Solving the Reproducibility Crisis in Materials Science: A Strategic Guide for Researchers and R&D Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for addressing the pervasive challenge of reproducibility in materials science and related R&D sectors.

Solving the Reproducibility Crisis in Materials Science: A Strategic Guide for Researchers and R&D Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for addressing the pervasive challenge of reproducibility in materials science and related R&D sectors. It begins by defining the core principles of reproducibility and replicability, exploring the root causes of the current 'crisis,' and underscoring its critical importance for scientific trust and drug development. The piece then transitions to practical, actionable strategies, detailing best practices for experimental design, data management, and computational workflows. It further offers troubleshooting guidance for common pitfalls and examines the growing role of large-scale benchmarking platforms and validation studies in assessing methodological performance. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes the latest insights and tools to foster a culture of rigor, transparency, and reliability in research.

Defining the Crisis: Why Reproducibility is the Cornerstone of Reliable Materials Science

In materials science and drug development, the terms "reproducibility," "replicability," and "robustness" are frequently used, but often inconsistently across different scientific disciplines. This terminology confusion creates significant obstacles for researchers trying to build upon existing work or verify experimental claims [1]. Consistent use of these terms is fundamental to addressing broader challenges in research reproducibility, as it enables clear communication about what exactly has been demonstrated in a study and how confirmatory evidence was obtained [2].

This guide provides clear definitions, methodologies, and troubleshooting advice to help you implement these principles in your daily research practice.

Core Definitions and Distinctions

Standardized Definitions

Different scientific disciplines have historically used these key terms in inconsistent and sometimes contradictory ways [1]. The following table presents emerging consensus definitions that are critical for cross-disciplinary communication.

| Term | Definition | Key Question Answered |

|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | "Using the same analysis on the same data to see if the original finding recurs" [3] [2]. Also called "repeatability" in some contexts [2]. | Can I get the same results from the same data and code? |

| Replicability | "Testing the same question with new data to see if the original finding recurs" [2]. Also described as "doing the same study again" to see if the outcome recurs [3]. | Does the same finding hold when I collect new data? |

| Robustness | "Using different analyses on the same data to test whether the original finding is sensitive to different choices in analysis strategy" [2]. | Is the finding dependent on a specific analytical method? |

Relationship Between Concepts

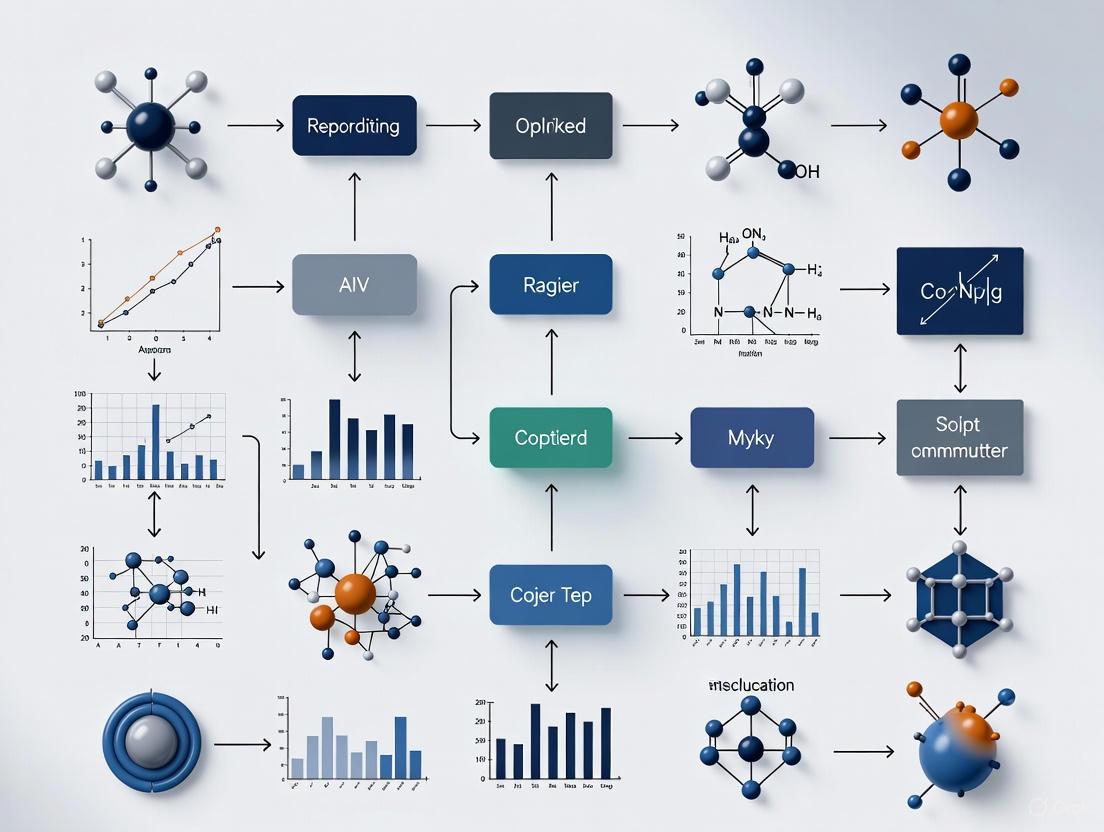

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between these concepts in the scientific validation process.

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Computational Reproducibility

This protocol is essential for verifying computational analyses in materials informatics or simulation-based studies.

Objective: To verify that the same computational analysis, when applied to the same data, produces identical results [1] [3].

Materials & Setup:

- Primary Data: The original dataset used in the study.

- Computational Code: The complete analysis pipeline (e.g., Python/R scripts).

- Environment: A computational environment matching the original specifications (e.g., Docker container, Conda environment).

Procedure:

- Acquire Artifacts: Obtain the original dataset and computational code from a trusted repository.

- Recreate Environment: Precisely recreate the software, library versions, and system configuration used in the original study [4].

- Execute Analysis: Run the complete analysis pipeline from raw data to final results.

- Compare Outputs: Systematically compare the generated results (figures, numerical outputs, trained models) to those reported in the original publication.

Troubleshooting: Common failure points include missing dependencies, undocumented data pre-processing steps, and version conflicts in software libraries [4].

Protocol 2: Assessing Empirical Replicability

This protocol is used for experimental laboratory studies, such as synthes a new material or testing a drug compound.

Objective: To determine whether the same experimental finding can be observed when the study is repeated with new data collected under similar conditions [5] [2].

Materials & Setup:

- Protocol: The detailed experimental method from the original study.

- New Samples/Materials: Independantly sourced or prepared reagents, chemicals, or material samples.

- Instrumentation: Equivalent laboratory equipment.

Procedure:

- Design Replication Study: Based on the original methods section, design a new experiment that tests the same fundamental hypothesis.

- Prepare New Materials: Source or synthesize new samples without assistance from the original research team.

- Execute Independent Experiment: Conduct the experiment and collect a new dataset, carefully documenting any minor deviations from the protocol.

- Analyze and Compare: Analyze the new data and compare the central findings (e.g., effect size, statistical significance, material properties) to those of the original study.

Troubleshooting: Replication is inherently probabilistic and never exact. Focus on whether the same underlying finding is observed, not on obtaining identical numerical results [3].

Protocol 3: Assessing Analytical Robustness

This protocol tests the sensitivity of research findings to different analytical choices, common in data-intensive materials science.

Objective: To determine if the primary conclusions of a study change under different reasonable analytical methods [2].

Materials & Setup:

- Original Dataset: The same data used in the original study.

- Alternative Methods: Different statistical models, data processing techniques, or computational parameters.

Procedure:

- Identify Decision Points: Map the key analytical choices made in the original study (e.g., outlier handling, normalization technique, model hyperparameters).

- Apply Variants: For each key decision point, re-analyze the data using one or more justifiable alternative methods.

- Compare Inferences: Determine whether the scientific conclusion remains consistent across the different analytical variants.

Troubleshooting: A finding that is not robust to minor analytical changes may indicate a weak or unreliable effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and practices that facilitate reproducible, replicable, and robust research.

| Item | Function in Research | Role in Supporting R&R |

|---|---|---|

| FAIR Data Platforms (e.g., Materials Commons [6]) | Repositories for sharing research data and metadata. | Makes data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, enabling replication and reproduction. |

| Computational Workflow Tools (e.g., Jupyter, Nextflow) | Environments for creating and sharing data analysis pipelines. | Encapsulates the entire analysis from raw data to result, ensuring computational reproducibility [1]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | Digital systems for recording experimental protocols and observations. | Ensures detailed, searchable records of methods and materials, crucial for replication attempts. |

| Version Control Systems (e.g., Git) | Systems for tracking changes in code and documentation. | Maintains a complete history of computational methods, allowing anyone to recreate the exact analysis state [4]. |

| Metadata Capture Services (e.g., beamline metadata systems [6]) | Automated systems that record critical experimental parameters. | Captures contextual details (e.g., sample history, instrument settings) that are often omitted but are vital for replication. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: We failed to reproduce a key computational result from a paper. What should we do next?

First, meticulously document your reproduction attempt, including your environment setup and all steps taken. Contact the corresponding author of the paper to politely inquire about potential missing details in the method description or undocumented dependencies in the code [4]. Remember that a failure to reproduce is not necessarily an accusation but can be a valuable step in identifying subtle complexities in the analysis.

Q2: Is there a "reproducibility crisis" in science?

Some experts frame it as a "crisis," while others view it more positively as a period of active self-correction and quality improvement within the scientific community [2]. Widespread efforts to improve transparency and rigor, such as the Materials Genome Initiative and the FAIR data movement, are direct responses to these challenges and are helping to drive progress [6].

Q3: Our replication attempt produced a similar effect but with a smaller effect size. Is this a successful replication?

This is a common scenario. A successful replication does not always mean obtaining an identical numerical result. If your new study confirms the presence and direction of the original effect, it often supports the original finding. The difference in effect size could be due to random variability, subtle differences in experimental conditions, or other unknown factors. This outcome should be reported transparently, as it contributes to a more precise understanding of the phenomenon [5].

Q4: What is the single most important thing we can do to improve reproducibility of our own work?

Embrace full transparency by sharing your raw data, detailed experimental protocols, and computational code whenever possible [2]. As one expert notes, "Transparency is important because science is a show-me enterprise, not a trust-me enterprise" [2]. This practice allows others to reproduce your work, builds confidence in your findings, and enables the community to build more effectively upon your research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Irreproducibility Issues

FAQ: What are the most common causes of irreproducible results in materials science experiments? Irreproducibility often stems from incomplete documentation of methods, inconsistent sample preparation, poor data management practices, and a lack of standardized protocols across research teams. Adopting detailed, standardized reporting is critical for compliance and building trust in results [7].

FAQ: How can I make my research data more reproducible? Implement the FAIR data principles, making your data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [6]. Use standardized data formats and digital tools for documenting experiments. Reproducible research is well-documented and openly shared, making it easier for teams to build on previous work [7].

FAQ: Are there tools to help improve reproducibility before I start an experiment? Yes, simulation tools like MechVDE (Mechanical Virtual Diffraction Experiment) allow you to run simulated experiments in a virtual beamline environment. This helps plan and refine your actual experiment, uncovering insights that typically require trial and error at the beamline [6].

Quantitative Impact of Irreproducibility

The table below summarizes the financial and temporal costs associated with common reproducibility failures.

| Failure Point | Estimated Resource Waste | Common Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Metadata | Up to 20% of project time spent recreating lost sample context [6] | Lack of integrated metadata systems; manual lab notebook entries |

| Non-Standard Protocols | 15-30% delay in project timelines due to collaboration friction [7] | Inconsistent methods between teams and locations |

| Poor Data Management | Significant duplication of effort in data reprocessing and validation [6] | Data siloed and not FAIR-compliant |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Reproducible Materials Research

The following workflow, developed through a collaboration between the University of Michigan and the CHESS FAST beamline, provides a reproducible methodology for studying deformation mechanisms in magnesium-yttrium alloys [6].

1. Pre-Experiment Simulation with MechVDE

- Function: Use the MechVDE tool to run a simulated diffraction experiment.

- Methodology: Place a virtual sample into a simulated beamline, collect synthetic detector data, and use it to plan the actual experiment. This is crucial for detecting subtle signals like deformation twinning [6].

2. Sample Preparation and Characterization

- Material System: Magnesium-Yttrium (Mg-Y) alloys.

- Objective: Improve formability for lightweight automotive structures.

- Critical Metadata to Capture: Sample composition, processing history, and heat treatment. This information must be automatically logged in a centralized database, permanently linked to the beamline dataset [6].

3. In-Situ Experimentation and Real-Time Monitoring

- Setup: Conduct the experiment at the FAST beamline or a similar facility.

- Real-Time Monitoring: Use cyberinfrastructure like NSDF (National Science Data Fabric) dashboards to view experimental data in near real-time through a web browser, enabling remote collaborators to analyze plots simultaneously and make real-time decisions [6].

4. FAIR Data Curation and Sharing

- Curation Process: Connect the beamline's metadata system with external repositories like Materials Commons.

- Outcome: Datasets are easily interpreted, reused, and cited by the broader community, turning a single result into a tool for others [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool or Material | Function in Reproducible Research |

|---|---|

| Digital Lab Notebooks | Tools for automatic experiment documentation, standardizing metadata, and managing version control to ensure traceability [7]. |

| protocols.io | Platform for sharing and adapting experimental methods across teams and disciplines, making methods clear and accessible [7]. |

| Standardized Data Formats | Ensure consistency and interoperability across global teams and external partners, simplifying review processes [7]. |

| Centralized Metadata Service | Integrated beamline infrastructure that captures critical sample details and links them permanently to the dataset [6]. |

| TIER2 Reproducibility Training | Free, accessible courses on the OpenPlato platform to build capacity in reproducible research practices [8]. |

The reproducibility crisis represents a fundamental challenge in scientific research, where many published studies are difficult or impossible to replicate, undermining the self-correcting principle of the scientific method. A 2016 survey in Nature revealed that 70% of researchers were unable to reproduce another scientist's experiments, and more than half could not reproduce their own findings [9]. In preclinical drug development, this manifests dramatically with a 90% failure rate for drugs progressing from Phase 1 trials to final approval, partly due to irreproducible preclinical research [10]. The financial impact is staggering, with an estimated $28 billion per year spent on non-reproducible preclinical research [11].

Defining Reproducibility

The American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) has established a multi-tiered framework for understanding reproducibility [11]:

- Direct Replication: Reproducing a result using the same experimental design and conditions as the original study.

- Analytic Replication: Reproducing findings through reanalysis of the original dataset.

- Systemic Replication: Reproducing a published finding under different experimental conditions.

- Conceptual Replication: Evaluating a phenomenon's validity using different experimental methods.

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Reproducibility Failures

Common Symptoms and Error Indicators

| Symptom Category | Specific Indicators | Common Research Contexts |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Materials Issues | - Cell line misidentification- Mycoplasma contamination- Genetic drift from serial passaging- Unauthenticated reagents | Preclinical studies, in vitro assays, cell biology research [11] |

| Data & Analysis Issues | - Large variation between replicates- Inaccessible raw data/code- Selective reporting of results- p-values hovering near 0.05 | All fields, particularly those relying on complex statistical analysis [9] [12] |

| Methodological Issues | - Inability to match published protocols- Insfficient methodological detail- Equipment sensitivity variations | Materials science, chemistry, experimental psychology [6] [13] |

| Experimental Design Issues | - Small sample sizes- Lack of blinding- Inadequate controls- Poorly defined primary outcomes | Animal studies, clinical trials, behavioral research [14] [12] |

Root Cause Analysis Framework

Problem Statement: Experimental results cannot be consistently reproduced across different laboratories or by the same research group over time.

Environment Details: Affects academic, industrial, and government research settings across multiple disciplines including materials science, psychology, and biomedical research.

Possible Causes (prioritized by frequency):

Inadequate Documentation & Sharing

- Insufficient methodological details in publications

- Unavailable raw data, code, or research materials

- Incomplete reporting of experimental conditions

Biological Material Integrity

- Use of misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines [11]

- Unverified reagent quality and lot-to-lot variability

- Microbial contamination affecting assay results

Statistical & Experimental Design

- Small sample sizes leading to underpowered studies

- p-value misinterpretation and misuse [14]

- Failure to account for multiple comparisons

- Inappropriate statistical models

Cognitive Biases

- Confirmation bias (interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs)

- Selection bias (non-random sampling)

- Reporting bias (suppressing negative results) [11]

Technical Skill Gaps

- Inadequate training in statistical methods

- Lack of expertise with complex instrumentation

- Poor data management practices [14]

Systemic & Cultural Factors

- Pressure to publish novel, positive results

- Undervaluing of negative results replication studies

- Career advancement tied to publication in high-impact journals [11]

Step-by-Step Resolution Process

Quick Fix (Time: Immediate)

- Verify cell line authentication using STR profiling

- Check reagent certificates of analysis

- Confirm statistical power calculations were performed a priori

- Share raw data and analysis code with publication

Standard Resolution (Time: 1-2 Weeks)

- Implement electronic lab notebooks with version control

- Establish standard operating procedures for key assays

- Pre-register study designs and analysis plans

- Conduct random audits of raw data by senior investigators [12]

Root Cause Resolution (Time: 1-6 Months)

- Institutional adoption of FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) [6]

- Create dedicated repositories for negative results

- Reform promotion criteria to value rigorous methods over flashy results

- Implement comprehensive training in experimental design and statistics

Escalation Path: For systemic issues affecting multiple research groups, escalate to institutional leadership, funding agencies, and journal editors to coordinate policy changes.

Validation Step: Successful reproduction is confirmed when independent laboratories can obtain consistent results using the original materials and protocols.

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Reproducibility

FAIR Data Implementation Protocol

The FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data framework is essential for reproducible materials science research [6].

Materials: Electronic lab notebook system, metadata standards, data repository access

Procedure:

- Capture Comprehensive Metadata

- Record sample composition, processing history, and synthesis conditions

- Document instrument calibration and experimental parameters

- Note environmental conditions (temperature, humidity)

Standardize Data Formats

- Use community-approved data standards

- Convert proprietary formats to open, machine-readable formats

- Include detailed README files with data dictionaries

Utilize Repositories

- Deposit data in discipline-specific repositories (e.g., Materials Commons)

- Assign persistent digital object identifiers (DOIs)

- Link datasets to corresponding publications

Automate Metadata Capture

- Integrate metadata services directly into instrumentation

- Use electronic lab notebooks that export standardized formats

- Implement automated data validation checks

Computational Reproducibility Protocol

Materials: Version control system (e.g., Git), computational environment manager (e.g., Conda, Docker), electronic lab notebook

Procedure:

- Document Computational Environment

- Record software versions and dependencies

- Use containerization to capture complete computational environment

- Document operating system and hardware specifications

Implement Version Control

- Maintain all analysis scripts in a version-controlled repository

- Use descriptive commit messages explaining rationale for changes

- Tag specific versions used for publication

Create Reproducible Analysis Pipelines

- Write scripts that execute complete analysis from raw data to final results

- Avoid manual intervention in data processing steps

- Include automated quality control checks

Archive and Share

- Deposit code in recognized repositories (e.g., GitHub, GitLab, Zenodo)

- Include example datasets and unit tests

- Provide detailed documentation for code execution

Materials Authentication Protocol

Materials: Reference standards, authentication assays, cryopreservation equipment, documentation system

Procedure:

- Initial Characterization

- Perform genotypic and phenotypic characterization of all new cell lines

- Establish reference fingerprints using multiple methods

- Cryopreserve early-passage reference stocks

Regular Monitoring

- Test for mycoplasma contamination monthly

- Authenticate cell lines every 10 passages or 3 months

- Monitor phenotypic markers relevant to research application

Documentation

- Maintain complete lineage records from original source

- Document all culture conditions and reagents

- Track passage number and freezing history

Quality Control

- Use multimodal authentication (STR profiling, karyotyping, isoenzyme analysis)

- Compare to reference standards from original sources

- Implement quarantine procedures for new acquisitions

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Items | Function & Importance | Quality Control Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Authentication | - STR profiling kits- Isoenzyme analysis kits- Species-specific PCR panels | Confirms cell line identity and detects cross-contamination, critical as 15-30% of cell lines are misidentified [11] | Quarterly testing, comparison to reference databases, documentation of all results |

| Contamination Detection | - Mycoplasma detection kits- Endotoxin testing kits- Microbial culture media | Identifies biological contaminants that alter experimental outcomes | Monthly screening, immediate testing of new acquisitions, validation of sterilization methods |

| Reference Materials | - Certified reference materials- Authenticated primary cells- Characterized protein standards | Provides benchmarks for assay validation and cross-laboratory comparison | Traceability to national/international standards, verification of certificate authenticity |

| Data Management Tools | - Electronic lab notebooks- Version control systems- Metadata capture tools | Ensures complete experimental documentation and analysis transparency | Automated backup systems, access controls, audit trails for all changes |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the difference between reproducibility and replicability in scientific research?

A1: While definitions vary across disciplines, the American Society for Cell Biology provides a useful framework. Reproducibility typically refers to obtaining consistent results when using the same input data, computational steps, methods, and conditions of analysis. Replicability generally means obtaining consistent results across different studies addressing the same scientific question, often using new data or methods. In practice, reproducibility ensures transparency in what was done, while replicability strengthens evidence through confirmation [11].

Q2: Why should I publish negative results? Doesn't this clutter the literature?

A2: Publishing negative results is essential for scientific progress for several reasons. First, it prevents other researchers from wasting resources pursuing dead ends. Second, it helps correct the scientific record and avoids publication bias. Third, negative results can provide valuable information about assay sensitivity and specificity. Journals specifically dedicated to null results, such as Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, have emerged to provide appropriate venues for this important work [14] [11].

Q3: How can we implement better reproducibility practices when we're under pressure to publish quickly?

A3: Consider that investing in reproducibility practices ultimately saves time by reducing dead-end pursuits and failed experiments. Start with high-impact, low-effort practices: (1) implement electronic lab notebooks with templates for common experiments, (2) pre-register study designs before data collection begins, (3) use version control for data analysis code, and (4) establish standardized operating procedures for key assays. These practices become more efficient with time and can significantly reduce the "replication debt" that costs more time later [12].

Q4: What technological solutions are available to improve computational reproducibility?

A4: Multiple technological solutions have emerged: (1) Containerization platforms (Docker, Singularity) capture complete computational environments, (2) Version control systems (Git) track changes to analysis code, (3) Electronic lab notebooks (Benchling, RSpace) document experimental workflows, (4) Data repositories (Zenodo, Materials Commons) provide permanent storage for datasets, and (5) Workflow management systems (Nextflow, Snakemake) automate multi-step analyses. The key is creating an integrated system that connects these tools [14] [6].

Q5: How effective are these reproducibility interventions in practice?

A5: Evidence is growing that systematic approaches dramatically improve reproducibility. In experimental psychology, a recent initiative where four research groups implemented best practices (pre-registration, adequate power, open data) achieved an ultra-high replication rate of over 90%, compared to typical rates of 36-50% in the field. Similarly, in materials science, implementation of FAIR data principles and advanced simulation tools has significantly improved consistency across laboratories [6] [13].

Visual Workflows for Reproducibility Enhancement

Experimental Planning and Validation Workflow

Data Management and Documentation Workflow

Materials Authentication and Quality Control Workflow

Core Concepts: Uncertainty and Confidence

What is measurement uncertainty and why is it critical for reproducibility in materials science?

Answer: Measurement uncertainty is a non-negative parameter that characterizes the dispersion of values that can be reasonably attributed to a measurand (the quantity intended to be measured) [15]. It is a recognition that every measurement is prone to error and is complete only when accompanied by a quantitative statement of its uncertainty [15]. From a metrology perspective, this is fundamental for addressing reproducibility challenges in materials science, as it allows researchers to determine if a result is fit for its intended purpose and consistent with other results [15]. Essentially, it provides the necessary context to judge whether a subsequent finding genuinely replicates an earlier one or falls within an expected range of variation.

How is a confidence interval defined, and what does it tell us about risk?

Answer: A confidence interval is an estimated range for a population parameter (e.g., a measurement) corresponding to a given probability [16]. It means that if we were to repeatedly sample the same population, the observations would align with the probability set by the confidence interval.

Selecting a confidence interval is also a decision about acceptable risk. The associated risk is quantified by the probability of failure (q), which is the complement of the confidence level. The table below summarizes common confidence intervals used in metrology and their associated risks [16].

Table 1: Common Confidence Intervals and Associated Risk

| Confidence Interval | Expansion Factor (k) | Probability of Failure (q) | Expected Failure Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68.27% | 1 | 31.73% | 1 in 3 |

| 95.00% | 1.96 | 5.00% | 1 in 20 |

| 95.45% | 2 | 4.55% | 1 in 22 |

| 99.73% | 3 | 0.27% | 1 in 370 |

For a laboratory performing millions of measurements, a 4.55% failure rate can lead to tens of thousands of nonconformities, highlighting the importance of selecting a confidence level appropriate to the scale and consequences of the work [16].

What is the difference between measurement error and measurement uncertainty?

Answer: While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, error and uncertainty have distinct meanings in metrology [15].

- Measurement Error: This is the difference between the true value and the measured value. The true value is ultimately indeterminate, so error cannot be known exactly [15].

- Measurement Uncertainty: This characterizes the dispersion of possible measured values around the best estimate. It is a quantitative indicator of the reliability of a measurement result [15].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between a measured value, its uncertainty, and the conceptual "true value."

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

A Systematic Framework for Troubleshooting Experimental Measurements

Effective troubleshooting is an essential skill for researchers [17] [18]. The following workflow provides a general methodology for diagnosing problems with measurements or experimental protocols. This structured approach can be applied broadly across different experimental domains.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Identify the Problem: Define the problem clearly without assuming the cause. Example: "The measured value is outside the predicted confidence interval," not "The sensor is broken" [17].

- List All Possible Explanations: Brainstorm every potential cause, from the obvious to the subtle. Consider reagents, instruments, environmental conditions, software, and procedural errors [17]. For a measurement system, this list should include random and systematic error sources [15].

- Collect Data: Review all available information. Examine control samples, verify instrument calibration and service logs, confirm environmental conditions (temperature, humidity), and double-check your documented procedure against the standard protocol [17] [18].

- Eliminate Explanations: Use the collected data to rule out causes that are not supported by the evidence [17].

- Check with Experimentation: Design targeted experiments to test the remaining hypotheses. This might involve testing a standard reference material, using a different measurement technique, or systematically varying one parameter at a time [17].

- Identify the Root Cause: Based on the experimental results, identify the most likely cause. Implement a fix, such as recalibrating an instrument or modifying a protocol, and then redo the original experiment to confirm the issue is resolved [17].

FAQ: Common Challenges in Measurement and Reproducibility

Q: What are the most common types of errors I need to consider in my uncertainty budget?

A: Experimental errors are broadly classified into two categories, both of which contribute to measurement uncertainty [15]:

- Systematic Error (Bias): A consistent, reproducible error associated with a non-ideal measurement condition. Theoretically, it can be corrected if the bias and its uncertainty are known. Example: A scale that always reads 1.0 gram low. The uncertainty of the correction must be included in the overall uncertainty budget [15].

- Random Error: Unpredictable variations that influence the measurement process. These are analyzed statistically and are characterized by the precision (or standard deviation) of replicate measurements [15].

Q: Our team cannot reproduce a material synthesis protocol from a literature. What could be wrong?

A: This is a common reproducibility challenge. The issue often lies in incomplete reporting of critical parameters or data handling practices. Key areas to investigate include [2] [19]:

- Software & Data Dependencies: The original work may have used specific software versions, libraries, or code that are not fully documented or shared [19].

- Material History: The properties of materials can be sensitive to their processing history, heat treatment, or supplier, details which are sometimes omitted from methods sections [6].

- Implicit Protocols: Subtle but crucial techniques (e.g., specific aspiration methods during cell washing) may not be described in the manuscript but are vital for success [18].

- Data Analysis Transparency: A lack of clarity in how raw data was processed to reach the final conclusions can hinder robustness checks and replicability [2].

Q: What practical steps can I take to improve the reproducibility of my own work?

A: Embracing transparency throughout the research lifecycle is key [2].

- For Authors: Document and share more than just the final optimized protocol. Consider what was tried and did not work. Share underlying data, code, and materials in community-accepted repositories to make your work more usable for others [2] [6].

- In the Lab: Develop a "reproducibility culture" [2]. Implement structured troubleshooting exercises, like "Pipettes and Problem Solving" [18], to train team members. Use metadata services that automatically log sample composition and processing history—"the information you'd write in a lab notebook"—and permanently link it to datasets [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Materials Science

| Item | Function / Description | Importance for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Materials with certified properties used for instrument calibration and method validation. | Provides a benchmark to correct for systematic error (bias) and validate the entire measurement process, ensuring traceability [15]. |

| Control Samples | Well-characterized positive and negative controls included in every experimental run. | Essential for distinguishing true experimental results from artifacts and for troubleshooting when problems arise [17] [18]. |

| FAIR Data Infrastructure | Tools and platforms that make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. | Prevents data from being "siloed" and enables results from one experiment to become a foundation for the next, accelerating research [6]. |

| Metadata Services | Systems that automatically capture and log experimental details (e.g., sample history, instrument parameters). | Creates a permanent, searchable record of the "lab notebook" information that is crucial for others to understand and replicate an experiment [6]. |

| Virtual Simulation Tools | Software like MechVDE that allows for simulated diffraction experiments in a virtual beamline. | Enables researchers to plan and refine experiments before beamtime, developing deeper intuition and asking better questions, which leads to more robust experimental design [6]. |

Building a Reproducible Workflow: From Lab Bench to Data Analysis

Best Practices for Detailed Experimental Protocol Design and Documentation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical elements to include in an experimental protocol to ensure it can be reproduced by other researchers? A comprehensive protocol should include 17 key data elements to facilitate execution and reproducibility. These ensure anyone, including new lab trainees, can understand and implement the procedure [20] [21]. Critical components include:

- Detailed Workflow: A full description of all steps and their sequence.

- Specific Parameters: Precise information on reagents, equipment, and experimental conditions (e.g., exact temperatures, durations, concentrations). Avoid ambiguities like "store at room temperature" [20].

- Troubleshooting Steps: Guidance on common problems and their solutions, which is often learned through hands-on experience [21].

Q2: My experiments are producing inconsistent results. What are the first things I should check? Begin by systematically reviewing these areas to identify sources of error or variability [22]:

- Reagents: Verify that reagents are fresh, pure, stored correctly, and that you are using the same lot numbers to minimize variability. Test new lots before using them in critical experiments [23] [22].

- Equipment: Ensure all equipment is properly calibrated, maintained, and functioning correctly [23] [22].

- Controls: Confirm that your positive and negative controls are valid, reliable, and performing as expected [22].

- Environmental Parameters: Check for consistency in factors like incubation temperatures, buffer pH, and seasonal changes in lab temperature [23].

Q3: How can I determine the right number of biological replicates for my experiment? The number of biological replicates (sample size) is fundamental to statistical power and is more important than the sheer quantity of data generated per sample (e.g., sequencing depth) [24]. To optimize sample size:

- Perform a Power Analysis: This statistical method calculates the replicates needed to detect a specific effect size with a certain probability. It requires you to define the expected effect size, within-group variance, false discovery rate, and desired statistical power [24].

- Avoid Pseudoreplication: Ensure your replicates are truly independent experimental units that can be randomly assigned to a treatment. Using the wrong unit of replication inflates sample size and can lead to false positives [24].

Q4: How can I make my data visualizations and diagrams accessible to all readers, including those with color vision deficiencies?

- Use Highly Contrasting Colors: Choose colors with sufficient differences in hue, saturation, and lightness. You can even use different shades of the same color if the contrast is high enough [25].

- Test for Accessibility: Use tools like "Viz Palette" to simulate how your chosen color palette appears to individuals with different types of color blindness [25].

- Follow Contrast Ratios: For diagrams and web-based tools, ensure a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for standard text and 3:1 for user interface components, per WCAG guidelines [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unexpected or Inconsistent Experimental Results

| Troubleshooting Step | Key Actions | Documentation Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Check Assumptions | Re-examine your hypothesis and experimental design. Unexpected results may be valid findings, not errors [22]. | "Hypothesis re-evaluated on [Date]." |

| Review Methods | Scrutinize reagents, equipment, and controls. Confirm equipment calibration and reagent lot numbers [23] [22]. | "Lot #XYZ of [Reagent] confirmed; equipment calibrated on [Date]." |

| Compare Results | Compare your data with published literature, databases, or colleague results to identify discrepancies or outliers [22]. | "Results compared with [Author, Year]; discrepancy in [Parameter] noted." |

| Test Alternatives | Explore other explanations. Use different methods or conditions to test new hypotheses [22]. | "Alternative hypothesis tested via [Method] on [Date]." |

| Document Process | Keep a detailed record of all steps, findings, and changes in a lab notebook or digital tool [22]. | All steps recorded in Lab Notebook #X, page Y. |

| Seek Help | Consult supervisors, colleagues, or external experts for fresh perspectives and specialized knowledge [22]. | "Discussed with [Colleague Name] on [Date]; suggestion to [Action]." |

Guide 2: Ensuring Protocol Reproducibility

| Challenge | Solution | Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Detail | Use a pre-defined checklist to ensure all necessary information is included during the writing process [20] [21]. | Adopt reporting guidelines and checklists from consortia or journals [21]. |

| Protocol Drift | Write protocols as living documents. Use version control on platforms like protocols.io to track changes over time [21]. | "Protocol version 2.1 used for all experiments beginning [Date]." |

| Unfindable Materials | Use Research Resource Identifiers (RRIDs) for key biological resources and deposit new resources (e.g., sequences) in databases [21]. | "Antibody: RRID:AB_999999." |

| Isolated Protocols | Share full protocols independently from papers on repositories like protocols.io to generate a citable DOI [21]. | "Full protocol available at: [DOI URL]" |

Essential Data Tables for Protocol Documentation

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Documenting reagents with precise identifiers is crucial for consistency and troubleshooting [23] [21].

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specification & Lot Tracking |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Retention Pipette Tips | Ensures accurate and precise liquid dispensing, improving data robustness by dispensing the entire sample [23]. | Supplier: [e.g., Biotix]; Lot #: ___; Quality Check: CV < 2% |

| Cell Culture Media | Provides a consistent and optimal environment for growing cells or microorganisms. | Supplier: _; Lot #: _; pH Verified: Yes/No |

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to a target protein of interest in an immunoassay. | RRID: _; Supplier: ; Lot #: __ |

| Chemical Inhibitor | Modulates a specific biological pathway to study its function. | Supplier: _; Lot #: _; Solvent: DMSO/PBS etc. |

Table 2: Accessible Color Palettes for Data Visualization

Use these HEX codes to create figures that are clear for audiences with color vision deficiencies. Test palettes with tools like Viz Palette [25].

| Color Use Case | HEX Code 1 | HEX Code 2 | HEX Code 3 | HEX Code 4 | Contrast Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Color Bar Graph | #3548A9 |

#D14933 |

- | - | 6.8:1 |

| Four-Color Chart | #3548A9 |

#D14933 |

#49A846 |

#8B4BBF |

> 4.5:1 |

| Sequential (Low-High) | #F1F3F4 |

#B0BEC5 |

#78909C |

#37474F |

> 4.5:1 |

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Experimental Protocol Development and Troubleshooting Workflow

Diagram 2: Systematic Troubleshooting Pathway for Unexpected Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is proper labeling of reagents and materials critical for research reproducibility? Incomplete or inaccurate labels are a primary source of error, leading to the use of wrong reagents, failed experiments, and costly mistakes. Proper labeling is a fundamental quality control step that ensures every researcher can correctly identify materials and their specific properties, which is essential for replicating experimental conditions and obtaining reliable results [28].

Q2: What are the absolute minimum requirements for a chemical container label? At a minimum, every chemical container must be labeled with the full chemical name written in English and its chemical formula [29] [28]. Relying on formulas, acronyms, or abbreviations alone is insufficient unless a key is publicly available in the lab [29].

Q3: What additional information should be included on a label for optimal quality control? To enhance safety and reproducibility, labels should also include [28]:

- Hazard Pictograms: Universally recognized symbols for quick risk identification.

- Concentration and Purity Levels: Essential for experimental consistency and accurate chemical reactions.

- Date of Receipt/Preparation: Helps track material age and manage inventory.

- Supplier Information: Allows for traceability.

Q4: My lab is developing a new labeling system. What standard should we follow? All labels should adhere to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) guidelines. This ensures global consistency and regulatory compliance. GHS-compliant labels include standardized hazard pictograms, signal words ("Danger" or "Warning"), hazard statements, and precautionary statements [28].

Q5: How often should we audit and update our chemical labels? Labels and their corresponding Safety Data Sheets (SDS) should be reviewed regularly, at least annually, and whenever a new supply batch arrives or a regulation changes. This proactive practice helps avoid safety issues and compliance gaps [28].

Q6: How can misidentified cell lines affect my research? Using misidentified, cross-contaminated, or over-passaged cell lines is a major contributor to irreproducible results [11]. These compromised biological materials can have altered genotypes and phenotypes (e.g., changes in gene expression, growth rates), invalidating your results and any conclusions drawn from them [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Experimental Results Between Technicians

Possible Cause: Variability in reagent preparation or use due to unclear labeling or a lack of standardized procedures.

Solution:

- Standardize Procedures: Implement and document detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for preparing and handling all common reagents.

- Enhance Labeling: Ensure all labels include precise concentration, purity, and preparation date.

- Train Personnel: Conduct regular training for all lab members on the labeling system and SOPs, especially when new personnel join or new chemicals are introduced [29].

Problem: Suspected Contamination or Degradation of a Reagent

Possible Cause: Improper storage, outdated materials, or use of an unauthenticated biological material.

Solution:

- Check Label: Verify the receipt/preparation date and expiration date.

- Authenticate Biomaterials: Use only authenticated, low-passage reference materials for experiments. Starting with traceable and validated biomaterials greatly improves data reliability [11].

- Quarantine: Isolate the suspected reagent and perform a quality control test (e.g., pH check, microbial culture) before use.

- Dispose and Replace: If contamination or degradation is confirmed, dispose of the material safely and prepare a new, properly labeled batch.

Problem: Inability to Reproduce a Published Study's Findings

Possible Cause: A lack of access to the original study's methodological details, raw data, or specific research materials [11].

Solution:

- Review Methods Scrutinize: the original publication for a thorough description of methods, including key parameters like reagent suppliers, catalog numbers, lot numbers, and preparation protocols [11].

- Request Materials: Contact the corresponding author to request key reagents or cell lines.

- Document Meticulously: In your own work, maintain detailed records and robust sharing practices for data and protocols to contribute to the collective reproducibility of your field [11].

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assurance

Protocol 1: Implementing a GHS-Compliant Labeling System

Objective: To ensure all chemicals in the laboratory are safely and consistently labeled, meeting global regulatory standards.

Materials:

- GHS label templates or a label printer.

- Permanent markers, tape (for temporary fixes).

- Safety Data Sheets (SDS).

- Laboratory inventory logbook.

Methodology:

- Inventory Audit: Identify all unlabeled, poorly labeled, or defaced containers.

- GHS Classification: For each chemical, consult its SDS to determine the correct hazard class and corresponding pictogram.

- Label Creation: Create a new label containing the following:

- Product Identifier (Chemical name and formula).

- Signal Word ("Danger" or "Warning").

- Hazard Pictogram(s).

- Hazard Statement(s).

- Precautionary Statement(s).

- Supplier Information.

- Date of Preparation/Receipt.

- Application: Securely affix the new label to the clean, dry container. If a label is degrading, re-label the container or transfer the chemical to a new one [29].

- Training: Train all laboratory personnel on the new labeling system, ensuring they understand all GHS elements [29] [28].

Protocol 2: Cell Line Authentication and Contamination Testing

Objective: To verify the identity and purity of cell lines to prevent experiments from being conducted with misidentified or contaminated models.

Materials:

- Cell culture sample.

- Mycoplasma detection kit (e.g., PCR-based or staining kit).

- Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling service or kit.

- Microscope.

Methodology:

- Visual Inspection: Observe cell morphology under a microscope for any unusual characteristics.

- Mycoplasma Testing: Perform a mycoplasma test according to the kit's protocol. This is a common contamination that affects cell behavior.

- STR Profiling: Send a cell sample to a dedicated facility for STR profiling, which is the standard method for authenticating human cell lines.

- Documentation: Record all test results, including the date, passage number of the cells tested, and the final authentication report. Only use cell lines that have passed these quality controls for critical experiments [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential items for ensuring reagent quality and traceability.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| GHS-Compliant Labels | Standardized labels that communicate hazard and precautionary information clearly for safety and compliance [28]. |

| Safety Data Sheets (SDS) | Detailed documents providing comprehensive information about a chemical's properties, hazards, and safe handling procedures [28]. |

| Authenticated, Low-Passage Cell Lines | Biological reference materials that are verified for identity and purity, ensuring experimental data is generated from the correct model system [11]. |

| Centralized Inventory Logbook (Digital or Physical) | A system for tracking all reagents, including dates of receipt, opening, and expiration, to manage stock and prevent use of degraded materials. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | A crucial tool for routine screening of cell cultures for a common and destructive contaminant [11]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Quality Control Workflow for New Reagents

Troubleshooting Path for Irreproducible Results

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common FAIR Implementation Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Common Issue | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Findability | Data cannot be found by collaborators or yourself after some time. | Inconsistent file naming, no central searchable index [30]. | Assign a Persistent Identifier (PID) like a DOI from a certified repository (e.g., Zenodo, Dryad) [31] [30]. |

| Accessibility | Data is stored on a personal device or institutional drive with no managed access. | Data becomes unavailable if the individual leaves or the hardware fails [30]. | Deposit data in a trusted repository that provides a standardised protocol for access [30]. |

| Interoperability | Data from different groups or experiments cannot be combined or compared. | Use of proprietary file formats, lack of shared vocabulary [32]. | Use common, open formats (e.g., CSV, HDF5) and community ontologies/vocabularies (e.g., MatWerk Ontology) [32] [30]. |

| Reusability | Other researchers cannot understand or reuse published data. | Missing information about experimental conditions, parameters, or data processing steps [31]. | Create a detailed README file and assign a clear usage license (e.g., CC-BY, CC-0) [31] [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Does making my data FAIR mean I have to share it openly with everyone? A: No. FAIR and open are distinct concepts. Data can be FAIR but not open, meaning it is richly described and accessible in a controlled way (e.g., under embargo or for specific users), but not publicly available. Conversely, data can be open but not FAIR if it lacks sufficient documentation [30].

Q2: What is the most fundamental step to start making my data FAIR? A: The most critical first step is planning and creating rich, machine-readable metadata. Metadata is the backbone of findability and reusability. Before data generation ends, define the metadata schema you will use, ideally based on community standards [33] [30].

Q3: My data is stored in a Git repository. Is that sufficient for being FAIR? A: Git provides version control, which is excellent for reusability and tracking changes [31]. However, for data to be fully FAIR, it should also have a Persistent Identifier (PID) and be in a stable, archived environment like a data repository. A common practice is to use Git for active development and then archive a specific version in a repository like Zenodo to mint a DOI [30].

Q4: How can I handle the additional time required for FAIR practices? A: Integrate FAIR practices into your existing workflows. Use tools like Electronic Laboratory Notebooks (ELNs) (e.g., PASTA-ELN) and version control from the start of a project. This reduces overhead by making documentation a natural part of the research process rather than a post-hoc task [7] [32].

Experimental Protocols for FAIRification

This protocol outlines the methodology for a collaborative study on determining the elastic modulus of an aluminum alloy (EN AW-1050A), replicating a real-world scenario where multiple groups and methods are integrated [32].

Experimental Workflow (Nanoindentation)

- Objective: Perform indentation-based measurements and evaluate Young's modulus using the Oliver-Pharr method.

- Procedure:

- Prepare the aluminum alloy sample.

- Conduct nanoindentation tests using a standardized machine.

- Record all raw data and instrument parameters directly into an Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) (e.g., PASTA-ELN) to ensure structured data capture and provenance [32].

- Apply the Oliver-Pharr method for analysis within the ELN environment.

Data Analytic Workflow (Image Processing)

- Objective: Process confocal images of indents to determine the contact area from height profiles.

- Procedure:

- Acquire confocal images of the indentation sites.

- Use an image processing platform (e.g., Chaldene) to execute a workflow that analyzes the height profiles [32].

- Apply the Sneddon equation to calculate the contact area.

- Output the results in a standardized, open format (e.g., CSV) with all processing parameters documented.

Computational Workflow (Molecular Statics Simulations)

- Objective: Determine the elastic moduli via atomistic simulations.

- Procedure:

- Use a simulation workflow execution tool (e.g., pyiron) to set up and run molecular statics simulations [32].

- Calculate the energy of different atomistic configurations.

- Execute large simulation ensembles, leveraging the tool's scalability.

- Extract the elastic moduli from the simulation outputs.

Data Management Workflow (FAIR Integration)

- Objective: Harmonize and store data and metadata from all workflows for collaboration and publication.

- Procedure:

- Metadata Alignment: Map all generated metadata to a shared ontology (e.g., the MatWerk Ontology) to ensure semantic interoperability [32].

- Data Storage: Store structured datasets and their aligned metadata in a dedicated data management platform (e.g., Coscine) and a Git repository for code and scripts [32].

- Knowledge Graph Integration: Inject the harmonized metadata into a domain-specific knowledge graph (e.g., the MSE Knowledge Graph) to make it findable and linkable [32].

- Publication: Deposit final, curated datasets into a certified repository to mint Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) and enable citation [30].

FAIR Workflow Integration

The diagram below illustrates the interaction between the different scientific workflows and the central role of the FAIR data management process.

| Tool Category | Example | Function in FAIR Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | PASTA-ELN [32] | Provides a centralized framework for research data management during experiments; structures data capture and ensures provenance. |

| Computational Frameworks | pyiron [32] | Integrates FAIR data management components within a comprehensive environment for numerical modeling and workflow execution. |

| Image Processing Platforms | Chaldene [32] | Executes reproducible image analysis workflows, generating standardized outputs. |

| Data & Code Repositories | Zenodo, Dryad, GitLab [31] [32] [30] | Stores, shares, and preserves data and code; assigns Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) for findability and citation. |

| Metadata & Ontology Resources | MatWerk Ontology, Dublin Core [32] [30] | Provides standardized, machine-readable terms and relationships to ensure semantic interoperability and rich metadata. |

| Data Management Platforms | Coscine [32] | A platform for handling and storing research data and its associated metadata from various sources in a structured way. |

The Role of Digital Tools and AI in Standardizing and Automating Documentation

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This support center is designed to help researchers address common challenges in materials science experiments, with a specific focus on enhancing reproducibility and stability through digital tools and AI.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can AI help with the irreproducibility of material synthesis? AI-assisted systems can tackle material irreproducibility by using automated synthesis and characterization tools. These systems control parameters with very high precision, create massive datasets, and allow for methodical comparisons from which unbiased conclusions can be drawn. This systematic control significantly reduces batch-to-batch variability [34].

Q2: My experimental results are inconsistent. What should I check first? Inconsistency often stems from subtle variations in experimental conditions. We recommend:

- Verify Precursor Mixing: Ensure your precursor solutions are mixed consistently using automated liquid-handling systems to minimize human error [35].

- Monitor with Computer Vision: Use integrated cameras and visual language models to monitor experiments in real-time. The system can detect millimeter-sized deviations in a sample's shape or equipment misplacement and suggest corrective actions [35].

- Audit Your Data: Confirm that all experimental parameters and environmental conditions are being automatically logged in a centralized database for every experiment [36].

Q3: What is the role of automated documentation in a research environment? Automated documentation is crucial for maintaining a single source of truth. It works by:

- Automating Data Capture: Pulling data directly from instruments and integrated enterprise systems, eliminating manual and error-prone data entry [36].

- Ensuring Consistency: Using pre-designed, standardized templates for experiment logs and reports to ensure uniformity [37].

- Creating Audit Trails: Automatically tracking changes and maintaining version history, which enhances accountability and allows for better management of your experimental documentation [37].

Q4: How can I use our lab's historical data to improve future experiments? AI and machine learning can analyze your historical data to reveal otherwise unnoticed trends. This analysis can then inform the design of future experiments by predicting outcomes and identifying the experiments with the highest potential information gain, thereby accelerating your research cycle [34].

Troubleshooting Specific Experimental Issues

Issue: Poor Reproducibility in Halide Perovskite Film Formation

| Problem Description | Material properties and performance vary significantly between synthesis batches. |

|---|---|

| Digital/AI Solution | Implement a closed-loop AI system that uses active learning. The system suggests new synthesis parameters based on prior results, which are then executed by automated robotic equipment. This creates a feedback loop that continuously optimizes the processing pathway [34]. |

| Required Tools | Automated spin coater or deposition system, in-situ characterization tools (e.g., photoluminescence imaging), data management platform, AI model for data analysis and experiment planning. |

| Step-by-Step Protocol | 1. Input Initial Parameters: Define a range for precursor concentration, annealing temperature, and time into the AI system. 2. Run Automated Synthesis: Use robotic systems to synthesize films across the initial parameter space. 3. Automated Characterization: Characterize the films for properties like photoluminescence yield and stability. 4. AI Analysis & New Proposal: The AI analyzes the results, identifies correlations, and proposes a new set of parameters likely to yield better results. 5. Iterate: Repeat steps 2-4 until the target performance and reproducibility are achieved. |

Issue: Low Catalytic Activity and High Cost in Fuel Cell Catalyst Screening

| Problem Description | Traditional trial-and-error methods for discovering multielement catalysts are slow and costly, especially when relying on precious metals. |

|---|---|

| Digital/AI Solution | Use a multimodal AI platform that incorporates knowledge from scientific literature, existing databases, and real-time experimental data to optimize material recipes. The system can explore vast compositional spaces efficiently [35]. |

| Required Tools | High-throughput robotic synthesizer (e.g., liquid-handling robot, carbothermal shock system), automated electrochemical workstation, electron microscopy, multimodal AI platform (e.g., CRESt) [35]. |

| Step-by-Step Protocol | 1. Literature Knowledge Embedding: The AI creates representations of potential recipes based on existing scientific text and databases. 2. Define Search Space: Use principal component analysis to reduce the vast compositional space to a manageable, promising region. 3. Robotic Experimentation: The system automatically synthesizes and tests hundreds of catalyst compositions. 4. Multimodal Feedback: Performance data, microstructural images, and human feedback are fed back into the AI model. 5. Optimize: The AI uses Bayesian optimization in the reduced search space to design the next round of experiments, rapidly converging on high-performance solutions [35]. |

Quantitative Data on AI-Driven Experimentation

The following table summarizes performance data from a real-world implementation of an AI-driven platform for materials discovery.

| AI Platform / System | Number of Chemistries Explored | Number of Tests Conducted | Key Achievement | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRESt Platform [35] | >900 | 3,500 electrochemical tests | Discovery of an 8-element catalyst with a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium; record power density in a direct formate fuel cell. | 3 months |

Experimental Protocol: AI-Assisted Closed-Loop Discovery of Functional Materials

Objective: To autonomously discover and optimize a multielement catalyst with high activity and reduced precious metal content.

Methodology:

Setup:

- Load precursor solutions for up to 20 candidate elements into a liquid-handling robot [35].

- Define initial search constraints (e.g., elemental ratios, temperature ranges) based on literature and domain knowledge.

- Integrate robotic synthesizer with characterization equipment (e.g., automated electron microscope, electrochemical workstation).

AI-Guided Workflow Execution:

- The AI's large language model processes scientific literature to create an initial knowledge base and suggest promising compositional spaces [35].

- An active learning loop, powered by Bayesian optimization, is initiated. The AI selects the most informative experiments to run next based on all accumulated data [35].

- The robotic system executes the suggested experiments: synthesizing materials, characterizing their microstructure, and testing their functional performance.

Data Integration and Analysis:

- All multimodal data (chemical composition, images, performance metrics) is automatically logged into a centralized repository [37].

- Computer vision models monitor the experiments, detecting issues like sample misplacement and suggesting corrections to maintain reproducibility [35].

- The AI model is retrained with the new data, refining its understanding and improving its predictions for subsequent experiment cycles.

Validation:

- The best-performing material identified by the AI system is independently validated using standard testing protocols to confirm its performance and stability [35].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Closed-Loop Materials Discovery Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources used in automated, AI-driven materials science platforms.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Automated Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Multielement Precursor Solutions [35] | Serves as the source of chemical elements for the high-throughput synthesis of diverse material compositions explored by the AI. |

| Formate Fuel Cell Electrolyte [35] | Provides the operational environment for testing the functional performance (power density, catalytic activity) of newly discovered materials. |

| Halide Perovskite Precursors [34] | Used in automated synthesis systems to systematically produce thin films for optimizing optoelectronic properties and solving reproducibility challenges. |

| Liquid-Handling Robot Reagents [35] | Enables precise, automated dispensing and mixing of precursor solutions in high-throughput experimentation, minimizing human error. |

Identifying and Overcoming Common Pitfalls in Experimental and Computational Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common technical barriers to reproducing a materials informatics study? The most frequent technical barriers involve issues with software environment and code structure. Specifically, researchers often encounter problems with unreported software dependencies, unshared version logs, non-sequential code organization, and unclear code references within manuscripts [19] [38]. Without these elements properly documented, recreating the exact computational environment becomes challenging.

Q2: What specific practices can ensure my materials informatics code is reproducible? Implement these key practices:

- Explicit Dependency Management: Use environment files (e.g.,

environment.yml) to pin all library versions [19]. - Version Control & Logs: Maintain a public repository (like GitHub) with a detailed change log [19].

- Sequential Code Organization: Structure your code and manuscript so that each calculation and analysis step can be executed and understood in a logical, linear sequence [19].

Q3: My model's performance drops significantly on new data. What could be wrong? This is often a sign of overfitting or an issue with your data's representativeness. To diagnose:

- Check if there's a large difference in Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R-squared values between your training and test sets [39].

- Ensure your dataset is large enough and that the fingerprint/descriptors used are relevant to the property you are predicting [39].

- Consider using algorithms with built-in regularization, like Lasso regression, to help mitigate overfitting [39].

Q4: What is the difference between the "prediction" and "exploration" approaches in MI? These are two primary application paradigms [40]:

- Prediction: Uses a trained machine learning model to predict properties of new materials based on a static dataset. It is best for interpolation within known data boundaries.

- Exploration (Bayesian Optimization): An iterative approach that uses both the predicted mean and uncertainty of a model to intelligently select the next experiment or calculation. It is designed for efficiently discovering new materials with optimal properties, especially in data-scarce regimes.

Q5: How can I convert a chemical structure into a numerical representation for a model? This process is called feature engineering or fingerprinting. Two common methods are:

- Knowledge-Based Descriptors: Manually create features based on chemical knowledge, such as molecular weight, number of specific atoms, or average electronegativity [39] [40].

- Automated Feature Extraction: Use algorithms like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to automatically learn feature representations from the molecular graph structure, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Environment Configuration and Dependency Errors

Problem: Code fails to run due to missing libraries, incorrect library versions, or conflicting packages.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

ModuleNotFoundError or ImportError |

A required Python package is not installed. | Create a comprehensive requirements.txt file that lists all direct dependencies [19]. |

| Inconsistent or erroneous results | A critical package (e.g., numpy, scikit-learn) has been updated to an incompatible version. |

Use a virtual environment and pin the exact version of every dependency, including transitive ones. Tools like pip freeze can help generate this list [19]. |

| "This function is deprecated" warnings | The code was written for an older API of a library. | Record and share the version logs of all major software used at the time of the original research [19]. |

Issue 2: Poor Model Performance and Overfitting

Problem: Your machine learning model performs well on the training data but poorly on the test data or new, unseen data.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High training R², low test R² | The model has overfitted to the noise in the training data. | 1. Use simpler models or models with regularization (e.g., Lasso, Ridge) [39].2. Increase the size of your training dataset.3. Reduce the number of features or use feature selection. |

| High RMSE on both training and test sets | The model is underfitting; it's not capturing the underlying trend. | 1. Use more complex models (e.g., Gradient Boosting, Neural Networks) [40].2. Improve your feature engineering to include more relevant descriptors [39]. |

| Large gap between training and test RMSE | The test set is not representative of the training data, or data has leaked from training to test. | Ensure your data is shuffled and split randomly before training. Use cross-validation for a more robust performance estimate. |

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below outlines a reproducible workflow for a materials informatics study, integrating key steps to avoid common pitfalls.

Issue 3: Data Collection and Fingerprinting Challenges

Problem: Difficulty in acquiring sufficient, high-quality data or converting molecular structures into meaningful numerical descriptors.

| Challenge | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstructured Data | Materials data is often locked in PDFs or scattered across websites [39]. | Use automated web scraping tools (e.g., BeautifulSoup in Python) and text parsing techniques to build datasets [39]. |

| Creating Fingerprints | Designing a numerical representation (fingerprint) that captures relevant chemical information [39]. | Start with simple knowledge-based descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, valence electron count). For complex systems, consider using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for automated feature extraction [40]. |

| Data Scarcity | Limited experimental or computational data for training accurate models. | Integrate with computational chemistry. Use high-throughput simulations (e.g., with Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials) to generate large, accurate datasets for training [40]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key resources and their functions for conducting reproducible materials informatics research.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Software Environment Manager (e.g., Conda) | Creates isolated and reproducible computing environments to manage software dependencies and versions [19]. | Always export the full environment specification (environment.yml) for colleagues. |

| Version Control System (e.g., Git) | Tracks all changes to code and manuscripts, allowing you to revert mistakes and document evolution [19]. | Host repositories on platforms like GitHub or GitLab for public sharing and collaboration. |

| Web Scraping Library (e.g., BeautifulSoup) | Automates the extraction of unstructured materials data from websites and online databases [39]. | Always check a website's robots.txt and terms of service before scraping. |

| Cheminformatics Library (e.g., RDKit) | Generates molecular fingerprints and descriptors from chemical structures (often provided as SMILES strings) [39]. | Essential for converting a molecule into a numerical feature vector for machine learning. |

| Machine Learning Library (e.g., scikit-learn) | Provides a wide array of pre-implemented algorithms for both prediction (Linear Regression, SVM) and exploration (Bayesian Optimization) [39] [40]. | Start with simple, interpretable models before moving to more complex ones like neural networks. |

| Graph Neural Network Library (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | Enables automated feature learning directly from the graph representation of molecules and crystals [40]. | Particularly powerful when working with large datasets and complex structure-property relationships. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Variability Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias in Results | Subjective outcomes are consistently skewed in favor of the hypothesized outcome [41]. | Lack of blinding: Outcome assessors are influenced by their knowledge of which group received the experimental treatment [41] [42]. | Implement blinding for outcome assessors and data analysts. Use centralized or independent adjudicators who are unaware of group assignments [41] [42]. |

| High background noise obscures the signal of the experimental effect [43]. | Inadequate controls: The experiment lacks proper negative controls to account for background noise or procedural artifacts [44] [43]. | Include both positive and negative controls to establish a baseline and identify confounding variables [44]. | |

| High Variance & Irreproducibility | Experimental error is too large, making it difficult to detect a significant effect [45]. | Insufficient replication: The experiment has not been repeated enough times to reliably estimate the natural variation in the system [45]. | Increase true replication (applying the same treatment to multiple independent experimental units) to obtain a better estimate of experimental error [45]. |

| Results cannot be reproduced by other research groups using the same methodology [19] [4]. | Unreported variables: Critical computational dependencies, software versions, or detailed protocols are not documented or shared [19] [4]. | Meticulously document and share all software dependencies, version logs, and code in a sequential, well-organized manner [19] [4]. | |

| Confounding Factors | An effect is observed, but it may be due to an unmeasured variable rather than the treatment [44]. | Ineffective randomization: Uncontrolled "lurking" variables are systematically influencing the results [45]. | Properly randomize the order of all experimental runs to average out the effects of uncontrolled nuisance factors [45]. |

| A known nuisance factor (e.g., different material batches, testing days) is introducing unwanted variability [45]. | Failure to block: The experimental design does not account for known sources of variation [45]. | Use a blocked design to group experimental runs and balance the effect of the nuisance factor across all treatments [45]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)