How AI-Driven Labs Are Accelerating Materials Discovery 10x Faster

This article explores the transformative impact of artificial intelligence on materials discovery, a critical field for biomedical and clinical research.

How AI-Driven Labs Are Accelerating Materials Discovery 10x Faster

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of artificial intelligence on materials discovery, a critical field for biomedical and clinical research. It details how AI-driven labs, from self-driving robotic platforms to advanced foundation models, are fundamentally reshaping R&D. The content covers the foundational technologies powering this shift, examines specific methodological applications and workflows, addresses key challenges and optimization strategies, and validates the performance and comparative advantages of these AI systems. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis provides a comprehensive overview of how AI is enabling the rapid discovery and development of novel materials for next-generation therapies and medical devices.

The AI Paradigm Shift: From Trial-and-Error to Intelligent Design in Materials Science

The pursuit of new materials with tailored properties represents one of the most significant challenges in modern science and engineering. The fundamental problem lies in the astronomical size of the materials design space, which encompasses 10108 potential organic molecules alone [1]. This combinatorial explosion arises from the virtually infinite permutations of elemental compositions, atomic arrangements, processing parameters, and synthesis conditions. Traditional experimental approaches, which rely on manual, serial, and human-intensive workflows, are fundamentally inadequate for effectively navigating this immense search space. The materials science community has consequently faced decades-long struggles to find solutions to critical energy and sustainability problems, as serendipitous discovery remains inefficient and unpredictable [2].

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), coupled with advanced computational resources and robotic automation, has initiated a paradigm shift in materials discovery. This whitepaper examines how AI-driven laboratories are transforming the approach to this core problem by deploying intelligent systems that can efficiently explore combinatorial spaces orders of magnitude faster than human researchers. These systems integrate multimodal data integration, active learning algorithms, and autonomous experimentation to accelerate the entire discovery pipeline from initial hypothesis to validated material [3]. By framing this discussion within the context of a broader thesis on AI-driven acceleration, we will explore the specific methodologies, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions that are making this transformation possible.

AI Methodologies for Combinatorial Space Navigation

Core Computational Strategies

AI-driven materials discovery employs several sophisticated computational strategies to manage the complexity of combinatorial spaces. These approaches move beyond traditional high-throughput screening by incorporating intelligent search and optimization.

Table 1: AI Methodologies for Combinatorial Space Navigation

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Advantage | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Suggests optimal next experiments based on existing data [2] | Efficiently balances exploration of new regions with exploitation of promising areas [1] | MIT's CRESt system for fuel cell catalyst discovery [2] |

| Genetic Algorithms | Evolves material recipes through selection, crossover, and mutation operations [4] | Discovers synergistic combinations and "underestimated" components [4] | Polymer mixture optimization identifying non-intuitive formulations [4] |

| Gaussian Process Models | Learns underlying patterns from expert-curated data to identify descriptive features [5] | Incorporates chemistry-aware kernels for improved transferability across material classes [5] | Materials Expert-AI (ME-AI) framework for topological semimetals [5] |

| Generative Models | Creates novel material structures satisfying specified design constraints [3] | Enables inverse design where materials are generated to meet exact property requirements [3] | MatterGen for inorganic materials; SCIGEN for quantum materials with specific lattice geometries [6] |

| Rule-Based Constraint Systems | Ensures generated structures adhere to fundamental physical and chemical principles [6] | Prevents generation of unrealistic materials, focusing search on feasible regions of chemical space [6] | SCIGEN code system enforcing geometric rules for quantum material discovery [6] |

Active Learning and Closed-Loop Systems

A critical innovation in AI-driven materials discovery is the implementation of active learning frameworks that create closed-loop systems. These systems continuously integrate computational predictions with experimental validation, forming iterative cycles of hypothesis generation and testing. The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform developed at MIT exemplifies this approach, using multimodal feedback from literature, experimental results, and human expertise to design subsequent experiments [2]. This creates an adaptive system that progressively focuses on the most promising regions of the materials space, dramatically reducing the number of experiments required to identify optimal candidates.

The active learning process typically begins with the algorithm selecting promising candidates from the vast design space based on available data and predictive models. Robotic systems then synthesize and characterize these candidates, with the results fed back into the AI models to refine their predictions [2] [4]. This closed-loop operation enables intelligent navigation through combinatorial space rather than exhaustive screening, which would be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming even with automated equipment.

Experimental Protocols in AI-Driven Materials Discovery

Protocol 1: CRESt System for Fuel Cell Catalyst Discovery

The CRESt platform demonstrates a comprehensive experimental protocol for navigating compositional space in functional materials. The system was specifically applied to discover a high-performance, low-cost catalyst for direct formate fuel cells [2].

Methodology Details:

Initial Setup and Design Space Definition: The system begins with up to 20 precursor molecules and substrates, defining a multidimensional compositional space [2].

Knowledge Embedding and Space Reduction: Scientific literature and database information create representations of material recipes in a high-dimensional knowledge space. Principal component analysis (PCA) then reduces this to a lower-dimensional search space capturing most performance variability [2].

Bayesian Optimization in Reduced Space: The system employs Bayesian optimization within the reduced space to design experiments that balance exploration of new regions with exploitation of promising areas [2].

Robotic Synthesis and Characterization: A liquid-handling robot prepares formulations, while a carbothermal shock system enables rapid synthesis. Automated characterization includes electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction [2].

Performance Testing: An automated electrochemical workstation tests the performance of synthesized materials for the target application [2].

Multimodal Feedback Integration: Results from characterization and testing are combined with literature knowledge and human feedback to augment the knowledge base and redefine the search space for subsequent iterations [2].

Outcomes: In a three-month campaign exploring over 900 chemistries and conducting 3,500 electrochemical tests, CRESt discovered an eight-element catalyst that delivered a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar compared to pure palladium, while using only one-fourth of the precious metals of previous devices [2].

Protocol 2: ME-AI for Topological Quantum Materials

The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework addresses the challenge of discovering materials with specific quantum properties, where the design space is constrained by complex electronic structure requirements [5].

Methodology Details:

Expert-Guided Data Curation: Domain experts curate a specialized dataset of 879 square-net compounds characterized by 12 experimentally accessible primary features, including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and structural parameters [5].

Expert Labeling: Materials are labeled based on experimental band structure measurements (56% of database), chemical logic applied to related compounds (38%), or analogy to characterized materials (6%) [5].

Dirichlet-based Gaussian Process Modeling: A Gaussian process model with a chemistry-aware kernel learns the relationships between primary features and the target property (topological semimetals in this case) [5].

Descriptor Discovery: The model identifies emergent descriptors that effectively predict the target properties, recovering known expert intuition (tolerance factor) while discovering new decisive chemical levers like hypervalency [5].

Transferability Validation: The model's generalizability is tested by applying it to different material systems (e.g., topological insulators in rocksalt structures) without retraining [5].

Outcomes: ME-AI successfully reproduced established expert rules for identifying topological semimetals while revealing hypervalency as a decisive chemical lever. Remarkably, the model demonstrated transferability across material classes, correctly classifying topological insulators in rocksalt structures despite being trained only on square-net compounds [5].

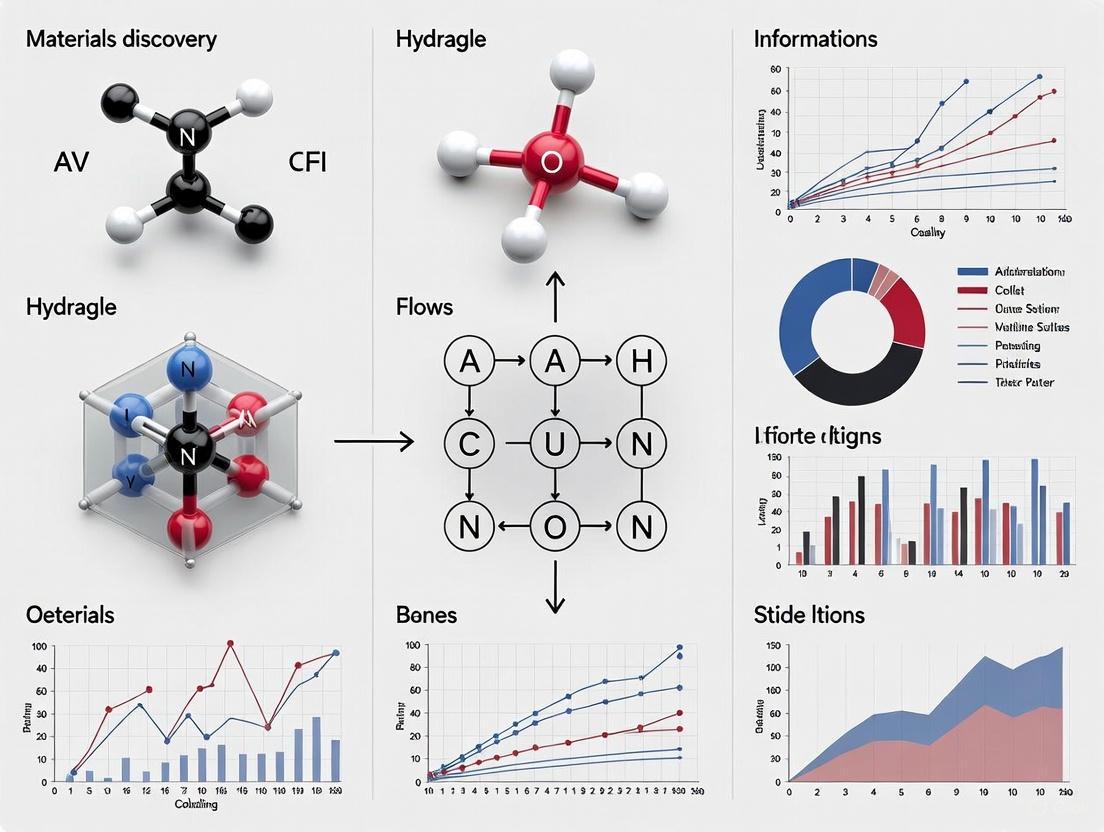

Workflow Visualization: AI-Driven Materials Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of an AI-driven materials discovery platform, synthesizing elements from the CRESt and ME-AI systems:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

AI-driven materials discovery relies on specialized research reagents and instrumentation systems that enable high-throughput experimentation and characterization. The following table details key components of these experimental platforms:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Instrumentation for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Handling Robots | Precisely dispenses liquid precursors for consistent sample preparation across large combinatorial spaces [2] | Forms core of CRESt system for fuel cell catalyst discovery, enabling testing of 900+ chemistries [2] |

| Carbothermal Shock Systems | Enables rapid synthesis of materials through extreme thermal processing for rapid screening of compositional space [2] | Used in CRESt platform for rapid synthesis of catalyst libraries [2] |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstations | Performs high-throughput electrochemical characterization to evaluate functional performance [2] | Conducted 3,500 tests in CRESt project to assess fuel cell catalyst performance [2] |

| Automated Electron Microscopy | Provides structural and compositional characterization without manual operation [2] | Integrated into CRESt for microstructural analysis of synthesized catalysts [2] |

| Square-Net Compound Libraries | Curated sets of materials with specific structural motifs for targeted quantum material discovery [5] | 879 compounds used in ME-AI framework for topological semimetal identification [5] |

| Multielement Precursor Libraries | Comprehensive collections of elemental sources for combinatorial exploration of complex compositions [2] | Enabled CRESt to discover 8-element catalyst with synergistic performance [2] |

| Polymer Component Libraries | Diverse sets of polymer building blocks for formulating advanced functional materials [4] | Platform tested 700+ daily polymer mixtures for protein stabilization, battery electrolytes, drug delivery [4] |

The integration of artificial intelligence with automated experimentation is fundamentally transforming how researchers navigate the vast combinatorial space of materials. By implementing sophisticated algorithms like Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms, and Gaussian processes within closed-loop systems that incorporate robotic synthesis and characterization, AI-driven laboratories can efficiently explore regions of materials space that were previously inaccessible. The experimental protocols and research reagents detailed in this whitepaper provide a framework for accelerating the discovery of solutions to critical energy, sustainability, and technological challenges that have plagued the materials community for decades. As these technologies continue to mature, with improvements in model interpretability, data standardization, and human-AI collaboration, they promise to turn the formidable challenge of combinatorial complexity into a manageable process of intelligent exploration and discovery.

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and data science. Traditional materials discovery has been a time-consuming and resource-intensive process, often relying on manual experimentation and serendipitous findings. AI-driven labs, also known as self-driving laboratories, represent a paradigm shift that accelerates the discovery pipeline from years to months or even days by integrating robotic equipment for high-throughput synthesis and testing with AI models that plan experiments and interpret results [2] [3]. These systems function as autonomous research assistants, capable of making intelligent decisions about which experiments to perform next based on real-time analysis of incoming data. This convergence is poised to deliver solutions to pressing global challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare by rapidly identifying advanced functional materials with tailored properties [7] [8].

Core Architecture of an AI-Driven Lab

The architecture of an AI-driven lab creates a closed-loop system where AI models and robotic hardware work in concert to autonomously execute the scientific method. This integrated framework enables continuous learning and optimization, dramatically speeding up the research cycle.

The Workflow of an AI-Driven Lab

The operation of a self-driving lab follows an iterative, closed-loop process. The cycle begins with an AI model, often using a technique like Bayesian optimization, which proposes a candidate material or synthesis condition based on prior knowledge, which can include scientific literature, existing databases, and results from previous experiments [2]. Robotic systems then execute the physical experimentation, handling tasks such as pipetting, mixing precursors, and operating synthesis reactors [2] [9]. During and after synthesis, integrated analytical instruments characterize the resulting material's structure and performance. The collected data—which can include microstructural images, spectral data, and performance metrics—is then fed back into the AI model, which uses the new information to refine its understanding and propose the next most informative experiment [3]. This creates a tight feedback loop where the system learns efficiently from each data point, rapidly honing in on optimal solutions.

Enabling Technologies and Infrastructure

AI and Machine Learning Models: The "brain" of the lab uses various AI approaches. Active learning algorithms, particularly Bayesian optimization, guide the experimental sequence by balancing exploration of the unknown with exploitation of promising leads [2]. Generative models can propose entirely new material structures or synthesis pathways, while machine-learning-based force fields enable accurate and large-scale atomic simulations at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional methods [3]. Multimodal models are crucial, as they can process diverse data types—including text, images, and numerical data—to form a comprehensive knowledge base [2].

Robotics and Automation (The Hardware): The physical layer consists of automated systems for synthesis and characterization. Liquid-handling robots automatically prepare samples by mixing precursors in precise ratios [2]. Continuous flow reactors enable rapid synthesis and real-time monitoring of reactions, with advanced systems using "dynamic flow" methods to collect data continuously rather than in single snapshots [8]. Automated characterization tools, such as electron microscopes and electrochemical workstations, analyze the synthesized materials without human intervention [2] [9].

Data Infrastructure and Compute: Robust data systems are the backbone of AI-driven labs. High-performance computing (HPC) resources are needed to train and run complex AI models and simulations [7] [9]. Standardized data formats and federated learning capabilities are essential for managing and sharing data across different facilities and instruments while maintaining data security [7]. Platforms like Distiller, used at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, stream data directly from microscopes to supercomputers for near-instantaneous analysis, enabling real-time decision-making [9].

Quantitative Acceleration of Discovery

The impact of AI-driven labs is quantifiable across several key performance metrics, demonstrating a dramatic increase in research efficiency and a significant reduction in resource consumption.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Labs vs. Traditional Methods

| Metric | Traditional Methods | AI-Driven Labs | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Timeline | Years | Months/Weeks [8] | 10x faster [8] |

| Data Throughput | Single, steady-state data points | Continuous data streaming (e.g., every 0.5 seconds) [8] | >10x more data [8] |

| Chemical Consumption & Waste | High (manual processes) | Fraction of traditional use [8] | Significant reduction [8] |

| Experimental Reproducibility | Prone to human error | High (automated, monitored protocols) [2] | Substantially improved [2] |

A concrete example of this acceleration is the "Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists (CRESt)" system developed at MIT. In one project, it explored over 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests in just three months, leading to the discovery of a multi-element catalyst that delivered a record power density for a specific type of fuel cell [2]. Similarly, North Carolina State University researchers demonstrated that their self-driving lab using a dynamic flow approach could identify optimal material candidates on the very first attempt after its initial training period [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Discovery of a Fuel Cell Catalyst

The following protocol is based on the operations of the MIT CRESt system, which successfully discovered a high-performance, multi-element fuel cell catalyst [2]. This provides a concrete example of how an AI-driven lab functions in practice.

Objective

To autonomously discover and optimize a solid-state catalyst for a direct formate fuel cell that maximizes power density while minimizing the use of precious metals.

Research Reagent Solutions & Key Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Palladium (Pd) Precursors | Serves as the primary, expensive catalytic metal; the system aims to find alternatives and reduce its load. |

| Transition Metal Precursors (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni) | Lower-cost elements incorporated to create an optimal coordination environment and reduce catalyst cost. |

| Formate Fuel | The energy source for the fuel cell; its electrochemical oxidation is the reaction being catalyzed. |

| Electrolyte Membrane | Facilitates ion conduction within the fuel cell while separating the anode and cathode compartments. |

| Carbon Substrate | Provides a high-surface-area support for the catalyst nanoparticles, ensuring good electrical conductivity. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Problem Formulation & Initialization: A human researcher defines the search space by specifying a set of potential precursor elements (up to 20) and the high-level goal: to maximize power density per dollar of a fuel cell electrode [2].

AI-Driven Experimental Design: The system's active learning algorithm begins. It first creates a "knowledge embedding" of potential recipes by searching through scientific literature and databases. It then uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce this vast search space to a manageable size that captures most performance variability. Bayesian optimization in this reduced space suggests the first set of material compositions to test [2].

Robotic Synthesis & Characterization:

- A liquid-handling robot precisely dispenses the selected precursor solutions into a reaction vessel [2].

- A carbothermal shock system or similar automated reactor performs the rapid synthesis of the target material [2].

- The synthesized powder is then transferred to an automated electrochemical workstation where it is fabricated into an electrode and tested for its catalytic performance [2].

- Automated electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction characterize the material's microstructure and crystal phase [2].

Multimodal Data Integration & Analysis: The system aggregates all data—performance metrics from the electrochemical test, microstructural images, and literature context. Computer vision and visual language models monitor the experiments via cameras, checking for issues like sample misplacement and suggesting corrections [2].

AI Analysis and Next Experiment Selection: The newly acquired data is fed back into the large language and active learning models. The AI updates its knowledge base, refines its model of the material property landscape, and selects the next most promising experiment to perform, restarting the cycle at Step 2 [2].

This iterative loop continues until a performance target is met or a predetermined number of cycles are completed. In the MIT example, this process led to an optimal catalyst with a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar compared to pure palladium [2].

Workflow Visualization

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their promise, AI-driven labs face several challenges. Ensuring model generalizability beyond narrow chemical spaces and achieving standardized data formats across different laboratories and instruments remain significant hurdles [3]. The "explainability" of AI decisions is also an active area of research, as scientists need to trust and understand the AI's reasoning to gain fundamental scientific insights, not just optimized recipes [3]. Furthermore, building this infrastructure requires substantial initial investment and interdisciplinary expertise [7].

Future development will focus on creating more modular and flexible AI systems that can be easily adapted to different scientific domains [3]. Improved human-AI collaboration interfaces, potentially using natural language, will make these tools more accessible to a broader range of scientists [2]. There is also a push for the development of open-access datasets that include "negative" experimental results, which are crucial for training robust AI models and avoiding previously explored dead ends [3]. As these technologies mature, they will transition from specialized facilities to becoming integral components of the global materials research infrastructure.

The AI-driven lab represents a fundamental shift in the scientific methodology for materials discovery. By integrating robotics for tireless and precise experimentation with AI for intelligent planning and analysis, these systems create a powerful, accelerating feedback loop. They demonstrably compress discovery timelines from years to days, reduce resource consumption, and enhance reproducibility. While challenges remain, the continued convergence of AI, robotics, and materials science is creating an unprecedented capacity to solve complex material design problems, paving the way for rapid innovation in clean energy, electronics, and sustainable technologies.

The field of materials research is undergoing a profound transformation driven by artificial intelligence. Where traditional discovery relied on iterative experimentation and serendipity, AI-driven labs now leverage machine learning, foundation models, and natural language processing to accelerate the entire research lifecycle. These technologies are not merely supplemental tools but are becoming core components of the scientific method itself, enabling researchers to navigate complex design spaces, predict material properties, and optimize synthesis pathways with unprecedented speed and precision. The integration of these AI technologies addresses critical bottlenecks in materials research, where 94% of R&D teams reported abandoning at least one project in the past year due to time or computing resource constraints [10]. This whitepaper examines the key AI technologies powering this revolution and their practical implementation in accelerating materials discovery for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Core AI Technologies: Technical Foundations

Machine Learning in Materials Science

Machine learning (ML) represents a fundamental approach to artificial intelligence where computers learn patterns from data without explicit programming [11]. In materials science, ML captures complex correlations within experimental data to predict material properties and guide discovery. The technology excels in scenarios with substantial structured data—thousands or millions of data points from sensor logs, characterization results, or experimental measurements [11].

Best Applications in Materials Discovery:

- Predictive Modeling: ML algorithms can predict material properties based on composition or processing parameters, significantly reducing the need for physical testing.

- Pattern Recognition: Identifying subtle patterns in high-dimensional experimental data that may elude human observation.

- Optimization: Navigating complex parameter spaces to optimize synthesis conditions or material performance characteristics.

Traditional machine learning remains particularly valuable when dealing with highly specific domain knowledge or when privacy concerns limit the use of external AI services [11]. For well-established prediction tasks with substantial historical data, such as predicting phase diagrams or structure-property relationships, traditional ML often provides efficient and interpretable solutions.

Foundation Models and Their Capabilities

Foundation models represent a transformative advancement in AI—large-scale models trained on broad data that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [12]. In the context of materials science, these models demonstrate remarkable versatility, with applications spanning from literature mining to experimental design.

Key Technical Characteristics:

- Scale and Adaptability: Foundation models contain billions of parameters trained on diverse datasets, enabling them to handle various materials science tasks without task-specific retraining.

- Multimodal Capabilities: Modern foundation models can process and generate not only text but also images, structural data, and spectroscopic information.

- Rapid Evolution: The field is advancing at an extraordinary pace, with model capabilities increasing 10x year-over-year while costs decline dramatically [12].

In the enterprise landscape, foundation model usage has consolidated around high-performing models, with Anthropic capturing 32% of enterprise usage, followed by OpenAI at 25% and Google at 20% as of mid-2025 [13]. This consolidation reflects the critical importance of model performance in production environments.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) Technologies

Natural Language Processing enables machines to understand, interpret, and generate human language, serving as a crucial interface between researchers and complex AI systems [14]. By 2025, NLP has evolved from simple pattern matching to sophisticated contextual understanding, with transformer architectures like GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini demonstrating advanced reasoning capabilities [14] [15].

Critical NLP Capabilities for Scientific Research:

- Literature Mining: Extracting and synthesizing knowledge from millions of scientific papers far beyond human reading capacity.

- Experimental Protocol Understanding: Interpreting and executing natural language instructions for experimental procedures.

- Hypothesis Generation: Identifying promising research directions by detecting patterns across disparate scientific literature.

- Multilingual Processing: Enabling cross-cultural collaboration through real-time translation of scientific communications [14].

The integration of quantum computing with NLP (QNLP) represents an emerging frontier, exploring how quantum algorithms may transform language modeling for computationally complex scientific tasks [14].

Quantitative Analysis of AI Impact in Research

Table 1: Performance Metrics for AI Technologies in Materials Research

| Metric | Traditional Methods | AI-Accelerated Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Workloads Using AI | N/A | 46% of all simulation workloads [10] | N/A |

| Project Abandonment Due to Resource Limits | 94% of teams [10] | N/A | N/A |

| Cost Savings per Project | Baseline | ~$100,000 [10] | Significant |

| Accuracy Trade-off for Speed | N/A | 73% of researchers accept small accuracy trade-offs for 100× speed increase [10] | N/A |

| Time to Discovery | Months to years | Weeks to months [2] | 3-10× acceleration |

Table 2: Enterprise AI Adoption Metrics (Mid-2025)

| Adoption Metric | Value | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Organizations Using AI | 78% [16] | Up from 55% in 2023 |

| Foundation Model API Spending | $8.4 billion [13] | More than doubled from $3.5B |

| Production Inference Workloads | 74% of startups, 49% of enterprises [13] | Significant increase from previous year |

| Open-Source Model Usage | 13% of AI workloads [13] | Slight decrease from 19% |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CRESt Platform Workflow for Autonomous Materials Discovery

The Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists (CRESt) platform developed by MIT researchers represents the cutting edge of AI-driven materials discovery [2]. The system integrates multimodal AI with robotic equipment for end-to-end autonomous research.

Experimental Workflow:

Natural Language Interface: Researchers converse with CRESt in natural language to define research objectives and constraints, with no coding required [2].

Multimodal Knowledge Integration: The system incorporates diverse information sources including scientific literature, chemical databases, experimental data, and human feedback to create a comprehensive knowledge base [2].

Active Learning with Bayesian Optimization: CRESt employs Bayesian optimization in a reduced search space informed by literature knowledge embeddings to design optimal experiments [2].

Robotic Execution: Automated systems handle material synthesis (liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock systems), characterization (electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction), and performance testing (electrochemical workstations) [2].

Computer Vision Monitoring: Integrated cameras and vision language models monitor experiments in real-time, detecting issues and suggesting corrections to ensure reproducibility [2].

Iterative Refinement: New experimental results feed back into the AI models to refine predictions and guide subsequent experiment cycles [2].

In a landmark demonstration, CRESt explored over 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests over three months, discovering a catalyst material that delivered record power density in a direct formate fuel cell with a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium [2].

AI-Guided Materials Simulation Protocol

Methodology for AI-Accelerated Materials Simulation:

Data Collection and Curation: Aggregate existing experimental data, computational results, and literature knowledge into structured datasets suitable for training machine learning models.

Feature Engineering: Transform raw material descriptors (composition, structure, processing conditions) into meaningful features using domain knowledge and automated feature extraction.

Model Selection and Training: Choose appropriate ML algorithms (neural networks, Gaussian processes, random forests) based on data characteristics and prediction targets. Train models on available data with rigorous validation.

Active Learning Loop:

- Use current ML models to predict material properties and uncertainties across the design space.

- Select the most informative candidates for subsequent simulation or experimental validation.

- Incorporate new results to update and improve models iteratively.

Experimental Validation: Synthesize and characterize top candidate materials identified through AI guidance to confirm predicted properties.

This protocol has enabled nearly half (46%) of all materials simulation workloads to run on AI or machine-learning methods, representing a mainstream adoption of these technologies in materials R&D [10].

Visualization of AI-Driven Research Workflows

CRESt System Architecture for Autonomous Materials Discovery

Multimodal Learning in AI-Driven Materials Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AI-Driven Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in AI-Driven Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Precursors | Catalyst base material for optimization | Fuel cell catalyst development [2] |

| Formate Salts | Fuel source for performance testing | Direct formate fuel cell research [2] |

| Multi-element Catalyst Libraries | Diverse search space for AI exploration | High-throughput catalyst screening [2] |

| Neural Network Potentials | AI-accelerated atomic-scale simulations | Molecular dynamics and property prediction [10] |

| Automated Electron Microscopy Grids | High-throughput structural characterization | Microstructural analysis for AI training [2] |

| Electrochemical Testing Cells | Automated performance validation | Catalyst activity and stability testing [2] |

Future Outlook and Emerging Trends

The trajectory of AI in materials discovery points toward increasingly autonomous and integrated systems. Several key trends are shaping the future landscape:

Rise of Agentic AI: A new class of AI systems described as "virtual coworkers" can autonomously plan and execute multistep research workflows [17]. These agentic systems combine the flexibility of foundation models with the ability to act in the world, potentially revolutionizing how research is conducted.

Specialized Foundation Models: The market is evolving toward domain-specialized models trained specifically for scientific applications [14] [15]. These models demonstrate superior performance in technical domains compared to general-purpose alternatives.

Quantum-Enhanced AI: Though still experimental, quantum computing approaches to NLP (QNLP) and optimization problems may overcome current computational bottlenecks in materials simulation [14].

Democratization Through Efficiency: As AI becomes more efficient and affordable—with inference costs for GPT-3.5 level performance dropping 280-fold between 2022 and 2024—these technologies are becoming accessible to smaller research organizations [16].

The convergence of these technologies points toward a future where AI-driven labs become the standard rather than the exception, fundamentally accelerating the pace of materials discovery and development across scientific disciplines.

The process of scientific discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Artificial intelligence has evolved from a computational tool to an active participant in the research process, capable of learning from vast repositories of existing scientific knowledge and experimental data to accelerate discovery. In fields ranging from materials science to drug development, AI systems are now capable of integrating diverse information sources—from published literature and experimental results to chemical compositions and microstructural images—to form hypotheses, design experiments, and even guide robotic systems in conducting research. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms by which AI systems learn from existing scientific information, with particular focus on their application in AI-driven laboratories for materials discovery research.

The integration of AI into the scientific method represents a paradigm shift from traditional, often siloed approaches to a more integrated, data-driven methodology. Where human researchers traditionally rely on literature review, intuition, and iterative experimentation, AI systems can process and identify patterns across multidimensional data sources simultaneously. This capability is particularly valuable in materials science, where the parameter space for potential new materials is virtually infinite, and the relationships between composition, structure, processing, and properties are complex and often non-linear.

Core Learning Mechanisms: How AI Processes Scientific Information

Multimodal Data Integration and Processing

AI systems in scientific discovery leverage multiple data types and learning approaches to build comprehensive models of material behavior. The most advanced systems employ a multimodal learning framework that processes diverse information sources similarly to how human scientists integrate knowledge from different domains:

- Scientific Literature Analysis: Natural language processing (NLP) models extract relationships, material properties, and experimental protocols from millions of published scientific articles, creating a structured knowledge base of established scientific facts [2].

- Experimental Data Processing: Computer vision algorithms analyze microstructural images from electron microscopes, while machine learning models process spectral data, X-ray diffraction patterns, and electrochemical measurements [2] [9].

- Chemical and Structural Information: Compositional data and structural descriptors are encoded into numerical representations that capture essential chemical knowledge and spatial relationships [5].

The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform developed at MIT exemplifies this integrated approach. The system "uses multimodal feedback—for example information from previous literature on how palladium behaved in fuel cells at this temperature, and human feedback—to complement experimental data and design new experiments" [2]. This combination of historical knowledge and real-time experimental feedback creates a powerful discovery engine that can navigate complex material design spaces more efficiently than traditional approaches.

Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization

At the heart of many AI-driven discovery platforms is active learning powered by Bayesian optimization (BO). This approach allows systems to strategically select the most informative experiments to perform next, dramatically reducing the number of experiments required to converge on optimal solutions:

- Traditional Bayesian Optimization: "Basic Bayesian optimization is like Netflix recommending the next movie to watch based on your viewing history, except instead it recommends the next experiment to do," explains Ju Li from MIT [2]. However, standard BO often operates in a constrained design space and can get lost in high-dimensional parameter spaces.

- Enhanced Bayesian Optimization: Advanced systems like CRESt augment BO with literature knowledge and human feedback. As described by the MIT team: "For each recipe we use previous literature text or databases, and it creates these huge representations of every recipe based on the previous knowledge base before even doing the experiment. We perform principal component analysis in this knowledge embedding space to get a reduced search space that captures most of the performance variability" [2].

This enhanced approach to experimental design represents a significant advancement over traditional methods, as it incorporates both data-driven optimization and knowledge-based reasoning to guide the discovery process.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Workflow Architecture for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

The process of AI-driven discovery follows a structured workflow that integrates computational prediction with experimental validation. The diagram below illustrates this continuous cycle of learning and experimentation:

The CRESt Protocol: A Case Study in Fuel Cell Catalyst Discovery

A concrete example of this workflow in action comes from MIT's CRESt platform, which was used to discover advanced fuel cell catalysts [2]. The experimental protocol unfolded as follows:

Initial Knowledge Integration: The system began by ingesting and processing existing scientific literature on fuel cell catalysts, particularly focusing on palladium-based systems and their behavior at relevant operating temperatures.

Dataset Curation and Feature Engineering: Researchers curated a set of 879 square-net compounds described using 12 experimental features, training a Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel [5]. This approach translated expert intuition into quantitative descriptors extracted from measurement-based data.

Active Learning Cycle: The system engaged in an iterative process of:

- Proposing new material compositions based on both literature knowledge and experimental results

- Automatically synthesizing candidates using robotic systems

- Characterizing materials through automated electron microscopy and optical microscopy

- Testing electrochemical performance through automated workstations

Human-AI Collaboration: Researchers conversed with the system in natural language, providing feedback and guidance while the system explained its observations and hypotheses [2].

Experimental Monitoring and Quality Control: Cameras and visual language models monitored experiments, detecting issues and suggesting corrections to ensure reproducibility—a significant challenge in materials science research.

Through this protocol, CRESt explored more than 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests over three months, leading to the discovery of a catalyst material that delivered record power density in a fuel cell with just one-fourth the precious metals of previous devices [2].

The ME-AI Protocol: Encoding Expert Intuition into Machine Learning

The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework demonstrates an alternative approach that specifically focuses on capturing and quantifying expert intuition [5]:

Expert-Curated Dataset Assembly: Materials experts curate a refined dataset with experimentally accessible primary features chosen based on intuition from literature, ab initio calculations, or chemical logic.

Primary Feature Selection: Experts select atomistic and structural features that can be interpreted from a chemical perspective, including:

- Electron affinity and electronegativity

- Valence electron count

- Estimated lattice parameters of key elements

- Crystallographic characteristic distances

Expert Labeling: The human expert labels materials based on available experimental data, computational band structures, and chemical logic for related compounds.

Descriptor Discovery: Gaussian process models with specialized kernels identify emergent descriptors that correlate with target properties, effectively "bottling" the insights latent in the expert's intuition.

Remarkably, ME-AI trained on square-net compounds to predict topological semimetals successfully generalized to identify topological insulators among rocksalt structures, demonstrating transferability across material systems [5].

Quantitative Performance and Research Outputs

AI-driven discovery platforms have demonstrated significant improvements in research efficiency and outcomes across multiple domains. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from representative systems:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Discovery Platforms

| Platform/System | Application Domain | Research Scale | Key Outcomes | Time Compression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIT CRESt [2] | Fuel Cell Catalysts | 900+ chemistries, 3,500 tests | Record power density, 75% reduction in precious metals | 3 months for full discovery cycle |

| ME-AI [5] | Topological Materials | 879 square-net compounds | Identified new descriptors, transferable predictions | Not specified |

| Berkeley Lab A-Lab [9] | General Materials Discovery | Fully autonomous operation | Demonstrated continuous synthesis and characterization | Dramatically reduced characterization time |

| AI Drug Discovery [18] | Pharmaceutical Development | Multiple clinical candidates | Higher success rates, reduced costs | 18 months vs. 5+ years for traditional approaches |

Table 2: AI-Driven Experimental Capabilities and Infrastructure

| Capability Category | Specific Technologies | Function in Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Synthesis | Liquid-handling robots, Carbothermal shock systems, Remote-controlled pumps and gas valves | High-throughput preparation of material samples with tunable processing parameters [2] |

| Characterization & Analysis | Automated electron microscopy, Optical microscopy, X-ray diffraction, Automated electrochemical workstations | Structural and functional analysis of synthesized materials with minimal human intervention [2] [9] |

| Data Processing | Computer vision for image analysis, Spectral interpretation algorithms, Defect identification systems | Automated extraction of meaningful information from complex experimental data streams [2] [3] |

| Experiment Monitoring | Camera systems, Visual language models | Real-time quality control, problem detection, and suggestion of corrective actions [2] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Laboratories

The implementation of AI-driven discovery requires specialized infrastructure and reagents that enable automated, high-throughput experimentation. The table below details key research reagents and their functions in AI-accelerated materials discovery:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Infrastructure for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Reagent/Infrastructure | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-element Precursor Libraries | Provides diverse chemical building blocks for combinatorial synthesis | CRESt system incorporating up to 20 precursor molecules for materials discovery [2] |

| Automated Liquid Handling Systems | Enables precise, reproducible preparation of precursor solutions | Robotic systems in A-Lab and CRESt for sample preparation [2] [9] |

| High-Throughput Characterization Tools | Rapid structural and functional analysis of synthesized materials | Automated electron microscopy at MIT and Berkeley Lab [2] [9] |

| Electrochemical Testing Stations | Automated performance evaluation of energy materials | CRESt's 3,500 electrochemical tests for fuel cell catalysts [2] |

| Specialized Substrates and Templates | Controls material growth and morphology | Square-net compounds in ME-AI with specific structural motifs [5] |

| Data Management Platforms | Standardizes and structures experimental data for AI processing | FAIR data principles implementation in materials informatics [19] |

Integration Architectures: Human-AI Collaboration in Discovery

The most successful AI-driven discovery platforms emphasize collaboration between human researchers and AI systems rather than full automation. This relationship leverages the complementary strengths of human intuition and machine processing power:

This collaborative model, often described as the "Centaur Chemist" approach in AI-driven drug discovery, creates a powerful synergy where human scientists provide chemical intuition, biological context, and therapeutic vision while AI systems offer vast exploration of chemical space and pattern recognition across millions of data points [18]. As noted in studies of AI-driven laboratories, "Human researchers are still indispensable. In fact, we use natural language so the system can explain what it is doing and present observations and hypotheses. But this is a step toward more flexible, self-driving labs" [2].

The integration of natural language interfaces allows researchers to converse with AI systems without coding requirements, making these advanced capabilities accessible to domain experts who may not have computational backgrounds. This democratization of AI tools is critical for widespread adoption across scientific disciplines.

AI systems that learn from existing scientific literature and experimental data represent a transformative advance in the methodology of scientific research. By integrating multimodal information sources, employing sophisticated active learning strategies, and collaborating seamlessly with human researchers, these systems are accelerating the pace of discovery across multiple domains. The protocols and architectures described in this guide demonstrate how AI-driven laboratories are moving from theoretical concepts to practical tools that deliver tangible research outcomes.

As these systems continue to evolve, several trends are likely to shape their development: the increasing integration of physical knowledge into data-driven models to improve generalizability and interpretability; the development of more sophisticated transfer learning approaches that enable knowledge gained in one domain to accelerate discovery in others; and the creation of more seamless interfaces between human and machine intelligence. What is clear is that AI-driven discovery is not a future possibility but a present reality, already delivering measurable advances in materials science and drug development while reshaping the very process of scientific inquiry.

The Emergence of Materials Informatics as a Distinct, High-Growth Field

Materials informatics is a field of study that applies the principles of informatics and data science to materials science and engineering to improve the understanding, use, selection, development, and discovery of materials [20]. This emerging field aims to achieve high-speed and robust acquisition, management, analysis, and dissemination of diverse materials data with the goal of greatly reducing the time and risk required to develop, produce, and deploy new materials, which traditionally takes longer than 20 years [20]. The term "materials informatics" is frequently used interchangeably with "data science," "machine learning," and "artificial intelligence" by the community, though it encompasses a specific focus on materials-related challenges and applications [20].

The fundamental shift represented by materials informatics aligns with what Professor Kristin Persson from the University of California, Berkeley, identifies as the "fourth paradigm" in science [21]. Where the first paradigm was empirical science based on experiments, the second was model-based science developing equations to explain observations, and the third created simulations based on those equations, the fourth paradigm is science driven by big data and AI [21]. This evolution enables researchers to train machine-learning algorithms on extensive materials data, bringing "a whole new level of speed in terms of innovation" [21].

The Core Drivers of Growth

Market Expansion and Economic Potential

The materials informatics market is experiencing remarkable growth, demonstrating its emergence as a distinct, high-growth field. According to market analysis, the global materials informatics market is projected to grow from USD 208.41 million in 2025 to approximately USD 1,139.45 million by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.80% over the forecast period [22].

Table 1: Global Materials Informatics Market Forecast (2025-2034)

| Year | Market Size (USD Million) | Year-over-Year Growth |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 173.02 | - |

| 2025 | 208.41 | 20.44% |

| 2034 | 1,139.45 | 20.80% CAGR |

Geographically, North America dominated the market in 2024 with a 39.20% share, valued at USD 67.82 million, and is expected to reach USD 423.88 million by 2034 [22]. However, the Asia-Pacific region is projected to be the fastest-growing market, with Japan expected to achieve a remarkable CAGR of 23.9% from 2024 to 2034 [22].

This growth is fueled by multiple factors, including the integration of AI, machine learning, and big data analytics to accelerate material discovery, design, and optimization across industries [22]. Additionally, rising demand for eco-friendly materials aligned with circular economy principles and increasing government funding for advanced material science are strengthening the market outlook [22].

Technological and Data Infrastructure Drivers

Three key drivers are catalyzing the rapid adoption of materials informatics. First, substantial improvements in AI-driven solutions leveraged from other sectors, including the impact of large language models in simplifying materials informatics workflows [23]. Second, significant improvements in data infrastructures, from open-access data repositories to cloud-based research platforms [23]. Third, growing awareness, education, and a need to keep up with the underlying pace of innovation, accelerated by the recent AI boom [23].

Governments worldwide are actively investing in materials informatics infrastructure and research. During the Obama administration, the United States launched the Materials Genome Initiative, directly supporting material informatics tools and open databases [22]. Similar initiatives include China's "Made in China 2025," Europe's "Horizon Europe" program, and India's "National Mission on Interdisciplinary Cyber-Physical Systems" (NM-ICPS) [22].

AI-Driven Methodologies and Workflows

The Materials Informatics Workflow

AI-driven materials discovery follows a structured workflow that combines computational and experimental approaches. The core process involves several interconnected phases that form a continuous innovation cycle.

This workflow enables what IDTechEx identifies as three key advantages of employing machine learning in materials R&D: enhanced screening of candidates and scoping research areas, reducing the number of experiments needed to develop new materials (and therefore time to market), and discovering new materials or relationships that might not be found through traditional methods [23].

Key Algorithmic Approaches

Materials informatics employs diverse algorithmic approaches tailored to handle the unique challenges of materials science data, which is often sparse, high-dimensional, biased, and noisy [23].

Table 2: Core Algorithmic Approaches in Materials Informatics

| Algorithm Category | Key Functionality | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | Classical data-driven modeling and pattern recognition | Baseline analysis, data preprocessing, initial screening |

| Digital Annealer | Optimization and solving complex combinatorial problems | Material formulation optimization, process parameter tuning |

| Deep Tensor | Handling complex, multi-dimensional relationships | Predicting quantum mechanical properties, molecular dynamics |

| Genetic Algorithms | Evolutionary optimization through selection and mutation | Materials design space exploration, multi-objective optimization |

The choice of algorithm depends heavily on the specific materials challenge. As noted in a comprehensive review, "Traditional computational models offer interpretability and physical consistency, AI/ML excels in speed and complexity handling but may lack transparency. Hybrid models combining both approaches show excellent results in prediction, simulation, and optimisation, offering both speed and interpretability" [19].

Case Studies in AI-Accelerated Discovery

Self-Driving Laboratories: The Polybot System

Researchers at Argonne National Laboratory have developed Polybot, an AI-driven automated materials laboratory that exemplifies the transformative potential of autonomous discovery [24]. This system addresses the significant challenge of optimizing electronic polymer thin films, where "nearly a million possible combinations in the fabrication process can affect the final properties of the films — far too many possibilities for humans to test" [24].

The experimental protocol implemented in Polybot demonstrates a fully automated, closed-loop discovery process:

According to Henry Chan, a computational materials scientist at Argonne, "Using AI-guided exploration and statistical methods, Polybot efficiently gathered reliable data, helping us find thin film processing conditions that met several material goals" [24]. The system successfully optimized two key properties simultaneously: conductivity and coating defects, producing thin films with average conductivity comparable to the highest standards currently achievable [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Electronic Polymer Discovery

| Reagent/Category | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Polymers | Base material exhibiting both plastic and conductive properties | Wearable devices, printable electronics, advanced energy storage |

| Coating Formulations | Carrier solvents and additives that affect film formation | Optimizing conductivity and reducing defects in thin films |

| Characterization Tools | Wide-angle X-ray scattering for structural analysis | Determining crystallinity and molecular orientation in films |

| Image Analysis Software | Automated quality assessment of film morphology | Quantifying defects and uniformity without human bias |

Generative Materials Design: MatterGen and MatterSim

Microsoft Research's AI for Science initiative has developed MatterGen and MatterSim, representing a paradigm shift in materials design [25]. MatterGen serves as a "generative model for materials design" that "crafts detailed concepts of molecular structures by using advanced algorithms to predict potential materials with unique properties" [25]. This approach represents a radical departure from traditional screening methods by directly generating novel materials given prompts of design requirements for an application [25].

As Tian Xie, Principal Research Manager at Microsoft Research AI for Science, explains: "MatterGen generates thousands of candidates with user-defined constraints to propose new materials that meet specific needs. This represents a paradigm shift in how materials are designed" [25]. Once MatterGen proposes candidate materials, MatterSim applies "rigorous computational analysis to predict which of those imagined materials are stable and viable, like a sieve filtering out what's physically possible from what's merely theoretical" [25].

This tandem functionality exemplifies the powerful trend toward what IDTechEx describes as solving the "inverse" design problem: "materials are designed given desired properties" rather than simply discovering properties for existing materials [23].

Accelerated Battery Innovation

The global shift toward electric mobility and renewable energy has created unprecedented demand for improved energy storage systems [22]. Traditional trial-and-error methods for battery material development are costly and time-consuming, often taking years to validate new chemistries [22].

A case study involving a leading EV manufacturer demonstrates the transformative impact of materials informatics on battery development [22]. The company sought to develop next-generation batteries offering higher energy density, faster charging, and longer lifecycle while reducing reliance on critical raw materials such as cobalt [22]. By leveraging AI-driven predictive modeling, deep tensor learning, and digital annealing, the company built a computational framework that:

- Screened thousands of potential electrode materials in days instead of years

- Predicted conductivity, stability, and degradation patterns with high accuracy

- Identified cobalt-free alternatives with similar or superior performance

- Integrated sustainability by forecasting lifecycle impacts and recyclability

The results were significant: discovery cycles reduced from 4 years to under 18 months, R&D costs lowered by 30% through reduced trial-and-error experimentation, and development of a high-performing lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) battery variant with improved energy density [22].

Essential Infrastructure and Tools

Data Repositories and Platforms

The effectiveness of materials informatics depends heavily on access to high-quality, standardized data. Several key initiatives and platforms have emerged to address this need:

- The Materials Project: A multi-institution, multinational effort that calculates properties of known inorganic materials and beyond (currently 160,000 materials) using supercomputing and state-of-the-art simulation methods, with data made freely available [21].

- MaterialsWeb.org: A University of Florida database containing theoretical data obtained computationally [20].

- High-Throughput Software Tools: Pymatgen, MPInterfaces, and Matminer enable efficient screening and analysis of materials data [20].

These resources are essential because, as Professor Persson notes, "In materials science, we have a data shortage. Out of all the near endless possible materials, only a very tiny fraction have been made, and of them, few have been well characterized" [21]. Computational approaches help bridge this gap since "we can now calculate material properties much faster than we can synthesize materials and measure their properties" [21].

Commercial Platforms and Integration

Commercial materials informatics platforms have evolved from simple databases to AI-enabled, integrated tool suites [26]. These systems typically include six key aspects: comprehensive datasets, thoughtful data structure, intuitive user interfaces, cross-platform integration, analytical and predictive tools, and robust traceability [26].

Ansys describes the progression from early manual methods to contemporary approaches: "Before computers, material property information was captured in data sheets or handbooks, and engineers would look up properties manually. When computers were introduced, these lists were digitized into searchable databases, but the process remained manual" [26]. Modern systems now leverage "computational algorithms, data analytics, graphical material selection tools, natural language search, intuitive user interfaces, machine learning (ML), redundant and secure data storage, [and] methods for systematic material comparison" [26].

The most significant trend for material informatics is "the continued usage of machine learning and deep learning (DL) frameworks," along with better integration both within materials information platforms and between these platforms and other applications like supply chain tools, CAD software, and simulation [26].

Future Directions and Challenges

Emerging Frontiers

The future of materials informatics points toward increasingly autonomous and integrated systems. As Daniel Zügner, a senior researcher with Microsoft's AI for Science team, notes: "Our focus is on driving science in a meaningful way. The team isn't preoccupied with publishing papers for the sake of it. We're deeply committed to research that can have a positive, real-world impact, and this is just the beginning" [25].

Key emerging frontiers include:

- Autonomous Self-Driving Laboratories: The "dream end-goal" for many researchers is for humans to oversee autonomous self-driving laboratories, with early-stage implementations already showing promise [23].

- Foundation Models for Materials Science: Following the impact of large language models, the development of specialized foundation models for materials science represents a significant opportunity [23].

- Quantum Computing Integration: The combination of AI and quantum computing will open up new possibilities for materials simulation and discovery, with five material platforms mainly being pursued for quantum computer development: superconductors, semiconductors, trapped ions, photons, and neutral atoms [21].

- Neuromorphic Computing: As data centers currently account for about 2% of global electricity consumption with predictions of significant increase, neuromorphic computing that mimics the brain's efficiency offers promising energy savings. As Huaqiang Wu of Tsinghua University notes: "Improvements in energy efficiency are plateauing for silicon chips, but they are still 10,000 less efficient than the human brain. We need to ask how we can mimic the brain to build AI chips" [21].

Persistent Challenges

Despite rapid progress, materials informatics faces several significant challenges. The high cost of implementation presents a barrier, particularly for small and mid-sized businesses [22]. Success requires "data collection and integration because the organization has to collect and integrate information from various sources, including research literature, simulations, and experimental results" [22].

Cultural and methodological barriers also remain. As Hill et al. note: "Today, the materials community faces serious challenges to bringing about this data-accelerated research paradigm, including diversity of research areas within materials, lack of data standards, and missing incentives for sharing, among others" [20]. This tension between traditional materials development methodologies and computationally-driven approaches "will likely exist for some time as the materials industry overcomes some of the cultural barriers necessary to fully embrace such new ways of thinking" [20].

Furthermore, as IDTechEx observes, contrary to what some may believe, materials informatics "is not something that will displace research scientists. If integrated correctly, MI will become a set of enabling technologies accelerating scientists' R&D processes whilst making use of their domain expertise" [23].

Progress in overcoming these challenges depends on developing "modular, interoperable AI systems, standardised FAIR data, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Addressing data quality and integration challenges will resolve issues related to metadata gaps, semantic ontologies, and data infrastructures, especially for small datasets and unlock transformative advances in fields like nanocomposites, MOFs, and adaptive materials" [19].

Inside the Self-Driving Lab: AI Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Self-driving laboratories (SDLs) represent a paradigm shift in materials research, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and high-throughput experimentation into a closed-loop system to accelerate discovery. These autonomous platforms leverage machine learning to make intelligent decisions, guiding the iterative cycle of computational design, robotic synthesis, and automated characterization. By transitioning from traditional trial-and-error methods to a data-intensive, AI-driven approach, SDLs demonstrably reduce discovery timelines from years to days while significantly cutting costs and chemical waste [8] [3]. This whitepaper details the core technical workflow of SDLs, provides quantitative performance data, and outlines specific experimental protocols, framing this discussion within the broader thesis of how AI-driven labs are revolutionizing the pace and efficiency of materials discovery for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Core Closed-Loop Workflow

The operational backbone of a self-driving lab is its closed-loop workflow, which seamlessly integrates computational and physical components. The loop begins with a researcher-defined objective, such as discovering a material with a specific property or performance metric. An AI planner, often using active learning and Bayesian optimization, then proposes an initial set of experiments or a candidate material based on available data and prior knowledge [2] [3]. This digital design is passed to a robotic synthesis system, which automatically executes the experimental procedure, whether it involves chemical synthesis, material deposition, or sample preparation. The resulting material is then channeled to automated characterization tools, which collect performance and property data. This newly generated data is fed back to the AI model, which updates its understanding of the vast parameter space and proposes the next most informative experiment. This creates a continuous, autonomous cycle of learning and experimentation [24] [27].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental, iterative process.

How AI-Driven Labs Accelerate Discovery

The acceleration offered by SDLs stems from several key AI-driven capabilities that distinguish them from traditional research and development.

Data Intensification: Traditional automated experiments often rely on steady-state measurements, collecting a single data point per experimental run. Advanced SDLs now employ strategies like dynamic flow experiments, where chemical mixtures are continuously varied and monitored in real-time. This approach captures data every half-second, generating at least an order-of-magnitude more data than conventional methods and providing a "movie" of the reaction process instead of a "snapshot" [8]. This rich data stream enables the machine learning algorithm to make smarter, faster decisions.

Smarter, Multi-Faceted Decision-Making: While basic Bayesian optimization is effective in constrained spaces, it can be limited. Next-generation platforms, such as MIT's CRESt, incorporate multimodal feedback. This means the AI considers diverse information sources, including experimental results, scientific literature, microstructural images, and even human feedback, to guide its experimental planning. This creates a more collaborative and knowledge-rich discovery process, mimicking human intuition but at a vastly superior scale and speed [2].

Efficient Resource Utilization: By making more informed decisions about which experiment to run next, SDLs drastically reduce the number of experiments required to identify an optimal material. This directly translates to reductions in chemical consumption, waste generation, and researcher hours. A survey of materials R&D professionals found that computational simulation saves organizations roughly $100,000 per project on average compared to purely physical experiments [10].

Quantitative Performance of SDL Systems

The impact of SDLs is quantifiable across multiple performance metrics. The table below summarizes key findings from recent implementations.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Self-Driving Labs

| SDL System / Project | Acceleration / Efficiency Gain | Resource Reduction | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Flow SDL (NC State) [8] | At least 10x improvement in data acquisition efficiency; identifies optimal candidates on the first try post-training. | Reduces both time and chemical consumption compared to state-of-the-art fluidic labs. | Applied to CdSe colloidal quantum dots. |

| CRESt Platform (MIT) [2] | Explored 900+ chemistries, conducted 3,500+ tests in 3 months. | Achieved a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar for a fuel cell catalyst. | Discovered an 8-element catalyst with record power density. |

| Industry-Wide Impact (Matlantis Report) [10] | 46% of simulation workloads now use AI/ML; 94% of teams abandon projects due to time/compute limits. | Average savings of ~$100,000/project via computational simulation. | 73% of researchers would trade minor accuracy for a 100x speed increase. |

| Polybot (Argonne Nat. Lab) [24] | Autonomous exploration of nearly a million processing combinations for electronic polymers. | Simultaneously optimized conductivity and defects. | Produced high-conductivity, low-defect polymer films. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols in SDLs

To illustrate the practical implementation of the SDL workflow, here are detailed methodologies from two prominent cases.

Protocol A: Dynamic Flow Synthesis of Colloidal Quantum Dots

This protocol, as implemented by Abolhasani et al., focuses on the accelerated discovery and optimization of inorganic nanomaterials like CdSe quantum dots [8].

AI-Driven Planning: The machine learning algorithm is initialized with a defined chemical search space (e.g., precursor types, concentrations, ratios). It uses an active learning strategy to select the first experiment(s) or a set of initial conditions for a dynamic flow.

Continuous Flow Synthesis: Precursors are loaded into automated syringe pumps.

- The system transitions from steady-state to dynamic flow experiments. Instead of maintaining fixed flow rates for a set time, the pumps continuously and dynamically vary the flow rates of the chemical precursors as they are introduced into a continuous-flow microreactor.

- The reaction mixture flows through a temperature-controlled microchannel, where nucleation and growth occur.

Real-Time, In-Line Characterization: The reacting fluid stream passes through a flow cell connected to real-time, in-situ spectroscopic probes (e.g., UV-Vis absorbance, photoluminescence).

- Data is captured at high frequency (e.g., every 0.5 seconds), recording the optical properties of the quantum dots at different reaction times and chemical conditions simultaneously [8].

Data Streaming & Analysis: The high-throughput spectral data is automatically processed by a data pipeline. Key properties (e.g., absorption peak wavelength, emission intensity, quantum yield estimate) are extracted in real-time.

Closed-Loop Feedback: The stream of processed property data is fed to the machine learning model. The model uses this intensified data to update its internal surrogate model of the synthesis-property relationship and immediately proposes the next set of dynamic flow parameters to better approach the target material properties, closing the loop.

Protocol B: Autonomous Discovery of Multielement Fuel Cell Catalysts

This protocol, based on the CRESt platform from MIT, demonstrates the optimization of a complex functional material [2].

Multimodal Knowledge Integration: The AI is provided with the research goal (e.g., "maximize power density for a direct formate fuel cell catalyst using minimal precious metals"). The system begins by searching through scientific literature and databases to create knowledge embeddings for potential elements and precursor recipes.

Robotic Synthesis & Sample Preparation:

- A liquid-handling robot prepares catalyst libraries by dispensing solutions containing up to 20 different precursor elements according to the AI's proposed recipe [2].

- Synthesis is completed using a carbothermal shock system or other rapid synthesis techniques to create the nanomaterial catalysts.

Automated Characterization & Performance Testing:

- The synthesized catalysts are transferred to an automated electrochemical workstation.

- A series of standardized tests (e.g., cyclic voltammetry, chronoamperometry) are performed to evaluate catalytic activity, stability, and resistance to poisoning species.

- Automated electron microscopy (e.g., SEM) is used to characterize the microstructure and morphology.

Computer Vision-Assisted Quality Control: Cameras monitor the robotic processes. Vision language models analyze the images to detect issues such as misaligned samples or pipetting errors, suggesting corrections to ensure reproducibility.

Human-AI Collaborative Optimization: Experimental data and characterization images are fed back into the large multimodal model. The AI incorporates this data with prior literature knowledge and can receive feedback from a human researcher via natural language. The AI then refines its search space and uses Bayesian optimization to design the next batch of experiments.

Workflow Visualization: The Dynamic Flow Advantage

A key innovation in modern SDLs is the shift from discrete experiments to continuous processes. The following diagram contrasts the traditional steady-state approach with the advanced dynamic flow method, highlighting the source of accelerated data acquisition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The functionality of an SDL depends on a suite of integrated hardware and software components. The table below details key solutions and their functions within a typical materials discovery SDL.

Table 2: Essential Components of a Self-Driving Lab for Materials Discovery

| Tool / Solution Category | Specific Examples / Functions | Role in the SDL Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AI & Decision-Making Core | Bayesian Optimization (BO), Active Learning, Large Multimodal Models (e.g., in CRESt) [2]. | The "brain" that plans experiments by predicting the most informative conditions to test next. |

| Robotic Synthesis Systems | Liquid-Handling Robots, Continuous Flow Reactors [8], Carbothermal Shock Synthesizers [2], VSParticle Nano-Printers [27]. | The "hands" that automatically and precisely execute material synthesis and sample preparation. |

| Automated Characterization Tools | In-line UV-Vis/PL Spectrometry [8], Automated Electrochemical Workstations [2], Automated Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) [24]. | The "eyes" that analyze synthesized materials to collect performance and property data. |