Machine Learning in Materials Discovery and Design: Accelerating the Path to Novel Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in materials discovery and design, with a specific focus on applications for drug development professionals.

Machine Learning in Materials Discovery and Design: Accelerating the Path to Novel Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in materials discovery and design, with a specific focus on applications for drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of ML in materials science, details cutting-edge methodologies from property prediction to generative design, and addresses critical challenges in model optimization and data quality. Furthermore, it presents advanced frameworks for the rigorous validation and benchmarking of ML models, synthesizing insights from recent high-impact studies and community-driven initiatives to outline a future where data-driven approaches significantly shorten the development timeline for new biomedical materials.

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Reshaping Materials Science Fundamentals

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional, human-intensive discovery methods toward data-driven, artificial intelligence (AI)-powered approaches. Traditional materials discovery has long relied on iterative experimental cycles, serendipitous findings, and theoretical calculations that are often computationally expensive and time-consuming. Methods such as density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while accurate, demand significant computational resources and become prohibitive for exploring complex, multicomponent systems [1]. This conventional paradigm significantly constrains the pace of innovation, making the exploration of vast chemical and compositional spaces impractical.

Machine learning (ML) and AI are revolutionizing this process by leveraging large-scale datasets from experiments, simulations, and materials databases (e.g., Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW) to predict material properties, design novel compounds, and optimize synthesis pathways with minimal human intervention [1] [2]. This shift enables researchers to move from lengthy trial-and-error cycles to the targeted creation of materials with predefined functionalities. The integration of AI-driven robotic laboratories and high-throughput computing has established fully automated pipelines for rapid synthesis and experimental validation, drastically reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new materials to fruition [1]. This article details the key data-driven methodologies, provides experimental protocols, and showcases how this new paradigm is being applied to overcome the long-standing challenges in materials discovery.

The Modern Data-Driven Toolkit: Core Methodologies and Algorithms

The integration of machine learning into materials science leverages a diverse set of algorithms, each suited to specific tasks within the discovery pipeline. The following table summarizes the primary ML methodologies and their applications in materials science.

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Methods in Materials Discovery

| Method Category | Examples | Primary Applications in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Accurate prediction of properties for complex crystalline structures; analysis of microstructural images [1] [2]. |

| Generative Models | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Diffusion Models | Inverse design of novel chemical compositions and structures; proposal of synthesis routes [1] [2]. |

| Optimization Frameworks | Bayesian Optimization (BO), Evolutionary Algorithms | Efficient exploration of vast parameter spaces to optimize material compositions and synthesis conditions [1] [3]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) Analysis | Interpreting model predictions to gain scientific insight into structure-property relationships [3] [2]. |

| Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) | AutoGluon, TPOT, H2O.ai | Automating the process of model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and feature engineering [1]. |

These methods are not applied in isolation. A prominent trend is the move toward multimodal AI systems that can process and learn from diverse data types—such as text from scientific literature, chemical compositions, microstructural images, and experimental results—simultaneously. This mirrors the collaborative and integrative approach of human scientists and provides a more comprehensive knowledge base for AI-driven discovery [4]. Furthermore, the rise of Small Language Models (SLMs) offers a path toward more efficient, domain-specific AI tools that can be deployed in resource-constrained environments, such as edge devices or robotic labs, facilitating real-time analysis and decision-making [5].

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

The practical implementation of AI in materials discovery follows structured workflows that combine computational and experimental components. The following protocols detail two prominent frameworks.

Protocol 1: The ME-AI Framework for Discovering Metallic Alloys

This protocol, derived from the work of Virginia Tech and Johns Hopkins University on Multiple Principal Element Alloys (MPEAs), demonstrates how explainable AI can translate expert intuition into quantifiable descriptors [3] [6].

1. Objective: Discover a new MPEA with superior mechanical strength by identifying key descriptive features. 2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Data Source: Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Primary Features (PFs): A set of 12 atomistic and structural features, including electronegativity, electron affinity, valence electron count, and characteristic crystallographic distances (

d_sq,d_nn) [6]. - Software/Toolkit: Dirichlet-based Gaussian Process model with a chemistry-aware kernel [6].

- Validation Method: Synthesis and mechanical testing of predicted alloys.

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Expert-Led Data Curation. A materials expert curates a dataset of 879 square-net compounds from the ICSD. The expert then labels each compound (e.g., as a topological semimetal or trivial material) based on available experimental band structures, computational data, and chemical intuition for related materials [6].

- Step 2: Feature Engineering and Model Training. The 12 predefined PFs are computed for each entry. A Gaussian Process model is trained on this curated dataset to learn the complex relationships between the PFs and the expert-provided labels [6].

- Step 3: Descriptor Discovery with SHAP. The trained model is analyzed using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to interpret its predictions. This XAI technique identifies which features and combinations of features are most critical for the target property, recovering known descriptors like the "tolerance factor" and uncovering new ones, such as a descriptor linked to hypervalency [3] [6].

- Step 4: Prediction and Experimental Validation. The model identifies promising new candidate compositions. These are then synthesized (e.g., via arc melting or solid-state reactions) and their mechanical properties (e.g., hardness, yield strength) are characterized to validate the predictions [3].

Protocol 2: Autonomous Discovery with the CRESt Platform

The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform, developed by MIT, represents a state-of-the-art protocol for fully autonomous, closed-loop materials discovery [4].

1. Objective: Autonomously discover and optimize a multielement catalyst for a direct formate fuel cell. 2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Robotic Systems: Liquid-handling robot, carbothermal shock synthesizer, automated electrochemical workstation, automated electron microscope [4].

- Precursors: Up to 20 different precursor molecules and substrates (e.g., Pd, Pt, and other cheaper metal salts) [4].

- Software/Toolkit: Multimodal AI models (including Large Language Models and Vision Language Models), Bayesian Optimization, computer vision for monitoring.

- Analysis Tools: X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy.

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Knowledge Ingestion and Natural Language Interaction. The researcher converses with CRESt in natural language, defining the project goal. CRESt ingests and processes relevant information from scientific literature and databases to build a knowledge base [4].

- Step 2: Knowledge-Embedded Active Learning. The system uses the literature knowledge to create a high-dimensional "knowledge embedding" for potential recipes. Principal Component Analysis reduces this to a manageable search space. Bayesian Optimization is then used within this space to propose the most promising experiment [4].

- Step 3: Robotic Synthesis and Characterization. A liquid-handling robot prepares the precursor solutions based on the chosen recipe. A carbothermal shock system rapidly synthesizes the nanomaterial. Robotic systems then transfer the sample for automated characterization (e.g., electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction) [4].

- Step 4: Performance Testing and Analysis. The material is automatically tested in an electrochemical workstation to evaluate its performance as a fuel cell catalyst (e.g., measuring power density). Computer vision models monitor the experiments in real-time to detect issues and suggest corrections [4].

- Step 5: Closed-Loop Feedback and Iteration. All newly acquired multimodal data (characterization images, performance metrics) and human feedback are fed back into the AI models. This continuously updates the knowledge base and refines the search space, guiding the next cycle of autonomous experimentation [4].

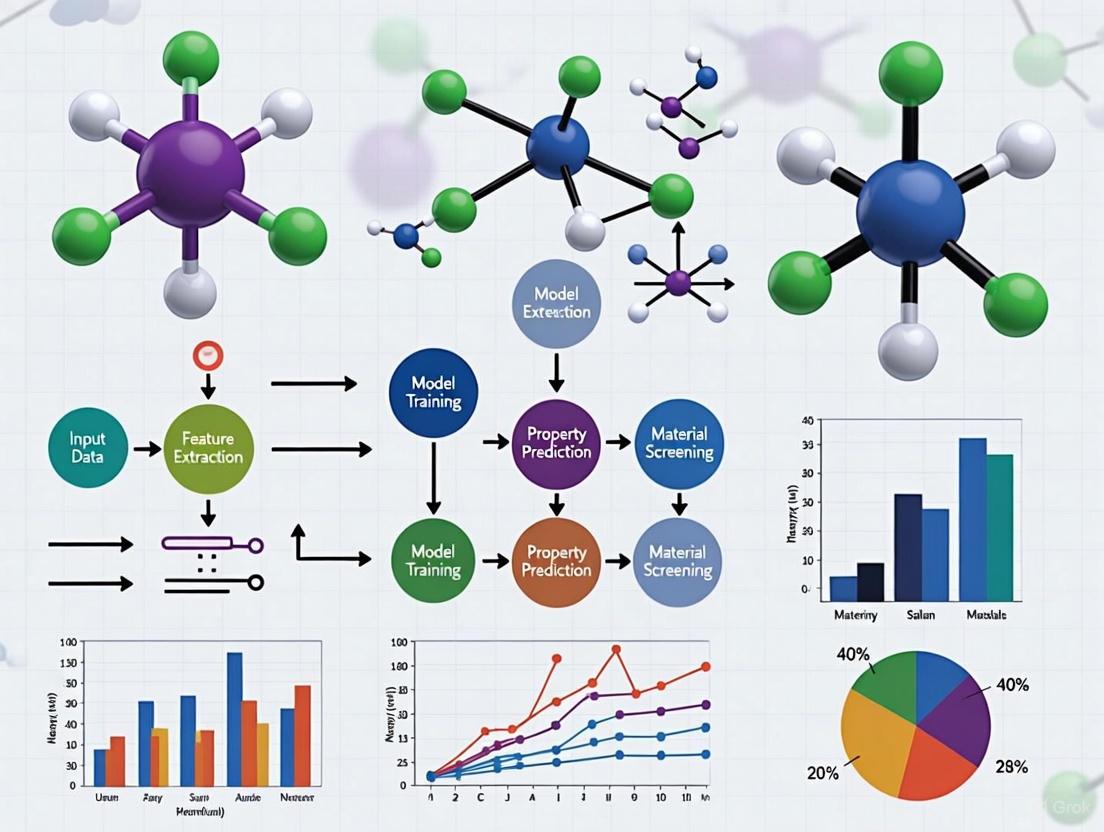

Visualizing the Workflow: From Data to Discovery

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the AI-driven materials discovery process, from initial data handling to final validation.

Diagram 1: The AI-Driven Discovery Workflow.

Diagram 2: The ME-AI Framework for Explainable Discovery.

Successful implementation of data-driven materials discovery relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table catalogues key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Category | Item / Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational & Data Resources | Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW, ICSD | Centralized databases providing crystal structures, thermodynamic properties, and band structures for model training [1]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Deep learning models specifically designed to operate on graph-structured data, ideal for representing crystal structures and molecules [1]. | |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A sample-efficient optimization strategy for guiding experiments by balancing exploration and exploitation in complex parameter spaces [4]. | |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | An Explainable AI method that interprets the output of ML models, revealing the contribution of each input feature to a prediction [3]. | |

| Experimental & Robotic Systems | Liquid-Handling Robot | Automates the precise dispensing of precursor solutions for high-throughput synthesis of material libraries [4]. |

| Carbothermal Shock System | Enables rapid synthesis of nanomaterials (e.g., alloy catalysts) by quickly heating and cooling precursor materials [4]. | |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | Performs high-throughput testing of functional properties, such as catalytic activity for fuel cells or battery performance [4]. | |

| Automated Electron Microscope | Provides rapid microstructural and compositional analysis of synthesized materials without constant human operation [4]. |

The transition from trial-and-error to data-driven design is no longer a future prospect but a present reality in advanced materials research. Frameworks like ME-AI and platforms like CRESt exemplify how machine learning, explainable AI, and robotic automation are being integrated to create a powerful new paradigm for discovery. This approach not only accelerates the identification of novel materials with exceptional properties but also deepens fundamental scientific understanding by uncovering hidden structure-property relationships. As these tools become more sophisticated, accessible, and integrated with physical sciences, they promise to unlock a new era of innovation across energy, electronics, medicine, and beyond.

The field of materials science is undergoing a fundamental shift, moving from experience-driven and trial-and-error approaches to a data-driven research paradigm [7]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool throughout the entire process of intelligent material innovation, enabling accelerated discovery, performance-optimized design, and efficient sustainable synthesis [8]. This paradigm change is largely driven by ML's ability to uncover intricate patterns within complex, high-dimensional materials data that are often challenging to identify through traditional methods [9].

ML techniques are revolutionizing materials research by providing powerful capabilities for predictive modeling and inverse design - where desired properties drive the discovery of new structures [10]. These approaches are significantly reducing the traditional 15-25 year timeline from material conception to deployment, hindering technological innovation across energy, healthcare, and electronics [7] [10]. The integration of computational methods with experimental validation has created new opportunities for tackling longstanding challenges in materials science, from improving corrosion resistance in magnesium alloys to developing novel catalyst materials for clean energy applications [4] [9].

This article provides a comprehensive overview of core ML techniques - supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning - within the context of materials discovery and design. We present structured protocols, comparative analyses, and practical frameworks to equip researchers with the necessary tools to leverage these methodologies effectively in their materials research workflows.

Core Machine Learning Techniques in Materials Science

Machine learning encompasses various approaches that enable computers to learn from data and make decisions without explicit programming for every scenario [11]. In materials science, three primary paradigms have demonstrated significant utility: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning.

Supervised Learning

Supervised learning involves training algorithms on labeled datasets where each instance comprises an input object and a corresponding output value [7]. The fundamental characteristic of supervised learning is that the data are pre-categorized, including data classes, attributes, or specific feature locations [7]. After training on these labeled examples, the algorithm can map new, unseen inputs to appropriate outputs based on the learned patterns.

In materials science, supervised learning excels at property prediction and classification tasks, such as predicting mechanical properties based on composition or classifying crystal structures from diffraction data [7] [9]. These models establish correlations between material descriptors (composition, structure, processing parameters) and target properties (strength, conductivity, catalytic activity), enabling rapid screening of candidate materials without resource-intensive experiments or simulations [8].

Unsupervised Learning

Unsupervised learning operates on unlabeled data, seeking to identify inherent patterns, groupings, or structures without pre-defined categories [7]. These algorithms explore the data's natural organization, revealing hidden relationships that might not be apparent through manual analysis.

For materials research, unsupervised techniques are particularly valuable for materials categorization, pattern discovery in microstructure images, and dimensionality reduction of complex feature spaces [7]. By clustering materials with similar characteristics or reducing high-dimensional representations to more manageable forms, researchers can identify promising regions of materials space for further investigation and gain insights into fundamental structure-property relationships [10].

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) involves an agent learning to make decisions by interacting with an environment to maximize cumulative reward [7]. Through trial and error, the agent discovers optimal strategies or policies for achieving specific goals without requiring explicit examples of correct behavior.

In materials science, RL has found significant application in autonomous laboratories and synthesis optimization, where systems learn optimal processing parameters or synthesis routes through iterative experimentation [12] [4]. Algorithms such as proximal policy optimization (PPO) are increasingly important for controlling autonomous workflows, enabling systems to adaptively refine experimental conditions based on real-time feedback [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Machine Learning Techniques in Materials Research

| Technique | Learning Paradigm | Primary Materials Applications | Key Advantages | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Labeled training data | Property prediction, Classification, Quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) models | High accuracy for well-defined prediction tasks, Direct mapping from inputs to target properties | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forests (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) |

| Unsupervised Learning | Unlabeled data | Materials clustering, Dimensionality reduction, Pattern discovery in microstructures | Reveals hidden patterns without pre-existing labels, Reduces complexity of high-dimensional data | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), k-Means Clustering, Autoencoders, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) |

| Reinforcement Learning | Reward-based interaction with environment | Autonomous experimentation, Synthesis optimization, Processing parameter control | Adapts to complex, dynamic environments, Discovers novel strategies through exploration | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), Q-Learning, Deep Reinforcement Learning |

Application Notes: ML Techniques in Materials Discovery

Supervised Learning for Property Prediction

Supervised learning has become indispensable for predicting material properties across diverse systems, from magnesium alloys to catalytic materials. The ability to establish accurate relationships between material characteristics and performance metrics has significantly reduced reliance on costly experimental characterization and computational simulations [9].

In practice, supervised models have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting mechanical properties such as yield strength, tensile strength, and fatigue life based on composition and processing parameters [9]. For magnesium alloys, models including Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forests (RF) have achieved accurate predictions of mechanical behavior under various thermomechanical processing conditions [9]. Similarly, in catalyst development, supervised learning can correlate elemental composition and coordination environments with catalytic activity and resistance to poisoning species [4].

The effectiveness of supervised learning extends to microstructural analysis, where Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can extract features from micrograph images to predict material properties or classify structural characteristics [9]. These image-based approaches enable rapid assessment of microstructure-property relationships that traditionally required meticulous manual analysis.

Unsupervised Learning for Materials Exploration

Unsupervised learning techniques empower researchers to navigate complex materials spaces without pre-existing labels or categories. By allowing the data to reveal its inherent structure, these methods facilitate novel materials discovery and hypothesis generation.

A prominent application involves using clustering algorithms to identify groups of materials with similar characteristics, enabling researchers to discover new material families or identify outliers with unusual properties [10]. In catalytic materials research, unsupervised learning has helped categorize catalyst compositions based on performance descriptors, guiding the exploration of promising compositional spaces [8].

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and autoencoders transform high-dimensional materials representations (such as crystal structure descriptors or compositional features) into lower-dimensional spaces while preserving essential information [4]. This transformation facilitates visualization of materials relationships and identification of fundamental design principles that govern material behavior [10].

Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Experimentation

Reinforcement learning represents a paradigm shift in experimental materials science, enabling autonomous systems that learn optimal strategies through direct interaction with laboratory environments. These approaches are particularly valuable for problems where the relationship between processing parameters and material outcomes is complex and not fully understood.

In autonomous laboratories, RL agents control robotic systems for materials synthesis and characterization, continuously refining their strategies based on experimental outcomes [12] [4]. For example, systems can learn optimal synthesis recipes for multielement catalysts by adjusting precursor ratios, processing temperatures, and reaction times to maximize target properties such as catalytic activity or stability [4].

RL also excels at adaptive experimental design, where systems dynamically adjust their exploration strategy based on accumulating results. This capability is particularly valuable for resource-intensive experiments, as it focuses resources on promising regions of parameter space [12]. By balancing exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of known promising areas, RL systems can efficiently navigate complex optimization landscapes.

Table 2: Representative Applications of ML Techniques in Materials Science

| Material Category | Supervised Learning Application | Unsupervised Learning Application | Reinforcement Learning Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Alloys | Predicting yield strength and corrosion behavior from composition and processing parameters [9] | Clustering alloy compositions with similar deformation mechanisms [9] | Optimizing thermomechanical processing parameters [9] |

| Catalytic Materials | Predicting catalytic activity from elemental composition and coordination environment [4] | Identifying descriptor relationships for catalytic performance [8] | Autonomous optimization of multielement catalyst synthesis [4] |

| Energy Materials | Forecasting battery cycle life from early-cycle data [7] | Categorizing crystal structures for ion conduction [10] | Self-driving labs for photovoltaic material discovery [2] |

| Polymeric Materials | Relating monomer composition to mechanical properties [8] | Mapping the chemical space of biodegradable polymers [10] | Optimizing polymerization reaction conditions [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Supervised Learning for Mechanical Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the workflow for developing supervised learning models to predict mechanical properties of materials based on composition and processing parameters, with specific application to magnesium alloys [9].

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Data Acquisition: Compile a comprehensive dataset from experimental measurements, computational simulations, or literature sources. Essential features include alloy composition (elemental percentages), processing parameters (extrusion temperature, speed, heat treatment conditions), and target mechanical properties (yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, elongation) [9].

- Data Cleaning: Address missing values through appropriate imputation methods or removal of incomplete records. Identify and handle outliers that may result from measurement errors using statistical methods (e.g., Z-score analysis) [9].

- Feature Engineering: Create domain-informed descriptors such as atomic size mismatch, electronegativity differences, and processing-derived parameters (Zener-Hollomon parameter for thermomechanical processing) [9].

- Data Normalization: Apply standardization (scaling to zero mean and unit variance) or min-max scaling to ensure all features contribute equally to model training [7].

Model Training and Validation

- Dataset Partitioning: Split data into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test sets (10-15%) using stratified sampling to maintain distribution of target variables across splits [9].

- Algorithm Selection: Implement multiple algorithms including Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forests (RF) to compare performance [9].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize model-specific parameters through grid search or Bayesian optimization, using cross-validation on the training set to prevent overfitting [9].

- Model Validation: Evaluate performance on the held-out test set using metrics relevant to regression tasks: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R²) [9].

Model Interpretation and Deployment

- Feature Importance Analysis: Employ permutation importance, SHAP values, or model-specific importance measures to identify dominant factors controlling mechanical properties [9].

- Domain Knowledge Integration: Validate model insights against established metallurgical principles to ensure physical plausibility [9].

- Deployment for Prediction: Utilize the trained model to screen proposed alloy compositions and processing parameters, prioritizing promising candidates for experimental verification [9].

Protocol: Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Materials Synthesis

This protocol details the implementation of reinforcement learning for autonomous optimization of synthesis parameters, with specific application to multielement catalyst discovery [4].

Environment Setup

- State Representation: Define the state space encompassing controllable synthesis parameters (precursor concentrations, temperature, pressure, reaction time) and characterization data (in-situ spectroscopy, microscopy) when available [4].

- Action Space Definition: Establish discrete or continuous actions corresponding to adjustments of synthesis parameters within experimentally feasible ranges [4].

- Reward Function Design: Formulate a reward function based on target material properties (catalytic activity, selectivity, stability) measured through high-throughput characterization [4].

Agent Training

- Algorithm Selection: Implement Deep Reinforcement Learning algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) or Deep Q-Networks (DQN) capable of handling high-dimensional state and action spaces [12] [4].

- Exploration Strategy: Balance exploration and exploitation using approaches such as ε-greedy or adding noise to parameter space, ensuring adequate coverage of the synthesis space [4].

- Experience Replay: Store state-action-reward transitions in a replay buffer and sample batches for training to improve data efficiency and stabilize learning [4].

- Training Iteration: Cycle through action selection, environment interaction, reward computation, and policy updates until performance converges or reaches target thresholds [4].

Experimental Validation

- Robotic Integration: Deploy the trained policy on robotic synthesis platforms capable of executing specified synthesis protocols with minimal human intervention [4].

- Closed-Loop Operation: Implement real-time characterization and feedback to continuously update the policy based on experimental outcomes [4].

- Human Oversight: Maintain researcher supervision for safety-critical decisions and validation of novel discoveries [4].

Diagram 1: RL for autonomous synthesis workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ML-driven materials research requires both computational tools and experimental resources. The following table outlines essential components for establishing an integrated computational-experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ML-Driven Materials Research

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Framework | Core ML Framework | Convert trained models from popular deep learning frameworks (Caffe, Keras, SKLearn) for device deployment [11] | iOS app integration for on-device predictions [11] |

| Data Management | FAIR Data Infrastructure | Ensure Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability of materials data [12] | Standardized data sharing across research institutions [12] |

| Automation Equipment | Liquid-Handling Robot | Precise dispensing of precursor solutions for high-throughput synthesis [4] | Multielement catalyst library preparation [4] |

| Characterization Tools | Automated Electrochemical Workstation | High-throughput measurement of catalytic activity and stability [4] | Fuel cell catalyst performance evaluation [4] |

| Structural Analysis | Automated Electron Microscopy | Microstructural characterization with minimal human intervention [4] | Grain size distribution analysis in alloys [9] |

| Synthesis Systems | Carbothermal Shock System | Rapid synthesis of materials through extreme temperature jumps [4] | Nanomaterial and catalyst preparation [4] |

| Experimental Monitoring | Computer Vision System | Visual monitoring of experiments for reproducibility assessment [4] | Detection of deviations in sample morphology or placement [4] |

Integrated Workflow for ML-Driven Materials Discovery

The full potential of machine learning in materials science emerges when multiple techniques are integrated into a cohesive discovery pipeline. This integrated approach combines computational predictions with experimental validation in a closed-loop system that continuously refines models based on new data.

Diagram 2: Integrated ML-driven discovery workflow

The workflow begins with clearly defined target properties, which guide generative models in proposing candidate materials with desired characteristics [10]. These candidates undergo computational screening through supervised learning models that predict key properties, followed by unsupervised clustering to identify promising material families and diverse candidates [10] [9]. Reinforcement learning then guides autonomous synthesis systems in producing selected candidates, with high-throughput characterization providing experimental validation [4]. Results feed back into the ML models, creating a continuous improvement cycle that refines predictions with each iteration [4].

This integrated approach has demonstrated remarkable success in various materials discovery campaigns. For example, in fuel cell catalyst development, such workflows have explored over 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests, leading to the discovery of multielement catalysts with record power density despite containing only one-fourth the precious metals of previous designs [4]. Similarly, in magnesium alloy research, combined ML and experimental approaches have accelerated the design of alloys with improved corrosion resistance and mechanical properties [9].

The future of ML-driven materials discovery lies in enhancing these integrated workflows through improved data standards, physics-informed model architectures, and more sophisticated autonomous laboratories. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to navigate the vast complexity of materials space efficiently, accelerating the development of advanced materials to address critical challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare.

Navigating the Vast Chemical Space with Unsupervised Learning and Dimensionality Reduction

The exploration of chemical space, encompassing all possible organic and inorganic molecules, is a fundamental challenge in materials science and drug discovery. With chemical libraries containing millions of compounds, researchers face significant cognitive and computational barriers in analyzing this wealth of data. This application note details how unsupervised learning and dimensionality reduction methods are enabling scientists to visualize, navigate, and extract meaningful patterns from these vast chemical datasets. We provide experimental protocols for implementing these techniques, supported by case studies and quantitative comparisons of their performance in real-world materials discovery applications. Framed within the broader context of machine learning-driven materials research, these methodologies are proving essential for identifying novel functional materials and bioactive compounds beyond the boundaries of previously charted chemical regions.

The "Big Data" era in medicinal chemistry and materials science presents new challenges for analysis, as modern computers can store and process millions of molecular structures, yet final decisions remain in human hands [13]. The ability of humans to analyze large chemical data sets is limited by cognitive constraints, creating a critical demand for methods and tools to visualize and navigate chemical space [13]. The chemical space of possible materials is astronomically large, with recent expansions through computational methods identifying 2.2 million stable crystal structures—an order-of-magnitude increase from previously known materials [14].

Within this context, unsupervised learning and dimensionality reduction techniques have emerged as essential tools for making sense of this complexity. These approaches allow researchers to project high-dimensional molecular descriptors into lower-dimensional representations that can be visually inspected and analyzed. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying clusters of compounds with similar properties, detecting outliers, and generating hypotheses for further exploration. As the field advances, these methods are evolving to address increasingly large and complex datasets, enabling the discovery of structurally novel molecules with desired properties [15] [13].

Computational Foundations

The Chemical Space Navigation Problem

Chemical space is fundamentally high-dimensional, with each potential molecule represented by hundreds of descriptors capturing structural, electronic, and physicochemical properties. The core challenge in navigating this space lies in the sheer combinatorial complexity of possible molecular structures. Recent advances have demonstrated that graph networks trained at scale can reach unprecedented levels of generalization, improving the efficiency of materials discovery by an order of magnitude [14]. This approach has led to the discovery of 2.2 million structures below the convex hull, many of which escaped previous human chemical intuition [14].

Key Algorithms and Approaches

Table 1: Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Chemical Space Analysis

| Method | Key Principles | Advantages in Chemical Context | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Linear projection that maximizes variance | Computational efficiency, interpretability of components | Limited capacity for nonlinear relationships |

| t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) | Preserves local neighborhoods in high-dim space | Effective cluster visualization, preserves local structure | Computational intensity, global structure loss |

| UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) | Preserves topological structure of data | Faster than t-SNE, better global structure preservation | Parameter sensitivity, theoretical complexity |

| Autoencoders | Neural network learns compressed representation | Handles nonlinearity, can generate new structures | Training complexity, data requirements |

| Generative Topographic Mapping (GTM) | Probabilistic alternative to SOM | Probabilistic framework, principled initialization | Computational demand for large datasets |

The selection of appropriate dimensionality reduction techniques depends on the specific objectives of the chemical space analysis. For initial exploration and visualization, UMAP has gained popularity due to its speed and ability to preserve both local and global structure [13]. For generative purposes, deep learning approaches such as autoencoders provide powerful frameworks for both compression and molecular generation [15] [14].

Recent advances have extended chemical space visualization beyond chemical compounds to include reactions and chemical libraries [13]. Deep generative modeling combined with chemical space visualization is paving the way for interactive exploration of chemical space, enabling researchers to navigate efficiently through regions of interest and identify promising candidates for synthesis and testing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chemical Space Mapping with UMAP

Purpose: To create a two-dimensional visualization of a high-dimensional chemical library for cluster identification and novelty assessment.

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical dataset (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC, Materials Project)

- Molecular descriptors (e.g., ECFP fingerprints, Mordred descriptors)

- Python environment with umap-learn, RDKit, pandas, numpy

- Computational resources (minimum 8GB RAM for datasets <100,000 compounds)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Load molecular structures from SDF or SMILES format

- Compute molecular descriptors or fingerprints

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Initialize UMAP with optimized parameters for chemical space

Fit transform the descriptor matrix

Visualization and Cluster Analysis:

- Create scatter plots colored by property values

- Identify clusters using HDBSCAN or DBSCAN

- Annotate clusters with molecular properties

Novelty Assessment:

- Calculate "unfamiliarity" metric based on reconstruction error [15]

- Identify regions of chemical space distant from training data

Troubleshooting:

- For large datasets (>1M compounds), consider using PCA initialization

- Adjust n_neighbors parameter to balance local and global structure

- For heterogeneous datasets, try different distance metrics (Euclidean, Jaccard, Cosine)

Protocol 2: Molecular Reconstruction for Generalizability Assessment

Purpose: To estimate model generalizability and identify out-of-distribution molecules using joint modeling of molecular property prediction with molecular reconstruction.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pre-trained molecular autoencoder

- Bioactivity dataset with known measurements

- Python with deep learning framework (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- GPU acceleration recommended

Procedure:

- Model Architecture Setup:

- Implement joint architecture with property prediction and reconstruction heads

- Use graph neural networks or sequence-based encoders

- Share encoder weights between both tasks

Training Protocol:

- Split data into training and validation sets using time-split or scaffold-split

Train with multi-task loss function:

Unfamiliarity Metric Calculation:

- Compute reconstruction error for new molecules

- Normalize error relative to training set distribution

- Set thresholds for familiarity classification

Validation:

- Test on known bioactivity datasets (e.g., kinase inhibitors)

- Correlate unfamiliarity with prediction accuracy drop

- Experimental validation of unfamiliar compounds [15]

Validation Results:

This approach has been experimentally validated for two clinically relevant kinases, discovering seven compounds with low micromolar potency and limited similarity to training molecules [15].

Visualization Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for chemical space navigation combining dimensionality reduction with generalizability assessment:

Chemical Space Navigation Workflow

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Chemical Space Exploration

Tool/Resource

Type

Function

Application Example

RDKit

Open-source cheminformatics toolkit

Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation

ECFP generation for similarity analysis

UMAP

Dimensionality reduction library

Non-linear dimensionality reduction

2D visualization of compound libraries

GNoME

Graph neural network model

Materials stability prediction

Discovery of novel crystal structures [14]

Materials Project

Database

Crystallographic and computational data

Training data for materials discovery models

ChEMBL

Database

Bioactivity data for drug-like molecules

Mapping bioactivity landscapes

Autoencoders

Neural network architecture

Learning compressed molecular representations

Molecular generation and novelty detection [15]

AlphaFold

Protein structure prediction

Predicting protein 3D structures

Target-informed chemical space navigation [16]

Applications in Materials Discovery and Drug Development

Case Study: Scaling Deep Learning for Materials Discovery

The Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME) project exemplifies the power of combining advanced machine learning with chemical space navigation. Through large-scale active learning, GNoME models have discovered 2.2 million crystal structures stable with respect to previous work, with 381,000 new entries on the updated convex hull [14]. This represents an order-of-magnitude expansion from all previous discoveries.

Key to this success was the development of models that generalize effectively beyond their training data. The GNoME approach demonstrated emergent out-of-distribution generalization, accurately predicting structures with five or more unique elements despite their omission from initial training [14]. This capability provides one of the first efficient strategies to explore this combinatorially large region of chemical space.

Table 3: Performance Metrics for GNoME Materials Discovery [14]

Metric

Initial Performance

Final Performance

Improvement Factor

Stability Prediction Hit Rate

<6%

>80%

>13x

Energy Prediction Error

21 meV/atom

11 meV/atom

1.9x

Stable Materials Discovered

48,000 (baseline)

421,000

8.8x

Novel Prototypes Identified

8,000 (baseline)

45,500

5.6x

Case Study: AI-Driven Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical applications, chemical space navigation enables more efficient exploration of potential drug candidates. AI technologies play an essential role in molecular modeling, drug design and screening, with demonstrated capabilities to lower costs and shorten development timelines [16]. For instance, Insilico Medicine developed an AI-driven drug discovery system that designed a novel drug candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in just 18 months, significantly faster than traditional approaches [16].

The "unfamiliarity" metric introduced through joint modeling approaches addresses a critical challenge in molecular machine learning: the inability of models to generalize beyond the chemical space of their training data [15]. By combining molecular property prediction with molecular reconstruction, this approach provides a quantitative measure to estimate model generalizability and identify promising compounds that are structurally novel yet likely to maintain desired properties.

Concluding Remarks

The navigation of chemical space through unsupervised learning and dimensionality reduction has transformed from a niche analytical technique to an essential component of modern materials discovery and drug development pipelines. As chemical libraries continue to grow—with projects like GNoME adding millions of new stable structures—these methods will become increasingly critical for identifying promising candidates for synthesis and testing [14].

Future directions in this field point toward more sustainable and efficient exploration of chemical spaces. Recent initiatives like the SusML workshop focus on developing Efficient, Accurate, Scalable, and Transferable (EAST) methodologies that minimize energy consumption and data storage while creating robust ML models [17] [18]. Similarly, the integration of human expertise through human-in-the-loop approaches and large language models shows promise for improving out-of-domain performance with reduced data requirements [19].

The ongoing challenge of navigating chemical space reflects the broader objectives of materials discovery and design using machine learning: to expand beyond the boundaries of human chemical intuition while providing interpretable, actionable insights that accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials and therapeutic agents.

Foundation models, characterized by their training on broad data using self-supervision at scale and their adaptability to a wide range of downstream tasks, represent a paradigm shift in artificial intelligence applications for materials science [20]. These models, built upon transformer architectures, decouple the data-hungry task of representation learning from specific downstream applications, enabling powerful predictive and generative capabilities even with limited labeled data [20]. Within materials informatics, this approach is accelerating the discovery and design of novel materials with tailored properties, offering solutions to long-standing challenges in sustainability, energy storage, and semiconductor technology [21].

Current State of Foundation Models in Materials Discovery

Architectural Foundations and Modalities

Foundation models for materials discovery employ diverse architectural strategies and molecular representations, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Encoder-only models, derived from the BERT architecture, excel at understanding and representing input data for property prediction tasks, while decoder-only models are optimized for generating new chemical entities [20]. The representation of molecular structures presents a fundamental challenge, with current approaches utilizing multiple modalities:

- Text-based Representations: SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) and SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings) convert molecular structures into text strings, enabling the application of natural language processing techniques [21]. While SMILES databases contain approximately 1.1 billion molecules, this representation can lose valuable 3D structural information and sometimes generates invalid molecules [21].

- Graph-based Representations: Molecular graphs capture the spatial arrangement of atoms and their bonds, preserving structural information at the cost of higher computational requirements [21].

- Experimental Data Modalities: Spectrograms and other experimental measurements provide empirical data on molecular behavior but may be incomplete or contain errors [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Representation Modalities in Foundation Models

| Representation Type | Example | Advantages | Limitations | Training Data Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text-based | SMILES, SELFIES | Leverages NLP techniques; large datasets available | Loses 3D structural information; may generate invalid molecules | ~1.1 billion molecules (SMILES) [21] |

| Graph-based | Molecular Hypergraphs | Captures spatial atom arrangements | Computationally intensive | ~1.4 million graphs [21] |

| 3D Structural | Crystal Graph Representations | Preserves spatial relationships | Limited dataset availability | Smaller than 2D representations [20] |

| Multimodal | Mixture of Experts | Combines strengths of multiple representations | Increased complexity | Varies by component models |

Data Extraction and Curation

The development of effective foundation models requires significant volumes of high-quality materials data, presenting substantial extraction and curation challenges. Chemical databases such as PubChem, ZINC, and ChEMBL provide structured information but are often limited by licensing restrictions, dataset size, and biased data sourcing [20]. Modern data extraction approaches must parse information from multiple modalities within scientific documents, including text, tables, images, and molecular structures [20].

Advanced extraction methodologies include:

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifies materials and compounds within text passages [20]

- Computer Vision Approaches: Vision Transformers and Graph Neural Networks extract molecular structures from images in documents [20]

- Specialized Algorithms: Tools like Plot2Spectra extract data points from spectroscopy plots, while DePlot converts visual representations into structured tabular data [20]

- Schema-based Extraction: Leverages recent advances in large language models for accurate property extraction and association [20]

Application Notes: Key Use Cases and Performance

Property Prediction

Foundation models demonstrate remarkable capabilities in predicting material properties from structure, enabling rapid screening of candidate materials. Current models predominantly utilize 2D representations (SMILES, SELFIES), though this approach omits potentially critical 3D conformational information [20]. An exception exists for inorganic solids like crystals, where property prediction models typically leverage 3D structures through graph-based or primitive cell feature representations [20].

The IBM FM4M project has demonstrated that multi-modal approaches significantly enhance prediction accuracy. Their Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture, which combines SMILES, SELFIES, and molecular graph representations, outperformed single-modality models on the MoleculeNet benchmark, achieving superior performance on both classification tasks (e.g., predicting toxicity) and regression tasks (e.g., predicting water solubility) [21].

Table 2: Property Prediction Performance of Foundation Models on MoleculeNet Benchmarks

| Model Architecture | Representation Modality | Classification Accuracy | Regression Performance | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-only (BERT-like) | SMILES/SELFIES | High for electronic properties | Moderate for quantum properties | Topological material identification [20] [6] |

| Decoder-only (GPT-like) | SMILES/SELFIES | Moderate | High for synthetic accessibility | Molecular generation [20] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Molecular Graphs | High for mechanically-relevant properties | High for formation energies | Crystal property prediction [20] |

| Multi-modal MoE | Combined embeddings | Highest overall | Highest overall | Broad applicability across tasks [21] |

Molecular Generation and Inverse Design

Beyond property prediction, foundation models enable inverse design—generating novel molecular structures with desired properties. Decoder-only architectures are particularly suited to this task, sequentially generating molecular representations token-by-token [20]. These models can be conditioned to explore specific regions of the property distribution through alignment processes, ensuring generated structures exhibit desired characteristics such as improved synthesizability or chemical correctness [20].

Expert-Informed Discovery

The ME-AI (Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence) framework demonstrates how expert intuition can be translated into quantitative descriptors through foundation models. In one implementation, researchers trained a Gaussian-process model on 879 square-net compounds using 12 experimental features, combining electronic structure information (electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count) with structural parameters [6]. The model not only recovered the known structural "tolerance factor" descriptor but also identified hypervalency as a decisive chemical factor in identifying topological semimetals [6]. Remarkably, the model demonstrated transferability, correctly classifying topological insulators in rocksalt structures despite being trained only on square-net topological semimetal data [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multi-modal Foundation Model Training

Purpose: To train a foundation model that leverages multiple molecular representations for enhanced materials property prediction.

Materials and Methods:

- Data Collection:

Pre-training:

Multi-modal Fusion:

- Implement Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture with router algorithm

- Train router to selectively activate modality-specific "experts" based on task requirements

- Fine-tune on downstream tasks using labeled datasets

Validation:

- Evaluate on MoleculeNet benchmark tasks

- Compare performance against single-modality baselines

- Analyze expert activation patterns to understand modality contributions [21]

Protocol: Automated Materials Discovery with CRESt Platform

Purpose: To implement a closed-loop materials discovery system integrating foundation models with robotic experimentation.

Materials and Methods:

- System Setup:

- Deploy liquid-handling robot for sample preparation

- Integrate carbothermal shock system for rapid material synthesis

- Set up automated electrochemical workstation for testing

- Install characterization equipment (automated electron microscopy, optical microscopy)

- Configure computer vision system with cameras for experiment monitoring [4]

Workflow Implementation:

- Natural language interface for researcher instructions

- Knowledge embedding from scientific literature using foundation models

- Principal component analysis in knowledge embedding space to reduce search dimensionality

- Bayesian optimization in reduced space for experiment design [4]

Active Learning Cycle:

- Robotically synthesize materials based on model recommendations

- Automatically characterize structure and test performance

- Feed experimental results back into foundation models

- Incorporate human feedback via natural language [4]

Validation:

- Track reproducibility across experimental iterations

- Monitor system-identified issues and suggested corrections

- Evaluate final material performance against project objectives

Visualization Diagrams

Foundation Model Architecture for Materials Informatics

CRESt Automated Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Foundation Model Applications

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL, ICSD | Training data for foundation models; reference for validation | Large-scale structured information; variable quality and completeness [20] |

| Representation Libraries | RDKit, SMILES, SELFIES | Molecular representation and conversion | Standardized formats; enable NLP approaches to chemistry [21] |

| Pre-trained Models | SMILES-TED, SELFIES-TED, MHG-GED | Transfer learning for specific materials tasks | Reduced data requirements; improved performance on specialized tasks [21] |

| Benchmark Datasets | MoleculeNet, Materials Project | Model evaluation and comparison | Standardized tasks; enable performance comparisons [21] |

| Automation Equipment | Liquid-handling robots, Automated electrochemical workstations | High-throughput experimentation | Enable rapid experimental validation; reduce human error [4] |

| Characterization Tools | Automated electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction | Structural analysis of synthesized materials | Provide ground truth data for model validation [4] |

Foundation models represent a transformative approach to materials informatics, leveraging pre-trained transformers to accelerate property prediction, molecular generation, and experimental design. The integration of multiple molecular representations through architectures like Mixture of Experts demonstrates enhanced performance across diverse tasks, while platforms such as CRESt showcase the potential for closed-loop discovery systems combining AI with robotic experimentation. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to significantly reduce the time and cost associated with materials development, addressing critical challenges in sustainability, energy, and electronics.

The integration of public materials databases and machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the field of materials science, creating a new paradigm for accelerated materials discovery and design. Foundational databases like the Materials Project and AFLOW provide vast, pre-computed datasets of material properties, serving as the essential fuel for data-driven research. These resources provide the high-quality, consistently calculated data required to train, benchmark, and validate ML models, enabling the prediction of novel materials and properties with unprecedented speed. This application note details the methodologies for effectively leveraging these databases within an ML-driven research workflow, providing protocols for data access, featurization, and model benchmarking to empower researchers in pushing the frontiers of materials informatics.

The Materials Project and AFLOW represent two pillars of the materials genomics initiative, both offering immense volumes of data but with distinct emphases and integrated tooling. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of their core offerings.

Table 1: Core Features of Public Materials Databases

| Feature | Materials Project (MP) | AFLOW++ Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Accelerate materials design by computing properties of inorganic crystals and molecules [22]. | Autonomous materials design via an interconnected collection of algorithms and workflows [23]. |

| Data Scope | Pre-computed properties for materials and molecules; includes data from other sources in MatBench [24]. | High-throughput calculation of structural, electronic, thermodynamic, and thermomechanical properties [23]. |

| Sample Datasets | MatBench curates datasets from 312 to 132,000 entries; includes both experimental and calculated data [24]. | Heavily used for disordered systems, high-entropy ceramics, and bulk metallic glasses [23]. |

| Key Properties | Electronic, thermal, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties [24]. | Stability/synthesizability, electronic structure, elastic constants, and thermomechanical properties [23]. |

| Unique Tools | MatBench benchmarking suite; integration with Matminer for featurization [24]. | PAOFLOW (electronic analysis), AEL/AGL (elasticity/Gibbs), modules for disorder (POCC, QCA) [23]. |

| Interoperability | Data accessible via API, Python package, and direct download [24]. | Prioritizes interoperability and consistency; integrated with VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, and others [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Driven Materials Research

Protocol 1: Bulk Data Acquisition via OPTIMADE API

Acquiring large, clean datasets is the critical first step in any ML pipeline. The OPTIMADE API provides a standardized interface for querying multiple materials databases, including AFLOW.

Application: Benchmarking a Bayesian Optimization framework for crystal structures [25].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- OPTIMADE Client (

optimadePython package): A community-standard API for accessing materials data across different providers. - ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment): A Python package for working with atoms and structures; used for file format conversion.

- AFLOW Provider: One of the primary OPTIMADE providers, offering access to the AFLOW database's calculated properties.

Methodology:

- Client Initialization: Initialize the

OptimadeClientand target the AFLOW provider to restrict the data source.

Query Filtering: Apply a filter to select records with specific known properties, such as heat capacity at 300K.

Pagination Handling: The client's

getmethod handles pagination automatically. Extract the structure data from the result object.Data Conversion and Storage: Iterate through the returned structures, convert them to a standard format (e.g., CIF) using an adapter, and save them to disk alongside a CSV file logging the target property.

Note: Be mindful of potential download limits (e.g., 1,000 records per query) [25]. For larger datasets, implement looping with pagination tokens or use provider-specific bulk download options where available.

Protocol 2: End-to-End ML Model Benchmarking with MatBench

MatBench provides a standardized framework for evaluating and comparing the performance of ML models on various materials property prediction tasks, similar to the role of ImageNet in computer vision [24].

Application: Objectively evaluating a new graph neural network model for predicting material band gaps.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- MatBench Python package: Provides easy access to curated benchmark datasets.

- Matminer: A Python toolbox for data featurization and mining, often used in conjunction with MatBench.

- Automatminer: An "AutoML" pipeline that automates featurization, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning.

Methodology:

- Dataset Selection: Load a specific benchmark task from MatBench. For band gap prediction, the

MatBench_mp_gapdataset is appropriate.

- Model Definition: Define your custom ML model (e.g., a PyTorch or scikit-learn model). The model must adhere to the scikit-learn estimator API.

Benchmark Execution: Run the benchmark, which automatically handles data splitting into training and test sets.

Performance Analysis and Submission: Use MatBench's built-in functions to analyze model performance across all folds and datasets. The results can be formally submitted to the public MatBench leaderboard for comparison with state-of-the-art models [24].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative process of model benchmarking and improvement.

Community Benchmarks and Emerging Frontiers

The field is rapidly evolving with the establishment of robust benchmarks and a focus on next-generation challenges. The table below summarizes key benchmarking and community initiatives.

Table 2: Key Benchmarks and Community Initiatives in AI for Materials

| Initiative | Primary Focus | Role in ML Research |

|---|---|---|

| MatBench [24] | Materials property prediction. | Provides a suite of curated datasets for training and a public leaderboard for objective model comparison, defining state-of-the-art. |

| MLIP Arena [26] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials. | An open benchmark platform for ensuring fairness and transparency in evaluating interatomic potentials. |

| AI4Mat Workshop Series (ICLR & NeurIPS 2025) [26] [27] | Foundation models, representations, and benchmarking. | A leading venue for discussing limitations of current benchmarks and fostering development of methods with real-world impact. |

A central theme in current research is moving beyond traditional benchmarks to address core technical challenges. As highlighted in recent workshops, the community is focused on two key questions:

- How Do We Build a Foundation Model for Materials Science? There is growing interest in developing large-scale, pre-trained models that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream materials tasks [26].

- What are Next-Generation Representations of Materials Data? Research continues into creating more powerful and data-efficient representations of crystal structures, molecules, and their multi-modal data (e.g., text, images) [26].

Essential Software Toolkit

A robust software ecosystem has emerged to support every stage of the ML research workflow, from data access to model deployment.

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for ML-Based Materials Discovery

| Tool | Language | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFLOW++ [23] | C++/Python | High-throughput generation and calculation of materials properties. | Automating the input generation and calculation of elastic constants for a new class of high-entropy carbides. |

| Matminer [24] | Python | Featurization of materials primitives (crystals, molecules) and dataset creation. | Converting a set of CIF files into a feature matrix of composition and structural descriptors for model training. |

| Automatminer [24] | Python | Automated machine learning (AutoML) pipeline for materials property prediction. | Rapidly prototyping and deploying a predictive model for bulk modulus with minimal human intervention. |

| PAOFLOW [23] | Python | Post-processing of electronic structures to compute advanced properties (e.g., transport, topological). | Calculating the anomalous Hall conductivity from a set of first-principles calculation results. |

The logical relationship and data flow between these core tools, databases, and the researcher are visualized below.

From Prediction to Creation: ML Methodologies for Property Prediction and Generative Design

The discovery and development of new functional materials are pivotal for technological progress, from renewable energy systems to advanced electronics and pharmaceuticals. Traditional approaches relying on trial-and-error experimentation and first-principles quantum mechanical calculations, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), are often computationally intensive and time-consuming, creating a significant bottleneck [1]. Machine learning (ML) now offers a transformative alternative, dramatically accelerating the prediction of material properties—from fundamental crystal stability to complex electronic behaviors—by learning structure-property relationships from existing data [28] [1]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to screen vast chemical spaces in silico and identify promising candidates with targeted properties orders of magnitude faster than conventional methods [29]. These data-driven strategies are establishing a new foundation for innovation across materials science.

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for employing ML to predict two cornerstone classes of material properties: crystal stability and electronic structure. We summarize benchmark performance data for state-of-the-art models, outline structured experimental workflows, and introduce essential software tools. The content is framed within a broader thesis on materials discovery, aiming to equip researchers with practical methodologies to integrate ML into their own development pipelines.

The following tables consolidate key performance metrics for contemporary ML models, providing a benchmark for method selection and expectation setting.

Table 1: Performance of Crystal Stability Prediction Models

| Model / Framework | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Primary Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Interatomic Potentials (UIPs) [30] | Accuracy in identifying stable crystals | Surpassed other methodologies in accuracy and robustness | Matbench Discovery [30] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) + Bayesian Optimization [31] | Success in predicting stable structures | Reduced prediction time while ensuring stability | Materials Project [31] |

| Matbench Discovery Framework [30] | False-positive rate for stable crystals | Highlights risk of high false-positive rates even for accurate regressors | Matbench Discovery [30] |

Table 2: Performance of Electronic Property Prediction Models

| Model / Framework | Property Predicted | Performance / Speed Gain | Primary Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| MALA (Materials Learning Algorithms) [29] | Local Density of States (LDOS), Electronic Density | Up to 3 orders of magnitude speedup; Enabled 100,000+ atom systems (infeasible for DFT) | Custom DFT (e.g., Beryllium) [29] |

| MEHnet (Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian) [32] | Multiple electronic properties (e.g., excitation gap, polarizability) | CCSD(T)-level accuracy on larger molecules; Outperformed DFT counterparts | Hydrocarbon molecules [32] |

| PDD-Transformer [33] | Various material properties | Accuracy on par with state-of-the-art; Several times faster in training/prediction | Materials Project, Jarvis-DFT [33] |

| Structure2Property Model [34] | Band gap, Fermi level energy, etc. | Band gap accuracy exceeded previously published results | Not Specified [34] |

Protocols for Key Prediction Tasks

Protocol 1: Predicting Crystal Stability Using a GNN and Bayesian Optimization

This protocol details a method for identifying thermodynamically and dynamically stable crystal structures using a Graph Neural Network (GNN) for formation energy prediction and Bayesian Optimization (BO) for structure search [31].

3.1.1 Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Tools for Stability Prediction

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Model | Maps crystal structure (atomic types, positions, bonds) to a formation energy value. |

| Lennard-Jones Potential Calculator | Empirical formula to assess dynamic stability; values approaching zero indicate greater stability. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | Efficiently navigates the vast structure space to find configurations that minimize the GNN-predicted energy and LJ potential. |

| Contact Map Analysis | A post-screening tool that analyzes atomic bonding patterns to further filter for structurally sound candidates. |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preparation & Model Training: Curate a dataset of known crystal structures with their DFT-calculated formation energies (e.g., from the Materials Project [31]). Train the GNN model to accurately predict the formation energy (\Delta H_f) of a crystal given its structural input.

- Define Search Space: Delineate the chemical and configurational space of interest (e.g., specific elements, permissible crystal systems, and ranges for lattice parameters).

- Bayesian Optimization Loop: a. Proposal: The BO algorithm proposes a batch of new candidate crystal structures. b. Evaluation: For each candidate, use the pre-trained GNN to predict its formation energy and calculate its Lennard-Jones potential. c. Objective Function: Compute a combined objective function that penalizes high formation energy and large absolute values of the Lennard-Jones potential. d. Update: The BO algorithm uses these results to update its internal surrogate model, refining its understanding of the structure-property landscape. e. Iterate: Repeat steps a-d for a predefined number of iterations or until convergence criteria are met (e.g., no improvement in the objective function for N consecutive iterations).

- Stability Screening & Validation: Select the top candidate structures from the BO output. Perform contact map analysis to check for reasonable atomic connectivity. Finally, validate the thermodynamic stability of the final shortlisted candidates using high-fidelity DFT calculations.

Protocol 2: Large-Scale Electronic Structure Prediction with MALA

This protocol describes using the MALA framework to predict the electronic structure of large-scale systems (e.g., >100,000 atoms), which are intractable for standard DFT [29].

3.2.1 Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Tools for Electronic Structure Prediction

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Bispectrum Descriptors | Atomic environment descriptors that encode the positions of neighboring atoms around a point in space, providing a rotationally invariant representation. |

| Feed-Forward Neural Network | Learns the mapping from bispectrum descriptors to the Local Density of States (LDOS) at a point in space and energy. |

| MALA Software Package | An end-to-end workflow integrating LAMMPS (descriptor calc.), PyTorch (NN), and Quantum ESPRESSO (post-processing). |

| Local Density of States (LDOS) | The central quantum mechanical quantity predicted by MALA; used to derive electronic density, total energy, and forces. |

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Generate Training Data with DFT: Perform DFT calculations on small, representative simulation cells (e.g., 256 atoms) to obtain the ground-truth LDOS across a real-space grid and energy range.

- Calculate Descriptors: For each point in the real-space grid of the training data, compute the bispectrum coefficients (B(J, \mathbf{r})) that describe the local atomic environment using LAMMPS.

- Train the Neural Network: Train a feed-forward neural network to perform the mapping (\tilde{d}(\epsilon, \mathbf{r}) = M(B(J, \mathbf{r}))), where (\tilde{d}) is the predicted LDOS.

- Prediction on Large-Scale System: a. Input: Provide the atomic coordinates of the large-scale system (e.g., 131,072 atoms). b. Descriptor Calculation: Compute bispectrum descriptors for every point on the real-space grid of the target system. c. LDOS Prediction: Use the trained network to predict the LDOS at each point. d. Post-Processing: Derive desired observables (electronic density (\rho(\mathbf{r})), density of states (D(\epsilon)), total free energy (A)) from the predicted LDOS.

- Analysis: Analyze the results, such as identifying charge redistribution around defects or comparing energies of different configurations.

Table 5: Critical Software, Datasets, and Models for the Materials Researcher

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matbench Discovery [30] | Benchmarking Framework | Standardized evaluation of ML models for predicting inorganic crystal stability. | Provides community-agreed metrics to compare and select the best stability models. |

| MALA [29] | Software Package | Predicts electronic structures (LDOS) at scales intractable for DFT. | Essential for electronic property prediction in large systems like disordered alloys or extended defects. |

| MEHnet [32] | ML Model (Equivariant GNN) | Predicts multiple electronic properties with coupled-cluster theory (CCSD(T)) accuracy. | High-accuracy prediction of properties for molecular systems and potential materials. |

| PDD-Transformer [33] | ML Model (Transformer) | Uses generically complete isometry invariants for crystal property prediction. | Fast and accurate property prediction that inherently respects crystal symmetries. |

| Materials Project [30] [31] [33] | Database | Repository of computed crystal structures and properties for thousands of materials. | A primary source of data for training and validating ML models. |

| AutoGluon, TPOT [1] | Software (AutoML) | Automates the process of model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and feature engineering. | Accelerates the development of robust ML pipelines without requiring deep ML expertise. |

The integration of machine learning into materials science represents a fundamental shift in how we discover and design new substances. As demonstrated by the protocols and data herein, ML models can now reliably predict properties ranging from crystal stability—the foundation of synthesizability—to complex electronic structures, doing so with unprecedented speed and scale. Frameworks like Matbench Discovery ensure rigorous model evaluation, while emerging tools like MALA and MEHnet push the boundaries of what is computationally possible. For researchers, the path forward involves leveraging these tools in hybrid workflows, where ML rapidly screens vast chemical spaces to identify promising candidates for further validation by high-fidelity computational methods or experiment. This synergistic approach is poised to dramatically accelerate the development of next-generation functional materials for energy, electronics, and medicine.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Modeling Complex Crystalline Structures

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent one of the fastest-growing classes of machine learning models with particular relevance for chemistry and materials science. They operate directly on a graph or structural representation of molecules and materials, providing full access to all relevant information required to characterize materials [35] [36]. For crystalline materials, GNNs have emerged as transformative tools that enable accurate prediction of material properties, accelerate simulations, and design new structures with targeted functionalities [1].

The fundamental advantage of GNNs in materials science stems from their ability to naturally represent crystalline structures as graphs, where atoms serve as nodes and chemical bonds as edges. This representation allows GNNs to leverage both the intrinsic features of atoms and the complex connectivity patterns within crystal structures [35]. Modern GNN frameworks can process these graph-structured inputs to uncover complex patterns and relationships between material structures and properties, which has proven vital for characterizing crystalline materials and accelerating discovery cycles [37].

Foundational Concepts and Data Representations

Message Passing Framework