Standardized Protocols for Human Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Sampling to Reporting

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing standardized protocols in human microbiome research, addressing critical needs from foundational concepts to clinical translation.

Standardized Protocols for Human Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Sampling to Reporting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing standardized protocols in human microbiome research, addressing critical needs from foundational concepts to clinical translation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the essential role of standardization through established initiatives like the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS), detailed methodological workflows for sample collection and analysis, troubleshooting common experimental challenges, and validation through reporting guidelines like STORMS. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance data reproducibility, comparability across studies, and accelerate the development of reliable microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics.

The Critical Need for Standardization in Human Microbiome Research

The study of the human microbiome has revealed the profound influence that complex microbial communities have on human physiology, nutrition, and immunity. Standardized protocols are crucial for ensuring that data from different studies are comparable and reproducible. Major international initiatives have emerged to address this need, including the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS), the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), and the Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract (MetaHIT) project. These consortia recognize that variability in results can stem from multiple steps in the microbiome study process, with DNA extraction identified as a major source of experimental variability [1]. The coordination of these efforts through organizations like the International Human Microbiome Consortium (IHMC) has been essential in developing and implementing standardized procedures across sample collection, DNA extraction, sequencing, and data analysis [2].

The International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS)

The IHMS project specifically coordinated the development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) to optimize data quality and comparability in human microbiome research [3]. Its primary focus was on standardizing procedures across three fundamental areas: (1) collecting and processing human samples, (2) sequencing human-associated microbial genes and genomes, and (3) organizing and analyzing the gathered data [2]. IHMS concentrated on gut microbial communities due to their complexity, abundance, and significant impact on human health and disease, utilizing Quantitative Metagenomics as its primary analytical approach for superior resolution compared to 16S rRNA sequencing [2].

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP)

The NIH Human Microbiome Project was a landmark initiative initiated under the NIH Roadmap to characterize the human microbiome and analyze its role in human health and disease [4]. The project established comprehensive protocols for core microbiome sampling across multiple body sites, with detailed Manuals of Procedures (MOPs) governing everything from sample collection to data publication [4]. The HMP implemented rigorous organizational structures including Steering Committees to oversee protocol development and adherence, emphasizing Good Clinical Practice compliance and protection of human subjects throughout the research process [4].

The Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract (MetaHIT)

MetaHIT was a large-scale EU FP7 project that generated foundational insights into the human gut microbiome through deep metagenomic sequencing [5]. The project established a comprehensive catalog of 3.3 million non-redundant microbial genes from fecal samples of 124 European individuals - a gene set approximately 150 times larger than the human gene complement [5]. MetaHIT's pioneering use of Illumina-based metagenomic sequencing demonstrated that short-read technologies could effectively characterize the genetic potential of ecologically complex environments, with their gene catalog capturing an overwhelming majority of the prevalent microbial genes in the studied cohort [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Microbiome Standardization Initiatives

| Initiative | Primary Focus | Key Outputs | Sample Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHMS | Developing SOPs for comparability across studies | SOPs for sample collection, processing, sequencing, and data analysis [3] [2] | Gut microbiome (fecal samples) [2] |

| HMP | Characterizing human microbiome across body sites | Core Microbiome Sampling Protocols, Manuals of Procedures [4] | Multiple body sites (GI tract, oral, skin, etc.) [4] |

| MetaHIT | Creating reference gene catalog for gut microbiome | 3.3 million non-redundant microbial gene catalog [5] | European gut microbiome (fecal samples) [5] |

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

DNA Extraction Protocols

DNA extraction methodologies represent a critical source of variability in microbiome studies. The IHMS study evaluated multiple DNA extraction protocols and found they contributed significantly to experimental variability, leading to the development of standardized SOPs for fecal sample DNA extraction [1] [6]. The comparison between HMP and MetaHIT extraction methods revealed important methodological differences: the MetaHIT protocol yielded higher eukaryotic genome mapping, while the HMP protocol had greater bacterial genome mapping reads, with both methods detecting differing abundances of specific genera [1].

For low-biomass samples (such as tissue samples and bodily fluids), specialized approaches are required to minimize contamination, including extensive environmental controls and complementary proof-of-life demonstrations through microbial culture and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [1]. Furthermore, extraction protocols optimized for bacteria may yield biased results for other microbes like fungi, protists, and viruses, indicating a need for either specialized or comprehensively optimized methods [1].

Sequencing and Data Analysis Approaches

The sequencing methodologies employed by these initiatives have evolved to encompass both 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and whole metagenome shotgun sequencing. The cHMP protocol, for instance, specifies amplification of the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using 341F and 805R primers, with stringent quality controls requiring a minimum of 20,000 quality-controlled reads for fecal specimens and 5,000 for other human tissue specimens [7]. For whole metagenome sequencing, rigorous preprocessing steps are applied, including trimming low-quality bases, removing duplicate reads, and filtering human-derived reads by alignment against human reference genomes [7].

Table 2: Sequencing Methodologies and Quality Control Standards

| Sequencing Type | Target Region | Primer Sequences | Quality Thresholds | Data Processing Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon | V3-V4 hypervariable region | 341F: 5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3'805R: 5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3' [7] | ≥20,000 reads (fecal)≥5,000 reads (other tissues) [7] | Quality filtering, OTU clustering, taxonomic assignment |

| Whole Metagenome Shotgun | Entire microbial DNA | Not applicable | Bray-Curtis dissimilarity <0.3 between parallel tests [7] | Trimming low-quality bases, duplicate removal, human read filtering [7] |

Sample Collection and Storage Standards

The IHMS developed four distinct SOPs for sample collection based on transfer time to the laboratory [2]:

- SOP 1: Transfer within 4 hours at room temperature

- SOP 2: Transfer between 4-24 hours with anaerobic conditions (Anaerocult)

- SOP 3: Transfer between 24 hours-7 days with immediate freezing at -20°C

- SOP 4: Use of stabilization solution for room temperature preservation

The cHMP protocols further elaborate that samples destined for analysis within 2 hours should be transported in an icebox, while those with 2-4 hour transit should be refrigerated at 4°C, and deliveries exceeding 4 hours require freezing at -20°C with transport within 24 hours under maintained cold chain conditions [7]. All specimens should ideally reach analytical institutions within 72 hours of collection, with storage at -70°C to -80°C upon receipt to minimize freeze-thaw cycles [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

End-to-End Workflow for Human Microbiome Studies

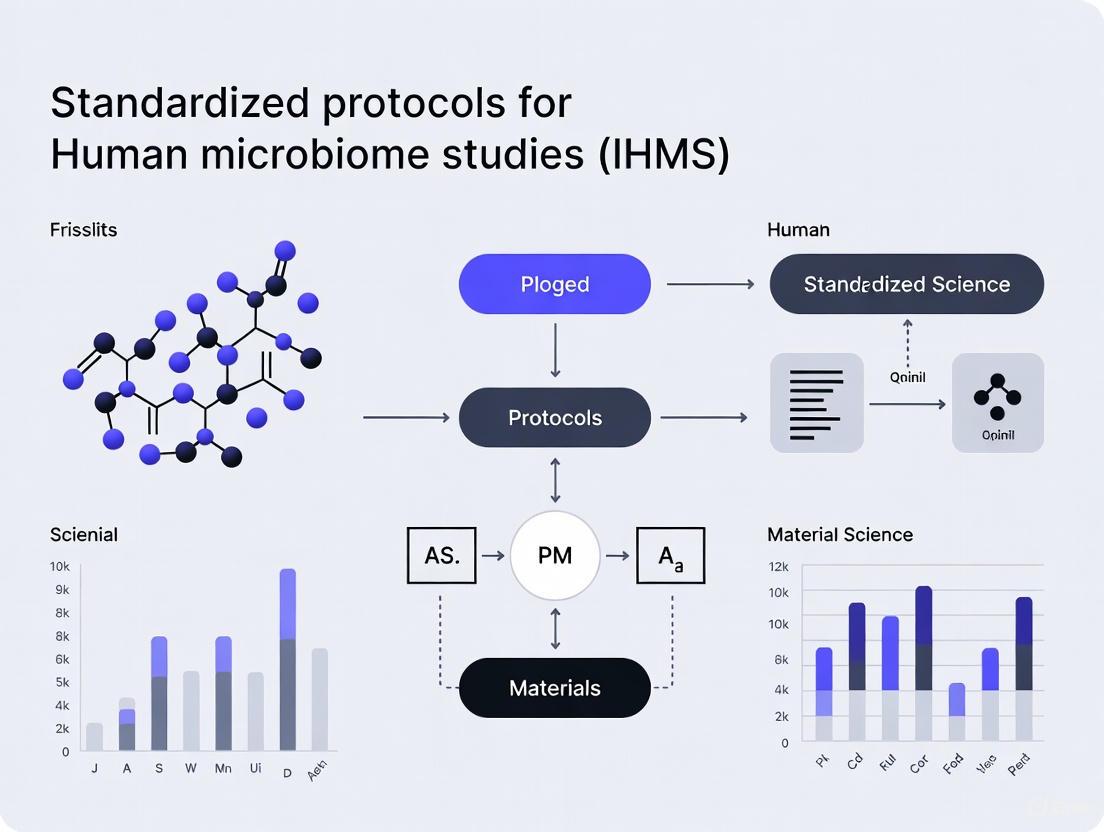

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for standardized human microbiome research, integrating processes from all major initiatives:

DNA Extraction Protocol (IHMS SOP 007 V2)

The IHMS SOP 007 V2 provides a standardized protocol for DNA extraction from fecal samples for metagenomic profiling [6]. This protocol was selected from an inventory of multiple extraction methods and validated for inter-laboratory reproducibility. The specific steps include:

- Sample Preparation: Frozen fecal samples are thawed at room temperature and homogenized with a spatula [7].

- Cell Lysis: Utilizes a combination of mechanical and enzymatic lysis appropriate for robust bacterial cell walls.

- DNA Purification: Removal of contaminants, proteins, and inhibitors through column-based or solution-based purification.

- DNA Elution: Elution in appropriate buffer for downstream applications.

- Quality Assessment: Quantification via fluorometry and quality verification through gel electrophoresis or microfluidic analysis.

The protocol is designed for high-throughput processing of large sample sets while maintaining reproducibility across different laboratories [6]. The obtained DNA is subsequently analyzed according to sequencing standards (IHMS SOP 009, 010 & 011 V1) [6].

Quality Control and Reference Materials

Implementation of comprehensive quality control measures is essential for reliable microbiome data. The NIST Human Fecal Material Reference Material (RM) represents a significant advancement, providing eight frozen vials of exhaustively studied human feces suspended in aqueous solution with extensive characterization data [8]. This RM enables:

- Method Comparison: Serving as a gold standard for evaluating diverse measurement approaches

- Reproducibility Assessment: Allowing laboratories to verify consistent results across platforms

- Accuracy Validation: Providing ground truth for analytical accuracy

Additionally, the use of mock communities - artificial consortia of known microbial strains - provides a controlled standard for validating sequencing accuracy and bioinformatic pipelines [1]. For low-biomass samples, negative controls (blanks) are essential for identifying potential contamination throughout the processing pipeline [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Standardized Microbiome Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| NIST Human Fecal Reference Material | Quality control standard for gut microbiome studies | Eight frozen vials of characterized human feces; provides benchmark for method comparison [8] |

| Mock Communities | Positive controls for sequencing and analysis | Defined mixtures of microbial strains with known composition; validates analytical accuracy [1] [7] |

| Anaerocult | Creates anaerobic conditions for sample storage | Used in IHMS SOP 2 for samples transferred 4-24 hours post-collection [2] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (IHMS-approved) | Standardized DNA isolation from fecal samples | Protocols maximizing ease of use and reproducibility; select kits validated for inter-laboratory consistency [1] [6] |

| Stabilization Solutions | Preserves microbial composition at room temperature | Enables sample shipment without freezing; used in IHMS SOP 4 [2] |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of target regions for amplicon sequencing | 341F/805R for V3-V4 region [7]; standardized across initiatives for comparability |

| Host DNA Depletion Reagents | Reduces human DNA contamination in host-rich samples | Critical for oral, tissue, and low-biomass samples; includes commercial kits and enzymatic methods [7] |

Impact and Future Directions

The standardization efforts led by IHMS, HMP, and MetaHIT have fundamentally transformed human microbiome research by enabling reliable comparisons across studies and laboratories. The development of publicly accessible SOPs has facilitated consistent sample collection, processing, and data analysis [2]. The creation of extensive reference catalogs, such as MetaHIT's 3.3 million gene catalog, has provided foundational resources for the research community [5]. Recent advances like the NIST reference material represent the next evolution in standardization, providing quantitatively characterized standards for validation and quality control [8].

Future directions in microbiome standardization include addressing the challenges of low-biomass samples through enhanced contamination controls and specialized processing protocols [1]. There is also growing recognition of the need for appropriate use of population descriptors in microbiome research to avoid biological determinism while acknowledging the societal factors that shape microbial exposures [9]. The continued refinement of standards across the research lifecycle - from sample collection to data sharing - will be essential for realizing the potential of microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics [7] [8].

The Impact of Non-Standardized Methods on Data Reproducibility

The field of human microbiome studies has revealed the profound influence of microbial communities on human health and disease, driving its integration into biomedical and drug development research. However, the absence of standardized methods across laboratories has created a significant reproducibility barrier, challenging the translation of findings into reliable clinical applications. Microbiome research is particularly vulnerable to methodological variability due to its complex, high-dimensional data and sensitivity to technical artifacts. As noted in a recent analysis, "enthusiasm for microbiome research has outpaced agreement upon experimental best practices," leaving labs to often use cobbled-together workflows [10]. This application note details the specific impacts of non-standardized protocols and provides a structured framework to enhance reproducibility, supporting the broader objectives of the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS) initiative.

The Consequences of Methodological Variability

Methodological inconsistencies introduce bias and variability at nearly every stage of microbiome research, from sample collection to computational analysis. The following sections quantify these impacts and their effect on data interpretation.

Impact of Pre-Analytical and Analytical Variability

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Methodological Variations on Microbiome Data

| Methodological Stage | Observed Variation | Consequence on Data |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Up to 100-fold difference in DNA yield between protocols [10] | Distorted ratios of major phyla (e.g., Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes); under-representation of Gram-positive bacteria [10]. |

| Sample Storage & Handling | Microbial "blooms" during transport/ storage [10] | Altered community representation, compromising profile accuracy [10]. |

| Bioinformatics Analysis | Organism identification differing by up to 3 orders of magnitude across 11 tools [10] | Inconsistent taxonomic profiles and conclusions from identical raw data [10]. |

| 16S rRNA Region Selection | Variable amplification efficiency across taxa [11] | Incomplete or biased representation of true microbial diversity [11]. |

| Low Microbial Biomass Samples | Contamination can comprise "most or all" of the signal [11] | False positives and erroneous associations, severely misleading conclusions [11]. |

The Cumulative Effect on Cross-Study Comparison

The individual variations detailed in Table 1 have a compounding effect, making meta-analyses and comparisons across different studies exceptionally difficult. A stark example is the comparison between the two largest early human microbiome projects, the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) and MetaHIT, which concluded that "differences in the DNA extraction protocols led to significant changes in the observed ratios of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes" [10], two of the most abundant and frequently studied phyla in the gut. This type of variability means that observed differences between, for example, healthy and diseased cohorts in one study might not be replicable in another, not due to a lack of biological effect, but because of technical discrepancies.

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Microbiome Science

To mitigate the issues described above, the following protocols, aligned with the STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist [12], provide a framework for reproducible human microbiome research.

Protocol 1: Standardized Sample Collection and Storage

The first critical step is preserving the in-vivo microbial community structure from the moment of collection.

1.1 Gut Microbiota (Stool Sampling):

- Collection: Collect fresh stool and immediately proceed to preservation. For population-level studies, use standardized commercial kits (e.g., OMNIgene Gut Kit) or preserve in 95% ethanol for field collection [11].

- Storage: Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen or immediately place at -80°C for long-term storage. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Note that while freezing preserves the possibility of subsequent culturing, fixatives kill microorganisms [13].

1.2 Skin and Respiratory Microbiota (Low-Biomass Sites):

- Collection: Use consistent swab materials and techniques (e.g., combination of razor scraping and swabbing for skin) [13]. For respiratory samples, be aware that lavage fluid volume can be highly variable and consider dilution as a factor [13].

- Controls: It is essential to include negative controls (e.g., sterile swabs) processed identically to samples to account for contaminating DNA from reagents and the environment [13] [11].

- Storage: Immediate freezing at -80°C is critical.

1.3 General Principles:

- Consistency: Keep storage conditions consistent for all samples in a study.

- Metadata: Record time-to-freezing, preservative lot numbers, and any deviations.

Protocol 2: DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

This stage is a major source of bias and requires rigorous standardization and control.

2.1 DNA Extraction:

- Standardization: Use a single, validated DNA extraction kit lot for all samples in a study to minimize batch effects [11]. The protocol should be mechanistically suited for a wide range of organisms (e.g., effective lysis for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria) [10].

- Validation with Mock Communities: Include a well-defined mock microbial community (e.g., from Zymo Research or ATCC) with each extraction batch. This community, comprising known abundances of diverse species, serves as a process control to benchmark the accuracy and reproducibility of the entire wet-lab workflow [10].

2.2 Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Amplicon Sequencing (16S rRNA): Select primer sets validated for the taxonomic groups of interest (e.g., ensure archaea are amplified if relevant) [10]. Use a defined PCR cycle count to minimize amplification bias.

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Use standardized input DNA amounts and library prep kits. Include a positive control, such as a non-biological DNA sequence spike-in, to monitor amplification efficiency [11].

Protocol 3: Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

Standardized computational pipelines are necessary to transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful results.

3.1 Bioinformatic Profiling:

- Pipeline Selection: Choose established pipelines (e.g., DADA2 for amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or specific tools for shotgun metagenomics) and maintain consistent parameters and reference databases for the entire dataset [14].

- Quality Control: Process positive controls (mock communities) and negative controls alongside experimental samples. The mock community should yield the expected profile, and negative controls should be used to identify and filter out contaminating sequences, especially in low-biomass studies [11].

3.2 Statistical Analysis and Reporting:

- Data Properties: Account for the compositional, sparse, and high-dimensional nature of microbiome data. Use appropriate statistical models that do not assume a normal distribution [14].

- Confounding Factors: In the study design and statistical model, include critical covariates such as age, diet, antibiotic use, medication, and pet ownership, as all can significantly influence the microbiome [11].

- Multiple Testing: Apply corrections for multiple comparisons (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) when testing thousands of microbial features [11].

- Full Reporting: Adhere to the STORMS checklist to ensure concise and complete reporting of all methodological and analytical steps [12].

Visualizing the Path to Reproducibility

The following diagram synthesizes the protocols above into a coherent workflow, highlighting the parallel processing of experimental samples and essential controls.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Studies

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Communities | Positive process control for DNA extraction and sequencing; benchmarks accuracy and reproducibility [10]. | Commercially available mixes (e.g., Zymo Research BIOMIX, ATCC MSA-1000). Should include Gram-positive/negative bacteria, archaea, fungi. |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kits | Ensure consistent, effective lysis across diverse microbial cell walls, minimizing bias [10]. | Kits validated by IHMS or other consortia. Use a single lot for an entire study. |

| Sample Preservation Kits | Stabilize microbial community at collection for transport/ storage without cold chain [11]. | OMNIgene Gut Kit, 95% ethanol, FTA cards. |

| Negative Control Kits | Identify contaminating DNA from reagents, kits, and laboratory environment [11]. | Sterile swabs, empty collection tubes, molecular grade water. |

| Validated Primer Sets | Ensure comprehensive amplification of target taxa (bacteria, archaea, fungi) in amplicon sequencing [10]. | Primers covering appropriate 16S/18S/ITS regions, verified to amplify organisms of interest. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines & Databases | Standardize the transformation of raw sequence data into taxonomic and functional profiles [14]. | Tools like QIIME 2, DADA2, MOTHUR; curated databases like Greengenes, SILVA. |

Achieving reproducibility in human microbiome research is not an insurmountable challenge, but it requires a disciplined, community-wide commitment to standardization. As outlined in these application notes, the path forward involves the adoption of standardized protocols at every stage, rigorous use of controls, and comprehensive reporting as guided by tools like the STORMS checklist. By integrating these practices, researchers and drug development professionals can generate robust, reliable, and comparable data, thereby solidifying the scientific foundation required to translate microbiome insights into effective clinical diagnostics and therapies.

The advent of high-throughput sequencing has led to an exponential growth in microbiome data, presenting significant challenges in data analysis, interpretation, and cross-study comparison. The FAIR Guiding Principles—making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a critical framework for addressing these challenges in human microbiome research [15] [16]. These principles are particularly relevant within the context of the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS), which aims to optimize data quality and comparability across studies through standardized operating procedures [3].

The microbiome data lifecycle represents a continuous process from sample collection to data reuse, with FAIR principles serving as the foundation at every stage. Proper implementation of these principles enables researchers to transform raw data into meaningful biological insights while ensuring that data remains valuable for future research endeavors. The commitment to FAIR data management is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental aspect of collaborative science that accelerates discovery in microbiome research [16].

The FAIR Principles: Implementation in Microbiome Studies

Findable

The first principle of FAIR emphasizes that data must be easily discoverable by both researchers and computational systems. For microbiome data, this involves assigning persistent unique identifiers and rich, machine-readable metadata. The NMDC recommends using standardized metadata schemas such as the Genomic Standards Consortium MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence) checklist to ensure comprehensive description of samples and processing methods [16]. This structured approach to metadata enables effective searching across repositories and facilitates the integration of datasets from different studies.

Implementation of findability requires depositing data in recognized repositories such as the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) for metagenomic data, which provides stable accession numbers that can be referenced in publications [16]. The findability principle acknowledges that as biological databases have grown to contain petabytes of sequence data, robust indexing and identification systems have become increasingly essential for scientific progress [17].

Accessible

Accessibility ensures that data and metadata can be retrieved using standardized protocols, including authentication and authorization where necessary. For microbiome data, this typically involves deposition in public repositories that provide open access while respecting privacy and ethical considerations [16]. The accessibility principle emphasizes that even if data is restricted for legitimate reasons (such as human subject privacy), the metadata should remain accessible to inform researchers of the dataset's existence and basic characteristics.

The NMDC supports accessibility through its data portal and collaboration with repositories that maintain long-term preservation of microbiome data [15]. Proper implementation of accessibility also includes clear documentation of any access restrictions and the process for requesting special permissions, creating a transparent pathway for legitimate data reuse.

Interoperable

Interoperability refers to the ability of data to integrate with other datasets, applications, and workflows. For microbiome research, this requires using shared vocabularies, ontologies, and standardized formats that enable cross-study analysis and meta-analyses [16]. The field utilizes established community standards including the GSC MIxS for metagenomics, the Proteomics Standards Initiative for metaproteomics, and the Metabolomics Standards Initiative for metabolomics data [16].

Interoperable data is particularly important for microbiome studies due to their interdisciplinary nature, often combining microbial composition data with clinical, environmental, and experimental metadata. The use of controlled terminologies and common data elements ensures that data from different sources can be meaningfully compared and integrated, facilitating larger-scale analyses that yield more robust biological insights [18].

Reusable

Reusability represents the ultimate goal of FAIR principles—ensuring that data can be effectively repurposed for new research questions. This requires rich provenance information, clear usage licenses, and comprehensive documentation of experimental and processing methods [16]. Reusable microbiome data enables the validation of published findings, secondary analysis exploring new hypotheses, and the development of novel computational methods.

The reusability principle is strongly supported by the adoption of standardized reporting guidelines such as the STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist, which provides a comprehensive framework for reporting human microbiome research [12]. Additionally, the emerging concept of Data Reuse Information (DRI) tags helps facilitate appropriate reuse by providing a machine-readable mechanism for data creators to express their preferences regarding contact before reuse [17].

The Microbiome Data Lifecycle

The microbiome data lifecycle encompasses all stages from initial project planning through final data preservation and reuse. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, highlighting how FAIR principles integrate at each phase:

Diagram 1: The Microbiome Data Lifecycle integrated with FAIR principles, showing the progression from project planning through data reuse.

Data Management Planning

The lifecycle begins with comprehensive data management planning, which establishes the foundation for producing FAIR data. A Data Management Plan (DMP) is required by most federal funders and serves as a roadmap for how data will be handled throughout the project [16]. The NMDC provides a microbiome-specific DMPTool template that includes step-by-step prompts for creating effective data management plans, with sections covering:

- Data types and sources describing the kinds of data to be generated and methods used

- Data standards and formats specifying community standards and adherence to FAIR principles

- Roles and responsibilities defining team members' data management tasks

- Data dissemination and archiving outlining release timelines and preservation strategies [16]

Sample Collection and Metadata Standardization

Standardized sample collection is critical for generating comparable microbiome data. The International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS) has developed standardized operating procedures for sample collection from various body sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity, respiratory system, urogenital tract, and skin [3] [19]. The Clinical-Based Human Microbiome Project (cHMP) exemplifies rigorous standardization with protocols for:

- Fecal specimen collection with minimum required quantities (1g solid, 5mL liquid) and condition documentation using the Bristol stool chart

- Respiratory specimen collection from both upper (nasopharyngeal swabs) and lower airways (sputum, BAL)

- Urogenital specimen collection including vaginal swabs and urine samples

- Oral microbiome sampling using non-stimulated saliva or rinse methods [19]

Comprehensive clinical metadata collection is equally essential, including demographic information, medication history (particularly antibiotics), dietary habits, and health history [19]. The STORMS checklist provides detailed guidance on essential metadata elements for human microbiome studies [12].

Wet Lab Processing and Sequencing

Standardized laboratory processing minimizes technical variation and enhances data comparability. Key considerations include:

- DNA extraction methods using validated kits and protocols

- PCR amplification parameters carefully controlled for amplicon sequencing

- Quality control measures including quantification and quality assessment

- Sequencing methodologies either amplicon (16S rRNA) or whole metagenome shotgun sequencing [19]

The field employs quality control materials such as the NIST Human Gut Microbiome Reference Material to assess technical performance and enable cross-laboratory comparability [8]. This reference material represents exhaustively characterized human fecal material that laboratories can use to benchmark their methods.

Bioinformatics Processing and Analysis

Bioinformatic processing transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights. Standardized workflows are essential for reproducibility, with considerations for:

- Quality filtering and read trimming

- Taxonomic profiling using reference databases

- Functional annotation of metabolic potential

- Statistical analysis accounting for compositional nature of microbiome data [18]

The bioinformatics phase heavily relies on interoperability through use of standard file formats (FASTQ, SAM/BAM, BIOM) and common taxonomic nomenclature to enable data integration and tool interoperability.

Data Deposition and Publication

Data deposition in public repositories ensures long-term preservation and access. Microbiome community standards specify appropriate repositories for different data types:

Table 1: Microbiome Data Repository Standards

| Data Type | Community Standard | Primary Repository |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomics | GSC MIxS | Sequence Read Archive (SRA) |

| Metatranscriptomics | GSC MIxS | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) |

| Metaproteomics | Proteomics Standards Initiative | PRIDE |

| Metabolomics | Metabolomics Standards Initiative | Metabolomics Workbench |

Data publication may also include Microbiome Data Reports in journals such as Nature Scientific Data and Microbiology Resource Announcements, which provide detailed descriptions of how data was produced, enhancing its reusability [16].

Data Preservation and Reuse

The final stage of the lifecycle focuses on long-term preservation and enabling downstream reuse. Effective preservation includes:

- Persistent archiving in trusted repositories

- Clear usage licenses specifying terms of reuse

- Data provenance documenting processing history

- Version control for updated datasets [16]

The emerging Data Reuse Information (DRI) tag system provides a machine-readable mechanism for data creators to express preferences regarding contact before reuse, facilitated by association with ORCID accounts [17]. This approach aims to balance open data access with appropriate recognition for data creators.

Implementing FAIR Principles: Practical Protocols

FAIR Implementation Protocol for Microbiome Data

The following workflow provides a step-by-step protocol for implementing FAIR principles throughout a microbiome research project:

Diagram 2: FAIR Implementation Protocol showing sequential steps for applying Findable (F), Accessible (A), Interoperable (I), and Reusable (R) principles.

Metadata Collection Protocol

Comprehensive metadata collection is essential for FAIR microbiome data. The following protocol outlines standardized metadata elements based on STORMS guidelines and cHMP standards:

Table 2: Essential Metadata Categories for Human Microbiome Studies

| Metadata Category | Essential Elements | Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Study type, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sampling framework | STORMS Section 1 |

| Subject Data | Age, sex, BMI, medical history, medication use | STORMS Section 2, cHMP CRF |

| Sample Collection | Body site, collection method, preservation method, time/date | MIxS, IHMS SOPs |

| Wet Lab Methods | DNA extraction kit, PCR primers, sequencing platform | STORMS Section 3 |

| Sequencing Data | Sequencing type, read length, quality metrics | SRA submission standards |

| Bioinformatics | Analysis tools, parameters, database versions | STORMS Section 4 |

Protocol Steps:

- Select appropriate MIxS checklist (human-associated, human-gut, etc.) based on study design

- Implement case report forms for clinical metadata capturing demographics, comorbidities, and medication history

- Record sample collection parameters including time, condition, and preservation method

- Document laboratory processing details including kit lot numbers and equipment used

- Track computational analysis parameters and software versions for reproducibility

- Validate metadata completeness ensuring less than 10% missing data for essential elements [19]

Data Deposition Protocol

Depositing data in public repositories ensures accessibility and long-term preservation:

Pre-deposition Preparation:

- Quality control of sequence data using FastQC or similar tools

- Metadata validation against repository requirements

- File format conversion to standard formats (FASTQ, BAM)

- Sensitive data review for potential human sequence contamination

Repository Submission:

- Select appropriate repository based on data type (Table 1)

- Create submission account with ORCID integration when possible

- Upload data files following repository-specific guidelines

- Complete metadata fields using controlled vocabularies

- Obtain accession numbers for immediate citation in publications

- Apply Data Reuse Information (DRI) tag if desired, specifying ORCID for contact [17]

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing standardized protocols requires specific research reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for FAIR microbiome research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Standardized Microbiome Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/Standards |

|---|---|---|

| NIST Human Gut Microbiome Reference Material | Quality control standard for laboratory processing | RM 140, characterized human fecal material |

| Standard DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation with reproducible performance | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit |

| 16S rRNA Amplification Primers | Target-specific amplification for metabarcoding | 515F-806R (V4 region), 27F-338R (V1-V2 regions) |

| Shotgun Sequencing Library Prep Kits | Library preparation for whole metagenome sequencing | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera XT Library Prep Kit |

| MIxS Checklist Templates | Standardized metadata collection | GSC MIxS human-associated checklist |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Reproducible computational analysis | QIIME 2, mothur, HUMAnN 3, METAXA2 |

| Data Repository Accessions | Persistent data storage and access | SRA, ENA, DDBJ accession numbers |

The integration of FAIR principles throughout the microbiome data lifecycle represents a fundamental requirement for advancing human microbiome research. From initial project planning through final data preservation, each stage offers opportunities to enhance findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. The standardized protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these principles within the context of International Human Microbiome Standards.

As the field continues to evolve with increasing data volumes and analytical complexity, commitment to FAIR data management will be essential for maximizing research investment, enabling cross-study comparisons, and accelerating translational applications. By adopting these standardized approaches, the microbiome research community can enhance scientific reproducibility, foster collaborative discovery, and ultimately advance our understanding of human-microbe interactions in health and disease.

Exploring the 'Hologenome' Concept and Its Research Implications

The hologenome concept of evolution represents a paradigm shift in how we view complex organisms, proposing that a host and its associated microbial communities form a single, cohesive biological entity known as a holobiont. The combined genome of the host and its microbiome constitutes the hologenome, which functions as a unit of selection in evolution [20]. This concept challenges the traditional view of individual organisms by emphasizing that all animals and plants harbor abundant and diverse microbiota, and that this association is not merely incidental but fundamental to their biology and evolution [21].

The conceptual foundation rests on four key principles: (1) All animals and plants are holobionts containing abundant microbiota; (2) The holobiont functions as a distinct biological entity; (3) A significant fraction of the microbiome is transmitted between generations; and (4) Genetic variation in the hologenome occurs through both host genome and microbiome genome changes, with the latter providing rapid adaptation capabilities [20]. This framework has profound implications for human microbiome research, particularly in the context of standardized protocols developed by initiatives such as the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS), which aim to optimize data quality and comparability across studies [3].

Theoretical Framework and Biological Significance

Core Principles of the Hologenome Concept

The hologenome concept redefines our understanding of evolutionary units by considering the holobiont as a level of biological organization upon which natural selection acts. The hologenome comprises two complementary genetic components: the host genome, which is relatively stable and changes slowly through traditional mechanisms, and the microbiome genome, which is dynamic and can respond rapidly to environmental changes [20]. This dynamic nature of the microbiome genome allows for swift adaptation through several mechanisms: shifts in microbial population structures, acquisition of novel microorganisms, horizontal gene transfer between microbial constituents, and microbial mutations [20].

The hologenome functions as an integrated whole across multiple biological domains—anatomically, metabolically, immunologically, and developmentally—forming what can be considered a distinct biological entity [20]. This perspective is supported by observations that holobionts, such as humans with their gut microbiota, exhibit metabolic capabilities that far exceed the genetic capacity of the host alone. The human gut microbiome contains approximately 4 × 10^13 bacteria and an estimated 9 million unique protein-coding genes, outnumbering human genes by a factor of 400:1 [20]. This genetic expansion enables holobionts to adapt to changing environmental conditions more rapidly than would be possible through host genetic adaptation alone.

Medical and Evolutionary Implications

The hologenome concept provides a novel framework for understanding health and disease, suggesting that dysbiosis (disturbances in the microbiome) can contribute to various conditions, including obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and neurological disorders such as autism [21]. From an evolutionary perspective, the concept explains how holobionts can adapt to changing environments rapidly—the flexible microbiome genome provides immediate adaptive capacity while the more stable host genome undergoes slower evolutionary changes [20].

Recent experimental evidence supports the relevance of the hologenome as a biological level of organization. Studies on grafted plants have demonstrated non-random assembly of microbial communities in chimeric plants, with interactive effects between rootstock and scion influencing microbiome composition [22]. This rejects the null hypothesis that holobionts assemble randomly and supports the hologenome as a valid biological concept. Furthermore, research on wild Brassica rapa populations has identified plant genetic bases associated with microbiota composition, revealing "holobiont generalist genes" that regulate microbial communities across different kingdoms [23].

Table 1: Key Evidence Supporting the Hologenome Concept

| Evidence Type | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Abundance | Human gut contains ~4×10^13 bacteria with 9 million unique genes [20] | Expands host genetic capacity and metabolic potential |

| Experimental Studies | Grafted plants show non-random microbiome assembly driven by both rootstock and scion [22] | Demonstrates host genetic influence on microbiome structure |

| Genetic Analysis | Identification of "holobiont generalist genes" in Brassica rapa associated with both bacterial and fungal communities [23] | Reveals shared genetic mechanisms for regulating diverse microbiota |

| Medical Relevance | Microbiome alterations linked to obesity, IBD, autism, and other conditions [21] | Supports holobiont approach to understanding disease |

Standardized Protocols in Hologenome Research

The IHMS Framework for Human Microbiome Studies

The International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS) project emerged in response to the critical need for standardized methodologies in human microbiome research. The project's overarching goal is to promote the development and implementation of standard procedures and protocols across three fundamental activities: (1) collecting and processing of human samples, (2) sequencing of human-associated microbial genes and genomes, and (3) organizing and analyzing the gathered data [2]. This standardization is essential for enabling meaningful comparisons across studies and accelerating progress in understanding the human hologenome.

The IHMS focused specifically on gut microbial communities through quantitative metagenomics, recognizing that stool samples represent the most numerous and abundant microbial communities in the human body, can be obtained non-invasively, and were the prime target of several large international studies [2]. The development of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) addressed the critical issue of conservation of microbial composition during sample collection, processing, and analysis. These protocols have been publicly accessible through the IHMS website to promote widespread adoption [3].

Sample Collection and Preservation Protocols

The IHMS developed four distinct SOPs for sample collection, addressing the crucial issue of maintaining microbial composition integrity between sample emission and processing. These protocols were designed for various real-world scenarios researchers might encounter:

- SOP 1: For samples transferable to the laboratory within 4 hours of collection. This protocol permits transfer at room temperature, simplifying the process.

- SOP 2: For samples requiring 4-24 hours for transfer to the laboratory. This protocol requires establishing anaerobic conditions using commercial substances (e.g., Anaerocult) during sample conservation, with room temperature transfer.

- SOP 3: For samples with transfer times between 24 hours and 7 days. This protocol requires immediate freezing at -20°C upon collection, with shipment to the laboratory on dry ice without thawing.

- SOP 4: Utilizes a stabilization solution that preserves microbial composition at room temperature, enabling shipment via courier mail [2].

These protocols were validated through comparative assessment using quantitative metagenomics, confirming that all four methods conserve stool microbial communities in a comparable manner. For long-term conservation (biobanking), storage at -80°C is required for all protocols, with recommendations to store several separate frozen aliquots to avoid alterations from thawing and refreezing [2].

DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Data Analysis Standards

Beyond sample collection, the IHMS developed two SOPs for sample processing (DNA extraction): one optimized for manual work in smaller-scale studies, and another designed for automation in large-scale research institutions [2]. For sequencing, three SOPs were established outlining quality control of DNA to be sequenced, the sequencing procedure itself, and quality control of the output sequencing reads. Finally, two SOPs were recommended for assessing microbial community composition based on sequencing data—one for taxonomic composition and another for functional composition [2].

Complementing the IHMS framework, the STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides comprehensive reporting guidelines for human microbiome research [12]. This 17-item checklist spans six sections corresponding to typical scientific publication sections and addresses the unique methodological considerations of microbiome studies, including handling of high-dimensional data, statistical analysis of compositional relative abundance data, and batch effect management.

IHMS Standardized Workflow for Hologenome Research

Experimental Approaches and Research Applications

Study Designs for Hologenome Analysis

Research into hologenome dynamics employs diverse experimental approaches, each with specific applications and methodological considerations. Genome-Environment Association (GEA) studies represent a powerful method for identifying host genetic factors associated with microbiome composition in natural populations. This approach has successfully identified "holobiont generalist genes" in wild Brassica rapa populations that correlate with both fungal and bacterial community structures [23]. GEA captures natural evolutionary processes in holobionts by examining associations between host genetic polymorphisms and environmental variables, including microbiome descriptors.

Reciprocal grafting experiments in plants provide another robust experimental design for testing hologenome principles. Studies on watermelon and grapevine systems, including ungrafted and reciprocal-grafting combinations, have demonstrated that grafted hosts harbor markedly different microbiota compositions compared to ungrafted controls, with interactive effects between rootstock and scion driving non-random assembly of microbial communities [22]. This experimental approach allows researchers to disentangle the contributions of host genetics and microbial recruitment to holobiont function.

Longitudinal human studies tracking microbiome changes in response to dietary interventions, medications, or disease progression provide critical insights into hologenome dynamics. Recent research presented at the 2025 Gut Microbiota for Health Summit highlighted clinical applications, including the use of low-emulsifier diets for Crohn's disease management and the role of navy bean supplementation in modulating the gut microbiome of patients with obesity and history of colorectal cancer [24].

Analytical Methods and Bioinformatics Pipelines

The analysis of hologenome data requires specialized bioinformatics approaches to handle the complexity and high-dimensional nature of microbiome datasets. The IHMS recommends two SOPs for assessing microbial community composition from sequencing data: one for taxonomic composition and another for functional composition [2]. These protocols address critical analytical challenges, including:

- Taxonomic profiling from metagenomic sequencing data

- Functional annotation of microbial genes

- Metagenomic assembly and binning to reconstruct genomes

- Cross-study comparability through standardized pipelines

Complementing these analytical frameworks, the STORMS checklist provides comprehensive guidance for reporting bioinformatics and statistical analyses tailored to microbiome studies [12]. This includes recommendations for handling sparse, compositionally complex data and addressing batch effects that are particularly problematic in microbiome research.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches in Hologenome Research

| Approach | Key Features | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Environment Association (GEA) | Correlates host genetic variation with microbiome descriptors in natural populations [23] | Identifying host genetic loci associated with microbiome assembly; Studying holobiont adaptation in wild populations | Requires extensive sampling across natural gradients; Confounding by environmental covariates |

| Reciprocal Grafting | Creates chimeric organisms with different genetic combinations of rootstock and scion [22] | Testing host genetic control of microbiome assembly; Disentangling root vs. shoot influences on microbiota | Primarily applicable to plants; Technical challenges with grafting success |

| Longitudinal Interventions | Tracks hologenome changes over time in response to controlled perturbations [24] | Clinical translation of microbiome research; Understanding temporal dynamics of holobionts | Participant compliance; Multiple confounding factors in human studies |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling taxonomic and functional profiling [2] | Comprehensive characterization of microbiome composition and functional potential; Strain-level analysis | Computational intensity; Challenges with low-biomass samples |

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

Essential Materials for Hologenome Studies

Conducting rigorous hologenome research requires specific reagents and materials that maintain microbiome integrity throughout sample collection, processing, and analysis. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing standardized protocols in hologenome research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hologenome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerocult | Creates anaerobic conditions for sample preservation | Critical for samples requiring 4-24 hours transfer to lab; Prevents oxygen-sensitive microbe mortality [2] |

| Stabilization Solutions | Preserves microbial composition at room temperature | Enables extended shipment times without freezing; Maintains DNA integrity for accurate sequencing [2] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples | Choice of manual vs. automated protocols depends on scale; Critical for minimizing biases in community representation [2] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | Prepares libraries for shotgun metagenomic sequencing | Enables quantitative metagenomics; Superior resolution to 16S rRNA sequencing for functional profiling [2] |

| Quality Control Standards | Assesses DNA quality before sequencing | Includes fluorometric quantification, fragment analysis; Essential for generating high-quality sequence data [2] |

| Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) | Defined microbial mixtures for experimental validation | Used to test host-microbe interactions; Enables reductionist approaches to complement ecological studies [23] |

Methodological Considerations for Specific Applications

Different research questions within hologenome studies require tailored methodological approaches. For human nutritional studies, comprehensive dietary assessment tools must capture not only macronutrients but also "dietary dark matter" including phytochemicals, food ingredients (emulsifiers, colors), cooking methods, and packaging—all of which represent potential confounders in microbiome-health relationships [24]. For intervention studies, the choice of prebiotic fibers requires careful consideration, as not all fibers impact the gut microbiome and host similarly, with differential effects observed between fiber-rich foods and supplemental fibers [24].

In transplantation models, both fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in animal models and rationally designed probiotics (e.g., SER-155, an investigational cultivated microbiome therapeutic) in human clinical trials represent powerful approaches for manipulating the hologenome to study causal relationships [24]. These interventions require strict quality control of microbial preparations and standardized administration protocols to ensure reproducible results.

Genetic Variation and Adaptation in the Hologenome

The hologenome concept represents a transformative framework for understanding host-microbe interactions as integrated biological systems rather than as independent entities. By viewing hosts and their microbiomes as holobionts with collective hologenomes, researchers can explore new dimensions of adaptation, evolution, and disease etiology. The development of standardized protocols through initiatives like the International Human Microbiome Standards provides the methodological foundation necessary for robust, reproducible hologenome research [3] [2].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: (1) Elucidating the mechanisms of microbiome transmission between generations and the factors that maintain stability of core microbial communities; (2) Understanding the interplay between host genetics and microbiome assembly through genome-environment association studies; (3) Developing targeted interventions that manipulate the hologenome for clinical benefit, such as phage therapy for multidrug-resistant pathogens [24] or dietary modifications for Crohn's disease management [24]; and (4) Integrating knowledge across biological scales from molecular interactions to ecosystem-level dynamics.

As the field advances, the continued refinement and adoption of standardized protocols will be essential for translating hologenome concepts into practical applications in medicine, agriculture, and environmental science. The hologenome perspective not only expands our understanding of biological organization but also opens new avenues for manipulating these complex systems to improve human health and environmental sustainability.

Implementing Best-Practice Protocols: From Sample to Sequence

The integration of standardized clinical metadata collection is fundamental to advancing human microbiome research, particularly within the framework of the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS). The particularly interdisciplinary nature of human microbiome research makes the organization and reporting of results spanning epidemiology, biology, bioinformatics, translational medicine, and statistics a significant challenge [12]. Variations in sample collection, processing, and data documentation can profoundly impact the reproducibility and comparability of findings across studies. Standardized protocols ensure that data generated are both reliable and comparable, enhancing data integrity and accelerating research progress with potential applications for improving human health outcomes [19] [3]. This document outlines essential variables and Case Report Form (CRF) design principles to support the collection of high-quality, interoperable clinical metadata for microbiome studies, aligning with IHMS objectives and broader regulatory standards for clinical research.

Essential Clinical Metadata Variables for Microbiome Studies

Accurate microbiome data collection necessitates corresponding clinical metadata, which is essential for interpreting metagenome and multi-omics data in clinical settings [19]. The following variables represent the core set of data required to contextualize microbiome findings, drawn from standardized protocols such as those used in the Clinical-Based Human Microbiome Research and Development Project (cHMP) [19]. These variables should be collected for all participants, with additions for specific disease groups.

Table 1: Core Demographic and Clinical History Variables

| Category | Specific Variables | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Date of birth, gender, height, weight, blood pressure, pulse, body temperature [19] | Required for all participant groups. |

| Lifestyle & History | Smoking history, alcohol consumption history, pet ownership (last 2 years), highest education level, hospitalization/ICU admission (last 6 months), surgical history [19] | Essential for identifying environmental exposures and recent healthcare interactions. |

| Medication Use | History of antibiotic, systemic steroid, immunosuppressant, probiotic, and acid suppressant use within the last 6 months, including start and end dates [19] | Critical, as medications significantly alter microbiome composition. |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, atopy, allergic rhinitis, asthma, food/drug allergy, and other chronic conditions [19] | Collect for all participants to control for confounding conditions. |

Table 2: Site-Specific and Dietary Variables

| Body Site | Essential Variables | Additional Site-Specific Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal Tract | Bowel habits, average daily bowel movements, frequency of exercise [19] | Breakfast consumption, frequency of meals, Western/Mediterranean/gluten-free dietary habits, daily dairy product consumption, frequent kimchi consumption [19]. |

| Genitourinary Tract | History of urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted infections (last 2 years), use of sex hormone preparations [19] | Females: Pregnancy history, menopausal status, last menstrual period, vaginal cleansing practices.Males: Chronic prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, history of circumcision [19]. |

| Oral Cavity | Daily brushing frequency, use of interdental brushes, dental floss, mouthwash [19] | Dental treatment within last 3 months, scaling treatment, conditions of oral soft tissues, number of teeth, presence/severity of periodontal disease [19]. |

| Respiratory Tract | Allergic history [19] | Endoscopic findings, FEV1, FVC, FEF25%–75% (for lower respiratory) [19]. |

Standardized CRF Design and Development

Fundamental Principles of CRF Design

A Case Report Form (CRF) is a document designed to record all patient information that needs to be collected during a clinical trial or research study [25]. For a study to be successful, the data collected must be correct and complete, which requires that forms be well planned with meticulous attention to detail, comply with the study protocol, and adhere to regulatory requirements [25].

Objectives of Effective CRF Design:

- Gather Complete, Accurate, High-Quality Data: The form must be structured to minimize errors and ambiguities [25].

- Avoid Duplication: Each data point should be collected only once to streamline the process and prevent inconsistencies [25].

- Ensure User-Friendliness: A well-structured, simple, and uncluttered form improves compliance and data quality [25].

- Facilitate Data Processing: Design should enable efficient mapping of data points to submission datasets, such as those defined by the Study Data Tabulation Model (SDTM) [25].

Best Practices and Workflow for CRF Design

The design process requires careful planning and collaboration. The key steps to developing CRFs, as outlined by the Clinical Data Acquisition Standards Harmonization (CDASH) standard, involve determining protocol data collection requirements, reviewing standard domains in CDASH, and developing the data collection tools using these published standards [26].

Figure 1: The CRF design and development workflow, from initial protocol review to final deployment.

Design Dos and Don'ts:

| Dos | Don'ts |

|---|---|

| Use consistent formats, fonts, and headers across all forms [25]. | Allow open-ended questions or excessive free-text responses [25]. |

| Specify units of measurement clearly (e.g., "Height (cm)") [25]. | Gather more data than what is needed by the protocol [25]. |

| Use coded lists and controlled terminology to limit answers to approved responses [25]. | Design forms without clear guidance or prompts for the investigator [25]. |

| Keep related questions together in logical sections [25]. | Use ambiguous questions that are open to interpretation [25]. |

| Provide form completion guidelines with specific instructions [25]. | Rely on "check all that apply" questions which can lead to inconsistent data [25]. |

The Role of Annotated CRFs (aCRFs) in Regulatory Compliance

Annotated CRFs (aCRFs) are a key submission deliverable and a mandatory requirement of regulatory agencies like the FDA [25] [27]. An aCRF is a version of the CRF that contains markings or annotations which map each data point on the form to the name of datasets, and variables within those datasets [25]. In other words, "each CRF should provide the variable names and coding for each CRF item included in the data tabulation datasets" [25].

Purpose and Benefits of aCRFs:

- Regulatory Compliance: They fulfill FDA and EMA requirements, providing a clear audit trail and supporting CDISC compliance [27].

- Data Traceability: Reviewers can easily trace how data flows from the collection point (CRF) to the submission datasets (SDTM), which is crucial for audits and reviews [25] [27].

- Operational Efficiency: Embedding annotations directly in the form creates a single source of truth, reduces manual mapping errors, and streamlines the study build process [27].

Table 3: Examples of CRF Annotations in an SDTM Context

| CRF Field Label | Annotation (Domain & Variable) | Controlled Terminology |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Identifier | DM.SUBJID | NOT SUBMITTED |

| Sex | DM.SEX | "M", "F" |

| Date of Birth | DM.BRTHDTC | ISO 8601 format |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | VS.VSORRES (VS.VSTESTCD = "HR") | Units: "beats/min" |

| Adverse Event Severity | AE.AESEV | "MILD", "MODERATE", "SEVERE" |

Experimental Protocols for Microbiome Sample Handling and Metadata Linkage

Sample Collection and Storage Protocol

Standardized procedures for specimen handling ensure consistent data quality and are a cornerstone of IHMS [19] [3].

Materials:

- Sample Collection Kits: Pre-assembled kits containing all necessary materials for specific sample types (e.g., sterile swabs, cryovials, stabilization buffers).

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coats, and face masks to prevent contamination.

- Temperature-Controlled Storage: Ultra-low temperature freezers (-80°C) or liquid nitrogen tanks for long-term preservation.

- Barcode Labeling System: Pre-printed, unique 2D barcode labels for unambiguous sample tracking.

Methodology:

- Patient Preparation: Instruct participants according to site-specific guidelines (e.g., refrain from oral intake for gut samples, avoid washing for skin samples) [19].

- Sample Acquisition:

- Feces: Collect a minimum of 1 g of solid stool or 5 mL of liquid stool. Record the condition according to the Bristol stool chart [19].

- Saliva (Oral): Collect by non-stimulated methods or through rinsing [19].

- Vaginal Swabs (Urogenital): Collect using standardized swabbing techniques [19].

- Skin: Primarily rely on swabbing and taping, with instructions to refrain from washing the area prior to collection [19].

- Immediate Processing/Aliquoting: Process samples according to SOPs immediately upon receipt in the lab to prevent biomolecule degradation.

- Storage: Snap-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen or a dedicated -80°C freezer. Maintain a continuous cold chain.

- Data Entry: Log the sample into the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) using its barcode, linking it to the participant's unique code and corresponding clinical metadata from the CRF.

DNA Extraction and Sequencing Protocol

Sequencing encompasses both amplicon and whole metagenome methods, followed by stringent quality checks [19].

Materials:

- DNA Extraction Kits: Commercially available kits optimized for the specific sample type (e.g., soil, stool, saliva) to ensure efficient lysis of diverse microbial communities.

- Quantitation Instruments: Fluorometric assays (e.g., Qubit) for accurate DNA concentration measurement.

- Library Preparation Kits: Kits compatible with the chosen sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina, PacBio).

- Sequencing Platforms: High-throughput sequencers (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel).

- Positive Control Reagents: Mock microbial communities with known composition to monitor extraction and sequencing performance.

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from all samples in a single batch using the same lot of extraction kits to minimize technical variation. Include both positive and negative controls.

- Quality Control (QC):

- Assess DNA concentration and purity using fluorometry and spectrophotometry.

- Check DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis systems.

- Library Preparation:

- For 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing (Amplicon): Amplify the hypervariable region (e.g., V4) using barcoded primers. Purify and normalize the resulting amplicons [19].

- For Whole Metagenome Sequencing (WGS): Fragment DNA, repair ends, and ligate with platform-specific adapters. Perform size selection and PCR amplification if required [19].

- Sequencing: Pool libraries in equimolar ratios and sequence on an appropriate platform to achieve sufficient depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per sample for 16S, 10-20 Gb per sample for WGS).

- Data Generation and Transfer: Demultiplex sequences based on barcodes. Transfer raw FASTQ files and QC reports to a secure, designated storage space for bioinformatic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Standardized Microbiome Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Standards |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Stabilization Buffers | Preserves nucleic acid integrity from moment of collection, especially critical during transport. | RNAlater, DNA/RNA Shield |

| Mock Microbial Community Standards | Serves as a positive control for DNA extraction and sequencing to monitor bias and technical variation. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from complex biological samples. | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Targets conserved regions for amplicon sequencing to profile bacterial composition. | 515F/806R (V4 region), 27F/338R (V1-V2) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepares DNA fragments for high-throughput sequencing on specific platforms. | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep Kit |

| Controlled Terminology (CDISC) | Standardizes the values collected in CRF fields, ensuring data consistency. | CDISC CT for sex (M, F), severity (MILD, MODERATE, SEVERE) [27] |

| CDASH Standard CRF Modules | Provides pre-defined, standardized fields for collecting common clinical data. | CDASH domains for Demographics (DM), Adverse Events (AE), Medical History (MH) [26] |

The adoption of standardized protocols for clinical metadata collection and CRF design is non-negotiable for generating robust, reproducible, and comparable data in human microbiome research. By implementing the essential variables outlined herein and adhering to principles of good CRF design and annotation, researchers can ensure data quality from the point of collection through to regulatory submission. These practices, framed within the context of IHMS and aligned with standards like CDASH and SDTM, form the foundation for reliable scientific discovery and the ultimate translation of microbiome research into improved human health outcomes.

The human microbiome, comprising all microbes inhabiting various organs and their associated ecosystems, plays a critical role in human health and disease [19]. Advancements in high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics have made microbiome research more feasible, revealing significant links between microbiomes and various health conditions [19]. However, the field faces a substantial challenge: a lack of standardized methods can lead to inconsistencies that affect the reproducibility and comparative analysis of studies [12]. International initiatives like the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) and the European MetaHIT project have sought to standardize microbiome research methods [19] [28]. The Clinical-Based Human Microbiome Research and Development Project (cHMP) in the Republic of Korea exemplifies a national-level effort to develop standardized protocols for clinical metadata collection, specimen handling, DNA extraction, sequencing, and quality control [19]. This document outlines these body site-specific sampling protocols, framed within the broader context of standardized human microbiome studies, to ensure consistent data quality and reliability for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Essential Metadata and Clinical Data Collection

Accurate microbiome data interpretation is critically dependent on comprehensive clinical metadata, which provides essential context for metagenome and multiomics data [19]. The STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides a framework for reporting such metadata, emphasizing the need to detail study design, participant characteristics, and confounding factors [12]. The cHMP protocol mandates collecting essential patient information, including details on antibiotic and non-antibiotic medication use within the last 6 months, dietary habits, and comprehensive health history [19]. Clinical data should be collected via case report forms and anonymized using unique participant codes, with a target of less than 10% missing clinical data [19]. Participants are typically categorized into disease, healthy, and disease control groups, with the disease control group comprising individuals without the disease under study [19].

Table 1: Core Clinical Metadata Categories for Microbiome Studies

| Category | Details | Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | Age, gender, BMI, blood pressure, smoking history, alcohol consumption, education level, hospitalization/surgical history (last 6 months) | Required for all groups [19] |

| Underlying Diseases & Comorbidities | Hypertension, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, atopy, psychiatric diagnoses, etc. | Required for all groups [19] |

| Medication History | Antibiotics, systemic steroids, immunosuppressants, probiotics, acid suppressants (start/end dates and ingredients) | Required for all groups [19] |

| Blood Test Results | White blood cell count, hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, liver enzymes, creatinine, glucose, albumin | Required for disease and control groups; optional for oral/skin studies [19] |

| Body Site-Specific Lifestyle & History | Varies by site (e.g., bowel habits/diet for gut; menstrual/sexual history for urogenital) | Required as applicable to the specimen type [19] |

Comprehensive Sampling Protocols by Body Site

Microbial communities are distributed throughout the human body, with the gastrointestinal tract being the most densely populated (29%), followed by the oral cavity (26%), skin (21%), respiratory tract (14%), and urogenital tract (9%) [28]. The following sections provide detailed, site-specific sampling protocols.

Gastrointestinal Tract Sampling

For gut microbiota analysis, fecal samples are the most common and non-invasive specimen type [19]. Colonic biopsies, while informative, are invasive and challenging to obtain from healthy individuals as they require colonoscopy [19]. Rectal swabs can be used selectively but carry a high risk of human DNA contamination [19].

Detailed Fecal Sample Protocol:

- Collection: Collect stool using a standardized collection kit. The condition of the stool specimen should be recorded according to the Bristol Stool Chart to standardize descriptions.

- Volume: A minimum of 1 gram of solid stool or 5 mL of liquid stool is required to ensure sufficient material for DNA extraction and analysis [19].

- Storage & Transportation: Immediately after collection, store the sample at -80°C. If a -80°C freezer is not immediately available, temporarily store the sample at -20°C or in a dedicated cryogenic storage box with dry ice for transport to prevent microbial community shifts [19].

Innovative Technology: Recent advancements include passive ingestible sampling devices like the CORAL (Cellularly Organized Repeating Lattice) capsule. This device features a bioinspired triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) lattice microstructure that traps bacteria from the upper gut and small intestine, providing a more accurate representation of these regional microbiomes compared to stool samples [29].

Essential Gastrointestinal Metadata: When collecting gastrointestinal specimens, information regarding bowel habits, daily activities, and detailed dietary habits is mandatory. This includes breakfast consumption, frequency of meals, dietary patterns (e.g., Western, Mediterranean, gluten-free), daily consumption of dairy, fruits, vegetables, and kimchi, as well as specific dietary preferences (e.g., vegan, pescatarian, ketogenic) [19].

Oral Cavity Sampling

The oral cavity hosts a complex microbial ecosystem. Saliva is the preferred specimen for a broad overview of the oral microbiome, while subgingival plaque is targeted for periodontal health studies [19].

Detailed Saliva and Plaque Protocol:

- Saliva Collection (Non-stimulated): Collect saliva by having the participant drool into a sterile collection tube. Alternatively, a rinsing method can be used where the participant swishes and gargles with a sterile saline solution and then expectorates into a tube [19].

- Subgingival Plaque Collection (Curette-based):

- Isolate the tooth surface with cotton rolls and dry gently with air.

- Gently insert a sterile curette into the periodontal sulcus or pocket.

- Apply light lateral pressure to the tooth surface and withdraw the curette.

- Wipe the collected plaque into a sterile microfuge tube containing a preservation buffer.

- Storage: Process and freeze samples at -80°C within a few hours of collection.

Essential Oral Metadata: For oral studies, metadata should include oral hygiene practices such as daily tongue cleaning, use of interdental brushes, dental floss, mouthwash, and oral irrigators. Dental treatment history within the last 3 months, conditions of oral soft tissues, number of teeth, number of untreated dental caries, and the presence/severity of periodontal disease (evaluated using indices like the Community Periodontal Index) are also critical [19].

Respiratory Tract Sampling

Respiratory specimens are collected from both the upper and lower airways. The microbial density is typically higher in the upper respiratory tract than in the lower respiratory tract [28].