Optimizing CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Primary Cells: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency in therapeutically relevant primary human cells.

Optimizing CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Primary Cells: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency in therapeutically relevant primary human cells. Covering foundational principles, advanced delivery methods, and rigorous validation strategies, we address the unique challenges of working with hard-to-transfect immune and stem cells. The content synthesizes the latest advancements, including epigenetic engineering and high-fidelity systems, to bridge the gap between high editing efficiency and genomic safety, offering a practical roadmap for preclinical and clinical application.

Understanding the Unique Landscape of Primary Cell Genome Editing

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenges

Q1: Why is CRISPR editing efficiency lower in non-dividing or quiescent primary cells? Non-dividing cells, such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, and resting T cells, possess unique biological properties that limit standard CRISPR mechanisms. DNA repair in these cells relies heavily on non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and lacks efficient homology-directed repair (HDR), which is cell-cycle dependent [1]. Furthermore, these cells often have condensed chromatin structure, limiting access to the target DNA, and maintain low levels of deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) due to factors like SAMHD1, which hinders editing methods relying on reverse transcription like prime editing [2].

Q2: What are the major transfection barriers in primary cells? Primary cells are notoriously difficult to transfect due to their sensitivity to external manipulation. Common barriers include:

- Delivery Efficiency: Physical methods like electroporation can cause significant cell death and are not always applicable in vivo [3].

- Cargo Size: The large size of Cas9 cDNA (~4.2 kb) makes it difficult to package into efficient delivery vectors like adeno-associated virus (AAV), which has a limited capacity [3].

- Cell Viability: High concentrations of CRISPR components can trigger toxic responses, leading to low survival rates post-transfection [4].

Q3: How does the cell cycle specifically influence CRISPR repair outcomes? The active DNA replication machinery in dividing cells favors certain repair pathways. Dividing cells, such as iPSCs, frequently use repair pathways like microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), which results in a broader distribution of indel sizes [1]. In contrast, postmitotic cells predominantly use classical NHEJ, leading to a narrower profile of smaller indels [1]. Furthermore, DNA mismatch repair (MMR), which is mostly active in dividing cells, can work against certain precise editing techniques like prime editing by rejecting the newly synthesized DNA strand [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency in Quiescent Primary Cells

Issue: Your primary cells (e.g., T cells, neurons, hepatocytes) show poor knock-in or HDR efficiency.

Solutions:

- Choose the Right Editor: For non-dividing cells, consider technologies that do not rely on HDR. Prime editing shows promise, though its efficiency in quiescent cells is limited by low dNTP pools [2]. ARCUS nucleases have demonstrated high-frequency homologous recombination in non-dividing hepatocytes (30-40% efficiency) [5].

- Modulate Cellular Factors: To enhance prime editing, target factors that restrict it in quiescence. Suppressing SAMHD1 activity increases dNTP availability and has been shown to significantly boost prime editing efficiency [2].

- Optimize Delivery for Cell Health: Use delivery methods that minimize toxicity. Virus-like particles (VLPs) can efficiently deliver Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) to sensitive cells like neurons with high efficiency (up to 97% transduction reported) while avoiding the long-term presence of editing components [1].

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Prime Editing in Quiescent Cells

- Objective: To improve prime editing efficiency in human resting lymphocytes.

- Materials: Prime editor (PE4 system), pegRNA, and SAMHD1 inhibitor (e.g, dNTPs or Vpx protein).

- Method:

- Isolate and culture primary human lymphocytes.

- Pre-treat cells with a SAMHD1 inhibitor for 12 hours to elevate intracellular dNTP levels.

- Deliver the prime editing components (PE4 and pegRNA) via electroporation or using engineered VLPs.

- Culture cells for at least 48-72 hours before analyzing editing outcomes via next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Validation: Compare the editing efficiency and product purity with and without SAMHD1 inhibition.

Problem: High Cell Death and Low Viability After Transfection

Issue: A large proportion of your primary cells die following transfection with CRISPR reagents.

Solutions:

- Titrate Reagent Concentration: High concentrations of Cas9-gRNA RNP are a common cause of toxicity. Start with lower doses and titrate upwards to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [4] [6].

- Switch Delivery Method: If using electroporation, optimize the electrical parameters (voltage, pulse length). For hard-to-transfect cells, lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs) can be a gentler alternative [3] [5]. Synthego's automated platform testing up to 200 electroporation conditions identified a protocol that increased editing efficiency in THP-1 cells from 7% to over 80% while maintaining viability [6].

- Use RNP Complexes: Delivery of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes is often less toxic and has a shorter cellular half-life than plasmid DNA, reducing off-target effects and cell stress [4] [1].

Problem: Inefficient Delivery to Sensitive Primary Cells

Issue: Your chosen delivery method (e.g., chemical transfection) is ineffective for your primary cell type.

Solutions:

- Use a Positive Control: Always include a positive control (e.g., a well-validated gRNA) during optimization to distinguish between delivery failure and gRNA failure [6].

- Select a Clinically Relevant Vector: For in vivo delivery to non-dividing tissues, engineered virus-like particles (eVLPs) have shown success in delivering RNP to retinal pigment epithelium in mice, achieving 16.7% average editing efficiency [5]. For ex vivo work, flow electroporation platforms (e.g., MaxCyte ExPERT) are designed for scalable transfections in clinical development [5].

- Optimize Systematically: Do not rely on standard protocols. Perform a multi-parameter optimization for your specific cell line, testing 7 or more conditions covering different reagent ratios, delivery parameters, and cell densities [6].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research to aid in experimental planning and comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Editing Outcomes in Dividing vs. Non-Dividing Cells

| Cell Type / State | Predominant DNA Repair Pathway | Typical Indel Profile | Time to Indel Plateau | HDR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dividing (iPSCs) | MMEJ, NHEJ | Broad range, larger deletions [1] | 1-3 days [1] | Higher (cell cycle dependent) |

| Non-Dividing (Neurons) | Classical NHEJ | Narrow range, small indels [1] | Up to 2 weeks [1] | Very Low |

| Activated T Cells | MMEJ, NHEJ | Broad range | Similar to dividing cells | Moderate |

| Resting T Cells | Classical NHEJ | Small indels | Prolonged | Very Low |

Table 2: Efficiency of Different Delivery Systems

| Delivery Method | Typical Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Efficiency (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation | Ex vivo, various cell types | High efficiency for many cells, direct RNP delivery | Can cause significant cell toxicity [3] | >80% in THP-1 after optimization [6] |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | In vivo & ex vivo, neurons | High transduction (up to 97%), RNP delivery, transient [1] | Complex production, packaging size constraints | 97% transduction in human neurons [1] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo & ex vivo | Low immunogenicity, repeat dosing, scalable [5] | Mostly liver-tropic, ongoing research to target other tissues | Successful in vivo CAR-T generation [5] |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | In vivo gene therapy | High tropism, long-term expression | Small packaging capacity (<4.7 kb) [3] | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduces off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity. | Critical for therapeutic applications to minimize unintended mutations [4]. |

| HDR Enhancer Proteins | Boosts homology-directed repair efficiency. | IDT's Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein increased HDR efficiency up to 2-fold in iPSCs and hematopoietic stem cells [5]. |

| Prime Editing (PE) Systems | Enables precise point mutations, small insertions, and deletions without double-strand breaks. | PE4 system achieved 34.8% correction of a cardiomyopathy-causing mutation in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes [5]. |

| GMP-grade gRNA and Cas9 | Ensures purity, safety, and efficacy for clinical trial development. | Essential for transitioning from research to clinical applications; lack of true GMP reagents is a major hurdle [7]. |

| Chemical Synchronization Agents | Arrests cells at specific cell cycle stages (e.g., G1/S with palbociclib). | Useful for studying cell-cycle dependence of editing, but can impact cell health and DNA repair [8]. |

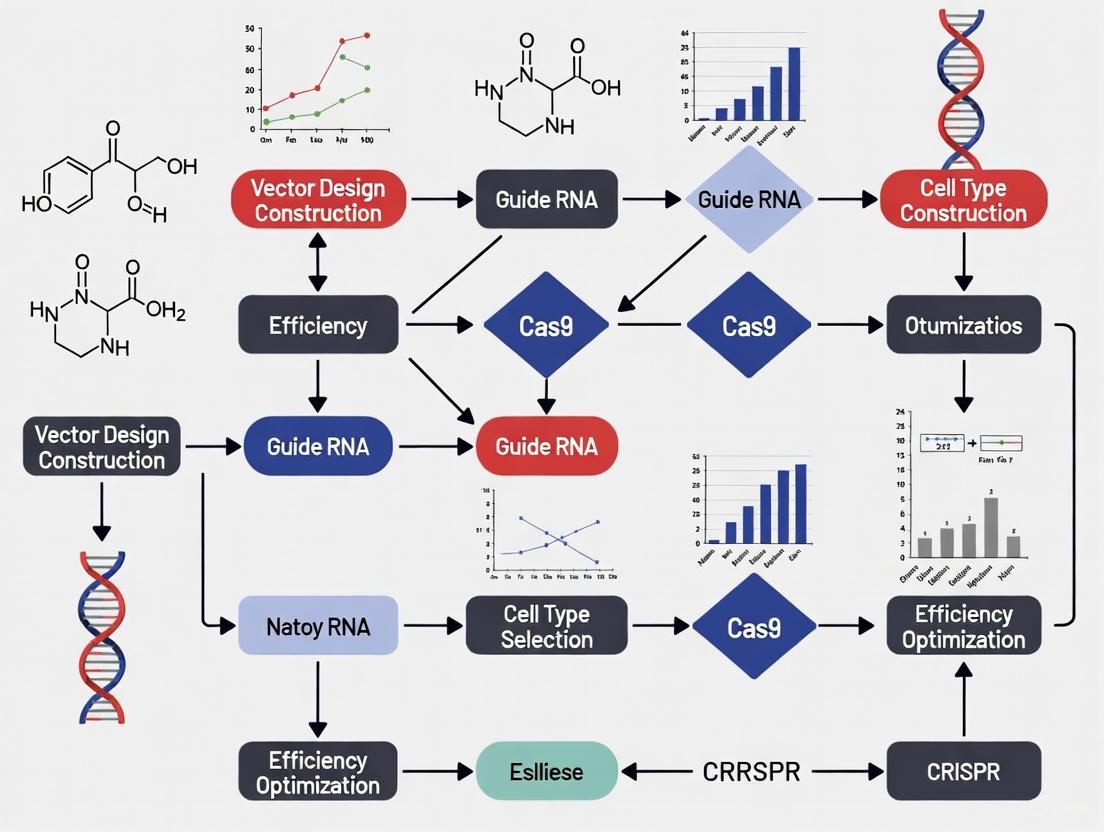

Supporting Diagrams

DNA Repair Pathways in Cell Editing

Optimizing CRISPR Workflow

FAQs: Troubleshooting Your CRISPR Screens in Primary Cells

Q1: Why is my CRISPR screen in primary human NK cells showing poor editing efficiency and cell viability?

A: Genome-wide CRISPR screens in primary NK cells are hampered by technical challenges, including difficulties in achieving efficient editing at the required scale. To overcome this, ensure extensive optimization of your electroporation parameters. One developed protocol involves using a retroviral vector system for sgRNA delivery, followed by electroporation with Cas9 protein. Key steps include confirming stable sgRNA integration via puromycin selection and using targeted ablation of a surface marker (e.g., PTPRC/CD45) to validate editing efficiency, which achieved over 90% knockout. Maintaining cell fitness post-electroporation is critical for a successful screen [9].

Q2: Our hiPS cells show high sensitivity to perturbations in mRNA translation machinery compared to differentiated cells. Is this a common dependency, and how should we adjust our screen design?

A: Yes, this is a recognized dependency. Comparative CRISPRi screens reveal that human induced pluripotent stem (hiPS) cells are exceptionally sensitive to perturbations in the mRNA translation machinery, with 76% of targeted genes being essential, compared to 67% in neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and HEK293 cells. This is likely linked to their exceptionally high global protein synthesis rates. When designing screens, do not assume genetic dependencies are universal. It is crucial to:

- Profile essentiality across multiple relevant cell types, as dependencies can be highly context-specific.

- Focus on translation-coupled quality control pathways, as these show pronounced cell-type-specific effects [10].

Q3: What are the major logistical challenges in transitioning a CRISPR-based therapy from research to clinical trials?

A: Several key challenges exist beyond the science itself:

- Regulatory Hurdles: The existing FDA framework, designed for small-molecule drugs, is a poor fit for the complexity of CRISPR therapies, leading to unclear guidelines [7].

- Procurement of GMP Reagents: There is a critical shortage of suppliers offering true GMP-grade CRISPR reagents (e.g., gRNAs, Cas nuclease), and demand is outstripping supply. Using "GMP-like" reagents can jeopardize clinical translation [7].

- Maintaining Consistency: Changing vendors between research and clinical stages can introduce variability in reagents, leading to discrepant results and potential safety risks. Using a consistent vendor from bench to bedside is recommended [7].

Q4: How can computational tools help improve the precision of our CRISPR experiments?

A: Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are becoming leading methods for predicting both on-target and off-target activity of CRISPR systems. Their accuracy is continually improving as more experimental data is incorporated into training models. You can use these tools to:

- Design optimal gRNAs with high predicted on-target efficiency.

- Predict potential off-target sites across the genome before conducting experiments, which is crucial for mitigating one of the major challenges in clinical CRISPR application [11] [3].

Comparative Genetic Dependency Data from CRISPRi Screens

The table below summarizes quantitative data on gene essentiality from a comparative CRISPRi screen targeting mRNA translation machinery components in different cell types [10].

| Cell Type | Number of Genes Targeted | Genes Essential in This Cell Type (Count) | Genes Essential in This Cell Type (%) | Notable Cell-Type-Specific Essential Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hiPS Cells | 262 | 200 | 76% | ZNF598 (and other ribosome collision sensors) |

| Neural Progenitor Cells (NPCs) | 262 | 175 | 67% | — |

| HEK293 Cells | 262 | 176 | 67% | CARHSP1, EIF4E3, EIF4G3, IGF2BP2 |

| Neurons (Survival) | 262 | 118 | 45% | NAA11 |

| Cardiomyocytes (Survival) | 262 | 44 | 17% | CPEB2 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their functions for executing CRISPR screens in primary and stem cells, as detailed in the cited protocols [12] [9] [10].

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Protein | Generates double-strand breaks at the DNA target site specified by the gRNA. | Using recombinant protein complexed with gRNA as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is common for ex vivo editing of primary cells [12] [9]. |

| Synthego Custom gRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific genomic locus for cleavage. | Critical for specificity. GMP-grade gRNAs are required for clinical applications [12] [7]. |

| AAV Serotype 6 (AAV6) | Acts as a viral vector to deliver the DNA repair template for homology-directed repair (HDR). | Effective for transducing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Has a packaging limit of <4.7 kb [12] [3]. |

| Inducible KRAB-dCas9 System | A CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system for gene knockdown without double-strand breaks. | Allows for screening in sensitive cell types like hiPS cells without triggering p53-mediated toxicity [10]. |

| Lentiviral sgRNA Library | Delivers a pooled library of guide RNAs for large-scale, loss-of-function screens. | Enables genome-wide or focused screens. Requires optimization for transduction efficiency in primary cells [9] [10]. |

| Cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3L, IL-6, IL-3) | Supports the ex vivo culture, expansion, and maintenance of primary cells like HSPCs and NK cells. | Essential for maintaining cell viability and function during the editing process [12] [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide CRISPR Screening in Primary Human NK Cells [9]

This protocol enables unbiased interrogation of gene knockouts that enhance NK cell antitumor activity.

- NK Cell Expansion: Isolate and expand primary human NK cells from cord blood using engineered universal antigen-presenting feeder cells (uAPCs) and IL-2 (200 IU/mL).

- Library Transduction: On day 5 of expansion, transduce NK cells with a pooled, genome-wide lentiviral sgRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure one guide per cell.

- Electroporation: Electroporate the transduced cells with Cas9 protein using optimized electrical pulse codes to ensure efficient editing while maintaining viability.

- Selection and Expansion: Select successfully transduced cells with puromycin and re-expand them with feeder cells and IL-2.

- Phenotypic Challenge: Subject the edited NK cell pool to multiple rounds of challenge with cancer cells (e.g., pancreatic cancer Capan-1 cells) to induce a dysfunctional state.

- Cell Sorting and Sequencing: After the final challenge, sort NK cell populations based on a functional marker (e.g., LAMP1/CD107a for degranulation) or simply culture for outgrowth. Extract genomic DNA from pre- and post-selection samples and perform deep sequencing to quantify sgRNA abundance.

- Data Analysis: Identify enriched or depleted sgRNAs using specialized bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., MAGeCK) to reveal hits that confer a fitness advantage or disadvantage under selective pressure.

Protocol 2: Inducible CRISPRi Screening in hiPS Cells and Differentiated Progeny [10]

This protocol compares gene essentiality across a developmental lineage using a non-cutting CRISPR system.

- Engineer Inducible Cell Line: Generate a reference hiPS cell line with a doxycycline-inducible KRAB-dCas9 expression cassette inserted into a safe harbor locus (e.g., AAVS1).

- Differentiation: Differentiate the engineered hiPS cells into target lineages, such as neural progenitor cells (NPCs), neurons, and cardiomyocytes, using established protocols.

- sgRNA Library Transduction: Transduce the indducible hiPS cells and their differentiated counterparts with a lentiviral sgRNA library targeting genes of interest (e.g., mRNA translation factors).

- Gene Knockdown Induction: Add doxycycline to the culture medium to induce KRAB-dCas9 expression and initiate targeted gene repression.

- Phenotypic Outgrowth: Culture the cells for approximately ten population doublings (for proliferative cells) or for a set survival period (for post-mitotic neurons/cardiomyocytes) to allow phenotypic consequences to manifest.

- Sequencing and Hit Calling: Harvest cells, extract genomic DNA, and sequence the integrated sgRNAs. Calculate gene-level enrichment or depletion scores using a CRISPRi-specific analysis pipeline (e.g., CRISPRiDesign) to identify essential genes in each cellular context.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

CRISPRi Screen Workflow Across Cell Types

Translation Stress Response in hiPS Cells

FAQs: Epigenetic Editing in Primary Cells

Q1: What are CRISPRoff and CRISPRon, and how do they differ from standard CRISPR-Cas9?

CRISPRoff and CRISPRon are epigenetic editing tools based on a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to epigenetic modifiers, such as DNA methyltransferases or histone deacetylases [13]. Unlike standard CRISPR-Cas9, which creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) to permanently alter the DNA sequence, these tools reversibly modulate gene expression without changing the underlying genetic code. CRISPRoff typically silences genes by adding repressive methyl marks to DNA or histones, while CRISPRon can reverse this silencing or activate genes by removing these marks or adding activating marks [14].

Q2: What are the main advantages of using epigenetic editing like CRISPRoff/CRISPRon in primary cell research?

The key advantages are:

- No DSBs: Eliminates the risks associated with DNA breaks, such as unwanted indels from non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or translocations [14].

- Reversibility and Tunability: Epigenetic modifications can be reversed, allowing for dynamic studies of gene function [14].

- Persistence: Some epigenetic marks can be maintained through cell divisions, leading to sustained gene expression changes even after the editing machinery is no longer present.

- Applicability in Non-Dividing Cells: Epigenetic editors do not require active cell division to function, making them highly suitable for hard-to-transfect primary cells like neurons and resting T-cells [1].

Q3: I am experiencing low editing efficiency in my primary T cells. What strategies can I use to improve this?

Low efficiency in primary cells is common. To improve it, consider these strategies:

- Use Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes: Deliver pre-assembled complexes of dCas9 protein and guide RNA via electroporation. RNPs act transiently, reducing off-target effects and cell toxicity, and have been shown to achieve high editing efficiencies in primary T cells [15] [16].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Use chemically synthesized, modified guide RNAs (e.g., with 2'-O-methyl analogs) to enhance stability and reduce innate immune responses [15] [16].

- Validate Multiple gRNAs: Test 2-3 different gRNAs for your target to identify the most effective one, as efficiency can vary significantly [16].

- Utilize Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): For particularly sensitive cells, VLPs can be an efficient method for delivering epigenetic editors, as demonstrated in human iPSC-derived neurons [1].

Q4: How can I minimize off-target effects in epigenetic editing?

While generally having fewer safety concerns than nuclease-based editing, off-target epigenetic modifications can still occur.

- Choose High-Fidelity Systems: Select engineered dCas9 variants with higher specificity.

- Optimize gRNA Design: Use computational tools to design gRNAs with minimal off-target potential across the genome. Truncated gRNAs can also increase specificity [17].

- Control Expression: Use transient delivery methods like RNPs or mRNA instead of plasmids to limit the duration of editor expression, thereby reducing the window for off-target activity [15] [17].

- Titrate Components: Use the lowest effective concentration of the RNP complex to minimize off-target editing while maintaining on-target activity [4].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Gene Silencing/Knockdown Efficiency with CRISPRoff

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Ineffective gRNA | Design and test multiple gRNAs. Use predictive algorithms to select gRNAs targeting promoter regions and ensure the target site is not blocked by nucleosomes [18]. |

| Inefficient Delivery | Switch to RNP delivery via electroporation for primary immune cells. For other primary cells, optimize nucleofection protocols or explore VLP delivery [15] [1]. |

| Insufficient Editor Activity | Use a strong, cell-type-specific promoter to drive the expression of the epigenetic effector. Fuse to potent epigenetic domains (e.g., DNMT3A) and consider using synergistic effector systems. |

| Rapid Reversion of Marks | The targeted locus might be resistant to long-term silencing. Consider using editors that recruit multiple repressive complexes or performing repeated editing. |

Problem: High Cell Toxicity or Poor Viability Post-Editing

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Delivery Method | Electroporation can be harsh. Optimize electroporation buffer and program settings specifically for your primary cell type. |

| High RNP/DNA Concentration | Titrate down the amount of RNP complex or DNA delivered. Start with lower doses and increase gradually to find the optimal balance between efficiency and viability [4]. |

| Innate Immune Activation | Use chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs, which are less likely to trigger immune responses compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) RNAs [16]. |

| Prolonged Expression | Avoid plasmid-based delivery that leads to sustained expression. Use transient RNP delivery to limit the duration of editor presence in the cell [15]. |

Data Presentation: Strategies for Optimizing Editing in Primary Cells

The table below summarizes key optimization parameters based on successful protocols from recent literature.

| Optimization Parameter | Recommended Strategy | Application/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Format | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [15] [16] | Reduces toxicity and off-target effects; enables rapid editing without integration; highly effective in primary T cells. |

| gRNA Design | Chemically modified, synthetic sgRNAs [16] | Increases nuclease resistance and editing efficiency; reduces immune stimulation. |

| gRNA Selection | Test 2-3 gRNAs per target [16] | Identifies the most effective guide empirically, as predictive algorithms are not perfect. |

| Delivery Method | Electroporation (e.g., 4D-Nucleofector) [15] | High efficiency for hard-to-transfect primary cells; optimized protocols exist for various cell types. |

| Cell Health | Use early-passage, high-viability cells; optimize recovery media | Primary cells are sensitive; starting with healthy cells is critical for post-editing survival. |

| Timeline for Analysis | Allow extended time for outcome analysis (e.g., up to 16 days in neurons) [1] | Epigenetic changes and their functional outcomes may manifest slowly in non-dividing primary cells. |

Experimental Protocol: Epigenetic Silencing in Primary T Cells using CRISPRoff-based RNP Delivery

This protocol outlines a method for transient, DNA-free epigenetic silencing in human primary T cells.

Key Reagents:

- Primary Human T Cells: Isolated from peripheral blood.

- dCas9-Epigenetic Effector Protein: Purified recombinant dCas9 fused to a DNA methyltransferase (e.g., DNMT3A) or histone methyltransferase (e.g., SUV39H1).

- Chemically Modified sgRNA: Synthetic sgRNA targeting the gene of interest, designed with proprietary stability-enhancing modifications (e.g., Alt-R CRISPR modifications).

- Nucleofector System & Kit: Specifically formulated for primary T cells.

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Assembly: Combine the dCas9-effector protein and synthetic sgRNA at a predetermined molar ratio in a sterile tube. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow RNP complex formation.

- T Cell Preparation: Isolate and count primary T cells. Ensure viability is >95%. Centrifuge cells and resuspend in the provided Nucleofector solution at a specific concentration.

- Electroporation: Add the pre-assembled RNP complex to the cell suspension. Transfer the entire mixture into a certified cuvette. Electroporate using the recommended program for primary T cells.

- Cell Recovery: Immediately after electroporation, add pre-warmed recovery medium to the cuvette. Gently transfer the cells to a culture plate pre-filled with complete medium supplemented with IL-2.

- Culture and Analysis:

- Culture the cells under standard conditions.

- Day 2-3: Assess cell viability and activation status via flow cytometry.

- Day 5-7: Analyze initial gene silencing efficiency via RT-qPCR to measure mRNA levels.

- Day 7-14: Perform downstream analyses such as bisulfite sequencing to confirm DNA methylation changes or functional assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic Editing

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| dCas9-Epigenetic Effector Fusions | The core enzyme; dCas9 provides target specificity via gRNA, while the fused effector (e.g., DNMT3A, TET1, p300) writes or erases specific epigenetic marks on DNA or histones [13] [14]. |

| Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the dCas9-effector to the target genomic locus. Chemical modifications enhance stability, improve editing efficiency, and reduce toxic immune responses in primary cells [16]. |

| Nucleofector System | An electroporation device optimized for hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells and neurons. Critical for efficient RNP delivery into these sensitive cell types [15]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | A delivery vehicle engineered to carry protein cargo (e.g., Cas9 RNP). Useful for delivering editors to cells that are refractory to electroporation, such as neurons [1]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Engineered Cas proteins with reduced off-target activity. Using high-fidelity versions of dCas9 can improve the specificity of epigenetic modifications [13] [17]. |

Visualization: Workflow for Epigenetic Editing in Primary Cells

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for implementing an epigenetic editing experiment in primary cells.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my CRISPR protocols, optimized in HEK293 or HeLa cells, fail when I move to primary human T cells or hematopoietic stem cells?

Protocol failure occurs because immortalized cell lines and primary cells differ in nearly every biological aspect that influences CRISPR efficiency. The table below summarizes the critical divergences.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Immortalized and Primary Cells Impacting CRISPR Editing

| Biological Characteristic | Immortalized Cell Lines (e.g., HEK293, HeLa) | Primary Cells (e.g., T cells, HSCs) | Impact on CRISPR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation Rate | High, continuous division [19] | Often slow or quiescent [20] | Limits access to HDR, which is most active in S/G2 cell cycle phases [20] |

| DNA Repair Pathway Dominance | NHEJ and HDR are active | Heavily biased towards error-prone NHEJ [20] | Results in high indel rates and low HDR knock-in efficiency in primary cells [20] |

| Epigenetic Landscape | Often altered, simplified, and unstable [21] | Native, complex, and tightly regulated [22] | Affects sgRNA binding accessibility and Cas9 on-target activity [22] |

| Response to DSBs | Tolerates high levels of DNA damage [23] | Highly sensitive; prone to apoptosis or senescence [23] | Lower viability post-transfection/nucleofection in primary cells [19] |

| Transfection Efficiency | Generally high and easy to achieve [19] | Low; requires optimized methods like nucleofection [19] [24] | Directly reduces the percentage of cells receiving CRISPR components |

Q2: What are the specific safety risks of using CRISPR in primary cells for therapeutic applications?

Beyond common off-target effects, primary cells are uniquely vulnerable to on-target structural variations (SVs). These large, complex aberrations are a critical safety concern for clinical translation.

Table 2: Safety Risks in Primary vs. Immortalized Cells

| Risk Type | Description | Clinical Concern | Relative Risk in Primary Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Deletions/Megabase Losses | Deletions spanning kilobases to megabases from the on-target cut site [23] | Loss of tumor suppressor genes or critical regulatory elements [23] | Higher, due to sensitive DNA damage response [23] |

| Chromosomal Translocations | Rearrangements between different chromosomes after simultaneous DSBs [23] | Potential oncogenic activation (e.g., in proto-oncogenes) [23] | Significant, especially with multiple sgRNAs or in p53-deficient clones [23] |

| p53-Mediated Stress Response | Activation of the p53 pathway post-DSB, leading to cell death or arrest [23] | Selective outgrowth of p53-deficient cells with genomic instability [23] | Pronounced, raising oncogenic concerns in therapeutic products [23] |

Q3: My goal is stable gene silencing in primary T cells. Is CRISPR knockout my only option?

No. CRISPRoff for epigenetic silencing is a genetically safer alternative. Unlike CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease, CRISPRoff uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains to establish heritable gene silencing without creating double-strand breaks. This avoids the risks of genomic instability, chromosomal translocations, and indels, making it ideal for sensitive primary cells [22].

Q4: How can I enhance knock-in efficiency in hard-to-transfect primary B cells?

Successful knock-in in primary B cells requires shifting the DNA repair balance from NHEJ to HDR.

- HDR Template Design: Use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) templates for small insertions (e.g., tags, point mutations) with 30-60 nt homology arms. For larger insertions (e.g., fluorescent proteins), use double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates with 200-300 nt homology arms [20].

- Strand Preference: For edits located >10 bp from the cut site, design your template with strand preference in mind: use the targeting (sgRNA-bound) strand for PAM-proximal edits and the non-targeting strand for PAM-distal edits [20].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Caution is advised. While inhibiting NHEJ factors like DNA-PKcs can enhance HDR, it can also dramatically increase the frequency of large deletions and chromosomal translocations [23]. Transient inhibition of 53BP1 may be a safer alternative, but extensive validation is required [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low HDR Knock-in Efficiency in Primary Human T Cells

Potential Causes:

- Quiescent Cell State: Primary T cells are often non-dividing, favoring the NHEJ repair pathway over HDR [24] [20].

- Suboptimal HDR Template: Incorrect template format, length, or design.

- Cellular Toxicity: High cell death from delivery methods (e.g., electroporation), leaving insufficient healthy cells for HDR.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Activate and Expand T Cells: Stimulate T cells using CD3/CD28 agonists and culture in IL-2 for 48-72 hours pre-editing. This pushes cells into cycle, promoting HDR [24].

- Optimize Template Delivery: Co-deliver Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes with a ssDNA HDR template during nucleofection. Ensure the template's homology arms are 30-60 nt long [20].

- Titrate Reagents: Perform a dose-response curve for the Cas9 RNP complex. Using excessive nuclease increases DSBs and toxicity, reducing HDR efficiency.

- Validate and Sequence: Use flow cytometry or PCR to check knock-in success. Always confirm precise integration with Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

Problem: High Cell Death Post-Transfection in Primary Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells (HSPCs)

Potential Causes:

- Innate Sensitivity to DSBs: Primary stem cells have a robust DNA damage response, triggering apoptosis or senescence upon Cas9 cutting [23].

- Delivery Method Toxicity: Standard transfection methods are too harsh.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Switch to RNP Delivery: Use pre-complexed Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). RNP editing is fast, precise, and reduces off-target effects and cellular stress compared to plasmid DNA delivery [19].

- Use a Gentler Delivery System: Utilize a Nucleofector system with programs and kits specifically optimized for HSPCs. This maximizes delivery while preserving viability [19].

- Consider Alternative Editors: For gene silencing, use CRISPRoff (epigenetic editing) to avoid DSBs entirely [22]. For single-base changes, investigate base or prime editors.

- Monitor Genomic Integrity: Employ long-range PCR or CAST-Seq to screen for unexpected on-target structural variations that could impair cell health [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Optimizing CRISPR in Primary Cells

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Consideration for Primary Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 and sgRNA; enables rapid, transient editing with reduced off-target effects [19] | Gold standard for primary cells; reduces toxicity and avoids the need for transcription/translation [19] [24] |

| CRISPRoff System | dCas9 fused to DNMT3A/3L and KRAB for heritable, DSB-free gene silencing via DNA methylation [22] | Safer alternative to knockout; ideal for sensitive cells like HSCs and T cells where genomic integrity is paramount [22] |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic sgRNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to improve stability and reduce immune activation [7] | Enhances editing efficiency and consistency in primary human cells, which can have robust nucleic acid sensing pathways. |

| cGMP-Grade Guides & Nucleases | Reagents manufactured under current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations for clinical use [7] | Mandatory for therapeutic development; ensures purity, safety, and efficacy. Avoids "GMP-like" reagents which may not meet regulatory standards [7] |

| Cell-Type Specific Nucleofection Kits | Optimized buffers and electrical parameters for specific primary cell types (e.g., T cells, HSCs) [19] | Crucial for achieving high efficiency and viability; standard electroporation buffers are often suboptimal and toxic. |

Advanced Delivery and Editing Strategies for Clinical Applications

For researchers aiming to optimize CRISPR editing efficiency in primary cells, selecting the appropriate editing modality is a critical first step. Primary cells, which are freshly isolated from living tissue and not immortalized, present unique challenges including limited lifespan, sensitivity to manipulation, and innate immune responses to foreign genetic material [15]. The choice between nuclease editing, base editing, epigenetic control, and transcriptional regulation depends heavily on your experimental goals, the nature of your target cells, and the specific outcome you wish to achieve. This guide addresses common questions and troubleshooting scenarios to help you navigate this complex decision-making process and implement robust protocols for your primary cell research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary considerations when choosing a CRISPR modality for primary cells?

The key considerations are your desired genomic outcome, the cell cycle status of your primary cells, and the potential for off-target effects.

- Goal: Do you need a complete gene knockout, a precise single-base change, or transient gene regulation?

- Cell Cycle: Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), required for precise knock-in, is inefficient in non-dividing primary cells as it is active only in the S/G2 phases. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is active throughout the cell cycle [15]. A recent 2025 study confirmed that postmitotic cells like neurons and resting T cells have fundamentally different DNA repair pathways than dividing cells, favoring NHEJ over other repair mechanisms [1].

- Off-Targets: The risk of unintended edits varies by nuclease and modality. Nuclease-based knockout has a higher inherent risk than some newer modalities [25].

Q2: Why is HDR so inefficient in primary cells, and what can be done to improve it?

HDR efficiency is low because most primary cells are quiescent (non-dividing). HDR requires a sister chromatid template, which is only available after DNA replication [15].

- Solution: Use Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for delivery. RNP delivery is fast and transient, coinciding with the short window of HDR activity. Furthermore, synchronizing your primary cell culture to the S or G2 phase can increase HDR efficiency [15].

Q3: How can I minimize off-target editing in my primary cell experiments?

Off-target editing occurs when the CRISPR machinery acts at sites with DNA sequences similar to your target.

- Choose High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Engineered nucleases like eSpCas9(1.1) and SpCas9-HF1 are designed to reduce off-target effects by weakening non-specific interactions with DNA [13] [26].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Select gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target scores using design tools. Use chemically modified synthetic gRNAs (e.g., with 2'-O-methyl analogs) to enhance stability and specificity. Shorter guide RNAs (17-18 nucleotides) can also reduce off-target activity [25].

- Select the Right Delivery Method and Cargo: Delivery format impacts how long the nuclease is active. Using RNP complexes, which have a short half-life, significantly reduces the window for off-target editing compared to plasmid DNA, which persists longer [25] [15].

Q4: My primary cells are hard to transfect. What is the best delivery method?

Electroporation of pre-assembled Cas9 RNP complexes is widely considered the gold standard for difficult-to-transfect primary cells, such as T cells and neurons [15].

- Advantages of RNP Electroporation:

- High Efficiency: Achieves high editing rates even in sensitive cells.

- Low Toxicity: RNP components are transient and do not integrate into the genome.

- Rapid Action: Editing begins immediately after delivery, reducing cellular stress [15].

- Avoids Immune Activation: Bypasses the need for transcription and translation, which can trigger antiviral responses in primary immune cells [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency in Primary T Cells or NK Cells

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Suboptimal delivery of CRISPR components.

- Solution: Implement the SLICE (sgRNA Lentiviral Infection with Cas9 Protein Electroporation) method. As used in genome-wide T cell and NK cell screens, this involves lentiviral delivery of the sgRNA and electroporation of Cas9 protein [9] [27]. This combines stable genomic integration of the guide with highly efficient protein delivery.

Cause: Poor cell viability post-transfection.

- Solution: Titrate the amount of Cas9 RNP complex. High concentrations can be toxic. Use chemically synthesized, modified sgRNAs to enhance nuclease stability and reduce the required dose [25] [15]. Ensure post-electroporation recovery media contains appropriate cytokines (e.g., IL-2 for T cells) [9].

Cause: Inefficient gRNA.

- Solution: Always design and test 3-4 different gRNAs for your target. Use bioinformatic tools to select guides with high predicted on-target activity [6].

Problem: Inefficient Knock-in (HDR) in Non-Dividing Primary Cells

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: HDR pathway is largely inactive in postmitotic cells.

- Solution: Consider alternative modalities. Base editing or prime editing can introduce precise changes without requiring DSBs or the HDR pathway, making them ideal for non-dividing cells [25]. A 2025 study also showed that chemical or genetic perturbation of the DNA repair network in neurons can shift repair outcomes, offering a potential strategy to improve desired edits [1].

Cause: The HDR donor template is not being co-delivered efficiently.

- Solution: Electroporate the single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) HDR donor template alongside the Cas9 RNP complex. Using a "cocktail" of Cas9 RNP and donor DNA is a standard protocol for knock-in experiments in primary T cells [15].

Modality Comparison and Selection Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the four main CRISPR modalities to guide your selection.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Genome Editing Modalities

| Modality | Mechanism of Action | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited Primary Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Editing (e.g., Cas9, Cas12) | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) repaired by NHEJ or HDR [13]. | Gene knockouts, gene knock-ins, large deletions [13]. | Highly effective for complete gene disruption; most mature and widely used technology. | Off-target DSB risk [25]; HDR is very inefficient in non-dividing cells [15]. | Activated T cells, NK cells, proliferating progenitors. |

| Base Editing | Uses catalytically impaired Cas fused to a deaminase enzyme to directly convert one base pair to another without a DSB [25]. | Point mutations, correcting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). | Does not require a DSB or donor template; higher efficiency and fewer indels than HDR; works in non-dividing cells [25]. | Limited by strict editing window (~10-15 bp); cannot make all possible base changes. | Neurons [1], cardiomyocytes, resting immune cells. |

| Epigenetic Editing | Uses dCas9 fused to epigenetic effector domains (e.g., methyltransferases, acetyltransferases) [13] [28]. | Targeted DNA methylation or histone modification to alter gene expression. | Reversible modulation of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. | Changes are often transient; requires detailed knowledge of epigenetic regulation. | Cells for disease modeling where long-term epigenetic reprogramming is needed. |

| Transcriptional Control | Uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64) or repressors (e.g., KRAB) [13] [26]. | Gene activation (CRISPRa) or repression (CRISPRi). | Reversible, tunable gene regulation; no DNA damage. | Effects are transient; potential for off-target transcriptional changes. | Functional genomics screens in any primary cell type. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-wide CRISPR Knockout Screen in Primary Human T Cells or NK Cells

This protocol, adapted from successful studies, enables unbiased discovery of genes regulating immune cell function [9] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- sgRNA Library: A lentiviral genome-wide sgRNA library (e.g., 77,736 guides targeting 19,281 genes) [9].

- Cas9 Protein: High-quality, recombinant Cas9 protein.

- Primary Cells: Activated human T cells or NK cells from cord blood or peripheral blood.

- Cell Culture Media: RPMI-1640 supplemented with IL-2 (200 IU/mL) and other necessary cytokines [9].

- Transfection Reagent: Electroporation system (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector).

- Selection Agent: Puromycin for selecting transduced cells.

Methodology:

- Cell Activation & Expansion: Isolate and activate primary T/NK cells using engineered feeder cells or CD3/CD28 antibodies for 3-5 days [9].

- Lentiviral Transduction: On day 5, transduce the activated cells with the sgRNA lentiviral library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure one guide per cell.

- Cas9 Electroporation: 24 hours post-transduction, electroporate cells with Cas9 protein using optimized pulse codes.

- Selection & Expansion: Treat cells with puromycin to select for successfully transduced cells. Re-expand the selected cell population with feeder cells and IL-2.

- Functional Screening: Subject the edited cell pool to your screening condition (e.g., repeated tumor challenge to identify resistance genes) [9].

- NGS & Analysis: After the screen, extract genomic DNA and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the sgRNA region. Compare sgRNA abundance between experimental and control groups to identify hits [9] [27].

Protocol 2: High-Efficiency Knockout in Resting Primary T Cells using RNP Electroporation

This protocol is optimized for hard-to-edit resting primary cells [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- CRISPR Components: Synthetic sgRNA (chemically modified for stability) and Cas9 protein, pre-complexed as an RNP [25] [15].

- Primary Cells: Resting human CD4+ T cells.

- Electroporation Kit: A specialized electroporation kit for primary human T cells.

Methodology:

- Isolate Resting T Cells: Purify CD4+ T cells from healthy donor blood using a negative selection kit.

- Prepare RNP Complex: Pre-complex synthetic sgRNA and Cas9 protein at a optimized molar ratio in a sterile buffer. Incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Electroporation: Mix the RNP complex with the resting T cells and electroporate using a pre-validated program for primary T cells.

- Recovery & Culture: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed, cytokine-rich media. Allow cells to recover for 48-72 hours before analysis.

- Validation: Assess editing efficiency using the T7E1 assay, NGS, or flow cytometry if targeting a surface protein.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

CRISPR Modality Selection Workflow

This diagram outlines a logical decision tree for selecting the appropriate CRISPR modality based on research goals.

DNA Repair Pathways in Primary Cells

This diagram illustrates the competing DNA repair pathways that determine CRISPR outcomes in primary cells, particularly highlighting the differences between dividing and non-dividing cells.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Editing in Primary Cells

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA (Chemically Modified) | A synthetic guide RNA with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) that enhance stability, reduce immune response, and improve editing efficiency [25] [15]. | High-efficiency knockout in sensitive primary T cells and hard-to-transfect cells. |

| Cas9 Protein (WT and High-Fidelity) | The nuclease enzyme that cuts DNA. Available as wild-type for robust cutting and high-fidelity versions (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) for reduced off-target effects [13] [26]. | Pre-complexing with sgRNA to form RNP complexes for electroporation. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | A pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and sgRNA. The preferred delivery format for primary cells due to high efficiency, low toxicity, and short activity window [15]. | All experimental modalities in primary cells, especially for knockouts and when using base editors. |

| Electroporation System | A device that uses electrical pulses to create temporary pores in cell membranes, allowing RNP complexes or other cargo to enter cells efficiently [9] [15]. | Delivery of CRISPR components into primary immune cells (T cells, NK cells). |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered particles that deliver protein cargo (e.g., Cas9 RNP) instead of genomic material. Effective for delivering to difficult cells like neurons [1]. | CRISPR editing in postmitotic primary cells, such as iPSC-derived neurons. |

| Genome-wide sgRNA Library | A pooled lentiviral library containing thousands of sgRNAs targeting every gene in the genome, used for large-scale functional genetic screens [9] [27]. | Unbiased identification of genes regulating primary T cell or NK cell function. |

Within the broader thesis of optimizing CRISPR editing efficiency in primary cell research, the delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes represents a pivotal strategy. RNP delivery offers high editing efficiency with reduced off-target effects and lower cytotoxicity compared to DNA-based methods, making it particularly valuable for sensitive primary cells [29] [15]. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance on two principal RNP delivery approaches: optimized electroporation protocols and emerging hardware-free alternatives, specifically engineered virus-like particles (VLPs) and enveloped delivery vehicles (EDVs).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is RNP delivery often preferred over plasmid DNA for CRISPR editing in primary cells?

RNP delivery offers several advantages for primary cell editing: (1) Immediate activity upon delivery without requiring transcription or translation; (2) Short intracellular half-life that reduces off-target effects; (3) Pre-complexed RNA and protein avoids guide RNA degradation; (4) No risk of genomic integration of foreign DNA; (5) Demonstrated high editing efficiency in challenging primary cell types including T cells and stem cells [29] [15] [30].

Q2: What are the key advantages of hardware-free delivery methods like VLPs/EDVs over electroporation?

Hardware-free methods like VLPs and EDVs provide: (1) Superior cell viability by preserving cell membrane integrity; (2) Up to 30-50-fold higher editing efficiency at comparable RNP doses; (3) Faster editing kinetics with edits occurring at least 2-fold faster; (4) Natural endocytic uptake mechanisms; (5) Ability to target specific cell types through envelope engineering [31] [1] [30].

Q3: How can I troubleshoot low cell viability after electroporation of primary cells?

Low viability can result from: (1) Suboptimal electrical parameters for your specific cell type; (2) Excessive cell concentration during electroporation; (3) Poor RNP quality or excessive dosage; (4) Incorrect post-electroporation handling; (5) Contamination in buffers or reagents. Refer to the troubleshooting table in this guide for specific solutions [32] [33].

Q4: What is the typical timeline for observing CRISPR edits when using different delivery methods?

The editing timeline varies significantly by method: Electroporation typically shows maximal indels within 24-72 hours in dividing cells. EDV delivery demonstrates accelerated editing, with maximal effects occurring approximately 2-fold faster than electroporation. In postmitotic cells like neurons, editing outcomes may continue to accumulate for up to 2 weeks post-delivery regardless of method [1] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Electroporation Troubleshooting

Table 1: Common Electroporation Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Arcing (Electrical Spark) | High salt concentration in RNP preparation; Air bubbles in cuvette; Excessive cell concentration; Impure glycerol in buffers | Desalt DNA/RNP preparations using microcolumn purification; Tap cuvette to remove bubbles; Dilute cell concentration; Use high-purity glycerol [32] [33] |

| Low Editing Efficiency | Suboptimal electrical parameters; Poor cell viability; Insufficient RNP concentration; Incorrect cell type parameters | Optimize voltage and pulse duration using manufacturer guidelines; Use cold cuvettes stored in freezer; Validate RNP quality and concentration; Use cell-type specific buffers [19] [33] |

| Poor Cell Viability | Excessive electrical parameters; High RNP toxicity; Incorrect post-electroporation handling; Cell type sensitivity | Reduce voltage or pulse duration; Titrate RNP to lower concentrations; Use specialized recovery media; Optimize cell density (typically 1x10^6 cells per 100μL) [32] [15] |

| Inconsistent Results Between Experiments | Cuvette age or quality; Variable RNP preparation; Cell passage number or health; Temperature fluctuations | Use fresh cuvettes and check for cracks; Standardize RNP complexing protocol; Use low-passage healthy cells; Pre-chill cuvettes on ice [32] [33] |

Hardware-Free Delivery Troubleshooting

Table 2: VLP/EDV Delivery Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Transduction Efficiency | Suboptimal pseudotyping for target cell type; Insufficient particle concentration; Incorrect storage/handling | Optimize envelope proteins (e.g., VSVG, BRL) for your cell type; Concentrate particles via ultracentrifugation; Avoid freeze-thaw cycles [31] [1] |

| Inadequate Editing Despite High Transduction | Insufficient RNP packaging; Early degradation; Poor endosomal escape | Extend production time to 72h for higher yield; Incorporate endosomolytic agents; Engineer gag-editor fusion proteins [31] [30] |

| Cell Type-Specific Delivery Challenges | Lack of appropriate receptors; Intracellular barriers; Immune recognition | Screen different pseudotyped envelopes; Use targeting motifs (nanobodies, scFvs); Consider immunosuppressants for sensitive cells [1] [30] |

| Manufacturing Inconsistency | Variable transfection efficiency; Unoptimized purification; Plasmid quality issues | Use high-quality plasmid prep methods; Standardize transfection protocols; Implement quality control checks (ELISA, Western) [31] |

Quantitative Comparison of Delivery Methods

Table 3: Performance Metrics of RNP Delivery Methods in Primary Cells

| Parameter | Electroporation | VLP/EDV Delivery | Testing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency | 20-60% in primary T cells [15] | >30-fold higher than electroporation [30] | Comparable total RNP doses |

| Cell Viability | 40-80% (cell type dependent) [15] | >90% in multiple primary cell types [31] [30] | 24-72 hours post-delivery |

| Time to Maximal Editing | 1-3 days (dividing cells) [1] | 2-fold faster than electroporation [30] | Hours to days post-delivery |

| Minimum RNP Required | Variable, typically high doses | >1300 RNPs per nucleus [30] | Measured via fluorescence correlation spectroscopy |

| Duration of Editor Activity | Transient (24-48h) [29] | Transient (24-72h) [31] | Dependent on cell type and delivery efficiency |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate (limited by RNP complexity) | High (multiple gRNAs possible) [31] | Demonstrated with epigenome editors |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized Electroporation for Primary T Cells

This protocol achieves high knockout efficiency in primary human T cells using the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector system [15].

Materials:

- Healthy primary T cells (resting or activated)

- Cas9 protein with nuclear localization signal

- Synthetic sgRNA (chemical modifications recommended)

- Lonza 4D-Nucleofector System with X Unit

- Appropriate cell culture media and supplements

Procedure:

- Isolate and count T cells, ensuring >95% viability.

- Resuspend cells in appropriate nucleofection solution at 1x10^6 cells per 100μL.

- Complex Cas9 protein and sgRNA at 1.5:1 molar ratio in duplex buffer. Incubate 10-15 minutes at room temperature to form RNPs.

- Combine cell suspension with RNP complexes (typically 2-4μg Cas9 per 100μL reaction).

- Transfer to certified cuvettes, ensuring no air bubbles.

- Electroporate using appropriate pulse code (e.g., DS-137 for resting T cells, EO-115 for activated T cells).

- Immediately add pre-warmed recovery media and transfer to culture plates.

- Assess editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-electroporation via flow cytometry or sequencing.

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Cell concentration: 1x10^6 cells per 100μL optimal

- RNP concentration: Titrate between 1-5μg Cas9 per reaction

- Electrical parameters: Cell-type specific codes recommended

- Recovery media: Supplement with IL-2 for T cell viability [15]

Protocol 2: VLP-Mediated RNP Delivery to iPSC-Derived Neurons

This protocol enables efficient RNP delivery to postmitotic cells using engineered virus-like particles, based on the RENDER platform [31] [1].

Materials:

- Lenti-X HEK293T cells for VLP production

- Plasmids: VSV-G envelope, gag-pol polyprotein, gag-editor fusion, sgRNA

- Target cells (iPSC-derived neurons, primary cells)

- Ultracentrifugation equipment

- Cell culture reagents and media

Procedure: VLP Production:

- Seed Lenti-X HEK293T cells in 10cm tissue culture dishes.

- Transfect with plasmid mixture (1μg VSV-G, 6.7μg gag-editor fusion, 3.3μg sgRNA plasmid) using TransIT-LT1.

- Harvest supernatant 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Filter through 0.45μm PES membrane.

- Concentrate via ultracentrifugation through 30% sucrose cushion.

- Resuspend pellet in Opti-MEM, aliquot, and store at -80°C.

Cell Transduction:

- Plate target cells at appropriate density.

- Thaw VLP aliquots quickly and add to cells with appropriate polybrane.

- Centrifuge plates (2000xg, 30-60min, 32°C) to enhance transduction.

- Replace media after 24 hours.

- Assess editing efficiency over 1-2 weeks (especially important for postmitotic cells).

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Production time: Extending to 72h increases yield [31]

- Pseudotyping: VSVG/BRL co-pseudotyping enhances neuronal transduction [1]

- Cell status: Cell cycle synchronization may enhance HDR efficiency [15]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Optimized RNP Delivery

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleofection Systems | Lonza 4D-Nucleofector; Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher) | Electroporation systems with pre-optimized protocols for primary cells [15] [33] |

| Chemically Modified Guides | 2'-O-methyl (M); 2'-O-methyl 3' phosphorothioate (MS); Synthego sgRNA | Enhanced stability and reduced immune activation in primary cells [15] |

| Specialized Buffers | Nucleofection Solution; Electroporation Buffers | Low-conductivity, optimized for specific cell types to enhance viability [33] |

| VLP Production Plasmids | VSV-G envelope; gag-pol; gag-editor fusions | Enable production of engineered VLPs for hardware-free delivery [31] [1] |

| Cell Viability Enhancers | IL-2 for T cells; Rock Inhibitors for stem cells; Specialized recovery media | Improve post-transduction viability, critical for primary cells [15] |

Method Selection Workflow

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of RNP delivery technologies with advanced CRISPR systems continues to expand the possibilities for primary cell research. Recent advances include:

Epigenome Editing: The RENDER platform enables delivery of large CRISPR-based epigenome editors (CRISPRoff, CRISPRi) as RNPs via VLPs, allowing transient delivery for durable epigenetic modifications without DNA breaks [31].

Multiplexed Gene Activation: Second-generation CRISPRa systems (dCas9-VPR) delivered as RNPs enable highly efficient transcriptional activation of endogenous genes, even for deeply silenced developmental genes, with temporal precision unmatched by DNA-based approaches [34].

Therapeutic Applications: Engineered VLPs/EDVs show particular promise for in vivo therapeutic applications, combining the targeting specificity of viral vectors with the safety profile of transient RNP delivery [1] [30].

As these technologies mature, researchers can expect continued improvements in delivery efficiency, cell-type specificity, and applications across diverse primary cell types, further enhancing our ability to model human disease and develop novel therapies.

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting

This guide addresses common experimental challenges in implementing hairpin internal Nuclear Localization Signal (hiNLS) technology to enhance CRISPR-Cas9 editing in primary cells.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our recombinant hiNLS-Cas9 protein yields are low. How can we improve production?

A: This is a common issue when adding multiple NLS tags. The hiNLS strategy was specifically designed to address this.

- Problem: Traditional terminal fusion of multiple NLSs (e.g., 6xNLS) often disrupts protein stability or folding, leading to low recombinant expression yields.

- Solution: The hiNLS approach inserts NLS sequences into surface-exposed loops within the Cas9 backbone, which is better tolerated by the protein's structure. Researchers have reported yields of 4–9 mg per liter for hiNLS-Cas9 variants, which is comparable to unmodified Cas9 and significantly better than terminally tagged multi-NLS constructs [35] [36].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Ensure you are using the correct hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) modules and not simply adding linear NLS sequences to the termini. Check protein expression and purification protocols standard for your Cas9 system.

Q2: We are not observing a significant increase in editing efficiency in primary T cells despite using hiNLS-Cas9. What could be wrong?

A: The delivery method and RNP complex formation are critical.

- Problem: The benefits of enhanced nuclear import are most apparent with transient delivery methods like Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation. If the RNP complex is not properly formed or the delivery is inefficient, you will not see the full effect.

- Solution:

- Always pre-complex the hiNLS-Cas9 protein with your synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA) to form RNPs before delivery [15].

- For primary T cells, electroporation of RNPs is a robust and widely used method. The enhanced nuclear import of hiNLS-Cas9 ensures it reaches the nucleus quickly during the short RNP half-life (1-2 days) [35].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Include a standard NLS-Cas9 control in your experiment. A successful hiNLS-Cas9 test should show a clear improvement over the control. For example, in one study, a hiNLS-Cas9 variant achieved over 80% knockout of the B2M gene in primary T cells, compared to about 66% with traditional Cas9 [36].

Q3: Could adding more NLS motifs increase the risk of off-target editing?

A: There is a potential trade-off between efficiency and specificity.

- Observation: One study noted a slight increase in off-target activity at a known problematic site with hiNLS-Cas9, likely because the improved nuclear localization helps Cas9 remain bound to DNA for longer [36].

- Solution: For applications where off-target effects are a top concern, consider combining the hiNLS strategy with high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9(1.1) or SpCas9-HF1). The core hiNLS strategy can be applied to these engineered variants to create an editor that is both highly efficient and precise [37] [36].

Q4: Is this technology only useful for Cas9, or can it be applied to other editors?

A: The hiNLS strategy is a generalizable concept for improving nuclear import.

- Current Status: The published research demonstrates the principle with CRISPR-Cas9 [35] [38].

- Future Direction: The same rational design strategy—inserting NLS peptides into surface-exposed loops—can be applied to other genome editors like Cas12a, base editors, or prime editors, which face similar nuclear delivery challenges [36]. This is an active area of research.

Experimental Data & Protocols

The following table summarizes key quantitative data from the foundational hiNLS-Cas9 study, providing a benchmark for your experiments.

Table 1: Editing Efficiency of hiNLS-Cas9 in Primary Human T Cells [35] [36]

| Target Gene | Delivery Method | Cas9 Construct | Editing Efficiency | Cell Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2M (Beta-2-microglobulin) | Electroporation | Standard Cas9 (control) | ~66% | Unaffected |

| B2M (Beta-2-microglobulin) | Electroporation | hiNLS-Cas9 (s-M1M4 variant) | >80% | Unaffected |

| B2M (Beta-2-microglobulin) | Peptide-mediated (PERC) | Standard Cas9 (control) | ~38% | Unaffected |

| B2M (Beta-2-microglobulin) | Peptide-mediated (PERC) | hiNLS-Cas9 (multiple variants) | 40-50% | Unaffected |

| TRAC (T-cell receptor alpha constant) | Electroporation | hiNLS-Cas9 variants | Effectively enhanced vs. control | Unaffected |

Key Experimental Protocol: RNP Delivery via Electroporation

This is a generalized protocol for achieving high-efficiency editing in primary T cells using hiNLS-Cas9 RNPs.

RNP Complex Formation:

- Dilute synthetic sgRNA and purified hiNLS-Cas9 protein in a nuclease-free buffer.

- Incubate the sgRNA and protein at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 (sgRNA:Cas9) for 10-20 minutes at room temperature to form the RNP complex [39] [15].

- Note: The optimal ratio may need empirical optimization for your specific gRNA and cell type.

Cell Preparation:

- Isolate primary human T cells from whole blood or a leukopak.

- Activate and expand the T cells for 2-3 days using CD3/CD28 beads and IL-2.

Electroporation:

- Wash and resuspend the T cells in an electroporation-compatible buffer.

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complexes.

- Electroporate using a specialized system (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector). Use a pre-optimized program for primary T cells, such as "EO-115" [15].

Post-Transfection Culture:

- Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells to pre-warmed culture medium supplemented with IL-2.

- Allow the cells to recover and express any edits for at least 48-72 hours before analysis.

Visualizing the hiNLS-Cas9 Workflow and Mechanism

The diagram below illustrates the key experimental workflow for using hiNLS-Cas9 and its fundamental advantage: enhanced nuclear import.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for hiNLS-Cas9 Experiments in Primary Cells

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| hiNLS-Cas9 Protein | Engineered Cas9 nuclease with internal hairpin NLS sequences for superior nuclear import. | Can be produced recombinantly with high yield (4-9 mg/L) [35]. Commercial purified Cas9 proteins with terminal NLS are available, but lack the hiNLS advantage [39]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized guide RNA with specific chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl). | Modified sgRNAs enhance stability and editing efficiency when complexed with Cas9 protein as RNPs [15]. |

| Primary Human T Cells | Target cells for therapeutic genome editing. | Freshly isolated from donors. Highly sensitive to transfection; require specific activation and culture conditions [15]. |

| Electroporation System | Hardware for delivering RNP complexes into cells via electrical pulses. | Systems like the 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza) offer optimized protocols for primary T cells [15]. Gentler methods like peptide-mediated delivery (PERC) also benefit from hiNLS [35] [36]. |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Activation beads (e.g., CD3/CD28) and cytokines (e.g., IL-2). | Essential for maintaining T cell health and proliferation during and after the editing process [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

General Principles and Challenges

Q1: Why is precise knock-in particularly challenging in primary B and T cells compared to cell lines?

Primary B and T cells present unique challenges for CRISPR knock-in due to their biological characteristics. Unlike immortalized cell lines, these primary immune cells often exist in a quiescent state and are non-dividing or slowly dividing, which favors the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway over homology-directed repair (HDR). HDR is naturally restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it inefficient in these cell types [40] [41]. Additionally, certain primary cells like B cells possess elevated levels of DNA repair enzymes that can efficiently repair Cas9-induced double-strand breaks, further reducing knock-in success rates [42] [40].

Q2: What are the key differences between knock-in and knockout experiments that affect experimental design?

Knock-out experiments rely on the error-prone NHEJ pathway, which is active throughout the cell cycle and rapidly repairs double-strand breaks by creating insertions or deletions (indels) that often disrupt gene function. In contrast, knock-in experiments require the HDR pathway, which is only active in dividing cells and uses a donor template to create precise genomic alterations. This fundamental difference makes knock-ins more challenging and requires careful optimization of template design and delivery [43].

Template Design and Selection

Q3: How do I choose between single-stranded oligos and double-stranded DNA templates for my knock-in experiment?

The choice depends primarily on the size of your intended insertion [43]:

- Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs): Optimal for small insertions (<120-150 nucleotides), such as point mutations, epitope tags, or loxP sites. They typically require homology arms of 30-60 nucleotides [44] [43] [40].

- Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates: Necessary for larger insertions such as fluorescent proteins or chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). These can be in the form of PCR products or plasmids and require longer homology arms, typically 200-800 nucleotides, for efficient recombination [44] [43] [40].

Q4: What are the benefits of using a "double-cut" HDR donor design?

A double-cut donor is a linear dsDNA template flanked by sgRNA target sequences that are cleaved by Cas9 in vivo. This design significantly increases HDR efficiency compared to circular plasmid donors because it synchronizes the creation of the genomic double-strand break with donor linearization. This synchronization makes the homologous ends of the donor template more readily available for the repair machinery. Studies in 293T cells and iPSCs have shown that double-cut donors can improve HDR efficiency by twofold to fivefold [45].

Q5: Can chemical modifications to the donor template improve knock-in efficiency?

Yes, chemically modified templates can enhance stability and performance. Modifications such as 5'-phosphorylation and the incorporation of phosphorothioate bonds at the ends can protect donor templates from exonuclease degradation. Recent studies in zebrafish have demonstrated that chemically modified templates outperform those released in vivo from a plasmid, leading to higher rates of precise germline transmission [43] [46].

Enhancing Efficiency and Troubleshooting

Q6: What small molecules can I use to enhance HDR efficiency in primary cells?

Small molecule inhibitors that suppress the NHEJ pathway or synchronize the cell cycle can tilt the balance toward HDR. Several proprietary compounds are available, and research has tested molecules like SCR7 (an NHEJ inhibitor) and nocodazole (a G2/M phase synchronizer). Using nocodazole in combination with CCND1 (cyclin D1), which promotes G1/S transition, has been shown to double HDR efficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells [40] [45].

Q7: How can I prevent re-cutting of the successfully edited locus by Cas9?

Introducing silent mutations into the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) or the seed sequence of the target site in your donor template is an effective strategy. These mutations disrupt the recognition site for the Cas9-sgRNA complex after successful editing, preventing further cleavage and allowing for enrichment of correctly modified cells. This approach is a standard feature in some commercial HDR design tools [43].

Troubleshooting Guide

Low Knock-in Efficiency

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal sgRNA | Test cutting efficiency with a T7E1 assay or NGS; check for predicted off-targets. | Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., IDT's Alt-R HDR Design Tool, CRISPR Design Tool) to design high-efficiency guides. Test 3-5 sgRNAs per target [42] [43]. |

| Inefficient delivery | Measure transfection/electroporation efficiency with a fluorescent reporter. | For hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells, use electroporation (e.g., MaxCyte systems) or optimized lipid nanoparticles. Use stably expressing Cas9 cell lines if possible [42] [47]. |

| Poor template design or delivery | Verify template integrity and concentration post-synthesis. | Optimize homology arm length based on template type. For ssODNs, use 30-60 nt arms; for dsDNA, use 200-800 nt arms. Use double-cut donor design and chemical modifications [44] [43] [40]. |

| Dominant NHEJ pathway | Assess cell cycle status via flow cytometry. | Use HDR enhancers like small molecule NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., nedisertib) or cell cycle synchronizers (e.g., nocodazole) [40] [41] [45]. |

High Cell Toxicity or Poor Viability

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Electroporation stress | Check viability 24-48 hours post-electroporation. | Titrate sgRNA:Cas9 RNP complex amounts. Optimize electroporation parameters (voltage, pulse length). Include electroporation enhancers [43] [47]. |

| Cellular toxicity from CRISPR components | Titrate components individually to identify the toxic element. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants to reduce off-target cuts and genotoxic stress. Purify RNP complexes to remove contaminants [41] [47]. |

| Template toxicity | Co-deliver a fluorescent reporter and sort viable cells. | For plasmid donors, ensure the backbone lacks motifs causing immune activation. Consider using minimalistic templates like "Nanoplasmids" [47]. |

Lack of Functional Knock-in Validation

| Potential Cause | Investigation Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Imprecise integration | Perform Sanger sequencing or long-read sequencing (PacBio) of the target locus. | Use donors with sufficiently long homology arms. Introduce silent mutations to prevent re-cutting. Use HDR-enhancing Cas9 fusions (e.g., miCas9) [43] [41] [46]. |

| Low protein expression | Perform Western blot for the tagged protein or flow cytometry for reporters. | Ensure the insert does not disrupt the reading frame. For tags, verify they are inserted at the correct terminus (N- or C-terminal). Use a 2A peptide linker for larger inserts like fluorescent proteins to ensure proper folding [40] [48]. |

| Inefficient editing in primary cells | Use a control fluorescent reporter knock-in to assess system efficiency. | Activate primary T cells before editing. Use optimized protocols specifically developed for primary human immune cells [40] [47]. |

Experimental Protocol Data Tables

Table 1: Optimized Homology Arm Lengths for Different Template Types

| Template Type | Insert Size | Recommended Homology Arm Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN | < 120 nt | 30 - 60 nt [43] [40] | Chemical modifications (phosphorothioate) improve stability and HDR rates [43]. |

| dsDNA PCR Fragment | 120 - 2000 nt | 200 - 800 nt [40] [45] | Double-cut design with sgRNA flanking sites can boost efficiency 2-5x [45]. |

| Plasmid DNA | > 1000 nt | 500 - 1500 nt (or longer) [44] [45] | Large plasmids are difficult to deliver and can cause toxicity; linearize before use [43] [45]. |

Table 2: HDR Enhancement Strategies and Their Reported Efficacy

| Strategy | Method of Action | Example Reagents/Approaches | Reported Effect on HDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Synchronization | Increases proportion of cells in S/G2 phases where HDR is active. | Nocodazole (G2/M arrest), CCND1/Cyclin D1 (G1/S progression) [45] | Up to 2-fold increase in iPSCs when combined [45]. |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Suppresses competing error-prone repair pathway. | Small molecule inhibitors (e.g., nedisertib, reomidepsin) [40] | Significant increase in HDR-mediated repair in primary B cells [40]. |

| Template Engineering | Increases donor stability and local concentration at the cut site. | Chemical modifications, TFO-tailed ssODN [49], Double-cut donors [45] | TFO-tailed design increased knock-in from ~18% to ~38% [49]. |