OTUs vs. ASVs: A Researcher's Guide to Microbiome Data Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical choice between Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) in marker-gene sequencing analysis.

OTUs vs. ASVs: A Researcher's Guide to Microbiome Data Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical choice between Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) in marker-gene sequencing analysis. We cover foundational concepts, technical principles, and practical applications, drawing on current scientific literature to compare the performance, advantages, and limitations of each method. The content addresses key considerations for methodological selection, troubleshooting common issues, and validating findings, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical and clinical research, including biomarker discovery, translational applications, and study reproducibility.

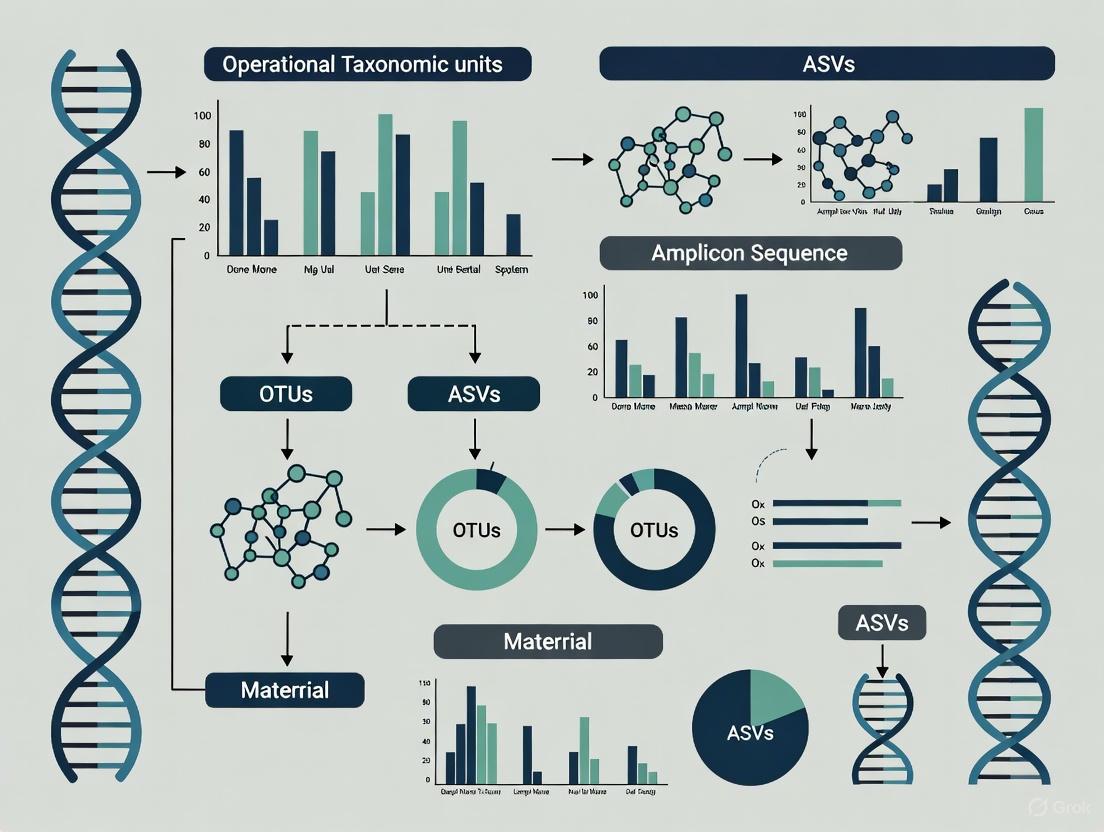

OTUs and ASVs Explained: Core Concepts and Technical Foundations

In the field of microbial ecology, the accurate characterization of community diversity relies on defining discrete units from sequencing data. For years, Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) served as the foundational method for grouping sequences and estimating taxonomic abundance. However, a paradigm shift is underway with the rise of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which offer single-nucleotide resolution. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of both approaches, framing them within the broader context of modern microbiome research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts: From Clustering to Exact Variants

What Are OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units)?

An Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) is a cluster of similar marker gene sequences, typically defined by a 97% similarity threshold [1] [2]. This method groups sequences that are at least 97% identical into a single unit, which historically was believed to approximate species-level differences in microbial communities [1]. The primary purpose of OTU clustering is to reduce the complexity of sequencing data by grouping together similar sequences, which also helps smooth out minor variations caused by sequencing artifacts [1] [2].

The standard process for generating OTUs involves:

- Sequence Preprocessing: Quality filtering of raw sequencing reads.

- Clustering: Using algorithms like UCLUST, VSEARCH, or mothur to group sequences based on pairwise similarity [3] [2].

- Chimera Removal: Filtering out artificially fused sequences generated during PCR amplification [2].

- Representative Sequence Selection: Picking one sequence to represent the entire cluster for downstream taxonomic annotation [2].

What Are ASVs (Amplicon Sequence Variants)?

An Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) is a unique, error-corrected sequence read obtained through a process called "denoising" [1] [3]. Unlike OTUs, ASVs are not clustered based on arbitrary similarity thresholds. Instead, they represent biological sequences inferred from the data after accounting and correcting for sequencing errors [1]. ASVs provide single-nucleotide resolution, allowing researchers to distinguish between closely related microbial strains [1].

The generation of ASVs relies on sophisticated denoising algorithms:

- DADA2: Models and corrects Illumina sequencing errors to infer real biological sequences [1] [3].

- Deblur: Uses error profiles to subtract sequencing errors from the data [4].

- UNOISE3: A algorithm within the USEARCH package that also performs denoising, with its results sometimes referred to as ZOTUs [3].

OTUs vs. ASVs: A Technical Comparison

The choice between OTUs and ASVs involves trade-offs between resolution, error handling, and computational demand. The table below provides a structured comparison of their core features.

Table 1: A Comparative Overview of OTUs and ASVs

| Feature | OTU | ASV |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Clusters sequences at ~97% similarity [1] | Single-nucleotide precision [1] |

| Basis of Definition | Similarity-based clustering [3] | Denoising and error-correction [1] [3] |

| Error Handling | Errors can be absorbed into clusters [1] | Explicitly models and removes sequencing errors [1] |

| Reproducibility | Can vary between studies and parameters [1] | Highly reproducible across studies (exact sequences) [1] |

| Computational Cost | Generally lower [1] | Higher due to complex denoising algorithms [1] |

| Primary Tool Examples | UPARSE, VSEARCH, mothur [3] [4] | DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3 [1] [4] |

Advantages and Disadvantages

- OTU Advantages & Disadvantages: The OTU approach is computationally efficient and somewhat tolerant of sequencing errors [1]. Its main drawback is the loss of biological resolution due to clustering, which can merge distinct but closely related species or strains [1]. Furthermore, the 97% threshold is arbitrary and may not hold true for all microbial taxa [1].

- ASV Advantages & Disadvantages: The key advantage of ASVs is their high resolution and reproducibility, facilitating direct comparison between different studies [1]. The main disadvantages are increased computational requirements and a potential for "over-resolution," where biologically insignificant variants (e.g., resulting from PCR errors) are retained, though algorithms are designed to mitigate this [1].

Methodological Workflows

The analytical pipelines for deriving OTUs and ASVs from raw sequencing data involve distinct steps and algorithms. The following workflows illustrate the standard procedures for each approach.

OTU Clustering Workflow

ASV Denoising Workflow

Algorithm Performance and Experimental Insights

A comprehensive study published in Environmental Microbiome compared the performance of four ASV denoising methods (DADA2, Deblur, MED, UNOISE3) and four OTU clustering methods (UPARSE, average neighborhood, Opticlust, VSEARCH) using defined mock microbial communities [4]. This provides a quantitative framework for evaluating these tools.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Common OTU and ASV Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | Microbial Composition Accuracy | Error Rate | Tendency | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | ASV (Denoising) | High [4] | Low [4] | Some over-splitting [4] | Moderate [4] |

| UPARSE | OTU (Clustering) | High [4] | Low [4] | Balanced merging/splitting [4] | Lower [4] |

| Deblur | ASV (Denoising) | Good for diversity [4] | Low [4] | - | Long execution time [4] |

| UNOISE3 | ASV (Denoising) | Lower accuracy [4] | Higher [4] | More errors [4] | - |

| MED | ASV (Denoising) | Lower accuracy [4] | Higher [4] | More errors [4] | High memory & time [4] |

Key Findings from Comparative Studies

- Accuracy and Error Profile: DADA2 and UPARSE consistently demonstrated high accuracy in reconstructing the known composition of mock communities, with low overall error rates [4]. In contrast, MED and UNOISE3 showed higher error rates and poorer performance in correctly assigning sequences [4].

- Diversity Estimation: In alpha and beta diversity analyses, DADA2 and Deblur produced results most similar to the theoretical expectations of the mock communities. Among clustering methods, UPARSE also showed high similarity to expected diversity metrics [4].

- Practical Recommendations: The study suggests that ASV algorithms like DADA2 are excellent for providing consistent sequence variants across studies, making them suitable for meta-analyses. However, their default parameters can sometimes lead to over-splitting. OTU methods like UPARSE, while potentially less resolved, can be more robust for studying poorly characterized microbial environments where major community shifts are expected, as they effectively balance the merger and split of sequences [4].

Successful implementation of OTU or ASV-based analysis requires a suite of reliable software, databases, and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Amplicon Sequence Analysis

| Category | Item | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Pipelines | QIIME 2 | Integrated pipeline for processing raw data to diversity analysis, supports both OTUs and ASVs [5]. | https://qiime2.org/ |

| EasyAmplicon 2 | Modular Snakemake pipeline optimized for Illumina, PacBio, and Nanopore long-read amplicon data [6]. | https://github.com/YongxinLiu/EasyAmplicon | |

| DNA Extraction | Commercial Kits | High-yield, stable DNA extraction from complex samples (soil, roots). | FastDNATM SPIN Kit [7] |

| PCR Amplification | High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces PCR errors during library preparation. | Thermo Scientific Phusion Polymerase [7] |

| Reference Databases | SILVA / Greengenes | Curated 16S rRNA gene databases for taxonomic annotation [5] [8]. | https://www.arb-silva.de/ |

| MaarjAM | Specialized database for the identification of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) fungi [7]. | https://maarjam.botany.ut.ee/ | |

| Statistical & Visualization | R Package: vegan |

Performs essential ecological analyses like alpha/beta diversity [7]. | https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan |

R Package: edgeR |

Identifies differentially abundant features between sample groups [9]. | https://bioconductor.org/packages/edgeR/ |

The evolution from OTUs to ASVs marks a significant advancement in microbial bioinformatics, driven by the demand for higher resolution, greater reproducibility, and improved data sharing across studies [1]. While OTU-based approaches remain valuable for analyzing legacy datasets, conducting broad-scale ecological surveys, or working with limited computational resources, ASV-based methods are now largely considered the preferred standard for most contemporary studies [1] [4].

The choice between OTU and ASV should be guided by the specific research question, the availability of computational resources, and the required level of taxonomic discrimination. For strain-level analysis or when integrating data from multiple studies, ASVs provide a clear advantage. However, for projects focused on high-level taxonomic trends or with computational constraints, OTU clustering can still yield robust ecological insights. As the field continues to evolve, the adoption of standardized, high-resolution units like ASVs will be crucial for deepening our understanding of microbial communities in health, disease, and the environment.

The analysis of microbial communities through marker gene sequencing, such as the 16S rRNA gene, is a cornerstone of modern microbial ecology. The bioinformatic processing of this data has undergone a significant paradigm shift, moving from the clustering of sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) to the generation of exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). This evolution is driven by the pursuit of greater resolution, reproducibility, and accuracy in characterizing microbiomes. This whitepaper details the historical context, methodological foundations, and quantitative outcomes of this transition, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape. Understanding the operational differences between these methods is crucial for the correct interpretation of microbial data in both basic research and applied therapeutic development [10] [11].

The Era of OTU Clustering: Rationale and Methods

2.1 The Problem of Sequencing Error The initial adoption of OTU clustering was a pragmatic solution to a technical challenge. Early high-throughput sequencing technologies were prone to errors in base calling. In targeted amplicon sequencing, where the goal is to differentiate between closely related organisms based on a small number of nucleotide variations, even a low error rate could lead to the misattribution of a sequence. A few erroneous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) could falsely suggest the presence of a new organism or cause a misclassification [11]. OTU clustering was developed to minimize this risk by grouping similar sequences, thereby "smoothing out" minor technical variations [10].

2.2 Clustering Methodologies and Workflows OTUs are clusters of sequences defined by a percent identity threshold, historically set at 97%, which was intended to approximate the species-level boundary in bacteria [10] [12]. The implementation of OTU clustering can be achieved through several approaches, each with distinct advantages and drawbacks.

- De Novo Clustering: This reference-free method clusters sequences based solely on their similarity to each other within a dataset. While it avoids biases from reference databases, it is computationally intensive, and results are not directly comparable across studies because the same sequence may cluster differently in different datasets [11].

- Closed-Reference Clustering: This method clusters sequences against a pre-defined reference database. It is computationally efficient and allows for easy comparison between studies using the same database. However, its major drawback is that sequences not found in the reference database are discarded, leading to a loss of novel diversity [11].

- Open-Reference Clustering: A hybrid approach that first uses closed-reference clustering and then clusters the remaining, unmatched sequences de novo. This aims to balance computational efficiency with the retention of novel taxa [11].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized OTU clustering workflow, as implemented in pipelines like MOTHUR.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of OTU Clustering Methodologies.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo Clustering [11] | Clusters sequences based on pairwise similarity within the dataset. | Retains all sequences, including novel taxa; no reference database bias. | Computationally intensive; results are study-dependent and not directly comparable. |

| Closed-Reference Clustering [10] [11] | Clusters sequences against a reference database. | Computationally fast; results are comparable across studies. | Discards novel sequences not in the database; subject to database errors and biases. |

| Open-Reference Clustering [11] | Combines closed-reference and de novo methods. | Balances efficiency and retention of novel diversity. | Intermediate computational cost; complexity of hybrid approach. |

The Shift to ASV Denoising: Principles and Drivers

3.1 Overcoming the Limitations of Clustering The OTU clustering approach, while useful, introduced several biases. The 97% threshold is arbitrary and does not consistently correspond to a specific taxonomic level [10]. More critically, clustering inherently underestimates true biological diversity by grouping distinct sequences together. As noted in a 2024 study, clustering 100-nucleotide reads at 97% identity theoretically has room to obscure up to 64 distinct sequence variants within a single OTU, potentially leading to a massive underestimation of genetic biodiversity [10].

3.2 The Denoising Principle The ASV approach represents a fundamental shift in philosophy. Instead of clustering sequences to minimize errors, denoising employs a model to distinguish true biological sequences from sequencing errors [13] [14]. ASVs are exact, error-corrected sequences that provide single-nucleotide resolution. Key algorithms in this field include:

- DADA2: Uses a parametric error model trained on the entire sequencing run to infer true sequences [13].

- Deblur: Uses an algorithm that employs an upper error rate bound and a constant probability of indels to remove predicted error-derived reads in a sample-by-sample manner [13].

- UNOISE3: A one-pass clustering strategy that does not depend on quality scores but uses pre-set parameters to generate "zero-radius OTUs" (synonymous with ASVs) [13].

A primary advantage of ASVs is their reproducibility. Because they represent exact sequences, the same biological variant will always result in the same ASV, enabling direct comparison across different studies [11]. The following workflow outlines the core steps in an ASV-based pipeline like DADA2.

Quantitative Comparative Analyses: OTUs vs. ASVs

Independent evaluations and comparative studies have quantified the performance differences between these two approaches across various metrics and sample types.

4.1 Impact on Diversity Metrics A 2022 study comparing DADA2 (ASV) and MOTHUR (OTU) pipelines on freshwater microbial communities found that the choice of pipeline significantly influenced alpha and beta diversity metrics, more so than other methodological choices like rarefaction or the specific OTU identity threshold (97% vs. 99%). The effect was most pronounced on presence/absence indices like richness and unweighted UniFrac [14].

A separate 2018 independent evaluation of denoising tools using mock communities found that while different pipelines (DADA2, UNOISE3, Deblur) produced similar microbial community compositions, the number of ASVs identified varied drastically, directly impacting alpha diversity metrics. DADA2 tended to find more ASVs than other denoising pipelines, suggesting a higher sensitivity for rare organisms, potentially at the expense of more false positives [13].

Table 2: Comparative Effects on Ecological Metrics Based on Empirical Studies [10] [14].

| Ecological Metric | OTU Clustering Effect | ASV Denoising Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha Diversity (Richness) | Underestimates true sequence diversity; can overestimate taxonomic richness due to spurious OTUs [10] [14]. | Provides higher, more accurate resolution; more sensitive to rare taxa but may infer false positives [13] [14]. |

| Beta Diversity | Can distort community similarity measurements [10]. | Results in more robust and coherent multivariate patterns [10] [14]. |

| Dominance & Evenness Indexes | Leads to distorted behavior of indexes due to sequence aggregation [10]. | Reflects more accurate biological distribution due to exact variants [10]. |

| Taxonomic Composition | Identification of major classes and genera can show significant discrepancies compared to ASV methods [14]. | Higher precision in identification at species level and beyond [11]. |

4.2 Performance in Detecting Novelty and Handling Contamination ASV-based methods provide a significant advantage in studies focusing on novel or poorly characterized environments. Since ASV generation does not rely on a reference database for the denoising step, it avoids the reference bias inherent in closed-reference OTU clustering, ensuring that novel taxa are not lost [11]. Furthermore, in the context of contamination, a study using a dilution series of a microbial community standard demonstrated that ASV-based methods were better able to differentiate sample biomass from contaminant biomass [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Tools

The implementation of OTU and ASV pipelines relies on a suite of well-established bioinformatic tools and reference materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabarcoding Analysis.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard [13] [11] | Mock Community | A defined mix of microbial genomes used as a positive control to benchmark the accuracy (specificity and sensitivity) of bioinformatics pipelines. |

| Silva / Greengenes / RDP [13] [14] [15] | Reference Database | Curated databases of 16S rRNA gene sequences used for taxonomic assignment of OTUs or ASVs, and for positive filtering in some pipelines. |

| DADA2 [13] [16] [14] | Software Package (R) | A widely used pipeline for inferring ASVs from amplicon data via a parametric error model. |

| MOTHUR [16] [14] [15] | Software Package | A comprehensive, all-in-one software suite for processing sequence data, with a strong legacy in OTU clustering. |

| USEARCH/VSEARCH [13] [17] | Software Tool | Tools used for a variety of sequence processing tasks, including dereplication, chimera filtering, and implementing the UNOISE3 denoising algorithm. |

| QIIME 2 [13] | Software Pipeline | A powerful, plugin-based platform that supports both OTU and ASV (via Deblur) analysis workflows. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Representative Comparison

The following protocol is synthesized from methodologies used in key comparative studies [13] [14].

6.1 Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from samples (e.g., soil, host-associated, or mock communities) using a standardized kit (e.g., PowerSoil Pro Kit).

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target marker gene (e.g., the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene) using dual-indexed barcoded primers.

- Sequencing: Pool and sequence the amplicons on an Illumina MiSeq platform (or equivalent) to generate paired-end reads (e.g., 2x250 bp or 2x300 bp).

6.2 Bioinformatic Processing: Parallel OTU and ASV Pipelines Process the raw FASTQ files from Step 1 through two parallel pipelines.

ASV Pipeline (DADA2):

- Filter and Trim: Trim forward and reverse reads to a fixed length to remove low-quality bases (e.g., 270F/210R). Filter reads based on quality scores and maximum expected errors.

- Learn Error Rates: Learn the specific error rates from the dataset.

- Dereplicate: Collapse identical reads.

- Infer ASVs: Apply the core DADA2 algorithm to correct errors and infer true biological sequences.

- Merge Reads: Merge paired-end reads and remove chimeric sequences.

- Generate Table: Construct an ASV abundance table and assign taxonomy using a reference database.

OTU Pipeline (MOTHUR):

- Assemble & Filter: Merge paired-end reads. Screen sequences for length and ambiguous bases.

- Align: Align sequences to a reference alignment (e.g., SILVA database).

- Pre-cluster: Pre-cluster sequences to reduce noise.

- Chimera Removal: Remove chimeras using a tool like VSEARCH.

- Cluster: Cluster sequences into OTUs using the average neighbor algorithm at 97% and 99% identity.

- Generate Table: Construct an OTU abundance table and assign taxonomy.

6.3 Downstream Statistical Comparison

- Alpha Diversity: Calculate richness (e.g., Chao1) and diversity (e.g., Shannon) indices from the OTU and ASV tables and compare.

- Beta Diversity: Calculate both taxonomic (e.g., Bray-Curtis) and phylogenetic (e.g., Weighted/Unweighted UniFrac) dissimilarity matrices. Compare the outcomes using ordination (e.g., PCoA) and statistical tests (e.g., PERMANOVA).

- Taxonomic Composition: Compare the relative abundances of major taxa (e.g., at the phylum, family, and genus levels) identified by each method.

- Accuracy Assessment (Mock Communities): For mock community data, compare the inferred sequences (OTUs/ASVs) against the known, expected sequences to calculate metrics like sensitivity and specificity.

The evolution from OTU clustering to ASV denoising marks a maturation of microbiome bioinformatics, driven by the core scientific principles of accuracy, resolution, and reproducibility. While OTU methods laid the foundation for the field and remain useful for specific contexts like comparing legacy datasets, evidence from rigorous methodological comparisons strongly supports the adoption of ASV-based approaches for most contemporary and future studies [10] [1] [11]. The higher resolution of ASVs enables a more precise investigation of microbial ecology, including strain-level dynamics that are critical for understanding microbial function in health, disease, and drug development. As the field progresses, the reproducibility of ASVs will further facilitate the creation of large, unified datasets and meta-analyses, accelerating our understanding of the microbial world.

The analysis of marker-gene sequencing data, a cornerstone of modern microbial ecology and genetic taxonoy, rests on the fundamental step of grouping sequencing reads into discrete units. For years, the scientific community relied primarily on Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) clustered by similarity thresholds [18]. Recently, however, a paradigm shift has occurred toward Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) inferred through statistical error models [19]. This transition represents more than a mere technical improvement; it constitutes a fundamental change in the philosophical approach to data analysis, with far-reaching implications for the reproducibility, resolution, and cross-study comparability of research findings. Within the broader thesis of understanding OTU and ASV methodologies, examining their underlying principles—similarity thresholds versus statistical error models—is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who depend on accurate biological interpretation of genetic data. This technical guide delves into the core mechanisms of both approaches, providing a detailed comparison of their methodologies, performance, and appropriate applications.

Core Principles: A Comparative Foundation

The fundamental difference between OTUs and ASVs lies in their approach to handling sequence variation. The following table summarizes the core principles that distinguish these two methodologies.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between OTU and ASV Approaches

| Feature | OTU (Similarity Threshold) | ASV (Statistical Error Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Principle | Clusters sequences based on a fixed identity percentage (e.g., 97%) [18] [20] | Distinguishes sequences using a statistical model to correct errors, identifying true biological variation [18] [20] |

| Similarity Threshold | Arbitrary, user-defined (typically 97-99%) [20] | Effectively 100%; even single-nucleotide differences are resolved [20] |

| Primary Goal | Reduce data complexity and impact of sequencing errors by clustering [18] | Recover the exact biological sequences present in the sample prior to errors [19] |

| Resolution | Species or genus level (clusters similar sequences) [18] | Single-nucleotide (sub-species or strain level) [20] |

| Nature of Output | Emergent property of a dataset; cluster composition is sample-dependent [19] | Consistent biological label; has intrinsic meaning independent of the dataset [19] |

The OTU Methodology: Similarity Thresholds in Practice

Technical Workflow and Clustering Strategies

The OTU approach is predicated on the concept that sequences originating from related organisms will be similar, and that rare sequencing errors will have a minimal impact on the consensus sequence of the resulting cluster [18]. The process typically involves clustering sequencing reads that demonstrate a sequence identity above a fixed threshold, most commonly 97%, which has been conventionally used as a proxy for species-level demarcation [21] [20].

There are three primary methods for generating OTUs, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- De novo Clustering: This method constructs OTU clusters entirely from observed sequences without a reference database. While it avoids reference bias and retains novel sequences, it is computationally expensive, and the resulting OTUs are emergent properties of the specific dataset. This means they cannot be directly compared between different studies [18] [19].

- Closed-Reference Clustering: This method compares discovered sequences to a pre-existing reference database. Reads are assigned to an OTU if they are sufficiently similar to a reference sequence. This method is computationally efficient and allows for easy comparison between studies using the same database. However, it discards sequences not represented in the reference database, leading to a loss of novel biological variation [18] [19].

- Open-Reference Clustering: This hybrid approach first clusters sequences against a reference database (like closed-reference) and then clusters the remaining, unassigned sequences de novo. It seeks to balance computational efficiency with the retention of novel diversity [18].

Limitations of the Similarity Threshold

The reliance on a fixed similarity threshold introduces several critical limitations. First, it fails to capture subtle biological sequence variations, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which can be biologically significant but are collapsed into a single OTU [20]. Second, the choice of a 97% threshold, while conventional, is subjective; different thresholds can lead to inconsistent results [20]. Furthermore, the clustering process itself can be influenced by the relative abundances of sequences in the sample, meaning that the delineation of OTUs is not just a practical concern but a data-dependent one, even with infinite sequencing depth [19].

The ASV Methodology: Statistical Error Models in Practice

Technical Workflow and Denoising Algorithms

In contrast to the clustering approach, the ASV methodology employs a denoising process to distinguish biological sequences from sequencing errors. This process uses a statistical model of the sequencing errors incurred during the high-throughput sequencing process [18] [20]. Algorithms like DADA2 implement a divisive amplicon denoising algorithm that uses a parameterized error model to determine if the differences between sequence reads are more likely to be due to technical errors or true biological variation [16] [20].

The process can be broken down into key steps:

- Error Model Learning: The algorithm first learns the specific error rates for each type of substitution (e.g., A→C, A→G, etc.) from the sequence data itself.

- Partitioning Sequences: It then partitions the sequence reads into partitions, or "cores," that are consistent with having been generated from a unique biological sequence plus the known error model.

- Chimera Removal: The identified sequences are further scrutinized to remove chimeras, which are artifactual sequences formed from two or more biological parent sequences during PCR amplification [18].

The output is a table of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which are exact sequences inferred to be truly present in the original sample.

The DADA2 Algorithm: A Closer Look

DADA2 is a prominent algorithm for ASV inference. Its key technical features include [20]:

- Statistical Learning of Variation Probabilities: It uses a Poisson distribution-based probability model to analyze each base position, accurately calculating the likelihood that an observed sequence variant is real versus the product of a sequencing error.

- Divisive Clustering Algorithm: Through an iterative algorithm, DADA2 separates noise from real sequences, enabling the isolation of true sequence variations without relying on manually set similarity thresholds.

This method overcomes the limitations of fixed thresholds by providing single-nucleotide resolution and generating ASVs that are consistent, reproducible labels that can be directly compared across studies [19].

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Biological Interpretation

Quantitative and Qualitative Comparisons

Numerous studies have quantitatively compared the performance of OTU and ASV methods, revealing significant differences in their outputs and the subsequent biological conclusions.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of OTU vs. ASV Methods from Empirical Studies

| Study Context | Key Findings | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 5S-IGS in Beech Species (Fagus spp.) [16] | Over 70% of processed reads were shared. DADA2-ASVs achieved a strong reduction (>80%) of representative sequences yet identified all main known variants. MOTHUR generated large proportions of rare variants that complicated phylogenies. | ASVs provided a more efficient and computationally simpler data set without losing phylogenetic signal. |

| 16S rRNA of Freshwater Communities [21] | The choice of pipeline (OTU vs. ASV) had stronger effects on alpha and beta diversity measures than other methodological choices (e.g., rarefaction). The discrepancy was most pronounced for presence/absence indices like richness. | The biological signal detected can be fundamentally influenced by the choice of analysis method. |

| Soil and Plant Microbiomes [22] | The ASV method outperformed the OTU method in estimating community richness and diversity, especially for fungal sequences and when sequencing depth was high. Differences in methods affected the number of differentially abundant families detected. | Can lead researchers to draw different biological conclusions; performance is related to community diversity and sequencing depth. |

| Mock Communities [18] [22] | ASV-based methods were better able to infer sample from contaminant biomass and provided more precise identification. In culture-based mocks, ASVs detected a richness much closer to the known number of strains than OTUs did. | ASVs offer higher sensitivity and specificity in controlled conditions, improving accuracy. |

Impact on Downstream Analysis

The choice between OTUs and ASVs significantly impacts downstream ecological and evolutionary analyses. ASVs have been shown to better discriminate ecological patterns [19]. In phylogenetic studies, ASVs effectively captured all main genetic variants with a much-reduced and more manageable set of sequences, leading to cleaner and more robust phylogenies, whereas OTU methods often produced redundant and complicated trees with many rare variants [16]. Furthermore, the consistent labeling of ASVs makes them ideal for meta-analysis and forward prediction, as biomarkers or features identified in one study can be directly applied and tested in new data sets, a process that is problematic with de novo OTUs [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: OTU Clustering with Mothur

The following protocol is adapted from studies comparing OTU and ASV methods on 16S rRNA gene amplicon datasets [21]:

- Sequence Pre-processing: Perform quality filtering on raw paired-end Illumina reads (e.g., using the

make.contigscommand in Mothur). Remove sequences with ambiguous bases or longer than a specified length. - Alignment: Align the quality-filtered sequences against a reference alignment database (e.g., SILVA database).

- Chimera Removal: Identify and remove chimeric sequences using algorithms like UCHIME.

- Clustering: Cluster the pre-processed sequences into OTUs using the

clustercommand with a predefined identity threshold (e.g., 97% or 99%). - Taxonomic Classification: Classify the representative sequence of each OTU against a reference taxonomy database.

- Generate Feature Table: Construct a sample-by-OTU feature table that records the abundance of each OTU in every sample for downstream diversity analysis.

Detailed Protocol: ASV Inference with DADA2

The following protocol is adapted from studies using DADA2 for 16S rRNA analysis [21] and 5S-IGS analysis [16]:

- Filter and Trim: Quality filter and trim raw forward and reverse reads based on quality profiles (

filterAndTrim). Typically, truncate reads at the position where quality drops significantly. - Learn Error Rates: Learn the specific error rates from the sequence data itself (

learnErrors). This creates the error model that will be used for denoising. - Dereplication: Dereplicate the sequences to combine identical reads (

derepFastq), which reduces computation time. - Infer ASVs: Apply the core sample inference algorithm to the dereplicated data (

dada). This uses the learned error model to distinguish true biological sequences from errors. - Merge Paired Reads: Merge the denoised forward and reverse reads (

mergePairs) to create the full-length denoised sequences. - Construct Sequence Table: Construct an amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table, which is a higher-resolution analogue of the OTU table (

makeSequenceTable). - Remove Chimeras: Remove chimeric sequences identified by comparing each sequence to more abundant "parent" sequences (

removeBimeraDenovo).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core logical and procedural differences between the OTU clustering and ASV denoising workflows, highlighting the divergent paths from raw sequences to the final feature table.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, software, and reference databases essential for conducting OTU and ASV analyses, as cited in the reviewed literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for OTU/ASV Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| MOTHUR | A comprehensive, expandable software pipeline for OTU clustering and analysis of microbiome data. | Used in comparative studies for OTU-based analysis of 16S rRNA and 5S-IGS data [16] [21]. |

| DADA2 | An R package that infers amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using a statistical error model. | Used in comparative studies as a leading ASV-based method for 16S rRNA and 5S-IGS data [16] [21] [20]. |

| SILVA Database | A comprehensive, curated database of aligned ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences. | Used as a reference for sequence alignment and taxonomic classification in both OTU and ASV workflows [22]. |

| USEARCH/UPARSE | A algorithm and tool for OTU clustering, known for effectively removing sequencing errors and chimeras. | A representative OTU-clustering algorithm cited in methodological comparisons [20] [22]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | A defined mock community of microbial cells with known composition. | Used as a positive control and benchmark to validate the performance and sensitivity of OTU and ASV methods [18] [22]. |

| Illumina MiSeq Platform | A high-throughput sequencing platform for generating paired-end amplicon sequences. | The source of sequence data in multiple comparative studies cited [21]. |

The comparison between similarity thresholds and statistical error models reveals a clear evolutionary path in bioinformatics. The traditional OTU approach, with its pragmatic use of fixed thresholds, reduces complexity but at the cost of resolution, reproducibility, and cross-study comparability [19]. The ASV approach, grounded in statistical inference, provides finer resolution, generates biologically meaningful and consistent labels, and mitigates the arbitrary nature of clustering thresholds [16] [20].

While the field is moving toward wider adoption of ASVs, the choice of method should be informed by the specific research question. For well-studied environments with comprehensive reference databases, OTU methods may still be computationally practical for large-scale, population-level studies [18]. However, for exploring novel environments, requiring high-resolution analysis, or aiming for reproducible, cumulative science, ASVs offer significant advantages [19] [22]. Future developments will likely involve deeper applications of machine learning in bioinformatics and the creation of standardized analytical frameworks that can seamlessly integrate data from diverse sequencing platforms, further solidifying the principles of statistical error modeling as the standard for marker-gene data analysis [20].

In the analysis of microbial communities through 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, the bioinformatic processing of raw sequence data is a critical step that defines the resolution and biological validity of the results. This field has evolved through two primary methodological paradigms: Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). OTU-based methods, including MOTHUR and UPARSE, cluster sequencing reads at a fixed identity threshold, traditionally 97%, to approximate species-level groupings [23]. This approach reduces noise but inherently limits phylogenetic resolution by grouping similar sequences together. In contrast, ASV-based methods such as DADA2 and Deblur attempt to reconstruct exact biological sequences present in the original sample through error-correction algorithms, providing single-nucleotide resolution without clustering [24]. ASVs offer several advantages: they resolve closely related taxa, provide reproducible results across studies without arbitrary clustering thresholds, and enable direct comparison of sequences across different projects [23] [24]. The choice between these approaches significantly impacts downstream biological interpretations, with ASV methods generally providing higher specificity and sensitivity while OTU methods offer computational efficiency and established workflows.

Pipeline-Specific Methodologies and Workflows

UPARSE-OTU Algorithm and Pipeline

The UPARSE pipeline operates on an OTU-clustering approach implemented through the cluster_otus command. The algorithm employs a greedy clustering method that processes input sequences in order of decreasing abundance, based on the biological rationale that high-abundance reads are more likely to represent true amplicon sequences rather than PCR or sequencing errors [25]. Each input sequence is compared to the current OTU database using a maximum parsimony model (UPARSE-REF), with three possible outcomes: (1) if the model is ≥97% identical to an existing OTU, the sequence joins that OTU; (2) if the model is chimeric, the sequence is discarded; (3) if the model is <97% identical to any OTU, the sequence forms a new OTU [25].

The complete UPARSE pipeline involves several critical pre-processing steps: quality filtering using expected error methods, global trimming to fixed length for alignability, barcode removal before dereplication, dereplication with size annotation, and abundance-based sorting that typically discards singletons [26]. Post-clustering, recommended steps include reference-based chimera filtering using databases like Gold for 16S genes, OTU relabeling with systematic identifiers, and OTU table construction by mapping reads back to OTU representatives [26].

DADA2 Algorithm and Workflow

DADA2 implements a novel ASV inference approach based on a parametric error model that learns specific error rates from the dataset itself, rather than using a fixed clustering threshold [27]. The algorithm models the abundance p-value of each sequence, comparing the actual abundance of a specific sequence to its expected abundance given the error model and the abundances of its parent sequences [23]. This approach allows DADA2 to distinguish between true biological sequences and erroneous reads with single-nucleotide precision.

The DADA2 workflow begins with read quality profiling and visualization to inform trimming parameters. The core processing includes filtering and trimming with parameters like truncLen determined by quality score deterioration, maxN=0 (no Ns allowed), truncQ=2, and maxEE=2 (maximum expected errors) [27]. Unlike UPARSE, DADA2 performs denoising separately on forward and reverse reads before merging them, with the algorithm incorporating quality information to make it robust to lower quality sequences [27] [23]. The workflow concludes with chimera removal, sequence table construction, and taxonomy assignment.

Deblur Algorithm and Workflow

Deblur employs a greedy deconvolution algorithm that uses known Illumina error profiles to rapidly resolve single-nucleotide differences while removing sequencing errors [28] [24]. The algorithm operates on each sample independently, first sorting sequences by abundance, then iterating from most to least abundant sequence, subtracting predicted error-derived reads from neighboring sequences based on Hamming distance and an upper-bound error probability [24]. Deblur incorporates a parameterized maximal probability for indels (defaulting to 0.01) and a mean read error rate for normalization (defaulting to 0.5%) [24].

A critical requirement for Deblur is that all input sequences must be trimmed to the same length, as the algorithm cannot associate sequences with different lengths [28]. The workflow includes positive and negative filtering: negative mode removes known artifacts (e.g., PhiX, adapter sequences with ≥95% identity), while positive mode retains sequences similar to a reference database (e.g., 16S sequences with e-value ≤ 10) [28]. Deblur applies minimal reads filtering across all samples (default 10 reads) to remove rare sequences that may represent residual errors [28].

MOTHUR Workflow and Approach

MOTHUR provides a comprehensive, integrated pipeline for OTU-based analysis with an emphasis on community standards and reproducibility [23] [29]. While the search results provide less algorithmic detail compared to other pipelines, MOTHUR implements a 97% identity clustering approach similar to UPARSE but within an all-in-one toolkit environment [23]. The platform includes internal read merging and quality filtering ("screening") that is not easily performed outside the MOTHUR ecosystem [23].

MOTHUR's workflow can be executed through either a graphical interface with pipeline building and run controls or via command-line batch processing [29]. The pipeline encompasses all stages from raw read processing through OTU picking, sequence alignment, taxonomy assignment, and diversity analysis within a single framework, reducing the need for external tool integration [29].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

A comprehensive 2020 benchmarking study compared six bioinformatic pipelines using both mock communities and large clinical datasets (N=2170) [23]. The results provide critical insights into the relative performance of these methods under realistic conditions.

Table 1: Pipeline Performance Comparison on Mock Community Data

| Pipeline | Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Resolution | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | ASV | Highest | Moderate | Single-nucleotide | Best sensitivity, at expense of decreased specificity |

| USEARCH-UNOISE3 | ASV | High | Highest | Single-nucleotide | Best balance between resolution and specificity |

| Qiime2-Deblur | ASV | High | High | Single-nucleotide | Good performance with rapid processing |

| USEARCH-UPARSE | OTU | Moderate | Moderate | 97% identity | Good performance with lower specificity than ASV methods |

| MOTHUR | OTU | Moderate | Moderate | 97% identity | Solid performance with integrated workflow |

| QIIME-uclust | OTU | Low | Low | 97% identity | Produced spurious OTUs; not recommended |

Table 2: Computational Performance and Technical Characteristics

| Pipeline | Computational Demand | Processing Speed | Memory Usage | Stability Across Runs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | High | Slowest | Growing with data size | Moderate |

| Deblur | Moderate | Faster than DADA2 | Fairly flat profile | High |

| USEARCH-UNOISE3 | Low | Fastest (order faster than Deblur) | Growing with data size | N/A |

| UPARSE | Low to Moderate | Fast | Efficient | High |

| MOTHUR | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High |

Key Differentiating Factors in Pipeline Performance

The benchmarking revealed several critical factors that differentiate pipeline performance:

Error Model Sophistication: DADA2's parametric error model provides the highest sensitivity but may decrease specificity by retaining some erroneous sequences [23]. In contrast, Deblur's use of static Illumina error profiles offers a good balance of sensitivity and computational efficiency [24].

Cross-Run Stability: When analyzing technical replicates across separate sequencing runs, Deblur demonstrated greater stability than DADA2, with a larger fraction of sOTUs from the first run being identified in the second run, particularly at higher frequency cutoffs [24].

Artifact Detection: In comparisons using natural communities, sequences unique to Deblur showed fewer BLAST mismatches to reference databases compared to sequences unique to DADA2, suggesting Deblur may produce more biologically plausible variants for rare sequences [24].

Quantitative Accuracy: All ASV methods (DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3) showed improved quantitative agreement with expected abundances in mock communities compared to OTU methods, with UNOISE3 showing the best balance between resolution and specificity [23].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Sample Preparation and Sequencing Considerations

Proper experimental design and sample preparation are prerequisites for successful analysis regardless of the chosen bioinformatic pipeline. The benchmarking studies revealed several critical considerations:

Library Preparation: For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the V4 region is commonly amplified using 515F and 806R primers with dual indexing [23]. PCR conditions typically involve: initial denaturation at 94°C for 47 minutes, 25 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 45 sec), annealing (52°C for 60 sec), and elongation (72°C for 90 sec), with a final elongation at 72°C for 10 minutes [23].

Sequencing Parameters: Illumina MiSeq instruments with 2×250 bp paired-end reads provide sufficient overlap for the V4 region. The inclusion of 15% PhiX control DNA helps with quality monitoring and cluster generation [23].

Quality Metrics: Successful sequencing runs should achieve >70% of bases with quality scores higher than Q30, with expected error (EE) values preferably under 2 for quality-filtered reads [30].

Critical Parameter Selection for Each Pipeline

UPARSE Parameters:

- Quality filtering: Maximum expected error filtering with

fastq_maxee 1[23] - Read merging:

maxdiffs 30in overlapping region for V4 sequences [23] - Global trimming to fixed length before dereplication [26]

- Abundance sorting with

-minsize 2to discard singletons [26]

DADA2 Parameters:

- Truncation length: Position 240 for forward reads, 160 for reverse reads (for 2×250 V4 data) [27]

- Filtering:

maxN=0,maxEE=c(2,2),truncQ=2,rm.phix=TRUE[27] - Error learning: Default parameters typically sufficient for standard datasets [27]

Deblur Parameters:

- Trim length: Fixed length required (

-t 150for 150nt sequences) [28] - Minimal reads:

--min-reads 10(default) for cross-sample abundance filtering [28] - Thread usage:

-O NNNfor parallel processing [28]

Table 3: Key Experimental Resources for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

| Resource | Function/Application | Specifications | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Mock Community B | Pipeline validation and error rate assessment | 20 bacterial strains with 22 sequence variants in V4 region | BEI Resources (HM-782D) [23] |

| Gold Database | Reference-based chimera checking for 16S data | Curated 16S database (not comprehensive) | USEARCH recommendations [26] |

| PhiX Control Library | Sequencing process control and error monitoring | Illumina sequencing control | Illumina [23] |

| 515F/806R Primers | V4 region 16S rRNA gene amplification | Dual-indexing compatible primers | [23] |

| SortMeRNA | Positive filtering for 16S sequences in Deblur | Version-restricted for compatibility | Deblur dependencies [28] |

| UNITE Database | Reference database for ITS region analysis | Fungal ITS sequences | USEARCH recommendations [26] |

The choice between OTU and ASV pipelines involves important trade-offs between resolution, specificity, computational demands, and analytical needs. For most contemporary applications, ASV-based methods provide superior resolution and reproducibility compared to traditional OTU clustering. Based on the comparative benchmarking:

- USEARCH-UNOISE3 provides the best balance between resolution and specificity when computational resources allow [23].

- DADA2 offers the highest sensitivity for detecting rare variants but requires greater computational resources and may benefit from additional filtering [23].

- Deblur represents an excellent compromise between performance and efficiency, with particularly strong stability across sequencing runs [24].

- UPARSE remains a robust OTU-based option when ASV-level resolution is not required, providing reliable performance with moderate computational demands [23].

- MOTHUR offers a comprehensive integrated solution for researchers preferring an all-in-one toolkit with established community standards [23].

For clinical and regulatory applications where specificity is paramount, USEARCH-UNOISE3 or Deblur may be preferred. For exploratory research where maximum sensitivity to detect rare variants is critical, DADA2 provides advantages. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward longer read lengths, ASV methods will likely become increasingly dominant due to their ability to leverage higher resolution data without arbitrary clustering thresholds.

In the analysis of targeted marker-gene sequencing data, the field of microbial ecology has undergone a significant methodological shift. The traditional approach of clustering sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) is increasingly being supplanted by methods that resolve exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). This transition represents more than merely technical refinement; it fundamentally alters how researchers measure, compare, and interpret microbial diversity. The core distinctions between these approaches revolve around two interconnected concepts: the property of consistent labeling and the degree of dependence on reference databases. These properties have profound implications for computational tractability, meta-analysis, replication of scientific findings, and the accuracy of diversity measurements [31] [32]. This technical guide examines these critical distinctions within the broader context of OTU and ASV research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on their specific research objectives and sample types.

Fundamental Conceptual Differences Between OTUs and ASVs

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): Cluster-Based Approaches

OTUs are defined through a clustering process where sequencing reads are grouped based on sequence similarity above a predetermined threshold, most commonly 97% [32] [21]. These clusters represent abstract biological units whose boundaries and membership are emergent properties of a specific dataset.

- De Novo OTUs: Constructed by clustering sequencing reads based on pairwise similarity within a dataset without reference to existing databases. This method is computationally expensive and produces OTUs that are intrinsically tied to the dataset in which they were defined, lacking consistent labels for cross-study comparison [31] [32].

- Closed-Reference OTUs: Defined by comparing sequencing reads to a pre-existing reference database, with reads assigned to OTUs based on similarity to reference sequences. This method offers computational efficiency and consistent labeling but systematically discards biological variation not represented in the reference database [31].

- Open-Reference OTUs: A hybrid approach that first uses closed-reference methods followed by de novo clustering of reads that fail to match reference sequences, attempting to balance the advantages of both methods [32].

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs): Denoising-Based Approaches

ASVs represent an alternative paradigm that resolves biological sequences exactly, down to single-nucleotide differences, without imposing arbitrary dissimilarity thresholds. ASV methods use error models to distinguish biological sequences from sequencing errors, inferring the true biological sequences present in the sample prior to amplification and sequencing artifacts [31] [32]. Unlike OTUs, ASVs are not emergent properties of a dataset but represent biological realities with intrinsic meaning—the exact DNA sequences of the assayed organisms. This fundamental difference grants ASVs the property of consistent labeling, enabling valid comparison across different studies and samples [31].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of OTUs and ASVs

| Characteristic | De Novo OTUs | Closed-Reference OTUs | ASVs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition Basis | Emergent from dataset clustering | Similarity to reference sequence | Inferred biological sequence |

| Resolution | 97% similarity threshold | 97% similarity threshold | Single-nucleotide |

| Reference Dependence | None (reference-free) | Complete | None (reference-free) |

| Consistent Labeling | No | Yes | Yes |

| Computational Scaling | Quadratic with study size | Linear with study size | Linear with study size |

| Novel Diversity Capture | Complete | None | Complete |

Consistent Labeling: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Consequences

Conceptual Framework of Consistent Labeling

Consistent labeling refers to the property of a feature that can be reproducibly identified across different studies, datasets, and processing events. This property exists when the feature represents a biological reality independent of the data being analyzed [31]. The schematic below illustrates the region of validity for each feature type, where the x-axis represents all biological variation at the sequenced genetic locus and the y-axis represents all current and future amplicon data.

Practical Implications of Consistent Labeling

The property of consistent labeling confers several critical advantages for microbial data analysis:

Computational Tractability: Methods with consistent labels (closed-reference OTUs and ASVs) enable parallel processing of data subsets that can be merged afterward. In contrast, de novo OTU methods require pooling all data before clustering, resulting in a quadratic scaling of computational costs that becomes prohibitive for large studies [31]. ASV inference can be performed independently on each sample, allowing total computation time to scale linearly with sample number.

Meta-Analysis Capability: The growing availability of marker-gene studies creates opportunities for powerful cross-study analyses. Consistently labeled features allow per-study tables to be directly merged into cross-study tables, while de novo OTUs require reprocessing raw sequence data from all studies together—a computationally intensive and often impractical endeavor [31].

Replication and Falsification: Scientific reproducibility requires that findings can be tested in new datasets. Associations reported between a de novo OTU and experimental conditions cannot be directly tested in new data because that specific OTU only exists within its original dataset. In contrast, associations involving ASVs or closed-reference OTUs can be directly examined in independent studies [31].

Forward Prediction: When microbial community features are used as predictive biomarkers (e.g., for health conditions), only consistently labeled features can be applied to new data. Predictive models based on de novo OTUs are confined to the dataset in which they were trained, while ASV-based predictors can be deployed on future samples [31].

Reference Database Dependence: Implications for Diversity Assessment

Methodological Dependence on Reference Databases

The degree of dependence on reference databases represents another critical distinction between approaches, with significant consequences for diversity measurement and application across environments.

Closed-Reference OTUs: Complete dependence on reference databases means that biological variation unrepresented in the database is systematically excluded from analysis. This introduces database-specific biases that can skew diversity measures, particularly if some experimental conditions are associated with higher proportions of unrepresented taxa [31].

De Novo OTUs and ASVs: Both approaches are reference-free during feature definition, capturing all biological variation present in the data regardless of its representation in existing databases. This makes them particularly valuable for studying novel or undersampled environments [31] [32].

Impact on Diversity Measurements

The choice between reference-dependent and reference-free methods significantly influences alpha and beta diversity measures. A 2022 study comparing DADA2 (ASV-based) and Mothur (OTU-based) pipelines found that the choice of method had stronger effects on diversity measures than other methodological choices like rarefaction or OTU identity threshold (97% vs. 99%) [21]. The discrepancy was particularly pronounced for presence/absence indices such as richness and unweighted UniFrac, though rarefaction could partially attenuate these differences [21].

Table 2: Impact of Method Choice on Diversity Measurements Across Environments

| Environment Type | Recommended Method | Rationale | Diversity Measurement Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Studied (e.g., Human Gut) | Closed-Reference OTUs or ASVs | High reference database coverage (>90%) | Minimal bias with closed-reference; ASVs provide higher resolution |

| Moderately Studied | ASVs or Open-Reference OTUs | Partial database coverage | ASVs capture novel diversity more completely |

| Novel Environments | ASVs or De Novo OTUs | Limited database coverage | Reference-dependent methods systematically underestimate diversity |

| Cross-Study Comparisons | ASVs | Consistent labeling without reference bias | Enables valid comparison while capturing full diversity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Method Comparison

To evaluate the practical implications of these theoretical distinctions, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol for comparing OTU and ASV approaches:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Collect samples from relevant environments (e.g., 54 sediment, 54 seston, and 119 host-associated samples as in Chiarello et al., 2022) [21].

- Extract genomic DNA using standardized kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit for environmental samples).

- Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometric methods and normalize concentrations.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Amplify the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 515F/806R.

- Perform PCR amplification with the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes; 30 cycles of 94°C for 45s, 50°C for 60s, 72°C for 90s; final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes.

- Purify amplicons using bead-based cleanups and quantify with fluorometry.

- Pool equimolar amounts of amplicons and sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform with 2×250 bp chemistry.

Bioinformatic Processing - OTU Approach

- Process raw sequences using Mothur pipeline following standard operating procedure.

- For de novo OTUs: Cluster sequences at 97% and 99% identity thresholds using the average neighbor algorithm.

- For closed-reference OTUs: Map sequences to SILVA or Greengenes database at 97% identity.

- Chimera removal using UCHIME and taxonomic assignment with the RDP classifier.

Bioinformatic Processing - ASV Approach

- Process raw sequences using DADA2 pipeline in R environment.

- Perform quality filtering, error rate learning, sample inference, and chimera removal.

- Merge paired-end reads and assign taxonomy using the same reference database as OTU methods for comparative purposes.

Downstream Diversity Analysis

- Rarefy all community tables to even sequencing depth.

- Calculate alpha diversity metrics (richness, Shannon diversity, Faith's PD).

- Calculate beta diversity metrics (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, weighted and unweighted UniFrac).

- Perform statistical comparisons (PERMANOVA, ANOVA) to evaluate methodological effects.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for OTU/ASV Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | DNA extraction from environmental samples | Effective for difficult-to-lyse microorganisms; minimizes inhibitor co-extraction |

| Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 | 2×300 bp paired-end sequencing | Optimal for V4 region of 16S rRNA gene; provides sufficient overlap for merging |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers (515F/806R) | Amplification of V4 hypervariable region | Broad taxonomic coverage; well-established for human and environmental microbiomes |

| SILVA Database | Reference database for taxonomy assignment | Comprehensive curation; regularly updated; includes quality-controlled alignments |

| Greengenes Database | Alternative reference database | Well-established but no longer actively curated; useful for historical comparisons |

| Mothur Pipeline | OTU-based sequence processing | Implements multiple clustering algorithms; includes comprehensive quality control |

| DADA2 R Package | ASV-based sequence processing | Uses parametric error models; resolves exact sequence variants; integrates with Phyloseq |

| QIIME 2 Platform | Integrated microbiome analysis | Supports both OTU and ASV workflows; extensive plugin ecosystem for specialized analyses |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Performance

Performance Across Sample Types and Environments

The relative performance of OTU versus ASV approaches varies depending on the characteristics of the microbial community under investigation and the specific research questions being addressed.

Well-Characterized Environments In environments with comprehensive reference database coverage, such as the human gut, closed-reference OTU methods can capture >90% of sequencing reads while offering computational efficiency [31] [32]. However, even in these contexts, ASV methods provide superior resolution for distinguishing closely related taxa—for example, discriminating pathogenic Neisseria gonorrhoeae from commensal Neisseria species [31].

Novel or Undersampled Environments For environments with limited representation in reference databases, such as unusual aquatic systems or extreme environments, ASV and de novo OTU approaches significantly outperform closed-reference methods. ASVs offer particular advantages in these contexts by combining reference-free operation with consistent labeling, enabling cross-study comparisons without sacrificing novel diversity [32].

Low-Biomass and Contaminated Samples Studies using dilution series of microbial community standards have demonstrated that ASV-based methods more accurately distinguish true signal from contamination. The precise nature of ASVs facilitates identification of both sample and contaminant sequences, making them particularly valuable for challenging samples with low microbial biomass [32].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodological Outputs

Table 4: Quantitative Comparison of OTU and ASV Method Performance

| Performance Metric | De Novo OTUs | Closed-Reference OTUs | ASVs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness Estimation | Often overestimates [21] | Underestimates (misses novel diversity) | Most accurate with mock communities [32] |

| Sensitivity to Rare Taxa | High (but includes spurious OTUs) [32] | Low (rare novel taxa lost) | High (DADA2 most sensitive) [32] |

| Specificity | Moderate (includes some errors as diversity) | High for known taxa | High (statistical error removal) [32] |

| Cross-Study Comparability | None (must reprocess jointly) | High (with same reference) | High (intrinsically comparable) |

| Computational Time | High (scales quadratically) | Low (scales linearly) | Moderate (scales linearly) |

| Chimera Detection | Reference-based; less sensitive | Reference-based; less sensitive | Superior (exact sequence alignment) [32] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species level (97% threshold) | Species level (97% threshold) | Sub-species level (single nucleotide) |

Implications for Drug Development and Translational Research

The distinction between OTUs and ASVs carries particular significance for drug development professionals utilizing microbiome data in translational research contexts.

Biomarker Discovery and Validation The consistent labeling of ASVs enables development of predictive biomarkers that can be validated across independent cohorts and clinical sites. In contrast, biomarkers based on de novo OTUs are confined to the discovery dataset, requiring indirect validation through taxonomic assignment or diversity summaries [31].

Clinical Trial Design Longitudinal studies and multi-center trials benefit tremendously from ASV-based approaches, as data from different time points and locations can be validly combined without reprocessing. This maintains statistical power while reducing computational burdens in large-scale clinical investigations.

Therapeutic Monitoring When evaluating microbiome responses to therapeutic interventions, ASVs provide the resolution necessary to detect subtle shifts in microbial populations that might reflect mechanistic responses or off-target effects. The higher resolution of ASVs is particularly valuable for tracking specific bacterial strains throughout treatment courses.

The workflow below illustrates how ASVs enhance translational research applications through consistent labeling and reduced reference bias:

The critical distinction between OTUs and ASVs rests fundamentally on their respective positions regarding consistent labeling and reference database dependence. ASVs uniquely combine the advantages of both closed-reference OTUs (consistent labeling, computational efficiency, cross-study comparability) and de novo OTUs (reference-free operation, comprehensive diversity capture, applicability to novel environments). While OTU-based approaches remain valid for specific research contexts—particularly well-characterized environments where reference database coverage is comprehensive—the accumulating evidence suggests that ASV methods offer significant advantages for most contemporary research applications. The property of consistent labeling particularly enhances reproducibility, meta-analysis capability, and translational potential, positioning ASVs as the emerging standard for marker-gene analysis in both basic research and drug development contexts. As the field continues to evolve, methodological choices should be guided by both theoretical principles and empirical performance characteristics relative to specific research objectives and sample characteristics.

Choosing Your Method: A Practical Guide for Research Design

In the analysis of high-throughput marker-gene sequencing data, researchers face a fundamental methodological choice: whether to cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or to resolve exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). This decision significantly impacts all downstream analyses, from diversity assessments to biomarker discovery. OTUs represent a traditional approach where sequences are clustered based on a fixed similarity threshold, typically 97%, which reduces computational burden and mitigates sequencing errors by grouping similar sequences [20] [21]. In contrast, ASVs are generated through denoising algorithms that distinguish biological sequences from sequencing errors at single-nucleotide resolution, providing exact sequence variants without relying on arbitrary clustering thresholds [19] [20]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for selecting between these approaches based on your project's specific research objectives, analytical requirements, and technical constraints.

Technical Foundations: How OTUs and ASVs Are Generated

OTU Clustering Methodologies

The OTU clustering workflow employs similarity-based algorithms to group sequences. The process begins with quality filtering of raw sequencing reads, followed by dereplication and clustering using algorithms such as UPARSE, MOTHUR, or VSEARCH that group sequences based on percent identity [33] [20]. Most commonly, a 97% similarity threshold is applied, meaning sequences with 97% or greater identity are collapsed into a single OTU. This approach assumes that sequencing errors will be merged with correct biological sequences during clustering, thereby reducing the impact of technical artifacts [21]. The representative sequence for each OTU is typically the most abundant sequence in its cluster. While effective for noise reduction, this method inevitably merges biologically distinct sequences that fall within the similarity threshold, potentially obscuring true genetic variation [20].

ASV Denoising Algorithms

ASV generation employs fundamentally different denoising algorithms such as DADA2, Deblur, and UNOISE3 that use statistical models to correct sequencing errors [33]. These methods do not cluster sequences; instead, they infer the true biological sequences in the original sample by modeling and removing errors introduced during amplification and sequencing. The DADA2 algorithm, for instance, implements a divisive amplicon denoising approach that uses a parameterized model of substitution errors to distinguish true biological sequences from errors [20]. This process retains single-nucleotide differences that are statistically supported as biological variation, providing higher resolution than OTU clustering. ASV methods produce consistent labels with intrinsic biological meaning that can be directly compared across studies without reference databases [19].

Visual Comparison of Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the key differences in the bioinformatic workflows for generating OTUs and ASVs:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarking

Methodological Comparison Using Mock Communities

Benchmarking studies using complex mock communities comprising 227 bacterial strains across 197 species provide objective performance measures [33] [34]. These controlled samples with known composition enable precise evaluation of error rates, detection sensitivity, and taxonomic accuracy across bioinformatic methods.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from Mock Community Benchmarking

| Performance Metric | OTU Methods (UPARSE) | ASV Methods (DADA2) | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error Rate | Lower error rates | Higher error rates | OTUs more effective at suppressing technical noise |

| Over-splitting | Less over-splitting | Moderate over-splitting | ASVs may split single strains into multiple variants |

| Over-merging | More over-merging | Less over-merging | OTUs may merge biologically distinct sequences |

| Community Similarity | Closest to intended structure | Close to intended structure | Both capture overall community patterns effectively |

| Alpha Diversity | Higher richness estimates | Lower, more accurate estimates | ASVs provide more realistic diversity measures |

| Computational Efficiency | Faster processing | More computationally intensive | OTUs preferable for very large datasets |

Impact on Ecological Interpretation

The choice between OTUs and ASVs significantly influences ecological interpretation, with effects exceeding those of other common methodological decisions like rarefaction level or OTU identity threshold (97% vs. 99%) [21]. Studies comparing freshwater invertebrate gut and environmental communities found the pipeline choice (DADA2 vs. MOTHUR) significantly affected alpha and beta diversity measures, particularly for presence/absence indices like richness and unweighted UniFrac [21]. These discrepancies can be partially mitigated by rarefaction, but the fundamental differences in resolution remain. For comparative analyses, ASVs provide more consistent labeling across studies, enabling direct meta-analyses without reprocessing raw data [19].

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate Method

Research Scenario Guidance

Table 2: Method Selection Based on Research Objectives

| Research Type | Recommended Method | Key Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Short Fragments (e.g., V3-V4) | ASV | Superior for high-resolution analysis of short regions; excels at detecting rare variants and single-nucleotide differences |

| Full-Length Amplicons (Third-generation sequencing) | OTU | More practical for long fragments; recommended similarity threshold of 98.5%-99% for species-level clustering |

| Microbial Source Tracking | ASV | Consistent labels allow direct comparison across independent studies; enables forward prediction for biomarkers |

| Community Ecology Studies | OTU or ASV | Both capture major patterns; ASV preferable for fine-scale dynamics, OTU for broad community comparisons |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | ASV | More effective reduction of representative sequences while capturing known variant types; computationally efficient for large sample sets |

| Functional Prediction | ASV | Higher resolution improves correlation with metagenomic data; more accurate identification of functional biomarkers |

| Large-Scale Biomonitoring | OTU | Lower computational requirements advantageous when processing thousands of samples with limited resources |

Technical and Experimental Considerations

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina platforms generating high-quality short reads are ideal for ASV analysis. For long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore), OTU clustering is often more practical, though PacBio HiFi reads can now be processed with DADA2 [35].

- Amplicon Characteristics: Short fragment primers (e.g., V4) benefit from ASV's precise error correction. For full-length 16S rRNA sequencing, OTU clustering with adjusted thresholds (98.5%-99%) is more appropriate [20].

- Computational Resources: ASV methods require greater computational power, especially for large sample sizes. DADA2's statistical modeling and error correction have significant hardware demands that may constrain researchers with limited infrastructure [20].

- Taxonomic Resolution Needs: For species-level or strain-level discrimination, ASVs provide superior resolution. For broader taxonomic comparisons at genus or family level, both methods perform similarly [35].

- Data Reusability Requirements: If consistent labeling across studies is essential for meta-analysis or biomarker development, ASVs provide inherent advantages through their status as biologically meaningful units [19].

Decision Flowchart