Mastering HDR Knock-In: A Comprehensive Guide to Donor DNA Template Design and Optimization

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and exhaustive guide to homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise gene knock-in.

Mastering HDR Knock-In: A Comprehensive Guide to Donor DNA Template Design and Optimization

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and exhaustive guide to homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise gene knock-in. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we detail the critical design parameters for single-stranded and double-stranded donor DNA templates, explore methodologies to boost inherently low HDR efficiency and suppress competing repair pathways, and discuss validation techniques for confirming precise edits. With a focus on practical troubleshooting and leveraging the latest research, this resource aims to equip scientists with the strategies needed to successfully implement CRISPR-mediated knock-in for functional studies, disease modeling, and therapeutic development.

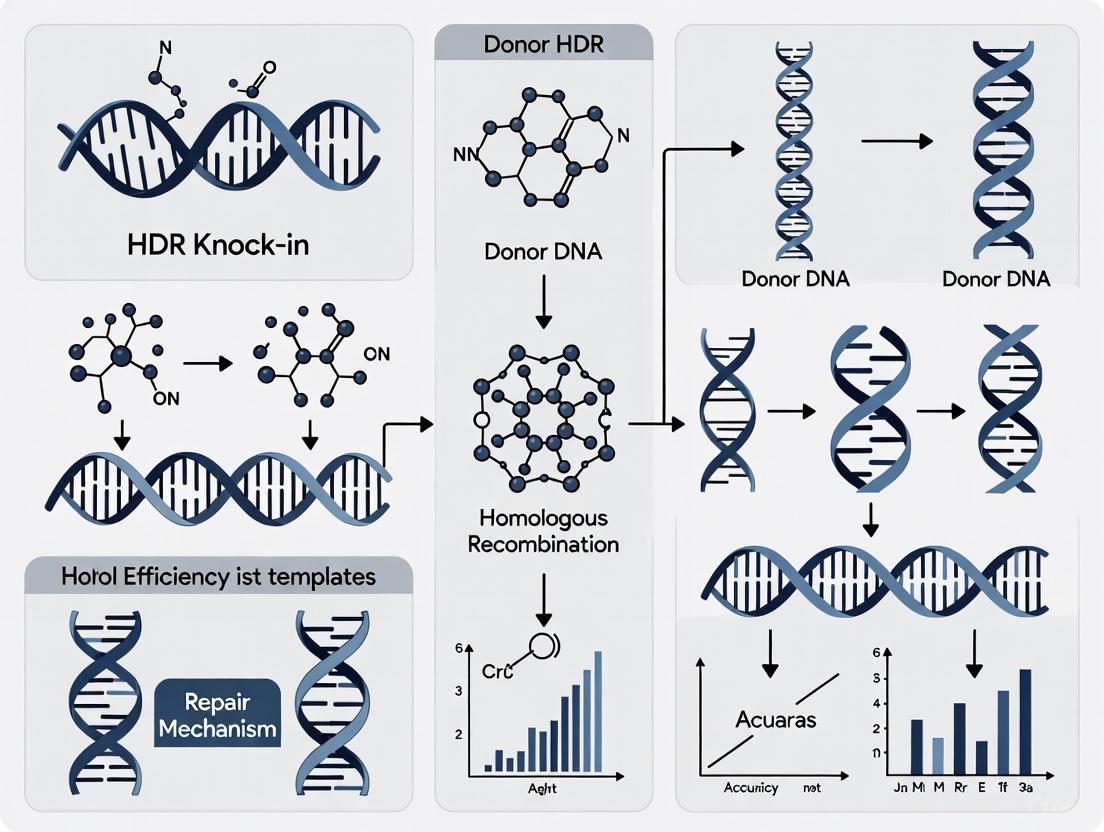

The HDR Knock-In Blueprint: Understanding Core Mechanisms and Donor Template Fundamentals

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering by providing researchers with an unprecedented ability to create targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in genomic DNA. Originally discovered as part of the adaptive immune system in bacteria, this technology enables precise genome editing in a wide variety of cell types and organisms [1]. The system functions as a complex between a guide RNA (gRNA) and the Cas9 nuclease, which together form a programmable molecular machine capable of identifying and cleaving specific DNA sequences with high precision [1] [2].

This application note details the fundamental mechanisms by which the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery creates programmable DSBs, with specific focus on its application in homology-directed repair (HDR) knock-in experiments using donor DNA templates. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for researchers aiming to design effective strategies for precise genome editing, particularly in contexts such as functional genomics, disease modeling, and therapeutic development [1] [3].

Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9

Guide RNA: The Targeting Component

The guide RNA (gRNA) serves as the programmable targeting component of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, directing the Cas9 nuclease to specific genomic loci. The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNA molecules: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains the ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [1] [2]. This engineered single guide RNA (sgRNA) maintains the targeting specificity of the crRNA while ensuring proper complex formation with the Cas9 protein [1].

The targeting specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system is determined by the sequence complementarity between the gRNA spacer region and the target DNA site, which must be immediately adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) with the sequence 5'-NGG-3' for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 [1] [4]. The PAM sequence is recognized directly by the Cas9 protein and is essential for initiating the process of DNA cleavage [1].

Cas9 Nuclease: The Molecular Scissors

The Cas9 nuclease is the effector protein that creates the double-strand break in the target DNA. Upon forming a complex with the gRNA, Cas9 undergoes conformational changes that enable it to interrogate DNA sequences and identify the target site matching the gRNA sequence [1]. Once the correct target is identified and PAM recognition occurs, Cas9 activates its two distinct nuclease domains to cleave both strands of the DNA duplex [1].

The Cas9 protein contains two separate nuclease domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA (the target strand), and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [1]. This coordinated cleavage activity typically results in a blunt-ended double-strand break located 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [1] [5]. The resulting DSB then triggers the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery, setting the stage for either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or precise homology-directed repair (HDR) when a donor template is provided [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System for Creating Programmable DSBs

| Component | Structure/Feature | Function in DSB Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | ~100 nt synthetic RNA; fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA | Programs targeting specificity via 20 nt spacer sequence; scaffold for Cas9 binding |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Multi-domain protein (~160 kDa); HNH and RuvC nuclease domains | DNA binding, PAM recognition, and cleavage of both DNA strands |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' (for SpCas9) | Essential recognition motif for initiating DNA cleavage |

| HNH Domain | Endonuclease domain within Cas9 | Cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA spacer |

| RuvC Domain | Endonuclease domain within Cas9 | Cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand |

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Double-Strand Break Mechanism

DNA Repair Pathways Activated by CRISPR-Cas9

The double-strand breaks created by CRISPR-Cas9 activate competing cellular DNA repair pathways, with significant implications for genome editing outcomes. The two primary repair mechanisms are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) [1] [3].

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is the dominant DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells and operates throughout the cell cycle. This pathway involves the rapid recognition and ligation of broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [1]. The process begins with the binding of the Ku heterodimer (Ku70/Ku80) to the DNA ends, which then recruits additional repair factors including DNA-PKcs, Artemis nuclease, and the XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV complex [1]. While NHEJ efficiently repairs breaks, it often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction, making it useful for gene knockout experiments but problematic for precise knock-in applications [1] [4].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

HDR is a precise repair pathway that utilizes a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the break. This pathway is predominantly active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids are available as natural templates [1] [2]. In CRISPR knock-in experiments, researchers provide an exogenous donor DNA template containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms that match the sequences surrounding the cleavage site [1] [6]. The cellular machinery then uses this template to repair the break, resulting in precise incorporation of the new sequence into the genome [1] [3].

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways Activated by CRISPR-Cas9-Induced DSBs

| Characteristic | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | No homologous template needed | Requires homologous donor template |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all phases | Primarily active in S and G2 phases |

| Repair Fidelity | Error-prone (often creates indels) | High-fidelity (precise) |

| Key Initiating Factors | Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer | MRN complex, CtIP |

| Efficiency in Mammalian Cells | High (dominant pathway) | Low (typically <10% of repairs) |

| Primary Applications | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Precise knock-ins, base corrections, tag insertions |

Diagram 2: DNA Repair Pathways Following CRISPR-Cas9 Cleavage

Experimental Protocols for HDR Knock-In

Donor Template Design and Preparation

Successful HDR-mediated knock-in requires careful design and preparation of the donor DNA template. The design strategy varies significantly based on the size of the insertion and the type of donor molecule used [6] [2] [7].

For small insertions (<100-200 bp), single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) are often preferred. These templates should contain homology arms of 40-90 bp flanking the desired insertion sequence [2] [7]. To prevent re-cleavage of successfully edited alleles, introduce silent mutations in the PAM sequence or gRNA binding site within the donor template [2].

For larger insertions (200 bp to several kb), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates are required. Plasmid-based donors typically utilize homology arms of 200-800 bp, with optimal efficiency observed at 200-300 bp [7] [5]. Double-cut donor vectors, where the donor sequence is flanked by gRNA target sites to enable in vivo linearization, have demonstrated 2-5 fold higher HDR efficiency compared to circular plasmids [5].

Protocol: Designing and Assembling Double-Cut HDR Donors

- Identify the target sequence and design gRNAs targeting both the genomic locus and the flanks of the donor insert

- Clone the insert sequence (e.g., fluorescent protein, tag, or therapeutic transgene) between two gRNA recognition sequences

- Incorporate 300-600 bp homology arms on both sides of the insert

- Include silent mutations in the PAM sequences within the homology arms to prevent re-cleavage

- Verify the complete donor sequence by Sanger sequencing before use [5]

CRISPR Component Delivery and HDR Enhancement

Efficient delivery of all CRISPR components is critical for successful knock-in. Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes (preassembled Cas9 protein and gRNA) provide rapid editing with reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery [3]. Electroporation is often the most efficient delivery method for RNPs, especially in challenging cell types like stem cells and primary cells [4] [3].

To enhance HDR efficiency, several strategic approaches can be employed:

NHEJ Inhibition: Small molecule inhibitors such as Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 can suppress the competing NHEJ pathway. Treatment timing is critical - add inhibitors 2-4 hours before editing and remove within 24 hours to maintain cell viability [3] [7].

HDR Activation: The Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein inhibits 53BP1, a key regulator that favors NHEJ over HDR. This can improve editing efficiency by up to 2-fold in primary cells including iPSCs and HSPCs [7].

Cell Cycle Synchronization: Since HDR is active primarily in S/G2 phases, synchronizing cells at these stages can improve knock-in efficiency. Chemical treatments such as nocodazole (G2/M synchronizer) combined with CCND1 (cyclin D1) have demonstrated a doubling of HDR efficiency in iPSCs [5].

Protocol: HDR Knock-In in Adherent Cells (e.g., HEK293, iPSCs)

- Day 1: Seed cells to achieve 50-60% confluency at transfection

- Day 2:

- Pre-treat with HDR enhancer (if using) 2-4 hours before editing

- For RNP delivery: Complex 2 µM Cas9 protein with sgRNA (1:2 molar ratio) for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Combine RNP complex with 50-100 nM donor template

- Transfert using appropriate method (lipofection for standard lines, electroporation for sensitive cells)

- Day 3: Replace media to remove HDR enhancers/inhibitors

- Days 4-7: Assess editing efficiency via flow cytometry (for fluorescent reporters) or genomic analysis [3] [7] [5]

Table 3: Quantitative HDR Efficiency Under Different Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Cell Type | Insert Size | Homology Arm Length | HDR Efficiency | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard plasmid donor | 293T | 1.8 kb | 600 bp | ~2.5% | [5] |

| Double-cut donor | 293T | 1.8 kb | 600 bp | ~10% | [5] |

| Double-cut donor + Nocodazole/CCND1 | iPSCs | 1.8 kb | 600 bp | Up to 30% | [5] |

| RNP + Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | HEK-293 | 700 bp (GFP) | 200 bp | 2-fold increase | [7] |

| RNP + Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein | iPSCs, HSPCs | Various | 200-300 bp | Up to 2-fold increase | [7] |

| NHEJ-mediated knock-in | Various human cells | 4.6 kb | N/A | Up to 20% | [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Knock-In

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR HDR Knock-In Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Templates | Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks (dsDNA), Megamer Single-Stranded DNA Fragments (ssDNA), GenExact ssDNA, GenWand dsDNA | Provide optimized donor DNA with chemical modifications to enhance HDR efficiency and reduce non-homologous integration |

| HDR Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (small molecule), Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein (53BP1 inhibitor) | Modulate DNA repair pathway choice to favor HDR over NHEJ |

| Cas9 Nuclease Formats | Recombinant Cas9 protein (for RNP), Cas9 mRNA, Plasmid vectors | Provide the nuclease component in various delivery-optimized formats |

| Guide RNA Design Tools | Edit-R HDR Donor Designer, Alt-R HDR Design Tool, GenCRISPR HDR Knock-in Design Tool | Computational tools for designing gRNAs with high on-target and low off-target activity |

| Delivery Reagents | Electroporation kits (e.g., Lonza Nucleofector), Lipofection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX) | Enable efficient intracellular delivery of CRISPR components |

| Validation Tools | T7 Endonuclease I, next-generation sequencing kits, restriction fragment analysis reagents | Assess editing efficiency and specificity |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with well-designed gRNAs and donor templates, HDR efficiency can vary significantly across cell types and target loci. When facing low knock-in efficiency, consider these evidence-based optimization strategies:

Optimize donor design: Ensure the DSB site is located as close as possible to the insertion site - highest efficiency occurs when inserts are within 10 bp of the break [2]. For dsDNA donors, use 200-300 bp homology arms, which typically provide optimal efficiency without unnecessary length [7]. Consider switching to asymmetric homology arms (different lengths) if symmetric arms yield poor results.

Modify delivery timing: Staggered delivery of CRISPR components can improve outcomes. Delivering the donor template 6-24 hours after RNP introduction has shown improved HDR efficiency in some cell types, potentially by allowing DSB formation before donor availability [2] [5].

Address cell-type specific challenges: Difficult-to-edit cells like iPSCs, primary cells, and non-dividing cells often require optimized conditions. For stem cells, use low-passage cells maintained in optimal pluripotency conditions. For primary cells, consider higher RNP concentrations and specialized electroporation protocols [4] [5].

Utilize alternative Cas enzymes: Cas12a (Cpf1) generates sticky ends with 5' overhangs rather than blunt ends, which may favor HDR in some contexts [2]. Additionally, high-fidelity Cas9 variants can reduce off-target effects when working with therapeutic applications [3] [7].

The CRISPR-Cas9 machinery represents a powerful technological platform for creating targeted double-strand breaks that enable precise genome editing through HDR-mediated knock-in. The programmable nature of the gRNA combined with the molecular scissors activity of Cas9 provides researchers with unprecedented control over genetic modifications. By understanding the mechanistic basis of DSB formation and repair, optimizing donor template design, implementing strategic HDR enhancement protocols, and selecting appropriate reagents from the available toolkit, researchers can significantly improve the efficiency and precision of their knock-in experiments. These protocols and principles provide a foundation for applications ranging from basic research in gene function to the development of novel therapeutic interventions for genetic diseases.

The advent of CRISPR-mediated genome editing has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development, hinging on the cell's innate machinery to repair double-strand breaks (DSBs). When a CRISPR nuclease, such as Cas9 or Cpf1 (Cas12a), introduces a DSB at a specific genomic locus, the cell initiates a complex decision-making process to repair the lesion [6] [8]. The repair pathway chosen at this critical juncture directly determines the editing outcome. The primary competing pathways include the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), the precise homology-directed repair (HDR), and two alternative pathways: microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) [8] [9].

The efficiency of HDR-mediated precise knock-in using exogenous donor DNA templates remains a significant challenge in the field. This is largely because HDR competes with these other repair pathways, with NHEJ typically dominating in mammalian cells [9] [10]. Understanding the mechanisms, key players, and regulatory nodes of these pathways is therefore paramount for developing strategies to enhance precise genome editing. This application note delineates the complex interplay between these repair pathways and provides detailed protocols for favoring HDR in CRISPR-mediated knock-in experiments, framed within the context of advanced donor DNA template research.

Pathway Mechanisms and Key Molecular Players

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

HDR is a high-fidelity repair mechanism that utilizes a homologous DNA template—such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template—to precisely repair the DSB. In CRISPR knock-in applications, an exogenous donor DNA is designed with homology arms (HAs) flanking the desired edit (e.g., a fluorescent protein tag or a specific mutation) [6]. The length of these homology arms is a critical design parameter; for single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors, HAs of 30-100 nucleotides are often sufficient, whereas double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors for larger insertions typically require longer arms (200 bp to several kilobases) [6] [11]. The process is mediated by a suite of proteins including the RAD51 recombinase, which facilitates strand invasion and exchange with the homologous template [9].

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is considered the dominant and most versatile DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells, operating throughout the cell cycle. It functions by directly ligating the broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [8] [12]. This speed and template-independence come at the cost of fidelity, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the junction site, which can be leveraged for gene knockout studies [9]. Key regulators of NHEJ include the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) and DNA Ligase IV [9] [12]. The kinase activity of DNA-PKcs is a prominent target for inhibition to steer repair toward HDR.

Alternative Repair Pathways: MMEJ and SSA

Beyond the classical HDR and NHEJ pathways, two alternative pathways significantly impact editing outcomes.

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): Also known as theta-mediated end joining, MMEJ repairs DSBs by aligning short microhomologies (2-20 nucleotides) flanking the break point before trimming the overhangs and ligating the ends [8] [9]. This process, orchestrated by polymerase theta (Polθ, encoded by the POLQ gene), typically results in deletions that are larger than those from NHEJ [8] [9].

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): SSA is activated when a DSB occurs between two direct repeat sequences. The repair process involves the resection of DNA ends to expose the homologous regions, which are then annealed by the RAD52 protein [8]. This results in the deletion of the sequence between the two repeats and one of the repeat copies. Recent studies have shown that SSA suppression can reduce specific imprecise donor integration patterns, such as "asymmetric HDR" [8].

The following diagram illustrates the competitive landscape and key outcomes of these four repair pathways at a CRISPR-induced double-strand break.

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Interactions and Editing Outcomes

Understanding the relative contributions and outcomes of each pathway is crucial for experimental design and interpretation. The following tables summarize key characteristics and quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Pathway | Template Required | Key Effector Proteins | Fidelity | Primary Editing Outcome | Cell Cycle Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDR | Homologous donor DNA (endogenous or exogenous) | RAD51, BRCA2 | High | Precise knock-in (insertions, substitutions) | S and G2 phases |

| NHEJ | None | DNA-PKcs, DNA Ligase IV, 53BP1 | Low | Small insertions/deletions (indels) | Throughout cycle |

| MMEJ | Microhomology (2-20 nt) | POLQ (Polθ), PARP1 | Low | Deletions flanked by microhomology | Throughout cycle |

| SSA | Long homologous repeats | RAD52 | Low | Deletion of sequence between repeats | S and G2 phases |

Table 2: Impact of Pathway Inhibition on HDR Efficiency and Editing Purity (Selected Data from Human Cell Studies)

| Inhibition Strategy | Target | Cell Type | Effect on HDR Efficiency | Effect on Indels/Imprecise Integration | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibition (Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) | DNA-PKcs | RPE1 (human) | Increase from ~6-7% to ~17-22% [8] | Significant reduction in small deletions (<50 nt) [8] | Increased perfect HDR but imprecise integration still accounted for nearly half of all events [8] |

| MMEJ Inhibition (ART558) | POLQ | RPE1 (human) | No significant effect on mNG+ cells; significant increase in perfect HDR in sequencing data [8] | Reduction in large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels [8] | MMEJ suppression reduces nucleotide deletions around the cut site [8] |

| SSA Inhibition (D-I03) | RAD52 | RPE1 (human) | No significant effect on mNG+ cell population [8] | Reduces asymmetric HDR and other donor mis-integration events [8] | SSA suppression decreases imprecise donor integration [8] |

| Combined NHEJ & MMEJ Inhibition (HDRobust) | DNA-PKcs & POLQ | H9 hESCs | Up to 93% (median 60%) of chromosomes edited by HDR [9] | Indels reduced from 82% to 1.7%; large deletions/ rearrangements abolished [9] | Outcome purity >91%; efficient correction of pathogenic mutations in patient-derived cells [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Modulation

Protocol: Enhancing HDR via Combined NHEJ and MMEJ Inhibition

This protocol, adapted from the HDRobust method, details the transient inhibition of NHEJ and MMEJ to achieve high-purity HDR in human cells [9].

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., H9 hESCs, K562, RPE1)

- CRISPR-Cas9 components: Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3, crRNA, tracrRNA (IDT)

- HDR donor template: ssDNA oligo with Alt-R HDR modifications or dsDNA donor

- Small molecule inhibitors: Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi) and ART558 (MMEJi)

- Electroporation system (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector System)

- Appropriate cell culture media and supplements

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Formation: Resuspend Alt-R Cas9 electroporation enhancer to a stock concentration of 500 µM. Complex 2 µM of Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 with equimolar amounts of crRNA and tracrRNA to form the RNP complex. Incubate at room temperature for 15-30 minutes.

- Donor Template Preparation: Design and synthesize a single-stranded DNA donor oligo with proprietary Alt-R HDR modifications to enhance stability and HDR rates [13]. For introducing point mutations or short insertions, use a final donor concentration of 0.5 µM during electroporation. For larger insertions, use a plasmid or dsDNA donor with appropriately long homology arms.

- Cell Preparation and Electroporation: Harvest and count cells. For each electroporation reaction, resuspend 1x10^5 to 1x10^6 cells in the appropriate Nucleofector Solution. Combine the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex and the HDR donor template. Transfer the mixture to a certified cuvette and electroporate using the recommended program for your cell type.

- Post-Electroporation Inhibitor Treatment: Immediately after electroporation, plate the cells in pre-warmed culture media. Add the combined pathway inhibitors: 1 µM Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi) and 30 µM ART558 (MMEJi). Incubate the cells with the inhibitors for 24 hours, as HDR typically occurs within this timeframe after Cas9 delivery [8].

- Recovery and Analysis: After 24 hours, replace the inhibitor-containing medium with fresh standard culture medium. Allow cells to recover for 3-5 days before analyzing editing outcomes. Assess HDR efficiency via flow cytometry (for fluorescent tag knock-in) or by amplicon sequencing (for precise sequence changes) [8] [9].

Protocol: High-Throughput DNA Damage and Repair Analysis (HiIDDD)

The HiIDDD pipeline enables quantitative, single-cell measurement of DNA damage markers (53BP1 and γ-H2AX) in primary immune cells, useful for assessing DSB induction and repair dynamics across experimental conditions [12].

Materials:

- Primary immune cells (e.g., CD4+ T cells, B cells, monocytes)

- 384-well poly-D-lysine coated microplates

- Antibodies: anti-53BP1, anti-γ-H2AX, fluorescent secondary antibodies

- DNA stain (e.g., DAPI)

- High-throughput imaging system (e.g., ImageXpress Micro Confocal)

- Automated liquid handling system (optional but recommended)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Immobilization: Seed cells in 384-well poly-D-lysine coated plates at an optimized density (~0.6–1.0 x 10^5 cells/well for T cells; ~8 x 10^4 cells/well for B cells and monocytes) in a total volume of 40 µl per well. Centrifuge plates briefly (400 x g, 4 min, RT) to promote contact with the substrate before fixation.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize cells with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Block cells with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. Incubate with primary antibodies (anti-53BP1 and anti-γ-H2AX) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The following day, wash cells three times with PBS and incubate with appropriate fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- High-Throughput Imaging and Analysis: After counterstaining nuclei with DAPI, acquire images using an automated high-content imager, capturing 9-15 fields of view per well to analyze 2,000-5,000 cells per sample. For 53BP1, which forms distinct foci, quantify the integrated spot intensity per cell. For γ-H2AX, which shows more diffuse nuclear staining upon damage, measure the total mean nuclear intensity [12].

- Data Management: Analyze images using integrated spot detection algorithms or deep learning techniques. Ensure robust data management aligned with FAIR data principles for large-scale datasets [14].

The workflow for this high-throughput analysis is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Enhancement

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Modulating DNA Repair Pathways

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in HDR Enhancement | Example Vendor/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | Small molecule inhibitor of NHEJ | Increases HDR efficiency by blocking the dominant NHEJ pathway; compatible with various cell lines and CRISPR systems [8] [13]. | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) |

| ART558 | Small molecule inhibitor of POLQ (Polθ) | Suppresses the MMEJ pathway, reducing large deletions and increasing the proportion of perfect HDR events [8]. | Commercial research suppliers |

| D-I03 | Small molecule inhibitor of RAD52 | Suppresses the SSA pathway, reducing asymmetric HDR and other imprecise donor integration events [8]. | Commercial research suppliers |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Oligos | Single-stranded DNA donor templates | Designed with proprietary modifications (e.g., Alt-R HDR modification) to increase stability and HDR rates compared to unmodified oligos [13]. | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) |

| GenExact ssDNA | High-quality single-stranded DNA donors | Provides high knock-in efficiency with low cytotoxicity, suitable for clinical-scale non-viral T cell engineering [15]. | GenScript |

| HDRobust Substance Mix | Combined inhibitor cocktail | Transiently inhibits both NHEJ and MMEJ in unmodified human cells, achieving high-purity HDR editing with minimal indels [9]. | Protocol-defined mixture |

| Edit-R HDR Donor Designer | Online design tool | Assists researchers in designing optimized ssDNA (≤150 nt) or plasmid DNA donors with appropriate homology arms for their specific knock-in application [6]. | Horizon Discovery |

The strategic inhibition of competing repair pathways represents a powerful approach to overcoming the primary limitation of HDR-mediated precise genome editing—its low efficiency relative to error-prone repair mechanisms. The data clearly demonstrates that while inhibiting NHEJ alone provides a significant boost to HDR efficiency, it is insufficient to fully suppress imprecise integration [8]. The combined, transient inhibition of both NHEJ and MMEJ has emerged as a particularly potent strategy, enabling HDR efficiencies exceeding 90% in some cases while drastically reducing indels and other unintended on-target events [9].

The choice of donor template structure is equally critical. Evidence indicates that single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors, especially those with stabilizing modifications and used in the "target" orientation, can outperform double-stranded DNA donors, particularly for shorter inserts [11] [13]. Furthermore, the emerging role of the SSA pathway in causing specific imprecise integration patterns, such as asymmetric HDR, highlights that future optimization efforts may require a three-pronged approach targeting NHEJ, MMEJ, and SSA simultaneously [8].

For researchers aiming to achieve high-precision knock-ins, the recommended path involves the use of high-quality, modified ssDNA donor templates in conjunction with a combined small molecule inhibitor treatment against NHEJ and MMEJ, delivered immediately following RNP electroporation. This methodology, thoroughly detailed in the protocols above, provides a robust framework for enhancing the efficacy and fidelity of HDR-dependent genome editing across a broad range of basic research and therapeutic applications.

In the field of precision genome editing, successful homology-directed repair (HDR) knock-in experiments depend critically on selecting the appropriate donor DNA template. The donor template serves as the blueprint for introducing specific genetic modifications—from single nucleotide changes to insertion of large fluorescent reporters—into precise genomic locations. Researchers currently face a choice between three primary template types: single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), and long single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Each template type engages distinct cellular repair pathways, exhibits different performance characteristics across cell types, and requires specific design considerations. Understanding these variables is essential for optimizing editing efficiency, minimizing off-target effects, and achieving the desired genetic outcomes in both basic research and therapeutic applications. This guide synthesizes current evidence to provide a structured framework for selecting and implementing the optimal donor template strategy for specific experimental goals.

Donor Template Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the three main donor template types to guide initial selection based on experimental parameters.

Table 1: Donor Template Selection Guide

| Template Type | Optimal Insert Size | Homology Arm Length | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN | < 200 bp [16] | 30–60 nt [16] | High HDR efficiency for small edits; reduced off-target integration [17] | Limited carrying capacity | Single nucleotide changes, short tags, small epitopes |

| Long ssDNA | 200 bp – 5 kb [18] | 40–700 nt [11] [18] [16] | Lower cytotoxicity than dsDNA; reduced random integration [18] [17] | Complex production; variable efficiency by cell type [19] | Endogenous gene tagging (e.g., fluorescent proteins) |

| dsDNA | 1–3 kb [16] | 200–300 bp (short); up to 2 kb (long) [11] [16] | Simplified production; superior efficiency in some cell lines [19] | Higher cytotoxicity; increased off-target integration [18] [17] | Large insertions in cell lines where it demonstrates higher efficiency |

Performance Factors and Context-Dependent Efficiency

Template performance varies significantly across biological contexts. While long ssDNA generally demonstrates lower cytotoxicity and reduced off-target integration compared to dsDNA [18] [17], its efficiency relative to dsDNA is cell line-dependent. A 2023 study in human diploid RPE1 and HCT116 cells found that ssDNA was not superior to dsDNA for long insertions, showing both lower knock-in efficiency and reduced precise insertion ratios with 90-base homology arms [19]. In contrast, research in primary human T cells and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has demonstrated that long ssDNA templates achieve high knock-in efficiency with significantly reduced toxicity [18] [17].

For ssODNs, the template polarity (sense vs. antisense relative to the target strand) significantly impacts efficiency. Some studies indicate that the "target" strand (coinciding with the sgRNA-recognized strand) generally outperforms the "non-target" orientation, though optimal polarity can be locus-dependent [11] [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Long ssDNA Production via T7 Exonuclease Digestion

This protocol enables robust production of high-quality long ssDNA donors for knock-in experiments, adapted from optimized methodologies [19].

Step 1: Primer Design and PCR Amplification

- Design primers with 5' phosphorothioate (PS) modifications on the strand to be preserved. Use a two-step PCR approach to ensure high-fidelity PS bonding, which is crucial for protection from exonuclease digestion [19].

- Amplify the dsDNA template containing your insert and homology arms using high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

Step 2: T7 Exonuclease Digestion

- Purify the PCR product using column-based purification.

- Prepare digestion reaction: 1-2 µg PCR product, 1× T7 Exonuclease Reaction Buffer, 10-20 U T7 Exonuclease.

- Incubate at 25°C for 30-60 minutes, then heat-inactivate at 75°C for 10 minutes.

Step 3: Purification and Quality Control

- Purify the ssDNA using ethanol precipitation or commercial purification kits.

- Verify ssDNA integrity and purity via agarose gel electrophoresis and Bioanalyzer. High-purity ssDNA should show >98% purity without detectable dsDNA contamination [17].

Protocol 2: RNP and ssDNA Donor Electroporation in iPSCs

This protocol outlines an efficient method for precise gene knock-in in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using Cas9 RNP complexes and long ssDNA donors [18].

Step 1: RNP Complex Formation

- Complex recombinant Cas9 protein with in vitro-transcribed sgRNA at a 1:2 molar ratio in a suitable buffer.

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form RNP complexes.

Step 2: Electroporation Preparation

- Culture and harvest ChiPSC18 cells (or similar iPSC line) at 80-90% confluence.

- Prepare electroporation mixture: 2-4 µg RNP complexes, 1-3 µg long ssDNA donor, cells resuspended in electroporation buffer.

Step 3: Electroporation and Recovery

- Electroporate using Neon Transfection System (1,400 V, 10 ms, 3 pulses) or similar system optimized for stem cells.

- Plate cells on pre-coated culture dishes with supplemented stem cell medium.

- Assess viability and editing efficiency after 48-72 hours via flow cytometry and genomic PCR.

Critical Considerations:

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Biochemical and Genetic Enhancement Approaches

Advanced strategies can significantly boost HDR efficiency by modulating cellular repair pathways and enhancing donor template functionality.

Table 2: HDR Efficiency Enhancement Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Reported Impact | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAD52 Supplementation | Promotes ssDNA integration during repair | 4-fold increase in ssDNA integration [20] | Increases template multiplication [20] |

| 5' End Modifications | Prevents concatemerization; improves nuclear import | 8-20 fold increase in single-copy integration [20] | Requires modified oligonucleotides |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Shifts repair balance toward HDR | Up to 90.03% HDR efficiency when combined with optimized donors [21] | Potential cell toxicity concerns |

| HDR-Boosting Modules | Incorporates RAD51-preferred sequences to recruit endogenous repair machinery | Significantly enhanced HDR across multiple loci [21] | Chemical modification-free approach |

Donor Engineering and Pathway Modulation

The diagram below illustrates how strategic donor engineering and cellular pathway modulation work synergistically to enhance HDR outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HDR Donor Template Research

| Reagent/System | Primary Function | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long ssDNA Production System | Enzymatic ssDNA generation from dsDNA | Produces high-quality ssDNA up to 5 kb; selective strand digestion | Guide-it Long ssDNA Production System [18] |

| Cas9 RNP Systems | Delivery of editing components | Reduced off-target effects; high efficiency in primary cells | Recombinant Cas9 protein with in vitro transcribed sgRNA [18] |

| HDR Donor Blocks | Synthetic dsDNA donor templates | Defined sequence; optimized homology arms | Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks [16] |

| HDR Design Tools | In silico donor design | Algorithm-based optimization of homology arms | IDT HDR Design Tool [16] |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Shift repair toward HDR | Small molecule inhibition of competing pathway | M3814 [21] |

The selection of an optimal donor template for CRISPR HDR-mediated knock-in requires careful consideration of multiple interdependent factors, including insert size, target cell type, and desired outcome specificity. ssODNs remain the gold standard for introducing small sequence changes, while long ssDNA templates excel in applications requiring lower cytotoxicity and reduced random integration, particularly in sensitive primary cells and stem cells. Despite the advantages of long ssDNA, dsDNA donors can demonstrate superior performance in certain cell lines and remain a viable option for large insertions. Emerging enhancement strategies—including biochemical modulation of DNA repair pathways and sophisticated donor engineering—are dramatically increasing HDR efficiency across diverse experimental systems. By applying the structured comparison and optimized protocols detailed in this guide, researchers can make evidence-based decisions to advance their precision genome editing applications from basic research to therapeutic development.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) using CRISPR-Cas9 and donor DNA templates has revolutionized the generation of precise genetic modifications, enabling the creation of sophisticated animal models and holding promise for therapeutic applications [20]. However, the efficiency of HDR-mediated knock-in remains a major bottleneck, as it competes with inherently dominant and error-prone repair pathways like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [20] [22]. The success of a knock-in experiment is not arbitrary but is heavily influenced by specific, controllable design parameters of the donor template. This application note details the critical design elements—homology arm length, insert size, and template modification—that researchers must optimize to maximize HDR efficiency and precision, framing this discussion within the broader context of advancing HDR knock-in research for drug development and disease modeling.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings on homology arm length, insert size, and template modifications to guide experimental design.

Table 1: Impact of Homology Arm Length on HDR Efficiency

| Homology Arm Length | Insert Size | HDR Efficiency Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 - 500 bp | 120 - 2000 bp | Arm lengths of 200–300 bp resulted in the highest HDR efficiency [7]. | K562 cells, Cas9 RNP, Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks [7]. |

| 60 - 58 nt | ~600 bp | Successfully used in a one-step cKO mouse model strategy, achieving up to 42% HDR with optimized conditions [20]. | Mouse zygotes, dsDNA/ssDNA templates, Nup93 locus targeting [20]. |

Table 2: Effect of Donor Template Modifications on HDR and Integration Fidelity

| Template Modification | Template Type | Key Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5'-C3 Spacer | dsDNA / denatured | Increased correctly edited mice by up to 20-fold; high HDR rates (40-42%) [20]. | Mouse zygotes, Nup93 locus [20]. |

| 5'-Biotin | dsDNA / denatured | Increased single-copy integration by up to 8-fold [20]. | Mouse zygotes, Nup93 locus [20]. |

| Chemical Modifications (Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks) | dsDNA | Boosted HDR rates and reduced non-homologous (blunt) integration at off-target DSBs [7]. | HEK-293 and K562 cells, GFP-tagging [7]. |

| Denaturation (to ssDNA) | Long dsDNA | Boosted precise editing and reduced template concatemerization from 34% to 17% [20]. | Mouse zygotes, 5'-monophosphorylated templates [20]. |

| RAD52 Supplementation | ssDNA | Increased HDR efficiency nearly 4-fold (from 8% to 26%) but increased template multiplication [20]. | Mouse zygotes, denatured DNA template [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing HDR in Mouse Zygotes Using Modified Donor Templates

This protocol is adapted from a study generating a conditional knockout (cKO) mouse model for the Nup93 gene, which demonstrated high HDR efficiency using 5'-end modified templates [20].

1. Donor Template Design and Preparation:

- Design: Create a donor DNA fragment (~600 bp) containing your gene of interest flanked by LoxP sites (for cKO). Include homology arms of 60 bp and 58 bp. Introduce silent mutations in the donor to prevent re-cleavage by Cas9.

- Synthesis and Modification: Order the donor template with 5'-monophosphorylation. For enhanced HDR, specify 5'-C3 spacer (5'-propyl) or 5'-biotin modifications [20].

- Denaturation (for ssDNA formation): Heat-denature the long dsDNA template to generate single-stranded DNA, which has been shown to improve precision and reduce unwanted template multimerization [20].

2. CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex Assembly:

- Design two crRNAs targeting the antisense and sense strands flanking the target exon. Using two crRNAs, especially targeting the antisense strand, can improve HDR precision [20].

- Complex the crRNAs with tracrRNA and Cas9 protein to form the Ribonucleoprotein (RNP).

3. Microinjection Mix Preparation:

- Prepare the injection mix containing:

- Cas9 RNP complexes.

- The modified donor template (ssDNA or dsDNA, 5'-C3 or 5'-biotin).

- Optional: Supplement with RAD52 protein (e.g., 100-200 ng/µL) to enhance ssDNA integration. Note that this may increase the frequency of template multiplication [20].

4. Zygote Injection and Animal Generation:

- Perform microinjection of the mix into the pronucleus of mouse zygotes.

- Implant injected zygotes into pseudo-pregnant female mice.

- Genotype the resulting founder animals (F0) for HDR events using PCR and Southern blot analysis to distinguish single-copy integrations from concatemers.

Protocol: HDR in Cell Culture Using Chemically Modified Donor Blocks

This protocol leverages commercially available, chemically modified dsDNA donors to achieve efficient knock-in in human cell lines [7].

1. Donor Template Design with Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks:

- Design: Use the Alt-R HDR Design Tool to design a donor template with homology arms of 200-300 bp, which have been empirically determined to yield optimal HDR efficiency for inserts ranging from 120 bp to 2000 bp [7].

- Ordering: Order the sequence-verified, chemically modified Alt-R HDR Donor Block.

2. Cell Transfection:

- For HEK-293 or K562 cells, use an electroporation system such as the Nucleofector System (Lonza).

- Prepare the electroporation mix containing:

- 2 µM Cas9 RNP complex.

- 50 nM Alt-R HDR Donor Block (for inserts ~700 bp).

- Optional: Add 1 µM Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 to the culture media post-transfection to inhibit NHEJ and further boost HDR rates [7].

3. Post-Transfection Analysis:

- Change media after 24 hours.

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection for genomic DNA isolation.

- Analyze editing efficiency via long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technologies) or ddPCR to detect precise HDR events and potential large-scale aberrations [23].

Critical Risk Mitigation: Large-Scale Genomic Alterations

The use of HDR-enhancing strategies, particularly those involving key pathway inhibitors, can carry the risk of introducing unintended on-target genomic damage. A 2025 study in Nature Biotechnology revealed that the DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648, while effective at increasing HDR rates as measured by short-read sequencing, concurrently caused a significant increase in frequent kilobase-scale deletions, chromosome arm loss, and translocations in multiple cell types, including primary human HSPCs [23].

Risk Mitigation Strategy:

- Comprehensive Genotyping: Move beyond short-read sequencing. Employ long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) of large amplicons (3-6 kb) spanning the target site to detect kilobase-scale deletions [23].

- Phenotypic and Copy Number Assays: For clinically relevant edits, utilize techniques like ddPCR for copy number quantification and single-cell RNA-seq to identify large-scale expression loss indicative of chromosomal alterations [23].

- Reagent Selection: Consider using chemically modified donors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks) that are designed to improve HDR without inherently promoting large deletions, and use HDR enhancers with a known safety profile [7].

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

HDR Knock-In Experimental Workflow

DSB Repair Pathway Decision Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HDR Knock-In Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks (IDT) | Chemically modified dsDNA templates for knock-ins >120 bp. | Designed to boost HDR rates and reduce blunt, off-target integration; sequence-verified [7]. |

| Megamer Single-Stranded DNA Fragments (IDT) | Long ssDNA templates for smaller insertions. | An alternative to dsDNA donors; useful for specific applications but can be more costly and limited in yield [7]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (IDT) | Small molecule reagent. | Increases HDR by blocking the competing NHEJ pathway; compatible with various cell lines and delivery methods [7]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein (IDT) | Protein-based reagent. | Promotes HDR by inhibiting 53BP1; improves efficiency in hard-to-edit primary cells like iPSCs and HSPCs [7]. |

| RAD52 Protein | Recombination mediator protein. | Enhances HDR efficiency when using ssDNA templates, though may increase template multiplication [20]. |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitor (e.g., AZD7648) | Small molecule inhibitor. | Potently enhances HDR by inhibiting a key NHEJ factor. Warning: Associated with increased risk of large-scale on-target genomic alterations [23]. |

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a precise DNA repair mechanism that becomes active following a double-strand break (DSB). Unlike error-prone repair pathways, HDR uses a homologous DNA template to accurately restore genetic information, making it the preferred cellular pathway for precise genome editing applications [24]. The critical limiting factor for HDR activity is its strict confinement to specific phases of the cell cycle—primarily the S and G2 phases [25] [24]. This restriction presents both a challenge and an opportunity for researchers aiming to optimize CRISPR-mediated knock-in strategies. Understanding the biological basis for this cell cycle dependency is fundamental to developing efficient protocols for introducing precise genetic modifications, whether for basic research or therapeutic development [25].

This application note details the mechanistic basis for the cell cycle restriction of HDR and provides actionable protocols to leverage this knowledge for enhancing knock-in efficiency in research settings.

The Mechanistic Basis of Cell Cycle Restriction

The confinement of HDR to the S and G2 phases is not arbitrary but is dictated by the specific molecular requirements of the pathway and the availability of essential components that fluctuate throughout the cell cycle.

Core HDR Mechanism and Key Players

The HDR process initiates with the MRN complex (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1) recognizing and binding to the DSB. In conjunction with CtIP, this complex initiates the resection of the 5' DNA ends, creating short 3' single-stranded overhangs [24]. Long-range resection then follows, mediated by Exo1 and the Dna2/BLM helicase complex, generating extensive 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails. These ssDNA tails are rapidly coated by Replication Protein A (RPA) to prevent secondary structure formation and degradation. The central HDR enzyme, RAD51, then displaces RPA to form a nucleoprotein filament on the ssDNA. This RAD51-ssDNA filament is the active complex that performs a critical function: it scans the cellular DNA and invades a homologous template sequence—typically the sister chromatid—to form a displacement loop (D-loop). DNA polymerase then extends the invading strand using the homologous sequence as a template, ultimately leading to precise repair [24].

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanism of Homology-Directed Repair.

The Sister Chromatid as an Essential Template

The most decisive factor restricting HDR to S and G2 is the physical availability of a homologous repair template. The preferred template for error-free HDR is the sister chromatid, an identical copy of the DNA molecule created during DNA replication in the S phase [24]. Before DNA replication (in G1 phase), only one copy of each chromosome exists. Without a readily available homologous template in close proximity, the cell cannot perform HDR and must resort to other, more error-prone repair pathways like Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). After DNA replication (in S and G2 phases), the sister chromatid is present and can be used as a template for precise repair, making HDR biochemically feasible [24].

Cell Cycle Regulation of HDR Factors

The expression and activity of key HDR proteins are also under tight cell cycle control. Central players like RAD51 and certain components of the resection machinery exhibit peak expression and activity during S and G2 phases, aligning with the period when a sister chromatid is available [24]. Furthermore, the competitive balance between HDR and NHEJ is regulated by cell cycle-dependent factors. Proteins such as 53BP1 and the Shieldin complex stabilize DNA ends against resection, thereby favoring NHEJ. Their activity is particularly influential in G1. In S/G2, factors like BRCA1 and CtIP promote the end resection that is essential for initiating HDR, thereby shifting the balance toward the precise repair pathway [24].

Quantitative Data on HDR Efficiency

The efficiency of HDR is influenced by multiple experimental parameters. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research, which can inform experimental design.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Factors Influencing HDR Efficiency

| Parameter | Experimental Finding | Impact on HDR Efficiency | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Arm Length | 40+ base arms required for robust HDR with ssDNA donors; 300-500 bp recommended for inserts >2 kb. | Increasing arm length improves HDR efficiency, but very long arms may form secondary structures. | [25] [26] |

| Donor Type | Chemically modified ssDNA templates outperform plasmid-derived templates in zebrafish models. | Modified ssDNA donors show lower cytotoxicity and higher specificity. | [27] |

| CRISPR Nuclease | Cas12a generates sticky ends (5' overhangs) and may promote HDR in some contexts compared to blunt-end Cas9 cuts. | Choice of nuclease can influence repair pathway choice; performance is locus-dependent. | [27] [2] |

| Distance from DSB | Highest HDR efficiency when the insertion is within 10 bp of the Cas9-induced break. | Efficiency decreases significantly as the distance between the break and the edit increases. | [2] |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Using DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) can increase HDR but also elevates the risk of large structural variations. | Can significantly boost HDR rates, but requires careful safety assessment due to genotoxic side effects. | [28] [29] |

Practical Protocols for Enhancing HDR

Protocol: Cell Cycle Synchronization to Enhance HDR

Synchronizing cells in S and G2 phases prior to editing is a direct method to increase the proportion of cells competent for HDR.

Material Preparation:

- Cell Line: Actively dividing mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T, iPSCs).

- Reagents:

- Thymidine (final concentration 2 mM)

- Nocodazole (final concentration 100 ng/mL)

- Complete cell culture medium

- CRISPR reagents (Cas9 RNP, HDR donor template)

Procedure:

- Day 1: Seed Cells. Plate cells at an appropriate density so they will be 20-30% confluent at the time of transfection.

- Day 2: First Block. Add thymidine to the culture medium to a final concentration of 2 mM. Incubate for 18 hours. This arrest cells at the G1/S boundary.

- Day 3: Release. Wash cells twice with pre-warmed PBS to thoroughly remove thymidine. Add fresh complete medium and incubate for 8-9 hours. This allows cells to progress into S phase and beyond.

- Day 3: Second Block (Optional). For a tighter synchrony, add nocodazole (100 ng/mL) for 12-16 hours. This arrests cells in prometaphase (G2/M).

- Day 4: Release and Transfect. Wash cells twice with PBS to remove nocodazole. Add fresh medium and perform transfection with CRISPR-Cas9 and HDR donor reagents immediately. This ensures editing occurs when a large fraction of cells are in HDR-permissive phases (late S, G2, M) [25] [2].

Validation:

- Analyze cell cycle distribution using flow cytometry with propidium iodide staining at the time of transfection to confirm successful synchronization.

Protocol: Combined NHEJ Inhibition and HDR Enhancement

Using small molecules to manipulate DNA repair pathways provides a chemical approach to bias repair toward HDR.

Material Preparation:

Procedure:

- Pre-treatment: Add the chosen NHEJ inhibitor to the cell culture medium 1-2 hours before delivering the CRISPR components. Use the manufacturer's recommended concentration (e.g., 1-10 µM for common inhibitors).

- Co-delivery: Perform transfection (electroporation or lipofection) of the Cas9 RNP and HDR donor. The inhibitor remains present in the medium.

- Post-treatment Maintenance: Incubate cells with the inhibitor for 12-24 hours post-transfection.

- Inhibitor Washout: After 24 hours, replace the medium with standard culture medium without inhibitors to restore normal DNA repair and maintain cell viability [2] [29].

Critical Safety Note:

- A comprehensive genomic safety assessment is recommended when using NHEJ inhibitors. Studies have shown that DNA-PKcs inhibitors, while boosting HDR, can simultaneously increase the frequency of kilobase- to megabase-scale on-target deletions and chromosomal translocations [28]. Always use validated methods like CAST-Seq or long-read sequencing to fully characterize editing outcomes.

HDR Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines a complete experimental workflow for a CRISPR knock-in experiment, integrating cell cycle and pathway modulation strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is critical for a successful knock-in experiment. The table below lists key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for HDR Knock-In Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Donor Templates | GenExact ssDNA; GenWand dsDNA; GenCircle dsDNA [26] | Provides the homologous template for precise repair. Chemically modified linear or circular dsDNA can reduce cytotoxicity and improve efficiency. |

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9 (spCas9); Cas12a (Cpf1) [27] [2] | Engineered to generate DSBs at target sites. Cas12a creates sticky ends that may favor HDR in some contexts. HiFi Cas9 variants reduce off-targets. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | M3814; AZD7648; SCR7 [25] [28] [29] | Small molecules that transiently inhibit key NHEJ proteins (e.g., DNA-PKcs), shifting repair balance toward HDR. |

| HDR Enhancer Proteins | CtIP fusions; dominant-negative 53BP1 fusions [25] [24] | Engineered proteins fused to Cas9 to locally recruit pro-HDR factors or block anti-resection factors, directly stimulating HDR. |

| Cell Cycle Agents | Thymidine; Nocodazole [2] | Chemicals used to synchronize the cell cycle at the G1/S boundary (Thymidine) or in M phase (Nocodazole), enriching for HDR-competent cells. |

The restriction of HDR to the S and G2 phases is a fundamental biological constraint rooted in the pathway's requirement for a sister chromatid template and the cell cycle-regulated activity of its core machinery. For researchers, this is not merely a barrier but a key parameter that can be actively managed. By employing strategies such as cell cycle synchronization, small molecule inhibition of NHEJ, and the use of optimized donor templates, it is possible to significantly shift the balance toward precise HDR editing.

Future advancements will likely focus on developing more refined and safer methods to manipulate the cell cycle and DNA repair pathways, particularly for clinical applications. The emerging understanding of large structural variations as a unintended consequence of some HDR-enhancing strategies underscores the need for comprehensive off-target and on-target analysis using long-read sequencing technologies [27] [28]. As the field progresses, the precise control of the cell cycle and DNA repair will remain at the forefront of achieving efficient and safe precision genome editing.

From Design to Bench: Proven Methodologies and Innovative Applications for Successful Knock-In

Homology-directed repair (HDR) is a precise genome editing mechanism that enables researchers to insert, remove, or replace specific DNA sequences at a predetermined genomic location following a CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB) [6]. The process requires a donor DNA template containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms that correspond to sequences adjacent to the cut site. The design and selection of this donor template are critical determinants of knock-in efficiency, influencing both the rate of precise integration and the frequency of unwanted, random integration events [7]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for designing HDR donors, selecting appropriate online tools, and implementing best practices to maximize knock-in efficiency for therapeutic and research applications.

Donor Template Selection and Design Principles

The choice of donor template is primarily governed by the size and nature of the intended genetic modification. The two main categories are single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for smaller edits and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates for larger insertions.

Single-Stranded DNA Oligonucleotides

Applications: Ideal for introducing point mutations, short insertions, or small tags typically under 120 bases [13].

Design Considerations:

- Homology Arm Length: Extensive testing suggests optimal arm lengths of 90 nucleotides for ssODNs [30].

- Chemical Modifications: Unmodified donors can be used, but enhanced options are available. Phosphorothioate (PS) modifications (4 PS bonds, 2 at each end) and proprietary Alt-R HDR modifications significantly improve donor stability and HDR rates. Data demonstrates that Alt-R HDR-modified donors achieve higher knock-in efficiency compared to both unmodified and PS-modified donors [13].

- Design Tools: Online platforms like the Alt-R HDR Design Tool simplify the process by allowing researchers to input a target site and visualize the desired edit, with the tool generating recommended donor sequences and corresponding gRNAs [13].

Double-Stranded DNA Templates

Applications: Necessary for larger insertions, such as fluorescent protein tags (e.g., GFP), which can range from 120 base pairs to several kilobases [6] [7].

Template Options and Performance:

- Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks: These are sequence-verified, double-stranded DNA fragments with proprietary chemical modifications within universal, non-integrating terminal sequences. They are designed to boost HDR efficiency while reducing non-homologous integration at off-target DSBs [7].

- Performance Data: In a comparative study inserting a 700 bp GFP tag, unmodified dsDNA templates showed modest HDR efficiency. In contrast, modified Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks yielded a substantial increase in HDR rates. Combining these modified donors with an HDR enhancer molecule (Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) resulted in the highest observed knock-in efficiency across multiple genomic loci (see Table 1) [7].

- Long ssDNA Templates: While available, long ssDNA templates for large insertions were shown to be less efficient than their dsDNA counterparts in achieving HDR [7].

Table 1: HDR Efficiency Comparison for a 700 bp GFP Insertion

| Donor Template Type | Cell Line | HDR Efficiency (Approx.) | With HDR Enhancer V2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long ssDNA (Targeting Strand) | HEK-293 | Low (~2%) | Moderate Increase |

| Long ssDNA (Non-Targeting Strand) | HEK-293 | Very Low (<1%) | Slight Increase |

| Unmodified dsDNA | HEK-293 | Low (~2.5%) | Moderate Increase |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Block (dsDNA) | HEK-293 | Medium (~7%) | High (~16%) |

| Long ssDNA (Targeting Strand) | K562 | Low (~1.5%) | Moderate Increase |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Block (dsDNA) | K562 | Medium (~5.5%) | High (~13%) |

Homology Arm Length Optimization

Systematic investigation of homology arm length for dsDNA donors reveals a clear optimal range. As shown in Figure 3 of the search results, while HDR can occur with arms as short as 40-100 bp, efficiency is significantly improved with homology arms of 200–300 bp for insertions ranging from 120 bp to 2000 bp [7]. Another study using a double-cut HDR donor system in 293T cells and iPSCs found that 600 bp homology arms led to high-level knock-in, with 97–100% of donor insertion events being mediated by HDR [30]. For conventional circular plasmids, homology arms of ~0.2–0.8 kb are often used, with some reports indicating that arms up to 2 kb can be optimal in iPSCs [30].

Experimental Protocol for HDR-Mediated Knock-In

The following protocol is adapted for use with Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3, Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA, tracrRNA, and Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks in adherent cell lines.

Materials and Reagents

- RNP Complex:

- Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3

- Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA (target-specific)

- Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA

- HDR Donor: Alt-R HDR Donor Block (resuspended in nuclease-free TE buffer)

- Enhancer: Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (small molecule)

- Cells: Adherent cell line (e.g., HeLa, HEK-293)

- Delivery System: 4D-Nucleofector System (Lonza) with appropriate Cell Line Nucleofector Kit

- Media: Complete growth media for the cell line

Step-by-Step Procedure

RNP Complex Formation:

- Complex 2 µM of Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 with a 1.2x molar ratio of crRNA:tracrRNA duplex in a sterile microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

Electroporation Mixture Preparation:

- For one reaction, combine the following in a Nucleocuvette:

- Prepared RNP complex (final concentration 2 µM)

- Alt-R HDR Donor Block (final concentration 50 nM for a 500-700 bp insert)

- 3 µM Alt-R Cas9 Electroporation Enhancer

- 2x10^5 to 1x10^6 cells harvested and resuspended in the supplied Nucleofector Solution.

- For one reaction, combine the following in a Nucleocuvette:

Cell Electroporation:

- Electroporate the mixture using the 4D-Nucleofector System according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol for your specific cell line.

Post-Electroporation Culture with HDR Enhancer:

- Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells to a pre-warmed culture plate containing complete growth media supplemented with 1 µM Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2.

- Incubate the cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Media Change:

- After 24 hours, replace the media with fresh complete growth media (without HDR Enhancer V2).

Genomic DNA Isolation and Analysis:

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-electroporation for genomic DNA isolation.

- Analyze editing efficiency via long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., MinION system) or next-generation sequencing (e.g., MiSeq system). HDR efficiency is calculated as the percentage of reads containing the precise desired edit out of the total aligned reads.

Advanced Strategies to Enhance HDR Efficiency

HDR Enhancer Reagents

Improving HDR efficiency often involves modulating DNA repair pathways to favor HDR over the competing error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway.

- Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2: A small molecule that inhibits key proteins in the NHEJ pathway. It is compatible with various cell lines, Cas enzymes (Cas9, Cas12a), and delivery methods [7] [13]. Data shows it has an additive effect when combined with modified donor oligos, significantly boosting HDR rates [13].

- Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein: A novel protein-based reagent that promotes HDR by inhibiting 53BP1, a key regulator of DSB repair pathway choice. It can improve editing efficiency by up to 2-fold in established and hard-to-transfect primary cells like iPSCs and HSPCs without increasing off-target effects [7] [13].

Donor Engineering and Design

- Double-Cut HDR Donors: A strategic approach where the donor plasmid is itself flanked by sgRNA-PAM sequences, leading to its linearization inside the cell by Cas9. This method has been shown to increase HDR efficiency by twofold to fivefold compared to circular plasmid donors in 293T cells and iPSCs [30].

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Since HDR is most active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, synchronizing cells can improve knock-in rates. One study demonstrated that the combined use of CCND1 (a G1/S cyclin) and nocodazole (a G2/M synchronizer) doubled HDR efficiency, achieving rates up to 30% in iPSCs [30].

Table 2: Summary of Key Reagents for Enhancing HDR Knock-In Efficiency

| Reagent / Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Donor Oligos | Chemically modified ssDNA donors for point mutations/short insertions. | Alt-R HDR modification pattern provides higher HDR rates than unmodified or PS-modified oligos [13]. |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks | Chemically modified dsDNA fragments for large insertions (>120 bp). | Reduces non-homologous integration and improves HDR rates, especially with HDR Enhancer V2 [7]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | Small molecule inhibitor of the NHEJ pathway. | Increases precise HDR events across multiple cell lines; ideal for standard lab use [7] [13]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein | Protein-based inhibitor of 53BP1 to promote HDR. | Improves efficiency in primary cells (iPSCs, HSPCs) by up to 2X; suited for translational research [7] [13]. |

| Double-Cut Donor Design | Donor plasmid linearized in vivo by Cas9 to synchronize with genomic DSB. | 2-5x increase in HDR efficiency compared to circular plasmids [30]. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization | Using compounds (e.g., nocodazole) to enrich for HDR-prone cell cycles. | Can double HDR efficiency in challenging cells like iPSCs [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Design Tool | Online donor template and gRNA design. | Simplifies design process; provides recommended sequences for user specifications [7] [13]. |

| Edit-R HDR Donor Designer | Web-based tool for designing ssDNA and plasmid donors. | Customizes donor oligos for insertion, deletion, or alteration; facilitates plasmid donor assembly [6]. |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Oligos | Single-stranded DNA templates for small edits. | Up to 200 nt; proprietary modifications enhance stability and HDR efficiency [13]. |

| Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks | Double-stranded DNA templates for large knock-ins. | 201-3000 bp; chemically modified to boost HDR and reduce off-target integration [7]. |

| Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease | High-fidelity Cas9 enzyme for creating DSBs. | Reduced off-target editing while maintaining strong on-target activity [13]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | Small molecule for enhancing HDR rates. | Inhibits NHEJ; works across cell lines and with Cas9/Cas12a [7]. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein | Protein-based reagent for enhancing HDR in primary cells. | Inhibits 53BP1; improves editing in iPSCs and HSPCs up to 2-fold [13]. |

Homology-directed repair (HDR) using CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables precise genome editing by leveraging endogenous cellular repair mechanisms. When a CRISPR-induced double-strand break (DSB) occurs, the presence of an exogenous donor DNA template can guide the repair process to incorporate specific genetic alterations, a process fundamental to gene knock-in experiments [6]. The selection of an appropriate donor template is a critical determinant of experimental success, influencing editing efficiency, precision, and practicality. This guide provides a structured framework for selecting between single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for short inserts and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)—including plasmids and linear dsDNA—for larger constructs, consolidating current best practices and protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Template Selection Strategy

The decision-making workflow for selecting the optimal HDR donor template is summarized in the diagram below, which outlines key criteria including insert size, template type, and strategic considerations.

Template Comparison and Performance Data

Quantitative Comparison of HDR Donor Templates

Table 1: Characteristics and performance of major HDR donor template types

| Template Type | Recommended Insert Size | Optimal Homology Arm (HA) Length | Relative HDR Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN | < 50–200 nt [31] | 30–60 nt [32] | High for short edits [33] | Low cytotoxicity [17]; Reduced random integration [31]; Ease of synthesis | Limited cargo capacity; Lower efficiency for long inserts [34] |

| Long ssDNA | ~500 nt–1 kb [31] | 350–700 nt [31] | Variable; can be lower than dsDNA for large tags [34] | Reduced off-target integration vs. dsDNA [17] | Complex production; Potential for lower precise insertion ratio [34] |

| Linear dsDNA (PCR-derived, Donor Blocks) | 120 bp–3 kb [35] [7] | 200–300 bp [7] | High for large inserts (e.g., 1–3 kb) [35] [34] | Cost-effective; Cloning-free production; High-fidelity large knock-in | Higher random integration risk [31]; Can require purification |

| Plasmid DNA | > 1 kb [6] | > 200 bp (often ~1 kb) [6] | Lower than linear dsDNA in human cell lines [34] | Large cargo capacity; Standard cloning techniques | Time-consuming cloning; Lower knock-in efficiency [34] |

Table 2: Experimental HDR efficiency findings from recent studies

| Study Context | Template Type | Insert Size | Homology Arms | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous fluorescent tagging in RPE1/HCT116 | Long ssDNA vs. dsDNA | mNeonGreen (mNG) | 90 nt | dsDNA yielded higher knock-in efficiency and a higher ratio of precise insertion than long ssDNA. | [34] |

| GFP tagging in HEK-293 and K562 | Modified dsDNA (HDR Donor Blocks) vs. long ssDNA | 700 bp | 200 bp | Modified dsDNA templates provided superior large knock-in rates compared to long ssDNA templates. | [7] |

| Conditional knockout mouse model generation | Denatured dsDNA (ssDNA) vs. dsDNA | ~600 bp (with LoxP sites) | 60/58 nt | Denatured templates boosted precise editing and reduced unwanted template concatemer formation compared to dsDNA. | [20] |

| EGFP to EBFP conversion in a reporter system | TFO-tailed ssODN vs. standard ssODN | Point mutation | N/A | Structural tethering of the ssODN via a TFO hairpin doubled the HDR rate from 18% to 38%. | [33] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Knock-in Using ssODN for Short Inserts

This protocol is optimized for introducing point mutations or short tags (e.g., FLAG, HIS) in mammalian cells [31] [32].

Reagents and Materials:

- Chemically synthesized ssODN (sense or antisense strand)

- Recombinant Cas9 protein or Cas9 expression plasmid

- sgRNA (synthesized or in vitro transcribed)

- Electroporation or transfection reagent (e.g., Lonza Nucleofector system)

- Cell culture media and supplements

Procedure:

- Design and Synthesis:

- Design the ssODN with the desired edit flanked by homology arms of 30–60 nucleotides [32].

- To prevent re-cleavage by Cas9, incorporate silent mutations in the PAM sequence or the sgRNA seed region within the ssODN sequence [31].

- Synthesize and purify the ssODN. Purity is critical for high efficiency.

Complex Formation:

- Assemble the Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by pre-incubating recombinant Cas9 protein with sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 for 10–20 minutes at room temperature [32].

Cell Delivery:

- For primary cells like T cells or B cells, use electroporation. Mix the RNP complex with 1–4 µg of ssODN per 100 µL of cells and electroporate using a predefined program (e.g., Lonza Nucleofector program DS-130 for T cells) [17].

- For adherent cell lines, reverse transfection with RNP complexes and ssODN using appropriate reagents can be effective.

Post-Transfection Processing:

- Allow cells to recover in pre-warmed complete medium.

- Analyze editing efficiency after 48–72 hours using flow cytometry (for fluorescent tags), sequencing (for point mutations), or genomic PCR.

Protocol B: Knock-in Using Linear dsDNA for Large Constructs

This protocol describes a cloning-free method for inserting large fragments (e.g., fluorescent reporters) using PCR-amplified linear dsDNA donors [35] [34].

Reagents and Materials:

- Q5 High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix [35]

- Primers containing 90–300 bp homology arms and the insert sequence template

- Recombinant Cas9 protein and sgRNA

- Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza) [35]

- GeneJET PCR Purification Kit [35]

Procedure:

- Donor Template Production:

- Amplify the donor DNA via a one-step PCR using a high-fidelity polymerase. The donor should contain the insert (e.g., GFP) flanked by homology arms of 200–300 bp for optimal efficiency [7] [34].

- Purify the PCR product using a commercial purification kit to remove enzymes and primers. Elute in nuclease-free water or TE buffer. Quantify the DNA concentration.

RNP Complex Assembly:

- Assemble the Cas9 RNP complex as described in Protocol A, step 2.

Cell Electroporation:

- Harvest and resuspend the target cells (e.g., HEK-293, K562, RPE1) in the appropriate electroporation solution.

- For a 20 µL reaction, combine 2 µM of RNP complex with 25–100 nM of purified linear dsDNA donor [7].

- Electroporate the mixture immediately using a device-specific program (e.g., FF-120 for HEK-293 cells).

HDR Enhancement:

- After electroporation, plate cells in medium supplemented with 1 µM Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 or similar small molecule inhibitors of NHEJ to bias repair toward HDR [7]. Replace the medium after 24 hours.

Validation and Analysis:

- Incubate cells for 48–72 hours before analyzing knock-in efficiency. For fluorescent reporters, use flow cytometry. Confirm precise integration via long-read amplicon sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) or junction PCR [7].

Advanced Strategies and Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents for optimizing CRISPR HDR experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Product / Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Delivers high-efficiency cutting with reduced off-target effects and cellular toxicity compared to plasmid-based expression. | Recombinant Cas9 Protein [35] [34] |

| HDR Enhancers | Small molecules or proteins that inhibit the NHEJ pathway or promote HDR to increase knock-in rates. | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 [7]; RAD52 protein [20] |

| Chemically Modified Donors | dsDNA donors with terminal modifications (e.g., 5'-biotin, 5'-C3 spacer) to improve HDR efficiency and reduce non-homologous integration. | Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks [7] |

| Long ssDNA Production Kits | Generate long single-stranded DNA donors from dsDNA precursors for larger ssDNA-based knock-ins. | Guide-it Long ssDNA Production System [31] |