NGS Validation of CRISPR Editing Efficiency: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for validating CRISPR editing efficiency.

NGS Validation of CRISPR Editing Efficiency: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for validating CRISPR editing efficiency. It covers foundational principles, establishing NGS workflows from library preparation to data analysis, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and comparing NGS performance against alternative methods like T7E1, TIDE, and ICE. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging innovations, this resource aims to empower scientists with the knowledge to implement robust, quantitative validation strategies essential for reliable genetic research and therapeutic development.

Why NGS is the Gold Standard for CRISPR Validation

The Critical Role of Validation in CRISPR Workflows

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise genome editing across diverse biological systems. However, the inherent variability in editing outcomes—including heterogeneous insertion/deletion profiles (indels) and potential off-target effects—poses significant challenges for research reproducibility and therapeutic safety. Consequently, robust validation has become a non-negotiable cornerstone of the CRISPR workflow. This guide objectively compares the performance of key validation methodologies, framing the discussion within the critical context of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) as the foundational standard for accuracy in CRISPR research and development.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Validation Methods

The choice of validation method directly impacts the reliability and depth of editing efficiency data. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance metrics, and ideal use cases for the most common techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary CRISPR Analysis Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Workflow Complexity | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [1] [2] | High-throughput sequencing of PCR-amplified target loci; provides base-resolution data on indel spectra. | Considered the gold standard; high sensitivity and accuracy; enables detection of large deletions and complex rearrangements [3] [2]. | High; requires DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis [1]. | Definitive validation for publication and therapeutics; quantifying complex editing outcomes; single-cell resolution analysis [3]. |

| Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) [1] | Computational deconvolution of Sanger sequencing traces from edited cell pools to infer indel mixtures. | High correlation with NGS (R² = 0.96); provides an ICE score (indel frequency) and a Knockout Score [1]. | Medium; relies on standard Sanger sequencing followed by web-based analysis. | High-throughput screening; labs seeking NGS-level accuracy with Sanger sequencing cost and speed [1]. |

| Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) [1] [2] | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing chromatograms to estimate indel frequencies and types. | Accurately predicts overall sgRNA activity in cell pools; can miscall specific alleles in cloned cells [2]. | Medium; standard Sanger sequencing with web-based decomposition. | Rapid assessment of editing efficiency during sgRNA optimization; less ideal for clonal analysis [1]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay [1] [2] | Enzyme-based cleavage of heteroduplex DNA formed by re-annealing wild-type and mutant PCR amplicons. | Low dynamic range; often underestimates high efficiency and misses low efficiency editing; qualitative rather than quantitative [2]. | Low; involves PCR, heteroduplex formation, enzyme digestion, and gel electrophoresis [1]. | Low-cost, fast initial check during protocol development where sequence-level data is not required [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Methods

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

This protocol is designed to provide a comprehensive, quantitative analysis of CRISPR editing outcomes in a pooled cell population [2].

- Step 1: Genomic DNA Extraction. Harvest cells 3-4 days post-transfection or transduction. Isolate genomic DNA using a standard purification kit [2].

- Step 2: PCR Amplification. Design primers flanking the on-target site to generate an amplicon of suitable length for your sequencing platform (e.g., ~300-500 bp for Illumina MiSeq). Use a high-fidelity polymerase to minimize PCR errors [2].

- Step 3: NGS Library Preparation. Attach dual-indexed sequencing adapters to the purified PCR amplicons via a second, limited-cycle PCR. This step creates the tailed library ready for sequencing [2].

- Step 4: Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis. Pool libraries and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., 2x250 bp on Illumina MiSeq). Process the raw data: demultiplex samples, align reads to the reference genome, and use specialized tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to quantify the spectrum and frequency of indels [2].

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay

A mismatch cleavage assay used for a rapid, though less quantitative, assessment of nuclease activity [1] [2].

- Step 1: PCR Amplification. Amplify the target region from the purified genomic DNA [2].

- Step 2: DNA Denaturation and Re-Annealing. Purify the PCR product. Denature it at 95°C for 10 minutes, then slowly cool to room temperature (ramp rate of ~0.1°C/sec) to allow formation of heteroduplexes between wild-type and mutant DNA strands [2].

- Step 3: T7E1 Digestion. Incubate the re-annealed DNA with T7 Endonuclease I enzyme at 37°C for 15-60 minutes. The enzyme cleaves DNA at the mismatch sites in heteroduplexes [2].

- Step 4: Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis. Resolve the digestion products via agarose gel electrophoresis. Compare the banding pattern to an undigested control. Editing efficiency can be estimated using densitometry with the formula: % Indel = 100 × (1 - [1 - (b+c)/(a+b+c)]^1/2), where

ais the integrated intensity of the undigested PCR product, andbandcare the intensities of the cleavage products [2].

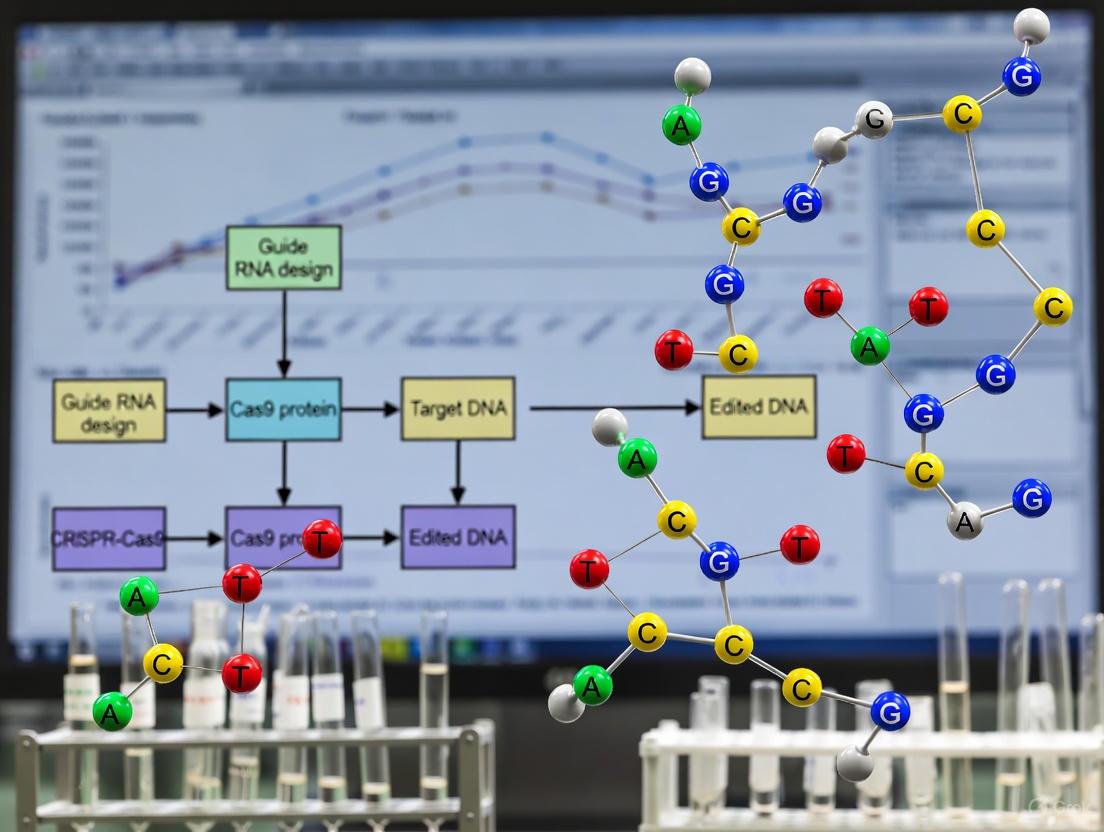

Visualizing CRISPR Validation Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and steps involved in the two primary validation pathways: the comprehensive NGS workflow and the rapid T7E1 assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

Successful execution of CRISPR validation experiments relies on a foundation of high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the target genomic locus for all PCR-based methods with minimal errors. | Critical for NGS to prevent false positives from PCR artifacts; ensures accurate representation of indel spectra [2]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Facilitates the attachment of platform-specific adapters and barcodes to PCR amplicons. | Choose kits optimized for amplicon sequencing; efficiency impacts final library complexity and sequencing depth [2]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Recognizes and cleaves mismatched DNA in heteroduplexes for the T7E1 assay. | Enzyme activity and buffer conditions can affect cleavage efficiency and background noise [2]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., CRISPResso2, ICE) | Analyzes sequencing data to quantify editing efficiency, indel distribution, and potential off-target events. | Tool selection dictates the accuracy and depth of analysis; some require command-line expertise while others offer web interfaces [1] [4]. |

| Validated sgRNA | Directs the Cas9 nuclease to the specific genomic target site. | Activity is a primary variable; must be validated itself. Tools like DeepCRISPR use AI to predict high-efficacy guides [4]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Executes the double-strand break at the DNA target site. | Options include plasmid DNA, mRNA, or recombinant protein (RNP); delivery method influences on-target efficiency and off-target rates [5] [6]. |

Validation is the critical link between CRISPR experimental design and reliable, interpretable results. While traditional methods like the T7E1 assay offer speed and low cost for initial screens, their limitations in quantitative accuracy and resolution are well-documented [2]. For rigorous research and any clinical application, NGS provides the unparalleled depth and sensitivity required to fully characterize the complex landscape of CRISPR editing outcomes, from precise indel quantification to the detection of large deletions and off-target effects [3] [2]. The evolving toolkit, augmented by AI-powered design and analysis tools like DeepCRISPR and ICE, empowers researchers to implement these robust validation frameworks, thereby ensuring the integrity and safety of their genome engineering efforts [1] [4].

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise modifications across diverse biological systems. However, the full potential of this technology can only be realized with equally advanced validation methodologies. Within the context of CRISPR editing efficiency research, the analytical platform used for validation becomes paramount. Traditional methods, while historically valuable, present significant limitations in comprehensiveness and quantitative precision. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a powerful alternative, providing unprecedented depth and accuracy in characterizing editing outcomes. This guide objectively compares the performance of NGS with traditional validation techniques, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data necessary to select the optimal analytical platform for their CRISPR validation workflows.

Comparative Performance: NGS vs. Traditional Methods

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Efficiency

A critical study directly comparing the T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay—a traditional validation method—with targeted NGS for assessing CRISPR-Cas9 editing at 19 genomic loci revealed striking differences in performance [2]. The research demonstrated that the T7E1 assay consistently underestimated editing efficiency, reporting an average indel frequency of just 22% across all tested guide RNAs. In stark contrast, targeted NGS detected a much higher average efficiency of 68%, with nine individual sgRNAs yielding indel frequencies exceeding 70% [2]. This discrepancy is quantified in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Editing Efficiency Detection Between T7E1 and Targeted NGS

| sgRNA Group | Average Efficiency by T7E1 | Average Efficiency by NGS | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human (H1-H9) | 22% | 68% | 46% |

| Mouse (M1-M10) | 22% | 68% | 46% |

| Overall Average | 22% | 68% | 46% |

The limitations of traditional methods extend beyond simple underestimation. The same study found that sgRNAs with apparently similar activity by T7E1 (e.g., M2 and M6, both at ~28%) proved dramatically different by NGS, with actual efficiencies of 92% and 40%, respectively [2]. This low dynamic range and requirement for DNA heteroduplex formation fundamentally limit the reliability of traditional assays for accurately quantifying CRISPR editing efficiency.

Comprehensive Mutation Spectrum Analysis

Beyond simple efficiency quantification, NGS provides a comprehensive view of the entire mutation spectrum, including precise indel characterization, which is largely inaccessible to traditional methods. While techniques like T7E1 and TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) can indicate that editing has occurred, they struggle to accurately identify the specific sequences of the resulting alleles, particularly in complex editing scenarios [2].

Targeted NGS enables researchers to simultaneously detect a wide range of editing outcomes, from single-nucleotide changes to large deletions and complex rearrangements. This capability is crucial for thorough characterization of CRISPR experiments, as it reveals the full heterogeneity of editing products within a cell population. Furthermore, NGS can be applied to analyze thousands of samples in parallel through multiplexing, enabling high-throughput screening of CRISPR libraries that is simply not feasible with traditional methods [7] [8].

Table 2: Capability Comparison Between Traditional Methods and NGS

| Analysis Capability | T7E1 Assay | TIDE/IDAA | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Efficiency | Limited (underreports) | Moderate | High accuracy |

| Identifies Specific Indels | No | Partial (size only) | Yes (exact sequence) |

| Detects Complex Rearrangements | No | No | Yes |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low | Low | High (1000s of samples) |

| Sensitivity for Rare Variants | Low | Low | High (<1%) |

Experimental Applications and Protocols

NGS Workflow for CRISPR Validation

The application of NGS for CRISPR editing validation typically follows a targeted amplicon sequencing approach. This method focuses sequencing power on specific genomic regions of interest, providing deep coverage to detect even rare editing events with high confidence [8]. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: NGS Workflow for CRISPR Validation. This diagram illustrates the key steps in preparing and analyzing CRISPR-edited samples using targeted next-generation sequencing, from initial DNA extraction to final computational analysis.

Detailed Protocol for Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

Step 1: Primer Design - Design gene-specific primers flanking the CRISPR target site, ensuring the amplicon size is appropriate for the sequencing platform (typically <450bp for Illumina). Add partial Illumina adapter sequences to the 5' ends: Forward DS tag: 5'-CTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3' and Reverse DS tag: 5'-CAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3' [8].

Step 2: PCR Amplification (Step 1) - Perform the first PCR using primers with partial adapters to amplify the target region from genomic DNA. The target modification site should be positioned close to the center of the amplicon with primers binding at least 50bp away from the cut site [8].

Step 3: Indexing PCR (Step 2) - Use the initial PCR product as a template for a second PCR with indexing primers that add unique sample barcodes and complete Illumina adapter sequences. This enables multiplexing of numerous samples in a single sequencing run [8].

Step 4: Sequencing and Analysis - Pool the indexed libraries and sequence on an appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq). Analyze the resulting FASTQ files using specialized tools like CRIS.py, which automatically quantifies editing efficiency and characterizes specific indel patterns [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for NGS-based CRISPR Validation

| Item | Function | Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target region with minimal errors | Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplicons for sequencing | Illumina-compatible kits |

| Indexing Primers | Adds unique barcodes for sample multiplexing | Illumina i5/i7 index sets |

| NGS Platform | Generates sequence data | Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq |

| CRIS.py Software | Analyzes NGS data for editing outcomes | Python-based, processes FASTQ files |

| Genomic DNA Isolation Reagents | Extracts high-quality DNA from edited cells | Proteinase K-based extraction buffers |

Case Studies in Method Performance

Validation of AI-Designed CRISPR Editors

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have enabled the design of novel CRISPR-Cas proteins with minimal sequence similarity to natural systems. The characterization of these AI-generated editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, relies heavily on NGS for validation [9]. In one landmark study, researchers used NGS to demonstrate that OpenCRISPR-1, despite being "400 mutations away" from SpCas9 in sequence space, achieved comparable or improved editing efficiency and specificity [9]. This level of precise quantification and specificity assessment would be challenging with traditional methods, highlighting NGS's critical role in validating next-generation genome editing tools.

High-Throughput Functional Genomics

The application of NGS in CRISPR screening has enabled systematic interrogation of gene function at an unprecedented scale. Recent research has focused on optimizing guide RNA design and library size to improve screening efficiency. One study demonstrated that minimal genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 libraries designed using principled criteria and validated by NGS performed as well or better than larger conventional libraries while reducing costs and increasing feasibility for complex models like organoids and in vivo systems [7]. The quantitative precision of NGS was essential for determining that libraries with fewer guides per gene could maintain sensitivity while dramatically improving scalability.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The comprehensive comparison presented in this guide clearly demonstrates the superiority of NGS over traditional methods for validating CRISPR editing efficiency. The quantitative precision, comprehensive mutation profiling, and scalability of NGS make it an indispensable tool for researchers requiring accurate characterization of editing outcomes. While traditional methods like T7E1 may still serve as rapid preliminary checks, their technical limitations—particularly in underestimating efficiency and failing to characterize the full spectrum of edits—render them inadequate for rigorous scientific research and therapeutic development.

Looking forward, the integration of NGS with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and long-read sequencing will further enhance CRISPR validation capabilities. AI-designed editors [9] and advanced screening approaches [7] already rely on NGS for characterization, and this synergy will likely strengthen as the field progresses. For researchers and drug development professionals, investing in NGS-based validation workflows represents not merely a methodological upgrade, but a fundamental requirement for generating robust, reproducible, and clinically relevant data in the genome editing era.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable technology in the validation of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, providing researchers with powerful tools to assess editing efficiency, specificity, and safety. As CRISPR applications advance toward clinical therapies, rigorous evaluation of editing outcomes becomes increasingly critical. NGS offers the precision and depth required to characterize intended edits while identifying unintended consequences that could compromise therapeutic safety. This guide examines the key NGS applications in CRISPR validation—genotyping, off-target detection, and large-scale screening—comparing methodological approaches, their performance characteristics, and appropriate contexts for implementation within drug development and research workflows.

NGS for CRISPR Genotyping: Verifying On-Target Edits

CRISPR genotyping with NGS provides a comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes at the intended target site, offering significant advantages over traditional methods like T7E1 mismatch assays or Sanger sequencing with TIDE/ICE analysis [10] [11]. While these conventional methods provide initial efficiency estimates, NGS delivers precise quantification and full characterization of insertion/deletion (indel) profiles.

Amplicon sequencing represents the most common NGS approach for genotyping, where the genomic region surrounding the target site is PCR-amplified, barcoded, and sequenced at high depth [12]. This method enables researchers to:

- Precisely quantify editing efficiency by calculating the percentage of reads containing indels at the target site

- Characterize the complete spectrum of indel sequences and their relative frequencies

- Detect low-frequency editing events with sensitivity to alleles present at <1% frequency [13]

- Determine zygosity of edits when analyzing clonal populations

- Simultaneously assess homology-directed repair (HDR) efficiency when a donor template is provided

For research requiring the highest resolution of editing outcomes, single-cell DNA sequencing platforms like Tapestri enable genotyping at individual cell resolution [14]. This advanced approach reveals editing co-occurrence, zygosity, and cell clonality patterns that remain obscured in bulk sequencing data.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Genotyping Methods

| Method | Detection Capability | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 / Surveyor Assay | Mismatch detection | Low | Medium | Initial efficiency screening |

| Sanger + TIDE/ICE | Indel estimation | Medium | Low | Efficiency and rough indel profile |

| NGS Amplicon Sequencing | Full sequence characterization | High (<1%) | High | Precise efficiency, full indel spectrum, low-frequency edits |

| Single-Cell DNA Sequencing | Per-cell genotypes | High | Medium | Co-editing patterns, zygosity, clonality |

Comprehensive Off-Target Detection Strategies

Off-target effects remain a primary safety concern in CRISPR applications, as the Cas9 nuclease can cleave at genomic sites with sequence similarity to the intended target [15]. Multiple NGS-based approaches have been developed to identify and quantify these unintended editing events, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Computational Prediction Tools

In silico tools provide the most accessible starting point for off-target assessment by nominating potential off-target sites based on sequence homology to the guide RNA [15] [16]. These algorithms scan reference genomes for sites with partial complementarity to the gRNA spacer sequence, typically allowing for a specified number of mismatches or bulges.

Table 2: Major In Silico Off-Target Prediction Tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas-OFFinder | Alignment-based | Adjustable sgRNA length, PAM type, mismatch/bulge tolerance | Reference genome-dependent; misses structural variants |

| COSMID | Scoring-based | Stringent mismatch criteria; applies cutoff scores | Conservative; may miss valid off-targets |

| CCTop | Scoring-based | Considers mismatch distances to PAM | Moderate sensitivity and positive predictive value |

| DeepCRISPR | Machine learning | Incorporates sequence and epigenetic features | Requires computational resources |

While computationally efficient, these tools primarily identify sgRNA-dependent off-target sites and may miss edits influenced by cellular context or structural variations [15].

Cell-Free Empirical Methods

Cell-free approaches offer enhanced sensitivity for off-target nomination by detecting Cas9 cleavage events in vitro using purified genomic DNA. These methods typically involve:

- CIRCLE-Seq: Genomic DNA is circularized, incubated with Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP), then linearized fragments are sequenced [15] [12]

- SITE-Seq: Cas9-cleaved fragments are selectively biotinylated and enriched before sequencing [16] [12]

- Digenome-Seq: Purified genomic DNA is digested with Cas9 RNP then subjected to whole-genome sequencing [15] [12]

These approaches achieve high sensitivity but may overreport off-target sites due to the absence of cellular context like chromatin organization and DNA repair mechanisms [15].

Cell-Based Empirical Methods

Cell-based methods identify off-target sites within their native cellular context, providing more physiologically relevant nomination:

- GUIDE-seq: Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides are integrated into double-strand breaks, enabling genome-wide profiling of cleavage sites [16] [12]

- DISCOVER-seq: Utilizes DNA repair protein MRE11 as bait to perform ChIP-seq, identifying active off-target sites [15] [12]

- BLISS: Captures double-strand breaks in situ using dsODNs with T7 promoter sequence [15]

Recent comparative studies in primary human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) found that DISCOVER-seq and GUIDE-seq achieved the highest positive predictive value among off-target detection methods [16].

Off-Target Validation and Quantification

After nomination, potential off-target sites require validation through targeted amplicon sequencing. Systems like the rhAmpSeq CRISPR Analysis System enable multiplexed amplification and sequencing of nominated sites across many samples simultaneously [12]. This approach provides precise quantification of editing frequencies at each potential off-target locus.

(Off-Target Assessment Workflow)

Large-Scale Screening Applications

NGS enables unprecedented scale in CRISPR validation, particularly through high-throughput genotyping approaches that streamline the analysis of thousands of edited samples. Automated platforms like genoTYPER-NEXT allow researchers to process up to 10,000 samples per run by combining cell lysis, barcoded PCR, and multiplexed sequencing [13]. This scalability addresses a critical bottleneck in large-scale projects such as:

- Cell line engineering for bioproduction and disease modeling

- Functional genomics screens using CRISPR libraries

- Therapeutic cell product development requiring comprehensive characterization

The integration of single-cell multi-omics approaches further enhances large-scale screening capabilities. The Tapestri platform, for example, simultaneously assesses DNA editing outcomes and surface protein expression through antibody-oligo conjugates, enabling direct correlation of genotype to functional phenotype [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing for On-Target Genotyping

Workflow:

- Design and synthesize target-specific primers flanking the CRISPR target site (amplicon size: 200-300 bp)

- Extract genomic DNA from edited cells (crude lysates may be sufficient for some applications)

- Perform PCR amplification using barcoded primers to enable sample multiplexing

- Purify and pool amplicons at equimolar ratios

- Sequence on an Illumina platform (MiSeq or similar) with sufficient coverage (typically >10,000x)

- Bioinformatic analysis:

- Demultiplex samples by barcode

- Align reads to reference sequence

- Identify and quantify indels using tools like CRISPResso2

Off-Target Assessment Using GUIDE-seq

- Transfert cells with Cas9-gRNA RNP complex along with GUIDE-seq dsODN

- Allow 48-72 hours for dsODN integration into double-strand breaks

- Extract genomic DNA and perform library preparation

- Enrich for dsODN-integrated fragments via PCR

- Sequence using Illumina platforms

- Bioinformatic analysis to identify off-target integration sites

Single-CDNA Sequencing with Tapestri

Workflow [14]:

- Prepare single-cell suspension of edited cells

- Stain with antibody-oligo conjugates (AOCs) if protein co-detection is desired

- Encapsulate cells in droplets with lysis reagents

- Perform multiplex PCR using custom panel targeting on/off-target sites

- Sequence and analyze using automated Tapestri GE pipeline

Comparative Performance Analysis

Recent comparative studies provide valuable insights into the performance of different off-target detection methods. In primary human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells edited with high-fidelity Cas9, researchers found:

- Off-target activity is exceedingly rare, with an average of less than one off-target site per guide RNA [16]

- Virtually all true off-target sites were identified by available detection methods

- COSMID, DISCOVER-Seq, and GUIDE-seq attained the highest positive predictive value [16]

- Empirical methods did not identify off-target sites that were not also identified by refined bioinformatic methods [16]

Table 3: Method Performance in Primary HSPCs (Cromer et al., 2023)

| Method | Sensitivity | Positive Predictive Value | Key Advantages | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico (COSMID) | High | High | Computational efficiency; rapid results | Initial screening; resource-limited settings |

| GUIDE-seq | High | High | Cellular context; genome-wide profiling | Comprehensive assessment; translational research |

| DISCOVER-seq | High | High | In vivo application; native cellular state | Therapeutic development; safety assessment |

| CIRCLE-seq | Very High | Medium | Ultra-sensitive detection | Maximum sensitivity; regulatory submissions |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS-based CRISPR validation requires specific reagents and systems designed for these applications:

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Systems for NGS CRISPR Validation

| Reagent/System | Primary Function | Key Features | Representative Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| rhAmpSeq CRISPR Analysis System | Targeted amplicon sequencing | Multiplexed on/off-target site amplification; cloud-based analysis | IDT |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System | Genome editing | High-specificity Cas9 variants; modified gRNAs with improved specificity | IDT |

| genoTYPER-NEXT | High-throughput genotyping | Automated workflow; thousands of samples per run | GENEWIZ (Azenta) |

| Tapestri Platform | Single-cell DNA sequencing | Single-cell resolution; DNA + protein multi-omics | Mission Bio |

| GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | Initial efficiency screening | Rapid cleavage detection; gel-based analysis | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

NGS technologies provide an essential toolkit for comprehensive CRISPR validation, spanning from basic genotyping to sophisticated off-target detection and large-scale screening applications. The optimal approach depends on the specific research context:

- For basic research validation, targeted amplicon sequencing of on-target sites provides sufficient characterization

- For therapeutic development, a multi-tiered approach combining computational prediction with empirical validation (e.g., GUIDE-seq or DISCOVER-seq followed by targeted sequencing) offers the most rigorous safety assessment

- For complex editing strategies involving multiple targets, single-cell DNA sequencing reveals co-editing patterns and cellular heterogeneity unavailable through bulk methods

As CRISPR applications advance toward clinical implementation, NGS methodologies continue to evolve, with emerging approaches like long-read sequencing and improved computational prediction algorithms further enhancing our ability to characterize editing outcomes with precision and confidence.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has emerged as the gold standard for validating CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing experiments, offering unparalleled accuracy and sensitivity for characterizing editing outcomes such as insertion and deletion mutations (indels) [1] [2]. However, its adoption in research and drug development is tempered by significant challenges related to cost, bioinformatics, and workflow complexity. For researchers and scientists, a clear understanding of these limitations is crucial for selecting the appropriate validation method and effectively planning projects. This guide objectively compares NGS with alternative CRISPR analysis techniques, providing a detailed examination of their performance, supported by experimental data and a breakdown of essential research reagents.

Comparison of CRISPR Analysis Methods

The selection of a validation method involves balancing cost, time, and the required level of detail. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most common techniques.

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Data Output | Relative Cost | Hands-on & Analysis Time | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [1] [2] | Deep, targeted sequencing of PCR-amplified edited region | Comprehensive spectrum and precise frequency of all indels | High | High (DNA extraction, library prep, sequencing, bioinformatics) | High cost; requires bioinformatics expertise and infrastructure |

| Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) [1] | Computational decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Editing efficiency (ICE score), types and distributions of indels | Low | Medium (PCR, Sanger sequencing, web-based analysis) | Inference based on sequence trace decomposition |

| Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) [1] [2] | Computational decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Estimated editing efficiency and predominant indel types | Low | Medium (PCR, Sanger sequencing, web-based analysis) | Limited ability to detect complex or large indels without manual parameter adjustment |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay [1] [2] | Enzyme cleavage of heteroduplex DNA formed by mismatched amplicons | Gel-based estimation of total editing efficiency | Very Low | Low (PCR, digestion, gel electrophoresis) | Not quantitative; lacks sequence-level data; unreliable at high (>30%) or low (<10%) efficiency [2] |

| Genomic Cleavage Detection (GCD) [10] | Similar to T7E1; gel-based detection of cleaved PCR products | Gel-based estimation of total editing efficiency | Very Low | Low (PCR, digestion, gel electrophoresis) | Not quantitative; lacks sequence-level data |

Quantitative data from a comparative study highlights the accuracy gap between methods. When compared to NGS, the T7E1 assay consistently underestimated editing efficiency, particularly for highly active sgRNAs. For example, in edited mammalian cell pools, two sgRNAs (M2 and M6) showed similar activity (~28%) by T7E1, but NGS revealed dramatically different true efficiencies of 92% and 40%, respectively [2]. Another study demonstrated that the ICE analysis tool provided results highly comparable to NGS (R² = 0.96), offering a cost-effective alternative for achieving sequence-level detail [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for CRISPR Validation

Methodology:

- Step 1: DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification. Genomic DNA is extracted from edited cells (e.g., 3-4 days post-transfection). The target locus is amplified using high-fidelity PCR primers designed to flank the CRISPR cut site [2].

- Step 2: Library Preparation. The PCR amplicons are processed into an NGS library. This typically involves fragmentation, size selection, and the ligation of platform-specific adapters and sample barcodes (indices) to enable multiplexed sequencing [2].

- Step 3: Sequencing. The pooled library is sequenced on a platform such as the Illumina MiSeq, using a 2x250 bp paired-end run to ensure sufficient coverage and read length to span the edited region [2].

- Step 4: Bioinformatic Analysis. The resulting sequencing reads are demultiplexed and analyzed using a specialized pipeline. Key steps include:

- Alignment: Reads are aligned to the reference genome sequence using tools like BWA.

- Variant Calling: Specialized algorithms (e.g., CRISPResso2) are used to identify insertions and deletions around the expected cut site.

- Quantification: The frequency of each unique indel and the total editing efficiency are calculated [2].

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Mismatch Cleavage Assay

Methodology:

- Step 1: PCR Amplification. The target locus is PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of edited and control cells [2].

- Step 2: Heteroduplex Formation. The PCR products are denatured at 95°C and then slowly re-annealed by cooling. This allows strands from differently sized indels to hybridize, forming heteroduplexes with bulges at the mismatch sites [2].

- Step 3: T7E1 Digestion. The re-annealed DNA is incubated with the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme, which recognizes and cleaves the heteroduplex structures at the mismatch sites [2].

- Step 4: Visualization and Analysis. The digestion products are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The gel is visualized, and the intensity of the cleaved and uncleaved bands is analyzed by densitometry. The editing efficiency is estimated using formulas that compare the band intensities, though this is considered semi-quantitative at best [2].

Workflow and Logical Relationship Diagrams

CRISPR Validation Method Selection

NGS Workflow Complexity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of CRISPR validation experiments requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key materials and their functions.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [2] | Amplifies the target genomic locus for sequencing or assay with minimal errors. | Critical for reducing PCR-introduced artifacts that can confound NGS or Sanger results. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit [2] | Prepares the PCR amplicons for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters and indices. | Choice affects library complexity, preparation time, and compatibility with multiplexing. |

| T7 Endonuclease I [2] | Cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed by re-annealing of wild-type and indel-containing amplicons. | Sensitivity is affected by mismatch type and location; not all indels are cleaved efficiently. |

| Sanger Sequencing Service/Kit | Generates sequence traces for input into ICE or TIDE decomposition algorithms. | Purity and concentration of the PCR amplicon are crucial for high-quality sequence data. |

| ICE (Synthego) & TIDE Web Tools [1] | Computational platforms that analyze Sanger sequencing traces to infer indel types and frequencies. | ICE is reported to detect a broader range of outcomes (e.g., large indels) than TIDE [1]. |

| Validated Control gRNA [10] | A gRNA with known high efficiency (e.g., targeting human AAVS1 or HPRT locus) serves as a positive control. | Essential for confirming that the entire workflow from transfection to analysis is functioning correctly. |

NGS remains the most comprehensive and accurate method for validating CRISPR genome editing, providing the depth of information necessary for critical applications in therapeutic development [3] [2]. However, its significant limitations in cost, workflow complexity, and bioinformatics dependency are real barriers. For many research applications, Sanger sequencing-based computational methods like ICE offer a compelling compromise, delivering NGS-comparable accuracy for efficiency and basic indel characterization at a fraction of the cost and time [1]. Conversely, while inexpensive and fast, enzyme-based assays like T7E1 are unsuitable for any application requiring quantitative precision or sequence-level detail [2]. The optimal validation strategy depends on a clear-eyed assessment of the project's requirements, resources, and goals, often leading to a tiered approach where rapid initial screening is followed by confirmatory, deep analysis with NGS for critical samples.

Building Your NGS Validation Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

In the pipeline for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) validation of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the initial and critical wet-lab step is the PCR amplification of the target genomic locus and the subsequent preparation of sequencing-ready libraries [8] [17]. This step is fundamental for transforming the minute amounts of genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from edited cells into a format compatible with high-throughput sequencers. The accuracy and efficiency of this process directly determine the reliability of all downstream analyses, including the quantification of editing efficiency (on-target analysis) and the investigation of unintended, off-target effects [18] [2].

The primary goal is to selectively amplify the genomic region of interest from a background of billions of base pairs, creating a pool of DNA fragments (amplicons) that can be sequenced in parallel. For CRISPR validation, this involves special considerations, such as ensuring the amplicon flankes the Cas9 cut site and is designed to detect a wide variety of insertion/deletion mutations (indels) [8].

Core PCR and Library Preparation Strategies

Two primary methodological frameworks exist for preparing samples for targeted NGS: the single-step, amplicon-based approach and the more flexible two-step PCR strategy. The choice between them depends on the scale of the project, the available resources, and the required throughput.

Amplicon-Based Sequencing (One-Step Strategy)

This strategy is often the go-to method for lower-throughput projects or when using centralized sequencing core facilities that handle library preparation. In this approach, a single PCR reaction is performed using gene-specific primers that already contain full Illumina adapter sequences [2]. This means each sample receives a unique pair of primers, and the resulting PCR product is fully ready for sequencing after a simple clean-up step and normalization. While straightforward, this method can become costly and labor-intensive when scaling to hundreds of samples, as each requires a dedicated, custom primer pair.

Two-Step PCR Strategy

The two-step PCR strategy is widely adopted for high-throughput genotyping of CRISPR-edited cells, especially when screening hundreds of single-cell clones [8] [13]. This method decouples the target amplification from the indexing step, offering significant advantages in flexibility and cost-efficiency.

- Step 1 - Target Amplification: The first PCR uses gene-specific primers that have short, universal overhangs (partial Illumina adapter sequences). These primers amplify the target locus from the gDNA template. All samples for a given target locus can use the same pair of Step 1 primers, making reagent design and inventory simpler [8].

- Step 2 - Indexing and Adapter Addition: The products from Step 1 are used as templates in a second, much shorter PCR. This reaction uses universal primers that bind to the overhangs added in Step 1. These indexing primers contain the full Illumina adapter sequences, unique dual indices (UDIs), and sequencing primers [8]. The UIs allow multiple samples to be pooled together in a single sequencing run and computationally demultiplexed after sequencing.

The workflow and key components of the two-step PCR strategy are detailed in the diagram below.

Strategy Comparison and Selection

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the two main library preparation strategies to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method for their project.

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Library Preparation Strategies for CRISPR Validation

| Feature | Amplicon-Based (One-Step) | Two-Step PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Complexity | Lower; single PCR reaction [2] | Higher; requires two sequential PCR reactions [8] |

| Primer Design & Cost | Custom primers for each sample; higher cost at scale [2] | Universal indexing primers; lower cost per sample for high-throughput projects [8] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Ideal for low to medium throughput (e.g., dozens of samples) | Ideal for high-throughput screening (e.g., hundreds to thousands of samples) [8] [13] |

| Experimental Flexibility | Lower; primer sets are sample-specific | Higher; same indexing primers can be used for different projects and target loci [8] |

| Primary Application Context | Initial sgRNA validation, small-scale pool analysis [2] | Large-scale single-cell clone screening, multiplexed target analysis [8] [13] |

Practical Implementation and Experimental Protocols

Primer Design Guidelines

The design of the initial gene-specific primers is a critical determinant of success. Adhering to the following guidelines ensures optimal results [8]:

- Amplicon Length: The total amplicon length must be less than the combined length of the paired-end sequencing reads. For 2x250 bp sequencing, amplicons should be under 450 bp to ensure full coverage of both ends.

- Cut Site Placement: The Cas9 cut site should be positioned close to the center of the amplicon. Primers should bind at least 50 bp away from the cut site to allow for the detection of larger indels.

- Specificity: Tools like Primer-Blast should be used to check for and minimize potential off-target amplification [8].

- Adapter Sequences: For the two-step method, the gene-specific primers must have the appropriate partial Illumina adapter sequences added to their 5' ends [8]:

- Forward Primer Partial Adapter:

5′-CTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′ - Reverse Primer Partial Adapter:

5′-CAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT-3′

- Forward Primer Partial Adapter:

Step-by-Step Two-Step PCR Protocol

The following protocol, adapted from high-throughput genotyping workflows, outlines the detailed steps for preparing an NGS library from gDNA of CRISPR-edited cells [8].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Two-Step PCR Library Preparation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| gDNA Extraction Buffer | Lyses cells and digests protein, releasing gDNA for PCR [8] | Crude extract buffer: Tris, EDTA, Triton X-100, Proteinase K [8] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target locus with high accuracy and yield, minimizing PCR errors [8] | Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix [8] |

| Indexing Primers with UDIs | Adds full Illumina adapters and unique barcodes to amplicons in PCR Step 2 for sample multiplexing [8] | Commercially available sets or custom-designed primers [8] |

| NGS Analysis Pipeline | Bioinformatic tool for analyzing sequencing data to quantify editing outcomes [8] | CRIS.py, CRISPResso, others [8] [19] |

PCR Step 1: Target Amplification

- Reaction Setup: Set up PCR reactions using gDNA template (from crude lysates or purified) and gene-specific primers with partial adapter overhangs.

- Cycling Conditions: Use a high-fidelity polymerase and cycling conditions suitable for the polymerase and amplicon length. Typically, this involves an initial denaturation (98°C for 30 sec), followed by 25-35 cycles of denaturation (98°C for 10 sec), annealing (55-65°C for 15 sec), and extension (72°C for 15-30 sec/kb), with a final extension (72°C for 5 min).

- Product Clean-up: Purify the PCR products using magnetic beads or columns to remove primers, enzymes, and salts.

PCR Step 2: Indexing and Adapter Addition

- Reaction Setup: Use the purified Step 1 product as the template. Set up reactions with universal forward and reverse indexing primers. Each sample in the experiment must receive a unique combination of i7 and i5 indices to allow for multiplexing.

- Cycling Conditions: This is typically a shorter PCR (e.g., 8-12 cycles) using the same thermal profile as Step 1, but with a shorter extension time as the amplicon is already the correct size.

- Product Clean-up: Purify the final PCR products.

Library Pooling, Quantification, and Sequencing

- Pooling: Combine equal molar amounts of each uniquely indexed library into a single tube.

- Quantification: Precisely quantify the pooled library using methods like qPCR or the Bioanalyzer system to ensure optimal loading on the sequencer.

- Sequencing: Sequence the pool on an Illumina MiSeq, HiSeq, or similar platform, using a paired-end 250 bp or 300 bp run to ensure sufficient read length to cover the entire amplicon.

The entire workflow, from gDNA to a sequenced library, is visualized below.

Performance Data and Method Comparison

The choice of validation method, which is directly enabled by the PCR and library preparation strategy, has a profound impact on the accuracy of the results. A seminal study compared the popular T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay against targeted NGS for quantifying CRISPR editing efficiency and revealed significant discrepancies [2].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Efficiencies Measured by T7E1 vs. NGS

| sgRNA Example | Editing Efficiency (T7E1) | Editing Efficiency (NGS) | Discrepancy & Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | ~28% [2] | 92% [2] | Severe underestimation by T7E1; NGS reveals near-saturating editing. |

| M6 | ~28% [2] | 40% [2] | Same T7E1 value as M2, but true efficiency is 2.3-fold lower, a critical difference masked by T7E1. |

| H3 | Appears inactive [2] | <10% [2] | T7E1 lacks sensitivity for low-activity guides, potentially leading to false negatives. |

| M1 / M5 | Appears modestly active [2] | >90% [2] | T7E1 has a low dynamic range and cannot accurately report high editing efficiencies. |

This experimental data underscores that while enzymatic assays like T7E1 are cost-effective, they are not quantitative. The NGS-based approach, for which proper PCR amplification is the cornerstone, provides a true and quantitative measure of editing outcomes, which is essential for rigorous validation [2].

The initial step of PCR amplification and library preparation is a foundational element in the NGS validation workflow for CRISPR genome editing. The strategic choice between a one-step amplicon approach and a two-step PCR strategy dictates the scale, cost, and efficiency of a project. Adherence to rigorous primer design rules and protocols ensures the generation of high-quality sequencing data. As the experimental data demonstrates, moving away from traditional, less quantitative methods to an NGS-based approach is critical for obtaining an accurate and comprehensive view of CRISPR editing outcomes, enabling confident decision-making in both basic research and therapeutic development.

In the meticulous process of validating CRISPR genome editing efficiency, the choice of next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation method is a pivotal decision that directly impacts data quality and experimental conclusions. This step determines how the edited DNA fragments are processed, amplified, and prepared for sequencing, influencing the accuracy with which on-target edits and unwanted off-target effects are captured. The core decision facing researchers lies in selecting between PCR-based and PCR-free library preparation methods. PCR-based methods, which employ polymerase chain reaction to amplify the genetic material before sequencing, are renowned for their high sensitivity and low input requirements. In contrast, PCR-free methods, which omit this amplification step, are celebrated for providing superior sequencing uniformity and reduced bias. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of these two approaches, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the information needed to select the optimal protocol for their specific CRISPR validation workflow.

Core Principles and Comparative Workflows

The fundamental difference between the two methods lies in the inclusion or omission of a PCR amplification step after the initial DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation.

- PCR-based Workflow (Red): Incorporates a PCR amplification step after adapter ligation. This enables work with very low input DNA amounts (as little as 1 ng or less) and generates high yields from limited material [20]. However, the amplification process can introduce duplicates and sequence-specific biases.

- PCR-free Workflow (Blue): Omits the PCR amplification step. The adapter-ligated DNA is directly cleaned and prepared for sequencing. This avoids amplification-induced biases but requires significantly more input DNA (often 300-1000 ng) to generate sufficient library yield for sequencing [21] [20].

Performance Comparison: A Data-Driven Analysis

The choice between PCR-based and PCR-free methods has measurable consequences on data quality. The following table summarizes key performance characteristics, with supporting data from independent evaluations of commercial kits.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics at a Glance

| Feature | PCR-based | PCR-free |

|---|---|---|

| GC Bias | Higher, with under-coverage in GC-rich regions [21] [20] | More uniform coverage, including GC-rich promoters [21] [20] |

| Variant Calling (F1-Score) | Generally high (e.g., SNP: ~0.978, Indel: ~0.973) [21] | Excellent (e.g., SNP: ~0.984, Indel: ~0.982) [21] |

| Duplicate Reads | Higher, due to amplification of identical fragments [22] | Significantly reduced, preserving library complexity [22] |

| Input DNA Requirement | Low (1 ng - 500 ng) [20] | High (300 ng - 1 µg) [21] [20] |

| Assay Time | Faster (e.g., ~2-4 hours for some kits) [20] | Can be faster (e.g., ~1.5 hours for some kits) [20] |

Independent studies comparing multiple commercial kits provide quantitative evidence for these performance differences. Research evaluating eight commercially available PCR-free library prep solutions demonstrated that they consistently deliver high-quality, uniform WGS results with minimal GC bias [21]. The same study highlighted that PCR-free libraries achieve robust variant calling, with F1-scores for SNPs and indels often exceeding those of PCR-based methods [21]. Furthermore, a streamlined "Trinity" hybrid capture workflow that eliminates post-hybridization PCR reported a reduction in false positive indels by 89% and false negatives by 67%, underscoring the substantial improvement in accuracy achievable with PCR-free or reduced-PCR workflows [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard PCR-based Library Preparation

This protocol is widely used for its robustness and compatibility with low-input samples, a common scenario when cultivating edited clones is challenging.

- DNA Fragmentation and Size Selection: Fragment genomic DNA (100 pg - 1 µg) via enzymatic or mechanical shearing. Perform solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) bead cleanup to select for a target insert size (e.g., ~350 bp) [22] [20].

- End Repair and A-tailing: Use a master mix to repair fragment ends and add an 'A' base to the 3' ends, preparing them for adapter ligation. This is a standard step in kits like the KAPA HyperPrep [21].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate indexed adapters containing sequencing primer sites and sample barcodes to the fragments. This allows for multiplexing of samples in a single sequencing run [8].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the adapter-ligated library for 5-10 cycles using a high-fidelity PCR master mix to generate sufficient material for sequencing [22]. The number of cycles should be minimized to reduce bias.

- Final Library Cleanup and QC: Purify the amplified library with SPRI beads and quantify using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) and qPCR. Validate library size distribution using an instrument such as the TapeStation [22] [21].

Protocol 2: PCR-free Library Preparation

This protocol is the gold standard for variant calling applications, as it avoids the introduction of amplification artifacts, making it ideal for comprehensive CRISPR off-target assessment [21] [17].

- High-Input DNA Fragmentation: Fragment a larger quantity of high-quality genomic DNA (300 - 1000 ng). Mechanical shearing (e.g., with a Covaris sonicator) is often preferred for its reproducibility [22] [21].

- End Repair and A-tailing: Similar to the PCR-based protocol, this step prepares the blunt-ended, fragmented DNA for ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate specialized adapters in a reaction that may be scaled up to account for the higher DNA input. This step is performed without subsequent PCR amplification [21].

- Size Selection and Cleanup: Perform a double-sided SPRI bead cleanup to stringently select for the desired insert size range (e.g., 300-350 bp). This is critical for removing adapter dimers and optimizing library efficiency [22] [21].

- Final Library QC: Quantify the final library precisely using qPCR, as the absence of PCR amplification results in lower yields. Verify the library profile with a fragment analyzer [22] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in CRISPR NGS Validation | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurately amplifies target loci for PCR-based library prep or amplicon sequencing. Reduces PCR errors. | Platinum SuperFi II Master Mix [8], MyTaq Red Mix [8] |

| SPRI Beads | Purifies and size-selects DNA fragments after enzymatic reactions (e.g., ligation, PCR). Critical for optimizing library insert size. | Various suppliers (e.g., Beckman Coulter) |

| Indexed Adapters | Dual-indexed oligonucleotides ligated to DNA fragments, enabling multiplexing of samples. Unique barcodes differentiate samples post-sequencing. | IDT xGen Stubby Adapter-UDIs [22], Illumina TruSeq DNA UD Indexes |

| PCR-free Library Prep Kit | All-in-one reagent set for constructing unbiased NGS libraries without amplification. Ideal for WGS and off-target discovery. | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep [20], Watchmaker DNA Library Prep Kit with Fragmentation [21] |

| Hybrid Capture Panel | Biotinylated oligonucleotide baits that enrich specific genomic regions (e.g., a set of potential off-target sites) from a complex library before sequencing. | IDT xGen Exome Panel [22], Twist Core Exome Panel |

| NGS Analysis Software | Bioinformatics tool specifically designed to analyze CRISPR editing outcomes from NGS data, quantifying indel frequencies and types. | CRIS.py [8], Synthego ICE [1] |

Strategic Guidance for Your CRISPR Workflow

The optimal choice between PCR-based and PCR-free methods depends on the specific goals and constraints of your CRISPR validation experiment. The following decision pathway can help guide your selection:

For PCR-free protocols, prioritize: Comprehensive off-target analysis [17], whole-genome sequencing to discover unpredicted edits [17], and high-confidence characterization of complex edits like indels [22] [21]. This is crucial for preclinical therapeutic development where accuracy is paramount.

For PCR-based protocols, prioritize: High-throughput screening of on-target efficiency across many samples [1], situations with limited DNA input (e.g., single-cell CRISPR assays or precious edited clones) [20], and targeted sequencing where a specific amplicon is being tracked.

Newer streamlined workflows, such as the Trinity hybrid capture approach, demonstrate that innovations in library preparation can successfully eliminate post-hybridization PCR and washing steps, reducing turnaround time by over 50% while simultaneously improving data quality [22]. Staying informed of these technological advancements is key to optimizing your CRISPR validation pipeline.

Selecting the appropriate sequencing platform and determining the required depth are critical steps in designing robust NGS experiments for validating CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency. The choice impacts the resolution of editing outcomes, capability to detect rare events, and overall experimental cost. This guide objectively compares current sequencing methodologies, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for CRISPR Validation

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of mainstream and emerging sequencing platforms used for CRISPR validation.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for CRISPR Editing Analysis

| Platform / Method | Key Strength | Throughput & Scalability | Reported Editing Outcome Concordance | Primary Applications in CRISPR Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing + TIDE/ICE | Cost-effective for single-gene/sgRNA analysis [23] | Low throughput; suitable for small-scale validation [23] | High concordance with NGS for common indels [23] | Initial gRNA screening, routine knockout validation [23] |

| Short-Read NGS (Illumina) | High accuracy for small indel quantification [2] | High throughput; highly scalable for multiple targets [2] | Considered the benchmark for indel frequency measurement [2] | High-throughput sgRNA validation, precise indel frequency and spectrum analysis [2] |

| Long-Read Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore) | Resolves complex edits and phasing [23] [24] | Moderate to high throughput; flexible (flow cell choice) [23] | ICE: >99% (vs. Sanger/TIDE) [23] | Characterization of large deletions, structural variations, and haplotype phasing [23] [3] |

| Single-Cell DNA Sequencing (Tapestri) | Reveals clonality and zygosity in edited cell populations [3] | Targeted approach for hundreds of loci across thousands of cells [3] | Provides unique resolution not available with bulk methods [3] | Preclinical safety assessment, off-target profiling, and clonal heterogeneity in therapeutic cell products [3] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Targeted Enrichment (Context-Seq) | Enables sequencing of low-abundance targets and their genomic context [24] [25] | High multiplexing capability; cost-effective for targeted regions [24] | 7-15x enrichment over untargeted methods [24] | Investigating antimicrobial resistance gene transmission, complex genomic regions, and rare editing events [24] [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Oxford Nanopore Sequencing for Indel Analysis

This protocol, as described by McFarlane et al., streamlines routine gRNA validation [23].

- Step 1: DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification. High molecular weight genomic DNA is extracted from edited cells. The target region spanning the gRNA cut site is amplified via PCR, generating amplicons of >600 bp.

- Step 2: Library Preparation. PCR products are prepared using a Native Barcoding Kit, which allows for multiplexing samples. Barcoded libraries are pooled and loaded onto MinION flow cells for sequencing on a GridION device.

- Step 3: Data Analysis with nCRISPResso2. The basecalled sequencing data is analyzed using a nanopore-compatible version of CRISPResso2 (nCRISPResso2). This bioinformatic tool aligns reads to a reference sequence to quantify the percentage of reads with insertions, deletions, or other modifications at the target site, providing indel frequency and spectrum [23].

CRISPR-Cas9 Targeted Enrichment (Context-Seq)

This protocol enriches for specific genomic regions, such as antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), allowing for deep sequencing of their genomic context from complex samples [24].

- Step 1: Guide RNA Design. Multiple gRNAs are designed to flank the target ARG (e.g., blaCTX-M and blaTEM). Guides are selected using software like CHOPCHOP, with optimization for on-target efficiency and minimal off-target activity in complex communities.

- Step 2: Cas9 Cleavage and Adapter Ligation. Extracted, high molecular weight DNA is dephosphorylated. The Cas9 enzyme, complexed with the designed gRNAs, is used to create double-strand breaks at the target sites. Sequencing adapters are then selectively ligated to the Cas9-cut ends.

- Step 3: Proteinase K Digestion and Sequencing. A digestion step with thermolabile Proteinase K is performed to improve assay performance by removing Cas9 protein. The prepared library is sequenced on a long-read platform (MinION).

- Step 4: Analysis of Genomic Context. Sequencing reads, which are several kilobases long, are clustered and polished to generate consensus sequences. These sequences are annotated to identify the ARG, its flanking mobile genetic elements (e.g., transposases), and the broader genomic context to understand transmission dynamics [24].

Workflow Diagram: NGS Validation for CRISPR Editing

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for selecting the appropriate NGS validation strategy based on experimental goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Validation of CRISPR Editing

| Item | Function in Workflow | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at DNA target sites for validation or enrichment assays [24]. | Used in CRISPR-Cas9 targeted enrichment (Context-Seq) to cleave genomic DNA at specific loci [24]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus via complementary base pairing [24] [9]. | Designed using tools like CHOPCHOP; multiple gRNAs can be pooled for multiplexed target enrichment [24]. |

| Long-Range PCR Kit | Amplifies the target genomic region for sequencing, especially critical for long-read platforms [23]. | Generates amplicons >600 bp to encompass the gRNA cut site and sufficient flanking sequence for confident analysis [23]. |

| Native Barcoding Kit | Allows for multiplexing of samples by tagging each with a unique nucleotide sequence before pooling [23]. | Enables sequencing of multiple samples or targets on a single Oxford Nanopore flow cell, reducing cost per sample [23]. |

| Analysis Software (nCRISPResso2) | A bioinformatics tool specifically designed to analyze sequencing data and quantify CRISPR-induced indel frequencies [23]. | A nanopore-compatible version (nCRISPResso2) provides results highly concordant with ICE and TIDE analysis [23]. |

Within the framework of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) validation of CRISPR editing efficiency, bioinformatic analysis for indel quantification and variant calling is the critical step that transforms raw sequencing data into interpretable, actionable results. Following the confirmation of successful CRISPR component delivery and initial editing checks, this analytical phase precisely measures the spectrum and frequency of insertion and deletion mutations (indels) introduced by the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway [1]. In both basic research and therapeutic drug development, rigorous quantification of these on-target edits, coupled with comprehensive off-target profiling, is indispensable for assessing the efficacy and safety of a CRISPR intervention [26] [27]. This guide objectively compares the leading bioinformatics tools and pipelines available for this task, detailing their methodologies, performance characteristics, and suitability for different experimental scales.

Comparison of Bioinformatics Tools and Pipelines

The selection of a bioinformatics tool depends on the sequencing method, the scale of the experiment, and the required depth of information. The table below summarizes the primary tools and their optimal use cases.

Table 1: Comparison of Bioinformatics Tools for CRISPR Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Data Input | Key Functionality | Throughput & Scalability | Key Performance Metrics/Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted NGS (Gold Standard) [1] | NGS Reads (FASTQ) | Detects all variant types (indels, SNVs); identifies precise sequences and their relative abundances. | High-throughput; suitable for large sample numbers. | Editing efficiency, full indel spectrum, precise allele frequencies. |

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) [1] [28] | Sanger Sequencing (.ab1) | Determines indel percentage and profiles from Sanger data. | Scalable for hundreds of samples via batch upload. | ICE Score (indel %), KO Score (frameshift frequency), R² value for model fit. |

| TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) [1] [29] | Sanger Sequencing (.ab1) | Decomposes Sanger traces to estimate indel frequencies. | Best for small-scale experiments. | Indel frequency, goodness of fit (R²). Limited to +1 bp insertions. |

| TIDER (Tracking of Ins, Dels, and Recombination events) [29] | Sanger Sequencing (.ab1) | Quantifies HDR and specific nucleotide substitutions in addition to NHEJ indels. | Best for small-scale experiments. | HDR efficiency, specific mutation frequency, background indel frequency. |

| CRISPR-detector [30] | NGS Reads (FASTQ/BAM) | Co-analysis of treated & control samples to filter background; detects on/off-target edits and structural variations. | Optimized for WGS data analysis; highly scalable. | Annotated list of high-confidence editing-induced mutations, including SVs. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Platforms

Protocol: Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Analysis with CRISPR-detector

For the most comprehensive validation, including genome-wide off-target detection, WGS followed by analysis with a pipeline like CRISPR-detector is recommended [26] [30].

- Sample Preparation: Genomic DNA is extracted from both the CRISPR-edited population and a matched control (un-edited) sample. The quality and integrity of the DNA are confirmed.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Whole-genome sequencing libraries are prepared from both samples. These are then sequenced on an NGS platform to a sufficient depth (e.g., >30x coverage) to confidently call variants.

- Bioinformatic Analysis with CRISPR-detector:

- Alignment: Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) are aligned to the reference genome.

- Variant Calling: The core of CRISPR-detector uses the Sentieon TNscope pipeline for haplotype-based variant calling, which improves accuracy by handling sequencing errors effectively [30].

- Background Variant Removal: A co-analysis of the treated and control samples is performed. Variants present in both are identified as pre-existing background polymorphisms and filtered out [30].

- Annotation & Visualization: The final, high-confidence list of editing-induced mutations is annotated for functional impact (e.g., using a Variant Effect Predictor) and clinical relevance, and can be visualized within the tool [30].

Protocol: Targeted NGS for High-Throughput On-Target Analysis

When the focus is on deep sequencing of specific on-target loci, a targeted amplicon sequencing approach is more cost-effective [1].

- PCR Amplification: The genomic region surrounding each CRISPR target site is PCR-amplified from edited and control samples.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Amplicons are converted into an NGS library, often with the addition of sample barcodes to multiplex many samples in a single run. This is sequenced on a benchtop sequencer.

- Bioinformatic Analysis (Typical Workflow):

- Demultiplexing: Sequences are separated by sample based on their barcodes.

- Alignment & Variant Calling: Reads are aligned to the reference sequence for the amplicon. Tools like CRISPResso2 or custom scripts are used to quantify the percentage of reads containing indels precisely at the cut site.

- Quantification: Editing efficiency is calculated as the percentage of total reads that contain a non-wild-type sequence at the target locus. The output is the full spectrum of indel sequences and their individual frequencies [1].

Protocol: Rapid Analysis with Sanger Sequencing and ICE/TIDE

For a fast and cost-effective assessment of editing efficiency, Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons followed by computational decomposition is a widely used method [1] [28].

- PCR and Sanger Sequencing: The target locus is PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of edited and control cells. The purified PCR products are submitted for Sanger sequencing.

- Data Analysis with ICE:

- Upload: The Sanger sequencing chromatogram files (.ab1) for both control and edited samples are uploaded to the ICE web tool.

- Input Parameters: The user provides the gRNA target sequence and selects the nuclease used (e.g., SpCas9).

- Analysis: The ICE algorithm aligns the edited sequence trace to the control trace and uses linear regression to deconvolute the mixed signals, inferring the identities and proportions of different indels [28].

- Output: The tool provides an ICE Score (equivalent to indel percentage), a Knockout Score (proportion of frameshift or large indels), and a detailed list of all detected indels and their relative abundances [1] [28].

Diagram: Bioinformatic Analysis Workflow for CRISPR Validation. This flowchart outlines the key decision points and processes for analyzing CRISPR editing outcomes, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Critical Considerations for Analytical Validation

Addressing Off-Target Effects

A complete validation must account for unintended, off-target edits. WGS is the most thorough method for unbiased genome-wide off-target discovery [26]. As demonstrated in the validation of NF-κB reporter mice, WGS data can be aligned against predicted off-target sites from tools like Cas-OFFinder to confirm the absence of modifications in critical related genes [26]. For targeted approaches, guides should be designed using tools like CHOPCHOP or the Broad Institute's GPP sgRNA Designer to minimize off-target potential, and predicted off-target sites should be included in the sequencing panel [31].

The Importance of Controls and Background Mutation Filtering

The use of appropriate controls is non-negotiable for accurate variant calling. The best practice is to sequence a paired, unedited control sample (e.g., from the same cell line or organism) simultaneously with the edited sample. Tools like CRISPR-detector are specifically designed to perform a co-analysis, subtracting background variants present in the control from those in the treated sample. This step is crucial for eliminating false positives arising from pre-existing genetic variations or sequencing artifacts, ensuring that the reported variants are a direct consequence of the CRISPR editing process [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for CRISPR Analysis Workflows

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | Provides pure, intact DNA template for accurate PCR and sequencing, minimizing artifacts. |

| PCR Reagents & Target-Specific Primers | Amplifies the genomic region of interest for Sanger sequencing or NGS library preparation. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplified target sequences (amplicons) for sequencing on high-throughput platforms. |

| CRISPR Control (Un-edited) gRNA | Provides a genetically matched negative control sample essential for distinguishing true editing events from background noise [30]. |

| Reference Genomic Sequence | The standard sequence (e.g., GRCh38 for human) used as a baseline for aligning reads and calling variants. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software tools (e.g., CRISPR-detector, ICE) that process raw data into quantifiable editing metrics [1] [30]. |

| Validated Cell Line or Tissue Sample | A well-characterized biological source material that ensures reproducibility and reliability of the editing and analysis process. |

Bioinformatic analysis for indel quantification and variant calling is the cornerstone of rigorous CRISPR validation. The choice between gold-standard NGS and rapid, cost-effective Sanger-based methods hinges on the project's requirements for detail, throughput, and budget. While NGS provides an unparalleled, comprehensive view of editing outcomes both on- and off-target, tools like ICE offer a highly accurate and accessible alternative for high-throughput quantification of on-target efficiency that correlates strongly with NGS data [1] [28]. For clinical-grade validation, WGS with pipelines like CRISPR-detector that remove background variants represents the most rigorous standard [26] [30]. By systematically applying these tools and protocols, researchers and drug developers can confidently quantify CRISPR editing efficacy, fully characterize the resulting genetic landscape, and advance therapies with a robust understanding of both their intended and potential unintended effects.

Maximizing NGS Accuracy and Overcoming Common Challenges

In Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) validation of CRISPR editing experiments, low efficiency presents a major hurdle, potentially leading to inconclusive results and failed validation. Editing efficiency is fundamentally governed by two pillars: the design of the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas nuclease to its target, and the delivery system that transports CRISPR components into the cell. This guide provides an objective comparison of current strategies and technologies for optimizing both sgRNA design and delivery, presenting critical experimental data to inform the development of robust and reliable NGS validation protocols.

Optimizing sgRNA Design for Enhanced Efficiency

The sgRNA is not merely a targeting mechanism; its sequence and structural properties directly determine the success rate of editing, a key metric measured by NGS.

Key Design Parameters and Pitfalls

Effective sgRNA design requires balancing multiple sequence-based factors. The optimal target sequence length is 17-23 nucleotides; longer sequences increase off-target risk, while shorter ones compromise specificity [32]. The GC content should ideally be maintained between 40% and 60% [32]. Excessively high GC content can cause sgRNA rigidity and Cas9 misfolding, while low GC content results in unstable binding. Furthermore, consecutive nucleotide repeats (e.g., poly-T sequences) can disrupt transcription and should be avoided [32]. A critical prerequisite is the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) immediately downstream of the target site. For the commonly used SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [32].

Comparative Performance of sgRNA Design Libraries

The choice of sgRNA library directly impacts the efficiency of pooled CRISPR screens. Recent benchmark studies comparing genome-wide libraries reveal significant differences in their performance. The table below summarizes the key findings from a 2025 benchmark study that evaluated libraries in essentiality screens across multiple cell lines [7].

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA Libraries

| Library Name | Guides per Gene | Key Performance Finding | Relative Depletion of Essential Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna (top3-VBC) | 3 | Strongest depletion curve; performance equal to or better than larger libraries. | Strongest |

| Yusa v3 | 6 | One of the best-performing pre-existing libraries. | Strong |

| Croatan | 10 | One of the best-performing pre-existing libraries. | Strong |