Metatranscriptomics: Analyzing Active Microbial Communities for Biomedical Breakthroughs

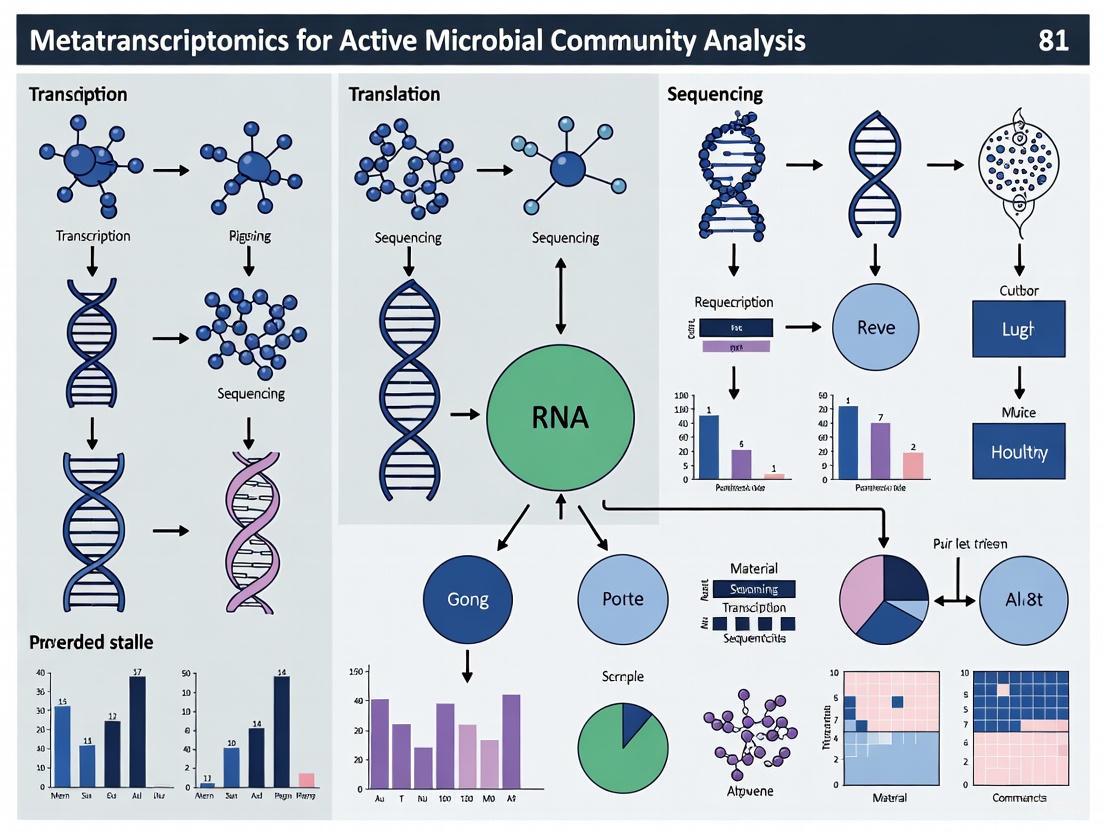

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metatranscriptomics, a powerful method for profiling gene expression in entire microbial communities.

Metatranscriptomics: Analyzing Active Microbial Communities for Biomedical Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metatranscriptomics, a powerful method for profiling gene expression in entire microbial communities. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that distinguish this technique from metagenomics, detailing its workflows from sampling to bioinformatics. The content covers diverse methodological applications in human health and drug discovery, addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies, and validates the approach through comparative benchmarking and multi-omics integration. The article concludes by synthesizing how metatranscriptomics is revolutionizing our understanding of active microbial functions in disease and health, offering critical insights for developing novel therapeutic and diagnostic strategies.

Beyond DNA: How Metatranscriptomics Reveals the Active Microbiome

Metatranscriptomics is the set of techniques used to study the gene expression of microbes within natural environments, collectively known as the metatranscriptome [1]. While metagenomics provides a taxonomic profile of a microbial community by revealing "who is there," metatranscriptomics advances this understanding by characterizing the active functional profile, showing what functions the community is performing at a specific point in time [1] [2]. This approach provides a dynamic picture of the state and activity of a microbiome by focusing on changes in gene expression, capturing the collective mRNA transcripts of an entire microbial community to reveal actively expressed genes and metabolic activities [3] [4].

The fundamental advantage of metatranscriptomics lies in its ability to provide information about differences in the active functions of microbial communities that would otherwise appear to have similar taxonomic make-up [1]. By analyzing the collective microbial transcriptome, researchers can identify microbial expressed genes and associated functions, and identify the metabolically active members of the community [5]. This dynamic view offers a more accurate representation of microbial activity compared to metagenomics, which captures the static genetic blueprint of the community [4].

Key Methodological Approaches

Experimental Workflow and Technical Considerations

The standard metatranscriptomic sequencing workflow involves multiple critical steps to ensure high-quality data. The process begins with sample harvesting, where rapid stabilization of RNA is crucial due to the inherent instability of mRNA [1] [6]. RNA extraction follows, with methods varying depending on sample type, after which the extracted total RNA undergoes qualification checks including RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment, with values ≥6.5 typically required for proceeding [7].

A pivotal technical challenge is mRNA enrichment, as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes the majority of cellular RNA and can strongly reduce coverage of mRNA if not effectively removed [1] [6]. The two main strategies for mRNA enrichment include removing rRNA through capture using hybridization with 16S and 23S rRNA probes, or depletion of rRNAs through a 5-exonuclease approach [1] [6]. Following mRNA enrichment, cDNA synthesis is performed using reverse transcriptase, sequencing libraries are prepared, and high-throughput sequencing is conducted, primarily using Illumina platforms [1] [3] [7].

Table 1: Key Technical Challenges in Metatranscriptomics and Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | Current Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| High rRNA abundance | Reduces mRNA sequencing coverage; can dominate datasets | Probe-based rRNA depletion; exonuclease treatment [1] [6] |

| RNA instability | Compromises sample integrity before sequencing | Rapid sample stabilization; optimized extraction protocols [1] [6] |

| Host RNA background | Limits microbial transcript detection in host-associated samples | Commercial enrichment kits; in silico removal post-sequencing [1] [5] |

| Limited reference databases | Reduces annotation completeness for novel microbes | Use of multiple databases; development of customized databases [1] [6] |

Computational Analysis Pipelines

The computational analysis of metatranscriptomic data involves multiple steps that can be approached through different strategies. A typical analysis begins with quality control of raw sequencing reads, adapter trimming, and removal of low-quality sequences [1] [3]. For taxonomic profiling, researchers can choose between marker-based methods like MetaPhlAn and mOTUs that use conserved genes, or k-mer based methods like Kraken 2/Bracken that use whole-genome information [5].

For functional analysis, HUMAnN is a widely used pipeline that implements a "tiered search" approach: first identifying known microbes, then constructing a sample-specific database, and finally performing translated searches against protein databases for unclassified reads [1]. Alternative pipelines like SAMSA2 offer simplified analysis by working with the MG-RAST server, while MetaTrans provides a flexible framework that supports multithreading for improved efficiency [1].

Recent advancements include integrated pipelines like metaTP, which provides end-to-end automation from data preprocessing to differential expression analysis and functional annotation [8]. This pipeline integrates tools for quality control, rRNA removal, transcript assembly, expression quantification, and co-expression network analysis, significantly improving reproducibility in metatranscriptomic studies [8].

Applications in Microbial Community Analysis

Human Health and Disease Mechanisms

Metatranscriptomics has revolutionized our understanding of host-microbiome interactions in human health. In the gut microbiome, metatranscriptomics can reveal how microbial communities respond to dietary changes, pharmaceutical interventions, and disease states by identifying actively expressed pathways [1] [4]. For example, studies of toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) knockout mice used metatranscriptomics to show that flagellar motor-related gene expression was up-regulated compared to wild-type mice, revealing how host genetics shapes microbial behavior [6].

A significant advancement is the application of metatranscriptomics to human tissue specimens with low microbial biomass, such as mucosal interfaces of the gastrointestinal tract [5]. This approach has been successfully used to characterize the functional activity of the mucosal microbiome in gastric tissues, uncovering critical interactions between the microbiome and host in health and disease [5]. Such applications are particularly valuable for understanding diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where researchers can identify dysregulated pathways, microbial biomarkers, and potential therapeutic targets by analyzing microbial gene expression patterns [4].

Environmental and Industrial Applications

Beyond human health, metatranscriptomics provides critical insights into diverse environments. In agricultural systems, it helps explore how microbial soil populations promote plant health and productivity, with applications in developing sustainable farming practices [6]. Environmental monitoring utilizes metatranscriptomics to assess ecosystem health by analyzing how microbial communities respond to pollutants, contaminants, and other stressors [4].

In biotechnology, metatranscriptomics facilitates the design of microbial consortia for applications including bioremediation, biofuel production, and industrial fermentation [6] [4]. By analyzing gene expression patterns in synthetic microbial communities, researchers can optimize consortia composition and metabolic pathways to enhance process efficiency [4]. The approach also enables drug discovery by identifying novel bacterial compounds in unculturable microorganisms, expanding accessible resources for pharmaceutical development [6] [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Metatranscriptomic Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome Kit | Depletion of ribosomal RNA from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms | Enhances mRNA coverage in complex microbial samples [9] |

| Microbiome RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from diverse sample types | Ensures RNA integrity (RIN ≥5) for downstream analysis [9] |

| Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome | rRNA depletion for complex microbial samples | Optimizes library preparation for metatranscriptomic sequencing [9] |

| Custom HiPR-FISH Probes | Combinatorial fluorescent labeling for spatial mapping | Enables visualization of microbial spatial organization in communities [10] |

| SRA Toolkit | Data download and format conversion | Facilitates access to publicly available metatranscriptomic datasets [8] |

Integrated Protocols for Metatranscriptomic Analysis

Protocol for Samples with Low Microbial Biomass

Analysis of samples with low ratios of microbial to host cells (e.g., human tissue specimens) requires specialized approaches:

Sample Preparation: Collect samples with stringent precautions to avoid contamination. Immediately stabilize RNA using appropriate preservatives and store at -80°C prior to processing [5].

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Extract total RNA using kits designed for microbiome RNA extraction. Verify RNA quality using an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥6.5 and purity ratios (A260/280 ≥2.0; A260/230 ≥2.0) [5] [7].

rRNA Depletion and Library Preparation: Perform both prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA depletion to enrich mRNA. Prepare sequencing libraries using protocols optimized for metatranscriptomics, such as those incorporating the Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome workflow [5] [9].

High-Depth Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq or similar platforms with high depth (~15 Gbp) to maximize detection of microbial sequences [5] [7].

Computational Analysis:

- Preprocess raw data: trim adapters, remove low-quality reads, and filter host sequences [5] [8].

- Perform taxonomic profiling using optimized Kraken 2/Bracken with confidence threshold set to 0.05 to balance sensitivity and precision [5].

- Conduct functional analysis using HUMAnN 3, which stratifies community functional profiles according to contributing species [5].

- Perform in silico decontamination to remove potential contaminant taxa [5].

Protocol for Standard Microbe-Rich Samples

For samples with high microbial load (e.g., stool, environmental samples):

Sample Processing: Extract total RNA ensuring rapid processing to maintain RNA integrity. For soil or complex environmental samples, use specialized extraction protocols that effectively lyse diverse microbial cells [1] [6].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Deplete rRNA using either probe-based capture or exonuclease treatment. Prepare libraries and sequence using Illumina platforms (PE 150bp recommended), with ≥20 million read pairs per sample [7].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control using FastQC and adapter trimming with Trimmomatic [8].

- Remove rRNA sequences using bowtie2 against rRNA databases [8].

- Choose analysis path based on research question:

- Annotate contigs using eggNOG-mapper, KEGG, GO, and COG databases [1] [8].

- Quantify gene expression using Salmon with TPM normalization [8].

- Perform differential expression analysis using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., Wilcoxon rank-sum test) [8].

Comparative Analysis with Related Techniques

Metatranscriptomics vs. Metagenomics

While metatranscriptomics and metagenomics are complementary approaches, they address fundamentally different questions in microbiome research. Metagenomics investigates the genetic potential of a community by sequencing DNA, revealing which microbes are present and what functions they could potentially perform [2] [4]. In contrast, metatranscriptomics examines the realized functions by sequencing RNA, showing which genes are actively expressed and what functions the community is actually performing at the time of sampling [4] [9].

This distinction has practical implications for experimental design and interpretation. Metagenomics provides a static snapshot of community composition and functional potential, while metatranscriptomics offers dynamic insights into gene expression patterns, metabolic activities, and responses to environmental changes [4]. For understanding functional activities and community dynamics, metatranscriptomics provides a more accurate representation of microbial activity, as the presence of a gene in a metagenome does not guarantee its expression [1] [4].

Integration with Other Omics Approaches

The most comprehensive understanding of microbial communities emerges from integrating multiple omics approaches. Metatranscriptomics forms a critical bridge between metagenomic potential and metabolic activity [2]. When combined with metabolomics, which identifies the byproducts released into the environment, researchers can connect gene expression with functional outcomes [2].

Recent advances in spatial techniques like HiPR-FISH (high-phylogenetic-resolution microbiome mapping by fluorescence in situ hybridization) further enhance metatranscriptomic insights by revealing the spatial organization of microbes within communities [10]. This integration helps generate hypotheses about how physical proximity influences functional interactions between microbial species.

Network-based approaches applied to integrated multi-omics datasets represent the cutting edge of microbiome analysis, enabling sophisticated in-depth understanding of microbiomes and leading to critical insights into microbial world [2]. The second phase of the Human Microbiome Project (iHMP) exemplifies this trend, gathering multiple omic data from both microbiome and host to understand host-microbiome interactions through integrative analyses [2].

Core Principles and Research Applications

Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics are foundational tools for studying microbial communities, but they answer fundamentally different biological questions. Metagenomics reveals the genetic potential of a microbiome, detailing "what microbes could do" by analyzing the total DNA present in a sample. It provides a census of which organisms are present and what genes they possess [11] [12]. In contrast, metatranscriptomics reveals the active functional state of a community, showing "what microbes are actually doing" at the time of sampling by sequencing the total mRNA [11] [12] [13]. This key difference dictates their respective applications in research and drug development.

The table below summarizes the core differentiators between these two approaches.

Table 1: Core Differentiators Between Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

| Comparison Dimension | Metagenomics | Metatranscriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| Research Core | Analyzes microbial DNA to reveal community composition and functional potential [11]. | Analyzes microbial RNA to reveal active gene expression and real-time activity [11]. |

| Primary Output | Catalog of microbial taxa and their gene complement. | Snapshot of actively transcribed genes and pathways. |

| Temporal Resolution | Static; represents the stable genetic blueprint. | Dynamic; captures a moment in time, reflecting response to the environment. |

| Key Application | Discovering novel microbial species and genes, characterizing community structure [14]. | Understanding functional mechanisms in disease, fermentation, or host-microbe interactions [15] [12]. |

| Relation to Disease | Identifies microbial signatures associated with a diseased state (e.g., species depletion or enrichment) [13]. | Reveals active virulence mechanisms and metabolic pathways driving disease pathology [15] [13]. |

Synergistic Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Research

The power of these technologies is often greatest when used together. An integrated multi-omics approach can link genetic potential with actual activity, providing a comprehensive view of microbiome function.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Multi-omics studies have shown that a depletion of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the gut is correlated with reduced production of butyrate, a key anti-inflammatory metabolite. Metatranscriptomics can confirm the active downregulation of butyrate synthesis pathways, providing a functional explanation for the observed dysbiosis [14].

- Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Risk: The TEDDY project analyzed thousands of stool samples from children and found that microbial functional pathways, particularly those involved in choline metabolism and cobalamin biosynthesis, were stronger correlates of β-cell autoimmunity than taxonomic composition alone. This highlights the need to move beyond census-taking to understand functional activity in disease progression [14].

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): A 2025 study integrated metatranscriptomics with genome-scale metabolic modeling to characterize the active metabolic functions of patient-specific urinary microbiomes. This approach revealed distinct virulence strategies and metabolic cross-feeding between pathogens, which would be invisible to DNA-based sequencing alone [15].

Technical Workflows and Methodologies

The experimental and computational workflows for metagenomics and metatranscriptomics share similarities but have critical differences tailored to their target molecules (DNA vs. RNA).

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

The initial stages of the workflows are where the most significant technical distinctions lie, primarily due to the instability of RNA and the need to enrich for informative transcripts.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Metatranscriptomic Workflows

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Bead-beating (Metagenomics) | Breaks open diverse microbial cell walls in environmental samples via mechanical force to release DNA [11]. |

| Enzymatic Digestion (Metatranscriptomics) | Gently disperses tissue or cell line samples while minimizing damage to fragile RNA molecules [11]. |

| RiboPOOLs / MICROBExpress | Probe-based kits for subtractive hybridization that remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), enriching the messenger RNA (mRNA) fraction for sequencing [12]. |

| MICROBEnrich Kit | Uses hybridization capture technology to remove host-derived RNA, thereby increasing the proportion of microbial reads in the dataset [12]. |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | A library preparation kit effective for low-input RNA, ensuring efficient representation of microbial transcripts [12]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used during RNA extraction to digest contaminating genomic DNA, ensuring sequence data derives purely from transcripts [12]. |

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

The computational analysis of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data requires robust pipelines to handle large, complex datasets.

Metagenomic Analysis: Standard pipelines involve quality control (FastQC, Trimmomatic), host DNA depletion (Bowtie2), and assembly into contigs using tools like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes [14]. These contigs are then binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using tools like MetaBAT2, which groups contigs based on sequence composition and abundance across samples [14]. Taxonomic profiling is performed with classifiers like Kraken2 against databases such as the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB), and functional potential is annotated using tools like eggNOG-mapper for KEGG orthology [14].

Metatranscriptomic Analysis: After sequencing, the raw reads undergo quality control and filtering. A critical step is the removal of residual rRNA sequences using tools like SortMeRNA [12]. High-quality mRNA reads are then aligned to reference genomes or metagenomic assemblies from the same sample set. Differential gene expression analysis is performed using specialized statistical packages like EdgeR or DeSeq2 to identify genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated under different conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) [12]. Integrated pipelines such as SAMSA2, HUMAnN2, or MetaTrans can automate many of these steps [12].

Experimental Protocol: Metatranscriptomic Analysis of a Microbial Community

The following protocol is adapted from recent studies investigating active microbial communities in clinical and environmental contexts [15] [12] [16].

Sample Collection, RNA Extraction, and Library Preparation

Goal: To obtain high-quality, representative cDNA libraries from a microbial community for sequencing.

Materials:

- RNase-free collection tubes and swabs.

- RNA stabilization solution (e.g., RNAlater).

- PowerSoil Total RNA Isolation Kit (or equivalent).

- RiboPOOLs depletion kit for bacterial rRNA.

- SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit.

- Agencourt RNAClean XP beads or similar.

Procedure:

- Collection & Stabilization: Collect sample (e.g., stool, soil, water filtrate) directly into a tube containing RNA stabilization solution. Immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until processing. Critical: Minimize delay between collection and stabilization to preserve RNA integrity.

- RNA Extraction: Use a bead-beating mechanical lysis protocol to ensure rupture of diverse microbial cell walls. Extract total RNA following the manufacturer's instructions, including an on-column DNase I digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination. Quantify RNA using a Qubit Fluorometer and assess integrity with an Agilent Bioanalyzer (RIN >7.0 is desirable).

- rRNA Depletion & Enrichment: Deplete ribosomal RNA from 1 µg of total RNA using a RiboPOOLs kit, following the subtractive hybridization protocol. This step enriches the messenger RNA (mRNA) fraction.

- Library Preparation: Convert the enriched mRNA to double-stranded cDNA using the SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit, which incorporates random priming for prokaryotic mRNA. Synthesize cDNA and perform library amplification with Illumina-compatible index adapters. Purify the final library using AMPure XP beads.

- Quality Control & Sequencing: Validate the library size distribution on a Bioanalyzer and quantify by qPCR. Pool equimolar amounts of libraries and sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (e.g., 2x150 bp PE) to a minimum depth of 20-50 million reads per sample.

Computational Analysis of Metatranscriptomic Data

Goal: To process raw sequencing data into biologically interpretable information on active microbial functions.

Software & Databases:

- FastQC, Trimmomatic, SortMeRNA, bowtie2, DIAMOND, MetaTrans/SAMSA2 pipeline, EdgeR/DeSeq2, KEGG/EGGNOG databases.

Procedure:

- Pre-processing: Assess raw read quality with FastQC. Use Trimmomatic to remove adapters and low-quality bases (leading:3 trailing:3 slidingwindow:4:15 minlen:50).

- rRNA Filtering: Align reads against rRNA databases using SortMeRNA and remove matching sequences to obtain a cleaned set of mRNA reads.

- Taxonomic & Functional Assignment: For genome-resolved analysis, map reads to metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from a companion metagenomic study using bowtie2. Alternatively, for direct functional assignment, use a pipeline like HUMAnN2 or perform alignment with DIAMOND (BLASTX) against a protein database (e.g., NR, UniRef90). Assign KEGG Orthology (KO) terms and map to metabolic pathways.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Compile read counts per gene or pathway in a count matrix. Import into R and use EdgeR or DeSeq2 to perform statistical testing for differential abundance/expression between sample groups (e.g., healthy vs. diseased). Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg); a common significance threshold is FDR < 0.05.

- Data Integration & Visualization: Integrate metatranscriptomic activity data with metagenomic abundance data to calculate activity-over-abundance ratios. Visualize results using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), heatmaps of differentially expressed pathways (e.g., complex I-V of oxidative phosphorylation), and pathway enrichment plots.

In the study of microbial communities, traditional metagenomics has provided a powerful lens for viewing genetic potential by sequencing DNA. However, it offers a static picture, cataloging which genes are present but not which are actively functioning at a specific point in time [17]. Messenger RNA (mRNA) analysis, the cornerstone of metatranscriptomics, bridges this gap by capturing the dynamically expressed genes that drive microbial responses to their environment. This shift from potential to activity is fundamental for understanding true microbial function, as mRNA levels provide a direct snapshot of the genes being transcribed to perform tasks like nutrient acquisition, virulence, and stress response [15]. By analyzing mRNA, researchers can move beyond cataloging community members to interpreting their active metabolic roles, interactions, and contributions to health and disease states.

The Critical Role of mRNA in Microbial Analysis

Unveiling the Active Microbial Community

The composition of a microbial community revealed by DNA sequencing can differ significantly from the subset of microbes that are transcriptionally active. mRNA analysis is critical because it identifies the active contributors to community function. For instance, a landmark skin metatranscriptomics study demonstrated that Staphylococcus species and the fungus Malassezia had an "outsized contribution to metatranscriptomes at most sites, despite their modest representation in metagenomes" [17]. This divergence between genomic abundance and transcriptomic activity highlights that numerically minor members can be metabolically dominant, a finding crucial for identifying true keystone species in a community.

Quantifying Gene Expression and Metabolic Activity

mRNA analysis allows for the quantification of gene expression levels, which can be directly linked to metabolic activity. This principle was powerfully illustrated in a study of urinary tract infections (UTIs), where researchers integrated metatranscriptomic data with genome-scale metabolic modeling (GEMs). They found that constraining these metabolic models with gene expression data "narrows flux variability and enhances biological relevance" [15]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies that relied on mRNA analysis to decipher microbial activity.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Microbial mRNA Studies

| Study Focus | Method Used | Key Quantitative Finding | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Single-Cell Analysis [18] | Bacterial MATQ-seq | Detects 300-600 genes/cell with a 95% success rate | Enables high-resolution analysis of individual cell states within a population. |

| Urinary Microbiome [15] | Metatranscriptomics + GEMs | Revealed marked inter-patient variability in transcriptional activity and metabolic behavior. | Underscores the need for patient-specific understanding of infections. |

| Skin Microbiome [17] | Metatranscriptomics | Identified >20 genes putatively mediating microbe-microbe interactions. | Uncovers the molecular basis of microbial ecology on the skin. |

Characterizing Virulence and Pathogen Response

For pathogens, mRNA analysis is indispensable for understanding virulence and adaptive responses. In a study of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains from UTI patients, mapping mRNA reads to a reference genome allowed researchers to profile the expression of virulence factors. They identified highly expressed genes related to adhesion (fimA, fimI) and iron acquisition (chuY, chuS, iroN), revealing "UPEC’s flexible virulence strategies and its ability to adapt to diverse host environments" [15]. This level of insight is critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies that target active pathogenic processes rather than just the presence of a pathogen.

Experimental Protocols for Microbial mRNA Analysis

The following section outlines a robust, end-to-end protocol for microbial metatranscriptomics, from sample collection to data analysis, incorporating best practices from recent studies.

Sample Collection, RNA Extraction, and Library Preparation

A reliable protocol begins with sample preservation and effective RNA extraction, which are particularly crucial for low-biomass environments like the skin [17].

- Sample Collection and Preservation: For skin and other surfaces, swabbing is a common, non-invasive method. To preserve RNA integrity, samples should be immediately placed into a stabilization solution like DNA/RNA Shield [17]. For other sample types, such as microbial cultures or patient specimens, rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen or similar methods is standard.

- RNA Extraction: Effective lysis often requires a combination of chemical and mechanical methods. The TRIzol method is recommended for maintaining RNA integrity during homogenization [19]. This should be coupled with bead beating to ensure complete lysis of robust microbial cells [17].

- rRNA Depletion and Library Construction: Since ribosomal RNA (rRNA) can constitute 80-90% of total RNA, its removal is essential for enriching the mRNA signal [19]. This is achieved using custom oligonucleotides that selectively deplete rRNA sequences, significantly enriching non-rRNA reads (e.g., from 2.5x to 40x) [17]. Following depletion, cDNA libraries are constructed using kits such as the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina [20]. For studies focusing on eukaryotic mRNA, poly-A enrichment can be used, while rRNA depletion is universally applicable for mixed microbial communities [19].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Microbial mRNA Analysis

| Research Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield | Stabilizes RNA at the point of collection, preventing degradation. | Critical for field and clinical sampling to preserve an accurate snapshot of gene expression [17]. |

| TRIzol Reagent | Monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for effective cell lysis and RNA isolation. | Maintains RNA integrity during homogenization; effective for diverse sample types [19]. |

| Custom rRNA Depletion Oligos | Biotinylated oligonucleotides that hybridize and remove rRNA sequences. | Custom panels designed for the expected community increase mRNA enrichment efficiency [17]. |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing-ready cDNA libraries from RNA samples. | A widely used, robust kit for constructing high-quality Illumina sequencing libraries [20]. |

Computational Analysis and Data Interpretation

After sequencing, raw data must be processed to extract biological meaning. A typical bioinformatics workflow is outlined below.

- Read Quality Control and Alignment: Raw sequencing reads (in FASTQ format) are first processed for quality control, which includes removing low-quality bases and adapter sequences. The cleaned reads are then aligned to a reference genome or a custom microbial gene catalog (e.g., the integrated Human Skin Microbial Gene Catalog, iHSMGC) using aligners like TopHat2 or modern alternatives [20] [17].

- Quantification and Differential Expression: Aligned reads are assigned to genomic features (genes) using tools like HTSeq to generate a raw count table [20]. This count table is then imported into statistical analysis environments like R. The table is filtered to remove low-count genes, and normalized using methods like TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) in the

edgeRpackage to account for technical variation between samples [21]. Finally, differential expression analysis is performed using packages likelimmaoredgeRto identify genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated under different conditions (e.g, treatment vs. control) [21]. - Functional and Metabolic Interpretation: Differentially expressed genes are annotated using databases such as the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) or Gene Ontology (GO) [15] [19]. For a systems-level view, gene expression data can be integrated with Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs). This involves constraining the flux bounds of metabolic reactions in the model based on transcript levels, which refines predictions of microbial metabolism in situ and reveals active pathways [15].

The following diagram visualizes the complete experimental and computational workflow:

Diagram 1: End-to-end workflow for microbial metatranscriptomics analysis.

Application Notes: Metatranscriptomics in Action

Case Study: Patient-Specific Urinary Tract Infection Analysis

A metatranscriptomic study of UTIs caused by uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) showcased the power of mRNA analysis to reveal patient-specific pathogen strategies. Researchers analyzed 19 female patients and reconstructed personalized community metabolic models constrained by gene expression data. This approach revealed that while the primary pathogen (UPEC) was common, its metabolic behavior and virulence gene expression varied dramatically between patients [15]. For example, the activity of pathways like arginine and proline metabolism and the pentose phosphate pathway was highly variable. This finding underscores that a one-size-fits-all therapeutic approach may be ineffective and highlights the potential for microbiome-informed, personalized treatment strategies for managing complex infections.

Case Study: Uncovering Active Interactions in the Skin Microbiome

The application of a robust skin metatranscriptomics workflow to 27 healthy adults revealed a landscape of active microbial functions and interactions. By moving beyond DNA, the study found that commensal skin microbes, including staphylococci and lactobacilli, actively transcribe diverse antimicrobial genes, including uncharacterized bacteriocins, in situ [17]. Furthermore, by correlating microbial gene expression with the abundance of other microbes, the study identified more than 20 genes that putatively mediate microbe-microbe interactions. One such finding was a secreted protein from Malassezia restricta that had a strong negative association with Cutibacterium acnes, suggesting active competition. This demonstrates how mRNA analysis can pinpoint specific molecular mechanisms governing the stability and dynamics of microbial ecosystems.

mRNA analysis through metatranscriptomics is not merely a complementary technique to metagenomics; it is a fundamental tool for shifting from a census of microbial citizens to a functional assessment of their active jobs and interactions. As the cited protocols and case studies demonstrate, it enables researchers to identify metabolically dominant species, quantify virulence and stress responses, model community metabolism with high fidelity, and discover the molecular basis of microbe-microbe interactions. By capturing the dynamic transcriptome of microbial communities, researchers and drug development professionals can gain a mechanistic, patient-specific understanding of infectious diseases and microbiome-associated conditions, paving the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The traditional view of microorganisms as isolated, free-living entities has been fundamentally replaced by the understanding that hosts and their associated microbial communities form an inseparable biological unit. The concept of the microbiome has evolved significantly from its initial definition. A revisited, comprehensive definition describes it as a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonable habitat, which includes not only the microorganisms but also their structural elements, metabolic activities, and resulting ecological functions [22]. This expanded view positions the microbiome not merely as a collection of passengers but as an integral functional component of the host system, influencing host physiology, evolution, and health.

This perspective is central to the holobiont concept, which posits that the eukaryotic host and its microbiota form a single evolutionary unit [23] [22]. The interactions within this holobiont are governed by co-evolutionary principles and have profound implications for understanding host health, disease, and adaptation. The microbiome extends the host's genetic repertoire, forming what can be termed the "Extended Genotype" [23]. From a quantitative genetics perspective, the host's phenotypic variance (VP) can thus be decomposed to include not only host genetic variance (VG-HOST) and environmental variance (VE), but also the genetic variance contributed by the microbiome (VG-MICROBE): VP = VG-HOST + VG-MICROBE + VE [23]. This framework allows researchers to formally partition the contribution of microbial genetic variation to host phenotypes, thereby shaping the host's evolutionary potential.

Key Components of the Expanded Microbiome Definition

The expanded microbiome definition necessitates consideration of a complex web of interactions and components. The table below summarizes the core elements that move beyond a simple taxonomic catalogue of microbes.

Table 1: Core Components of the Expanded Microbiome Definition

| Component | Description | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Host Factors | Host genetics, immune status, age, and sex that influence microbiome composition and function [23] [22]. | Requires recording detailed host metadata in studies [24]. |

| Microbiota | The assemblage of microorganisms present, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, and protists [22]. | Culture-independent methods (e.g., 16S/18S rRNA, ITS sequencing) are essential for comprehensive characterization [22]. |

| Structural Elements | The physical organization of microbes, including biofilms and other microbial structures [22]. | Highlights the importance of spatial analysis techniques in microbiome research. |

| Metabolic Activity | The functional output of the microbiome, including transcripts, proteins, and metabolites [22] [15]. | Metatranscriptomics and metabolomics are needed to move beyond census-taking to functional insight. |

| Environmental Context | Diet, lifestyle, geography, and environmental exposures that shape the microbiome [23] [22] [24]. | Demands longitudinal study designs and extensive environmental metadata collection [24]. |

| Microbial Networks | The ecological interactions (cooperation, competition) between microbial species within the community [22]. | Network analysis and correlation metrics are key tools for understanding community stability and function [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing the Active Microbiome

To operationalize the expanded microbiome definition and move from structure to function, metatranscriptomics has emerged as a powerful tool. It allows for the characterization of the collective gene expression profile of a microbial community, thereby revealing the metabolically active processes in response to host and environmental factors.

Protocol: Metatranscriptomic Workflow for Active Community Profiling

The following protocol is adapted from recent applications in clinical and environmental research [15] [16].

I. Sample Collection and Preservation

- Critical Step: Rapid stabilization of RNA is essential to preserve the in-situ transcriptional profile. Immediately freeze samples in liquid nitrogen or use a commercial RNA stabilization reagent.

- Clinical Note (e.g., Urine): Collect mid-stream urine from patients, centrifuge to pellet cells, and preserve the pellet in RNA-later [15].

- Environmental Note (e.g., Sludge): Collect aggregates of different sizes (e.g., flocs vs. granules) separately to investigate spatial functional heterogeneity [16].

II. RNA Extraction, Depletion, and Sequencing

- Total RNA Extraction: Use mechanical lysis (e.g., bead beating) followed by a phenol-chloroform extraction or a commercial kit designed for complex environmental samples.

- rRNA Depletion: Treat the total RNA with kits to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute >90% of the total RNA. This enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct cDNA libraries from the enriched mRNA and sequence using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

III. Bioinformatic Processing and Analysis

- Quality Control and Trimming: Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to assess read quality and remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases.

- Host Read Depletion: If working with a host-associated microbiome, align reads to the host genome (e.g., human, plant) and remove matching sequences to focus on microbial transcripts.

- Assembly and Mapping:

- Assembly-Based Approach: De novo assemble quality-filtered reads into longer contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes.

- Mapping-Based Approach: Map quality-filtered reads directly to a database of reference genomes or gene catalogs.

- Taxonomic and Functional Annotation:

- Assign taxonomy to contigs or mapped reads using tools like Kraken2 or by blasting against databases (NCBI nr, GTDB).

- Annotate predicted genes against functional databases such as KEGG, COG, or Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) to determine active pathways [15].

- Genome-Resolved Metatranscriptomics (Advanced): For higher-resolution insights, bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) and then map transcriptomic reads back to these MAGs to link activity to specific microbial populations [16].

IV. Integration with Metabolic Modeling

- Model Reconstruction: Create Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) for key microbial taxa identified in the community using resources like AGORA2 or ModelSeed [15].

- Contextualization: Constrain the flux through reactions in the GEMs using the gene expression data (FPKM/TPM values) from the metatranscriptomics analysis.

- Simulation: Simulate community metabolism in a defined in-silico medium (e.g., virtual urine, synthetic wastewater) to predict metabolic cross-feeding, nutrient consumption, and product secretion [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metatranscriptomics

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity instantly upon sample collection by inhibiting RNases. | Critical for capturing a snapshot of true in-situ gene expression; required for any field sampling. |

| Bead Beating Matrix | Mechanically disrupts robust microbial cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, spores) for efficient RNA extraction. | Matrix material (e.g., silica, zirconia) and bead size must be optimized for the sample type. |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Selectively removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for messenger RNA, dramatically improving sequencing depth of informative transcripts. | Prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA require different probes; choose a kit appropriate for the community. |

| Reverse Transcriptase & Library Prep Kit | Synthesizes stable cDNA from enriched mRNA and prepares it for sequencing with the addition of adapters and indexes. | High-processivity enzymes are preferred for complex RNA mixtures. Unique dual indexing mitigates index hopping. |

| Functional & Taxonomic Databases | Provides a reference for annotating sequenced genes and transcripts (e.g., KEGG, VFDB, NCBI nr). | Database choice influences results; using curated, specialized databases (e.g., VFDB for virulence factors) is often beneficial [15]. |

| Metabolic Model Database | Provides pre-built genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., AGORA2) for key microbes to facilitate functional modeling [15]. | Allows for rapid reconstruction of community metabolic networks without building models from scratch. |

Data Presentation and Analysis in Practice

Applying the expanded definition requires robust and standardized data analysis. A key initial step in many microbiome studies is the assessment of alpha diversity, which describes the within-sample diversity. However, this is not a single metric but a set of complementary concepts.

Table 3: A Guide to Key Alpha Diversity Metrics for Microbiome Studies [26]

| Metric Category | Key Metrics | What It Measures | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | The number of different species (or ASVs) in a sample. | Simple estimate of community complexity. High richness often correlates with ecosystem stability. |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Faith's PD | The sum of the phylogenetic branch lengths representing all species in a sample. | Accounts for evolutionary relationships; a community with distantly related species has higher PD. |

| Dominance/Evenness | Simpson, Berger-Parker, ENSPIE | The relative abundance distribution of species (i.e., whether a few taxa dominate). | Berger-Parker is the proportion of the most abundant taxon. Low evenness suggests dominance. |

| Information Indices | Shannon, Pielou's Evenness | Combines richness and evenness into a single metric of diversity. | Shannon entropy increases with both more species and more uniform distribution. |

The analysis of data from a metatranscriptomic study of urinary tract infections (UTIs) provides a powerful example of this framework in action. This study revealed marked inter-patient variability in microbial composition and transcriptional activity, even when the primary pathogen (E. coli) was the same [15]. By constructing patient-specific community metabolic models constrained by gene expression data, the researchers identified distinct virulence strategies and metabolic cross-feeding interactions that would be invisible with a census-based microbiome profile. Notably, the integration of gene expression data narrowed the variability in predicted metabolic fluxes and enhanced the biological relevance of the models, demonstrating the power of a function-first approach [15].

The expanded definition of the microbiome, which fully integrates host and environmental factors, represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology and host biology. It moves research from asking "Who is there?" to the more impactful questions of "What are they doing?" and "How does their activity influence the host and ecosystem?". Metatranscriptomics serves as a cornerstone technique for addressing these questions by providing a snapshot of the active community's functional state.

Future research will likely focus on the dynamic integration of multiple omics layers—metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics—to build a more complete, causal model of microbiome function. Furthermore, standardized reporting, as advocated by guidelines like STORMS, is crucial for ensuring reproducibility and comparability across studies [24]. As our molecular and computational toolkits continue to mature, the expanded microbiome definition will undoubtedly unlock novel diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions, particularly in managing complex conditions like multidrug-resistant infections, by targeting the functional core of the microbiome rather than just its constituents [15].

The Integrative Human Microbiome Project (iHMP or HMP2), launched in 2014 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), represents a paradigm shift in human microbiome research [27] [28]. As the second phase of the pioneering Human Microbiome Project (HMP), the iHMP was designed to move beyond static cataloging of microbial inhabitants and instead generate longitudinal, multi-omic datasets to elucidate the dynamic roles of microbes in health and disease states [29]. With an investment of $170 million, this ambitious initiative recognized that taxonomic composition alone often poorly predicts host phenotype, and that a more holistic understanding requires integration of microbial molecular function with host biological responses [27] [28].

The iHMP focused on three specific microbiome-associated conditions, employing complementary 'omics technologies including 16S rRNA gene profiling, whole metagenome shotgun sequencing, whole genome sequencing, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics/lipidomics, and immunoproteomics [28]. This comprehensive approach has created an unprecedented resource for the research community, providing protocols, data, and biospecimens that continue to fuel discovery in host-microbe interactions [27]. The project established that microbial communities and their hosts undergo coordinated changes in metabolism and immunity during different health states, offering new insights into the functional mechanisms underlying microbiome-associated diseases [27] [29].

iHMP Core Study Designs and Key Quantitative Findings

The iHMP consisted of three longitudinal sub-studies that investigated the dynamics of the human microbiome and host under conditions of pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and prediabetes. The key design elements and quantitative findings from these studies are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Overview and Key Findings from iHMP Longitudinal Studies

| Study Focus | Cohort Details & Sampling Strategy | Key Microbiome Findings | Host Response Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy & Preterm Birth (PTB) | 1,527 pregnant women followed; 12,039 samples from 597 pregnancies analyzed [27]. | Convergence toward Lactobacillus-dominated vaginas in 2nd trimester; PTB linked to Sneathia amnii, Prevotella, BVAB1, and TM7-H1 [27]. | Vaginal pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6) positively correlated with PTB-associated taxa [27]. |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Adults and children with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis followed from multiple medical centers [28]. | Longitudinal shifts in gut microbiome taxonomic and functional profiles associated with disease activity and flares [27]. | Host immune and metabolic responses were intricately coordinated with microbial community changes [27]. |

| Onset of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) | Patients at risk for T2D profiled to identify predictive molecular signatures [28]. | Marked shifts in the gut microbiome compared to healthy individuals, including specific metabolic pathways [28]. | Integrated data revealed molecules and signaling pathways involved in disease etiology [28]. |

The findings from these studies underscore the profound interconnectedness of host and microbiome biology. For instance, the pregnancy study revealed that the most predictive microbial signatures for preterm birth were detectable early in pregnancy (before 24 weeks), highlighting the potential for early risk assessment and intervention [27]. Furthermore, the iHMP established that the molecular interplay between host and microbiome provides a more accurate picture of health status than either dataset alone.

Metatranscriptomics: A Core Protocol for Active Community Analysis

Metatranscriptomics has emerged as a pivotal methodology for moving beyond microbial census data to understand the functionally active fraction of a microbial community. The standard workflow, as refined and applied in iHMP-related research, is detailed below.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sample Collection and RNA Preservation

- Critical Step: Collect sample (e.g., swab, stool, tissue) using kits that immediately stabilize RNA, as transcript levels can change rapidly post-sampling. Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [13].

- Considerations for Low Biomass Sites (e.g., skin): The risk of host RNA contamination is high. Use sampling methods designed to maximize microbial yield, such as rigorous swabbing or scraping [13].

RNA Extraction and mRNA Enrichment

- Procedure: Extract total RNA using commercial kits optimized for complex biological samples (e.g., Mo Bio PowerMicrobiome RNA Isolation Kit). The resulting total RNA will include microbial and host ribosomal RNA (rRNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), and other RNAs [15] [13].

- mRNA Enrichment: Since bacterial mRNA lacks poly-A tails, use probe-based methods to deplete abundant rRNA molecules (both host and microbial) rather than poly-A selection. Kits such as the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit are commonly employed [15] [13].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Procedure: Convert the enriched mRNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase. Then, prepare sequencing libraries with platform-specific adapters (e.g., Illumina). Amplify the library via PCR and validate quality using a Bioanalyzer [15].

- Sequencing: Perform high-depth sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) to generate sufficient coverage for quantifying low-abundance transcripts from complex communities [15].

Computational and Bioinformatic Analysis

Pre-processing and Quality Control

- Tool: Use FastQC for initial quality assessment.

- Pre-processing Steps: Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [15].

Taxonomic and Functional Assignment

- Alignment: Align quality-filtered reads to a customized reference database containing host and microbial genomes. This allows for the subtraction of residual host reads. Tools like KneadData are often used for this step.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Use tools such as MetaPhlAn for profiling the active microbial community [15].

- Functional Profiling: Align reads to a curated protein database (e.g., UniRef90) using HUMAnN2 to reconstruct and quantify the abundance of metabolic pathways [15].

Integration with Metabolic Modeling

- Procedure: Map metatranscriptomic data to Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), such as those in the AGORA2 resource, to predict community metabolic fluxes [15].

- Application: This integration allows researchers to move from gene expression lists to predictive models of microbial community physiology, as demonstrated in studies of urinary tract infections [15].

The following diagram illustrates the complete metatranscriptomics workflow, from sample to model.

Successfully executing a metatranscriptomic study requires a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools. The table below catalogs key resources for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Metatranscriptomics

| Category | Item/Resource | Specific Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | RNA Stabilization Solution (e.g., RNAlater) | Immediately preserves in vivo RNA expression profiles at point of sampling [13]. |

| Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit | Depletes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) from bacteria and host [15]. | |

| Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from rRNA-depleted RNA for transcriptome analysis [15]. | |

| Reference Databases | Human Microbiome Project (HMP) DACC | Provides curated, multi-omic reference datasets from healthy and diseased cohorts for comparison [27] [29]. |

| Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) | Annotates expressed virulence genes from pathogens like UPEC, linking activity to disease mechanism [15]. | |

| AGORA2 Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | A resource of 7,203 GEMs used to predict community metabolic fluxes from transcriptomic data [15]. | |

| Computational Tools | HUMAnN2 | Quantifies the abundance of microbial metabolic pathways and gene families from metatranscriptomic reads [15]. |

| MetaPhlAn | Provides precise taxonomic profiling of microbial communities from sequencing data [15]. | |

| BacArena | A modeling framework used to simulate and predict metabolic interactions in microbial communities [15]. |

Signaling Pathways and Host-Microbiome Interactions Elucidated by iHMP

The iHMP's multi-omic approach has been instrumental in uncovering specific host signaling pathways that are modulated by the microbiome. Two key areas of discovery are in inflammatory bowel disease and preterm birth.

In the context of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), the iHMP consortium revealed dynamic interactions between gut microbial metabolites and the host immune system. A primary finding involves the role of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber. These metabolites serve as signaling molecules and energy sources for colonocytes, influencing the maintenance of gut barrier integrity and regulatory T-cell function. During disease flares, the iHMP observed a depletion of SCFA-producing bacteria and a corresponding shift in host metabolic and inflammatory pathways [27].

For Pregnancy and Preterm Birth (PTB), the MOMS-PI study identified that a dysbiotic vaginal microbiome, characterized by a lower abundance of Lactobacillus crispatus and higher abundance of taxa like Sneathia amnii, is associated with an elevated pro-inflammatory state [27]. This state is marked by increased levels of vaginal cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6. The data suggest a signaling cascade where specific microbial communities trigger a localized immune response that can potentially disrupt the maternal-fetal interface, leading to spontaneous preterm labor [27]. The following diagram summarizes these host-microbe interaction pathways.

The Integrative HMP has successfully created a foundational multi-omic framework for investigating the microbiome as a dynamic interface with human health. By longitudinally profiling both host and microbiome molecules across different body sites and conditions, the iHMP has demonstrated that microbial community function is a critical determinant of phenotypic outcome, often transcending the importance of taxonomic composition alone [27]. The resources generated—including standardized protocols, vast public datasets, and analytical tools—have lowered the barrier for future research and set a new standard for integrative microbiome studies.

The application of metatranscriptomics, particularly when constrained with metabolic models as showcased in recent UTI [15] and skin microbiome [13] studies, provides a powerful path forward. This approach moves from correlation to mechanistic prediction, allowing researchers to model how microbial communities will function under different conditions. Future research will likely focus on further integrating these models with host biology to create a complete in silico representation of human superorganisms, ultimately accelerating the development of microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics, such as those that rely on metabolic reprogramming instead of traditional antibiotics [15].

From Lab to Clinic: Metatranscriptomics Workflows and Biomedical Applications

Metatranscriptomics has emerged as a powerful functional tool for analyzing active microbial communities by sequencing the collective RNA from all microorganisms in an environment. This approach moves beyond census-based microbial characterization to provide insights into the functional and metabolic capabilities of a microbiome at a specific time [9]. Unlike metagenomics, which reveals the potential functions encoded in DNA, metatranscriptomics identifies actively expressed genes, offering a dynamic view of microbial responses to their environment or host [30] [9]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for sampling, RNA extraction, and library preparation for metatranscriptomic studies, framed within the context of active microbial community analysis for drug development and clinical research.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and materials required for a successful metatranscriptomics workflow.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metatranscriptomics

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Buffer | Immediate stabilization of RNA post-sampling to prevent degradation. | RLT buffer with β-mercaptoethanol; crucial for field sampling [31]. |

| Microbiome RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation from complex microbial communities. | Commercial kits providing RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥5 are recommended [9]. |

| DNase Treatment Kits | Removal of genomic DNA contamination from RNA extracts. | Essential for accurate gene expression analysis [5]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Enrichment for messenger RNA (mRNA) by removing abundant ribosomal RNA. | Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome; vital for functional profiling [5] [9]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from mRNA. | Stranded RNA library prep kits compatible with rRNA-depleted RNA [9]. |

Sampling and Experimental Design

Sample Collection and Preservation

The initial sampling phase is critical for preserving the accurate snapshot of community gene expression.

- Water Samples: Filter a known volume (e.g., 500 mL) through 0.7 μm glass microfiber filters on-site to capture microbial biomass. Filtration should be completed within 30 minutes of collection to minimize RNA degradation [31].

- Human Tissues/Low-Biomass Samples: Use stringent contamination controls. Samples should be immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or placed in RNA stabilization reagents [5].

- Preservation: Filters or sample material should be placed in RNA stabilization buffers (e.g., RLT buffer with β-mercaptoethanol) immediately after collection, flash-frozen on dry ice, and transferred to -80°C storage until nucleic acid extraction [31].

Experimental Design Considerations

- Controls: Include filtration blanks (for water samples) or extraction blanks (for all sample types) to monitor for environmental and reagent contamination [31] [5].

- Replicates: Incorporate sufficient biological replicates to account for natural variability and ensure statistical robustness in downstream differential expression analysis.

- Metadata: Record comprehensive environmental (e.g., pH, temperature) or host (e.g., clinical metadata) data, as these are essential for interpreting transcriptional profiles.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

RNA Extraction

Extract total RNA using commercial microbiome RNA extraction kits designed to lyse diverse microbial cell types. The protocol generally follows these steps:

- Cell Lysis: Mechanical bead-beating is often necessary to ensure efficient lysis of robust microbial cells.

- Nucleic Acid Purification: Bind RNA to silica columns while removing contaminants and inhibitors.

- DNase Digestion: Perform on-column or in-solution DNase treatment to eliminate contaminating DNA [5].

- Elution: Elute purified RNA in nuclease-free water.

RNA Quality and Quantity Assessment

Assess the quality and quantity of the extracted RNA before proceeding to library preparation.

- Quantification: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate RNA concentration measurement.

- Quality Control: Evaluate RNA integrity using methods such as the RNA Integrity Number (RIN). A RIN greater than or equal to 5 is generally acceptable for metatranscriptomic studies [9].

Table 2: Key Quality Assessment Metrics and Thresholds

| Parameter | Recommended Method | Acceptance Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Concentration | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | Sample-dependent |

| RNA Integrity | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation (RIN) | RIN ≥ 5 [9] |

| DNA Contamination | PCR (e.g., 16S rRNA gene) | Not detectable |

Library Preparation for Sequencing

Ribosomal RNA Depletion

The high abundance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) can constitute over 90% of the total RNA in a sample. Depleting rRNA is essential to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) and maximize the informational yield of sequencing.

- Procedure: Use commercial kits (e.g., Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome) that are designed to remove both prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA [5]. This step is crucial for samples with a high background of host RNA, such as human tissues [5].

Library Construction and Sequencing

The rRNA-depleted RNA is used to construct a sequencing library.

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert the enriched mRNA to double-stranded cDNA using reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to the cDNA fragments. Barcodes (indices) are included to allow multiplexing of samples.

- Library Amplification: Perform limited-cycle PCR to amplify the final library.

- Library QC: Validate the library's size distribution and concentration using a Bioanalyzer and qPCR.

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on an appropriate Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq for high-depth requirements) to generate the necessary read depth for detecting microbial transcripts, especially in host-dominated samples [5].

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow from sample collection to data generation.

Downstream Bioinformatic Analysis

After sequencing, raw data undergoes a comprehensive computational workflow to derive biological insights. Key steps include:

- Pre-processing: Quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming, and removal of host and rRNA reads [5] [8].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Assignment of sequences to microbial taxa using classifiers like Kraken 2/Bracken, which shows high sensitivity in samples with low microbial content [5].

- Functional Profiling: Quantification of gene families and metabolic pathways using tools like HUMAnN 3 [5] [8].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identification of genes and pathways that are significantly altered between conditions, providing insights into microbial community responses to environmental stimuli or disease states [31] [8].

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Low RNA Yield: Common in low-biomass samples. Increase starting material volume if possible and ensure efficient cell lysis during extraction.

- High Host RNA Background: For human tissue samples, a high sequencing depth is required to adequately capture microbial transcripts. Optimization of rRNA depletion protocols is crucial [5].

- RNA Degradation: Ensure rapid processing and immediate use of RNase inhibitors during sampling. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles of extracted RNA.

- Bioinformatic Contamination: Always process and analyze negative controls in parallel with experimental samples to identify and subtract background signals.

Metatranscriptome (MetaT) sequencing is a critical tool for profiling the dynamic metabolic functions of complex microbiomes, providing real-time gene expression data of both host and microbial populations. This enables authentic quantification of the functional enzymatic output of the microbiome and its host, offering significant advantages over DNA-based approaches for understanding active community functions [32]. However, two major technical challenges severely compromise the effectiveness of metatranscriptomic analysis: the overwhelming abundance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcripts and the high proportion of host-derived RNA in many sample types.

In typical microbiome samples, rRNA can constitute as much as 99% of all sequencing reads, dramatically reducing the coverage of messenger RNA (mRNA) and driving up sequencing costs [32]. Simultaneously, host RNA can represent over 99% of the genetic material in clinically relevant samples like respiratory secretions and blood, effectively drowning out the microbial signal [33] [34]. This application note details optimized protocols and strategic solutions for overcoming these critical bottlenecks, enabling robust metatranscriptomic analysis across diverse research and clinical applications.

Table 1: Impact of Host RNA and rRNA on Sequencing Efficiency Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Untreated Host/rRNA Content | Effective Solution | Post-Treatment Microbial Reads | Key Improvement Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Cecal Content | High rRNA proportion | Mouse-optimized rRNA probes [32] | ~75% mRNA-rich reads [32] | ~15% increase in functional reads vs. human probes [32] |

| Clinical Sepsis Blood (0.5 mL) | High host RNA concentration | DRIB protocol with dual-species rRNA depletion [35] | 79,496-789,808 bacterial reads [35] | 63±7% of reads uniquely mapped to host or bacterial sequences [35] |

| Respiratory Samples (BAL) | 99.7% host reads [33] | HostZERO Mechanical+Chemical Lysis [33] [34] | 10-fold increase in final microbial reads [33] | 18.3% decrease in host DNA proportion [33] |

| Respiratory Samples (Sputum) | 99.2% host reads [33] | MolYsis commercial kit [33] | 100-fold increase in final microbial reads [33] | 69.6% decrease in host DNA proportion [33] |

| Rhizosphere Soil | High rRNA, humic acids | Optimized CTAB phenol-chloroform + Zymo-Seq RiboFree [36] | Successful transcript assembly | Effective rRNA removal, high-quality mRNA recovery [36] |

Table 2: Comparison of Host RNA Depletion Methods for Respiratory Samples

| Method | Mechanism | Best For | Efficiency (Reduction in Host DNA) | Impact on Microbial Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HostZERO (Zymo) | Chemical + Mechanical | BAL samples [33] | BAL: 18.3% decrease [33] | Significantly increases effective sequencing depth [33] |

| MolYsis (Molzym) | Selective lysis | Sputum samples [33] | Sputum: 69.6% decrease [33] | Increases species detection [33] |

| QIAamp (Qiagen) | Silica-membrane based | Nasal swabs [33] | Nasal: 75.4% decrease [33] | 13-fold increase in final reads for nasal [33] |

| Benzonase | Enzymatic degradation | Sputum (adapted protocol) [33] | Limited efficacy across sample types [33] | Moderate improvement [33] |

| lyPMA | Osmotic lysis + DNA cross-linking | Saliva with cryoprotectants [33] | Higher library prep failure rates [33] | Variable results [33] |

Optimized Protocols for Specific Applications

rRNA Depletion for Mouse Cecal Microbiome Studies

Background: Probes designed for human gut microbiomes (e.g., Ribo-Zero Plus) prove less effective and inconsistent when applied to mouse cecal samples, a common experimental system for microbiome studies [32].

Optimized Workflow:

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA from mouse cecal content using MagMAX mirVana Total RNA isolation kit [32].

- Probe Design Strategy: Employ taxonomic neutral probe design based solely on sequence abundance rather than taxonomic content [32].

- rRNA Depletion: Use Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome kit supplemented with mouse-specific probes (e.g., 5050 or 2025 probe sets from IDT oPools) [32].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare RNA-Seq libraries and sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 at 2 × 150 bp [32].

Key Innovation: The supplemental probes are carefully chosen to limit the number needed for effective depletion, reducing both cost and risk of introducing bias to MetaT analysis [32].

Performance: This approach provides ~75% mRNA-rich reads available for MetaT analysis, representing an additional ~15% of sequencing reads for functional data analysis compared to human-centric probes alone [32].

Figure 1: Optimized rRNA depletion workflow for mouse cecal samples

Dual RNA Isolation from Low-Volume Blood Samples (DRIB Protocol)

Background: Application of dual RNA-seq to sepsis research faces challenges including low bacterial burden in blood and limited sample volumes from vulnerable populations [35].

Optimized DRIB Protocol [35]:

- Sample Collection & Stabilization: Collect 0.5 mL whole blood into Li-Heparin tubes and immediately stabilize with 2.76× volumes (1.38 mL) of PAXgene Blood RNA solution. Incubate at RT for 2 hours to stabilize intracellular RNA and lyse host erythrocytes.

- Cell Pellet Recovery: Centrifuge at 3,200 g for 10 minutes. Carefully remove supernatant containing lysed erythrocytes. Wash remaining cells (leukocytes and bacteria) once with 1 mL nuclease-free water.

- Dual RNA Extraction: Resuspend cell pellet in 100 μL nuclease-free water. Add 1 mL TRI reagent and transfer to 2 mL bead-beating tubes with 0.1 mm zirconia/silica beads.

- Mechanical Lysis: Perform 3×1 minute cycles of bead-beating at 3,000 rpm with 1-minute breaks on ice between cycles.

- Phase Separation: Incubate at RT for 5 minutes. Add 200 μL chloroform, incubate 2 minutes at RT, then centrifuge at 12,000 g for 15 minutes.

- RNA Recovery: Recover aqueous RNA-containing phase and proceed with purification.

- Dual-Species rRNA Depletion: Implement dual-species rRNA depletion and RNA-seq.

Performance Validation: The DRIB protocol yields 2.10–6.91 μg of total RNA per clinical sample and generates 16.6–24.8 million filtered reads per sample, with 63±7% of reads uniquely mapped to host or bacterial sequences [35].

Universal rRNA Depletion for Complex Environmental Samples

Background: Rhizosphere soil presents unique challenges including copurification of inhibitory compounds like humic acids and difficult-to-lyse microbial communities [36].

Optimized Rhizosphere RNA Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Excise plant roots, place in PBS buffer, vortex to separate rhizosphere soil, centrifuge, and flash-freeze pellet at -80°C [36].

- CTAB Phenol-Chloroform Extraction:

- Homogenize 250 mg soil with silica beads in CTAB extraction buffer

- Add water-saturated phenol, Chloroform:Isoamyl alcohol (49:1), sodium phosphate buffer, and 2-Mercaptoethanol

- Centrifuge at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Perform successive organic extractions

- RNA Precipitation: Precipitate aqueous phase with PEG-NaCl solution, incubate on ice at 4°C for 20 minutes, then centrifuge at 20,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Purification: Purify crude RNA using Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kits with DNase I treatment.

- Library Construction: Use Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit with RiboFree Universal Depletion reagents to remove rRNA-cDNA hybrids [36].

Key Advantage: This optimized CTAB phenol-chloroform extraction protocol significantly improves RNA yield and quality from clay-rich soils, outperforming commercial kits [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for rRNA Depletion and Host RNA Removal

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome (Illumina) | rRNA depletion using RNase H | Gut microbiome samples [32] | Enzyme-based depletion with DNase treatment |

| Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA Library Kit | Universal rRNA depletion | Environmental samples, rhizosphere soil [36] | Removes prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit (Zymo) | Host DNA depletion | Respiratory samples (BAL) [33] | Chemical + mechanical lysis; effective for frozen samples |

| MolYsis Commercial Kit | Selective host cell lysis | Sputum samples [33] | Preserves gram-negative bacteria |

| PAXgene Blood RNA System | RNA stabilization | Blood samples for dual RNA-seq [35] | Stabilizes intracellular RNA at collection |

| NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit v2 | Ribosomal RNA removal | Respiratory samples with nanopore sequencing [34] | Compatible with third-generation sequencing |

| IDT oPools Oligonucleotides | Custom probe synthesis | Species-specific depletion [32] | Cost-effective custom probe manufacturing |

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Metatranscriptomics

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for metatranscriptomic analysis addressing both host RNA and rRNA challenges

Effective rRNA depletion and host RNA contamination control are foundational to successful metatranscriptomic studies. As demonstrated across diverse applications—from mouse cecal content to human clinical samples and environmental specimens—tailored approaches specific to sample type and research question are essential for obtaining meaningful functional data.

The protocols and methodologies detailed herein provide a framework for researchers to overcome the most significant technical barriers in metatranscriptomics. By implementing these optimized workflows and utilizing appropriate reagent solutions, researchers can significantly enhance the yield of microbial mRNA reads, thereby enabling more comprehensive analysis of active microbial community functions across diverse ecosystems and experimental systems.

Future advancements will likely focus on further refining probe design strategies, developing more efficient enzymatic depletion methods, and creating integrated workflows that seamlessly combine host RNA removal with rRNA depletion in a single streamlined process. As these technical hurdles continue to be addressed, metatranscriptomics will undoubtedly yield unprecedented insights into the dynamic functional interactions within microbial communities and their hosts.

Metatranscriptomics has emerged as a pivotal methodology for moving beyond the taxonomic census provided by metagenomics to characterize the functional activity of complex microbial communities. By sequencing the collective messenger RNA (mRNA) from an environmental sample, researchers can identify which genes are being actively expressed, providing insights into the metabolic processes and responses of a microbiome under specific conditions [37] [1]. This is particularly valuable in fields like drug development and human health, where understanding active microbial functions is as crucial as knowing which organisms are present. However, the analysis of metatranscriptomic data presents unique challenges, including the high background of host and ribosomal RNA, the instability of mRNA, and the sheer complexity of the computational analysis required [12] [1]. This application note outlines established and emerging bioinformatics pipelines designed to overcome these hurdles, enabling robust taxonomic and functional annotation to illuminate the active metatranscriptome.