Resistive Switching Mechanisms in ReRAM: A 2025 Comparative Guide to ECM, VCM, and Filamentary Dynamics

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the fundamental resistive switching mechanisms in Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM), tailored for researchers and scientists.

Resistive Switching Mechanisms in ReRAM: A 2025 Comparative Guide to ECM, VCM, and Filamentary Dynamics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the fundamental resistive switching mechanisms in Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM), tailored for researchers and scientists. It explores the operational principles of Electrochemical Metallization (ECM) and Valence Change Mechanism (VCM), detailing their distinct ion migration and conductive filament dynamics. The scope extends to advanced characterization methodologies, performance optimization strategies for tackling device variability and endurance, and a comparative analysis for selecting the optimal mechanism for specific applications, including neuromorphic computing, AI hardware, and embedded memory solutions. The insights herein are grounded in the latest research to guide future material and device engineering efforts.

Unraveling the Core Principles: ECM vs. VCM Resistive Switching Mechanisms

Operating Principles and Resistive Switching Mechanisms

Resistive Random Access Memory (ReRAM) is an emerging non-volatile memory technology that stores data by changing the resistance of a material layer sandwiched between two electrodes. [1] Its fundamental structure is a two-terminal Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) capacitor-like device, where the insulating layer functions as the resistive switching layer. [2] The memory function is achieved through resistive switching, a reversible change in electrical resistance induced by applying appropriate voltage pulses. [3]

The basic operation involves three key processes: [2]

- Electroforming: An initial voltage application that forms conductive paths in a pristine device, transitioning it from a high resistance state (HRS) to a low resistance state (LRS).

- SET Process: Subsequent switching from HRS to LRS at a specific voltage (V_SET).

- RESET Process: Switching back from LRS to HRS at a different voltage (V_RESET).

Two primary resistive switching modes exist based on voltage polarity: [2]

- Bipolar Resistive Switching (BRS): SET and RESET processes occur under voltages of opposite polarity.

- Unipolar Resistive Switching (URS): Both SET and RESET processes are triggered by voltages of the same polarity.

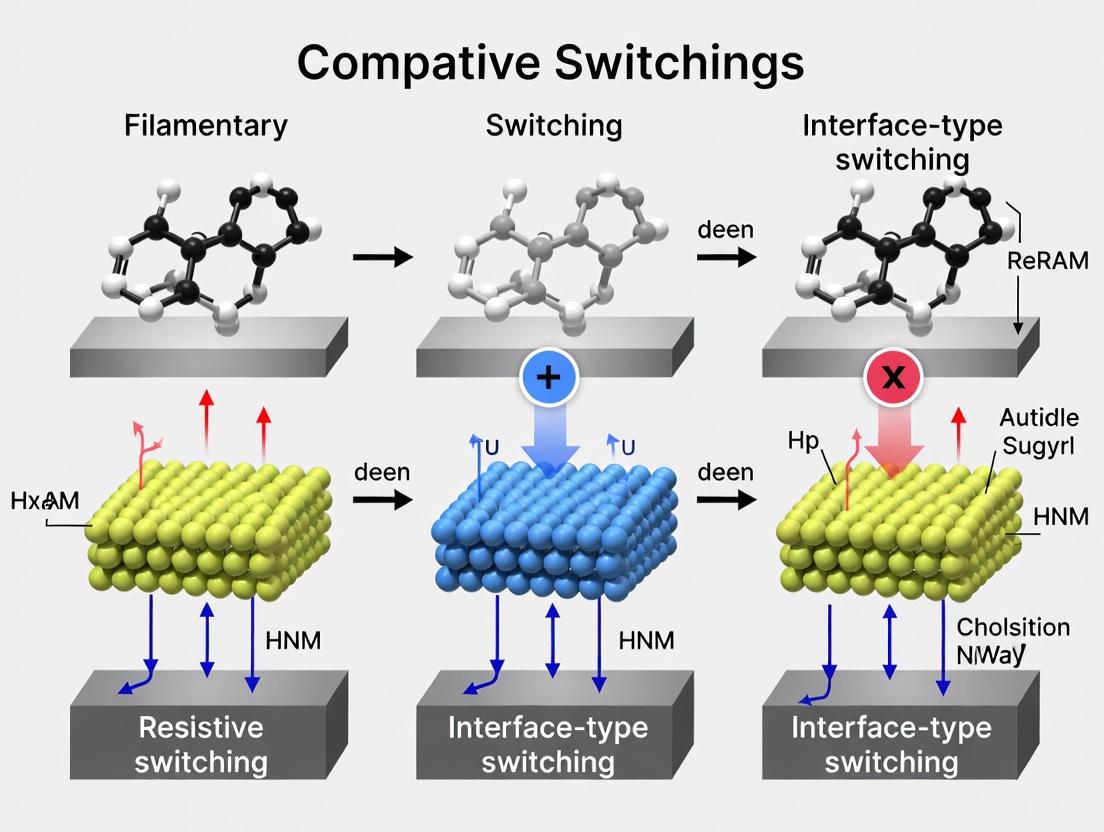

Two predominant physical mechanisms explain resistive switching in ReRAM devices, both involving the formation and rupture of conductive filaments (CFs) within the insulating layer. [4] [5]

Electrochemical Metallization (ECM): Also known as Conductive Bridging RAM (CBRAM), this mechanism involves the movement of metal cations (e.g., Ag⁺, Cu²⁺) from an electrochemically active electrode (e.g., Ag, Cu). These cations migrate through the insulating layer under an electric field and are reduced to form metallic conductive filaments. The RESET process occurs when these filaments are dissolved by a voltage of opposite polarity. [2]

Valence Change Mechanism (VCM): This mechanism relies on the migration of oxygen anions (O²⁻) and the corresponding movement of oxygen vacancies (V_O) within metal oxide insulating layers (e.g., HfO₂, Ta₂O₅, NiO). The formation and rupture of oxygen vacancy-based conductive filaments cause the resistance change. The SET process involves vacancy formation and filament buildup, while the RESET process involves vacancy recombination and filament disruption. [4] [6]

Performance Comparison of ReRAM Technologies

ReRAM is one of several emerging memory technologies competing to overcome the limitations of conventional NAND flash and DRAM. The table below compares ReRAM with other prominent emerging memory technologies based on key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Emerging Memory Technologies

| Technology | Switching Speed | Endurance (Write Cycles) | Retention | Power Consumption | Scalability | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReRAM | ~10 ns [5] | 10⁶ - 10¹² cycles [5] [7] | >10 years [5] | Low (Sub-1V operation demonstrated) [7] | Excellent (<10 nm) [5] | Filamentary (ECM/VCM) |

| PCRAM | ~50 ns | ~10⁸ cycles | ~10 years | Moderate | Moderate | Phase Change |

| MRAM | ~10 ns | >10¹⁵ cycles | >10 years | Low | Good | Magnetic Polarization |

| FeRAM | ~10 ns | ~10¹⁰ cycles | ~10 years | Low | Challenging | Ferroelectric Polarization |

| NAND Flash | ~100 μs | ~10⁵ cycles | ~10 years | High | Challenging below 10 nm [5] | Charge Storage |

ReRAM's commercial market position reflects its technical characteristics. In 2024, the global ReRAM market was valued at approximately USD 786.9 million and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 17.2% to reach USD 3.79 billion by 2034. [8] MRAM currently leads the emerging memory market with a 42% share, followed by PCM at 27%, while ReRAM is expected to capture approximately 18% of the emerging memory market. [5]

Material Platforms and Their Performance

The performance of ReRAM devices heavily depends on the materials used for the insulating switching layer and electrodes. Different material systems yield significantly different device characteristics.

Table 2: Comparison of ReRAM Switching Layer Materials and Performance

| Material System | Switching Type | SET/ RESET Voltage | Endurance (Cycles) | Retention | ON/OFF Ratio | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfO₂-based [6] [9] | VCM (Bipolar) | ~2-3 V / ~-1.5-2 V | >10⁶ | >10 years | 10-1000 | CMOS compatibility, excellent scalability |

| NiO-based [6] [3] | VCM (Bipolar/Unipolar) | ~2-5.4 V / ~-2.9 V [3] | >400-10⁷ | ~10³ sec - 10 years | 10-1000 | Forming-free operation, flexible compatibility |

| TaOₓ-based [6] | VCM (Bipolar) | ~1-2 V / ~-1-2 V | >10¹⁰ | >10 years | 10-100 | High endurance, fast switching |

| TiO₂-based [6] | VCM (Bipolar) | ~2-3 V / ~-1-2 V | >10⁶ | >10 years | 10-100 | Good uniformity, well-studied material |

| CBRAM (Cu/SiO₂) [5] [7] | ECM (Bipolar) | <1 V / ~-0.5 V | 10⁵-10⁷ | >10 years | 100-10000 | Ultra-low power, high ON/OFF ratio |

Metal oxides dominate the ReRAM material landscape, with oxide-based devices retaining 46.3% market share in 2024. [7] Hafnium oxide (HfO₂) is particularly prominent due to its compatibility with CMOS processes and excellent switching properties. [6] Recent research demonstrates that HfO₂ treated with H-plasma shows increased capacitance and conductance quantization, beneficial for in-memory computing applications. [9] Nickel oxide (NiO) offers advantages for flexible electronics, with demonstrated bipolar resistive switching in Ti/NiO/AZO/PET structures with SET voltage ≈ 5.4 V and RESET voltage ≈ -2.9 V. [3]

Experimental Protocols and Characterization Methods

Device Fabrication and Measurement

A typical ReRAM device fabrication and characterization workflow involves several critical steps to ensure reproducible performance and accurate measurement of switching parameters.

Detailed Fabrication Protocol for Flexible NiO-based ReRAM [3]:

- Substrate Preparation: Use polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate for flexibility.

- Bottom Electrode Formation: Deposit aluminum-doped zinc oxide (AZO) layer (~70 nm) via spray coating as a transparent conductive electrode.

- Switching Layer Deposition: Deposit nickel oxide (NiO) thin film (~130 nm) using RF magnetron sputtering with a NiO target, argon environment, pressure of 10⁻² mbar, and applied power of 100 W.

- Top Electrode Deposition: Deposit titanium (Ti) top electrode (~50 nm) using e-beam evaporation through a shadow mask in a vacuum of 5 × 10⁻⁶ mbar.

Electrical Characterization Method [2] [3]:

- Use a semiconductor parameter analyzer (e.g., Keithley 2400 source meter) with a probe station.

- Apply voltage sweeps in the sequence: 0 V → +6 V → 0 V → -6 V → 0 V.

- Implement a compliance current (typically 1 mA) during SET operation to prevent permanent device breakdown.

- Measure current-voltage (I-V) characteristics to identify SET voltage (VSET), RESET voltage (VRESET), and resistance states.

- Perform endurance testing through repeated SET/RESET cycling.

- Conduct retention tests by programming devices and monitoring state retention over time.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

In-situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [2]:

- Enables real-time observation of conductive filament formation and dissolution during resistive switching.

- Reveals dynamic processes of ion migration and redox reactions at nanoscale resolution.

- Overcomes limitations of static ex situ TEM characterization by capturing filament evolution dynamics.

Capacitance Measurements [9]:

- Monitor capacitance changes in MIM structures during switching operations.

- H-plasma treated HfO₂ devices show capacitance increase from 3.904 to 3.917 pF/μm² with applied pulse widths.

- Provides insights into dielectric constant modulation due to oxygen vacancy migration.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ReRAM Development

| Material/Equipment | Function | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Oxides | Resistive switching layer | HfO₂, TiO₂, TaOₓ, NiO, ZnO [6] | HfO₂ offers CMOS compatibility; NiO enables forming-free operation [3] |

| Electrode Materials | Electrical contact formation | Ti, Pt, Ag, Cu, AZO (Al-doped ZnO) [3] | Active electrodes (Ag, Cu) for ECM; inert electrodes (Pt, Ti) for VCM; AZO for transparent flexible devices |

| Deposition Systems | Thin film fabrication | RF sputtering, ALD, e-beam evaporation [3] | ALD for conformal ultra-thin films; sputtering for metal oxides; e-beam for electrodes |

| Characterization Tools | Performance analysis | Semiconductor parameter analyzer, in-situ TEM [2] [3] | Keithley 2400 for I-V curves; in-situ TEM for real-time filament observation |

| Substrate Materials | Device support | Silicon wafers, PET for flexibility [3] | PET enables flexible electronics with bending radii of 10-15 mm |

| Metallic Dopants | Performance enhancement | Various transition metals [6] | Improves endurance, retention, and switching uniformity |

Applications and Future Research Directions

ReRAM technology demonstrates significant potential beyond conventional memory applications, particularly in emerging computing paradigms:

Neuromorphic Computing: ReRAM's analog switching capability and synaptic behavior make it ideal for artificial neural networks. Its ability to mimic synaptic weight plasticity enables efficient in-memory computing, overcoming von Neumann architecture limitations. [8] [3]

Edge AI and IoT Devices: ReRAM's low power consumption (sub-1V operation) and non-volatility are crucial for battery-powered edge devices. The technology supports on-device inference and learning with minimal energy requirements. [8] [1]

Flexible Electronics: Transparent conductive oxide electrodes (e.g., AZO) combined with flexible substrates (e.g., PET) enable bendable memory for wearable electronics and smart textiles. [3] Devices maintain stable switching parameters under bending conditions with radii of 10-15 mm.

In-Memory Computing: ReRAM crossbar arrays can perform matrix multiplication and vector operations directly within memory, drastically reducing data transfer bottlenecks in AI workloads. [7]

Future research priorities include improving device uniformity and reliability, reducing operational variability, enhancing endurance characteristics, developing effective selector devices, and optimizing integration with CMOS processes. [5] Material engineering focusing on "perfect imperfections" in transition metal oxides shows particular promise for enhancing switching dynamics. [3]

Electrochemical Metallization (ECM) represents a fundamental resistive switching mechanism where conductive filament formation and dissolution through active metal ion migration enables non-volatile memory operation. As a cornerstone technology for Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM), ECM cells operate through the voltage-induced movement of cations from an electrochemically active electrode (typically Ag or Cu) through a solid electrolyte layer, forming conductive bridges that switch the device between low and high resistance states [2]. This mechanism has attracted significant research attention due to its potential for neuromorphic computing, low-power logic circuits, and artificial intelligence hardware that can overcome the von Neumann bottleneck [10] [2].

Within the broader landscape of resistive switching mechanisms, ECM stands in contrast to the Valence Change Mechanism (VCM), which relies on the migration of anion vacancies (typically oxygen vacancies) and subsequent modulation of Schottky barrier heights at metal-oxide interfaces [4] [11]. While VCM devices typically use inert electrodes like Pt or Pd with ohmic counter electrodes, ECM cells fundamentally require an electrochemically active electrode (Ag, Cu) that provides mobile cations, paired with an inert counter electrode (Pt, Au) [2] [11]. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for researchers selecting appropriate mechanisms for specific memory and computing applications.

Comparative Analysis of Resistive Switching Mechanisms

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between ECM, VCM, and emerging FCM mechanisms

| Parameter | ECM | VCM | FCM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switching Species | Active metal cations (Ag⁺, Cu⁺) | Anions (O²⁻) / oxygen vacancies | Both cation and anion species |

| Active Electrode | Electrochemically active (Ag, Cu) | Inert (Pt, Pd) with high work function | Ohmic electrodes (Hf, Ta, Zr) |

| Filament Nature | Metallic (Ag, Cu) | Oxygen vacancy-rich region | Nanoscale conduction channels with variable oxidation states |

| Key Driving Force | Electrochemical redox reactions | Electric field-driven ion migration | Localized electrochemical redox reactions |

| Typical SET Polarity | Positive on active electrode | Positive on active electrode | Negative bias (c8w switching) |

| Interface Requirement | Ohmic contacts | One Schottky contact essential | Dual ohmic contacts |

| Representative Structure | Ag/CrPS₄/Au [10] | Pt/Ta₂O₅/Ta [11] | Hf/Ta₂O₅/Ta [11] |

Table 2: Performance metrics across different material platforms

| Material System | ON/OFF Ratio | Endurance (Cycles) | Retention | Operating Voltage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D CrPS₄-based ECM | >10³ | >10⁴ | >10⁴ s | ~1 V | [10] |

| Halide Perovskite ECM | 10³-10⁵ | Varies by structure | Varies by structure | 0.5-2 V | [12] [13] |

| Ta₂O₅-based VCM | >10² | ~10⁶ | >10 years | 1-2 V | [11] |

| Ta₂O₅-based FCM | >10³ | >10⁷ | >10 years | ~1.5 V | [11] |

| HfO₂-based VCM | 10-100 | ~10¹⁰ | >10 years | 1-3 V | [4] |

The comparative analysis reveals that ECM mechanisms typically leverage the high conductivity of metallic filaments (Ag, Cu) to achieve large ON/OFF ratios, while VCM systems benefit from complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) compatibility and potentially higher endurance [4] [11]. The emerging Filament Conductivity Change Mechanism (FCM) represents an innovative approach that combines aspects of both ECM and VCM, utilizing dual ohmic contacts to reduce physicochemical complexity while enabling both binary and analog switching [11].

Experimental Methodologies in ECM Research

Device Fabrication Protocols

The foundational Ag/CrPS₄/Au cross-point device architecture exemplifies standard ECM fabrication methodology. Single-crystalline CrPS₄ is grown from high-purity Cr, P, and S powders using chemical vapor transport, then mechanically exfoliated and transferred onto pre-patterned bottom Au electrodes (3 μm width) on SiO₂/Si substrates [10]. The active Ag top electrodes (~110 nm thickness, 3 μm width) are deposited via electron-beam evaporation following electron-beam lithography patterning and lift-off processes, creating well-defined metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structures [10]. This approach ensures clean interfaces and controlled device geometry essential for reproducible ECM operation.

For halide perovskite-based ECM devices, fabrication often incorporates specialized interface engineering. As demonstrated in 2D/3D halide perovskite heterostructures, a 2D perovskite layer can be introduced to efficiently prevent Ag ion migration into the 3D perovskite film and control the rupture of Ag conductive filaments, substantially enhancing device endurance [14]. This approach highlights the critical role of interface design in modulating ion migration kinetics—a key consideration for ECM device optimization.

Electrical Characterization Standards

Comprehensive electrical characterization forms the cornerstone of ECM mechanism validation. Standard protocols involve obtaining current-voltage (I-V) curves by sweeping DC bias voltages between top and bottom electrodes using semiconductor parameter analyzers (e.g., Agilent 4156B), with the inert electrode typically grounded [10]. During SET switching (transition to Low Resistance State, LRS), current compliance (CC) is critical to prevent permanent device breakdown [2]. For bipolar switching characteristics of ECM cells, positive bias applied to the active electrode facilitates cation migration and filament formation, while reversal to negative bias induces filament dissolution through electrochemical processes assisted by Joule heating, resetting the device to High Resistance State (HRS) [10] [2].

Endurance testing involves continuous cycling between resistance states (typically 10³-10¹⁰ cycles depending on material system), while retention measurements assess non-volatility by monitoring state stability over time (seconds to years at elevated temperatures) [2] [4]. These standardized metrics enable direct comparison across different ECM material systems and architectures.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) provide critical direct evidence of filament configurations in various resistance states. Sample preparation involves creating wedge-shaped specimens through the backside milling method using dual-beam focused ion beam (FIB) systems with Ga⁺ ions at 30 keV [10]. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) and high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging enable visualization of filament morphology and electrode/electrolyte interfaces, while EDS mapping confirms the elemental composition of filaments and their spatial distribution [10] [2].

In situ TEM techniques represent a significant advancement, enabling real-time observation of dynamic filament formation and dissolution processes during resistive switching, overcoming limitations of static ex situ observations [2]. This approach has revealed various filament growth modes and structures, providing insights into the kinetic parameters governing ion migration and redox reactions [2]. Complementary computational studies using density functional theory (DFT) calculations and kinetic Monte Carlo simulations further elucidate atomistic migration mechanisms, energy barriers, and vacancy formation energies critical to ECM operation [10] [12].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ECM mechanism investigation

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials Toolkit

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for ECM device research

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in ECM Devices | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Electrodes | Ag, Cu, Ni, and their alloys [11] | Source of mobile cations for filament formation | High electrochemical activity, suitable redox properties |

| Inert Electrodes | Pt, Au, Pd [10] [11] | Electron injection/extraction without participation in ion migration | High work function, chemical stability |

| 2D Solid Electrolytes | CrPS₄, other TMPSₓ materials [10] | Ion transport medium with confined migration pathways | Two-dimensionally confined properties, van der Waals gaps |

| Halide Perovskite Electrolytes | MAPbBr₃, CsSnI₃, 2D/3D heterostructures [12] [14] | Switching layer with defect-mediated ion migration | Exceptional ion mobility, defect tolerance |

| Oxide Electrolytes | Ta₂O₅, HfO₂, TiO₂, Al₂O₃ [2] [11] | Conventional switching materials for comparison | CMOS compatibility, controlled oxygen vacancy density |

| Characterization Tools | TEM/EDS, In Situ TEM, DFT Calculations [10] [2] | Mechanism elucidation and filament visualization | Atomic-resolution capability, real-time observation |

The selection of active electrode material significantly influences ECM dynamics, with Ag and Cu being predominant choices due to their suitable electrochemical properties and mobility in various solid electrolytes [11]. Recent studies have explored traditionally "inert" metals like Pd in specific matrix materials such as sputtered SiOₓ, where Pd cation transport enables reversible switching—expanding the design space for ECM devices [15].

Solid electrolyte materials dictate ion transport characteristics and filament stability. Two-dimensional layered materials like CrPS₄ offer confined migration pathways that can potentially enhance switching uniformity [10], while halide perovskites demonstrate exceptional ion mobility but require interface engineering for stability [14]. Oxide electrolytes remain widely studied due to their CMOS compatibility and well-understood properties [2] [11].

Diagram 2: Material selection strategy for ECM device development

Future Perspectives and Applications

ECM technology is evolving beyond binary non-volatile memory toward multifunctional neuromorphic and in-memory computing applications. The filament conductivity change mechanism (FCM) represents an innovative approach that combines advantages of both ECM and VCM, demonstrating ultra-stable binary and analog switching, broad voltage stability windows, high temperature stability, and improved endurance [11]. These characteristics enable applications in continual learning systems that overcome catastrophic forgetting problems in conventional deep neural networks [11].

Emerging material platforms including engineered 2D/3D halide perovskite heterostructures [14] and single-crystalline 2D layered materials [10] offer new pathways to control ion migration and filament dynamics. Interface engineering strategies—such as incorporating appropriate capping layers to prevent electrode passivation while maintaining ohmic contacts—continue to address stability challenges in practical ECM device implementation [11]. As fundamental understanding of nanoscale electrochemical processes advances, ECM-based memristive systems are poised to play increasingly important roles in next-generation computing architectures, hardware security, and intelligent edge devices.

Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM) has emerged as a leading candidate for next-generation non-volatile memory technology, offering advantages such as simple metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure, high switching speed, low power consumption, and high integration density [4] [2]. Among the various operational mechanisms underpinning ReRAM devices, the Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) has attracted significant research interest due to its reliability and potential for neuromorphic computing applications [4] [16]. VCM-based ReRAM operates through the migration of anion vacancies (most commonly oxygen vacancies) within a switching layer, typically a transition metal oxide [4] [17]. This migration alters the local stoichiometry and consequently modulates the electronic transport properties of the material, enabling reversible resistive switching between high resistance states (HRS) and low resistance states (LRS) [2].

The fundamental principle of VCM revolves around the field-driven redistribution of mobile ionic defects, primarily oxygen vacancies (V_O••), and the consequent change in the valence state of the cation sublattice [16] [17]. When an electric field is applied, oxygen vacancies migrate, leading to the formation and rupture of conductive filaments or the modulation of interface barriers. This process is often accompanied by a redox reaction at the electrodes, which serves as a reservoir for oxygen ions [17]. The resulting change in the material's resistance is non-volatile, making it suitable for data storage. The dynamics of oxygen vacancies—their formation, migration, and interaction with the host lattice—are therefore critical to the performance and reliability of VCM-based ReRAM devices [18]. Understanding these dynamics provides the foundation for comparing VCM with other resistive switching mechanisms and guides the design of future memory technologies.

Comparative Analysis of VCM Performance and Characteristics

Key Performance Metrics Across Material Systems

The performance of VCM-based ReRAM is highly dependent on the choice of materials for the switching layer and electrodes. Different material systems yield varying switching parameters, which directly influence device suitability for specific applications. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics reported for various VCM-based ReRAM devices.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of VCM-Based ReRAM Devices Using Different Material Systems

| Switching Layer / Structure | Resistance Ratio (R OFF/RON) | Set Voltage (V SET) | Reset Voltage (V RESET) | Endurance (Cycles) | Retention | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ErMnO3 Polymorphs [16] | ~10⁵ | ~ -2.07 V | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ultra-low RON (~10 Ω); Phase boundary engineering |

| NiO on AZO/PET [3] | >10² | ~ 5.4 V | ~ -2.9 V | >400 | ~10³ s | Flexible, forming-free, transparent |

| LSMO Thin Films [17] | Multiple distinct states | N/A | N/A | Excellent reproducibility | N/A | Three reversible resistance states; Structural phase transition |

VCM vs. ECM: A Fundamental Mechanism Comparison

To objectively evaluate VCM, it must be contrasted with the other primary resistive switching mechanism: the Electrochemical Metallization Mechanism (ECM). While both operate in a MIM structure and involve ion migration, their fundamental principles and characteristics differ significantly.

Table 2: Comparison between Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) and Electrochemical Metallization Mechanism (ECM)

| Feature | Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) | Electrochemical Metallization Mechanism (ECM) |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Species | Anions (e.g., Oxygen, O²⁻) and Anion Vacancies (V_O••) [4] [17] | Cations from active electrode (e.g., Ag⁺, Cu²⁺) [2] |

| Filament Type | Oxygen vacancy-based conductive filament [16] [17] | Metallic filament (e.g., Ag, Cu) [2] |

| Typical Electrodes | Inert metals (e.g., Pt, TiN, Au) [16] [3] | Active metal (e.g., Ag, Cu) and inert metal (e.g., Pt, W) [19] [2] |

| Switching Polarity | Bipolar [16] [3] | Bipolar (primarily) [2] |

| Key Driving Force | Migration of oxygen vacancies under electric field, often coupled with Joule heating [17] | Electrochemical redox reactions and field-driven cation migration [2] |

| Material Systems | Transition metal oxides (e.g., HfO₂, Ta₂O₅, SrTiO₃, ErMnO₃) [4] [16] | Solid electrolytes (e.g., GeS₂, GeOx, Ta₂O₅) with active electrodes [19] |

The choice between VCM and ECM depends on the application requirements. VCM devices, utilizing inert electrodes, often demonstrate better endurance and higher integration density due to the stability of the electrodes [4]. The ECM mechanism, while enabling very low power operation, can face challenges with filament stability and requires the integration of electrochemically active metals [19] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Probing VCM

In Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for Direct Observation

Objective: To directly observe the atomic-scale dynamics of oxygen vacancy migration and the resulting structural phase transitions in real-time. Protocol Details:

- Sample Fabrication: Prepare a cross-sectional TEM sample featuring the ReRAM stack, typically a thin film (e.g., 20 nm La₂/₃Sr₁/₃MnO₃ or LSMO) epitaxially grown on a conductive substrate (e.g., Nb-doped SrTiO₃) [17].

- In Situ Electrical Biasing: Mount the sample on a specialized TEM holder with a piezo-controlled metal probe. Bring the electrically grounded probe into contact with the film surface, creating a nanoscale contact area (~30 nm diameter). Apply a series of short triangular voltage pulses (e.g., 100 ms duration) to the substrate [17].

- Simultaneous Imaging and Electrical Measurement: While applying voltage pulses, use high-resolution Scanning TEM (STEM) to image the lattice structure. Simultaneously, continuously monitor the electrical resistance of the sample. This correlative approach directly links structural changes to resistance states [17].

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Complement imaging with Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) to probe changes in the oxidation state and local oxygen concentration within the switching layer, providing chemical evidence for oxygen vacancy migration [17].

Key Insights from Protocol: This methodology has been pivotal in demonstrating that resistive switching in VCM systems is driven by the reversible horizontal migration of oxygen vacancies within the film, leading to uniform structural phase transitions (e.g., from perovskite to brownmillerite structure in LSMO) rather than the formation of nanoscale filaments alone [17].

Electrical Characterization of Bipolar Resistive Switching

Objective: To electrically characterize the switching parameters, endurance, and retention of VCM-based ReRAM devices. Protocol Details:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a metal-insulator-metal (MIM) capacitor structure. For example, deposit a switching layer (e.g., NiO, ErMnO₃) via RF sputtering or pulsed laser deposition between inert top and bottom electrodes (e.g., Pt, Ti, AZO) [16] [3].

- Current-Voltage (I-V) Sweeping: Use a semiconductor parameter analyzer to perform voltage sweeps. A typical bipolar sweep sequence is: 0 V → +Vmax → 0 V → -Vmax → 0 V. A current compliance (CC) is set during the SET process to prevent irreversible hard breakdown [2] [3].

- Parameter Extraction: From the I-V characteristics, determine key metrics:

- Endurance and Retention Testing: Cycle the device repeatedly between HRS and LRS to test endurance (number of stable switching cycles). Measure retention by applying a small read voltage to each state over time (e.g., 10³ seconds) to ensure non-volatility [3].

Key Insights from Protocol: This standard electrical testing reveals the forming-free behavior, operating voltages, and stability of the device. Analysis of the I-V curves in different regions (e.g., ohmic conduction, Space Charge Limited Conduction - SCLC) provides insight into the dominant conduction mechanisms in the HRS and LRS, which are often linked to the configuration of oxygen vacancies [3].

Visualization of VCM Dynamics and Workflows

Oxygen Vacancy Dynamics in VCM Switching

The following diagram illustrates the core physical processes of the Valence Change Mechanism, driven by oxygen vacancy dynamics.

Experimental Workflow for VCM Analysis

This diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for characterizing VCM-based ReRAM devices, from fabrication to advanced analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental study of VCM relies on a suite of specialized materials, deposition tools, and characterization instruments. The following table details the essential components of the research toolkit for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for VCM ReRAM Investigation

| Category | Item / Technique | Specific Examples | Primary Function in VCM Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switching Layer Materials | Transition Metal Oxides | HfO₂, Ta₂O₅, TiO₂, NiO, SrTiO₃, La₂/₃Sr₁/₃MnO₃ (LSMO), ErMnO₃ [4] [16] [17] | Host matrix for oxygen vacancy generation and migration; determines switching characteristics. |

| Electrode Materials | Inert Electrodes | Pt, Ti, TiN, Au, Al-doped ZnO (AZO) [16] [3] | Provide electrical contact without actively participating in redox reactions; act as oxygen ion reservoirs. |

| Fabrication Equipment | Thin Film Deposition | RF Sputtering, Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD), Thermal Evaporation [16] [3] | Precisely deposit thin, uniform layers of electrode and switching materials. |

| Structural Characterization | Microscopy & Diffraction | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Raman Spectroscopy [16] [3] | Analyze film morphology, crystallinity, phase composition, and polymorph distribution. |

| Electrical Characterization | Semiconductor Analyzer | Keithley 2400 Series Source Meter [3] | Perform precise I-V, endurance, and retention measurements with current compliance. |

| Advanced In Situ Analysis | Transmission Electron Microscopy | in situ TEM/STEM, Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) [2] [17] | Directly observe oxygen vacancy dynamics and structural transitions in real-time under bias. |

This guide has provided a comprehensive comparison of the Valence Change Mechanism, highlighting its fundamental principles, performance metrics across material systems, and direct contrast with the Electrochemical Metallization Mechanism. The detailed experimental protocols and visualization of oxygen vacancy dynamics offer a roadmap for researchers to probe and validate VCM in ReRAM devices. The consistent observation of oxygen vacancy-driven structural and resistive transitions, as made possible by advanced in situ techniques like TEM, underscores the critical role of anion dynamics in this mechanism [17]. The ongoing development of diverse material platforms—from traditional transition metal oxides to novel polymorphic and flexible systems [16] [3]—continues to expand the potential of VCM-based memory. This progress positions VCM-ReRAM as a key technology not only for high-density, non-volatile memory but also for the realization of energy-efficient neuromorphic computing systems.

Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM) has emerged as a promising technology for next-generation non-volatile memory and neuromorphic computing, owing to its simple metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure, fast switching speed, low power consumption, and excellent scalability [4] [6]. The fundamental operation of ReRAM devices relies on electrically induced resistance switching between high-resistance states (HRS) and low-resistance states (LRS). Among the various physical mechanisms that govern this switching behavior, the Thermochemical Mechanism (TCM) plays a crucial role, particularly in the formation and stability of conductive filaments (CFs) that bridge the electrodes through the insulating oxide layer [20] [21].

The TCM is distinguished from other prominent mechanisms such as the Electrochemical Metallization Mechanism (ECM) and Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) by its primary driving force. While ECM involves the oxidation and reduction of active electrode metals, and VCM is primarily driven by electric field-induced migration of oxygen vacancies, TCM is dominated by Joule heating-induced effects that facilitate the formation and rupture of conductive filaments through thermal processes [21]. In TCM-based devices, the local temperature increase caused by Joule heating under an applied electric field enables the thermally activated reduction of the metal oxide layer, leading to the creation of a conductive channel composed of oxygen vacancies or metal cations. The stability of this filament is critically dependent on the precise control of Joule heating, which, if uncontrolled, can lead to undesirable variability in switching parameters and device performance degradation [20] [22].

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of the thermochemical mechanism against other resistive switching mechanisms, with particular emphasis on the role of Joule heating in filament stability. We present experimental data from diverse material systems, analyze methodologies for characterizing thermal effects, and discuss material design strategies to control Joule heating for enhanced device performance.

Comparative Analysis of Resistive Switching Mechanisms

Fundamental Operating Principles

ReRAM devices operate through different physical mechanisms depending on the materials system, electrode configuration, and switching conditions. The table below compares the three primary resistive switching mechanisms:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Resistive Switching Mechanisms in ReRAM

| Feature | Thermochemical Mechanism (TCM) | Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) | Electrochemical Metallization (ECM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Driving Force | Joule heating | Electric field | Electric field + electrochemical reactions |

| Filament Composition | Oxygen vacancies or metal cations | Oxygen vacancies | Active metal ions (Ag, Cu) |

| Key Processes | Thermal reduction, phase change | Oxygen ion/vacancy migration | Metal oxidation/redox, cation migration |

| Temperature Dependency | Strong (thermal activation) | Moderate | Weak to moderate |

| Typical Materials | NiO, TaOx, HfO2 | TaOx, HfOx, TiO2 | Ag/chalcogenides, Cu/solid electrolytes |

| Switching Polarity | Unipolar (voltage polarity-independent) | Bipolar (voltage polarity-dependent) | Bipolar (voltage polarity-dependent) |

| Filament Stability Challenge | Thermal runaway during reset | Interface reactions | Overgrowth into counter electrode |

The Role of Joule Heating in TCM Operation

In TCM-based ReRAMs, Joule heating is the predominant factor governing both the SET (transition to LRS) and RESET (transition to HRS) processes. During the forming or SET process, applied voltage creates a conductive filament through the insulator. The subsequent current flow through this narrow filament generates significant localized heating due to the substantial current density, which can reach temperatures sufficient to cause thermal reduction of the oxide material or facilitate ionic movement [22] [21].

The RESET process in TCM devices is particularly dependent on Joule heating effects. As the table below illustrates, the rupture of the conductive filament occurs when the local temperature reaches a critical point that enables oxidation of the filament material or atomic rearrangement through thermal diffusion. This is in contrast to VCM devices, where the reset process is primarily driven by the reverse electric field that pushes oxygen vacancies away from the filament or attracts oxygen ions back into the filament region [22] [21].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of Joule Heating Effects in Different ReRAM Systems

| Material System | Device Structure | Switching Type | Key Findings on Joule Heating Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlOx | Pt/AlOx/ITO | Unipolar & Bipolar | Unipolar switching disappears at 40 K, indicating thermal mechanism essential for RESET | [22] |

| TaOx/HfO2 | Bilayer with inert electrodes | Bipolar (TCM features) | MD simulations show thermally activated oxygen vacancy generation stabilizes filament growth | [21] |

| NiO | Ni/HfO2/Si(n+) | Unipolar | Current-controlled operation reduces variability by controlling Joule heating | [23] |

| TaOx | ITO/TaOx/NiOx/Al | Bipolar | Interface engineering suppresses abrupt filament rupture by modulating thermal effects | [24] |

Molecular dynamics simulations of TaOx/HfO2-based ReRAMs have provided atomistic insights into the role of thermal effects in filament formation. These simulations reveal that while electric fields initiate ionic displacement, the filament growth during electroforming is primarily attributed to a localized thermally-activated mechanism [21]. Specifically, once a voltage threshold is exceeded, the generation of oxygen vacancy defects becomes stabilized by local electric fields near the nucleated filament, with Joule heating accelerating this process by providing the necessary thermal energy for defect generation and aggregation.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Joule Heating Effects

Temperature-Dependent Electrical Characterization

The most direct approach for investigating the role of Joule heating in TCM devices involves temperature-dependent electrical characterization. By measuring current-voltage (I-V) characteristics across a wide temperature range, researchers can isolate thermal effects from electric field effects. In a notable study on AlOx-based RRAM, devices exhibited dramatically different behavior when cooled to cryogenic temperatures (40 K) [22]. The complete disappearance of unipolar resistive switching at low temperatures provided compelling evidence that Joule heating is essential for the RESET process in unipolar operation. Meanwhile, bipolar switching persisted but transformed from abrupt to gradual reset behavior, indicating that Joule heating assists in filament rupture even in bipolar mode [22].

The analysis of conduction mechanisms through I-V characterization at various temperatures further reveals the influence of thermal effects. In TCM-dominated devices, the LRS typically exhibits ohmic conduction (I∝V) due to the metallic or highly conductive nature of the filament, while the HRS often follows Space-Charge-Limited Conduction (SCLC) or Schottky emission patterns [24] [22]. The temperature dependence of these conduction mechanisms provides indirect information about the role of Joule heating in filament stability.

Current vs. Voltage Control Methodologies

The fundamental difference between current-controlled and voltage-controlled operation provides important insights into Joule heating management in TCM devices. Experimental studies on Ni/HfO2/Si(n+) structures have demonstrated that current-controlled switching significantly reduces variability in resistance states compared to voltage-controlled operation [23]. This improvement stems from the direct control over Joule heating (P = I²R) afforded by current programming, which enables more precise thermal management during the critical filament formation and rupture processes [23].

Voltage-controlled switching, in contrast, allows current—and consequently Joule heating—to vary dramatically based on the filament's instantaneous resistance state. This often leads to uncontrolled thermal runaway during RESET, causing abrupt filament rupture and consequently higher cycle-to-cycle variability [23]. The comparison between these operational methodologies highlights the critical importance of controlled Joule heating for stable TCM operation.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Advanced structural and chemical characterization techniques provide direct evidence of Joule heating effects on filament stability. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) combined with Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) has been employed to analyze the structural transformation in multilayer RRAM devices such as Pt/AlOx/ZnO/Ti [25]. These techniques have revealed distinct filament morphologies across different oxide layers, with continuous oxygen vacancy filaments in ZnO and discontinuous oxygen-deficient regions in AlOx [25]. The variation in filament structure directly influences current confinement and thus localized Joule heating, ultimately determining power consumption and switching stability.

Table 3: Methodologies for Investigating Joule Heating in TCM ReRAMs

| Technique | Application | Key Insights | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Dependent I-V | Electrical characterization across temperature ranges | Identifies thermal activation energies; distinguishes thermal from field-driven effects | Does not directly measure filament temperature |

| Current-Control Methodology | Comparing current vs. voltage programming | Demonstrates improved uniformity with controlled Joule heating | Requires specialized instrumentation |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Atomistic modeling of filament dynamics | Reveals temperature-driven ion migration and vacancy generation | Computationally intensive; simplified models |

| STEM/EELS Analysis | Nanoscale structural and chemical characterization | Direct observation of filament morphology and composition | Post-mortem analysis; challenging in operando |

Material and Interface Engineering for Thermal Management

Interface Engineering Strategies

Interface engineering has emerged as a powerful approach to modulate Joule heating effects and improve filament stability in TCM devices. The introduction of engineered interfaces between oxide layers and electrodes can significantly alter the thermal and electrical profiles during switching operations. In one notable study, researchers inserted a thin NiOx layer between TaOx and the top electrode in an Al/TaOx/ITO device [24]. This interface barrier successfully suppressed the uncontrolled rupture of filaments by confining their formation and rupture throughout the entire bulk structure under critical bias setups [24].

The physical mechanism behind this improvement was identified as a combination of space-charge-limited conduction (SCLC) dominating the SET process and Schottky emission dominating under reverse bias. The NiOx/TaOx interface barrier effectively redistributed the electric field and associated Joule heating, leading to more controlled filamentary switching with improved endurance and uniformity [24]. The cumulative distribution of switching voltages showed remarkable concentration in devices with the NiOx interface layer, with SET voltages ranging from 0.64 to 0.78V and RESET voltages from -0.68 to -0.88V, compared to much broader distributions (1.3-4.9V for SET, -1.7 to -5.0V for RESET) in control devices without the interface layer [24].

Bilayer Oxide Structures

Bilayer oxide structures represent another effective strategy for managing Joule heating and improving filament stability in TCM devices. These structures typically combine two different oxide materials with complementary properties to better control the formation and rupture of conductive filaments. For instance, Pt/AlOx/ZnO/Ti RRAM devices have demonstrated excellent performance characteristics, including forming-free operation, self-compliance, and low power consumption (0.586 nW for SET and 0.596 nW for RESET) [25].

In this architecture, the switching mechanism involves the formation of continuous oxygen vacancy filaments in the ZnO layer, while the AlOx layer contains discontinuous oxygen-deficient regions that enable electron hopping conduction [25]. This multi-functional conducting filament system naturally restricts current levels, thereby controlling Joule heating and reducing power consumption. The current confinement in the AlOx layer occurs through hopping distances of approximately 1.5 nm, as evidenced by EELS mapping and fitting results [25]. Such controlled current flow directly modulates the localized Joule heating, preventing thermal runaway and enabling more stable switching behavior over thousands of cycles.

Material Selection Criteria

The selection of appropriate oxide materials is crucial for optimizing TCM operation through Joule heating management. Transition metal oxides such as NiO, TaOx, HfO2, and TiO2 have been extensively investigated for TCM-based ReRAMs, each offering distinct advantages and challenges [6]. The thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, and activation energy for ion migration of these materials directly influence how Joule heating affects filament stability.

Materials with moderate thermal conductivity are often preferred for TCM operation, as they allow sufficient localized heating for filament formation and rupture while preventing excessive heat dissipation that would require higher operating power. Additionally, the oxygen ion mobility and reduction enthalpy of the oxide material determine its susceptibility to thermally driven redox processes that underlie the TCM [21] [6]. By carefully selecting material combinations in bilayer or multilayer structures, researchers can tailor the thermal and electrical properties to achieve optimal TCM switching characteristics with enhanced filament stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Materials and Characterization Tools for Investigating TCM and Joule Heating Effects

| Category | Specific Materials/Tools | Function in TCM Research | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Oxides | TaOx, HfO2, NiO, AlOx, ZnO | Switching layer material exhibiting TCM behavior | TaOx/HfO2 bilayers [21], NiO unipolar devices [23] |

| Electrode Materials | Pt, Ti, ITO, Ni, Al | Inert and active electrodes for MIM structures | Pt top electrode in Pt/AlOx/ZnO/Ti [25] |

| Interface Engineering Layers | NiOx, AlOx | Modulate interfacial barriers and thermal profiles | NiOx in ITO/TaOx/NiOx/Al [24] |

| Characterization Tools | Temperature-dependent I-V, C-AFM, STEM, EELS | Electrical and structural analysis of filament dynamics | STEM/EELS for Pt/AlOx/ZnO/Ti filament visualization [25] |

| Simulation Methods | Molecular Dynamics with CTIP/EChemDID | Atomistic modeling of filament formation and thermal effects | MD simulations of TaOx/HfO2 bilayer [21] |

Comparative Performance Analysis and Future Directions

Performance Metrics Across Mechanisms

The performance advantages and limitations of TCM relative to other switching mechanisms become evident when comparing key device metrics. While TCM-based devices traditionally faced challenges with variability and power consumption due to the stochastic nature of thermally driven filament formation, recent advances in interface and material engineering have yielded significant improvements.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflows for investigating Joule heating effects in TCM ReRAM devices, incorporating key methodologies discussed in this review:

Current-controlled operation has demonstrated particular promise for TCM devices, with studies showing both variability reduction and power enhancement compared to voltage-controlled switching [23]. In Ni/HfO₂/Si(n⁺) devices, current sweeps during both SET and RESET processes resulted in more stable resistance states and lower power consumption, as the direct control over current enables more precise management of Joule heating effects [23].

Future Research Directions

Future research on TCM and Joule heating effects should focus on several promising directions. First, the development of advanced thermal management strategies through nanoscale material design could further improve filament stability. This includes the exploration of heterogeneous structures with precisely engineered thermal properties and the implementation of local thermal probes to directly measure temperature distributions in operating devices.

Second, the integration of multiscale modeling approaches combining atomistic simulations with compact models will enhance our understanding of Joule heating effects across different length and time scales. Reactive molecular dynamics simulations have already provided valuable insights into filament formation mechanisms [21], and extending these approaches to include additional material systems and operational conditions will yield further design guidelines for stable TCM operation.

Finally, the exploration of novel material systems beyond conventional transition metal oxides may open new pathways for controlling Joule heating effects. Two-dimensional materials, organic-inorganic hybrids, and phase-change materials offer unique thermal and electrical properties that could be leveraged to develop TCM devices with improved performance characteristics for next-generation memory and neuromorphic computing applications.

The thermochemical mechanism in ReRAM devices presents both challenges and opportunities related to Joule heating effects on filament stability. While uncontrolled thermal effects can lead to variability and reliability issues, properly managed Joule heating provides the fundamental driving force for stable resistive switching in TCM devices. Through interface engineering, bilayer structures, current-control methodologies, and advanced thermal characterization, researchers have made significant progress in harnessing Joule heating for improved device performance.

Comparative analysis with VCM and ECM mechanisms reveals that TCM offers unique advantages for unipolar operation and simplified device integration, though it requires careful thermal management. Future research focusing on nanoscale thermal engineering, multiscale modeling, and novel material systems will further enhance our ability to control Joule heating effects, ultimately enabling the development of high-performance, reliable TCM-based ReRAM devices for next-generation computing applications.

Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM) has emerged as a leading candidate for next-generation non-volatile memory and neuromorphic computing, offering advantages such as simple structure, high speed, low power consumption, and excellent scalability [26] [27]. At the core of ReRAM operation are two fundamental resistive switching modes: unipolar and bipolar. These modes are classified based on how the applied voltage controls the resistance transitions between high-resistance (HRS) and low-resistance states (LRS). While unipolar switching depends only on the voltage magnitude, bipolar switching requires opposite voltage polarities for SET and RESET operations [28]. Understanding the distinct physical mechanisms governing these switching modes is crucial for optimizing device performance for specific applications, from high-density memory to artificial synapses. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of unipolar and bipolar switching modes by examining their operational principles, underlying physical mechanisms, experimental characterization, and material dependencies.

Fundamental Operational Principles

Defining Characteristics and Voltage Polarities

The primary distinction between unipolar and bipolar resistive switching lies in their voltage polarity requirements for resistance transitions:

Unipolar Resistive Switching (URS): The SET (transition to LRS) and RESET (transition to HRS) processes are controlled solely by the magnitude of the applied voltage, independent of its polarity [28]. The same voltage polarity can be used for both operations, though the RESET voltage is typically higher than the SET voltage.

Bipolar Resistive Switching (BRS): The SET and RESET processes require opposite voltage polarities [28]. For instance, a positive voltage might trigger the SET process, while a negative voltage is required for the RESET process, or vice-versa.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Unipolar and Bipolar Switching Modes

| Feature | Unipolar Switching (URS) | Bipolar Switching (BRS) |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage Polarity Dependency | Independent of polarity | Dependent on opposite polarities |

| SET/RESET Mechanism | Voltage magnitude-driven | Voltage polarity-driven |

| Filament Nature | Typically thicker, thermally ruptured | Typically thinner, ion-migration controlled |

| Primary Physical Mechanism | Thermo-chemical filament rupture & formation [29] | Electrochemical ion migration & interface modulation [30] [31] |

| Key Controlling Parameter | Current compliance (for SET) | Voltage polarity & sweep direction |

| Typical I-V Characteristic | Symmetrical (similar shape for both polarities) | Asymmetrical (different shape for opposite polarities) |

| Switching Uniformity | Often less uniform | Generally better uniformity [28] |

| Operational Power | Can require higher RESET power | Typically lower operational power [28] |

Visualizing the Operational Workflow

The fundamental electrical operations for characterizing both switching modes involve applying voltage sweeps and measuring the current response to induce resistance transitions.

Underlying Physical Mechanisms

Unipolar Switching and the Thermo-Chemical Filament Model

Unipolar resistive switching is predominantly explained by the formation and rupture of conductive filaments within the insulating oxide layer via thermo-chemical processes [29]. The switching cycle involves:

Forming and SET Process: An initial high voltage (forming voltage) creates a conductive filament composed of metallic atoms or oxygen vacancies through the insulating layer. After forming, a lower SET voltage can re-establish a conductive filament.

RESET Process: As current flows through the filament in the LRS, Joule heating increases the local temperature. When the current reaches a critical value sufficient to initiate a thermo-chemical reaction (e.g., oxidation of the filament material), the filament ruptures at its weakest point, typically in the center where the temperature is highest [29]. This rupture returns the device to the HRS.

A universal power-law relationship has been observed between the switching power (P) and the switching resistance (R) during the RESET process in unipolar devices: P ∝ R−β, where β is a constant [29]. This universality across different binary metal oxide systems (e.g., NiO, TiO₂, HfO₂) suggests that the RESET operation is governed by a common thermal mechanism where the power required to rupture a filament decreases as the filament resistance increases.

Bipolar Switching and the Electrochemical Mechanism

Bipolar switching operates primarily through an electrochemical mechanism driven by ion migration under an electric field, which is strongly polarity-dependent [30] [31]. The switching cycle involves:

SET Process: Application of one voltage polarity (e.g., positive on the top electrode) drives mobile ions (e.g., oxygen vacancies or metal cations) toward the bottom electrode, forming a conductive filament or modulating the interface barrier, thereby switching the device to the LRS.

RESET Process: Reversing the voltage polarity (e.g., negative on the top electrode) drives the ions back, rupturing the filament or re-establishing the interface barrier, which returns the device to the HRS.

In some bipolar systems, the resistance change is attributed to the modulation of the Schottky barrier at the metal-oxide interface due to the migration of oxygen ions or vacancies, rather than a complete filamentary rupture [31]. The presence of an oxygen scavenging layer (e.g., Ti, Ta) adjacent to the switching oxide is crucial in many bipolar ReRAMs, as it provides a reservoir for oxygen ions, facilitating the redox reactions that control the concentration of oxygen vacancies in the switching layer [31].

Diagram of Physical Mechanisms

The core physical processes differentiating unipolar and bipolar switching mechanisms are illustrated below.

Experimental Characterization and Data

Key Experimental Protocols

Resistive switching characterization primarily relies on direct current (DC) voltage sweep measurements performed using a semiconductor parameter analyzer:

Device Structure: The standard test structure is a Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) capacitor, where the "insulator" is the switching material (e.g., metal oxide) [29] [30].

Forming Operation: A pristine device is initially in a highly resistive state. A one-time, higher voltage "forming" process is required to activate the reversible switching behavior by creating an initial conductive path [29] [32].

DC Sweep Measurement:

- A voltage sweep sequence (e.g., 0 V → +Vmax → 0 V → -Vmax → 0 V) is applied to the top electrode while the bottom electrode is grounded.

- The current is measured continuously. Abrupt changes in current indicate resistive switching events.

- For the SET process, a current compliance is set to prevent permanent device breakdown by limiting the maximum current that can flow upon switching to the LRS [30] [31].

Data Analysis: The current-voltage (I-V) curves are plotted on linear and log-log scales to determine switching parameters (VSET, VRESET, HRS/LRS resistance) and identify conduction mechanisms (Ohmic, Space-Charge-Limited Conduction, etc.) [28].

Comparative Experimental Data

Experimental data from various material systems highlights the distinct electrical characteristics of unipolar and bipolar switching.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Different Material Systems

| Material System | Switching Mode | Key Experimental Observations | Switching Parameters | Cited Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiO, TiO₂, HfO₂ | Unipolar | Universal power-law P ∝ R⁻¹.¹² for RESET; LRS shows metallic conductivity | RESET power decreases with increasing R; Thermo-chemical rupture | [29] |

| Pt/ZnO/TiN | Bipolar | Gradual SET/RESET; Stable endurance (>100 cycles); Multilevel capability | Set voltage: ~0.7 V; Reset voltage: ~ -1.0 V; Self-compliance | [30] |

| Ta/Ta₂O₅/Pt | Bipolar & CRS | Switching mode transition (BRSCRS) with compliance current and Ta thickness | CRS appears at higher C.C. (3 mA) with thin Ta (20 nm) layer | [31] |

| ITO/GOAu/Al | Non-Polar (Both URS & BRS) | Exhibits both unipolar and bipolar switching in the same device | Unipolar VSET: 2.3 V, VRESET: 1.7 V; Bipolar V_SET: -1.6 V | [28] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Materials and Reagents

The performance and switching mode of ReRAM devices are heavily influenced by the choice of materials. The table below details key materials used in the fabrication of ReRAM devices featured in the cited studies.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Resistive Switching Memory Research

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Device |

|---|---|---|

| Switching Oxides | Binary Metal Oxides (NiO, TiO₂, HfO₂, Ta₂O₅, ZnO) [29] [30] [26] | Primary layer where resistive switching occurs; hosts the conductive filament. |

| Oxygen Scavenger/ Reservoir Layers | Ta, Ti [31] | Adjacent layer that getters oxygen from the switching oxide, promoting the formation of oxygen vacancies crucial for bipolar switching. |

| Active Electrodes | Ag, Cu [32] | For CBRAM devices, these electrodes provide metal cations (Ag⁺, Cu⁺) that form the conductive filament. |

| Inert Electrodes | Pt, TiN, ITO [29] [30] [28] | Electrodes that do not readily supply ions; used to probe the switching layer and apply electric field. |

| 2D Materials | Graphene Oxide (GO) [28] | Emerging switching material offering flexibility, tunable oxygen content, and potential for complex switching behaviors like non-polar and complementary switching. |

Application Context and Selection Guidelines

The choice between unipolar and bipolar switching modes depends critically on the target application:

Unipolar Switching has been historically significant, particularly in earlier oxide-based ReRAM. Its simplicity in not requiring polarity reversal can be an advantage in some circuit designs. However, its typically higher RESET power and larger operational variability can be limitations [28].

Bipolar Switching is the predominant mode in modern ReRAM development due to its better uniformity, lower power consumption, faster switching speed, and superior controllability [28]. It is especially suited for:

- High-Density Memory: Its reliability and endurance are key for storage-class memory.

- Neuromorphic Computing: The gradual, analog-like resistance modulation achieved in bipolar switching (e.g., in Pt/ZnO/TiN devices) is ideal for emulating synaptic weights in artificial neural networks [30].

- Multilevel Cell (MLC) Storage: Bipolar devices more readily achieve multiple intermediate resistance states, increasing storage density [30] [26].

Complementary Resistive Switching (CRS), a derived mode from bipolar switching, is specifically designed to mitigate sneak-path currents in crossbar arrays. It connects two bipolar cells anti-serially, ensuring that the combined resistance is always high in the idle state, which is crucial for achieving high-density memory arrays without selector devices [31] [28].

Unipolar and bipolar resistive switching modes are governed by fundamentally different physical mechanisms—thermo-chemical and electrochemical, respectively. This fundamental distinction dictates their operational characteristics, performance metrics, and ultimate application domains. While unipolar switching demonstrates a universal thermal rupture mechanism, bipolar switching offers greater control through field-driven ion migration, making it the leading contender for advanced memory and neuromorphic computing applications. The ongoing research into diverse material systems, from binary metal oxides to graphene oxide and bilayer structures, continues to refine our understanding of these mechanisms and enables the engineering of ReRAM devices with tailored properties for the future of electronics.

Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM) has emerged as a leading contender for next-generation non-volatile memory technology, offering significant advantages in scalability, switching speed, and power consumption compared to conventional flash memory. At the core of ReRAM evaluation lie three fundamental performance metrics: the ON/OFF ratio, which measures the distinguishability between memory states; endurance, which quantifies the device's lifetime; and retention, which defines its data stability over time. These metrics collectively determine the practical viability of ReRAM devices across diverse applications, from embedded memory and storage-class memory to neuromorphic computing and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs).

The performance of ReRAM is intrinsically linked to its resistive switching mechanisms, primarily governed by the formation and rupture of conductive filaments (CFs) within a thin insulating layer sandwiched between two metal electrodes. The most prevalent mechanisms include the Electrochemical Metallization (ECM) mechanism, involving active metal electrode ions (e.g., Ag⁺ or Cu⁺), and the Valence Change Mechanism (VCM), reliant on the migration of oxygen anions (O²⁻) and the consequent redistribution of oxygen vacancies [33] [4]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial, as they directly influence the metrics under discussion, often creating inherent trade-offs that device engineers must navigate.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these key metrics across diverse ReRAM material systems and architectures, presenting consolidated experimental data and the methodologies used to obtain them. By framing this data within the context of resistive switching mechanisms, this analysis aims to provide researchers and development professionals with a clear framework for evaluating ReRAM technologies.

Metric Definitions and Switching Mechanisms

ON/OFF Ratio

The ON/OFF ratio is a critical parameter defined as the ratio between the resistance in the High-Resistance State (HRS) and the Low-Resistance State (LRS). A higher ratio allows for easier and more reliable distinction between logical '0' and '1' states, which is particularly vital for multi-level cell (MLC) storage, where a single cell stores multiple bits of information [34]. The ON/OFF ratio is fundamentally governed by the completeness of conductive filament formation and dissolution. In ECM-based devices, the ratio depends on the robustness of metallic filaments, while in VCM-based devices, it is controlled by the configuration of oxygen vacancy filaments [33] [26].

Endurance

Endurance refers to the number of reliable SET (transition to LRS) and RESET (transition to HRS) cycles a memory device can undergo before failure. It is a direct measure of the device's operational lifetime and is often limited by the degradation of the switching layer or electrodes over repeated cycling. The stochastic nature of filament formation and rupture leads to cycle-to-cycle (C2C) and device-to-device (D2D) variability, which negatively impacts endurance [35] [36]. Optimizing operational conditions, such as using tailored voltage pulses, has been shown to improve endurance by mitigating damage during the filament dissolution process [36].

Retention

Retention describes the ability of a device to maintain its programmed resistance state (either HRS or LRS) over an extended period, typically measured at elevated temperatures to accelerate testing. It is a key indicator of non-volatility. Data retention is challenged by the spontaneous diffusion of ions or oxygen vacancies that constitute the conductive filament, leading to a gradual drift of the resistance state over time [26]. Superior retention ensures data integrity in memory applications, with a common benchmark being stability for 10 years at operating temperatures.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics and Their Definitions

| Metric | Definition | Key Influencing Factors | Ideal Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| ON/OFF Ratio | Ratio of HRS resistance to LRS resistance | Switching mechanism, electrode materials, ON/OFF ratio of the resistive device [35] | > 10³ for MLC operation [37] |

| Endurance | Number of sustained SET/RESET cycles | Filament stability, operational voltage, current compliance [36] | > 10¹⁰ cycles [26] |

| Retention | Data storage duration without degradation | Material stability, filament volatility, operating temperature | > 10 years at 85°C [26] |

Performance Comparison Across Material Systems

ReRAM performance varies significantly based on the choice of switching layer material, electrode materials, and device structure. The following section compares the documented performance of different ReRAM technologies, highlighting how material choices and switching mechanisms influence key metrics.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Different ReRAM Material Systems

| Device Structure | Switching Layer / Mechanism | ON/OFF Ratio | Endurance (Cycles) | Retention (Seconds) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti/Pt/ZnS/Ag [34] | ZnS (Likely ECM) | ~ 5 × 10³ | ~ 2 × 10³ | ~ 6 × 10³ | Multi-level switching (6 states), low variability |

| Pd/HfOx/p-Ge [37] | HfOx (MIS Structure) | > 10⁵ | 2 × 10⁴ (DC sweep) | N/D | Large memory window, low operating power (~1 nW) |

| TiN/HfOx/Pt [37] | HfOx (MIM Structure) | ~ 10³ | N/D | N/D | Standard MIM benchmark, lower ON/OFF ratio |

| Pt/ZnO/TiN [36] | ZnO (VCM) | N/D | 1,053 to 4,300* | N/D | *Endurance improved via pulse optimization |

| Ti/NiO/AZO/PET [3] | NiO (Flexible Device) | N/D | > 400 | ~ 1,000 | Flexible, forming-free, transparent |

The data reveals several key trends. First, the metal-insulator-semiconductor (MIS) structure used in the Pd/HfOx/p-Ge device achieves a significantly larger ON/OFF ratio (>10⁵) compared to its metal-insulator-metal (MIM) counterpart based on HfOx (~10³). This is attributed to a more complete rupture of the conductive filament in the MIS structure, leading to a lower HRS current [37]. Second, material choice directly impacts performance. The ZnS-based device demonstrates a balanced combination of a high ON/OFF ratio, decent endurance, and multi-level capability, which is linked to its intrinsic defects facilitating stable filamentary switching [34]. Third, operating conditions are critical. Research on Pt/ZnO/TiN devices shows that optimizing the amplitude and timing of the write voltage pulse can more than triple the endurance (from 1,053 to 4,300 cycles) by gently controlling the filament collapse and minimizing damage to the switching layer [36]. Finally, the emergence of flexible devices like Ti/NiO/AZO/PET demonstrates that performance can be maintained even on non-conventional substrates, which is crucial for wearable electronics [3].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Characterization

Measuring ON/OFF Ratio

The ON/OFF ratio is typically extracted from current-voltage (I-V) characterization sweeps. A standard protocol involves:

- SET Process: Sweep the voltage from 0 V to a positive VSET (e.g., ~1-2 V for HfOx devices [37]) with a current compliance (CC) to prevent hard breakdown. This forms the conductive filament and switches the device to the LRS.

- READ Operation: Apply a small, non-destructive read voltage (e.g., 0.1-0.2 V) to measure the LRS current (ILRS).

- RESET Process: Sweep the voltage to a negative VRESET (e.g., ~ -1 V to -2 V) to rupture the filament, switching the device to the HRS.

- READ Operation: Again, apply the read voltage to measure the HRS current (IHRS). The ON/OFF ratio is then calculated as RHRS/RLRS, which is equivalent to ILRS/IHRS at the read voltage. For MLC operation, multiple discrete ON/OFF ratios are defined by controlling the writing current or stop voltage to achieve intermediate resistance states [34] [26].

Endurance Testing

Endurance is evaluated by continuously switching the device between HRS and LRS while monitoring the resistance values.

- A tester (e.g., a semiconductor parameter analyzer) is used to apply repetitive SET and RESET voltage pulses.

- After a predefined number of cycles (e.g., every 100 or 1000 cycles), the testing is paused, and a read operation is performed to check if the HRS and LRS remain within a specified tolerance band.

- The test continues until the device fails to switch or the resistance window closes beyond an acceptable level. The total number of cycles before failure is recorded as the endurance. As shown in ZnO-based devices, using optimized alternating voltage pulses instead of DC sweeps can significantly enhance the cycling lifetime by reducing damage during the RESET process [36].

Retention Characterization

Retention tests assess the non-volatile stability of both the LRS and HRS.

- The device is first programmed into a target state (LRS or HRS).

- The resistance is measured at a specific read voltage immediately after programming and then at regular time intervals.

- To accelerate testing and predict long-term behavior, the device is often baked at an elevated temperature (e.g., 85°C or 125°C). The test continues until the resistance state degrades or for a sufficient duration to extrapolate to a target (e.g., 10-year) retention time [26]. A device like the ZnS-based ReRAM demonstrated a stable retention of over 6,000 seconds at room temperature [34].

Advanced Techniques: Ratio-Based Encoding for MLC

A significant challenge in MLC ReRAM is the inherent variability of resistive states. A promising solution to this problem is ratio-based encoding (RatioBE), which fundamentally changes how information is stored.

The Principle of Ratio-Based Encoding

Instead of relying on the absolute resistance of a single device (Resistance-Based Encoding, or ReBE), RatioBE uses the resistance ratio of a pair of devices configured as a voltage divider. A read voltage (Vread) is applied across the series, and the normalized output voltage (Vstate/Vread) at the mid-point, which is equal to R2/(R1+R2), is used to determine the memory state [35].

This method offers a profound advantage: the statistical distribution of a resistance ratio is much tighter than the distribution of the absolute resistances of the individual devices. Consequently, the probability of a read error is dramatically reduced. Mathematical analysis has shown that for a given system, if the bit error probability (BEP) of ReBE is 10⁻ˣ, the BEP of RatioBE will be between 10⁻²ˣ and 10⁻√²ˣ—an improvement of several orders of magnitude [35]. This allows for either more reliable operation or a reduction in programming time and energy by 5-10 times for the same BEP.

Application in Multi-Level Cells

For an n-level MLC, RatioBE requires determining the optimal mean resistance values for the two devices (R1 and R2) to create n distinct and well-separated ratio states. The variances of these ratio states differ, making the search for optimal reference voltages non-trivial [35]. However, once optimized, this approach enables a 20-40% higher memory capacity for a given bit error probability and programming effort compared to traditional ReBE, pushing the limits of high-density data storage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential ReRAM Research Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for ReRAM Fabrication

| Material / Reagent | Function in ReRAM Device | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Switching Layer Materials | Thin film where resistive switching occurs; forms/ruptures conductive filaments. | ZnS [34], HfOₓ [37], ZnO [36], NiO [3] |

| Active Electrode (TE) | Provides mobile ions (for ECM) or serves as oxygen reservoir (for VCM). | Ag [34], Ti [3] |

| Inert Electrode (BE) | Serves as a chemically stable contact; blocks ion migration. | Pt [34] [37], TiN [36] [37], AZO [3] |

| Fabrication Equipment | Deposits thin, uniform, and high-quality functional layers. | RF Magnetron Sputtering [34] [3], Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) [37] [26] |

| Semiconductor Parameter Analyzer | Performs electrical characterization (I-V sweeps, endurance, retention). | Agilent B1500A [37], Keithley 2400 Source Meter [3] |

The performance landscape of ReRAM is defined by the interplay between ON/OFF ratio, endurance, and retention. As the comparative data shows, no single material system currently dominates all metrics; rather, the choice involves inherent trade-offs. MIS structures like Pd/HfOx/p-Ge offer a large memory window crucial for FPGA and compute-in-memory applications [37], while material engineering in ZnS devices enables promising multi-level storage capabilities [34]. Furthermore, innovative approaches like ratio-based encoding [35] and pulse optimization [36] demonstrate that circuit- and system-level solutions can effectively overcome device-level variability and endurance limitations. Ongoing research into novel materials, refined switching mechanisms, and intelligent architectural designs continues to push the boundaries of these key metrics, steadily paving the way for the commercial adoption of ReRAM in next-generation electronics.

From Theory to Practice: Characterization Methods and Cutting-Edge Applications