Materials Science Essentials: A Guide to Fundamental Concepts and Biomedical Applications for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to core materials science concepts, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

Materials Science Essentials: A Guide to Fundamental Concepts and Biomedical Applications for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to core materials science concepts, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. It explores the fundamental structure-property-processing-performance paradigm, from atomic bonding to microstructure, and examines key material classes including biomaterials, polymers, and ceramics. The scope covers methodological applications in biomedicine, such as tissue engineering and drug delivery systems, alongside troubleshooting and optimization strategies for material selection and degradation. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of characterization techniques and validation frameworks to guide informed material selection for clinical applications, aiming to bridge the gap between materials science and pharmaceutical development.

What is Materials Science? Understanding the Core Principles from Atoms to Applications

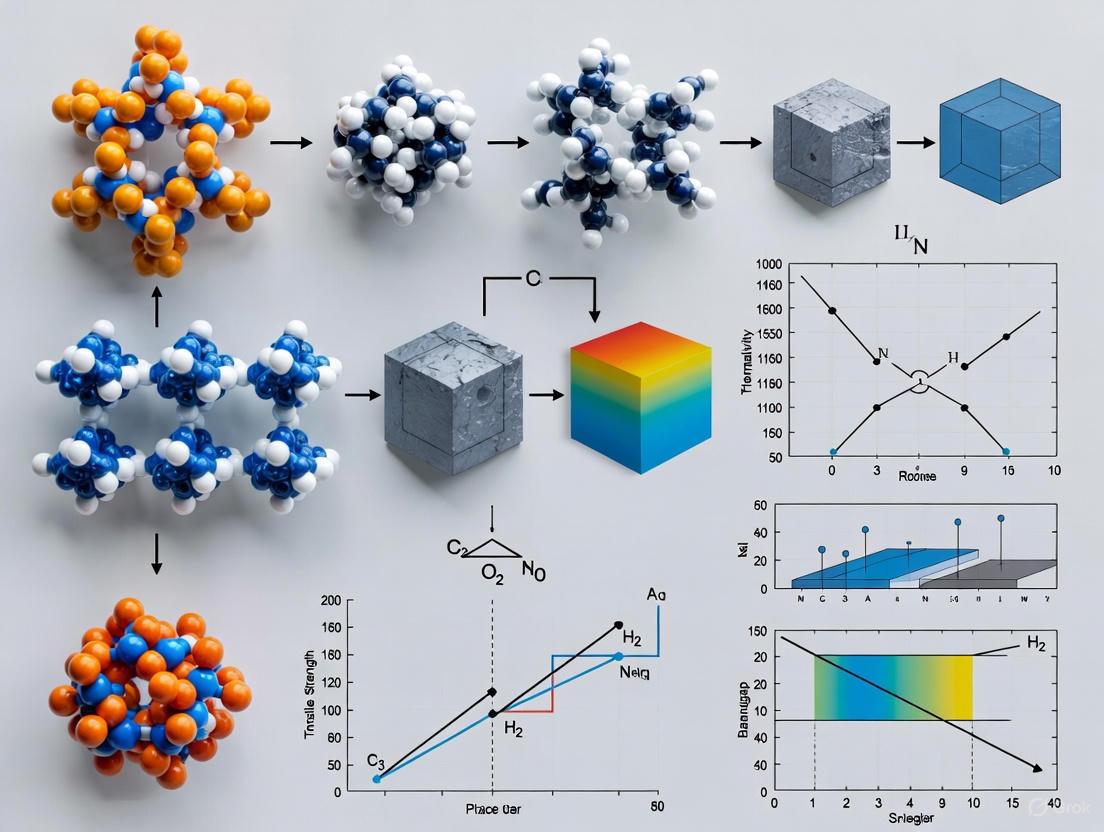

The Materials Science Paradigm, often visualized as a tetrahedron or a four-element cycle, provides a fundamental framework for understanding and engineering materials. This paradigm establishes that the performance of a material in any application is determined by its properties, which originate from its internal structure, which is, in turn, established through processing [1]. This in-depth technical guide explores each element of this interconnected cycle, detailing the quantitative relationships, experimental methodologies, and modern computational tools that enable researchers to navigate this framework for the rational design of new materials, including those with applications in advanced drug delivery systems [2] [3].

The Foundations of the Materials Science Paradigm

The Materials Science Tetrahedron is more than a simple diagram; it is the philosophical core of the discipline. It defines the scope of materials science and engineering by emphasizing four interdependent aspects: processing, structure, properties, and performance [1]. The relationship between these elements is not linear but highly iterative. For educational and accreditation purposes, particularly under bodies like ABET (the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology), proficiency in understanding and applying these relationships is a key standard for materials science graduates [1].

The paradigm can be visualized in several ways, each emphasizing a different thought process:

- The Tetrahedron: This model positions processing, structure, properties, and performance at each vertex, with bidirectional relationships between all points, highlighting their complete interdependence [1].

- The Sequential Chain: A simplified but effective model shows a direct sequence: Processing → Structure → Properties → Performance. This is particularly useful for reverse-engineering materials, where a desired performance dictates the required properties, which then inform the necessary structure and processing route [1].

- The Science/Engineering Focus: A common, though not absolute, distinction suggests that materials scientists often focus on the structure-property relationship, seeking to understand why materials behave as they do. In contrast, materials engineers often focus on the processing-performance relationship, optimizing how to make and use materials for specific applications [2] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core paradigm, highlighting these critical relationships and the central role of characterization.

Deconstructing the Paradigm: Core Concepts and Quantitative Relationships

Processing: Imparting Structure

Processing encompasses every operation used to create or change a material to make it more useful [1]. It is the means by which a material's internal architecture is defined.

- Primary Processing: These are the initial steps to create a usable material from raw sources. For metals like steel, this includes mining iron ore, chemical separation, purification, and alloying with carbon to create a bulk "final" material like a steel ingot [1].

- Secondary Processing: These steps shape and treat the primary material into a final component. Examples include forging, rolling, heat treatment (e.g., quenching and tempering), coating, and machining. In polymers, secondary processing includes injection molding and extrusion [1] [4].

Table 1: Common Material Processing Techniques and Their Effects

| Material Class | Processing Technique | Key Parameter Controls | Primary Structural Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metals & Alloys | Heat Treatment (Quenching) | Cooling rate, Quenchant medium | Controls phase distribution, grain size, and hardness [1]. |

| Ceramics | Sintering | Temperature, Pressure, Time | Reduces porosity, increases density and strength [2]. |

| Polymers | Injection Molding | Melt temperature, Injection pressure, Cooling rate | Defines molecular orientation, crystallinity, and final shape [4]. |

| Semiconductors | Doping | Dopant species concentration (e.g., Boron, Phosphorus), Diffusion temperature | Introduces charge carriers (electrons/holes), tuning electrical conductivity [2] [4]. |

Structure: The Material's Architecture

Structure refers to a material's arrangement across multiple length scales, from the atomic to the macroscopic. The profound influence of structure is exemplified by diamond and graphite, both pure carbon but with vastly different properties due to their atomic bonding and arrangement [1].

- Atomic Structure: This includes the type of atomic bonding (metallic, covalent, ionic) and the crystal structure (e.g., face-centered cubic, body-centered cubic, hexagonal close-packed). Defects at this scale, such as vacancies or interstitial atoms, are critical; for instance, doping semiconductors introduces intentional impurities that drastically alter electronic properties [2] [1].

- Microstructure: This scale involves the arrangement of grains (small crystals) in a polycrystalline material, the distribution of different phases (e.g., precipitates in an alloy matrix), and the presence of pores. Microstructure is typically observed using microscopy techniques [1].

- Macrostructure: This includes features visible to the naked eye, such as surface roughness, large pores, and layered architectures in composite materials [1].

Properties: The Measurable Response

Properties are a material's measurable response to specific external stimuli. They are the direct consequence of the material's structure.

- Mechanical Properties: Include strength, hardness, ductility, and toughness. These are often determined by the bonding type and microstructural features like grain boundaries and precipitates [2].

- Functional Properties: Include electrical conductivity (metals), semiconductor (tunable conductivity), piezoelectricity (ceramics that generate charge under mechanical stress), and biocompatibility (for biomaterials) [2].

The relationship between structure and properties is the domain of quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) modeling, which uses mathematical and statistical methods to correlate structural descriptors with property data [5].

Table 2: Key Material Properties and Their Structural Determinants

| Property Category | Specific Property | Measurement Standard | Governing Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Yield Strength | ASTM E8 / ISO 6892-1 | Bond strength, Dislocation density, Grain size (Hall-Petch relationship) [2]. |

| Electrical | Conductivity | 4-point probe measurement | Delocalized electron cloud (metals), Band gap and dopants (semiconductors) [2] [4]. |

| Thermal | Thermal Conductivity | ASTM E1461 (Laser Flash) | Atomic bonding strength, Phonon scattering by defects and grain boundaries [2]. |

| Chemical | Biocompatibility | ISO 10993 series | Surface chemistry, Degradation products, Toxicity (leachables) [2]. |

Performance: Fulfilling the Application Need

Performance is the final behavior of a material in a specific application or environment. It is the ultimate test of how well the material's properties meet the design requirements [1].

- Medicine: The performance of a titanium dental implant is judged by its biocompatibility (no toxic response), stability in the jawbone, and mechanical strength to withstand chewing forces. Scaffolding for tissue engineering must perform by providing a supportive structure for cell growth and then degrading safely [2].

- Transportation: A piezoelectric ceramic sensor in a car's airbag system performs correctly if it reliably converts a mechanical impact (deceleration) into an electrical signal to trigger deployment [2].

- Electronics: The performance of a silicon wafer in a photovoltaic cell is measured by its efficiency in converting solar energy into electricity [2] [4].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Protocol: Heat Treatment of Steel

This classic experiment demonstrates the direct link between processing (heat treatment), structure (phase composition), and properties (hardness).

1. Objective: To investigate the effect of different cooling rates (processing) on the microstructure and hardness (properties) of a plain-carbon steel.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Specimens: Squares of AISI 1045 steel.

- Equipment: Metallurgical furnace, quenching bath (water or oil), tongs, hardness tester (Rockwell or Vickers), metallurgical microscope, mounting press, grinding and polishing stations, etchant (Nital).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Cut and grind specimens to a uniform size. Metallographically polish one face of each sample for microscopic analysis.

- Step 2: Austenitization. Heat all specimens in a furnace to a temperature above the upper critical line (e.g., 850°C) for a sufficient time (e.g., 1 hour) to achieve a homogeneous austenitic microstructure.

- Step 3: Controlled Cooling (Processing). Subject the specimens to different cooling paths:

- Sample A (Annealing): Cool slowly within the furnace.

- Sample B (Normalizing): Cool in still air.

- Sample C (Quenching): Rapidly cool by immersing in a water or oil bath and agitating vigorously.

- Step 4: Characterization (Structure). Etch the polished surfaces of the cooled samples with Nital. Observe under a metallurgical microscope to identify and document the resulting microstructures (e.g., pearlite, bainite, martensite).

- Step 5: Property Measurement. Perform hardness tests on each sample, taking multiple readings to ensure accuracy.

4. Expected Results and Analysis:

- The quenched sample (C) will have the hardest, most brittle martensitic structure.

- The annealed sample (A) will have the softest, most ductile structure of coarse pearlite.

- Data should be tabulated to clearly show the correlation between cooling rate, microstructure, and hardness, directly illustrating the processing-structure-property relationship.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Materials Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Nital Etchant | A nitric acid-alcohol solution used to reveal the microstructure of ferrous (iron-based) alloys for optical or electron microscopy [1]. |

| Silicon Wafer (doped) | A fundamental semiconductor substrate used in electronics and photovoltaics; its properties are fine-tuned via doping with group III or V elements [2] [4]. |

| Zeolites (e.g., ZSM-5) | Microporous crystalline aluminosilicates used as solid acid catalysts. Their performance is defined by their framework structure, which imparts shape-selectivity in catalytic reactions [4]. |

| Monomer Feedstocks | Basic building blocks (e.g., ethylene, styrene, 1,6-diaminohexane) for synthesizing polymers with tailored chain structures and properties [2] [4]. |

| Sputtering Targets | High-purity metal or ceramic sources used in physical vapor deposition (PVD) to create thin films for electronic devices and protective coatings. |

Modern Computational Workflow: Digitized Material Design

Modern materials science heavily relies on high-throughput computing (HTC) and machine learning (ML) to navigate the paradigm. The following diagram outlines a contemporary computational workflow for material design and performance prediction.

This integrated framework involves:

- High-Throughput Computing (HTC): Uses first-principles calculations like Density Functional Theory (DFT) to simulate and predict the properties of thousands of virtual materials, populating vast databases [3].

- Machine Learning (ML): Models, including graph neural networks (GNNs), are trained on HTC data to learn complex structure-property relationships, acting as fast surrogates for more expensive simulations [3].

- Generative Models: Techniques like variational autoencoders (VAEs) and reinforcement learning are used to explore the materials space and propose novel material structures with desired properties, effectively inverting the structure-property relationship for design [3].

The Materials Science Paradigm—processing, structure, properties, and performance—provides an indispensable framework for the rational design and development of advanced materials. The interconnectedness of these elements means that a change in one inevitably ripples through the others. Today, this cycle is being traversed at an unprecedented pace through the integration of traditional experimental methods with powerful computational tools like high-throughput computing and machine learning. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep mastery of this paradigm is crucial for systematically engineering the next generation of materials, from high-strength composites to targeted drug delivery systems, driving innovation across countless industries.

The properties of all engineering materials—from the brittleness of a ceramic cup to the ductility of a copper wire—are fundamentally determined by the arrangement of atoms and the nature of the bonds between them. Understanding this relationship is the cornerstone of materials science and engineering. This guide provides an in-depth examination of how atomic structure and bonding create the fundamental interactions that dictate macroscopic material behavior, framing this knowledge within the essential microstructure-processing-properties relationship central to the field [6]. For researchers and scientists, particularly those in drug development where material properties influence delivery systems and biocompatibility, mastering these principles enables the rational design of new materials with tailored characteristics.

Fundamental Atomic Interactions

Atomic Structure and the Periodic Table

The journey of a material's properties begins with its constituent atoms. An atom consists of a nucleus, containing protons and neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of electrons. The identity of an element is defined by its atomic number (number of protons), while its chemical behavior is governed by the configuration of its valence electrons—those in the outermost shell. These valence electrons participate in bonding and are primarily responsible for a material's electrical, thermal, and optical properties.

- Electronegativity: This is a key periodic trend, measuring an atom's tendency to attract electrons in a chemical bond. The difference in electronegativity between bonding atoms is a primary factor in determining bond type.

- Atomic Radius: The size of an atom influences how closely it can pack with its neighbors, affecting density and related properties.

The position of an element in the periodic table provides a powerful predictive tool for its likely bonding behavior and the subsequent material properties.

Primary Bonding Types

The transfer or sharing of valence electrons between atoms leads to the formation of primary chemical bonds, which are strong and determine a material's basic stability. The three primary bond types exist on a continuum, largely defined by the electronegativity difference of the participating atoms.

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Atomic Bonds

| Bond Type | Electronegativity Difference | Mechanism | Key Properties | Example Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic | Low (0 to ~0.4) | Valence electrons are delocalized, forming an "electron sea" that surrounds positive ion cores. | High electrical & thermal conductivity, ductile, malleable, lustrous. | Iron (Fe), Copper (Cu), Aluminum (Al) |

| Covalent | Moderate (~0.4 to ~1.7) | Valence electrons are shared between specific pairs of atoms. | Very hard, high strength, low conductivity, high melting point, brittle. | Diamond (C), Silicon (Si), Quartz (SiO₂) |

| Ionic | High (> ~1.7) | Valence electrons are transferred from one atom to another, creating cations and anions that attract electrostatically. | Hard, brittle, high melting point, good electrical insulator, often transparent. | Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Alumina (Al₂O₃) |

Secondary Bonding

In addition to strong primary bonds, weaker secondary bonds (or van der Waals forces) play a critical role in material behavior. These bonds do not involve electron sharing or transfer but arise from:

- Dipole Interactions: Fluctuations in electron distribution create temporary positive and negative regions that attract adjacent atoms.

- Hydrogen Bonding: A strong dipole interaction occurring when hydrogen is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom (e.g., O, N, F).

Though individually weak, the collective effect of secondary bonds significantly influences properties like melting point, solubility, and adhesion, and is the primary binding force in many polymers and biological molecules.

From Atomic Bonding to Microstructure

Crystalline Structure

In most solid materials, atoms arrange themselves in highly ordered, repeating patterns known as crystals. The specific geometric arrangement is defined by the Bravais lattice, which describes the points in space that define the crystal's periodicity, and a basis, which defines the atoms associated with each lattice point [6]. The combination of lattice and basis determines the crystal structure. Common metallic crystal structures include:

- Body-Centered Cubic (BCC): Atoms at each corner of a cube and a single atom at the cube's center (e.g., α-Fe, Cr).

- Face-Centered Cubic (FCC): Atoms at each corner of a cube and one atom at the center of each face (e.g., γ-Fe, Al, Cu, Au).

- Hexagonal Close-Packed (HCP): A hexagonal arrangement providing high atomic packing density (e.g., Mg, Zn, Ti).

The crystal structure has a direct impact on properties; for instance, FCC metals are generally more ductile than BCC or HCP metals.

The Role of Defects

A perfect, defect-free crystal is an ideal that does not exist in reality. Defects—deviations from the perfect crystalline arrangement—are ubiquitous and have a profound, often beneficial, effect on material properties [6]. Defects are categorized by their dimensionality:

Table 2: Classification and Impact of Crystalline Defects

| Defect Dimensionality | Type | Description | Influence on Material Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point (0-D) | Vacancy | A missing atom in the lattice. | Affects diffusion, electrical conductivity. |

| Interstitial | An extra atom positioned in a void between lattice sites. | Strengthens metals (solid solution strengthening). | |

| Substitutional | A foreign atom replaces the host atom. | Strengthens metals, can modify electrical properties. | |

| Linear (1-D) | Dislocation | A line defect around which atoms are misarranged. Enables plastic deformation via slip. | Crucially increases ductility and toughness. Without dislocations, metals would be brittle. |

| Planar (2-D) | Grain Boundary | The interface between two crystals (grains) of different orientation. | Hinders dislocation motion (increasing strength), affects corrosion and diffusion. |

| Precipitate | A small particle of a second phase within the matrix. | Significantly strengthens the material (precipitation hardening). |

The relationship between defects and properties is a key tenet of materials science. For example, adding small amounts of carbon to iron (creating interstitial point defects) to form steel, or cold-working a metal to increase dislocation density, are both processing methods that intentionally introduce defects to increase strength [6].

Non-Crystalline Materials

Not all materials are crystalline. Amorphous materials, like glasses and rubbers, lack long-range atomic order. Their atoms are arranged in a more random, liquid-like structure. Polymers often exhibit a semicrystalline structure, with regions of ordered, crystalline chains embedded within an amorphous matrix [6]. The degree of crystallinity in a polymer significantly affects its density, strength, and transparency.

Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Understanding atomic structure and bonding requires robust experimental methodologies. The following protocols outline key techniques for characterizing materials at the atomic and microstructural level.

Protocol for X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) for Crystal Structure Determination

1. Objective: To identify the crystalline phases present in a solid sample and determine lattice parameters, crystal structure, and preferred orientation.

2. SIRO Model:

- Sample: A finely powdered or flat, solid specimen.

- Instruments: X-ray diffractometer (X-ray source, goniometer, detector).

- Reagents: Not applicable.

- Objective: Determine crystal structure and phase composition [7].

3. Methodology: 1. Sample Preparation: For powders, grind the sample to a fine consistency and pack it into a holder to create a flat surface. For solids, ensure a smooth, flat surface. 2. Instrument Setup: Mount the sample in the diffractometer. Select the X-ray wavelength (typically Cu Kα). Set the scan range (e.g., 10° to 80° 2θ) and scan speed. 3. Data Collection: The goniometer rotates the sample and detector while the X-ray source remains fixed. Intensity of diffracted X-rays is recorded as a function of the angle 2θ. 4. Data Analysis: - Identify the position (2θ) of each diffraction peak. - Use Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sinθ) to calculate the interplanar spacing (d) for each peak. - Compare the measured d-spacings and relative peak intensities to a standard database (e.g., ICDD) to identify the crystalline phases present.

4. Troubleshooting and Tips: - Preferred Orientation: In powdered samples, plate-like or needle-like crystals may align, altering relative peak intensities. Use a back-loading preparation technique to minimize this. - Sample Height Error: An error in sample height can cause a systematic shift in all peak positions. Use an internal standard to correct for this.

Protocol for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for Microstructural Analysis

1. Objective: To obtain high-resolution images of a material's surface topography and microstructure, and to perform semi-quantitative chemical analysis via Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

2. SIRO Model:

- Sample: Solid, vacuum-compatible specimen.

- Instruments: Scanning Electron Microscope.

- Reagents: Sputter coater with gold or carbon (for non-conductive samples).

- Objective: Characterize surface morphology, observe defects, and determine elemental composition [7].

3. Methodology: 1. Sample Preparation: Clean the sample surface to remove contaminants. For non-conductive materials, coat the surface with an ultrathin layer of carbon or gold-palladium in a sputter coater to prevent charging. 2. Instrument Setup: Mount the sample on a stub and insert it into the SEM chamber. Evacuate the chamber to high vacuum. Select an accelerating voltage (typically 5-20 kV) and probe current suitable for the material. 3. Imaging: Use the secondary electron (SE) detector for topographical contrast or the backscattered electron (BSE) detector for atomic number (compositional) contrast. 4. Chemical Analysis (EDS): Focus the beam on a region of interest. Collect the emitted X-rays to generate an energy spectrum, identifying the elements present.

4. Troubleshooting and Tips: - Charging: If the image appears to "swim" or is unstable, the sample may be charging. Ensure the conductive coating is uniform and continuous, or reduce the accelerating voltage. - Beam Damage: For sensitive materials (e.g., polymers), use a lower accelerating voltage or lower beam current to minimize degradation.

Data Presentation and Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Materials Synthesis and Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Ingots (e.g., 99.99% Al, Fe) | Base materials for creating alloys with controlled compositions, allowing for precise study of composition-property relationships. |

| Carbon (Graphite) Powder | Used as an additive in iron to create carbon steels (interstitial solid solution), drastically increasing strength and hardness [6]. |

| Dopant Gases (e.g., Arsine, Phosphine) | Used in the semiconductor industry to intentionally introduce substitutional impurities into silicon, altering its electrical conductivity (n-type or p-type doping). |

| Etchants (e.g., Kroll's reagent for Ti, Nital for Fe) | Chemical solutions used to reveal microstructural features like grain boundaries and phases under an optical microscope by preferentially attacking the surface. |

| Sputtering Targets (Au, Pd, C) | High-purity metals used in a sputter coater to deposit thin conductive films on non-conductive samples for SEM analysis. |

| Polymer Monomers (e.g., Ethylene, Styrene) | Building blocks for synthesizing polymers with specific chain structures and properties, enabling the study of structure-property relationships in plastics and rubbers [6]. |

Visualizing Core Concepts

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz and adhering to the specified color and contrast rules, illustrate the fundamental relationships in materials science.

Diagram 1: The Materials Science Paradigm

Diagram 2: Bonding Type Selection Logic

The path from the quantum interactions of atoms to the tangible properties of a material is direct and governed by immutable physical laws. The type of atomic bonding, dictated by the electronegativity of the constituent atoms, establishes the foundation for a material's character. This atomic-level interaction determines how atoms arrange themselves into crystalline or amorphous structures and how they respond to the inevitable introduction of defects. It is the precise control of this microstructure—through careful selection of composition and intelligent processing—that allows materials scientists and engineers to tailor the properties of materials for specific applications, from high-strength alloys to functional polymers for biomedical devices. A deep understanding of these fundamental principles is the key to innovating the next generation of advanced materials.

The field of biomedical engineering has witnessed remarkable advancements through the development and application of diverse material classes, each offering unique properties that make them suitable for specific medical applications. Materials science forms the foundation of modern medical devices, implants, and therapeutic delivery systems, with metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites serving as the fundamental building blocks. The selection of appropriate biomaterials is critical for ensuring biocompatibility, mechanical integrity, and long-term performance within the biological environment. As the demand for more advanced healthcare solutions grows, driven by factors such as an aging population and increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, the importance of understanding these material classes within biomedical contexts becomes increasingly paramount [8] [9]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the four primary material classes used in biomedical applications, examining their properties, applications, and experimental methodologies to serve as a reference for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in materials science research.

Comparative Analysis of Biomedical Material Classes

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Major Biomedical Material Classes

| Property | Metals | Ceramics | Polymers | Composites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Examples | Titanium alloys, Stainless steel, Cobalt-chromium alloys [10] | Alumina, Zirconia, Hydroxyapatite [11] | PLA, PCL, PGA, Collagen, Chitosan [12] [13] [14] | Polymer-ceramic, Polymer-metal [15] |

| Key Advantages | High strength, durability, fracture toughness [10] | Biocompatibility, wear resistance, compression strength [11] | Versatility, biodegradability, ease of processing [13] | Tailorable properties, synergistic effects [15] |

| Limitations | Corrosion, stress shielding, metal ion release [10] | Brittleness, low tensile strength, difficult processing [11] | Degradation rate control, mechanical strength limitations [12] | Complex fabrication, potential interfacial failure [15] |

| Biocompatibility | Good (with surface modifications) [10] | Excellent (bioinert to bioactive) [11] | Excellent (natural typically better than synthetic) [14] | Variable (depends on constituents) [15] |

| Primary Applications | Orthopedic implants, surgical tools, dental roots [10] | Dental implants, bone grafts, joint replacements [9] | Drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, sutures [13] | Bone tissue engineering, dental restorations, orthopedic implants [15] |

| Degradation Behavior | Non-degradable (corrodes over time) [10] | Non-degradable to fully resorbable [11] | Non-degradable to fully biodegradable [12] | Degradation profile can be engineered [15] |

The global market for biomedical materials demonstrates significant growth potential across all categories. The polymer biomaterials sector was valued at $79.06 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $94.98 billion in 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.1% [14]. The bioceramics market is expected to grow from $13.54 billion in 2024 to $34.25 billion by 2035, at a CAGR of 8.8% [9]. This robust expansion underscores the increasing importance of these materials in addressing healthcare challenges.

Biomedical Metals

Material Properties and Applications

Biomedical metals are predominantly used in load-bearing applications where mechanical strength and durability are paramount. Titanium alloys are particularly valued for their high strength-to-weight ratio, excellent corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, making them ideal for orthopedic and dental implants [10]. Stainless steel, specifically 316L, remains widely used for temporary implants like fracture plates and screws due to its cost-effectiveness and adequate properties. Cobalt-chromium alloys exhibit superior wear resistance and are typically employed in joint replacement surfaces where articulation occurs [10]. These materials are selected for their ability to withstand the static and dynamic loads encountered in the human body while maintaining structural integrity over extended periods.

Surface modification techniques are often employed to enhance the biological performance of biomedical metals. These include plasma spraying to create porous surfaces for bone integration, anodization to develop protective oxide layers, and immobilization of biomolecules to promote specific cellular responses [10]. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) has revolutionized the production of metal implants, enabling the creation of complex geometries and porous structures that facilitate osseointegration and can be customized to patient-specific anatomy [10]. The integration of data analytics and AI-driven simulations further assists in predicting material behavior in vivo, reducing development time and improving safety profiles [10].

Experimental Protocols and Testing Methodologies

Corrosion Resistance Testing: Electrochemical techniques including potentiodynamic polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) are employed to evaluate corrosion behavior in simulated physiological fluids (e.g., Hank's solution, artificial saliva) [10]. Testing follows ASTM standards (e.g., ASTM F2129) with parameters including corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (Icorr), and breakdown potential (Eb) recorded. Samples are typically immersed in solutions maintained at 37°C to simulate physiological conditions.

Mechanical Characterization: A comprehensive mechanical assessment includes tensile testing (ASTM E8), fatigue testing (ASTM E466), and hardness measurements. For orthopedic implants, fatigue testing is particularly crucial as it simulates the cyclic loading conditions experienced in vivo. Testing is performed in simulated physiological environments at 37°C to obtain clinically relevant data. Surface characterization techniques including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) are utilized to examine surface topography and composition [10].

Biocompatibility Assessment: Following ISO 10993 standards, biocompatibility evaluation includes cytotoxicity testing using cell lines such as L-929 fibroblasts or human osteoblasts, direct and indirect contact tests, and implantation studies in animal models [10]. For metals with nickel content (e.g., some stainless steels), additional sensitization testing is performed to evaluate potential allergic responses. Animal implantation studies typically involve histological analysis to assess tissue integration and inflammatory responses at predetermined time points.

Biomedical Ceramics

Classification and Clinical Applications

Biomedical ceramics are categorized into three primary classes based on their biological behavior: bioinert, bioactive, and bioresorbable. Bioinert ceramics such as alumina and zirconia maintain their structure in the biological environment and primarily interact with tissues through mechanical interlocking [11] [8]. These materials exhibit excellent wear resistance and are used in bearing surfaces for hip replacements and dental implants. Bioactive ceramics, including hydroxyapatite and certain glass compositions, form direct chemical bonds with living tissue, promoting strong tissue-implant interfaces [8]. Bioresorbable ceramics, such as tricalcium phosphate, gradually degrade within the body while being replaced by natural tissue, making them ideal as bone graft substitutes [11].

The application of biomedical ceramics continues to expand with advancements in material design and processing technologies. In orthopedics, ceramic components are widely used in hip and knee replacements due to their wear resistance and biocompatibility [9]. Dental applications represent a rapidly growing segment, with zirconia-based crowns and bridges becoming increasingly popular due to their excellent aesthetic properties and strength [9]. Emerging applications include customized implants produced through additive manufacturing, porous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, and coatings for metallic implants to enhance their bioactivity [11].

Table 2: Classification of Biomedical Ceramics and Their Applications

| Ceramic Type | Material Examples | Key Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinert | Alumina, Zirconia | High wear resistance, low friction, excellent compressive strength | Dental implants, femoral heads in hip replacements, orthopedic bearings [11] [8] |

| Bioactive | Hydroxyapatite, Bioactive Glass | Forms chemical bond with bone, osteoconductive | Bone graft substitutes, coatings for metallic implants, dental applications [8] [9] |

| Bioresorbable | Tricalcium Phosphate, Calcium Sulfate | Degrades at rate matching new bone formation, replaced by natural tissue | Bone void fillers, scaffolds for tissue engineering, craniofacial reconstruction [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Testing Methodologies

Mechanical Property Evaluation: Ceramic materials undergo comprehensive mechanical testing including biaxial flexural strength measurements (ISO 6872), fracture toughness assessment, and wear testing. For dental applications, fatigue resistance is evaluated under cyclic loading in simulated oral environments. The Weibull modulus is determined to characterize the reliability and structural homogeneity of ceramic components, which is critical for predicting clinical performance [11].

Bioactivity Assessment: The bioactivity of ceramics is evaluated through in vitro immersion studies in simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C. Solution pH changes and ion release profiles are monitored over time. Formation of a hydroxyapatite layer on the material surface, indicating bioactivity, is confirmed using techniques such as scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), thin-film X-ray diffraction (TF-XRD), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) [11].

Manufacturing and Quality Control: Advanced manufacturing techniques including additive manufacturing (3D printing) are employed to create complex ceramic structures. The process involves precise sintering protocols with controlled temperature profiles to achieve optimal density and mechanical properties [11]. Quality control measures include dimensional verification, density measurements, microstructural analysis, and proof testing to ensure consistency and reliability of ceramic components destined for clinical use.

Biomedical Polymers

Natural vs. Synthetic Polymers

Biomedical polymers represent the most diverse class of biomaterials, encompassing both natural and synthetic variants with a wide range of properties and applications. Natural polymers such as collagen, chitosan, fibrin, silk, and hyaluronic acid are derived from biological sources and offer inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and biological recognition sites [13] [14]. These materials closely mimic the native extracellular matrix, facilitating cell adhesion and tissue integration. However, they often suffer from batch-to-batch variability, potential immunogenicity, and limited mechanical strength [14]. Synthetic polymers including polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and their copolymers offer superior control over properties such as degradation rate, mechanical strength, and microstructure [12] [14]. The ability to tailor these properties through chemical modification and processing makes synthetic polymers highly versatile for specific biomedical applications.

Table 3: Classification of Biomedical Polymers and Their Applications

| Polymer Type | Material Examples | Key Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Silk [13] [14] | Inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, biological recognition | Tissue engineering scaffolds, wound dressings, drug delivery systems [13] |

| Synthetic Biodegradable | PLA, PGA, PCL, PLGA [12] [14] | Controllable degradation rates, tunable mechanical properties | Resorbable sutures, drug delivery vehicles, tissue engineering scaffolds [12] |

| Synthetic Non-biodegradable | PEG, PEEK, PU, Silicon-based polymers [13] [14] | Long-term stability, specific mechanical and physical properties | Permanent implants, catheters, medical devices [13] |

The development of hybrid natural-synthetic polymer systems represents a promising approach to combine the advantages of both material types. These systems leverage the mechanical strength and reproducibility of synthetic polymers while incorporating the bioactivity and biocompatibility of natural polymers [14]. Such hybrid materials are particularly valuable in tissue engineering applications where both mechanical integrity and biological functionality are required. Additionally, sequence-defined polymers are emerging as a new class of biomaterials that bridge the gap between synthetic materials and biological precision, enabling unprecedented control over polymer structure and function [16].

Advanced Applications and Experimental Methodologies

Drug Delivery Systems: Polymeric carriers are engineered for controlled drug release through various mechanisms including diffusion, degradation, and stimuli-responsive behavior. Experimental protocols involve encapsulation efficiency determination, in vitro release studies under physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 37°C), and release kinetics modeling [13]. Advanced systems incorporate stimuli-responsive elements that release therapeutic agents in response to specific triggers such as pH changes, enzyme activity, or external stimuli like light or ultrasound [14].

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: Fabrication methods include electrospinning, solvent casting/particulate leaching, freeze-drying, and 3D printing. Scaffolds are characterized for porosity, pore size distribution, mechanical properties, and degradation behavior [14]. Biological evaluation includes cell seeding studies with relevant cell types (e.g., osteoblasts, chondrocytes, fibroblasts), assessment of cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation, and implantation in animal models to evaluate tissue integration and scaffold remodeling.

Smart Polymer Systems: Stimuli-responsive polymers are developed to change their properties in response to environmental cues. Experimental protocols focus on characterizing the responsive behavior, including phase transition temperatures for thermoresponsive polymers, pH-dependent swelling or degradation for pH-sensitive systems, and enzymatic cleavage for enzyme-responsive materials [13] [14]. These systems are particularly valuable for drug delivery applications where site-specific release is desired.

Biomedical Composites

Design Principles and Material Combinations

Biomedical composites are engineered materials that combine two or more distinct constituents to achieve properties that cannot be attained by individual components alone. These materials are designed to meet specific clinical requirements by carefully selecting the matrix and reinforcement phases, their relative proportions, distribution, and interfacial interactions [15]. Common composite systems in biomedical applications include polymer-ceramic composites for bone tissue engineering, polymer-polymer composites for tailored degradation profiles, and metal-polymer composites for orthopedic implants with reduced stiffness mismatch [15]. The fundamental principle underlying composite design is the synergistic combination of materials to overcome the limitations of single-phase systems.

In bone tissue engineering, composites combining biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLLA, PLGA) with bioactive ceramics (e.g., hydroxyapatite, tricalcium phosphate) have shown remarkable success [15]. The polymer component provides processability and controlled degradation, while the ceramic phase enhances osteoconductivity and mechanical strength. The integration of hydroxyapatite into polymeric scaffolds has been demonstrated to improve bioactivity and promote the growth of a mineral layer that closely mimics natural bone [14]. Similarly, dental composites resin matrices reinforced with ceramic fillers have become standard materials for tooth restoration due to their aesthetic appeal and adequate mechanical properties [15].

Experimental Protocols and Testing Methodologies

Composite Fabrication Techniques: Common methods include solvent casting/particulate leaching, melt molding, electrospinning, and 3D printing. For polymer-ceramic composites, techniques such as in situ precipitation of the ceramic phase within polymer matrices or incorporation of pre-formed ceramic particles are employed [15]. Process parameters including temperature, pressure, solvent type, and particle size distribution are optimized to achieve homogeneous distribution of reinforcing phases and strong interfacial bonding.

Interface Characterization: The interface between composite phases is critical to overall performance. Characterization techniques include scanning electron microscopy to examine filler distribution and interface morphology, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy to analyze chemical interactions, and mechanical testing to assess interface strength through methods such as single fiber pull-out tests [15].

Functional Assessment: Composites for tissue engineering are evaluated through in vitro cell culture studies and in vivo implantation. Mechanical properties are characterized under compression, tension, and bending to simulate physiological loading conditions. Degradation studies monitor changes in mass, mechanical properties, and pH of the surrounding medium over time. For bioactive composites, apatite-forming ability is assessed through immersion in simulated body fluid followed by surface analysis [15].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Design

Standardized Testing Frameworks

The evaluation of biomedical materials follows standardized testing protocols to ensure safety, efficacy, and reproducibility. International standards including ISO 10993 (Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices) provide a systematic approach to assess the biocompatibility of materials through a series of tests including cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation, acute systemic toxicity, and implantation studies [10] [11]. Material-specific standards developed by organizations such as ASTM International provide guidelines for mechanical testing, chemical characterization, and performance evaluation tailored to specific material classes and applications. These standardized frameworks enable meaningful comparison between different materials and facilitate regulatory approval processes.

In addition to standardized testing, material-specific characterization protocols are employed. For metallic implants, corrosion resistance evaluation following ASTM standards is essential [10]. Ceramic materials require rigorous mechanical testing including biaxial flexural strength measurements and proof testing to ensure reliability [11]. Polymer characterization encompasses molecular weight distribution, thermal properties, degradation behavior, and mechanical performance under physiological conditions [12] [13]. Composite materials necessitate interface characterization and assessment of synergistic effects between constituent phases [15].

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Advanced analytical techniques are employed to thoroughly characterize biomedical materials at multiple length scales. Surface analysis methods including X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), and contact angle measurements provide detailed information about surface chemistry and wettability, which significantly influence biological responses [10]. Microscopy techniques ranging from optical microscopy to transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveal material morphology and microstructure. Mechanical testing under simulated physiological conditions provides clinically relevant data on material performance.

Biological characterization encompasses in vitro cell culture studies with relevant cell types, analysis of protein adsorption, assessment of cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, and evaluation of inflammatory responses [14]. For in vivo evaluation, animal models are selected based on the intended application, with careful consideration of implantation site, duration, and analytical endpoints including histological analysis, mechanical testing of tissue-implant interfaces, and assessment of immune responses [14].

Figure 1: Biomedical Material Development Workflow. This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to developing and evaluating biomedical materials, from initial selection through clinical translation, with continuous reference to regulatory standards.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomedical Materials Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Types |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluids | In vitro bioactivity and degradation studies | Simulated body fluid (SBF), artificial saliva, Hank's balanced salt solution [10] [11] |

| Cell Lines | Biocompatibility assessment, tissue response studies | L-929 fibroblasts, human osteoblasts, chondrocytes, endothelial cells [10] [14] |

| Molecular Biology Assays | Evaluation of cellular responses to materials | MTT assay for viability, ELISA for cytokine expression, PCR for gene expression [14] |

| Characterization Reagents | Material analysis and labeling | Phalloidin (actin staining), DAPI (nuclear staining), antibodies for specific cell markers [14] |

| Polymer Synthesis Reagents | Synthesis and modification of polymeric materials | Initiators, catalysts, functional monomers, crosslinking agents [13] [14] |

| Ceramic Precursors | Fabrication of bioceramics and composites | Calcium salts, phosphate sources, sintering aids [11] |

| Metal Salts and Alloys | Fabrication and surface modification of metallic implants | Titanium powder, cobalt-chromium alloys, electrolytes for anodization [10] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and materials is critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible results in biomedical materials research. Cell lines should be carefully selected based on the intended application of the material, with relevant primary cells often providing more physiologically relevant data than immortalized lines [14]. Culture media formulations may need to be modified to account for potential interactions with material extracts or degradation products. For in vivo studies, appropriate animal models must be selected based on the anatomical site and physiological response being investigated. The use of standardized reagents and protocols facilitates comparison between studies and enhances the translational potential of research findings.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of biomedical materials is evolving toward increasingly sophisticated and intelligent systems. Additive manufacturing technologies continue to advance, enabling the fabrication of complex, patient-specific implants with tailored mechanical properties and internal architectures that promote tissue integration [10] [11]. The development of smart, responsive materials that can adapt to their environment or deliver therapeutic agents in a controlled manner represents another significant trend [13] [14]. These systems respond to specific stimuli such as pH, temperature, enzyme activity, or external triggers to provide precise spatial and temporal control over their function.

Personalized medicine approaches are driving the development of biomaterials that can be customized to individual patient needs based on factors such as anatomy, genetics, and disease state [11] [13]. The integration of digital technologies including computational modeling and artificial intelligence accelerates material design and prediction of in vivo performance [10]. Additionally, there is growing emphasis on sustainable biomaterials that minimize environmental impact while maintaining performance requirements. The convergence of these trends—personalization, intelligence, digital integration, and sustainability—is shaping the future of biomedical materials research and development.

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in the clinical translation of new biomaterials. Long-term biocompatibility and safety evaluation continues to be a complex process requiring comprehensive testing [14]. Scalable and reproducible manufacturing methods must be developed for advanced materials, particularly those with complex architectures or composition gradients [11]. Regulatory frameworks are evolving to accommodate new materials and manufacturing technologies while ensuring patient safety [10]. Addressing these challenges requires multidisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, biologists, clinicians, and regulatory experts to advance the field and bring innovative solutions to clinical practice.

The exploration of metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites in biomedical contexts reveals a diverse landscape of materials with unique properties and applications. Each material class offers distinct advantages and presents specific challenges that must be carefully considered in the context of intended clinical use. Metals provide unparalleled strength for load-bearing applications, ceramics offer exceptional biocompatibility and wear resistance, polymers deliver versatility and controllable degradation, while composites enable the engineering of tailored properties through synergistic combinations. The ongoing advancement of these material classes, driven by emerging technologies such as additive manufacturing, smart materials, and personalized design, continues to expand the possibilities for medical device development and tissue engineering strategies. As the field progresses, the integration of computational approaches, standardized evaluation methods, and multidisciplinary collaboration will be essential for translating material innovations into clinical solutions that improve patient outcomes and address unmet medical needs.

In materials science, the microstructure of a material—the structure visible at the microscopic level—plays a definitive role in determining its macroscopic properties. This structure encompasses various defects and features, including grains, grain boundaries, and other imperfections that interrupt the uniform crystalline lattice [17]. Among these, grain boundaries are particularly significant. They are two-dimensional defects that form the interfaces between individual crystalline grains in a polycrystalline material [18] [19]. These boundaries mark a transition zone where the regular, periodic arrangement of atoms is disrupted, creating a region of atomic mismatch between crystals of different orientations [20] [19]. Understanding the nature and behavior of these microstructural elements is fundamental to designing and engineering materials with tailored mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties for advanced applications.

Fundamentals of Grain Boundaries and Defect Chemistry

Classification and Structure of Grain Boundaries

Grain boundaries are primarily categorized based on the misorientation angle between adjoining crystals. Low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs), with misorientations typically less than 15 degrees, are composed of an array of discrete dislocations [20] [18]. In contrast, high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs), with misorientations greater than 15 degrees, feature a more complex and disordered atomic structure [20] [18]. A key model for understanding special high-angle boundaries is the Coincident Site Lattice (CSL) model, which identifies boundaries where a fraction of the atomic sites in the two crystals coincide [20] [18]. These are described by a Σ value (the reciprocal density of coincidence sites), with low-Σ boundaries, such as Σ3 twin boundaries, often possessing lower energy and enhanced stability [20] [18].

The atomic-level structure of a grain boundary is not static. Recent groundbreaking research has revealed that grain boundaries can exist in distinct, stable states, akin to phases in bulk materials. In 2025, atomic-resolution microscopy studies on copper demonstrated that a single grain boundary can coexist in two different atomic arrangements, described as "pearl" and "domino" shaped structures, without any change in the misorientation of the crystallites [21]. These grain boundary phases exhibit different properties and can transform into one another under changes in temperature or stress, presenting a new paradigm for interface engineering [21].

The Role of Defects and Dopants

Defects are intrinsic imperfections in a material's crystal structure, and their interaction with grain boundaries is critical. In oxide ceramics, for instance, the concentration and movement of charged defects like oxygen vacancies profoundly impact grain boundary behavior [22]. The process of doping—intentionally adding foreign elements—can be used to manipulate these defects and, consequently, the material's properties [22].

Dopants segregate at grain boundaries, changing the local defect balance and leading to phenomena such as solute drag, which slows down boundary movement [22]. This interaction can cause abnormal grain growth, where a few grains grow disproportionately large, resulting in a bimodal grain size distribution that can be detrimental to mechanical properties [22]. Advanced multiphysics phase-field models that incorporate defect chemistry are now essential tools for simulating these complex interactions and predicting microstructure evolution during material processing [22].

Table 1: Key Defect Types and Their Influence on Microstructure

| Defect Type | Dimensionality | Description | Primary Influence on Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Defects (e.g., vacancies) | 0-D | Atomic-scale vacancies or impurities. | Affect diffusion, electrical conductivity. |

| Dislocations | 1-D | Line defects comprising extra half-planes of atoms. | Govern plastic deformation and strength. |

| Grain Boundaries | 2-D | Interfaces between crystals of different orientations. | Act as barriers to dislocation motion; sites for segregation and corrosion initiation. |

| Precipitates & Inclusions | 3-D | Second-phase particles within the matrix. | Can pin grain boundaries and dislocations, enhancing strength. |

Influence on Material Properties

The microstructure of a material, and grain boundaries in particular, serves as the central controlling factor for its mechanical, kinetic, and functional properties.

Mechanical Properties

Grain boundaries are potent strengtheners. They act as obstacles to the motion of dislocations, the carriers of plastic deformation. This strengthening is quantitatively described by the Hall-Petch relationship: (\sigmay = \sigma0 + ky d^{-1/2}), where (\sigmay) is the yield strength, (\sigma0) is the lattice friction stress, (ky) is a strengthening coefficient, and (d) is the average grain diameter [20] [18] [19]. This relationship shows that reducing the grain size increases the material's strength [20]. However, this relationship can break down at the nanoscale, where other deformation mechanisms may become dominant [20].

Conversely, grain boundaries can also be potential sites of weakness. At elevated temperatures (typically above 0.4 of the melting temperature), grain boundary sliding becomes a prominent deformation mechanism, leading to creep [20]. Furthermore, boundaries can be preferential paths for crack propagation and are often more chemically reactive, making the material susceptible to intergranular corrosion and stress corrosion cracking [18] [23].

Kinetic and Functional Properties

Grain boundaries provide high-diffusivity pathways for atoms due to their more open and disordered structure. This grain boundary diffusion has an activation energy typically 0.4-0.7 times that of bulk diffusion, making it a critical factor in processes like sintering, creep, and phase transformations [20]. The presence of boundaries also disrupts the periodic lattice, scattering electrons and phonons. This scattering reduces electrical and thermal conductivity compared to a single crystal, a property that can be exploited in thermoelectric materials where low thermal conductivity is desirable [18] [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Grain Boundaries on Key Material Properties

| Property | Nature of Influence | Quantitative Relationship / Key Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Yield Strength | Increases with finer grain size. | Hall-Petch: (\sigmay = \sigma0 + k_y d^{-1/2}) [20] [19] |

| Ductility & Toughness | Variable; can be enhanced or reduced. | Dependent on boundary cohesion and cleanliness; low-energy boundaries (e.g., Σ3) improve toughness [20] [19]. |

| Corrosion Resistance | Often decreases. | Boundaries are preferential corrosion sites; rate increases with impurity segregation [18] [19]. |

| Electrical Conductivity | Decreases. | Boundaries scatter electrons, reducing conductivity [18] [23]. |

| Thermal Conductivity | Decreases. | Boundaries impede phonon transport [23]. |

| Diffusivity | Increases. | Activation energy is 0.4-0.7x that of bulk diffusion [20]. |

Current Research and Breakthroughs

The field of microstructural engineering is rapidly advancing, driven by new capabilities in atomic-scale characterization and modeling.

A landmark 2025 breakthrough from Lehigh University involved the complete 3D atomic-level mapping of grain boundaries in alumina ceramics using aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) [24]. This work provides an unprecedented "roadmap" for designing ceramics with superior strength and durability, which could revolutionize applications in aerospace (e.g., more heat-resistant turbine blades) and electronics [24].

Parallel research has firmly established the concept of grain boundary phase transformations. Studies on pure copper have shown that boundaries can transition between distinct structural states with different properties [21]. These transitions, controlled by temperature and stress, are mediated by grain boundary phase junctions, a novel line defect that controls the kinetics of the transformation [21]. This discovery forces a re-evaluation of how interfaces behave and explains previously puzzling phenomena like abnormal grain growth.

Computational materials science has kept pace with these experimental advances. The development of a defect-chemistry-informed phase-field model allows for the simulation of grain growth in electroceramics by fully respecting the thermodynamics of charged point defects, such as oxygen vacancies and dopants [22]. This model confirms that effects like solute drag alone can cause abnormal grain growth and reveals that grain boundary potentials are heterogeneous, being lower for larger grains [22]. This insight opens new avenues for optimizing materials through microstructure design.

Experimental Characterization and Analysis

Methodologies for Microstructural Analysis

Revealing and analyzing microstructure requires a meticulous process of sample preparation and advanced characterization techniques. The core methodology is metallography, which involves sectioning, mounting, grinding, polishing, and etching a specimen to reveal its internal features [25] [26].

- Specimen Preparation: A representative sample is first cut using a wet abrasive cutting process to avoid microstructural damage [26]. The sample is then mounted in resin for handling and ground with progressively finer abrasive papers to remove surface deformation. Final polishing with diamond or alumina suspensions produces a mirror finish essential for microscopic examination [26]. Etching with chemical reagents (e.g., Nital for steels) is then used to selectively attack grain boundaries and phases, making them visible under a microscope [25] [26].

- Imaging and Analysis: Optical microscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) are workhorses for initial microstructural assessment, allowing for the visualization of grain size, morphology, and inclusion distribution [20] [26]. For crystallographic information, Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) is used to map grain orientations and characterize boundary misorientations [20]. The highest resolution techniques, such as atomic-resolution STEM and High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM), enable direct imaging of the atomic structure at grain boundaries [21] [24]. Atom Probe Tomography (APT) provides complementary data by revealing the precise chemical identity of atoms segregated to a boundary [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Microstructural Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Abrasive Cutting Wheel | To extract a representative cross-section from a bulk component without altering its microstructure. |

| Hot Mounting Press & Resin (e.g., Epoxy) | To encapsulate the specimen for easier handling and to protect fragile edges during subsequent preparation. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Paper | For sequential grinding with progressively finer grits to remove damage and create a flat surface. |

| Diamond Suspension & Polishing Cloths | For final polishing to achieve a scratch-free, mirror-like surface necessary for high-resolution imaging. |

| Nital Etchant (Nitric Acid in Ethanol) | The most common etchant for carbon and low-alloy steels; reveals ferrite/pearlite grains and boundaries [26]. |

| Picral Etchant | Used for etching cast iron and high-carbon steels; preferentially attacks cementite phases [25]. |

| Aberration-Corrected STEM | Advanced electron microscopy for atomic-resolution imaging and chemical analysis of interfaces [24]. |

Grain Boundary Engineering and Future Directions

The profound understanding of microstructure has given rise to the field of grain boundary engineering, which aims to control the distribution and type of grain boundaries to optimize material performance [20]. This is typically achieved through thermomechanical processing designed to increase the population of "special" boundaries, such as low-Σ CSL boundaries, which often possess superior properties like higher resistance to corrosion and cracking [20]. This approach has been successfully applied to nickel-based superalloys and stainless steels for use in demanding aerospace and nuclear applications [20].

Future research directions are focused on leveraging the latest discoveries. The ability to map boundaries atom-by-atom will enable the rational design of interfaces in ceramics and metals [24]. The confirmed existence of grain boundary phases suggests a new material design element, where properties could be tuned by inducing specific boundary transitions through temperature or stress [21]. Furthermore, the integration of defect chemistry into predictive, multi-scale models will be crucial for accelerating the development of next-generation materials, particularly for energy applications like solid oxide fuel cells, where grain boundary properties directly dictate ionic conductivity and efficiency [22]. As these tools and concepts mature, the deliberate engineering of microstructure will become an even more powerful strategy for pushing the boundaries of material performance.

Biomaterials are defined as substances that have been engineered to interact with biological systems for a medical purpose—either a therapeutic (treat, augment, repair, or replace a tissue function of the body) or a diagnostic one [27]. The corresponding field of study, biomaterials science or biomaterials engineering, is one of the most multidisciplinary of all sciences, encompassing elements of medicine, biology, chemistry, tissue engineering, and materials science [27] [28].

A critical distinction exists between a biomaterial and a biological material. A biological material, such as bone or wood, is produced by a biological system, whereas a biomaterial is specifically engineered for interaction with living systems [27]. The modern field of biomaterials is approximately 60-70 years old, coinciding with the widespread use of polymers and metals in medical applications, and has since grown to significantly impact human health through devices such as hip implants, stents, and drug delivery systems [28].

The success of any biomaterial depends on its biocompatibility—the appropriate host response for a specific application [27] [29]. This application-specific nature means a material that is biocompatible for one use may not be for another. Additional key requirements include physical compatibility, mechanical performance, and durability, ensuring biomaterials fulfill their intended roles without provoking adverse reactions while withstanding the conditions of the biological environment [29].

Table 1: Global Biomaterials Market Overview and Projections

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2034/2035 Projection | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 178.5 - 192.43 Billion [30] [31] | USD 523.75 - 814.7 Billion [30] [31] | 11.82% - 14.8% (2025-2034/2035) [30] [31] |

Classification of Biomaterials

Biomaterials can be classified based on their origin (natural or synthetic) and, most critically, by their biological response (bioinert, bioactive, and bioresorbable) [32].

Classification by Biological Response

Bioinert Biomaterials: These materials exhibit minimal interaction with their surrounding tissue upon implantation. A fibrous capsule typically forms around bioinert implants, and their biofunctionality relies on tissue integration through the implant. Examples include stainless steel, titanium, alumina, zirconia, and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene [32].

Bioactive Biomaterials: Bioactive materials interact with surrounding bone and, in some cases, soft tissue through a time-dependent kinetic modification of their surface. An ion-exchange reaction between the bioactive implant and surrounding body fluids results in the formation of a biologically active carbonate apatite layer that is chemically equivalent to the mineral phase in bone. Prime examples include synthetic hydroxyapatite, glass-ceramic A-W, and bioglass [32].

Bioresorbable Biomaterials: These materials dissolve upon placement within the human body and are slowly replaced by advancing tissue (such as bone). The resorption rate is critical and must match the growth rate of the replacement tissue. Common examples include tricalcium phosphate and polylactic-polyglycolic acid copolymers [32].

Figure 1: Biomaterials are classified by their biological response into bioinert, bioactive, and bioresorbable categories, each with distinct interaction mechanisms and material examples [32].

Classification by Material Type

Biomaterials are also categorized by their constituent materials, which determines their properties and applications [30] [33] [31].

Metallic Biomaterials: Used for load-bearing applications due to their high strength and fatigue resistance. Examples include titanium and its alloys, cobalt-chromium alloys, and stainless steel. They are predominantly used in orthopedic and dental implants [31].

Polymeric Biomaterials: Represent the most significant product segment in the biomaterials market [30] [31]. They offer versatility, ease of processing, and tunable properties including biodegradability, flexibility, and biocompatibility. Examples include polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and their copolymer PLGA, which degrade into natural metabolites (lactic acid and glycolic acid) [34] [30].

Ceramic Biomaterials: Known for their high compressive strength, biocompatibility, and wear resistance. They are often bioactive or bioresorbable. Examples include calcium phosphates like hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate, which are chemically similar to bone mineral [32].

Natural Biomaterials: Derived from biological sources such as cellulose, collagen, silk, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid. They offer inherent bioactivity but may have less defined compositions compared to synthetic materials [33].

Table 2: Biomaterial Types, Properties, and Applications

| Material Type | Key Properties | Common Examples | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic | High strength, fatigue resistance, load-bearing capacity | Titanium alloys, Stainless steel, Cobalt-Chromium | Joint replacements, bone plates, dental implants [27] [31] |

| Polymeric | Versatile, tunable biodegradability, flexible | PLA, PGA, PLGA, Polyethylene | Drug delivery systems, sutures, tissue engineering scaffolds [34] [30] [31] |

| Ceramic | High compressive strength, bioactive, wear-resistant | Hydroxyapatite, Tricalcium Phosphate, Alumina | Dental implants, bone graft substitutes, coatings [27] [32] |

| Natural | Inherent bioactivity, biocompatibility, biodegradable | Collagen, Chitosan, Hyaluronic acid, Silk | Tissue engineering, wound healing, drug delivery [33] |

Key Properties and Host Response

The in vivo functionality and longevity of any implantable medical device is affected by the body's response to the foreign material, known as the host response [27]. This is defined as the "response of the host organism (local and systemic) to the implanted material or device" [27]. Most materials will elicit some reaction when in contact with the human body, and the success of a biomaterial relies on this reaction being supportive of its function.

The host response occurs through a cascade of processes defined under the foreign body response (FBR) [27]. Tissue injury caused by device implantation initiates inflammatory and healing responses:

- Acute Inflammation: Occurs during initial hours to days post-implantation, characterized by fluid and protein exudation and a neutrophilic reaction as the body attempts to clean and heal the wound [27].

- Chronic Inflammation: If the acute phase persists, it may transition to chronic inflammation, involving the presence of monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes [27].

The ultimate goal in biomaterials design is to minimize adverse immune reactions while promoting integration with surrounding tissues. Bioactivity refers specifically to the ability of an engineered biomaterial to induce a physiological response supportive of its function and performance [27]. For bone implants, this is often gauged by surface biomineralization where a native layer of hydroxyapatite forms at the surface [27].

Figure 2: The host response to biomaterial implantation follows a cascade of processes beginning with tissue injury and progressing through inflammatory and healing phases, ideally resulting in tissue integration [27].

Major Applications in Medicine and Biotechnology

Biomaterials find applications across virtually all medical specialties, with their primary use in medical devices that contact biological systems [27] [28].

Orthopedic Applications

The orthopedics category dominates the biomaterials market, driven by an aging population and increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders [30] [31]. Biomaterials are used in joint replacements (hips, knees, shoulders), bone plates, spinal devices, and as bone graft substitutes. According to the American Joint Replacement Registry, hip and knee procedures in America grew by 14% from 2021 to 2022 [31]. Materials used include metals for load-bearing components, ceramics for wear surfaces, and polymers as articulating surfaces or porous scaffolds [31].

Drug Delivery Systems

Biomaterials enable controlled drug release, improving therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects [34]. They protect drugs from rapid degradation, allow targeted delivery to specific sites, and provide sustained release over extended periods (days to years) [34]. Key examples include:

- Lupron Depot: PLGA microspheres encapsulating leuprolide for prostate cancer and endometriosis [34].

- Doxil: PEGylated liposomal formulation of doxorubicin for cancer treatment [34].

- Gliadel Wafer: Polymeric wafers containing carmustine implanted in the brain after tumor resection [34].

Cardiovascular Devices

Biomaterials are essential components in cardiovascular medicine, used in heart valves, stents, vascular grafts, and pacemakers [27] [29]. The most widely used mechanical heart valve is the bileaflet disc heart valve (St. Jude valve), coated with pyrolytic carbon and secured with Dacron mesh that allows tissue integration [27]. Over 200,000 people annually receive heart valves, and more than two million receive cardiovascular stents [29].

Other Medical Applications

- Dental Applications: Dental implants, tooth fillings, and bone graft materials for mandibular repair [27] [35].

- Ophthalmology: Intraocular lenses (IOLs) for cataract surgery and contact lenses [27]. Seven million people annually have vision restored with IOL implants [29].

- Plastic Surgery: Biomaterials for reconstructive surgery and cosmetic enhancements, including breast implants [27] [31].

- Wound Care: Skin repair devices and artificial tissue, often created from copolymers of lactic and glycolic acid [27].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Protocols

Methodology for Biomaterials in Drug Delivery (Dental Implants)

Background and Aim: Dental implantology faces challenges with infection, inflammation, and osseointegration. Nano and biomaterials present promising opportunities for enhancing drug delivery in dental implant therapies [35].

Method:

- Literature Review: A systematic search of databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science) using keywords: "nanomaterials," "biomaterials," "drug delivery," and "dental implant" [35].

- Study Selection: Inclusion criteria focused on studies utilizing nanoparticles, biocompatible polymers, and bioactive coatings for drug delivery in dental implants [35].

- Material Evaluation: Assessment of various materials including calcium phosphate (CP) nanoparticles, hollow silica nanospheres, hyaluronic acid, gelatin, collagen, and chitosan for their efficacy in controlled drug release, antimicrobial properties, and promotion of osseointegration [35].

Key Findings:

- Nanostructured drug carriers demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy, sustained release profiles, and improved biocompatibility [35].

- Bioactive coatings contributed to better osseointegration and reduced infection risks [35].