Open Science and Materials Informatics: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Sustainable Materials Design

This article explores the powerful convergence of the open science movement and materials informatics, a synergy that is fundamentally reshaping research and development in biomedicine and materials science.

Open Science and Materials Informatics: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Sustainable Materials Design

Abstract

This article explores the powerful convergence of the open science movement and materials informatics, a synergy that is fundamentally reshaping research and development in biomedicine and materials science. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of how open data, collaborative platforms, and FAIR principles are enabling AI-driven discovery. The article covers foundational concepts, practical methodologies for implementation, strategies to overcome common challenges like data sparsity and standardization, and a comparative validation of emerging business models and collaborative initiatives. By synthesizing insights from current initiatives and technologies, it serves as a strategic guide for leveraging open science to accelerate innovation, enhance reproducibility, and tackle pressing global challenges in healthcare and sustainability.

The Paradigm Shift: How Open Science is Redefining Materials Innovation

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the convergence of data-centric research methodologies and the foundational principles of open science. Materials informatics, which applies data analytics and machine learning to accelerate materials discovery and development, is emerging as a critical discipline for addressing global challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare [1] [2]. This paradigm shift moves materials research beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches, enabling the prediction of material properties and the identification of novel compounds through computational means [3].

Open science provides the essential framework for maximizing the impact of materials informatics by ensuring that research outputs—including data, code, and methodologies—are transparent, accessible, and reusable. As defined by the FOSTER Open Science initiative, open science represents "transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks" [4]. This philosophy is particularly vital in materials informatics, where the integration of diverse data sources and computational approaches necessitates unprecedented levels of collaboration and standardization.

This technical guide examines the core principles underpinning the convergence of open science and materials informatics, providing researchers with actionable frameworks for implementing these practices within their workflows. By embracing these principles, the materials research community can accelerate innovation, enhance reproducibility, and ultimately drive the development of next-generation materials for a sustainable future.

Core Open Science Principles in Materials Informatics

The effective integration of open science into materials informatics requires the implementation of several interconnected principles. These principles address the entire research lifecycle, from data generation to publication and collaboration.

FAIR Data Principles

The FAIR Data Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) form the cornerstone of open data practices in materials informatics. Implementing these principles is particularly challenging in materials science due to the diversity of data types, including structural information, property measurements, processing conditions, and computational outputs [5].

Findability: Materials data must be assigned persistent identifiers and rich metadata to enable discovery. Projects such as the OPTIMADE consortium (Open Databases Integration for Materials Design) have developed standardized APIs that provide unified access to multiple materials databases, significantly enhancing findability across resources [3].

Accessibility: Data should be retrievable using standard protocols without unnecessary barriers. The proliferation of open-domain materials databases, such as the Materials Project, AFLOW, and Open Quantum Materials Database, demonstrates the growing commitment to accessibility within the community [3].

Interoperability: Data must integrate with other datasets and workflows through shared formats and vocabularies. The OPTIMADE API specification represents a critical advancement here, providing a common interface for accessing curated materials data across multiple platforms [3].

Reusability: Data should be sufficiently well-described to enable replication and combination in different contexts. This requires detailed metadata capturing experimental conditions, processing parameters, and measurement techniques [6].

Open Computational Workflows

Reproducible computational workflows are essential for advancing materials informatics. The pyiron workflow framework exemplifies this approach, providing an integrated environment for constructing reproducible simulation and data analysis pipelines that are both human-readable and machine-executable [6]. Such platforms enable researchers to document the complete materials design process, from initial calculations through final analysis, ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

The integration of open-source software with these workflows further enhances their utility. Community-driven projects like conda-forge for materials science software distribution facilitate the sharing and deployment of computational tools across different research environments [6].

Collaborative Infrastructure

Open science in materials informatics relies on infrastructure that supports collaboration across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. The OPTIMADE consortium exemplifies this principle, bringing together developers and maintainers of leading materials databases to create and maintain standardized APIs [3]. This collaborative approach has resulted in widespread adoption of the OPTIMADE specifications, providing scientists with unified access to a vast array of materials data.

Similarly, the development of foundation models for materials discovery benefits from collaborative data sharing. These models, which are trained on broad data and adapted to various downstream tasks, require significant volumes of high-quality data to capture the intricate dependencies that influence material properties [7].

Implementing Open Science: Methodologies and Workflows

Integrated Materials Informatics Workflow

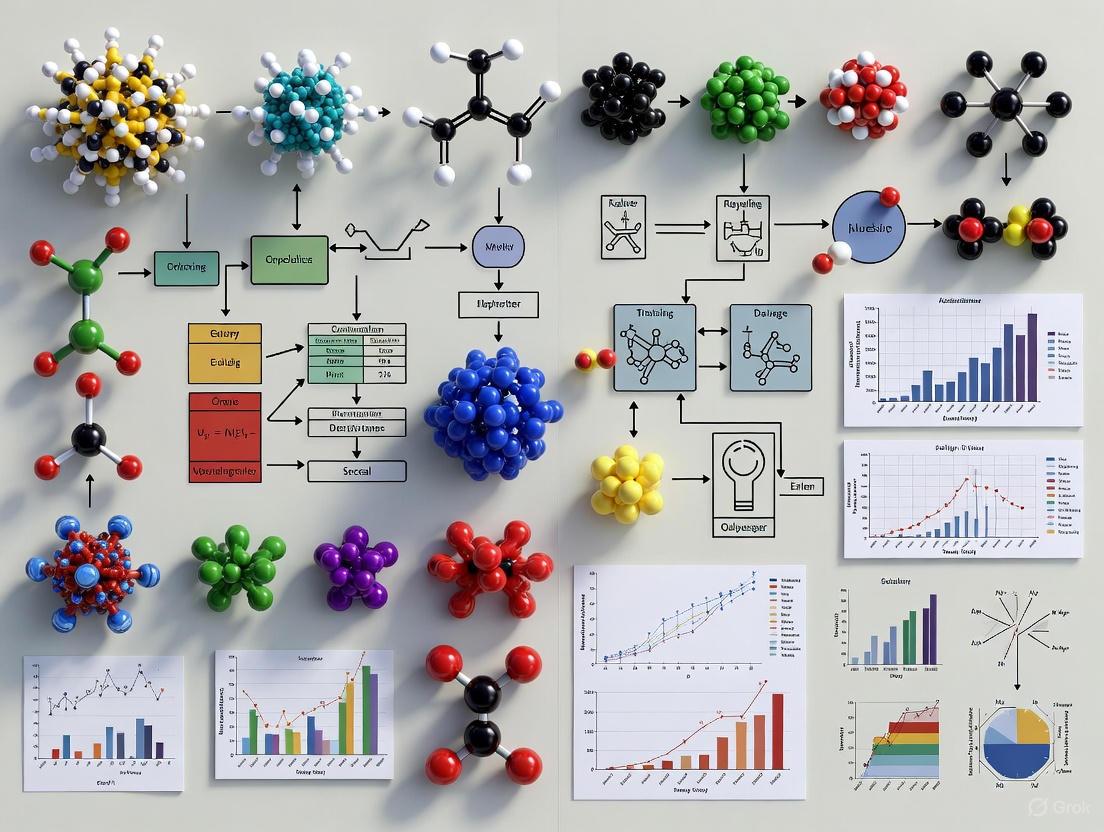

The convergence of open science and materials informatics can be visualized as an iterative cycle that integrates data, computation, and collaboration. The following workflow diagram illustrates this process:

Open Materials Data Workflow illustrates the continuous cycle of open science in materials informatics, beginning with data extraction from open repositories and progressing through AI/ML modeling, validation, and open publication, ultimately feeding back through community collaboration.

Data Extraction and Curation Protocols

The implementation of open science principles begins with robust data extraction and curation. Modern approaches must handle the multimodal nature of materials information, which is embedded not only in text but also in tables, images, and molecular structures [7].

Multimodal Data Extraction: Advanced data extraction pipelines combine traditional named entity recognition (NER) with computer vision approaches such as Vision Transformers and Graph Neural Networks to identify molecular structures from images in scientific documents [7]. Tools like Plot2Spectra demonstrate how specialized algorithms can extract data points from spectroscopy plots, enabling large-scale analysis of material properties [7].

Structured Data Association: The application of large language models (LLMs) has improved the accuracy of property extraction and association from scientific literature. Schema-based extraction approaches enable the structured capture of materials properties and their associations with specific compounds [7].

Standardized Data Representation: The use of community-developed representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) and SELFIES for molecular structures facilitates data exchange and model development [7]. For inorganic solids, graph-based or primitive cell feature representations capture 3D structural information [7].

Open Machine Learning Frameworks

The application of machine learning in materials informatics benefits tremendously from open frameworks and models. Foundation models, pretrained on broad data and adaptable to specific tasks, are particularly promising for property prediction and materials discovery [7].

Table 1: Foundation Model Architectures for Materials Informatics

| Model Type | Architecture | Primary Applications | Key Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-only | BERT-based | Property prediction, materials classification | Generates meaningful representations of input data | [7] |

| Decoder-only | GPT-based | Molecular generation, synthesis planning | Generates new outputs token-by-token | [7] |

| Hybrid | Encoder-decoder | Inverse design, multi-task learning | Combines understanding and generation capabilities | [7] |

The training of these models relies heavily on open chemical databases such as PubChem, ZINC, and ChEMBL, which provide large-scale structured information on materials [7]. However, challenges remain in data quality, with source documents often containing noisy, incomplete, or inconsistent information that can propagate errors into downstream models.

Open Databases and Integration Platforms

The materials informatics landscape features a growing ecosystem of open databases and integration platforms that implement FAIR principles. The OPTIMADE initiative has been particularly successful in addressing the historical fragmentation of materials databases [3].

Table 2: Major Open Materials Databases Supporting Materials Informatics

| Database | Primary Focus | Data Content | Access Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | Inorganic materials | Crystal structures, calculated properties | OPTIMADE API, Web interface | [3] |

| AFLOW | Inorganic compounds | Crystal structures, thermodynamic properties | OPTIMADE API | [3] |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Quantum materials | Phase stability, electronic structure | OPTIMADE API | [3] |

| Crystallography Open Database (COD) | Crystal structures | Experimental crystal structures | OPTIMADE API | [3] |

| Materials Cloud | Computational materials science | Simulation data, workflows | OPTIMADE API | [3] |

These resources collectively enable high-throughput virtual screening of materials by providing access to properties of both existing and hypothetical compounds, significantly reducing reliance on traditional trial-and-error methods [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

The implementation of open science in materials informatics requires a suite of computational tools and platforms that facilitate reproducible research.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Open Materials Informatics

| Tool/Platform | Function | Open Source | Key Capabilities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pyiron | Integrated workflow environment | Yes | Data management, simulation protocols, analysis | [6] |

| OPTIMADE API | Database interoperability | Yes | Unified access to multiple materials databases | [3] |

| Citrine Platform | Materials data management and AI | No (commercial) | Predictive modeling, data infrastructure | [8] |

| optimade-python-tools | API implementation | Yes | Reference implementation for Python servers | [3] |

These tools collectively address the key challenges in materials informatics, including data quality and availability, integration of heterogeneous data sources, and development of interpretable models [8].

Case Studies and Applications

Accelerated CO₂ Capture Material Discovery

A collaborative project between NTT DATA and Italian universities demonstrates the power of open science approaches in addressing climate change. This initiative combined high-performance computing (HPC) with machine learning models to accelerate the discovery of novel molecules for CO₂ capture and conversion [2].

The workflow integrated:

- Generative AI to propose new molecular structures with optimized properties

- High-throughput screening using computational chemistry methods

- Quantum computing frameworks to enhance generative AI performance

- Expert validation by chemistry partners at universities

This approach identified promising molecules for CO₂ catalysis through a systematic, data-driven framework, reducing the experimental timeline significantly compared to traditional methods [2]. The project highlights how open computational frameworks can accelerate materials discovery for critical sustainability challenges.

Development of Sustainable Materials

The Max Planck Institute for Sustainable Materials employs open science principles in its quest to develop sustainable materials. Their Materials Informatics group leverages the pyiron workflow framework to combine experiment, simulation, and machine learning in an integrated environment [6].

Key methodological developments include:

- Uncertainty Propagation for DFT: Quantifying uncertainties in Density Functional Theory calculations resulting from exchange functionals and finite basis sets

- Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIP): Developing approximate interactions between atoms to enable larger-scale simulations

- Statistical Sampling of Chemical Space: Implementing Bayesian approaches to guide efficient sampling and materials discovery

This open, workflow-centric approach enables the reproducible exploration of sustainable material alternatives, with all methodologies documented in human-readable and machine-executable formats [6].

Future Directions and Challenges

The convergence of open science and materials informatics continues to evolve, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges shaping its trajectory.

Foundation models represent a particularly promising direction, with the potential to transform materials discovery through transferable representations learned from large datasets [7]. However, these models face significant challenges, including the dominance of 2D molecular representations that omit 3D conformational information, and the limited availability of large-scale 3D datasets comparable to those available for 2D structures [7].

The development of agentic interfaces to scientific workflow frameworks addresses another critical challenge: the difficulty of consistently generating trustworthy scientific workflows with large language models alone. By allowing LLMs to access and combine predefined, validated interfaces, researchers can maintain scientific rigor while leveraging the power of foundation models [6].

Persistent barriers to adoption include:

- Data Quality and Integration: Challenges related to metadata gaps, semantic ontologies, and data infrastructures, particularly for small datasets [5]

- Cultural and Incentive Structures: The need to align open science practices with career advancement metrics and traditional academic reward systems [4]

- Standardization and Interoperability: Despite progress through initiatives like OPTIMADE, achieving true interoperability across diverse materials data platforms remains challenging [3]

Addressing these challenges will require ongoing collaboration across disciplines and institutions, together with continued development of the open infrastructure that supports transparent, reproducible materials research.

The convergence of open science principles with materials informatics represents a paradigm shift in how materials are discovered, developed, and deployed. By embracing transparency, collaboration, and accessibility, the materials research community can accelerate innovation and address pressing global challenges in sustainability, energy, and healthcare.

The core principles outlined in this guide—FAIR data practices, reproducible computational workflows, and collaborative infrastructure—provide a framework for implementing open science in materials informatics. As the field continues to evolve, these principles will enable more efficient, reproducible, and impactful materials research, ultimately contributing to the development of a more sustainable and technologically advanced society.

The future of materials informatics lies in its openness. By building on the foundations described here, researchers can unlock the full potential of data-driven materials discovery while ensuring that the benefits of this transformation are shared broadly across the scientific community and society at large.

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditionally closed, intuition-driven research models toward collaborative, data-intensive approaches. This paradigm shift represents a fundamental change in how scientific knowledge is created, shared, and applied. Materials informatics—the application of data-centric approaches and artificial intelligence (AI) to materials science research and development—stands at the forefront of this transition, serving as both a driver and beneficiary of evolving open science practices [1] [9]. The emerging approach systematically accumulates and analyzes data with AI technologies, transforming materials development from a process historically reliant on researcher experience and intuition into a more sustainable, efficient, and collaborative methodology [9].

This evolution occurs within a broader context of changing research paradigms. Where traditional "closed" science operated within isolated research groups with limited data sharing, the increasing complexity of modern scientific challenges—particularly in fields like materials science—has necessitated more open, collaborative approaches. The integration of AI and machine learning into the research lifecycle has further accelerated this transition, creating new demands for data sharing, model transparency, and interdisciplinary collaboration [10]. This article traces the historical evolution of open practices in science, with a specific focus on how materials informatics both exemplifies and drives this transformation, ultimately examining the current state of open science in an era increasingly dominated by AI-driven research.

The Historical Trajectory: From Closed Science to Collaborative Frameworks

The Traditional Materials Science Paradigm

Conventional materials development has historically relied heavily on the experience and intuition of researchers, a process that was often person-dependent, time-consuming, and costly [9]. This approach, while responsible for significant historical advances, suffered from several limitations:

- Fragmented Knowledge: Research findings were often siloed within specific research groups or institutions, limiting cumulative progress.

- Reproducibility Challenges: Without access to original data and detailed methodologies, verifying and building upon published research was difficult.

- Inefficient Resource Allocation: The trial-and-error nature of traditional approaches meant significant resources were expended on experimental dead ends.

This paradigm began shifting in the early 21st century with the emergence of materials informatics as a recognized discipline. As noted in a 2005 review, "Seeking structure-property relationships is an accepted paradigm in materials science, yet these relationships are often not linear, and the challenge is to seek patterns among multiple lengthscales and timescales" [11]. This recognition of complexity laid the groundwork for more collaborative, data-driven approaches.

Key Drivers for Open Science in Materials Research

Several interconnected factors have driven the transition toward open science practices in materials informatics:

- Data Intensity: AI and machine learning methods require large, diverse datasets for training effective models, creating inherent pressure toward data sharing and standardization [12].

- Computational Demands: The resources needed to train competitive scientific models are increasing rapidly, making collaboration and resource sharing increasingly necessary [10].

- Interdisciplinary Nature: Materials informatics inherently bridges disciplines—materials science, data science, chemistry, physics—requiring collaboration across traditional academic boundaries [10].

- Economic Efficiency: Open approaches reduce redundant research efforts and accelerate the translation of discoveries to applications, providing economic incentives for collaboration [1].

The Emergence of Open Science Frameworks

Government initiatives worldwide have played crucial roles in accelerating the adoption of open science practices in materials research. These programs have created infrastructure, established standards, and provided funding specifically for open, collaborative approaches.

Table 1: Major Government Initiatives Promoting Open Science in Materials Informatics

| Country/Region | Initiative/Program Name | Key Focus Areas | Impact on Open Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) | Accelerating materials discovery using data and modeling | Directly supports material informatics tools and open databases [13] |

| European Union | Horizon Europe – Advanced Materials 2030 Initiative | Collaborative R&D focusing on digital tools and informatics integration | Backs projects integrating AI, materials modeling, and simulation [13] |

| Japan | MI2I (Materials Integration for Revolutionary Design System) | Integrated materials design using informatics | Government-funded project using informatics for innovation [13] |

| Germany | Fraunhofer Materials Data Space | Creating a structured data ecosystem for materials R&D | National project establishing data sharing infrastructure [13] |

| China | Made in China 2025 – Smart Materials Development | Intelligent materials design using big data and informatics | Prioritizes innovation in smart materials using AI & automation [13] |

| India | NM-ICPS (National Mission on Interdisciplinary Cyber-Physical Systems) | AI, data science, smart manufacturing | Funds AI-based material modeling and computational research [13] |

The Current Landscape of Open Science in Materials Informatics

Foundational Elements of Modern Materials Informatics

Contemporary materials informatics represents the systematic application of data-centric approaches to materials science R&D. The field encompasses several core components that enable open, collaborative research:

- Materials Data Infrastructure: Structured and unstructured datasets containing chemical compositions, properties, and performance metrics of materials, along with tools for collecting, storing, managing, and sharing these datasets [13].

- Machine Learning & AI Algorithms: Models that analyze patterns in materials data to predict properties, discover new materials, and optimize formulations [13] [5].

- Simulation & Modeling Tools: Computational methods used to simulate material behavior and generate synthetic data, increasingly integrated with experimental approaches [13] [9].

- Materials Ontologies & Metadata Standards: Frameworks that ensure consistent labeling, classification, and interpretation of materials data across systems, enabling effective collaboration and data sharing [13].

The primary applications of materials informatics can be broadly categorized into "prediction" and "exploration." The prediction approach involves training machine learning models on existing datasets to forecast material properties, while the exploration approach uses techniques like Bayesian optimization to efficiently discover new materials with desired characteristics [9]. This conceptual framework enables more systematic and shareable research methodologies.

Key Workflows in Materials Informatics

The transformation from closed to collaborative research is exemplified in evolving workflows within materials informatics. The following diagram illustrates a standard machine learning workflow that enables reproducibility and collaboration:

Diagram 1: Standard Materials Informatics Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the iterative, data-driven nature of modern materials research. Particularly important is the feedback loop where knowledge extraction guides new experiments, creating a cumulative research process that benefits from shared data and methodologies [9] [12].

Essential Research Tools and Platforms

The shift to collaborative research has been enabled by the development of specialized tools, platforms, and data repositories that facilitate open science practices. These resources form the infrastructure supporting modern materials informatics.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Materials Informatics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Open Science Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | Materials Project, Protein Data Bank | Provide structured access to materials data | Enable data sharing and reuse; Materials Project provides data for 154,000+ inorganic compounds [10] |

| ML/AI Libraries | Scikit-learn, Deep Tensor | Provide ready-to-use machine learning algorithms | Lower barrier to entry; standardize methodologies across research groups [12] |

| Simulation Tools | MLIPs (Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials) | Accelerate molecular dynamics simulations | Enable high-throughput screening; generate shareable simulation data [9] |

| Platforms & Tools | nanoHUB, GitHub repositories | Host reactive code notebooks and executables | Facilitate methodology sharing and collaboration [12] |

| Standardization Frameworks | FAIR Data Principles, Materials Ontologies | Ensure consistent data interpretation | Enable interoperability between different research systems [10] |

These tools collectively address what the field identifies as "the nuts and bolts of ML" - the essential components required for effective, reproducible, and collaborative research [12]. These include: (1) quality materials data, either computational or experimental; (2) appropriate materials descriptors that effectively represent materials in a dataset; (3) data pre-processing techniques including standardization and normalization; (4) careful selection between supervised and unsupervised learning approaches based on the problem; (5) appropriate ML algorithms matched to data characteristics; and (6) rigorous training, validation, and testing methodologies [12].

Implementation Framework: Methodologies for Collaborative Research

Bayesian Optimization for Materials Exploration

One of the most significant methodologies enabling collaborative materials research is Bayesian optimization, which provides a systematic approach to materials exploration. This method is particularly valuable when data is scarce or when seeking materials with properties that surpass existing ones [9].

The following diagram illustrates the iterative Bayesian optimization process, which efficiently balances exploration of new possibilities with exploitation of existing knowledge:

Diagram 2: Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Materials Discovery

Initial Dataset Preparation:

- Compile existing experimental or computational data containing material descriptors (composition, processing conditions) and corresponding property measurements

- Ensure data quality through normalization and outlier detection

- Divide data into training and validation sets (typically 80/20 split)

Model Training Phase:

- Select appropriate machine learning model (Gaussian Process Regression is commonly used for its uncertainty quantification capabilities)

- Train model on initial dataset to learn relationship between material descriptors and target properties

- Validate model performance using cross-validation techniques

Acquisition Function Calculation:

- Choose acquisition function based on research goals:

- Expected Improvement (EI): Maximizes expected improvement over current best

- Probability of Improvement (PI): Calculates probability of improvement over current best

- Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Balances mean prediction and uncertainty

- Calculate acquisition function values across unexplored material space

- Choose acquisition function based on research goals:

Next Experiment Selection:

- Identify material or processing conditions with highest acquisition function value

- This represents the optimal balance between exploring uncertain regions and exploiting promising areas

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize or process selected material using standardized protocols

- Measure target properties using characterized instrumentation

- Document all experimental parameters for reproducibility

Iterative Refinement:

- Add new experimental results to training dataset

- Retrain model with expanded dataset

- Repeat process until target performance criteria are met or resources exhausted

This methodology dramatically reduces the number of experiments required for materials discovery by strategically selecting each subsequent experiment based on all accumulated knowledge [9]. The explicit uncertainty quantification in Bayesian approaches facilitates collaboration by making prediction confidence transparent.

Feature Engineering and Representation Learning

A critical technical challenge in collaborative materials informatics is representing chemical compounds and structures in formats suitable for machine learning. The methodology for feature engineering has evolved significantly, moving from manual descriptor design to automated representation learning.

Experimental Protocol: Feature Engineering for Materials Informatics

Knowledge-Based Feature Engineering:

- For organic molecules: calculate descriptors including molecular weight, number of substituents, topological indices

- For inorganic materials: compute features based on constituent atomic properties (mean and variance of atomic radii, electronegativity)

- Select feature sets based on domain knowledge and target properties

- Normalize features to ensure comparable scaling across different descriptors

Automated Feature Extraction with Neural Networks:

- Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges

- Implement Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to automatically learn feature representations from molecular structure

- Train GNNs on large datasets to capture complex structure-property relationships

- Extract learned feature representations for use in other ML models

Descriptor Validation:

- Assess feature importance through methods like permutation importance or SHAP analysis

- Evaluate model performance with different feature sets using cross-validation

- Ensure features are generalizable across related material classes

The shift toward automated feature extraction using Graph Neural Networks has been particularly important for open science, as it reduces the dependency on domain-specific expert knowledge for feature design and enables more standardized representations across different material classes [9].

Challenges and Future Directions in Open Materials Science

The Tension Between Industry and Academia

The evolution toward open science faces significant challenges, particularly in the growing dominance of industry in AI research. Current data reveals a troubling trend: according to the Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025, industry developed 55 notable AI models while academia released none [10]. This imbalance stems from industry's control over three critical research elements: computing power, large datasets, and highly skilled researchers.

The migration of AI talent to industry has accelerated dramatically. In 2011, AI PhD graduates in the United States entered industry (40.9%) and academia (41.6%) in roughly equal proportions. By 2022, however, 70.7% chose industry compared to only 20.0% entering academia [10]. This "brain drain" threatens the sustainability of open academic research, as highlighted by Fei-Fei Li's urgent appeal to US President Joe Biden for funding to prevent Silicon Valley from pricing academics out of AI research [10].

This tension creates fundamental conflicts between open science principles and commercial interests. As noted in recent analysis, "Industrial innovators may seek to erect barriers by controlling computing resources and datasets, closing off source code, and making models proprietary to maintain their competitive advantage" [10]. This closed strategy fundamentally conflicts with academia's commitment to public knowledge sharing, potentially slowing the pace of scientific discovery.

Implementing Open Science: Technical and Cultural Barriers

Several significant barriers impede the full realization of open science in materials informatics:

- High Implementation Costs: The financial burden of establishing materials informatics capabilities presents a substantial barrier, particularly for smaller institutions. Costs include software licenses, data acquisition and integration, computational infrastructure, and specialized personnel [13] [14].

- Data Quality and Standardization: Inconsistent data formats, incomplete metadata, and varying quality standards hinder effective data sharing and reuse. Progress depends on "modular, interoperable AI systems, standardised FAIR data, and cross-disciplinary collaboration" [5].

- Cultural Resistance: Traditional academic reward systems often prioritize individual achievement over collaboration, creating disincentives for data sharing and open collaboration.

Emerging Solutions and Future Framework

Despite these challenges, several promising developments are advancing open science in materials informatics:

- Open Science Platforms: Initiatives like the Materials Project platform in materials science have made quantum mechanics calculation datasets accessible for over 154,000 inorganic compounds, supporting global researchers in developing new materials [10].

- FAIR Data Principles: Implementation of Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) data principles is becoming more widespread, facilitating better data sharing practices [10].

- Hybrid AI Models: Approaches that combine traditional interpretable models with black-box AI methods are gaining traction, offering both performance and interpretability [5].

- Materials Informatics Education: Targeted educational initiatives, such as workshops by the Materials Research Society, are systematically training researchers in open science practices and AI/ML methodologies [12].

The future of open science in materials informatics will likely depend on developing new research ecosystems that balance commercial interests with public knowledge benefits. This will require sophisticated policy frameworks that "establish an AI resource base aggregating computing power, scientific datasets, pre-trained models, and software tools tailored to scientific research" [10]. Such infrastructure must be designed to maximize resource discoverability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability for both human researchers and automated systems.

The historical evolution from closed to collaborative practices in science represents a fundamental transformation in how knowledge is created and shared. In materials informatics, this shift has been particularly pronounced, driven by the field's inherent data intensity, computational demands, and interdisciplinary nature. The adoption of open science practices—enabled by standardized workflows, shared data repositories, and collaborative platforms—has dramatically accelerated materials discovery and development.

However, this evolution remains incomplete. The growing dominance of industry in AI research, coupled with persistent technical and cultural barriers, threatens to create new forms of scientific enclosure. Addressing these challenges will require coordinated efforts across academia, industry, and government to develop ecosystems that balance commercial innovation with public knowledge benefits. The future pace of materials discovery—with potential applications ranging from sustainable energy to personalized medicine—will depend significantly on how successfully we navigate this tension between open and closed research models.

As the field continues to evolve, the principles of open science—transparency, reproducibility, and collaboration—will become increasingly central to materials informatics. By embracing these principles while addressing implementation challenges, the research community can accelerate the discovery of materials needed to address pressing global challenges while fostering a more inclusive and efficient scientific ecosystem.

The pharmaceutical industry is grappling with a persistent and systemic research and development (R&D) productivity crisis that has profound implications for its structure and strategy. For over two decades, declining R&D productivity has forced leading companies to adapt their R&D models, influencing both internal capabilities and external innovation strategies [15]. This challenge is particularly pronounced for large pharmaceutical firms, where the scale and capital intensity of R&D activities make productivity a crucial determinant of long-term competitiveness and sustainability. The traditional R&D process remains slow and stage-gated, typically requiring large trials to establish meaningful impact, with failure rates for new drug candidates as high as 90% [16]. The financial implications are significant, with the biopharma industry facing a substantial loss of exclusivity—more than $300 billion in sales at risk through 2030 due to expiring patents on high-revenue products [16].

Simultaneously, materials science is undergoing its own transformation through materials informatics, which applies data-centric approaches to accelerate the discovery and development of new materials. The global materials informatics market is projected to grow from $208.41 million in 2025 to nearly $1,139.45 million by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.80% [14]. This growth is fueled by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and big data analytics to overcome traditional trial-and-error methods that have long constrained materials innovation. The convergence of these fields through digital transformation presents a strategic opportunity to address the shared productivity challenges in both pharma and materials science R&D.

Quantitative Landscape: R&D Performance Metrics

Table 1: Pharmaceutical Industry R&D Productivity Metrics

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Average drug candidate failure rate | Up to 90% | Deloitte 2025 Life Sciences Outlook [16] |

| Sales at risk from patent expiration | >$300 billion | Evaluate World Preview through 2030 [17] |

| Pharma shareholder returns (PwC Index) | 7.6% | PwC analysis from 2018-Nov 2024 [18] |

| S&P 500 shareholder returns (comparison) | 15%+ | PwC analysis from 2018-Nov 2024 [18] |

| Value of AI in biopharma (potential) | Up to 11% of revenue | Deloitte analysis (next 5 years) [16] |

Table 2: Materials Informatics Market and Application Metrics

| Parameter | Value | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global market size (2025) | $208.41 million | Precedence Research [14] |

| Projected market size (2034) | $1,139.45 million | Precedence Research [14] |

| Expected CAGR (2025-2034) | 20.80% | Precedence Research [14] |

| Leading application sector | Chemical Industries | 29.81% market share (2024) [14] |

| Fastest-growing application | Electronics & Semiconductor | Highest CAGR [14] |

| Leading technique | Statistical Analysis | 46.28% market share (2024) [14] |

Table 3: Workforce Productivity Challenges in R&D Organizations

| Metric | Finding | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Employees below productivity targets | 58% of workers | ActivTrak data from 304,083 employees [19] |

| Average daily productivity gap | 54 minutes per employee | Equivalent to 87% output for full salary [19] |

| Annual financial loss per 1,000 employees | $11.2 million | Based on untapped workforce capacity [19] |

Key Driver 1: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are fundamentally transforming R&D approaches across both pharmaceuticals and materials science. In the pharmaceutical sector, AI investments over the next five years could generate up to 11% in value relative to revenue across functional areas, with some medtech companies potentially achieving cost savings of up to 12% of total revenue within two to three years [16]. Generative AI, in particular, is seen as having more transformative potential than previous digital innovations, with the capacity to reduce costs in R&D, streamline back-office operations, and boost individual productivity by embedding AI into existing workflows [16].

In materials informatics, AI and ML enable the acceleration of the "forward" direction of innovation (properties are realized for an input material) and facilitate the idealized "inverse" direction (materials are designed given desired properties) [1]. The advantages of employing advanced machine learning techniques in the R&D process include enhanced screening of candidates and scoping of research areas, reducing the number of experiments needed to develop a new material (and therefore time to market), and discovering new materials or relationships that might not be apparent through traditional methods [1]. The training data for these models can be derived from internal experimental data, computational simulations, and/or external data repositories, with enhanced laboratory informatics and high-throughput experimentation often playing integral roles in successful implementations.

Experimental Protocol: AI-Driven Materials Discovery

Objective: To accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel battery materials using AI-driven predictive modeling.

Materials and Methods:

- Data Collection: Compile terabyte-scale datasets from experimental results, computational simulations, and scientific literature on existing battery chemistries.

- Algorithm Selection: Implement a ensemble of machine learning approaches including deep tensor learning for pattern recognition and digital annealing for optimization problems.

- Model Training: Train predictive models on existing data to forecast material properties such as conductivity, stability, and degradation patterns.

- Virtual Screening: Use trained models to screen thousands of potential electrode material combinations in silico.

- Validation: Synthesize and experimentally test the most promising candidates identified through computational screening.

Expected Outcomes: A case study demonstrated that this approach can reduce discovery cycles from 4 years to under 18 months while lowering R&D costs by 30% through reduced trial-and-error experimentation [14].

AI-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

Key Driver 2: Data Infrastructures and Open Science

The open science movement is creating transformative opportunities for addressing R&D productivity challenges through enhanced data sharing and collaboration. This is particularly relevant in materials informatics, where progress depends on modular, interoperable AI systems, standardized FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data, and cross-disciplinary collaboration [5]. Addressing data quality and integration challenges will resolve issues related to metadata gaps, semantic ontologies, and data infrastructures, especially for small datasets, potentially unlocking transformative advances in fields like nanocomposites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and adaptive materials [5].

The UNESCO-promoted open science movement aims to make scientific research and data more accessible, transparent, and collaborative. This approach is particularly valuable in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where researchers have developed open science policy guidelines to streamline data sharing while ensuring compliance with privacy laws [20]. These initiatives enable open data sharing in global collaborations, furthering knowledge and scientific progress while providing greater research opportunities. By following ethical data-sharing practices and fostering international collaboration, researchers, research assistants, technicians, and research support services can improve the impact of their research and contribute significantly to resolving global health challenges [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Data-Driven R&D

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Driven R&D

| Tool/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis Software | Classical data-driven modeling and hypothesis testing | 46.28% market share in materials informatics techniques [14] |

| Digital Annealer | Optimization and solving complex combinatorial problems | 37.63% market share in materials informatics techniques [14] |

| Deep Tensor Networks | Pattern recognition in complex, high-dimensional data | Fastest-growing technique in materials informatics [14] |

| FAIR Data Repositories | Standardized storage and sharing of research data | Enables open science and collaborative research [5] [20] |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELN) | Digital recording and management of experimental data | Integral to materials informatics data infrastructure [1] |

Key Driver 3: Strategic Portfolio Management and Focus

Pharmaceutical companies are responding to productivity challenges by fundamentally rethinking their R&D and portfolio strategies. Our survey data indicates that 56% of biopharma executives and 50% of medtech executives acknowledge that their organizations need to rethink their R&D and product development strategies over the next 12 months [16]. Nearly 40% of all survey respondents emphasized the importance of improving R&D productivity to counter declining returns across the industry, with many companies exploring a variety of initiatives to enhance their market positions.

The strategic approach to portfolio management is evolving in response to these challenges. PwC outlines four strategic bets that pharmaceutical companies can consider to reshape their business models: Reinvent R&D, Focus to Win, Own the Consumer, and Deliver Solutions [18]. Companies adopting the "Focus to Win" model make bold decisions to exit markets, functions, and categories where they don't have differentiators that provide an economic advantage. They win through capital allocation linked to competitive advantage and are relentless about scaling in selected spots while deprioritizing, exiting, or outsourcing other areas [18]. This approach requires driving continuous process improvement, excelling at sourcing and partnership management, and building in-house functions that are core to differentiators.

Strategic Portfolio Management Approach

Key Driver 4: Advanced Computing and Simulation Technologies

The adoption of advanced computing technologies is accelerating R&D cycles in both pharmaceuticals and materials science. Digital twins, which serve as virtual replicas of patients, allow for early testing of new drug candidates. These simulations can help determine the potential effectiveness of therapies and speed up clinical development [16]. For instance, Sanofi uses digital twins to test novel drug candidates during the early phases of drug development, employing AI programs with improved predictive modeling to shorten R&D time from weeks to hours [16].

In materials science, high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) and computational modeling are revolutionizing materials discovery. These approaches leverage the growing availability of computational power and sophisticated algorithms to screen thousands of potential materials in silico before committing to costly and time-consuming laboratory synthesis and testing. The major classes of projects in materials informatics include materials for a given application, discovery of new materials, and optimization of material processing parameters [1]. These approaches can significantly accelerate the "forward" direction of innovation, where material properties are predicted from input parameters, and gradually enable the more challenging "inverse" design, where materials are designed based on desired properties.

Experimental Protocol: Digital Twin Implementation for Clinical Development

Objective: To use digital twins as virtual replicas of patients for early testing of new drug candidates and accelerating clinical development.

Materials and Methods:

- Patient Data Aggregation: Collect and anonymize multimodal patient data including clinical, genomic, and patient-reported outcomes.

- Model Development: Create computational models that serve as virtual replicas of patient physiology and disease progression.

- In Silico Trials: Simulate drug effects on digital twin populations to predict efficacy and safety profiles.

- Optimization: Use simulation results to refine clinical trial designs, including patient selection criteria and dosage regimens.

- Validation: Compare digital twin predictions with actual clinical trial results to continuously improve model accuracy.

Expected Outcomes: Companies implementing digital twins have demonstrated significant reductions in early-phase drug development timelines, from weeks to hours for certain predictive modeling tasks, while improving the success rates of subsequent clinical trials [16].

Integration Framework: Connecting Open Science with Materials Informatics

The integration of open science principles with materials informatics represents a powerful framework for addressing the R&D productivity crisis. This integration leverages the strengths of both approaches: the collaborative, transparent nature of open science and the data-driven, computational power of materials informatics. Hybrid models that combine traditional computational approaches with AI/ML show excellent results in prediction, simulation, and optimization, offering both speed and interpretability [5]. Progress in this integrated approach depends on modular, interoperable AI systems, standardised FAIR data, and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

The implementation of open science policy guidelines in global research collaborations demonstrates the practical application of this framework. For example, the National Institutes of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE 2) project, a global collaboration led by the University of Edinburgh and Universiti Malaya in partnership with seven LMICs and the UK, developed open science policy guidelines to streamline data sharing while ensuring compliance with privacy laws [20]. This approach enables open data sharing in RESPIRE, furthering knowledge and scientific progress and providing greater research opportunities while addressing the challenges of data security and confidentiality in resource-limited settings.

The R&D productivity crisis in pharma and materials science is being addressed through a multifaceted transformation driven by AI and machine learning, robust data infrastructures and open science, strategic portfolio management, and advanced computing technologies. The convergence of these fields presents significant opportunities for cross-pollination of ideas and methodologies. Pharmaceutical companies can leverage approaches from materials informatics to accelerate drug discovery and development, while materials scientists can adopt open science principles from biomedical research to enhance collaboration and data sharing.

The future outlook for both fields depends on continued investment in digital capabilities, commitment to open science principles, and development of standardized data infrastructures. For pharmaceutical companies, success will require moving beyond initial pilot projects to realize substantial value from adopting AI technologies at scale across the value chain [16]. For materials science, addressing challenges related to data quality, integration, and the high cost of implementation will be essential to unlock the full potential of materials informatics, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises [14]. By embracing these key drivers and fostering greater collaboration between these historically distinct fields, the broader research community can transform the R&D productivity crisis into an opportunity for accelerated innovation and improved human health.

The field of materials informatics is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the convergence of increasing data volumes, sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) methods, and a cultural shift toward collaborative science. This evolution is encapsulated by the open science movement, which posits that scientific knowledge progresses most rapidly when data, tools, and insights are shared freely and efficiently. Within this context, three core pillars have emerged as foundational to modern research: the adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles, the proliferation of robust open-source software tools, and the strategic formation of pre-competitive consortia. These pillars are not isolated trends but are deeply interconnected, collectively enabling researchers to overcome individual limitations and accelerate the discovery and development of new materials, from high-energy-density batteries to targeted therapeutics. This guide examines the individual and synergistic roles of these pillars, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical framework for navigating and contributing to the open science ecosystem in materials informatics.

The FAIR Data Principles: A Framework for Reusability

Defining the FAIR Principles

The FAIR Guiding Principles, formally published in 2016, provide a structured framework to enhance the stewardship of digital assets, with an emphasis on machine-actionability to manage the increasing volume, complexity, and creation speed of data [21]. The core objectives of each principle are:

- Findable: The first step in data reuse is discovery. Data and metadata must be easy to find for both humans and computers. This is achieved through persistent identifiers and rich, machine-readable metadata that are indexed in searchable resources [21] [22].

- Accessible: Once found, users need to understand how data can be accessed. Data should be retrievable using standardized, open protocols, even if the data itself is restricted for privacy or intellectual property reasons [21] [22].

- Interoperable: Data must be ready to be integrated with other data and workflows. This requires the use of common data formats, standards, and controlled vocabularies or ontologies that give shared meaning to the data [21] [22].

- Reusable: The ultimate goal of FAIR is to optimize the future reuse of data. This demands that data are richly described with multiple, relevant attributes, have clear licensing, and include detailed provenance information about its origins and any processing steps [21] [22].

A critical clarification is that FAIR is not synonymous with "Open." Data can be fully FAIR yet access-restricted (e.g., for commercial or privacy reasons), and conversely, open data may lack the rich metadata and provenance to be truly reusable [22].

Implementing FAIR in Practice

Translating the high-level FAIR principles into practice requires specific actions and tools, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: A Practical Checklist for Implementing FAIR Data Principles

| FAIR Principle | Key Implementation Actions | Examples & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Assign a Persistent Identifier (PID); Use rich, standardised metadata schemes. | Digital Object Identifier (DOI); Dublin Core; discipline-specific schemes via FAIRsharing [22]. |

| Accessible | Deposit data in a trusted repository; Ensure metadata is always accessible. | General repositories: Zenodo, Harvard Dataverse; Discipline-specific: re3data.org, FAIRsharing [22]. |

| Interoperable | Use open, community-accepted data formats; Employ controlled vocabularies and ontologies. | Open file formats (e.g., .csv, .cif); Community ontologies (e.g., Pistoia Alliance's Ontologies Mapping project) [22] [23]. |

| Reusable | Create detailed documentation & provenance; Apply a clear, permissive data license. | README files with experimental context; Licenses like CC-0 or CC-BY for public data [22]. |

Multiple large-scale initiatives exemplify the adoption of FAIR in materials and drug development. The Materials Cloud platform provides tools for computational materials scientists to ensure reproducibility and FAIR sharing, including automated provenance tracking via the AiiDA informatics infrastructure [24]. Similarly, the Neurodata Without Borders (NWB) project has created a FAIR data standard and a growing software ecosystem for neurophysiology data, enabling the sharing and analysis of data from the NIH BRAIN Initiative [25]. In the pharmaceutical realm, the Pistoia Alliance's Ontologies Mapping project addresses interoperability by creating a thesaurus to cross-reference different controlled vocabularies, allowing researchers to integrate disparate datasets without losing semantic nuance [23].

Open-Source Tools: The Engine for Computational Research

Open-source tools are the practical engines that bring FAIR data to life, enabling the analysis, visualization, and prediction that drive modern materials informatics. These tools lower the barrier to entry for sophisticated data-driven research and foster a community of continuous improvement and shared best practices.

The following diagram illustrates a typical open-source-informed workflow in materials informatics, from data acquisition to insight generation.

Figure 1: An open-source-enabled workflow for materials informatics research.

Table 2: Essential Open-Source Tools for the Materials Informatics Researcher

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AiiDA [24] | Workflow Management | Automated provenance tracking | Persists and shares complex computational workflows; Ensures reproducibility. |

| Pymatgen [26] | Core Library | Materials analysis & algorithm | Represents materials structures; Interfaces with electronic structure codes. |

| Matminer [26] | Featurization | Materials data visualization | Facilitates data retrieval, featurization, ML, and visualization. |

| DeepChem [26] | Machine Learning | Deep learning for molecules/materials | Supports PyTorch/TensorFlow; Focused on chem- and life-sciences. |

| Jupyter [26] | Development Environment | Interactive computing | De facto standard for interactive, web-based data science prototyping. |

| Crystal Toolkit [26] | Visualization | Interactive visualization | Interactive web app for visualizing materials science data. |

Platforms like the Materials Cloud LEARN section aggregate tutorials, Jupyter notebooks, and virtual machines to train researchers in using these tools effectively, thereby building community capacity [24]. The Awesome Materials Informatics [26] list serves as a community-curated index of a holistic set of tools and best practices, further accelerating onboarding and collaboration.

Pre-Competitive Consortia: Collaborating to Solve Shared Challenges

The Concept and Models of Collaboration

Pre-competitive collaboration is a model where competing companies, often with academic partners, join forces to tackle common, foundational problems that are too large, inefficient, or risky for any single entity to address alone [23]. The core principle is that no single participant gains a direct competitive advantage from the shared output; instead, the entire industry sector moves forward, overcoming operational hurdles and lowering barriers to innovation [23]. These consortia can be classified based on their openness regarding participation and outputs, leading to several distinct models [27].

Table 3: Models of Pre-Competitive Collaboration Based on Participation and Outputs

| Model | Participation | Output Access | Primary Goal | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Source Initiatives [27] | Open | Open | Development of standards, tools, and knowledge. | Linux operating system. |

| Discovery-Enabling Consortia [27] | Restricted | Open | Generate & aggregate data at a scale that enables future innovation. | The Human Genome Project. |

| Public-Private Consortia [27] | Restricted | Open | Create new knowledge within a structured industry-academia framework. | The Innovative Medicines Initiative. |

| Industry Consortia [27] [28] | Restricted | Open or Restricted | Improve non-competitive aspects of R&D; develop common technology platforms. | SEMATECH (semiconductors). |

| Prizes [27] | Open | Restricted | Incentivize the development of a specific product or solution. | X PRIZE. |

Benefits and Implementation in Materials and Pharma

The drive toward pre-competitive collaboration in pharmaceuticals and materials science is fueled by the recognition that major obstacles to accelerating R&D—such as evolving data formats, the need for interoperable standards, and the high cost of foundational tool development—are "simply too large or inefficient to attempt to tackle alone" [23]. The benefits of active participation are multifaceted:

- Shared Cost and Risk: The financial burden and technical risk of developing enabling platforms are distributed among all members [28] [23].

- Access to Broader Expertise: Collaborations bring new minds and perspectives to a problem, leading to more robust and widely applicable solutions than those developed in isolation [23].

- Accelerated Innovation: By providing a common foundation of data, standards, and tools, consortia allow members to focus their proprietary R&D on differentiated, downstream products, thereby speeding overall progress [28] [23].

- Enhanced Reputation and Relationships: The process of collaboration builds morale, opens communication channels, and enhances an organization's standing in the wider research community [23].

The following diagram outlines the strategic process for establishing and running a successful pre-competitive consortium.

Figure 2: The lifecycle and key success factors for a pre-competitive consortium.

Notable examples in action include PUNCH4NFDI, a German consortium in particle and nuclear physics building a federated FAIR science data platform [25], and the Materials Research Data Alliance (MaRDA), which is building a sustainable community to promote open and interoperable data in materials science [25]. A key challenge in the current landscape is "alliance fatigue," with a proliferation of groups competing for membership and funding. Initiatives like the Pistoia Alliance's "Map of Alliances" are emerging to bring clarity and efficiency to the collaboration ecosystem [23].

Synergistic Integration: Accelerating Discovery Through Interconnected Pillars

The true power of FAIR data, open-source tools, and pre-competitive consortia is revealed not when they operate in isolation, but when they integrate synergistically to create a virtuous cycle of innovation. This integration forms the backbone of the modern open science movement in materials informatics.

Consortia produce FAIR data and open tools: Pre-competitive collaborations are a primary mechanism for generating the community-wide standards, ontologies, and shared datasets that embody FAIR principles. For instance, the ESCAPE project in Europe involves major astronomy and physics facilities working to make their data and software interoperable and open, directly contributing to the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) [25]. Similarly, the FAIR for AI initiatives, such as those led by the DOE, aim to create commodity, generic tools for managing AI models and datasets that can then be specialized across different scientific fields [25].

Open tools enable data to become FAIR: Tools like AiiDA from the Materials Cloud initiative are critical for implementing FAIR principles from the beginning of a research project. By automating provenance tracking during computation, they ensure that data is not only reusable but also reproducible, a level of rigor that is difficult to achieve by applying FAIR principles only after data collection is complete [24].

FAIR data empowers consortia and tools: When data generated by consortia is FAIR, it dramatically increases the value and utility of that data for all members. It also creates a robust foundation upon which open-source tools can be built and validated. The Neurodata Without Borders (NWB) standard provides a clear example: by defining a FAIR data standard for neurophysiology, it has spurred the growth of a software ecosystem that allows researchers to share and build common analysis tools [25].

This synergistic relationship establishes a powerful flywheel effect. Collaborative consortia create the demand and frameworks for shared standards, which are implemented through open-source tools. These tools, in turn, make it easier for researchers to produce and use FAIR data, which attracts more participants to the consortia and incentivizes further investment in tool development. This cycle continuously elevates the entire field's capacity for efficient, reproducible, and accelerated discovery.

The paradigm for materials informatics and drug development is decisively shifting from isolated, proprietary efforts to a collaborative, open science model. This transition is structurally supported by the three core pillars of FAIR data, open-source tools, and pre-competitive consortia. Individually, each pillar addresses a critical weakness in traditional R&D: FAIR data ensures the longevity and reusability of research outputs; open-source tools provide the accessible, scalable infrastructure for analysis; and pre-competitive consortia offer a viable model for sharing the cost and burden of foundational work. Together, they create a synergistic ecosystem that accelerates the entire innovation lifecycle. For researchers and professionals, engaging with these pillars—by adopting FAIR practices, contributing to open-source projects, and participating in strategic consortia—is no longer merely an option but an essential strategy for maintaining relevance and driving impact in the rapidly evolving landscape of materials science and biomedical research.

Building the Engine: Open Data Infrastructures and AI-Driven Workflows

The open science movement is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of materials informatics research, promoting transparency, reproducibility, and collaborative acceleration. Central to this paradigm shift are open data repositories, which serve as communal vaults for scientific data. However, the true potential of these resources is only unlocked through the implementation of robust, standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) that ensure interoperability and machine actionability. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three pivotal resources: the OPTIMADE API standard, the Crystallography Open Database (COD), and PubChem. Each plays a distinct yet complementary role in the materials and chemistry data ecosystem. OPTIMADE offers a unified query language for disparate materials databases, the COD provides a community-curated collection of crystal structures, and PubChem serves as a comprehensive repository for chemical information. Framed within the broader context of open science, this whitepaper details their operational protocols, technical architectures, and practical applications, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage these powerful tools for data-driven discovery.

Core Characteristics

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of the three repositories, highlighting their primary focus, data licensing, and access models.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of OPTIMADE, COD, and PubChem

| Feature | OPTIMADE | Crystallography Open Database (COD) | PubChem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Universal API specification for materials database interoperability [29] [30] | Open-access collection of crystal structures [31] [32] | Open chemistry database of chemical substances and their biological activities [33] |

| Data License | (Varies by implementing database) | CC0 (Public Domain Dedication) [34] | Open Access [33] |

| Access Cost | Free | Free [34] | Free [33] |

| Governance | Consortium (Materials-Consortia) [29] [35] | Vilnius University - Biotechnology Institute [34] | National Institutes of Health (NIH) [33] |

| Primary Data Format | JSON:API [30] | Crystallographic Information File (CIF) [34] [32] | PubChem Standard Tags, various chemical structure formats [33] |

Technical Specifications and Scale

This table contrasts the technical implementation, scale, and supported data types for each resource, providing a clear view of their capabilities and scope.

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Scale

| Specification | OPTIMADE | Crystallography Open Database (COD) | PubChem |

|---|---|---|---|

| API Type | RESTful API adhering to JSON:API specification [30] | REST API available [34] | Web interface, programmatic services, and FTP [33] |

| Query Language | Custom filter language for materials data [30] | Textual and COD ID searches via web interface and plugins [31] | Search by name, formula, structure, and other identifiers [33] |

| Supported Data Types | Crystal structures and associated properties [36] | Small molecule and medium-sized unit cell crystal structures [32] | Small molecules, nucleotides, carbohydrates, lipids, peptides [33] |

| Scale (as of 2024) | 25 databases, >22 million structures [36] | >520,000 entries [32] | Not specified in results; world's largest collection per provider [33] |

| Versioning | Semantic Versioning [30] | Supported [34] | Not supported [33] |

In-Depth Repository Profiles

OPTIMADE: The Interoperability Standard

OPTIMADE (Open Databases Integration for Materials Design) is a consortium-driven initiative that has developed a universal API specification to make diverse materials databases interoperable [29]. Its core motivation is to overcome the fragmentation of materials data, where each database historically had its own specialized, often esoteric, API, making unified data retrieval difficult and necessitating significant maintenance effort for client software [30]. The OPTIMADE API is designed as a RESTful API with responses adhering to the JSON:API specification. It employs a sophisticated filter language that allows intuitive querying based on well-defined material properties, such as chemical_formula_reduced or elements [30]. A key feature is its use of Semantic Versioning to ensure stable and predictable evolution of the specification [30]. The consortium maintains a providers dashboard listing all implementing databases, which include major computational materials databases like AFLOW and the Materials Project [29] [30]. As of 2024, the API is supported by 22 providers offering over 22 million crystal structures, demonstrating significant adoption within the materials science community [36].

Crystallography Open Database (COD)

The Crystallography Open Database is an open-access, community-built repository of crystal structures [32]. Established in 2003, it has grown to over 520,000 entries as of 2024, containing published and unpublished structures of small molecules and small to medium-sized unit cell crystals [31] [32]. A defining feature of the COD is its use of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication license, which removes legal barriers to data reuse and facilitates integration into other databases and software [34]. The primary data format is the Crystallographic Information File (CIF), as defined by the International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) [32]. The COD is widely integrated into commercial and academic software for phase analysis and powder diffraction, such as tools from Bruker, Malvern Panalytical, and Rigaku, which distribute compiled, COD-derived search-match databases for their users [31]. This extensive integration makes it a foundational resource for experimental crystallography. The database also provides an SQL interface for advanced querying and offers structure previews using JSmol for visualization [31] [32].

PubChem

PubChem, maintained by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is the world's largest collection of freely accessible chemical information [33]. It functions as a comprehensive resource for chemical data, aggregating information on chemical structures, identifiers, physical and chemical properties, biological activities, safety, toxicity, patents, and literature citations [33]. While its primary focus extends beyond solid-state materials, it is an indispensable tool for drug development professionals and chemists. PubChem mostly contains data on small molecules, but also includes larger molecules like nucleotides, carbohydrates, lipids, and peptides [33]. Access is provided through a user-friendly web interface as well as robust programmatic access services, allowing for automated data retrieval and integration into computational workflows [33]. Its role in the open science ecosystem is to provide a central, authoritative source for chemical data that bridges the gap between molecular structure and biological activity.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Querying Multiple Databases via the OPTIMADE API

This protocol details the methodology for performing a unified query across multiple OPTIMADE-compliant databases to retrieve crystal structures of a specific material, such as SiO₂. This process exemplifies the power of standardization in materials informatics.

Identify Base URLs: Obtain the base URLs of OPTIMADE API implementations from the official providers dashboard [29]. For example:

- AFLOW:

https://aflow.org/optimade/ - Materials Project:

https://optimade.materialsproject.org/ - COD:

https://www.crystallography.net/optimade/

- AFLOW:

Construct the Query Filter: Use the OPTIMADE filter language to formulate the query. To find all structures with a reduced chemical formula of SiO₂, the filter string is:

filter=chemical_formula_reduced="O2Si"[30]. The filter language supports a wide range of properties, includingelements,nelements,lattice_vectors, andband_gap.Execute the HTTP Request: Send a GET request to the

/v1/structuresendpoint for each base URL, appending the filter. For instance, a full request to the Materials Project would look like:GET https://optimade.materialsproject.org/v1/structures?filter=chemical_formula_reduced="O2Si"[30]. TheAcceptheader should be set toapplication/vnd.api+json.Handle the Response: The API returns a JSON:API-compliant response. A successful response (HTTP 200) will contain the requested structures in a standardized

dataarray, with each entry containing attributes likelattice_vectors,cartesian_site_positions, andspecies[30].Parse and Compare Results: Extract the relevant structural properties from the response of each database. The standardized output format allows for direct comparison of structures and properties retrieved from different sources, enabling meta-analyses and dataset validation.

Protocol: Phase Identification Using COD Data

This methodology describes the use of COD data within powder diffraction software for phase identification, a common experimental task in materials characterization.

Data Acquisition: Acquire a powder diffraction pattern from the sample material using an X-ray diffractometer.

Import and Preprocess: Import the measured raw data (e.g., a STOE raw file) into a compatible search-match program like Search/Match2 or HighScore [31]. Apply necessary corrections for background, absorption, and detector dead time.

Load COD Database: Ensure the compiled COD-derived search-match database is loaded into the software. These are often provided directly by the software vendors (Bruker, Malvern Panalytical, Rigaku) and are optimized for rapid searching [31].

Perform Search/Match: Execute the search-match algorithm. Modern software uses powerful probabilistic (e.g., Bayesian) algorithms to search the entire COD (over a million entries including predicted patterns) in seconds, ranking potential matching phases by probability [31].

Validate with Full Pattern Fitting: To check the plausibility of the search-match results, perform a full pattern fitting (Rietveld method) using the candidate phases identified from the COD. This step confirms the phase identification and can provide quantitative information [31].

Figure 1: COD Phase Identification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key software tools, libraries, and resources that are essential for effectively working with these open data repositories.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Open Data Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| optimade-python-tools [29] | A Python library for serving and consuming materials data via OPTIMADE APIs. | Simplifies the process of creating an OPTIMADE-compliant server or building a client to query multiple OPTIMADE databases. |