Optimizing CRISPR Gene Editing Efficiency: From AI Design to Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing CRISPR gene editing efficiency.

Optimizing CRISPR Gene Editing Efficiency: From AI Design to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing CRISPR gene editing efficiency. It explores foundational AI-driven editor design, advanced methodological applications for therapeutic development, practical troubleshooting for common experimental challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks for assessing editing outcomes. Covering the latest advancements from 2025 research, the content synthesizes cutting-edge strategies including AI-generated editors like OpenCRISPR-1, novel delivery systems such as LNPs and VLPs, and cell-type specific optimization approaches to enhance both research and clinical applications.

The Next Generation: How AI and Novel CRISPR Systems Are Redefining Editing Efficiency

The integration of large language models (LLMs) into protein design represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach CRISPR gene editing optimization. By treating protein sequences as a specialized "language" with its own grammatical rules and semantic relationships, these AI systems can generate novel protein editors with enhanced properties. This technical support center addresses the practical challenges researchers face when implementing these cutting-edge tools in their CRISPR efficiency optimization work. The following guides and resources will help you troubleshoot common issues, understand key methodologies, and leverage the latest AI-powered platforms to advance your gene editing research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): AI-Driven Protein Design

FAQ 1: How can a language model possibly understand or design a protein? Proteins can be treated as a "language" where the 20 amino acids constitute an alphabet. Motifs and domains are analogous to words and sentences, with the entire sequence encoding structure and function, much like a sentence conveys meaning. LLMs trained on vast protein databases learn the complex "grammar" and "syntax" that dictate stable, functional protein folds, allowing them to generate novel, valid sequences [1].

FAQ 2: What are the key advantages of using AI like ProtET over traditional protein engineering methods? Traditional methods are often slow, labor-intensive, and rely on single-task models. AI platforms like ProtET introduce a flexible, controllable approach using simple text instructions (e.g., "increase thermostability"), allowing researchers to explicitly guide protein editing for specific functions without being limited to a single predefined task [2]. This dramatically accelerates the exploration of the vast combinatorial space of potential protein edits.

FAQ 3: My AI-designed Cas protein has low editing efficiency in primary human cells. What could be the issue? Editing efficiency in therapeutically relevant primary cells (like lymphocytes) is highly dependent on nuclear delivery. A key strategy is to optimize nuclear localization signals (NLS). Recent studies show that incorporating hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) sequences within the Cas9 backbone, rather than using terminally fused NLS, enhances nuclear import and can significantly boost editing efficiency in human primary T cells [3].

FAQ 4: How can I use AI to reduce the off-target effects of my CRISPR system? Off-target effects are often linked to the Cas enzyme's recognition of protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs). Machine learning platforms like PAMmla can predict the properties of millions of CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes, enabling the selection or design of variants with more precise PAM recognition. This customizability minimizes off-target editing and expands the range of targetable genomic sites [4].

FAQ 5: What does "text-guided design" mean in the context of a tool like ProtET? Text-guided design allows a researcher to provide natural language instructions to the AI model to direct protein edits. For example, you can input a command like "optimize the heavy chain complementarity-determining region (CDR) for increased antigen binding affinity." The model, trained on millions of protein-text pairs, interprets this instruction and generates the corresponding protein sequence modifications [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Knock-In Efficiency in Primary B Cells

Problem: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in efficiency is unacceptably low in primary human B cells, which are often quiescent and favor the error-prone NHEJ repair pathway over HDR [5].

Solutions:

- Optimize HDR Template Design: For short insertions (e.g., tags or point mutations), use single-stranded DNA donors with 30-60 nt homology arms. For larger insertions (e.g., fluorescent proteins), use double-stranded plasmid templates with 200-300 nt homology arms [5].

- Consider Strand Preference: If the edit is more than 5-10 bp from the Cas9 cut site, design your template for the targeting strand for PAM-proximal edits, and the non-targeting strand for PAM-distal edits [5].

- Utilize AI Design Tools: Use platforms like CRISPR-GPT to analyze your specific experimental goals, suggest optimal sgRNA targets, and predict potential off-target effects that could compromise efficiency [6].

Issue 2: Poor Stability or Expression of AI-Designed Protein

Problem: A novel protein editor generated by an AI model (e.g., a custom Cas variant) shows poor soluble expression or low stability in vivo.

Solutions:

- Employ Text-Guided Stabilization: Use a model like ProtET with text instructions focused on stability, such as "improve thermal stability" or "increase soluble expression yield." The model can then propose stabilizing mutations [2].

- Leverage Pre-Trained Models: Platforms like PAMmla are trained on scalable protein engineering data and can predict functional enzymes from a space of 64 million variants, helping you select a stable, well-behaved candidate from the outset [4].

Issue 3: High Off-Target Activity with Novel Editors

Problem: A newly designed nuclease shows high on-target activity but also unacceptably high levels of off-target editing.

Solutions:

- Select High-Fidelity Variants: Use machine learning-predicted Cas9 enzymes that are specifically tuned for enhanced precision. The PAMmla platform, for instance, can identify variants with stricter PAM recognition, a key factor in reducing off-target effects [4].

- Validate with AI Analysis: Before experimental validation, use tools like CRISPR-GPT to analyze your sgRNA design and predict the likelihood and location of potential off-target edits based on historical data [6].

Performance Data of AI Platforms for Protein Design

Table 1: Comparison of Key AI Platforms for Protein and CRISPR Editor Design

| Platform Name | Primary Function | Key Input | Reported Outcome/Advantage | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtET | Controllable protein editing | Natural language instructions (e.g., "increase stability") | 16.67-16.90% improvement in stability; optimized antibody binding | [2] |

| PAMmla | Cas9 enzyme property prediction | Scalable sequence data | Predicts properties of 64 million Cas9 variants for precise editing | [4] |

| CRISPR-GPT | Gene-editing experiment planning | Experimental goals & gene sequences | Automates experimental design; enables successful first-attempt edits by novices | [6] |

| hiNLS Cas9 | Enhanced nuclear delivery | Cas9 sequence with internal NLS motifs | Improved editing efficiency in primary human T cells | [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing hiNLS Cas9 for Enhanced Editing in Primary Cells

This protocol is adapted from strategies shown to enhance CRISPR editing efficiency in therapeutically relevant primary human lymphocytes [3].

- Vector Construction: Engineer your Cas9 expression vector to incorporate hairpin internal nuclear localization signal (hiNLS) sequences at selected sites within the Cas9 backbone, as opposed to the traditional terminally-fused NLS.

- Protein Production: Express and purify the hiNLS-Cas9 protein. Studies indicate these constructs can be produced with high purity and yield, supporting manufacturing scalability.

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Complex the purified hiNLS-Cas9 protein with your target-specific sgRNA to form RNP complexes.

- Cell Delivery: Deliver the RNP complexes into primary human T cells or other target cells via electroporation. The hiNLS design facilitates rapid nuclear import, which is critical for high efficiency when using transient RNP delivery.

- Validation: Assess editing efficiency at the target locus (e.g., B2M or TRAC) using next-generation sequencing or T7E1 assay. Compare against a terminal-NLS control.

Protocol 2: Using Text-Guided AI for Protein Optimization

This protocol outlines the workflow for using a tool like ProtET to optimize a protein of interest [2].

- Define Goal: Formulate a clear, text-based instruction that defines the desired functional outcome. Example: "Enhance the catalytic activity of [Your Enzyme] for substrate [X]."

- Input Sequence: Provide the AI model (ProtET) with the wild-type amino acid sequence of your target protein.

- Generate Variants: Run the model with your text instruction to receive a set of proposed protein sequence variants.

- Synthesize and Clone: Synthesize the genes encoding the top AI-predicted variants and clone them into an appropriate expression vector.

- Experimental Testing: Express and purify the variant proteins. Test them in relevant functional assays (e.g., enzyme activity assays, thermal shift assays for stability, or SPR for binding affinity).

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

AI-Driven Protein Editor Design Workflow

Troubleshooting Low Knock-In Efficiency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Powered CRISPR Editor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| hiNLS-Cas9 Constructs | Cas9 variants with internal nuclear localization signals for enhanced nuclear import and editing efficiency in primary cells. | Boosting knock-in efficiency in hard-to-transfect primary human T or B cells for immunotherapy research [3]. |

| Machine Learning-Predicted Cas Variants | Novel Cas enzymes (e.g., from PAMmla) designed for reduced off-target effects or altered PAM recognition. | Performing highly precise edits in genotherapeutic applications where safety is paramount [4]. |

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) HDR Donor | Short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides with 30-60 nt homology arms, used as a repair template for introducing small edits. | Introducing point mutations or small tags (e.g., FLAG, HIS) into a specific genomic locus [5]. |

| Plasmid HDR Donor Templates | Double-stranded DNA plasmids containing the insert (e.g., fluorescent protein) flanked by long homology arms (200-300 nt). | Inserting larger genetic elements, such as reporter genes or degron tags, into the genome [5]. |

| AI-Generated Protein Variants | Novel protein sequences generated by platforms like ProtET, optimized for specific properties like stability or binding. | Rapidly engineering improved enzymes, therapeutic antibodies, or stabilized CRISPR editors without extensive manual screening [2]. |

| CRISPR-GPT Analysis Report | An AI-generated plan suggesting sgRNA designs, potential pitfalls, and troubleshooting advice for a gene-editing experiment. | Guiding novice researchers or optimizing complex experimental designs to save time and resources [6]. |

FAQs: Novel Cas Proteins and Systems

Q1: Why is the discovery of novel Cas proteins important for therapeutic development? The discovery of novel Cas proteins is crucial because different Cas variants have unique properties that can overcome limitations of the commonly used SpCas9. For instance, some newly identified Cas proteins are smaller in size. This smaller size is vital for packaging the entire CRISPR system into delivery vehicles with limited capacity, such as Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs), which are commonly used for in vivo gene therapy. Furthermore, novel Cas proteins often recognize different Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequences, expanding the range of DNA sites that can be targeted within the genome for editing [7] [8].

Q2: What are the main challenges when working with a newly discovered Cas protein in the lab? The primary challenges involve characterization and optimization. Researchers must first thoroughly characterize the new protein's properties, including its specific PAM requirement, on-target editing efficiency, and potential for off-target effects. Subsequently, the entire system—including the guide RNA and delivery method—often needs to be re-optimized for the new nuclease to function effectively in the target cell type. This process can be time-consuming and requires careful experimental validation [9] [10].

Q3: How do base editors and prime editors differ from traditional Cas nucleases? Traditional Cas nucleases, like Cas9, create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which rely on the cell's repair mechanisms and can lead to unpredictable insertions or deletions (indels). In contrast, base editors use a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease fused to a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one base into another (e.g., C to T or A to G) without creating a DSB. Prime editors are even more versatile, using a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site based on a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) template, also without requiring a DSB. These systems offer greater precision and reduce unwanted editing byproducts [10] [11].

Q4: What delivery methods are most promising for CRISPR therapies using novel systems? Delivery remains a central challenge. While viral vectors like AAVs are efficient, they can trigger immune responses and have limited packaging capacity. Non-viral methods are increasingly promising:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Effectively deliver CRISPR components as RNA or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. They are particularly good for targeting liver cells and allow for potential re-dosing, as seen in recent clinical trials [7] [12] [13].

- Electroporation: Highly effective for ex vivo editing of hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells and hematopoietic stem cells [7].

- Novel Nanostructures: Emerging systems, like lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acids (LNP-SNAs), have shown in lab studies to boost cell uptake and gene-editing efficiency while reducing toxicity compared to standard LNPs [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues with Novel Cas Proteins

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | Non-optimal guide RNA (gRNA) design for the new Cas protein. | Redesign gRNAs using tools specific to the Cas variant, ensuring target specificity and avoiding secondary structures [9]. |

| Inefficient delivery of CRISPR components into target cells. | Optimize delivery method (e.g., electroporation parameters, LNP formulation). Use a reporter system to confirm successful delivery [7] [9]. | |

| Low expression or activity of the novel Cas protein in the host cell. | Verify protein expression with a Western blot. Use a codon-optimized sequence for your host organism and confirm promoter compatibility [9]. | |

| High Off-Target Effects | The novel Cas protein may have lower intrinsic fidelity. | Utilize computational tools to predict and scan for potential off-target sites. Consider using high-fidelity engineered versions of the nuclease if available [9] [10]. |

| gRNA sequence has high similarity to other genomic regions. | Design gRNAs with maximal on-target and minimal off-target homology. Perform deep sequencing to comprehensively assess off-target activity [14] [9]. | |

| High Cell Toxicity | Overexpression of the CRISPR components is stressful to cells. | Titrate the amount of Cas/gRNA delivered; use lower, more effective doses. For novel Cas proteins, delivering pre-assembled RNP complexes can reduce the duration of nuclease activity and lower toxicity [7] [9]. |

| The delivery method itself (e.g., electroporation) is causing stress. | Optimize delivery parameters to improve cell viability post-transfection. For electroporation, adjust voltage and pulse length [7]. | |

| Failure to Knock-in Gene | The DNA repair pathway (HDR) is inefficient in your cell type. | Use HDR-enhancing reagents and deliver CRISPR during the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle (e.g., by cell cycle synchronization). For large insertions, consider using advanced systems like retron-based editing [7] [15]. |

| The donor DNA template is not co-localizing with the cut site. | Use methods that facilitate co-delivery, such as electroporation of RNP with a single-stranded DNA (ssODN) donor or the use of virus-like particles (VLPs) [7] [8]. |

Table 2: Advanced Troubleshooting: Scaling Up and Validation

| Challenge | Consideration & Strategy |

|---|---|

| Multiplexed Editing | Delivering multiple gRNAs simultaneously increases payload size and complexity. Lentiviral vectors or electroporation are suitable methods. Carefully assess potential synergistic toxicity or off-target effects when targeting multiple loci [7]. |

| In Vivo Validation | Efficient delivery to the target tissue is the major hurdle. Select delivery vectors (e.g., LNPs, AAVs) with known tropism for your organ of interest. New systems like LNP-SNAs aim to improve tissue targeting [13]. Always include controls to distinguish between editing efficiency and delivery efficiency. |

| Detection of Precise Edits | Standard genotyping methods may not detect precise base changes or small insertions. Use a combination of methods: T7E1 or Surveyor assays for initial cleavage detection, followed by Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) for precise characterization of the edits [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Characterization of a Novel Cas Protein's PAM Requirement

Objective: To empirically determine the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence essential for the novel Cas nuclease to recognize and cleave DNA.

Materials:

- Plasmid library containing a randomized PAM sequence adjacent to a constant target site.

- The novel Cas nuclease and its associated guide RNA (gRNA) expression constructs.

- A suitable host cell line (e.g., HEK293T for high transfection efficiency).

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) capabilities.

Methodology:

- Library Delivery: Co-transfect the PAM library and the CRISPR constructs (Cas + gRNA) into the host cells.

- Selection Pressure: After 48-72 hours, harvest the plasmid DNA from the cells. The functional cleavage by the Cas nuclease will destroy plasmids with non-permissive PAMs, enriching for plasmids with functional PAM sequences.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Amplify the region containing the randomized PAM from the harvested plasmid pool and subject it to NGS. Compare the sequence reads before and after selection to identify the PAM sequences that have been enriched, revealing the required PAM motif [10].

Protocol 2: Assessing Editing Efficiency and Specificity

Objective: To quantify the on-target efficiency and profile the off-target activity of a novel CRISPR system.

Materials:

- Target cells.

- Validated gRNA for your target locus.

- Optimized method for delivering the novel CRISPR system (e.g., RNP via electroporation).

- T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor Mutation Detection Kit.

- PCR reagents and NGS platform.

Methodology:

- Delivery and Culture: Deliver the CRISPR components to the target cells and culture for several days to allow editing and repair.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest genomic DNA from the edited cell population.

- On-Target Efficiency Analysis:

- PCR: Amplify the genomic region surrounding the target site.

- T7E1/Surveyor Assay: Digest the PCR amplicon with the mismatch-sensitive enzyme. Cleaved bands on a gel indicate successful editing. The intensity of the bands can be used for a rough efficiency estimate.

- NGS (Gold Standard): Amplify the target region and perform NGS. This provides a quantitative measure of the percentage of alleles containing insertions, deletions, or precise edits [9].

- Off-Target Analysis:

Research Workflow and Pathways

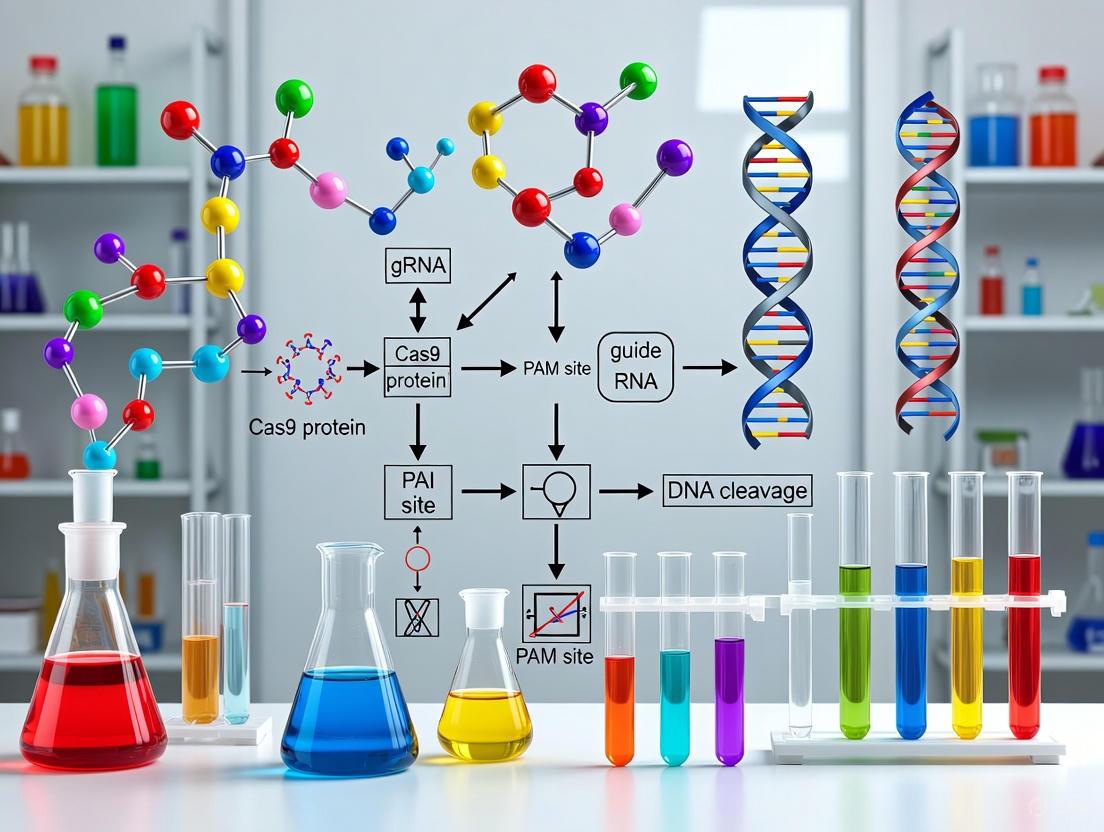

Diagram 1: Novel Cas Protein Characterization Workflow

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing and Repair Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Working with Novel Cas Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Cas Expression Vector | Ensures high-level expression of the novel Cas protein in the target host organism (e.g., human cells). |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Expression Constructs | Delivers the targeting RNA component; can be on a separate plasmid or in an all-in-one vector with the Cas gene [7]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA or crRNA/tracrRNA | Chemically synthesized guide RNAs offer high purity and reduced immune activation in therapeutic contexts; can be complexed with Cas protein to form RNP complexes [7] [13]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A non-viral delivery vehicle for in vivo delivery of CRISPR mRNA, sgRNA, or donor templates. Particularly effective for liver targets [12] [13]. |

| Electroporation System | A physical delivery method highly effective for ex vivo editing of hard-to-transfect primary cells (e.g., T cells, stem cells) with RNPs [7]. |

| NGS Mutation Detection Kit | Provides the reagents for preparing sequencing libraries to accurately quantify on-target and off-target editing frequencies. |

| HDR Donor Template (ssODN/dsDNA) | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for small edits; double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) for larger insertions. Critical for precise gene correction or knock-in [7] [15]. |

| Cell Type-Specific Culture Media | Essential for maintaining the viability and function of sensitive primary cells during and after the CRISPR editing process. |

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with CRISPR gene editing represents a transformative advancement in biotechnology, enabling researchers to move beyond naturally derived systems to computationally designed editors with enhanced properties. AlphaFold, DeepMind's revolutionary protein structure prediction network, has emerged as a pivotal tool in this paradigm shift. By accurately predicting three-dimensional protein structures from amino acid sequences, AlphaFold provides critical structural insights that accelerate the rational optimization of gene editing tools [16] [17]. This technical support resource examines how structural biology powered by AlphaFold is addressing fundamental challenges in CRISPR editor efficiency, specificity, and functionality, providing researchers with practical methodologies to enhance their experimental outcomes.

The optimization of CRISPR systems has traditionally relied on iterative experimental screening—a time-consuming and often unpredictable process. AlphaFold circumvents these limitations by enabling computational structural analysis of CRISPR complexes before experimental validation. Research demonstrates that AlphaFold predictions achieve accuracy "competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases," providing reliable structural models for rational design [16]. This capability is particularly valuable for characterizing CRISPR-Cas proteins with unresolved experimental structures, such as PspCas13b, where AlphaFold predictions with high per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT) have enabled the identification of functional domains and strategic splitting sites for engineered editor systems [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can AlphaFold improve gRNA design for CRISPR systems? AlphaFold structural predictions enable rational guide RNA optimization by modeling the molecular interactions between Cas proteins and their RNA guides. For instance, with the compact CRISPR/Cas12f1 system, AlphaFold 3 simulations revealed suboptimal intramolecular pairing within the tracrRNA component that disrupted its interaction with crRNA. Researchers used these structural insights to strategically truncate the 3' end of tracrRNA, eliminating disruptive pairing and significantly enhancing trans-cleavage activity. Subsequent design of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) further improved system performance, demonstrating how AlphaFold-driven structural analysis can optimize nucleic acid components for enhanced editor function [19].

Q2: Can AlphaFold predict structures for novel, AI-designed CRISPR proteins? Yes, AlphaFold can reliably fold artificially generated CRISPR proteins that diverge significantly from natural sequences. In a landmark study, researchers used large language models to generate millions of novel CRISPR-Cas sequences, with generated Cas9-like proteins averaging only 56.8% sequence identity to any natural counterpart. Despite this divergence, AlphaFold2 confidently predicted structures for 81.65% of these AI-generated proteins (mean pLDDT > 80), enabling computational validation of structural integrity before experimental testing. This capability provides a crucial bridge between AI-based protein generation and functional implementation [20].

Q3: How accurate are AlphaFold predictions for CRISPR protein engineering? Validation studies demonstrate exceptional accuracy for AlphaFold in predicting structures of CRISPR-related proteins. In comprehensive assessments against experimentally determined structures, AlphaFold achieved median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD95 (approximately the width of a carbon atom) [16]. For anti-CRISPR proteins—small proteins used to inhibit CRISPR-Cas systems—AlphaFold2 predictions showed no significant difference in accuracy compared to its performance in the CASP14 assessment, with TM-scores indicating highly reliable structural models [21]. This precision enables confident use of predictions for rational engineering decisions.

Q4: What are the limitations of using AlphaFold for editor optimization? While transformative, AlphaFold has specific limitations. It may not fully capture conformational changes induced by crRNA binding or target DNA/RNA recognition [18]. Additionally, although AlphaFold can be inverted for de novo protein design, initial designs often require optimization of surface properties, as early trials produced designs with hydrophobic surface patches uncharacteristic of natural proteins [22]. For optimal results, researchers should complement AlphaFold predictions with experimental validation and molecular dynamics simulations where conformational flexibility is functionally important.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Low Editing Efficiency with Novel Cas Variants

Problem: AI-designed Cas proteins exhibit poor editing activity in cellular environments despite proper expression.

Solution: Utilize AlphaFold to analyze structural completeness and active site conservation.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Generate structural models of your novel Cas variant using AlphaFold (via ColabFold or local installation) [16] [17].

- Compare the predicted structure to well-characterized natural Cas proteins (e.g., SpCas9), focusing on:

- Conservation of catalytic residues (RuvC, HNH for Cas9)

- Structural integrity of guide RNA binding regions

- Proper formation of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) interaction sites

- Identify structural deviations that might impair function, such as:

- Misfolded catalytic domains

- Obstructed substrate binding channels

- Incomplete formation of key structural motifs

- Implement structure-guided repairs by reverting non-functional mutations back to conserved residues while maintaining novel beneficial substitutions.

- Validate computationally by re-predicting the structure of repaired variants before experimental testing.

Table: Critical Functional Domains to Verify in AI-Designed Cas Proteins

| CRISPR System | Essential Functional Domains | Key Structural Features to Verify |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9-like | RuvC, HNH, REC lobe, PAM-interacting | Catalytic residue geometry, DNA/RNA binding cleft formation |

| Cas12-like | RuvC, OBD, Nuc | Electrostatic surface for DNA engagement, cleavage site accessibility |

| Cas13-like | HEPN domains, guide RNA binding region | Conserved catalytic arginines, nucleotide binding pockets |

Challenge: Engineering Inducible CRISPR Systems

Problem: Achieving precise temporal control over CRISPR activity through split protein systems.

Solution: Use AlphaFold to identify optimal split sites that minimize background activity while maintaining inducibility.

Step-by-Step Protocol (Based on paCas13 Development):

- Obtain a high-confidence structural model of your target Cas protein using AlphaFold with multiple recycling steps (3-5 cycles) to refine model quality [18].

- Identify candidate split sites in solvent-accessible loop regions using these criteria:

- Located away from catalytic centers and substrate binding interfaces

- Positioned in flexible linkers between structured domains

- Avoid terminal HEPN domains for Cas13 systems

- Generate structural models of split fragments to assess:

- Residual interface compatibility using MaSIF-site or similar tools

- Electrostatic complementarity of fragment surfaces

- Potential for spontaneous reconstitution (high in split sites N550/C551, N624/C625 for PspCas13b)

- Select split sites with moderate interface areas that require dimerization domains for stable association (e.g., N351/C352 for PspCas13b).

- Validate fragment structures individually and in complex with dimerization domains to ensure proper folding when reconstituted.

Diagram: Workflow for Identifying Optimal Split Sites in Cas Proteins

Challenge: Optimizing Base Editor Efficiency

Problem: Low editing efficiency in base editor systems due to suboptimal spatial arrangement of catalytic domains.

Solution: Use AlphaFold to model the spatial relationship between deactivated Cas domains and effector proteins.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Construct a structural model of your base editor complex, including:

- Deactivated Cas protein (dCas9, dCas13, etc.)

- Tethered effector domain (deaminase, acetyltransferase, etc.)

- Appropriate linker sequences between domains

- Analyze the spatial orientation of the catalytic site relative to the target nucleotide:

- Measure distances between catalytic residues and target base

- Identify potential steric clashes with Cas protein backbone

- Assess flexibility and accessibility of the target region

- Systematically vary linker length and composition, re-predicting structures for each variant.

- Select configurations that position catalytic residues within optimal range of the target base (typically 5-15Å).

- Validate top candidates through molecular dynamics simulations if possible, then experimental testing.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational and Experimental Resources for AlphaFold-Guided Editor Optimization

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Application in Editor Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold 3, ColabFold | Protein-RNA complex modeling, guide RNA optimization, split system design [19] [16] |

| Structure Analysis | MaSIF-site, PyMOL, ChimeraX | Interface analysis, electrostatic potential mapping, conformational assessment [18] |

| Sequence Generation | ProGen2, CRISPR-Cas Atlas | Generating novel Cas variants with expanded diversity [20] |

| Validation Metrics | pLDDT, predicted TM-score, RMSD | Assessing prediction reliability, model quality assurance [16] [20] |

| Experimental Testing | Dual-luciferase assays, mammalian cell editing screens | Functional validation of designed editors [18] |

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

De Novo Design of CRISPR Proteins

Beyond optimizing natural systems, AlphaFold enables the computational design of entirely novel CRISPR proteins. By inverting the AlphaFold network, researchers can generate sequences that fold into desired structures, though this approach may require optimization of surface properties [22]. The integration of large language models trained on CRISPR protein diversity has dramatically expanded this capability, generating Cas9-like effectors with 10.3-fold increased phylogenetic diversity compared to natural sequences [20].

Protocol for Assessing Novel CRISPR Protein Folds:

- Generate novel protein sequences using CRISPR-specific language models (e.g., ProGen2 fine-tuned on CRISPR-Cas Atlas) [20].

- Predict structures of generated sequences using AlphaFold2.

- Evaluate structural quality using confidence metrics (pLDDT, predicted TM-score).

- Verify conservation of key functional motifs despite sequence divergence.

- Select candidates with both high confidence scores and novel structural features for experimental characterization.

Leveraging Natural Anti-CRISPR Mechanisms

AlphaFold structural predictions have revealed remarkable diversity in anti-CRISPR proteins, providing insights into inhibition mechanisms that can inform editor optimization [21]. These natural inhibitory proteins employ diverse strategies, including direct Cas protein binding, active site occlusion, and even enzymatic modification of Cas complexes.

Protocol for Analyzing Anti-CRISPR Mechanisms:

- Acquire anti-CRISPR datasets from viral and prokaryotic genomes [21].

- Predict 3D structures using AlphaFold2 with high confidence (plDDT > 70 recommended).

- Classify inhibition mechanisms through structural analysis:

- Competitive binding to DNA/RNA interaction sites

- Allosteric inhibition through conformational stabilization

- Enzymatic inactivation (e.g., acetylation of active sites)

- Apply insights to engineer regulatable Cas systems or enhance specificity through inhibitory domain incorporation.

Diagram: From Anti-CRISPR Mechanisms to Editor Applications

Quantitative Assessment Framework

Table: Key Metrics for Evaluating AlphaFold-Guided Editor Optimization

| Performance Dimension | Evaluation Metrics | Benchmark Values |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy | TM-score, RMSD, plDDT | TM-score > 0.8 (high confidence), Backbone accuracy ~0.96Å [16] |

| Editor Efficiency | Editing rate, Specificity index | Comparable or improved vs. SpCas9 baseline [20] |

| Novelty | Sequence identity to natural proteins, Phylogenetic diversity | 40-60% identity to nearest natural protein [20] |

| Functional Success | Experimental success rate, Melting temperature | 7/39 de novo designs folded with high Tm [22] |

| Process Acceleration | Design-to-validation timeline | Weeks vs. months for traditional engineering [23] |

This technical support resource demonstrates how AlphaFold-driven structural biology provides a powerful framework for addressing persistent challenges in CRISPR editor optimization. By integrating these computational methodologies into their research pipeline, scientists can accelerate the development of next-generation genome editing tools with enhanced precision, functionality, and therapeutic potential.

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, with Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) serving as the foundational enzyme for countless applications. However, inherent limitations of wild-type SpCas9, including off-target effects, strict Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) requirements, and occasional low editing efficiency, have driven the development of enhanced variants and orthologs. This technical resource center provides a comprehensive guide to these advanced tools, offering researchers detailed protocols, troubleshooting advice, and reagent solutions to optimize genome editing efficiency.

FAQs: Selecting High-Efficiency CRISPR Systems

1. What are the primary advantages of using high-fidelity Cas9 variants over wild-type SpCas9? High-fidelity Cas9 variants are engineered to drastically reduce off-target editing while maintaining robust on-target activity. Wild-type SpCas9 can tolerate mismatches between the guide RNA and target DNA, leading to unintended genomic modifications. Variants like eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9, and evoCas9 incorporate mutations that disrupt non-specific interactions with the DNA backbone or enhance the enzyme's proofreading capability, thereby increasing its discrimination against off-target sites [24]. For example, the Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 nuclease dramatically reduces off-target effects compared to the wild-type enzyme [25].

2. Which Cas enzymes should I consider for targeting genomic regions lacking an NGG PAM sequence? The requirement for an NGG PAM sequence adjacent to the target site can be a significant limitation. Fortunately, several engineered Cas variants and natural orthologs with altered PAM compatibilities are now available:

- xCas9: Recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs, and also offers increased fidelity [24].

- SpCas9-NG: Engineered to recognize NG PAMs, increasing the number of potential target sites in the genome [24].

- SpG: A variant that recognizes NGN PAMs, offering broader targeting range [24].

- SpRY: A nearly PAM-less variant that recognizes NRN (preferring NGG) and NYN (preferning NGT) PAMs, providing exceptional flexibility [24].

- SaCas9: A Staphylococcus aureus-derived Cas9 that is smaller than SpCas9 and recognizes the NNGRRT PAM [25].

- CjCas9: A compact Cas9 from Campylobacter jejuni with a NNNNACAC PAM requirement [25].

3. Are there fully novel Cas proteins not found in nature? Yes, generative artificial intelligence is now being used to design novel CRISPR-Cas proteins. A prime example is OpenCRISPR-1, a Cas9-like protein designed by Profluent Bio using large language models. OpenCRISPR-1 is reported to have comparable on-target efficiency to SpCas9 while demonstrating a 95% reduction in off-target editing across multiple genomic sites. It is composed of 1,380 amino acids and contains 403 mutations compared to SpCas9, making it a truly AI-generated editor [26].

4. How does Cas12a differ from Cas9, and when should I use it? Cas12a (formerly known as Cpf1) is a distinct type of CRISPR system with several unique features that make it suitable for specific applications [27]:

- PAM Sequence: It recognizes a T-rich PAM (TTTV for Cas12a V3, TTTN for Cas12a Ultra), which is located 5' of the target site.

- Cleavage Mechanism: It creates staggered ends (offsets) in the target DNA, as opposed to the blunt ends created by Cas9. This can be beneficial for certain cloning strategies and may improve Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) efficiency.

- crRNA Processing: Cas12a processes its own guide RNA arrays, which can simplify multiplexing strategies where multiple genes are targeted simultaneously. The Alt-R Cas12a Ultra nuclease has higher on-target potency and a broader TTTN PAM recognition, increasing its target range [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low On-Target Editing Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Suboptimal guide RNA (gRNA) design.

- Solution: Ensure your gRNA has sufficient GC content. A study in grapevine found that editing efficiency increased proportionally with sgRNA GC content, with 65% GC content yielding the highest efficiency [28]. Use established online tools to select a gRNA with high predicted efficiency and minimal off-targets. Also, verify that the gRNA is expressed correctly in your system.

Cause 2: Persistent non-selective DNA binding by the Cas nuclease.

- Solution: Recent research indicates that reduced PAM specificity can lead to the Cas enzyme becoming stuck on non-target DNA, failing to engage the correct target sequence. If using a PAM-flexible variant like SpRY, consider switching to a more specific enzyme like a high-fidelity SpCas9 for targets with standard NGG PAMs [29].

Cause 3: Low expression or activity of the Cas protein in your cell type.

- Solution: Optimize the codon usage of the Cas gene for your target organism. Use a strong, cell-type-specific promoter to drive Cas expression. Validate protein expression using western blotting. For difficult-to-transfect cells, enriching for transfected cells via antibiotic selection or FACS sorting can improve results [30].

Problem: High Off-Target Editing

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Use of wild-type SpCas9 with a gRNA that has high sequence homology elsewhere in the genome.

- Solution: The most direct solution is to switch to a high-fidelity Cas9 variant such as eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9 [24]. These mutants are designed to be less tolerant of gRNA-DNA mismatches. Alternatively, use the Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) system, which requires two adjacent gRNAs to create a double-strand break, dramatically increasing specificity [24].

Cause 2: High, prolonged expression of Cas9 and gRNA.

- Solution: Utilize transient expression systems, such as delivering the CRISPR machinery as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. RNP delivery leads to rapid degradation and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid-based expression [31]. Employ self-inactivating vectors or inducible promoters to limit the duration of Cas9 activity.

Cause 3: Inadequate assessment of off-target sites.

- Solution: Move beyond biased computational prediction. Employ genome-wide, unbiased off-target detection methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq to get a comprehensive profile of nuclease activity [31]. This provides a more accurate picture of specificity.

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Engineered SpCas9 Variants for Enhanced Specificity and Altered PAM Recognition

| Variant Name | Key Feature | Mechanism | PAM Sequence | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) [24] | High-fidelity | Weakened non-target strand binding to reduce off-target cleavage. | NGG | Experiments requiring maximal on-target accuracy. |

| SpCas9-HF1 [24] | High-fidelity | Disrupted interactions with DNA phosphate backbone. | NGG | General high-specificity applications. |

| HypaCas9 [24] | High-fidelity | Enhanced proofreading and discrimination between on- and off-targets. | NGG | Sensitive genetic screens and therapeutic development. |

| xCas9 [24] | PAM-flexible & High-fidelity | Mutations in multiple domains to alter PAM recognition. | NG, GAA, GAT | Targeting regions with limited NGG sites, needing higher fidelity. |

| SpCas9-NG [24] | PAM-flexible | Engineered PAM-interacting domain. | NG | Significantly expands the targetable genome space. |

| SpRY [24] | Near PAM-less | Greatly relaxed PAM requirement. | NRN > NYN | Targeting genomic regions with no canonical PAM sequences. |

Table 2: Diverse Cas Nucleases and Their Properties

| Cas Nuclease | Origin | Size (aa) | PAM Sequence (5'—3') | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 [25] | Streptococcus pyogenes | 1,368 | NGG | The gold standard; well-characterized but has size and PAM limitations. |

| SaCas9 [25] | Staphylococcus aureus | 1,053 | NNGRRT | Smaller size beneficial for viral vector packaging (e.g., AAV). |

| CjCas9 [25] | Campylobacter jejuni | ~984 | NNNNACAC | Very compact; useful for delivery where size is a constraint. |

| AsCas12a [25] | Acidaminococcus sp. | 1,307 | TTTN | Creates staggered cuts; self-processes crRNAs; T-rich PAM. |

| LbCas12a [25] | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | 1,228 | TTTN | Similar to AsCas12a; another well-characterized Cas12a ortholog. |

| AsCas12f1 [25] | Acidaminococcus sp. | ~400-700 | NTTR | An ultra-compact nuclease, enabling new delivery options. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Editing Efficiency

Protocol 1: Validating On-Target Editing Using T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing CRISPR in grapevine suspension cells [28].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest transfected cells and extract genomic DNA using a standard CTAB method or commercial kit.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking your target site (amplicon size 400-800 bp). Perform PCR using a high-fidelity polymerase to amplify the target region from the genomic DNA.

- DNA Denaturation and Reannealing: Purify the PCR products and quantify. Take 200-400 ng of the purified PCR product in a suitable buffer. Denature the DNA by heating to 95°C for 5-10 minutes, then slowly reanneal by ramping the temperature down to 25°C (e.g., -0.1°C/sec). This process allows the formation of heteroduplex DNA if indels are present.

- T7EI Digestion: Add T7EI enzyme to the reannealed DNA and incubate at 37°C for 15-60 minutes. The T7EI enzyme cleaves DNA at mismatches in heteroduplex molecules.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Run the digested products on a 2-3% agarose gel. Cleaved bands indicate successful editing.

- Efficiency Calculation: Use gel imaging software to quantify the band intensities.

- Editing Efficiency (%) = [1 - √(1 - (b+c)/(a+b+c))] × 100

- Where

ais the intensity of the undigested PCR product band, andbandcare the intensities of the cleaved bands.

Protocol 2: Determining Specificity Using GUIDE-seq

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing) is an unbiased method for detecting off-target sites genome-wide [31].

- dsODN Transfection: Co-transfect your cells with the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid(s) and a double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Shearing: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA and shear it to an average fragment size of 500 bp.

- Library Preparation and Enrichment:

- Blunt-end Repair & A-tailing: Prepare the sheared DNA for adapter ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate sequencing adapters to the DNA fragments.

- dsODN Enrichment: Perform PCR to enrich for fragments that have incorporated the dsODN tag.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the resulting library on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to the reference genome. Cluster reads that have the dsODN tag integrated and identify genomic locations with significant tag integration sites, which correspond to Cas9 cleavage events (both on-target and off-target).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for High-Efficiency CRISPR Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Reduces off-target effects while maintaining on-target cleavage. | SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9(1.1), Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 [24] [25]. |

| PAM-Flexible Cas Variants | Enables targeting of genomic sites lacking canonical NGG PAMs. | xCas9, SpCas9-NG, SpRY [24]. |

| Cas Orthologs | Provides alternative PAMs and smaller sizes for delivery. | SaCas9, CjCas9, AsCas12a [25]. |

| AI-Designed Editors | Novel proteins with potentially optimized properties not found in nature. | OpenCRISPR-1 (publicly available sequence) [26]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | For transient, high-efficiency delivery with reduced off-target activity. | Complex of purified Cas protein and synthetic gRNA. |

| Unbiased Off-Target Detection Kits | For genome-wide identification of CRISPR-induced DSBs. | GUIDE-seq [31] & Digenome-seq [31] reagent kits. |

| HDR Donor Templates | For precise gene insertion or correction when using HDR repair. | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) or double-stranded DNA donors. |

Workflow Visualization: Selecting a High-Efficiency Cas Nuclease

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate Cas nuclease for your experiment, based on the primary experimental requirement.

Precision in Practice: Advanced Delivery Systems and Editing Platforms for Therapeutic Development

The therapeutic application of CRISPR gene editing hinges on the safe and efficient delivery of its molecular components—most commonly the Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA)—into the nucleus of target cells [32]. While the ex vivo delivery of CRISPR into cells in a culture dish is relatively straightforward, the in vivo delivery required to treat most genetic diseases presents a major challenge [33]. The delivery vehicle must protect the CRISPR machinery from degradation, navigate to the correct tissue, cross cell membranes, and release its payload effectively [32]. No single delivery modality is ideal for every application; each offers a distinct set of advantages and trade-offs concerning immunogenicity, editing duration, cargo capacity, and manufacturing scalability [32] [34].

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting and optimizing a CRISPR delivery system for therapeutic in vivo use.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for in vivo CRISPR delivery.

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Systems

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the three primary delivery modalities to guide initial selection.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CRISPR Delivery Systems

| Feature | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV) | Virus-like Particles (VLPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cargo | mRNA, RNP [34] | DNA [32] | Proteins, RNPs [35] [36] |

| Immunogenicity | Low; suitable for repeated dosing [34] | High; pre-existing immunity can limit efficacy [32] [34] | Moderate; lacks viral genetic material, improving safety [36] |

| Editing Duration | Transient (days) [34] | Long-term or permanent [34] | Transient (days) [35] |

| Cargo Capacity | Moderate to High [34] | Low (packaging limit ~4.7 kb) [32] | Moderate (can deliver large proteins like Cas9) [36] |

| Manufacturing & Scalability | Highly scalable [34] | Complex and costly [34] | Complexity depends on the platform [36] |

| Primary Applications | mRNA vaccines, short-term therapies, systemic delivery [34] | Long-term gene expression for genetic disorders [34] | Transient delivery of gene-editing RNPs; combines advantages of viral and non-viral systems [35] [32] |

Troubleshooting Common Delivery Problems

FAQ: Low Editing Efficiency

Q: Despite successful cellular transduction, my CRISPR editing efficiency remains low. What are the potential causes and solutions?

- A1: Inefficient Nuclear Import: The Cas protein may not be efficiently entering the nucleus.

- Solution: Optimize nuclear localization signals (NLS). Recent research demonstrates that using hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) sequences inserted directly into the Cas9 backbone, rather than relying solely on terminally fused NLS, can significantly enhance nuclear import and editing efficiency in primary human cells, such as T lymphocytes [3].

- A2: Cargo Mismatch or Instability:

- Solution: Match the cargo to the vector's strengths. For LNP delivery, mRNA is often more effective than plasmid DNA. For VLP delivery, ensure the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is properly packaged and released. Directed evolution of VLP capsids has been used to create variants (e.g., v5 eVLP) with improved RNP packaging and post-delivery release, resulting in 2-4x higher delivery efficiency [35].

- A3: Off-target Vector Tropism: The delivery vector may not be efficiently reaching or entering your target cell type.

- Solution: Re-engineer vector targeting. For viral vectors and VLPs, this can involve engineering the envelope proteins or capsids for specific tissue tropism [36] [32]. For LNPs, the lipid composition and surface functionalization (e.g., with antibodies or peptides) can be modified to enhance target cell specificity [34].

FAQ: Cytotoxicity and Immune Response

Q: My delivery vector is causing significant cell death or triggering an immune response. How can I mitigate this?

- A1: Vector-Induced Toxicity:

- For LNPs: The lipid composition can be cytotoxic. Optimize the ratios of ionizable lipids, helper phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids to create a more biocompatible formulation [34].

- For Viral Vectors: High viral titers can induce toxicity. Perform a dose-response curve to find the minimum effective titer. Consider switching serotypes (for AAV) or using less immunogenic viral backbones (e.g., using lentivirus instead of adenovirus where appropriate) [32] [34].

- A2: Immune Recognition:

- Solution: Use transient expression systems. The prolonged expression of Cas9 from viral vectors can trigger adaptive immune responses. Delivering pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes via VLPs or LNPs offers transient activity (1-2 day half-life), which minimizes both immune recognition and off-target editing risks [35] [3].

FAQ: Cargo Packaging and Release

Q: I am using VLPs, but the functional cargo is not being efficiently packaged or released in the target cell.

- A1: Inefficient Packaging:

- Solution: Fuse your cargo (e.g., a base editor protein) to the VLP scaffold protein (e.g., Gag) via a cleavable linker. Systematic optimization of this linker and the stoichiometry of packaging plasmids can dramatically enhance cargo loading [36]. Using a barcoded directed evolution approach, researchers have identified VLP capsid mutations that significantly increase RNP packaging capacity [35].

- A2: Inefficient Release in Cytosol:

- Solution: The cleavable linker between the cargo and scaffold protein is critical. Incorporate linkers that are efficiently cleaved by ubiquitous host proteases (e.g., viral proteases included in the VLP system) upon entry into the target cell's cytoplasm. Optimizing this linker sequence is a key strategy for ensuring effective cargo release and function [36].

Advanced Optimization: Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing VLP Delivery of CRISPR RNP

This protocol outlines the steps for developing and testing engineered VLPs for RNP delivery, based on recent directed evolution approaches [35].

Objective: To produce and characterize evolved VLPs (e.g., v5 eVLP) with improved production and transduction efficiencies for CRISPR-RNP delivery.

Materials:

- Producer Cells: HEK-293T cells

- Packaging Plasmids: Plasmids encoding VLP structural proteins (e.g., Gag), viral enzymes (e.g., Pol), and envelope protein (e.g., VSV-G)

- Cargo Plasmid: Plasmid encoding the cargo protein (e.g., Cas9) fused to the VLP scaffold via a cleavable linker

- Barcoded gRNA Library: A library of gRNAs where each gRNA contains a unique barcode sequence corresponding to a specific VLP variant

Method:

- Library Creation: Create a library of VLP capsid variants by introducing mutations into the gene encoding the major capsid protein.

- VLP Production: Co-transfect HEK-293T producer cells with the packaging plasmid mix and the barcoded gRNA library.

- Each VLP variant packages a gRNA with a unique barcode, linking the VLP's identity to its physical cargo [35].

- Selection Pressure: Harvest the VLPs and use them to transduce your target cell line. Apply a selective pressure (e.g., antibiotic selection if the gRNA targets an essential gene) to enrich for VLP variants that successfully deliver functional RNP.

- Variant Identification: Recover the genomic DNA from surviving target cells and sequence the barcode region of the integrated gRNA.

- The enriched barcodes identify the VLP capsid variants with the most favorable properties (e.g., high production, efficient transduction, and functional delivery) [35].

- Validation: Clone the identified beneficial mutations to create a new, optimized VLP (e.g., v5 eVLP). Validate its improved performance by comparing RNP packaging efficiency (e.g., via western blot) and functional gene editing efficiency (e.g., via T7E1 assay or NGS) against previous-generation VLPs.

Protocol: Enhancing Nuclear Delivery with hiNLS-Cas9

This protocol describes the implementation of hairpin internal nuclear localization signals (hiNLS) to boost CRISPR editing efficiency [3].

Objective: To design and test hiNLS-Cas9 constructs for enhanced editing in primary human cells.

Materials:

- hiNLS-Cas9 Constructs: Expression vectors for Cas9 with hiNLS sequences installed at selected sites within the protein backbone

- Control Constructs: Cas9 with standard terminally fused NLS

- Target Cells: Primary human T cells or other clinically relevant primary cells

- Delivery Method: Electroporation system or peptide-based non-viral delivery method

Method:

- Construct Design: Design and synthesize Cas9 genes incorporating short hiNLS sequences at internal, structured sites within the protein, avoiding catalytic domains.

- Protein Production: Express and purify the hiNLS-Cas9 and control NLS-Cas9 proteins from a suitable expression system (e.g., E. coli). Assess protein purity and yield.

- RNP Formation: Pre-complex the purified Cas9 proteins with target-specific sgRNA to form ribonucleoproteins (RNPs).

- Cell Delivery: Deliver the RNPs into primary human T cells using a clinically relevant method such as electroporation.

- Efficiency Analysis: After 2-4 days, harvest genomic DNA and assess editing efficiency at the target locus (e.g., TRAC or B2M) using T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) mismatch detection assays or next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Expected Outcome: hiNLS constructs should demonstrate higher editing efficiency and higher purity/yield upon production compared to terminally fused NLS constructs [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Delivery Optimization

| Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Core component of LNPs; encapsulates nucleic acids and facilitates endosomal escape [34]. | Formulating LNPs for in vivo delivery of CRISPR mRNA or sgRNA. |

| VSV-G Envelope Protein | A broad-tropism viral glycoprotein used to pseudotype viral vectors and VLPs [36]. | Enhancing the transduction efficiency of lentiviral vectors and VLPs across a wide range of cell types. |

| Cleavable Linkers (e.g., protease sites) | A peptide sequence fused between a cargo protein and a VLP scaffold; cleaved upon cell entry to release functional cargo [36]. | Enabling efficient packaging and intracellular release of editor proteins (e.g., Cas9, BE) from VLPs. |

| Hairpin Internal NLS (hiNLS) | Short peptide sequences inserted internally within the Cas9 protein to enhance nuclear import density [3]. | Boosting editing efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 RNP in primary and hard-to-transfect cells. |

| Barcoded gRNA Library | A pool of sgRNAs containing unique nucleotide sequence "barcodes" to identify specific VLP variants [35]. | Performing directed evolution of VLP capsids to select for variants with improved delivery properties. |

| Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) | A popular viral vector known for low immunogenicity and long-term gene expression; has limited cargo capacity [32] [34]. | Delivering CRISPR components in vivo for targets that fit within its packaging limit; often used with smaller Cas orthologs like SaCas9. |

Selecting the right gene-editing platform is a critical first step in designing efficient and reliable experiments. While the classic CRISPR-Cas9 system creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) to disrupt genes, newer platforms—Base Editing, Prime Editing, and Nickase systems—offer enhanced precision and control for specific applications. Your choice directly impacts the type of edit you can make, the precision required, and the potential for off-target effects. This guide provides a direct comparison, troubleshooting advice, and experimental protocols to help you select and optimize the ideal editor for your research goals, framed within the broader objective of maximizing editing efficiency.

Editor Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each editing platform to guide your initial selection [37] [38].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Precision Genome Editors

| Editor Type | Mechanism of Action | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickase (Cas9 D10A) | Creates a single-strand break ("nick") in the DNA [38]. | - Gene knockout (via paired nicking)- Reducing off-target effects [38]. | - Higher specificity than wild-type Cas9; requires two guides for a DSB, reducing off-target cleavage [38]. | - Requires design and delivery of two gRNAs for efficient knockout [38]. |

| Base Editor (BE) | Uses a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one base pair to another without creating a DSB [39] [37]. | - Point mutation introduction (e.g., C•G to T•A, A•T to G•C) [37] [38].- Correcting point mutations associated with genetic disease [39]. | - No DSB avoids indel byproducts from NHEJ [39].- High efficiency and product purity [37]. | - Limited to specific base transitions; cannot make all possible point mutations, insertions, or deletions [39] [38].- Potential for off-target RNA editing. |

| Prime Editor (PE) | Uses a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase and a pegRNA to directly "search and replace" DNA sequences [39] [37]. | - All 12 possible point mutations [37].- Precise insertions and deletions [39] [37]. | - Versatility: Can install a wide range of edits without a DSB or donor DNA template [39].- High precision and lower off-target effects than Cas9 [39]. | - Complex pegRNA design.- Generally lower editing efficiency than base editors, requiring careful optimization [39] [37]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic workflow common to all three editors, from component delivery to the final edited DNA sequence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I choose a Base Editor over a Prime Editor? Choose a Base Editor when your goal is to introduce one of the specific single-base changes it is engineered to make (e.g., C-to-T or A-to-G) and you prioritize high editing efficiency. Choose a Prime Editor when you need a type of edit that Base Editors cannot make, such as transversions (C-to-G, C-to-A, etc.), precise insertions, deletions, or any of the 12 possible point mutations [39] [37] [38].

2. How can I improve the low editing efficiency of my Prime Editor? Low prime editing efficiency is a common challenge. Focus on optimizing the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). This includes using a longer primer binding site (PBS) of around 13 nucleotides and ensuring the reverse transcriptase template (RTT) is not too long. Co-expressing a dominant-negative mismatch repair protein (e.g., MLH1dn) can also significantly enhance efficiency by preventing the cell from rejecting the newly incorporated edits [37].

3. My Base Editor is showing unwanted bystander edits. How can I mitigate this? Bystander edits occur when non-target bases within the activity window of the deaminase are modified. To minimize this, you can re-design your gRNA to position the target base in a location where adjacent editable bases are minimized. Alternatively, consider using engineered base editor variants with a narrower activity windows or altered sequence context preferences that are now available [37].

4. Why would I use a Nickase instead of the standard Cas9 nuclease? The primary reason is to reduce off-target effects. Because a single nick is typically repaired faithfully by the cell, using a Nickase with a single gRNA results in very low unintended mutagenesis. To create a knockout, you use a pair of nickases targeting opposite strands to generate a DSB, which requires both gRNAs to bind in close proximity, dramatically increasing specificity compared to wild-type Cas9 [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low Editing Efficiency Across All Editors

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inefficient nuclear delivery of editing components.

- Solution: Optimize the nuclear localization signal (NLS). A recent strategy demonstrated that using hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) sequences within the Cas9 backbone, rather than terminally fused NLS, can enhance nuclear import and significantly boost editing efficiency in primary human cells like T lymphocytes [3].

- Cause 2: Poor gRNA or pegRNA design.

- Solution: Utilize online design tools that predict on-target activity. For pegRNAs, systematically test different PBS and RTT lengths. Always check for potential secondary structures in the guide RNA that could inhibit binding [38].

- Cause 3: Low expression or stability of the editor protein.

Problem: High Off-Target Activity with Nickase or Base Editor

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Overexpression or prolonged expression of editing components.

- Cause 2: gRNA sequence has high similarity to other genomic sites.

- Cause 3 (Base Editors): gRNA-independent off-target DNA or RNA editing.

- Solution: This is due to the intrinsic activity of the deaminase domain. Use the newest generation of base editors that have been engineered with higher fidelity deaminase variants to minimize these effects [37].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing and Testing a Prime Editing Experiment

This protocol outlines the key steps for a standard prime editing workflow in cultured cells.

1. pegRNA Design:

- Identify the target sequence and the specific edit you want to introduce.

- Design the pegRNA to include:

- spacer sequence (~20 nt) complementary to the target DNA.

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): A ~13-nucleotide sequence that binds the nicked DNA strand to initiate reverse transcription.

- Reverse Transcriptase Template (RTT): A template that encodes your desired edit(s). It should be long enough to contain the edit but minimizing length to maintain efficiency.

- Use online software to help design and score pegRNAs.

2. Component Delivery:

- Transfert your cells with a plasmid expressing the prime editor (nCas9-RT fusion) and the pegRNA, or deliver as in vitro transcribed mRNA and synthetic pegRNA. For hard-to-transfect cells, consider using viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV). The choice between all-in-one and separate vectors can impact efficiency; all-in-one vectors ensure co-expression [38].

3. Analysis of Editing Outcomes:

- Harvest genomic DNA 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Amplify the target locus by PCR and subject the product to Sanger sequencing. For a more quantitative measure, use high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) to calculate the precise percentage of alleles edited [40].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Editor Specificity with Tag-Seq

This scalable method accurately identifies and characterizes editor-induced double-strand breaks or unintended edits across the genome [40].

1. Editor Transfection: Introduce your editing construct (e.g., Base Editor, Prime Editor) into your cell line (e.g., HEK293T, MCF7) using your standard method.

2. Genomic DNA Extraction and Shearing: Harvest cells and extract high-quality genomic DNA. Fragment the DNA by sonication or enzymatic digestion to an average size of 300-500 bp.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Ligate sequencing adapters to the fragmented DNA.

- Enrich for the target regions of interest or perform whole-genome sequencing.

- Sequence the libraries on an appropriate NGS platform.

4. Data Analysis:

- Map the sequencing reads to the reference genome.

- Use specialized analysis pipelines (e.g., the Tag-seq pipeline) to identify significant clusters of reads with indels (for nickase) or single-nucleotide variants (for base editors) that indicate potential off-target sites [40].

- Compare the experimental group to an untreated control to filter out background noise.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key materials required for setting up and analyzing genome editing experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Editor Expression Plasmid | Delivers the genetic code for the editor protein (e.g., BE, PE, Nickase) into the cell. | Plasmids like pCMV-PE2 for prime editing; all-in-one vectors simplify delivery [38]. |

| Guide RNA Expression Vector | Delivers the code for the gRNA or pegRNA. | Can be on a separate plasmid or part of an all-in-one system. U6 promoter is commonly used [38]. |

| Delivery Reagents | Facilitates the entry of editing components into cells. | Lipofectamine 3000 for plasmid transfection; electroporation for RNP delivery [38]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | Pre-complexed Cas protein and gRNA for transient, highly specific editing. | Ideal for sensitive primary cells (e.g., T-cells); reduces off-target effects and immune stimulation [3] [38]. |

| Donor DNA Template | Provides the homology template for HDR (for Nickase-mediated knock-in) or as a reference for design. | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) for small edits; double-stranded DNA for larger insertions [38]. |

| Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | Purifies DNA from cells for genotyping analysis. | Essential for post-editing validation (e.g., T7EI assay, Sanger sequencing, NGS). |

| PCR Reagents | Amplifies the target genomic locus for analysis. | High-fidelity polymerases are recommended to avoid introducing errors during amplification. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kit | For deep, quantitative analysis of on-target and off-target editing. | Provides the most comprehensive data on editing efficiency and specificity (e.g., Tag-seq) [40]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Neurons

Q: How can I improve neuronal survival during CRISPR screening? A: Neurons are particularly sensitive to DNA damage. To enhance survival and editing efficiency, consider switching from CRISPRn (CRISPR knockout) to CRISPRi (CRISPR interference). CRISPRi uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to silence gene expression without causing DNA double-strand breaks, which is less toxic to post-mitotic cells like neurons [41]. Furthermore, when performing survival-based screens, ensure the use of a focused, relevant library (e.g., targeting kinases or drug targets) to reduce stress on the cells from excessive transduction [41].

Q: What screening readouts work best for neuronal phenotypes? A: Neuronal function involves complex phenotypes like morphology and transcriptomic state. You can effectively screen for these using:

- High-content imaging to quantify changes in neurite outgrowth and branching [41].

- Single-cell RNA sequencing (e.g., CROP-seq, Perturb-seq) to profile transcriptomic changes resulting from genetic perturbations [41].

- FACS-based sorting if the phenotype can be linked to a fluorescent reporter or antibody staining [41].

Cardiomyocytes

Q: What is an efficient method to deliver CRISPR reagents to human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes? A: A major challenge is achieving high editing efficiency without compromising cell viability or differentiation potential. An optimized protocol is to perform reverse transduction at the iPSC stage [42].

- Protocol: Mix the lentiviral CRISPR library with dissociated iPSCs during plating, rather than adding the virus to already-adherent cells. This dramatically increases infection efficiency by exposing more cell surface area to the viral particles [42].

- Key Control: After transduction and selection, always check that your iPSCs maintain pluripotency markers (OCT4, Nanog, SOX2) and that they can still successfully differentiate into rhythmically beating cardiomyocytes expressing markers like cardiac Troponin T (cTNT) [42].

Q: How can I model specific disease toxicities, like chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, in cardiomyocytes? A: Genome-wide CRISPR knockout screens in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are powerful for this. As a proof of concept:

- Differentiate library-transduced iPSCs into cardiomyocytes [42].

- Treat the cardiomyocytes with the drug of interest (e.g., Doxorubicin) to induce cell death [42].

- Sequence the sgRNAs in surviving cardiomyocytes to identify "hits" – genes whose knockout conferred resistance. This approach has successfully identified novel human-specific transporters like SLCO1A2 that protect against Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity [42].

Primary Cells & Hard-to-Transfect Cells

Q: How can I enhance CRISPR editing efficiency in primary human T cells for therapeutic applications? A: For primary immune cells like T cells, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery is highly effective. To further boost efficiency, recent research has engineered hairpin internal Nuclear Localization Signals (hiNLS) within the Cas9 protein [3].

- Mechanism: These hiNLS constructs are integrated into the Cas9 backbone, unlike traditional terminally-fused NLS tags. This increases the density of NLS signals, improving nuclear import of the Cas9 RNP complex [3].

- Benefit: Since RNP has a short half-life, rapid nuclear entry is critical for high editing rates before the complex is degraded. This strategy has shown enhanced knockout of genes like B2M and TRAC in primary human T cells, which is crucial for cell-based therapies [3].

Q: My screen in a complex primary-like model (e.g., an organoid) has poor representation. How can I maintain library complexity? A: Maintaining library complexity through differentiation is critical. Start with a large number of iPSCs (e.g., 90 million) for library transduction to ensure initial diversity [42]. After puromycin selection and a period of expansion, sequence the sgRNAs to confirm minimal loss (e.g., <10% of sgRNAs). Successful differentiation should retain near genome-wide representation, with at least 3 sgRNAs per gene targeting over 13,000 genes in the final differentiated cell type [41] [42].

Table 1: Overview of CRISPR Screening Strategies in Different Cell Types

| Cell Type | CRISPR Type | Example Screening Phenotype | Library Size / Type | Key Challenge Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons [41] | CRISPRi | Neuronal survival, neurite morphology | ~2,000 genes (focused) | Sensitivity to DNA damage |

| Cardiomyocytes [42] | CRISPRn | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity | ~75,000 sgRNAs (genome-wide) | Low viral infection efficiency |

| Neural Progenitors [41] | CRISPRn | Susceptibility to Zika virus infection | Genome-wide | Viral infection & cell survival |

| Microglia [41] | CRISPRi/a | Phagocytosis, cell activation | ~2,000 genes (focused) | Complex functional phenotypes |

| T Cells (Primary) [3] | CRISPRn (RNP) | Knockout efficiency for therapy | N/A (specific targets) | Low editing efficiency in primary cells |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol Summary from Key Studies

| Experimental Step | Neurons (Tian et al.) [41] | Cardiomyocytes (Sapp et al.) [42] | Primary T Cells (Wilson et al.) [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Format | CRISPRi (dCas9 repressor) | CRISPRn (Lentiviral library) | CRISPRn (hiNLS-Cas9 RNP) |

| Delivery Method | Lentiviral transduction | Reverse lentiviral transduction | Electroporation |

| Key Reagents | CRISPRi-v2 library | Whole-genome CRISPRko library | hiNLS-Cas9 RNP complex |

| Screening Readout | Single-cell RNA-seq, Imaging | Cell survival under drug selection | Flow cytometry for protein knockout |

| Key Finding | Genes regulating survival & morphology | SLCO1A2 loss protects from toxicity | Enhanced editing efficiency & yield |

Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cell-Type Specific CRISPR Screening

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi System [41] | dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressor (KRAB); silences genes without DNA cleavage. | Ideal for neurons and other DNA damage-sensitive cells. |

| hiNLS-Cas9 [3] | Cas9 variant with hairpin internal Nuclear Localization Signals; enhances nuclear import. | Improves editing efficiency in primary cells (T cells) with RNP delivery. |

| Whole-genome CRISPRko Library [42] | Pooled lentiviral library (e.g., ~75,000 sgRNAs) for genome-wide knockout screens. | For unbiased discovery screens in iPSC-derived cells (cardiomyocytes). |

| Focused Library [41] | Smaller library targeting specific gene families (kinases, drug targets). | Reduces stress on cells; ideal for complex models like neurons and organoids. |

| CRISPR-GRANT [43] | Stand-alone graphical tool for CRISPR indel analysis from NGS data. | User-friendly analysis for wet-lab researchers; no command-line needed. |

| CRISPRMatch [44] | Automated pipeline for calculating mutation frequency and editing efficiency. | Processing high-throughput genome-editing data from NGS. |

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a powerful method used in drug discovery and the development of therapeutic agents that involves automated equipment to rapidly test thousands of samples [45]. In the context of CRISPR gene editing, HTS enables large-scale functional characterization of genes and rapid identification of optimal genetic targets [46]. This approach represents a significant advancement over single-gene editing experiments, allowing researchers to investigate complex biological processes and genetic interactions systematically [47]. The flexibility and editing efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 systems have established them as leading tools for high-throughput genetic screening, overcoming limitations of previous technologies like RNA interference (RNAi) which often resulted in incomplete gene suppression and high off-target effects [46].