Microbiome Sequencing QC: Best Practices for Robust and Reproducible Results from Sample to Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control for microbiome sequencing, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Microbiome Sequencing QC: Best Practices for Robust and Reproducible Results from Sample to Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control for microbiome sequencing, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the entire workflow, from foundational concepts explaining how biases at every step—sample collection, DNA extraction, and sequencing—can skew results, to methodological best practices for implementing controls and data preprocessing. The guide further addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls, particularly in low-biomass samples, and outlines rigorous strategies for validating findings through benchmarking and standardization. By synthesizing current best practices, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate reliable, reproducible microbiome data crucial for robust biomedical and clinical research.

Why Microbiome QC Matters: Understanding Sources of Bias and Variation

The Critical Impact of Technical Bias on Biological Interpretation

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I identify and correct for DNA extraction bias?

Issue: Significant differences in microbial composition are observed between samples processed with different DNA extraction kits or lysis protocols, rather than due to true biological variation [1] [2].

Root Cause: DNA extraction bias stems from differential cell lysis efficiency and DNA recovery across bacterial taxa, primarily influenced by variations in cell wall structure (e.g., Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative) [1]. This is one of the most impactful confounders in microbiome sequencing studies [1].

Solution:

- Experimental: If possible, use the same extraction kit and protocol for all samples within a study. If comparing across studies or batches, note the kit lot numbers and include them as confounding variables in your statistical models [2].

- Computational (Emerging): Use mock community controls with known compositions to quantify taxon-specific extraction biases. A promising computational correction involves using bacterial cell morphology (e.g., cell shape and size) to predict and correct for this bias, as the bias per species has been shown to be predictable by bacterial cell morphology [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Assessing Extraction Bias with Mock Communities:

- Procure Mock Communities: Obtain whole-cell mock microbial community standards (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS series) with both even and staggered compositions, as well as their corresponding DNA mocks [1].

- Parallel Processing: Subject the whole-cell mock communities to the same DNA extraction protocols used for your environmental samples (e.g., testing different kits like QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini Kit and ZymoBIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit, and different lysis conditions) [1].

- Sequence: Sequence the extracted DNA (e.g., V1–V3 16S rRNA gene region) alongside the corresponding DNA mocks and your environmental samples [1].

- Quantify Bias: Compare the observed microbiome composition of the cell mocks to their expected composition (from the DNA mocks) to reveal taxon-specific, protocol-dependent extraction bias [1].

- Apply Correction: Use the measured bias from the mocks to computationally correct the data from environmental samples. The morphology-based correction model can be applied even to non-mock taxa [1].

How can I detect and remove contaminant sequences?

Issue: The presence of microbial sequences in samples that do not originate from the sample itself, but from laboratory reagents, kits, or cross-contamination during processing. This is particularly problematic for low-biomass samples [1] [2].

Root Cause: Contaminants often originate from extraction and PCR reagents, buffers, and kit components. Cross-contamination can also occur between samples, especially those with low input DNA [1].

Solution:

- Experimental: Always include negative controls (e.g., blank extraction tubes with only a swab or water) processed alongside your samples throughout the entire workflow [1] [2].

- Computational: Use tools like the

decontampackage in R, which supports both frequency-based and prevalence-based testing to identify contaminant sequences.

What should I do if my library yields are low or show high duplication rates?

Issue: Final sequencing library concentrations are unexpectedly low, or the sequencing run returns data with high duplication rates and poor coverage [4].

Root Cause & Solution:

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Failure | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (phenol, salts) or degraded DNA/RNA [4]. | Re-purify input sample; check purity via 260/230 and 260/280 ratios; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over absorbance (NanoDrop) [4]. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-shearing produces fragments outside the optimal size range for adapter ligation [4]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragment size distribution post-shearing [4]. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Suboptimal adapter-to-insert molar ratio, poor ligase activity, or improper reaction conditions [4]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; optimize incubation time and temperature [4]. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired library fragments are accidentally removed during bead-based purification or size selection [4]. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratio; avoid over-drying beads; use a "waste plate" to temporarily hold discards for recovery in case of error [4]. |

How do I manage batch effects and other study design biases?

Issue: Systematic technical differences between groups of samples processed in different batches, on different days, or by different personnel obscure true biological signals [5] [2].

Root Cause: Non-biological variations introduced during sample collection, storage, DNA extraction, library preparation, or sequencing runs [2].

Solution:

- Prevention: Randomize samples during extraction and sequencing. Use the same collection devices, storage conditions, and reagent kit lots for all samples where possible. Document all potential confounders (e.g., collector ID, extraction date) [2].

- Correction: Apply batch effect correction algorithms during data preprocessing.

- Common Tools:

ComBat(from the sva package),Limma,Harmony, andPLSDA-batchare commonly used to adjust for batch effects in microbiome data [5].

- Common Tools:

Experimental Protocol for Minimizing Batch Effects:

- Standardize Collection: Use consistent aseptic techniques and the same manufacturer's collection devices for all samples [2].

- Randomize: Randomize the order of sample processing (extraction, library prep) to ensure technical variation is not confounded with experimental groups [2].

- Control: Include positive controls (mock communities) and negative controls in every processing batch [1] [2].

- Metadata Tracking: Meticulously record all processing variables (kit lots, dates, personnel) for use as covariates in statistical models [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical steps to minimize bias in a microbiome study? A: The most critical steps are: (1) Consistent sample collection and immediate freezing at -80°C [2]; (2) Using the same DNA extraction kit and protocol across all samples [2]; (3) Including both positive (mock community) and negative controls in every batch [1]; and (4) Randomizing samples during laboratory processing [2].

Q2: My data has a lot of zeros. How should I handle this sparsity? A: The zeros in microbiome data can be either biological (true absence) or technical (below detection limit). Preprocessing steps include:

- Filtering: Remove low-abundance features that are likely noise [3] [5].

- Imputation: Carefully consider imputation methods (e.g.,

mbImpute, random forest) to estimate likely values for technical zeros, though these methods make specific assumptions and should be chosen with caution [5].

Q3: What is the best way to normalize microbiome sequencing data? A: There is no single "best" method, as the choice depends on your data and research question. Common methods include:

- Total Sum Scaling (TSS): Converts counts to relative abundances.

- CSS (Cumulative Sum Scaling): Implemented in

metagenomeSeq, is robust to outliers [5]. - ANCOM-BC: Accounts for the compositional nature of the data [5].

- Rarefaction: Downsamples all samples to the same sequencing depth, but discards data and can reduce sensitivity [5].

Q4: How does library preparation cause bias? A: Bias during library prep can arise from:

- Amplification Bias: During PCR, overcycling leads to duplicates and artifacts, while primer mismatches can under-amplify certain taxa [4].

- Adapter Contamination: Inefficient ligation or cleanup leads to adapter-dimer formation, which consumes sequencing throughput [4].

- Size Selection Bias: Overly aggressive cleanup can systematically remove fragments of certain sizes [4].

Key Data Preprocessing Steps and Methods

The following table summarizes the core steps in a robust microbiome data preprocessing workflow, which are essential for mitigating technical biases prior to biological interpretation [5].

| Preprocessing Step | Purpose | Common Methods & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control & Filtering | Remove low-quality sequences, contaminants, and low-abundance features. | FastQC, Trimmomatic, genefilter R package [5]. |

| Batch Effect Correction | Adjust for systematic technical differences between processing batches. | ComBat, Limma, Harmony [5]. |

| Imputation | Handle excess zeros (sparsity) by estimating values for missing data. | mbImpute, k-NN, random forest [5]. |

| Normalization | Account for differences in sequencing depth across samples to make them comparable. | Rarefaction, CSS (metagenomeSeq), ANCOM-BC, TSS [5]. |

| Data Transformation | Convert data to meet assumptions of downstream statistical tests (e.g., reduce skew). | Log-ratio transformations (e.g., Centered Log-Ratio) [5]. |

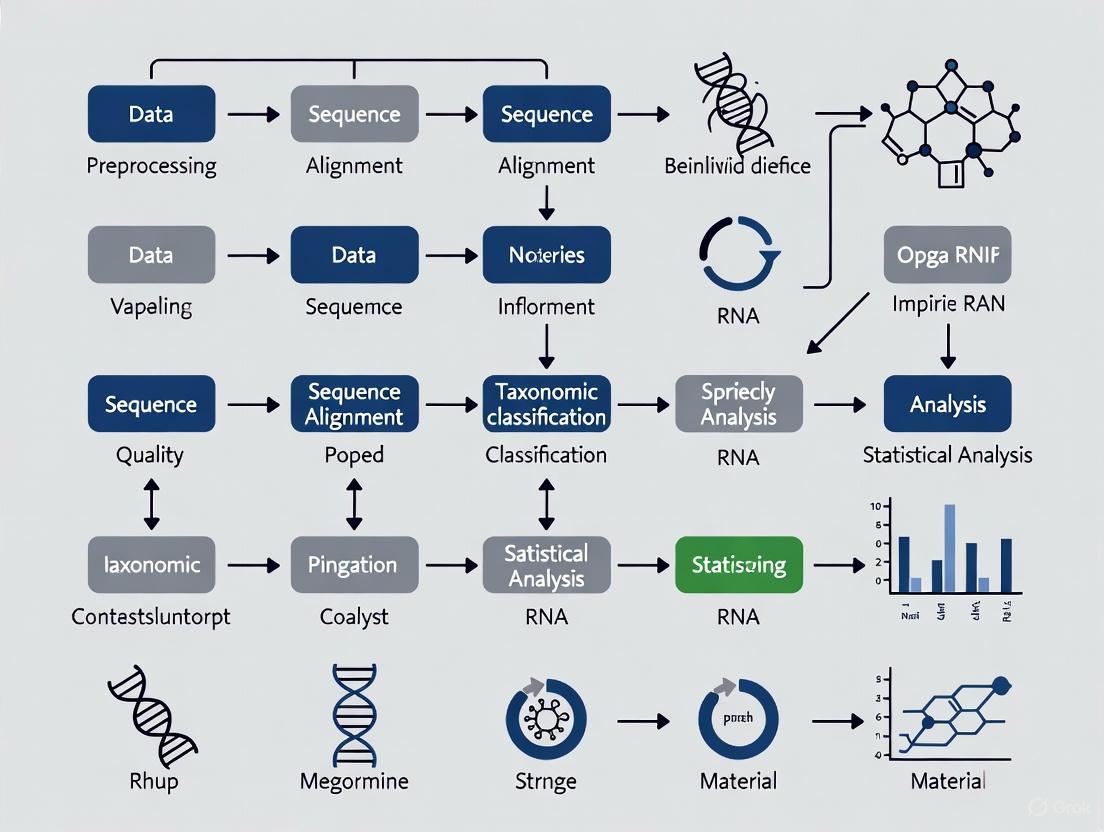

Workflow for Identifying and Correcting Technical Biases

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for identifying and mitigating key technical biases in microbiome research.

Experimental Protocol for Extraction Bias Investigation

This diagram details the experimental design for quantifying DNA extraction bias using mock communities, as described in the troubleshooting guides.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Communities (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS) | Positive controls with known composition to quantify technical bias and accuracy across the entire workflow [1]. |

| Different DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., QIAamp UCP, ZymoBIOMICS Microprep) | To compare and quantify protocol-dependent extraction biases [1]. |

| Standardized Collection Swabs/Tubes | To ensure consistency during sample collection and minimize device-introduced contamination [2]. |

| Negative Control Buffers (e.g., Buffer AVE) | Processed alongside samples to identify contaminants originating from reagents and the laboratory environment [1]. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Kits (e.g., Qubit assays) | For accurate DNA/RNA quantification, as absorbance methods (NanoDrop) can overestimate concentration due to contaminants [4]. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits (e.g., AMPure XP) | For post-amplification purification and size selection to remove adapter dimers and other unwanted fragments [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical host-related confounders in microbiome studies? Transit time (often measured via stool moisture content), body mass index (BMI), and intestinal inflammation (measured by fecal calprotectin) are among the most critical host-related confounders. These factors can explain more variation in the microbiome than the actual disease states under investigation. For example, in colorectal cancer studies, these covariates can supersede the variance explained by diagnostic groups, and controlling for them can nullify the apparent significance of some disease-associated species [6].

2. Why is absolute microbial load important, and how can I account for it? Microbial load (the absolute number of microbial cells per gram of sample) is a major determinant of gut microbiome variation and a significant confounder for disease associations. Relying solely on relative abundance data from standard sequencing can be misleading, as an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon could be due to a true increase or a decrease in other taxa [7]. You can account for this by:

- Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP): Using techniques like 16S rRNA gene qPCR or flow cytometry to measure absolute abundances alongside sequencing [6].

- Machine Learning Prediction: Employing published models that can predict microbial load from standard relative abundance data, allowing for statistical adjustment in your analyses [7].

3. How do host genetics influence the gut microbiome? Host genetics can actively shape the microbiome by creating an environment that selects for specific microbial genes. A key example is the association between the human ABO blood group gene and structural variations in the bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Individuals with blood type A, who secrete the A antigen (GalNAc), have a higher prevalence of F. prausnitzii strains that carry a gene cluster for utilizing GalNAc as a food source [8]. This demonstrates a direct, functional interaction between the host genotype and the microbial metagenome.

4. What are the best practices for sample collection and storage to minimize confounding? Proper sample collection and handling are crucial for reproducibility. Key recommendations include [9] [10]:

- Shipping: Keep samples frozen at -80°C and ship on dry ice. The only exception is when using a manufacturer's collection device with a stabilizing buffer, which allows for short-term room temperature stability.

- Storage: Samples can be stored at -80°C indefinitely, but long-term storage is best with homogenized and aliquoted extracts. For samples in stabilizing buffer, follow the manufacturer's guidelines for room-temperature stability before moving to -80°C.

- Low-Biomass Samples: Submit a larger sample mass to account for troubleshooting and ensure sufficient material for analysis.

5. How can I control for batch effects in my microbiome experiment? Batch effects, introduced during sample processing and sequencing, can be a major technical confounder. The most effective strategy is to wait until all samples for a study have been collected and process them simultaneously in a randomized order [9]. If collection occurs over an extended period, process samples by time point as complete batches. Using master mixes for reagents and including control samples across batches can also help identify and correct for these effects.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Interpreting Disease-Associations Amidst Host and Environmental Confounders

Problem: A case-control study identifies several microbial taxa as significantly associated with a disease. However, it is unclear if these associations are driven by the disease itself or by underlying host and environmental factors.

Investigation and Solution: Follow a systematic process to identify and statistically control for major confounders. The flowchart below outlines this diagnostic strategy.

Case Example: Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Microbiome Signatures A 2024 study in Nature Medicine re-evaluated microbiome signatures in CRC by implementing rigorous confounder control and quantitative profiling [6].

- Observation: Well-established CRC-associated bacteria like Fusobacterium nucleatum appeared significantly enriched in patient groups.

- Action: Researchers controlled for fecal calprotectin (inflammation), transit time, and BMI using QMP.

- Result: The significance of F. nucleatum and several other taxa was substantially reduced or lost after adjustment. In contrast, the associations for Parvimonas micra and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius remained robust, highlighting them as more reliable targets.

Issue 2: Managing Technical Variability from Sample to Sequence

Problem: Uncontrolled technical variation during the wet-lab workflow introduces noise and batch effects, obscuring biological signals and leading to spurious results.

Investigation and Solution: A standardized, controlled workflow is essential from the moment of sample collection. The following diagram maps the critical control points in a typical microbiome sequencing workflow.

Case Example: Sequencing Preparation Failures A core facility experienced sporadic library preparation failures that correlated with different technicians [4].

- Symptoms: Inconsistent library yields, high adapter-dimer peaks, and occasional complete failures.

- Root Cause: Subtle protocol deviations between operators, such as mixing methods (vortexing vs. pipetting), timing differences, and occasional pipetting errors (e.g., discarding beads instead of supernatant).

- Solution:

- Introduced highlighted, step-by-step SOPs with critical steps in bold.

- Implemented the use of "waste plates" to allow error recovery.

- Switched to master mixes to reduce pipetting steps and variability.

- Enforced technician checklists and cross-checking.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for controlling confounders in microbiome research.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| MO BIO Powersoil DNA Kit | A widely used and validated kit for efficient microbial lysis (including with bead-beating) and removal of common environmental inhibitors (humic acids, phenols) that can affect downstream steps [9]. |

| Stool Stabilization Buffers (e.g., from DNA Genotek, Norgen Biotek) | Allows room-temperature sample storage and transport by preserving microbial community composition and nucleic acids, crucial for multi-center studies and home-based collection [9]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Assays | Provides absolute quantification of total bacterial load or specific taxa, enabling the shift from relative to absolute abundance data (QMP) and identifying low-biomass samples prone to contamination [6] [9]. |

| Fecal Calprotectin Test | A clinically validated immunoassay to measure neutrophil-derived calprotectin in stool, providing an objective metric of intestinal inflammation, a major covariate in gastrointestinal disease studies [6]. |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Standards (e.g., from NIST) | Certified reference materials containing known microbial communities at defined ratios, used to benchmark laboratory protocols, assess batch effects, and validate bioinformatic pipelines [11]. |

The table below synthesizes the primary classes of confounders and recommended actions to mitigate their impact.

| Confounder Class | Specific Examples | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Host Physiology | Transit time, fecal microbial load, calprotectin (inflammation), BMI, age [7] [6]. | - Record comprehensive metadata.- Use QMP to measure absolute abundances.- Employ statistical adjustment (covariates) in models. |

| Host Genetics | ABO blood group, FUT2 secretor status [8]. | - Collect host genetic information where possible.- Consider genotype as a factor in stratified analyses. |

| Laboratory Methods | DNA extraction kit/protocol, batch effects during library prep, sequencing run, bioinformatic pipelines [12] [10]. | - Standardize protocols across all samples.- Process cases and controls simultaneously in randomized batches.- Include positive controls and standard reference materials. |

| Sample Collection | Storage conditions, shipping method, collection device, time of day [9] [10]. | - Use standardized collection kits with stabilizers.- Ship on dry ice for frozen samples.- Document all collection variables meticulously. |

Within quality control frameworks for microbiome research, the choice between 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a critical initial decision point that fundamentally shapes all subsequent data generation and interpretation. These two predominant methodologies offer distinct approaches to profiling microbial communities, each with characteristic strengths, limitations, and quality control considerations [13]. The selection process must be guided by specific research questions, sample types, and analytical resources, as this decision directly influences the taxonomic resolution, functional insights, and potential biases introduced during experimental workflows [14]. This technical guide provides a structured comparison and troubleshooting resource to help researchers navigate this complex methodological landscape while maintaining rigorous quality standards essential for robust microbiome science.

Technical Comparison: Core Methodological Differences

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

16S rRNA Sequencing is a targeted amplicon sequencing approach that amplifies and sequences specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) of the bacterial and archaeal 16S ribosomal RNA gene [13] [15]. This method leverages the fact that the 16S gene contains both highly conserved regions (for primer binding) and variable regions (for taxonomic differentiation) [16]. The process involves DNA extraction, PCR amplification of targeted regions, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis using pipelines such as QIIME or MOTHUR [13] [15].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing takes an untargeted approach by fragmenting all DNA in a sample into small pieces that are sequenced randomly [17]. These sequences are then computationally reconstructed to identify microbial taxa and genes [13]. This method sequences all genomic DNA regardless of origin, enabling identification of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms simultaneously while also providing information about functional gene content [13] [14]. Bioinformatics pipelines for shotgun data are more complex and may include tools like MetaPhlAn, HUMAnN, or MEGAHIT [13] [17].

The workflow diagram below illustrates the key procedural differences between these two approaches:

Comprehensive Method Comparison Table

The following table provides a detailed quantitative and qualitative comparison of key parameters between 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics:

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD [13] | Starting at ~$150 USD (varies with depth) [13] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (sometimes species) [13] [14] | Species and strain-level [13] [14] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [13] | All taxa: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Viruses, Protists [13] [14] |

| Functional Profiling | No direct assessment (only predicted) [13] [14] | Yes, direct identification of functional genes and pathways [13] [17] |

| Host DNA Interference | Low (PCR targets specific gene) [14] | High (requires mitigation strategies) [13] [14] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to intermediate [13] | Intermediate to advanced [13] |

| Minimum DNA Input | Low (<1 ng) due to PCR amplification [14] | Higher (typically ≥1 ng/μL) [14] |

| Recommended Sample Types | All types, especially low microbial biomass samples [14] | All types, best with high microbial biomass (e.g., stool) [13] [14] |

| PCR Amplification Bias | Present (medium to high bias) [13] | Lower bias (no targeted amplification) [13] |

| Reference Databases | Well-established (SILVA, Greengenes) [13] [18] | Still growing and improving (GTDB, UHGG) [13] [18] |

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The following decision tree provides a structured approach for selecting the appropriate methodology based on specific research requirements:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: How do we address the problem of high host DNA contamination in shotgun metagenomic studies, particularly with low-biomass samples like skin swabs or tissue biopsies?

- Challenge: Shotgun sequencing can be significantly compromised when host DNA comprises most of the sequenced material, reducing microbial signal and requiring deeper sequencing to achieve sufficient coverage [13] [14].

- Solutions:

- Experimental: Implement host DNA depletion methods using commercial kits that selectively digest mammalian DNA or enrich microbial DNA through differential centrifugation or filtration [17].

- Bioinformatic: Apply computational filtering to remove host-derived reads post-sequencing by aligning to host reference genomes (e.g., GRCh38 for human) [17] [18].

- Design Consideration: For samples with expected high host DNA, 16S rRNA sequencing may be preferable as PCR amplification specifically targets microbial sequences, effectively ignoring host DNA [14].

Q2: What strategies can mitigate PCR amplification biases in 16S rRNA sequencing that may distort true taxonomic abundances?

- Challenge: The PCR step in 16S library preparation can introduce quantitative biases due to primer mismatches, variable gene copy numbers, and amplification efficiency differences [18] [19].

- Solutions:

- Primer Selection: Use well-validated, degenerate primers that cover a broad range of taxa and target appropriate hypervariable regions (e.g., V4 for general bacterial diversity) [15].

- PCR Optimization: Standardize template concentration, cycle number, and polymerase choice across all samples to minimize technical variation [15].

- Controls: Include positive controls (mock communities with known composition) and negative controls (no-template) to identify and correct for amplification biases [15].

Q3: How can researchers achieve sufficient statistical power when shotgun metagenomic sequencing costs limit sample size?

- Challenge: While shotgun sequencing provides richer data, the higher cost per sample may limit the number of biological replicates, reducing statistical power for detecting associations [13].

- Solutions:

- Shallow Shotgun Sequencing: Implement "shallow" sequencing at lower coverage (0.5-2 million reads/sample), which provides >97% of compositional data at a cost similar to 16S sequencing [13] [14].

- Two-Tiered Approach: Conduct 16S rRNA sequencing on all samples for primary analysis, with shotgun metagenomics on a subset of selected samples for deeper functional insights [13].

- Pooling Strategies: For initial screening studies, consider pooling samples by experimental group before sequencing to reduce costs while maintaining group-level comparisons.

Q4: What approaches help reconcile taxonomic discrepancies between 16S and shotgun metagenomic results from the same samples?

- Challenge: Studies comparing both methods on identical samples show that 16S detects only part of the microbial community revealed by shotgun sequencing, with particular under-detection of low-abundance taxa [20] [18].

- Solutions:

- Database Alignment: Use consistent, comprehensive reference databases when possible and recognize that 16S databases (SILVA, Greengenes) differ from shotgun databases (GTDB) in content and curation [18].

- Abundance Thresholding: Account for the higher detection sensitivity of shotgun sequencing, which can identify 152 significantly different genera that 16S misses in comparative studies [20].

- Method-Specific Validation: When integrating data from both methods, validate key findings using complementary techniques (qPCR, culture) to confirm biological significance [20].

Technical FAQ for Experimental Design

Q: When is 16S rRNA sequencing clearly preferred over shotgun metagenomics? A: 16S is preferable when: (1) studying only bacterial/archaeal composition; (2) working with low-biomass samples with high host DNA (skin, tissue); (3) budget constraints require larger sample sizes; (4) bioinformatics capabilities are limited; or (5) conducting initial exploratory studies on undercharacterized environments [13] [14] [15].

Q: What are the key advantages of shotgun metagenomics that justify its higher cost and complexity? A: Shotgun metagenomics provides: (1) species- and strain-level taxonomic resolution; (2) direct assessment of functional potential through gene content; (3) multi-kingdom profiling (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea); (4) discovery of novel genes and pathways; and (5) assembly of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from unculturable organisms [13] [17] [21].

Q: How does sequencing depth requirements differ between these methods? A: 16S rRNA sequencing typically requires 20,000-100,000 reads per sample to capture most diversity, while shotgun metagenomics needs 5-50 million reads per sample depending on community complexity and the desired analysis (compositional vs. functional vs. genome assembly) [20] [21]. Shallow shotgun approaches use 0.5-2 million reads per sample [13].

Q: Can functional profiles be accurately predicted from 16S rRNA sequencing data? A: Tools like PICRUSt predict functional potential from 16S data by extrapolating from reference genomes, but these predictions are indirect inferences with limitations. Shotgun metagenomics directly sequences functional genes, providing more accurate and comprehensive functional profiling, though database limitations still exist [13] [19].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed 16S rRNA Sequencing Methodology

Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Collect samples using sterile techniques to avoid external contamination [15].

- Immediately freeze at -20°C or -80°C, or place in preservation buffers if freezing is delayed [15].

- For low-biomass samples, consider specialized collection swabs with DNA stabilization properties.

DNA Extraction:

- Use mechanical lysis (bead beating) combined with chemical lysis for comprehensive cell wall disruption across diverse taxa [15].

- Employ commercial kits validated for microbiome studies (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil kit) to ensure reproducible recovery of diverse community members [17] [15].

- Include extraction controls to monitor potential contamination.

Library Preparation:

- Amplify target hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4 for general bacterial diversity) using validated primer sets [16] [15].

- Optimize PCR cycle numbers to minimize amplification artifacts while maintaining sufficient product [15].

- Incorporate dual-index barcodes for multiplexing to enable sample pooling and prevent index hopping [15].

- Clean amplified products using size-selection methods (magnetic beads) to remove primers and primer dimers [15].

Sequencing:

- Utilize Illumina platforms (MiSeq, NovaSeq) for high-output sequencing with low error rates [16].

- Target 20,000-100,000 reads per sample depending on community complexity [20].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw data through established pipelines (QIIME2, mothur) [13] [15].

- Perform quality filtering, denoising, chimera removal, and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) calling [18].

- Classify taxa using reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes) [16] [18].

- Conduct diversity analyses (alpha, beta diversity) and differential abundance testing [15].

Detailed Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Methodology

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA using methods that minimize shearing [17].

- For samples with high host DNA, implement depletion strategies (selective lysis, centrifugation, commercial kits) [17].

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (Qubit) and assess quality via fragment analyzers or gel electrophoresis [17].

Library Preparation:

- Fragment DNA to 250-300 bp fragments via acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation [17].

- Perform tagmentation (simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging) for efficient library construction [13].

- Use PCR-free library prep when possible to reduce amplification biases, or minimize PCR cycles [13].

Sequencing:

- Sequence on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq) for high coverage, or Oxford Nanopore/PacBio for long reads enabling better assembly [17] [22].

- Target 5-50 million reads per sample depending on analysis goals [21].

- For complex samples like soil, deeper sequencing (>100 million reads) may be necessary for adequate coverage [22].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control: Remove adapters, low-quality reads, and host-derived sequences [17] [19].

- Taxonomic profiling: Use tools like MetaPhlAn or Kraken2 with curated databases (GTDB) [13] [18].

- Functional analysis: Annotate genes via HUMAnN2 against pathway databases (KEGG, MetaCyc) [13] [19].

- Assembly and binning: For MAG recovery, assemble reads into contigs and bin into genomes using tools like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes [17] [22].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and materials essential for implementing robust microbiome sequencing workflows:

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | DNA Extraction | Comprehensive lysis and purification of microbial DNA from challenging samples | Bead beating efficiency; inhibitor removal; reproducible across sample types [17] |

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit | DNA Extraction | Effective DNA extraction from soil and stool samples | Consistent yield across diverse microbial communities; minimal bias [18] |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | 16S Library Prep | Amplification of specific hypervariable regions | Coverage breadth; degeneracy; minimal taxonomic bias [16] [15] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit | Shotgun Library Prep | Tagmentation-based library preparation for metagenomes | Efficient fragmentation; minimal GC bias; high complexity libraries [13] |

| SPRIselect Beads | Library Clean-up | Size selection and purification of DNA fragments | Reproducible size selection; minimal DNA loss; effective adapter dimer removal [13] |

| PhiX Control Library | Sequencing | Quality control and calibration during sequencing | Provides internal standard for cluster generation and error rate monitoring |

| Mock Community Standards | QC | Validation of entire workflow from extraction to analysis | Well-characterized composition; even abundance; identifies technical biases [15] |

| SILVA Database | 16S Analysis | Taxonomic classification of 16S sequences | Comprehensive curation; regular updates; accurate taxonomic assignments [18] |

| GTDB (Genome Taxonomy Database) | Shotgun Analysis | Taxonomic classification of metagenomic reads | Genome-based taxonomy; standardized classification; regular expansions [18] |

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Methods

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

Beyond standalone 16S or shotgun metagenomic approaches, advanced study designs increasingly integrate multiple omics technologies:

- Metatranscriptomics: Sequences total RNA to profile actively expressed genes and pathways, complementing the functional potential revealed by shotgun metagenomics [16] [21].

- Metaproteomics: Identifies and quantifies expressed proteins, providing direct evidence of functional activity beyond genetic potential.

- Metabolomics: Characterizes small molecules and metabolic products, connecting microbial community functions to host phenotypes or ecosystem processes.

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

Emerging long-read sequencing platforms (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) enable:

- Improved genome assembly from complex communities through longer contiguous sequences [22].

- Direct sequencing of epigenetic modifications without special library prep.

- Real-time analysis and more accurate resolution of repetitive regions.

- Recovery of complete ribosomal operons and more reliable taxonomic classification [22].

Standardization and Quality Control Frameworks

As microbiome research matures, field-wide standardization efforts include:

- Implementation of standardized positive and negative controls throughout workflows [15].

- Adoption of reference materials (mock communities) for cross-study comparisons.

- Development of quality metrics specific to microbiome data (sequencing depth, negative control subtraction, etc.).

- Repository submission standards for metadata and raw data to enhance reproducibility.

The Unique Challenges of Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What makes low-biomass microbiome studies uniquely challenging? Low-biomass samples contain minimal microbial DNA, meaning the target DNA "signal" can be easily overwhelmed by contaminant "noise" from various sources. This occurs because standard DNA-based sequencing approaches operate near their limits of detection in these environments. Even small amounts of contaminating DNA can disproportionately influence results and lead to incorrect conclusions, making specialized contamination control practices essential [23].

2. What are the most common sources of contamination? Contamination can be introduced at virtually every stage of research, from sample collection to data analysis. Key sources include human operators (skin, hair, breath), sampling equipment, laboratory reagents and kits, and the laboratory environment itself. A particularly persistent problem is cross-contamination between samples, such as through well-to-well leakage during PCR [23].

3. How can I determine if my dataset is affected by contamination? The most reliable method is to process multiple types of controls in parallel with your actual samples. These include negative controls (e.g., blank swabs, sterile water) to identify contaminants from reagents and the lab environment, and positive controls (mock communities with known compositions) to assess biases in your entire workflow, from DNA extraction to sequencing. Sequencing data from negative controls should be used to identify and filter out contaminant sequences found in your true samples [23] [24].

4. Are findings from high-biomass studies (like stool) applicable to low-biomass research? Not directly. Practices suitable for high-biomass samples (e.g., human stool) can produce misleading results when applied to low-biomass samples. The proportional impact of contamination is far greater in low-biomass systems, necessitating more stringent contamination controls, specialized DNA extraction protocols, and specific data analysis techniques that account for the high noise-to-signal ratio [23].

5. My sequencing library yield is low. What should I check? Low library yield is a common issue. The following table outlines primary causes and corrective actions.

Table: Troubleshooting Low Library Yield

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality/Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition from residual salts, phenol, or polysaccharides [4]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8); use fresh wash buffers [4]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Over- or under-estimating input concentration leads to suboptimal reactions [4]. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV spectrophotometry; calibrate pipettes [4]. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Poor ligase performance or wrong adapter-to-insert ratio reduces yield [4]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions [4]. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired DNA fragments are accidentally removed during purification or size selection [4]. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads during clean-up steps [4]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Results Between Sample Batches

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Negative Controls. Without multiple negative controls, it's impossible to distinguish batch-specific contaminants from true biological signal.

- Solution: Include several types of negative controls (e.g., extraction blanks, no-template PCR controls) in every batch of samples processed. These controls must be carried through the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to sequencing [23].

- Cause: Batch Effects from Reagents or Operators.

- Solution: Where possible, process samples from different experimental groups simultaneously rather than in separate batches. If batch processing is unavoidable, use statistical batch effect correction methods (e.g., ComBat, Remove Unwanted Variation (RUV)) during data analysis [25].

- Cause: Variation in DNA Extraction Efficiency.

- Solution: Implement a standardized, robust lysis protocol that includes mechanical disruption (e.g., bead beating) to ensure even breakdown of tough microbial cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria). Use a defined mock community as a positive control to monitor extraction efficiency and bias across batches [24].

Problem: High Percentage of Unexpected or Foreign Taxa in Sequencing Results

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Contamination from Sample Collection.

- Solution: Decontaminate all sampling equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., bleach, UV-C light). Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels and personal protective equipment (PPE) like gloves, masks, and coveralls to limit human-derived contamination [23].

- Cause: Cross-Contamination Between Samples.

- Solution: Include environmental controls during sampling (e.g., swabs of the air, PPE, or sampling surfaces). In the lab, physically separate pre- and post-PCR workflows, use dedicated equipment, and consider using uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UDG) treatment to eliminate PCR carryover contamination [23].

- Cause: Contaminated Reagents.

Essential Quality Control Workflows

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for preventing and identifying contamination in low-biomass studies, integrating key steps from sample collection to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Controls for Low-Biomass Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Stabilizing Solution | Preserves nucleic acids immediately upon collection, "freezing" the microbial community profile and preventing overgrowth of opportunistic microbes during transport [24]. | Crucial for maintaining sample integrity from the point of collection, especially for remote sampling. |

| Mock Community Standards (Whole-Cell) | A defined mixture of intact microorganisms. Processed alongside samples to evaluate bias from DNA extraction (lysis efficiency) and the entire wet-lab workflow [24]. | Any deviation from the expected profile indicates a technical bias (e.g., under-representation of Gram-positive bacteria suggests lysis bias). |

| Mock Community Standards (Cell-Free DNA) | Purified genomic DNA from a defined community. Used after the DNA extraction step to evaluate bias from library preparation, PCR amplification, and sequencing [24]. | Helps pinpoint whether bias originates upstream (extraction) or downstream (PCR, sequencing) of the workflow. |

| Certified DNA-Free Water | Used for preparing reagents and as a negative control. Reduces background contamination from a common source [23] [24]. | Test different lots to find one with the lowest background signal. |

| Inhibitor Removal Kits | Removes substances (e.g., humic acids, bile salts) that co-extract with DNA and can inhibit downstream PCR or sequencing enzymes, which can skew community profiles [24]. | Essential for complex sample types like soil and stool. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Creates a barrier between the sample and contamination sources like human skin, hair, and aerosol droplets [23]. | Should include gloves, masks, goggles, and coveralls, similar to protocols used in cleanrooms and ancient DNA labs. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Sample Size and Power Analysis

Q: How do I determine the correct sample size for my microbiome study? A: Determining sample size requires a power analysis, which balances the number of biological replicates with the expected effect size and natural variability of your system. Sample size is more critical for statistical power than sequencing depth [26].

Power Analysis Components: A proper power analysis has five key components, outlined in the table below [26].

Sample Size Estimation Table: The following table summarizes sample size requirements for case-control studies based on a 2025 study using shallow shotgun metagenome sequencing, demonstrating how requirements change based on the feature being studied and the study design [27].

Feature Type Significance Level Cases Needed (1:1 matched) Cases Needed (1:3 matched) Low-prevalence species 0.05 15,102 10,068 High-prevalence species 0.05 3,527 2,351 Alpha/Beta diversity 0.05 1,000-5,000 Not Specified Species, Genes, Pathways 0.001 1,000-5,000 Not Specified Note: Calculations assume 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.5 per standard deviation, based on a single fecal specimen. Collecting multiple specimens per participant can significantly reduce the required number of cases [27].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Inability to detect statistically significant associations.

- Diagnosis: Low statistical power due to insufficient biological replicates.

- Solution:

- Conduct a power analysis before starting your experiment. Use pilot data or values from comparable published studies to estimate effect size and variance [26].

- For longitudinal studies, collect multiple samples per participant over time. This can substantially reduce the number of unique subjects needed [27].

- Consider increasing your case-to-control ratio where feasible [27].

Contamination and Control Strategies

Q: What controls are essential for microbiome studies, especially with low-biomass samples? A: Comprehensive controls are non-negotiable for distinguishing true microbial signal from contamination. This is particularly critical for low-biomass samples (e.g., skin, placenta, blood) where contaminant DNA can dominate [23].

Essential Control Types Table:

Control Type Purpose When to Use Reagent/Negative Control (Blank) Identifies contaminating DNA from kits, reagents, and lab environment [23] [28]. Essential for all studies, mandatory for low-biomass samples. Mock Community A known mix of microbial strains/DNA to assess bias in DNA extraction, PCR, and bioinformatics [28]. Recommended for all studies to validate the entire wet-lab and analysis pipeline. Sampling Control Captures contaminants from the sampling environment (e.g., air, gloves, collection equipment) [23]. Crucial for field studies or clinical sampling environments. Experimental Protocol for Low-Biomass Samples [23]:

- Decontaminate: Use single-use, DNA-free collection tools. Decontaminate reusable equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., bleach).

- Use PPE: Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits to minimize contamination from human operators.

- Include Controls: Process negative controls (e.g., empty collection tubes, swabs of sterile surfaces) alongside your samples at every stage, from collection through DNA extraction and sequencing.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: High levels of contaminant taxa (e.g., Delftia, Pseudomonas) in samples and negative controls.

- Diagnosis: Contamination from reagents or the laboratory environment.

- Solution:

Longitudinal Study Design

Q: What are the key considerations for designing a longitudinal microbiome study? A: Longitudinal studies track changes within individuals over time, offering unique insights into microbial dynamics, stability, and causality. Key challenges include missing data, temporal dependencies, and high variability [29].

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for designing and analyzing longitudinal microbiome studies, integrating modern computational solutions to common pitfalls.

- Key Methodologies:

- Missing Data Imputation: Frameworks like SysLM-I use Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks to infer missing values by capturing temporal causality and long-term dependencies [29].

- Causal Inference and Biomarker Discovery: Models like SysLM-C integrate deep learning with causal inference to identify various biomarker types, including dynamic, network, and disease-specific biomarkers, moving beyond correlation to suggest causation [29].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: High rates of missing data points due to irregular sampling or sample loss.

- Diagnosis: Inadequate planning for participant retention or sample collection logistics.

- Solution:

- Over-sample at the beginning of the study to account for expected drop-offs.

- Implement user-friendly sample collection kits to improve participant compliance.

- Use advanced computational imputation methods (e.g., SysLM-I, BRITS) designed for longitudinal data to handle missing values without introducing bias [29].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Q: What are common causes of sequencing library preparation failure, and how can I prevent them? A: Failures often stem from issues with sample input quality, fragmentation, amplification, or purification. The table below outlines common problems and their root causes [4].

Sequencing Preparation Troubleshooting Table:

Problem Category Typical Failure Signals Common Root Causes Sample Input/Quality Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low library complexity [4]. Degraded DNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [4]. Fragmentation/Ligation Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks [4]. Over- or under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio [4]. Amplification/PCR Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias [4]. Too many PCR cycles; inefficient polymerase; primer exhaustion [4]. Purification/Cleanup Incomplete removal of adapter dimers; high sample loss; salt carryover [4]. Wrong bead-to-sample ratio; over-dried beads; inefficient washing [4].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: High percentage of adapter dimers in final library.

- Diagnosis: Inefficient ligation or overly aggressive purification leading to loss of target fragments.

- Solution:

- Titrate adapter concentrations to find the optimal molar ratio for your sample type.

- Optimize bead-based cleanup parameters (e.g., bead-to-sample ratio) to better select for your target fragment size [4].

- Validate library quality using an instrument like a BioAnalyzer or TapeStation before sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solution | Removes contaminating DNA from surfaces and equipment. Critical for low-biomass research [23]. | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C light, or commercial DNA removal solutions. Note: autoclaving removes viable cells but not cell-free DNA [23]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Protects samples from contaminants shed by the researcher (skin, hair, aerosol droplets) [23]. | Gloves, masks, and cleansuits. For ultra-sensitive work, use multi-layer gloves and face masks/visors [23]. |

| Biological Mock Communities | Defined mixtures of microorganisms used to evaluate technical bias and accuracy throughout the workflow [28]. | Should reflect the diversity of the sample type. Composition and results must be made publicly available [28]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Sequences added to samples during library prep to allow multiplexing [28]. | Using unique dual indexes (not single indexes) significantly reduces the risk of index hopping and sample misassignment during demultiplexing [28]. |

| Bead-Beating Tubes | Used during DNA extraction to mechanically lyse tough microbial cell walls [28]. | Essential for accurate representation of communities from feces or soil. Protocols without bead-beating can dramatically underestimate diversity [28]. |

Implementing a Rigorous QC Workflow: From Wet Lab to Data

Best Practices for Sample Collection, Stabilization, and Storage

Sample Collection & Contamination Prevention

What are the critical steps for collecting a microbiome sample to avoid contamination?

Contamination prevention begins at the moment of collection and is especially critical for low-biomass samples (e.g., urine, tissue) where microbial signals can be easily overwhelmed. Key practices include:

- Use Sterile Materials: Always use single-use, sterile collection devices such as swabs, containers, and tubes [30] [24].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and other appropriate PPE to prevent the introduction of contaminants from the researcher [30] [31].

- Control the Environment: Perform collection in a decontaminated environment to minimize ambient contamination [30].

- Include Negative Controls: Always process a blank control (e.g., an empty swab or tube opened and closed during collection) alongside your samples. This helps identify any background contamination from reagents, kits, or the environment [24].

- Use Standardized Nomenclature: Adopt clear and consistent terminology for sample types. For instance, distinguish between "urinary bladder" samples (collected via catheter) and "urogenital" samples (voided) to ensure accurate interpretation of results [30].

Sample Stabilization & Preservation

How should I stabilize samples if immediate freezing is not possible?

Immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard, but it is often not feasible in field studies or home collection settings. The choice of preservation method significantly impacts the integrity of the microbial community profile [30] [32].

Table: Comparison of Sample Stabilization Methods

| Method | Protocol / Solution | Key Findings & Performance | Typical Storage Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigeration | Store sample at 4°C [32]. | Maintains microbial diversity and composition with no significant alteration compared to -80°C for up to 72 hours [32]. | Short-term (< 72 hours) |

| Chemical Preservatives | Submerge sample in OMNIgene·GUT or AssayAssure [30] [32]. | OMNIgene·GUT shows the least alteration in community profile after 72 hours at room temperature vs. -80°C freezing [32]. AssayAssure significantly helps maintain composition at room temperature [30]. | Medium-term (up to 2 weeks at room temp for some reagents [33]) |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Submerge sample in stabilization reagent [24] [34]. | Inactivates nucleases and preserves nucleic acids on contact, "freezing" the microbial profile at ambient temperature [24]. | Long-term at room temperature after immersion [24] |

| RNAlater | Submerge sample in RNAlater solution [32]. | Associated with significant divergence in microbial composition and lower community evenness compared to -80°C freezing [32]. | Varies |

| Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer | Suspend sample in TE buffer [32]. | Results in the greatest change in microbial composition, including a significant increase in Proteobacteria [32]. | Not recommended |

The following workflow outlines the key decision points for stabilizing different sample types:

Sample Stabilization Decision Workflow

Detailed Protocols:

- For Tissues, Cells, and Swabs: Submerge the sample completely in a DNA/RNA stabilization solution (e.g., Monarch DNA/RNA Protection Reagent, DNA/RNA Shield). For larger tissue pieces (>20 mg), homogenize in the solution prior to storage to ensure penetration [34].

- For Liquid Samples (e.g., Blood): Mix the sample with an equal volume of a 2X concentrated DNA/RNA protection reagent [34].

- For Fecal Samples: If refrigeration is unavailable, use a preservative like OMNIgene·GUT, which has been shown to perform better than RNAlater or TE buffer at room temperature [32].

Sample Storage Conditions

What are the optimal storage temperatures and durations?

Even after initial stabilization, long-term storage conditions are critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity.

Table: Optimal Storage Conditions for Preserved Samples

| Storage Temperature | Maximum Recommended Duration | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| -80°C | Long-term (>30 days) | Considered the gold standard for preserving microbial community composition. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles, which can degrade DNA and selectively harm certain taxa [30] [24] [32]. |

| -20°C | Long-term (>30 days) | Suitable for long-term storage of samples in stabilization solutions [34]. |

| 4°C (Refrigeration) | Medium-term (1-4 weeks) | An excellent short-term (e.g., 72 hours) alternative to freezing for fecal samples, showing no significant alteration in microbiota [34] [32]. |

| Room Temperature | Short-term (< 7 days) | Only recommended if using a dedicated preservative buffer (e.g., OMNIgene·GUT, DNA/RNA Shield). Unpreserved samples stored at room temperature show significant microbial divergence within hours [34] [32]. |

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Why did my sequencing fail, and how can I fix it?

Sequencing failure or poor data quality can often be traced back to issues during sample collection, stabilization, or DNA extraction.

Problem: Low DNA Yield or Poor Library Quality

- Cause 1: Inhibitors in the Sample. Complex samples like stool and soil contain substances (e.g., humic acids, bile salts) that co-purify with DNA and inhibit downstream enzymes [24].

- Cause 2: Inefficient Cell Lysis. Tough cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria and spores may not be broken open by gentle lysis methods, leading to skewed community data (lysis bias) [24].

- Cause 3: Inaccurate DNA Quantification. Using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) can overestimate DNA concentration due to non-DNA contaminants [4] [35].

Problem: Abnormal Microbial Community Profile

- Cause: Post-Collection Microbial Growth. If a sample is not stabilized immediately, hardier microbes (e.g., E. coli) can bloom during transit, outcompeting and obscuring more fastidious organisms [24].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and kits used in microbiome sample handling to ensure data quality and reproducibility.

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Research

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function | Key Features / Best Use Context |

|---|---|---|

| OMNIgene·GUT (DNA Genotek) | Sample preservation | Effective for stabilizing fecal microbiota at room temperature for up to 72 hours with minimal profile alteration [30] [32]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) | Sample preservation | Rapidly inactivates nucleases and microbes, preserving nucleic acids at ambient temperature; ideal for field collection [24]. |

| Monarch DNA/RNA Protection Reagent (NEB) | Sample preservation | Aqueous, non-toxic reagent for stabilizing nucleic acids in tissues, cells, and blood [34]. |

| MagMAX Microbiome Ultra Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems) | Nucleic acid extraction | Designed for simultaneous DNA and RNA extraction; suitable for high-throughput studies and SARS-CoV-2/viral metagenomics [36]. |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction | Efficiently lyses a wide range of microorganisms and removes PCR inhibitors from complex samples like stool [33]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA/RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) | Nucleic acid extraction | Includes bead-beating for mechanical lysis and is optimized for difficult-to-lyse, Gram-positive bacteria [24]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (Zymo Research) | Process control | A defined mock community of whole cells and DNA used to benchmark extraction and sequencing performance, identifying lysis and amplification biases [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why do my microbiome sequencing results not match known profiles, showing underrepresentation of certain taxa?

This is most commonly caused by lysis bias. Microbial communities contain species with different cell wall structures. Easy-to-lyse organisms (like Gram-negative bacteria) are overrepresented, while tough-to-lyse organisms (like Gram-positive bacteria and yeast) are underrepresented if lysis is incomplete due to their thick, resistant cell walls [37] [38].

- Solution: Implement mechanical lysis, particularly optimized bead beating [37]. Chemical or thermal lysis alone often fails to disrupt tough cell walls, leading to inaccurate community profiles [38].

Why does my PCR or sequencing fail or produce low yields even with detectable DNA?

This typically indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors in your DNA extract. Common inhibitors include:

- Humic acids (from soil or plants)

- Hematin (from blood)

- Bile salts (from fecal samples)

- Polysaccharides and polyphenols (from plant tissues) [39] [24]

These substances can co-purify with DNA and interfere with enzymatic reactions [24].

- Solution: Use purification kits specifically designed for inhibitor removal. Data comparing methods show that certain kits are highly effective at removing a wide spectrum of inhibitors [39].

How can I validate that my DNA extraction protocol is unbiased?

Use mock microbial community standards [24]. These are precisely defined mixtures of microorganisms with known proportions.

- Whole-cell mock communities: Contain intact cells of various species (including tough-to-lyse types); process through your entire DNA extraction workflow to test lysis efficiency and overall bias [24].

- DNA mock communities: Contain purified genomic DNA from various species; process starting from the library preparation step to test for downstream biases (PCR, sequencing) [24].

Deviations from the expected profile in a whole-cell standard indicate lysis and extraction bias, while deviations in a DNA standard indicate downstream issues [24].

Data Comparison Tables

Comparison of PCR Inhibitor Removal Methods

| Method | Effectiveness on Common Inhibitors | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit [39] | Effectively removed all 8 tested inhibitors (melanin, humic acid, collagen, bile salt, hematin, calcium, indigo, urea) at 1x, 2x, and 4x working concentrations [39]. | High effectiveness; designed for tough environmental inhibitors [39]. | - |

| DNA IQ System [39] | Effectively removed 7 of 8 inhibitors; partially removed Indigo [39]. | Combines DNA extraction and purification; convenient for forensic samples [39]. | May be less effective on specific dyes like indigo [39]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform Extraction [39] | Effectively removed only 3 of 8 inhibitors (melanin, humic acid, calcium ions) [39]. | Traditional method; useful for specific contaminants [39]. | Ineffective for many common inhibitors; uses hazardous chemicals [39]. |

| Chelex-100 Method [39] | Showed the worst performance in removing the tested PCR inhibitors [39]. | Simple and fast protocol [39]. | Limited effectiveness for broad inhibitor removal [39]. |

Recommended Bead Beating Parameters for Different Instruments

The following validated protocols for the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit ensure unbiased lysis [37]:

| Bead Beating Instrument | Recommended Protocol | Total Bead Beating Time |

|---|---|---|

| MP Fastprep-24 | 1 minute on at max speed, 5 minutes rest. Repeat cycle 5 times [37]. | 5 minutes |

| Biospec Mini-BeadBeater-96 (with 2 ml tubes) | 5 minutes on at Max RPM, 5 minutes rest. Repeat cycle 4 times [37]. | 20 minutes |

| Biospec Mini-BeadBeater-96 (with 96-well rack) | 5 minutes on at Max RPM, 5 minutes rest. Repeat cycle 8 times [37]. | 40 minutes |

| Bertin Precelys Evolution | 1 minute on at 9,000 RPM, 2 minutes rest. Repeat cycle 4 times [37]. | 4 minutes |

| Vortex Genie (with horizontal adaptor) | 40 minutes of continuous bead beating (max 18 tubes) [37]. | 40 minutes |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Unbiased DNA Extraction Using Bead Beating

This protocol is designed for comprehensive cell lysis in complex microbial communities [37].

- Sample Preparation: Transfer sample to a tube containing lysis buffer and a mixture of glass or ceramic beads [40].

- Mechanical Lysis:

- Post-Lysis Processing:

- Centrifuge the lysate to pellet debris and unlysed cells [40].

- Transfer the supernatant containing DNA to a new tube.

- DNA Purification and Inhibitor Removal:

- Use a commercial DNA clean-up kit (e.g., PowerClean) with a silica membrane or magnetic bead technology [39].

- Follow manufacturer instructions for binding, washing, and eluting DNA.

- DNA Elution: Elute purified DNA in a low-salt buffer (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water) [40].

Protocol: Validating Your Workflow with Mock Communities

Use this protocol to quantify bias in your entire workflow, from extraction to sequencing [24].

- Select Appropriate Standards:

- Whole-Cell Standard: Use to test the entire workflow (lysis, extraction, sequencing).

- DNA Standard: Use to test only downstream steps (library prep, sequencing).

- Parallel Processing:

- Process the whole-cell standard alongside your experimental samples using the identical protocol.

- In a separate run, process the DNA standard starting at the library preparation step.

- Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence both standards and analyze the data.

- Map the sequencing reads to the known reference genomes of the standard's constituents.

- Bias Calculation and Interpretation:

- Calculate the observed proportion of each species in the standard.

- Compare the observed proportion to the known theoretical proportion.

- Deviation in whole-cell standard only → Indicates lysis/extraction bias. Optimize bead beating.

- Deviation in both standards → Indicates downstream bias (e.g., from PCR or bioinformatics). Optimize library prep or analysis.

Workflow Visualization

Lysis Bias and Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard [37] [38] | A defined mock community of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and yeast, used as a positive control to validate DNA extraction efficiency and quantify lysis bias [37] [38]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit [37] | A DNA extraction kit validated with microbial standards to provide unbiased lysis, often incorporating optimized bead beating protocols [37]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield [24] | A sample preservative that immediately inactivates nucleases and microbes upon collection, stabilizing the true microbial profile at the point of collection and preventing shifts during storage or transport [24]. |

| PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit [39] | A purification kit specifically designed for the effective removal of a wide range of common PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids, hematin, collagen) from complex samples [39]. |

| Silica Membrane Columns or Magnetic Beads [40] [39] | The core matrix in many modern kits for binding DNA under high-salt conditions, allowing for the washing away of impurities and inhibitors, followed by elution of clean DNA [40] [39]. |

| Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerases [41] | Engineered PCR enzymes that are more tolerant to low levels of residual inhibitors that may remain after purification, providing an additional safeguard for downstream amplification [41]. |

What are the essential experimental controls in microbiome sequencing and why are they crucial?

In microbiome sequencing, essential experimental controls include negative controls, positive controls, and mock communities. These controls are fundamental for identifying technical biases, detecting contamination, and ensuring the validity and reproducibility of your research findings. Their use is a critical component of good scientific practice in microbiome research, helping to distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts [42].

Inclusion of these controls allows researchers to account for variability introduced during multi-step laboratory processes, from DNA extraction to sequencing. Without proper controls, results from microbiome studies—particularly those involving low-biomass samples—can be indistinguishable from contamination, potentially leading to erroneous biological conclusions [42].

Negative Controls

What are negative controls and what issues do they help identify?

Negative controls, often called "blanks," are samples that contain no expected microbial DNA from the biological sample. They undergo the entire experimental workflow alongside your biological samples, from DNA extraction to sequencing [42].

- Primary Function: To identify contamination from reagents, laboratory environment, or cross-sample contamination [43] [42].

- Interpretation: Microbial sequences detected in negative controls are likely contaminants that may also be present in your biological samples. These findings should be used to inform downstream filtering steps.

Troubleshooting Guide: Contamination in Negative Controls

| Observation | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High microbial biomass in negative control | Contaminated reagents (e.g., extraction kits, water) | Use ultrapure, DNA-free reagents; test new reagent batches [42] |

| Specific taxa consistently appear in blanks | Background lab contamination or cross-sample contamination | Improve sterile technique; use dedicated lab areas for pre- and post-PCR steps [42] |

| Low diversity contamination in negatives | Contamination from a single source (e.g., operator, specific reagent) | Use personal protective equipment; consider using single-use, aliquoted reagents [42] |

Positive Controls & Mock Communities

What is the difference between a positive control and a mock community?

While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, a mock community is a specific type of positive control. A positive control broadly refers to any sample with known content used to monitor performance, whereas a mock community is a precisely defined mixture of microbial cells or DNA from known species at defined ratios [44] [43] [42].

How should I use a mock community in my experiment?

Mock communities can be added to your sample at the start of DNA extraction (in situ MC) or as pre-extracted DNA just before PCR amplification (PCR spike-in) [44]. The experimental workflow is as follows:

What should I look for when analyzing my mock community results?

The key is to compare the experimental composition you obtained from sequencing to the theoretical, known composition of the mock community.

- Compositional Accuracy: Does the relative abundance of each species in your data match the expected ratios? Major deviations indicate extraction or amplification biases [43] [42].

- Correlation: Tools like

chkMockscalculate Spearman's correlation (rho) between the experimental and theoretical profiles. A high correlation indicates good technical performance [43]. - Unknown Taxa: The presence of taxa not part of the mock community suggests contamination [43].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mock Community Anomalies

| Observation | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Skewed abundance ratios | DNA extraction bias (e.g., against Gram-positive bacteria) | Optimize or change DNA extraction protocol [42] |

| Low correlation with expected composition | PCR amplification bias (e.g., due to GC content) | Optimize PCR conditions or primer choice [42] |

| Missing expected taxa | Primer mismatch or low sequencing depth | Validate primer specificity and ensure sufficient sequencing depth [42] |

| Appearance of unexpected taxa | Contamination | Review sterile technique and reagent quality; use negative controls to identify contaminant sources [43] |

Implementation & Best Practices

When should I include these controls in my experimental design?

Controls should be included in every batch of sample processing. For large studies, distribute controls across all sequencing runs to monitor and correct for batch effects [5] [42].

What are the recommended doses for mock communities?

The mock community should be spiked in at a level that does not overwhelm your biological signal. A 2023 study demonstrated that sample diversity estimates were distorted only when the mock community dose was high relative to the sample mass (e.g., when MC reads constituted more than 10% of total reads) [44].

How do I computationally handle controls in my data analysis?

- Negative Controls: Use their profiles to identify and filter contaminant sequences from your biological samples before downstream analysis [3].

- Mock Communities: Do not include them in your final biological analysis. Use them for quality assessment and to optimize bioinformatic parameters [43] [42].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and resources used for implementing essential controls in microbiome research.

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | A commercially available mock community with known ratios of bacteria and fungi | ZymoResearch [43] [42] |

| BEI Resource Mock Communities | Defined synthetic bacterial communities for use as positive controls | BEI Resources [42] |

| ATCC Mock Microbial Communities | Characterized mock communities for microbiome method validation | ATCC [42] |

| DNA/RNA-Free Water | A critical reagent for preparing negative controls to detect contaminating DNA | Various manufacturers [42] |

| chkMocks R Package | A bioinformatic tool for comparing experimental mock community data to theoretical composition | https://github.com/microsud/chkMocks/ [43] |

Decision-Making for Control Analysis

The following flowchart outlines a logical process for diagnosing issues based on your control results:

Sequencing Platform Considerations and Primer Selection

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do I choose between 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics for my study? 16S rRNA sequencing is a cost-effective method for bacterial community profiling that amplifies specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, making it ideal for large sample sizes or when focusing solely on bacterial composition [45]. Shotgun metagenomics sequences all genetic material in a sample, providing broader taxonomic coverage (including viruses and fungi), strain-level resolution, and functional insights into microbial communities [12] [45]. Your choice should depend on your research goals: 16S for cost-effective bacterial diversity surveys, and metagenomics for comprehensive taxonomic and functional analysis [46] [45].

2. What is the impact of primer selection on 16S rRNA sequencing results? Primer selection significantly influences your microbial composition results, as different primer pairs target different variable regions (V-regions) and can miss specific bacterial taxa entirely [47]. Studies demonstrate that microbial profiles cluster primarily by primer pair rather than by sample source, with certain primers failing to detect particular phyla [47]. The taxonomic resolution varies across variable regions, affecting your ability to distinguish closely related species [47] [48]. For consistent results, you should use the same primer pairs throughout your study and avoid comparing datasets generated with different primers [47].

3. What are the key differences between short-read and long-read 16S sequencing platforms? Short-read platforms like Illumina provide high accuracy (error rate <0.1%) but are limited to sequencing specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4), which restricts species-level identification [49]. Long-read platforms from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequence the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp), enabling superior species-level resolution despite historically higher error rates [45] [49] [50]. ONT's main advantage is real-time sequencing with rapidly improving accuracy (now >99%), while PacBio's circular consensus sequencing achieves exceptional accuracy exceeding 99.9% [45] [50].

4. How do clustering methods (OTU vs. ASV) affect my data analysis? Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) methods cluster sequences based on similarity thresholds (typically 97%), which can merge similar species and potentially reduce measured diversity [45] [51]. Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) methods distinguish biological sequences from errors at single-nucleotide resolution, providing finer taxonomic discrimination and consistent labels across studies [47] [45] [51]. ASV approaches like DADA2 generally produce more consistent outputs but may over-split sequences from the same strain, while OTU methods like UPARSE achieve clusters with fewer errors but risk over-merging distinct taxa [51].

Sequencing Platform Comparison

Table 1: Technical specifications of major sequencing platforms for microbiome analysis

| Platform | Read Length | Key Applications | Error Rate | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Short-read (150-500 bp) | Targeted hypervariable regions (V3-V4, V4) | <0.1% [49] | High accuracy, cost-effective for large studies [49] | Limited species-level resolution [49] |