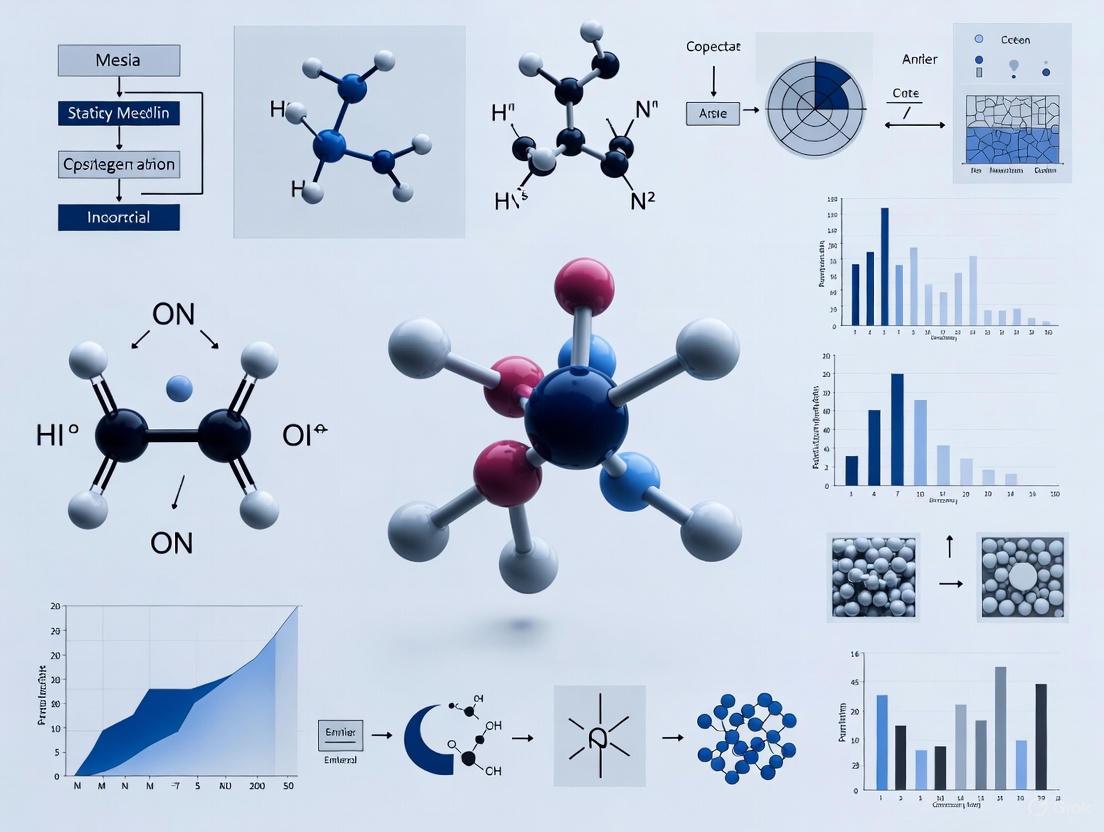

Statistical Methods for Materials Experimental Design: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Research

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of statistical methods tailored for materials science experimentation.

Statistical Methods for Materials Experimental Design: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Research

Abstract

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of statistical methods tailored for materials science experimentation. Covering the full spectrum from foundational concepts to cutting-edge machine learning approaches, it addresses critical challenges in experimental design, data analysis, and method validation. The content integrates traditional statistical frameworks with emerging computational techniques like Bayesian optimization and gradient boosting, offering practical guidance for troubleshooting common pitfalls and establishing rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing principles from true experimental designs, quasi-experimental methods, and advanced optimization algorithms, this resource enables professionals to accelerate materials discovery while ensuring methodological rigor and reproducibility across diverse research applications.

Fundamental Statistical Frameworks and Exploratory Data Analysis in Materials Science

| Category | Item | Function in Materials Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project Database [1] [2] | Repository of calculated material properties (e.g., elastic moduli) for initial screening and model training. |

| Software & Algorithms | Gaussian Process (GP) Models [3] | Supervised learning for small datasets; uncovers interpretable descriptors from expert-curated data. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [4] | Learns representations from crystal structures; scales effectively with data volume for property prediction. | |

| Gradient Boosting Framework (e.g., GBM-Locfit) [1] [5] | Combines local polynomial regression with gradient boosting for accurate predictions on modest-sized datasets. | |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [6] | Guides the design of sequential experiments by balancing exploration and exploitation of the design space. | |

| Experimental Infrastructure | Robotic/Automated Lab Equipment [6] | Enables high-throughput synthesis (e.g., liquid-handling, carbothermal shock) and characterization. |

| Computer Vision & Visual Language Models [6] | Monitors experiments in real-time to detect issues and improve reproducibility. |

{# Introduction to Statistical Learning Frameworks for Materials Discovery}

The application of statistical learning (SL) has transformed materials discovery from a domain reliant on intuition and serendipity to a data-driven engineering science. These frameworks enable researchers to navigate vast compositional and structural spaces, accelerating the identification of novel materials for applications from clean energy to semiconductors [4] [2]. This guide details the core concepts, quantitative benchmarks, and practical protocols for implementing SL in materials research, framed within the context of advanced experimental design.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Frameworks

Statistical learning frameworks in materials science are designed to address unique challenges, including diverse but modest-sized datasets, the prevalence of extreme values (e.g., for superhard materials), and the need to generalize predictions across diverse chemistries and structures [1] [5].

Foundational Statistical Learning Framework

This framework introduces two key advances for handling materials data:

- Generalized Descriptors via Hölder Means: Standardizes the construction of descriptors from variable-length elemental property lists (e.g., atomic radii, electronegativity). Hölder means (e.g., harmonic, geometric, arithmetic) create a uniform representation for k-nary compounds, enabling models to generalize across the periodic table [1] [5].

- Gradient Boosting with Local Regression (GBM-Locfit): Integrates multivariate local polynomial regression (Locfit) within a gradient boosting machine (GBM). This technique exploits the inherent smoothness of energy-related functions, reducing boundary bias and improving performance on smaller datasets compared to standard tree-based methods [1] [7].

Advanced and Integrated Frameworks

Subsequent developments have scaled these concepts and integrated them with automated experimentation.

- Scaled Deep Learning (GNoME): Utilizes graph networks trained on massive datasets (millions of structures) through active learning. These models demonstrate emergent generalization, accurately predicting crystal stability and properties, even for compositions with five or more unique elements, which were previously intractable [4].

- Multimodal and Robotic Frameworks (CRESt): A copilot system that incorporates diverse information sources—scientific literature, experimental results, microstructural images, and human intuition—to plan and optimize experiments. It uses robotic equipment for high-throughput synthesis and testing, creating a closed-loop discovery system [6].

- Expert-Informed AI (ME-AI): A framework that encodes human expert intuition into machine learning. It uses a Gaussian process with a chemistry-aware kernel on curated experimental data to uncover interpretable, often chemically intuitive, descriptors for complex properties like topological semimetals [3].

Quantitative Performance of SL Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Application | Key Metric | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBM-Locfit [1] [5] | Predicting Elastic Moduli (K, G) | Application on a dataset of 1,940 compounds for screening superhard materials. | |

| GNoME [4] | Discovering Stable Crystals | Prediction Error (Energy) | 11 meV/atom |

| Precision of Stable Predictions (Hit Rate) | >80% (with structure) | ||

| Stable Materials Discovered | 2.2 million structures | ||

| CRESt [6] | Fuel Cell Catalyst Discovery | Experimental Cycles | 3,500 electrochemical tests |

| Improvement in Power Density | 9.3-fold per dollar over pure Pd | ||

| ME-AI [3] | Classifying Topological Materials | Predictive Accuracy & Transferability | Demonstrated on 879 square-net compounds; successfully transferred to rocksalt structures. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GBM-Locfit for Predicting Elastic Moduli

This protocol is adapted from the foundational work by de Jong et al. [1] [5].

1. Problem Formulation & Data Sourcing:

- Objective: Predict bulk (K) and shear (G) moduli of inorganic polycrystalline compounds.

- Data Collection: Obtain a curated dataset from computational databases like the Materials Project. The exemplary study used 1,940 compounds [1].

2. Feature Engineering & Descriptor Construction:

- For each compound, compile a list of relevant elemental properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron count) for all constituent elements.

- Apply Hölder Means: For each property, calculate a suite of Hölder means (e.g., p = -1, 0, 1, 2 for harmonic, geometric, arithmetic, quadratic means) to create a fixed-length descriptor vector that is invariant to the number of elements.

3. Model Training with GBM-Locfit:

- Implementation: Use a gradient boosting framework where the base learner is a local polynomial regression model (e.g., using the

Locfitlibrary). - Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize parameters such as the boosting iteration number, learning rate, and the bandwidth of the local regression kernel via cross-validation.

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting and obtain robust error estimates on the dataset.

4. Screening and Validation:

- Use the trained model to screen new candidate compounds from vast databases.

- Prioritize candidates predicted to have extreme values (e.g., high modulus for superhard materials) for further validation via first-principles calculations (DFT) or experimental synthesis [1].

GBM-Locfit Workflow: A statistical learning pipeline for material property prediction.

Protocol 2: Active Learning with GNoME for Stable Crystal Discovery

This protocol outlines the large-scale active learning process used by the GNoME framework [4].

1. Candidate Generation:

- Structural Candidates: Generate new crystal structures by modifying known ones using symmetry-aware partial substitutions (SAPS), creating a vast and diverse candidate pool (>10^9).

- Compositional Candidates: Generate reduced chemical formulas using relaxed oxidation-state constraints.

2. Model Filtration:

- Structural Filtration: Use an ensemble of GNoME graph networks to predict the formation energy of candidates. Employ test-time augmentation and uncertainty quantification to filter promising structures.

- Compositional Filtration: For composition-only candidates, use a separate GNoME model to predict stability, then initialize 100 random structures for each using ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS).

3. DFT Verification and Data Flywheel:

- Evaluate the filtered candidates using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations with standardized settings (e.g., in VASP).

- The resulting energies and relaxed structures are added to the training database.

4. Iterative Active Learning:

- Retrain the GNoME models on the expanded dataset.

- Repeat the cycle of generation, filtration, and verification for multiple rounds. This iterative process progressively improves model accuracy and discovery efficiency, as evidenced by the hit rate increasing from <6% to over 80% [4].

GNoME Active Learning Cycle: A closed-loop system for scaling materials discovery.

Protocol 3: Integrated Human-AI Workflow with CRESt

This protocol describes the operation of the CRESt platform, which functions as a "copilot" for experimentalists [6].

1. Natural Language Tasking:

- A researcher converses with the CRESt system in natural language, specifying a goal (e.g., "find a high-activity, low-cost fuel cell catalyst").

2. Multimodal Knowledge Integration and Planning:

- CRESt queries scientific literature and internal databases to build a knowledge base.

- It uses an active learning algorithm, enhanced with literature and human feedback, to define a reduced search space in the knowledge embedding space.

- The system then plans a series of experiments, suggesting specific material recipes (it can handle up to 20 precursor molecules and substrates).

3. Robotic Execution and Monitoring:

- Robotic systems (liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock synthesizers) execute the synthesis plans.

- Automated characterization equipment (electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction) and electrochemical workstations test the synthesized materials.

- Computer Vision Monitoring: Cameras and vision-language models monitor experiments in real-time, detecting issues (e.g., sample misplacement) and suggesting corrections to the human operator.

4. Analysis and Iteration:

- Characterization and performance data are fed back into the large multimodal model.

- The model analyzes the results, updates its knowledge base, and proposes the next set of optimized experiments, continuing the discovery cycle. This process led to the discovery of an 8-element catalyst with a record power density [6].

CRESt System Workflow: An AI copilot that integrates planning, robotics, and multimodal feedback.

Core Conceptual Framework

Variables in Materials Science Experiments

In materials experimental design, variables are defined as any factor, attribute, or value that describes a material or experimental condition and is subject to change [8]. The systematic manipulation and measurement of these variables allows researchers to establish cause-and-effect relationships in materials behavior and properties.

- Independent Variable: The factor that the researcher intentionally manipulates or changes to observe its effect on the material's properties. In materials science, this could include processing temperature, chemical composition, pressure, or annealing time [8].

- Dependent Variable: The resulting material property or characteristic that is measured as the outcome. Examples include elastic moduli, hardness, tensile strength, conductivity, or catalytic activity [8] [1].

- Controlled Variables: Experimental conditions that are kept constant to prevent them from influencing the results. In materials experiments, this may include ambient humidity, sample preparation methods, testing equipment calibration, or raw material sources [8].

- Confounding Variables: Extraneous factors that can inadvertently affect both the independent and dependent variables, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions. Examples include batch-to-batch variations in precursor materials or uncontrolled impurities in starting compounds [9] [8].

The Role and Types of Control Groups

Control groups serve as a baseline reference that enables researchers to isolate the effect of the independent variable by providing a standard for comparison [9] [10]. In materials science, proper control groups are essential for distinguishing actual treatment effects from natural variations in material behavior or measurement artifacts.

Table: Types of Control Groups in Materials Experiments

| Control Group Type | Description | Materials Science Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated Control | Receives no experimental treatment | A material sample that undergoes identical handling except for the key processing step (e.g., no heat treatment) |

| Placebo Control | Receives an inert treatment | Using an inert substrate in catalyst testing to distinguish substrate effects from catalytic effects |

| Standard Treatment Control | Receives an established, well-characterized treatment | Comparing a new alloy against a standard reference material with known properties |

| Comparative Control | Multiple control groups for different aspects | Controlling for both composition and processing parameters in complex materials synthesis |

The critical importance of control groups lies in their ability to ensure internal validity—the confidence that observed changes in the dependent variable are actually caused by the manipulated independent variable rather than other factors [9]. Without appropriate controls, it becomes difficult to attribute changes in material properties specifically to the experimental manipulation, as materials can exhibit natural variations, aging effects, or responses to unmeasured environmental conditions [9].

Randomization Principles and Protocols

Fundamentals of Randomization

Randomization involves the random allocation of experimental units (e.g., material samples, test specimens) to different treatment groups or the random ordering of experimental runs [11] [12]. This technique serves to balance the effects of extraneous or uncontrollable conditions that might otherwise bias the experimental results [13].

In materials science, randomization is particularly valuable for addressing:

- Unknown or uncontrollable variations in raw materials

- Subtle environmental fluctuations during processing

- Equipment calibration drift over time

- Operator-induced variations in sample handling

The implementation of randomization produces comparable groups and eliminates sources of bias in treatment assignments, while also permitting the legitimate application of probability theory to express the likelihood that observed differences occurred by chance [11].

Randomization Techniques and Methodologies

Several randomization techniques have been developed, each with specific advantages for different experimental scenarios in materials research:

Simple Randomization: This most basic form uses a single sequence of random assignments, analogous to flipping a coin for each specimen [11]. While straightforward to implement, this approach can lead to imbalanced group sizes, especially with smaller sample sizes common in materials research where experiments may be costly or time-consuming.

Block Randomization: This method randomizes subjects into groups that result in equal sample sizes by using small, balanced blocks with predetermined group assignments [11]. The block size is determined by the researcher and should be a multiple of the number of groups. For example, with two treatment groups, block sizes of 4, 6, or 8 might be used.

Stratified Randomization: This technique addresses the need to control and balance the influence of specific covariates known to affect materials properties [11]. Researchers first identify important covariates (e.g., initial grain size, impurity content), then generate separate blocks for each combination of covariates, and finally perform randomization within each block.

Covariate Adaptive Randomization: For smaller experiments where simple randomization may result in imbalance of important covariates, this approach sequentially assigns new specimens to treatment groups while taking into account specific covariates and previous assignments [11].

Table: Randomization Techniques Comparison for Materials Research

| Technique | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Randomization | Large sample sizes; preliminary studies | Maximum randomness; easy implementation | Potential group imbalance with small N |

| Block Randomization | Small to moderate sample sizes; balanced design | Ensures equal group sizes; controls time-related bias | Limited control over known covariates |

| Stratified Randomization | Known influential covariates; heterogeneous materials | Controls for specific known variables; increases precision | Complex with multiple covariates; requires pre-collected data |

| Covariate Adaptive | Small studies with multiple important covariates | Optimizes balance on multiple factors | Complex implementation; statistical properties less known |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

Materials Experimentation Workflow

Experimental Workflow for Materials Research

Variable Relationships in Materials Experiments

Variable Relationships and Control Mechanisms

Application Protocol: Elastic Moduli Testing

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the application of control groups and randomization in testing elastic moduli of inorganic polycrystalline compounds, based on established materials science methodologies [1].

Objective: To determine the effect of compositional variations on bulk (K) and shear (G) moduli of k-nary inorganic polycrystalline compounds while controlling for confounding variables through randomization and appropriate control groups.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-purity precursor materials (elements, compounds)

- Synthesis equipment (furnace, ball mill, press)

- Characterization tools (XRD, SEM, density measurement)

- Mechanical testing system for elastic moduli determination

- Statistical computing environment (R, Python, or specialized software)

Procedure:

Sample Size Determination and Power Analysis

- Conduct preliminary power analysis to determine adequate sample size

- Plan for minimum of 6-10 specimens per treatment group

- Include additional samples to account for potential synthesis failures

Control Group Design

- Establish reference control group using well-characterized standard material

- Include processing control group that undergoes identical handling except for the key compositional variation

- Utilize positive controls with known property relationships when available

Randomization Implementation

- Assign unique identifiers to all precursor material batches

- Randomize the sequence of synthesis operations using computer-generated random number sequences

- Implement block randomization to ensure balanced distribution of synthesis dates across experimental groups

- Blind testing personnel to sample group assignments during properties measurement

Synthesis and Processing

- Prepare compounds according to established synthesis protocols

- Document all processing parameters as potential controlled variables

- Reserve aliquots of starting materials for subsequent characterization

Characterization and Testing

- Characterize all samples for phase purity, density, and microstructure

- Measure elastic moduli using consistent testing parameters

- Include control specimens in each testing batch to monitor equipment consistency

Data Collection and Quality Assurance

- Implement automated data recording to minimize transcription errors

- Perform preliminary statistical checks for outliers and data distribution

- Verify randomization effectiveness by comparing baseline characteristics across groups

Statistical Analysis Plan

Primary Analysis:

- Descriptive statistics for all variables by experimental group

- Assessment of normality assumption using Shapiro-Wilk test

- Comparison of group means using ANOVA with post-hoc testing

- Calculation of effect sizes with confidence intervals

Secondary Analysis:

- Covariate adjustment for any imbalances despite randomization

- Subgroup analyses if pre-specified in the experimental plan

- Sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of findings

Data Quality Measures:

- Implementation of missing data protocols with predetermined thresholds

- Assessment of measurement reliability through repeated testing of controls

- Evaluation of randomization success by comparing baseline variables

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Controlled Materials Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Quality Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | NIST standard reference materials; Well-characterized control compounds | Provides calibration and baseline measurements; Enables cross-experiment comparisons | Certified reference materials with documented uncertainty |

| Characterization Tools | XRD standards; SEM calibration samples; Density reference materials | Ensures measurement accuracy and instrument calibration; Validates experimental setup | Traceable to national standards; Documented measurement uncertainty |

| Statistical Software | R Environment; Python with scikit-learn; Minitab; GraphPad QuickCalcs | Randomization schedule generation; Statistical analysis implementation; Results validation | Validated algorithms; Reproducible random number generation |

| Laboratory Equipment | Controlled atmosphere furnaces; Automated sample preparation systems | Minimizes operator-induced variability; Standardizes processing conditions | Regular calibration records; Documented operating procedures |

Implementation Guidelines and Considerations

Practical Implementation Challenges

Materials scientists face specific challenges when implementing rigorous experimental designs, particularly when working with complex material systems or limited sample availability. Statistical learning frameworks have been developed to address these challenges, especially when datasets are diverse but of modest size, and extreme values are often of interest [1].

Small Sample Considerations:

- Prioritize block randomization over simple randomization

- Consider covariate adaptive randomization when important prognostic factors are known

- Increase reliance on historical control data when available

- Implement more stringent Type I error control

High-Throughput Experimentation:

- Utilize automated randomization systems integrated with robotic handling

- Implement planned missing data designs for efficiency

- Employ factorial designs to maximize information from limited samples

- Use statistical learning approaches that pool training data across related compounds [1]

Validation and Reporting Standards

Randomization Validation:

- Document the specific randomization method used

- Report the random number generation algorithm and seed

- Verify and report balance of baseline characteristics across groups

- Describe allocation concealment methods

Control Group Validation:

- Document control group selection rationale

- Report stability and performance of control materials throughout experiment

- Include tests for contamination or interference between groups

- Verify that control groups provide adequate reference baseline

Complete Reporting:

- Follow CONSORT guidelines or materials-specific reporting standards

- Include both statistically significant and non-significant findings [14]

- Report precision of estimates through confidence intervals

- Document all protocol deviations and their potential impact

The integration of these rigorous experimental design principles—proper variable identification, appropriate control groups, and thorough randomization—provides the foundation for valid, reproducible materials research that can reliably inform both scientific understanding and engineering applications.

The selection of an appropriate experimental design is fundamental to establishing valid cause-and-effect relationships in materials and drug development research. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three primary design categories.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Experimental Designs

| Feature | True Experimental Design | Quasi-Experimental Design | Factorial Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Assignment | Required; participants are randomly assigned to groups [15] [16] | Not used; assignment is non-random due to practical/ethical constraints [17] [18] | Can be incorporated (e.g., randomly assigning subjects to treatment combinations) [19] |

| Control Group | Always present as a baseline for comparison [15] [16] | May or may not be present; often uses a non-equivalent comparison group [17] [18] | A control condition can be included as one level of a factor [19] |

| Key Purpose | Establish causality with high internal validity [16] | Estimate causal effects when true experiments are not feasible [17] [18] | Analyze the effects of multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously [19] |

| Internal Validity | High, due to randomization and control [16] [20] | Lower than true experiments due to potential confounding variables [17] [18] | High, especially if combined with random assignment [19] |

| Primary Application Context | Highly controlled lab settings, clinical trials [16] | Real-world field settings (e.g., policy changes, clinical interventions on groups) [17] [18] | Experiments involving two or more independent variables (factors) where interaction effects are of interest [19] |

Detailed Design Types and Experimental Protocols

True Experimental Designs

True experimental designs are considered the gold standard for causal inference due to the use of random assignment, which minimizes selection bias and the influence of confounding variables [16].

Table 2: Types of True Experimental Designs

| Design Type | Protocol Description | Example Application in Materials/Drug Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pretest-Posttest Control Group Design | 1. Randomly assign subjects to experimental and control groups.2. Measure the dependent variable in both groups (Pretest, O1).3. Apply the intervention to the experimental group only (Xe).4. Re-measure the dependent variable in both groups (Posttest, O2) [15] [16]. | Testing a new polymer's tensile strength. Both groups of polymer samples are pre-tested. Only the experimental group undergoes a new curing process before both groups are post-tested. |

| Posttest-Only Control Group Design | 1. Randomly assign subjects to experimental and control groups.2. Apply the intervention to the experimental group only.3. Measure the dependent variable in both groups once, after the intervention [17] [16]. | Evaluating a new drug's efficacy. One randomly assigned group receives the drug, the other a placebo. Outcomes (e.g., reduction in tumor size) are measured only at the end of the trial period. |

| Solomon Four-Group Design | 1. Randomly assign subjects to four groups.2. Two groups complete a pretest (O1), two do not.3. One pretest group and one non-pretest group receive the intervention (Xe).4. All four groups receive a posttest (O2). This design controls for the potential effect of the pretest itself [16]. | Studying the effect of a training protocol on technician performance, while testing if the initial skill assessment (pretest) influences the outcome. |

The logical workflow for a true experimental design, specifically the Pretest-Posttest Control Group Design, can be visualized as follows:

Quasi-Experimental Designs

Quasi-experimental designs are employed when random assignment is impractical or unethical, such as when administering interventions to pre-existing groups (e.g., a specific manufacturing plant or a cohort of patients) [17] [18]. While useful, they are more susceptible to threats to internal validity.

Table 3: Common Quasi-Experimental Designs

| Design Type | Protocol Description | Example Application in Materials/Drug Research |

|---|---|---|

| Non-equivalent Groups Design | 1. Select two pre-existing, similar groups (e.g., two production lines).2. Implement the intervention for one group (treatment group).3. Measure the outcome variable in both groups after the intervention. A pretest is often used to establish group similarity [17] [18]. | Comparing the purity yield of a chemical compound between two similar production batches, where only one batch uses a new catalyst. |

| Pretest-Posttest Design (One-Group) | 1. Select a single group.2. Measure the dependent variable (Pretest, O1).3. Administer the intervention (X).4. Re-measure the dependent variable (Posttest, O2) [17]. | Measuring the degradation rate of a material before and after the application of a new protective coating. |

| Interrupted Time-Series Design | 1. Take multiple measurements of the dependent variable at regular intervals over time.2. Implement an intervention.3. Continue taking multiple measurements after the intervention. The data pattern before and after the intervention is analyzed [18]. | Monitoring the daily output of a pharmaceutical reactor for 30 days before and 30 days after a new calibration protocol is introduced. |

The structure of a Non-equivalent Groups Design, one of the most common quasi-experimental approaches, is depicted below:

Factorial Designs

Factorial designs are used to investigate the effects of two or more independent variables (factors) and their interactions on a dependent variable. In a full factorial design, all possible combinations of the factor levels are tested [19] [21].

Protocol: Conducting a 2x3 Factorial Experiment This protocol outlines the steps for a design with two factors, where Factor A has 2 levels and Factor B has 3 levels.

- Define Factors and Levels: Identify the independent variables. For example, Factor A (Treatment Type) with levels A1 and A2, and Factor B (Setting/Concentration) with levels B1, B2, and B3 [19].

- Establish Experimental Groups: Create 2 x 3 = 6 unique experimental groups, each corresponding to a combination of the factor levels (e.g., A1B1, A1B2, A1B3, A2B1, A2B2, A2B3).

- Random Assignment: Randomly assign experimental units (e.g., material samples, subjects) to each of the 6 groups.

- Implement Treatments: Apply the corresponding combination of factor levels to each group.

- Measure Outcome: Record the dependent variable (e.g., material strength, drug efficacy score) for all groups.

- Statistical Analysis: Use Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to analyze:

- The main effect of Factor A.

- The main effect of Factor B.

- The interaction effect between Factor A and Factor B (AxB) [19].

A 2x3 factorial design allows researchers to efficiently explore the effects of multiple variables and their interactions in a single, integrated experiment, as shown in the following workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Experimental Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Random Number Generator | A computational or physical tool to ensure random assignment of subjects or samples to experimental groups, which is critical for the validity of true experiments [15] [16]. |

| Control Group | A baseline group that does not receive the experimental intervention. It serves as a reference point to compare against the experimental group, allowing researchers to isolate the effect of the intervention [15] [17] [16]. |

| Validated Measurement Instrument | A device, survey, or assay (e.g., spectrophotometer, standardized questionnaire, mechanical tester) with proven reliability and accuracy for measuring the dependent variable [17]. |

| Placebo | An inert substance or treatment designed to be indistinguishable from the active intervention. It is used in clinical drug trials to control for psychological effects and ensure blinding [16]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, SPSS) | Software capable of performing advanced statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis) required to analyze experimental data and determine if results are statistically significant [16] [20]. |

| Blinding/Masking Protocols | Procedures where information about the intervention is withheld from participants (single-blind), researchers (double-blind), or both to prevent bias in the reporting and assessment of outcomes [20]. |

Exploratory Data Analysis Techniques for Materials Datasets

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) serves as the critical preliminary investigation of datasets to understand their underlying structure, detect patterns, and identify potential issues before formal hypothesis testing or modeling. In materials science research, EDA enables researchers to interact freely with experimental data without predefined assumptions, developing intuition about material properties, processing parameters, and performance characteristics. This open-ended investigation approach, coined by John Tukey, is particularly valuable for materials datasets where complex relationships between synthesis conditions, microstructure, and properties must be uncovered [22] [23].

The fundamental distinction between EDA and confirmatory analysis is especially relevant in materials research. While confirmatory analysis validates predefined hypotheses using statistical tests, EDA allows materials scientists to determine which questions are worth asking in the first place. This process uncovers hidden trends in processing-structure-property relationships, identifies anomalous measurements, and guides subsequent experimental design by revealing the most promising research directions [23]. For materials researchers dealing with high-dimensional experimental data, EDA provides the necessary foundation for building accurate predictive models and making data-driven decisions in materials development and optimization.

Core Principles and Objectives of EDA for Materials Data

Primary Goals of EDA in Materials Research

The implementation of EDA in materials science follows several well-defined objectives that address the specific challenges of materials datasets. These goals ensure that researchers extract maximum value from often expensive and time-consuming experimental data [22]:

Data Quality Assessment: Materials datasets frequently contain measurement errors, missing values due to failed experiments, and inconsistent annotations. EDA techniques help identify these issues before they compromise downstream analysis and model-building efforts. Through visualization techniques like histograms and boxplots, researchers can detect unexpected values that require investigation [22].

Variable Characterization: Understanding the distribution and characteristics of individual variables is essential in materials science. This includes analyzing the distribution of numeric variables (e.g., mechanical properties, composition ratios, processing parameters) and identifying frequently occurring values for categorical variables (e.g., crystal structure classes, synthesis methods) [22].

Relationship Detection: EDA aims to uncover relationships, associations, and patterns within materials datasets. This involves investigating interactions between two or more variables through visualizations and statistical techniques to reveal processing-structure-property relationships that might otherwise remain hidden [22].

Modeling Guidance: Insights from EDA inform the selection of appropriate variables for predictive modeling, help generate new hypotheses about material behavior, and aid in choosing suitable machine learning algorithms. Recognition of nonlinear patterns in materials data may suggest using nonlinear models, while identified subgroups might motivate building separate models for different material classes [22].

Implementation Framework

Effective EDA for materials datasets requires a structured yet flexible approach that acknowledges the domain-specific challenges. The traditional EDA workflow often involves significant tool-switching between SQL clients, computational environments like Jupyter Notebooks, visualization tools, and documentation platforms, creating friction that hinders productivity [23]. Modern integrated platforms address this limitation by providing cohesive environments that combine data access, manipulation, analysis, and visualization capabilities specifically designed for scientific workflows [23].

For materials researchers, maintaining reproducibility is particularly crucial. The entire analysis—from data extraction to visualization—should be documented as a single, linear document without hidden state to ensure that results remain consistent and reproducible when re-run with updated datasets [23]. This practice is essential for validating materials research findings and building upon previous experimental results.

Essential EDA Techniques and Workflows

Comprehensive EDA Protocol for Materials Datasets

A systematic EDA approach for materials science data involves multiple stages that build upon each other to develop a comprehensive understanding of the dataset. The following protocol outlines the key steps in a materials-focused EDA workflow:

Step 1: Data Collection and Understanding Collect all relevant raw data from various sources including experimental measurements, characterization results, simulation outputs, and literature data. Clearly document the context and domain of the materials research problem, noting all available features, their expected formats, and any metadata. For materials datasets, this might include processing parameters, structural characterization data, composition information, and performance metrics [22].

Step 2: Data Wrangling and Quality Assessment Clean, organize, and transform raw materials data into analysis-ready formats. This critical step includes:

- Removing duplicate records from repeated measurements

- Handling missing values common in failed experiments

- Converting data types to appropriate formats

- Fixing inconsistencies through validation checks

- Standardizing units and nomenclature across datasets [22]

Step 3: Data Profiling and Descriptive Statistics Compute comprehensive summary statistics for all variables to develop an initial quantitative understanding. For numeric variables in materials data (e.g., Young's modulus, hardness, particle size), calculate measures of central tendency (mean, median) and variability (standard deviation, range). For categorical variables (e.g., phase identification, synthesis method), determine counts and percentages for each category [22] [24].

Step 4: Missing Value Analysis and Treatment Systematically identify patterns of missingness in materials datasets and apply appropriate handling techniques. The approach should be guided by domain knowledge about why data might be missing (e.g., measurement instrument limitations, synthesis failures). Common techniques include case-wise deletion for minimally missing data or sophisticated imputation methods like MICE (Multivariate Imputation via Chained Equations) when substantial data is missing [22].

Step 5: Outlier Detection and Analysis Identify anomalous measurements that may represent experimental errors or genuinely extreme material behaviors. For numeric variables in materials data, use statistical measures like z-scores, IQR methods, or domain-specific thresholds. Visualization techniques like boxplots provide effective outlier detection. Decisions about outlier treatment should consider materials science context—removing only those outliers confirmed to represent measurement errors while retaining legitimate extreme observations [22].

Step 6: Data Transformation and Feature Engineering Apply transformations to normalize distributions, reduce skewness, and mitigate outlier effects. Common transformations include log, power, or inverse operations based on distribution characteristics. Create new features derived from existing variables that may have greater physical significance (e.g., hardness-to-density ratios, phase fraction calculations) [22].

Step 7: Dimensionality Reduction For high-dimensional materials data (e.g., spectral data, combinatorial library results), apply dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to compress variables into fewer uncorrelated components while retaining maximum information. This simplifies subsequent modeling and enhances interpretability [22].

Step 8: Univariate and Bivariate Exploration Conduct systematic investigation of individual variables and pairwise relationships. Use histograms, boxplots, and density plots for single variables. Employ scatter plots, correlation analysis, and grouped visualizations to explore relationships between variable pairs relevant to materials behavior (e.g., processing temperature vs. grain size, composition vs. conductivity) [22] [25].

Step 9: Multivariate Analysis Investigate complex interactions between multiple variables simultaneously using advanced visualization techniques. Heatmaps, parallel coordinate plots, and clustering methods can reveal higher-order relationships in materials data that simple pairwise analysis might miss [22].

Step 10: Documentation and Insight Communication Clearly document all EDA findings, discovered patterns, anomalies, informative variables, data limitations, and recommended next steps. Create a comprehensive report with key visualizations and statistically significant results to guide subsequent materials research directions [22].

EDA Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive EDA workflow for materials datasets, showing the sequential steps and their relationships:

Quantitative Data Presentation and Visualization Methods

Structured Data Presentation Framework

Effective presentation of quantitative data is essential for communicating materials research findings. The table below summarizes common quantitative analysis types and their appropriate presentation formats for materials datasets:

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis Methods and Presentation Formats for Materials Data

| Analysis Type | Appropriate Quantitative Methods | Presentation Format | Materials Science Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Descriptive statistics (range, mean, median, mode, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis) [24] | Histograms [25], frequency polygons [26], line graphs, descriptive tables | Distribution of individual material properties (hardness, strength, conductivity) |

| Univariate Inferential Analysis | T-test, Chi-square test [24] | Summary tables of test results, contingency tables [24] | Comparing property means between two material groups |

| Bivariate Analysis | T-tests, ANOVA, Chi-square, correlation analysis [24] | Scatter plots [26] [22], summary tables, contingency tables [24] | Relationship between processing parameters and material properties |

| Multivariate Analysis | ANOVA, MANOVA, multiple regression, logistic regression, factor analysis [27] [24] | Summary tables, correlation matrices, loading plots | Complex processing-structure-property relationships |

Visualization Techniques for Materials Data

The appropriate selection of visualization methods is crucial for effectively communicating patterns in materials data. Different visualization techniques serve distinct purposes in EDA:

Histograms provide a pictorial representation of frequency distribution for quantitative materials data. They consist of rectangular, contiguous blocks where the width represents class intervals of the variable and height represents frequency. For continuous materials data (e.g., particle size distributions), care is needed in defining bin boundaries to avoid ambiguity, typically by defining boundaries to one more decimal place than the measurement precision [26] [25].

Frequency Polygons are obtained by joining the midpoints of histogram blocks, creating a line representation of distribution. These are particularly useful when comparing distributions of multiple materials datasets on the same diagram, such as property distributions for different material classes [26].

Scatter Plots serve as essential tools for investigating relationships between two quantitative variables in materials research. They effectively reveal correlations, trends, and outliers in bivariate relationships, such as the relationship between processing temperature and resulting grain size [26] [22].

Line Diagrams primarily display time trends of material phenomena, making them ideal for representing kinetic processes, aging effects, or property evolution during processing. These are essentially frequency polygons where class intervals represent time [26].

Statistical Techniques for Materials Data Exploration

Advanced Analytical Methods

Beyond basic descriptive statistics, materials researchers can employ sophisticated analytical techniques during EDA to uncover complex patterns:

Regression Analysis models relationships between variables to predict and explain material behavior. The core regression equation Y = β0 + β1*X + ε estimates how a dependent variable (e.g., material property) is influenced by independent variables (e.g., processing parameters) [27]. Different regression types address various materials data characteristics:

- Linear Regression: Examines linear relationships between variables

- Logistic Regression: Suitable for predicting categorical outcomes (e.g., pass/fail performance)

- Polynomial Regression: Addresses curvilinear relationships common in materials behavior

- Regularized Regression: Introduces penalties to prevent overfitting with high-dimensional data [27]

Factor Analysis serves as a dimensionality reduction technique that identifies underlying latent variables in complex materials datasets. It simplifies datasets by reducing observed variables into fewer dimensions called factors, which capture shared variances among variables. This method is particularly valuable for identifying fundamental material descriptors from numerous measured characteristics [27].

Monte Carlo Simulation employs random sampling to estimate complex mathematical problems and quantify uncertainty in materials models. This technique explores possible outcomes by simulating systems multiple times with varying inputs, providing insights into potential variability and extreme scenarios that deterministic models might overlook [27].

Experimental Design Integration

Proper experimental design is fundamental to generating materials data suitable for meaningful EDA. The distinction between study design and statistical analysis is particularly important in materials research, where data collection procedures fundamentally influence analytical approaches [28]. A well-constructed experimental design serves as a roadmap, clearly specifying how independent variables (e.g., composition, processing parameters) interact with dependent variables (e.g., material properties) and when measurements occur [28].

For materials researchers, explicitly defining the experimental design before data collection ensures that the resulting dataset supports robust EDA. This includes specifying the number of independent variables (factors), their levels, measurement sequences, and control strategies. Such clarity in design facilitates more effective exploratory analysis by establishing a logical framework for understanding variable relationships [28].

Computational Tools for Materials EDA

The following table summarizes essential software tools and libraries for implementing EDA in materials research:

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Materials Data Exploration

| Tool/Library | Primary Function | Specific Applications in Materials EDA |

|---|---|---|

| Pandas (Python) | Data manipulation and cleaning [22] [23] | Loading, cleaning, and manipulating materials experimental data; handling missing values; computing descriptive statistics |

| NumPy (Python) | Numerical computations [22] | Mathematical operations on materials property arrays; matrix operations for structure-property relationships |

| Matplotlib (Python) | Basic visualization [22] [23] | Creating static plots of materials data (histograms, scatter plots, line graphs) |

| Seaborn (Python) | Statistical visualization [22] [23] | Generating advanced statistical graphics for materials data (distribution plots, correlation heatmaps, grouped visualizations) |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | Machine learning and preprocessing [22] | Dimensionality reduction; outlier detection; data transformation; feature selection for materials datasets |

| ggplot2 (R) | Data visualization [22] | Creating publication-quality graphics for materials research findings |

| Integrated Platforms (e.g., Briefer) | Unified analysis environment [23] | Combining SQL, Python, visualization, and documentation in single environment for streamlined materials data exploration |

Implementation Framework Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated tool ecosystem for materials data exploration, showing how different computational resources interact in a typical EDA workflow:

Application to Materials Experimental Design

The integration of EDA within the broader context of materials experimental design creates a powerful framework for knowledge discovery. By employing these techniques at the preliminary stages of research, materials scientists can make informed decisions about subsequent experimental directions, optimize resource allocation, and generate hypotheses grounded in empirical patterns [22] [23].

The iterative nature of EDA aligns particularly well with materials development cycles, where initial findings from exploratory analysis often inform subsequent experimental designs, leading to refined synthesis approaches and characterization strategies. This continuous feedback between exploration and experimentation accelerates materials discovery and optimization while reducing costly false starts [23].

For materials researchers engaged in drug development applications, these EDA techniques provide robust methods for understanding structure-activity relationships, optimizing formulation parameters, and identifying critical quality attributes. The systematic approach to data exploration ensures that development decisions are grounded in comprehensive data understanding rather than isolated observations [22] [20].

By mastering these exploratory data analysis techniques and implementing them through the recommended protocols and tools, materials researchers can extract maximum insight from their experimental datasets, ultimately accelerating the development of new materials with tailored properties and performance characteristics.

Construction of Material Descriptors Using Hölder and Power Means

The development of novel materials, crucial for advancements in sectors from energy storage to pharmaceuticals, is often hampered by the complex, multi-variable nature of material systems. The Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) exemplifies the paradigm shift towards using computational power to accelerate this discovery process [29]. Within this data-driven framework, material descriptors serve as the critical bridge, providing a numerical representation of a material's structure or properties that can be processed by statistical and machine learning (ML) models [29] [30]. The accuracy and universality of these descriptors directly determine the success of predictive models. Simultaneously, the field of statistical mathematics offers powerful tools for understanding and manipulating numerical relationships. This work explores the application of one such tool—the generalization of Hölder's inequality involving power means—to the construction and analysis of robust material descriptors, providing a formal statistical foundation for linking complex atomic environments to macroscopic material properties.

Theoretical Foundation: Hölder's Inequality and Power Means

Power Means and Their Geometric Interpretation

In the context of material descriptor analysis, we often need to aggregate or compare numerical features. The power mean, also known as the generalized mean, provides a flexible framework for this. Formally, the Λ-weighted k-power mean of a vector of positive reals ( x = (x1, x2, ..., x_n) ) is defined as:

[ \mathcal{P}\Lambda^k(x) = \left( \sumi \lambdai {xi}^k \right)^{1/k} \quad \text{for} \quad k \ne 0 ]

and

[ \mathcal{P}\Lambda^0(x) = \prodi {xi}^{\lambdai} ]

where ( \Lambda = (\lambda1, \lambda2, ..., \lambdan) ) is a weight vector such that ( \sumi \lambda_i = 1 ) [31]. This family of means encompasses several important special cases: the arithmetic mean (k=1), the geometric mean (the limit as k approaches 0), and the quadratic mean (k=2). In materials informatics, different exponents can be used to emphasize or de-emphasize extreme values in descriptor data, such as outlier atomic environments in a grain boundary.

Generalization of Hölder's Inequality

The classical Hölder's inequality establishes a relationship between different means. For real vectors ( a, b, ..., z ) and weights ( \Lambda = (\lambdaa, ..., \lambdaz) ) summing to 1, it states that:

[ (a1+...+an)^{\lambdaa}...(z1+...+zn)^{\lambdaz} \ge a1^{\lambdaa}... z1^{\lambdaz}+...+an^{\lambdaa}... zn^{\lambdaz} ]

This can be reinterpreted in terms of power means: the arithmetic mean (a power mean with k=1) of products is dominated by the weighted geometric mean (a power mean with k=0) of the arithmetic means [31].

A significant generalization of this inequality, relevant for multi-scale descriptor analysis, has been established. For arbitrary weight-vectors ( \Lambda1 ) and ( \Lambda2 ) and exponents ( k2 \ge k1 ), the following inequality holds:

[ \text{col}\mathcal{P}{\Lambda1}^{k1}(\ \text{row}\mathcal{P}{\Lambda2}^{k2}(M)\ ) \ \ge\ \text{row}\mathcal{P}{\Lambda2}^{k2}(\ \text{col}\mathcal{P}{\Lambda1}^{k1}(M)\ ) ]

In simpler terms, for a matrix ( M ) representing a dataset (e.g., rows as different materials and columns as different descriptor components), applying a higher-power mean across rows followed by a lower-power mean down columns always yields a result at least as large as applying the operations in the reverse order [31]. This result is mathematically rigorous and has been proven in the context of functional analysis, generalizing the work of Kwapień and Szulga.

Mathematical Workflow for Descriptor Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of applying power means and Hölder's inequality in the construction and analysis of material descriptors:

Application to Materials Informatics

The Critical Role of Descriptors in Machine Learning

In materials machine learning, a descriptor is defined as a descriptive parameter for a material property [29] [30]. The process of predicting material properties from atomic structure typically involves three key steps, as identified in grain boundary research:

- Description: The atomic structure is encoded into a feature matrix or vector.

- Transformation: The variable-sized descriptor is converted to a fixed-length representation comparable across all structures in a dataset.

- Machine Learning: A model is applied to predict properties from the transformed descriptors [30].

The generalized Hölder inequality provides a mathematical framework for optimizing the transformation step, particularly when dealing with variable-sized atomic clusters and grain boundaries.

Quantitative Comparison of Common Material Descriptors

The choice of descriptor significantly impacts prediction accuracy. The following table summarizes the performance of various descriptors in predicting grain boundary energy in aluminum, demonstrating their relative effectiveness.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Material Descriptors for Grain Boundary Energy Prediction in Aluminum [30]

| Descriptor Name | Full Name | Key Characteristics | Best Model | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | R² Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOAP | Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions | Physics-inspired; captures local atomic environments | Linear Regression | 3.89 mJ/m² | 0.99 |

| ACE | Atomic Cluster Expansion | Systematic expansion of atomic correlations | Linear Regression | 5.86 mJ/m² | 0.98 |

| SF | Strain Functional | Based on local strain fields | MLP Regression | 6.02 mJ/m² | 0.98 |

| ACSF | Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions | Invariant to rotation and translation | Linear Regression | 16.02 mJ/m² | 0.83 |

| CNA | Common Neighbor Analysis | Classifies local crystal structure | MLP Regression | 37.13 mJ/m² | 0.18 |

| CSP | Centrosymmetry Parameter | Measures local lattice disorder | MLP Regression | 40.31 mJ/m² | 0.11 |

| Graph | Graph2Vec | Graph-based representation of structure | MLP Regression | 41.10 mJ/m² | 0.06 |

Workflow for Descriptor-Driven Property Prediction

The application of descriptors in a predictive model, highlighting steps where power means can be integrated, is shown below.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Power Mean-Based Descriptor for Grain Boundary Energy

This protocol details the steps for constructing a material descriptor for grain boundary energy using power means, based on methodologies from recent literature [30].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Materials Science

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulation to calculate reference GB energies. | Used to generate the ground-truth dataset [30]. |

| Database of 7,304 Al GBs | Provides comprehensive coverage of crystallographic character. | Should cover the 5-dimensional macroscopic space [30]. |

| SOAP Descriptor | Describes the local atomic environment of each atom. | A physics-inspired descriptor; yields a feature matrix M [30]. |

| Python with NumPy/SciKit-Learn | For implementing power means, transformations, and ML models. | R, SPSS, or SAS are also viable alternatives [32]. |

| Power Mean Function (ℙₖ) | The core mathematical operation for aggregating descriptor components. | Code implementation for k ≠ 0 and k → 0 (geometric mean). |

| Linear Regression / MLP Regression | Machine learning model to map the final descriptor to GB energy. | Linear Regression performed best with SOAP [30]. |

Procedure:

- Data Generation: Perform energy calculations for all grain boundaries in the database using molecular dynamics software (e.g., LAMMPS) to create the target property dataset [30].

- Initial Description: For each GB structure, compute the SOAP descriptor. This results in a feature matrix ( M ) where rows typically correspond to individual atoms in the GB and columns correspond to the SOAP vector components for that atom.

- Transformation via Power Means: a. Choose two exponents satisfying ( k2 \ge k1 ). For example, ( k2 = 1 ) (arithmetic mean) and ( k1 = 0 ) (geometric mean). b. Apply the first power mean with exponent ( k2 ) across the rows (atom-wise) of matrix ( M ). This step aggregates information across the different components of the SOAP vector for each atom, resulting in a single value per atom. c. Apply the second power mean with exponent ( k1 ) down the column (component-wise) of the resulting vector. This step aggregates the values across all atoms in the GB, resulting in a single, fixed-length descriptor value for the entire grain boundary. d. The generalized Hölder inequality guarantees that ( \text{col}\mathcal{P}{k1}(\ \text{row}\mathcal{P}{k2}(M)\ ) \ \ge\ \text{row}\mathcal{P}{k2}(\ \text{col}\mathcal{P}{k1}(M)\ ) ). This bound can be used to validate the implementation.

- Model Training and Validation: a. Use the transformed fixed-length descriptor as input for a machine learning model (e.g., Linear Regression). b. Train the model on a subset of the data to predict the calculated GB energies. c. Validate the model on a held-out test set, reporting both Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² values to ensure accuracy and correlation, not just low error [30].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Data Quality Assurance for Descriptor Databases

High-quality input data is non-negotiable for reliable descriptor development. This protocol outlines the data cleaning process prior to analysis [14].

Procedure:

- Check for Duplications: Identify and remove identical copies of data, leaving only unique participant/measurement data. This is critical for data collected online where duplicate submissions can occur [14].

- Handle Missing Data: a. Distinguish between data that is missing (omitted but expected) and not relevant (e.g., "not applicable"). b. Establish a percentage threshold for inclusion/exclusion (e.g., remove samples with >50% missing data). c. Use a statistical test like Little's Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test to analyze the pattern of missingness. If data is not MCAR, consider advanced imputation methods (e.g., estimation maximization) [14].

- Check for Anomalies: a. Run descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean) for all measures. b. Examine responses to ensure they fall within expected and physically plausible ranges (e.g., Likert scales are within their defined boundaries, bond lengths are positive). Identify and correct anomalies before full analysis [14].

- Data Summation and Psychometric Properties: a. Summate items to constructs or clinical definitions as per instrument manuals (e.g., sum items of the GAD7 to get an anxiety score). b. Establish psychometric properties of standardized instruments. Report Cronbach's alpha (>0.7 is acceptable) to ensure internal consistency of the measures used [14].

The integration of rigorous statistical inequalities, specifically the generalization of Hölder's inequality for power means, provides a formal and powerful framework for constructing and analyzing material descriptors. This approach is particularly potent for addressing the challenge of variable-sized inputs, such as atomic clusters and grain boundaries, by guiding the transformation of complex feature matrices into fixed-length descriptors. When combined with high-quality data assurance protocols and high-performing, physics-inspired descriptors like SOAP, this mathematical foundation enables the development of highly accurate predictive models for material properties. This synergy between advanced statistics and materials informatics is a critical enabler for accelerating the discovery and development of new materials, from more efficient battery components to novel pharmaceutical compounds.

In materials science and drug development, the robustness of machine learning (ML) and statistical models is fundamentally constrained by two pervasive data challenges: modest dataset sizes and highly diverse chemistries. Modest datasets, often resulting from the high cost and time requirements of experimental data generation, can lead to models that fail to generalize. Simultaneously, chemical diversity—encompassing a vast range of elements, bonding types, and molecular structures—poses a significant challenge for creating models that perform reliably across the breadth of chemical space, rather than just on narrow, well-represented domains. The convergence of these issues often results in imbalanced data, where critical minority classes (e.g., specific material properties or active drug molecules) are underrepresented, causing significant bias in predictive models [33]. This application note details practical protocols and solutions to navigate these challenges, enabling the development of more reliable and generalizable models for experimental research.

Application Notes

The Core Challenges in Chemical Data

- Imbalanced Data in Chemistry: In many chemical datasets, the distribution of classes is highly skewed. For instance, in drug discovery, active compounds are vastly outnumbered by inactive ones, and in property prediction, toxic substances may be overrepresented. This imbalance causes standard ML algorithms, which assume uniform class distribution, to become biased toward the majority class, severely compromising their predictive accuracy for the underrepresented—yet often critically important—minority classes [33].

- The Scale and Diversity Problem: Traditional computational datasets have been limited in both size and chemical scope. For example, past molecular datasets were often restricted to small molecules (averaging 20-30 atoms) and a handful of elements, failing to capture the complexity of real-world systems like biomolecules and metal complexes [34] [35]. This lack of diversity means that models trained on them are ill-equipped to handle the vast, unexplored regions of chemical space.

A promising development to address the diversity challenge is the creation of large-scale, chemically diverse datasets. The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset represents a significant leap forward [34] [35].

Table 1: Key Features of the OMol25 Dataset

| Feature | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | Over 100 million DFT calculations [35] | Unprecedented scale for model training |

| Computational Cost | ~6 billion CPU core-hours [35] | Reflectos the dataset's magnitude and value |

| Elemental Diversity | 83 elements across the periodic table [34] | Enables modeling of heavy elements and metals |

| System Size | Molecular systems of up to 350 atoms [34] | Allows simulation of scientifically relevant, complex systems |

| Chemical Focus Areas | Biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [35] | Covers critical areas for materials science and drug development |

For challenges related to modest dataset sizes, including inherent imbalances, methodological innovations are key. A comprehensive review of ML for imbalanced data in chemistry highlights four primary strategic approaches [33]:

- Resampling Techniques: Adjusting the dataset composition to balance class proportions.

- Data Augmentation: Generating new, synthetic data points for the minority class.

- Algorithmic Approaches: Modifying ML algorithms to be more sensitive to minority classes.

- Feature Engineering: Selecting or creating features that better distinguish between classes.

Quantitative Impact of Data Curation

Beyond sheer scale, the principle of "diversity over scale" is gaining empirical support. Research on Chemical Language Models (CLMs) indicates that beyond a certain threshold, simply scaling model size or dataset volume yields diminishing returns. Instead, a deliberate dataset diversification strategy has been shown to substantially increase the diversity of successful molecular discoveries ("hit diversity") with minimal negative impact on the overall success rate ("hit rate"). This finding motivates a strategic shift from a scale-first to a diversity-first training paradigm for molecular discovery [36].

Protocols

This section provides detailed methodological guidance for implementing the discussed solutions.

Protocol 1: Leveraging Large-Scale Diverse Datasets for Pre-Training

Purpose: To build a robust, general-purpose ML model for molecular properties by pre-training on the OMol25 dataset, which can later be fine-tuned for specific, data-scarce tasks. Principle: Transfer learning from a large, diverse source dataset mitigates the risks of overfitting and poor generalization associated with training on small, specialized datasets from scratch [34] [35].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Download the OMol25 dataset from the official repository.

- Model Selection: Choose a suitable model architecture (e.g., a graph neural network or transformer) for learning from 3D molecular structures.

- Pre-training Task: Train the model on a core task, such as predicting the total energy or atomic forces of a system, using the OMol25 data. This forces the model to learn fundamental principles of quantum chemistry.

- Feature Extraction: Use the pre-trained model to generate meaningful molecular representations (feature vectors) for your proprietary, smaller dataset.

- Fine-Tuning: Use the pre-trained model's weights as a starting point and perform additional training (fine-tuning) on your specific, target dataset to adapt the model to your precise predictive task.

The following workflow visualizes this transfer learning protocol:

Protocol 2: Addressing Data Imbalance with SMOTE

Purpose: To rectify class imbalance in a chemical dataset (e.g., active vs. inactive compounds) by generating synthetic samples for the minority class, thereby improving model performance. Principle: The Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) creates artificial data points for the minority class by interpolating between existing neighboring instances in feature space, balancing the class distribution without mere duplication [33].

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Clean your dataset and featurize your molecules (e.g., using molecular fingerprints or descriptors). Split into training and test sets. Apply SMOTE only to the training set to avoid data leakage.

- Identify Minority Class: Determine which class (e.g., "active compounds") is underrepresented.

- Parameter Selection: Choose the number of nearest neighbors

k(typically 5) and set the desired oversampling ratio. - Synthetic Sample Generation: For each minority class instance

x_i: a. Find itsknearest neighbors in the feature space that also belong to the minority class. b. Randomly select one of these neighbors,x_zi. c. Create a new synthetic sample:x_new = x_i + λ * (x_zi - x_i), whereλis a random number between 0 and 1. - Model Training: Train your chosen ML classifier (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) on the newly balanced training dataset.

- Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out, original (unmodified) test set.

The following diagram illustrates the core SMOTE algorithm:

Table 2: Common Data Augmentation and Resampling Techniques

| Technique | Category | Brief Description | Example Application in Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMOTE [33] | Resampling (Oversampling) | Generates synthetic minority class samples by interpolating between neighbors. | Balancing active/inactive compounds in virtual screening [33]. |

| Borderline-SMOTE [33] | Resampling (Oversampling) | Focuses SMOTE on minority instances near the decision boundary. | Predicting mechanical properties of polymer materials [33]. |

| ADASYN [33] | Resampling (Oversampling) | Adaptively generates more samples for "hard-to-learn" minority instances. | Can be applied to catalyst design and protein engineering tasks. |

| Data Augmentation via LLMs | Data Augmentation | Uses Large Language Models to generate novel, valid molecular structures. | Emerging method for expanding chemical datasets [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

A selection of key computational and data resources essential for tackling dataset challenges is provided in the table below.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Challenges

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Dataset Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [34] [35] | Dataset | A massive, open-source repository of DFT-calculated molecular properties. | Provides a diverse pre-training base for transfer learning, mitigating small data and diversity issues. |

| SMOTE & Variants [33] | Algorithm | A family of oversampling algorithms for balancing imbalanced datasets. | Directly addresses class imbalance in chemical classification tasks (e.g., activity prediction). |

| Power Analysis [37] | Statistical Method | A priori calculation of the required sample size to detect a given effect size. | Informs experimental design to ensure datasets are adequately sized from the outset, avoiding "modest size" problems. |

| Chemical Language Models (CLMs) [36] | AI Model | Transformer-based models trained on chemical representations (e.g., SMILES). | Can be used for data augmentation and for exploring chemical space with a diversity-first focus. |

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Materials Research

Machine Learning and Statistical Learning (SL) Techniques for Materials Design

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from experience-driven and trial-and-error approaches to a data-driven paradigm powered by machine learning (ML) and statistical learning (SL) [38]. This paradigm enables researchers to rapidly navigate complex, high-dimensional design spaces, accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel materials with tailored properties [39]. ML accelerates every stage of the materials discovery pipeline, from initial design and synthesis to characterization and final application, often matching the accuracy of traditional, computationally expensive ab initio methods at a fraction of the cost [39]. This review provides application notes and detailed protocols for integrating these powerful techniques into materials experimental design research, with a specific focus on statistical methods.

Core to this approach is the concept of materials intelligence, where ML-driven strategies enable performance-oriented structural optimization through inverse design and generative models [38]. In practice, this involves using multi-scale modeling that combines established physical mechanisms with data-driven methods, creating a cohesive framework that runs through all stages of material innovation [38].

Core ML/SL Techniques: Applications and Protocols

Key Learning Paradigms and Their Applications

ML and SL encompass several learning paradigms, each suited to different types of problems and data availability in materials science. The table below summarizes the primary learning types and their applications in materials design.

Table 1: Machine and Statistical Learning Paradigms in Materials Design

| Learning Paradigm | Primary Function | Example Applications in Materials Design |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning [40] [41] | Model relationships between known input and output data to predict properties or classify materials. | Predicting material properties (e.g., band gap, strength), classifying crystal structures [40]. |

| Unsupervised Learning [40] [41] | Identify hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in data without pre-defined labels. | Clustering similar material compositions, dimensionality reduction for visualization, anomaly detection in synthesis data [40]. |

| Reinforcement Learning [40] | Train an agent to make a sequence of decisions by rewarding desired outcomes. | Optimizing synthesis parameters in autonomous laboratories [40]. |

| Ensemble Learning [41] | Combine multiple models to improve predictive performance and robustness. | Random Forests for property prediction, boosting algorithms for stability classification [41]. |

Essential Algorithms and Models

A diverse toolkit of algorithms is employed to tackle the varied challenges in materials informatics. The selection of a specific model depends on the problem type, data size, and desired interpretability.

- Dimensionality Reduction (e.g., PCA, LDA): These techniques are crucial for visualizing high-dimensional materials data (e.g., from combinatorial libraries) and identifying the most influential descriptors that govern material behavior [41].

- Classification and Regression Models: Techniques such as k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and logistic regression are used for categorization tasks, while linear regression, ridge, and lasso are workhorses for predicting continuous properties [41]. Lasso regression is particularly valuable for feature selection in datasets with many potential descriptors.

- Tree-Based Methods (e.g., Decision Trees, Random Forests): These models are highly effective for both classification and regression tasks and provide insights into feature importance, helping researchers understand which factors most significantly impact a target property [41].

- Neural Networks and Deep Learning: These powerful models can learn complex, non-linear relationships in large datasets. They are applied to tasks ranging from predicting complex property relationships to analyzing microstructural images from microscopy [41].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: ML-Guided Materials Discovery Pipeline

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for an ML-driven materials discovery project, from data collection to experimental validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools