Revolutionizing Synthesis: How Machine Learning Accelerates Materials Discovery and Optimization

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in materials synthesis planning, a critical frontier for researchers and development professionals.

Revolutionizing Synthesis: How Machine Learning Accelerates Materials Discovery and Optimization

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in materials synthesis planning, a critical frontier for researchers and development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of ML as applied to materials science, detailing specific methodologies from predictive modeling to autonomous laboratories. The content provides a practical guide for troubleshooting common challenges like small datasets and algorithm selection, and offers a comparative analysis of model performance and validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest advances, this review serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging ML to reduce development cycles from decades to months, enabling the accelerated discovery and optimization of novel materials.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Machine Learning in Materials Synthesis

Core Machine Learning Paradigms

The application of machine learning (ML) in synthesis planning and materials science research represents a paradigm shift from traditional, often intuition-driven approaches to a data-driven, predictive science. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the overarching goal of creating intelligent systems, Machine Learning (ML) is the data-driven strategy for achieving this goal, and Deep Learning (DL) is a specific, powerful tactic within ML that uses multi-layered neural networks to learn features directly from raw data [1]. For researchers, this hierarchy enables a structured approach to selecting the appropriate computational tool for complex problems in drug development and materials informatics.

The ML landscape can be broadly categorized into three primary learning types, each with distinct mechanisms and applications relevant to scientific discovery [1]:

- Supervised Learning operates on labeled datasets, where the algorithm learns to map input data to known outputs. This is extensively used for classification (e.g., categorizing material crystal systems) and regression tasks (e.g., predicting compound properties or reaction yields).

- Unsupervised Learning finds hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in unlabeled data. Its applications include clustering similar molecular structures or reducing the dimensionality of complex spectral data for visualization and analysis.

- Reinforcement Learning trains an agent to make a sequence of decisions by interacting with an environment and receiving feedback through rewards. This is particularly suited for optimizing multi-step synthesis pathways or guiding autonomous experimentation platforms.

Table 1: Core Machine Learning Techniques and Their Applications in Materials Science

| ML Category | Key Algorithms | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest, XGBoost, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVM) [1] | Predicting material properties, classifying reaction outcomes, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [2] |

| Unsupervised Learning | k-Means, DBSCAN, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [1] | Identifying novel material clusters, analyzing high-throughput screening data, anomaly detection in experimental processes |

| Reinforcement Learning | Q-learning, Deep Q Networks (DQN) [1] | Autonomous optimization of synthesis parameters, inverse molecular design, robotic process control |

| Deep Learning | CNNs, RNNs (LSTM, GRU), Transformers [1] | Analyzing microscopy images, predicting molecular stability, generating novel molecular structures [3] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Supervised Learning Workflow for Property Prediction

This protocol details the steps for developing a supervised learning model to predict a target property (e.g., band gap, catalytic activity, solubility) from structured experimental data.

Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools:

- Python Programming Language: The core environment for data manipulation and model implementation [1].

- Scikit-learn Library: Provides implementations of Random Forest, SVM, and other standard algorithms for model training and evaluation [1].

- Core ML Tools: A Python package used to convert trained models from frameworks like Scikit-learn into the Core ML format (.mlmodel) for deployment and integration into applications [4] [5].

- Pandas & NumPy Libraries: Essential for data cleaning, transformation, and numerical computations [1].

- Structured Dataset: A curated dataset where each row represents a sample (e.g., a specific compound) and columns contain features (e.g., descriptors, fingerprints) and the target property label.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering: Clean the dataset by handling missing values and outliers. Scale numerical features (e.g., using standardization) and encode categorical variables. This ensures the model receives consistent and meaningful input.

- Model Training and Validation: Split the data into training and testing sets. Train a selected algorithm (e.g., Random Forest) on the training set. Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set to tune hyperparameters and avoid overfitting [1].

- Model Evaluation: Use the held-out test set to evaluate the final model's performance. Report key metrics such as Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression or Precision, Recall, and F1 Score for classification, providing a realistic assessment of predictive power [1].

- Model Conversion to Core ML: Using the coremltools Python package, convert the validated and trained Scikit-learn model into a Core ML model (.mlmodel file). Specify input types and any necessary metadata during conversion [4].

- Deployment and Inference: Integrate the converted .mlmodel file into a macOS or iOS application. Use the generated Swift/Objective-C API to load the model and make predictions on new, unseen data directly on the device [4] [6].

Protocol 2: Developing a Core ML Model for On-Device Material Image Analysis

This protocol outlines the process of converting a deep learning-based image analysis model for deployment via Core ML, enabling real-time, on-device characterization.

Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools:

- TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch: Frameworks for building and training deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [1].

- Core ML Tools Unified Conversion API: The

ct.convert()method for converting models from supported deep learning frameworks into an ML Program or neural network for Core ML [4]. - Apple's Vision Framework: Works in conjunction with Core ML to efficiently process and analyze images on Apple devices [7].

- Annotated Image Dataset: A collection of micrograph or material images labeled for tasks like phase classification or defect detection.

Procedure:

- Model Design and Training: Develop a CNN architecture (e.g., a variant of MobileNetV2 [4]) suitable for the image classification task. Train the model on a powerful machine with a GPU using the annotated image dataset.

- Define Core ML Input: During conversion, define the model's input as an

ImageTypeusing coremltools. Specify the expected image dimensions and any necessary preprocessing parameters, such as bias and scale, to normalize pixel values as required by the original model [4]. - Model Conversion: Use the

coremltools.convert()function to transform the trained TensorFlow/PyTorch model into the Core ML format. For a classifier, also provide aClassifierConfigwith the class labels to bake them directly into the model [4]. - Set Model Metadata: Enhance model usability by setting metadata such as the author, license, and a short description. For image classifiers, set the

com.apple.coreml.model.preview.typeto"imageClassifier"to enable live preview in Xcode [4]. - Integration with Vision Framework: In the target application, use the Vision framework to handle camera input or image loading. Pass the image requests to the Core ML model for classification, leveraging hardware acceleration (Neural Engine/GPU) for optimal performance [7].

Quantitative Performance and Impact Analysis

The integration of AI and ML into scientific R&D is delivering measurable improvements in efficiency, success rates, and cost-effectiveness, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, which shares many challenges with advanced materials development.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of AI/ML in Research and Development

| Performance Metric | Traditional Workflow | AI/ML-Enhanced Workflow | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I Success Rate (Drug Discovery) | 40-65% (industry average) | 80-90% (for AI-discovered drugs) | [3] |

| Preclinical Stage Savings | Baseline | 25-50% time and cost savings | [3] |

| Overall Development Timeline | 10-15 years per drug | Shortened by 1-4 years | [3] |

| On-Device Inference Speed | Network latency-dependent | Near-instantaneous (<100ms reported) | [7] |

| Model Quantization Impact | Full precision (32-bit float) | Size & speed gain with minimal accuracy loss (8-bit integer) | [7] |

Advanced Applications and Regulatory Considerations

The adoption of advanced ML techniques is accelerating the transition from in vitro to in silico research [2]. Generative AI models are now used to create entirely novel molecular structures with desired properties, dramatically expanding the explorable chemical space [3]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are particularly powerful for materials science, as they can naturally model the graph-structured data of molecules, learning over atoms and bonds to predict properties or reactivity [1].

This technological shift is being met with evolving regulatory frameworks. The FDA has published guidance on "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision Making," emphasizing transparency, explainability, and bias mitigation [3]. Furthermore, the ICH E6(R3) guideline for Good Clinical Practice now includes provisions for the ethical and effective integration of AI in clinical trials, a precedent that may extend to other regulated research areas [3].

The process of discovering and synthesizing new functional materials and molecules has long been a fundamental bottleneck in scientific and therapeutic advancement. Traditional approaches, which rely heavily on iterative trial-and-error experimentation and human intuition, are increasingly inadequate for navigating the vastness of chemical space. This document details a transformative paradigm, enabled by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), that is redefining the discovery workflow. By integrating data-driven insights with automated experimentation, this new workflow accelerates the path from initial data to actionable synthesis plans, thereby expediting the development of next-generation materials and pharmaceuticals [8] [9].

This paradigm shift is characterized by a move from traditional forward-screening methods towards inverse design, where the process begins with the desired property or function, and AI works backward to design candidate materials or molecules that meet these criteria [10]. This approach, powered by deep generative models and sophisticated synthesis planning algorithms, is drastically reducing the time and cost associated with discovery while opening up previously inaccessible regions of chemical space [8] [11].

Core AI Methodologies for Synthesis Planning

The integration of AI into synthesis planning spans several computational techniques, each contributing uniquely to the workflow. The table below summarizes the key algorithms, their applications, and their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Key Artificial Intelligence Algorithms in Synthesis Planning and Materials Discovery

| Algorithm Category | Example Algorithms | Primary Application in Discovery Workflow | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Generative Models | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Diffusion Models [8] [10] | Inverse design of novel molecules and materials with target properties [10]. | Capable of generating novel, high-quality candidate structures; enables navigation of high-dimensional design spaces. | Training can be unstable (GANs); slow generation (Diffusion); requires careful tuning [10]. |

| Retrosynthesis Planning | Transformer-based Models, Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), Retro* [11] [12] | Deconstructing target molecules into feasible precursor sequences and recommending synthetic routes [11]. | Automates a highly complex task traditionally requiring expert knowledge; can propose non-intuitive routes. | High computational latency can hinder real-time use; relies on the quality and breadth of reaction data [12]. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [10] | Optimizing multi-step synthetic pathways and reaction conditions. | Learns complex policies through interaction and feedback; suitable for sequential decision-making. | Training is inefficient and requires significant hyperparameter tuning [10]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | ... [8] | Optimizing experimental parameters and reaction conditions with minimal data points. | Highly data-efficient for optimizing black-box functions. | Computationally intensive and performance depends on the choice of prior [10]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Llama, GPT-4 [11] [13] | Powering conversational AI for robotic labs, autonomously activating synthesis strategies, and interpreting scientific literature. | Exceptional at natural language tasks and versatile across domains. | Can generate biased or incorrect output; requires enormous computational resources [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating AI-Driven Synthesis

Protocol: Validation of a Hybrid Organic-Enzymatic Synthesis Plan

Objective: To experimentally validate a multi-step synthetic route for a target organic compound or natural product, as proposed by the ChemEnzyRetroPlanner platform [11].

Background: This protocol leverages an open-source hybrid synthesis planning platform that combines organic and enzymatic retrosynthesis with AI-driven decision-making. A key innovation is the RetroRollout* search algorithm, which has demonstrated superior performance in planning synthesis routes across multiple datasets [11].

Materials:

- Software: ChemEnzyRetroPlanner web platform or local installation with API access.

- Target Molecule: SMILES string or molecular structure file of the desired compound.

Procedure:

- Input and Strategy Activation: Input the target molecule's structure into the ChemEnzyRetroPlanner platform. The system autonomously activates its hybrid strategy using a chain-of-thought strategy powered by the Llama3.1 model to determine the optimal sequence of organic and enzymatic steps [11].

- Route Generation: The RetroRollout* algorithm performs a tree search to generate multiple candidate retrosynthetic pathways. Each disconnection step is evaluated by a neural network to guide the search toward synthetically accessible precursors.

- Enzyme Recommendation: For steps designated as enzymatic, the platform's computational module recommends specific enzymes based on template-based and/or AI-driven similarity searches within biochemical reaction databases (e.g., Rhea, KEGG) [11].

- In silico Validation: The platform performs an in-silico validation of the proposed enzyme's active site to assess the plausibility of the substrate fitting and reacting.

- Condition Prediction: The system predicts suitable reaction conditions (e.g., solvent, temperature, pH) for both the organic and enzymatic steps.

- Route Selection and Export: Evaluate the proposed routes based on a combined score of plausibility, predicted yield, number of steps, and cost. Export the selected route as a detailed, step-by-step experimental procedure.

- Experimental Execution: Execute the synthesis in the laboratory, following the platform's exported procedure. For enzymatic steps, ensure the use of mild, aqueous-compatible conditions to maintain enzyme activity.

- Validation and Analysis: Confirm the structure and purity of the final product and intermediates using standard analytical techniques (NMR, LC-MS, HPLC).

Protocol: High-Throughput Synthesizability Screening with Accelerated CASP

Objective: To rapidly integrate synthesizability assessment into de novo molecular design cycles, requiring synthesis planning to occur within seconds per molecule [12].

Background: High-throughput virtual screening can generate thousands of candidate drug-like molecules. This protocol uses a accelerated computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) system to filter these libraries for synthetic accessibility in near real-time.

Materials:

- Software: Modified AiZynthFinder software incorporating a transformer neural network and speculative beam search (Medusa) for acceleration [12].

- Input: A library of candidate molecules in SMILES format.

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Prepare a virtual library of candidate molecules generated by a de novo design algorithm.

- System Configuration: Configure the accelerated AiZynthFinder to use a SMILES-to-SMILES transformer as the single-step retrosynthesis model, with the speculative beam search replacing the standard beam search algorithm [12].

- High-Throughput Planning: Submit the entire library to the CASP system with a strict time constraint (e.g., a few seconds per molecule).

- Route Analysis: The system will return a result for each molecule, indicating whether a synthetic route was found within the time limit.

- Library Filtering: Filter the virtual library to retain only those molecules for which a viable synthetic route was successfully identified, thereby ensuring prioritization of synthesizable candidates for further experimental exploration.

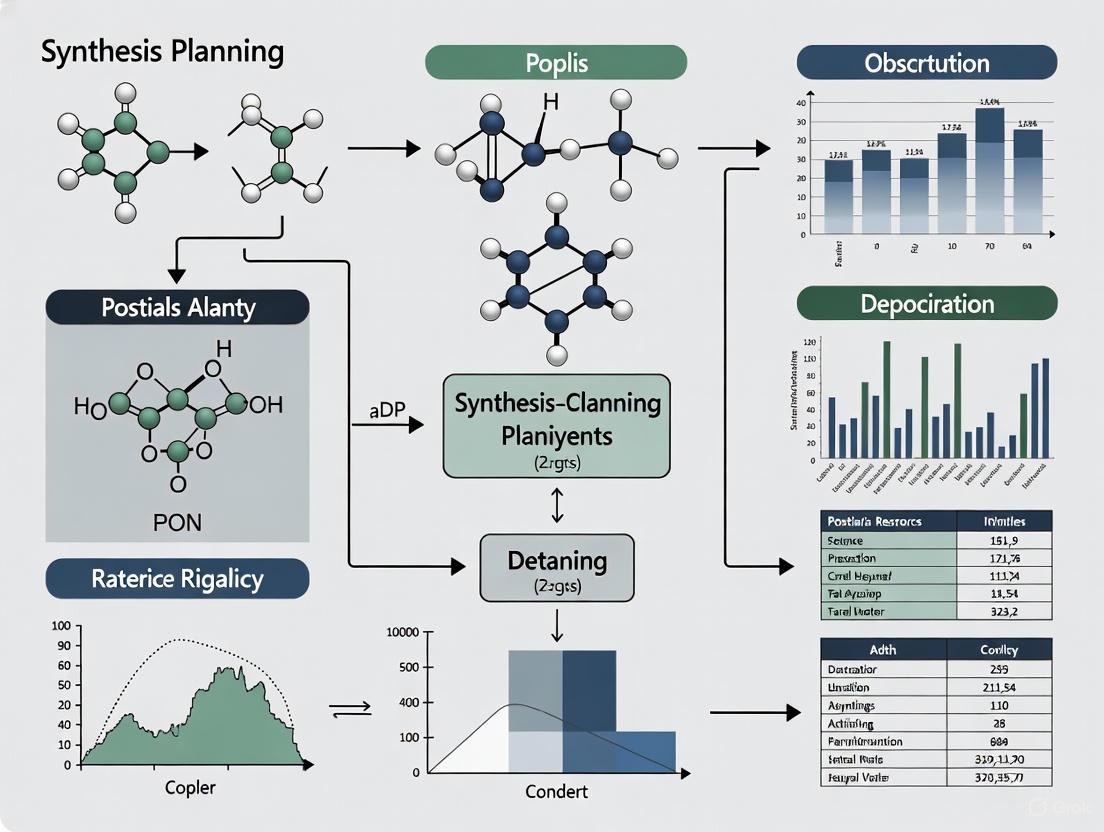

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and data flows within the modern AI-driven discovery workflow.

AI-Driven Materials & Molecule Discovery Workflow

Hybrid Organic-Enzymatic Synthesis Planning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Platforms

This section details the essential computational tools and platforms that form the backbone of the AI-driven synthesis workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms for AI-Driven Synthesis

| Tool/Platform Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemEnzyRetroPlanner [11] | Synthesis Planning Platform | Open-source tool for hybrid organic-enzymatic retrosynthesis planning, featuring the RetroRollout* algorithm. | Web Platform / API |

| AiZynthFinder [11] [12] | Synthesis Planning Software | Fast, robust, and flexible open-source software for retrosynthetic planning, often used with transformer models. | Open-Source Software |

| AutoGluon, TPOT, H2O.ai [8] | AutoML Framework | Automates the process of model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and feature engineering for materials informatics. | Library / Framework |

| Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW [8] | Materials Database | Large-scale databases of computed material properties providing the foundational data for training ML models. | Public Database |

| Reaxys, SciFinder [14] | Organic Reaction Database | Commercial databases of organic reactions and substances, providing data for training retrosynthesis models. | Commercial Database |

| Rhea, KEGG [11] | Biochemical Reaction Database | Manually curated resources of enzymatic reactions, used for enzyme recommendation in hybrid synthesis planning. | Public Database |

Application Note: Predicting Material Synthesizability for Targeted Discovery

A significant bottleneck in materials discovery lies in identifying chemically feasible, synthesizable materials from the vast hypothetical chemical space. This protocol details the use of a deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN) to classify inorganic crystalline materials as synthesizable based solely on their chemical composition, enabling prioritization of candidates for experimental synthesis [15]. This approach reformulates material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, integrating seamlessly into computational screening workflows.

Key Quantitative Performance

Table 1: Performance comparison of synthesizability prediction methods [15].

| Method | Key Metric | Performance | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN (Deep Learning) | Precision | 7x higher than formation energy | Learns chemistry from data; requires no structural input |

| Charge-Balancing Heuristic | Coverage of Known Materials | 37% of known synthesized materials | Chemically intuitive but inflexible |

| Human Expert | Discovery Precision & Speed | Outperformed by SynthNN (1.5x higher precision, 10^5x faster) | Specialized domain knowledge; slow |

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To train and apply a synthesizability classification model for inorganic chemical formulas.

Materials and Input Data:

- Positive Data: Chemical formulas of synthesized crystalline inorganic materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [15].

- Unlabeled Data: Artificially generated chemical formulas not present in the ICSD, treated as unsynthesized for training [15].

- Software: Python with deep learning frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Compile a list of chemical formulas from the ICSD to represent the "synthesized" class [15].

- Dataset Augmentation (Positive-Unlabeled Learning): Generate a larger set of hypothetical chemical formulas. This combined dataset is used for training with semi-supervised learning techniques that probabilistically reweight unlabeled examples [15].

- Model Training:

- Implement an

atom2vecrepresentation, where an embedding vector for each element type is learned directly from the data distribution [15]. - Train a neural network classifier (SynthNN) using the augmented dataset. The model learns to map the learned compositional representation to a synthesizability probability without explicit feature engineering [15].

- Implement an

- Model Validation: Evaluate performance using standard metrics (e.g., Precision, F1-score) on a hold-out test set, treating synthesized and artificially generated formulas as positive and negative examples, respectively [15].

- Screening: Apply the trained model to screen large databases of candidate compositions or generative AI outputs to rank them by synthesizability likelihood.

Application Note: Interpretable Deep Learning for Structure-Property Relationships

Understanding the physical mechanisms linking a material's atomic structure to its macroscopic properties is crucial for rational design. This protocol describes the use of an interpretable deep learning architecture, the Self-Consistent Attention Neural Network (SCANN), to predict material properties and identify critical local structural features governing these properties [16]. The incorporated attention mechanism provides insights into atomic contributions, moving beyond "black-box" predictions.

Key Quantitative Performance

Table 2: Capabilities of the SCANN framework for structure-property mapping [16].

| Aspect | Key Feature | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Model Architecture | Self-consistent attention layers + global attention layer | Predicts formation energies, molecular orbital energies |

| Interpretability Output | Attention scores for local atom environments | Identifies atoms/local structures critical to target property |

| Physical Insight | Links attention scores to physicochemical principles | Reveals influence of specific atomic arrangements on properties |

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To build a predictive and interpretable model for material properties from atomic structure data.

Materials and Input Data:

- Datasets: Crystalline materials (e.g., from Materials Project) or molecular datasets (e.g., QM9) containing atomic coordinates, atomic numbers, and target properties [16].

- Software: Python with scientific computing (NumPy) and deep learning libraries.

Procedure:

- Structure Representation:

- Model Implementation (SCANN):

- Construct the network with

Llocal attention layers followed by a final global attention layer [16]. - Local Attention Layers: Recursively update the representation of each atom's local environment by applying attention mechanisms over its neighbors. This captures long-range interactions within the material [16].

- Formula for representation update:

c_i^{l+1} = Attention(q_i^l, K_{N_i}^l) + q_i^l[16]

- Formula for representation update:

- Global Attention Layer: Combine the refined local representations into a single representation for the entire material structure, weighted by the learned attention scores [16].

- Construct the network with

- Training: Train the SCANN model end-to-end to predict a specific target property (e.g., formation energy).

- Interpretation: Analyze the attention scores from the global attention layer to determine which local atomic structures received the highest attention for the property prediction, providing explicit identification of crucial features [16].

Workflow Visualization

Application Note: Foundational Vision Transformers for Microstructure-Property Relationships

Predicting properties based on material microstructure (e.g., from micrographs) typically requires training custom, property-specific models, which is data-intensive and costly. This protocol leverages pre-trained Foundational Vision Transformers (ViTs) as universal feature extractors to create robust microstructure representations, enabling accurate property prediction with simple subsequent models and minimal computational overhead [17].

Key Quantitative Performance

Table 3: Performance of ViT-based features for property prediction [17].

| Use Case | Material System | ViT Model Used | Performance Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Stiffness | Synthetic two-phase microstructures | DINOv2, CLIP, SAM | Comparable accuracy to 2-point correlations |

| Vickers Hardness | Ni/Co-base superalloys (exp. data) | DINOv2 | Accurately predicted hardness from literature images |

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To predict material properties from microstructure images using pre-trained Vision Transformers without task-specific fine-tuning.

Materials and Input Data:

- Microstructure Images: 2D micrographs from experiments or simulations [17].

- Property Data: Corresponding property values for each image (e.g., hardness, elastic modulus) [17].

- Pre-trained Models: State-of-the-art ViTs (e.g., DINOv2, CLIP, SAM) [17].

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Assemble a dataset of microstructure images and their measured or simulated properties [17].

- Feature Extraction:

- Perform a "forward pass" of each microstructure image through a pre-trained ViT.

- Extract the image-level feature vectors from the transformer's output. These features serve as a task-agnostic representation of the microstructure [17].

- Model Training:

- Validation: Validate the model on a held-out test set of images to assess prediction accuracy.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential computational and data resources for AI-driven materials discovery.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Public Materials Databases | Provide structured data on known materials for model training and benchmarking. | Materials Project, AFLOW, OQMD, ICSD [18] [15] |

| Atomistic Graph Representations | Represents a material as a graph of atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges) for ML input. | Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks [16] [18] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generate novel, optimized molecular structures with desired properties for drug and material design. | Used in de novo molecular design [19] |

| Vision Transformers (ViTs) | Extract powerful, general-purpose features from microstructure images for property prediction. | DINOv2, CLIP, SAM models [17] |

| Synthesis Extraction Pipeline | Uses NLP to automatically extract synthesis parameters and conditions from scientific literature. | MIT Synthesis Project tools [20] |

| Fully Homomorphic Encryption | Enables privacy-preserving collaborative machine learning on encrypted data. | Used in federated learning for drug design [21] |

The integration of machine learning (ML) into materials science has established a new paradigm for accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials. This data-driven approach is transforming the research landscape, reducing development cycles from decades to mere months in some cases [22]. The general workflow of ML-assisted materials design provides a structured pathway from data collection to practical application, enabling the prediction of material properties and the design of new compounds even when underlying physical mechanisms are not fully understood [23]. Within the specific context of synthesis planning—a critical bottleneck in materials discovery—ML workflows offer particular promise for predicting synthesis recipes and optimizing reaction conditions for novel materials [24] [14]. This Application Note provides a detailed, practical guide to implementing the materials ML workflow, with special emphasis on applications in synthesis planning.

Dataset Construction and Preprocessing

The foundation of any successful ML application in materials science is a high-quality dataset. Data can be sourced from both experimental and computational origins, with each presenting distinct advantages. Experimental data, obtained through actual observations and measurements, generally holds greater persuasive power for real-world validation, while computational data from well-designed models can provide valuable insights when experimental data is limited or challenging to obtain [23].

For inorganic materials, elemental composition and process parameters can be transformed into mathematical descriptors using Python packages such as Mendeleev and Matminer, which generate features based on elemental properties through operators like maximum value, minimum value, average, and standard deviation [23]. For organic materials with more complex molecular structures, molecular descriptors and fingerprints obtained through tools like RDKit and PaDEL provide crucial structural information [23]. Additionally, domain knowledge can be incorporated through specially constructed features, such as tolerance factors for perovskite stability or phase parameters for high-entropy alloys [23].

Recent advances have demonstrated the effectiveness of AI-powered workflows for constructing specialized materials databases directly from published literature. These systems can process full-text scientific papers, identifying relevant paragraphs and extracting structured synthesis information through natural language processing techniques [25]. For synthesis planning applications, text-mining approaches have successfully extracted tens of thousands of solid-state and solution-based synthesis recipes from literature sources, though challenges remain in standardization and data quality [14].

Table 1: Data Sources for Materials ML

| Data Type | Example Sources | Extraction Methods | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Data | Literature, Laboratory notebooks, Autonomous labs | Manual curation, Automated protocols | Model training with high real-world validity |

| Computational Data | DFT databases (e.g., alexandria), Materials Project | High-throughput calculations, API access | Large-scale initial screening, Feature generation |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Recipes | Scientific publications, Patents | NLP, Transformer models (e.g., ACE), Rule-based extraction | Synthesis condition prediction, Pathway optimization |

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Raw materials data frequently requires significant preprocessing before being suitable for ML modeling. Common issues include variations in reported values for the same composition across different sources, missing values, outliers, and duplicate samples with identical features but different target values [23]. Effective preprocessing pipelines must address these challenges through:

- Handling missing values: Techniques range from simple deletion to advanced imputation methods like KNNImputer and IterativeImputer [26].

- Addressing outliers: Statistical methods and algorithms such as Isolation Forest can identify and handle anomalous data points [26].

- Data transformation: Operations including logarithmic transformation and standardization may be applied to improve model performance and convergence [23].

Data quality assessment should evaluate multiple dimensions including completeness, uniqueness, validity, and consistency. Automated quality analyzers can generate overall data quality scores and provide prioritized recommendations for remediation [26]. For synthesis planning applications, particular attention must be paid to the reproducibility of reported protocols and the balancing of chemical reactions when extracting synthesis information from literature sources [14].

Feature Engineering and Selection

Feature Engineering Strategies

Feature engineering transforms raw materials data into informative descriptors that enhance model performance. For compositional data, a common approach involves generating statistics (mean, max, min, range, standard deviation) of elemental properties across the constituent elements [23]. More sophisticated feature construction methods include the Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator (SISSO) approach, which combines simple descriptors using mathematical operators to create a multitude of more intricate features [23].

For synthesis-focused applications, features must capture relevant aspects of synthesis protocols, including precursors, processing conditions (temperature, time, atmosphere), and post-synthesis treatments. These can be represented as action sequences with associated parameters, enabling machines to interpret and reason about synthesis procedures [27].

Feature Selection Methodologies

Feature selection is crucial for improving model interpretability, reducing overfitting, and enhancing computational efficiency. Common approaches can be categorized into three main classes:

- Filter methods: Model-agnostic techniques that include variance threshold filtering, Pearson correlation coefficient, maximum information coefficient, and maximum relevance minimum redundancy (mRMR) [23].

- Wrapper methods: Algorithm-specific approaches that evaluate feature subsets based on model performance, including sequential forward/backward selection and recursive feature elimination [23] [26].

- Embedded methods: Techniques that incorporate feature selection directly into model training, such as regularization in linear models (LASSO) or feature importance in tree-based models [23].

In practice, a multi-stage feature selection workflow often yields optimal results, beginning with importance-based filtering using model-intrinsic metrics, followed by more rigorous wrapper methods like genetic algorithms or recursive feature elimination for final subset selection [26].

Table 2: Feature Selection Methods in Materials ML

| Method Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Variance threshold, PCC, MIC, mRMR | Computationally efficient, Model-agnostic | Ignores feature interactions, May select redundant features |

| Wrapper Methods | SFS/SBS, RFA/RFE, Genetic Algorithms | Considers feature interactions, Optimizes for specific model | Computationally intensive, Risk of overfitting |

| Embedded Methods | LASSO, Ridge Regression, Tree feature importance | Balances efficiency and performance, Model-specific | Tied to specific algorithm, May not transfer well between models |

Model Development, Evaluation, and Selection

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization

The model development phase involves selecting appropriate algorithms, training models on prepared datasets, and optimizing hyperparameters. Materials informatics platforms typically incorporate a broad library of ML models from frameworks like Scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, supporting both regression and classification tasks [26].

Hyperparameter optimization is automated using libraries such as Optuna, which employs efficient Bayesian optimization to identify optimal model configurations [26]. This approach intelligently explores the hyperparameter space, pruning unpromising trials early to concentrate computational resources on the most promising configurations.

Model Evaluation and Selection Criteria

Model evaluation assesses both predictive performance and generalization capability. Standard practice involves partitioning data into training and test sets, with strategies for this division potentially impacting model performance and evaluation [23]. Beyond standard accuracy metrics, researchers should assess model extrapolation capability and stability, particularly for synthesis planning applications where models may encounter entirely new material compositions or reaction conditions [23].

The selection of the optimal model should not rely solely on accuracy metrics but should also consider model complexity, interpretability, and computational requirements for inference. For synthesis planning, where human experimental validation is often required, model interpretability can be as important as pure predictive accuracy [24].

Model Application in Synthesis Planning

Predictive Synthesis and Inverse Design

Trained ML models can be applied to predict synthesis conditions for novel materials or optimize existing synthesis protocols. Two primary strategies exist for designing candidates with desired properties: generating numerous virtual samples and filtering them through predictive models, or incorporating optimization algorithms to actively identify promising candidates [23]. For multi-objective optimization problems—common in synthesis where multiple property trade-offs must be balanced—methods include ε-constrained approaches or converting to single-objective optimization using weighted methods [23].

Advanced platforms like the CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) system demonstrate the integration of multimodal information—including literature insights, chemical compositions, and microstructural images—to optimize materials recipes and plan experiments [28]. Such systems can explore hundreds of chemistries and conduct thousands of tests, leading to discoveries like improved fuel cell catalysts with significantly reduced precious metal content [28].

Interpretation and Physical Insight

Beyond predictive applications, ML models can provide scientific insights through interpretation techniques. Methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), partial dependence plots (PDP), and sensitivity analysis techniques help elucidate relationships between input features and target variables [23] [26]. These approaches can reveal how specific synthesis parameters influence final material properties, contributing to fundamental understanding of materials synthesis mechanisms.

In some cases, anomalous synthesis recipes that defy conventional intuition—when identified through analysis of large text-mined datasets—can lead to new mechanistic hypotheses about how solid-state reactions proceed [14]. These insights can then be validated through targeted experiments, creating a virtuous cycle of computational analysis and experimental verification.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Text-Mining Synthesis Recipes

Purpose: Extract structured synthesis information from scientific literature to build datasets for synthesis planning models.

Materials:

- Scientific publications in HTML/XML format (post-2000 for better parsing)

- Natural language processing tools (e.g., transformer models, BiLSTM-CRF networks)

- Annotation software for manual validation

- Computational resources for processing large text corpora

Procedure:

- Procure full-text literature with appropriate permissions from scientific publishers.

- Identify synthesis paragraphs using probabilistic assignment based on keywords associated with materials synthesis.

- Extract precursor and target materials by replacing chemical compounds with placeholders and using sentence context clues to label their roles.

- Construct synthesis operations by clustering keywords into topics corresponding to specific operations (mixing, heating, drying, etc.) using latent Dirichlet allocation or similar methods.

- Compile synthesis recipes into structured format (e.g., JSON) with balanced chemical reactions where possible.

- Validate extraction accuracy through manual checking of random paragraphs, with target extraction yield typically around 28% for solid-state synthesis recipes [14].

Protocol for Autonomous Synthesis Optimization

Purpose: Implement closed-loop optimization of synthesis conditions using ML-guided experimental workflows.

Materials:

- Robotic synthesis equipment (liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock systems)

- Automated characterization tools (electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction)

- High-throughput testing apparatus (automated electrochemical workstations)

- Computational infrastructure for active learning models

- Cameras and sensors for experimental monitoring

Procedure:

- Define search space including potential precursor elements and processing parameters.

- Initialize knowledge base by embedding previous literature and experimental results.

- Design experiments using Bayesian optimization in reduced search space identified through principal component analysis.

- Execute robotic synthesis according to optimized recipes.

- Characterize resulting materials using automated techniques.

- Test material performance in target applications.

- Incorporate results into knowledge base and refine models.

- Iterate process until performance targets are met or resources exhausted.

- Monitor experiments with computer vision systems to identify and address reproducibility issues [28].

Visualization of Workflows

Materials ML Workflow Diagram

Synthesis Planning Workflow Diagram

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Materials ML Workflows

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Synthesis Planning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matminer | Python package | Feature generation from composition/structure | Creating descriptors for synthesis-property relationships |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics library | Molecular descriptor calculation | Representing organic molecular structures for synthesis prediction |

| MatSci-ML Studio | GUI-based toolkit | Automated ML workflows | Accessible model development without coding for experimentalists |

| ACE (sAC transformEr) | Transformer model | Synthesis protocol extraction | Converting unstructured synthesis text to structured actions |

| CRESt | Integrated platform | Multimodal learning and robotic experimentation | Closed-loop synthesis optimization with real-time feedback |

| Automatminer | Python pipeline | Automated featurization and model benchmarking | High-throughput synthesis condition prediction |

| ChemDataExtractor | NLP toolkit | Information extraction from chemical literature | Building synthesis databases from published papers |

From Theory to Practice: ML Methods and Real-World Synthesis Applications

The integration of machine learning (ML) into materials science represents a paradigm shift in the discovery and development of new materials. Traditional methods, which rely heavily on computational simulations like density functional theory (DFT) and extensive experimental testing, are often limited by their high computational cost, time consumption, and inability to easily capture complex, non-linear relationships in multi-component material systems [29] [30] [31]. This is particularly true in the fields of concrete technology and composite materials, where the mechanical properties are governed by intricate interactions between constituent materials, processing conditions, and microstructural characteristics.

Machine learning offers a powerful alternative, enabling the accurate prediction of material properties by learning patterns from existing empirical data [31]. This data-driven approach facilitates a more efficient exploration of the vast design space for material composition and processing parameters, significantly accelerating the development cycle. Framed within the context of synthesis planning for materials science research, predictive ML models serve as in-silico design tools. They allow researchers to pre-screen promising material combinations and optimize synthesis protocols before committing resources to physical experiments, thereby creating a more rational and accelerated path from material concept to realization.

This application note provides a detailed overview of the application of machine learning for predicting the properties of two key material classes: concrete and composites. It synthesizes recent case studies, presents structured quantitative data, outlines detailed experimental and computational protocols, and visualizes the core workflows to equip researchers with the practical knowledge to implement these approaches in their own synthesis planning pipelines.

Machine Learning Applications in Concrete Science

The development of sustainable, high-performance concrete mixtures is a key area benefiting from ML prediction. Researchers are actively using these methods to model the behavior of complex systems incorporating supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) and alternative aggregates.

The following table summarizes recent research efforts in ML-based prediction of concrete mechanical properties, highlighting the material systems, models used, and performance achieved.

Table 1: Machine Learning Applications in Concrete Property Prediction

| Material System | Target Properties | Key ML Models Employed | Best Performing Model (Reported R²) | Critical Input Features Identified | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled Aggregate Concrete with SCMs | Compressive, Flexural, Splitting Tensile Strength, Elastic Modulus | SSA-XGBoost, Hybrid Algorithms | SSA-XGBoost (Not specified, but "most satisfactory") | Water-binder ratio, Cement content, Superplasticizer dosage | [32] |

| Concrete with Nano-Engineered SCMs | Tensile Strength | Hybrid Ensemble Model (HEM), ANN, XGBoost, SVR | HEM (K-fold CV composite score: 96) | Cement content, w/c ratio, Nano-clay content | [33] |

| Concrete with Secondary Treated Wastewater & Fly Ash | Compressive, Split Tensile, Flexural Strength | Random Forest, Decision Tree, MLP | Random Forest (Superior accuracy for compressive strength) | Fly Ash proportion, Water type | [34] |

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) Concrete | Compressive Strength (CS), Splitting Tensile Strength (STS) | Decision Tree (DTR), Gaussian Process (GPR), Random Forest (RFR) | DTR (CS R²=0.964, STS R²=0.969) | Age, Cement, RHA content, Superplasticizer | [35] |

| Cement Composites with Granite Powder | Compressive Strength, Bonding Strength, Packing Density | Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) | MLP (R > 0.9 for all outputs) | Granite powder content, Cement, Sand, Water content | [36] |

| Waste Iron Slag (WIS) Concrete | Compressive & Tensile Strength | Decision Tree, XGBoost, SVM | DT & XGBoost (R² = 0.951) | WIS incorporation ratio, Fine aggregate, Concrete age | [37] |

Experimental Protocol: Development of an ML Model for Concrete Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the general workflow for developing a machine learning model to predict the mechanical properties of concrete, based on methodologies common to the cited studies.

Step 1: Database Curation and Preprocessing

- Data Collection: Compile a comprehensive database from peer-reviewed literature and/or experimental work. The dataset for concrete typically includes mix design parameters (e.g., cement, SCMs, water, aggregates, chemical admixtures) and curing conditions as inputs, and measured mechanical properties (e.g., compressive strength, tensile strength) as outputs [32] [33] [35].

- Data Cleaning: Handle missing values, outliers, and unit inconsistencies.

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets. A common split is 70:30 or 80:20 for train:test [35]. To avoid overestimation of performance, consider redundancy control algorithms like MD-HIT if the dataset contains many highly similar mixtures [29].

Step 2: Feature Selection and Engineering

- Perform correlation analysis (e.g., using Pearson correlation coefficients) to identify input parameters with the strongest influence on the target property [35].

- In some cases, feature engineering (e.g., creating ratios like water-to-binder ratio) can improve model performance.

Step 3: Model Selection and Training

- Select a suite of ML algorithms suitable for regression tasks. Common choices include:

- Employ Grid Search or Bayesian Optimization with cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold CV) on the training set to tune model hyperparameters [33] [35].

Step 4: Model Validation and Interpretation

- Performance Evaluation: Test the trained models on the held-out test set. Use metrics like Coefficient of Determination (R²), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [32] [35] [37].

- Model Interpretation: Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) to quantify feature importance and understand the relationship between input parameters and the predicted property [32] [38] [35]. This step is critical for extracting scientific insight and guiding future experiments.

Step 5: Deployment and Prospective Validation

- Deploy the best-performing model as a tool for predicting properties of new, untested mix designs.

- For full integration into synthesis planning, prospectively validate model predictions by conducting a limited number of physical experiments on recommended mixtures.

Machine Learning Applications in Composite Materials

The design of composite materials, particularly polymer-based composites with various fillers, is another field where ML is making a significant impact by navigating complex process-structure-property relationships.

The table below summarizes key case studies applying ML to predict the properties of fiber-reinforced and nanoparticle-enhanced composites.

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in Composite Property Prediction

| Material System | Target Properties | Key ML Models Employed | Best Performing Model (Reported R²) | Critical Input Features Identified | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle-Modified Carbon Fiber/Epoxy | Tensile Strength, Flexural Strength | Decision Tree, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost | Decision Tree (Tensile R²=0.983), Gradient Boosting (Flexural R²=0.931) | Fiber layer count, Sonication & Curing temperature, Curing duration | [38] |

| Thermoplastic Composites with Fibrous/Dispersed Fillers | Tensile Strength, Elongation, Density, Wear Intensity | Regression Models (Type not specified) | Regression Model (R² up to 0.80 for elongation) | Filler type, Filler concentration | [30] |

Experimental Protocol: Development of an ML Model for Composite Property Prediction

This protocol details the process for building an ML model to forecast the properties of composite materials, emphasizing the specific parameters relevant to this material class.

Step 1: Database Curation and Preprocessing

- Data Collection: Assemble a dataset encompassing:

- Constituent Materials: Polymer matrix type, filler/fiber type (e.g., carbon, basalt), filler morphology (fibrous, dispersed, nano-dispersed), filler size, and filler concentration (wt.%) [38] [30].

- Processing Parameters: Sonication time and temperature, curing time and temperature, mixing method [38].

- Target Properties: Tensile strength, flexural strength, wear resistance, etc. [38] [30].

- Data Cleaning and Splitting: Follow similar procedures as in the concrete protocol. Be mindful of the potential for smaller dataset sizes in composites research [38].

Step 2: Feature Selection and Engineering

- Analyze the correlation between all input parameters (materials and processing) and the target properties.

- Processing parameters are often as critical as composition in composites [38].

Step 3: Model Selection, Training, and Interpretation

- The model selection and training process is analogous to the concrete protocol. Tree-based models and gradient boosting methods have shown excellent performance [38] [37].

- The use of SHAP analysis is highly recommended to interpret the model. For instance, it can reveal whether a property is more influenced by the fiber content or the curing temperature [38].

Step 4: Deployment for Material Design

- Use the validated model to identify promising combinations of filler type, concentration, and processing conditions to achieve a desired set of properties, reducing the need for exhaustive trial-and-error experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section lists key materials and computational tools frequently used in the research and development of ML-predicted concrete and composites, as derived from the case studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function / Relevance in Predictive Modeling | Example Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) | Fly Ash, Rice Husk Ash (RHA), Granite Powder | Partial cement replacement to enhance sustainability and modify mechanical properties; key input feature for ML models. | [34] [35] [36] |

| Alternative Aggregates | Recycled Concrete Aggregate, Waste Iron Slag | Replace natural aggregates; their properties are critical inputs for predicting strength in sustainable concrete. | [32] [37] |

| Nano-Engineered Additives | Nano-Clay, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Nano-Silica | Enhance microstructure and mechanical properties; their type and dosage are highly influential input parameters. | [38] [33] |

| Fibrous Reinforcements | Carbon Fibers, Basalt Fibers | Primary reinforcing agents in composites; fiber type, layer count, and content are dominant features in ML models. | [38] [30] |

| Chemical Admixtures | Superplasticizers | Improve workability; their dosage is a key predictive factor for concrete strength and workability. | [32] [33] |

| Polymer Matrices | Epoxy Resin, PTFE | Serve as the binding matrix in composites; the chemical nature of the matrix influences filler compatibility and final properties. | [38] [30] |

| Computational & Data Tools | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explainable AI tool for interpreting ML model predictions and quantifying feature importance. | [32] [38] |

| Computational & Data Tools | MD-HIT | A redundancy reduction algorithm for material datasets to prevent overestimated ML performance. | [29] |

Autonomous laboratories (self-driving labs, SDLs) represent a paradigm shift in materials science and chemistry, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and high-throughput experimentation to accelerate discovery. These systems leverage machine learning (ML) models trained on vast literature datasets and experimental results to plan, execute, and interpret experiments in a closed-loop cycle with minimal human intervention. This publication details the core components, experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions that underpin modern autonomous laboratories, highlighting their application in solid-state materials synthesis and organic chemistry exploration. By framing this within the context of synthesis planning for machine learning-driven materials research, we provide a foundational guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to implement or collaborate with these transformative platforms.

The traditional materials discovery pipeline often requires 10-20 years from initial concept to practical application [39]. Autonomous laboratories aim to compress this timeline to just 1-2 years through the integration of AI-driven decision-making with robotic experimentation [39]. Central to this acceleration is the creation of a closed-loop system where AI agents propose experiments, robotic platforms execute them, and the resulting data is fed back to improve subsequent iterations. This synergistic integration of computational intelligence and physical automation is revolutionizing synthesis planning in materials science.

Modern SDLs successfully combine multiple advanced technologies: robotic hardware for synthesis and characterization, AI models for experimental planning and data analysis, and active learning algorithms for efficient optimization. The A-Lab, a fully autonomous solid-state synthesis platform, exemplifies this integration, having successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel inorganic materials over 17 days of continuous operation—a 71% success rate demonstrating the feasibility of autonomous materials discovery at scale [40] [41]. Similarly, platforms like MIT's CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) leverage multimodal feedback—incorporating literature knowledge, experimental data, and human feedback—to explore complex material chemistries efficiently [28].

The performance of these systems hinges on their ability to learn from diverse data sources, including historical scientific literature, computational databases, and real-time experimental outcomes. Large Language Models (LLMs) now enhance these capabilities further by improving knowledge extraction from text and enabling more sophisticated experimental planning through natural language interactions [42] [41].

Quantitative Performance of Representative Autonomous Laboratories

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recently demonstrated autonomous laboratory systems, highlighting their experimental throughput and success rates across different domains.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Autonomous Laboratories

| System Name | Primary Focus | Experiment Duration | Throughput & Scale | Key Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab | Solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders | 17 days | 58 target compounds | 41 successfully synthesized (71% success rate) | [40] [41] |

| CRESt (MIT) | Fuel cell catalyst discovery | 3 months | >900 chemistries explored, 3,500 electrochemical tests | 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar; record power density achieved | [28] |

| Autonomous Lab (ANL) | Biotechnology (E. coli medium optimization) | Not specified | Multiple components optimized | Improved cell growth rate and maximum cell growth | [43] |

| Modular Platform (Dai et al.) | Exploratory synthetic chemistry | Multi-day campaigns | Complex chemical spaces explored | Successful screening, replication, scale-up, and functional assays | [41] |

Core Components and Workflow Integration

The architecture of an autonomous laboratory integrates hardware, software, and AI coordination systems into a seamless discovery engine. The workflow typically follows a cyclic process of design, synthesis, characterization, and analysis.

Workflow Diagram

Component Specifications

Table 2: Core Components of Autonomous Laboratories

| System Component | Subcomponents & Technologies | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI/ML Planning Module | Natural Language Processing (NLP) models; Bayesian optimization; Active learning; Large Language Models (LLMs) | Proposes synthesis recipes from literature; Optimizes experimental parameters; Plans iterative experiments | Literature-trained models for precursor selection; ARROWS3 algorithm; CRESt's multimodal feedback [40] [28] |

| Robotic Synthesis Hardware | Powder handling robots; Liquid handlers; Mobile robot transporters; Box furnaces; Carbothermal shock systems | Executes physical synthesis: dispensing, mixing, heating, and sample transfer | Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer; Opentrons OT-2 liquid handler; PF400 transfer robot [40] [41] |

| Automated Characterization | X-ray diffraction (XRD); Electron microscopy; Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS); Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) | Provides material identification and property measurement | Automated XRD with Rietveld refinement; UPLC-MS systems; Benchtop NMR [40] [41] |

| Data Analysis & Interpretation | Computer vision; Convolutional neural networks (CNNs); Graph neural networks (GNNs); Automated phase analysis | Interprets characterization data; Identifies synthesis products; Quantifies yields | ML models for XRD phase analysis; Probabilistic models for weight fraction estimation [40] [8] |

| Control & Coordination Software | Multi-agent systems; Laboratory operating systems; Cloud platforms; Application programming interfaces (APIs) | Orchestrates workflow; Manages experimental queue; Enables remote monitoring | Hierarchical multi-agent systems (e.g., ChemAgents); Central management servers [28] [41] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Autonomous Solid-State Synthesis of Novel Inorganic Materials

This protocol outlines the procedure used by the A-Lab for synthesizing novel inorganic powders, demonstrating the integration of robotics with AI-driven synthesis planning [40] [41].

Preparation and Reagents

- Target Materials: 58 novel compounds identified using large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind. Targets were filtered for air stability.

- Precursors: Powdered reagents suitable for solid-state synthesis, selected based on ML analysis of historical literature.

- Equipment Setup:

- Three integrated robotic stations for (1) sample preparation, (2) heating, and (3) characterization.

- Robotic arms for transferring samples and labware between stations.

- Four box furnaces for parallel heating operations.

- Alumina crucibles as reaction vessels.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Target Identification and Validation

- Screen computational databases (e.g., Materials Project) for novel compounds predicted to be on or near (<10 meV per atom) the convex hull of stable phases.

- Confirm air stability by ensuring targets are predicted not to react with O₂, CO₂, and H₂O.

Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation

- Generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using natural-language models trained on text-mined synthesis data from literature.

- Propose synthesis temperatures using ML models trained on heating data from historical sources.

Robotic Synthesis Execution

- At the preparation station, automatically dispense and mix precursor powders according to generated recipes.

- Transfer mixture to alumina crucibles using robotic arms.

- Move crucibles to box furnaces for heating using a second robotic arm.

- Execute heating protocols with temperatures typically ranging from 500°C to 1200°C based on ML recommendations.

- Allow samples to cool after prescribed heating duration.

Automated Characterization and Analysis

- Transfer cooled samples to characterization station using robotic arms.

- Automatically grind samples into fine powders.

- Perform X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements.

- Analyze XRD patterns using probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Confirm phase identification and quantify weight fractions through automated Rietveld refinement.

Active Learning Optimization

- If initial recipes yield <50% target phase, initiate Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) algorithm.

- Use active learning to integrate ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes.

- Prioritize synthesis routes that avoid intermediates with small driving forces to form the target.

- Continue iterative optimization until target is obtained as majority phase or all recipe options are exhausted.

Timing and Optimization

- The complete cycle from recipe generation to characterization requires approximately 4-8 hours per iteration.

- Continuous operation for 17 days enabled testing of 355 distinct synthesis recipes.

- Active learning optimization successfully improved yields for 9 targets, with 6 being obtained only through this iterative process.

Protocol 2: Multimodal AI-Driven Catalyst Discovery

This protocol describes the methodology used by the CRESt system for discovering advanced catalyst materials through integration of multimodal data and robotic experimentation [28].

Preparation and Reagents

- Precursor Materials: Up to 20 precursor molecules and substrates for catalyst formulation.

- Characterization Equipment: Automated electron microscopy, optical microscopy, electrochemical workstations.

- Computational Resources: Access to scientific literature databases and materials informatics platforms.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Multimodal Experimental Design

- Researchers converse with CRESt via natural language interface to define project goals.

- System searches scientific literature for descriptions of relevant elements or precursor molecules.

- Creates knowledge embeddings from literature text and databases to form reduced search space.

Robotic Synthesis and Characterization

- Liquid-handling robot prepares catalyst formulations across multi-element compositional space.

- Carbothermal shock system performs rapid synthesis of material libraries.

- Automated electrochemical workstation tests performance metrics (e.g., activity, stability).

- Characterization via automated electron microscopy and optical microscopy provides structural information.

Multimodal Feedback Integration

- Incorporate experimental results with literature knowledge and human feedback.

- Use Bayesian optimization in the reduced knowledge embedding space to design subsequent experiments.

- Feed newly acquired multimodal data into large language models to augment knowledge base.

- Continuously refine search space based on integrated knowledge.

Computer Vision Monitoring

- Employ cameras and vision language models to monitor experiments.

- Automatically detect issues (e.g., sample misplacement, procedural deviations).

- Suggest corrective actions via text and voice to human researchers.

Timing and Optimization

- Full exploration of >900 chemistries required approximately 3 months.

- System conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests during optimization process.

- Discovered 8-element catalyst delivering 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium benchmark.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Hardware for Autonomous Laboratories

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Starting materials for solid-state synthesis | Wide variety of inorganic oxides and phosphates; Physical properties (density, particle size) affect robotic handling [40] |

| Alumina Crucibles | Reaction vessels for high-temperature synthesis | Withstand repeated heating cycles; Compatible with robotic loading/unloading [40] |

| M9 Medium Components | Defined growth medium for microbial cultivation | Used in biotechnology applications; Enables precise optimization of nutritional components [43] |

| Multi-element Catalyst Libraries | Discovery of novel catalytic materials | Enables exploration of complex compositional spaces; CRESt incorporated up to 8 elements in optimal catalyst [28] |

| Mobile Robot Transporters | Sample transfer between stations | Enable modular laboratory configurations; Free-roaming robots enhance flexibility [41] |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Precise reagent dispensing for solution-phase chemistry | Critical for organic synthesis and biotechnology applications; Enable high-throughput experimentation [43] |

| Box Furnaces | High-temperature processing for solid-state reactions | Multiple units enable parallel synthesis; Integrated with robotic loading systems [40] |

| X-ray Diffractometer | Phase identification and quantification | Coupled with ML models for automated analysis; Essential for characterizing crystalline materials [40] |

| LC-MS/MS System | Analysis of organic molecules and reaction products | Provides structural identification and yield quantification; Integrated into automated workflows [43] |

Autonomous laboratories represent a fundamental transformation in materials research methodology, shifting from human-guided exploration to AI-orchestrated discovery campaigns. By integrating robotics with AI planning systems that leverage both historical literature and experimental data, these platforms dramatically accelerate the synthesis planning and optimization process. The protocols and component specifications detailed herein provide a framework for researchers to implement and advance these technologies. As SDLs evolve toward greater generalization through foundation models, standardized interfaces, and enhanced error recovery, their impact across materials science, chemistry, and drug development will continue to expand, potentially reducing discovery timelines from decades to years.

The integration of surrogate models with evolutionary algorithms like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) represents a paradigm shift in tackling computationally expensive optimization problems in engineering design. Within the broader context of synthesis planning in machine learning materials science research, this approach provides a structured methodology for navigating complex design spaces where traditional optimization methods prove prohibitively costly. Surrogate-Assisted Evolutionary Algorithms (SAEAs) have emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, replacing computationally intensive simulations with efficient approximations during the optimization loop [44]. This protocol details the application of these techniques specifically for aerodynamic and structural design, providing researchers with implementable frameworks for accelerating materials and component development.

Theoretical Foundation

The Surrogate-Assisted Optimization Framework

Surrogate-based optimization addresses a fundamental challenge in engineering design: the computational expense of high-fidelity simulations like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Each simulation may require hours or even days of computation, making direct optimization using evolutionary algorithms—which typically require thousands of function evaluations—computationally infeasible [44]. The surrogate model, often constructed using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Gaussian Processes (Kriging), or other machine learning techniques, approximates the input-output relationship of the expensive simulation, reducing evaluation time from hours to milliseconds [45].

The synergistic relationship between surrogate models and genetic algorithms creates an efficient optimization pipeline. The surrogate model handles the frequent fitness evaluations required by the GA's population-based approach, while the GA provides robust global search capabilities in complex, multi-modal design landscapes where gradient-based methods might fail [45]. This combination is particularly valuable for problems involving conflicting objectives, such as the fundamental trade-off between aerodynamic efficiency and static stability in tailless aircraft designs [45].

Key Surrogate Modeling Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

| Technique | Key Characteristics | Best-Suited Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Multi-layer perceptrons capable of learning highly non-linear relationships [46] [45] | High-dimensional problems with complex input-output mappings [45] | Excellent approximation capability for complex functions; fast execution after training | Requires substantial training data; risk of overfitting without proper validation |

| Gaussian Process Regression (Kriging) | Statistical model providing prediction variance estimates [45] | Problems where uncertainty quantification is valuable | Provides uncertainty estimates for adaptive sampling; good for small-to-medium datasets | Computational cost scales cubically with number of data points |

| Radial Basis Functions (RBFs) | Linear combinations of basis functions [44] | Medium-dimensional problems with smooth response surfaces | Conceptual simplicity; effectiveness for global approximation | Less effective for highly irregular or discontinuous functions |

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Aerodynamic Inverse Design for Airfoil Optimization

This protocol outlines the methodology for optimizing airfoil shapes using a deep learning-genetic algorithm approach, specifically targeting the maximization of lift-to-drag ratio through pressure distribution optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Aerodynamic Inverse Design

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity CFD Solver | Generates training data by solving Navier-Stokes equations | Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) solver |

| Data-Driven Surrogate Model | Approximates relationship between geometry and aerodynamic performance | Deep Neural Network with 70+ neurons in hidden layer [46] |

| Genetic Algorithm Framework | Global optimization searching design space | Real-coded GA with tournament selection [46] |

| Geometry Parameterization | Defines design variables for shape modification | CST parameterization or Free-Form Deformation |

| Elastic Surface Algorithm (ESA) | Inverse design method generating geometry from target pressure [46] | Iterative surface modification algorithm |

Experimental Workflow

The following workflow illustrates the integrated deep learning-genetic algorithm approach for aerodynamic inverse design:

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Initial Data Generation

- Conduct high-fidelity CFD simulations on a diverse set of airfoil geometries (typically 2000-3000 configurations) [46] [45]

- Parameterize airfoil shapes using 6-10 design variables (chord, sweep angle, taper ratio, etc.)

- For each configuration, extract pressure distribution (Cp) and aerodynamic coefficients (CL, CD)

- Split data into training (90%), validation (5%), and testing (5%) sets

Step 2: Deep Learning Surrogate Model Construction

- Design ANN architecture with input layer (geometry parameters), hidden layers, and output layer (aerodynamic coefficients)

- Implement a network with 70+ neurons in hidden layer using sigmoid activation functions [45]

- Train network using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm or similar backpropagation method

- Validate model performance on test set, targeting R² > 0.95 for coefficient predictions

Step 3: Genetic Algorithm Optimization

- Initialize population of 50-100 individuals representing potential optimal pressure distributions

- Define fitness function as lift-to-drag ratio (CL/CD) maximization

- Implement tournament selection, simulated binary crossover, and polynomial mutation

- Use ANN surrogate for fitness evaluation instead of expensive CFD simulations

- Apply elitism to preserve best solutions across generations

Step 4: Geometry Reconstruction and Validation

- Apply Elastic Surface Algorithm (ESA) to convert optimized pressure distribution to physical geometry [46]

- Filter out unrealistic "fishtail" geometries using ANN classification [46]

- Validate final design using high-fidelity CFD simulation

- Confirm performance improvement (e.g., 18% increase in lift-to-drag ratio as demonstrated in FX63-137 airfoil [46])

Protocol 2: Flying Wing Glider Design with Stability Constraints

This protocol addresses the multi-objective optimization of flying wing gliders, explicitly handling the trade-off between aerodynamic performance and static stability.

Experimental Workflow

The following workflow illustrates the flying wing design optimization process with stability constraints:

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table 3: Computational Efficiency of Surrogate vs. Direct Approaches

| Method | Evaluation Time | Optimization Duration | Accuracy | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct CFD Optimization | 2-6 hours per evaluation [45] | Weeks to months | High-fidelity | Final design validation |

| Vortex Lattice Method (VLM) | 5-10 minutes per evaluation [45] | Several days | Medium-fidelity (linear aerodynamics) | Preliminary design studies |

| ANN Surrogate Model | < 1 second per evaluation [45] | Hours to days | Data-dependent accuracy (R² > 0.95 achievable) | Main optimization loop |

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Aerodynamic Database Development

- Parameterize wing geometry using root chord, half wing length, taper ratio, sweep angle, angle of attack, and dihedral angle [45]