Optimizing First-Principles Calculations: A Guide to Precision and Efficiency in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing parameters for first-principles calculations, a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and drug development.

Optimizing First-Principles Calculations: A Guide to Precision and Efficiency in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on optimizing parameters for first-principles calculations, a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and drug development. We cover foundational principles, from core quantum mechanics to the 'seven Ds' problem-solving framework. The guide explores advanced methodological applications, including high-throughput screening and machine learning acceleration, which can speed up calculations by orders of magnitude. It details rigorous protocols for troubleshooting and optimizing critical parameters like k-point sampling and smearing. Finally, we establish best practices for code verification and result validation, ensuring reliability for high-stakes applications like battery material and novel energetic compound discovery. This end-to-end resource is designed to bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization.

Understanding First-Principles: The Bedrock of Computational Prediction

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Energy Cutoff (ENCUT) Convergence Issues

Problem: Total energy and derived properties (like bulk modulus) do not converge, or convergence is unstable across different systems.

Explanation: The plane-wave energy cutoff (ENCUT) determines the basis set size. Too low a value leads to inaccurate energies and forces; too high a value wastes computational resources. The optimal value is system-dependent and must be determined through a convergence test [1].

Solution:

- Perform a Convergence Test:

- Select a representative structure (e.g., the equilibrium geometry).

- Run a series of single-point energy calculations, increasing the

ENCUTvalue in each step (e.g., 200 eV, 250 eV, 300 eV, ..., 600 eV). - For each calculation, record the total energy.

- Analyze the Data:

- Plot the total energy versus

ENCUT. - Identify the

ENCUTvalue where the energy change between steps falls below your target precision (e.g., 1 meV/atom). This is your converged value [1].

- Plot the total energy versus

- Apply the Result: Use this converged

ENCUTvalue for all subsequent calculations involving the same pseudopotentials.

Advanced Consideration: For a more robust approach, converge a derived property like the bulk modulus or equilibrium lattice constant, as this is often more sensitive to the basis set than the total energy itself [1].

Guide 2: Optimizing K-point Sampling

Problem: Properties like electronic band gaps or density of states show unphysical oscillations or inaccuracies.

Explanation: K-points sample the Brillouin Zone. Insufficient sampling fails to capture electronic states accurately, while excessive sampling is computationally expensive. The required k-point mesh density depends on the system's cell size and symmetry.

Solution:

- Perform a Convergence Test:

- Keep all other parameters (especially

ENCUT) fixed at a converged value. - Run a series of calculations with increasingly dense k-point meshes (e.g., 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 6x6x6, ...).

- Record the total energy or the property of interest (e.g., band gap) for each mesh.

- Keep all other parameters (especially

- Analyze the Data:

- Plot the property against the number of k-points (or the k-point spacing).

- The converged value is where the property stabilizes within your target error margin [1].

- Use Symmetry: Employ the

Monkhorst-Packscheme to generate efficient k-point meshes. Always check that the mesh is centered on the Gamma point (if required) for non-metallic systems.

Guide 3: Managing Computational Cost in High-Throughput Studies

Problem: High-throughput workflows for hundreds of materials become computationally prohibitive.

Explanation: Using uniformly high, "safe" convergence parameters for all materials wastes resources, as some elements converge easily while others require more stringent parameters [1].

Solution:

- Implement Element-Specific Parameters: Do not use a single set of convergence parameters for all materials. Establish and use a database of converged

ENCUTand k-point parameters for each element or class of materials [1]. - Adopt Automated Parameter Optimization: Use software tools that automate convergence testing and uncertainty quantification. These tools can find the most computationally efficient parameters that guarantee a user-specified target error for a desired property [1].

- Leverage Workflow Managers: Utilize platforms like

FireWorks(as used in TribChem) orAiiDAto automate and manage the execution of complex, multi-step high-throughput calculations, including error handling and data storage [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental connection between Schrödinger's Equation and Density Functional Theory (DFT)?

DFT provides a practical computational method for solving the many-body Schrödinger equation for electrons in a static external potential (e.g., from atomic nuclei). The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems form the theoretical foundation by proving that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all properties of a system, rather than the complex many-body wavefunction. This reduces the problem of 3N variables (for N electrons) to a problem of 3 variables (x,y,z for the density). The Kohn-Sham equations then map the system of interacting electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons with the same density, making the problem computationally tractable.

FAQ 2: My calculation stopped with an error. How can I find out what went wrong?

First, check the main output files (e.g., OUTCAR and stdout in VASP) for error messages. Common issues include:

- Insufficient Memory (RAM): The calculation fails abruptly.

- SCF Convergence Failure: The electronic self-consistent field cycle does not converge. Remedies include increasing

NELM, using admixture (AMIX,BMIX), or employing the Davidson algorithm (ALGO = Normal). - Geometry Convergence Failure: The ionic relaxation does not converge. This may require adjusting the

EDIFFGforce tolerance or the optimization algorithm (IBRION). - Symmetry Errors: Sometimes, symmetry detection in non-standard cells fails. Trying

ISYM = 0(no symmetry) can resolve this.

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right exchange-correlation (XC) functional for my system?

The choice of XC functional is a trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. There is no single "best" functional for all cases.

- LDA (Local Density Approximation): Often underestimates lattice constants and bond lengths. It can be a good starting point but is generally not recommended for high-accuracy studies.

- GGA (Generalized Gradient Approximation): Functionals like PBE are the most widely used. They offer a good balance of accuracy and efficiency for many materials, including metals and semiconductors.

- Meta-GGA and Hybrid Functionals: Functionals like SCAN or HSE06 offer higher accuracy, especially for band gaps and reaction energies, but at a significantly higher computational cost. They are recommended for final, high-precision calculations after initial testing with GGA.

FAQ 4: What is "downfolding" and how is it used in materials science?

Downfolding is a technique to derive a simplified, low-energy effective model (e.g., a Hubbard model) from a first-principles DFT calculation. This is crucial for studying systems with strong electron correlations, such as high-temperature superconductors. Software like RESPACK can be used to construct such models by calculating parameters like the hopping integrals and screened Coulomb interactions using methods based on Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWFs) [3].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

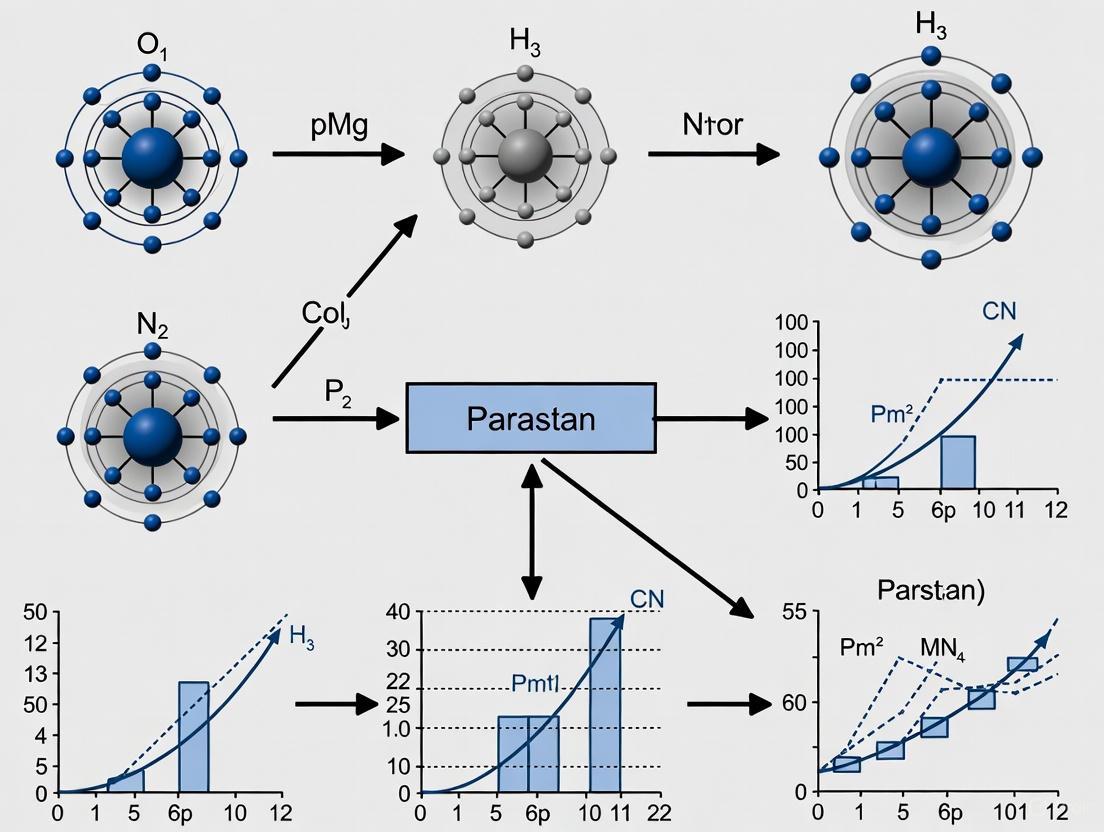

Diagram 1: High-Throughput DFT Workflow

Diagram 2: Parameter Convergence Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software and Databases

The following table details key software tools and databases essential for modern, high-throughput computational materials science.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [2] | DFT Code | Performing first-principles electronic structure calculations. | Industry-standard for materials science; uses plane-wave basis sets and pseudopotentials. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [3] | DFT Code | Open-source suite for electronic-structure calculations. | Community-developed; supports various functionalities including ESM for interfaces [3]. |

| FireWorks [2] | Workflow Manager | Defining, managing, and executing complex computational workflows. | Used in TribChem to automate high-throughput calculations and database storage [2]. |

| TribChem [2] | Specialized Software | High-throughput study of solid-solid interfaces. | Calculates interfacial properties like adhesion and shear strength in an automated fashion [2]. |

| Pymatgen [2] | Python Library | Materials analysis and structure manipulation. | Core library for generating input files and analyzing outputs in high-throughput workflows. |

| Materials Project [2] | Database | Web-based repository of computed materials properties. | Provides pre-calculated data for thousands of materials to guide discovery and validation. |

| RESPACK [3] | Analysis Tool | Deriving effective low-energy models from DFT. | Calculates parameters for model Hamiltonians (e.g., Hubbard model) via Wannier functions [3]. |

| pyiron [1] | Integrated Platform | Integrated development environment for computational materials science. | Supports automated workflows, including convergence parameter optimization and data management [1]. |

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the 'Seven Ds and the little s' method and how is it applied in a research setting?

The 'Seven Ds and the little s' method is a structured problem-solving framework adapted from the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale, which provides a standardized approach for assessing intervention effectiveness. In computational research, this framework allows scientists to quantify progress and treatment response systematically. The method comprises two companion one-item measures: a severity scale (the seven 'D's) and an improvement scale (the 'little s' or status change). For researchers, this translates to a brief, stand-alone assessment that takes into account all available information—including historical data, experimental circumstances, observed symptoms or outcomes, and the impact on overall project functionality. The instrument can be administered in less than a minute by an experienced researcher after a clinical or experimental evaluation, making it suitable for busy lab environments with multiple competing demands [4].

What specific problems does this framework help solve in computational research and drug development?

This framework addresses several critical challenges in computational research and drug development: (1) It provides a standardized metric to quantify and track system response to parameter adjustments over time, (2) It enables consistent documentation of due diligence in measuring outcomes for third-party verification, (3) It helps justify computational resource allocation by documenting intervention non-response, and (4) It creates a systematic approach to identify which parameter optimizations worked or failed across complex research projects. The framework is particularly valuable for high-throughput computational studies where precisely tracking the effectiveness of multiple parameter adjustments is essential for maintaining research integrity and reproducibility [4].

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

How do I diagnose convergence parameter failures in DFT calculations?

Convergence parameter failures manifest as unpredictable results, high energy variances, or inconsistent material property predictions. To diagnose these issues, researchers should:

- Verify Energy Cutoff Sensitivity: Systematically increase the plane-wave energy cutoff (ϵ) and monitor total energy changes. A significant energy shift (exceeding 1 meV/atom) with increasing cutoff indicates inadequate basis set convergence [1].

- Validate k-point Sampling: Test successively denser k-point meshes (κ) until derived properties (e.g., bulk modulus, lattice constants) stabilize within acceptable error margins. Non-monotonic convergence suggests potential aliasing or sampling artifacts [1].

- Distinguish Error Types: Determine whether observed instabilities represent statistical error (from basis set variations with cell volume) or systematic error (from finite basis set limitations). Statistical errors typically dominate at lower precision targets, while systematic errors become predominant for high-precision requirements below 1 meV/atom [1].

Table: Diagnostic Framework for Convergence Parameter Failures

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Procedure | Expected Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unpredictable energy fluctuations | Statistical error from basis set variation | Compute energy variance across multiple volumes | Increase plane-wave energy cutoff |

| Inconsistent material properties | Inadequate k-point sampling | Test denser k-point meshes | Implement automated k-point optimization |

| Systematic deviation from benchmarks | Finite basis set limitation | Asymptotic analysis of energy vs. cutoff | Apply higher precision convergence parameters |

What methodology ensures optimal convergence parameters for target precision?

A robust methodology for determining optimal convergence parameters involves these critical steps:

- Define Target Precision: Establish acceptable error thresholds (Δf_target) for your specific research application before parameter optimization begins [1].

- Multi-dimensional Parameter Scanning: Compute the property of interest (e.g., bulk modulus, lattice constant) across a grid of convergence parameters (ϵ, κ), ensuring broad coverage of the parameter space [1].

- Error Surface Mapping: Construct comprehensive error surfaces by comparing results against highly converged reference values or through asymptotic analysis of the systematic error [1].

- Automated Parameter Selection: Implement algorithms that identify the computational cheapest combination of (ϵ, κ) that satisfies Δf(ϵ, κ) ≤ Δf_target, minimizing resource consumption while maintaining precision requirements [1].

How do I resolve high-contrast visualization issues in computational workflow diagrams?

Visualization issues in high-contrast modes typically stem from improper color resource management and hard-coded color values:

- Implement System Color Resources: Replace hard-coded colors with appropriate SystemColor resources (e.g.,

SystemColorWindowColor,SystemColorWindowTextColor) to ensure automatic theme adaptation [5]. - Disable Automatic Adjustments: Set

HighContrastAdjustmenttoNonefor custom visualizations where you maintain full control over the color scheme, preventing system-level overrides that may reduce clarity [5]. - Apply Backplate Control: Use

-ms-high-contrast-adjust: none;for specific diagram elements where automatic text backplates compromise readability, particularly in hover or focus states [6]. - Validate Color Pairings: Ensure all foreground/background color combinations use compatible system color pairs with sufficient contrast ratios (at least 7:1), such as

SystemColorWindowTextColoronSystemColorWindowColor[5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How often should I reassess convergence parameters when switching research projects?

Convergence parameters should be reassessed whenever changing research projects, particularly when studying different material systems or elements. Evidence shows that elements with similar equilibrium volumes can exhibit dramatically different convergence behaviors due to variations in their underlying electronic structure. Simple scaling relationships based on volume alone cannot capture this complexity, necessitating element-specific parameter optimization for each new research focus [1].

Can I use the same convergence parameters across multiple elements or compounds?

No, using identical convergence parameters across different elements or compounds is not recommended and may compromise research validity. Comprehensive studies demonstrate significant variation in convergence behavior across different elements, even with similar crystal structures. For example, while calcium achieves high precision (0.1 GPa error in bulk modulus) with modest parameters, copper requires substantially higher cutoffs and denser k-point sampling to reach comparable precision levels [1].

What is the practical difference between CGI-Severity and CGI-Improvement in a research context?

In computational research, CGI-Severity (CGI-S) represents the absolute assessment of a system's current problematic state rated on a seven-point scale, while CGI-Improvement (CGI-I) measures relative change from the baseline condition after implementing interventions. Although these metrics typically track together, they can occasionally dissociate—researchers might observe CGI-I improvement relative to baseline despite no recent changes in overall severity, or vice versa, providing nuanced insights into intervention effectiveness [4].

How can I implement automated convergence testing in my research workflow?

Implement automated convergence testing through these implementation steps:

- Leverage Specialized Libraries: Utilize existing frameworks like pyiron that incorporate automated convergence parameter optimization tools [1].

- Define Precision Requirements: Specify target errors for your key research metrics before initiating automated scanning [1].

- Systematic Parameter Variation: Allow algorithms to automatically compute error surfaces across the multidimensional convergence parameter space [1].

- Resource-Aware Selection: Implement automated selection of computational most efficient parameters that satisfy your precision constraints [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Convergence Parameter Optimization in DFT Calculations

Objective: To determine computationally efficient convergence parameters that guarantee precision targets for derived materials properties.

Materials & Setup:

- DFT simulation package (e.g., VASP)

- Pseudopotential library (e.g., VASP PAW 5.4)

- Computational cluster resources

- Automated parameter scanning framework (e.g., pyiron)

Methodology:

- Initialization: Select appropriate pseudopotentials for the target element or compound [1].

- Parameter Space Definition: Establish scanning ranges for energy cutoffs (ϵ) and k-point densities (κ) based on preliminary tests [1].

- Energy Surface Calculation: Compute total energies E(V, ϵ, κ) across multiple lattice constants/volumes for each parameter combination [1].

- Property Extraction: Derive target properties (e.g., equilibrium lattice constant, bulk modulus) from energy-volume relationships for each (ϵ, κ) pair [1].

- Error Quantification: Calculate systematic and statistical errors by comparing to asymptotic references or highly converged calculations [1].

- Optimization: Identify the (ϵ, κ) combination that minimizes computational cost while satisfying Δf(ϵ, κ) ≤ Δf_target [1].

Quality Control:

- Validate against established benchmark systems where available

- Verify error decomposition into systematic and statistical components

- Confirm monotonic convergence behavior for all target properties

Protocol for Implementing High-Contrast Visualization in Research Workflows

Objective: To create accessible computational workflow diagrams that maintain readability across all contrast themes.

Materials:

- Diagramming tool supporting DOT language (Graphviz)

- Windows high-contrast theme testing environment

- Color palette resources

Methodology:

- Theme Dictionary Setup: Create ResourceDictionary collections for Default, Light, and HighContrast themes in your visualization framework [5].

- System Color Implementation: Replace hard-coded colors with appropriate SystemColor resources (e.g.,

SystemColorWindowColor,SystemColorWindowTextColor) in all diagram elements [5]. - Backplate Control: Apply

-ms-high-contrast-adjust: none;to specific elements where automatic adjustments would compromise readability [6]. - Comprehensive Testing: Validate visualization appearance across all four high-contrast themes (Aquatic, Desert, Dusk, Night sky) while the application is running [5].

Quality Control:

- Verify sufficient contrast ratios (≥7:1) for all color combinations

- Ensure consistent color usage across similar element types

- Confirm proper text legibility in both default and high-contrast modes

Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Materials

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Parameter Optimization Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave DFT Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Provides fundamental engine for computing total energy surfaces | Electronic structure calculations across diverse materials systems | Requires careful pseudopotential selection and convergence validation [1] |

| Automated Convergence Tools (pyiron) | Implements efficient parameter optimization algorithms | High-throughput computational materials screening | Reduces computational costs by >10x while maintaining precision [1] |

| Uncertainty Quantification Framework | Decomposes and quantifies statistical and systematic errors | Precision-critical applications (e.g., machine learning potentials) | Enables precision targets below xc-potential error levels [1] |

| High-Contrast Visualization System | Ensures accessibility of computational workflows | Research documentation and publication materials | Requires SystemColor resources and proper contrast validation [5] |

Workflow Visualization Diagrams

FAQs on Configurational Integrals and Physical Quantities

Q1: What is the configurational integral, and why is it important in statistical mechanics? The configurational integral, denoted as ( ZN ), is a central quantity in statistical mechanics that forms the core of the canonical partition function. It is defined as the integral over all possible positions of the particles in a system, weighted by the Boltzmann factor [7]: [ ZN = \int e^{-\beta U(\mathbf{q})} d\mathbf{q} ] Here, ( U(\mathbf{q}) ) is the potential energy of the system, which depends on the coordinates ( \mathbf{q} ) of all N particles, ( \beta = 1/kB T ), ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature [8]. This integral is crucial because it encodes the effect of interparticle interactions on the system's thermodynamic properties. Once ( Z_N ) is known, fundamental thermodynamic quantities like the Helmholtz free energy can be directly derived, providing a bridge from microscopic interactions to macroscopic observables [9].

Q2: How do I ensure the physical dimensions in my calculations are consistent? In quantum and statistical mechanics, consistency of physical dimensions is as critical as in classical physics. Operators representing physical observables (e.g., position ( \hat{x} ), momentum ( \hat{p} )) have inherent dimensions. When performing operations like adding two operators, their dimensions must match, which may require introducing appropriate constants [10]. For instance, while an expression like ( \hat{L}^2 + \hat{L}z ) is dimensionally inconsistent, ( \hat{L}^2 + \hbar \hat{L}z ) is valid because the reduced Planck's constant ( \hbar ) carries units of angular momentum [10]. Similarly, eigenvalues of operators carry the same physical dimensions as the operators themselves; the eigenvalue ( x0 ) in the equation ( \hat{X}|x0\rangle = x0|x0\rangle ) has units of length [10].

Q3: What are the main computational challenges in evaluating the configurational integral? The primary challenge is the "curse of dimensionality." The integral is over 3N dimensions (three for each particle), making traditional numerical methods intractable for even a modest number of particles (N) [7]. For example, a simple numerical integration with 100 nodes in each dimension for a system of 100 particles would require ( 10^{200} ) function evaluations—a computationally impossible task [7]. This complexity is compounded for condensed matter systems with strong interparticle interactions, making the direct evaluation of ( Z_N ) one of the central challenges in the field [7].

Q4: My first-principles calculations are not converging. Which parameters should I check? In plane-wave Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, the two most critical convergence parameters are the plane-wave energy cutoff (( \epsilon )) and the k-point sampling (( \kappa )) [1]. The energy cutoff determines the completeness of the plane-wave basis set, while the k-point sampling controls the integration over the Brillouin zone. Inaccurate settings for these parameters are a common source of non-convergence and errors in derived properties like the equilibrium lattice constant or bulk modulus [1]. Modern automated tools can help determine the optimal parameters by constructing error surfaces and identifying settings that minimize computational cost while achieving a user-defined target error [1].

Q5: When should I use first-principles calculations over classical molecular dynamics (MD)? First-principles (or ab initio) calculations are necessary when the phenomenon of interest explicitly involves the behavior of electrons [11]. This includes simulating electronic excitation (e.g., due to light), electron polarization in an electric field, and chemical reactions where bonds are formed or broken [11]. In contrast, classical MD relies on pre-defined force fields and treats electrons implicitly, typically through partial atomic charges. It cannot simulate changes in electronic state and is best suited for studying the structural dynamics and thermodynamic properties of systems where the bonding network remains unchanged [11].

Troubleshooting Common Computational Issues

DFT Convergence Problems

Problem: Unconverged total energy or inaccurate material properties (e.g., bulk modulus, lattice constants).

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large changes in total energy with small parameter changes | Insufficient plane-wave energy cutoff (( \epsilon )) | Systematically increase the energy cutoff until the change in total energy is below your target precision (e.g., 1 meV/atom) [1]. |

| Oscillations in energy-volume curves | Inadequate k-point sampling (( \kappa )) | Use a denser k-point mesh, especially for metals or systems with complex electronic structure [1]. |

| Inconsistent results across different systems | Using a "one-size-fits-all" parameter set | Element-specific convergence parameters are essential. Use automated tools to find the optimal (( \epsilon ), ( \kappa )) pair for each element to achieve a defined target error [1]. |

Handling High-Dimensional Integrals

Problem: The configurational integral ( Z_N ) is computationally intractable for direct evaluation.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential scaling of computational cost | The "curse of dimensionality" for traditional grid-based integration methods [7]. | Employ advanced numerical techniques like Tensor Train (TT) decomposition. This method represents the high-dimensional integrand as a product of smaller tensor cores, dramatically reducing computational complexity [7]. |

| Inefficient sampling of configuration space | Poor Monte Carlo sampling efficiency in complex energy landscapes. | Consider using the Cluster Expansion (CE) method. It is a numerically efficient approach to estimate the energy of a vast number of configurational states based on a limited set of initial DFT calculations, facilitating thermodynamic averaging [8]. |

Key Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: Automated Optimization of DFT Convergence Parameters

Objective: To determine the computationally most efficient plane-wave energy cutoff (( \epsilon )) and k-point sampling (( \kappa )) that guarantee a predefined target error for a derived material property (e.g., bulk modulus) [1].

- Define Target Quantity and Error: Select the property of interest (e.g., bulk modulus, equilibrium volume) and set the desired target error (e.g., 0.1 GPa).

- Generate Data Grid: Perform a set of DFT calculations for the material across a range of volumes, spanning a grid of different (( \epsilon ), ( \kappa )) values.

- Construct Error Surface: For each (( \epsilon ), ( \kappa )) pair on the grid, fit the energy-volume data to an equation of state (e.g., Birch-Murnaghan) to compute the derived property. The error for each point is defined as the difference from the value at the highest (most converged) parameters.

- Decompose Errors: Analyze the error surface to separate systematic errors (from finite basis set) and statistical errors (from varying cell volume). The systematic error from multiple parameters is often additive [1].

- Identify Optimal Parameters: Locate the (( \epsilon ), ( \kappa )) pair on the error surface where the contour line of your target error is met, selecting the one with the lowest computational cost.

The following workflow visualizes this automated optimization process:

Protocol: Calculating Thermodynamic Properties via the Configurational Integral

Objective: To compute equilibrium thermodynamic properties, such as free energy and defect concentrations, at finite temperatures by accounting for configurational entropy [8].

- Define the System and Reservoir: Identify the material system and the reservoir of atoms/molecules with which it can exchange particles. This defines the constant thermodynamic conditions (e.g., constant temperature T and partial pressure p) [8].

- Sample the Configurational Space: Evaluate the configurational density of states (DOS), which requires calculating the energies of a large number of atomic configurations. The Cluster Expansion (CE) method can be used as an efficient approach to this sampling problem [8].

- Construct the Partition Function: Form the canonical partition function ( QN ) using the configurational integral ( ZN ), which sums the Boltzmann factor over all sampled configurational states [7].

- Compute Thermodynamic Potentials: Derive the Helmholtz free energy (F) or Gibbs free energy (G) from the partition function. At finite temperature, the system minimizes its free energy, not just its internal energy [8].

- Determine Equilibrium State: Find the state (e.g., phase, defect concentration) that minimizes the appropriate free energy. The chemical potential (( \mu )), derived from the free energy, will be equal throughout the system and reservoir at equilibrium [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational "reagents" and methodologies used in advanced materials modeling.

| Item/Concept | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Configurational Integral (( Z_N )) | A high-dimensional integral over all particle positions; the cornerstone for calculating thermodynamic properties from microscopic interactions [7]. |

| Cluster Expansion (CE) | A numerically efficient method to estimate energies of numerous atomic configurations, enabling the sampling of configurational entropy needed for finite-temperature thermodynamics [8]. |

| Tensor Train (TT) Decomposition | A mathematical technique that breaks down high-dimensional tensors (like the Boltzmann factor) into a chain of smaller tensors, overcoming the "curse of dimensionality" in integral evaluation [7]. |

| Chemical Potential (( \mu )) | The change in free energy upon adding a particle; its equality across different parts of a system defines thermodynamic equilibrium, crucial for predicting defect concentrations and surface phase diagrams [8]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional (in DFT) | An approximation that accounts for quantum mechanical electron-electron interactions; its choice (LDA, GGA, hybrid) critically determines the accuracy of DFT calculations [11]. |

| Virtual Parameter Variation (VPV) | A simulation technique to calculate derivatives of the configurational partition function, allowing direct computation of properties like pressure and chemical potential without changing the actual simulation parameters [9]. |

| Plane-Wave Energy Cutoff (( \epsilon )) | A key convergence parameter in plane-wave DFT that controls the number of basis functions used to represent electron wavefunctions, directly impacting the accuracy and computational cost [1]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when dealing with the exponential wall of complexity in first-principles calculations, particularly for systems containing transition metals and rare-earth elements.

Q: My DFT+U calculations for transition metal oxides yield inconsistent electronic properties. What is the likely cause and how can I resolve this?

A: Inconsistencies often stem from using a single, fixed Hubbard U value. The onsite U is not a universal constant; it is highly sensitive to the local chemical environment [12]. For example, the U value for the 3d orbitals of Mn can vary by up to 6 eV, with shifts of about 0.5-1.0 eV due to changes in oxidation state or local coordination [12]. The solution is to adopt a self-consistent Hubbard parameter calculation workflow.

- Procedure: Implement a cyclic workflow where a new set of U (and V) parameters is computed from a DFT+U(+V) ground state that was determined using the Hubbard parameters from the previous step [12]. This self-consistent cycle ensures the parameters are consistent with the electronic ground state.

- Tool: Use automated frameworks like

aiida-hubbard, which leverages density-functional perturbation theory (DFPT) to compute these parameters efficiently without expensive supercells [12] [13].

Q: How do I account for interactions between atoms in my correlated system, and why is it important?

A: Onsite U corrections alone may be insufficient. Intersite V parameters are crucial for stabilizing electronic states that are linear combinations of atomic orbitals on neighboring atoms [12]. These interactions are important for accurately describing redox chemistry and the electronic structure of extended systems.

- Procedure: Employ a method that can compute intersite V parameters on-the-fly during the self-consistent procedure to account for atomic relaxations and diverse coordination environments [12].

- Finding: Intersite V values for transition-metal and oxygen interactions typically range between 0.2 eV and 1.6 eV and generally decay with increasing interatomic distance [12].

Q: Geometry optimization of large organic molecules is computationally prohibitive. Are there more efficient methods?

A: Yes, nonparametric models like physical prior mean-driven Gaussian Processes (GPs) can significantly accelerate the exploration of potential-energy surfaces and molecular geometry optimizations [14].

- Procedure: This method uses a surrogate model built on-the-fly. The key to performance is the synergy between the kernel function and the coordinate system [14].

- Recommended Protocol: For oligopeptides, the combination of a periodic kernel with non-redundant delocalized internal coordinates has been shown to yield superior performance in locating local minima compared to other combinations [14].

Q: How can I ensure the reproducibility of my Hubbard-corrected calculations?

A: Reproducibility is a major challenge. To address it:

- Use Structured Data: Employ a code-agnostic data structure (e.g.,

HubbardStructureDatain AiiDA) to store all Hubbard-related information—including the atomistic structure, projectors, and parameter values—along with the computational provenance [12] [13]. - Adopt FAIR Principles: Utilize computational infrastructures like AiiDA that automate workflows and ensure data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) [12].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings and methodologies from recent literature to guide your experimental design.

Table 1: Ranges of Self-Consistent Hubbard Parameters in Bulk Solids [12]

| Element / Interaction | Hubbard Parameter | Typical Range (eV) | Key Correlation Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe (3d orbitals) | Onsite U | Up to 3 eV variation | Oxidation state, coordination environment |

| Mn (3d orbitals) | Onsite U | Up to 6 eV variation | Oxidation state, coordination environment |

| Transition Metal & Oxygen | Intersite V | 0.2 - 1.6 eV | Interatomic distance (general decay with distance) |

Table 2: Performance of Gaussian Process Optimization for Oligopeptides [14]

| Kernel Functional | Coordinate System | Synergy & Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic Kernel | Non-redundant Delocalized Internal Coordinates | Superior overall performance and robustness in locating local minima. |

| Squared Exponential (SE) | Various Internal Coordinates | Less effective than the periodic kernel for this specific task. |

| Rational Quadratic | Various Internal Coordinates | Less effective than the periodic kernel for this specific task. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential computational "reagents" – the software, functions, and data structures crucial for tackling complexity in first-principles research.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Advanced First-Principles Calculations

| Item Name | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

aiida-hubbard |

An automated Python package for self-consistent calculation of U and V parameters, ensuring reproducibility and handling high-throughput workflows [12]. |

| DFPT (HP Code) | Replaces expensive supercell approaches with computationally cheaper primitive cell calculations for linear-response Hubbard parameter computation [12] [13]. |

| HubbardStructureData | A flexible data structure that stores the atomistic structure alongside all Hubbard-specific information, enhancing reproducibility [12]. |

| Physical GPs with Periodic Kernel | A nonparametric model that uses a physics-informed prior mean to efficiently optimize large molecules (e.g., oligopeptides) by learning a surrogate PES on-the-fly [14]. |

| Non-redundant Delocalized Internal Coordinates | A coordinate system that, when paired with the periodic kernel in GP optimization, provides an efficient search direction for complex molecular relaxations [14]. |

Workflow Diagrams

The following diagrams visualize the core protocols and logical relationships described in this guide.

Advanced Methods and High-Impact Applications in Biomedicine and Materials

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Computational Workflow Errors

| Error Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation Convergence | Self-consistent field (SCF) failure in DFT+U calculations | Improper Hubbard U/V parameters, problematic initial structure | Implement self-consistent parameter calculation; check structure integrity | [12] |

| Software & Data Integrity | Protocol interruption during automated dispensing | Air pressure connection issue, misaligned dispense head, missing source wells | Verify air supply (3-10 bar), check head alignment and source plate | [15] |

| Data Management | Inconsistent or irreproducible results | Lack of standardized data structure for key parameters | Implement unified data schema to track molecules, genealogy, and assay data | [16] |

| Performance & Accuracy | Incorrect liquid class assignment in liquid handling | Missing or incorrect liquid class settings in software | Assign or create appropriate liquid class for the selected protocol | [15] |

| System Communication | "Communication issue with distribution board" error on startup | Loose cables, software launched too quickly after power-on | Secure all cables, launch software 10-15 seconds after powering device | [15] |

Liquid Handling and Instrument Performance

DropDetection Verification Issues

- Problem: False positives (no liquid dispensed, but software detects droplets) or false negatives (liquid dispensed, but software does not detect droplets).

- Validation Protocol:

- For false positives: Use a new, unused source plate to dispense liquid. The result should show red in all 96 positions, indicating a failure, which confirms the system is detecting the lack of liquid correctly. [15]

- For false negatives: Fill each source well with 10-20 µL of deionized water (avoiding air bubbles). Execute a protocol to dispense 500 nL from each source well to each corresponding target well (A1 to A1, B1 to B1, etc.). Repeat three to five times. [15]

- Acceptance Criteria: The number of droplets not detected in random positions should not be greater than 1%. For a 96-well plate dispensing 11 droplets per well (total 1056 drops), no more than 10 droplets overall should be undetected. [15]

- Resolution:

Target Droplets Landing Out of Position

- Problem: Droplets are dispensed inconsistently to the left, right, or in a tilted pattern.

- Diagnostic Protocol:

- Dispense deionized water from source wells A1 and H12 to the center and four corners of a transparent, foil-sealed 1536 target well plate.

- Visually inspect if the droplet pattern is consistently shifted or tilted. [15]

- Solution: Access general settings, click "Show Advanced Settings," enter the password, click "Move To Home," and adjust the target tray position. Restart the software. [15]

Pressure Leakage/Control Error

- Problem: Errors related to pressure control during dispensing.

- Solution Checklist: [15]

- Ensure source wells are fully seated in the plate.

- Verify the dispense head channel and source wells are correctly aligned (X/Y direction).

- Check the dispense head distance to the source wells is approximately 1 mm (use a 0.8 mm plastic card as a gauge).

- Inspect the head rubber for damage (cuts or rips).

- Listen for any whistling sounds indicating a leak. Contact support if any issues are found.

Workflow Optimization and Bottlenecks

Data Overload in Automated Discovery

- Problem: A single automated molecular cloning batch can generate over 1.1 million unique metadata points, creating analysis bottlenecks. [17]

- Solution: Implement a centralized, structured software system that acts as a "data rail," integrating data capture, parsing, visualization, and analytical tools for expedited decision-making. [17]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Workflow Design and Implementation

Q: What are the primary objectives when designing a high-throughput screening workflow? A: The goal is typically either optimization (enhancing a target property to find a high-performance material) or exploration (mapping a structure-property relationship to build a predictive model). The choice dictates library design and statistical tools. [18]

Q: How can I estimate the size of my experimental design space? A: Identify all relevant features (e.g., composition, architecture, reaction conditions). Then, subdivide each feature into a set of intervals spanning your desired range. The product of the number of levels for each variable estimates the total design space size, which can be vast. [18]

Q: What is a key requirement for applying AI and machine learning to discovery data? A: Data must be structured and consolidated using a consistent data schema. This allows for effective searching, traceability, and the reliable application of AI models. Manual data handling in spreadsheets is a major obstacle. [16]

Instrument Operation and Hardware

Q: Can I use an external PC or WiFi with my I.DOT Liquid Handler? A: Remote access is possible by connecting an external PC through the LAN port. However, WiFi and Bluetooth must be turned off for proper operation. Use a LAN connection or contact support for details. [15]

Q: The source or target trays on my instrument will not eject. What should I do? A: This often occurs because the control software (e.g., Assay Studio) has not been launched. Ensure the software is running first. If the device is off, the doors can be opened manually. [15]

Q: What is the smallest droplet volume I can dispense? A: The minimum volume depends on the specific source plate and the liquid being dispensed. For example, with DMSO and an HT.60 plate, the smallest droplet is 5.1 nL, while with an S.100 plate, it is 10.84 nL. [15]

Data and Analysis

Q: How can I ensure the reproducibility of my computational high-throughput calculations, like DFT+U? A: Employ a framework that automates workflows and, crucially, uses a standardized data structure to store all calculation parameters (like Hubbard U/V values) together with the atomistic structure. This enhances reproducibility and FAIR data principles. [12]

Q: Are there automated workflows for analyzing chemical reactions? A: Yes. New workflows exist that apply statistical analysis (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Markov Chain) to NMR data, enabling rapid identification of molecular structures and isomers directly from unpurified reaction mixtures in hours instead of days. [19]

Workflow Visualization

Generic High-Throughput Discovery Workflow

Computational Parameter Optimization (e.g., DFT+U)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Key Components for Automated Workflows

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| I.DOT Source Plates (e.g., HT.60) | Designed for specific liquid classes with defined pressure boundaries. | Enables ultra-fine droplet control (e.g., 5.1 nL for DMSO). [15] |

| Pre-tested Liquid Class Library | Standardized, pre-tested settings for different liquids, defining dosing energy. | Streamlines workflows by providing tailored settings for liquids like methanol or glycerol. [15] |

| Liquid Class Mapping/Creation Wizards | Software tools to map new liquids to optimal settings or create custom liquid classes. | Handles unknown or viscous compounds by identifying optimal dispensing parameters. [15] |

| Validated Force Fields (e.g., OPLS4) | Parameter sets for classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. | Accurately computes properties like density and heat of vaporization for solvent mixtures in high-throughput screening. [20] |

| Hubbard-corrected Functionals (DFT+U+V) | Corrects self-interaction error in DFT for localized d and f electrons. | Improves electronic structure prediction in transition-metal and rare-earth compounds. [12] |

| Automated Workflow Software (e.g., aiida-hubbard) | Manages complex computational workflows, ensuring provenance and reproducibility. | Self-consistent calculation of Hubbard parameters for high-throughput screening of materials. [12] |

| Centralized Data Platform (LIMS/ELN) | Integrated platform for molecule registration, material tracking, and experiment planning. | Provides a unified data model, essential for traceability and AI/ML analysis in large-molecule discovery. [16] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My ab initio random structure search (AIRSS) is not converging to the global minimum and seems stuck in high-energy local minima. What strategies can I use to improve the sampling?

A1: Efficient sampling is a common challenge. You can employ several strategies to bias your search towards more promising regions of the potential energy surface:

- Integrate Molecular Dynamics Annealing: Incorporate long, high-throughput molecular dynamics (MD) anneals between direct structural relaxations. This approach, known as hot-AIRSS, uses machine-learning interatomic potentials to make the MD steps computationally feasible. It helps the system escape local minima by leveraging thermal energy, thereby biasing the sampling towards low-energy configurations for challenging systems like complex boron structures [21].

- Use Biased Initial Configurations: Instead of purely random seeding, generate initial structures with a controlled physical bias. For example, the TETRIS seeding method creates compact starting configurations for nanoparticles or atomic blocks for crystals by ensuring physically sensible interatomic distances. This can significantly speed up the convergence to the global minimum, especially for systems with complex covalent networks [22].

- Leverage Higher-Dimensional Optimization: Perform the initial stochastic generation and part of the optimization in a hyperspace with extra spatial dimensions. The Global Optimization of Structures from Hyperspace (GOSH) method allows atoms to explore relaxation pathways unavailable in 3D space. After a period of exploration in higher dimensions, the structure is gradually projected back to 3D for final relaxation, which can enhance the probability of finding lower-energy configurations [22].

Q2: For variable-composition searches, how can I efficiently manage a multi-objective optimization that considers both energy and specific functional properties?

A2: Evolutionary algorithms like XtalOpt have been extended to handle this exact scenario using Pareto optimization.

- In this framework, your objectives (e.g., formation energy, band gap, bulk modulus) are calculated for all relaxed structures.

- The algorithm then identifies the Pareto front—the set of structures for which no single objective can be improved without worsening another.

- Parents for the next generation are selected from this non-dominated front, allowing the evolutionary search to naturally progress towards a diverse set of solutions that optimally balance your target properties, rather than converging to a single point that only minimizes energy [23].

Q3: How can I accelerate expensive ab initio geometry optimizations for large, flexible molecules like oligopeptides?

A3: Surrogate model-based optimizers can drastically reduce the number of costly quantum mechanical (QM) calculations required.

- The Physical Gaussian Processes (GPs) method is an on-the-fly learning model that constructs a surrogate potential energy surface (SPES).

- It starts with a physics-informed prior mean function (e.g., from a classical force field) and iteratively refines the SPES using energies and forces computed from accurate QM calculations at select points.

- The optimization then proceeds on the computationally cheap SPES. The key to efficiency is the synergy between the kernel function and coordinate system. For oligopeptides, the combination of a periodic kernel with non-redundant delocalized internal coordinates has been shown to yield the best performance, significantly outperforming standard optimizers [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Performance in Contact-Guided Protein Structure Prediction

Problem: When using predicted inter-residue contacts to guide ab initio protein folding (e.g., in C-QUARK), the modeling accuracy is low, especially when contact-map predictions are sparse or of low accuracy.

Diagnosis: The force field is not effectively balancing the noisy contact restraints with the other knowledge-based energy terms. The inaccuracies are leading the simulation down incorrect folding pathways.

Solution: Implement a multi-tiered contact potential that is robust to prediction errors.

- Action 1: Utilize Multiple Contact Predictors. Do not rely on a single source. Generate contact-maps using both deep-learning and co-evolution-based predictors to create a more reliable consensus [24].

- Action 2: Apply a 3-Gradient (3G) Contact Potential. This potential features three smooth platforms to handle different distance gradients. It is less sensitive to the specific accuracy of individual contact predictions and provides a more balanced guidance during the Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) fragment assembly simulations [24].

- Verification: Benchmark the updated protocol on a set of non-homologous protein targets. A correctly implemented solution should show a significant increase in the number of targets achieving a TM-score ≥ 0.5 compared to the unguided approach [24].

Issue: Handling Complex Bonding in Materials with Strong Electron Correlation

Problem: Standard (semi)local DFT functionals inaccurately describe the electronic structure of materials with localized d or f electrons, leading to incorrect predicted geometries and energies.

Diagnosis: The self-interaction error in standard DFT causes an unphysical delocalization of electrons and fails to describe strong correlation effects.

Solution: Apply a first-principles Hubbard correction (DFT+U+V).

- Action 1: Use an Automated Workflow. Employ a framework like

aiida-hubbardto self-consistently compute the onsite U and intersite V parameters using density-functional perturbation theory (DFPT). This avoids the use of empirical parameters and ensures reproducibility [12]. - Action 2: Achieve Self-Consistency. Run the calculation iteratively, where the Hubbard parameters are computed from a DFT+U(+V) ground state obtained using the parameters from the previous step. This cycle should be combined with structural optimizations for a mutually consistent ionic and electronic ground state [12].

- Verification: Check the electronic density of states for the corrected system. A successful correction should open a band gap in insulators or provide a more accurate description of states near the Fermi level in metals, and typically results in improved geometric structures [12].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Hot-AIRSS for Complex Materials

Objective: To find the global minimum energy structure of a complex solid (e.g., boron) by enhancing a standard AIRSS with machine-learning accelerated annealing [21].

- Step 1 - Initialization: Define the chemical composition, external pressure, and a range for the number of atoms in the unit cell.

- Step 2 - Structure Generation: Stochastically generate a population of initial "random sensible" structures. Apply basic physical constraints like minimum interatomic distances.

- Step 3 - Ephemeral Data-Derived Potential (EDDP) Construction: On-the-fly, train a machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP) using a subset of the structures relaxed with DFT. This EDDP will provide a fast, approximate potential for the next step.

- Step 4 - Hot Sampling: For each candidate structure, perform a long molecular dynamics simulation (e.g., annealing) using the EDDP. This allows the system to overcome energy barriers.

- Step 5 - Final Relaxation: Quench the annealed structure from Step 4 and perform a full local geometry relaxation using accurate DFT.

- Step 6 - Analysis & Iteration: Collect the final enthalpies and structures. The process (Steps 2-5) is repeated for many random seeds. The lowest-enthalpy structure across all runs is the predicted ground state.

Diagram 1: Hot-AIRSS enhanced search workflow.

Performance Data for Structure Search Methods

Table 1: Benchmarking results of different structure prediction algorithms on various test systems.

| Method | System Type | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-QUARK | 247 Non-redundant Proteins | Success Rate (TM-score ≥ 0.5) | 75% (vs. 29% for baseline QUARK) | [24] |

| GOSH | Lennard-Jones Clusters | Probability Enhancement (vs. 3D search) | Up to 100x improvement for some clusters | [22] |

| TETRIS Seeding | Cu-Pd-Ag Nanoalloys | Efficiency Improvement | More direct impact than GOSH for multi-component clusters | [22] |

| AIRSS | Dense Hydrogen | Discovery Outcome | Predicted mixed-phase structures (e.g., C2/c-24) | [21] |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential software tools and algorithms for computational structure prediction.

| Item Name | Function / Description | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| AIRSS | High-throughput first-principles relaxation of diverse, stochastically generated structures. | Unbiased exploration of energy landscapes for crystals, clusters, and surfaces [21]. |

| XtalOpt | Open-source evolutionary algorithm for crystal structure prediction with Pareto multi-objective optimization. | Finding stable phases with targeted functional properties; variable-composition searches [23]. |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs / EDDPs) | Fast, approximate potentials trained on DFT data to accelerate sampling and molecular dynamics. | Enabling long anneals in hot-AIRSS; pre-screening in high-throughput searches [21] [22]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Optimizer | Non-parametric surrogate model for accelerating quantum mechanical geometry optimizations. | Efficient local minimization of large, flexible molecules like oligopeptides [14]. |

| DFT+U+V | First-principles correction to DFT using Hubbard U (onsite) and V (intersite) parameters. | Accurately modeling electronic structures of strongly correlated materials [12]. |

Troubleshooting Common ML-DFT Workflow Issues

Why is my ML-predicted interface energy significantly different from my DFT validation calculation?

This discrepancy often arises from a mismatch between the data the model was trained on and the new systems you are evaluating.

- Cause 1: Inadequate Feature Descriptors. The machine learning model's feature descriptors (input parameters) may not fully capture the physical or chemical properties of your new, unseen data.

- Solution: Revisit feature engineering. The study on SiCp/Al composites refined feature descriptors via feature engineering to better represent the interface segregation and binding energy problem [25].

- Cause 2: Data Distribution Shift. The new element or structure you are testing may lie outside the feature space represented in your original training dataset.

- Solution: Retrain your model by incorporating the new, correct DFT data into your existing dataset. This continuously improves the model's predictive capability and expands its applicability domain [25].

- Cause 3: Overfitting on a Small Dataset. The model may have learned the noise in your limited training data rather than the underlying physical principles.

- Solution: Implement regularization techniques, use a simpler model, or gather more diverse training data. The ANN model for SiCp/Al screening was selected based on high R² and low MSE metrics, indicating a good fit without overfitting [25].

How do I diagnose poor performance of my machine learning model for material property prediction?

Systematically evaluate your model using standard performance metrics. The table below summarizes key metrics and their interpretations for regression tasks common in energy calculation problems.

Table: Key Performance Metrics for Regression Models in ML-DFT

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (R-Squared) | ( 1 - \frac{\sum(yj - \hat{y}j)^2}{\sum(y_j - \bar{y})^2} ) | Proportion of variance in the target variable that is predictable from the features. [26] | Close to 1.0 |

| MSE (Mean Squared Error) | ( \frac{1}{N}\sum(yj - \hat{y}j)^2 ) | Average of the squares of the errors; heavily penalizes large errors. [26] | Close to 0 |

| RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) | ( \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum(yj - \hat{y}j)^2} ) | Square root of MSE; error is on the same scale as the target variable. [26] | Close to 0 |

| MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | ( \frac{1}{N}\sum|yj - \hat{y}j| ) | Average of the absolute errors; more robust to outliers. [26] | Close to 0 |

If your model shows poor metrics, consider the following actions:

- Low R²: The model fails to explain the variance in your data. Consider using more representative feature descriptors or a different model architecture [25].

- High MSE/RMSE: The model's predictions are, on average, far from the true values. This could be due to insufficient training data, underfitting, or the presence of outliers. Check your dataset for errors and consider increasing model complexity or data volume.

- Compare MAE and RMSE: If RMSE is significantly higher than MAE, your model is making a few large errors, indicating potential outliers in your data or a need for error-sensitive applications to use MSE as a loss function [26].

My DFT calculations are too slow, even for generating training data. How can I optimize them?

The core of achieving 100,000x acceleration is using ML to bypass the vast majority of DFT calculations. However, optimizing the necessary DFT calculations is crucial.

- Strategy 1: Automated Convergence Parameter Optimization. Manually selecting plane-wave cutoff energy (ϵ) and k-point sampling (κ) is inefficient. Use automated tools that employ uncertainty quantification to find the computationally most efficient parameters that guarantee your target precision.

- Solution: Implement tools like those demonstrated for bulk fcc metals, which can reduce computational costs by more than an order of magnitude by predicting optimal (ϵ, κ) pairs for a given target error in properties like the bulk modulus [1].

- Strategy 2: Start with Standard Parameters. While sub-optimal, starting with parameters from high-throughput databases like the Materials Project can provide a baseline, though be aware they may have errors of 5 GPa or more for certain properties [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most suitable machine learning models for accelerating first-principles calculations?

The best model depends on your specific problem and dataset size. In screening for interfacial modification elements in SiCp/Al composites, six models were evaluated: RBF, SVM, BPNN, ENS, ANN, and RF. The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model was ultimately selected based on its performance in R² and Mean Squared Error (MSE) metrics [25]. Start with tree-based models like Random Forest (RF) for smaller datasets and ANN for larger, more complex datasets.

Q2: How do I ensure my ML-accelerated results are physically meaningful and reliable?

Robust validation is non-negotiable.

- Use a Hold-Out Test Set: Always reserve a portion of your DFT-calculated data to test the final model. This evaluates its performance on unseen data.

- Employ Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation during model training to ensure its performance is consistent across different subsets of your training data.

- Physical Sanity Checks: Compare ML predictions with established physical laws or known experimental/calculational trends for similar systems. A prediction that violates basic physics is a red flag.

- Uncertainty Quantification: For DFT calculations, always report the systematic and statistical errors associated with your convergence parameters to provide context for the precision of your training data [1].

Q3: Our goal is 100,000x acceleration. Where does this massive speedup come from?

The acceleration is achieved by changing the computational paradigm.

- DFT Calculation (Slow): Solving the Kohn-Sham equations for a single structure is computationally intensive and scales poorly with system size [27].

- ML Inference (Fast): After training, a machine learning model can predict properties like energy in milliseconds. The "100,000x" figure comes from the fact that you only need to run a limited number of DFT calculations to generate training data. Once the model is trained, you can screen hundreds of thousands or millions of candidate materials (e.g., 89 elements in the SiCp/Al study [25]) at the computational cost of a simple matrix multiplication, effectively bypassing the need for explicit DFT calculations for the vast majority of candidates.

Q4: Can this approach be applied beyond materials science, for example in drug discovery?

Absolutely. The paradigm of using machine learning to learn from expensive, high-fidelity simulations (like DFT or molecular dynamics) and then rapidly screening a vast chemical space is directly applicable to drug discovery. For instance, ML is used to screen potential drug candidates, predict drug interactions, and analyze patient data [28]. Furthermore, breakthroughs in high-performance computing now allow for quantum simulations of biological systems comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms, providing highly accurate training data for ML models to accelerate drug discovery [29].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: ML-Accelerated Screening of Alloying Elements for Composite Interfaces

This protocol is based on the methodology used to screen modification elements for SiCp/Al composites [25].

1. Generate First-Principles Training Data

- Software: Use a DFT code such as CASTEP, VASP, or Quantum ESPRESSO [25] [27].

- Method: Employ the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) with a PBE functional and ultra-soft pseudopotentials [25].

- Calculation:

- Construct an interfacial model (e.g., between SiC and Al).

- For a subset of elements (e.g., 25), calculate the interface segregation energy and interface binding energy using the equations:

- ( E{\text{segregation}} = E{\text{interface}} - E_{\text{inside}} ) (Energy when element is at interface vs. inside the matrix)

- ( E{\text{binding}} = E{\text{interface}} - E{\text{SiC}} - E{\text{basis}} ) (Energy of the bonded interface system)

- Ensure geometry optimization is performed before energy calculations with forces ≤ 0.3 eV/nm.

2. Feature Engineering and Dataset Creation

- Identify elemental properties that are most suitable as descriptors for the target properties (interface segregation energy and binding energy) [25].

- Compile these features for the elements in your training set to form the complete dataset.

3. Machine Learning Model Training and Selection

- Train multiple machine learning models (e.g., RBF, SVM, BPNN, ENS, ANN, RF) on your dataset.

- Evaluate models using metrics like R² and MSE.

- Select the best-performing model (e.g., ANN was selected in the reference study).

4. High-Throughput Prediction and Validation

- Use the trained model to predict the interface energies for a large set of new elements (e.g., 89 elements).

- Select promising candidate elements based on prediction criteria (e.g., negative segregation energy and enhanced binding energy).

- Crucially, validate the ML predictions by performing full DFT calculations on a subset of the top candidates to confirm accuracy.

Protocol: Automated Optimization of DFT Convergence Parameters

This protocol is based on automated approaches for uncertainty quantification in plane-wave DFT calculations [1].

1. Define Target Quantity and Precision

- Identify the primary quantity of interest (QoI) for your study, e.g., equilibrium bulk modulus ((B_{eq})), lattice constant, or cohesive energy.

- Define the required target error ((\Delta f_{\text{target}})) for this quantity (e.g., 1 GPa for the bulk modulus).

2. Compute Energy-Volume Dependence Over Parameter Grid

- Calculate the total energy (E(V, \epsilon, \kappa)) for a range of:

- Volumes ((V)) around the equilibrium value.

- Plane-wave cutoffs ((\epsilon)).

- k-point densities ((\kappa)).

- This creates a multi-dimensional grid of energy calculations.

3. Construct and Analyze Error Surfaces

- For each ((\epsilon, \kappa)) pair, fit the (E(V)) data to an equation of state to derive the QoI (e.g., (B_{eq}(\epsilon, \kappa))).

- Decompose the error into systematic error (from finite basis set) and statistical error (from volume-dependent basis set change) [1].

- Plot the error surface for your QoI as a function of (\epsilon) and (\kappa).

4. Select Optimal Convergence Parameters

- The optimal set of convergence parameters ((\epsilon{\text{opt}}, \kappa{\text{opt}})) is the one that minimizes computational cost while ensuring the total error in the QoI is less than (\Delta f_{\text{target}}).

- Automated tools can identify this point on the error surface, often achieving more than an order of magnitude reduction in cost compared to conservative manual parameter selection [1].

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram: ML-Accelerated High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Diagram: Automated DFT Convergence Parameter Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Software and Computational Tools for ML-Accelerated DFT

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASTEP / VASP | DFT Code | Performs first-principles quantum mechanical calculations using DFT. | Generating the foundational training data by calculating energies, electronic structures, and other properties for a training set of materials. [25] [27] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT Code | An integrated suite of Open-Source computer codes for electronic-structure calculations. | Alternative for performing plane-wave DFT calculations to generate training data. Well-documented with tutorials. [30] [27] |

| BerkeleyGW | Beyond-DFT Code | Computes quasiparticle energies (GW) and optical spectra (BSE). | Providing high-accuracy electronic structure data for training ML models on properties like band gaps. [31] |

| pyiron | Integrated Platform | An integrated development environment for computational materials science. | Used to implement automated workflows for DFT parameter optimization and uncertainty quantification. [1] |

| ANN / RF / SVM | ML Model | Algorithms that learn the mapping between material descriptors and target properties from data. | The core engine for fast prediction. ANN was shown to be effective for predicting interface energies. [25] |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Tool | Analysis Script | Quantifies statistical and systematic errors in DFT calculations. | Critical for determining optimal DFT convergence parameters and understanding the precision of training data. [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "first-principles" mean in the context of computational materials science? In computational materials science, "first-principles" or ab initio calculations refer to methods that are derived directly from fundamental physical laws, without relying on empirical parameters or experimental data for fitting. These methods use only the atomic numbers of the involved atoms as input and are based on the established laws of quantum mechanics to predict material properties [32].

Q2: What are the primary first-principles methods used for predicting cathode properties?

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): This is the most widely used method for calculating structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of battery materials. It provides a good balance between accuracy and computational cost, making it suitable for high-throughput screening [33] [34] [35].

- Many-Body Perturbation Theory (GW method): This method is considered a gold standard for calculating accurate electronic band structures and optical properties. It addresses some inherent shortcomings of DFT but is significantly more computationally expensive [34].

Q3: My first-principles calculations predict a high-voltage cathode material, but the synthesized material shows poor cycling stability. What could be the cause? This common discrepancy often arises because standard DFT calculations typically predict ground-state properties and may not account for complex dynamic processes occurring during battery operation. Key factors to investigate include:

- Oxygen Redox Activity: In high-capacity, Li-rich layered oxides, oxygen can participate in the redox process, which may lead to oxygen loss and structural degradation upon cycling [33].

- Cation Migration: Transition metal ions (e.g., Mn) may migrate from the surface to the bulk or within the crystal lattice, leading to phase transformations and voltage fade [33].

- Interface Instability: The calculated bulk stability may not reflect the material's reactivity with the electrolyte at the interface. It is crucial to complement bulk studies with surface energy and interface stability calculations.

Q4: How can I efficiently converge key parameters in advanced calculations like GW? Developing robust and efficient workflows is essential. Best practices include:

- Automated Convergence: Implement automated workflows to systematically test convergence parameters, which can be more efficient than manual testing [34].

- Parameter Independence: Exploit the independence of certain convergence parameters. For example, some parameters in GW calculations can be converged simultaneously rather than sequentially, potentially offering significant speed-ups (e.g., a factor of 10 in computational time) [34].

- Simpler Models: Applying the principle of Occam's razor—using the simplest model that captures the essential physics—can often yield accurate results without unnecessary computational overhead [34].

Q5: How can machine learning be integrated with first-principles calculations for cathode design? Machine Learning (ML) can dramatically accelerate materials discovery by learning from computational or experimental data.

- Feature Identification: ML models can identify key descriptors that govern performance. For instance, in NASICON-type sodium-ion cathodes, entropy and equivalent electronegativity have been identified as critical features for energy density [36].

- High-Throughput Screening: ML models can be trained on data from first-principles calculations to rapidly predict properties of vast numbers of material compositions, guiding the synthesis of the most promising candidates, such as high-entropy compositions [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Computationally Predicted Voltage Does Not Match Experimental Measurements

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Exchange-Correlation Functional in DFT | Compare results from standard GGA-PBE with more advanced functionals (e.g., hybrid HSE06) or with GW calculations. | Use a functional known for better accuracy on your specific class of materials (e.g., one with a Hubbard U correction for transition metals) [35]. |

| Neglecting Entropic Contributions | The calculated voltage is primarily an enthalpic contribution at 0 K. | Check if your workflow correctly calculates the free energy, including vibrational entropic effects, especially for materials with soft phonon modes. |

| Overlooked Phase Transformations | Experimentally, the material may transform into a different phase upon cycling. | Calculate the voltage for all known polymorphic phases of the cathode material to identify the most stable phase at different states of charge [35]. |

Issue: Parameter Estimation for Electrochemical Models is Inefficient or Inaccurate

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Experimental Profile Selection | Profile may not excite all the dynamic behaviors of the battery. | Use a combination of operating profiles for parameter estimation. A study found that a mix of C/5, C/2, 1C, and DST profiles offered a good balance between voltage output error and parameter error [37]. |

| Overparameterization and Parameter Correlation | Different parameter sets yield similar voltage outputs. | Perform a sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential parameters. Use optimization algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which is robust for high-dimensional problems [37]. |

| High Computational Cost of High-Fidelity Models | Using the full P2D model for parameter estimation is slow. | Begin parameter estimation with a simpler model, like the Single Particle Model (SPM), to find a good initial guess for parameters before refining with a more complex model [37]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: High-Throughput First-Principles Screening of Multivalent Cathodes

This protocol is adapted from a systematic evaluation of spinel compounds for multivalent (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) batteries [35].

- Define the Composition Matrix: Select a host structure (e.g., spinel, AB₂O₄) and define the range of A-site (intercalating ion: Mg, Ca, Zn, etc.) and B-site (redox-active transition metal: Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) elements to screen.

- Calculate Key Properties: For each composition in the matrix, perform DFT+U calculations to determine:

- Average Voltage: Compute from the total energy difference between the charged and discharged states.

- Thermodynamic Stability: Assess by constructing the convex hull phase diagram to check if the compound is stable against decomposition into other phases.

- Ion Mobility: Calculate the activation barrier for ion diffusion using the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method.

- Evaluate and Rank: Rank materials based on a combination of properties: high voltage, high capacity, stability, and low diffusion barriers. The study identified Mn-based spinels for Mg and Ca as particularly promising [35].

Protocol 2: A Robust Workflow for GW Convergence

This protocol outlines an efficient workflow for converging GW calculations, which are crucial for obtaining accurate electronic band gaps [34].

- Initial DFT Calculation: Perform a standard DFT calculation to obtain a starting wavefunction and electron density.