Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation in Chemistry Labs: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between mobile robotics and fixed automation for chemical research and drug development.

Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation in Chemistry Labs: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between mobile robotics and fixed automation for chemical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both systems, details their specific methodological applications in modern labs—from self-driving laboratories to process chemistry—and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing recent case studies and performance data, it delivers a validated, comparative framework to help scientists and research professionals make informed, strategic decisions on integrating automation to accelerate discovery.

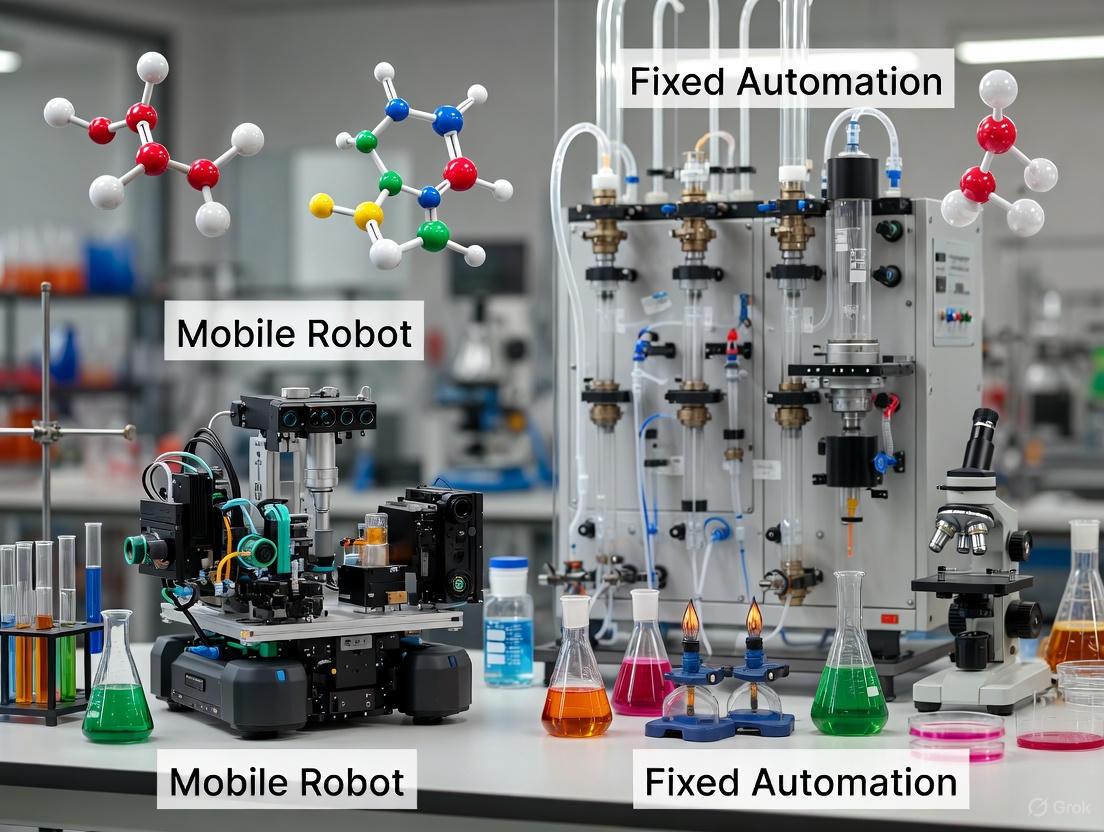

Understanding the Core Technologies: From Fixed Arms to Mobile Chemists

In the landscape of modern chemistry research, the push for faster discovery and higher reproducibility has made automation a central pillar. While mobile robots are emerging for exploratory tasks, fixed automation remains the undisputed champion for applications where precision, power, and repeatability are non-negotiable. This guide objectively compares the performance of fixed robotic systems against mobile alternatives, providing the data-driven insights researchers need to make informed automation decisions.

Fixed vs. Mobile Automation: A Strategic Comparison for Laboratories

Fixed automation, also known as stationary robotics, involves systems that are permanently mounted to perform tasks in a single, optimized location [1] [2]. In industrial settings, they are the "gym bros of automation"—all power, zero cardio—excelling at high-volume, repetitive jobs by focusing all their energy on speed and precision rather than movement [1].

The table below summarizes the core differences between fixed and mobile robots as they apply to a research context.

| Feature | Fixed Automation | Mobile Robots |

|---|---|---|

| Core Strength | Precision, repeatability, and high-power tasks [1] | Flexibility, transport, and exploratory work [1] [3] |

| Typical Lab Tasks | Automated synthesis, repetitive sample analysis, high-throughput screening [4] | Sample transportation between fixed stations, feeding instruments to fixed systems [3] |

| Adaptability to Change | Low; requires reprogramming and potential hardware reconfiguration [1] | High; navigates dynamic environments and reroutes easily [1] [2] |

| Best-Suited Environment | Stable, high-volume processes with consistent workflows [1] | Dynamic labs with changing layouts and multi-step processes across rooms [1] [5] |

| Precision & Repeatability | Exceptional; can achieve variances as low as 0.01 mm [1] | Subject to navigation tolerances; generally lower than fixed systems [2] |

Performance Data: Quantitative Advantages of Fixed Systems

The theoretical strengths of fixed automation translate into measurable performance benefits. A key advantage is enhanced reproducibility, a critical challenge in manual chemistry. Automated chemistry systems precisely control reaction variables like temperature, stirring speed, and dosing, logging data in real-time to eliminate human error and produce reliable, repeatable results [4].

Furthermore, fixed systems drive significant gains in productivity. They can operate 24/7, performing complex multi-step recipes without interruption, which frees up skilled researchers to focus on higher-level analysis and experimental design [4]. This "walk-away time" is a substantial benefit, allowing experiments to run safely overnight or over weekends [4].

While one study noted that automation can sometimes lead to a decline in certain aspects of human performance in bonus-related evaluations, it crucially found that the perceived fairness and trust in the automated process remained unaffected [6].

Inside the Modern Lab: Key Fixed Automation Technologies

Fixed automation in chemistry labs is not a single tool but an ecosystem of integrated technologies. Understanding the components is essential for evaluating their application.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details core components of a advanced fixed automation workflow for synthetic chemistry, as exemplified in modern research [3].

| Item | Function in the Automated Workflow |

|---|---|

| Automated Synthesis Platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) | Performs the physical act of chemical synthesis; handles liquid dosing, mixing, and heating of reactions autonomously [3]. |

| Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (UPLC-MS) | Provides orthogonal analytical data on reaction products, separating components (chromatography) and identifying molecular weights (mass spectrometry) [3]. |

| Benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer | Provides critical structural information about synthesized molecules, acting as a second, orthogonal analysis technique to confirm results [3]. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker Software | Processes data from UPLC-MS and NMR analyses using expert-defined rules to autonomously decide the next experimental steps (e.g., pass/fail, scale-up) [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: An Autonomous Workflow for Exploratory Synthesis

The following diagram and protocol detail a modular workflow for autonomous synthetic chemistry that integrates fixed automation, drawing from a landmark study published in Nature [3].

Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis Workflow

Methodology Summary [3]:

- Synthesis: Reactions are prepared and executed in an automated synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth).

- Sample Preparation: The synthesizer automatically takes an aliquot of the reaction mixture and reformats it into vials suitable for MS and NMR analysis.

- Transport: Mobile robots collect the sample vials and transport them to the separate, fixed analytical instruments. This demonstrates a hybrid model where mobility supports fixed automation.

- Orthogonal Analysis: The samples are analyzed by both UPLC-MS and a benchtop NMR spectrometer. This combination provides complementary data on molecular weight and structure.

- Decision-Making: A heuristic decision-maker algorithm processes the analytical data. It assigns a binary pass/fail grade to each reaction based on pre-defined criteria from domain experts. Reactions that pass both analyses are automatically selected for scale-up, while failed reactions are discarded.

The choice between fixed and mobile automation is not about which is superior, but which is appropriate for the task.

Choose fixed automation if your primary need is precision and repeatability for well-defined, repetitive tasks. It is ideal for high-throughput synthesis, standardized analytical protocols, and any process where hitting the same spot, cycle after cycle, is paramount [1] [4]. Its superior speed and power make it the workhorse for stable, high-volume workflows.

Choose mobile robots if your research demands physical flexibility and adaptation to a changing laboratory environment. They excel in tasks like transporting samples between fixed stations (e.g., from a synthesizer to an NMR) and are better suited for truly exploratory work where the experimental pathway is not fully linear [3] [5].

Ultimately, the most powerful modern laboratories are increasingly adopting a hybrid approach. They leverage fixed automation for its brute strength and precision at dedicated workstations, while employing mobile robots as agile assistants that connect these islands of automation into a seamless, efficient discovery pipeline [1] [3].

The transition towards automated processes in research and development represents a fundamental shift in how scientific discovery is approached. Within chemistry and drug development, two distinct automation philosophies have emerged: fixed automation and mobile robotics. Fixed automation refers to permanent, pre-installed systems designed for repetitive, high-throughput tasks without direct human intervention [7]. In contrast, mobile robotics encompasses autonomous devices that move goods and operate equipment within existing laboratory spaces without requiring fixed infrastructure [7] [8].

The critical distinction lies in their fundamental design principles: fixed automation prioritizes speed and repeatability for predictable workflows, while mobile robotics emphasizes flexibility and adaptability for evolving research environments [9]. This comparison guide objectively examines both approaches within the context of modern chemistry research, where the ability to rapidly reconfigure experimental workflows can significantly accelerate discovery timelines.

Core Operational Comparison

The selection between fixed and mobile automation systems requires a thorough understanding of their performance characteristics across key operational parameters that directly impact research productivity.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation Systems

| Performance Parameter | Mobile Robotics | Fixed Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Setup Time & Reconfiguration | Minimal infrastructure requirements; quickly adaptable [7] [8] | Extensive installation; difficult/expensive to modify [9] |

| Integration with Legacy Equipment | High (can operate standard, unmodified instruments) [3] | Low (typically requires bespoke, integrated equipment) [3] |

| Typical Deployment Scale | Scalable from single units to fleets; suited for brownfield sites [10] | Large-scale, centralized systems; best for greenfield sites [10] |

| Multiplexing Capability (Equipment Sharing) | High (robots can share instruments with humans and other workflows) [3] | None or very low (equipment is typically dedicated and monopolized) [3] |

| Best-Suited Workflow Type | High-mix, low-volume; exploratory research [11] [9] | Low-mix, high-volume; standardized, repetitive tasks [9] |

| Upfront Cost | $$ (Lower initial investment) [12] | $$$$ (High initial investment) [12] |

| Operational Workflow | Parallel, asynchronous tasks [3] | Linear, sequential processing |

Experimental Evidence: Mobile Robots in Exploratory Chemistry

Case Study: Autonomous Synthesis and Analysis

A landmark 2024 study published in Nature demonstrated the capability of a mobile robot system to conduct fully autonomous exploratory synthetic chemistry [3]. The experimental setup provides a compelling template for evaluating mobile robotics in a research environment.

Experimental Protocol: The workflow involved a modular platform where mobile robots operated a Chemspeed ISynth synthesis platform, transported samples to standalone analytical instruments (UPLC-MS and a benchtop NMR spectrometer), and returned samples—all without human intervention [3]. A heuristic decision-maker algorithm then processed the orthogonal NMR and UPLC-MS data to autonomously select successful reactions for further investigation and scale-up.

Key Outcomes: The system successfully performed structural diversification chemistry, identified supramolecular host-guest assemblies, and even conducted photochemical synthesis. Crucially, it characterized reaction outcomes using multiple techniques, mimicking human experimental protocols rather than relying on a single, hard-wired characterization method [3]. This multi-modal analysis is critical for exploratory work where reaction products are unknown or complex.

Quantitative Performance Data

The practical value of automation systems is ultimately determined by their measurable impact on research operations. The following data, synthesized from recent implementations, highlights the performance profile of mobile robotic systems.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from Recent Implementations

| Metric | Mobile Robotics Performance | Context & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Normalization Time | 20-25 minutes per plate (manual process: 45 minutes) [11] | Liquid handling automation in a bioscience lab [11] |

| Volumetric Transfer Consistency | Under 5% Coefficient of Variation (CV) [11] | Precision measurement for sensitive reagents [11] |

| Analytical Instrument Sharing | Successful operation of unmodified, shared NMR & UPLC-MS [3] | Enables use of standard laboratory equipment [3] |

| System Reconfiguration Effort | Minimal (software-driven task reassignment) [11] [8] | Adapting to new experimental protocols |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for a Mobile Robotic Workflow

Implementing a mobile robotics system requires the integration of several key components that work in concert to create a functional automated research environment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & System Components

| Item / Component | Function in the Workflow | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robotic Agent(s) | Physical linkage between modules; handles sample transportation and instrument operation [3]. | Free-roaming robots with multipurpose grippers for manipulating labware [3]. |

| Modular Synthesis Platform | Executes chemical reactions automatically in a centralized location. | Commercial Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer or equivalent automated synthesis platform [3]. |

| Orthogonal Analysis Instruments | Provides diverse characterization data for reliable decision-making. | Standalone, unmodified UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR spectrometers [3]. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker Algorithm | Processes analytical data to autonomously determine subsequent workflow steps. | Customizable software applying experiment-specific "pass/fail" criteria to NMR and MS data [3]. |

| Central Control Software | Orchestrates the entire workflow, coordinating robots, synthesizer, and instruments. | Host computer running control scripts that allow domain experts to develop routines without robotics expertise [3]. |

Workflow Visualization: Mobile Robotics in Action

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical workflow that mobile robots enable in a chemistry research laboratory, demonstrating their unique ability to connect discrete pieces of equipment into a cohesive automated system.

Integrated Mobile Robotics Workflow

This workflow highlights the core advantage of mobile robotics: the creation of a flexible, modular automation loop. The mobile robot acts as the central nervous system, physically connecting specialized but standalone instruments—synthesis, MS, NMR—without requiring them to be permanently and exclusively hardwired together [3]. This preserves the independent utility of each instrument for other researchers or workflows, a key benefit over fixed automation.

The choice between mobile robotics and fixed automation is not about identifying a universally superior technology, but rather about matching the system's capabilities to the research organization's specific needs.

Fixed automation remains a powerful solution for high-volume, repetitive tasks with well-established protocols, such as certain aspects of clinical screening or large-scale reagent production, where its superior speed and precision deliver maximum value [9].

Mobile robotics, however, presents a compelling alternative for exploratory R&D environments like drug discovery and chemistry research. Its strengths in adaptability, seamless integration with existing laboratory equipment, and suitability for high-mix, low-volume workflows directly address the core requirements of innovative research [3] [11]. By enabling scientists to automate complex, multi-step processes without locking them into rigid, single-purpose systems, mobile robotics enhances experimental flexibility and ultimately supports a more dynamic and efficient path to scientific discovery.

In the modern chemistry research laboratory, the adoption of automation is no longer a luxury but a necessity for maintaining competitive advantage. However, the choice between fixed automation systems and mobile robotic platforms presents a fundamental strategic decision centered on core trade-offs: raw throughput against operational flexibility, and precision against scalability. Fixed automation, often characterized by integrated, bespoke systems, excels in high-throughput, repetitive tasks but often at the cost of adaptability. In contrast, emergent mobile robot platforms emulate human researchers by operating existing laboratory equipment, offering unparalleled flexibility for exploratory research at the potential expense of maximum speed. This guide provides an objective comparison of these paradigms, underpinned by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their automation investments.

Throughput vs. Flexibility: A Fundamental Trade-off

In laboratory automation, throughput refers to the number of samples or experiments processed in a given time, while flexibility is the system's ability to adapt to new protocols, workflows, and equipment.

The Fixed Automation Approach: Maximizing Throughput

Fixed or bespoke automated systems are typically engineered for a single, well-defined purpose. They are characterized by tightly integrated components operating on a fixed takt time, which is the rate at which a finished product leaves a production system. This architecture is ideal for applications where the process is stable and the goal is the rapid processing of a large number of identical samples, such as in high-throughput screening (HTS) for drug discovery [11]. A core advantage is the minimization of non-value-added time; samples move directly between dedicated stations without transportation delays.

The Mobile Robot Approach: Prioritizing Flexibility

Mobile robotic agents, such as those described in a Nature study, adopt a different philosophy. They are designed to operate within existing laboratory environments, transporting samples and using standard, unmodified instruments like liquid chromatography–mass spectrometers (UPLC-MS) and benchtop NMR spectrometers [3]. This paradigm mirrors human workflows, where a single robot can service multiple, geographically separated instruments. The key advantage is exceptional flexibility; the workflow can be reconfigured for a new experimental campaign simply by updating the robot's software, without physical re-engineering of the laboratory. This is particularly valuable in exploratory synthesis and research and development (R&D), where protocols change rapidly in response to new data [11].

Comparative Data: Throughput and Flexibility

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Fixed Automation vs. Mobile Robots

| Performance Metric | Fixed Automation System | Mobile Robot System |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput (Samples/Hour) | High (Optimized for repetition) [11] | Lower (Due to transportation time) [3] |

| Flexibility (Protocol Change) | Low (Often requires hardware reconfiguration) [11] | High (Software-driven re-tasking) [3] |

| System Integration | Bespoke, tightly coupled [3] | Modular, loosely coupled [3] |

| Ideal Use Case | High-throughput screening, routine analysis [11] | Exploratory research, multi-step synthesis [3] |

| Upfront Cost & Complexity | High (Custom engineering) [3] | Potentially lower (Leverages existing lab equipment) [3] |

Precision vs. Scalability: Strategic Scaling Decisions

Precision in this context refers to the accuracy and reproducibility of experimental operations and results. Scalability is the ease with which an automation solution can be expanded, either in capacity (vertical scaling) or in functional scope (horizontal scaling).

Precision in Laboratory Automation

Both fixed and mobile systems can achieve high levels of precision, but through different means. Fixed automation guarantees precision through rigid mechanical positioning and hard-wired processes. Mobile robots, conversely, must employ advanced localization and control algorithms to achieve repeatable manipulation and transportation. In practice, both can perform precise liquid handling, with automated systems demonstrating coefficients of variation (CV) under 5% for volumetric transfers, a precision comparable to careful manual pipetting [11]. The defining difference is that precision in a fixed system is a built-in characteristic, while in a mobile system it is a dynamically achieved outcome.

Scalability Pathways

Scalability is a key differentiator. Fixed systems are scaled vertically; to increase throughput, one must enhance the capability of a single node (e.g., by adding a faster robot arm or more modules to a line), which is ultimately hardware-constrained [13]. Mobile robot systems are inherently suited for horizontal scaling. As stated in the Nature article, "there is no limit to the number of instruments that can be incorporated under this paradigm, other than those imposed by laboratory space" [3]. One can add more mobile agents to a fleet or more standard instruments to the laboratory network, providing a more flexible and potentially cost-effective path to expansion.

The Data Scaling Perspective

The relationship between model or data scale and performance offers a parallel to physical automation. In AI-driven labs, larger models generally show superior performance and greater resilience. For instance, a study on large language models (LLMs) found that larger models (e.g., 70B parameters) maintain high accuracy even when quantized to 4-bit precision to save memory, outperforming smaller models (e.g., 7B) running at higher precision under a similar memory budget [14]. This principle of "scale confers robustness" can inform the design of AI controllers for both fixed and mobile automated labs; a more capable AI brain can potentially compensate for physical limitations.

Table 2: Scaling and Performance of AI Models for Laboratory Control

| Model Scale | Precision | Memory Use | Performance on Complex Tasks | Resilience to Precision Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (e.g., 7B params) | 32-bit | 28 GB [14] | Moderate | Low |

| Small (e.g., 7B params) | 4-bit | 7 GB [14] | Significantly Reduced | - |

| Large (e.g., 70B params) | 32-bit | 168 GB [14] | High | High |

| Large (e.g., 70B params) | 4-bit | 42 GB [14] | Remains High | - |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ground these comparisons, below are detailed methodologies from key studies demonstrating mobile robotic systems in action.

Protocol: Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis using Mobile Robots

This protocol is derived from the modular workflow published in Nature [3].

1. Synthesis Setup: A Chemspeed ISynth automated synthesizer is loaded with starting materials. The mobile robot(s) are not involved in this initial stage. 2. Reaction Execution: The synthesizer performs the parallel reactions. Upon completion, it automatically prepares aliquots in standard vials for UPLC-MS and NMR analysis. 3. Sample Transport: A mobile robot equipped with a gripper picks up the prepared sample vials and navigates through the laboratory to deliver them to the UPLC-MS instrument and the benchtop NMR spectrometer. This transportation is the critical mobile component. 4. Autonomous Analysis: The instruments, once loaded by the robot, run their pre-programmed analysis methods (e.g., a 5-minute gradient elution for UPLC-MS, a 2-minute proton NMR pulse sequence). 5. Data Integration and Decision Making: Analytical data (chromatograms, mass spectra, NMR spectra) are automatically processed by a heuristic decision-maker algorithm. This algorithm uses pre-defined, domain-expert rules to assign a binary "pass/fail" grade to each reaction based on the orthogonal data. 6. Closed-Loop Action: Based on the decision, the system autonomously instructs the synthesizer on the next steps. For example, reactions that "pass" are selected for scale-up or further diversification in a subsequent synthetic step, recreating the human "design-make-test-analyze" loop without intervention.

Workflow Visualization: Mobile Robot vs. Fixed Automation

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical differences in the workflow of a mobile robot system versus a fixed automation system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The transition to automated chemistry, particularly using mobile robots, relies on a foundation of standardized materials and software. The following table details key components of this toolkit as evidenced in the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for an Automated Chemistry Laboratory

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Role in Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Synthesis Platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) | A robotic platform for precisely dispensing reagents and executing reactions in parallel [3]. | Serves as the core "make" module, preparing samples for analysis. |

| Orthogonal Analysis Instruments (UPLC-MS, NMR) | Provides complementary characterization data (molecular weight/identity and structural information) [3]. | The key "test" modules. Their standard design allows integration by mobile robots. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker Algorithm | Software that processes analytical data using expert-defined rules to autonomously decide the next experimental steps [3]. | The "brain" that closes the autonomous loop, replacing human judgment for specific criteria. |

| Mobile Robotic Agent | A free-roaming robot capable of navigating the lab and manipulating standard sample vials and instrument doors [3]. | The physical integrator, providing flexibility by linking disparate, unmodified instruments. |

| Standardized Sample Vials | Consumable vials compatible with both the synthesizer and the analysis instruments. | Ensures seamless hand-off between different modules and robots, preventing "incompatibility deadlocks." |

| Central Data Management Platform | Software that unifies data from synthesizers, analyzers, and decision algorithms [15]. | Creates a single source of truth, enabling traceability and providing clean data for AI/ML analysis. |

The choice between mobile robots and fixed automation is not about identifying a universally superior option, but about matching the system's strengths to the research problem. Fixed automation remains the champion of throughput and precision for well-defined, repetitive tasks in environments with low variability. Conversely, mobile robotic platforms are the emerging solution for flexibility and scalability, enabling autonomous exploratory chemistry in dynamic R&D settings by leveraging existing laboratory infrastructure. As the field progresses, the integration of more robust AI—inspired by the resilience of large-scale models—will further blur these lines, potentially leading to hybrid systems that offer both high throughput and adaptive intelligence. For the modern research lab, the strategic evaluation of the throughput-flexibility and precision-scalability trade-offs is the first critical step toward successful and sustainable automation.

The integration of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally transforming scientific laboratories, shifting the research paradigm from manual, time-consuming processes to highly efficient, automated factories of discovery. In the context of chemistry research and drug development, this transition is characterized by a spectrum of automation, ranging from simple assistive devices to fully autonomous systems that require no human intervention. The core distinction lies in the division of labor between human and machine: automated experiments are those where researchers make the decisions, while autonomous experiments are those where machines record and interpret analytical data to make decisions based on them [3]. This evolution is critical for accelerating scientific progress, as traditional trial-and-error approaches are often slow and labor-intensive, delaying breakthroughs in fields like medicine and energy [16].

The drive toward automation is fueled by its ability to enhance reproducibility, minimize human error, and allow scientists to focus on higher-level creative research questions [16] [17]. Furthermore, robotic systems can handle hazardous substances, significantly reducing safety risks for lab personnel [16]. This guide will objectively compare two dominant architectural paradigms enabling this transition: mobile robotics and fixed automation systems. By examining their performance, implementation, and suitability for different research environments, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for selecting the optimal automation strategy.

The Five Levels of Laboratory Automation

A useful framework for understanding this transition defines five distinct levels of laboratory automation [16]. This hierarchy helps in assessing progress, establishing safety protocols, and setting future research goals.

Table 1: The Five Levels of Laboratory Automation

| Level | Name | Description | Typical Human Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Assistive Automation | Automation of individual tasks (e.g., liquid handling) while humans handle the majority of the workflow. | Handles most of the work, including setup and execution. |

| A2 | Partial Automation | Robots perform multiple sequential steps, but humans remain responsible for setup and supervision. | Responsible for setup and active supervision. |

| A3 | Conditional Automation | Robots manage entire experimental processes. Human intervention is required for unexpected events. | Required to intervene when unexpected events arise. |

| A4 | High Automation | Robots execute experiments independently, setting up equipment and reacting to unusual conditions autonomously. | Not required for routine operation, but still oversees the system. |

| A5 | Full Automation | Robots and AI systems operate with complete autonomy, including self-maintenance, safety management, and experimental decision-making. | Not required for operation; the system is self-sufficient. |

Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation: A Comparative Analysis

The physical implementation of automation falls into two primary categories: mobile robots and fixed automation. Mobile robots are free-roaming agents that transport samples and operate equipment across a distributed laboratory space [3]. In contrast, fixed automation (or bespoke automated equipment) involves physically integrated systems where samples are transferred via conveyors or robotic arms within a single, dedicated unit [3].

Performance and Flexibility Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Mobile Robot vs. Fixed Automation

| Feature | Mobile Robot Automation | Fixed Automation |

|---|---|---|

| System Architecture | Modular, distributed, and connected by mobile robots [3]. | Integrated, bespoke, and physically hard-wired [3]. |

| Instrument Integration | High flexibility; can incorporate any instrument within navigation range without physical redesign [3]. | Low flexibility; limited to pre-integrated instruments; expansion is complex and costly [3]. |

| Equipment Sharing | Enables sharing of high-value equipment (e.g., NMR, MS) with human researchers [3]. | Typically monopolizes equipment for the automated workflow. |

| Characterization Capability | Supports multi-modal analysis (e.g., UPLC-MS and NMR) by moving samples between different stations [3]. | Often relies on a single, hard-wired characterization technique due to integration complexity [3]. |

| Upfront Investment | Potentially lower for initial setup and incremental expansion. | Often very high due to bespoke engineering and integration [18]. |

| Best Suited For | Exploratory research, multi-step syntheses, and labs requiring diverse analytical techniques [3]. | High-throughput, repetitive analysis, and dedicated production lines [3]. |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

A landmark study published in Nature demonstrated the efficacy of a mobile robotic system for exploratory synthetic chemistry. The platform used mobile robots to link an automated synthesizer (Chemspeed ISynth) with separate, unmodified analysis instruments, including a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS) and a benchtop NMR spectrometer [3].

Experimental Protocol: The workflow involved:

- Synthesis: The Chemspeed platform performed chemical reactions in parallel.

- Sample Aliquoting: The synthesizer prepared aliquots of the reaction mixtures for MS and NMR analysis.

- Transport & Handling: Mobile robots collected the samples and transported them to the respective instruments.

- Data Acquisition & Analysis: The instruments performed orthogonal measurements, and a heuristic decision-maker processed the data to grade reactions as pass/fail.

- Decision & Iteration: The system used these results to autonomously decide which reactions to scale up or replicate, checking for reproducibility [3].

Key Outcome: This modular approach successfully conducted autonomous multi-step syntheses and identified supramolecular host-guest assemblies, showcasing an ability to handle complex, open-ended chemical problems that are less suited to optimization of a single, known metric [3].

In the realm of biotechnology, a study in Scientific Reports detailed an Autonomous Lab (ANL) system that used a transfer robot (the Brooks PF400) to connect modular devices for culturing, preprocessing, and analysis [17]. The system employed Bayesian optimization to autonomously run a closed loop from culturing through to analysis and hypothesis formulation. In a case study optimizing medium conditions for a glutamic acid-producing E. coli strain, the ANL successfully improved both the cell growth rate and maximum cell growth by optimizing the concentrations of four key nutrients (CaCl₂, MgSO₄, CoCl₂, and ZnSO₄) [17]. This demonstrates the power of integrated, AI-driven systems to tackle complex bioproduction challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for an Automated Lab

Building an automated laboratory, whether mobile or fixed, requires a suite of core technologies. The following table details key research reagent solutions and essential hardware/software components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Core Technologies

| Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Research Reagents | M9 Minimal Medium | A defined medium containing only essential nutrients, allowing for precise optimization of additional components [17]. |

| Trace Elements (e.g., CoCl₂, ZnSO₄) | Act as cofactors for enzymes; their concentration can be optimized to regulate multi-step enzymatic reactions in pathways like glutamic acid biosynthesis [17]. | |

| Basic Components (e.g., CaCl₂, MgSO₄) | Affect cell growth and osmotic pressure; optimization is crucial for balancing growth and product yield [17]. | |

| Core Technologies | Automated Synthesis Platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) | Executes chemical reactions autonomously, including sample preparation and aliquoting [3]. |

| Mobile Robot (e.g., Brooks PF400) | Provides physical linkage between modular stations by transporting samples and operating equipment [3] [17]. | |

| Analytical Instruments (UPLC-MS, NMR) | Provides orthogonal, multimodal data for comprehensive reaction characterization, which is essential for reliable autonomous decision-making [3]. | |

| Liquid Handler (e.g., Opentrons OT-2) | Automates precise liquid transfer tasks in workflows such as sample reformatting or PCR setup [17]. | |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | An AI-driven approach that models the relationship between experimental parameters (e.g., concentration) and outcomes (e.g., growth) to intelligently suggest the next best experiment [17]. |

Workflow Visualization: Mobile Robot Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow in a modular, mobile robot-driven automated laboratory.

The landscape of laboratory automation presents a clear spectrum, from assistive tools that augment human capability to fully autonomous systems that can independently conduct discovery research. The choice between mobile robot and fixed automation architectures is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the research goal. Mobile robots offer unparalleled flexibility and modularity, making them ideal for exploratory chemistry and dynamic environments that require diverse analytical techniques [3]. Fixed automation systems excel in high-throughput, dedicated applications where maximum speed and reproducibility for a specific, repeated workflow are paramount.

The future of laboratory science lies in the seamless integration of robotics, data infrastructure, and AI. As noted by researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill, the integration of AI is key to advancing beyond mere physical automation to fully autonomous research cycles [16]. Successfully implementing these systems will require a new generation of scientists skilled in both their domain expertise and in collaborating with these advanced technologies, ultimately leading to faster, safer, and more reliable scientific breakthroughs.

From Synthesis to Analysis: Deploying Mobile and Fixed Systems in Real-World Chemistry

In the landscape of contemporary chemical research, automation has become a cornerstone for achieving new levels of efficiency, reproducibility, and discovery. This guide focuses on fixed automation systems, which include benchtop liquid handlers and integrated high-throughput synthesis platforms that are physically stationary. These systems are characterized by their precision, repeatability, and high-speed operation within a confined workspace, making them ideal for standardized, high-volume tasks [1]. Unlike mobile robotic systems that navigate laboratory spaces to connect distributed instruments, fixed automation is typically dedicated to specific workflows such as PCR setup, serial dilution, compound screening, and parallel synthesis [19].

The drive toward automation is reshaping laboratories globally. The laboratory automation market, valued at $5.2 billion in 2022, is projected to grow to $8.4 billion by 2027, driven by demands for higher throughput, improved accuracy, and cost efficiency in pharmaceutical, biotech, and environmental sectors [20]. Similarly, the automated liquid handling market specifically is expected to rise from USD 1.39 billion in 2025 to USD 2.57 billion by 2033 [19]. This growth underscores a fundamental shift in how scientific research is conducted, with fixed automation playing a pivotal role in this transformation by providing the foundational tools for accelerating the design-make-test-analyze cycle in chemistry and drug discovery.

Performance Comparison: Fixed vs. Mobile Automation

Selecting the appropriate automation strategy requires a clear understanding of how fixed and mobile systems perform across key operational parameters. The table below provides a comparative summary based on available data and documented implementations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fixed and Mobile Automation Systems

| Performance Metric | Fixed Automation (Benchtop Systems) | Mobile Robotic Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Precision, speed, and high-throughput in confined workflows [1] | Flexibility, adaptability, and connectivity of distributed equipment [21] |

| Typical Throughput | Very high for dedicated tasks (e.g., plate replication, PCR setup) [19] | Lower overall throughput due to transportation time between stations [22] |

| Operational Flexibility | Low; optimized for specific, repetitive protocols [1] | High; can be reprogrammed to access different instruments and perform diverse tasks [21] |

| Precision & Repeatability | Exceptional; sub-microliter liquid handling with minimal variance [19] | Subject to potential variances from navigation and manipulation in dynamic environments |

| Integration Complexity | Moderate; can be integrated into workcells but primarily standalone [19] | High; requires orchestration with laboratory infrastructure (doors, elevators) and instruments [23] |

| Space Utilization | Defined benchtop footprint | Uses existing laboratory space without monopolizing equipment [3] |

| Best-Suited Applications | Drug discovery assays, genomic research, serial dilution, high-throughput screening [19] | Exploratory synthesis, multi-step processes requiring diverse characterization [3] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To illustrate the implementation of fixed automation, the following section details two key experimental protocols that highlight its capabilities in high-throughput synthesis and analysis.

Protocol: Parallel Synthesis for Structural Diversification

This protocol, derived from autonomous laboratory research, demonstrates a fixed automation workflow for synthesizing a library of small molecules, a common bottleneck in drug discovery [3].

- Objective: To autonomously synthesize a library of ureas and thioureas through combinatorial condensation and subsequently identify successful reactions for scale-up.

- Automated Equipment Used:

- Synthesis Module: Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer or similar automated platform.

- Analysis: Integrated or nearby UPLC-MS and Benchtop NMR.

- Procedure:

- Reagent Setup: The automated platform is loaded with stock solutions of three alkyne amines and one isothiocyanate and one isocyanate.

- Parallel Synthesis: The liquid handling system autonomously dispenses specified volumes of amines and electrophiles into reaction vessels in a combinatorial array, initiating reactions under controlled conditions.

- Automated Sampling and Quenching: Upon completion, the system takes an aliquot from each reaction mixture and quenches it as needed.

- Sample Reformating: The platform reformats the aliquots into appropriate vials for UPLC-MS and NMR analysis.

- Orthogonal Analysis: Samples are transferred (manually or via mobile robot) to UPLC-MS and NMR for characterization. In a fully fixed system, these instruments may be directly integrated into the workcell.

- Heuristic Decision-Making: A pre-defined algorithm processes the UPLC-MS and NMR data, giving each reaction a binary pass/fail grade. Reactions that pass both analyses are automatically selected for subsequent scale-up or further elaboration [3].

- Key Performance Metric: The system's efficacy is measured by its ability to correctly identify successful reactions based on orthogonal data without human intervention, enabling an uninterrupted design-make-test-analyze cycle.

Protocol: Automated Process Chemistry and Analysis

This protocol showcases a fixed, modular workflow for process chemistry, demonstrating robustness and reproducibility matching human performance [22].

- Objective: To perform automated process chemistry for scalable synthesis, including reaction, work-up, purification, and analysis.

- Automated Equipment Used:

- Synthesis Reactor: Automated synthesis reactor (e.g., in a fumehood).

- Liquid Handling: Robotic arm for sample transfer and liquid handling.

- Analysis: UHPLC-MS system.

- Procedure:

- Synthesis: The reactor executes the synthetic sequence (e.g., paracetamol synthesis) from starting materials to product.

- Work-up and Quenching: The system automatically quenches the reaction and performs a liquid-liquid extraction if required.

- Sample Transfer: A stationary robotic arm retrieves a sample vial from the reactor and transports it to the UHPLC-MS for injection.

- Chromatographic Analysis: The UHPLC-MS runs a predefined method to separate and analyze the product, quantifying yield and purity.

- System Cleaning: The robotic arm cleans the reactor and associated fluidic paths to prevent cross-contamination between experimental runs.

- Iteration: The system initiates the next experiment based on the analytical results or a predefined schedule.

- Key Performance Metric: The reported performance for this workflow includes reaction yields and purity matching human chemists, with a potential weekly reaction output 12 times greater than that of a human process chemist in an industrial setting when running multiple reactors around the clock [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision-making process of an autonomous fixed system, as described in the parallel synthesis protocol.

Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of fixed automation relies on a suite of specialized equipment and reagents. The table below details key components for setting up a high-throughput synthesis and liquid handling workstation.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for Automated workflows

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Programmable system for precise, high-volume dispensing of liquids. Key for PCR setup, serial dilution, and reagent addition [19]. |

| Standalone Benchtop Workstation | A compact, fixed system that automates specific tasks like pipetting or plate washing on a benchtop, conserving space [24]. |

| Chemspeed ISynth Platform | An example of an automated synthesis platform used for parallel synthesis in exploratory chemistry and library generation [3]. |

| UPLC-MS / LC-MS | Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry for rapid separation and identification of reaction products [3] [22]. |

| Benchtop NMR Spectrometer | A compact NMR instrument used for structural analysis and verification of synthesized compounds, integrable into automated workflows [3]. |

| Disposable Pipette Tips | Sterile, single-use tips for liquid handlers to prevent cross-contamination between samples, crucial for reliable results [19]. |

| Microplates & Labware | Standardized plates (e.g., 96-well, 384-well) and tubes that are compatible with automated handling systems [25]. |

| Heuristic Decision Algorithm | Customizable software that processes analytical data (UPLC-MS, NMR) to autonomously decide the next experimental steps [3]. |

Fixed automation systems, exemplified by high-throughput benchtop liquid handlers and synthesis platforms, are powerful tools that deliver unmatched precision, speed, and reproducibility for well-defined, high-volume tasks. Their strength lies in optimizing specific workflows such as assay preparation, compound screening, and parallel synthesis, which are fundamental to modern drug discovery and chemical research.

The choice between fixed and mobile automation is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with research goals. Fixed systems excel in dedicated, high-throughput environments where task repetition and precision are paramount. In contrast, mobile robotic systems offer a broader, more flexible form of automation that can connect disparate instruments for exploratory, multi-step chemistry [3] [21]. The emerging paradigm in advanced laboratories is a hybrid approach, where mobile robots transport samples to and from fixed, high-performance workstations, leveraging the strengths of both automation strategies to create a truly integrated and self-driving laboratory [20].

The integration of robotics into chemical laboratories represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach discovery and synthesis. This evolution presents a critical choice: to implement fixed, hardwired automation or to adopt a flexible, modular approach using mobile robots. Fixed automation systems, typically built for high-throughput, dedicated tasks, involve significant financial investment and permanent reconfiguration of laboratory space [26]. In contrast, a modular strategy utilizing mobile robots to connect standard, unmodified laboratory instruments offers a path to automation that preserves existing infrastructure and shares resources with human researchers [3]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these two approaches, focusing on their performance in exploratory synthesis, where chemical outcomes are uncertain and multiple analytical techniques are required for unambiguous characterization. We objectively evaluate a documented implementation of the modular mobile robot approach against the established benchmarks of fixed automation, providing the experimental data and methodologies necessary for research professionals to make informed decisions.

Comparative Framework: Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their core architecture. Fixed automation creates a closed, optimized ecosystem, often with integrated, dedicated analytical tools. The modular mobile robot approach constructs an open, dynamic network where robots act as mobile agents, physically transporting samples between standalone, high-end instruments [3]. The following table summarizes the key comparative characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Mobile Robot and Fixed Automation Approaches

| Feature | Mobile Robot (Modular Approach) | Fixed Automation (Integrated Approach) |

|---|---|---|

| System Architecture | Open, distributed, and reconfigurable [3] | Closed, centralized, and hardwired [3] |

| Laboratory Integration | Uses standard, unmodified instruments; shares equipment with human researchers [3] [27] | Often requires bespoke, custom-engineered equipment [3] |

| Typical Analytical Scope | Multi-modal, orthogonal techniques (e.g., UPLC-MS & NMR combined) [3] | Often reliant on a single, hardwired characterization technique [3] |

| Upfront Financial Outlay | Potentially lower; leverages existing lab assets [3] | Typically high ($50,000 to $300,000+) [26] |

| Operational Flexibility | High; easily reprogrammed for new workflows and expanded with new instruments [3] | Low; optimized for a specific, narrow workflow [26] |

| Ideal Research Environment | Exploratory chemistry, multi-product facilities, academic labs [3] | High-volume production, dedicated quality control, routine synthesis [26] |

Experimental Performance and Benchmarking Data

A landmark study published in Nature provides a direct performance benchmark for the modular mobile robot approach. The system was deployed for three distinct exploratory chemistry campaigns: structural diversification, supramolecular host-guest chemistry, and photochemical synthesis [3]. The core performance metric was the system's ability to autonomously make correct "pass/fail" decisions on reaction outcomes, replicating human expert judgment using orthogonal data from UPLC-MS and NMR.

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Exploratory Synthesis Campaigns

| Chemistry Campaign | Key Experimental Task | Decision-Making Basis | Reported Autonomous System Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversification | Parallel synthesis of ureas/thioureas; scale-up and elaboration of successful substrates [3] | Heuristic analysis of UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR data [3] | Successful emulation of end-to-end human-led process; autonomous decision to scale-up and diverge successful reactions [3] |

| Supramolecular Assembly | Identification of successful synthetic macrocyclic hosts from a dynamic combinatorial library [3] | Heuristic analysis of UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR data [3] | Correct identification of a known host molecule and a new, previously unreported self-assembled host [3] |

| Photochemical Synthesis | Exploration of photocatalytic hydroaminoalkylation reactions [3] | Heuristic analysis of UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR data [3] | Autonomous discovery of a new, high-performing catalytic reaction condition [3] |

| Functional Assay | Evaluation of host-guest binding properties for identified supramolecular hosts [3] | Analysis of fluorescence quenching data via UPLC-MS [3] | Successful extension beyond synthesis to autonomous functional testing [3] |

The system demonstrated a key advantage in supramolecular chemistry, where reactions can produce multiple products from the same starting materials. Its ability to process orthogonal data streams (UPLC-MS and NMR) with a "loose" heuristic was crucial for remaining open to novel discoveries, unlike optimization-focused algorithms that target a single, pre-defined outcome [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: The Modular Workflow in Action

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the methodology, the core experimental protocol from the Nature study is detailed below [3].

The modular workflow integrates synthesis, sample handling, analysis, and decision-making into a continuous, autonomous cycle. The following diagram visualizes this process and the physical layout of the modular laboratory.

Diagram Title: Modular Mobile Robot Workflow for Autonomous Chemistry

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Synthesis: The automated synthesis platform (Chemspeed ISynth) performs parallel reactions based on an initial input recipe.

- Sample Aliquoting and Reformating: Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer automatically takes an aliquot of each reaction mixture and reformats it into standard vials suitable for the UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR instruments.

- Mobile Robot Transport: One or more mobile robots, equipped with specialized grippers, retrieve the sample vials. They navigate freely through the laboratory to transport samples to the specific locations of the UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR spectrometers. The robots operate these instruments by triggering pre-configured methods for data acquisition.

- Orthogonal Data Acquisition: The UPLC-MS and NMR instruments, which are standard commercial models with minimal or no physical modification, analyze the samples. The raw analytical data (chromatograms, mass spectra, and NMR spectra) are saved to a central database.

- Heuristic Decision-Making: A software-based decision-maker, programmed with rules defined by domain experts, processes the analytical data.

- UPLC-MS Analysis: A pass/fail grade is assigned by checking for expected mass-to-charge (m/z) peaks against a pre-computed lookup table and by detecting significant changes in chromatographic traces using dynamic time warping.

- NMR Analysis: A pass/fail grade is assigned by analyzing the ¹H NMR spectrum for reaction-induced changes, also using dynamic time warping to compare spectra.

- The binary results from both techniques are combined. In the referenced study, a reaction typically needed to pass both analyses to be considered a "hit" and proceed to the next stage [3].

- Autonomous Execution of Next Steps: Based on the decision, the system autonomously instructs the synthesis platform to proceed with the next set of actions. This could include:

- Scale-up: Re-running a successful reaction at a larger scale.

- Replication: Repeating a reaction to confirm reproducibility of a screening hit.

- Structural Diversification: Using a successful intermediate in a subsequent, different reaction.

- Functional Assay: Automatically proceeding to test the function of a synthesized compound (e.g., host-guest binding).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details the core components and their functions that enabled the modular robotic laboratory as described in the primary research [3].

Table 3: Essential Components for a Modular Robotic Laboratory

| Component Name | Type/Model Cited | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot | Kuka mobile robot (or similar) [28] | Physical agent for sample transport and operation of instrument interfaces. |

| Automated Synthesizer | Chemspeed ISynth [3] [27] | Execution of parallel chemical syntheses with automated liquid handling and aliquotting. |

| UPLC-MS System | UltraPerformance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry [3] | Provides orthogonal analytical data on product mixture composition and molecular weight. |

| Benchtop NMR | 80 MHz Benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometer [3] | Provides orthogonal analytical data on molecular structure and reaction-induced changes. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker | Custom Python scripts with expert-defined rules [3] | The "brain" that processes UPLC-MS and NMR data to autonomously decide the next experimental steps. |

| Central Control Software | Custom software suite [3] | Orchestrates the entire workflow, coordinating robot actions, synthesis, and analysis. |

Discussion and Outlook

The experimental data demonstrates that the modular mobile robot approach is not merely a logistical alternative but a fundamentally different paradigm suited for exploratory research. Its strength lies in leveraging the existing, high-quality infrastructure of a modern chemistry laboratory—sharing NMR, MS, and other instruments with human researchers—without requiring costly, permanent dedication of these resources [3]. This makes high-level automation more accessible to academic and industrial R&D groups without the capital for a fully hardwired facility.

The fixed automation model remains powerful for high-throughput, dedicated tasks where throughput and reliability for a narrow scope of work are the primary objectives [26]. However, for the complex, open-ended problems that define the frontiers of chemical research, the flexibility, data richness, and resource-sharing of the modular mobile approach offer a compelling and proven alternative. The convergence of this hardware paradigm with increasingly sophisticated AI and large language models (LLMs) for planning and decision-making promises to further accelerate the pace of autonomous chemical discovery [28] [29].

The automation of process chemistry represents a pivotal advancement in pharmaceutical and agrochemical development, aiming to transform labor-intensive and time-consuming route scouting and optimization into a streamlined, high-throughput endeavor. The central debate for modern research facilities revolves around the choice of automation architecture: mobile robotic systems that navigate existing laboratory spaces versus fixed automation workstations that perform dedicated, integrated workflows. Mobile robots, as exemplified by recent research, are free-roaming agents that leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to physically operate multiple, discrete pieces of standard laboratory equipment [3] [5]. In contrast, fixed automation typically consists of bespoke, benchtop-scale systems where robotic arms and analytical instruments are physically hard-wired into a single, optimized unit [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two paradigms, drawing on the latest experimental data and research to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Mobile Robots vs. Fixed Automation

The following tables summarize key performance characteristics and a direct comparison based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Mobile Robotic Chemistry Systems

| Performance Metric | Reported Result/Characteristic | Context and Measurement Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Weekly Reaction Output | Up to 12x that of a human chemist [22] | Estimated for a system operating multiple reactors in an industrial setting [22] |

| Decision-Making Speed | Near-instantaneous (minutes) [5] | AI processing of analytical data (UHPLC-MS, NMR) to decide next steps [5] |

| Operational Duration | 21+ hours unattended (3 back-to-back experiments) [22] | Demonstration of continuous, round-the-clock operation [22] |

| Equipment Integration | Modular; interfaces with UHPLC-MS, NMR, synthesis reactors [3] | Uses standard, commercially available instruments with minimal redesign [3] |

| Analytical Orthogonality | High (UPLC-MS & NMR) [3] | Uses multiple, orthogonal techniques for robust product characterization [3] |

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Mobile Robot and Fixed Automation Systems

| Feature | Mobile Robot Systems | Fixed Automation Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Distributed, modular workflow [3] | Integrated, bespoke workflow [3] |

| Infrastructure Flexibility | High; shares equipment with human researchers [3] [5] | Low; equipment is typically dedicated and monopolized [3] |

| Scalability | Inherently scalable by adding more mobile robots [5] | Limited by the physical footprint and capacity of the unit [15] |

| Upfront Instrument Cost | Potentially lower; can utilize existing lab equipment [3] | Typically high due to custom engineering and integration [3] |

| Characterization Flexibility | High; can employ multiple, diverse analytical techniques [3] | Often limited to a single, hard-wired characterization technique [3] |

| Suitability for Exploratory Chemistry | High; heuristic AI can handle diverse, multi-product outcomes [3] | Lower; better suited for optimizing a single, known figure of merit (e.g., yield) [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Methodology for Mobile Robotic Synthesis

The experimental protocols for mobile robotic systems, as validated in recent peer-reviewed studies, involve a cyclic, autonomous process [3] [5].

- Synthesis Module Setup: An automated synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) prepares reactions in parallel. It aliquots the resulting reaction mixtures and reformats them into standard vials for MS and NMR analysis [3].

- Sample Transport and Handling: Mobile robots, equipped with anthropomorphic grippers, collect the sample vials from the synthesizer. They transport these vials across the laboratory to the respective analytical instruments (UPLC-MS and a benchtop NMR spectrometer) [3] [5].

- Autonomous Data Acquisition: The robots interface with the instruments to load the samples. Customizable Python scripts then trigger the analytical methods (e.g., UPLC-MS method, NMR shimming and acquisition) without human intervention [3].

- AI-Driven Decision-Making: The raw analytical data (chromatograms, mass spectra, NMR spectra) are saved to a central database. A heuristic decision-making algorithm, designed by domain experts, processes this orthogonal data. It assigns a binary "pass/fail" grade to each reaction based on pre-defined criteria (e.g., presence of target mass, cleanliness of NMR spectrum). Reactions that pass both analyses are automatically selected for the next stage, such as scale-up or diversification [3].

- Reactor Reset: The mobile robot can perform maintenance tasks, such as cleaning the synthesis reactor between experimental runs, to enable continuous operation [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a mobile robotic chemist system.

Mobile Robotic Chemist Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For the researchers implementing these systems, the core components extend beyond chemicals to encompass the integrated hardware and software platforms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent and Platform Solutions

| Item / Platform | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Automated Synthesis Reactor | Platforms like Chemspeed ISynth perform precise, automated liquid handling, mixing, and heating for reaction execution [3]. |

| Mobile Robotic Agent | Free-roaming robots (e.g., 1.75m tall units) provide physical linkage between modules, transporting samples and operating equipment [5]. |

| Orthogonal Analytics | Coupled systems like UHPLC-MS and Benchtop NMR Spectrometer provide complementary data for definitive reaction outcome characterization [3]. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker | Customizable algorithm that replaces human judgment to autonomously grade results and select successful reactions based on analytical data [3]. |

| Central Control Software | Orchestrating software that coordinates the entire workflow, from synthesis commands to robot navigation and data aggregation [3]. |

The empirical data demonstrates that mobile robotic systems offer a distinct paradigm of flexibility, modularity, and collaborative potential with human researchers, making them particularly suited for exploratory chemistry and process development where workflows and analytical needs may evolve [3] [5]. Their ability to leverage existing, high-quality laboratory instrumentation without monopolization can lower barriers to entry and enhance resource utilization. In contrast, fixed automation systems excel in environments dedicated to high-throughput, repetitive optimization of known reactions where maximum speed for a specific, narrow task is the primary objective [3] [15]. The choice between these architectures is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the research facility's goals, existing infrastructure, and the nature of the chemical challenges being addressed.

This guide compares the implementation of closed-loop workflows in chemical research using two distinct automation paradigms: mobile robots and fixed automation systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these approaches significantly impacts the flexibility, scalability, and efficiency of autonomous discovery processes.

In modern chemical research, a closed-loop workflow represents the pinnacle of automation, integrating the entire Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle into a seamless, autonomous system. Artificial intelligence designs experiments, robotic systems execute synthetic procedures, analytical instruments characterize products, and data analysis algorithms interpret results to inform the next cycle of experimentation [30] [16]. The core distinction lies in how these components are physically and digitally integrated—either through fixed, hardwired automation or through flexible, mobile robotic systems that navigate existing laboratory environments.

The evolution toward fully autonomous laboratories is often categorized in five levels, progressing from assistive automation (A1) where humans perform most work, to full automation (A5) where robots and AI operate with complete autonomy, including self-maintenance and safety management [16]. Most current implementations reside at levels 2-4, where the interplay between physical execution systems and AI decision-making creates distinct advantages and limitations for mobile versus fixed approaches.

System Architectures and Integration Methods

Mobile Robot Architectures

Mobile robotic systems for chemical research employ free-roaming robots that physically transport samples between standalone instruments, mimicking human researcher behaviors. This approach creates a modular laboratory workflow where synthesis platforms, analytical instruments, and other equipment remain physically separate but are connected via robotic mobility [3].

A documented implementation uses mobile robots to operate a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer, transport samples to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and benchtop NMR spectrometers, and return them for further processing [3]. The physical linkage occurs through mobile manipulation rather than fixed tubing or conveyors. This architecture particularly suits exploratory synthesis where reactions can yield multiple potential products requiring orthogonal characterization techniques [3].

The AI decision-making layer in these systems often employs heuristic decision-makers that process multimodal analytical data (e.g., combining NMR and UPLC-MS results) to select successful reactions for further investigation [3]. This replicates human decision-making protocols where multiple characterization techniques inform experimental progression.

Fixed Automation Architectures

Fixed automation systems typically consist of hardwired components physically integrated into a continuous workflow. These systems often employ flow chemistry approaches with configurable fluidic circuits, valves, and pumps that directly connect synthesis, analysis, and purification modules [31].

Implementations like the Synbot (synthesis robot) platform exemplify this approach, featuring dedicated modules for pantry storage, dispensing, reaction, sample preparation, and analysis arranged in a fixed footprint of approximately 9.35m × 6.65m [31]. Transfer between modules occurs through robotic arms or conveyors within an enclosed system, minimizing human intervention but requiring dedicated infrastructure.

The AI architecture in fixed systems often employs a blackboard design where multiple specialized modules (retrosynthesis, experiment design, optimization) access a shared database [31]. This facilitates collaborative problem-solving, with the AI initially planning synthetic pathways and iteratively refining them using experimental feedback.

Table 1: Comparative Architecture Features

| Feature | Mobile Robot Systems | Fixed Automation Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Integration Method | Mobile sample transport between instruments | Hardwired fluidic/robotic connections |

| Laboratory Footprint | Distributed; utilizes existing equipment | Consolidated; dedicated footprint (e.g., 9.35m × 6.65m) [31] |

| Instrument Accessibility | Shared with human researchers | Typically dedicated to automation |

| Scalability | High; additional instruments easily incorporated | Limited by physical system constraints |

| Implementation Timeline | Weeks to months | Months to years |

| Typical Cost Range | $25,000-$200,000+ [12] | $150,000-$500,000+ [12] |

Experimental Performance and Capabilities

Synthesis and Workflow Execution

Mobile robotic systems demonstrate particular strength in exploratory chemistry applications where reaction outcomes are uncertain and require multiple characterization techniques. Documented implementations have successfully performed structural diversification chemistry, supramolecular host-guest chemistry, and photochemical synthesis [3]. In one case, mobile robots autonomously executed a divergent multi-step synthesis involving reactions with medicinal chemistry relevance, making decisions about which reactions to scale up based on orthogonal analytical data [3].

Fixed automation systems excel in optimization tasks where reaction targets are well-defined. The Synbot platform, for instance, has demonstrated the ability to not only execute synthetic procedures but also dynamically optimize molecular synthesis recipes through iterative experimentation [31]. Its AI-driven system can determine whether to continue with current reaction conditions, try alternative conditions, or abandon synthetic routes based on real-time analytical data.

Decision-Making and AI Integration

The effectiveness of closed-loop workflows fundamentally depends on AI decision-making capabilities that transform automated experiments into autonomous discovery systems.

Mobile robot workflows often employ heuristic decision-makers designed by domain experts to process complex, multimodal data. In documented implementations, these decision-makers provide binary pass/fail grading for each analysis type, which are combined to determine experimental progression [3]. This approach maintains openness to novel discoveries while ensuring chemically meaningful advancement.

Fixed systems frequently implement more sophisticated hybrid dynamic optimization models that combine message-passing neural networks with Bayesian optimization [31]. This architecture balances exploitation of existing knowledge with exploration of novel chemical spaces, particularly valuable for optimizing reaction yields where prior data exists but optimal conditions are unknown.

Diagram 1: Mobile robot systems use distributed instruments connected by physical sample transport, enabling flexible workflow redesign.

Diagram 2: Fixed automation systems tightly integrate dedicated modules through hardwired connections, optimizing for throughput over flexibility.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Mobile Robot Systems | Fixed Automation Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment Throughput | Moderate; limited by transportation time | High; optimized for continuous operation |

| Characterization Flexibility | High; multiple techniques (NMR, MS, etc.) [3] | Typically limited to integrated techniques |

| Reaction Success Identification | Based on orthogonal data fusion [3] | Based on predefined optimization targets |

| System Uptime | High; instrument sharing reduces dependency | Variable; single point failures affect entire system |

| Optimization Efficiency | Demonstrated for exploratory discovery [3] | Demonstrated for yield optimization [31] |

| Multistep Synthesis Capability | Verified for up to 2-3 steps [3] | Verified for complex multi-step optimizations [31] |

Implementation Considerations

Cost and Infrastructure Requirements

The financial investment required for these automation strategies varies significantly. Basic collaborative robot (cobot) systems start around $25,000, while full industrial automation systems can reach $500,000 or more [12]. Mobile robot implementations typically range from $40,000 to $150,000 including tooling and basic integration, while fixed automation systems often require $150,000 to $500,000 when accounting for comprehensive integration [12].

Beyond initial hardware costs, implementation expenses include system integration (potentially doubling robot costs), facility modifications ($10,000-$50,000), operator training ($500-$5,000), and ongoing maintenance contracts (10-15% of purchase price annually) [12]. Mobile robots generally require less infrastructure modification but may incur costs for navigation infrastructure and safety systems.

Flexibility and Adaptability

Mobile robots offer superior adaptability to existing laboratories, operating in shared human-robot environments without monopolizing equipment [3]. This allows researchers to continue using valuable instrumentation between robotic experiments. The modular nature of these systems also supports gradual expansion, with additional analytical techniques incorporated as needed.

Fixed automation provides higher throughput for well-defined workflows but suffers from limited reconfigurability. Once dedicated to specific processes, these systems are difficult and expensive to repurpose for new research directions. This makes them ideal for high-volume, repetitive tasks in established research domains but less suitable for exploratory work requiring frequent methodological changes.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The implementation of closed-loop workflows requires careful selection of reagents, materials, and instruments that enable automated handling and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Automated Workflows

| Item | Function in Automated Workflow | Compatibility Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alkyne Amines (e.g., 1-3) [3] | Building blocks for combinatorial synthesis | Stable for automated storage and dispensing |

| Isothiocyanates/Isocyanates (e.g., 4-5) [3] | Electrophiles for urea/thiourea formation | Compatible with automated liquid handling |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR spectroscopy for reaction monitoring | Required for automated structural validation |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Chromatographic separation and mass detection | Essential for automated analysis systems |

| Solid-Supported Reagents | Enable purification in flow systems | Critical for fixed automation workflows |

| Stable Catalyst Systems | Ensure reproducible reaction performance | Necessary for reliable automation |

| Standardized Reference Materials | System calibration and validation | Maintain analytical instrument performance |

The comparison between mobile robotic systems and fixed automation for closed-loop chemical research reveals complementary strengths. Mobile robots excel in exploratory research environments where flexibility, equipment sharing, and multimodal characterization are prioritized. Their ability to navigate existing laboratories makes them particularly valuable for academic settings and drug discovery stages where chemical space is broadly explored.

Fixed automation systems demonstrate superior performance for focused optimization tasks, where throughput, reproducibility, and dedicated operation justify the significant infrastructure investment. Their integrated nature minimizes transfer times and potential contamination, providing more robust operation for well-defined synthetic pathways.

Future developments in AI-driven decision-making [30] [32], autonomous mobile manipulators [33], and standardized interoperability protocols will likely blur the distinctions between these approaches, enabling hybrid systems that combine the flexibility of mobile platforms with the throughput of fixed automation. For research organizations, the optimal path forward may involve implementing mobile systems for exploratory stages followed by fixed automation for development and optimization phases, creating an integrated ecosystem that accelerates the entire discovery pipeline.

Maximizing Efficiency and Overcoming Implementation Challenges

The integration of robotics and automation is fundamentally changing the landscape of chemical and materials research, enabling unprecedented levels of throughput and data-driven experimentation [28]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a key strategic decision lies in choosing between the flexibility of mobile robots and the high-throughput specialization of fixed automation. This guide provides an objective framework for this critical selection, supported by current data and experimental insights.

Understanding the Core Technologies

The choice between mobile and fixed automation hinges on their inherent capabilities and the specific demands of your research workflows.