Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Bacterial Identification: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is revolutionizing bacterial identification by enabling unbiased, culture-independent detection of pathogens directly from clinical samples.

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Bacterial Identification: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is revolutionizing bacterial identification by enabling unbiased, culture-independent detection of pathogens directly from clinical samples. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of mNGS technology and its transformative advantages over conventional culture methods. It details the end-to-end workflow from sample preparation to bioinformatic analysis, explores clinical applications across diverse infection types, and addresses key methodological challenges and optimization strategies. The content further evaluates performance through validation studies and comparative analyses with traditional diagnostics, highlighting mNGS's superior sensitivity for detecting fastidious, rare, and polymicrobial infections. Finally, it discusses the translational pathway for integrating mNGS into precision infectious disease management and antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Unlocking the Microbial World: Core Principles and Advantages of mNGS in Bacteriology

Defining Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) and its Hypothesis-Free Approach

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) is a high-throughput sequencing technology that enables the comprehensive and unbiased detection of microbial nucleic acids (DNA and/or RNA) directly from clinical, environmental, or other samples without the need for prior culturing [1]. This approach allows for the simultaneous identification and characterization of genomes from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites present in a sample, providing a powerful tool for understanding microbial community composition and diagnosing infections [2] [3]. The core principle of mNGS involves sequencing all nucleic acids in a given sample and then using bioinformatic analysis to assign these sequences to their reference genomes, thereby determining which microbes are present and in what relative proportions [2].

The most significant advantage of mNGS, and the characteristic that distinguishes it from traditional diagnostic methods, is its hypothesis-free nature [2] [4]. Unlike targeted methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture-based techniques that require prior knowledge or suspicion of a specific pathogen to guide testing, mNGS does not rely on pre-formulated hypotheses about the causative agent [2]. This unbiased approach is particularly valuable for detecting rare, novel, or unexpected pathogens, as well as polymicrobial infections, that might be missed by conventional, targeted assays [1].

The Hypothesis-Free Nature of mNGS

Conceptual Foundation of Unbiased Detection

The hypothesis-free approach of mNGS stems from its fundamental design as an untargeted, comprehensive screening tool. Traditional molecular diagnostics, such as PCR, rely on primers designed to amplify specific sequences from pre-identified targets [2]. Even so-called "broad-range" PCR methods that target conserved genetic regions (e.g., bacterial 16S rRNA or fungal ITS sequences) are not truly metagenomic because they still depend on specific primers and cannot simultaneously identify pathogens across different kingdoms of life with equal efficiency [2].

In contrast, mNGS employs a shotgun sequencing approach that randomly fragments all nucleic acids in a sample for sequencing, without targeting any specific organisms [2] [3]. This methodology allows for the detection of virtually all pathogens in a single test, making it particularly useful in diagnostically challenging scenarios where conventional tests have failed or when infections present with atypical symptoms [5] [1]. The capacity to identify novel or unexpected pathogens was notably demonstrated during the emergence of new infectious diseases, where mNGS played a crucial role in pathogen discovery [6].

Contrasting Targeted and Hypothesis-Free Approaches

Table 1: Comparison between targeted molecular methods and hypothesis-free mNGS

| Feature | Targeted Methods (e.g., PCR) | Hypothesis-Free mNGS |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement for Prior Knowledge | Requires suspicion of specific pathogen(s) | No prior knowledge needed |

| Detection Range | Limited to pre-specified targets | Comprehensive across biological kingdoms |

| Novel Pathogen Detection | Generally unable to detect | Capable of identifying novel organisms |

| Polymicrobial Infection Diagnosis | Challenging, may require multiple tests | Can simultaneously detect mixed infections |

| Primary Limitation | Narrow scope | Requires sophisticated bioinformatics |

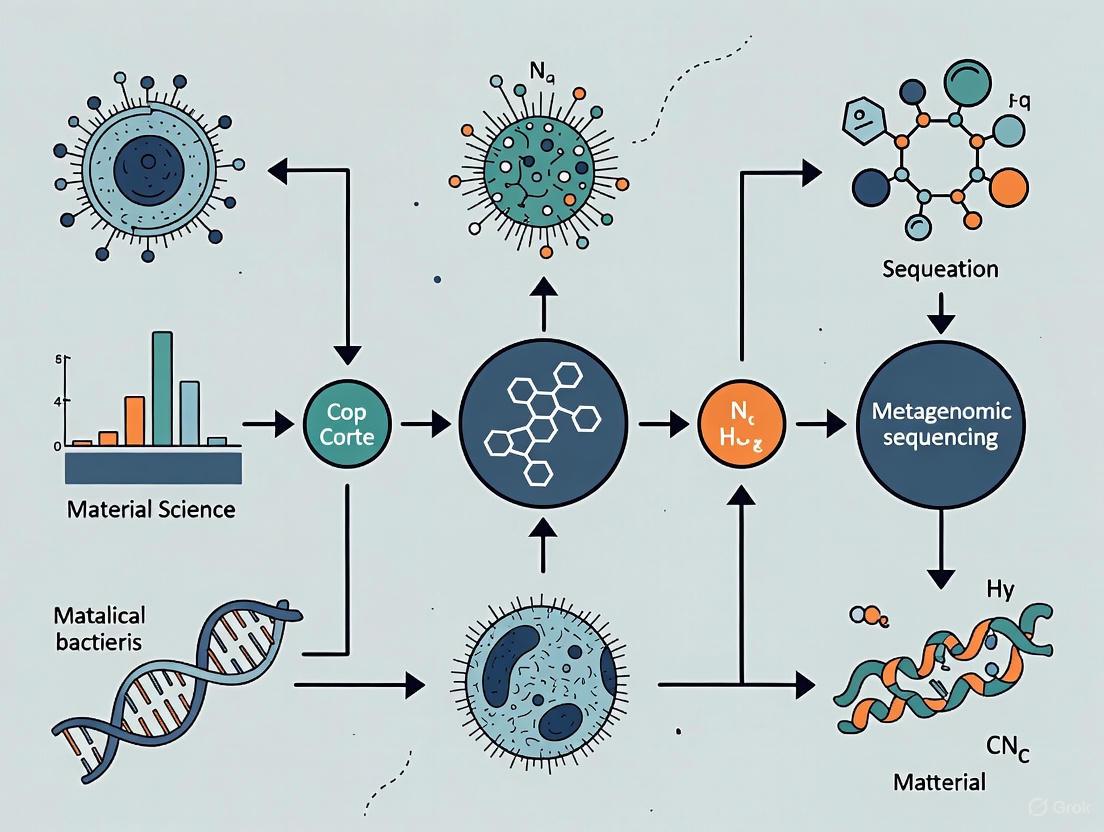

Diagram 1: Hypothesis-free versus targeted diagnostic approaches

Technical Workflow and Methodologies

Comprehensive mNGS Laboratory Workflow

The mNGS process consists of two major components: the wet lab procedures (laboratory testing) and the dry lab procedures (bioinformatic analysis) [1]. The wet lab component includes sample collection, nucleic acid extraction, library construction, and high-throughput sequencing, while the dry lab component encompasses quality control, removal of human sequences, alignment of sequences to microbial databases, and analysis of drug resistance or virulence genes [1].

Sample Collection and Processing: The initial step involves collecting appropriate samples, which for clinical applications may include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum, tissue, or other body fluids [1] [3]. Sample selection is critical, as some samples like blood and CSF have less background noise compared to others like stool or nasopharyngeal swabs that contain abundant commensal microorganisms [3]. Proper sample collection with minimal contamination is essential, especially given the analytical sensitivity of mNGS [2].

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Library Preparation: Total nucleic acid (both DNA and RNA) is extracted from the sample, often using commercial kits designed to maintain the representation of different microbial populations [3] [7]. For RNA viruses, RNA is reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA). The extracted nucleic acids are then processed for library preparation, which involves fragmenting the DNA/cDNA, attaching adapters, and sometimes amplifying the material to create a sequencing library [1] [3].

Host DNA Depletion: One significant challenge in mNGS, particularly for clinical samples, is that the vast majority of sequenced nucleic acids (often >95%) may originate from the host rather than pathogens [2] [5]. To increase the sensitivity for detecting microbial pathogens, various strategies for host DNA depletion may be employed, such as differential lysis, nuclease treatment, or CRISPR-Cas9-based approaches [3]. These methods aim to reduce host background while preserving pathogen nucleic acids.

Sequencing Platforms: The most commonly used platform for mNGS is Illumina, which utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis technology with high accuracy and relatively low error rates (as low as 0.1%) [1]. Other platforms include Thermo Fisher Ion Torrent (which uses semiconductor sequencing), BGISEQ-500, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (which enables real-time sequencing) [1]. Each platform has distinct advantages and limitations in terms of cost, throughput, read length, and error profiles.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The bioinformatic analysis of mNGS data is a complex, multi-step process that requires specialized expertise and computational resources [2] [3]:

- Quality Control and Trimming: Raw sequencing reads are first processed to remove low-quality sequences, adapter sequences, and duplicate reads [3].

- Host Sequence Subtraction: The remaining reads are aligned to the human reference genome (e.g., hg38) and matching sequences are computationally subtracted to reduce background noise and increase the proportion of microbial reads [3].

- Taxonomic Classification: The non-host reads are then aligned to comprehensive microbial genome databases using various classification tools (e.g., Kraken, BLAST) to identify the species present in the sample [3] [4].

- Pathogen Identification: The classified reads are analyzed to determine which microorganisms are present, often using thresholds based on read counts, genomic coverage, and comparison to negative controls [8].

- Advanced Characterization: Further analysis may include assembly of pathogen genomes, identification of antimicrobial resistance genes, and detection of virulence factors [3].

Diagram 2: mNGS workflow overview

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Successful implementation of mNGS requires careful selection of reagents and materials throughout the workflow. The table below outlines essential components and their functions in a typical mNGS experiment.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions and materials for mNGS workflows

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | TIANamp Micro DNA Kit, MagMAX Viral Isolation Kit, RNeasy PowerSoil Total RNA Kit | Isolation of total DNA and/or RNA from samples while maintaining representative abundance |

| Library Preparation | QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit | Conversion of extracted nucleic acids into sequencing-ready libraries; particularly important for low-biomass samples |

| Host Depletion | DNase I treatment, rRNA depletion kits, CRISPR-Cas9 based methods | Reduction of host (e.g., human) nucleic acids to enhance detection of low-abundance pathogens |

| Sequencing | Illumina NextSeq 550, MiSeq; Oxford Nanopore MinION | Platforms for high-throughput sequencing with different trade-offs in cost, throughput, and read length |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Kraken2, MetaPhlAn, MEGAHIT, Burrows-Wheeler Alignment, BLAST | Taxonomic classification, sequence alignment, de novo assembly, and database searching |

| Reference Databases | FDA-ARGOS, NCBI RefSeq, CARD (antibiotic resistance), VFDB (virulence factors) | Curated genomic databases for accurate taxonomic assignment and functional characterization |

Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions

Key Applications in Infectious Disease Research

The hypothesis-free nature of mNGS makes it particularly valuable in various clinical and research scenarios:

- Diagnosis of Neurological Infections: mNGS of cerebrospinal fluid has proven effective in identifying causes of meningitis and encephalitis, especially when conventional testing is negative or unavailable [2] [6].

- Respiratory Infections: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and sputum analyzed by mNGS can detect complex communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi in patients with pneumonia, particularly in immunocompromised individuals where mixed infections are common [8].

- Detection of Uncultivable or Fastidious Pathogens: mNGS can identify microorganisms that cannot be cultured using standard methods, including some bacteria, viruses, and fungi [1].

- Antimicrobial Resistance Characterization: mNGS can detect resistance genes directly from clinical samples, providing insights into the resistome of infectious agents [5] [3].

- Outbreak Investigation: The ability to generate whole or partial genomes enables tracking of transmission pathways and infection control surveillance [2].

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite its powerful capabilities, mNGS faces several significant challenges that limit its widespread clinical adoption:

- Distinguishing Pathogens from Contaminants: One of the most difficult aspects of mNGS interpretation is differentiating true pathogens from environmental contaminants or colonizing organisms [2]. This requires careful analysis and correlation with clinical findings.

- High Cost and Resource Requirements: mNGS remains expensive compared to conventional diagnostics and requires specialized equipment, reagents, and bioinformatics expertise [2] [1].

- Bioinformatic Complexity: The analysis of mNGS data demands substantial computational resources and specialized expertise that may not be available in routine clinical laboratories [2] [3].

- Regulatory Hurdles: As of the time of writing, there are no FDA-cleared or approved mNGS tests specifically for microbial identification, although CLIA-certified laboratories may offer such testing [2].

- Database Limitations: The accuracy of mNGS is highly dependent on the completeness and quality of reference databases, which may have gaps for rare or novel organisms [2].

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The field of mNGS continues to evolve rapidly with several promising developments:

- Targeted Metagenomics (tNGS): This approach uses multiplex PCR with primers targeting common pathogens before sequencing, increasing sensitivity for specific targets while reducing cost [8]. One study reported a higher coincidence rate with clinical diagnoses for tNGS (81.4%) compared to untargeted mNGS (40.0%) for respiratory infections [8].

- AI-Assisted Bioinformatics: Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are being integrated into mNGS analysis to improve sensitivity, specificity, and interpretation [4]. These systems can help distinguish pathogens from contaminants and identify novel organisms.

- Portable Sequencing Technologies: Platforms such as Oxford Nanopore's MinION enable real-time, field-deployable sequencing that can reduce turnaround times [5] [3].

- Genome-Resolved Metagenomics: Advanced computational methods now allow reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) directly from sequencing data, enabling more detailed characterization of microbial communities [9].

- Standardization Efforts: Professional organizations are developing guidelines and recommendations for implementing mNGS in clinical laboratories to improve reproducibility and reliability [7].

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing represents a transformative approach in microbial identification and infectious disease diagnosis through its hypothesis-free, comprehensive analysis of nucleic acids in clinical and environmental samples. Unlike targeted methods that require prior knowledge of suspected pathogens, mNGS simultaneously detects bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites across all kingdoms of life without bias. While challenges remain in interpretation, cost, and standardization, ongoing innovations in wet lab methodologies, bioinformatics, and artificial intelligence are steadily addressing these limitations. As the technology continues to evolve and become more accessible, mNGS is poised to play an increasingly central role in clinical microbiology, outbreak investigation, and microbial research, ultimately enhancing our ability to diagnose and understand complex infectious diseases.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a transformative, hypothesis-free tool in clinical microbiology and infectious disease diagnostics, enabling the simultaneous detection of a broad spectrum of pathogens—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—directly from clinical specimens [10]. Unlike traditional culture-based methods and targeted molecular assays that require prior knowledge of the suspected pathogen, mNGS sequences all nucleic acids present in a sample, allowing for the identification of novel, fastidious, and polymicrobial infections [10] [11]. This capability is particularly valuable for diagnosing complex cases in immunocompromised patients, sepsis, and culture-negative infections where conventional methods often fail [10] [12]. The core principle of mNGS involves the comprehensive sequencing of all microbial DNA and/or RNA in a sample, followed by sophisticated bioinformatic analysis to map the sequences to their respective genomes [13].

The application of mNGS extends beyond human medicine into agricultural sciences, where it is employed for detecting fungal plant pathogens and ensuring crop health, demonstrating its versatility across fields [11]. Despite its powerful capabilities, mNGS is best viewed as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for traditional diagnostics, enhancing diagnostic accuracy when integrated with culture, PCR, and serological assays [10]. This in-depth technical guide details the core mNGS workflow, from sample collection to sequencing and data analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing this technology in bacterial identification research.

Wet Lab Workflow: From Sample to Library

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

The first critical step in the mNGS workflow is the collection of appropriate samples and the subsequent extraction of nucleic acids. Suitable specimens vary widely depending on the application and can include bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), tissue samples, and pleural effusion [10] [14] [12]. For latent pathogen detection in plants, samples should be taken from highly infected, living plants where infection symptoms are most evident [11]. Proper handling is paramount; samples should be transported cold (at 4°C) and stabilized promptly to prevent contamination and DNA degradation, which could compromise the sensitivity of the metagenomic analysis [11].

Nucleic acid extraction can be performed using commercial kits or standard manual procedures, though kits are recommended to minimize the risk of environmental contamination [11]. The extracted nucleic acids constitute a mixture of DNA from multiple species, referred to as mix-DNA, or as environmental DNA (eDNA) when collected from environmental samples [11]. A major challenge in this step, particularly from clinical samples, is the high abundance of host-derived nucleic acids, which can obscure microbial signals. To improve the detection of microbial content, especially in low-biomass specimens, host DNA depletion methods are often employed [10] [15]. For example, a protocol optimized for respiratory samples may use a combination of Sputasol, saponin, and DNase treatment to reduce host background [15].

Table 1: Common Sample Types and Processing Considerations for mNGS

| Sample Type | Recommended Volume | Key Processing Considerations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | ≥ 5 mL [14] | Host depletion critical; high human DNA content | Lower respiratory tract infections, pneumonia [14] [12] |

| Blood | ≥ 250 µl [15] | Lower microbial biomass; requires sensitive detection | Sepsis, systemic infections [10] |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Variable | >99% of reads may be host-derived; sterile fluid | Meningitis, encephalitis [10] [16] |

| Tissue | Variable | Homogenization required; potential for high host DNA | Localized infections, pathogen discovery [12] |

| Sputum/Endotracheal Aspirates | ≥ 250 µl [15] | Requires digestion (e.g., with Sputasol) | Pulmonary infections [15] |

Library Preparation

Library preparation is the process that makes the extracted nucleic acid mixture compatible with sequencing platforms while preserving the diversity of DNA sequences present [11]. The specific methods can differ based on the sequencing technology and the target pathogens.

For bacterial and fungal detection from DNA extracts, the process often involves tagmentation (fragmentation and adapter ligation) using kits like the Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit (SQK-RPB114.24) [15]. This is typically followed by PCR amplification to incorporate full adapters and sample-specific barcodes, enabling the multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run [15].

For projects aiming to detect viruses or RNA pathogens, an initial reverse transcription (RT) step is necessary to convert RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA). One optimized method uses a "shotgun approach" with 9N random primers for reverse transcription, followed by PCR amplification to generate sequencing-ready libraries from both DNA and RNA pathogens [15].

The entire library preparation process, from tagmentation/RT to a ready-to-sequence library, can be completed in approximately 5-6 hours for a batch of 24 samples using streamlined protocols [15]. Automation is becoming a key driver of clinical NGS adoption, with integrated systems that combine nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, and sequencing into streamlined workflows capable of delivering same-day results [10].

Sequencing Platforms and Data Generation

Following library preparation, the next step is high-throughput sequencing. Several platforms are available, each with distinct characteristics suitable for different research needs.

Short-read sequencing technologies, such as those offered by Illumina (e.g., NextSeq 500, NovaSeq 6000), are widely used in mNGS due to their high accuracy and throughput [16] [14]. These systems generate massive amounts of data, with output ranging from 1.3 billion to 20 billion reads per run, and read lengths typically up to 300 base pairs [16]. This makes them ideal for detecting a wide array of pathogens with high sensitivity.

Long-read sequencing platforms, notably from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT; e.g., MinION, GridION) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), offer the advantage of generating much longer reads—spanning thousands of bases [10]. The portability of devices like the MinION is particularly beneficial for point-of-care diagnostics and real-time surveillance in field settings or resource-limited environments [10] [15]. Long reads facilitate the resolution of complex genomic regions, detection of structural variants, and complete reconstruction of plasmids and viral genomes [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms

| Sequencing Platform | Maximum Read Length | Maximum Data Output per Run | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina iSeq 100 | 2 x 150 bp [16] | 1.2 Gb / 4 million reads [16] | Low-cost, compact system |

| Illumina MiSeq | 2 x 300 bp [16] | 15 Gb / 25 million reads [16] | Mid-range output, versatile |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 | 2 x 150 bp [16] | 3000 Gb / 20 billion reads [16] | Ultra-high throughput for large studies |

| Oxford Nanopore MinION/GridION | Thousands of bases (long-read) [10] | Dependent on flow cell and run time | Real-time, portable sequencing; long reads [10] [15] |

The following diagram illustrates the complete mNGS workflow, integrating both short-read and long-read paths from sample to diagnosis:

Bioinformatics Analysis and Quality Control

Primary Data Processing and Quality Control

Once sequencing is complete, the generated raw data must undergo rigorous bioinformatic analysis. The initial step is quality control (QC) to assess the quality of the sequencing data. This involves evaluating several key metrics [16]:

- Input Reads: Checking the total number of reads helps identify samples with insufficient data.

- Reads Passing QC: A high percentage of reads passing QC filtering indicates good quality data. The CZ ID pipeline, for example, removes reads with >15 uncalled bases (N's) and bases with Phred quality scores <17 (corresponding to >98% base call accuracy) [16].

- Insert Length: The length of the nucleotide sequence between adapters should be as expected; shorter lengths may indicate sample degradation.

- Host/Human Reads: The percentage of reads removed as host sequences varies by sample type (e.g., >99% in sterile CSF, lower in stool) [16].

- Read Duplication Levels: High duplication, measured by the Duplicate Compression Ratio (DCR), can indicate low library diversity or PCR amplification bias [16].

Table 3: Key Quality Control Metrics in mNGS Data Analysis

| QC Metric | Interpretation | Tool/Method Example |

|---|---|---|

| Phred Quality Score | Base call accuracy; Q20 = 99% accuracy, Q30 = 99.9% accuracy [16] | FastQC, CZ ID pipeline |

| Host Read Percentage | Varies by sample type; high in sterile sites (CSF), low in high-microbial biomass (stool) [16] | Alignment to host genome (e.g., hg19) [14] |

| Duplicate Compression Ratio (DCR) | Ratio of total to unique sequences; high DCR indicates over-amplification or low complexity [16] | CZ ID pipeline |

| Spike-in Control Recovery (e.g., ERCC) | Assesses sequencing depth and potential bias; under-recovery suggests need for more sequencing [16] | Alignment to control sequences |

Microbial Identification and Contamination Management

After QC, non-host reads are aligned to comprehensive microbial databases for taxonomic classification. Commonly used tools include Kraken2 for rapid classification and Bowtie2/BLAST for validation [14]. A critical aspect of mNGS analysis is distinguishing true pathogens from background contamination introduced during sampling or laboratory processing.

The recommended strategy is to include negative control samples in every run. These controls are used to create a background model, which enables the calculation of a Z-score for each detected taxon in a clinical sample. The Z-score is computed as follows, where "rPM" is reads per million [16]:

Z = (rPM in sample - Mean rPM in negative controls) / Standard Deviation of rPM in negative controls

Taxa present at higher abundance in the sample than in the negative controls will have a Z-score > 1. If a taxon is absent from the negative controls, the Z-score is set to 100 [16]. This Z-score is then used to calculate an aggregate score, an empirical heuristic that ranks microbial matches by combining relative abundance and Z-score information at both the species and genus levels, helping to prioritize likely pathogens over contaminants [16].

The final interpretation must be done in the context of clinical data, as the mere presence of microbial DNA does not automatically establish pathogenicity. For plant pathogens, Koch's postulates may be followed, requiring the identification of pathogen nucleic acid in host tissues and mutation of virulence genes to confirm causality [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the mNGS workflow relies on a suite of specialized reagents and equipment. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the context of a typical mNGS experiment.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for mNGS Workflows

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Products/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates total DNA/RNA from complex samples; critical for yield and purity | MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit [15] |

| Host Depletion Reagents | Reduces host nucleic acids to improve microbial signal | Saponin solution, HL-SAN Triton Free DNase [15] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Fragments DNA, adds adapters, and incorporates barcodes for multiplexing | Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit (SQK-RPB114.24) [15] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts RNA to cDNA for detection of RNA viruses | Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase, RLB RT 9N primer [15] |

| PCR Master Mix | Amplifies library fragments for sequencing | LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix [15] |

| Magnetic Beads | Purifies and size-selects nucleic acids during library prep | Agencourt AMPure XP beads [15] |

| DNA Quantification Kit | Precisely measures library concentration before sequencing | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [15] |

| Sequencing Flow Cell | The surface where sequencing chemistry occurs | R10.4.1 flow cells (FLO-MIN114) for Nanopore [15] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | For quality control, taxonomic classification, and contamination assessment | Kraken2, Bowtie2, BLAST, CZ ID [16] [14] |

The mNGS workflow represents a powerful, comprehensive approach for pathogen detection and discovery. From meticulous sample collection and nucleic acid extraction through sophisticated library preparation, high-throughput sequencing, and rigorous bioinformatic analysis, each step is critical for generating reliable, clinically actionable data. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, becoming faster, more portable, and more cost-effective, and as bioinformatic tools become more standardized and accessible, the implementation of mNGS is poised to expand further. This will enhance our ability to diagnose complex infections, conduct real-time outbreak surveillance, and ultimately advance both clinical medicine and agricultural science through precise microbial identification. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this end-to-end workflow is essential for harnessing the full potential of metagenomic sequencing in the fight against infectious diseases.

For over a century, microbiological understanding of bacteria was constrained by a fundamental limitation: the necessity to culture organisms in artificial laboratory media. This culture-based paradigm created what is often termed the "great plate count anomaly"—the consistent observation that microscopic microbial counts exceed culturable counts by several orders of magnitude [17]. This discrepancy is particularly dramatic in aquatic environments, where plate counts and viable cells estimated by staining can differ by four to six orders of magnitude, and in soil, where only 0.1% to 1% of bacteria are readily culturable on common media [17]. The development of metagenomics, defined as the genomic analysis of microorganisms by direct extraction and cloning of DNA from an assemblage of microorganisms, has fundamentally addressed this limitation by enabling researchers to study microorganisms without the requirement for cultivation [17]. This approach provides a second tier of technical innovation that facilitates study of the physiology and ecology of environmental microorganisms, representing a transformative shift in microbiological investigation [17]. This technical guide examines the core advantages of metagenomic sequencing over traditional culture methods, with specific focus on its application in detecting unculturable, fastidious, and novel bacterial species.

Key Advantages of Metagenomic Sequencing Over Culture Methods

Comprehensive Access to Microbial Diversity

Metagenomic sequencing enables researchers to comprehensively sample all genes in all organisms present in a given complex sample, providing unprecedented access to microbial diversity [18]. This approach allows microbiologists to evaluate bacterial diversity and detect the abundance of microbes in various environments while simultaneously studying unculturable microorganisms that are otherwise difficult or impossible to analyze [18]. The application of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis amplified directly from environmental samples first revealed that as-yet-uncultured microorganisms represent the vast majority of organisms in most environments on Earth, leading to the discovery of vast new lineages of microbial life [17]. While 16S studies revolutionized our understanding of microbial community membership, they provided limited insight into the genetics, physiology, and biochemistry of the members—a limitation addressed by the more comprehensive approach of shotgun metagenomic sequencing [17].

Detection of Unculturable and Fastidious Organisms

A significant advantage of metagenomic sequencing is its capacity to identify pathogens in patients with prior antibiotic exposure, where traditional culture methods often fail [19]. Both fastidious organisms (those with specific nutritional requirements that cannot be met in standard culture) and viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms (those that are metabolically active but cannot proliferate in culture conditions) can be detected through metagenomic approaches. This capability is particularly valuable in clinical settings where antibiotic treatment often precedes diagnostic testing. Research has demonstrated that the positive rates of metagenomic testing of puncture fluid and tissue samples were significantly higher than those of culture in patients who had prior antibiotic use, with this difference being statistically significant (p = 0.000) [19]. This independence from prior antibiotic exposure represents a crucial diagnostic advantage over culture-based methods.

Discovery of Novel and Unexpected Pathogens

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) operates as a hypothesis-free detection method, enabling identification of novel, rare, and unexpected pathogens that would not be targeted by specific PCR assays or culture conditions [20] [10]. This unbiased approach has proven particularly valuable for detecting emerging pathogens and co-infections that conventional methods might miss. Clinical studies have demonstrated that mNGS provides more comprehensive information about pathogens compared to conventional diagnostic methods, with the capability to identify novel, rare, and unexpected pathogens that were previously undetectable [20]. This discovery potential extends beyond clinical medicine to environmental and industrial applications, where metagenomics has been used to identify novel enzymes and metabolic pathways from uncultured microbial communities [21].

Rapid Turnaround Time and Diagnostic Efficiency

In clinical contexts, metagenomic sequencing offers significantly faster pathogen identification compared to traditional culture methods, particularly for slow-growing organisms. While conventional culture typically requires 1-5 days (and longer for slow-growing microorganisms like fungi and mycobacteria), metagenomic workflows can generate results within hours [19]. Advanced workflows have demonstrated the capability to produce first automated reports after just 30 minutes of sequencing from a 7-hour end-to-end workflow, with sensitivity and specificity for bacterial detection reaching 90% and 100%, respectively, after just 2 hours of sequencing [22]. This rapid turnaround enables more timely targeted treatment, which is particularly crucial for critically ill patients and those with infections caused by fastidious or slow-growing organisms.

Table 1: Comparison of Diagnostic Performance Between Metagenomic Sequencing and Culture Methods

| Parameter | Metagenomic Sequencing | Conventional Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 58.01% (for all pathogens) [19] | 21.65% (for all pathogens) [19] |

| Specificity | 85.40% [19] | 99.27% [19] |

| Time to Result | 7-24 hours [22] [19] | 1-5 days (longer for slow-growing organisms) [19] |

| Effect of Prior Antibiotics | Minimal impact [19] | Significant reduction in yield [19] |

| Novel Pathogen Detection | Capable [20] [10] | Not capable |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | 92% sensitivity, 100% specificity for viruses after 2h sequencing [22] | Not applicable for virus detection |

Table 2: Applications of Metagenomic Sequencing Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | Diagnosis of pulmonary infections; simultaneous pathogen detection and malignancy screening via copy number variation analysis [14] | Higher human DNA background requires effective depletion methods [22] |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Diagnosis of central nervous system infections; demonstrated diagnostic yield up to 63% vs <30% for conventional approaches [10] | Low microbial biomass requires high sensitivity methods |

| Blood | Detection of bloodstream infections and sepsis pathogens [19] | Effective host DNA depletion critical for sensitivity |

| Tissue | Identification of pathogens in deep-seated infections [19] | Requires homogenization; less affected by antibiotics than culture |

| Environmental Samples | Exploration of novel enzymes from uncultured microbes [21]; environmental surveillance [23] | Extreme microbial diversity requires sufficient sequencing depth |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Processing and Host DNA Depletion

Effective host DNA depletion is crucial for enhancing sensitivity in metagenomic sequencing, particularly in samples with high human DNA background. A mechanical host-depletion method has been developed that allows simultaneous detection of RNA and DNA microorganisms. This protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge samples at 1200g for 10 minutes to pellet human cells [22].

- Bead-Beating Lysis: Transfer 500 µL of supernatant to bead-beating tubes containing 1.4 mm zirconium-silicate spheres and process for 3 minutes at 50 oscillations/second in a tissue lyser to mechanically lyse human cells [22].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Transfer 200 µL to a clean tube with 10 µl of HL-SAN nuclease (without buffer) and incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes at 1000 rpm to digest released human nucleic acids [22].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA and RNA from preserved intact microorganisms using automated systems with 200 μL input volume and 50 μl elution volume [22].

This method has been shown to decrease human DNA concentration by a median of eight Ct values while preserving a broad range of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and both DNA and RNA viruses [22].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The converted double-stranded DNA undergoes library preparation followed by sequencing:

- Library Preparation: DNA is prepared using a Rapid PCR barcoding kit with increased PCR cycles (30 cycles) to amplify microbial DNA [22].

- Sequencing: Samples are sequenced on platforms such as the GridION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) or Illumina NextSeq500, multiplexing 3-10 samples per flowcell [22] [14].

- Base Calling and Demultiplexing: Raw reads are demultiplexed and base-called using software like Guppy within MinKNOW, filtering reads with q-score <7 and length below minimum thresholds [22].

For Illumina-based approaches, libraries are typically sequenced to generate 10-20 million reads per sample to ensure sufficient coverage for pathogen detection [14].

Bioinformatic Analysis for Pathogen Detection

Bioinformatic processing is essential for accurate pathogen identification:

- Host Sequence Removal: The SNAP software is used to eliminate human sequences based on the human reference database (hg38) [19].

- Taxonomic Classification: Non-human reads are aligned to manually curated microbial databases using classifiers such as Kraken2 (confidence = 0.5) for rapid classification [14].

- Validation: Classified reads of interested microorganisms are realigned using Bowtie2 for validation, with inconsistent classifications further validated by BLAST alignment to nucleotide databases [14].

- Clinical Interpretation: Potential pathogens are selected based on clinical phenotype and reviewed by clinicians to determine clinical relevance, with species typically categorized as definite, probable, possible, or unlikely pathogens based on clinical, radiologic, or laboratory findings [14].

Workflow Visualization: From Sample to Pathogen Identification

Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metagenomic Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconium-Silicate Beads | Mechanical lysis of human cells while preserving intact microorganisms | 1.4 mm spheres for effective cell disruption [22] |

| HL-SAN Nuclease | Digestion of released human nucleic acids without buffer requirement | Digests DNA at roughly 10-fold higher efficiency than RNA [22] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA from bacteria, viruses, and fungi | MagNA Pure 24 System with total NA isolation kit [22] |

| Reverse Transcription Mix | Conversion of RNA to cDNA for inclusion in sequencing | LunaScript RT SuperMix Kit for cDNA synthesis [22] |

| Double-Strand DNA Synthesis Kit | Conversion of single-stranded DNA to double-stranded form for sequencing | Sequenase version 2.0 for dsDNA synthesis [22] |

| PCR Barcoding Kit | Library preparation with sample multiplexing capability | Rapid PCR barcoding kit with increased cycle number (30 cycles) [22] |

| Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput DNA sequencing | GridION (Oxford Nanopore), Illumina NextSeq500 [22] [14] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Taxonomic classification and pathogen identification | Kraken2, Bowtie2, BLAST for validation [14] |

Metagenomic sequencing represents a paradigm shift in microbial detection and characterization, offering significant advantages over traditional culture methods. Its capacity to identify unculturable, fastidious, and novel bacteria; its reduced susceptibility to prior antibiotic exposure; and its rapid turnaround time make it an indispensable tool for both clinical diagnostics and environmental microbiology. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, metagenomic approaches are poised to become standard practice for comprehensive microbial analysis, enabling researchers to explore the vast diversity of the microbial world that has remained largely inaccessible through culture-based methods alone. The integration of metagenomics with other omics technologies and the development of standardized protocols will further enhance our ability to detect and characterize previously elusive microorganisms, opening new frontiers in microbial ecology, infectious disease management, and bioprospecting.

The diagnostic landscape for infectious diseases is undergoing a revolutionary transformation driven by metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). This technological advancement represents a fundamental shift from hypothesis-dependent methods to comprehensive, unbiased pathogen detection, directly addressing critical limitations of conventional microbiological diagnostics. Traditional culture-based techniques and targeted molecular assays, while foundational, suffer from prolonged turnaround times, limited pathogen spectrum, and inherent difficulties in detecting polymicrobial infections [10] [24]. These limitations are particularly consequential in critically ill patients, where diagnostic delays lead to empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic use, escalating healthcare costs, and contributing to suboptimal outcomes, including mortality risks that increase significantly with each hour of delayed appropriate treatment [10] [24].

Metagenomic NGS enables the simultaneous, hypothesis-free detection of a vast array of pathogens—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—directly from clinical specimens [10]. By sequencing all nucleic acids present in a sample, mNGS transcends the culturing capabilities of fastidious, slow-growing, or non-culturable organisms and provides a powerful solution for analyzing complex polymicrobial infections [25]. This in-depth technical guide examines the core mechanisms through which mNGS overcomes traditional diagnostic barriers, with a specific focus on speed, expansive pathogen coverage, and sophisticated polymicrobial infection analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for its application in clinical and research settings.

The Technical Superiority of mNGS Over Conventional Diagnostics

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The advantages of mNGS over traditional diagnostic methods are substantial and consistently demonstrated across clinical studies. The table below summarizes a direct performance comparison from recent clinical investigations.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of mNGS vs. Traditional Culture Methods

| Diagnostic Parameter | mNGS Performance | Traditional Culture Performance | Clinical Context (Study) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 82.3% [26] - 95.35% [27] | 17.5% [26] - 81.08% [27] | Spinal infections [26], Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) [27] |

| Detection Rate | 77.6% [26] | 18.4% [26] | Spinal infections |

| Average Turnaround Time | 1.65 days [26] | 3.07 days [26] | Spinal infections |

| Polymicrobial Infection Detection | Capable of comprehensive profiling [10] [25] | Misses an estimated 30-40% of co-pathogens [25] | Diabetic foot infections, intra-abdominal infections [25] |

| Pathogen Coverage | Identified 36.36% of bacteria and 74.07% of fungi detected by cultures, plus additional pathogens [27] | Limited to cultivable organisms under specific conditions | LRTI in COVID-19 patients [27] |

Core Technical Workflow of Metagenomic Sequencing

The robust performance of mNGS stems from its culture-independent, comprehensive workflow. The entire process, from sample to report, integrates sophisticated wet-lab and computational steps to achieve unbiased pathogen detection.

Diagram 1: The End-to-End mNGS Workflow for Pathogen Detection. This comprehensive pipeline transforms a clinical sample into a actionable diagnostic report through integrated laboratory and computational processes.

Overcoming the Speed Barrier: Rapid Molecular Identification

Significant Reduction in Time-to-Result

The rapid turnaround time of mNGS is a critical advantage in acute clinical settings. A comparative study on spinal infections demonstrated that the average diagnosis time for mNGS was 1.65 days, significantly shorter (p < 0.001) than the 3.07 days required for standard bacterial culture [26]. This ~1.5-day reduction in time-to-result can dramatically alter patient management, enabling clinicians to transition from broad-spectrum empiric therapy to targeted antimicrobial treatment much earlier in the clinical course [10] [26].

This acceleration is largely attributable to the elimination of the prolonged incubation periods required for microbial growth in culture. The mNGS process, from sample processing to sequencing, can be completed within 24-48 hours, with emerging portable sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platforms pushing this further toward real-time, point-of-care diagnostics [10]. These platforms have been deployed in field settings for rapid diagnosis during outbreaks of Ebola, Zika, and SARS-CoV-2, underscoring their utility in decentralized and time-sensitive healthcare delivery [10].

Detailed Protocol for Rapid mNGS

Protocol: Rapid mNGS from Sample to Data (Adapted from Clinical Studies) [10] [26]

Sample Collection & Processing (2-4 hours):

- Collect appropriate clinical specimen (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid, blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, tissue). For sputum, assess quality using the Bartlett grading system (score ≤1) to minimize oropharyngeal contamination [27].

- Host DNA Depletion (Critical Step): Treat samples with commercial kits (e.g., benzonase) or differential lysis to reduce human background, significantly improving microbial signal, especially in low-biomass specimens [10].

- Nucleic Acid Co-Extraction: Extract total DNA and RNA simultaneously using validated kits (e.g., TIANamp Magnetic DNA Kit). For RNA viruses, include a reverse transcription step to generate cDNA [26].

Library Preparation & Sequencing (6-12 hours):

- Library Construction: Fragment nucleic acids and ligate with sequencing adapters using high-throughput preparation kits (e.g., KAPA HyperPrep Kit). This step can include indexing to multiplex multiple samples in a single run [26].

- Sequencing: Load libraries onto a next-generation sequencer (e.g., Illumina, Ion PGM System, or MinION). For the Dif seq platform, a target depth of 20 million reads is often used for the metagenomic workflow to ensure sufficient coverage [26].

Bioinformatic Analysis (2-6 hours):

- Quality Control & Host Removal: Remove low-quality reads, adapter contamination, and sequences aligning to the human reference genome (e.g., hs37d5) using tools like Bowtie2 [26].

- Pathogen Identification: Align non-human reads to comprehensive microbial genome databases (bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites) using specialized classifiers [26].

Achieving Unprecedented Breadth in Pathogen Coverage

Hypothesis-Free Detection of Diverse Pathogens

The "unbiased" nature of mNGS is its most transformative feature, allowing for the detection of nearly any pathogen from a single sample without prior suspicion. This broad coverage is effective against a wide spectrum of infectious agents, including bacteria (cultivable and fastidious), viruses, fungi, and parasites [10]. In lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI), particularly in COVID-19 patients, mNGS demonstrated a superior sensitivity of 95.35% compared to 81.08% for traditional cultures, while also identifying a broader range of pathogens, including 36.36% of bacteria and 74.07% of fungi that were also detected by cultures, plus additional pathogens missed by conventional methods [27].

This capability is invaluable for diagnosing infections with unknown etiology, where routine tests return negative, and for identifying rare or novel pathogens. The initial discovery of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself was a result of applying mNGS, highlighting its power in outbreak settings against novel threats [27]. Furthermore, mNGS can characterize antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, providing concurrent insights into potential treatment challenges. Studies on Mycobacterium tuberculosis have shown high concordance between whole-genome sequencing (WGS) by NGS and phenotypic susceptibility testing, supporting its use in predicting resistance to both first- and second-line therapies [10].

Key Methodologies for Comprehensive Pathogen Detection

Different NGS approaches offer varying levels of breadth and depth, allowing researchers to select the optimal strategy for their specific application.

Table 2: Key NGS Methodologies for Pathogen Identification and Characterization

| Sequencing Methodology | Primary Application & Strength | Typical Target/Approach | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Metagenomics (mNGS) | Unbiased detection of all pathogens in a sample; AMR gene profiling [10] | Sequencing all DNA in a sample; culture-independent | Higher host background; complex bioinformatics [10] |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Bacterial identification and diversity analysis; cost-effective [28] | Amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (bacteria-specific) | Limited to bacteria; cannot detect viruses or fungi [28] |

| ITS Amplicon Sequencing | Fungal identification and mycobiome analysis [28] | Amplification and sequencing of the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region | Limited to fungi; cannot detect bacteria or viruses [28] |

| Targeted NGS (tNGS) | Rapid, sensitive detection of pre-defined pathogens or resistance genes [10] [26] | Multiplex PCR or hybrid capture to enrich specific targets | Not unbiased; limited to panel content [10] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | High-resolution typing, outbreak tracking, comprehensive AMR detection [10] | Sequencing of the entire genome from a cultured isolate | Requires culture first; not direct from sample [10] |

The relationship between these methodologies and their application in a diagnostic pipeline can be visualized as a decision tree.

Diagram 2: Diagnostic Decision Tree for Selecting Appropriate NGS Methodologies. The choice between unbiased and targeted approaches depends on the clinical or research question and prior knowledge of suspected pathogens.

Deciphering the Complexity of Polymicrobial Infections

The Clinical Burden and Diagnostic Challenge

Polymicrobial infections (PMIs), defined as diseases caused by mixed infections of two or more microorganisms, represent a significant clinical burden, accounting for an estimated 20–50% of severe clinical infection cases globally [25]. In specific contexts like biofilm-associated device infections and diabetic foot infections (DFIs), this rate soars to 60–80% in hospitalized patients [25]. These infections increase the risk of mortality by 2- to 3-fold and extend hospital stays compared to their monomicrobial counterparts [24]. The increased mortality has been associated with inadequate and inappropriate antimicrobial treatments, which occur frequently because conventional diagnostics fail to paint a complete microbial picture [24].

Culture-based methods are particularly inadequate for PMIs due to differential inherent microbial fitness and co-culture conditions that may favor one species over another, prohibiting a comprehensive survey [24]. It is estimated that traditional cultures can miss up to 30–40% of co-pathogens in polymicrobial samples, leading to suboptimal therapy and worsened outcomes [25]. mNGS overcomes this by providing a culture-independent, high-resolution view of the entire microbial community.

mNGS Applications in Major Polymicrobial Infection Types

The ability of mNGS to profile complex microbial communities has proven critical in several infection types:

- Diabetic Foot Infections (DFIs): 60–80% are polymicrobial, involving complex mixtures of Gram-positive cocci (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus), Gram-negative bacilli (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and obligate anaerobes. mNGS identifies these consortia, which are directly linked to biofilm formation, AMR, and treatment failure rates up to 30% [25].

- Respiratory Infections: In ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), 40–70% of cases involve multidrug-resistant Gram-negative organisms like Acinetobacter baumannii and P. aeruginosa. PMIs in this context have a 15–25% higher ICU mortality. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mortality increased by over 50% owing to polymicrobial coinfections with bacteria and fungi [25].

- Intra-Abdominal Infections (IAIs): PMIs account for over 80% of IAIs following gastrointestinal perforation. mNGS can identify classic combinations like Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis, which synergistically promote greater virulence and abscess formation [25].

- Biofilm-Associated Infections: Infections from indwelling medical devices are fundamentally polymicrobial. Biofilm-embedded communities exhibit a 10- to 1000-fold reduction in antibiotic effectiveness. mNGS can identify the constituent members of these resilient communities, which frequently recur at rates exceeding 20% despite aggressive treatment [25].

Experimental Protocol for Polymicrobial Infection Analysis

Protocol: mNGS for Polymicrobial Community Profiling [10] [29]

Sample Collection & DNA Extraction:

- Collect tissue or fluid from the infection site, ensuring representative sampling. For biofilm infections, sonication of explanted devices can dislodge embedded communities for analysis [30].

- Extract total DNA as described in Section 3.2. Avoid methods that may bias against specific cell wall types (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria).

Shotgun Metagenomic Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Follow the library preparation steps for shotgun mNGS (Section 3.2) to ensure all genomic material is equally represented.

Bioinformatic Analysis for Community Profiling:

- Taxonomic Profiling: Use tools like Kraken (k-mer based) or MetaPhlAn (marker-gene based) to assign taxonomic labels to each sequencing read against a curated database (e.g., GreenGenes, NCBI) [29].

- Abundance Estimation: Generate a quantitative profile of the microbial community, calculating the relative abundance of each identified taxon.

- Data Visualization: Use tools like Krona to create interactive hierarchical pies of taxonomic abundances, or Pavian for in-depth analysis and comparison of community profiles between samples [29].

Advanced Analysis (Optional):

- Alpha Diversity: Calculate within-sample diversity metrics (e.g., Shannon Index) to compare microbial richness and evenness between patient groups (e.g., severe vs. non-severe COVID-19) [27].

- Beta Diversity: Calculate between-sample diversity metrics (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) to visualize overall community structural differences using PCoA plots [27].

- AMR Gene Screening: Align non-human reads to a database of antimicrobial resistance genes (e.g., CARD, MEGARes) to predict the functional resistance potential of the microbial community [10].

Successful implementation of mNGS in a research or clinical setting requires a suite of wet-lab and dry-lab reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for mNGS Workflows

| Category | Specific Tool / Kit / Platform | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | TIANamp Magnetic DNA Kit [26] | Co-extraction of DNA and RNA from clinical samples. |

| Host Depletion | Benzonase-based Kits [10] | Enzymatic degradation of human host nucleic acids to increase microbial sequencing depth. |

| Library Preparation | KAPA HyperPrep Kit [26] | Fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation for Illumina-compatible libraries. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (NextSeq 1000/2000) [28], Ion Torrent PGM [31], Oxford Nanopore [10] | High-throughput sequencing generating millions to billions of reads. |

| Bioinformatic Tools - Classification | Kraken (k-mer based) [29], MetaPhlAn (marker-based) [29], PathoScope [10] | Taxonomic assignment of sequencing reads to identify pathogens. |

| Bioinformatic Tools - Visualization | Krona [29], Pavian [29] | Interactive visualization of complex taxonomic profiling results. |

| Bioinformatic Tools - Database | NCBI RefSeq, GreenGenes [28] [29] | Curated genomic databases used as a reference for pathogen identification. |

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing represents a cornerstone technology in the new era of infectious disease diagnostics and research. By decisively overcoming the traditional limits of speed, pathogen coverage, and polymicrobial analysis, mNGS provides a powerful, unbiased lens through which to view the microbial world. The quantitative data and detailed protocols outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers and drug development professionals to integrate this transformative technology into their work. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward portability and lower costs, and as bioinformatic tools become more standardized and accessible, the integration of mNGS into routine clinical practice and clinical trials is poised to expand, ultimately enabling more precise, personalized, and effective management of infectious diseases.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is a transformative, non-targeted technique that enables the direct detection and characterization of microbial genomes from clinical samples without prior knowledge of the infectious agent [1]. This approach sequences the total nucleic acids extracted from diverse sample types, allowing for the simultaneous identification of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, thereby providing a comprehensive view of microbial communities that surpasses traditional culture-based methods [1]. The selection of an appropriate sequencing platform is a critical decision that directly influences the depth, accuracy, and scope of microbial detection in research on bacterial identification. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of three major sequencing technologies—Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and BGI platforms—focusing on their application within metagenomic sequencing workflows for bacterial research.

Core Sequencing Technologies

- Illumina: Utilizes Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) chemistry. This process involves fluorescently labeled, reversible-terminator nucleotides that are incorporated into growing DNA strands. As each nucleotide is added, a camera captures its fluorescent signal, enabling base determination [32] [33]. This technology is known for its high accuracy and output, making it a dominant platform in production-scale genomics [34] [33].

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT): Based on the measurement of electrical current changes. Single strands of DNA or RNA are passed through a protein nanopore. Each different nucleotide base disrupts the ionic current flowing through the pore in a characteristic way, and these changes are decoded in real-time to determine the sequence [35] [36]. A key advantage is its ability to sequence ultra-long reads and detect base modifications natively.

- BGI Platforms: Employs a proprietary method called Combinatorial Probe-Anchor Ligation (cPAL). This technology uses DNA nanoball (DNB) arrays, where DNA is amplified into nano-sized balls and deposited on a patterned array. Sequencing is then performed through repeated cycles of probe ligation and imaging [37]. This method is noted for its high accuracy, with a claimed error rate as low as 1 in 100,000 bases [37].

Technical Specifications at a Glance

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics for benchtop and production-scale sequencers from the leading platforms, providing a basis for direct comparison.

Table 1: Key Specifications of Benchtop Sequencing Systems

| Platform / Model | Max Output per Flow Cell | Max Read Length | Key Applications in Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq (Kit v3) | 13.2–15 Gb [32] | 2 × 300 bp [32] | Small whole-genome sequencing (microbe, virus), 16S metagenomic sequencing [34] |

| Illumina MiSeq (Kit v2) | 7.5–8.5 Gb [32] | 2 × 250 bp [32] | Targeted gene sequencing (amplicon-based), metagenomic profiling [34] |

| Oxford Nanopore MinION | Up to 30 Gb [34] | > 30 kb (ultra-long) [35] | Real-time pathogen detection, shotgun metagenomics, full-length 16S sequencing [38] |

Table 2: Key Specifications of Production-Scale Sequencing Systems

| Platform / Model | Max Output per Flow Cell | Max Read Length | Typical Run Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (S4 Flow Cell) | 2400–3000 Gb [33] | 2 × 150 bp [33] | ~44 hours [33] |

| Illumina NovaSeq X Plus | 8000 Gb [34] | 2 × 150 bp [34] | ~17–48 hours [34] |

| Oxford Nanopore PromethION | 540 Gb [34] | 2 × 300 bp [34] | ~8–44 hours [34] |

Detailed Workflows and Data Analysis

General mNGS Wet and Dry Lab Workflow

The process of metagenomic sequencing consists of two main parts: the wet lab (laboratory testing) and the dry lab (bioinformatic analysis) [1]. The wet lab phase includes sample collection, nucleic acid extraction, library construction, and high-throughput sequencing. The dry lab phase involves data quality control, removal of human host sequences, alignment of sequences to microbial databases, and analysis of drug resistance or virulence genes [1]. The general workflow is depicted below.

Oxford Nanopore-Specific Data Analysis

A distinct advantage of Oxford Nanopore technology is the ability to perform basecalling and analysis in real-time. The core of this process is the conversion of raw electrical signals into nucleotide sequences.

Basecalling Models: Oxford Nanopore provides several basecalling models optimized for different needs [36]:

- Fast Model: Designed to keep up with data generation on most devices; ideal for quick, real-time insights.

- High Accuracy (HAC) Model: Provides higher raw read accuracy than the Fast model; recommended for high-throughput variant analysis.

- Super Accurate (SUP) Model: The most accurate and computationally intensive model; recommended for de novo assembly and low-frequency variant analysis.

Furthermore, designated models are available for the direct detection of base modifications (e.g., 5mC, 5hmC for DNA and m6A for RNA) without additional experiments, a feature unique to nanopore sequencing [35] [36].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful metagenomic sequencing relies on a suite of specialized reagents and kits for sample and library preparation. The table below details key solutions used in typical workflows.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Sequencing

| Reagent / Kit Name | Platform | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit [38] | Oxford Nanopore | Enables quick library preparation and sample multiplexing for rapid pathogen identification. |

| Ultra-long Sequencing Kit (ULK) [35] | Oxford Nanopore | Facilitates the generation of ultra-long reads (>>30 kb), crucial for resolving complex genomic regions and complete genome assembly. |

| Assembly Polishing Kit (APK) [35] | Oxford Nanopore | Used in conjunction with ultra-long reads to achieve high-accuracy, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. |

| NovaSeq 6000 Reagent Kits (v1.5, S1-S4) [33] | Illumina | Production-scale sequencing reagents with patterned flow cell technology for high-throughput metagenomic studies. |

| MiSeq Reagent Kits (v2, v3) [32] | Illumina | Benchtop sequencing reagents offering flexibility in output and read length for smaller-scale microbial projects. |

| Agilent SureSelect / Roche NimbleGen [37] | Multiple | Target enrichment platforms used to isolate specific genomic regions of interest, such as the exome, from complex samples. |

Application in Pathogen Metagenomics: A Specific Workflow

Metagenomic sequencing is a key technique for identifying potential pathogens without prior knowledge of microbial sample composition, providing critical insights for outbreak surveillance [38]. Oxford Nanopore's streamlined workflow for respiratory samples exemplifies this application.

- Rapid Identification: The use of the Rapid PCR Barcoding Kit on a MinION or GridION allows for rapid sequencing and analysis, delivering data that can be critical for timely outbreak control [38].

- Comprehensive Detection: The ability to sequence any fragment length enables thorough characterization of mixed microbial samples, simultaneously identifying bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens [38].

- Overcoming "Dark" Genomes: Short-read technologies are estimated to miss about 8% of the human genome, which includes many disease-relevant repetitive regions. Nanopore technology has been shown to reduce these inaccessible areas by 81%, providing a more complete picture of the genomic landscape [35].

The choice between Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and BGI sequencing platforms for bacterial metagenomics depends heavily on the specific research goals. Illumina platforms offer high-throughput and base-level accuracy ideal for large-scale, quantitative microbial profiling. Oxford Nanopore provides real-time data, long reads that resolve complex regions, and direct epigenetic detection, which are advantageous for rapid pathogen identification and complete genome assembly. BGI's technology, with its cPAL chemistry and DNB arrays, presents an alternative with very high claimed accuracy for comprehensive variant detection. As these technologies continue to evolve, advances in bioinformatics, chemistry, and hardware will further consolidate mNGS as a pivotal, comprehensive tool for pathogen detection and characterization in modern research.

From Bench to Bedside: mNGS Workflow Optimization and Clinical Deployment

Metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized the study of microbial communities, enabling researchers to decipher the genetic material of entire ecosystems directly from environmental or clinical samples. For bacterial identification research, the fidelity of the final genomic data is profoundly dependent on the initial wet-lab procedures. This guide details three critical wet-lab steps—sample collection, host DNA depletion, and library preparation—framed within the context of metagenomic sequencing. The choices made during these phases are not merely procedural; they directly influence downstream outcomes, including the accuracy of taxonomic profiling, the ability to detect low-abundance pathogens, and the overall reliability and reproducibility of the research [39] [10]. The following sections provide an in-depth technical examination of these steps, summarizing key quantitative data for informed decision-making and outlining detailed protocols.

Sample Collection and Preservation

The foundation of any successful metagenomic study is the integrity of the initial sample. Inadequate collection or preservation can introduce biases that no downstream analysis can correct.

Core Principles

The primary goal during sample collection is to obtain a representative microbial community while minimizing any changes to its composition from the point of collection until nucleic acid extraction. Key considerations include:

- Immediate Stabilization: Microbial activities continue after sample collection. For many sample types, especially those with high microbial biomass, immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard. However, when freezing is not immediately possible, such as during field collection, the use of commercial stabilization solutions is critical. These solutions lyse cells and inhibit nuclease activity, preserving the nucleic acid profile at the moment of preservation [10].

- Avoiding Contamination: The use of sterile, DNA-free collection containers and reagents is paramount. This is particularly crucial for low-biomass samples (e.g., tissue biopsies, cerebrospinal fluid), where contaminating DNA from collection kits or the environment can constitute a significant portion of the sequenced material [10].

- Sample-Specific Protocols: The optimal method varies by sample type. For instance, swabs from mucosal surfaces may require different handling than fecal samples or water samples from environmental sources.

Experimental Protocol: Fecal Sample Collection for Gut Microbiome Studies

Materials:

- DNA/RNA-free collection tube with stabilizer (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield)

- Sterile spatula or swab

- Personal protective equipment (PPE)

- -80°C freezer or dry ice for immediate storage

Methodology:

- Using a sterile spatula, collect approximately 100-200 mg of fecal material.

- Immediately place the sample into the collection tube containing a DNA/RNA stabilizer solution. Ensure the sample is fully submerged.

- Vortex the tube vigorously for at least 30 seconds to ensure homogenization and complete lysis of cells upon contact with the stabilizer.

- Label the tube clearly and store at 4°C for short-term transport (up to 1 week) or at -80°C for long-term storage.

- Record all metadata, including time of collection, patient/donor identifier, and any clinical symptoms or dietary information, as this contextual data is essential for later interpretation.

Host DNA Depletion

In clinical metagenomics, where samples are often dominated by host DNA (e.g., human DNA in blood or tissue), depleting this host material is a critical step to increase the sensitivity for detecting bacterial pathogens.

Host DNA depletion techniques selectively remove or degrade host nucleic acids, thereby enriching the relative proportion of microbial DNA. The efficiency of depletion is a major factor in the success of sequencing low-biomass infections [10]. Common methods include:

- Enzymatic Digestion: Uses nucleases that are specific to mammalian cells (e.g., Benzonase) which digest DNA in the extracellular environment or in host cells that have been selectively lysed using mild detergents. The microbial cells, with their intact cell walls, are protected from digestion. After digestion, the nuclease is inactivated, and the microbial DNA is extracted.

- Probe-Based Capture: Involves designing biotinylated oligonucleotide probes that are complementary to highly conserved regions of the host genome (e.g., human rRNA genes). The probes are hybridized to the sample DNA, and host-probe complexes are removed using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. This method can achieve high levels of depletion but is more costly and complex.

The choice of method involves a trade-off between depletion efficiency, cost, and potential loss of some microbial taxa.

Performance Comparison of Depletion Methods

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the primary host DNA depletion methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Depletion Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Digestion | Selective lysis of host cells followed by nuclease digestion of exposed DNA. | 70-95% [10] | Cost-effective; relatively simple workflow; maintains microbial integrity. | Potential for incomplete lysis or digestion; may not be effective for all sample types. |

| Probe-Based Capture | Hybridization and magnetic bead removal of host DNA sequences. | 90-99.9% [10] | Very high depletion efficiency; can be tailored to specific hosts. | Higher cost; requires specialized probe sets; potential for co-depletion of microbes with similar sequences. |

Library Preparation for Metagenomic Sequencing

Library preparation is the process of converting the extracted DNA into a format compatible with high-throughput sequencing platforms. The chosen protocol can significantly impact data quality, including fragment length distribution, GC bias, and the recovery of endogenous microbial DNA [39].

Fundamentals of Library Construction

Most next-generation sequencing (NGS) library prep protocols share common steps: DNA fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and library amplification. However, specific adaptations are crucial for metagenomic applications, particularly when dealing with degraded DNA or low-input samples.

Comparison of Common Library Prep Methods

The two predominant approaches in metagenomics are double-stranded and single-stranded library methods. A systematic comparison is essential for selecting the appropriate protocol.

Table 2: Characteristics of Library Preparation Methods for Metagenomics

| Method | Principle | Ideal Fragment Size | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Stranded (DSL) [39] | Ends of double-stranded DNA molecules are repaired and ligated to double-stranded adapters. | >100 bp | Widely used; robust and cost-effective; shorter protocol duration. | Lower conversion efficiency of short, fragmented DNA; higher clonality [39]. |

| Single-Stranded (SSL) [39] | DNA is denatured into single strands before adapter ligation, enabling higher conversion of short fragments. | <100 bp | Superior for degraded/low-input samples; higher conversion efficiency; lower clonality [39]. | Historically more expensive and time-consuming; though newer methods (e.g., Santa Cruz Reaction) have addressed this [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Double-Stranded Library Preparation for Illumina

This is a generalized protocol based on common commercial kits (e.g., Illumina Nextera Flex).

Materials:

- Purified DNA (1-100 ng in volume)

- Tagment DNA Buffer

- Amplicon Tagment Mix

- Neutralize Tagment Buffer

- PCR Master Mix

- Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs)

- Magnetic beads (e.g., SPRIselect)

- Fresh 80% Ethanol

- Nuclease-free water

- Thermal cycler, magnetic stand, and microcentrifuge

Methodology:

- Tagmentation: Combine DNA, Tagment DNA Buffer, and Amplicon Tagment Mix in a PCR tube. Incubate in a thermal cycler at 55°C for 10-15 minutes. This simultaneously fragments and tags the DNA with adapter sequences.

- Neutralization: Add Neutralize Tagment Buffer to stop the tagmentation reaction. Mix thoroughly by pipetting.

- PCR Amplification: To the neutralized tagmentation reaction, add PCR Master Mix and a unique pair of Dual Index Primers. Perform PCR amplification with the following cycling conditions:

- 72°C for 3 minutes

- 95°C for 30 seconds

- 12-15 cycles of: 95°C for 10 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds

- 72°C for 5 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

- Library Clean-up: Add a calculated volume of magnetic beads to the PCR product to purify the final library. Incubate, separate on a magnetic stand, wash twice with 80% ethanol, and elute in nuclease-free water.

- Quality Control: Quantify the library using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) and assess the size distribution using a bioanalyzer or tape station. The library is now ready for sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their critical functions in the metagenomic wet-lab workflow.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Stabilization Solution | Preserves nucleic acid integrity at room temperature by inactivating nucleases. | Essential for field collections and clinical settings where immediate freezing is not feasible [10]. |

| Methylated DNA Depletion Kit | Selectively removes mammalian (host) DNA based on differential methylation patterns. | An alternative to probe-based methods; effectiveness depends on the sample type and host organism [10]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries without PCR amplification. | Avoids PCR bias and improves coverage uniformity, but requires higher input DNA [39]. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Size-selects and purifies nucleic acids based on binding to carboxylated beads in PEG buffer. | A versatile tool for clean-up and size selection post-fragmentation and post-amplification. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies library fragments with low error rates during PCR. | Critical for minimizing mutations during the limited-cycle amplification step of library prep. |

Workflow Visualization and Emerging Methods

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of the critical wet-lab steps discussed in this guide, from sample to sequencer.