Solving the Depth Dilemma: A Strategic Guide to Troubleshooting Low Sequencing Depth in Metagenomic Studies

Low sequencing depth is a critical bottleneck that can compromise the validity of metagenomic findings, particularly for detecting rare taxa, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, and strain-level variations.

Solving the Depth Dilemma: A Strategic Guide to Troubleshooting Low Sequencing Depth in Metagenomic Studies

Abstract

Low sequencing depth is a critical bottleneck that can compromise the validity of metagenomic findings, particularly for detecting rare taxa, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, and strain-level variations. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose, mitigate, and validate findings from shallow-depth sequencing. Drawing on current evidence, we detail how insufficient depth skews microbial and resistome profiles, offer pre-sequencing and bioinformatic strategies for optimization, and establish robust methods for data validation and cross-platform comparison to ensure research reproducibility and clinical relevance.

Why Depth Matters: The Fundamental Impact on Microbiome and Resistome Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between sequencing depth and coverage? A1: While often used interchangeably, these terms describe distinct metrics:

- Sequencing Depth (or read depth): Refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide base is read during sequencing. It is expressed as an average multiple, such as 30x, which means each base was sequenced 30 times on average [1] [2].

- Coverage: Describes the proportion of the target genome or region that has been sequenced at least once. It is typically expressed as a percentage—for example, 95% coverage means 95% of the target bases are represented by at least one read [1] [2].

Q2: Why is achieving a balance between depth and coverage critical in metagenomic studies? A2: Both are crucial for accurate and reliable data, but they serve complementary roles:

- Depth ensures confidence in base calling and is vital for detecting rare variants or sequencing heterogeneous samples (like tumor tissues or diverse microbial communities) [1] [2].

- Coverage ensures the completeness of your data, guaranteeing that the entirety of the target region is represented and that critical information is not missed due to gaps [1] [3]. In metagenomics, high depth is often necessary to uncover the full richness of genes and allelic diversity, which may not plateau even at very high sequencing depths [4] [5].

Q3: My variant calls are inconsistent. Could low sequencing depth be the cause? A3: Yes. A higher sequencing depth directly increases confidence in variant calls. With low depth, there are fewer independent observations of a base, making it difficult to distinguish a true variant from a sequencing error. This is especially critical for detecting low-frequency variants [2] [3].

Q4: What does "coverage uniformity" mean, and why is it important? A4: Coverage uniformity indicates how evenly sequencing reads are distributed across the genome [3]. Two datasets can have the same average depth (e.g., 30x) but vastly different uniformity. One might have regions with 0x coverage (gaps) and others with 60x, while another has all regions covered between 25-35x. The latter, with high uniformity, provides more reliable and comprehensive biological insights across the entire genome [2] [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Sequencing Depth in Metagenomics

A systematic workflow for diagnosing and addressing low sequencing depth is critical for robust metagenomic analysis.

Diagnostic and Remedial Workflow for Low Sequencing Depth

Step 1: Calculate and Verify Your Actual Sequencing Depth

First, confirm that your observed depth is indeed below the recommended target for your study.

Protocol 1.1: Calculating Average Sequencing Depth

- Determine the total number of usable base pairs generated from your sequencing run (e.g., 90 Gigabases).

- Divide this by the effective genome size or the size of your target region.

- Formula: Average Depth = Total Bases Generated / Target Genome Size [2].

- Example: For a human gut metagenomic sample with an estimated community genome size of 3 Gb, generating 90 Gb of data yields: 90 Gb / 3 Gb = 30x average depth.

Compare your calculated depth against established recommendations for your application:

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depths for Various Applications

| Application / Study Goal | Recommended Depth | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Human Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | 30x - 50x [2] | Balances comprehensive genome coverage with cost for accurate variant calling. |

| Exome / Targeted Gene Mutation Detection | 50x - 100x [2] | Increases confidence for calling variants in specific regions of interest. |

| Cancer Genomics (Somatic Variants) | 500x - 1000x [2] | Essential for detecting low-frequency mutations within a heterogeneous sample. |

| Metagenomic AMR Gene Profiling | 80M+ reads/sample [4] | Required to recover the full richness of antimicrobial resistance gene families. |

| Metagenomic SNP Analysis | Ultra-deep sequencing (e.g., 200M+ reads) [5] | Shallow sequencing misses significant allelic diversity and functionally important SNPs. |

Step 2: Assess and Improve Coverage Uniformity

If depth is adequate but specific genomic regions are consistently poorly covered, investigate coverage uniformity.

Protocol 2.1: Measuring Coverage Uniformity with Interquartile Range (IQR)

- Calculate the read depth for every base position in the genome using tools like

samtools depth. - Compile these depths and calculate the distribution's IQR. A smaller IQR indicates more uniform coverage, while a larger IQR signifies high variability [2].

- Visually inspect the depth distribution across the genome using a plotting tool to identify large gaps or consistently low-coverage regions.

Solution: If uniformity is poor, consider:

- Optimizing Library Preparation: Low-quality or fragmented DNA input can cause biased coverage. Use high-quality, intact DNA and optimize fragmentation and amplification steps [2].

- Utilizing Different Sequencing Technologies: Platforms that produce longer reads can improve coverage in challenging regions like those with high GC content or repeats [2] [3].

Step 3: Verify Sample and Library Quality

Sample issues are a common root cause of low effective depth.

Protocol 3.1: Using Exogenous Spike-Ins for Normalization

- Spike a known amount of exogenous DNA (e.g., from Thermus thermophilus) into your sample before DNA extraction and library preparation [4].

- After sequencing, calculate the ratio of spike-in reads to sample reads.

- This ratio allows for normalization, enabling more accurate cross-sample comparisons and can help diagnose whether low depth is due to sequencing output or sample issues [4].

Step 4: Align Sequencing Strategy with Study Objectives

Ensure your planned depth is sufficient for your specific biological question.

Solution: For applications requiring high sensitivity, such as identifying rare strains or alleles in a metagenomic sample, shallow sequencing is insufficient. One study found that even 200 million reads per sample was not enough to capture the full allelic diversity in an effluent sample, whereas 1 million reads per sample was sufficient for stable taxonomic profiling [4] [5]. If your target is rare variants, you must budget for and plan a significantly higher sequencing depth.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Metagenomic Sequencing Quality Control

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Tiangen Fecal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | Standardized protocol for extracting microbial DNA from complex stool samples, critical for reproducible metagenomic studies [5]. |

| Thermus thermophilus DNA (Spike-in Control) | Exogenous control added to samples to normalize AMR gene abundance estimates and correct for technical variation during sequencing [4]. |

| BBMap Suite | A software package containing tools for read subsampling (downsampling), which is used to empirically evaluate the impact of sequencing depth on results [5]. |

| Trimmomatic | A flexible tool for read trimming, used to remove low-quality bases and adapters, which improves overall data quality and mapping accuracy [5]. |

| ResPipe Software Pipeline | An open-source pipeline for automated processing of metagenomic data, specifically for profiling antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene content [4]. |

| Comprehensive Antimicrobial Resistance Database (CARD) | A curated resource of known AMR genes and alleles, used as a reference for identifying and characterizing resistance elements in metagenomic data [4]. |

In metagenomic sequencing, "sequencing depth" refers to the number of times a given nucleotide in the sample is sequenced, typically measured as the total number of reads generated. This parameter is crucial because it directly determines the resolution and sensitivity of your analysis. Low sequencing depth creates a fundamental challenge: it masks true microbial diversity by failing to detect rare taxa—low-abundance microorganisms that collectively form the "rare biosphere."

The rare biosphere, despite its name, plays disproportionately important ecological roles. These rare taxa can function as a "seed bank" that maintains community stability and robustness, and some contribute over-proportionally to biogeochemical cycles [6]. When sequencing depth is insufficient, these rare taxa are either completely missed or misclassified as sequencing artifacts, leading to a skewed understanding of the microbial community. This problem is particularly acute in clinical and environmental studies where rare pathogens or key functional microorganisms may be present at very low abundances but have significant impacts on health or ecosystem function.

The following sections provide a comprehensive troubleshooting guide to help researchers diagnose, address, and prevent the issues arising from insufficient sequencing depth in their metagenomic studies.

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Solving Low Depth Issues

Problem Identification: Symptoms of Insufficient Sequencing Depth

Table: Common Symptoms and Consequences of Low Sequencing Depth

| Symptom | What You Observe | Underlying Issue |

|---|---|---|

| Inflated Alpha Diversity | Higher than expected diversity in simple mock communities [6] | False positive rare taxa from index misassignment inflate diversity metrics |

| Deflated Alpha Diversity | Lower than expected diversity in complex samples [6] | Genuine rare taxa remain undetected below the sequencing depth threshold |

| Unreplicateable Rare Taxa | Rare taxa appear inconsistently across technical replicates [6] | Stochastic detection of low-abundance sequences makes results unreproducible |

| Biased Community Assembly | Skewed interpretation of community assembly mechanisms [6] | Missing rare taxa leads to incorrect inference of ecological processes |

| Reduced Classification Precision | Fewer reads assigned to microbial taxa at lower taxonomic levels [7] | Insufficient data for reliable classification beyond phylum or family level |

Root Cause Analysis: Why Low Depth Masks True Diversity

Index Misassignment (Index Hopping): This phenomenon occurs when indexes are incorrectly assigned during multiplexed sequencing, causing reads to be attributed to the wrong sample. While these misassigned reads represent a small fraction (0.2-6% on Illumina platforms), they can generate false rare taxa that significantly distort diversity assessments in low-depth sequencing [6].

Stochastic Sampling Effects: In complex microbial communities with a "long tail" of rare species, low sequencing depth means that rare taxa may be detected only by chance in some replicates but not others. This leads to significant batch effects and inconsistent results across technical replicates [6].

Insufficient Sampling of True Diversity: Each sequencing read represents a random sample from the total DNA in your specimen. With limited reads, the probability of sampling DNA from genuinely rare organisms decreases dramatically, causing them to fall below the detection threshold [7].

Solution Framework: Strategies for Optimal Depth Selection

Table: Recommended Sequencing Depths for Different Sample Types

| Sample Type | Recommended Depth | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Fecal Samples | ~59 million reads (D0.5) | Suitable for describing core microbiome and resistome [7] | Relative abundance of phyla remained constant; fewer taxa discovered at lower depths [7] |

| Human Gut Microbiome | 3 million reads (shallow shotgun) | Cost-effective for species-level resolution in large cohort studies [8] | Balances cost with species/strain-level resolution for high microbial content samples [8] |

| Complex Environmental Samples | >60 million reads | Captures greater diversity of low-abundance organisms | Number of taxa identified increases significantly with depth [7] |

| Skin Microbiome (High Host DNA) | Consider targeted enrichment | Host DNA dominates; standard depth insufficient for rare microbes | Shallow shotgun less sensitive for samples with high non-microbial content [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My sequencing depth seems sufficient based on initial quality metrics, but I'm still missing known rare taxa in mock communities. What could be wrong?

A1: The issue may be index misassignment rather than raw sequencing depth. This phenomenon, where indexes are incorrectly assigned during multiplexed sequencing, creates false rare taxa while obscuring real ones. Studies comparing sequencing platforms have found significant differences in false positive rates (0.08% vs. 5.68%) between platforms [6]. To address this:

- Include negative controls and technical replicates in your sequencing run

- Consider platforms with lower demonstrated index misassignment rates

- Use bioinformatic tools specifically designed to identify and remove potential cross-contaminants

Q2: How does sequencing depth specifically affect the detection of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in metagenomic studies?

A2: Deeper sequencing significantly improves ARG detection sensitivity. Research on bovine fecal samples showed that the number of reads assigned to antimicrobial resistance genes increased substantially with sequencing depth [7]. While relative proportions of major ARG classes may remain fairly constant across depths, the absolute detection of less abundant resistance genes requires sufficient depth to overcome the background of more abundant genetic material.

Q3: What is the relationship between sequencing depth and the ability to identify keystone species in microbial networks?

A3: Inadequate depth can completely alter your interpretation of keystone species. False positive or false negative rare taxa detection leads to biased community assembly mechanisms and the identification of fake keystone species in correlation networks [6]. Since rare taxa can play disproportionate ecological roles, missing them due to low depth fundamentally changes your understanding of community dynamics and the identification of which species are truly crucial for network integrity.

Q4: For large cohort studies where deep sequencing of all samples is cost-prohibitive, what are the best alternatives?

A4: Shallow shotgun sequencing (approximately 3 million reads) provides an excellent balance between cost and data quality for large studies, particularly for high-microbial-content samples like gut microbiomes [8]. This approach offers better species-level resolution than 16S rRNA sequencing while maintaining cost-effectiveness. For samples with high host DNA (e.g., skin, blood), consider hybridization capture using targeted probes to enrich microbial sequences before sequencing [9].

Q5: How can I determine the optimal sequencing depth for my specific study system?

A5: Conduct a pilot study with a subset of samples sequenced at multiple depths. Research on bovine fecal samples demonstrated that while relative abundance of reads aligning to different phyla remained fairly constant regardless of depth, the number of reads assigned to antimicrobial classes and the detection of lower-abundance taxa increased significantly with depth [7]. Your optimal depth depends on your study goals—if seeking core community structure, lower depth may suffice; if characterizing rare taxa or ARGs, deeper sequencing is essential.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Optimal Sequencing Depth for Microbial Community Analysis

Principle: Systematically evaluate how increasing sequencing depth affects the detection of microbial taxa, particularly rare species, in your specific sample type.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality metagenomic DNA (extracted using standardized protocols)

- Library preparation kit (e.g., Novizan Universal Plus DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina)

- Quality control instruments (Qubit for DNA concentration, Fragment Analyzer for insert size)

- Illumina sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract DNA using methods optimized for your sample type (e.g., bead-beating for Gram-positive bacteria in fecal samples) [7].

- Library Preparation and Quality Control: Prepare sequencing libraries and quantify using q-PCR to ensure library effective concentration >3 nM [10].

- Sequencing Design: Sequence the same library at multiple depths (e.g., 26, 59, and 117 million reads) by adjusting the number of sequencing cycles [7].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw data through quality filtering and host read removal

- Classify reads using taxonomic profilers (Kraken, etc.)

- Calculate alpha and beta diversity metrics at each depth

- Compare the number of taxa identified at each taxonomic level

- Threshold Determination: Identify the point where additional sequencing yields diminishing returns in new taxa discovery.

Expected Results: Initially, new taxa discovery will increase rapidly with depth, then plateau. The optimal depth is just before this plateau for your specific research questions.

Protocol: Minimizing Index Misassignment in Multiplexed Sequencing

Principle: Reduce cross-sample contamination that creates false rare taxa through optimized library preparation and sequencing practices.

Materials and Reagents:

- Unique dual indexes (UDIs) with maximum sequence diversity

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase for library amplification

- Platform-specific sequencing reagents

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Include negative controls (extraction blanks) and technical replicates across sequencing lanes.

- Library Preparation: Use UDIs instead of single indexes to minimize misassignment.

- Pooling Strategy: Avoid overloading sequencing lanes; follow manufacturer recommendations for optimal cluster density.

- Platform Selection: If studying rare biosphere is primary goal, consider platforms with demonstrated lower index misassignment rates (0.0001-0.0004% vs. 0.2-6%) [6].

- Bioinformatic Filtering: Implement strict filtering based on negative controls to remove contaminants.

Expected Results: Significant reduction in false positive rare taxa and improved reproducibility across technical replicates.

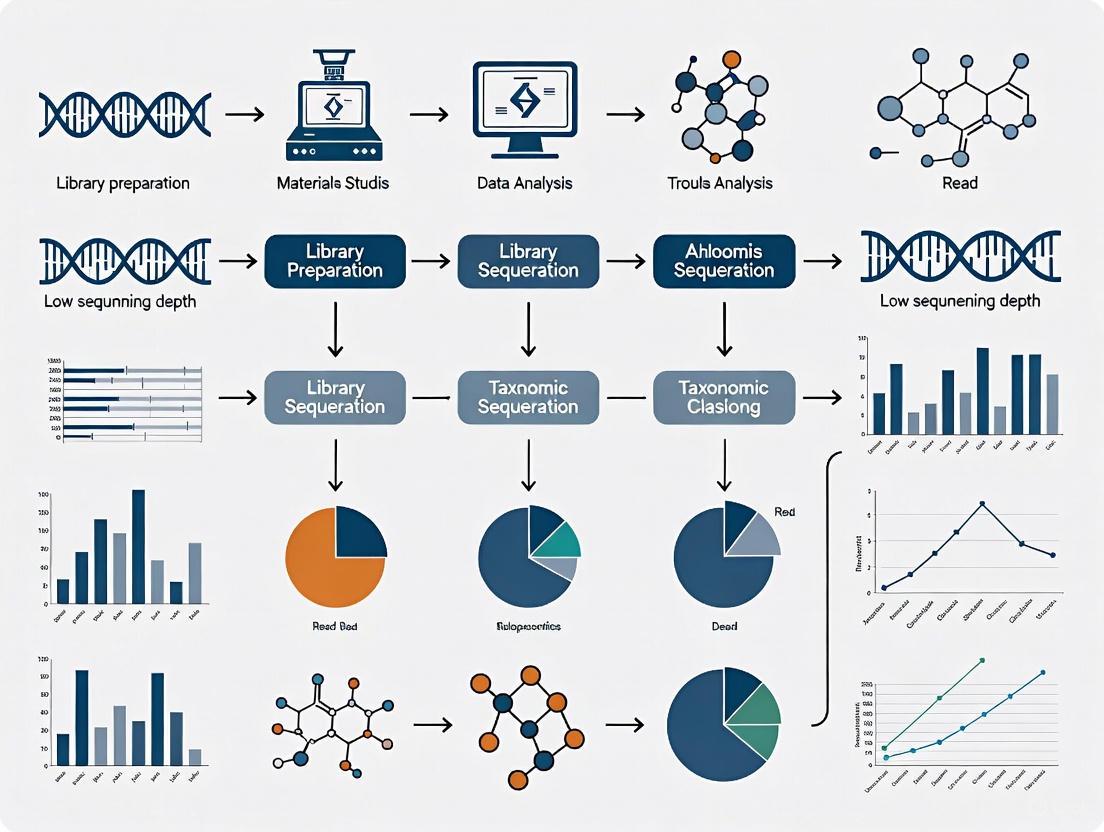

Workflow Visualization: From Sample to Analysis

Diagram: Microbial Analysis Workflow and Critical Decision Points. This workflow highlights how decisions at key points (blue diamonds) can lead to consequences (red boxes) that ultimately affect result interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Optimized Metagenomic Sequencing

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bead-beating Matrix | Enhanced cell lysis for Gram-positive bacteria | Critical for representative DNA extraction from diverse communities; improves yield from tough cells | [7] |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Sample multiplexing with minimal misassignment | Reduces index hopping compared to single indexes; essential for rare biosphere studies | [6] |

| Hybridization Capture Probes | Targeted enrichment of microbial sequences | myBaits system enables ~100-fold enrichment; ideal for host-dominated samples | [9] |

| DNA Quality Control Kits | Assess DNA purity and quantity | Fluorometric methods (Qubit) preferred over UV spectrophotometry for accurate quantification | [11] |

| Host DNA Removal Kits | Deplete host genetic material | Critical for samples with high host:microbe ratio (skin, blood); improves microbial signal | [7] |

| Mock Community Controls | Method validation and calibration | ZymoBIOMICS or customized communities essential for assessing sensitivity and specificity | [6] |

Successfully characterizing microbial diversity, particularly the rare biosphere, requires careful consideration of sequencing depth throughout your experimental design. The most critical recommendations include: (1) conducting pilot studies to determine optimal depth for your specific sample type and research questions; (2) implementing controls and replicates to identify technical artifacts; (3) selecting appropriate sequencing platforms and methods based on your focus on rare taxa; and (4) applying bioinformatic filters judiciously to remove false positives without eliminating genuine rare organisms. By addressing the challenge of sequencing depth directly, researchers can unmask the true diversity of microbial communities and gain more accurate insights into the ecological and functional roles of the rare biosphere.

Core Concepts: Sequencing Depth and Resistome Analysis

Why is sequencing depth particularly critical for resistome analysis compared to taxonomic profiling?

Taxonomic profiling stabilizes at much lower sequencing depths, while comprehensive resistome analysis requires significantly deeper sequencing. The richness of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) gene families and their allelic variants are particularly depth-dependent.

- Taxonomic Profiling Stability: Achieves less than 1% dissimilarity to the full profile with only 1 million reads per sample [4].

- AMR Gene Family Richness: Requires at least 80 million reads per sample for the number of different AMR gene families to stabilize [4] [12].

- AMR Allelic Diversity: Full allelic diversity may not be captured even at 200 million reads per sample, indicating that discovering rare variants demands extreme depth [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs & Solutions

FAQ 1: My study involves diverse environmental samples. How do I determine the minimum sequencing depth needed?

The required depth depends on your sample type due to inherent differences in microbial and resistance gene diversity. The table below summarizes findings from a key study that sequenced different sample types to a high depth (~200 million reads) [4].

Table 1: Minimum Sequencing Depth Requirements by Sample Type for AMR Analysis

| Sample Type | Sequencing Depth for AMR Gene Family Richness (d0.95)* | Sequencing Depth for AMR Allelic Variants (d0.95)* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effluent | 72 - 127 million reads | ~193 million reads | Very high allelic diversity; richness may not plateau even at 200M reads. |

| Pig Caeca | 72 - 127 million reads | Information Not Specified | High gene family richness. |

| River Sediment | Very low AMR reads | Very low AMR reads | AMR gene content was too low for depth analysis in this study. |

| Human Gut (Typical) | ~3 million reads (shallow shotgun) | Not recommended for allelic diversity | Sufficient for species-level taxonomy and core functional profiling [8]. |

*d0.95 = Depth required to achieve 95% of the estimated total richness.

Recommendation: For complex environments like effluent or soil, pilot studies with deep sequencing are recommended to establish depth requirements for your specific samples [4] [12].

FAQ 2: I have already sequenced my samples at a shallow depth (e.g., 3-5 million reads). Can I salvage the data for resistome analysis?

Yes, but with major caveats regarding the scope of your conclusions. Shallow shotgun sequencing (~3 million reads) is a valid cost-effective method for specific applications [8].

What Shallow Depth is Good For:

Limitations of Shallow Depth Data:

- Poor recovery of AMR gene richness: You will have missed rare AMR gene families [4].

- Incomplete allelic diversity: The full scope of allelic variants, which can have profound functional implications, will be underrepresented [4] [13].

- Inability to perform deep genetic analysis: Strain-level variation, single nucleotide variant (SNV) calling, and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) require deep sequencing [12].

Solution: Clearly frame your research findings to reflect the limitations of your sequencing depth. Use phrases like "detection of abundant AMR genes" rather than "comprehensive resistome characterization."

FAQ 3: Are there wet-lab and bioinformatic methods to improve resistome analysis without the cost of ultra-deep sequencing for all samples?

Yes, alternative strategies can enhance sensitivity and specificity.

1. Wet-Lab Solution: Targeted Sequence Capture This method uses biotin-labeled RNA probes to hybridize and enrich DNA libraries for sequences of interest before sequencing.

- Principle: Design probes complementary to a curated database of AMR genes, which allows you to "pull out" these targets from a complex metagenomic background [14] [15].

- Benefit: Dramatically increases the on-target reads for AMR genes, enabling their detection even when they represent <0.1% of the metagenome [14]. One study reported a 300-fold increase in unequivocally mapped reads compared to standard shotgun sequencing [15].

- Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for a targeted capture experiment like the ResCap method [15].

2. Bioinformatic Solution: Optimized Pipelines and Databases Using specialized, well-curated tools can improve the accuracy and depth of analysis from your existing data.

- Use Updated and Comprehensive Databases: Tools like

sraXcan integrate multiple databases (CARD, ARGminer, BacMet) for a more extensive homology search [16]. - Leverage Assembly-Based Methods: While computationally expensive, assembly-based tools can identify novel ARGs and provide genomic context, which is lost in read-based mapping [16].

- Normalization is Key: When quantifying AMR abundance, normalize read counts by gene length. For cross-sample comparison, consider using an exogenous spike-in (e.g., Thermus thermophilus DNA) to estimate absolute abundance [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Resistome Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive AMR Databases | Curated collections of reference sequences for identifying AMR genes and variants. | CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) [4] [16], ResFinder [15], ARG-ANNOT [15]. |

| Targeted Capture Probe Panels | Pre-designed sets of probes for enriching AMR genes from metagenomic libraries prior to sequencing. | ResCap [15], Custom panels (e.g., via Arbor Biosciences myBaits) [14]. |

| Exogenous Control DNA | Spike-in control for normalizing gene abundances to allow absolute quantification and cross-sample comparison. | Thermus thermophilus DNA [4]. |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kits | Ensure minimal bias and high yield during DNA extraction, which is critical for downstream representativeness. | Kits optimized by sample type (e.g., Metahit protocol for stool) [15]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software for processing sequencing data, mapping reads to AMR databases, and performing normalization and statistical analysis. | ResPipe [4], sraX [16], ARIBA [16]. |

| High-Quality Reference Genomes | Used for alignment, variant calling, and understanding the genomic context of detected AMR genes. | Isolates sequenced with hybrid methods (e.g., Illumina + Oxford Nanopore) [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't I resolve strains or call SNPs even when my species-level analysis looks good? Species-level analysis often masks significant genetic diversity. While two strains may share over 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI), this only applies to the portions of the genome they have in common. A single species can have a pangenome containing tens of thousands of genes, but an individual strain may possess only a fraction of these, leading to vast differences in key functional characteristics like virulence or drug resistance. When sequencing depth is low, the reads are insufficient to cover these variable regions or detect single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that distinguish one strain from another [17].

2. My sequencing run had good yield; why is my strain-level resolution still poor? Total sequencing yield can be misleading. Strain-level resolution requires sufficient coverage (depth) across the entire genome of each strain present. In a metagenomic sample with multiple co-existing strains, the coverage for any single strain can be drastically lower than the total sequencing depth. Tools for de novo strain reconstruction, for instance, often require 50-100x coverage per strain for accurate results. If your sample contains multiple highly similar strains (with Mash distances as low as 0.0004), the effective coverage for distinguishing them is even lower, making SNP calling unreliable [18] [19].

3. How does sample contamination affect strain-level analysis? In low-biomass samples, contamination is a critical concern. Contaminant DNA can constitute a large proportion of your sequence data, effectively diluting the signal from your target organisms. This leads to reduced coverage for genuine strains and can cause false positives by introducing sequences that look like novel strains. Contamination can originate from reagents, sampling equipment, or the lab environment, and its impact is disproportionate in studies aiming for high-resolution strain detection [20].

4. Are some sequencing technologies better for strain-level SNP calling than others? While short-read technologies (like Illumina) are widely used, their read length can be a limitation. Longer reads are better for spanning repetitive or variable regions, which is often crucial for separating strains. Sanger sequencing, with its longer read length and high accuracy, can improve assembly outcomes but is cost-prohibitive for large metagenomic studies. The error profiles of different platforms also matter; for example, homopolymer errors in 454/Roche pyrosequencing can cause frameshifts that obscure true SNPs [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Sequencing Depth for Strain Resolution

Problem: Inability to call SNPs or distinguish between highly similar strains in a metagenomic sample.

Step 1: Diagnose the Root Cause

- Check Coverage and Complexity: Use tools like

BBMaporCheckMto assess the coverage depth and completeness of your metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). A CheckM completeness score below 90% often indicates an inadequate dataset for confident strain-level analysis [22]. - Identify Contamination: Use tools like

KrakenorDecontaMinerto screen for and quantify contaminant sequences. A high percentage of reads classified as common contaminants (e.g., human, skin flora) signals a problem [20]. - Assess Strain Diversity: If possible, use a low-resolution strain tool (e.g.,

StrainGE,StrainEst) to estimate the number and similarity of strains present. Co-existing strains with a Mash distance < 0.005 are exceptionally challenging to resolve [18].

Step 2: Apply Corrective Measures in Wet-Lab Procedures

- Optimize DNA Extraction: For low-biomass samples, use extraction protocols designed to maximize yield while minimizing contamination. Include multiple negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, swabs of the air) to track contamination sources [20].

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Based on your initial coverage assessment, you may need to sequence more deeply. As a rule of thumb, strain-resolving analyses require significantly higher depth than species-level profiling.

- Consider Long-Read Sequencing: If the budget allows, supplement your short-read data with long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore). Long reads can bridge strain-specific structural variations and improve assembly, providing a better scaffold for SNP calling [19].

Step 3: Optimize Computational Analysis

- Select the Right Tool: Standard species-level classifiers (

Kraken,MetaPhlAn2) are not suitable. Use tools specifically designed for high-resolution strain-level analysis, such asStrainScan, which employs a hierarchical k-mer indexing structure to distinguish highly similar strains [18]. - Use Customized Reference Databases: When targeting specific bacteria, provide a customized, high-quality set of reference genomes for that species to the analysis tool. This increases the chance of matching the strains present in your sample [18].

- Leverage Metagenomic Assembly: For high-coverage samples, use assembly-based methods (

EVORhA,DESMAN) to reconstruct strain genomes de novo. These methods can resolve full strain genomes but require high coverage (50-100x per strain) [19].

Performance Comparison of Strain-Level Analysis Tools

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of various computational approaches for strain-level analysis, highlighting their different strengths and data requirements.

TABLE 1: Strain-Level Microbial Detection Tools

| Tool / Method | Category | Key Principle | Key Strength | Key Limitation / Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StrainScan [18] | K-mer based | Hierarchical k-mer indexing (Cluster Search Tree) | High resolution for distinguishing highly similar strains; improved F1 score. | Requires a predefined set of reference strain genomes. |

| EVORhA [19] | Assembly-based | Local haplotype assembly and frequency-based merging. | Can reconstruct complete strain genomes; high accuracy. | Requires extremely high coverage (50-100x per strain). |

| DESMAN [19] | Assembly-based | Uses differential coverage of core and accessory genes. | Resolves strains and estimates relative abundance without a reference. | Requires a group of high-quality Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). |

| Pathoscope2 [18] | Alignment-based | Bayesian reassignment of ambiguously mapped reads. | Effectively identifies dominant strains in a mixture. | Computationally expensive with large reference databases. |

| Krakenuniq [18] | K-mer based | Uses k-mer counts for classification and abundance estimation. | Good for species-level and some strain-level identification. | Low resolution when reference strains share high similarity. |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Diagnosing Strain-Resolution Failure

This protocol provides a step-by-step method to systematically diagnose the reasons behind failed strain-level SNP calling, integrating both bioinformatic and experimental checks.

Title: Diagnostic Workflow for Strain-Resolution Failure

1. Initial Quality Control and Coverage Assessment

- Input: Filtered metagenomic sequencing reads (FASTQ format).

- Procedure:

- Assemble reads into contigs using a metagenomic assembler (e.g., MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes).

- Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using a tool like MetaBAT2.

- Run

CheckMorCheckM2on the MAGs to assess completeness and contamination.

- Interpretation: A MAG with a CheckM completeness score below 90% is unlikely to provide sufficient data for strain-level resolution [22]. Low coverage across the target genome (<20x) is a primary indicator of insufficient sequencing depth.

2. Contamination Screening and Quantification

- Input: Raw or filtered sequencing reads (FASTQ format).

- Procedure:

- Classify all reads taxonomically using

Kraken2with a standard database. - Analyze the output to determine the percentage of reads classified as your target organism versus common contaminants (e.g., human, E. coli lab strain).

- Compare the taxonomic profile of your sample with your negative control samples.

- Classify all reads taxonomically using

- Interpretation: A high proportion of contaminant reads (>5%) significantly dilutes your signal and is a likely cause of failure, especially in low-biomass samples [20].

3. Low-Resolution Strain Profiling

- Input: Sequencing reads and a database of reference genomes for your target species.

- Procedure:

- Run a clustering-based strain tool like

StrainGEorStrainEston your data. - These tools will report strains at a lower resolution (e.g., clustering strains with >99.4% ANI).

- If a cluster is identified, calculate the Mash distance between the reference strains within that cluster.

- Run a clustering-based strain tool like

- Interpretation: The presence of a cluster containing multiple reference strains with a very low Mash distance (e.g., <0.005) indicates a challenging scenario of highly similar co-existing strains, explaining the failure of SNP callers [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for Strain-Resolving Studies

TABLE 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Purpose | Considerations for Strain-Level Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Free Collection Swabs/Tubes | To collect samples without introducing contaminant DNA. | Critical for low-biomass samples (e.g., tissue, water). Pre-sterilized and certified DNA-free. [20] |

| DNA Degrading Solution | To remove trace DNA from equipment and surfaces. | Used for decontaminating reusable tools. More effective than ethanol or autoclaving alone. [20] |

| High-Yield DNA Extraction Kit | To maximize recovery of microbial DNA from the sample. | Select kits benchmarked for your sample type (e.g., soil, stool) to minimize bias. [21] |

| Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) Kit | To amplify femtograms of DNA to micrograms for sequencing. | Use with caution as it can introduce bias and chimeras; essential for single-cell genomics. [21] |

| Negative Control Kits | To identify contaminating DNA from reagents and the lab environment. | Should include "blank" extraction controls and sampling controls processed alongside all samples. [20] |

| Strain-Specific Reference Genomes | Curated genomic sequences used as a database for strain identification. | Quality and diversity of the reference database directly impact the resolution of tools like StrainScan. [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary consequences of low sequencing depth on MAG quality? Low sequencing depth directly leads to fragmented assemblies and poor genome recovery [23]. Insufficient reads result in short contigs during assembly, which binning algorithms struggle to group correctly into MAGs. This fragmentation causes lower genome completeness and an increased rate of missing genes, even for high-abundance microbial populations [24]. Furthermore, it reduces the ability to distinguish between closely related microbial strains, as the coverage information used for binning becomes less reliable.

Q2: My MAGs have high completeness scores but are missing known genes from the population. Why? This is a documented discrepancy. A study comparing pathogenic E. coli isolates to their corresponding MAGs found that MAGs with completeness estimates near 95% captured only 77% of the population's core genes and 50% of its variable genes, on average [24]. Standard quality metrics (like CheckM) rely on a small set of universal single-copy genes, which may not represent the entire genome. This indicates that gene content, especially variable genes, is often worse than estimated completeness suggests [24].

Q3: How does high host DNA contamination in a sample affect MAG recovery? Samples with high host DNA (e.g., >90%) drastically reduce the proportion of microbial sequencing reads. This leads to a significant loss of sensitivity in detecting low-abundance microbial species and results in fewer recovered MAGs [25] [26]. To acquire meaningful microbial data from such samples, a much higher total sequencing depth is required to achieve sufficient coverage of the microbial genomes, making studies more costly and computationally intensive.

Q4: Can the choice of binning pipeline influence the recovery of genomes from complex communities? Yes, significantly. Different binning pipelines exhibit variable performance. A 2024 simulation study evaluating three common pipelines found that the DAS Tool (DT) pipeline showed the most accurate results (~92% true positives), outperforming others in the same test [23]. The study also highlighted that some pipelines (like the 8K pipeline) recover a higher number of total MAGs but with a lower accuracy rate, meaning more bins do not necessarily reflect the actual community composition [23].

Q5: What is a major limitation of using mock communities to validate MAG recovery? Traditional mock communities are often constructed from a single genome per organism. They do not capture the full scope of intrapopulation gene diversity and strain heterogeneity found in natural populations [24]. Consequently, a pipeline's performance on a mock dataset may not accurately predict its performance on a real, more complex environmental sample where multiple closely related strains with variable gene content are present.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Effects of Low Sequencing Depth

Problem: Assembled MAGs are highly fragmented (low N50, high contig count), have low estimated completeness, and fail to recover key genes of interest.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of insufficient sequencing depth. Check the following:

- Raw Read Coverage: Calculate the average coverage of your target population(s) from the metagenomic reads. For reliable MAG recovery, a minimum of 10x coverage is often required, with higher depths (e.g., 20-30x) needed for more complete genomes [24] [27].

- Community Profiling: Use a tool like MetaPhlAn2 to profile community composition [25]. If low-abundance taxa are missing from the profile, it indicates they are under-sequenced.

Solutions:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Sequence the library to a greater depth. Simulation studies show that increasing depth from 10 million to 60 million reads can significantly boost the number of recovered MAGs [23].

- Employ Co-assembly: If you have multiple related samples (e.g., technical or biological replicates), a co-assembly strategy can increase the effective read depth, leading to more robust assemblies and better MAGs [28].

- Use Longer Reads: If possible, leverage long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) or hybrid assembly approaches. These can span repetitive regions and produce much longer contigs, directly combating fragmentation [29] [30].

Guide: Improving MAG Recovery from Host-Dominated Samples

Problem: Samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) or oropharyngeal swabs yield a very low percentage of microbial reads, hindering MAG reconstruction.

Diagnosis: The sample has a high host-to-microbe DNA ratio. Confirm this by aligning a subset of your reads to the host genome (e.g., using KneadData/Bowtie2) [25]. A microbial read ratio below 1% is a clear indicator [26].

Solutions:

- Apply Host Depletion Methods: Implement a pre-sequencing host DNA depletion protocol. A 2025 benchmarking study compared seven methods on respiratory samples [26]. The performance of these methods in increasing microbial reads is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance of Host DNA Depletion Methods for Respiratory Samples (Adapted from [26])

| Method Name | Category | Key Principle | Performance in BALF (Fold Increase in Microbial Reads) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K_zym (HostZERO Kit) | Pre-extraction | Chemical & enzymatic host cell lysis & DNA degradation | 100.3x |

| S_ase | Pre-extraction | Saponin lysis & nuclease digestion | 55.8x |

| F_ase (New Method) | Pre-extraction | 10μm filtering & nuclease digestion | 65.6x |

| K_qia (QIAamp Kit) | Pre-extraction | Not specified in detail | 55.3x |

| O_ase | Pre-extraction | Osmotic lysis & nuclease digestion | 25.4x |

| R_ase | Pre-extraction | Nuclease digestion | 16.2x |

| O_pma | Pre-extraction | Osmotic lysis & PMA degradation | 2.5x |

- Increase Sequencing Depth Proactively: When working with host-dominated samples, plan for a much higher total sequencing output to ensure sufficient coverage of the microbial fraction after depletion [25].

Table 2: Impact of Sequencing Depth on MAG Recovery from Simulated Communities [23]

| Sequencing Depth (Millions of Reads) | Trend in MAG Recovery (across 8K, DT, and MM pipelines) |

|---|---|

| 10 million | Low number of MAGs recovered. |

| 30 million | Increasing trend in MAG recovery. |

| 60 million | Increasing trend in MAG recovery; MM pipeline peaks around this depth. |

| 120 million | 8K pipeline recovers more true positives at depths above 60M reads. |

| 180 million | Trend continues for the 8K pipeline. |

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of High Host DNA on Microbiome Profiling Sensitivity [25]

| Host DNA Percentage | Impact on Sensitivity of Detecting Microbial Species |

|---|---|

| 10% | Minimal impact on sensitivity. |

| 90% | Significant decrease in sensitivity for very low and low-abundance species. |

| 99% | Profiling becomes highly inaccurate and insensitive. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Host DNA Depletion using the F_ase Method for Respiratory Samples

This protocol is based on a method benchmarked in a 2025 study, which showed a balanced performance in increasing microbial reads while maintaining good bacterial DNA retention [26].

Principle: Microbial cells are separated from host cells and debris by filtration through a 10μm filter. The filtrate, enriched in microbial cells, is then treated with a nuclease to degrade free-floating host DNA.

Materials:

- Respiratory sample (e.g., BALF, OP swab in suspension)

- Sterile saline solution

- 10μm pore-size filters (e.g., cell strainers)

- Nuclease enzyme (e.g., Benzonase) and corresponding buffer

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Centrifuge

- DNA extraction kit (for microbial DNA)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the respiratory sample in a sterile saline solution.

- Filtration: Pass the homogenized sample through a 10μm filter. The filtrate contains the enriched microbial cells.

- Nuclease Treatment: a. Collect the filtrate in a fresh microcentrifuge tube. b. Add nuclease enzyme and its reaction buffer to the filtrate. c. Incubate at the recommended temperature and duration (e.g., 37°C for 1 hour) to degrade free DNA. d. Heat-inactivate the nuclease as per the manufacturer's instructions.

- DNA Extraction: Pellet the microbial cells by centrifugation. Proceed with DNA extraction from the pellet using a standard microbial DNA extraction kit.

- Quality Control: Quantify the total DNA and assess the host DNA depletion efficiency by qPCR targeting a host-specific gene (e.g., GAPDH) and a universal bacterial gene (e.g., 16S rRNA).

Protocol: Evaluating MAG Quality Against an Isolate Genome

This protocol provides a method for an independent assessment of MAG quality that goes beyond standard completeness/contamination metrics, as described in [24].

Principle: A MAG recovered from a metagenome is directly compared to a high-quality isolate genome obtained from the same sample. This allows for a true assessment of core and variable gene recovery.

Materials:

- Metagenomic sequencing data from a sample.

- Whole-genome sequencing data of an isolate from the same sample.

- Assembly software (e.g., MEGAHIT, SPAdes).

- Binning software (e.g., MaxBin, MetaBAT).

- Genome quality assessment tool (e.g., CheckM).

- Genome comparison tool (e.g., OrthoFinder, Roary, BLAST+).

Procedure:

- Generate the MAG: a. Assemble the metagenomic reads into contigs. b. Bin the contigs to recover the MAG representing the target organism. c. Assess the MAG's quality using CheckM to estimate completeness and contamination.

- Assemble the Isolate Genome: a. Assemble the isolate's sequencing reads into a reference genome.

- Compare Gene Content: a. Annotate both the MAG and the isolate genome to identify all protein-coding genes. b. Perform an all-vs-all BLAST of the genes from both genomes. c. Identify core genes (present in >90% of the population, i.e., in the isolate) and variable genes (shared by >10% but <90%). d. Calculate the percentage of the isolate's core and variable genes that were successfully captured by the MAG. The study in [24] found averages of 77% for core and 50% for variable genes, serving as a benchmark.

Visual Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for MAG Studies from Complex Samples

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit (K_zym) | Pre-extraction host DNA depletion. | Effectively removing host DNA from samples with very high host content (e.g., BALF), increasing microbial read yield over 100-fold [26]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (K_qia) | Pre-extraction host DNA depletion. | An alternative commercial kit for host DNA depletion, showing good performance in increasing microbial reads from oropharyngeal swabs [26]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Metagenomic library preparation. | Used for preparing sequencing libraries from normalized DNA, including metagenomic samples, for Illumina platforms [25]. |

| Microbial Mock Community B (BEI Resources) | Positive control for sequencing and analysis. | A defined mix of 20 bacterial genomic DNAs used to benchmark sequencing sensitivity, bioinformatics pipelines, and host depletion methods [25] [26]. |

| RNAlater / OMNIgene.GUT | Nucleic acid preservation. | Stabilizes microbial community DNA/RNA at the point of collection, preventing degradation and shifts in community structure before DNA extraction [29]. |

Strategic Approaches: From Wet-Lab Bench to Bioinformatic Pipelines

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is host DNA depletion critical for shotgun metagenomic sequencing of respiratory samples?

Host DNA depletion is crucial because samples like bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) can contain over 99.7% host DNA, drastically limiting the sequencing depth available for microbial reads [31]. Without depletion, the overwhelming amount of host DNA overshadows microbial signals, reducing the sensitivity for detecting pathogens [32] [26]. Effective host DNA depletion can increase microbial reads by more than 100-fold in BALF samples, transforming a dataset with minimal microbial information into one suitable for robust analysis [26].

FAQ 2: My microbial sequencing depth remains low after host DNA depletion. What are the primary factors to investigate?

Low microbial sequencing depth post-depletion can stem from several factors. systematically investigate the following, which are common troubleshooting points:

- Sample Type and Initial Biomass: The method's efficiency is highly dependent on the sample type. For instance, oropharyngeal (OP) swabs typically respond better to depletion than BALF due to their inherently higher bacterial load [26]. Check if the starting bacterial DNA is sufficient.

- Depletion Method Selection: Different methods have vastly different efficiencies. As shown in Table 1, some kits are significantly more effective than others. Ensure the selected method is optimal for your specific sample type.

- Cell-Free DNA Contamination: Pre-extraction methods that target intact cells will not remove cell-free microbial DNA. One study noted that ~69% of microbial DNA in BALF and ~80% in OP swabs was cell-free, which can be lost during these protocols, reducing the final yield [26].

- Technical Failures: Some methods, particularly lyPMA (osmotic lysis with PMA) and MolYsis, have been reported to have higher rates of library preparation failure, which would directly result in low output. Always check library quality post-preparation [31].

FAQ 3: How does host DNA depletion impact the representation of the microbial community?

Most studies indicate that while host depletion efficiently removes human DNA, it can introduce biases:

- General Composition: Overall bacterial community composition is often reported to be similar before and after depletion [32].

- Specific Taxa Loss: Some methods can cause a significant reduction in the biomass of certain commensals and pathogens, such as Prevotella spp. and Mycoplasma pneumoniae [26].

- Varying Bacterial Retention: Different methods result in different bacterial DNA retention rates. For example, nuclease digestion (Rase) and the QIAamp kit (Kqia) showed the highest bacterial retention rates in OP swabs (median ~20%), while other methods were more aggressive and led to greater loss [26]. It is critical to validate the method for your microbes of interest, ideally using a mock microbial community.

FAQ 4: What is a sufficient sequencing depth for metagenomic studies after host depletion?

The required depth depends on your research goal. The following table summarizes recommendations from recent studies:

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depths for Metagenomic Studies

| Research Goal | Recommended Minimum Depth | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenome-Wide Association Studies (MWAS) | 15 million reads | Provides stable species richness (changing rate ≤5%) and reliable species composition (ICC > 0.75) [33]. |

| Strain-Level SNP Analysis | Ultra-deep sequencing (>> standard depth) | Shallow sequencing is "incapable of supporting systematic metagenomic SNP discovery." Ultra-deep sequencing is required to detect functionally important SNPs reliably [5]. |

| Rapid Clinical Diagnosis | Low-depth sequencing (<1 million reads) | When coupled with efficient host depletion and a streamlined workflow, this can be sufficient for detecting pathogens at physiological levels [34]. |

Technical Performance Data of Common Host Depletion Methods

The following table consolidates quantitative performance data from recent benchmarking studies to aid in method selection. Note that performance is sample-dependent.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Methods [32] [26] [31]

| Method (Category) | Key Principle | Host Depletion Efficiency (Fold Reduction) | Microbial Read Increase (Fold vs. Control) | Key Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saponin + Nuclease (S_ase) | Pre-extraction: Lyses human cells with saponin, digests DNA with nuclease. | BALF: ~10,000-fold [26] | BALF: 55.8x [26] | High efficiency. Requires optimization of saponin concentration. |

| HostZERO (K_zym) | Pre-extraction: Selective lysis and digestion. | BALF: ~10,000-fold [26]; Tissue: 57x (18S/16S ratio) [32] | BALF: 100.3x [26] | Very high host depletion. Can have high bacterial DNA loss and library prep failure risk [26] [31]. |

| QIAamp Microbiome Kit (K_qia) | Pre-extraction: Selective lysis and enzymatic digestion. | Tissue: 32x (18S/16S ratio) [32] | BALF: 55.3x [26] | Good host depletion and high bacterial retention. |

| Benzonase Treatment | Pre-extraction: Enzyme-based digestion. | Effective on frozen BALF, reduces host DNA to low pg/µL levels [31]. | Significantly increases final non-host reads [31]. | Robust performance on previously frozen non-cryopreserved samples [31]. |

| Filtration + Nuclease (F_ase) | Pre-extraction: Filters microbial cells, digests free DNA. | Moderate to High [26] | BALF: 65.6x [26] | Balanced performance with less taxonomic bias [26]. |

| NEB Microbiome Enrichment | Post-extraction: Binds methylated host DNA. | Low in respiratory samples [26]. | Low [26] | Easy workflow. Inefficient for respiratory samples and other types [26]. |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

Use the following diagram to guide your selection and troubleshooting of a host DNA depletion method. The process begins with sample characterization and leads to a method choice optimized for your specific goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and kits commonly used in host DNA depletion protocols, as featured in the cited research.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Host DNA Depletion Workflows

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Principle | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Molzym Ultra-Deep Microbiome Prep | Pre-extraction: Selective lysis of human cells and enzymatic degradation of released DNA. | Evaluated on diabetic foot infection tissue samples [32]. |

| Zymo HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Pre-extraction: Selective lysis of human cells and digestion of host DNA. | Efficient host depletion in BALF and tissue samples [32] [26]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Pre-extraction: Selective lysis followed by enzymatic digestion of host DNA. | Effective enrichment of bacterial DNA from tissue and respiratory samples [32] [26]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Post-extraction: Captures methylated host DNA, leaving microbial DNA in solution. | Less effective for respiratory samples [32] [26]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Viability dye: Penetrates compromised membranes of dead cells, cross-linking DNA upon light exposure. | Used in osmotic lysis (lyPMA) protocols to remove free host DNA and indicate viable microbes [26] [31] [35]. |

| Benzonase Endonuclease | Enzyme-based: Digests both host and free DNA in samples. | Effective host depletion for frozen respiratory samples (BAL, sputum) [31]. |

| ArcticZymes Nucleases (e.g., M-SAN HQ) | Enzyme-based: Magnetic bead-immobilized or free nucleases to deplete host DNA under various salt conditions. | Used in rapid clinical mNGS workflows for plasma and respiratory samples [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between short-read and long-read sequencing? Short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina, Element Biosciences AVITI) generates massive volumes of data from DNA fragments that are typically a few hundred base pairs long. These technologies are known for high per-base accuracy (often exceeding Q40) and low cost per base, making them the workhorse for many applications [37] [38] [39]. Long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore Technologies), in contrast, sequences DNA fragments that are thousands to hundreds of thousands of base pairs long in a single read. This allows them to span repetitive regions and resolve complex genomic structures without the need for assembly from fragmented pieces [37] [39].

2. How does sequencing depth interact with the choice of technology for metagenomic studies? Sequencing depth requirements are critically influenced by your sample type and research question. In metagenomic samples with high levels of host DNA (e.g., >90%), a much greater sequencing depth is required to obtain sufficient microbial reads for a meaningful analysis [40]. Furthermore, the required depth depends on what you are looking for: profiling taxonomic composition may be stable at around 1 million reads, but recovering the full richness of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene families can require at least 80 million reads, with even deeper sequencing needed to discover all allelic variants [4].

3. My metagenomic samples have high host DNA contamination. What can I do? Samples like saliva or tissue biopsies often contain over 90% host DNA, which can waste sequencing resources and obscure microbial signals [40]. Wet-lab and bioinformatics solutions are available:

- Wet-lab depletion kits: Use commercial kits to remove host (e.g., human) DNA before library preparation.

- Bioinformatics decontamination: Employ tools like CLEAN [41] or KneadData [40] to computationally identify and remove reads that align to the host genome after sequencing. Tools like QC-Blind can even perform this without a reference genome for the contaminant, using marker genes of the target species instead [42].

4. Can I combine long-read and short-read sequencing in a single study? Yes, this is a powerful strategy to leverage the strengths of both. You can use the high accuracy and low cost of short-read data for confident SNP and mutation calling, while layering long-read data to resolve complex structural variations and phase haplotypes. This hybrid approach is particularly beneficial for de novo genome assembly and studying rare diseases [38].

5. Have the historical drawbacks of long-read sequencing been overcome? Significant progress has been made. The high error rates historically associated with long-read technologies have been drastically reduced. PacBio's HiFi sequencing method now delivers accuracy exceeding 99.9% (Q30), on par with short-read technologies [37] [38]. While the cost of long-read sequencing was once prohibitive for large studies, platforms like the PacBio Revio have reduced the cost of a human genome to under $1,000, making it more accessible for larger-scale projects [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete or Biased Metagenomic Profiling

Issue: Your sequencing data fails to capture the full taxonomic or functional diversity of your sample, especially low-abundance species or complex gene variants.

Solution:

- Re-assess Required Sequencing Depth:

- Cause: Inadequate sequencing depth, particularly in samples with high host DNA or high microbial diversity, leads to incomplete profiling [4] [40].

- Fix: Conduct a pilot study or use rarefaction analysis on existing data to determine the depth at which diversity metrics plateau. For AMR gene discovery in complex environments, plan for depths of 80-200 million reads or more [4]. The table below summarizes findings from key studies.

| Application / Sample Type | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Key Findings from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Profiling (Mock community) | ~1 million reads | Achieved <1% dissimilarity to the full taxonomic composition [4]. |

| AMR Gene Family Richness (Effluent, Pig Caeca) | ≥80 million reads | Required to recover 95% of estimated AMR gene family richness (d0.95) [4]. |

| AMR Allelic Variant Discovery (Effluent) | ≥200 million reads | Full allelic diversity was still being discovered at this depth [4]. |

| Samples with High (90%) Host DNA | High depth required; >10 million reads fixed | At a fixed depth of 10M reads, profiling becomes inaccurate as host DNA increases. Deeper sequencing is crucial for sensitivity [40]. |

- Switch to or Incorporate Long-Read Sequencing:

- Cause: Short-read technologies struggle with repetitive genomic regions and cannot resolve long-range contiguity, leading to fragmented assemblies and missed structural variants [37] [38].

- Fix: For applications like de novo genome assembly, resolving complex structural variations, or phasing haplotypes, use PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore sequencing. The long reads can span repetitive elements, resulting in more complete genomes and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [37] [39].

Problem: Contamination in Sequencing Data

Issue: Your datasets are contaminated with host DNA, laboratory contaminants, or control sequences (e.g., PhiX, Lambda phage DCS), leading to misinterpretation of results.

Solution:

- Implement a Rigorous Decontamination Pipeline:

- Cause: Contamination can occur during sample collection, library preparation, or from spike-in controls that are not removed before data analysis [41] [42].

- Fix: Use a reproducible decontamination tool like CLEAN [41]. This pipeline can remove host sequences, control spike-ins (e.g., Illumina's PhiX, Nanopore's DCS), and ribosomal RNA reads from both short- and long-read data in a single step.

Experimental Protocol: Decontaminating Sequencing Data with CLEAN

- Software: CLEAN (https://github.com/rki-mf1/clean) [41]

- Input: Single- or paired-end FASTQ files (from Illumina, ONT, or PacBio).

- Procedure:

- Installation: Install CLEAN via Docker, Singularity, or Conda. Ensure Nextflow is installed.

- Run Basic Decontamination: Execute a command to remove common contaminants and spike-ins.

nextflow run rki-mf1/clean --input './my_sequencing_data/*.fastq' - Custom Reference (Optional): To remove a specific contaminant (e.g., host genome), provide a custom FASTA file.

nextflow run rki-mf1/clean --input './my_data.fastq' --contamination_reference './host_genome.fna' - "Keep" List (Optional): To protect certain reads from being falsely removed (e.g., viral reads in a host background), use the

keepparameter. - Output: CLEAN produces clean FASTQ files, a set of identified contaminants, and a comprehensive MultiQC report summarizing the decontamination statistics [41].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points for choosing a sequencing technology and addressing common issues, integrating the solutions discussed above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and tools referenced in this guide for troubleshooting metagenomic sequencing studies.

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CLEAN Pipeline [41] | Decontamination of sequencing data. | Removes host DNA, spike-ins (PhiX, DCS), and rRNA from short- and long-read data. Ensures reproducible analysis. |

| KneadData [40] | Quality control and host decontamination for metagenomic data. | Integrates Trimmomatic for quality filtering and Bowtie2 for host read removal. Used in microbiome analysis pipelines. |

| QC-Blind [42] | Quality control and contamination screening without a reference genome. | Uses marker genes and read clustering to separate target species from contaminants when reference genomes are unavailable. |

| PacBio HiFi Reads [37] | Long-read sequencing with high accuracy. | Provides reads >10,000 bp with >99.9% accuracy (Q30). Ideal for resolving complex regions and accurate assembly. |

| ResPipe [4] | Processing and analysis of AMR genes in metagenomic data. | Open-source pipeline for inferring taxonomic and AMR gene content from shotgun metagenomic data. |

| Mock Microbial Community (BEI Resources) [40] | Benchmarking and validation of metagenomic workflows. | Composed of genomic DNA from 20 known bacterial species. Used to assess sensitivity, accuracy, and optimal sequencing depth. |

Implementing Rigorous Quality Control (QC) Pipelines to Salvage Data from Low-Quality Reads

Core Concepts: Sequencing Depth and Data Quality

What is the relationship between sequencing depth and the ability to detect rare microbial species or genes? Sequencing depth directly determines your ability to detect low-abundance members of a microbial community. Deeper sequencing (more reads per sample) increases the probability of capturing sequences from rare species or rare genes [12]. For instance, characterizing the full richness of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene families in complex environments like effluent required a depth of at least 80 million reads per sample, and additional allelic diversity was still being discovered at 200 million reads [4]. Another study found that a depth of approximately 59 million reads (D0.5) was suitable for robustly describing the microbiome and resistome in cattle fecal samples [7].

How does sequencing depth requirement vary with sample type and study goal? The required depth is not one-size-fits-all and depends heavily on your sample's complexity and your research question [12]. The table below summarizes key considerations:

| Factor | Consideration | Recommended Sequencing Depth (Reads/Sample) |

|---|---|---|

| Study Goal | Broad taxonomic & functional profiling [12] | ~0.5 - 5 million (Shallow shotgun) |

| Detection of rare taxa (<0.1% abundance) or strain-level variation [12] | >20 million (Deep shotgun) | |

| Comprehensive AMR gene richness [4] | >80 million (Deep shotgun) | |

| Sample Type | Low-diversity communities (e.g., skin) | Lower Depth |

| High-diversity communities (e.g., soil, sediment) | Higher Depth [4] [12] | |

| Host DNA Contamination | Samples with high host DNA (e.g., skin swabs with >90% human reads) | Higher Depth [12] |

What are the fundamental steps in a QC and data salvage pipeline? A robust pipeline involves pre-processing, cleaning, and validation. The following workflow outlines the key stages and decision points for processing raw sequencing data into high-quality, salvaged reads ready for analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My initial quality control report shows low overall read quality. What steps should I take?

- Problem Identification: Use a tool like FastQC to check for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [43].

- Root Causes & Corrective Actions:

- Degraded Nucleic Acids: Re-assess your DNA extraction method. Ensure proper sample preservation (immediate freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at -80°C) and use bead-beating to enhance lysis of Gram-positive bacteria [7].

- Enzyme Inhibition from Contaminants: Re-purify input DNA to remove inhibitors like phenol, EDTA, or salts. Check absorbance ratios (260/280 ~1.8, 260/230 >1.8) and use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) for accuracy [11].

- Adapter Contamination: Use trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences. This is crucial for libraries with small fragments [43].

FAQ 2: After cleaning my data, the mapping rate to reference genomes is still low. How can I troubleshoot this?

- Problem Identification: Check the alignment logs from your aligner (e.g., BWA, Bowtie2) for the percentage of unmapped reads.

- Root Causes & Corrective Actions:

- Incorrect Reference Genome: Ensure you are using the correct version of the reference genome (e.g., hg38) and that it has been properly indexed for your specific aligner [43].

- High Host DNA Contamination: For samples like skin swabs or tissue, a high percentage of reads may map to the host genome. Remove these host-derived reads prior to metagenomic analysis using a tool like BWA against the host reference genome [7].

- Presence of PhiX Control Contamination: Illumina sequencing runs often spike in PhiX174 bacteriophage DNA as a control. Map your demultiplexed reads to the PhiX genome and filter them out, as they can be a major contaminant in final datasets [7].

- High Proportion of Novel or Uncharacterized Microbes: In complex environmental samples, a large fraction of reads may not map to any known reference. Consider de novo assembly approaches to characterize these communities [44].

FAQ 3: My library yield is low after preparation. What are the common causes and fixes?

- Problem Identification: Final library concentration is below expectations when measured by fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) or qPCR [11].

- Root Causes & Corrective Actions:

- Inefficient Adapter Ligation: Titrate your adapter-to-insert molar ratio. Excess adapters promote adapter-dimer formation, while too few reduce yield. Ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions [11].

- Overly Aggressive Size Selection or Purification: Using an incorrect bead-to-sample ratio during clean-up can exclude desired fragments. Re-optimize bead-based cleanup parameters to minimize loss of target fragments [11].

- PCR Amplification Issues: Too many PCR cycles can introduce duplicates and bias, while enzyme inhibitors can cause failure. Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary and ensure your template is free of inhibitors [11].

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Experiments

Protocol 1: Read Trimming and Adapter Removal for Data Salvage

This protocol is designed to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences from raw sequencing reads.

- Quality Assessment: Run FastQC on raw FASTQ files to visualize per-base quality and identify adapter types [43].

- Tool Selection: Choose a trimming tool such as Trimmomatic (for a balance of speed and configurability) or Cutadapt.

- Execute Trimming (Example with Trimmomatic for paired-end reads):

- Command Structure:

- Parameter Explanation:

ILLUMINACLIP: Removes adapter sequences. Specify the adapter FASTA file, and set parameters for palindrome clip threshold, simple clip threshold, and minimum adapter length.LEADING/TRAILING: Remove low-quality bases from the start and end of reads.SLIDINGWINDOW: Scans the read with a window (e.g., 4 bases), cutting when the average quality in the window falls below a threshold (e.g., 15).MINLEN: Discards reads shorter than the specified length after trimming.

- Post-Processing QC: Run FastQC again on the trimmed output files (e.g.,

output_forward_paired.fq.gz) to confirm improved quality and removal of adapters [43].

Protocol 2: Host DNA Removal from Metagenomic Samples

This protocol reduces host-derived reads, enriching for microbial sequences and improving effective sequencing depth.

- Reference Preparation: Download the appropriate host reference genome (e.g., Bos taurus UMD_3.1.1 for cattle) and index it using your chosen aligner (e.g.,

bwa index) [7]. - Alignment to Host Genome: Map all quality-filtered reads to the host reference.

- Example BWA Command:

- Read Extraction: Filter the alignment file to keep only reads that did not map to the host genome.

- Using SAMtools:

- Validation: The resulting FASTQ file (

salvaged_non_host_reads.fq) is now enriched for microbial and other non-host sequences and is ready for metagenomic analysis [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Application in Metagenomic QC |

|---|---|---|

| Bead-beating Tubes | Ensures mechanical lysis of tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria), improving DNA yield and community representation [7]. | Sample Preparation & DNA Extraction |

| Guanidine Isothiocyanate | A denaturant that inactivates nucleases, preserving DNA integrity after cell lysis during extraction [7]. | Sample Preparation & DNA Extraction |

| Fluorometric Kits (e.g., Qubit) | Provides accurate quantification of double-stranded DNA, superior to UV absorbance for judging usable input material [11]. | Library Preparation QC |

| Size Selection Beads | Clean up fragmentation reactions and selectively isolate library fragments in the desired size range, removing adapter dimers [11]. | Library Purification |

| Thermus thermophilus DNA | An exogenous spike-in control that allows for normalisation of AMR gene counts, enabling more accurate cross-sample comparisons of gene abundance [4]. | Data Normalisation & Analysis |

| PhiX174 Control DNA | Serves as a run quality control for Illumina sequencers. Its known sequence helps with error rate estimation and base calling calibration [7]. | Sequencing Run QC |

A critical decision in metagenomic analysis is whether to use bioinformatic mapping to a reference genome or to perform de novo assembly. This guide provides clear criteria for selecting the appropriate method, especially when dealing with the common challenge of low sequencing depth.

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Bioinformatic Mapping?

Bioinformatic mapping, or reference-based alignment, involves aligning sequencing reads to a pre-existing reference genome sequence. It is a quicker method that works well for identifying single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small indels, and other variations compared to a known genomic structure [45].

What is De Novo Assembly?

De novo assembly is the process of reconstructing the original DNA sequence from short sequencing reads without the aid of a reference genome. It is essential for discovering novel genes, transcripts, and structural variations, but requires high-quality raw data and is computationally intensive [45].

Decision Framework: Mapping vs. Assembly

The table below summarizes the key factors to consider when choosing your analysis path.

Table 1: A Comparative Overview of Mapping and De Novo Assembly

| Factor | Bioinformatic Mapping | De Novo Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Ideal when a high-quality reference genome is available for the target organism(s). | Necessary for novel genomes, highly diverse communities, or studying structural variations [45]. |

| Sequencing Depth Requirements | Can be effective with lower or shallow sequencing depths (e.g., 2-5 million reads) [46]. | Requires very high sequencing depth and data quality to ensure sufficient coverage across the entire genome [45]. |

| Computational Demand | Relatively fast and less computationally intensive. | A slow process that demands significant computational infrastructure [45]. |

| Key Advantages |

|

|

| Key Limitations |

|

|

The following workflow provides a visual guide for selecting the appropriate analytical path based on your research goals and resources.

Troubleshooting Low Sequencing Depth

Low sequencing depth is a major constraint in metagenomic studies. The following questions address common problems and their solutions.

FAQ 1: My mapping results show a low properly paired rate. Is this due to low sequencing depth?