Protein Expression Analysis Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Yield, Accuracy, and Application

Protein expression analysis is a cornerstone of modern biological and clinical research, essential for biomarker discovery, drug target validation, and understanding fundamental cellular processes.

Protein Expression Analysis Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Yield, Accuracy, and Application

Abstract

Protein expression analysis is a cornerstone of modern biological and clinical research, essential for biomarker discovery, drug target validation, and understanding fundamental cellular processes. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the current landscape of protein expression analysis methods, from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We explore the principles, advantages, and limitations of key methodological platforms including mass spectrometry-based proteomics, immunoassays, and gel-based techniques. A special focus is given to troubleshooting common challenges such as handling membrane proteins, managing data complexity, and ensuring quantification accuracy. Furthermore, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of statistical methods and workflow performance for differential expression analysis, benchmarking their efficacy in identifying true biological signals. This review serves as a critical resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to select, optimize, and validate protein expression analysis methods for their specific research needs.

The Foundational Landscape of Protein Expression Analysis: Core Concepts and Inherent Challenges

Proteomics, the large-scale study of the complete set of proteins expressed in a cell, tissue, or organism, faces significant analytical challenges that complicate comprehensive protein analysis [1]. Unlike the more static genome, the proteome is highly dynamic, capturing functional events like protein degradation and post-translational modifications [2]. The central hurdles in proteomic analysis stem from the enormous complexity of biological structures, the extremely wide dynamic range of protein concentrations, and the necessity of understanding biological context [1]. This article objectively compares current protein expression analysis methods, evaluating their performance in addressing these fundamental challenges through supporting experimental data and standardized protocols.

Core Challenges in Proteomics

The proteomic landscape is characterized by several intrinsic difficulties that confound complete analysis. In human samples, while approximately 30,000 genes encode proteins, the total number of distinct protein products—including splice variants and post-translational modifications—may approach one million [1]. This diversity is further complicated by protein concentrations that can vary by more than 10 orders of magnitude within a single sample, with some proteins present in over 100,000 copies per cell while others exist in fewer than one copy [1]. Biological context adds another layer of complexity, as protein function depends on subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions, and modification states that mass spectrometry alone cannot fully resolve without complementary spatial techniques [2].

Comparative Analysis of Major Proteomic Technologies

The following analysis compares the principal technologies used in proteomic research, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations in addressing proteomic complexity, dynamic range, and biological context.

Technology Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative performance of major proteomic technologies

| Technology | Principle | Dynamic Range | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2DE/DIGE | Separates proteins by charge (pI) and mass | ~3 orders of magnitude [3] | 150 pg/protein (DIGE) [3] | Low to moderate | Poor for membrane proteins; limited for high MW proteins (>150 kDa) [3] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identifies peptides by mass-to-charge ratio | Varies by platform | Femtomole range [3] | High for modern platforms | Requires extensive sample preparation; data complexity [1] [3] |

| Affinity-Based Platforms (SomaScan/Olink) | Uses binding reagents (aptamers/antibodies) | High (designed for plasma) [2] | High for targeted analysis | Very high (population scale) | Limited to predefined targets; reagent availability [2] |

| Spatial Proteomics | Maps protein location in tissue context | N/A | Single-cell potential | Moderate | Limited multiplexing without specialized platforms [2] |

Experimental Data on Protein Expression Systems

Table 2: Performance metrics of protein expression systems for recombinant production

| Expression System | Typical Yield (grams/Liter) | Typical Purity (%) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 1-10 [4] | 50-70 (without purification) [4] | Rapid growth, high expression levels | Lack of post-translational modifications, protein misfolding [4] |

| Yeast | Up to 20 [4] | ~80 (optimized conditions) [4] | Eukaryotic modifications, high yield | May not replicate human modifications |

| Mammalian Cells | 0.5-5 [4] | >90 [4] | Proper folding, human-like modifications | High cost, longer culture times [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Two-Dimensional Differential Gel Electrophoresis (2D-DIGE)

The 2D-DIGE protocol enables multiplexed analysis of protein samples with high quantitative accuracy [3]. First, protein samples are extracted and labeled with CyDye fluors (Cy2, Cy3, Cy5) on lysine residues. An internal standard, comprising equal aliquots of all test samples, is labeled with Cy2 and included in every gel. Labeled samples are combined based on protein content and subjected to isoelectric focusing (first dimension) across an appropriate pH gradient (e.g., pH 3-10). Focused strips are equilibrated in SDS buffer and placed on SDS-PAGE gels for second-dimension separation by molecular weight. Gels are scanned at wavelengths specific to each CyDye, and images are analyzed using specialized software (e.g., DeCyder) to detect protein abundance changes with statistical confidence, reliably quantifying changes as subtle as 20% in abundant proteins [3].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis

For mass spectrometry analysis, proteins are first enzymatically digested, typically with trypsin, which cleaves specifically at the C-terminal side of lysine and arginine residues [3]. Peptide mixtures are desalted and concentrated using C18 pipette tips or columns, then separated by nanoflow liquid chromatography. Eluting peptides are ionized via electrospray ionization and analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., MALDI-TOF-TOF or Orbitrap instruments). For identification, peptide mass fingerprinting compares experimental masses to theoretical digests in databases, while tandem MS/MS provides sequence information. Quantitative comparison employs either stable isotope labeling (e.g., SILAC, iTRAQ) or label-free methods based on spectral counts or peak intensities [1] [3].

Membrane Protein Enrichment and Analysis

Membrane proteome analysis requires specialized solubilization techniques to address hydrophobicity [1]. An enriched membrane fraction is prepared via differential centrifugation. The fraction is solubilized using 90% formic acid with cyanogen bromide, 0.5% SDS with subsequent dilution before labeling, or 60% methanol with tryptic digestion directly in the organic solvent [1]. For cell surface proteomics, live cells are labeled with membrane-impermeable biotin reagents to tag extracellular domains, followed by affinity capture with streptavidin beads. Captured proteins are digested on-bead, and peptides are analyzed by LC-MS/MS with specialized chromatographic conditions for hydrophobic transmembrane peptides [1].

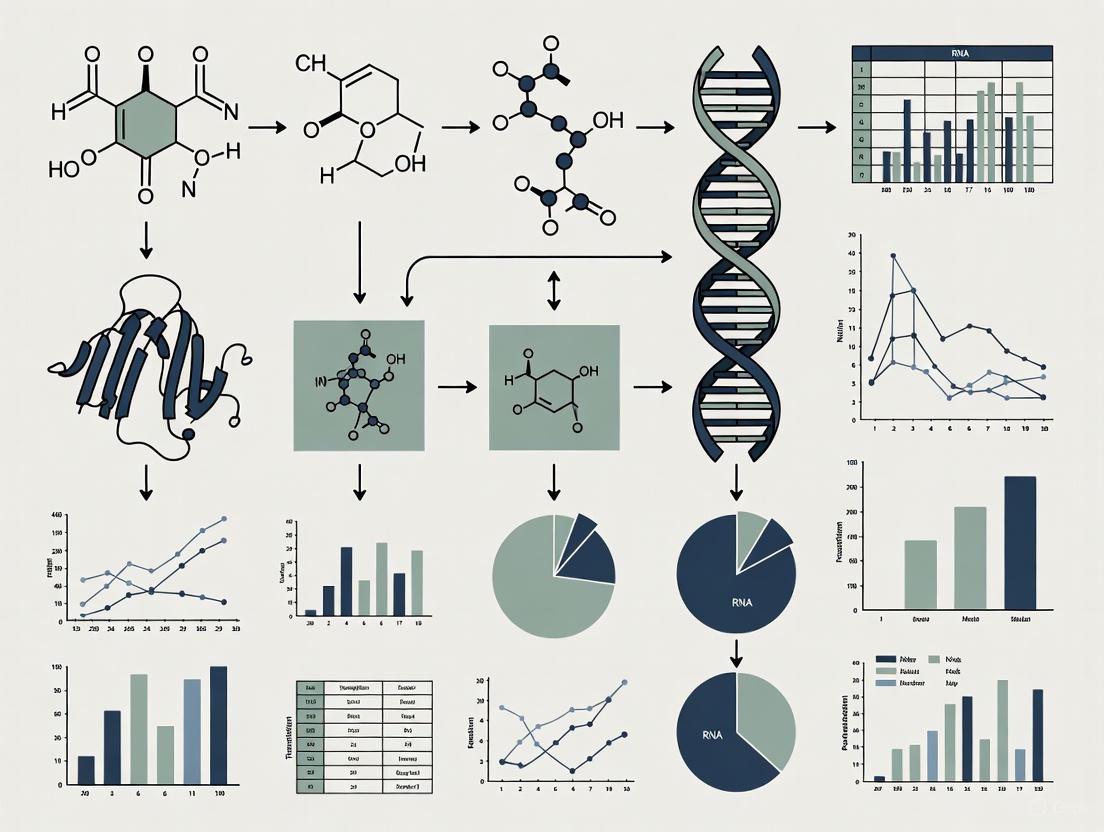

Visualization of Proteomic Analysis Workflows

Proteomic Technologies Decision Pathway

Sample Processing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Key Reagents for Proteomic Analysis

Table 3: Essential research reagents for proteomic studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Media | IPG Strips (pH 3-11), SDS-PAGE Gels, C18 Columns | Separation of complex protein/peptide mixtures by charge, size, or hydrophobicity [3] |

| Detection Reagents | CyDye DIGE Fluors (Cy2, Cy3, Cy5), SYPRO Ruby, Coomassie | Fluorescent or colorimetric detection and quantification of proteins [3] |

| Enzymes | Trypsin, Lys-C, Proteinase K | Specific proteolytic digestion for protein identification and membrane protein analysis [1] [3] |

| Solubilization Agents | Dodecyl Maltoside, Formic Acid, Methanol, SDS | Solubilization of membrane proteins and hydrophobic complexes [1] |

| Depletion Reagents | MARS Column (Multi-Affinity Removal System), Albumin/IgG Removal | Removal of high-abundance proteins to enhance detection of low-abundance species [1] |

| Affinity Reagents | SOMAmer Reagents (SomaScan), Antibodies (Olink), Streptavidin-Biotin | Targeted capture and quantification of specific proteins [2] |

The proteomics field continues to evolve with technologies that progressively address the core challenges of complexity, dynamic range, and biological context. While mass spectrometry remains the workhorse for untargeted discovery proteomics, emerging affinity-based platforms enable population-scale studies, and spatial proteomics preserves crucial biological context. Selection of appropriate methodologies depends heavily on research goals, with comprehensive analysis often requiring orthogonal approaches. Future directions point toward increased integration of multi-omics data, enhanced sensitivity for single-cell proteomics, and more sophisticated computational tools to extract biological meaning from increasingly complex datasets.

This guide provides an objective comparison of modern protein expression analysis methods, critically evaluating their performance in the essential applications of biomarker discovery and drug target validation.

The journey from a novel biological discovery to an approved therapeutic hinges on robust protein analysis. In biomarker discovery, the goal is to identify and validate measurable indicators of a biological state or condition, such as disease presence or response to a treatment. In drug target validation, researchers confirm that a specific protein target is directly involved in a disease pathway and that modulating it will have a therapeutic effect. The success of these endeavors is deeply reliant on the analytical methods used, which must provide not just qualitative identification but precise, reproducible quantification of proteins across complex biological samples. Advanced technologies like liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and multiplexed immunoassays are now pushing beyond the limits of traditional methods, offering the sensitivity, specificity, and throughput required for modern precision medicine [5].

Comparative Analysis of Key Methodologies

The selection of a protein analysis method involves careful consideration of performance characteristics. The table below summarizes key metrics for several prominent techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Profiling Methods

| Method | Multiplexing Capacity | Sensitivity | Sample Throughput | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Low (Single-plex) | High (pg–ng/mL range) [6] | High [6] | Cost-effective; high specificity; easily automated [6] | Narrow dynamic range; highly antibody-dependent [5] |

| Western Blot | Low | Moderate | Low to Moderate [6] | Confirms protein size and post-translational modifications [6] | Semi-quantitative; labor-intensive; low throughput [6] |

| Flow Cytometry | High (Multiparametric) [6] | Very High (single-cell level) [6] | Moderate to High (10K+ cells/sec) [6] | Single-cell resolution; analyzes cell populations and immune responses [6] | Requires cell suspensions; complex data analysis [6] |

| LC-MS/MS | Very High (1000s of proteins) [5] | High (useful for low-abundance species) [5] | Moderate | Unbiased discovery; can analyze modifications; does not require antibodies [5] | High cost; complex instrumentation and data analysis [5] |

| Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) | High (Multiplexed panels) [5] | Very High (up to 100x more sensitive than ELISA) [5] | High | Broad dynamic range; low sample volume requirement [5] | Limited to predefined targets (dependent on assay availability) |

Quantitative Data and Cost Analysis

Beyond performance specs, operational factors like cost and efficiency are critical for project planning. A direct cost comparison highlights the economic advantage of multiplexed methods.

Table 2: Operational and Economic Comparison for a 4-Plex Inflammatory Panel

| Parameter | ELISA (4 individual assays) | MSD (1 multiplex assay) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$61.53 | ~$19.20 [5] |

| Total Cost for 100 Samples | ~$6,153 | ~$1,920 [5] |

| Potential Savings with Multiplexing | - | ~$4,233 (69% reduction) [5] |

| Sample Volume Required | Higher (for multiple wells) | Lower (single well for multiple analytes) [5] |

| Data Output | 4 separate data sets | Integrated data set for 4 analytes |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Detailed and reproducible methodologies are the foundation of reliable science. Below are generalized protocols for two critical applications.

Protocol: Biomarker Validation using MSD Multiplex Assay

This protocol is adapted from methods used to validate inflammatory biomarkers, demonstrating the shift beyond traditional ELISA [5].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute serum or plasma samples in the provided assay diluent. Centrifuge cell culture supernatants to remove any debris.

- Plate Preparation: The MSD U-PLEX plate is pre-coated with capture antibodies. Reconstitute and add the required biotinylated detection antibody mixture to each well.

- Assay Execution:

- Add prepared standards and samples to the plate. Incubate with shaking for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash the plate 3 times with PBS-Tween wash buffer to remove unbound material.

- Add the MSD SULFO-TAG streptavidin reagent, which binds to the biotinylated detection antibodies. Incubate for 1 hour protected from light.

- Wash the plate 3 times again. Add MSD GOLD Read Buffer B to the wells.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Immediately read the plate on an MSD instrument, which applies a voltage to induce electrochemiluminescence. Measure the light signal and quantify analyte concentrations using a standard curve generated from the known standards.

Protocol: Differential Expression Analysis via LC-MS/MS Proteomics

This workflow is central to unbiased biomarker discovery and understanding drug mechanism of action, optimized from recent large-scale benchmarking studies [7].

- Sample Lysis and Protein Digestion: Lyse cells or tissue in an appropriate buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors). Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylate with iodoacetamide. Digest proteins into peptides using trypsin overnight at 37°C.

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): Desalt and separate the resulting peptides using reverse-phase nano-liquid chromatography (e.g., C18 column). A gradient of increasing organic solvent (acetonitrile) elutes peptides based on hydrophobicity.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis:

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): The mass spectrometer first performs a full MS1 scan to measure peptide masses. The most abundant ions from this scan are sequentially isolated and fragmented (MS2) to generate sequence information.

- Tandem Mass Tags (TMT): For multiplexed quantitation, label peptides from different conditions with isobaric TMT reagents. Combine the samples and analyze together. The reporter ions released during MS2 fragmentation provide quantitative data for each sample [8].

- Data Processing and DEA:

- Database Search: Use software (e.g., MaxQuant, FragPipe) to match acquired spectra to a protein sequence database for identification.

- Quantification and Statistical Analysis: Extract quantitative values (e.g., MaxLFQ, spectral counts). Import the expression matrix into statistical software for differential expression analysis, which includes normalization, missing value imputation, and application of statistical tests (e.g., t-test, linear models) to identify significantly altered proteins between experimental groups [7].

Visualizing Workflows and Method Selection

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of key experimental processes and decision-making.

Proteomics Data Analysis Workflow

Assay Selection Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of these protein analysis methods requires specific, high-quality reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Isobaric chemical labels that enable multiplexed quantification of proteins from up to 10 different samples in a single LC-MS/MS run [8]. | Ideal for high-throughput profiling studies; reduces instrument run time and quantitative variability [9]. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Antigen | A highly specific capture antigen used in serodiagnostic assays (e.g., ELISA, Western Blot) for infectious diseases like tularemia [10]. | Provides high specificity for the target pathogen; stable over long periods [10]. |

| Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) U-PLEX Plates | Multi-array plates pre-coated with capture antibodies for custom multiplex panels, allowing simultaneous measurement of multiple analytes from a single small sample volume [5]. | Key for efficient biomarker validation, offering significant cost and sample volume savings over multiple ELISAs [5]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease used to digest residual proteins during the purification of LPS antigens for immunoassays, helping to minimize background and cross-reactivity [10]. | Critical for ensuring the specificity of antibody-based detection. |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Amino Acids (SILAC) | Incorporates stable heavy isotopes into proteins during cell culture, allowing for precise relative quantification of protein abundance between different cell states in mass spectrometry [9]. | Considered the "gold standard" in quantitative proteomics for in-vitro studies due to its early incorporation in sample prep [9]. |

The landscape of protein expression analysis offers a diverse toolkit, with each method presenting a unique set of strengths and trade-offs. Traditional workhorses like Western Blot remain indispensable for confirming specificity and protein size, while ELISA offers robust quantification. However, for the complex challenges of modern biomarker discovery and target validation, advanced methods are taking precedence. Multiplexed immunoassays like MSD provide superior sensitivity and throughput for validating predefined targets, while LC-MS/MS stands out as the most powerful tool for unbiased discovery and system-wide profiling. The optimal choice is not a single technology but an integrated strategy, often combining multiple platforms to leverage their complementary strengths, thereby de-risking the path from discovery to clinically actionable results.

The detailed understanding of protein expression and function is fundamental to advancing biological research and therapeutic development. However, three persistent technical challenges consistently shape experimental design and limit the pace of discovery: the difficult nature of membrane proteins, the detection and quantification of low-abundance species in complex mixtures, and the comprehensive analysis of post-translational modifications (PTMs). These hurdles represent significant bottlenecks in fields ranging from structural biology to drug discovery, where over half of all pharmaceutical targets are membrane proteins [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of current methodologies addressing these challenges, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their experimental strategies.

Membrane Protein Expression and Structural Analysis

The Fundamental Challenges

Membrane proteins, particularly transmembrane proteins, are notoriously difficult to study due to their hydrophobic nature and complex folding requirements. While they constitute nearly 30% of all known proteins, they represent only 2-5% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank [11]. Their hydrophobic transmembrane domains tend to aggregate when removed from their native lipid bilayer, leading to misfolding, loss of function, and low expression yields. Furthermore, their natural abundance is often low, and boosting expression can trigger host toxicity. The requirement for specific post-translational modifications and the protective lipid membrane environment for proper folding adds further complexity to expression and purification workflows [11].

Comparative Performance of Expression Systems

Selecting the appropriate expression system is crucial for successfully producing functional membrane proteins. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the most common platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Membrane Protein Expression Systems

| Expression System | Typical Yields | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotic (E. coli) | Variable; often low for complex MPs | Fast growth, low cost, simple genetics | Lacks complex PTMs; frequent misfolding | Initial trials of robust proteins [11] |

| Mammalian (HEK293, CHO) | 0.5-5 g/L [4] | Native-like PTMs and folding; high functionality | Higher cost, longer culture times, complex workflow | Therapeutic proteins, GPCRs, ion channels [11] |

| Insect Cell (Baculovirus) | Moderate to High | Handles complex eukaryotic proteins | Glycosylation patterns differ from mammals | Large-scale production for structural studies [11] |

| Cell-Free | N/A (in vitro) | Rapid production; suitable for toxic proteins | Limited PTM capabilities; high cost | High-throughput screening, toxic proteins [11] |

Experimental Protocol: High-Yield Mammalian Expression

For producing functionally folded human transmembrane proteins, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), the Expi293F mammalian system is a common choice. A typical optimized protocol involves [11]:

- Vector Design: The gene of interest is cloned into a mammalian expression vector. While codon optimization can boost yields, it must be balanced against the risk of misfolding from overly rapid transcription.

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Expi293F cells are grown in suspension culture to a density of 2.5-3.0 x 10^6 cells/mL. Transfection is performed using a specialized reagent like ExpiFectamine, with the amount of transfected DNA fine-tuned to optimize expression levels.

- Expression and Harvest: Cells are typically harvested 18-24 hours post-transfection, or when viability drops below 80%. The presence of a ligand, agonist, or antagonist can be added to the culture to enhance the stability of some membrane proteins during expression.

- Extraction and Purification: Cells are lysed, and the target protein is solubilized using detergents. Purification is achieved via affinity chromatography (e.g., using a His-tag or Strep-tag), often in the continued presence of detergent or amphiphiles to maintain solubility.

Technical Advancements

Recent advancements are helping to overcome these hurdles. For structural studies, the use of engineered cell lines like Expi293F GnTI-, which produce proteins with simpler, more homogeneous glycosylation patterns, has improved the success of techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography [11]. Cryo-EM itself has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for solving membrane protein structures without the need for crystallization [12]. Furthermore, the development of novel membrane mimetics, such as nanodiscs and styrene-maleic acid copolymers, provides a more native-like environment for purified proteins, enhancing their stability for functional assays [12].

Diagram 1: Membrane protein challenge and solution workflow.

Detection and Quantification of Low-Abundance Species

The Problem of Low Abundance in Complex Mixtures

In microbiome research and clinical diagnostics, accurately profiling microbial strains that reside at low relative abundance is critical but challenging. These low-abundance taxa can include pathogens or key functional species that are missed by standard metagenomic profiling tools due to limitations in sensitivity and resolution [13]. Traditional methods that rely on metagenomic assembly often fail to generate high-quality scaffolds for these rare organisms, leading to an incomplete picture of the microbial community [13].

Benchmarking of Computational Profiling Tools

The development of advanced bioinformatics algorithms has significantly improved the ability to detect and quantify low-abundance species with strain-level resolution. The following table compares the performance of several state-of-the-art tools as demonstrated on benchmarking datasets.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Tools for Profiling Low-Abundance Species

| Tool | Core Methodology | Reported Advantage | Benchmarking Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChronoStrain [13] | Bayesian model using quality scores & temporal data | Superior low-abundance detection and temporal tracking | Outperformed others in abundance estimation (RMSE-log) and presence/absence prediction (AUROC) on semi-synthetic data [13] |

| Meteor2 [14] | Microbial gene catalogues & signature genes | High sensitivity in species detection | Improved detection sensitivity by ≥45% in shallow-sequenced human/mouse gut microbiota simulations vs. MetaPhlAn4/sylph [14] |

| StrainGST [13] | Reference-based alignment and SNP calling | Established method for strain tracking | Outperformed by ChronoStrain in benchmarking, particularly for low-abundance strains [13] |

| mGEMS [13] | Pile-up statistics for strain quantification | Effective for strain abundance estimation | Showed good performance on target strains but was outperformed by ChronoStrain in comprehensive benchmarks [13] |

Experimental Protocol: ChronoStrain for Longitudinal Profiling

ChronoStrain is designed for analyzing longitudinal shotgun metagenomic data. Its workflow is as follows [13]:

- Input Preparation:

- Raw Data: Provide raw FASTQ files from the time-series experiment with associated base quality scores.

- Reference Database: Supply a database of relevant genome assemblies.

- Marker Seeds: Provide a set of marker sequence "seeds" (e.g., core genes, virulence factors).

- Bioinformatics Preprocessing: The tool uses the seeds and genome database to build a custom database of marker sequences for each strain to be profiled. Raw reads are then filtered against this custom database.

- Model Inference: The ChronoStrain Bayesian model is run using the filtered reads, sample timepoint metadata, and the custom marker database. The model explicitly incorporates base-call uncertainty and temporal information.

- Output Analysis: The primary outputs are a probability distribution over the abundance trajectory for each strain and a presence/absence probability for each strain across all timepoints, allowing researchers to assess model uncertainty directly.

Impact and Applications

ChronoStrain's ability to accurately profile low-abundance taxa has been demonstrated in real-world studies. When applied to longitudinal fecal samples from women with recurrent urinary tract infections, it provided improved interpretability for tracking Escherichia coli strain blooms. It also showed enhanced accuracy in detecting Enterococcus faecalis strains in infant gut samples, validated against paired sample isolates [13]. Similarly, Meteor2 has been validated on a fecal microbiota transplantation dataset, demonstrating its capability for extensive and actionable metagenomic analysis [14].

Diagram 2: ChronoStrain workflow for low-abundance species.

Analysis and Engineering of Post-Translational Modifications

The Complexity of PTM Analysis

Post-translational modifications are crucial for the stability, localization, and function of most proteins, especially therapeutics. However, workflows for studying PTMs have traditionally been low-throughput. Common methods like mass spectrometry, Western blotting, and isothermal titration calorimetry are often time-consuming, complex to analyze, and limit studies to tens of variants [15]. This creates a major bottleneck for engineering PTMs into biologics.

High-Throughput Workflow: Cell-Free Expression with AlphaLISA

A breakthrough high-throughput workflow combines cell-free gene expression (CFE) with a bead-based, in-solution assay called AlphaLISA [15]. This platform bypasses the need for live cells, enabling the parallelized expression and testing of hundreds to thousands of PTM enzyme or substrate variants in a matter of hours.

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing RiPP Recognition Elements (RREs) [15]

This protocol demonstrates the workflow for studying interactions between RREs and their peptide substrates, a key step in the biosynthesis of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs).

- Cell-Free Expression:

- Express the RRE protein (often fused to Maltose-Binding Protein, MBP) and an N-terminally sFLAG-tagged peptide substrate in separate PUREfrex cell-free reactions.

- Assay Setup:

- Mix the RRE-expressing reaction with the corresponding peptide-expressing reaction.

- Add anti-FLAG donor beads and anti-MBP acceptor beads to the mixture.

- Signal Detection:

- Incubate the plate to allow bead binding. Only if the RRE binds to the peptide are the donor and acceptor beads brought into close proximity.

- When excited by a laser, the donor bead emits singlet oxygen, which triggers a chemiluminescent emission from the nearby acceptor bead. The signal is quantified and is directly proportional to the strength of the RRE-peptide interaction.

Performance and Applications

This CFE-AlphaLISA workflow has been successfully applied to both RiPPs and glycoproteins. It has been used to characterize peptide-binding landscapes via alanine scanning, map critical residues for binding, and engineer synthetic peptide sequences capable of binding natural RREs [15]. In glycoprotein engineering, the platform enabled the screening of a library of 285 oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) variants, identifying seven high-performing mutants, including one with a 1.7-fold improvement in glycosylation efficiency with a clinically relevant glycan [15]. This demonstrates a significant acceleration over traditional low-throughput methods.

Table 3: Comparison of PTM Analysis Methods

| Method | Throughput | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Typical Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry [16] [15] | Low | Comprehensive, identifies unknown PTMs | Complex data analysis, low throughput | Identification and site mapping of diverse PTMs [16] |

| Western Blot / ELISA [15] | Low | Specific, widely accessible | Semi-quantitative, requires specific antibodies | Presence/relative amount of a specific PTM |

| CFE + AlphaLISA [15] | High (100s-1000s) | Quantitative, rapid, minimal sample volume | Requires bespoke assay design | Quantitative binding or enzymatic activity data |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the advanced methodologies discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Technical Challenges

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Expi293F Cell Line [11] | Mammalian expression host for complex proteins | High-yield expression of human membrane proteins like GPCRs and ion channels with proper PTMs. |

| Membrane Mimetics (e.g., Nanodiscs) [12] | Provides a native-like lipid environment for purified proteins | Stabilizes membrane proteins in solution for structural and functional studies. |

| PUREfrex System [15] | Reconstituted cell-free protein synthesis machinery | High-throughput expression of proteins and peptides for PTM engineering and interaction studies. |

| AlphaLISA Beads (Anti-FLAG, Anti-MBP) [15] | Bead-based proximity assay for detecting molecular interactions | Quantifying protein-protein or enzyme-substrate interactions in a high-throughput, plate-based format. |

| SomaScan Platform [2] | Aptamer-based affinity proteomics platform | Large-scale profiling of thousands of proteins in biological samples for biomarker discovery. |

| Olink Explore Platform [2] | Proximity extension assay for proteomics | High-throughput, high-specificity protein quantification in large cohort studies. |

| ChronoStrain Database [13] | Custom database of marker sequences for microbial strains | Enables strain-level tracking and quantification in metagenomic samples. |

| Meteor2 Gene Catalogues [14] | Ecosystem-specific microbial gene catalogues | Provides a reference for taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of metagenomes. |

For decades, the central dogma of molecular biology has established a fundamental framework for understanding information flow from DNA to RNA to protein. This paradigm has led to the widespread use of mRNA expression levels as proxies for protein abundance in everything from basic research to clinical diagnostics. However, proteogenomic studies—research that integrates genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data—have consistently revealed that this relationship is far more complex and less deterministic than previously assumed. The correlation between mRNA and protein abundances varies dramatically across biological contexts, typically ranging between 0.2 and 0.6 depending on the system studied and measurement techniques used [17] [18]. This conundrum presents significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on accurate protein expression data for their work. Understanding the factors that contribute to this discrepancy is not merely an academic exercise—it has profound implications for how we interpret omics data, validate therapeutic targets, and develop clinical biomarkers.

This comparison guide objectively examines the performance of different methodological approaches in resolving the mRNA-protein correlation conundrum, providing experimental data and protocols to inform research decisions. We evaluate bulk versus single-cell analyses, cross-species conservation approaches, and targeted proteogenomic methods, highlighting how each technique contributes unique insights to this complex biological puzzle.

Methodological Comparison: Mapping the Disconnect

Bulk Omics Analyses: Establishing Baselines

Large-scale proteogenomic studies of human tumors and cell lines have established foundational knowledge about mRNA-protein relationships. When analyzed across multiple samples, the median Spearman correlation between mRNA and protein levels typically falls in the moderate range of 0.4-0.55 [17]. However, this aggregate statistic masks substantial variation at the individual gene level, where correlations can range from negligible to strongly positive.

Table 1: mRNA-Protein Correlations Across Proteogenomic Studies

| Study/System | Reported Correlation (Spearman) | Protein Inclusion Criteria | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [17] | 0.55 | <50% missing values | Among highest correlations in human tumors |

| Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) [17] | 0.54 | <50% missing values | Consistent with other solid tumors |

| Breast Cancer (BrCa 2020) [17] | 0.44 | Proteins <70% missing values | Representative of median correlation |

| GTEx Healthy Tissues [17] | 0.51 | <5 tissues with missing values | Slightly higher than cancer datasets |

| NCI-60 Cancer Cell Lines [17] | 0.36 | Quantified in at least one ten-plex | Lower correlation in cell lines |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa [18] | 0.45-0.62 | Both mRNA and protein detected | Microbial correlations similar to mammals |

A critical insight from these bulk analyses is that measurement reproducibility significantly impacts observed correlations. Proteins with more reproducible abundance measurements tend to show higher mRNA-protein correlations, suggesting that technical limitations account for a substantial portion of the unexplained variation [17]. This has led to the development of aggregate reproducibility scores that explain much of the variation in mRNA-protein correlations across studies. Notably, pathways previously reported to have higher-than-average mRNA-protein correlations, such as certain metabolic pathways, may simply contain members that can be more reproducibly quantified rather than being subject to less post-transcriptional regulation [17].

Single-Cell Multiomics: Revealing Cellular Heterogeneity

While bulk analyses provide population averages, single-cell technologies have revolutionized our understanding by revealing how mRNA-protein relationships vary at the individual cell level. Techniques like CITE-seq and the InTraSeq assay enable simultaneous quantification of mRNA, surface proteins, intracellular proteins, and post-translational modifications within the same single cell [19].

These approaches have demonstrated that standard cell-type markers are often detected more robustly at the protein level than at the transcript level. For example, in analyses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), CD4 protein showed different localization patterns compared to its RNA, while CD8 and CD19 displayed more consistent RNA-protein correlations [19]. This variation across cell types and proteins highlights the limitations of relying solely on transcriptomic data for cell classification.

Transcription factors represent another class of proteins where single-cell analyses have revealed significant discordance. The protein level of TBX21 (T-Bet), a transcription factor driving Th1 T-cell lineage development, was much more clearly associated with memory/effector T cell subpopulations than its mRNA levels [19]. This suggests substantial post-transcriptional regulation affecting how much TBX21 protein is produced—an insight potentially missed when measuring RNA alone.

Table 2: Single-Cell mRNA-Protein Correlation Patterns for Selected Markers

| Cellular Marker | Cell Type | mRNA-Protein Correlation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | PBMCs (T-cells) | Low | Different localization patterns at protein vs RNA level |

| CD8 | PBMCs (T-cells) | High | Consistent detection at both RNA and protein levels |

| CD19 | PBMCs (B-cells) | High | Reliable marker at both transcriptional and translational levels |

| TBX21 (T-Bet) | CD8+ T-cells | Low | Protein more clearly defines memory/effector subsets |

| Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein | CD4+ T-cells | Very Low | PTMs poorly predicted from transcript abundance |

| Phospho-CREB | CD4+ T-cells | Very Low | Phosphorylation state independent of mRNA levels |

Perhaps most strikingly, single-cell analyses have revealed exceptionally poor correlations between mRNA levels and post-translational modifications (PTMs). Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein (Ser235/236) and Phospho-CREB (Ser133) show minimal correlation with their corresponding mRNA levels [19]. Similarly, STAT3 mRNA was sparsely detected across CD4+ T-cell clusters, while its phosphorylated forms (STAT3 Y705 and STAT3 S727) showed distinct, localized expression patterns [19]. These findings underscore that regulatory information contained in PTMs is largely inaccessible through transcriptomic approaches alone.

Cross-Species Conservation: Universal Principles

Comparative analyses across diverse organisms have revealed surprising conservation in protein-to-RNA (ptr) ratios, suggesting underlying universal principles despite the overall moderate correlations. Studies spanning seven bacterial species and one archaeon have demonstrated that while mRNA levels alone poorly predict protein abundance for many genes, each gene's protein-to-RNA ratio remains remarkably consistent across evolutionarily diverse organisms [18].

This conservation has enabled the development of RNA-to-protein (RTP) conversion factors that significantly improve protein abundance predictions from mRNA data, even when applied across species boundaries. Remarkably, conversion factors derived from bacteria also enhanced protein prediction in an archaeon, demonstrating robust cross-domain applicability [18]. This approach has particular value for studying microbial communities where comprehensive proteomic characterization remains challenging.

Essential genes exhibit distinctive mRNA-protein relationships across species. In both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, essential genes show (i) higher mRNA and protein abundances than non-essential genes; (ii) less variance in mRNA and protein abundance; and (iii) higher correlation between mRNA and protein than non-essential genes [18]. This pattern appears consistent despite phylogenetic distance, suggesting fundamental evolutionary constraints on the expression of essential cellular components.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Proteogenomic Integration for Variant Validation

The STaLPIR (Sequential Targeted LC-MS/MS based on Prediction of peptide pI and Retention time) protocol represents a sophisticated proteogenomic approach for obtaining protein-level evidence of genomic variants [20]. This method addresses key limitations in standard shotgun proteomics by combining multiple acquisition methods to maximize variant peptide identification.

Experimental Workflow:

- Genomic Variant Identification: Perform whole-exome and RNA sequencing to identify nonsynonymous variants (e.g., 2,220 variants identified in gastric cancer cell lines) [20]

- Target Selection: Filter variants (e.g., 1,029 variants yielding unique tryptic peptides after in silico digestion) and select those not identified by standard DDA (e.g., 298 variants targeted for STaLPIR) [20]

- Peptide Detectability Assessment: Evaluate detection probability using tools like enhanced signature peptide (ESP) predictor to ensure variant and reference peptides have similar ionization potential [20]

- Sequential LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- DDA (Data-Dependent Acquisition): Standard untargeted profiling

- Inclusion List: Targeted analysis of predefined masses

- TargetMS2: Precursor-ion independent acquisition for maximal sensitivity [20]

- Customized Database Search: Use customized protein databases incorporating variant sequences identified through genomics [20]

- Validation: Confirm protein-level expression with strict FDR controls (e.g., ≤0.01) [20]

This integrated approach demonstrated substantially improved peptide identification, with TargetMS2 providing 2.6- to 3.5-fold improvement in peptide identification compared to DDA or Inclusion methods alone in complex samples [20]. Application to gastric cancer cells confirmed protein-level expression of 147 variants that would have been missed by conventional proteomics [20].

Microbial RNA-to-Protein Conversion Factors

For microbial systems, a conserved cross-domain approach enables protein prediction from transcriptomic data using conserved protein-to-mRNA ratios [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Paired Multi-Omics Profiling: Perform simultaneous transcriptomics and proteomics across multiple growth conditions and strains [18]

- Ortholog Identification: Identify conserved genes across target species [18]

- Ratio Calculation: Compute protein-to-RNA (ptr) ratios for each orthologous gene [18]

- Conservation Assessment: Identify genes with stable ptr ratios across species and conditions [18]

- Conversion Factor Derivation: Calculate RNA-to-protein (RTP) conversion factors for conserved genes [18]

- Application: Apply conversion factors to transcriptomic data from novel systems to predict protein abundance [18]

This approach has demonstrated that conversion factors derived from one species can significantly improve protein prediction in distantly related organisms, even across domain boundaries (bacteria to archaeon) [18]. The method is particularly valuable for inferring protein abundance in unculturable microbes or complex communities where proteomic analysis remains challenging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA-Protein Correlation Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Multiomics | InTraSeq Assay [19] | Simultaneous quantification of mRNA, surface proteins, intracellular proteins, and PTMs in single cells | Enables comprehensive correlation analysis at single-cell resolution |

| CITE-seq [19] | Concurrent measurement of mRNA and surface proteins in single cells | Limited to surface proteins due to antibody accessibility | |

| Proteogenomics | STaLPIR [20] | Sequential targeted LC-MS/MS for variant peptide identification | Combines DDA, Inclusion, and TargetMS2 methods for maximal coverage |

| Custom Variant Databases [20] | Sample-specific protein databases incorporating genomic variants | Essential for identifying variant peptides not in reference databases | |

| Microbial Studies | RTP Conversion Factors [18] | Cross-species protein abundance prediction from mRNA data | Particularly valuable for unculturable microbes and complex communities |

| Data Analysis | Aggregate Reproducibility Scores [17] | Metrics accounting for measurement variability in correlation studies | Helps distinguish technical from biological causes of discordance |

| ESP Predictor [20] | Evaluation of peptide detection probability in MS experiments | Important for assessing variant peptide detectability |

The mRNA-protein correlation conundrum represents both a challenge and an opportunity for researchers and drug development professionals. The methodological comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that no single approach perfectly captures the complex relationship between transcript and protein abundance. Instead, the optimal strategy depends on the specific research context—bulk analyses provide population-level benchmarks, single-cell technologies reveal cellular heterogeneity, cross-species methods identify conserved principles, and targeted proteogenomics validates specific variants.

For therapeutic development, these insights highlight the critical importance of directly measuring protein targets rather than relying solely on transcriptomic proxies. This is particularly crucial for drug targets where post-translational modifications determine activity, such as kinases and signaling proteins. The poor correlation between mRNA levels and phosphorylation states demonstrated in single-cell studies [19] suggests that transcriptomic data alone may be insufficient for guiding decisions about targeted therapies.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on improving the scalability, sensitivity, and integration of multi-omic approaches. As proteogenomic technologies continue to advance, they will increasingly enable researchers to resolve the mRNA-protein correlation conundrum in specific biological contexts, ultimately leading to more accurate biomarkers, better therapeutic targets, and improved patient outcomes.

Methodological Deep Dive: Platforms, Techniques, and Workflows for Protein Analysis

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become an indispensable technology in modern proteomics, enabling the high-throughput identification and quantification of proteins in complex biological samples [21]. The choice of quantification strategy is a critical decision that directly impacts the depth, accuracy, and reproducibility of proteomic data. These methodologies broadly fall into two categories: label-free and label-based approaches. Label-free quantification (LFQ) relies on directly comparing peptide signal intensities or spectral counts across separate LC-MS runs and includes two primary data acquisition modes: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) [22]. In contrast, label-based quantification utilizes stable isotopes to incorporate mass tags into proteins or peptides, allowing for multiplexed analysis of multiple samples within a single MS run [23]. Prominent label-based techniques include Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC), a metabolic labeling method, and chemical labeling approaches such as Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) and Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation (iTRAQ) [23].

Each methodology presents distinct advantages and limitations concerning multiplexing capability, dynamic range, quantification accuracy, and suitability for different sample types. This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of these workflows, supported by experimental data and performance metrics, to assist researchers in selecting the optimal strategy for their specific research context in protein expression analysis.

Label-Free Quantification: DDA and DIA

Principles and Workflows

Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), historically the most common label-free approach, operates through a cyclic process of selection based on signal intensity [22] [24]. The mass spectrometer first performs a full MS1 scan to record all precursor ions. It then automatically selects the top N most intense ions (e.g., the top 20) from the MS1 scan for subsequent isolation and fragmentation, generating MS2 spectra for peptide identification [22] [25]. This intensity-based selection prioritizes the most abundant peptides, which can sometimes lead to incomplete coverage of lower-abundance species.

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) represents a fundamental shift in acquisition strategy [22] [24]. Instead of selecting specific precursors, DIA systematically fragments all ions within consecutive, predefined isolation windows (e.g., 10-25 Da) that cover a broad mass range (e.g., 400-1000 m/z) [22]. This creates complex MS2 spectra containing fragment ions from all co-eluting peptides within each window. Deconvolution of these complex spectra requires specialized software and often a project-specific spectral library generated from DDA runs or data-dependent information contained in public repositories [24] [25].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational differences between the DDA and DIA acquisition modes.

Performance Comparison: DDA vs. DIA

The technical differences between DDA and DIA translate directly into distinct performance characteristics, making each method suitable for different research scenarios.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DDA and DIA in Label-Free Quantification [22] [24] [25]

| Performance Metric | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Identification Level | MS2 | MS2 |

| Quantification Level | MS1 (Precursor Intensity) | MS2 (Fragment Ion Intensity) |

| Quantitative Reproducibility | Lower (due to stochastic ion selection) | Higher (consistent acquisition across runs) |

| Proteome Coverage/Depth | Lower, can be biased against low-abundance ions | Higher, more comprehensive [25] |

| Missing Values | Higher, especially across many samples | Significantly lower |

| Data Completeness | Moderate | High |

| Dynamic Range | Constrained by ion intensity | Broader, better detection of low-abundance proteins [24] |

| Data Complexity | Simpler, compatible with standard database search | High, requires advanced bioinformatics tools [22] [24] |

| Ideal Application Scope | Exploratory research, novel species, small-scale studies, PTM analysis [24] [25] | Large-scale cohort studies, clinical biomarker verification, high-throughput quantification [24] |

A controlled study comparing DIA and TMT workflows with fixed instrument time demonstrated that DIA provides superior quantitative accuracy, while TMT (a label-based method) offered slightly better precision and 15-20% more protein identifications [26]. In the context of label-free internal comparisons, DIA's comprehensive acquisition strategy directly addresses the issue of missing values that commonly plagues DDA in large-sample studies [27] [24].

Label-Based Quantification: SILAC, TMT, and iTRAQ

Principles and Workflows

Label-based quantification uses stable isotopes to create distinct mass signatures for peptides from different experimental conditions, enabling their simultaneous analysis.

SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture) is a metabolic labeling approach [23] [28]. Cells are cultured in media containing "light" (normal) or "heavy" (e.g., 13C6, 15N4) forms of essential amino acids (e.g., Arginine and Lysine). These heavy amino acids are incorporated into newly synthesized proteins during cell growth and division. After several population doublings, proteins are fully labeled, and samples from different conditions are combined early in the workflow—often before cell lysis—minimizing technical variability [23] [28].

TMT (Tandem Mass Tags) and iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation) are chemical labeling techniques applied to peptides after protein digestion [23]. They use isobaric tags, meaning tags have the same total mass. A typical tag consists of a peptide-reactive group, a mass normalizer, and a mass reporter. Peptides from different samples are labeled with different tags and then pooled. In MS1, a peptide from any sample appears as a single peak. However, during MS2 fragmentation, the tag cleaves, releasing low-mass reporter ions whose intensities reflect the relative abundance of that peptide in each sample [27] [23]. The primary difference is that TMT can multiplex up to 16 samples, while iTRAQ typically allows for 4- or 8-plex experiments [27] [23].

The workflow diagram below outlines the key steps involved in metabolic (SILAC) versus chemical (TMT/iTRAQ) labeling strategies.

Performance Comparison of Label-Based Methods

The structural and procedural differences between SILAC, TMT, and iTRAQ define their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SILAC, TMT, and iTRAQ in Label-Based Quantification [23] [28]

| Performance Metric | SILAC | TMT | iTRAQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labeling Type | Metabolic (in vivo) | Chemical (in vitro) | Chemical (in vitro) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Typically 2-plex (3-plex with Arg0, Lys4, Lys8) | Up to 16-plex | Up to 8-plex |

| Quantification Level | MS1 | MS2 (Reporter Ions) | MS2 (Reporter Ions) |

| Quantification Accuracy | High (early sample mixing) [28] | High, but can suffer from ratio compression [23] | High, but can suffer from ratio compression [23] |

| Sample Compatibility | Limited to living, dividing cells | Broad (cells, tissues, biofluids) | Broad (cells, tissues, biofluids) |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy and reproducibility; simple workflow | High multiplexing capacity; suitable for complex study designs | Good multiplexing for mid-size studies |

| Key Limitation | Not applicable to body fluids or tissues | Ratio compression can affect accuracy; cost for large studies | Ratio compression can affect accuracy; lower plex than TMT |

| Ideal Application Scope | Cell culture studies, protein turnover, interaction studies [23] [29] | Large-scale cohort studies, biomarker discovery, phosphoproteomics [23] | Comparative studies of moderate sample size, PTM analysis |

A critical challenge for both TMT and iTRAQ is ratio compression, a phenomenon where the measured quantitative ratios are underestimated due to the co-isolation and co-fragmentation of nearly isobaric precursor ions, leading to contaminated reporter ion signals [23]. SILAC, which quantifies at the MS1 level, is immune to this issue. Furthermore, because SILAC allows for sample pooling immediately after lysis (or even before), it demonstrates higher reproducibility as variability introduced during all subsequent sample processing steps is eliminated [28].

Integrated Comparison and Practical Guidance

Direct Workflow Comparison: Label-Free vs. Label-Based

To facilitate method selection, the table below provides a direct, high-level comparison of all discussed techniques based on critical experimental parameters.

Table 3: Integrated Comparison of Quantitative Proteomics Workflows [22] [27] [23]

| Parameter | DDA | DIA | SILAC | TMT/iTRAQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Throughput | Medium (individual runs) | Medium (individual runs) | Low (requires cell growth) | High (multiplexed runs) |

| Experimental Flexibility | High (no labeling required) | High (no labeling required) | Low (only cell cultures) | Medium (broad applicability) |

| Data Reproducibility | Moderate | High | High [28] | High (multiplexed) |

| Proteome Coverage | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Moderate (run-to-run variance) | High | High [23] | High (but ratio compression) |

| Detection of Low-Abundance Proteins | Lower | Higher [24] | High | High |

| Overall Cost | Lower (no reagents) | Lower (no reagents) | Medium (cost of labeled amino acids) | Higher (cost of labeling reagents) |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Lower | Higher [22] [24] | Lower | Medium |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of quantitative proteomics experiments requires specific reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions for the workflows discussed.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative Proteomics

| Item | Function/Description | Primary Application(s) |

|---|---|---|

| SILAC Media Kits | Defined cell culture media lacking specific amino acids (e.g., Lys, Arg) for supplementation with stable isotope-labeled forms. | SILAC [23] [28] |

| TMT & iTRAQ Reagent Kits | Sets of isobaric chemical tags that covalently label peptide amines. Enable multiplexing of multiple samples in a single run. | TMT, iTRAQ [27] [23] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Peptides (AQUA/PSAQ) | Synthetic peptides with incorporated heavy isotopes used as internal standards for absolute quantification. | Absolute Quantification (MRM, PRM) [30] |

| Trypsin (Sequencing Grade) | High-purity proteolytic enzyme that cleaves proteins at the C-terminus of Lysine and Arginine, generating peptides for MS analysis. | All Bottom-Up Proteomics Workflows [21] |

| C18 StageTips / Spin Columns | Miniaturized solid-phase extraction tips for desalting and cleaning up peptide mixtures prior to LC-MS/MS. | Sample Preparation for all Workflows [28] |

| Spectral Libraries | Curated collections of MS2 spectra for peptide identification, crucial for deconvoluting complex DIA data. | DIA [24] [25] |

Selection Guidelines for Specific Research Scenarios

- Exploratory Research / Novel Protein Identification: For initial characterization of a proteome from a new species or system, DDA is often preferred due to its simpler data interpretation and high-quality MS2 spectra, which are well-suited for database searching [24].

- Large-Scale Cohort Studies / Clinical Biomarker Screening: When analyzing hundreds of samples (e.g., patient plasma/serum) for biomarker discovery, DIA is the leading choice due to its high data completeness, reproducibility, and robustness across many runs [24]. TMT is also a strong contender due to its high multiplexing, which reduces instrument time, though it comes at a higher reagent cost [26].

- Cell Culture-Based Dynamic Studies: For investigations of protein turnover, post-translational modification dynamics, or protein-protein interactions in cell culture, SILAC is the gold standard. Its metabolic incorporation and early pooling minimize variability, providing excellent accuracy for measuring temporal changes [23] [29].

- Balanced Design with Moderate Sample Number: For studies involving 8-16 samples from tissues or biofluids where high-plex multiplexing is advantageous, TMT provides a powerful solution, allowing for direct comparison within a single run, thereby minimizing missing values and run-to-run variation [23] [26].

- Hybrid Strategies for Maximum Depth and Robustness: A powerful and increasingly common strategy is the "DDA + DIA" integrated approach, where a DDA-based spectral library is first built from a subset of samples, which is then used to analyze a larger DIA dataset from the entire cohort. This combines the identification power of DDA with the quantitative robustness of DIA [24].

The landscape of mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics offers a diverse set of powerful workflows, each with a distinct profile of strengths. There is no single "best" method; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific research question, sample type, scale, and available resources. Label-free DIA excels in large-scale studies requiring high reproducibility and data completeness, while DDA remains valuable for exploratory discovery. Among label-based methods, SILAC provides exceptional accuracy for cell culture models, whereas TMT and iTRAQ offer unparalleled multiplexing flexibility for complex experimental designs involving diverse sample types. As the field advances, the development of hybrid strategies and improved data analysis algorithms will further empower researchers to delve deeper into the proteome, accelerating discoveries in basic biology and drug development.

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) has served as a fundamental separation technique in proteomics for decades, enabling researchers to resolve complex protein mixtures based on two independent physicochemical properties: isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight (MW). [31] This technique first separates proteins by their pI through isoelectric focusing (IEF) in the first dimension, followed by orthogonal separation by MW using SDS-PAGE in the second dimension. [31] The resulting 2D map can resolve thousands of protein spots from a single sample, providing a comprehensive overview of a sample's proteome. [32] Within this field, two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) represents a significant methodological advancement that addresses several limitations of conventional 2D-PAGE. [33] As proteomics continues to evolve, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of these complementary techniques remains crucial for researchers designing experiments to quantify protein expression changes, identify post-translational modifications, and discover disease biomarkers.

The critical distinction between these methodologies lies in their experimental design and quantification approaches. While traditional 2D-PAGE separates individual samples on different gels and compares them post-separation, 2D-DIGE employs multiplex fluorescent labeling to separate multiple samples on the same gel, thereby minimizing gel-to-gel variation. [33] [31] This comparison guide provides an objective evaluation of both techniques' performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal approach for their specific protein expression analysis requirements.

Technical Comparison: 2D-PAGE vs. 2D-DIGE

Fundamental Principles and Workflow Differences

Traditional 2D-PAGE follows a straightforward workflow where proteins from a single biological sample are separated based on charge (pI) through isoelectric focusing on immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips, followed by molecular weight separation via SDS-PAGE. [31] After electrophoresis, proteins are visualized using post-electrophoretic staining methods such as Coomassie blue, silver staining, or fluorescent dyes like Sypro Ruby. [34] [31] Image analysis then involves comparing spot patterns across multiple gels, which introduces technical challenges due to gel-to-gel variability that must be corrected through sophisticated software algorithms. [33]

2D-DIGE introduces a pre-electrophoresis labeling step where proteins from different samples are covalently tagged with spectrally distinct, charge-matched cyanine dyes (Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5) before mixing and separating on the same 2D gel. [33] [31] This multiplexing capability is the foundation of its quantitative precision. A critical innovation in 2D-DIGE is the inclusion of an internal standard – typically a pool of all samples in the experiment – which is labeled with one dye channel (usually Cy2) and run on every gel. [33] This internal standard enables robust normalization across multiple gels and significantly improves the statistical confidence in quantifying protein abundance changes. [33] [31]

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of 2D-PAGE and 2D-DIGE

| Parameter | Traditional 2D-PAGE | 2D-DIGE |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | Coomassie blue: 50 ng/spotSilver staining: 1 ng/spotSypro Ruby: 1 ng/spot [35] | 0.2 ng/spot [35] |

| Samples Per Gel | 1 [35] | 2-3 [33] [35] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | 20-30% coefficient of variation [33] | Can detect differences as small as 10% [35] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited by staining method [34] | Wider dynamic range [35] |

| Reproducibility | Lower due to gel-to-gel variation [35] | Higher; nearly identical data across gels [35] |

| Spot Resolution | Lower [35] | Higher [35] |

| Protein Quantification | Between-gel comparison [33] | Within-gel comparison with internal standard [33] |

| Detection of Post-Translational Modifications | Possible but confounded by gel variability [31] | Excellent for detecting charge/shift modifications [31] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per-gel cost but requires more gels [35] | Higher reagent costs but fewer gels needed [33] [35] |

Recent comparative studies provide experimental validation of these performance characteristics. A 2024 methods comparison study examining host cell protein (HCP) characterization found that while 2D-DIGE provides high resolution and reproducibility for samples with similar protein profiles, it was limited in imaging HCP spots due to its narrow dynamic range in certain applications. [36] The same study demonstrated that Sypro Ruby staining in traditional 2D-PAGE was more sensitive than silver staining and showed more consistent protein detection across different isoelectric points, with silver stain displaying significant preference for acidic proteins. [36]

Another analytical comparative study highlighted that 2D-DIGE top-down analysis provided valuable, direct stoichiometric qualitative and quantitative information about proteins and their proteoforms, including unexpected post-translational modifications such as proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation. [37] This study also reported that label-free shotgun proteomics (a gel-free approach) demonstrated three times higher technical variation compared to 2D-DIGE, underscoring the superior quantitative precision of the DIGE methodology. [37]

Experimental Protocols

Standard 2D-PAGE Workflow Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells or tissue in appropriate buffer (e.g., 30 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 4% CHAPS, pH 8.5). [33]

- Protein Cleanup: Use 2D clean-up kits to remove contaminants that interfere with IEF (e.g., salts, lipids, nucleic acids). [33]

- Quantification: Determine protein concentration using compatible assays (e.g., 2D-Quant kit). [33]

First Dimension - Isoelectric Focusing:

- Rehydration: Apply sample (typically 50-100 μg) to IPG strips (e.g., pH 3-10, 4-7, or narrower ranges) in rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 65 mM DTT, 0.24% Bio-Lyte). [33] [38]

- IEF Program: Perform focusing with stepwise voltage increments (e.g., 50 V for 12 h, rapid ramp to 1000 V, then 8000 V until 40,000 Vh reached). [38]

Strip Equilibration:

- Reduction: Incubate strips in equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 2% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 30% glycerol) containing 1% DTT for 15 minutes. [38]

- Alkylation: Replace with same buffer containing 4% iodoacetamide for 15 minutes. [38]

Second Dimension - SDS-PAGE:

- Gel Casting: Prepare homogeneous or gradient polyacrylamide gels (typically 10-12.5%).

- Transfer: Place equilibrated IPG strips onto SDS-PAGE gels and embed with agarose.

- Electrophoresis: Run at constant current or voltage (e.g., 10 mA/gel for 1 h, then 20 mA/gel until dye front reaches bottom) with cooling. [38]

Protein Visualization:

- Staining: Apply preferred staining method:

Image Analysis:

- Scanning: Use appropriate scanners (laser or CCD-based) for fluorescence or densitometry for visible stains.

- Spot Detection: Apply software algorithms for automatic spot detection and manual editing.

- Gel Matching: Match spots across multiple gels using statistical algorithms and landmark spots.

- Quantification: Normalize spot volumes and compare expression changes.

2D-DIGE Workflow Protocol

Sample Preparation and Labeling:

- Protein Extraction and Cleanup: Follow similar protocol as standard 2D-PAGE. [33]

- Minimal Dye Labeling:

- Adjust protein concentration to 1-5 mg/mL in labeling buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 4% CHAPS, pH 8.5). [33]

- Label 50 μg of each sample with 400 pmol of Cy3 or Cy5 dye. [38]

- Prepare internal standard by pooling equal amounts of all samples and label with Cy2 dye. [33]

- Incubate on ice for 30 minutes in the dark. [38]

- Quench reaction with 10 mM lysine (1 μL per 400 pmol dye). [33] [38]

2D Electrophoresis:

- Sample Mixing: Combine labeled samples (e.g., 50 μg each of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled samples plus 50 μg Cy2-labeled internal standard). [33]

- First and Second Dimension: Follow similar IEF and SDS-PAGE procedures as standard 2D-PAGE. [38]

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Multi-channel Scanning: Scan gels using lasers/filters specific for each dye:

- Differential In-gel Analysis (DIA): Normalize Cy3 and Cy5 signals to Cy2 internal standard within the same gel. [33]

- Biological Variation Analysis (BVA): Compare normalized spot abundances across multiple gels for statistical analysis. [33]

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 2D-DIGE Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CyDye DIGE Fluor Minimal Dyes | Fluorescent labeling of protein lysine groups | Cy2, Cy3, Cy5 (GE HealthCare) [33] |

| IPG Strips | First dimension separation by isoelectric point | Immobiline DryStrips, various pH ranges (GE Healthcare, Bio-Rad) [33] |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Protein extraction and solubilization | 30 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 4% CHAPS, pH 8.5 [33] |

| Rehydration Buffer | Hydrating IPG strips with sample | 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 65 mM DTT, 0.24% Bio-Lyte [38] |

| 2D Clean-up Kits | Removing interfering contaminants | GE HealthCare, Bio-Rad, or Pierce kits [33] |

| Image Analysis Software | Spot detection, matching, and quantification | DeCyder (GE HealthCare), Progenesis (Nonlinear), SameSpots (Azure) [33] [32] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows of 2D-PAGE and 2D-DIGE methodologies highlighting the critical difference in experimental design - separate gel analysis versus multiplexed within-gel analysis.

Analytical Strengths and Limitations

Advantages of 2D-DIGE

The most significant advantage of 2D-DIGE is its superior quantitative accuracy and reproducibility achieved through the use of the internal standard and multiplexing approach. [33] [31] The internal standard, composed of a pool of all experimental samples, enables accurate spot matching and normalization across multiple gels, effectively minimizing gel-to-gel variation. [33] This design allows detection of protein expression differences as small as 10% with statistical confidence, a level of sensitivity difficult to achieve with traditional 2D-PAGE. [35]

Additionally, 2D-DIGE offers practical benefits including reduced time and resource requirements. Since multiple samples are separated on the same gel, fewer gels are needed for the same number of samples, saving reagents, laboratory supplies, and processing time. [35] This efficiency does not come at the cost of sensitivity – 2D-DIGE maintains detection sensitivity of 0.2 ng/spot, significantly better than Coomassie blue (50 ng/spot) and silver staining (1 ng/spot) used in conventional 2D-PAGE. [35]

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its quantitative advantages, 2D-DIGE has several limitations that researchers must consider. The technology relies on proprietary cyanine dyes and specialized imaging equipment, creating higher initial costs that may be financially limiting for some academic laboratories. [33] The minimal labeling approach used in 2D-DIGE targets lysine residues, potentially introducing bias against proteins with low lysine content, which may be under-represented regardless of their actual abundance. [33]

Both techniques share inherent limitations of gel-based proteomics, including under-representation of certain protein classes. Membrane proteins, very large or small proteins, and proteins with extreme pI values remain challenging to separate effectively. [33] A 2024 study also highlighted that 2D-DIGE can have a narrow dynamic range in certain applications, such as host cell protein characterization, where traditional 2D-PAGE with Sypro Ruby staining provided more comprehensive coverage. [36]

Applications in Protein Expression Analysis Research

2D-DIGE has demonstrated particular utility in biomarker discovery and comparative proteomics across diverse research fields. In cancer research, a 2021 study successfully employed 2D-DIGE coupled with mass spectrometry to identify serum protein biomarkers for endometrial cancer, discovering 16 proteins with diagnostic potential and validating four proteins (CLU, ITIH4, SERPINC1, and C1RL) that were upregulated in cancer samples. [38] The mathematical model built from these proteins detected cancer samples with excellent sensitivity and specificity, demonstrating the clinical potential of this approach. [38]

In neuroscience, 2D-DIGE has been applied to study protein expression changes in neurological disorders including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis. [31] The ability to detect post-translational modifications makes it particularly valuable for studying phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and other modifications that play crucial roles in neuronal signaling and disease pathogenesis. [31]

Drug development applications include toxicity assessment studies where 2D-DIGE has been used to identify protein expression changes associated with compound toxicity. [33] The technology's high reproducibility and statistical robustness make it well-suited for these applications where detecting subtle protein changes can provide early indicators of adverse effects.

Both 2D-PAGE and 2D-DIGE remain vital tools in the proteomics toolkit, each with distinct strengths and appropriate application domains. Traditional 2D-PAGE offers accessibility, lower per-gel costs, and well-established protocols suitable for qualitative protein profiling and studies where budget constraints are paramount. Conversely, 2D-DIGE provides superior quantitative accuracy, reproducibility, and statistical power for studies requiring precise measurement of protein expression changes.

The choice between these techniques should be guided by specific research objectives, sample availability, and technical requirements. For discovery-phase studies aiming to identify potential biomarkers or characterize global proteome changes, 2D-DIGE's internal standard design and multiplexing capabilities offer clear advantages. However, for applications requiring comprehensive visualization of complex protein mixtures with certain characteristics, such as host cell protein analysis, traditional 2D-PAGE with optimized staining may provide superior performance. [36]

As proteomics continues to evolve, these gel-based techniques maintain their relevance by providing unique capabilities for intact protein analysis and proteoform characterization that complement emerging gel-free approaches. [37] Their continued development and integration with mass spectrometry ensures that both 2D-PAGE and 2D-DIGE will remain essential methods for comprehensive protein expression analysis in basic research and drug development.

The accurate quantification of protein expression is a cornerstone of biological research and drug development. Among the numerous techniques available, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), Western Blot, and Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA) have emerged as foundational methods for targeted protein analysis. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different experimental needs and sample types. ELISA provides a quantitative, solution-based approach ideal for analyzing specific proteins in bodily fluids like serum or plasma. Western Blot offers semi-quantitative analysis with the added advantage of protein separation by molecular weight, allowing for the confirmation of protein identity. RPPA represents a high-throughput, multiplexed platform capable of quantifying hundreds of proteins across thousands of samples simultaneously with minimal sample consumption [39] [40].