Navigating Batch Effects in Longitudinal Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

Longitudinal microbiome studies are essential for understanding dynamic host-microbiome interactions but are particularly vulnerable to batch effects—technical variations that can obscure true biological signals and lead to spurious findings.

Navigating Batch Effects in Longitudinal Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

Longitudinal microbiome studies are essential for understanding dynamic host-microbiome interactions but are particularly vulnerable to batch effects—technical variations that can obscure true biological signals and lead to spurious findings. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to effectively handle these challenges. It covers the foundational concepts of batch effects in time-series data, explores advanced correction methodologies like conditional quantile regression and shared dictionary learning, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like unobserved confounders, and establishes a rigorous protocol for validating and comparing correction methods. By integrating insights from the latest research, this guide aims to empower robust, reproducible, and biologically meaningful integrative analysis of longitudinal microbiome data.

Understanding Batch Effects: The Hidden Challenge in Longitudinal Microbiome Research

What is a Batch Effect?

In molecular biology, a batch effect occurs when non-biological factors in an experiment introduce systematic changes in the data. These technical variations are unrelated to the biological questions being studied but can lead to inaccurate conclusions when their presence is correlated with experimental outcomes of interest [1].

Batch effects represent systematic technical differences that arise when samples are processed and measured in different batches. They are a form of technical variation that can be distinguished from random noise by their consistent, non-random pattern across groups of samples processed together [1].

The key distinction in technical variation lies in its organization:

- Systematic Technical Variation (Batch Effects): Consistent, reproducible patterns affecting entire groups of samples processed together

- Non-systematic Technical Variation: Random, unpredictable fluctuations affecting individual samples or measurements

How Do Batch Effects Differ from Normal Biological Variation in Microbiome Studies?

Batch effects introduce technical artifacts that can obscure or mimic true biological signals, making them particularly problematic in microbiome research where natural biological variations already present analytical challenges [2].

Table: Distinguishing Batch Effects from Biological Variation in Microbiome Data

| Characteristic | Batch Effects | Biological Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Technical processes (reagents, equipment, personnel) | Host physiology, environment, disease status |

| Pattern | Groups samples by processing batch | Groups samples by biological characteristics |

| Effect on Data | Introduces artificial separation or clustering | Represents genuine biological differences |

| Correction Goal | Remove while preserving biological signals | Preserve and analyze |

Microbiome data presents unique challenges for batch effect management due to its zero-inflated and over-dispersed nature, with complex distributions that violate the normality assumptions of many correction methods developed for other omics fields [3].

What Are the Most Common Causes of Batch Effects in Longitudinal Microbiome Studies?

Longitudinal microbiome studies investigating changes over time are particularly vulnerable to batch effects due to their extended timelines and repeated measurements [4].

Table: Common Sources of Batch Effects in Longitudinal Microbiome Research

| Experimental Stage | Batch Effect Sources | Impact on Longitudinal Data |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Different personnel, time of day, collection kits | Introduces time-dependent confounding |

| Sample Processing | Reagent lots, DNA extraction methods, laboratory conditions | Affects DNA yield and community representation |

| Sequencing | Different sequencing runs, platforms, or primers | Creates batch-specific technical biases |

| Data Analysis | Bioinformatics pipelines, software versions | Introduces computational artifacts |

The fundamental cause stems from the broken assumption that the relationship between instrument readout and actual analyte abundance remains constant across all experimental conditions. In reality, technical factors cause this relationship to fluctuate, creating inevitable batch effects [5].

Common Sources of Batch Effects in Microbiome Studies

How Can I Detect Batch Effects in My Microbiome Data?

Detecting batch effects requires both visual and statistical approaches. For longitudinal data, this becomes more complex as time-dependent patterns must be distinguished from technical artifacts [6] [4].

Visual Detection Methods:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Plot samples colored by batch to see if they separate along principal components

- t-SNE/UMAP Visualization: Check if samples cluster by batch rather than biological groups

- Guided PCA: Specifically assess whether known batch factors explain significant variance [4]

Statistical and Quantitative Metrics:

- PERMANOVA: Test whether batch explains significant variance in distance matrices

- Delta Value: Calculate the proportion of variance explained by batch factors [4]

- Quantitative Integration Metrics: kBET, ARI, or NMI to quantify batch separation [6]

In one longitudinal microbiome case study, researchers used guided PCA to test whether different primer sets (V3/V4 vs. V1/V3) created statistically significant batch effects, finding a moderate but non-significant delta value of 0.446 (p=0.142) [4].

What Batch Effect Correction Methods Are Available for Microbiome Data?

Several specialized methods have been developed to address the unique characteristics of microbiome data while preserving biological signals of interest.

Table: Batch Effect Correction Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Approach | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile Normalization [2] | Non-parametric, converts case abundances to percentiles of control distribution | Case-control studies with healthy reference population | Model-free, preserves rank-based signals |

| ConQuR [3] | Conditional quantile regression with two-part model for zero-inflated data | General microbiome studies with complex distributions | Handles zero-inflation and over-dispersion thoroughly |

| Harman [4] | PCA-based with constrained optimization | Longitudinal data with moderate batch effects | Effective in preserving time-dependent signals |

| ComBat [2] | Empirical Bayesian framework | Studies with balanced batch designs | May over-correct with strong biological signals |

| Ratio-Based Methods [7] | Scaling relative to reference materials | Multi-omics studies with reference standards | Requires concurrent profiling of reference materials |

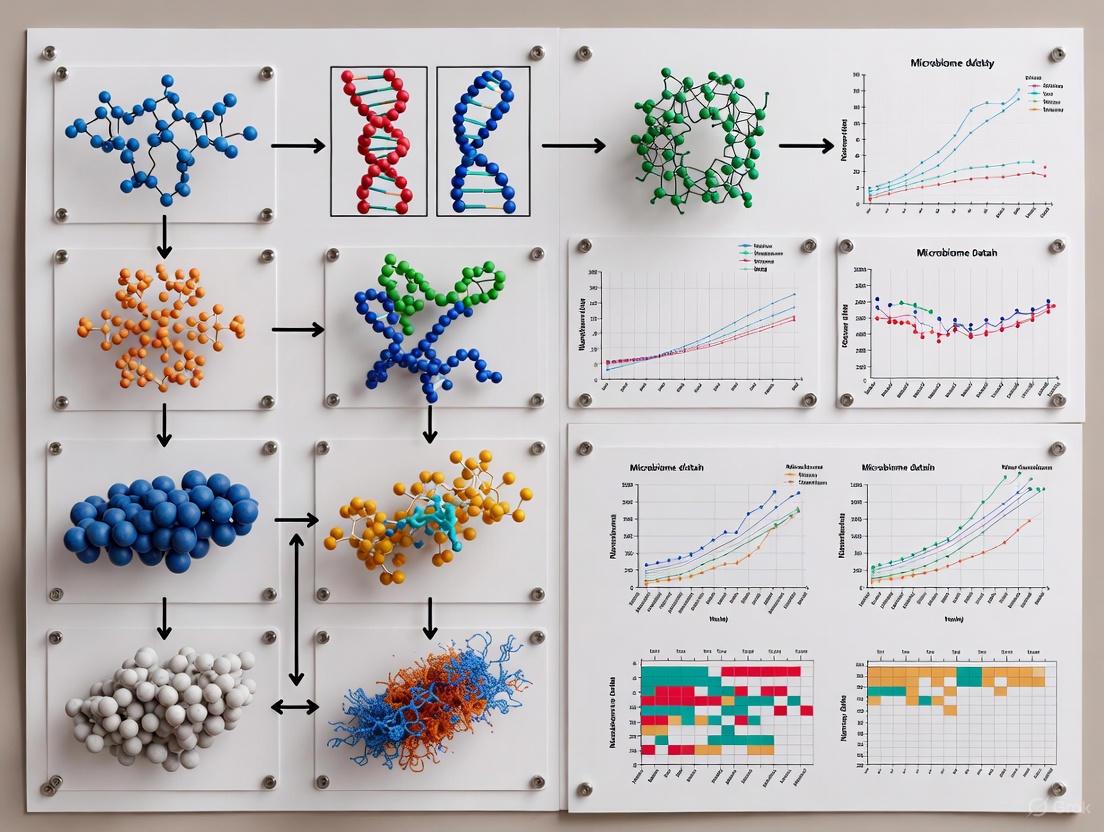

Batch Effect Correction Methodology Workflow

How Do I Choose the Right Correction Method for My Longitudinal Study?

Selecting the appropriate batch effect correction method depends on your study design, data characteristics, and research questions.

For Longitudinal Microbiome Studies Consider:

Study Design Compatibility:

Data Characteristics:

Signal Preservation:

- Methods must preserve temporal patterns and biological trends

- Avoid over-correction that removes genuine biological signals [4]

In a comparative evaluation of longitudinal differential abundance tests, Harman-corrected data showed better performance by demonstrating clearer discrimination between groups over time, especially for moderately or highly abundant taxa [4].

What Are the Key Signs of Overcorrection?

Overcorrection occurs when batch effect removal inadvertently removes genuine biological signals, potentially leading to false negative results.

Indicators of Overcorrection:

Loss of Expected Biological Signals:

- Absence of canonical markers for known biological groups

- Missing differential expression in pathways expected to be significant [6]

Unrealistic Data Patterns:

- Cluster-specific markers comprise ubiquitous genes (e.g., ribosomal genes)

- Substantial overlap among markers specific to different clusters [6]

Performance Metrics:

- Reduced classification accuracy in random forest models

- Increased error rates in sample prediction [4]

One study found that while uncorrected data showed mixed clustering patterns, overcorrected data failed to group biologically similar samples together, with increased error rates in downstream classification tasks [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Management

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Batch Effect Control

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Batch Effect Management | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials [7] | Provides standardization across batches via ratio-based correction | Enables scaling of feature values relative to reference standards |

| Standardized Primer Sets [4] | Reduces technical variation in amplification | Critical for 16S rRNA sequencing consistency |

| Multi-Omics Reference Suites [7] | Enables cross-platform standardization | Matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolite materials |

| Quality Control Samples [1] | Monitors batch-to-batch technical variation | Should be included in every processing batch |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kits | Minimizes protocol-induced variability | Consistent reagent lots reduce technical noise |

Can Proper Experimental Design Prevent Batch Effects?

While computational correction is valuable, proper experimental design remains the most effective strategy for minimizing batch effects.

Key Design Principles for Longitudinal Studies:

- Randomization: Process samples from different timepoints and groups across batches

- Balanced Design: Ensure each batch contains samples from all biological groups and timepoints

- Reference Materials: Include common reference samples in every batch [7]

- Metadata Collection: Document all potential batch effect sources for later adjustment

- Protocol Standardization: Use consistent reagents, personnel, and equipment throughout

When biological and batch factors are completely confounded (e.g., all samples from timepoint A processed in batch 1, all from timepoint B in batch 2), even advanced correction methods may struggle to distinguish technical from biological variation [7].

How Do I Validate That Batch Correction Has Been Effective?

Validation should assess both technical correction success and biological signal preservation.

Validation Framework:

Visual Assessment:

- PCA/t-SNE plots should show mixing of batches

- Biological groups should form distinct clusters regardless of batch [6]

Quantitative Metrics:

- Batch mixing scores (kBET, ARI, NMI) should improve

- Within-batch variance should decrease relative to between-batch variance [6]

Biological Validation:

- Known biological signals should be preserved or enhanced

- Classification accuracy should improve or remain stable [4]

In validation studies, successfully corrected data shows tighter grouping of intra-sample replicates within biological groups while maintaining clear separation between different treatment conditions over time [4].

In the study of microbial communities, longitudinal data collection—where samples are collected from the same subjects over multiple time points—is crucial for understanding dynamic processes. Unlike cross-sectional studies that provide a single snapshot, longitudinal studies can reveal trends, infer causality, and predict community behavior. However, this design introduces unique analytical challenges centered on time, dependency, and confounding. These characteristics are particularly pronounced when investigating batch effects, which are technical variations unrelated to the study's biological objectives. This guide addresses the specific troubleshooting issues researchers face when handling these complexities in longitudinal microbiome studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What makes the analysis of longitudinal microbiome data different from cross-sectional analysis? Longitudinal analysis is distinct because it must account for the inherent temporal ordering of samples and the statistical dependencies between repeated measurements from the same subject. Unlike cross-sectional data, where samples are assumed to be independent, longitudinal data from the same participant are correlated over time. This correlation structure must be properly modeled to avoid misleading conclusions [8]. Furthermore, batch effects in longitudinal studies can be especially problematic because technical variations can be confounded with the time-varying exposures or treatments you are trying to study, making it difficult to distinguish biological changes from technical artifacts [9].

2. How can I tell if my longitudinal dataset has a significant batch effect? A combination of exploratory and statistical methods can help diagnose batch effects. Guided Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is one exploratory tool that can visually and statistically assess whether samples cluster by batch (e.g., sequencing run or primer set) rather than by time or treatment group. The significance of this clustering can be formally tested with permutation procedures [4]. In a longitudinal context, it is crucial to check if the batch effect is confounded with the time factor, for instance, if all samples from later time points were processed in a different batch than the baseline samples.

3. I've corrected for batch effects, but I'm worried I might have also removed biological signal. How can I validate my correction? This concern about overcorrection is valid. After applying a batch-effect correction method (e.g., Harman, ComBat), you can evaluate its success by checking:

- Clustering Patterns: Do replicates or samples from the same subject and time point cluster more tightly? Do treatment groups separate better? [4]

- Classification Performance: Does a classifier (e.g., Random Forest) trained to distinguish treatment groups show a lower error rate on the corrected data compared to the uncorrected data? [4]

- Biological Plausibility: Do the results after correction align with known biology or pathways? For example, in a study of immune checkpoint blockade, successful correction should preserve microbial signatures and metabolic pathways (like short-chain fatty acid synthesis) known to be associated with treatment response [10].

4. My longitudinal samples were collected and sequenced in several different batches. Should I correct for this before or after my primary differential abundance analysis? Batch effect correction should be performed before downstream analyses like longitudinal differential abundance testing. If batch effects are not addressed first, they can inflate false positives or obscure true biological signals, leading to incorrect identification of temporally differential features [4]. The choice of correction method is critical, as some methods are more robust than others in longitudinal settings where batch may be confounded with time.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inability to Distinguish Biological Time Trends from Batch Effects

Symptoms:

- Abrupt, step-like changes in microbial abundance that align perfectly with processing batches, rather than showing smooth biological trajectories.

- Poor model fit when testing for changes over time, with high residual error.

Solutions:

- Prevention in Study Design: Whenever possible, randomize the processing order of samples from different time points and subjects across sequencing batches. This helps break the correlation between time and batch [9].

- Statistical Correction: Employ batch-effect correction methods that are designed for complex, confounded designs. For instance, MetaDICT is a newer method that uses shared dictionary learning and can better preserve biological variation when batches are confounded with covariates [11]. Another study found that Harman correction performed well in removing batch structure while maintaining a clear pattern of group differences over time in longitudinal data [4].

Problem 2: Low Power in Detecting Temporally Dynamic Microbes

Symptoms:

- Few microbial taxa or genes are identified as significantly changing over time, despite visual trends in the data.

- High variability in abundance measurements within subjects over time.

Solutions:

- Increase Sampling Frequency: If feasible, use denser longitudinal sampling. This provides a more detailed view of trajectories and can improve statistical power for detecting dynamic features [12].

- Use Appropriate Longitudinal Models: Move beyond simple per-time-point tests. Use statistical models that explicitly account for within-subject correlation and temporal structure. Mixed-effects models (e.g., with random subject effects) are a powerful framework for this. Methods like ZIBR (Zero-Inflated Beta Random-effects model) are specifically designed for longitudinal microbiome proportion data, handling both the dependency and zero-inflation [8].

Problem 3: Handling Missing Data and Irregular Time Intervals

Symptoms:

- Not all subjects have samples at every planned time point.

- Time intervals between samples are not uniform across subjects.

Solutions:

- Plan for Missingness: In your protocol, plan for potential drop-offs and collect rich metadata to help determine if the missing data is random.

- Use Robust Methods: Choose analytical methods that can handle irregular time points and missing data. Bayesian regression models with higher-order interactions are one such approach, as they can model individual trajectories and are robust to missing data points [10]. Some newer approaches also employ deep-learning-based interpolation during preprocessing to address missingness in time-series data [8].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Assessing Batch Effect in Integrated Longitudinal Data

Objective: To determine if a known batch factor (e.g., different trials, primer sets) introduces significant technical variation in a meta-longitudinal microbiome dataset.

Materials:

- Integrated microbiome abundance table (e.g., OTU, SGB) with metadata indicating batch and time.

- Statistical software (R/Python).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Combine your raw count tables from different batches. Do not normalize or transform at this stage.

- Guided PCA: Perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) where the principal components are "guided" by the known batch factor. This analysis estimates the proportion of total variance explained by the batch.

- Significance Testing: Use a permutation test (e.g., 1000 permutations) by randomly shuffling the batch labels. Calculate the p-value as the proportion of permutations where the variance explained by the shuffled batch is greater than or equal to the variance explained by the true batch.

- Interpretation: A statistically significant p-value (e.g., < 0.05) indicates a non-random batch effect that must be addressed before further analysis [4].

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Differential Abundance Testing with Batch Correction

Objective: To identify microbial features that show different abundance trajectories over time between two groups, while controlling for batch effects.

Materials:

- Batch-corrected microbiome abundance table.

- Sample metadata including time, group, and subject ID.

Methodology:

- Batch Correction: Apply a chosen batch correction method (see Reagent Table) to the raw data. Validate the correction using the methods described in the FAQ section.

- Model Fitting: For each microbial feature, fit a model that accounts for the longitudinal design. An example model structure is:

Abundance ~ Group + Time + Group*Time + (1|Subject_ID)- This model tests for a "Group-by-Time interaction," which indicates that the change over time is different between groups.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a multiple testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to the p-values from all tested features to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR).

- Validation: Check the results for biological consistency and, if possible, validate key findings in an independent cohort [4] [10].

Essential Data Summaries

Table 1: Common Challenges in Longitudinal Microbiome Data and Their Characteristics

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Dependency | Repeated measures from the same subject are statistically correlated [8]. | Violates the independence assumption of standard statistical tests, leading to inflated Type I errors. |

| Compositionality | Data represents relative proportions rather than absolute abundances [8]. | Makes it difficult to determine if an increase in one taxon is due to actual growth or a decrease in others. |

| Zero-Inflation | A high proportion of zero counts (70-90%) in the data [8]. | Reduces power to detect changes in low-abundance taxa; requires specialized models. |

| Confounded Batch Effects | Technical batch variation is correlated with the time variable or treatment group [4] [9]. | Makes it nearly impossible to distinguish true biological trends from technical artifacts. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Harman | A batch effect correction algorithm. | Found to be effective in removing batch effects in longitudinal microbiome data while preserving group-time interaction patterns [4]. |

| MetaPhlAn4 | A tool for taxonomic profiling at the species-level genome bin (SGB) level [10]. | Used for precise tracking of microbial strains over time in longitudinal studies, as in ICB-treated melanoma patients [10]. |

| Mixed-Effects Models (e.g., ZIBR, NBZIMM) | Statistical models that include both fixed effects (e.g., time, treatment) and random effects (e.g., subject) to handle dependency and other data characteristics [8]. | Modeling longitudinal trajectories while accounting for within-subject correlation, zero-inflation, and over-dispersion. |

| MetaDICT | A data integration method that uses shared dictionary learning to correct for batch effects [11]. | Robust batch correction, especially when there are unobserved confounding variables or high heterogeneity across studies. |

| Bayesian Regression Models | Statistical models that generate a posterior probability distribution for parameters, allowing for robust inference even with complex designs and missing data [10]. | Ideal for modeling longitudinal microbiome dynamics and testing differential abundance over time with confidence intervals. |

Key Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: The Impact of Batch Effects in a Longitudinal Workflow. This diagram outlines a typical longitudinal study pipeline and highlights how batch effects, if introduced during sampling or processing, can confound the entire analytical pathway, ultimately threatening the validity of the biological conclusions.

Diagram 2: Confounding Between Time and Batch. This diagram illustrates a classic confounding problem in longitudinal studies. Measurements from Time 1 and 2 are processed in Batch A, while Time 3 is processed in a different Batch B. Any observed change at T3 could be due to true biological progression, the batch effect, or both, making causal inference unreliable.

Why Do Batch Effects Cause False Discoveries?

Batch effects are technical variations introduced during different stages of sample processing, such as when samples are collected on different days, sequenced in different runs, or processed by different personnel or laboratories [9]. In longitudinal microbiome studies, where samples from the same individual are collected over time, these effects are particularly problematic because the technical variation can be confounded with the time variable, making it nearly impossible to distinguish true biological changes from artifacts introduced by batch processing [4] [9].

The core issue is that batch effects systematically alter the measured abundance of microbial taxa. When these technical variations are correlated with the biological groups or time points of interest, they can create patterns that look like real biological signals but are, in fact, spurious. This leads to two main types of errors in downstream analysis:

- False Positives (Spurious Associations): Identifying taxa as being differentially abundant over time or between groups when the observed differences are actually due to batch effects [9] [2].

- False Negatives (Obscured Signals): Missing true biological differences because the batch effect noise drowns out the genuine signal [9].

The table below summarizes the specific impacts on common analytical goals in longitudinal microbiome research.

Table 1: Impact of Batch Effects on Key Downstream Analyses

| Analytical Goal | Consequence of Uncorrected Batch Effects | Specific Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Abundance Testing | Inflated false discovery rates; spurious identification of non-differential taxa as significant [4] [13]. | In a meta-longitudinal study, different lists of temporally differential taxa were identified before and after batch correction, directly affecting biological conclusions [4]. |

| Clustering & Community Analysis | Samples cluster by batch (e.g., sequencing run) instead of by biological group or temporal trajectory, leading to incorrect inferences about community structure [4] [2]. | In PCoA plots, samples from the same treatment group failed to cluster together until after batch correction with a tool like Harman [4]. |

| Classification & Prediction | Predictive models learn batch-specific technical patterns instead of biology-generalizable signals, reducing their accuracy and robustness for new data [4] [3]. | In a Random Forest model, the error rate for classifying samples was higher with uncorrected data compared to data corrected with the ConQuR method [4]. |

| Functional Enrichment Analysis | Distorted functional profiles and pathway analyses, as the inferred functional potential is based on a taxonomically biased abundance table [4]. | After batch correction, the hierarchy and distribution of taxonomy in bar graphs became clearer, indicating a more reliable functional profile [4]. |

| Network Analysis | Inference of spurious microbial correlations that reflect technical co-occurrence across batches rather than true biological interactions [13]. | The complex, high-dimensional nature of longitudinal data makes it susceptible to technical covariation being mistaken for biotic interactions [13]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Correcting Batch Effects

How Can I Detect Batch Effects in My Dataset?

Before correction, you must diagnose the presence and severity of batch effects. The following workflow and table outline the primary methods.

Diagram 1: Batch effect detection workflow.

Table 2: Methods for Detecting Batch Effects

| Method | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Guided PCA (gPCA) | A specialized PCA that quantifies the variance explained by a known batch factor. It calculates a delta statistic and tests its significance via permutation [4]. | A statistically significant delta value (p-value < 0.05) indicates the batch factor has a significant systematic effect on the data structure [4]. |

| Ordination (PCA, PCoA, NMDS) | Unsupervised visualization of sample similarities based on distance matrices (e.g., Bray-Curtis). Color points by batch and by biological group [2]. | If samples cluster more strongly by batch than by biological group or time, a batch effect is likely present. |

| PERMANOVA | A statistical test that determines if the variance in distance matrices is significantly explained by batch membership [2]. | A significant p-value for the batch term confirms it is a major source of variation in the dataset. |

| Dendrogram Inspection | Visual assessment of hierarchical clustering results (e.g., from pvclust). |

If samples from the same batch are clustered together as sub-trees, rather than mixing according to biology, a batch effect is present [4]. |

What Are the Best Methods to Correct for Batch Effects?

Choosing a correction method depends on your data type, study design, and the nature of the batch effect. The field has moved beyond methods designed for Gaussian data (like standard ComBat) to techniques that handle the zero-inflated, over-dispersed, and compositional nature of microbiome counts [3].

Table 3: Comparison of Microbiome Batch Effect Correction Methods

| Method | Underlying Approach | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ConQuR (Conditional Quantile Regression) | A two-part non-parametric model. Uses logistic regression for taxon presence-absence and quantile regression for non-zero counts, adjusting for key variables and covariates [3] [14]. | Large-scale integrative studies; preserving signals for association testing and prediction; thorough removal of higher-order batch effects [3]. | Requires known batch variable. More robust and flexible than parametric models. Outputs corrected read counts for any downstream analysis [3] [14]. |

| Percentile Normalization | A model-free approach that converts case sample abundances into percentiles of the control distribution within each study before pooling [2]. | Case-control study designs where a clear control group is available for normalization [2]. | Simple and non-parametric. Effectively mitigates batch effects for meta-analysis but is restricted to case-control designs [2]. |

| Harman | A method based on PCA and a constrained form of factor analysis to remove batch noise [4]. | Longitudinal differential abundance testing; can perform well in removing batch effects visible in PCA plots [4]. | One study found it outperformed other correction tools (ARSyNseq, ComBatSeq) in achieving clearer separation of biological groups in heatmaps and dendrograms [4]. |

| ComBat and Limma (Linear Models) | Adjust data using linear models (Limma) or an empirical Bayes framework (ComBat) to remove batch-associated variation [2] [15]. | Scenarios where batch effects are assumed to be linear and not conflated with the biological effect of interest. | Originally designed for transcriptomics. May not adequately handle microbiome-specific distributions (zero-inflation, over-dispersion) and can struggle when batch is confounded with biology [3] [2]. |

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for applying a batch correction method like ConQuR.

Diagram 2: Batch effect correction process.

The Scientist's Toolkit

What Experimental and Reagent Factors Should I Control?

Batch effects originate long before data analysis. Careful experimental design is the first and most crucial line of defense.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Controls

| Item / Factor | Function / Role | Consequence of Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Set Lot | To amplify target genes (e.g., 16S rRNA) for sequencing. | Different lots or primer sets (e.g., V3/V4 vs. V1/V3) can preferentially amplify different taxa, causing major shifts in observed community structure [4]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | To lyse microbial cells and isolate genetic material. | Variations in lysis efficiency and purification across kits or lots can dramatically alter the recovery of certain taxa (e.g., Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative) [9]. |

| Sequencing Platform/Run | To determine the nucleotide sequence of the amplified DNA. | Differences between machines, flow cells, or sequencing runs introduce technical variation in read counts and quality [9] [15]. |

| Sample Collection & Storage | To preserve the microbial community intact at the time of collection. | Variations in storage buffers, temperature, and time-to-freezing can degrade samples and alter microbial profiles [9]. |

| Library Prep Reagents | Kits for preparing sequencing libraries (e.g., ligation, amplification). | Lot-to-lot variability in enzyme efficiency and chemical purity can introduce batch-specific biases in library preparation and subsequent counts [15]. |

How Can I Validate That My Batch Correction Worked?

After applying a correction method, it is essential to validate its performance to ensure technical variation was removed without stripping away biological signal.

- Visual Inspection: Re-run the ordination plots (PCA, PCoA) used for detection. After successful correction, samples should no longer cluster by batch and should instead group by biological factors or show mixed inter-batch clustering [4] [2].

- Statistical Validation: Use the original statistical tests (e.g., PERMANOVA) to confirm the batch factor no longer explains a significant portion of variance.

- Check Biological Signal: Ensure that known biological differences between groups (positive controls) are preserved or enhanced after correction. In longitudinal data, check that temporal trajectories become clearer [4] [3].

- Assess Downstream Analysis: Evaluate the impact on the final analysis. For example, after correction, differential abundance tests should yield more biologically plausible candidate lists, and prediction models should show improved accuracy and generalizability [4] [3] [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can't I Just Include "Batch" as a Covariate in My Statistical Model?

While including batch as a covariate in models like linear mixed models is a common practice (often called "batch adjustment"), it has limitations. This approach typically only adjusts for mean shifts in abundance between batches. Microbiome batch effects are often more complex, affecting the variance (scale) and higher-order moments of the distribution. A comprehensive "batch removal" method like ConQuR is designed to correct the entire distribution of the data, leading to more robust results for various downstream tasks like visualization and prediction [3].

What If My Batch Effects Are Confounded with My Main Longitudinal Variable?

This is a critical challenge in longitudinal studies, for example, if all samples from a later time point were processed in a single, separate batch. When batch is perfectly confounded with time, it becomes statistically nearly impossible to disentangle the technical effect from the biological time effect. There is no statistical magic bullet for this scenario. The solution primarily lies in preventive experimental design: randomizing samples from all time points across processing batches whenever possible. If the confounding has already occurred, the STORMS reporting guidelines recommend being exceptionally transparent about this limitation, as it severely impacts the interpretability of the results [9] [16].

I Have a Small Sample Size. Can I Still Correct for Batch Effects?

Yes, but with caution. The performance of many batch correction methods, including ConQuR, improves with increasing sample size [3] [14]. With a small sample size, the model may have insufficient data to accurately estimate and remove the batch effect without also removing a portion of the biological signal (over-correction). In such cases, using simpler methods like percentile normalization (if a control group is available) or relying on meta-analysis approaches that combine p-values instead of pooling raw data might be more conservative and reliable options [2].

Are There Reporting Standards for Batch Effects in Microbiome Studies?

Yes. The STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides a comprehensive framework for reporting human microbiome research [16]. It includes specific items related to batch effects, guiding researchers to:

- Report the source of batch effects (e.g., DNA extraction, sequencing run).

- Describe the statistical methods used for detecting and correcting them.

- Disclose any confounding between batch and biological variables. Adhering to these standards enhances the reproducibility and credibility of your findings [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my PCA plots show clear separation by study batch rather than the biological condition I am investigating?

This is a classic sign of strong batch effects. In microbiome data, technical variations from different sequencing runs, labs, or DNA extraction protocols can introduce systematic variation that overwhelms the biological signal. Your dimension reduction is correctly identifying the largest sources of variation in your data, which in this case are technical rather than biological. To confirm, check if samples cluster by processing date, sequencing run, or study cohort rather than by disease status or treatment group [9].

Q2: How can I distinguish between true biological separation and batch effects in my hierarchical clustering results?

Batch effects in hierarchical clustering typically manifest as samples grouping primarily by technical batches rather than biological groups. To diagnose this, color your dendrogram leaves by both batch ID and biological condition. If samples from the same batch cluster together regardless of their biological group, you likely have significant batch effects. Statistical methods like PERMANOVA can help quantify how much variation is explained by batch versus biological factors [9] [17].

Q3: My longitudinal samples from the same subject are not clustering together in PCA space. What could be causing this?

In longitudinal studies, batch effects from different processing times can overpower the temporal signal from individual subjects. This is particularly problematic when samples from the same subject collected at different time points are processed in different batches. The technical variation between batches exceeds the biological similarity within subjects. Methods like ConQuR and MetaDICT are specifically designed to handle these complex longitudinal batch effects while preserving biological signals [14] [11].

Q4: Can I use PCA to diagnose both systematic and non-systematic batch effects in microbiome data?

Yes, but with limitations. PCA is excellent for detecting systematic batch effects that consistently affect all samples in a batch similarly. However, non-systematic batch effects that vary depending on microbial abundance or composition may require more specialized diagnostics. Composite quantile regression approaches (like in ConQuR) can address both effect types by modeling the entire distribution of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) rather than just mean effects [17].

Q5: After batch effect correction, my biological signal seems weaker. Did the correction remove biological variation?

This is a common concern known as over-correction. It occurs when batch effect correction methods cannot distinguish between technical artifacts and genuine biological signals. To minimize this risk, use methods that explicitly preserve biological variation. MetaDICT, for instance, uses shared dictionary learning to distinguish universal biological patterns from batch-specific technical artifacts [11]. Always validate your results by checking if known biological associations remain significant after correction.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: PCA Shows Strong Batch Confounding

Symptoms: Samples cluster primarily by technical factors (sequencing batch, processing date) rather than biological groups in PCA plots.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Visual Diagnosis: Create PCA plots colored by both batch and biological condition. Look for clear separation by batch identifiers.

- Statistical Confirmation: Perform PERMANOVA to quantify variance explained by batch versus biological factors.

- Apply Batch Correction: Select an appropriate method based on your data structure:

- Validate Results: Re-run PCA after correction to confirm reduced batch separation while maintained biological grouping.

Prevention: When designing longitudinal studies, randomize sample processing order across time points and biological groups to avoid complete confounding of batch and biological effects [9].

Problem: Hierarchical Clustering Reveals Batch-Driven Dendrogram Structure

Symptoms: Samples from the same technical batch cluster together in the dendrogram, while biological replicates scatter across different clusters.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Distance Metric Selection: Choose appropriate beta-diversity metrics (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) that capture relevant ecological distances [18].

- Batch Effect Assessment: Calculate Average Silhouette Coefficients by batch to quantify batch-driven clustering [17].

- Compositional Data Transformation: Apply Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation to address compositionality before clustering [19].

- Structured Correction: Implement batch correction that accounts for the hierarchical nature of microbiome data using phylogenetic information or taxonomic relationships.

Advanced Approach: For complex multi-batch studies, use MetaDICT's two-stage approach that first estimates batch effects via covariate balancing, then refines the estimation through shared dictionary learning to preserve biological structure [11].

Problem: Inconsistent Dimensionality Reduction Results Across Different Methods

Symptoms: PCA, PCoA, and NMDS show conflicting patterns, making batch effect diagnosis challenging.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Method Alignment: Understand that different methods highlight different data aspects:

- PCA: Emphasizes Euclidean distance and variance

- PCoA: Can utilize ecological distance metrics (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac)

- NMDS: Focuses on rank-order relationships between samples [18]

- Consistent Metric Use: Apply the same distance metric across methods where possible for comparable results.

- Benchmark with Positive Controls: Include samples with known biological relationships to verify they maintain association after correction.

- Utilize Robust Frameworks: Implement Melody for meta-analysis, which generates harmonized summary statistics while respecting microbiome compositionality without requiring batch correction [20].

Batch Effect Correction Method Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of primary batch effect correction methods for microbiome data

| Method | Best Use Case | Key Advantages | Limitations | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConQuR [14] [17] | Single studies with known batch variables | Handles microbiome-specific distributions; Non-parametric; Works directly on count data | Requires known batch variable; Performance improves with larger sample sizes | Taxonomic read counts; Batch identifiers |

| MetaDICT [11] | Integrating highly heterogeneous multi-study data | Avoids overcorrection; Handles unobserved confounders; Generates embeddings for downstream analysis | Complex implementation; Computationally intensive | Multiple datasets; Common covariates across studies |

| Melody [20] | Meta-analysis of multiple studies | No batch correction needed; Works with summary statistics; Respects compositionality | Not for individual-level analysis; Requires compatible association signals | Summary statistics from multiple studies |

| MMUPHin [20] | Standardized multi-study integration | Comprehensive pipeline; Handles study heterogeneity | Assumes zero-inflated Gaussian distribution; Limited to certain transformations | Normalized relative abundance data |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Batch Effect Diagnosis Using Dimensionality Reduction

Purpose: Systematically identify and quantify batch effects in longitudinal microbiome data before proceeding with correction.

Materials Needed:

- Normalized microbiome abundance table (raw counts or relative abundance)

- Metadata with batch identifiers (processing date, sequencing run, study center)

- Biological condition metadata (disease status, treatment group, time points)

- R or Python statistical environment

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Pre-filter features to remove excess zeros and apply CLR transformation to address compositionality [19].

- PCA Analysis:

- Perform PCA on the transformed data

- Create scatter plots of PC1 vs. PC2, colored by both batch and biological condition

- Calculate variance explained by principal components

- Distance-Based Ordination:

- Compute Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and UniFrac distance matrices

- Perform PCoA on each distance matrix

- Visualize ordinations colored by batch and condition

- Statistical Quantification:

- Perform PERMANOVA to partition variance between batch and biological factors

- Calculate Average Silhouette Coefficients by batch to quantify batch-driven clustering [17]

- Hierarchical Clustering:

- Create dendrograms using appropriate linkage methods

- Color branches by batch membership and biological groups

- Calculate cophenetic correlation to assess clustering quality

Interpretation: Strong batch effects are indicated when batch explains significant variance in PERMANOVA, samples cluster by batch in ordination plots, and dendrogram structure follows batch rather than biological groupings.

Protocol 2: Batch Effect Correction Using Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR)

Purpose: Remove both systematic and non-systematic batch effects from microbiome count data while preserving biological signals.

Materials Needed:

- Raw taxonomic count table

- Batch identifier variable

- Biological covariates of interest

- Reference batch selection

Procedure:

- Reference Batch Selection: Use the Kruskal-Wallis test to identify the most representative batch as reference [17].

- Model Specification: For each taxon, ConQuR non-parametrically models the underlying distribution of observed values, adjusting for key biological covariates [14].

- Batch Effect Removal: The algorithm removes batch effects relative to the chosen reference batch by aligning conditional distributions across batches.

- Corrected Data Generation: Outputs corrected read counts that enable standard microbiome analyses (visualization, association testing, prediction).

- Validation:

- Re-run PCA on corrected data to confirm reduced batch separation

- Verify preservation of biological effects using positive controls

- Check that batch no longer explains significant variance in PERMANOVA

Technical Notes: ConQuR assumes that for each microorganism, samples share the same conditional distribution if they have identical intrinsic characteristics, regardless of which batch they were processed in [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for batch effect management

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ConQuR R package [14] | Batch effect correction | Single studies with known batches | Conditional quantile regression; Works on raw counts; Handles over-dispersion |

| MetaDICT [11] | Data integration | Multi-study meta-analysis | Shared dictionary learning; Covariate balancing; Avoids overcorrection |

| Melody framework [20] | Meta-analysis | Combining multiple studies without individual data | Compositionality-aware; Uses summary statistics; No batch correction needed |

| CLR Transformation [19] | Compositional data analysis | Data preprocessing for any microbiome analysis | Addresses compositionality; Scale-invariant; Handles relative abundance |

| PERMANOVA | Variance partitioning | Batch effect diagnosis | Quantifies variance explained by batch vs. biological factors |

| UniFrac/Bray-Curtis [18] | Ecological distance | Beta-diversity analysis | Phylogenetic/non-phylogenetic community dissimilarity |

Workflow Diagrams

Batch Effect Diagnosis and Correction Workflow

Method Selection Logic for Batch Effect Correction

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I detect if my primer sets are causing a batch effect in my longitudinal microbiome study?

Answer: Primer-induced batch effects can be detected through a combination of exploratory data analysis and statistical tests before proceeding with longitudinal analyses. In a meta-longitudinal study integrating samples from two different trials that used distinct primer sets (V3/V4 versus V1/V3), researchers employed guided Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to quantify the variance explained by the primer-set batch factor [4]. The analysis calculated a delta value of 0.446, defined as the ratio of the proportion of total variance from the first component on guided PCA divided by that of unguided PCA [4]. The statistical significance of this batch effect was assessed through permutation procedures (with 1000 random shuffles of batch labels), which yielded a p-value of 0.142, indicating the effect was not statistically significant in this specific case, though still practically important [4]. This suggests that while visual inspection of PCoA plots is valuable, it should be supplemented with quantitative metrics.

Detection Protocol:

- Perform Guided PCA: Use the

guidedPCApackage or similar tools to visualize sample clustering by primer batch [4]. - Calculate Batch Effect Metrics: Compute the delta value to quantify the proportion of variance explained by the primer batch factor [4].

- Assess Statistical Significance: Perform permutation testing (e.g., 1000 iterations) to obtain a p-value for the observed batch effect [4].

- Visual Inspection: Create PCoA or PCA plots colored by primer set to visually inspect clustering patterns [4].

- Evaluate Biological Impact: Proceed to evaluate the impact on downstream longitudinal analyses, as a statistically non-significant batch effect can still distort biological interpretations [4].

FAQ 2: What is the impact of uncorrected primer batch effects on longitudinal differential abundance analysis?

Answer: Uncorrected primer batch effects significantly compromise the validity of longitudinal differential abundance tests, leading to both false positives and false negatives. In the featured case study, the set of candidate features identified as temporally differential abundance (TDA) varied dramatically between uncorrected data and data processed with various batch-correction methods [4]. The core intersection set of "always TDA calls" was used for comparison, revealing that:

- Uncorrected data and some correction methods (ARSyNseq, ComBatSeq) showed persistent batch effects in heatmaps, with samples clustering by primer batch rather than treatment group or time point [4].

- Harman-corrected data demonstrated superior performance, showing clearer discrimination between treatment groups over time, especially for moderately or highly abundant taxa [4].

- Clustering reliability was significantly improved after proper batch correction. Hierarchical clustering of samples showed much tighter intra-group grouping with Harman-corrected data compared to the mixed-up patterns in uncorrected data [4].

Table 1: Impact of Batch Handling on Longitudinal Differential Abundance Analysis

| Batch Handling Procedure | Effect on TDA Detection | Performance in Clustering | Residual Batch Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected Data | High false positive/negative rates; batch-driven signals | Poor; samples cluster by batch | Severe |

| Harman Correction | Biologically plausible TDA calls; clearer group separation | Excellent; tight intra-group clusters | Effectively Removed |

| ARSyNseq/ComBatSeq | Inconsistent TDA calls | Moderate; some batch mixing persists | Moderate |

| Marginal Data (filtering) | Limited statistical power due to reduced sample size | Good for remaining data | Eliminated (but data lost) |

FAQ 3: Which batch effect correction methods are most effective for primer-related technical variation in longitudinal data?

Answer: Effectiveness varies, but methods specifically designed for the unique characteristics of microbiome data (zero-inflation, compositionality) generally outperform others. The case study compared several approaches [4], and recent methodological advances have introduced even more robust tools.

Recommended Correction Methods:

- Harman: Demonstrated excellent performance in the featured case study, effectively removing batch effects and enabling clearer biological interpretation in downstream analyses like heatmaps and hierarchical clustering [4].

- Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR): A comprehensive method that uses a two-part quantile regression model to handle zero-inflated, over-dispersed microbiome read counts. It non-parametrically models the entire conditional distribution of counts, making it robust for correcting higher-order batch effects beyond just mean and variance differences [3].

- Microbiome Batch Effects Correction Suite (MBECS): An R package that integrates multiple correction algorithms (e.g., ComBat, RUV, Batch Mean Centering) and provides standardized evaluation metrics to help users select the optimal method for their dataset [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Underlying Model | Handles Zero-Inflation? | Longitudinal Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harman [4] | PCA-based constraint | Yes | Suitable (Case-Study Proven) | Effectively discriminates groups over time in longitudinal tests [4] |

| ConQuR [3] | Conditional Quantile Regression | Explicitly models presence/absence and abundance | Highly suitable; generates corrected counts for any analysis | Robustly corrects higher-order effects; preserves key variable signals [3] |

| MBECS [21] | Suite of multiple methods | Varies by method (e.g., RUV, ComBat) | Suitable via integrated workflow | Provides comparative metrics to evaluate correction success [21] |

| ComBat/ComBatSeq | Empirical Bayes | Limited (Assumes Gaussian or counts) | Limited | Can leave residual batch effects in microbiome data [4] [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Managing Primer Batch Effects

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| V3/V4 Primer Set | Targets hypervariable regions V3 and V4 of the 16S rRNA gene. | One of the most common primer sets; differences in targeted region versus V1/V3 can cause significant batch effects [4]. |

| V1/V3 Primer Set | Targets hypervariable regions V1 and V3 of the 16S rRNA gene. | Yields systematically different community profiles compared to V3/V4; avoid mixing with V3/V4 in same longitudinal analysis without correction [4]. |

| Harman R Package | A batch correction tool using a constrained matrix factorization approach. | Effectively removed primer batch effects in the case study, enabling valid longitudinal analysis [4]. |

| ConQuR R Script | Conditional Quantile Regression for batch effect removal on microbiome counts. | Superior for zero-inflated count data; corrects entire conditional distribution, not just mean [3]. |

| MBECS R Package | An integrated suite for batch effect correction and evaluation. | Allows testing of multiple BECAs and provides metrics (e.g., Silhouette coefficient, PCA) to choose the best result [21]. |

| phyloseq R Package | A data structure and toolkit for organizing and analyzing microbiome data. | The foundational object class used by MBECS and other tools for managing microbiome data with associated metadata [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessment and Correction of Primer Set Batch Effects in a Longitudinal Framework

Objective: To identify, quantify, and correct for batch effects introduced by different 16S rRNA primer sets in a longitudinal microbiome dataset, thereby ensuring the validity of subsequent time-series and differential abundance analyses.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Integration and Pre-processing:

- Combine raw OTU or ASV count tables from all longitudinal time points and studies that used different primer sets.

- Create a comprehensive metadata file that includes: Sample ID, Subject ID, Time Point, Primer Set (batch), Treatment Group, and other relevant covariates [4].

- Perform basic filtering to remove low-abundance features using a standard toolkit like

MicrobiomeAnalyst[4].

Initial Batch Effect Detection (Pre-Correction Assessment):

- Visual Inspection: Generate a PCoA plot (e.g., using Bray-Curtis or UniFrac distance) colored by the primer set factor. Look for clear clustering of samples by primer type [4].

- Quantitative Metric: Perform guided PCA to calculate the delta value, which quantifies the variance explained by the primer batch factor [4].

- Statistical Test: Conduct a permutation test (e.g., with

PERMANOVA) to determine the statistical significance of the observed grouping by primer set [4].

Batch Effect Correction:

- Apply one or more of the following correction methods to the integrated count data:

- Harman: Use the

Harmanpackage with the primer set as the batch factor and key biological variables (e.g., treatment group, time) as confounders [4]. - ConQuR: Use the

ConQuRfunction, specifying the primer set as the batch variable and including biological variables as covariates. Choose between ConQuR and ConQuR-libsize based on whether library size differences are of biological interest [3]. - MBECS Workflow: Use the

MBECSpackage to run a suite of correction methods (e.g., ComBat, RUV) and store the results in a unified object for easy comparison [21].

- Harman: Use the

- Apply one or more of the following correction methods to the integrated count data:

Post-Correction Evaluation:

- Re-visualization: Re-generate the PCoA plot from Step 2 using the corrected data. Successful correction is indicated by the inter-mixing of samples from different primer batches [4] [21].

- Numerical Metrics: Use evaluation metrics within

MBECS, such as Principal Variance Components Analysis (PVCA), to quantify the reduction in variance attributed to the batch factor. The Silhouette coefficient with respect to the batch factor should decrease post-correction [21]. - Downstream Analysis Check: Perform a preliminary longitudinal differential abundance test (e.g., using

metaSplinesormetamicrobiomeR) on both corrected and uncorrected data. Compare the lists of significant taxa to ensure biological signals are preserved while batch artifacts are removed [4].

Advanced Considerations for Longitudinal Designs

Longitudinal microbiome data introduces unique challenges beyond standard batch correction. The data are inherently correlated (repeated measures from the same subject), often zero-inflated, and compositional [22]. When correcting for primer batch effects in this context, it is critical to choose methods that:

- Preserve Temporal Signals: The correction must remove technical variation without flattening meaningful biological trajectories over time [4].

- Account for Complex Distributions: Methods like ConQuR are advantageous because they model zero-inflation and over-dispersion directly, which is not handled well by methods designed for Gaussian data like standard ComBat [3] [22].

- Enable Valid Downstream Analysis: The ultimate goal is to produce batch-corrected data that can be fed into specialized longitudinal models (e.g.,

ZIBR,NBZIMM) for testing time-varying group differences, without the results being confounded by primer-set technical artifacts [4] [22].

A Practical Toolkit for Batch Effect Correction in Time-Series Microbiome Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose between ComBat, limma, and a Negative Binomial model for correcting batch effects in my microbiome data?

The choice depends on your data type and the nature of your analysis.

- ComBat and its derivatives are highly effective when you have a known batch variable and need to remove its systematic non-biological variations.

ComBat-seqand the newerComBat-refare specifically designed for count-based data (e.g., RNA-Seq, microbiome sequencing) as they use a negative binomial model and preserve integer counts for downstream differential analysis [23] [24]. - limma is ideal for continuous, normally distributed data. While powerful for microarray-based transcriptomics, its application in microbiome research is often for analyzing transformed (e.g., log-transformed) or compositionally normalized data [24].

- Negative Binomial Models are the foundation for tools like

edgeRandDESeq2, which are standard for direct analysis of count data. They inherently model overdispersion, a common characteristic of sequencing data. You can often include "batch" as a covariate in the design matrix of these models to statistically account for its effect [23] [24].

Q2: My dataset has a high proportion of zeros. Which of these methods is most robust?

Methods based on Negative Binomial models are generally more robust for zero-inflated count data, as they are specifically designed to handle overdispersion, which often accompanies zero inflation [24]. While ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref also use a negative binomial framework and are therefore suitable, standard limma applied to transformed data may be less ideal for highly zero-inflated raw counts without careful preprocessing.

Q3: What are the key considerations for applying these methods in longitudinal microbiome studies?

Longitudinal data analysis requires methods that account for the correlation between repeated measures from the same subject.

- While

ComBatandlimmacan adjust for batch effects at each time point, they do not inherently model within-subject correlations. - For a more integrated approach, you can use Negative Binomial Mixed Models (NBMM), which allow you to include both fixed effects (like condition, time, and batch) and random effects (like subject ID) to account for repeated measures [25]. The

timeSeqpackage is an example of this approach for RNA-Seq time course data.

Q4: How can I validate that my batch effect correction was successful?

The most common validation is visual inspection using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). Before correction, samples often cluster strongly by batch. After successful correction, this batch-specific clustering should diminish, and biological groups of interest should become more distinct.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Loss of Statistical Power After Batch Correction

Problem: After applying a batch correction method, you find fewer significant features (e.g., differentially abundant taxa) than expected.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Over-correction: The method might be removing genuine biological signal along with the batch effect.

- Solution: Consider using a reference batch approach. The

ComBat-refmethod, for instance, selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference and adjusts other batches towards it, which has been shown to help maintain high statistical power [23]. - Solution: When using a negative binomial model in

edgeRorDESeq2, ensure your model formula correctly specifies the biological condition of interest alongside the batch term.

- Solution: Consider using a reference batch approach. The

- Incorrect Model Specification: The model may not be appropriate for the data's distribution.

- Solution: Verify that you are using a count-based model (like negative binomial) for raw sequencing counts. Avoid applying methods designed for normal distributions (like standard

limma) to raw count data without proper variance-stabilizing transformation [24].

- Solution: Verify that you are using a count-based model (like negative binomial) for raw sequencing counts. Avoid applying methods designed for normal distributions (like standard

Issue: Model Fails to Converge or Produces Errors

Problem: When running a negative binomial model or ComBat, the software returns convergence errors or fails to run.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Sparse Data or Too Many Zeros: Extremely sparse data can cause estimation problems.

- Solution: Filter out low-abundance taxa before analysis. A common practice is to remove taxa that do not have a minimum count in a certain percentage of samples [26].

- Complex Model for Small Sample Size: A model with too many covariates (batches, conditions) relative to the number of samples can be unstable.

- Solution: Simplify the model if possible. For

ComBat, ensure that the batch variable is not perfectly confounded with the biological group variable.

- Solution: Simplify the model if possible. For

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Applying ComBat-ref for Batch Effect Correction in Microbiome Count Data

Objective: To remove batch effects from microbiome sequencing count data while preserving biological signal and maximizing power for downstream differential analysis.

Materials:

- A count matrix (features x samples) from a 16S rRNA or metagenomic sequencing study.

- Metadata including a known batch variable and the biological condition of interest.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Filter the count matrix to remove low-abundance taxa (e.g., those with a maximum abundance below 0.001% across all samples) to reduce noise [26].

- Dispersion Estimation: For each batch, estimate a batch-specific dispersion parameter using a negative binomial model [23].

- Reference Batch Selection: Calculate the pooled dispersion for each batch and select the batch with the smallest dispersion as the reference batch.

- Model Fitting: Fit a generalized linear model (GLM) for each gene/taxon. The model is typically of the form:

log(μ_ijg) = α_g + γ_ig + β_cjg + log(N_j)whereμ_ijgis the expected count for taxongin samplejfrom batchi,α_gis the background expression,γ_igis the batch effect,β_cjgis the biological condition effect, andN_jis the library size [23]. - Data Adjustment: Adjust the count data from all non-reference batches towards the reference batch. The adjusted expression is calculated as:

log(μ~_ijg) = log(μ_ijg) + γ_1g - γ_igfor batchesi ≠ 1(where batch 1 is the reference) [23]. - Count Matching: Generate a final adjusted integer count matrix by matching the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the original and adjusted negative binomial distributions.

Validation:

- Perform PCoA on the corrected count data using a robust distance metric (e.g., Bray-Curtis). Visualize to confirm that samples no longer cluster primarily by batch.

Protocol: Differential Abundance Analysis with Batch as a Covariate in a Negative Binomial Model

Objective: To identify differentially abundant taxa across biological conditions while statistically controlling for the influence of batch effects.

Materials:

- A filtered microbiome count matrix.

- Metadata with biological condition and batch variables.

Methodology (using edgeR or DESeq2):

- Data Input: Load the count matrix and metadata into your chosen tool (

edgeRorDESeq2). - Normalization: Apply a normalization method to account for differences in library sizes (e.g., TMM in

edgeRor median-of-ratios inDESeq2) [24]. - Model Design: Specify the model design matrix. The design should include both the batch and the biological condition of interest.

- Example in R for

edgeR:design <- model.matrix(~ batch + condition)

- Example in R for

- Model Fitting: Estimate dispersions and fit the negative binomial GLM.

- Hypothesis Testing: Perform a likelihood ratio test or a Wald test to test for significant differences attributable to the biological condition, while considering the batch effect.

Method Comparison and Selection Table

Table 1: Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Core Model | Data Type | Handles Count Data? | Longitudinal Capability? | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes, Linear | Continuous, Microarray | No (requires transformation) | No (without extension) | Effective for known batch effects; widely used [26] [24] |

| ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes, Negative Binomial | Count (RNA-Seq, Microbiome) | Yes, preserves integers | No (without extension) | Superior power for overdispersed count data vs. ComBat [23] |

| ComBat-ref | Empirical Bayes, Negative Binomial | Count (RNA-Seq, Microbiome) | Yes, preserves integers | No (without extension) | Maintains high statistical power by using a low-dispersion reference batch [23] |

| limma | Linear Models | Continuous, Microarray | No (requires transformation) | No (without extension) | Powerful for analyzing transformed data; very flexible for complex designs [24] |

| NBMM (e.g., timeSeq) | Negative Binomial Mixed Model | Count (RNA-Seq, Microbiome) | Yes | Yes | Can account for within-subject correlation in longitudinal studies [25] |

| edgeR/DESeq2 | Negative Binomial GLM | Count (RNA-Seq, Microbiome) | Yes | Limited (can use paired design) | Standard for differential abundance; batch included as covariate [23] [24] |

Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a decision pathway for selecting an appropriate batch effect correction method based on your data characteristics and research goals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools and Packages for Batch Effect Correction

| Tool/Package | Function | Primary Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| sva (ComBat) [26] [24] | Batch effect correction | Microarray, transformed sequencing data | Empirical Bayes framework for known batch effects. |

| sva (ComBat-seq) [23] | Batch effect correction | Count-based sequencing data (RNA-Seq, Microbiome) | Negative binomial model; preserves integer counts. |

| limma [24] | Differential analysis & batch correction | Continuous, normalized data | Flexible linear modeling; can include batch in design. |

| edgeR [23] [24] | Differential abundance analysis | Count-based sequencing data | Negative binomial GLM; includes batch as covariate. |

| DESeq2 [23] [24] | Differential abundance analysis | Count-based sequencing data | Negative binomial GLM; includes batch as covariate. |

| metagenomeSeq [24] | Differential abundance analysis | Microbiome count data | Uses CSS normalization; models zero-inflated data. |

Abstract: This technical support guide provides researchers with practical solutions for implementing Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR), a robust batch effect correction method specifically designed for zero-inflated and over-dispersed microbiome data in longitudinal studies.

Understanding ConQuR and Its Application Scope

What is ConQuR and how does it fundamentally differ from other batch effect correction methods?

Answer: Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR) is a comprehensive batch effects removal tool specifically designed for microbiome data's unique characteristics. Unlike methods developed for other genomic technologies (e.g., ComBat), ConQuR uses a two-part quantile regression model that directly handles the zero-inflated and over-dispersed nature of microbial read counts without relying on parametric distributional assumptions [3] [14].

Key differentiators include:

- Non-parametric approach: Models the entire conditional distribution of microbial read counts rather than just mean and variance

- Two-part structure: Separately models presence-absence status (via logistic regression) and abundance distribution (via quantile regression)

- Distributional alignment: Adjusts the entire conditional distribution relative to a reference batch, correcting for mean, variance, and higher-order batch effects

- Preservation of biological signals: Specifically designed to preserve effects of key variables while removing technical artifacts [3]

When should researchers choose ConQuR over other batch correction methods for longitudinal microbiome studies?

Answer: ConQuR is particularly advantageous in these scenarios:

- Data characteristics: Your microbiome data exhibits significant zero-inflation (>20% zeros) and over-dispersion (variance much greater than mean)

- Study designs: Longitudinal studies with repeated measurements where batch effects are confounded with time points

- Analysis goals: When you need batch-removed read counts for multiple downstream analyses (visualization, association testing, prediction)

- Effect heterogeneity: When batch effects vary across the abundance distribution (not just mean shifts)

- Data integration: When pooling data from multiple studies with different processing protocols [3] [4]

Conversely, ConQuR may be less suitable when sample sizes are very small (<50 total samples) or when batch effects are minimal compared to biological effects.

Implementation and Workflow Guidance

What is the complete experimental protocol for implementing ConQuR?

Answer: The ConQuR implementation follows a structured two-step procedure:

Step 1: Regression-step

- For each taxon, fit a two-part model:

- Logistic component: Model presence-absence status using binomial regression

- Quantile component: Model multiple percentiles (e.g., deciles) of read counts conditional on presence using quantile regression

- Include batch ID, key variables (e.g., disease status), and relevant covariates in both model components

- Estimate both original and batch-free distributions by subtracting fitted batch effects relative to a reference batch [3]

Step 2: Matching-step

- For each sample and taxon:

- Locate the observed count in the estimated original distribution

- Identify the corresponding percentile

- Assign the value at that same percentile in the estimated batch-free distribution as the corrected measurement

- Iterate across all samples and taxa [3]

What are the essential computational tools and their functions for implementing ConQuR?

Answer: The table below outlines the key research reagent solutions for ConQuR implementation:

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for ConQuR Implementation

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| R quantreg package | Quantile regression modeling | Fitting conditional quantile models for abundance data | Handles multiple quantiles simultaneously; robust estimation methods [27] |

| MMUPHin | Microbiome-specific batch correction | Alternative for relative abundance data | Handles zero-inflation; integrates with phylogenetic information [3] [28] |

| MBECS | Batch effect correction suite | Comparative evaluation of multiple methods | Unified workflow; multiple assessment metrics [21] |

| Phyloseq | Microbiome data management | Data organization and preprocessing | Standardized data structures; integration with analysis tools [21] |

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

How should researchers handle situations where batch effects remain after ConQuR application?

Answer: If batch effects persist after ConQuR correction, consider these diagnostic and optimization steps:

Diagnostic Checks:

- Visual assessment: Create PCA/PCoA plots colored by batch before and after correction

- Quantitative metrics: Calculate batch effect strength using metrics like Partial R² from PERMANOVA [28]

- Distribution examination: Check whether zero-inflation patterns align across batches post-correction

Optimization Strategies:

- Reference batch selection: Try different reference batches if the initial choice doesn't yield optimal results

- Covariate adjustment: Review and potentially expand the set of biological covariates included in the model

- Parameter tuning: Adjust the number of quantiles used in the regression (typically 9-19 quantiles work well)

- Library size consideration: Use ConQuR-libsize version if between-batch library size differences are biologically relevant [3]

What are the specific solutions when applying ConQuR to longitudinal study designs?

Answer: Longitudinal microbiome studies present unique challenges that require specific adaptations:

Temporal Confounding Solutions:

- Include time-by-batch interaction terms in the regression model when appropriate

- Use structured covariance matrices to account for within-subject correlations

- Consider stratified correction by time points when batch effects vary substantially across time

Missing Data Handling:

- Implement multiple imputation for irregular sampling intervals before batch correction

- Use subject-specific random effects to account for missingness patterns

- Apply weighted quantile regression to down-weight observations with incomplete longitudinal profiles [4]

Validation Approach:

- Assess preservation of biological trajectories while removing technical artifacts

- Verify that time-dependent biological signals remain intact post-correction

- Check that within-subject correlations are maintained while between-batch differences are reduced [4]

Validation and Interpretation Framework

What metrics and visualizations should researchers use to validate ConQuR's performance?