methodologies for Keyword Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Keyword-Based Research Trend Analysis

This methodology, adapted from a ReRAM research study, systematically analyzes keyword patterns to optimize future publication indexing [6]:

Materials and Research Reagents:

- Bibliographic Data Sources: Crossref API, Web of Science API (for metadata collection)

- Text Processing Tools: spaCy NLP pipeline with "encoreweb_trf" pre-trained model (for keyword extraction)

- Network Analysis Software: Gephi version 0.10 (for keyword network visualization and community detection)

- Computational Environment: Python 3.8+ with pandas, numpy, and matplotlib libraries

Procedure:

- Article Collection: Gather bibliographic data using API queries with field-specific keywords and Boolean operators. Filter results by document type (e.g., "article") and publication date range.

- Keyword Extraction:

- Tokenize article titles using NLP pipeline

- Apply lemmatization to convert tokens to base forms

- Retain only adjectives, nouns, pronouns, and verbs using Universal Part-of-Speech (UPOS) tagging

- Research Structuring:

- Construct keyword co-occurrence matrix counting pairwise frequencies

- Build keyword network with nodes representing keywords and edges representing co-occurrence frequencies

- Apply weighted PageRank algorithm to identify representative keywords

- Segment network using Louvain modularity algorithm to detect keyword communities

- Trend Analysis:

- Categorize keywords using PSPP (Processing-Structure-Properties-Performance) framework

- Analyze temporal frequency patterns of keyword communities

- Identify emerging topics and declining research trends

Validation:

- Compare automated keyword community detection with manual literature review findings

- Verify trend analysis against expert review papers in the target research domain

- Calculate precision and recall metrics for keyword extraction against manually annotated samples

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know which databases are most important for my specific field?

Identify disciplinary databases through these methods: consult your institutional library's subject guides, examine the reference lists of seminal papers in your field (note which databases are cited), and ask senior colleagues about the platforms they use daily. Specialty databases like IEEE Xplore for engineering or ERIC for education research provide more comprehensive coverage for their disciplines than general platforms [3].

Can I request that a database index my work?

Most traditional academic databases do not accept direct author requests for indexing. Inclusion typically occurs through publisher agreements, editorial selection, or society affiliations. However, you can upload your work to repositories like ResearchGate or Academia.edu, which are crawled by Google Scholar, providing an indirect path to broader indexing [5].

Why does my work appear in Google Scholar but not in Scopus?

These platforms have fundamentally different inclusion criteria. Google Scholar automatically indexes scholarly content from across the web with minimal quality screening, while Scopus employs rigorous editorial selection focusing on established, peer-reviewed journals [2] [3]. Scopus coverage is particularly selective in emerging fields or regional publications.

How long does indexing typically take after publication?

Indexing timelines vary significantly: Google Scholar typically indexes within a few days to weeks, especially if posted on institutional repositories. PubMed generally processes within 2-8 weeks after acceptance. Scopus and Web of Science can take 3-6 months due to their selective review processes. Conference proceedings often have longer delays, particularly if awaiting formal publication.

What is the difference between indexing in a database versus a search engine?

Academic databases like Scopus and Web of Science employ curated, selective indexing with quality controls and additional analytical features. Search engines like Google Scholar use automated crawling with broader coverage but less quality assessment. Database indexing often carries more prestige in academic evaluations, while search engine indexing provides broader accessibility [7] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Indexing Optimization

Table 3: Essential Tools for Indexing Management and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Indexing Research | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| spaCy NLP Pipeline | Natural language processing | Keyword extraction from titles and abstracts [6] | Open source |

| Gephi | Network visualization and analysis | Keyword co-occurrence network mapping [6] | Open source |

| Google Search Console | Website indexing monitoring | Tracking institutional repository indexing status [9] | Free |

| Bing Webmaster Tools | Search engine indexing | Monitoring IndexNow protocol implementation [9] | Free |

| ORCID | Author identification | Persistent digital identifier to disambiguate authors [3] | Free |

| Paperpile/Reference Managers | Citation management | Organizing references and generating bibliographies [1] [4] | Freemium |

| Boolean Operators | Search logic construction | Testing keyword effectiveness across databases [7] [8] | Built-in to databases |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Keyword Issues in Scientific Publishing

Q1: My paper is indexed in major databases, but it is not being discovered in literature searches. What is the most likely cause? A: The most probable cause is a mismatch between the terminology in your title/abstract/keywords and the search terms used by other researchers. If your paper does not contain the most common, recognized phrases for your concept, it will be filtered out of search results, no matter its quality [10]. For instance, using "avian" instead of the more common "bird," or a highly specific, novel acronym instead of the established term, can significantly reduce discoverability [10] [11].

Q2: I am using relevant keywords, but they are not driving traffic. How can I improve this? A: The issue likely lies in keyword placement and specificity. Search engines give disproportionate weight to terms in the title and the first 1-2 sentences of your abstract [12] [10]. Furthermore, keywords should be specific "key phrases" rather than single, generic words [12].

- Inefficient Approach: Using generic keywords like "cancer risk," "ultrasound," or "gastroenterology" for a paper on gallbladder polyps [12].

- Optimized Approach: Using specific key phrases like "gallbladder cancer risk," "polyp growth rate," and "neoplastic polyps" [12].

Q3: What is the ideal length for a title and abstract to maximize discoverability? A:

- Title: Keep it short and simple. The most important 1-2 keywords should be within the first 65 characters to avoid being truncated in search engine results [12]. Excessively long titles (>20 words) can fare poorly [10].

- Abstract: While journals often impose strict word limits, surveys show that authors frequently exhaust them, particularly those under 250 words, suggesting guidelines may be overly restrictive [10]. Where possible, use a structured abstract to naturally incorporate key terms and ensure the most important keywords and findings are in the first two sentences [12] [10].

Q4: How does keyword choice affect my paper's citation count? A: Discoverability is the first step toward citation. A paper cannot be cited if it is not found [10]. Using common terminology from your field makes your work more likely to appear in the initial searches conducted by researchers, including those performing systematic reviews and meta-analyses [10]. Papers whose abstracts contain more frequently used terms have been associated with increased citation rates [10]. Furthermore, appearing in more search results through strategic keyword use amplifies your readership base, which is a direct precursor to earning more citations [12] [10].

Experimental Protocol: A Method for Keyword Selection and Analysis

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for selecting optimal keywords for a scientific manuscript, based on quantitative analysis of the existing literature [10] [6].

1. Objective: To identify the most effective and high-impact keywords for a manuscript by analyzing terminology in the existing scientific literature.

2. Materials and Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Bibliographic Database (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed) | To collect a representative sample of literature from your specific research field. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) Tool | To automatically tokenize and extract keywords from article titles and/or abstracts. Tools like the spaCy library can be used for this [6]. |

| Network Analysis Software (e.g., Gephi) | To construct and visualize a keyword co-occurrence network, helping to identify central and community-specific terms [6]. |

| Google Trends / Google Keyword Planner | To validate the commonality of selected keywords and analyze their search volume trends [12] [13]. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Article Collection. Using your bibliographic database of choice, perform a search for articles highly related to your research topic. Use a combination of device names, mechanisms, and application areas. Filter the results to include relevant article types and a suitable publication year range [6].

- Step 2: Keyword Extraction. Extract the titles and abstracts of the collected articles. Use an NLP pipeline (like spaCy's

en_core_web_trf) to tokenize the text, lemmatize words (convert to base form), and filter for specific parts of speech (e.g., adjectives, nouns) to create a list of candidate keywords [6]. - Step 3: Research Structuring.

- Build a keyword co-occurrence matrix by counting how often each keyword pair appears together in the same article title or abstract [6].

- Use network analysis software to create a graph where nodes are keywords and edges represent co-occurrence [6].

- Apply a modularity algorithm (e.g., Louvain method) to identify communities of keywords that represent different sub-fields or themes within your research area [6].

- Step 4: Keyword Selection and Validation.

- From the network, identify the highest-ranking keywords using metrics like PageRank [6].

- Categorize these keywords conceptually. A useful framework is the Processing-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) relationship, common in materials science and adaptable to other fields [6].

- Validate your final shortlist by checking search volume and trend data in tools like Google Keyword Planner or Google Trends [12] [13].

Keyword Optimization Workflow and Impact

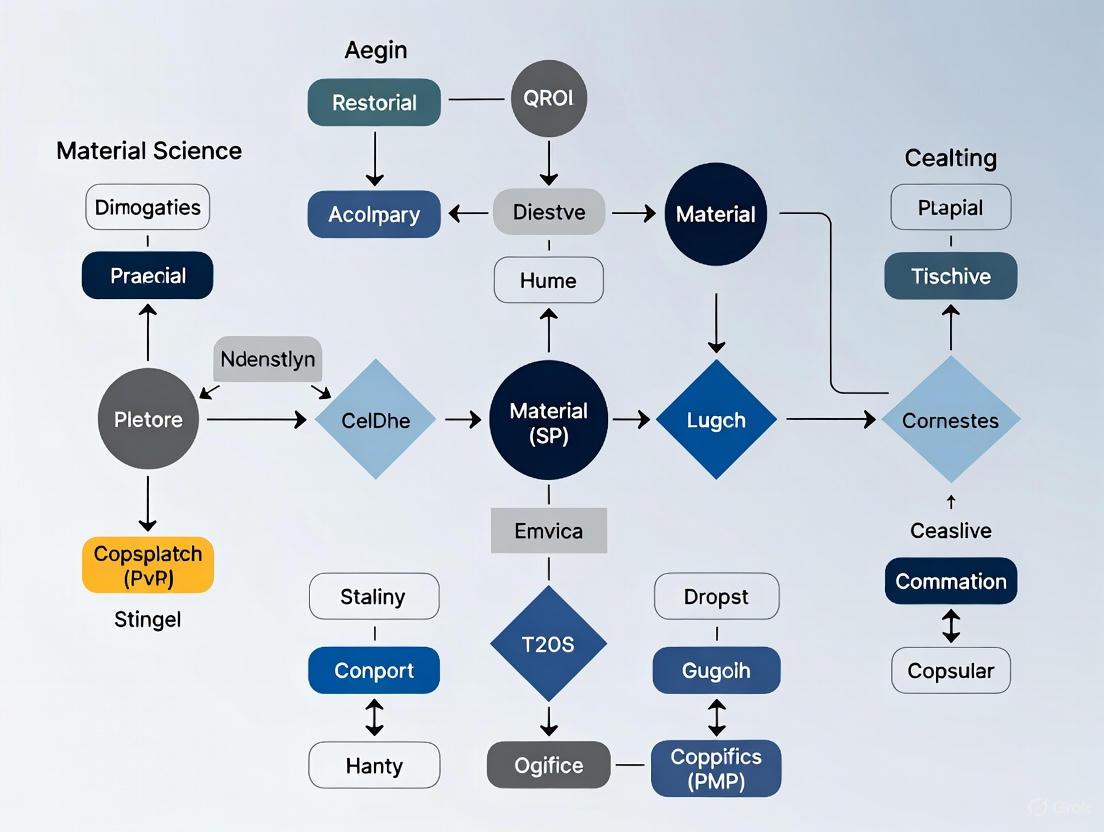

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between systematic keyword optimization and its ultimate impact on research reach and influence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Keyword Research Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Best For | Key Metric Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar [10] | Scanning titles/abstracts of related papers. | Identifying common terminology used in your field. | N/A (Qualitative analysis) |

| Google Keyword Planner [13] [14] | Keyword discovery and volume forecasting. | Validating search volume and competition for key phrases. | Search volume, Competition |

| Google Trends [12] [14] | Analyzing keyword popularity over time. | Identifying trending terms and seasonal patterns. | Interest over time |

| Semrush [15] [13] | Advanced SEO and competitive analysis. | In-depth analysis of keyword difficulty and SERP features. | Keyword Difficulty, SERP Features |

| spaCy (NLP library) [6] | Automated text processing and keyword extraction. | Systematic, large-scale keyword extraction from literature. | N/A (Data processing) |

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering search intent is a critical skill that extends far beyond general search engine optimization (SEO). It is the foundational step in structuring scientific literature reviews, identifying research gaps, and ensuring your published work is discoverable by the right peers and platforms. In 2025, with the rise of AI-powered search engines and AI-generated summaries in academic databases, understanding the nuanced "why" behind a search query is more important than ever for navigating the vast landscape of scientific publications [16]. This guide provides troubleshooting assistance for common challenges in research and publication, all framed within the strategic context of selecting effective keywords by understanding search intent.

FAQs on Search Intent and Keyword Selection

1. What is search intent and why is it critical for scientific publication research?

Search intent refers to the underlying goal or purpose behind a user's search query. In scientific research, it helps you create content and select keywords that answer not just the query, but the context and expectations behind it [16]. For researchers, aligning your keyword strategy with search intent is essential for ensuring your publications are discovered in literature reviews, correctly categorized by academic databases, and surfaced in AI-powered research tools.

2. What are the common types of search intent I should know?

Search intent is typically categorized into three main types, each with distinct characteristics [17]:

- Informational Intent (KNOW): The searcher is looking for answers, information, or knowledge. Examples include "how does CRISPR-Cas9 work?" or "protocol for Western blotting." These often constitute up to 80% of all searches [17].

- Commercial/Transactional Intent (DO): The searcher aims to complete a transaction or investigate a specific product or service. In a research context, this could be "buy Taq polymerase" or "compare NGS sequencing services."

- Navigational Intent (GO): The searcher is trying to reach a specific website or resource. Examples are "National Center for Biotechnology Information" or "Nature journal homepage."

3. How can I identify the search intent behind a keyword for my research?

Analyze the search engine results page (SERP) for that keyword. The type of content that ranks highly (e.g., review articles, product pages, institutional websites) strongly indicates the dominant search intent [17]. Additionally, use SEO tools like Semrush's Keyword Overview, which often tags search queries by intent category [18] [17].

4. How has search intent evolved with the advent of AI in search?

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Fixing Poor Keyword Selection and Low Research Visibility

Problem: Your scientific publications or research queries are not yielding relevant results, leading to missed relevant literature or low discoverability of your own work.

Diagnosis and Solution

| Step | Action | Details & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify | Define your research objective and audience. | Are you writing a review article (informational) or searching for a specific reagent (transactional)? Your goal dictates the keywords. [17] |

| 2. Diagnose | Analyze keyword intent and competition. | Use tools like Semrush's Keyword Overview to check search volume and keyword difficulty. For scientific terms, use databases like PubMed or Google Scholar to see common terminology. [18] |

| 3. Implement | Structure content for intent and AI. | Use clear, topic-rich headings (H1, H2). Pack content with factual density (data, citations). Use schema markup (FAQ, HowTo) to control how your summary appears. [16] |

| 4. Verify | Test and refine your keyword strategy. | Perform a new search with your selected keywords. Are the results relevant? Use academic alert systems to monitor if your published work is being found via new keyword combinations. |

Keyword Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for analyzing and selecting keywords based on search intent, tailored for scientific research.

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Resolving Issues in Experimental Research

Problem: An experiment, such as PCR or bacterial transformation, has failed to yield the expected results, requiring systematic investigation.

Diagnosis and Solution

| Step | Action | Application Example: No PCR Product [19] |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify | Clearly state the problem without assuming the cause. | "No PCR product is detected on the agarose gel, but the DNA ladder is visible." |

| 2. List Causes | Brainstorm all possible explanations. | Taq polymerase, MgCl2 concentration, buffer, dNTPs, primers, DNA template quality, PCR cycling parameters. |

| 3. Collect Data | Review controls, storage conditions, and procedures. | Check if positive control worked. Verify kit expiration and storage. Review lab notebook for procedure deviations. |

| 4. Eliminate | Rule out causes based on collected data. | If controls worked and kit was valid, eliminate them as causes. |

| 5. Experiment | Design tests for remaining possible causes. | Run DNA samples on a gel to check for degradation; measure DNA concentration. |

| 6. Identify | Conclude the root cause and implement a fix. | Identify low DNA template concentration as the cause. Re-run PCR with optimized template concentration. |

Experimental Troubleshooting Logic

The diagram below outlines the logical process for diagnosing and resolving common experimental failures in the laboratory.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions, which are fundamental to the experiments referenced in the troubleshooting guides.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | A heat-stable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification. [19] |

| Competent Cells | Specially prepared bacterial cells (e.g., E. coli DH5α) that can uptake foreign plasmid DNA during bacterial transformation. [19] |

| dNTPs (Deoxynucleotide Triphosphates) | The building blocks (A, T, C, G) used by DNA polymerase to synthesize a new DNA strand. [19] |

| Selection Antibiotic | An antibiotic (e.g., Ampicillin, Kanamycin) added to growth media to select for only those bacteria that have successfully incorporated a plasmid containing the corresponding resistance gene. [19] |

| Plasmid DNA | A small, circular, double-stranded DNA molecule that is used as a vector to carry a gene of interest into a host organism. [19] |

Data and Statistics on Search Behavior

Understanding broader search trends is vital for framing your research in a discoverable way. The table below summarizes key statistics that highlight the evolving nature of search, particularly the importance of intent and the rise of AI.

| Search Trend or Feature | Statistic / Fact | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-Click Searches | ~27% of U.S. searches end without a click to a website. The trend is increasing. [16] | Your abstract and keywords must be compelling enough to convey core findings directly in search summaries. |

| AI Overview Source | About 58% of AI-generated summaries pull content from the top 10 traditional search results. [16] | Foundational SEO and sound keyword strategy remain critical for visibility in new AI-driven interfaces. |

| Informational Intent | Comprises roughly 80% of all search queries. [17] | Review articles, methodological papers, and foundational knowledge have a high potential for discoverability. |

| Local/Contextual Intent | 76% of mobile searches have local or contextual intent. [16] | For researchers, this underscores the need to include context-specific keywords (e.g., organism studied, specific technique variant). |

In the digital age, where millions of scholarly articles are published each year, ensuring your research is discoverable is a critical component of academic success [20]. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is the practice of making your work more visible to search engines and, by extension, to other researchers, scientists, and professionals in your field. For academia, this does not involve commercial tactics but focuses on the strategic use of keywords and key phrases—the specific words and phrases that potential readers use when searching for literature in online databases like Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus [21] [20]. A well-optimized paper is more likely to be found, read, and cited, thereby increasing the impact of your research [21].

This guide answers common questions and provides troubleshooting advice for integrating SEO principles into your scientific publications, directly supporting the broader objective of selecting effective keywords for research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the difference between a 'keyword' and a 'key phrase' in academic searching?

- A: A keyword is a single word (e.g., "oncology") that represents a core concept of your research. A key phrase (or long-tail keyword) is a string of multiple words that forms a more specific search query (e.g., "targeted cancer therapy for glioblastoma") [22]. Key phrases are often more valuable for academic SEO because they align more closely with how researchers conduct precise, focused searches, leading to more qualified readers finding your paper [23] [22].

FAQ 2: Why are my carefully chosen keywords not helping my paper appear in search results?

- A: This common issue can stem from several factors. The most likely causes are:

- Poor Integration: Keywords must be strategically placed in the title, abstract, and full text of your manuscript, not just listed in the metadata. Search engines index this content to understand your paper's topics [24] [21].

- Ignoring Search Intent: Your keywords may not match the actual terms your target audience uses. Using overly technical jargon or acronyms that are not widely adopted can limit discoverability [24] [21].

- High Competition: You may be using keywords that are too broad and generic (e.g., "cell biology"), making it difficult for your paper to rank highly in search results against thousands of others [20].

FAQ 3: Are keywords still relevant with modern search engines that scan full text?

- A: Yes, absolutely. While modern search engines are sophisticated, the title, abstract, and author-provided keywords are given significant weight in classification and ranking algorithms [21] [25]. They help journal editors and database indexers correctly categorize your work, ensuring it appears for the most relevant searches [24].

FAQ 4: Should I create new keywords for a novel technique or discovery?

- A: With caution. If you have developed a genuinely new technique, discovered a new gene, or coined a new term central to your field, using it as a keyword can be highly beneficial in the long term [20]. However, you should balance this with well-established terms to ensure your paper is discoverable immediately upon publication.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Keyword Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Discoverability | Paper does not appear in relevant database searches. | Include primary keywords in your title and abstract. Use synonyms and broader/narrower terms in your keyword list [21]. |

| Irrelevant Search Matches | Your paper is found for unrelated searches. | Choose more specific key phrases. "Chronic liver failure" yields better matches than "liver" [20]. Avoid vague, standalone terms [21]. |

| Missing Target Audience | Your paper is not found by specialists in your sub-field. | Use standardized vocabularies like MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) for biomedical research or discipline-specific thesauri [20] [25]. |

| Keyword List Overload | You have too many potential keywords and don't know how to prioritize. | Apply the "Telescope and Microscope" method: allocate keywords to cover the wide scope, narrow focus, study description, unique methods, and anticipated SEO terms [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Methodology for Keyword Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step, repeatable methodology for identifying and selecting the optimal keywords for a research manuscript.

1. Identify Core Concepts: List your study's main elements: central topic, population/sample, methodology, key variables, and outcomes [21] [20]. From this, extract 5-8 core phrases.

2. Analyze Journal Guidelines and Competitors: Check your target journal's author instructions for keyword rules [20]. Analyze keywords from 5-10 recently published articles in that journal on a similar topic to understand standard terminology [21].

3. Brainstorm and Expand Terms: For each core concept, list synonyms, related terms, broader categories, and narrower sub-categories. Use tools like Google Scholar, PubMed's MeSH database, or Web of Science to find variant terminology [21] [20].

4. Analyze and Prioritize: Map your expanded list against the "Telescope and Microscope" framework to ensure a balanced portfolio [25]. Prioritize terms that are specific, relevant, and likely to be used by your peers in searches.

5. Validate and Finalize: Use Google Scholar's search preview to test your final keywords. Ensure they are integrated naturally into your title and abstract [24] [21].

The logical flow of this methodology is outlined in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Keyword Analysis

The following tools are essential for conducting effective keyword research in an academic context.

| Tool or Resource | Function in Keyword Research |

|---|---|

| PubMed / MeSH | Provides a standardized, controlled vocabulary (thesaurus) for life science and biomedical keywords, ensuring consistent indexing [20]. |

| Google Scholar | Reveals common terminology and keyword usage patterns across a vast corpus of scholarly literature [21] [20]. |

| Web of Science / Scopus | Disciplinary databases that show keywords used in high-impact journals and allow for analysis of trending terms [21]. |

| Journal Author Guidelines | Provides specific requirements for the number, format, and sometimes the source of keywords for a particular publication [20]. |

Data Presentation: Key Metrics for SEO Keyword Analysis

While search volume is a key metric in general SEO, academic keyword selection focuses more on relevance and specificity. The following table summarizes core concepts.

| Metric | Role in Academic SEO | Strategic Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Search Volume | Indicates how often a term is queried. | High-volume terms are competitive; balance with specific, lower-volume key phrases [23]. |

| Keyword Difficulty | Reflects how hard it is to rank for a term. | Broad terms (e.g., "cancer") have high difficulty. Specific phrases (e.g., "MET exon 14 skipping NSCLC") have low difficulty [23]. |

| Search Intent | The goal behind a search (informational, navigational). | Most academic searches are informational. Ensure your title/abstract clearly states your findings to satisfy this intent [26]. |

The relationships between keyword scope, competition, and strategic value are visualized below.

How to Choose Powerful Keywords: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Why Can't Other Researchers Find My Paper?

A common and frustrating issue in research is when your published paper is not discovered or cited by other scientists. This often occurs not because of the quality of your work, but due to ineffective keyword selection and poor framing of the paper's core concepts [10]. When the essential components of your study—the Topic, Population, Methods, and Outcomes—are not clearly defined and integrated into your title, abstract, and keywords, search engines and databases cannot properly index your work, leading to a "discoverability crisis" [10].

This guide will help you troubleshoot this issue by providing a systematic approach to identifying and articulating these core concepts.

Your Troubleshooting Guide for Paper Discoverability

Follow this structured process to diagnose and resolve common problems that hinder your paper's visibility.

Understanding the Problem

The first step is to ensure you fully understand what makes a paper discoverable.

- Ask Good Questions: To pinpoint the discoverability issue, ask yourself:

- "If I were another researcher, what exact terms would I type into a database to find a paper like mine?" [27]

- "Does my title and abstract clearly state the topic, the studied population, the methods used, and the key outcomes?" [28]

- "Have I used full phrases instead of ambiguous acronyms?" [27] For example, use "Health Maintenance Organization" instead of "HMO".

- Gather Information: Analyze highly-cited papers in your field. Scrutinize their titles, abstracts, and keyword sections to identify the terminology they use to describe their core concepts [10].

- Reproduce the Issue: Try to find your own paper (or a similar one) using a keyword search in a database like Scopus or Google Scholar. If it doesn't appear on the first page of results, you have identified a discoverability problem [10].

At this stage, you should be able to clearly articulate the main subject of your research and the specific terms that should lead others to it.

Isolating the Issue

Now, narrow down the root cause. Why is your paper hard to find?

- Remove Complexity: Simplify your search. If your topic is "thermal tolerance of Pogona vitticeps," the issue might be that the keyword "reptile" is more common than the specific species name. A broader context can increase appeal [10].

- Change One Thing at a Time: Test different keyword combinations.

- Test 1: Search using only your Topic (e.g., "thermal tolerance").

- Test 2: Search using your Topic + Population (e.g., "thermal tolerance reptile").

- Test 3: Search using your Topic + Methods (e.g., "thermal tolerance metabolic theory"). This will help you identify which core concept is missing or poorly defined in your own metadata.

- Compare to a Working Version: Look at a paper that is highly discoverable in your field. Compare how its title and abstract integrate key terms related to its population, methods, and outcomes against your own. Spot the differences in terminology and structure [29].

Finding a Fix or Workaround

Once you've isolated the issues, apply these solutions to make your paper more discoverable.

- Craft a Unique and Descriptive Title: Your title should be a concise summary of your main point. It should be descriptive and informative, accurately reflecting your study's scope without inflating it [10] [30].

- Structure Your Abstract Around Core Concepts: Use a structured abstract to ensure you include key terms for your Topic, Population, Methods, and Outcomes. Place the most important and common terms at the beginning of the abstract, as some search engines may not display the full text [10].

Select Strategic Keywords: Keywords are critical for database indexing. Follow these guidelines [27]:

- Categorize your work as a whole; focus on major concepts that cover at least 20% of your paper.

- Use 6-8 keywords or keyword phrases.

- Capitalize only the first letter of the first word in a phrase (e.g., "Business administration").

- Avoid redundancy with terms already in your title and abstract.

Test It Out: Before submission, run your final title and abstract through the same search tests. Ask a colleague to read your abstract and list what they think the key keywords should be.

- Fix for Future Papers: Document what you learned. Keep a list of effective keywords and title structures for your research area to streamline the process for your next manuscript [29].

Key Data for Discoverability

The tables below summarize quantitative data and best practices to guide your keyword strategy.

Table 1: Analysis of Common Discoverability Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Symptom | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly Specific Title [10] | Paper receives few citations; narrow audience appeal. | Frame findings in a broader context while remaining accurate. |

| Abstract Lacks Key Terms [10] | Paper is indexed but does not appear in relevant searches. | Use a structured abstract and place common terminology at the beginning. |

| Redundant Keywords [10] | Wasted keyword slots that do not improve search ranking. | Ensure keywords add new, relevant terms not already in the title/abstract. |

| Use of Uncommon Jargon [10] | Paper is missed by researchers using more standard terminology. | Use the most common and frequently used terms in your field. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Paper Discoverability

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Descriptive Title | Serves as the primary marketing component and first point of engagement for readers; must accurately convey the paper's content and scope [10]. |

| Structured Abstract | Provides a concise summary of the entire paper, allowing for the strategic placement of key terms related to topic, population, methods, and outcomes [10]. |

| Strategic Keywords | Acts as a direct channel to search engine algorithms, categorizing your work and ensuring it appears in relevant database searches [10] [27]. |

| Literature Review Tools | Helps identify the most common and impactful terminology used in prior published research, which should be mirrored in your own work [10]. |

Your Research Workflow: From Concept to Discovery

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for identifying your paper's core concepts and integrating them into your manuscript to maximize discoverability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How many keywords should I use? A: Most guidelines recommend using between 6 and 8 keywords. Avoid using fewer than 5, as this may not adequately cover the major concepts of your work [27].

Q: Should I use acronyms in my keywords? A: No. Use full phrases rather than acronyms or abbreviations to ensure your paper is found by researchers who may not be familiar with the acronym. For example, use "Health Maintenance Organization" instead of "HMO" [27].

Q: What is the biggest mistake authors make with keywords? A: The most common mistake is keyword redundancy, where authors select terms that already appear in the title or abstract. This wastes a valuable opportunity to add new, relevant search terms that can categorize the paper for different audiences [10].

Q: How long should my title be? A: There is no strict rule, but avoid exceptionally long titles (e.g., over 20 words). While the relationship between title length and citations is weak, very long titles may be trimmed in search engine results, impeding discovery [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is MeSH and why is it critical for my research? MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) is a controlled vocabulary thesaurus created by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) [31] [32]. It is used for indexing, cataloging, and searching biomedical and health-related information in databases like MEDLINE/PubMed [31] [33]. Using MeSH ensures you find all articles on a topic, regardless of the synonyms or terminology different authors use (e.g., searching "Myocardial Infarction" will also find articles mentioning "heart attack") [33]. This significantly improves the precision and recall of your literature searches.

My saved PubMed search is suddenly retrieving fewer results. What happened? This is a common issue after the NLM's annual MeSH update. Each year, terms are added, deleted, or replaced to reflect scientific discovery [34]. If a MeSH term in your saved search strategy was deleted or replaced, it can break your search. To fix this, run your search and check the "Details" section in Advanced Search for errors highlighted in red. Then, consult the NLM's "What's New in MeSH" and "MeSH Replace Report" to identify new or replaced terms to update your strategy [34].

How do I find the correct MeSH term for my topic? Use the MeSH database accessible from the PubMed homepage [33]. Type your concept (e.g., "shin splints") into the search box. The database will return the official MeSH term (e.g., "Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome") along with its definition and position in the hierarchical tree structure [32]. You can also examine the "MeSH terms" section of a known relevant article in PubMed to identify appropriate headings [33].

What is the difference between searching with [MeSH] and [Publication Type] tags? The

[MeSH]tag is used for the subject content of an article. The[Publication Type](PT) tag describes the form of the publication, such as "Clinical Trial" or "Review" [35] [34]. Using the correct tag is vital. For example, searching for "Network Meta-Analysis"[MeSH] will find articles about the methodology, while "Network Meta-Analysis"[Publication Type] will find articles that are network meta-analyses [34].A new, highly relevant MeSH term was just introduced. How do I find older literature on that concept? The NLM typically does not retroactively re-index older MEDLINE citations with new MeSH terms [34]. To find older literature, consult the MeSH database entry for the new term, which often lists "Previous Indexing" terms. Use these older MeSH terms or consider searching for the next broader term in the MeSH hierarchy to ensure a comprehensive search [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete Search Results Due to Evolving Terminology

Issue: Your search fails to retrieve key papers because you are only using outdated or common-language terms, missing articles indexed with newer, more precise MeSH headings.

Solution:

- Identify Current Terminology: Use the MeSH Browser to find the official, current heading for your concept [31] [32].

- Account for Annual Changes: Before re-running a saved search for a systematic review, check the NLM's "Annual MeSH Processing" page for the current year to identify any added, deleted, or replaced terms that affect your strategy [31] [34].

- Exploit the Hierarchy: Use the MeSH tree to find all relevant narrower terms. When you search a MeSH term, PubMed automatically includes all more specific terms nested beneath it in the hierarchy by default [33].

Table: Selected MeSH Terminology Changes (2025 Update)

| Change Type | Old Term | 2025 New Term | Rationale/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changed Heading | Condoms, Female | Single-Use Internal Condom | Move to more precise and descriptive terminology [35]. |

| Changed Heading | Sex Reassignment Surgery | Gender-Affirming Surgery | Reflects updated and more inclusive clinical language [35]. |

| Changed Heading | Pregnant Women | Pregnant People | Adopts more inclusive gender-neutral terminology [35]. |

| Replaced Term | Pregnancy-Related Mortality | Use: Maternal Mortality | Consolidation and clarification of related concepts [35]. |

Problem: Managing Complex Searches with Multiple Concepts

Issue: A research question involving several elements (e.g., drug, disease, mechanism) leads to an overly broad or poorly organized search strategy.

Solution:

- Break Down Concepts: Deconstruct your research question into individual core concepts (e.g., "CNN-DDI," "drug-drug interactions," "convolutional neural networks") [36].

- Build in the MeSH Database: For each concept, search the MeSH database. Select the most appropriate term and, if needed, add subheadings to focus your search (e.g., "/diagnosis" or "/drug therapy") [33].

- Combine with Boolean Logic: Use the "Search Builder" in PubMed's Advanced Search to combine your refined MeSH searches with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT). For comprehensive results, also incorporate textword searches of titles and abstracts to catch very recent articles not yet fully indexed with MeSH [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Methodology for Building a Robust MeSH Search Strategy

This protocol outlines the steps to construct a comprehensive and reproducible literature search for a biomedical research project, such as investigating computational methods for predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs) [36].

- Conceptualization: Clearly define the research scope. Example: "Identify studies that use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to predict drug-drug interactions."

- Vocabulary Mapping: Use the MeSH database to map core concepts to controlled terms.

- Concept 1: "convolutional neural network" → MeSH: "Neural Networks, Computer"

- Concept 2: "drug-drug interactions" → MeSH: "Drug Interactions"

- Strategy Assembly:

- Search

"Neural Networks, Computer"[MeSH]and add to Search Builder. - Search

"Drug Interactions"[MeSH]and add to Search Builder. - Combine both sets using

AND.

- Search

- Validation and Expansion:

- Run the search and identify a few known, relevant articles. Verify they are in your results.

- Check the MeSH terms assigned to these relevant articles for any you may have missed [33].

- Supplement with a textword search:

(convolutional NEAR/2 network*) OR CNN) AND (ddi OR "drug-drug interaction*")in Title/Abstract fields. - Combine the MeSH results and the textword results with

OR.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MeSH-Based Literature Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| MeSH Database | The primary tool for finding, defining, and understanding Medical Subject Headings for use in search strategies [33]. |

| PubMed Advanced Search | Interface for building, combining, and managing complex searches using MeSH terms and Boolean operators [33]. |

| NLM MeSH Browser | Provides detailed information on each heading, including scope notes, tree structures, and entry vocabulary [31]. |

| NLM Classification | A system for organizing library materials in medicine and related sciences, related to the MeSH vocabulary [31]. |

Protocol 2: Methodology for Updating a Systematic Review Search

This protocol ensures a saved search remains current and accurate despite annual changes to the MeSH vocabulary.

- Baseline Assessment: Run your saved search strategy and note the number of results. Check for errors in the "Search Details" [34].

- Identify New & Changed Terms: Consult the latest "Annual MeSH Processing" page and "New MeSH Descriptors" list [31] [34]. For example, for a 2025 update, you would note new AI-related terms and changed terms like "Gender-Affirming Surgery."

- Revise the Search Strategy:

- Replace any deleted MeSH terms with their current equivalents using the Replace Report [34].

- Add new, relevant MeSH terms to your strategy, combining them with

ORwhere appropriate.

- Test and Execute: Run the revised search. Compare the results and number to your baseline to ensure the changes behave as expected.

Analyzing Keywords in High-Impact Articles in Your Target Journal

This guide provides a systematic approach for researchers to analyze keywords in high-impact articles, enhancing the discoverability of their scientific publications. Effective keyword strategy ensures your work reaches the right audience, increasing its potential for citation and impact [24] [21].

The methodology is summarized in the table below, followed by detailed experimental protocols and reagent information.

| Method Step | Primary Objective | Key Outcome Metrics | Recommended Tools & Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Journal Identification | Select appropriate high-impact journals for analysis. | List of 3-5 target journals with high impact factors in your field. | Journal Citation Reports (JCR), Scopus, Google Scholar Metrics |

| Article Collection & Screening | Gather a relevant corpus of recent articles for analysis. | A final set of 15-20 articles from the last 2-3 years. | Journal websites, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science |

| Keyword Extraction & Cataloging | Systematically identify and record keywords and phrases. | A structured table of keywords, their frequency, and context. | Spreadsheet software (e.g., Excel, Google Sheets) |

| Pattern Analysis & Strategy Formulation | Identify common keyword patterns and formulate a selection strategy. | A list of validated, high-priority keywords and title construction tips. | Frequency analysis, comparison with controlled vocabularies (e.g., MeSH) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Article Collection and Corpus Building

Objective: To assemble a representative and high-quality collection of articles from your target journal for analysis.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access

- Access to databases: (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, or the journal's own website)

- Reference management software (e.g., Zotero, Mendeley)

Method:

- Define Scope: Determine the relevant time frame for your analysis. A 2-3 year period is typically sufficient to capture recent trends without being overwhelming.

- Search and Filter: On the journal's website or a major database, search for articles published within your chosen time frame. Filter by article type (e.g., Research Article, Review) to focus on content most relevant to your planned submission.

- Select Articles: Randomly select or systematically review 15-20 articles from the results. Ensure the selected articles are within your research domain to make the keyword analysis directly applicable.

- Compile Corpus: Use reference management software to save the full bibliographic information of each article, including title, abstract, author keywords, and publication date.

Protocol 2: Systematic Keyword Extraction and Analysis

Objective: To deconstruct the keywords and title structures of the collected articles to identify effective patterns.

Materials:

- Corpus of articles from Protocol 1

- Spreadsheet software (e.g., Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets)

Method:

- Data Entry: Create a spreadsheet with the following columns: Article ID, Article Title, Author Keywords, Keywords from Abstract, Notes.

- Populate Data: For each article in your corpus, copy the author-provided keywords into the "Author Keywords" column.

- Abstract Analysis: Read the abstract and title of each article. Identify and note 3-5 core concepts or key phrases in the "Keywords from Abstract" column. Pay attention to:

- The specific population, organism, or material studied (e.g., "Drosophila melanogaster," "breast cancer cell lines").

- The key methods or techniques used (e.g., "CRISPR-Cas9," "RNA sequencing," "crystal structure analysis").

- The main variables, outcomes, or phenomena investigated (e.g., "tumor growth inhibition," "cognitive decline," "catalytic activity").

- Frequency Analysis: Tally the frequency of each unique keyword and key phrase across all articles in your corpus. This will highlight the most common and likely most effective terminology in your field.

- Strategy Formulation:

- Identify Gaps: Look for concepts in your own research that align with high-frequency keywords from the analysis.

- Check Guidelines: Consult the author guidelines of your target journal for specific rules on keywords (e.g., number allowed, use of controlled vocabularies like MeSH).

- Finalize List: Create a final list of 5-8 keywords for your manuscript. Prioritize terms that are both high-frequency and accurately describe your work. Integrate the most important ones naturally into your paper's title [24] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How many articles should I analyze to get reliable results?

Answer: A corpus of 15-20 recent articles from your target journal is typically sufficient to identify strong patterns without being unmanageable. If the journal publishes very broadly, you may want to narrow your analysis to a specific sub-topic or article type.

FAQ 2: My keywords are too specific. How can I make my paper more discoverable?

Answer: Use a mix of specific and broader terms. While "CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in zebrafish cardiomyocytes" is precise, also include related terms like "gene therapy," "animal model," and "heart development" to capture a wider, interdisciplinary audience [21].

FAQ 3: What are the most common mistakes to avoid when selecting keywords?

Answer:

- Overly Generic Terms: Avoid single words like "biology" or "analysis" that are too broad to be useful.

- Keyword Stuffing: Do not create an overly long or awkward title crammed with keywords. Clarity for human readers is paramount [21].

- Unrecognized Acronyms: Spell out acronyms unless they are universally known (e.g., DNA, MRI).

- Ignoring Journal Guidelines: Always check the journal's instructions for authors regarding the number and format of keywords.

Guide 1: Resolving Common Keyword Analysis Issues

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inability to find enough relevant articles in the target journal. | The journal's scope is too broad/narrow, or your research is highly niche. | 1. Verify the journal's stated scope. 2. Search for your research domain + journal name. | 1. Expand analysis to 2-3 similar journals. 2. Consult review articles in the journal for keyword ideas. |

| No clear pattern emerges from keyword analysis. | The journal may publish on very diverse topics, or the corpus is too small. | 1. Check the frequency of your initial keywords. 2. Increase corpus size to 25 articles. | 1. Focus on keywords from articles in your immediate sub-field. 2. Use online keyword tools (e.g., MeSH, Google Keyword Planner) for additional ideas [21]. |

| Your key concept is described by multiple different terms in the literature. | Evolving terminology or interdisciplinary nature of the field. | 1. Note all variants found in the corpus. 2. Check which term is used in recent review articles. | 1. Include the 2-3 most common synonyms in your keyword list. 2. Use the most prevalent term in your title and abstract. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential digital tools and resources for conducting effective keyword and publication analysis.

| Tool / Resource Name | Primary Function | Application in Keyword Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed / MeSH | A biomedical literature database with a controlled vocabulary thesaurus. | Identify standardized, precise keywords that improve indexing and retrieval in biomedical databases [21]. |

| Google Scholar | A broad-search academic search engine. | Analyze how articles are titled and what keywords lead to high visibility in search results [21]. |

| Journal Author Guidelines | Instructions for authors provided by the publisher. | Determine the specific number, format, and type of keywords required for manuscript submission. |

| Reference Management Software (Zotero, Mendeley) | Software to collect, manage, and cite research sources. | Build and organize your corpus of articles for efficient analysis and data extraction. |

| Spreadsheet Software (Excel, Sheets) | Application for organizing and analyzing data in a tabular format. | Create a structured framework for cataloging keywords, calculating frequencies, and identifying patterns. |

Keyword Analysis Workflow Visualization

Keyword Selection Logic

Troubleshooting PubMed Search Issues

Q: Why is my PubMed search ignoring some of my terms or not returning the expected number of results?

A: This is often due to a functional error or a typo in your search strategy.

- Quoted Phrase Not Found: If you search for a phrase in double quotes (e.g.,

"progenitor cell transplantation") and PubMed does not find it in its phrase index, it will show an error. To fix this, you can remove the quotes, but this will broaden your search by placingANDbetween each word. A better solution is to use proximity searching to find the terms near each other, for example:"progenitor cell transplantation"[tiab:~3][37]. - Terms Were Ignored: This error is typically caused by unbalanced parentheses, quotation marks, or duplicate Boolean operators. Use the "Advanced Search" feature and click the "!" under "Details" to expand your search strategy and locate the error [37].

- Boolean Operator Errors: The Boolean operators

AND,OR, andNOTmust be in all capital letters. If they are not, PubMed will treat them as search terms. If you omit a Boolean operator between terms, PubMed will automatically insert anAND, which may significantly alter your results [37].

Q: How can I effectively use authors, journals, and dates to find a specific paper in PubMed?

A: Using field tags helps you target your search precisely.

- Author: Enter the last name and initials (e.g.,

smith ja). For a more specific search, use the[au]tag. To turn off automatic truncation of author names, use double quotes:"smith j"[au][38]. - Journal: Enter the full title, abbreviation, or ISSN. Use the

[ta]tag to limit your search to the journal field (e.g.,nature[ta]) [38]. - Date: You can search by a single date or a range. Use the format

yyyy/mm/dd[dp]for the publication date. For example, to find articles on cancer published on June 1, 2020, search:cancer AND 2020/06/01[dp]. For a date range, use a colon:heart disease AND 2019/01/01:2019/12/01[dp][38].

Q: What is the best way to combine keywords and MeSH terms for a comprehensive search?

A: A robust search strategy uses both keywords and MeSH terms to ensure completeness [39].

- Keywords are your own terms and are useful for finding very recent articles that may not yet have MeSH terms assigned. Use quotes for phrase searching (e.g.,

"hospital acquired infection") and an asterisk*for truncation (e.g.,arthroplast*) [39]. - Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) are a controlled vocabulary that helps account for different wordings and acronyms for the same concept. You can search for MeSH terms in the MeSH database and add them to your search using the PubMed Search Builder [39].

- Combine Concepts: Use Boolean operators to link your concepts. Use

ORto combine synonyms and similar keywords for a single concept, and useANDto link different concepts together [39].

AI and Advanced Tools for Data Extraction and Literature Mapping

The following table summarizes AI-powered tools that can semi-automate the data extraction process and help map the scientific landscape.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Opscidia [40] | AI-powered scientific search & summarization | Extracts key passages from articles to answer specific questions; generates sourced summaries; useful for R&D competitive intelligence. |

| Iris.ai [40] | Research assistant for data extraction | Focused on extracting specific data (e.g., formulas, numerical results) from a set of papers for comparative analysis. |

| Semantic Scholar [40] | Free semantic academic search engine | Analyzes query meaning, not just keywords; highlights "influential" citations; provides TLDR summaries. |

| Scite.ai [40] | Citation context and reliability analysis | Shows if citations support or contrast a finding; helps assess scientific consensus and paper reliability. |

| ResearchRabbit [41] [42] | Literature mapping and discovery | Visualizes connections between papers and authors; creates research collections; integrates with Zotero and Mendeley. |

Q: What are the common technical challenges when using AI for data extraction from scientific literature?

A: A 2024 living systematic review on automated data extraction highlights several key challenges [43]:

- Reproducibility and Reporting Quality: There is a trend of decreasing quality in the reporting of quantitative results, such as recall, when using newer methods like Large Language Models (LLMs), making it harder to reproduce and validate results [43].

- Focus on Specific Study Types: The vast majority (96%) of developed tools are classifiers for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), with fewer tools available for other study types [43].

- Limited Public Tool Availability: Despite active research, only a small percentage of publications result in publicly available tools. As of the latest review, only 9 (8%) of the 117 included publications had implemented publicly accessible tools [43].

Experimental Protocol: Methodology for a Semi-Automated Systematic Review Data Extraction Workflow

- Tool Selection and Setup: Based on your field and the entities you need to extract (e.g., PICO elements), select an appropriate AI tool from the table above. For this protocol, we will use a combination of Semantic Scholar for initial discovery and Opscidia for detailed extraction and summarization [40].

- Seed Paper Identification: Conduct a preliminary search using your selected keywords on Semantic Scholar to identify 5-10 highly relevant "seed" papers that are foundational to your research topic [40].

- Literature Expansion and Visualization: Import the seed papers into ResearchRabbit. Use the platform's visualization features to discover connected papers, identify key authors, and map the research landscape to ensure comprehensive coverage [41] [42].

- AI-Assisted Data Extraction: Upload the full-text PDFs of the final included studies to Opscidia. Use its AI to ask specific questions and extract key information, such as population details, interventions, outcomes, and main results. The tool will provide sourced paragraphs for verification [40].

- Validation and Synthesis: Manually check a subset of the AI-extracted data against the original articles to ensure accuracy. Use the compiled, sourced data to synthesize your findings in a structured format (e.g., a table of extracted data for your systematic review).

The workflow for this protocol can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Digital Toolkit: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions"

Just as an experiment requires specific physical reagents, effective digital research requires a toolkit of software and platforms. The table below details key "reagent solutions" for navigating the scientific literature.

| Tool / "Reagent" | Category | Function / "Role in the Experiment" |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed [39] [38] | Bibliographic Database | Core platform for searching biomedical literature; uses MeSH terms & keywords for precise discovery. |

| MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) [39] | Controlled Vocabulary | The "standardized buffer" that accounts for terminology variation, ensuring comprehensive retrieval. |

| Boolean Operators (AND, OR, NOT) [37] [39] | Search Logic | The "catalyst" that combines search concepts logically to broaden or narrow the result set. |

| ResearchRabbit [41] [42] | Literature Mapping | An "assaying instrument" that visually maps connections between papers and authors to reveal research trends. |

| Opscidia / Iris.ai [40] | AI Data Extraction | Acts as an "extraction enzyme" to automatically pull specific data (PICO, results) from full-text articles. |

| Zotero / Mendeley [41] | Reference Manager | The "storage solvent" for organizing PDFs, managing citations, and integrating with writing tools. |

The logical relationship and application of these tools in a research workflow are shown below:

FAQ: Keyword Selection for Scientific Publications

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a single-word keyword and a long-tail phrase? A single-word keyword (e.g., "diabetes") is a broad term that represents a general subject area. It typically has high search volume but also high competition, making it difficult for a specific paper to rank highly in search results. A long-tail phrase (e.g., "pediatric diabetes blood glucose monitoring") is a longer, more specific combination of words that defines a very specific research niche [44]. These phrases have lower search volume but much clearer search intent and lower competition, which can lead searchers directly to your specialized paper [45].

Q2: How do I know if my keywords are too broad or too specific? Test your keywords in databases like Google Scholar or your field-specific repository [45]. If your keyword (e.g., "ocean") returns an avalanche of results that are only vaguely related to your work, it is too broad. If your keyword (e.g., "salt panne zonation") returns very few or no results, it may be too specific [44]. The ideal keyword should pull up a manageable number of articles that are very similar to your own [45].

Q3: Should I avoid using single words as keywords entirely? Generally, yes. Most experts recommend avoiding keywords that are only one word because they render a search unspecific, and your paper can get lost in a sea of other papers [45]. You should aim to be specific enough that your main area of research is clearly defined. For instance, 'blood glucose' or 'insulin' may be too broad for a study on pediatric diabetes; instead, use more descriptive long-tail phrases relevant to your study [45].

Q4: Can I use keywords that are already in my paper's title? You should avoid overlapping keywords between your title and your designated keyword list [45]. Do not "waste keyword space" on words already used in the title. The keyword section is an opportunity to supplement the terms in your title with additional, relevant terms that improve discoverability.

Q5: Where in my paper are keywords most critical for discoverability? While a dedicated keyword section is important, strategic placement of keywords within the body of your paper is crucial for search engine optimization (SEO). The most critical locations are:

- Title: Try to include one or two primary keywords within the first 65 characters [44].

- Abstract: Place the most important key terms near the beginning, as not all search engines display the entire abstract [24]. Use key terms or phrases that are likely to appear in search queries.

- Section Headings: Using keywords in your headings signals the article's structure and substance to search engines [44].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Keyword Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Discoverability | Your paper does not appear in search results for relevant queries. | Increase the use of long-tail keywords. Conduct research using tools like Google Scholar or field-specific thesauri (e.g., MeSH) to find more precise, optimized terms that are frequently searched [20] [44]. |

| High Competition | Your paper is buried under thousands of results from more established papers when searching your keywords. | Shift focus to more specific long-tail phrases. Analyze the keywords used by competing papers and identify gaps or more niche aspects you can target [46] [45]. |

| Irrelevant Matches | Searchers who find your paper via keywords find it unrelated to their needs. | Refine keywords for specificity. Ensure your keywords accurately reflect the core topic, methodology, and findings of your research. Avoid ambiguous terms [47]. |

| Ignoring Journal Guidelines | Your manuscript is returned by the journal editor before review for non-compliance. | Carefully review the target journal's author instructions. Adhere to specifications for the number, format, and source (e.g., a required thesaurus like MeSH) of keywords [20] [45]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Method for Systematic Keyword Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for selecting the optimal mix of broad and long-tail keywords for a research manuscript.

1. Preliminary Keyword Brainstorming

- Objective: Generate a comprehensive list of potential keywords without initial filtering.

- Procedure:

- Write down the central themes of your research.

- List all key concepts, materials, methods, and phenomena.

- Include synonyms, related terms, and both broader and narrower terms for each concept [47].

- Deliverable: A raw list of 20-30 potential keywords and phrases.

2. Keyword Analysis and Refinement

- Objective: Refine the raw list by analyzing search trends and specificity.

- Procedure:

- Use Google Autocomplete: In an incognito browser, slowly type your core keywords and note the auto-suggested phrases. These represent real-time search queries [14].

- Use Google Keyword Planner or Google Trends: Input your keywords to get data on search volume and trends over time [44] [13]. This helps identify which terms are more popular.

- Use a Field-Specific Database: Search your keywords in PubMed, Google Scholar, or Web of Science. See which terms retrieve the most relevant and high-quality articles [20].

- Categorize Keywords: Classify each keyword from your raw list as either "Broad" (single or two-word terms) or "Long-tail" (specific phrases of three or more words).

3. Final Keyword Selection and Implementation

- Objective: Select the final 5-8 keywords as per journal guidelines.

- Procedure:

- Consult the journal's author guidelines for the required number and format of keywords [20].

- Create a final shortlist. Prioritize long-tail phrases for specificity, but include 1-2 broader terms if they are highly relevant and established in your field.

- Ensure your primary long-tail keywords are present in your title and abstract [24] [44].

- Avoid keyword stuffing; use them naturally within the text [44].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Keyword Research

| Tool Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | A freely accessible search engine that indexes scholarly literature across disciplines. Used to test keyword relevance and see what articles are retrieved [20]. | Validating keyword specificity and relevance in an academic context. |

| MeSH Thesaurus | The National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary thesaurus. Used to find optimized, standardized terms for biomedical and health-related fields [20]. | Ensuring compliance and discoverability in medical and life sciences journals. |

| Google Keyword Planner | A free tool within Google Ads that provides data on search volume and forecasts for keywords [14] [13]. | Understanding general search trends and volume for different terms. |

| Google Autocomplete | The feature in Google Search that suggests queries as you type. It reflects real-time, trending searches [14]. | Discovering long-tail phrases that users are actually searching for. |

| SCImago/Scopus | Bibliographic databases containing scientific publications. They can be used to analyze keyword usage in high-quality, quartile-ranked journals [47]. | Identifying keywords used in influential papers within a specific field. |

Incorporating Methodology and Technique Names as Keywords

Troubleshooting Guide: Incomplete Literature Search Results

Problem: Your database searches are failing to retrieve key papers, causing you to miss critical methodologies. Solution: Systematically combine keyword and controlled vocabulary searches [48] [49].

- Initial Scoping: Start with a "gold set" of 3-5 known, highly relevant papers. Use these to identify recurring methodology names and technique terms in their titles, abstracts, and keywords [49].

- Build a Concept Table: Structure your search strategy using a table to organize terms for each core concept of your research question [48].

Table: Example Concept Table for a Sample Preparation Search

| Concept A: Process | Concept B: Material | Concept C: Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Nanoparticles | Chromatography |

| Synthesis | Quantum Dots | Mass Spectrometry |

| Fabrication | Gold Nanoparticles | "Scanning Electron Microscopy" |

| MeSH: Nanostructures | MeSH: Metal Nanoparticles | MeSH: Chromatography, High Pressure Liquid |

- Execute the Search: In databases like PubMed and Scopus, search for terms in each column with

OR, then combine concepts withAND[48]. Use truncation (physiol*for physiology, physiological) and wildcards (isch*micfor ischemic/ischaemic) to capture term variations [48]. - Apply the WINK Technique: For complex topics, use the Weightage Identified Network of Keywords (WINK) method. Tools like VOSviewer analyze keyword co-occurrence networks in your field to identify the most significant methodology terms, potentially increasing article retrieval by over 25% [50].

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Overwhelming Search Results

Problem: Your search strategy retrieves too many irrelevant papers, making it unmanageable. Solution: Refine your search using precise methodology filters and Boolean operators.