PAM Sequences in CRISPR: The Essential Gatekeeper of Genome Targeting and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) and its pivotal role in CRISPR-Cas systems.

PAM Sequences in CRISPR: The Essential Gatekeeper of Genome Targeting and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) and its pivotal role in CRISPR-Cas systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we detail the PAM's fundamental biology as a targeting gatekeeper, methodologies for its characterization and application, strategies to overcome its limitations through nuclease engineering, and advanced techniques for validating targeting specificity. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest advances in PAM profiling and engineered nucleases, this guide serves as a critical resource for optimizing CRISPR experimental design and accelerating the development of precise genetic therapies.

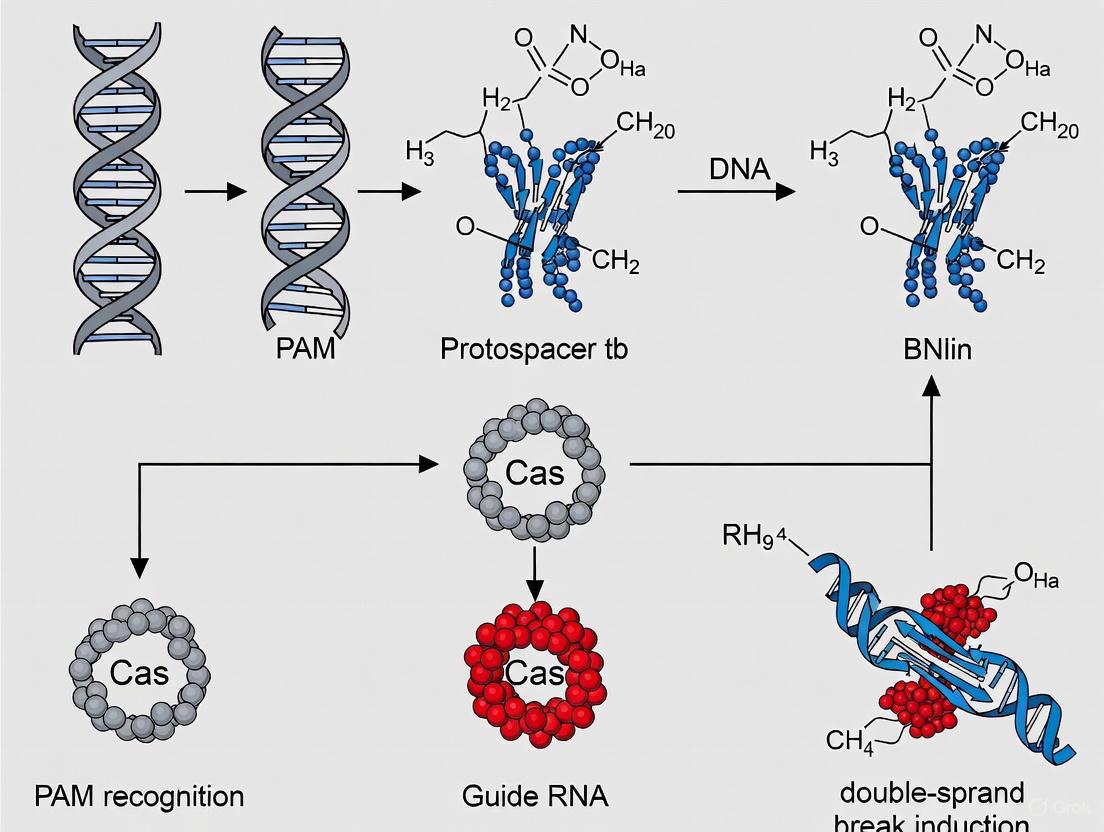

The PAM Sequence: Unlocking the Fundamental Mechanism of CRISPR Targeting

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) represents a critical sequence-specific requirement for CRISPR-Cas systems, serving as the fundamental molecular gatekeeper that licenses Cas nuclease activity. This short, defined DNA sequence, typically 2-6 base pairs in length, flanks the DNA region targeted for cleavage and enables CRISPR systems to discriminate between self and non-self genetic material [1] [2]. From an evolutionary perspective, PAM recognition prevents autoimmunity by ensuring that Cas nucleases do not target the host's own CRISPR arrays, which contain spacer sequences identical to viral protospacers but lack the adjacent PAM sequence [1] [3]. The PAM is not merely a passive marker; it plays an active role in the mechanism of Cas nuclease function. When a Cas nuclease encounters DNA, it first scans for the appropriate PAM sequence [3]. Recognition of a compatible PAM induces conformational changes in the Cas protein that destabilize the adjacent DNA, facilitating DNA unwinding and subsequent interrogation by the guide RNA [2] [3]. This PAM-dependent licensing mechanism ensures that cleavage occurs only when both sequence complementarity (provided by RNA-DNA base pairing) and context recognition (provided by PAM binding) are satisfied, creating a two-factor authentication system for target recognition that balances adaptability with specificity in prokaryotic adaptive immunity.

PAM Diversity Across CRISPR-Cas Systems

The sequence requirements and structural positioning of PAM elements exhibit remarkable diversity across different CRISPR-Cas systems, reflecting the evolutionary adaptation of various Cas nucleases to different microbial environments and viral challenges. This diversity has profound implications for CRISPR-based applications, as the PAM sequence essentially defines the targetable genomic space for any given Cas enzyme.

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Commonly Used CRISPR-Cas Nucleases

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| Nme1Cas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

This table synthesizes data from multiple sources demonstrating the variety of PAM requirements [4] [1]. The structural basis for this diversity lies in the evolution of specialized PAM-interacting domains within different Cas proteins [3]. For example, Cas9 proteins typically recognize PAM sequences on the 3' end of the protospacer, while Cas12a (Cpf1) systems recognize PAM sequences on the 5' end [5]. This fundamental difference in recognition orientation stems from variations in the architectural arrangement of PAM-binding domains across Cas protein families. The PAM recognition mechanism is not merely a binary switch but exists along a spectrum of stringency, with some nucleases exhibiting strong preference for specific sequences while others tolerate degeneracy at certain positions [5]. This functional diversity provides researchers with an expanded toolkit for genome engineering, allowing selection of appropriate nucleases based on the specific sequence context of their target of interest.

Methodologies for PAM Determination

The comprehensive characterization of PAM preferences requires specialized experimental approaches that can efficiently survey the sequence space adjacent to potential target sites. Several high-throughput methods have been developed to elucidate functional PAM sequences, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

PAM-SCANR: An In Vivo Positive Selection System

PAM-SCANR (PAM screen achieved by NOT-gate repression) represents an innovative in vivo screening approach that utilizes a positive, tunable genetic circuit to identify functional PAMs [5]. This method employs a NOT gate logic wherein functional PAM sequences lead to repression of LacI, which in turn derepresses GFP expression. The system is constructed by placing a library of randomized PAM sequences upstream of the -35 element in the lacI promoter, with the CRISPR-Cas system configured to target this promoter region. When a functional PAM is present, the catalytically dead Cas (dCas) complex binds and represses lacI transcription, resulting in GFP expression that can be quantified using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [5]. A key advantage of PAM-SCANR is its tunability through IPTG titration, which allows researchers to adjust system stringency and detect weak functional PAMs that might be missed by other methods. The screen can be performed comprehensively through next-generation sequencing of pre-sorted and post-sorted PAM libraries, or through individual screening of sorted fluorescent clones [5].

PAM-SCANR Workflow: This diagram illustrates the logical flow of the PAM-SCANR method, from library construction through to sequencing of functional PAMs.

PAM-readID: A Mammalian Cell-Based Determination Method

Recent advancements in PAM determination include the development of PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides Integration in DNA double-stranded breaks), a method specifically optimized for mammalian cellular environments [4]. This approach addresses a critical limitation of previous methods, as PAM profiles often show intrinsic differences between in vitro, bacterial, and mammalian cell contexts due to variations in cellular environment, DNA topology, and modification states. The PAM-readID protocol involves: (1) constructing a plasmid bearing a target sequence flanked by randomized PAMs; (2) co-transfecting mammalian cells with this library, Cas nuclease/sgRNA expression plasmids, and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN); (3) extracting genomic DNA after 72 hours to allow for Cas cleavage and NHEJ repair-mediated dsODN integration; (4) amplifying the recognized PAM sequences using a primer specific to the integrated dsODN tag and a second primer specific to the target plasmid; and (5) performing high-throughput sequencing and analysis to generate the PAM recognition profile [4]. A significant advantage of PAM-readID is its sensitivity—accurate PAM preferences for SpCas9 can be identified with extremely low sequence depth (as few as 500 reads). The method has successfully characterized PAM profiles for SaCas9, SaHyCas9, Nme1Cas9, SpCas9, SpG, SpRY, and AsCas12a in mammalian cells, revealing non-canonical PAMs such as 5'-NNAAGT-3' and 5'-NNAGGT-3' for SaCas9 and 5'-NGT-3' and 5'-NTG-3' for SpCas9 [4].

Table 2: Comparison of PAM Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Cellular Context | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAM-SCANR [5] | NOT-gate repression & positive selection | Bacterial cells | Tunable stringency, broad applicability across CRISPR types | Requires genetic circuit construction |

| PAM-readID [4] | dsODN integration & NHEJ tagging | Mammalian cells | Mammalian context, works with low sequencing depth, no FACS needed | Complex workflow requiring multiple transfection steps |

| Plasmid Depletion [3] | Negative selection based on plasmid survival | Bacterial cells | Simple concept, does not require engineered Cas variants | Requires high library coverage, identifies depleted sequences |

| In Vitro Cleavage [3] | Sequencing of enriched cleavage products | Cell-free system | Controlled reaction conditions, input of large libraries | Requires purified protein complexes, may not reflect in vivo activity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PAM Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in PAM Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| dsODN (double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides) | Tags cleaved DNA ends for amplification and sequencing | PAM-readID method for capturing functional PAM sequences [4] |

| dCas9/dCas12 (catalytically dead variants) | DNA binding without cleavage for repression-based screens | PAM-SCANR and other reporter-based PAM determination systems [5] |

| PAM Library Plasmids | Contains randomized nucleotide regions for PAM screening | Provides diverse sequence space to identify functional PAM motifs [4] [5] |

| Fluorescent Reporters (GFP, etc.) | Enables positive selection of functional PAM sequences | FACS-based isolation of cells with active CRISPR targeting [5] |

| CRISPR Design Tools (Benchling, CRISPOR) | Bioinformatics assistance for gRNA design considering PAM constraints | Identifies targetable sites based on known PAM requirements [6] |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

The precise understanding of PAM requirements has direct implications for therapeutic genome editing applications, where target site selection is often constrained by the necessity of a compatible PAM sequence adjacent to the pathogenic mutation. The clinical translation of CRISPR technology highlights this critical relationship between PAM recognition and therapeutic efficacy. For example, Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), recently approved for severe sickle cell disease, utilizes the SpCas9 system with its characteristic NGG PAM requirement [7]. Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics' NTLA-2002, currently in Phase 3 trials for hereditary angioedema, employs a CRISPR-Cas therapy that inactivates the KLKB1 gene, with target site selection fundamentally constrained by PAM availability [7]. The importance of PAM specificity is further highlighted by recent advances in patient-specific therapies, such as the successful treatment of severe carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency using a customized CRISPR base editing therapy delivered via lipid nanoparticles [7]. In this case, the development of a personalized therapeutic required careful consideration of PAM positioning relative to the pathogenic mutation. Emerging approaches to overcome PAM limitations include the development of engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities, such as SpG and SpRY, which recognize non-canonical PAM sequences and thereby expand the targetable genomic space [4] [1]. These advances demonstrate how fundamental research into PAM biology directly enables new therapeutic paradigms.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif stands as an essential molecular gatekeeper in CRISPR-Cas systems, governing the fundamental processes of DNA recognition and cleavage through sophisticated mechanisms that balance specificity and adaptability. The comprehensive characterization of PAM requirements across diverse CRISPR systems, enabled by advanced determination methods like PAM-SCANR and PAM-readID, has dramatically expanded our understanding of Cas nuclease function and expanded the toolbox available for precision genome engineering. As CRISPR technology continues to transition from basic research to clinical applications, the strategic selection and engineering of Cas proteins with specific PAM preferences will remain crucial for targeting therapeutically relevant genomic loci. Ongoing efforts to characterize novel Cas nucleases, engineer expanded PAM specificities, and develop more sophisticated delivery systems promise to further overcome the limitations imposed by PAM requirements, ultimately enabling broader application of CRISPR-based therapies for genetic diseases. The continued elucidation of PAM diversity and function represents a critical frontier at the intersection of basic microbial immunity and applied therapeutic genome editing.

CRISPR-Cas systems provide adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea, defending against invading viruses and mobile genetic elements. The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) serves as the fundamental molecular signature that enables these systems to distinguish between invasive DNA ("non-self") and the host's own genetic material ("self"). This short, conserved DNA sequence adjacent to the target protospacer is indispensable for initiating the immune response while preventing autoimmune destruction of the host's CRISPR arrays. The PAM requirement solves a critical self/non-self discrimination problem: although spacer sequences within the host CRISPR locus are derived from foreign DNA, the host must ensure these stored memories do not trigger immune activation against its own genome. This review examines the molecular mechanisms of PAM-dependent discrimination, quantitative aspects of PAM diversity, experimental methodologies for PAM identification, and the broader implications for CRISPR-based technologies.

Molecular Mechanisms of PAM Recognition

PAM-Dependent Target Activation

CRISPR-Cas systems employ a sophisticated surveillance mechanism where Cas effector proteins continuously scan foreign DNA for PAM sequences. When Cas proteins identify a canonical PAM, they initiate local DNA melting, enabling the guide RNA to probe adjacent sequences for complementarity. This two-step verification process—first PAM recognition, then target interrogation—ensures that only bona fide foreign DNA triggers immune activation [1] [3].

The PAM's strategic positioning immediately adjacent to the target sequence provides the spatial cue that directs Cas nucleases exclusively to foreign DNA. In natural Type II systems, the Cas9 protein recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence (where N is any nucleotide) through specific interactions between the PAM-interacting domain of Cas9 and the minor groove of the DNA duplex. This binding induces conformational changes that facilitate DNA unwinding and R-loop formation, enabling the crRNA to hybridize with the target DNA strand [3].

Self-Avoidance Mechanisms

The host organism's CRISPR arrays inherently lack PAM sequences adjacent to stored spacers, creating a fundamental safeguard against self-targeting. During spacer acquisition, the Cas1-Cas2 integration complex selectively captures protospacer fragments from foreign DNA while excluding the adjacent PAM sequence. Consequently, when the spacer is integrated into the host CRISPR locus and transcribed into crRNA, the resulting guide RNA complexes cannot direct Cas proteins to the host's own DNA because the necessary PAM recognition signal is absent from the chromosomal location [1] [3].

This elegant solution ensures immunological memory while preventing autoimmune destruction. The molecular basis of this discrimination has been elucidated through structural studies of Cas1-Cas2 complexes, which show specific recognition of three PAM nucleotides (5'-CTT-3' in the target strand) positioned in base-specific pockets within the C-terminal domains of Cas1 proteins during spacer acquisition [3].

Diversity of PAM Recognition Across CRISPR Systems

Natural PAM Diversity

CRISPR-Cas systems exhibit remarkable diversity in PAM requirements across different types and subtypes, reflecting evolutionary adaptation to various viral defense scenarios. The table below summarizes characterized PAM sequences for selected Cas effectors.

Table 1: PAM Specificity of Characterized CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Cas Protein | Source Organism | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | System Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | Type II-A |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT | Type II-A |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | Type II-C |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC | Type II-C |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | Type V-A |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV | Type V-A |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | Type V-B |

| Cas12f1 | Engineered | T-rich | Type V-F |

| Cas12i3 | Engineered | TN and/or TNN | Type V-I |

| Cas14 | Uncultivated archaea | TTTA (dsDNA) | Type V-U |

This diversity reflects evolutionary arms races between bacteria and viruses, where PAM recognition strategies have diversified to counter viral anti-CRISPR measures that alter PAM sequences or their accessibility. The varying stringency of PAM requirements represents different evolutionary trade-offs between immune efficiency and evasion of viral countermeasures [3].

Engineered PAM Variants

Protein engineering has generated Cas variants with altered PAM specificities to expand targeting ranges for genome editing applications. Notable examples include:

SpRY: An engineered near-PAMless Cas9 variant containing ten substitutions in the PAM-interacting domain (L1111R, D1135L, S1136W, G1218K, E1219Q, A1322R, R1333P, R1335Q, and T1337R) that reduces specificity from canonical 5'-NGG-3' to more flexible 5'-NRN-3' (where R is A or G) with weaker 5'-NYN-3' (where Y is C or T) targeting [9].

Sc++: An engineered Cas9 variant employing a positive-charged loop-like structure that relaxes the base requirement at the second PAM position, enabling 5'-NNG-3' preference rather than canonical 5'-NGG-3' [9].

SpRYc: A chimeric enzyme combining the PAM-interacting domain of SpRY with the N-terminus of Sc++, demonstrating highly flexible PAM preference capable of editing diverse PAMs including therapeutic targets with 5'-NCN-3' or 5'-NTN-3' PAMs [9].

OpenCRISPR-1: An artificial-intelligence-generated gene editor designed using large language models trained on biological diversity, exhibiting comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence [10].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Editing Efficiencies of PAM-Flexible Editors

| Editor | PAM Preference | Editing Efficiency Range | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | NGG | 40-60% (varies by locus) | Canonical reference editor |

| SpRY | NRN > NYN | 15-45% at NYN sites | Near-PAMless capability |

| SpRYc | NNN (highly flexible) | 10-50% across diverse PAMs | Chimeric design combining SpRY PID with Sc++ N-terminus |

| SpRYc-ABE8e | NNN (base editing) | Up to 21.9% A-to-G conversion at NTT PAMs | Adenine base editor fusion |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | Variable (AI-designed) | Comparable or improved vs SpCas9 | 400 mutations from natural sequences |

Experimental Methods for PAM Identification

PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-Gate Repression)

The PAM-SCANR method provides an in vivo approach for comprehensive PAM identification using a bacterial positive selection system [9] [3].

Protocol:

- Clone a randomized PAM library (typically 5'-NNNNNN-3') adjacent to a fixed protospacer sequence in a reporter plasmid.

- Co-transform the PAM library with two additional plasmids: one expressing a single guide RNA targeting the fixed protospacer, and another expressing a nuclease-deficient dCas9 variant.

- Culture transformed bacteria under conditions where GFP expression is conditioned on successful PAM binding and dCas9 recruitment.

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate GFP-positive cells where functional PAM recognition occurred.

- Isolate and sequence plasmids from sorted cells to identify enriched PAM sequences.

- Analyze sequencing data to determine PAM consensus motifs and relative binding strengths.

This method was utilized to characterize SpRYc, revealing its ability to bind sequences with adenine bases at position 2 without bias against any specific base, unlike SpRY which preferentially binds PAM sequences with A or G at position 2 [9].

HT-PAMDA (High-Throughput PAM Determination Assay)

HT-PAMDA measures cleavage kinetics rather than endpoint binding, providing quantitative data on Cas enzyme activity across diverse PAM sequences [9].

Protocol:

- Prepare a DNA library containing a randomized PAM region adjacent to a target sequence recognized by the guide RNA.

- Incubate the library with purified Cas enzyme-guide RNA complexes under defined reaction conditions.

- Withdraw aliquots at multiple time points to monitor cleavage progression.

- Isemble and sequence cleaved products to determine cleavage rates for each PAM variant.

- Calculate cleavage kinetics and generate sequence logos representing PAM preference.

Application of HT-PAMDA to SpRYc demonstrated slower cleavage rates than SpRY but access to a comparably broad set of PAMs, suggesting its optimal utility in "dead" or nickase variants rather than as a nuclease [9].

Computational PAM Prediction

Bioinformatic approaches identify PAM sequences through alignment of protospacers from viral genomes to identify consensus motifs [3].

Workflow:

- Extract spacer sequences from bacterial CRISPR arrays using tools like CRISPRFinder.

- Identify matching protospacers in viral or plasmid sequences using BLAST or specialized tools like CRISPRTarget.

- Align flanking regions of identified protospacers to detect conserved motifs.

- Generate sequence logos and probability matrices representing PAM preferences.

While computational approaches provide rapid identification, they cannot distinguish between spacer acquisition motifs (SAMs) and target interference motifs (TIMs), and require experimental validation [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PAM Characterization Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PAM-SCANR Plasmid System | In vivo PAM profiling | Identification of functional PAM motifs through bacterial selection [3] |

| HT-PAMDA Library | In vitro cleavage profiling | Quantitative measurement of Cas cleavage kinetics across PAM variants [9] |

| dCas9 Variants | PAM binding without cleavage | PAM recognition studies without inducing DNA damage [3] |

| Randomized PAM Libraries | Comprehensive PAM sampling | Evaluation of PAM preference without sequence bias [9] [3] |

| CRISPRTarget Software | Bioinformatics PAM prediction | In silico identification of potential PAM sequences from genomic data [3] |

| GUIDE-Seq | Genome-wide off-target detection | Comprehensive identification of off-target editing events [9] |

| Digenome-Seq | In vitro off-target detection | Genome-wide mapping of Cas cleavage sites [8] |

| BLESS | In situ breaks labeling | Direct detection of double-strand breaks in fixed cells [8] |

Visualization of PAM Discrimination Mechanism

Diagram 1: PAM-Mediated Self vs Non-Self Discrimination Mechanism. The presence of a PAM sequence in foreign DNA enables Cas protein binding and immune activation, while its absence in host CRISPR arrays prevents autoimmune targeting.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflows for PAM Characterization. In vivo (PAM-SCANR) and in vitro (HT-PAMDA) methods for comprehensive PAM identification and characterization.

The PAM sequence represents a cornerstone of CRISPR-based immunity, enabling precise self versus non-self discrimination through molecular recognition mechanisms that prevent autoimmune targeting while facilitating efficient defense against genetic parasites. Understanding PAM recognition has profound implications for both basic bacterial immunology and applied genome editing technologies. Recent advances in PAM-flexible editors like SpRYc and AI-designed systems like OpenCRISPR-1 demonstrate how fundamental knowledge of natural PAM recognition mechanisms can be leveraged to expand the targeting scope of CRISPR tools. However, these engineered systems must be carefully evaluated for off-target effects, as reduced PAM stringency may compromise specificity. Future research will continue to elucidate the structural basis of PAM recognition and develop increasingly sophisticated editors that balance targeting flexibility with precision for therapeutic applications.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) presents a fundamental component of CRISPR-Cas systems, serving as the initial DNA recognition signal and a critical determinant of target specificity. Despite its central role in genome editing, inconsistent reporting of PAM sequences and their orientation has created confusion within the research community, impeding direct comparison between CRISPR systems and therapeutics development. This technical guide proposes the universal adoption of a guide-centric framework for standardizing PAM communication. We delineate the biochemical rationale for this orientation, provide comprehensive quantitative data on PAM sequences for major CRISPR systems, and detail experimental methodologies for PAM characterization in mammalian cells. Within the broader thesis of CRISPR targeting research, standardized PAM communication establishes the foundational lexicon necessary for advancing basic research, therapeutic development, and clinical applications.

CRISPR-Cas systems have revolutionized genetic engineering by providing programmable nucleic acid recognition capabilities. These systems universally rely on the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)—a short, specific DNA sequence flanking the target site—to initiate target recognition and cleavage [11]. The PAM serves two essential biological functions: it licenses the Cas nuclease for target cleavage and enables self/non-self discrimination by preventing the CRISPR system from targeting the bacterial genome itself, as the PAM sequence is absent from the CRISPR array in the host genome [1] [11].

The PAM requirement represents both a practical constraint and a safety feature in CRISPR applications. From a practical perspective, the PAM restricts the genomic targeting space available for editing, as Cas nucleases can only bind to and cleave DNA sequences flanked by their specific PAM [12]. Therapeutically, this limitation has driven the discovery of novel Cas nucleases with diverse PAM requirements and the engineering of variants with altered PAM specificities to broaden targetable sequences for treating genetic diseases [12] [13].

The Orientation Problem: Inconsistencies in PAM Reporting

Historically, PAM sequences have been reported using different reference strands, creating significant confusion in the literature. Two primary orientations have emerged:

- Target-centric orientation: The PAM is located on the same strand that base pairs with the guide RNA.

- Guide-centric orientation: The PAM is located on the strand that matches the sequence of the guide RNA [11].

These differing conventions have been inconsistently applied across CRISPR system types, with Type I systems typically using the target-centric orientation and Type II and V systems often employing the guide-centric orientation [11]. This lack of standardization complicates the comparison of PAM requirements between different Cas proteins and creates unnecessary barriers to the broad adoption of novel CRISPR systems.

The Guide-Centric Framework: A Proposed Standard

We advocate for the universal adoption of the guide-centric orientation as the standard for PAM communication. This framework offers several significant advantages for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Rationale for Guide-Centric Standardization

The guide-centric orientation aligns directly with guide RNA design, the primary step in any CRISPR experiment. When designing guide RNAs, researchers identify the target sequence based on complementarity to the guide RNA, making the guide-centric PAM the most intuitive reference point [11]. This orientation simplifies experimental design by directly indicating the sequence context in which the guide RNA will function.

Furthermore, the guide-centric approach provides consistency across diverse CRISPR systems. For example, Type II systems (e.g., Cas9) typically have PAMs located 3' of the protospacer on the non-target strand, while Type V systems (e.g., Cas12a) generally have PAMs located 5' of the protospacer [14]. Using a consistent guide-centric framework allows researchers to communicate about these different systems without confusion regarding PAM location and sequence.

Visualizing the Guide-Centric Framework

The following diagram illustrates the guide-centric framework for PAM orientation across major CRISPR system types:

Diagram Title: Guide-Centric PAM Orientation Across CRISPR Systems

PAM Sequences of Major CRISPR Systems in Guide-Centric Orientation

Table 1: PAM Sequences of Commonly Used CRISPR Nucleases in Guide-Centric Orientation

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Source | PAM Sequence (5'→3') | PAM Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | 3' downstream | Canonical Cas9; most widely used [1] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN | 3' downstream | Compact size advantageous for viral delivery [14] [4] |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | 3' downstream | High specificity with lower off-target effects [12] |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC | 3' downstream | Compact ortholog with extended PAM [14] |

| SpRY | Engineered SpCas9 | NRN > NYN | 3' downstream | Near-PAMless variant [14] [4] |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | 5' upstream | Creates staggered cuts; T-rich PAM [1] |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV | 5' upstream | Creates staggered cuts [4] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | 5' upstream | Thermostable variant [1] |

| Cas12f | Uncultivated archaea | T-rich (e.g., TTTA) | 5' upstream | Ultra-small size [1] |

Advanced Methodologies for PAM Characterization in Mammalian Cells

Accurately determining PAM preferences is crucial for developing CRISPR tools. Recent methodological advances enable comprehensive PAM characterization directly in mammalian cells, providing more physiologically relevant data compared to in vitro or bacterial systems.

GenomePAM: Leveraging Genomic Repeats for PAM Identification

The GenomePAM method, published in 2025, represents a significant advancement by utilizing naturally occurring repetitive sequences in the mammalian genome as built-in target libraries [14].

Experimental Protocol for GenomePAM

Identification of Suitable Genomic Repeats: Identify highly repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu elements) with nearly random flanking sequences. The sequence 5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′ (Rep-1) occurs approximately 16,942 times in human diploid cells with diverse flanking sequences, making it ideal for PAM characterization [14].

Vector Construction: Clone the Rep-1 protospacer sequence (or its reverse complement for 5' PAM nucleases like Cas12a) into a guide RNA expression cassette.

Cell Transfection: Co-transfect the gRNA plasmid with a candidate Cas nuclease expression plasmid into mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T).

Cleavage Site Capture: Adapt the GUIDE-seq method to capture cleaved genomic sites using double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN) integration and anchor multiplex PCR sequencing (AMP-seq) [14].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Identify cleavage sites across the genome

- Extract flanking sequences as candidate PAMs

- Generate sequence logos and PAM conservation tables

- Implement iterative "seed-extension" method to identify statistically significant enriched motifs [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for GenomePAM

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Specification | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Rep-1 Protospacer | 5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′ | High-frequency genomic target (~16,942 copies/diploid cell) |

| HEK293T Cells | Human embryonic kidney cell line | Mammalian cellular context for PAM determination |

| dsODN | Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides | Tags double-strand breaks for GUIDE-seq detection |

| AMP-seq | Anchor Multiplex PCR sequencing | Enriches and sequences dsODN-integrated fragments |

| SeqLogo Plotting | Bioinformatics visualization | Graphical representation of PAM sequence preferences |

PAM-readID: A Simplified Method for PAM Determination

PAM-readID offers a more accessible approach for determining PAM recognition profiles in mammalian cells without requiring fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [4].

Experimental Protocol for PAM-readID

Library Construction: Generate a plasmid library containing target sequences flanked by randomized PAM regions.

Cell Transfection: Co-transfect the PAM library plasmid with Cas nuclease and sgRNA expression plasmids, along with dsODN, into mammalian cells.

Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells after 72 hours to allow for cleavage and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated dsODN integration.

PCR Amplification: Amplify integrated fragments using a primer specific to the dsODN tag and a primer specific to the target plasmid.

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence amplicons via high-throughput sequencing (HTS) or Sanger sequencing

- Analyze indel profiles to verify PAM integrity

- Generate PAM recognition profiles from sequenced fragments [4].

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows of these advanced PAM determination methods:

Diagram Title: Comparative Workflows for Mammalian Cell PAM Determination

PAM Engineering and Expansion Strategies

Overcoming the natural limitations of PAM recognition represents a major focus in CRISPR research, with significant implications for therapeutic development.

Molecular Principles of PAM Engineering

Recent research combining molecular dynamics simulations with graph theory has revealed that efficient PAM recognition involves not only direct contacts between PAM-interacting residues and DNA but also a distal network that stabilizes the PAM-binding domain and preserves long-range communication [13]. Key findings include:

- The D1135V/E substitution in Cas9 variants enables stable DNA binding by K1107 and preserves key DNA phosphate locking interactions via S1109 [13].

- PAM recognition requires local stabilization, distal coupling, and entropic tuning, rather than being a simple consequence of base-specific contacts [13].

- Variants carrying only R-to-Q substitutions at PAM-contacting residues, though predicted to enhance adenine recognition, often destabilize the PAM-binding cleft and disrupt allosteric coupling to the HNH nuclease domain [13].

Bioinformatics Tools for PAM Comparison and Application

The growing diversity of Cas nucleases with different PAM requirements has created a need for specialized bioinformatics tools. CATS (Comparing Cas9 Activities by Target Superimposition) automates the detection of overlapping PAM sequences across different Cas9 nucleases and identifies allele-specific targets, particularly those arising from pathogenic mutations [12].

Table 3: Bioinformatics Tools for PAM Analysis and Application

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATS | Comparing Cas9 Activities by Target Superimposition | Detects overlapping PAM sequences; integrates ClinVar data for pathogenic mutations | Allele-specific targeting for autosomal dominant disorders [12] |

| CRISPOR | Guide RNA design and off-target prediction | Provides PAM-specific guide RNA recommendations | General CRISPR experiment design |

| CHOPCHOP | Target selection for CRISPR editing | Includes PAM requirements in target identification | General CRISPR experiment design |

| Cas-designer | Guide RNA design tool | Accounts for PAM constraints in guide design | General CRISPR experiment design |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Standardized PAM communication and expanded PAM compatibility directly impact the development of CRISPR-based therapeutics, with several approaches already advancing to clinical trials.

PAM Considerations in Approved Therapies

Casgevy, the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, utilizes ex vivo editing of patients' hematopoietic stem cells [15] [16]. The PAM requirement directly influences which specific genomic sequences can be targeted for therapeutic gene modification.

Emerging Approaches for PAM-Independent Detection

For diagnostic applications, the TRACER (mutant target-recognized PAM-independent CRISPR-Cas12a enzyme reporting system) platform enables PAM-independent nucleic acid detection by converting double-stranded DNA to single-stranded DNA, which Cas12a can recognize without PAM requirements [17]. This approach significantly expands the applicability of CRISPR diagnostics for detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in cancer and other genetic disorders.

The guide-centric framework for standardizing PAM communication establishes a consistent lexicon for describing PAM sequences and their locations relative to target sites. This standardization enables more accurate comparison between CRISPR systems, facilitates the development of novel nucleases with expanded targeting capabilities, and supports the advancement of CRISPR-based therapeutics. As the CRISPR field continues to evolve, adopting universal standards for reporting fundamental parameters like PAM orientation will be essential for translating basic research into clinical applications that address unmet medical needs.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) represents a critical sequence requirement for CRISPR-Cas systems, serving as the primary determinant of target recognition and DNA cleavage capability. This technical guide comprehensively explores the diverse PAM requirements across natural and engineered Cas nucleases, detailing the experimental methodologies for PAM characterization and the computational tools enabling nuclease selection. Within the broader thesis of CRISPR targeting research, PAM diversity emerges not as a limitation but as a foundational feature that can be harnessed and engineered to expand the targeting landscape of genome editing technologies. The expanding repertoire of Cas proteins with unique PAM specificities, including AI-designed editors like OpenCRISPR-1, provides researchers with an unprecedented toolkit for precise genetic interventions in both basic research and therapeutic development.

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, providing defense against invading genetic elements such as viruses and plasmids [1] [18]. This system has been repurposed as a revolutionary genome engineering technology that relies on two fundamental components: a Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the nuclease to a specific DNA target sequence [19]. However, successful target recognition and cleavage requires more than just gRNA-DNA complementarity; it necessitates the presence of a short, specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target site known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [11].

The PAM serves a crucial biological function in self versus non-self discrimination, preventing the CRISPR system from targeting the bacterium's own genome [11]. From a practical standpoint, the PAM requirement represents both a constraint and a defining feature for CRISPR-based applications, as it fundamentally determines which genomic locations can be targeted [1] [20]. The sequence, length, and position of the PAM vary significantly across different Cas nucleases, creating a diverse targeting landscape that researchers must navigate for experimental success.

PAM Characteristics and Recognition Mechanisms

Molecular Basis of PAM Recognition

PAM recognition occurs through direct protein-DNA interactions, where specific domains within the Cas nuclease bind to short DNA sequences flanking the target site [11] [3]. Upon PAM binding, Cas proteins undergo conformational changes that enable DNA unwinding and subsequent interrogation of the adjacent sequence by the gRNA [3]. Sufficient complementarity between the gRNA spacer and target DNA then triggers cleavage by the nuclease domains. The absence of a compatible PAM prevents target recognition entirely, even with perfect gRNA complementarity [11].

The location of the PAM relative to the target sequence varies by CRISPR system type. For Type II systems (including Cas9), the PAM is typically located 3' downstream of the target sequence, while for Type V systems (including Cas12a), it is generally found 5' upstream [11]. The PAM is not included in the gRNA sequence but must be present in the genomic DNA being targeted [2].

PAM Diversity Across CRISPR Systems

The compelling need to target specific genomic regions, especially for therapeutic applications where precise editing is crucial, has driven the exploration and engineering of Cas nucleases with diverse PAM requirements [20]. This diversity manifests in several dimensions:

- Sequence Specificity: PAMs range from permissive sequences like SpRY's NRN (where R is A or G) to highly specific sequences such as NmeCas9's NNNNGATT [20] [19].

- Length Variation: PAM sequences vary from 2-6 nucleotides, with longer PAMs generally conferring higher specificity but reducing targetable sites [11].

- Positional Requirements: The location of the PAM relative to the protospacer differs between Cas protein families, influencing gRNA design parameters [11].

Comprehensive Landscape of Cas Nuclease PAM Requirements

Natural Cas Nucleases and Their PAM Sequences

Table 1: Natural Cas Nucleases and Their PAM Requirements

| Cas Nuclease | Source Organism | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Size (aa) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | 1368 | Gold standard; high activity [1] [19] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT (R=G/A) | 1053 | Compact size; AAV compatible [20] |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | 1082 | Longer PAM; increased specificity [12] [20] |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC (R=G/A, Y=C/T) | 984 | Very compact; AAV compatible [12] [20] |

| StCas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | NNAGAAW (W=A/T) | 1121 | Alternative specificity [20] |

| ScCas9 | Streptococcus canis | NNG | ~1368 | Reduced stringency vs SpCas9 [20] |

| LbCas12a | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV (V=G/A/C) | 1228 | Creates staggered ends; minimal tracrRNA [20] |

| AsCas12a | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV | ~1300 | Creates staggered ends [20] |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | 1109 | Thermostable; compact [20] |

Engineered and AI-Designed Cas Variants

Table 2: Engineered and AI-Designed Cas Variants with Altered PAM Preferences

| Cas Variant | Parent Nuclease | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Key Characteristics | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| xCas9 | SpCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT | Expanded PAM range; increased fidelity [19] | Gene knockouts; therapeutic editing |

| SpCas9-NG | SpCas9 | NG | Reduced PAM stringency [19] | Targeting gene-rich regions |

| SpRY | SpCas9 | NRN (preferred), NYN | Near-PAMless [12] [19] | Maximum targeting flexibility |

| eSpCas9(1.1) | SpCas9 | NGG | High-fidelity; reduced off-targets [19] | Therapeutic applications |

| SpCas9-HF1 | SpCas9 | NGG | High-fidelity; disrupted backbone interactions [19] | Therapeutic applications |

| hfCas12Max | Cas12i (engineered) | TN, TNN | High-fidelity; compact size; staggered ends [20] | In vivo therapeutics (e.g., HG302 for DMD) |

| eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | Parasutterella secunda (engineered) | Not specified | High-fidelity; retained on-target activity [20] | Clinical therapeutic development |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-generated | Not specified (compatible with base editing) | 400 mutations from natural sequences; comparable or improved activity/specificity vs SpCas9 [10] | Broad ethical use across research and commercial applications |

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have enabled the design of novel genome editors that substantially expand functional sequence space. By training large language models on 1.24 million CRISPR operons from 26 terabases of genomic and metagenomic data, researchers have generated Cas9-like effectors with 4.8× the protein cluster diversity found in nature [10]. These AI-designed editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, maintain functionality despite being approximately 400 mutations away from any natural sequence, demonstrating comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while offering compatibility with base editing applications [10].

Experimental Methodologies for PAM Characterization

GenomePAM: Direct PAM Characterization in Mammalian Cells

The GenomePAM method represents a significant advancement for characterizing PAM requirements directly in mammalian cells, overcoming limitations of in silico predictions and in vitro assays that may not accurately reflect cellular conditions [14].

Principle: GenomePAM leverages highly repetitive sequences in the mammalian genome that are flanked by diverse sequences. These repeats serve as naturally occurring target site libraries, with the constant repeat sequence functioning as the protospacer and the variable flanking sequences enabling PAM identification [14].

Protocol:

- Target Identification: Identify repetitive sequences (e.g., Rep-1: 5'-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3') with highly diverse flanking regions occurring thousands of times in the genome.

- gRNA Construction: Clone the repeat sequence (Rep-1 for 3' PAMs, Rep-1RC for 5' PAMs) into a gRNA expression cassette.

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T) with plasmids encoding the candidate Cas nuclease and the repeat-targeting gRNA.

- DSB Capture: Adapt the GUIDE-seq method to capture cleaved genomic sites using double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) that integrate into DSBs.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence integrated fragments using anchor multiplex PCR sequencing (AMP-seq), then extract and analyze PAM sequences flanking the target sites.

- Motif Identification: Use iterative "seed-extension" methods to identify statistically significant enriched motifs, reporting percentages of edited genomic sites at each iteration [14].

Advantages:

- No requirement for protein purification or synthetic oligo libraries

- Direct assessment in relevant cellular contexts

- Simultaneous evaluation of on-target efficiency and off-target specificity

- Captures impact of chromatin accessibility on nuclease activity [14]

Figure 1: GenomePAM Workflow for PAM Characterization in Mammalian Cells

Traditional PAM Identification Methods

Several established methods continue to provide valuable PAM characterization data:

In Vitro Cleavage Selection: A randomized DNA library containing potential PAM sequences is incubated with purified Cas nuclease. Cleaved products are selectively amplified and sequenced to identify functional PAMs [18] [3]. While this approach allows exploration of large sequence spaces (>10¹² molecules), it may not reflect cellular conditions where chromatin structure and protein concentrations differ [18].

Bacterial-Based Screening (PAM-SCANR): This method uses a catalytically dead Cas variant (dCas9) coupled to a repression system in bacteria. When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM site, it represses GFP expression, enabling sorting of cells by FACS and subsequent sequencing of functional PAMs [3].

In Silico Analysis: Bioinformatic analysis of protospacers from phage genomes and matching spacers from bacterial CRISPR arrays can identify conserved PAM motifs. While rapid, this method relies on available sequence data and cannot distinguish between acquisition and interference PAMs [3].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PAM Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Plasmids | Delivery of Cas nuclease to cells | Codon-optimized versions for target organisms; various promoters (EF1α, Cbh, U6) |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | gRNA expression and delivery | Multiplex capabilities; various RNA Polymerase III promoters |

| PAM Characterization Kits | Experimental PAM determination | GenomePAM components; GUIDE-seq kits; in vitro cleavage assay reagents |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PAM prediction and nuclease selection | CATS, CRISPRTarget, Cas-Designer, CRISPOR |

| AI-Based Design Platforms | Novel nuclease generation | ProGen2 models trained on CRISPR-Cas Atlas; family-specific fine-tuned LMs |

| Delivery Vehicles | Cellular delivery of editing components | AAVs (for small Cas variants), LNPs, electroporation systems |

Computational Tools for PAM Analysis and Nuclease Selection

CATS (Comparing Cas9 Activities by Target Superimposition): This bioinformatic tool automates detection of overlapping PAM sequences across different Cas9 nucleases, enabling fair comparison by identifying common target sites not biased by natural genetic landscapes [12]. CATS integrates ClinVar data to facilitate targeting of disease-causing mutations and supports allele-specific targeting approaches for autosomal dominant disorders [12].

CRISPRTarget: Web tool that identifies potential targets in sequenced genomes using spacer sequences, helping to determine natural PAM sequences through bioinformatic analysis [3].

PAM Wheel Visualization: A specialized visualization method using Krona plots to depict all individual PAM sequences with enrichment scores, providing comprehensive overview of PAM diversity for promiscuous nucleases [3].

Discussion: Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

The expanding landscape of PAM diversity has profound implications for CRISPR research and therapeutic development. The fundamental thesis that PAM requirements define targeting capability has driven both the discovery of natural variants and the engineering of novel nucleases with expanded targeting ranges.

Strategic Nuclease Selection

Researchers can now select nucleases based on specific experimental needs:

- Therapeutic Applications: Compact, high-fidelity nucleases like SaCas9, hfCas12Max, and eSpOT-ON enable AAV delivery with reduced immunogenicity and improved safety profiles [20].

- High-Specificity Requirements: Nucleases with longer PAMs (e.g., NmeCas9) or high-fidelity engineered variants offer reduced off-target effects crucial for clinical applications [19].

- Maximum Targeting Flexibility: Near-PAMless variants like SpRY and AI-designed editors provide access to previously inaccessible genomic regions [10] [19].

- Multiplexed Editing: Cas12 variants with minimal direct repeat requirements facilitate efficient multiplexing for complex engineering applications [19].

Future Directions

The integration of artificial intelligence in nuclease design represents a paradigm shift from mining natural diversity to generating optimized editors de novo. The successful deployment of OpenCRISPR-1 demonstrates that machine learning models trained on CRISPR sequence diversity can produce functional editors that bypass evolutionary constraints [10]. This approach promises to rapidly expand the available toolkit with nucleases tailored for specific properties such as size, specificity, temperature stability, and PAM preferences.

Ongoing challenges include comprehensive characterization of newly discovered and engineered nucleases, understanding the relationship between PAM stringency and off-target effects, and developing delivery strategies for the most promising variants. As the PAM landscape continues to diversify, researchers will gain increasingly precise control over genomic targeting, accelerating both basic research and therapeutic development.

From Theory to Bench: PAM Characterization and Experimental Design Strategies

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows the target DNA region recognized by the CRISPR-Cas system. This motif is absolutely required for a Cas nuclease to cleave its target and is generally found 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the cut site [1]. The fundamental biological purpose of the PAM sequence is to enable the CRISPR system to distinguish between "self" and "non-self" genetic material. In bacterial adaptive immunity, this discrimination prevents the Cas nuclease from attacking the bacterium's own genome, which contains matching spacer sequences but lacks the required adjacent PAM sequence [1] [3]. From an application perspective, the PAM sequence represents a significant constraint on CRISPR genome engineering, as it limits the genomic locations that can be targeted for editing. Consequently, characterizing and engineering PAM requirements has become a central focus in expanding the targeting capabilities of CRISPR systems for research and therapeutic applications [1] [21].

Table 1: Common CRISPR Nucleases and Their PAM Sequences

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| LbCas12a (Cas12a) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| Cas3 | in silico analysis of various prokaryotic genomes | No PAM sequence requirement |

Traditional PAM Identification Methods and Their Limitations

Early methods for PAM identification employed various approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. In silico methods involved computational alignments of protospacers to identify consensus PAM elements through tools like CRISPRFinder and CRISPRTarget [3]. While fast and accessible, these methods rely on the availability of sequenced phage genomes and cannot distinguish between spacer acquisition motifs (SAMs) and target interference motifs (TIMs) [3]. Plasmid depletion assays represented an early experimental approach, where a randomized DNA stretch was inserted adjacent to a target sequence within a plasmid transformed into a host with an active CRISPR-Cas system. Plasmids with "inactive" PAM sequences that were not cleaved would be retained and identified via sequencing [3]. The PAM-SCANR (PAM screen achieved by NOT-gate repression) method utilized a catalytically dead Cas9 variant (dCas9) coupled to a GFP reporter – when dCas9 bound to a functional PAM, GFP expression was diminished, enabling identification of functional PAM motifs through FACS sorting and sequencing [3]. In vitro cleavage assays involved incubating purified Cas effector complexes with DNA libraries containing randomized PAM sequences, followed by sequencing of cleaved products [3]. While offering control over reaction conditions, these methods require laborious protein purification and may not reflect in vivo conditions [14]. A significant limitation across these traditional approaches has been their limited translatability to mammalian cell contexts, where chromatin structure, DNA modifications, and cellular environment can significantly influence PAM recognition and cleavage efficiency [14] [4].

GenomePAM: A Revolutionary Method for Direct PAM Characterization in Mammalian Cells

Principle and Design of GenomePAM

The GenomePAM method represents a significant advancement by leveraging naturally occurring repetitive sequences in the mammalian genome for direct PAM characterization in mammalian cells [14]. This innovative approach identifies genomic repeats flanked by highly diverse sequences where the constant sequence serves as the protospacer for CRISPR-Cas editing experiments. The key insight was that certain repetitive elements in the human genome occur thousands of times with nearly random flanking sequences, creating a natural library of PAM candidates [14] [22]. Specifically, the researchers identified a 20-nt sequence (5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′, part of an Alu repeat termed 'Rep-1') that occurs approximately 8,471 times in the human haploid genome (~16,942 occurrences in a human diploid cell) with nearly random flanking sequences of 10-nt length at its 3' end [14]. This makes it an ideal candidate protospacer sequence for PAM identification. For type II Cas nucleases with 3' PAMs (such as SpCas9 and SaCas9), Rep-1 is used directly, while for type V Cas nucleases with 5' PAMs (such as FnCas12a), the reverse complementary sequence (Rep-1RC) serves as the protospacer [14].

Diagram 1: GenomePAM Workflow for PAM Characterization

Experimental Protocol for GenomePAM

The GenomePAM protocol begins with cloning the Rep-1 spacer sequence into a guide RNA (gRNA) expression cassette to be used alongside a plasmid encoding the candidate Cas nuclease [14]. These constructs are transfected into mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T cells), where the Cas nuclease cleaves Rep-1 sites containing functional PAM sequences. To identify which repeats within the genome were cleaved, the method adapts the GUIDE-seq (genome-wide unbiased identification of double strand breaks enabled by sequencing) technique, which captures cleaved genomic sites by enriching double strand oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN)-integrated fragments through anchor multiplex PCR sequencing (AMP-seq) [14]. The resulting sequencing data is analyzed with the candidate PAM initially set as unknown ('NNNNNNNNNN'), and cleaved sites are identified throughout the genome. An iterative 'seed-extension' method then identifies statistically significant enriched motifs and reports the percentages of edited genomic sites at each iteration step, generating comprehensive PAM preference profiles [14].

Validation and Applications of GenomePAM

GenomePAM has been successfully validated using Cas nucleases with well-established PAM requirements. For SpCas9, GenomePAM accurately identified the canonical NGG PAM at the 3' end [14]. For SaCas9, it confirmed the NNGRRT (where R is G or A) PAM, and for FnCas12a, it correctly identified the YYN (where Y is T or C) PAM at the 5' side of the spacer [14]. Beyond characterizing known nucleases, GenomePAM enables simultaneous comparison of activities and fidelities among different Cas nucleases on thousands of match and mismatch sites across the genome using a single gRNA [14] [22]. The method also provides insight into genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiles in different cell types, as chromatin state influences which target sites are effectively cleaved [14]. A significant advantage of GenomePAM is that it does not require protein purification or synthetic oligos, making PAM characterization more accessible and scalable while providing data directly relevant to mammalian cellular environments [14] [23].

Other Contemporary PAM Discovery Platforms

PAM-readID: A Rapid, Simple Alternative

PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides Integration in DNA double-stranded breaks) represents another recent method developed to address the need for mammalian cell-based PAM characterization [4]. This approach involves transfecting mammalian cells with three components: (1) a plasmid bearing a target sequence flanked by randomized PAMs, (2) a plasmid expressing the Cas nuclease and sgRNA, and (3) double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) [4]. After Cas cleavage and NHEJ repair-mediated dsODN integration (72 hours post-transfection), genomic DNA is extracted, and fragments containing recognized PAMs are amplified using one primer binding to the integrated dsODN and another binding to the target plasmid. These amplicons are then sequenced via high-throughput sequencing or analyzed by Sanger sequencing to generate PAM recognition profiles [4]. A notable advantage of PAM-readID is its sensitivity – an accurate PAM preference for SpCas9 can be identified with extremely low sequence depth (as few as 500 reads) – and its compatibility with Sanger sequencing, which significantly reduces time and cost requirements compared to other methods [4].

Diagram 2: PAM-readID Workflow for PAM Determination

High-Throughput PAM Determination Assay (HT-PAMDA)

The High-Throughput PAM Determination Assay (HT-PAMDA) is another method developed for scalable characterization of PAM preferences [14]. This approach utilizes a human cell expression system followed by an in vitro cleavage reaction, creating a hybrid method that combines cellular expression with controlled biochemical conditions [14]. While comprehensive in its profiling capabilities, HT-PAMDA requires protein purification steps, which can be technically demanding and time-consuming compared to more direct cellular methods like GenomePAM and PAM-readID [14].

AI-Driven and Directed Evolution Approaches

Beyond experimental PAM characterization methods, innovative approaches are being employed to engineer novel Cas nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Directed evolution combined with rational engineering has successfully generated Cas12a variants with expanded PAM recognition [21]. In one study, researchers used error-prone PCR to generate random mutations in the PAM-interacting (PI) and wedge (WED) domains of Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a), followed by selection using a dual-bacterial system with crRNAs designed to direct cleavage at target sequences adjacent to noncanonical PAMs [21]. This approach yielded Flex-Cas12a, a variant carrying six mutations (G146R, R182V, D535G, S551F, D665N, and E795Q) that recognizes 5'-NYHV-3' PAMs, expanding potential genome accessibility from ~1% to over 25% while retaining efficient cleavage at canonical 5'-TTTV-3' sites [21]. Artificial intelligence has also emerged as a powerful tool for designing novel genome editors. Large language models trained on biological diversity at scale have successfully generated functional CRISPR-Cas proteins, with some AI-designed editors exhibiting comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Modern PAM Discovery Methods

| Method | Principle | Cellular Context | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenomePAM | Uses genomic repetitive sequences as natural PAM library | Mammalian cells | No protein purification or synthetic oligos needed; assesses thousands of sites simultaneously | Limited to available repetitive sequences |

| PAM-readID | dsODN integration at Cas cleavage sites | Mammalian cells | Works with low sequencing depth; compatible with Sanger sequencing | Requires dsODN design and integration |

| HT-PAMDA | Cell expression followed by in vitro cleavage | Hybrid (cellular + in vitro) | Controlled biochemical conditions | Requires protein purification steps |

| Directed Evolution | Random mutagenesis + selection for desired PAM recognition | Bacterial cells | Can dramatically expand PAM recognition | Multiple selection rounds needed; potential tradeoffs in activity |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for PAM Discovery

Implementing contemporary PAM discovery methods requires specific research reagents and tools. The following table summarizes key components essential for conducting these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM Discovery Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function in PAM Discovery | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Repetitive Genomic Sequences | Serve as natural protospacer libraries | Rep-1 (5′-GTGAGCCACTGTGCCTGGCC-3′); ~16,942 copies in human diploid cells |

| Guide RNA Expression Vectors | Express gRNAs targeting repetitive sequences | Plasmid-based systems with appropriate promoters (U6) |

| Cas Nuclease Expression Constructs | Provide Cas protein for cleavage assays | Codon-optimized for mammalian cells with nuclear localization signals |

| Double-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) | Tag cleaved genomic sites for detection | 5'-phosphorylated, 3'-blocked dsODNs for GUIDE-seq and PAM-readID |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Sequence captured PAM fragments | Illumina, PacBio, or other NGS platforms |

| Cell Lines | Provide cellular context for PAM characterization | HEK293T, HepG2, or other relevant mammalian cell lines |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Analyze sequencing data and identify PAM motifs | CRISPResso2, custom scripts for seed-extension analysis |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Research Applications

The advancement of PAM discovery methods has profound implications for therapeutic development and research applications. For genetic therapies, expanded PAM compatibility enables targeting of a wider range of disease-causing mutations, including those in genetically "hard-to-reach" regions [21] [4]. High-throughput CRISPR screens leveraging these improved targeting capabilities are transforming medical research by identifying potential drug targets for both infectious and non-infectious diseases, revealing mechanisms involved in antibiotic resistance, host-pathogen interactions, cancer progression, and drug response [24]. In agricultural biotechnology, CRISPR-based massively parallel genome editing has enabled increases in crop yield and tolerance to abiotic/biotic stresses, with consequent improvements in fitness and adaptability [24]. The integration of CRISPR with other high-throughput techniques continues to open new opportunities for research and development across diverse areas, presenting innovative solutions to long-standing challenges in health, agriculture, and biotechnology [24].

The evolution of PAM discovery methods from traditional computational alignments and plasmid depletion assays to innovative approaches like GenomePAM and PAM-readID represents significant progress in CRISPR technology. These contemporary methods enable more accurate characterization of PAM requirements directly in mammalian cells, providing data more relevant to therapeutic applications. Combined with AI-driven protein design and directed evolution approaches, these PAM discovery platforms are expanding the targeting range and specificity of CRISPR systems, opening new possibilities for basic research and clinical applications. As these technologies continue to mature, they will further accelerate the development of novel genome editing tools with enhanced capabilities, ultimately advancing both fundamental biological understanding and translational applications across medicine and biotechnology.

Bioinformatic Tools for PAM Prediction and Guide RNA Design

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a critical short DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR system [1] [25]. This sequence serves as the essential recognition signal for Cas effector proteins, enabling them to identify and bind to foreign DNA while avoiding self-genome targeting [1] [11]. The PAM's location is typically 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the Cas nuclease cut site, and its presence is absolutely required for successful CRISPR-mediated genome editing [1] [25].

In bacterial adaptive immunity, the PAM provides the fundamental mechanism for self versus non-self discrimination [1] [3]. When a virus attacks bacteria, surviving cells incorporate a fragment of viral DNA (protospacer) into their CRISPR array, but notably exclude the PAM sequence [1]. This ensures that when the Cas nuclease complexes with guide RNA to scan for future infections, it will only cleave sequences containing both the complementary target AND the adjacent PAM, thus preventing autoimmunity against the bacterial genome [1] [11]. This biological mechanism has profound implications for CRISPR experiment design, as target sites without appropriate PAM sequences will not be edited regardless of guide RNA complementarity [1] [25].

The recent development of artificial-intelligence-enabled design represents a paradigm shift in CRISPR tool development. Large language models trained on biological diversity at scale have successfully generated programmable gene editors with optimal properties, including novel PAM specificities [10]. One such AI-generated editor, OpenCRISPR-1, exhibits compatibility with base editing while being 400 mutations away in sequence from the prototypical SpCas9 [10]. This demonstrates how computational approaches are bypassing evolutionary constraints to expand CRISPR targeting capabilities.

Bioinformatics Tools for PAM Prediction and Guide RNA Design

The complexity of CRISPR experiments has driven the development of numerous bioinformatics tools specifically designed for PAM prediction and guide RNA design. These tools address critical parameters including PAM identification, on-target efficiency prediction, and off-target effect minimization [26] [27].

Table 1: Major Bioinformatics Tools for CRISPR Experiment Design

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATS | Compares Cas9 nucleases with different PAM requirements | Detects overlapping PAM sequences; Integrates ClinVar data for allele-specific targeting [28] | Nuclease selection for clinical applications; Targeting disease-causing mutations [28] |

| CRISPOR | Guide RNA design and selection | Implements Doench rules for on-target activity prediction; Off-target effect scoring [26] [27] | Knockout experiments; Optimizing guide RNA efficiency [26] |

| CHOPCHOP | Target site selection and guide design | Provides predicted indel frequency; User-friendly interface [26] [28] | Gene knockout studies; Multiplexed editing [26] |

| CRISPResso | Analysis of editing outcomes | Quantifies editing efficiency; Detects insertion-deletion patterns [26] [4] | Validation of editing experiments; Quality control [26] |

| Synthego Design Tool | Guide RNA design for knockouts | Supports 120,000 genomes and 9,000 species; Reduces design time to minutes [27] | High-throughput knockout screening [27] |

| Benchling CRISPR Tool | Integrated guide and template design | Latest scoring algorithms; 100X faster than competitors [27] | Knock-in experiments; Homology-directed repair [27] |

These tools employ sophisticated algorithms to predict guide RNA efficacy based on factors such as sequence composition, genomic context, and epigenetic features [26]. The "Doench rules," developed through analysis of thousands of guide RNAs, are implemented in several platforms to predict on-target activity and minimize off-target effects [27]. When selecting tools, researchers should consider whether their experimental goal involves gene knockout, knock-in, activation (CRISPRa), or inhibition (CRISPRi), as each application has distinct design requirements [27].

For knockout experiments, tools typically prioritize target sites in exons crucial for protein function, avoiding regions too close to N- or C-termini where edits might not completely disrupt gene function [27]. In contrast, knock-in experiments require more precise positioning relative to the donor template, with efficiency dramatically dropping when the cut site is not close to the repair template [27]. CRISPRa and CRISPRi applications targeting promoter regions have particularly narrow location requirements, necessitating careful balance between sequence complementarity and optimized positioning [27].

Experimental Protocols for PAM Characterization

Understanding the experimental methods for PAM determination is essential for researchers developing novel CRISPR nucleases or applying established systems in new contexts. Several well-established protocols exist for characterizing PAM requirements across different experimental environments.

PAM-ReadID: Mammalian Cell-Based PAM Determination

The PAM-readID (PAM REcognition-profile-determining Achieved by DsODN Integration in DNA double-stranded breaks) method provides a rapid, simple approach for determining PAM recognition profiles directly in mammalian cells [4]. This protocol addresses the critical need for cell-based characterization, as PAM preferences can show intrinsic differences between in vitro and cellular environments due to variations in DNA topology and modification [4].

Protocol Steps:

- Construct plasmids for the cleavage reaction: (I) plasmid bearing target sequence flanked by randomized PAMs, (II) plasmid expressing Cas nuclease and sgRNA [4]

- Transfect mammalian cells with the plasmids and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODN)

- Extract genomic DNA after 72 hours to allow for Cas9 cleavage and NHEJ repair-mediated dsODN integration

- Amplify target fragments using one upstream primer for dsODN and one downstream primer for the target plasmid

- Sequence amplicons via high-throughput sequencing (HTS) or Sanger sequencing

- Analyze sequences to produce the PAM recognition profile [4]

This method successfully characterized PAM preferences for SaCas9, SaHyCas9, Nme1Cas9, SpCas9, SpG, SpRY, and AsCas12a in mammalian cells, identifying both canonical and non-canonical PAM sequences [4]. The technique can generate accurate PAM profiles with as few as 500 sequencing reads, making it accessible for laboratories without extensive sequencing capabilities [4].

In Vitro PAM Determination Assay

For initial characterization of novel Cas nucleases, in vitro approaches provide a controlled environment for PAM identification [3]. This method involves:

Protocol Steps:

- Prepare target DNA library containing randomized PAM sequences

- Incubate library with purified Cas effector complexes

- Isolate cleaved products through gel extraction or size selection

- Amplify and sequence cleaved fragments

- Bioinformatic analysis to identify enriched PAM sequences in cleaved products [3]

This approach allows for testing of large initial libraries under controlled conditions but requires purified, stable effector complexes and may not fully recapitulate in vivo activity [3].

Plasmid Depletion Assay (Bacterial Systems)

For bacterial CRISPR systems, plasmid depletion assays provide a reliable method for PAM identification:

Protocol Steps:

- Construct plasmid library with randomized DNA adjacent to target sequence

- Transform library into host with active CRISPR-Cas system

- Recover plasmids after selection period

- Sequence plasmids to identify depleted PAM sequences (functional PAMs lead to plasmid cleavage and loss) [3]

This method identifies functional PAMs through negative selection and has been widely used for characterizing Type I and II systems in bacterial contexts [3].

Decision Framework for PAM Determination Methods

PAM Sequences Across CRISPR Systems

Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, which directly impacts their targeting range and applications. The table below summarizes PAM requirements for commonly used and emerging CRISPR systems.

Table 2: PAM Sequences for Various CRISPR-Cas Systems

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Targeting Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG [1] [25] | Most widely used; requires G-rich PAM |

| SpCas9 D10A | Engineered (SpCas9 variant) | NGG [29] | Nickase; reduced off-target effects |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN [1] [4] | Compact size for viral delivery |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT [1] | Longer PAM; high specificity |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV [1] [29] | T-rich region targeting; staggered cuts |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN [1] | Thermostable; diagnostic applications |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered (Cas12 variant) | TN and/or TNN [1] | Engineered PAM flexibility |

| SpRY | Engineered (SpCas9 variant) | NRN > NYN [28] [4] | Near-PAMless; greatly expanded targeting |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-generated | Customizable [10] | Designed for optimal properties |

The PAM sequence directly influences the targetable genomic space. For example, SpCas9's NGG PAM occurs approximately once every 8 base pairs in random DNA, while Cas12a's TTTV PAM provides better targeting in AT-rich regions [1] [29]. Emerging technologies like SpRY and AI-designed nucleases are significantly expanding targeting capabilities by relaxing PAM requirements [10] [28] [4].

Engineering efforts have focused on modifying PAM specificities through directed evolution and structure-guided mutagenesis [1] [11]. For instance, SpCas9 variants like SpG and SpRY recognize increasingly relaxed PAM sequences, with SpRY effectively functioning as a near-PAMless editor [4]. These advances are particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where targeting specific sequences is essential but natural PAMs may be unavailable.

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

Successful CRISPR experimentation requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential components and their functions in typical genome editing workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease | Choice depends on PAM requirements, size constraints, and specificity [1] [29] |

| Guide RNA | Target recognition molecule | Chemically modified versions improve stability and reduce toxicity [29] [27] |

| HDR Donor Template | Repair template for precise edits | ssODN templates with 30-40 nt homology arms optimize HDR efficiency [29] |