HDR vs. NHEJ: A Strategic Guide to DNA Repair Pathways for CRISPR Genome Editing and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two primary DNA double-strand break repair pathways, Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), with a focus on their application in...

HDR vs. NHEJ: A Strategic Guide to DNA Repair Pathways for CRISPR Genome Editing and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two primary DNA double-strand break repair pathways, Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), with a focus on their application in CRISPR-based genome editing. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental mechanisms of each pathway, their strategic use in creating knockouts and precise knockins, and advanced methodologies for enhancing HDR efficiency. The scope extends to troubleshooting common challenges, comparing the outcomes and fidelity of each pathway, and discussing their implications for biomedical research and next-generation therapeutic development.

The Cellular Machinery: Unraveling the Fundamental Mechanisms of NHEJ and HDR

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) represent one of the most lethal forms of DNA damage, with significant implications for cellular function and organismal health [1]. Failure to properly repair these lesions can lead to genomic instability, which underlies many human diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and various genetic syndromes [1] [2]. To combat this threat, cells have evolved a sophisticated network of repair pathways that sense, signal, and repair DSBs. Understanding these mechanisms is fundamental to biomedical research, particularly in the development of novel therapeutic strategies and the advancement of genome editing technologies.

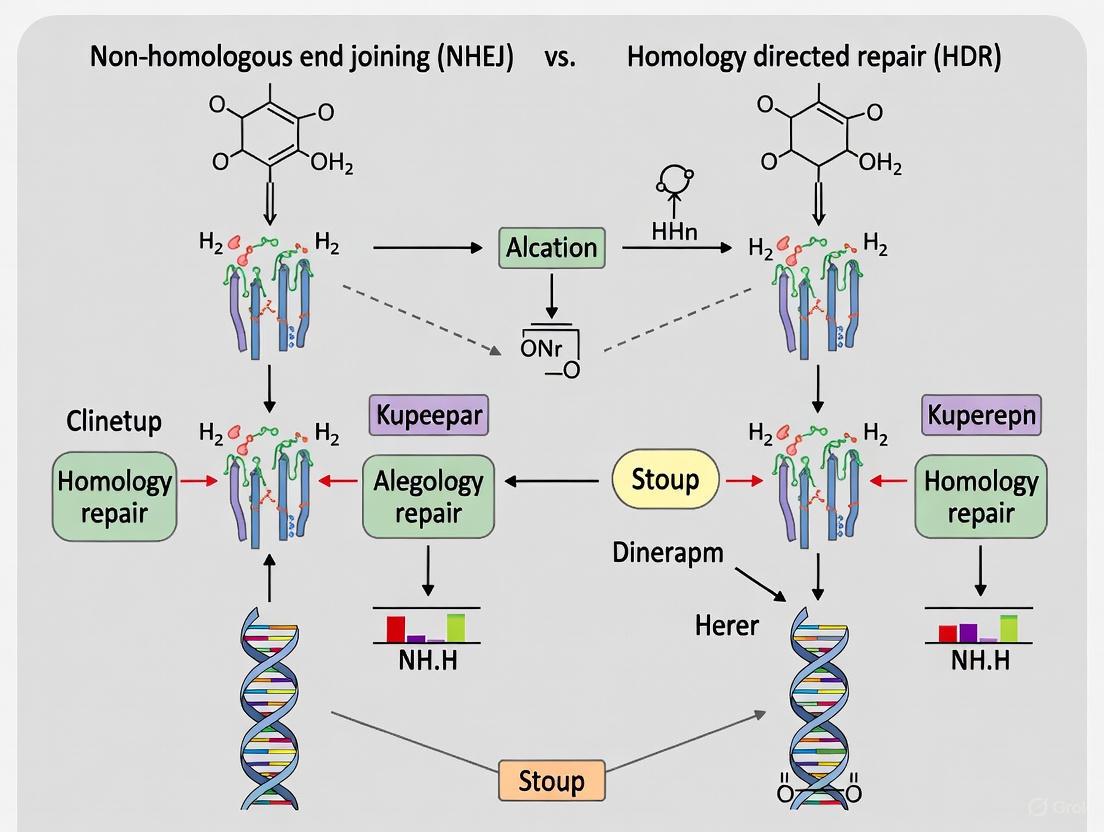

The revolutionary CRISPR-Cas9 system, which has transformed genetic research, operates precisely by exploiting these endogenous DNA repair pathways [3] [4]. While many believe the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery performs genetic modifications directly, it actually serves only as "molecular scissors" that create targeted DSBs; the actual genetic editing occurs through the cell's native repair mechanisms [4]. This understanding has catalyzed intense research into manipulating these pathways for more precise genome engineering, particularly in the context of balancing non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) against homology-directed repair (HDR) outcomes.

DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

Eukaryotic cells employ several distinct pathways to repair DSBs, which can be broadly categorized into two groups: homology-independent and homology-dependent mechanisms [5]. The homology-independent pathways include classical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ) and alternative end-joining pathways (A-EJ) such as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), while homology-dependent pathways encompass homology-directed repair (HDR) and single-strand annealing (SSA) [6] [7] [8]. These pathways compete for DSB repair, with their utilization influenced by factors such as cell cycle stage, chromatin context, and the nature of the break itself.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Mechanism and Key Players: Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is often described as the cell's "first responder" to DSBs [7]. This pathway operates throughout the cell cycle but is particularly dominant during G1/early S phase [9]. In the canonical NHEJ pathway (c-NHEJ), the Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer rapidly recognizes and binds to broken DNA ends, effectively preventing extensive resection [7] [9]. This binding recruits DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), which helps align the damaged ends and orchestrates the recruitment of processing enzymes such as nucleases or polymerases [7]. The Artemis endonuclease may remove overhanging nucleotides, while Pol μ or Pol λ can fill in small gaps [7]. Finally, XRCC4 and DNA ligase IV (LIG4) perform the ligation step that rejoins the broken ends [7] [9].

Functional Outcomes: NHEJ is characterized by its speed and efficiency but often sacrifices precision. The rejoining of broken ends frequently results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site [3] [4]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9 editing, this error-prone nature makes NHEJ ideal for gene knockout strategies, where introducing frameshift mutations that disrupt gene function is the desired outcome [3] [4]. The asymmetry of Cas9 cutting, where one DNA strand is cleaved prior to the other, can create a temporal window that further favors indel formation [7].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Mechanism and Key Players: Homology-directed repair (HDR) provides a high-fidelity alternative to NHEJ by utilizing homologous DNA sequences as templates for accurate repair [3] [7]. This pathway is primarily restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when sister chromatids are available as natural templates [7] [5]. The HDR process initiates with the MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) recognizing the break and partially resecting the 5' ends with CtIP, generating short 3' single-stranded overhangs [7]. Long-range resection by Exo1 and the Dna2/BLM helicase complex then creates extended 3' ssDNA tails, which are protected by replication protein A (RPA) [7]. RAD51 subsequently displaces RPA and forms nucleoprotein filaments that perform a homology search. Upon locating a suitable homologous donor sequence, the RAD51-ssDNA filaments initiate strand invasion to form a displacement loop (D-loop) [7]. DNA polymerase then extends the invading strand using the homologous sequence as a template.

Functional Outcomes: HDR is essential for precise genetic modifications, including gene corrections, specific insertions, or the creation of point mutations [3] [4]. Researchers can leverage HDR by providing exogenous donor templates containing the desired sequence flanked by homology arms that match the regions surrounding the DSB [3]. This approach enables high-fidelity genome editing but suffers from lower efficiency compared to NHEJ, partly due to its cell cycle dependence and the complex orchestration of multiple steps including resection, strand invasion, and synthesis [7].

Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond the classical NHEJ and HDR pathways, cells utilize alternative mechanisms for DSB repair, particularly when primary pathways are compromised or in specific sequence contexts.

Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): MMEJ, also referred to as polymerase theta-mediated end-joining (TMEJ), relies on short microhomologies (2-20 nucleotides) flanking the DSB to guide repair [6] [7]. DNA polymerase theta (Pol θ), assisted by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), typically mediates this process [7]. Because MMEJ deletes sequences between these microhomologous regions, it often generates moderate-to-large deletions and is considered highly error-prone [7]. Recent research has revealed that MMEJ is particularly active during early rapid mitotic cell cycles [5].

Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): SSA requires more extensive stretches of homology (usually >20 nucleotides) flanking the DSB [6] [7]. After end resection exposes these homologous sequences, they anneal under the influence of RAD52 [6] [7]. As with MMEJ, the intervening DNA is excised, causing characteristically large deletions [7]. SSA has been shown to contribute to various imprecise repair patterns in CRISPR-mediated knock-in, even when NHEJ is inhibited [6].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Pathway | Template Requirement | Key Protein Factors | Fidelity | Cell Cycle Phase | Primary Mutational Signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-NHEJ | None | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4, LIG4 | Error-prone | All phases (G1/early S dominant) | Small insertions/deletions (indels) |

| HDR | Homologous template (sister chromatid or donor DNA) | MRN complex, CtIP, RPA, RAD51 | High-fidelity | S and G2 phases | Precise repair or targeted modification |

| MMEJ | Microhomology (2-20 nt) | POLQ (Pol θ), PARP1 | Error-prone | All phases | Deletions flanked by microhomology |

| SSA | Long homologous repeats (>20 nt) | RAD52, ERCC1 | Error-prone | S and G2 phases | Large deletions |

Quantitative Analysis of Repair Pathway Dynamics

Pathway Competition and Regulation

The choice between different DSB repair pathways is not random but governed by a complex regulatory network that integrates cellular context with break characteristics. A critical factor in this decision is DNA end resection—the nucleolytic processing of DNA ends to generate single-stranded overhangs [7]. While NHEJ predominates when resection is limited, extensive resection favors HDR and other homology-dependent pathways like SSA [7].

Proteins such as 53BP1 and the Shieldin complex stabilize DNA ends against resection, thereby promoting NHEJ, whereas BRCA1 and CtIP promote resection and facilitate HDR [7]. The cell cycle phase exerts perhaps the most significant influence on pathway choice: NHEJ operates throughout all phases but dominates in G1, while HDR is restricted to S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available as templates [7] [5].

Recent research using sophisticated classification systems has revealed that DSB repair outcomes exhibit remarkable reproducibility with defined alternative categories depending on different target sites, inheritance patterns of CRISPR components, and developmental stage [5]. Studies have identified a developmental progression wherein MMEJ or insertion events predominate during early rapid mitotic cell cycles, switching to distinct subsets of NHEJ alleles, and then to HDR-based gene conversion [5].

Quantitative Assessment of Repair Outcomes

Advanced sequencing technologies combined with novel bioinformatic pipelines have enabled precise quantification of DSB repair outcomes. Recent studies investigating CRISPR-mediated endogenous tagging in human cells revealed that even with NHEJ inhibition, perfect HDR events accounted for only a portion of repair outcomes, with imprecise integration still representing nearly half of all integration events [6]. This highlights the significant contribution of alternative pathways even when the dominant NHEJ pathway is suppressed.

Table 2: Quantitative Distribution of CRISPR-Mediated Knock-In Repair Outcomes with Pathway Inhibition

| Repair Condition | Perfect HDR (%) | Imprecise Integration (%) | Small Deletions <50 nt (%) | Large Deletions ≥50 nt (%) | Complex Indels (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.2-6.9 | ~50 | High | Moderate | Present |

| NHEJ Inhibition | 16.8-22.1 | ~50 | Significantly reduced | Moderate | Reduced |

| MMEJ Inhibition | Increased | Reduced | Similar to control | Significantly reduced | Significantly reduced |

| SSA Inhibition | No significant change | Reduced (especially asymmetric HDR) | Similar to control | Moderate | Reduced |

The development of integrated classifier pipelines (ICP) has enabled researchers to decompose and categorize Cas9-induced DSB repair outcomes with single-allelic resolution [5]. These tools output rank-ordered and sub-categorized mutational allele fingerprints that reveal highly reproducible and defining alternative categories of DNA-repair outcomes [5]. Such approaches allow simultaneous quantification of both NHEJ and HDR events within the same sample, providing a more comprehensive view of the editing landscape [5].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Detection and Quantification Methods

Genetic Reporter Assays: Reporter systems have been extensively developed to detect and quantify specific DSB repair outcomes. These assays typically use selectable or screenable markers that are functionally restored through specific repair events [10]. For example, fluorescence-based reporters can track HDR, NHEJ, MMEJ, and SSA outcomes by measuring the restoration of functional fluorescent proteins through distinct repair mechanisms [5]. These systems are particularly valuable for high-throughput screening of factors influencing repair pathway choice.

Molecular and Cytological Assays: Direct molecular analysis of repair outcomes can be achieved through various methods. Southern blotting provides information about genomic rearrangements, while pulsed-field gel electrophoresis detects large DNA molecules and chromosomal abnormalities [10]. Cytological approaches using immunofluorescence allow detection of DNA lesions, repair intermediates, and DNA repair proteins at the single-cell level, providing spatiotemporal information about the repair process [10]. For instance, γ-H2AX staining serves as a sensitive marker for DSBs and can be combined with flow cytometry for quantitative analysis [1].

Sequencing-Based Approaches: Next-generation sequencing combined with custom bioinformatic pipelines has revolutionized the analysis of DSB repair outcomes [5] [2]. Methods like Repair-seq enable high-throughput mapping of genetic dependencies by measuring the effects of thousands of genetic perturbations on mutations introduced at targeted DNA lesions [2]. Long-read amplicon sequencing using platforms such as PacBio provides comprehensive views of repair patterns, while integrated classification pipelines (ICP) parse complex editing outcomes with single-allele resolution [6] [5].

Quantitative DSB Detection Methods: The standard curve method using ligation-mediated quantitative PCR (LM-qPCR) offers a simple, cost-effective approach for quantifying genome-wide DSBs [1]. This method generates DSB standards through restriction enzyme digestion and constructs standard curves with high linearity (R² > 0.95), enabling accurate quantification of DSB numbers across various organisms [1].

Strategic Pathway Modulation

Enhancing HDR Efficiency: Given the therapeutic importance of precise genome editing, numerous strategies have been developed to enhance HDR efficiency. These include:

- Transient suppression of NHEJ factors (e.g., 53BP1, DNA-PKcs, or Ku70/Ku80) using small-molecule inhibitors, RNA interference, or CRISPR-based knockdown [7]

- Inhibition of alternative pathways such as MMEJ (using POLQ inhibitors like ART558) and SSA (using RAD52 inhibitors like D-I03) [6]

- Cell cycle synchronization to enrich for cells in S/G2 phases when HDR is most active [7] [4]

- Optimization of donor template design, including the use of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with appropriate homology arm length [4]

- Engineering of HDR-enhancing fusion proteins that recruit specific factors to DSB sites [7]

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Repair Analysis: The following diagram illustrates a integrated experimental approach for analyzing DNA repair pathways, synthesizing methodologies from recent studies:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | Potent NHEJ pathway suppression | Enhances HDR efficiency in genome editing [6] |

| MMEJ Inhibitors | ART558 | POLQ (Pol θ) inhibition | Suppresses microhomology-mediated repair [6] |

| SSA Inhibitors | D-I03 | RAD52 inhibition | Reduces single-strand annealing events [6] |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescence-based cassettes | Quantitative assessment of specific repair pathways | High-throughput screening of repair outcomes [5] |

| Computational Tools | Integrated Classifier Pipeline (ICP) | Classification of mutant alleles with single-allele resolution | Decomposition of complex DSB repair outcomes [5] |

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio long-read sequencing | Comprehensive analysis of repair patterns | Detection of imprecise integration events [6] |

Research Applications and Future Directions

The ability to understand and manipulate DSB repair pathways has profound implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. In genome editing, strategic pathway selection enables researchers to pursue distinct experimental goals: NHEJ for efficient gene disruption and HDR for precise genetic modifications [3] [4]. The discovery that alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA significantly contribute to editing outcomes, even when NHEJ is suppressed, highlights the complexity of the cellular repair network and the need for multi-pathway targeting strategies [6].

Emerging research indicates that DSB repair pathways operate in a developmentally regulated manner, with distinct pathways dominating at different developmental stages [5]. This temporal regulation of repair mechanisms has important implications for gene editing in various biological contexts, from early embryogenesis to differentiated tissues. Furthermore, the development of sophisticated classification systems like ICP enables marker-free tracking of specific mutations in dynamic populations and simultaneous quantification of both NHEJ and HDR events within the same sample [5].

Future research directions will likely focus on achieving unprecedented precision in genome editing through refined control of repair pathway choice. This includes the development of more specific inhibitors targeting alternative pathways, temporal control of Cas9 activity to coincide with HDR-permissive cell cycle stages, and engineered Cas9 variants that bias repair toward desired outcomes. As our understanding of the hierarchical regulation of DSB repair deepens, so too will our ability to harness these pathways for therapeutic genome engineering, potentially enabling correction of disease-causing mutations with clinical efficacy.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are among the most cytotoxic forms of DNA damage, with a single unrepaired break capable of triggering apoptosis or leading to genomic instability that drives carcinogenesis [11]. In vertebrate cells, non-homologous end joining stands as the predominant DSB repair pathway, responsible for resolving up to ~80% of all DSBs throughout the cell cycle [11] [12]. This pathway functions as a molecular "first responder" that directly ligates broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template, distinguishing it from the more accurate but cell cycle-restricted homology directed repair (HDR) pathway [13] [3]. The evolutionary conservation of NHEJ from bacteria to humans underscores its fundamental role in genome maintenance, though its error-prone nature represents a necessary compromise between speed and fidelity that has profound implications for health and disease [13] [14].

The core function of NHEJ revolves around its ability to recognize, process, and ligate DSBs with minimal end resection, enabling rapid repair but often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site [15]. This error-prone characteristic presents a double-edged sword: while essential for maintaining chromosomal integrity, it can also introduce mutations that contribute to carcinogenesis and other pathological states [14]. Nevertheless, NHEJ remains indispensable for vertebrate development and immune system function, particularly in V(D)J recombination, where programmed DSBs are repaired to generate antibody diversity [13] [11].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major DSB Repair Pathways

| Feature | NHEJ | Homology Directed Repair (HDR) | Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | None | Homologous template (sister chromatid, donor DNA) | Microhomology regions (2-20 bp) |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases (especially G0/G1) | S and G2 phases | All phases |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (often creates indels) | High fidelity | Error-prone (deletes sequence between microhomologies) |

| Primary Proteins | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XLF, XRCC4, Ligase IV | BRCA1, Rad51, Rad52, Rad54 | Pol θ, PARP1, MRE11, CtIP |

| Physiological Role | General DSB repair, V(D)J recombination | Accurate DSB repair, restart of collapsed replication forks | Backup pathway when NHEJ is compromised |

Molecular Mechanism of NHEJ: A Stepwise Process

The NHEJ pathway employs a sophisticated molecular machinery that coordinates detection, processing, and ligation of broken DNA ends through a series of carefully orchestrated steps. This process exhibits remarkable flexibility, adapting to a wide range of DNA end configurations through iterative cycles of end processing until ligation can be achieved [11] [12].

End Recognition and Synapsis Formation

The initial response to DSBs begins with the Ku70/80 heterodimer, a ring-shaped protein complex that slides onto DNA ends immediately following break formation [11] [12]. Ku functions as a critical recruitment hub, serving as the primary damage sensor that initiates NHEJ complex assembly. Once bound to DNA, Ku recruits DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), forming the DNA-PK holoenzyme [11]. DNA-PKcs plays dual roles in both promoting synapsis (the bringing together of broken DNA ends) and phosphorylating downstream repair factors [11]. Recent structural studies reveal that DNA-PKcs creates a molecular stage upon which other NHEJ components assemble, with its kinase activity allosterically regulated by complex formation [15].

Figure 1: The Core NHEJ Pathway - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps of non-homologous end joining, from initial break recognition to final ligation.

End Processing: Nucleases and Polymerases

Most naturally occurring DSBs possess damaged or non-ligatable termini that require processing before ligation can occur. The NHEJ pathway employs specialized enzymes to address these incompatible ends:

- Artemis nuclease functions in complex with DNA-PKcs to open DNA hairpins formed during V(D)J recombination and processes certain types of IR-induced DSBs [11]. Artemis possesses both endonuclease and 5' exonuclease activities that trim damaged termini [12].

- Pol λ and Pol μ, members of the X-family DNA polymerases, fill gaps during NHEJ through their templated and untemplated synthesis activities [13] [11]. These specialized polymerases exhibit unique properties that facilitate synthesis on imperfectly aligned substrates, with Pol μ particularly adept at extending unpaired primer termini [11].

- PNKP (polynucleotide kinase phosphatase) processes terminally blocked ends by phosphorylating 5' hydroxyl groups and dephosphorylating 3' phosphate groups, creating conventional 5' phosphate and 3' hydroxyl termini suitable for ligation [11].

A groundbreaking 2025 study revealed that NHEJ employs distinct mechanisms to repair each strand of a DSB, with simpler breaks joined near-simultaneously while more complex end structures require obligatorily ordered repair where the first strand repaired serves as a template for the second [16]. This enforced asymmetry can extend to the specific polymerases employed and whether they incorporate ribonucleotides (rNTPs) or deoxyribonucleotides [16].

Ligation Complex Assembly

The final ligation step is catalyzed by the DNA Ligase IV complex, consisting of the catalytic subunit Lig4 and its essential cofactor XRCC4 [13] [11]. This complex exhibits unique flexibility among vertebrate ligases, capable of joining ends with terminal mismatches and small gaps [11]. XRCC4-like factor (XLF) interacts with the XRCC4/Lig4 complex and promotes re-adenylation of DNA ligase IV after ligation, effectively "recharging" the enzyme for multiple rounds of catalysis [13]. Recent evidence suggests that XLF and PAXX function redundantly in stabilizing synaptic complexes, explaining why single deletions of these factors produce relatively mild phenotypes while combined deficiencies are catastrophic [11].

NHEJ in the Cellular Context: Regulation and Physiological Roles

Pathway Choice and Cell Cycle Regulation

The decision between NHEJ and alternative repair pathways represents a critical juncture in cellular response to DSBs. This choice is primarily governed by whether a break undergoes 5'→3' end resection, which commits the break to HDR, alt-EJ, or SSA while effectively preventing NHEJ [11]. Key regulatory mechanisms include:

- Cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk1) activity phosphorylates the nuclease Sae2, permitting resection initiation and thereby restricting HDR to S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available as templates [13].

- Competition between Ku and the MRN (Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) complex at break ends, with Ku binding inhibiting resection while MRN promotes it [11].

- Chromatin environment factors including 53BP1, which shields breaks from resection, and BRCA1, which promotes resection [11].

This regulatory framework ensures that NHEJ dominates in G0/G1 phases when no homologous template is available, while HDR activity peaks in S/G2 phases [13] [11].

Essential Physiological Functions

NHEJ plays indispensable roles in several critical biological processes:

- V(D)J Recombination: The generation of diverse antibody and T-cell receptor repertoires requires programmed DSBs that are repaired by NHEJ [13] [11]. During this process, the specialized polymerase terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) adds non-templated nucleotides to break ends, maximizing junctional diversity [11]. Patients with mutations in NHEJ genes exhibit severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) due to defective V(D)J recombination [13].

- Telomere Maintenance: While NHEJ-mediated joining of telomeres is normally prevented by protective caps, NHEJ proteins paradoxically contribute to proper telomere function. Ku localizes to telomeres and its deletion leads to telomere shortening, though it also protects against inappropriate telomere fusions [13].

- Neural Development: Hypomorphic mutations in LIG4 and XLF cause microcephaly and other neurological defects, highlighting the importance of NHEJ in neurodevelopment [13].

Table 2: Human Diseases Associated with NHEJ Defects

| Gene Defect | Syndrome | Clinical Features | Cellular Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIG4/XRCC4 | LIG4 Syndrome | Microcephaly, growth deficiency, combined immunodeficiency, developmental delay | Radiosensitivity, defective V(D)J recombination |

| XLF | XLF-SCID | Severe combined immunodeficiency, microcephaly, growth retardation | Radiosensitivity, defective V(D)J recombination |

| Artemis | Artemis-SCID | Severe combined immunodeficiency (without neurological features) | Radiosensitivity, defective hairpin opening in V(D)J recombination |

| DNA-PKcs | SCID (rare) | Severe combined immunodeficiency | Radiosensitivity, defective V(D)J recombination |

Experimental Analysis of NHEJ

Methodologies for Assessing NHEJ Activity

Researchers employ multiple approaches to investigate NHEJ function and efficiency:

CRISPR-Cas9-Based Knock-In Assays: Recent advances in analyzing NHEJ function utilize CRISPR-mediated endogenous tagging followed by long-read amplicon sequencing. In a 2025 study, researchers electroporated RPE1 cells with Cas nuclease RNP complexes and donor DNA, then treated cells with pathway-specific inhibitors for 24 hours [17]. Genomic DNA was extracted, target sites were amplified by PCR, and sequencing reads were categorized using computational frameworks like "knock-knock" to classify DSB repair outcomes into precise HDR, indels, or imprecise integration events [17]. This approach enables quantitative assessment of how NHEJ inhibition alters repair distribution.

Cell Survival and Mutagenesis Assays: Traditional methods for evaluating NHEJ include measuring cellular sensitivity to DSB-inducing agents (e.g., ionizing radiation) and quantifying mutation spectra at endogenous loci. A yeast-based system employing reversions of frameshift alleles (lys2ΔBglII and hom3-10) demonstrated that NHEJ deficiency reduces replication-independent mutation frequency by approximately 50%, with characteristic mutation signatures showing small deletions within mononucleotide repeats [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for NHEJ Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | NHEJ pathway inhibitor | Increases HDR efficiency in CRISPR knock-in by suppressing competing NHEJ [17] |

| ART558 | POLQ inhibitor (MMEJ suppression) | Reduces large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels at Cas9 cut sites [17] |

| D-I03 | Rad52 inhibitor (SSA suppression) | Decreases asymmetric HDR and other imprecise integration events [17] |

| Ku70/80 antibodies | Immunofluorescence and Western blot | Detection of Ku recruitment to DSB sites and protein expression levels |

| DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., NU7441) | Kinase activity blockade | Investigation of DNA-PKcs functional roles in synapsis and end processing |

| Long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) | Comprehensive repair outcome analysis | Characterization of NHEJ-mediated indel spectra and complex rearrangements [17] |

NHEJ in Genome Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Implications for CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

In CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the balance between NHEJ and HDR critically determines editing outcomes. NHEJ represents the dominant repair pathway in most cell types, leading to predominant indel formation rather than precise edits [3] [17]. This propensity makes NHEJ ideal for gene knockout strategies but challenging for precise knock-in approaches. Recent research demonstrates that even with NHEJ inhibition, imprecise repair persists through alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA, requiring multi-pathway suppression for optimal HDR efficiency [17].

Strategic inhibition of NHEJ using compounds such as Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 increases precise knock-in efficiency approximately 3-fold (from 5.2% to 16.8% in Cpf1-mediated HNRNPA1 tagging and from 6.9% to 22.1% in Cas9-mediated RAB11A tagging) [17]. However, perfect HDR events still account for less than half of all integration events even with NHEJ inhibition, highlighting the significant contribution of alternative repair pathways [17].

Cancer Therapeutic Strategies

The dual role of NHEJ in maintaining genomic stability while contributing to mutagenesis presents unique opportunities for cancer therapy:

- NHEJ Inhibition can sensitize tumors to DNA-damaging agents like ionizing radiation and chemotherapeutics. DNA-PKcs inhibitors are under clinical investigation for their potential to enhance radiotherapy efficacy [18].

- Synthetic Lethality Approaches exploit cancer-specific repair deficiencies. For example, HR-deficient tumors (common in BRCA-mutated cancers) show heightened sensitivity to NHEJ inhibition [18].

- Crosslinker Response Modulation represents a promising avenue, as evidenced by recent findings that DNA-PKcs deficiency increases resistance to cisplatin and carboplatin, while Pol θ inhibition sensitizes cells to these agents, particularly in NHEJ- and HR-deficient contexts [18].

Figure 2: DSB Repair Pathway Competition - This diagram illustrates how double-strand breaks can be shunted to different repair pathways with distinct mutational outcomes, influenced by cell cycle phase and experimental manipulation.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The understanding of NHEJ continues to evolve with recent discoveries revealing unexpected complexity. The 2025 finding that NHEJ employs distinct mechanisms to repair each strand of a DSB, with potential differential use of polymerases and nucleotide substrates, opens new avenues for investigation [16]. Key emerging research directions include:

- Structural Dynamics of Repair Complexes: Advanced cryo-EM studies are elucidating how supercomplexes like DNA-PK transition between long-range and short-range synaptic states during repair [16] [11].

- Pathway Interplay in Disease Contexts: The complex interplay between NHEJ, HDR, and alternative pathways in chemotherapy response suggests new combination therapy approaches [18].

- RNA Incorporation in DNA Repair: The discovery that NHEJ polymerases can incorporate ribonucleotides into repair junctions raises fundamental questions about the biological implications of RNA-DNA hybrids in genome maintenance [16].

As these research fronts advance, NHEJ will continue to represent both a therapeutic target and a fundamental biological process whose understanding essential for manipulating genome stability in health and disease.

In the landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the competition between DNA repair pathways fundamentally shapes experimental and therapeutic outcomes. While error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) serves as the cell's rapid "first responder" to double-strand breaks (DSBs), homology-directed repair (HDR) represents the high-fidelity pathway essential for precise genetic modifications [4] [7]. This whitepaper examines the molecular machinery of HDR, its competitive relationship with NHEJ, and advanced methodologies to enhance HDR efficiency for research and therapeutic applications. The critical distinction between these pathways lies in their fidelity and mechanisms: NHEJ directly ligates broken DNA ends without a template, frequently introducing small insertions or deletions (indels), whereas HDR utilizes homologous donor sequences to achieve nucleotide-precise repair [3] [7]. For researchers pursuing accurate gene knockins, point mutations, or therapeutic corrections, understanding and manipulating HDR is paramount, particularly given its natural inefficiency relative to NHEJ.

Molecular Mechanisms of HDR and Competing Pathways

The HDR Pathway: A Step-by-Step Mechanism

Homology-directed repair is a complex, multi-stage process that requires numerous protein factors and is restricted to specific cell cycle phases. The mechanism unfolds through coordinated steps:

- DSB Recognition and End Resection: The MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) recognizes double-strand breaks and initiates 5' to 3' end resection in conjunction with CtIP, creating short 3' single-stranded overhangs [7].

- Extended Resection: Exonuclease 1 (Exo1) and the Dna2/BLM helicase complex extend the resection, generating substantial 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails [7].

- RPA and RAD51 Loading: Replication protein A (RPA) coats and protects the ssDNA tails, subsequently replaced by RAD51 with assistance from BRCA2 and other mediators to form a nucleoprotein filament [7].

- Strand Invasion: The RAD51-ssDNA filament performs a homology search and invades the donor template, forming a displacement loop (D-loop) structure [7].

- DNA Synthesis and Resolution: DNA polymerase extends the invading strand using the homologous donor as a template, with repair proceeding primarily via synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) in CRISPR applications, yielding non-crossover products [7].

Competing Repair Pathways

HDR operates within a competitive landscape of DNA repair mechanisms, each with distinct fidelity outcomes:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The dominant competing pathway, NHEJ initiates when Ku70-Ku80 heterodimers bind DSB ends, recruiting DNA-PKcs, Artemis nuclease, and finally XRCC4-DNA ligase IV for ligation [7] [19]. This pathway operates throughout the cell cycle and is error-prone, frequently generating indels that disrupt gene function [4].

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): An alternative error-prone pathway requiring 2-20 nucleotide microhomologies, mediated by DNA polymerase theta (Pol θ) and PARP1, typically resulting in moderate-to-large deletions [7].

- Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): Requires extensive homologous flanking sequences (>20 nucleotides) and involves RAD52-mediated annealing, resulting in significant deletions between homologous regions [7].

The following diagram illustrates the competitive decision landscape between these pathways following a CRISPR-induced double-strand break:

Quantitative Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways

Pathway Characteristics and Efficiencies

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of major DNA repair pathways, highlighting their distinct operational requirements and editing outcomes:

Table 1: Characteristics of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Genome Editing

| Parameter | HDR | NHEJ | MMEJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | Homologous donor template (plasmid, ssODN) | None | Microhomology regions (2-20 bp) |

| Cell Cycle Phase | S and G2 phases | All phases | S and G2 phases |

| Key Protein Factors | RAD51, BRCA2, MRN complex, CtIP | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, Ligase IV | Pol θ, PARP1, RAD52 |

| Repair Fidelity | High (precise) | Low (error-prone) | Low (error-prone) |

| Primary Outcomes | Precise knockins, point mutations, gene corrections | Small insertions/deletions (indels) | Intermediate-sized deletions |

| Typical Efficiency | Low (0.1-20%) | High (can exceed 80%) | Variable (5-30%) |

| Major Applications | Gene knockins, precise mutations, therapeutic correction | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Gene disruption with larger deletions |

HDR Enhancement Strategies and Efficiencies

Recent research has developed multiple strategies to overcome HDR's natural inefficiency. The following table quantifies the effectiveness of various HDR enhancement approaches:

Table 2: HDR Enhancement Strategies and Reported Efficacy

| Enhancement Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Reported HDR Increase | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibition (e.g., AZD7648) [19] | DNA-PKcs inhibition to suppress competing NHEJ | 2- to 5-fold increase | Increased kilobase-scale deletions (up to 43.3% of reads) and chromosomal abnormalities |

| RAD51-Preferred ssDNA Modules [20] | Incorporation of specific sequences (e.g., "TCCCC") to enhance RAD51 binding and donor recruitment | Up to 90.03% (median 74.81%) HDR efficiency when combined with NHEJ inhibition | Requires optimization of module placement (5' end preferred) |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization [4] [7] | Synchronizing cells to S/G2 phases where HDR is active | 2- to 3-fold increase | Technically challenging, may impact cell viability |

| HDRobust Strategy [20] | Combined inhibition of error-prone pathways | Up to 90.03% HDR efficiency when combined with engineered donors | Potential unknown off-target effects |

| ssODN Donors [4] [20] | Single-stranded donors with optimized homology arms | Generally higher HDR than dsDNA donors with lower cytotoxicity | Sensitive to 3' end modifications, requires careful design |

Advanced HDR Enhancement Methodologies

Engineered Donor Molecules for Enhanced HDR

Recent breakthroughs in donor design have substantially improved HDR efficiency. The most promising approach involves engineering RAD51-preferred sequences into single-stranded DNA donors:

- Sequence Selection: Through ODN immunoprecipitation sequencing (ODIP-Seq), researchers identified specific RAD51-binding sequences (SSO9 and SSO14) containing a "TCCCC" motif that demonstrates enhanced affinity for RAD51 [20].

- Modular Integration: These RAD51-preferred sequences are incorporated as functional modules at the 5' end of ssDNA donors, as the 5' end demonstrates greater tolerance for additional sequences without compromising HDR efficiency [20].

- Mechanistic Basis: The engineered modules augment donor affinity for RAD51, facilitating recruitment to DSB sites and improving the efficiency of precise gene editing across multiple genomic loci and cell types [20].

- Combination Approaches: When modular ssDNA donors are combined with NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., M3814) or the HDRobust strategy, HDR efficiencies ranging from 66.62% to 90.03% have been achieved at endogenous loci [20].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for developing and implementing these advanced donor designs:

Strategic NHEJ Inhibition with Safety Considerations

While NHEJ inhibition represents a logical approach to enhance HDR, recent findings reveal significant safety concerns:

- DNA-PKcs Inhibition: AZD7648, a potent DNA-PKcs inhibitor, initially appeared promising by increasing apparent HDR rates to near-pure populations in short-read sequencing [19].

- Unmasked Genomic Instability: Long-read sequencing and single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that AZD7648 treatment frequently causes kilobase-scale deletions (up to 43.3% of reads), chromosome arm loss, and translocations that evade detection by standard short-read sequencing [19].

- Cell Type Considerations: These large-scale chromosomal alterations occur in both immortalized cell lines and primary cells, including CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [19].

- Practical Implications: The genomic instability associated with potent NHEJ inhibitors necessitates comprehensive genotoxicity assessment using long-read sequencing and cytogenetic methods before therapeutic application [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for HDR Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | Cas9 protein, Cas9 mRNA, nCas9 (nickase), Cas12a | Creates controlled DNA breaks while minimizing off-target effects |

| Donor Templates | ssODNs (80-200 nt), dsDNA donor plasmids, AAV donors | Provides homologous template for precise repair; ssODNs optimal for point mutations |

| HDR-Enhancing Molecules | RAD51-modular ssDNA donors, L755507 (RAD51 agonist), RS-1 (RAD51 stimulator) | Increases RAD51 activity and loading to improve HDR efficiency |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | M3814 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor), KU-0060648 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor), Scr7 (Ligase IV inhibitor) | Suppresses competing error-prone pathway; use with caution due to genomic instability risks |

| Cell Cycle Synchronizers | Nocodazole, thymidine, lovastatin | Synchronizes cells to S/G2 phases where HDR is active |

| Validation Tools | Long-read sequencing (ONT), ddPCR, Sanger sequencing, fluorescent reporters | Comprehensive assessment of editing outcomes including large-scale alterations |

Experimental Protocol: High-Efficiency HDR Using Modular Donors

Donor Design and Validation

- Modular ssDNA Design: Design ssDNA donors (90-200 nt) with 30-40 nt homology arms flanking the desired edit. Incorporate RAD51-preferred sequences (e.g., 5'-TCCCC-3') at the 5' end as a functional module [20].

- Control Donors: Include parallel controls with scrambled sequences or no additional modules to quantify enhancement effects.

- Quality Control: Purify ssODNs using HPLC or PAGE purification to ensure integrity and minimize truncated products.

Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Cell Line Selection: Utilize actively dividing cells with robust HDR capacity (e.g., HEK293T, RPE-1, or target primary cells if applicable).

- Cell Cycle Synchronization (Optional): Treat cells with 2 mM thymidine for 18 hours, wash thoroughly, and release into fresh media for 4-6 hours before transfection to enrich for S-phase cells [7].

- RNP Complex Formation: Combine 5 μg recombinant Cas9 protein with 2.5 μg sgRNA in nucleofection buffer, incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to form ribonucleoprotein complexes.

- Co-delivery: Mix RNP complexes with 2-5 μg modular ssDNA donor per 10^6 cells and deliver via nucleofection using cell-type specific programs.

HDR Enhancement Treatment

- Small Molecule Application: If using NHEJ inhibitors, add M3814 (200-500 nM) or alternative inhibitors immediately post-transfection and maintain for 24-48 hours [20] [19].

- Alternative Enhancement: For RAD51 agonists, add RS-1 (5-10 μM) post-transfection to stimulate RAD51 nucleofilament formation.

Analysis and Validation

- Short-Range PCR Amplicon Sequencing: At 72-96 hours post-editing, harvest cells and amplify target locus with 150-300 bp amplicons for Illumina sequencing to assess initial HDR rates.

- Long-Range PCR and Sequencing: Amplify 3-6 kb regions surrounding the target site for Oxford Nanopore or PacBio sequencing to detect large deletions and rearrangements [19].

- Functional Assays: For fluorescent reporters, analyze by flow cytometry at 5-7 days post-editing to quantify functional protein expression.

- Clonal Isolation and Characterization: For precise quantification, isolate single-cell clones and characterize by Sanger sequencing, southern blotting, or ddPCR to confirm precise editing and rule out large-scale alterations.

Homology-directed repair remains the cornerstone of precise genome editing, with recent advances in donor engineering pushing HDR efficiencies to previously unattainable levels. The development of RAD51-preferred sequence modules represents a particularly promising direction, achieving remarkable HDR rates without exogenous protein fusions or complex chemical modifications [20]. However, the pursuit of HDR efficiency must be tempered by careful safety considerations, as evidenced by the genomic instability risks associated with potent NHEJ inhibitors like AZD7648 [19]. The research community now faces the challenge of implementing robust screening methodologies that detect not only precise edits but also large-scale genomic alterations. As HDR-based therapies advance toward clinical application, the strategic balance between efficiency and safety will ultimately determine successful translation from bench to bedside.

The faithful repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is critical for maintaining genomic integrity and preventing oncogenic transformation. Cells primarily utilize two major pathways for DSB repair: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). A third error-prone pathway, microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), also contributes to DSB repair under specific conditions. These pathways do not operate in isolation but engage in a tightly regulated competition, the outcome of which determines whether a DSB is repaired faithfully or in a mutagenic manner. The equilibrium of this competition is governed principally by two factors: the cell cycle phase and a complex network of key regulatory proteins that sense the cellular context and direct the repair machinery accordingly. Understanding this delicate balance is not only fundamental to basic biology but also crucial for developing targeted cancer therapies that exploit specific DNA repair deficiencies in tumors [21] [22].

DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

Canonical Non-Homologous End Joining (c-NHEJ)

Canonical Non-Homologous End Joining (c-NHEJ) is considered the cell's "first responder" to DSBs and operates throughout the cell cycle, dominating in the G0/G1 phases. It functions by directly ligating broken DNA ends with minimal processing [21] [7]. The process begins when the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recognizes and binds to the broken DNA ends, protecting them from resection [7] [22]. This binding recruits DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), which forms the active DNA-PK complex and aligns the broken ends [7]. Subsequently, nucleases like Artemis may process the ends, and polymerases (Pol μ or Pol λ) may fill in small gaps. Finally, the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex catalyzes the ligation step [7]. While c-NHEJ is fast and efficient, it is potentially mutagenic, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction [23].

Homologous Recombination (HR)

Homologous Recombination (HR) is a high-fidelity repair mechanism that predominates in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when a sister chromatid is available as a repair template [21] [7]. HR initiation requires extensive processing of the DNA ends. The MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1), along with CtIP, initiates end resection, creating short 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [21] [7]. Long-range resection by enzymes like EXO1 and the DNA2/BLM helicase complex then generates extensive 3' ssDNA tails. These tails are rapidly coated by Replication Protein A (RPA), which is later replaced by the RAD51 recombinase to form a nucleoprotein filament. This filament facilitates strand invasion into the homologous donor sequence, leading to DNA synthesis using the sister chromatid as a template. The process concludes with the restoration of the DNA duplex, resulting in error-free repair [21] [7] [22].

Alternative Error-Prone Pathways

Besides c-NHEJ and HR, cells possess alternative, more mutagenic repair pathways, namely Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ), also known as alternative-EJ (alt-EJ), and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) [21].

Both MMEJ and SSA require end resection. MMEJ utilizes short microhomology regions (5-25 base pairs) internal to the broken ends for annealing. The process is mediated by PARP1 and DNA polymerase theta (Pol θ) and typically results in deletions of the sequence between the microhomologous regions [7] [22]. SSA requires longer homologous repeats (often >20 nucleotides) flanking the DSB. After extensive resection, the homologous sequences are annealed by RAD52, leading to the deletion of one repeat and the entire intervening sequence, making SSA highly mutagenic [21] [7] [23].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major DSB Repair Pathways

| Repair Pathway | Cell Cycle Phase | Key Initiating Factor(s) | Template Required | Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-NHEJ | Throughout, dominant in G0/G1 | Ku70/Ku80 | None | Error-Prone |

| HR | S and G2 | MRN Complex, CtIP | Sister Chromatid/Homologous Chromosome | Error-Free |

| MMEJ | S and G2 [22] | PARP1, Pol θ | Microhomology | Highly Error-Prone |

| SSA | S and G2 [21] | RAD52 | Flanking Homologous Repeats | Highly Error-Prone |

The Critical Role of the Cell Cycle

The cell cycle phase is a primary determinant of DSB repair pathway choice, primarily through the regulation of DNA end resection [21]. Resection is the critical step that commits a DSB to the homology-dependent repair pathways (HR, SSA, or MMEJ) and simultaneously precludes c-NHEJ.

The promotion of resection in S and G2 phases is largely driven by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity [21]. CDKs phosphorylate key resection factors, activating them and promoting their recruitment to DSB sites. Key targets include:

- CtIP: CDK-mediated phosphorylation promotes its interaction with BRCA1, facilitating the initiation of resection [21].

- EXO1: Phosphorylation enhances its resection activity, and impairment of this phosphorylation attenuates HR [21].

- Dna2 and Sae2 (yeast CtIP homolog): Phosphorylation promotes efficient end resection [21].

Consequently, in G1 phase, low CDK activity results in minimal resection, favoring c-NHEJ. In contrast, in S/G2 phases, high CDK activity promotes robust resection, enabling homology-dependent repair [21] [7]. This cell-cycle-dependent regulation ensures that HR is active only when a homologous template is available.

Figure 1: Cell Cycle Regulation of DSB Repair Pathway Choice. The decision between c-NHEJ and resection-dependent pathways (HR, SSA, MMEJ) is primarily governed by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity, which is low in G1 and high in S/G2 phases. High CDK activity promotes end resection, committing the break to homology-based repair.

Key Protein Regulators of Pathway Choice

The choice between DSB repair pathways is orchestrated by a complex interplay of regulatory proteins that act as molecular switches.

The BRCA1-53BP1 Antagonism

A central regulatory axis governing the resection step is the antagonism between 53BP1 and BRCA1 [21] [22].

- 53BP1 and its effector complexes (e.g., Shieldin, Rif1) promote c-NHEJ and inhibit resection. They act by blocking the access of resection factors like CtIP to the DNA ends, thereby protecting the ends from nucleolytic degradation [21] [7].

- BRCA1, in complex with CtIP and the MRN complex, promotes end resection and directs repair toward HR. It antagonizes 53BP1's end-protection function [21] [22].

The balance between BRCA1 and 53BP1 is crucial for pathway choice. For instance, in BRCA1-deficient cells, 53BP1 activity is upregulated, directing repair toward c-NHEJ and causing PARP inhibitor resistance. Loss of 53BP1 in this context restores resection and HR [21].

Additional Key Regulators

- ATM Kinase: Activated by the MRN complex at DSBs, ATM phosphorylates numerous substrates, including members of the MRN complex, BRCA1, CtIP, and EXO1, thereby promoting efficient resection and HR [21] [22].

- DNA-PKcs: A key kinase in c-NHEJ. In G1, it can phosphorylate and inhibit ATM signaling, favoring NHEJ. In G2, its autophosphorylation and dissociation from DSB sites allow EXO1 to initiate resection for HR [22].

- RPA and RAD51: After resection, RPA coats ssDNA to prevent secondary structure formation and spontaneous annealing. It is subsequently displaced by RAD51 to form the presynaptic filament for strand invasion in HR. The competition between RPA and RAD51 for ssDNA binding adds another layer of regulation [21].

- REV7 (Mad2L2): Acts downstream of 53BP1 and Rif1 to inhibit resection and promote c-NHEJ [21].

Table 2: Key Protein Regulators of DSB Repair Pathway Competition

| Protein/Complex | Primary Function | Effect on Pathway Choice |

|---|---|---|

| 53BP1 (with Rif1, Shieldin) | Protects DNA ends from resection | Promotes c-NHEJ, Inhibits HR |

| BRCA1 (with CtIP, MRN) | Promotes initiation of DNA end resection | Promotes HR, Antagonizes 53BP1 |

| ATM Kinase | Phosphorylates key resection factors (CtIP, EXO1, BLM) | Promotes HR and other resection-dependent pathways |

| DNA-PKcs | Core c-NHEJ factor; regulates ATM activity | Promotes c-NHEJ, Inhibits HR in G1 |

| REV7 (Mad2L2) | Inhibits DNA end resection | Promotes c-NHEJ downstream of 53BP1 |

| RPA | Binds resected ssDNA, prevents microhomology annealing | Regulates access to HR vs. SSA/MMEJ |

| RAD52 | Catalyzes strand annealing | Essential for SSA pathway |

Figure 2: Protein Network Regulating DSB Repair Pathway Choice. A simplified view of the key antagonistic proteins that influence whether a DSB is repaired by c-NHEJ or HR. The 53BP1 axis protects DNA ends from resection, promoting c-NHEJ, while the BRCA1 axis promotes resection, enabling HR. Factors like ATM and DNA-PKcs further fine-tune this balance.

Experimental Approaches and Quantification

Understanding pathway competition requires robust methods to quantify repair outcomes. Recent advances in reporter assays and high-throughput screening have provided powerful tools for researchers.

Multi-Pathway Reporter Assays

Innovative reporter systems, such as the DSB-Spectrum reporters, enable simultaneous quantification of multiple DSB repair pathways from a single Cas9-induced break [23]. These are typically stably integrated into the genome and use fluorescent proteins to distinguish between repair outcomes.

- Design Principle: A single construct contains engineered sequences that, when cut by Cas9, can be repaired by different pathways, each producing a distinct fluorescent signal (e.g., BFP for error-free c-NHEJ, GFP for HR, and no fluorescence for mutagenic pathways) [23].

- Application: Using such a system, researchers demonstrated that inhibiting DNA-PKcs to suppress c-NHEJ not only increased HR but also substantially increased mutagenic SSA repair, highlighting the complex cross-talk between pathways [23].

Digital PCR for Endogenous Loci Quantification

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays allow precise, simultaneous quantification of HDR and NHEJ events at endogenous genomic loci without the need for cloning and sequencing [24].

- Workflow: After nuclease transfection, genomic DNA is extracted. The DNA is partitioned into thousands of droplets with primers and probes specific for the HDR allele (e.g., with a point mutation), the NHEJ-disrupted allele, and a reference locus. The number of positive droplets for each target is counted, allowing absolute quantification of editing events [24].

- Key Finding: Using this method, studies have shown that the HDR/NHEJ ratio is highly dependent on the gene locus, nuclease platform (e.g., Cas9, TALEN, Cas9 nickase), and cell type, challenging the simplistic view that NHEJ is always more frequent than HDR [24].

High-Throughput Chemical Screening

Protocols have been established for high-throughput screening (HTS) of chemical libraries to identify small molecules that enhance HDR efficiency, which is crucial for improving precise genome editing [25].

- Example Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: HEK293T cells are cultured and seeded in 96-well plates coated with poly-D-lysine to enhance adhesion.

- Transfection: Cells are transfected with CRISPR-Cas9 components and a donor DNA template containing homology arms.

- Chemical Treatment: A library of small molecules is added to the wells.

- HDR Readout: A robust readout, such as β-galactosidase activity from a successfully integrated LacZ reporter, is measured colorimetrically using a plate reader.

- Viability Assay: A parallel viability assay (e.g., measuring metabolic activity) is performed to normalize HDR efficiency and exclude cytotoxic compounds [25].

- Outcome: This approach allows for the rapid identification of compounds that specifically enhance HDR without adversely affecting cell health.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Studying DSB Repair Pathway Competition

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| DSB-Spectrum Reporter | Fluorescent multi-pathway reporter construct [23] | Simultaneously quantify c-NHEJ, HR, and SSA at a single genomic locus via flow cytometry. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of nucleic acids [24] | Precisely measure HDR and NHEJ frequencies at endogenous loci without cloning. |

| Cas9 Nuclease Variants | Wild-type, D10A nickase (Cas9n), FokI-dCas9 fusions [24] | Induce DSBs or nicks; different platforms alter the balance of repair outcomes. |

| Poly-D-Lysine | Coating polymer [25] | Enhance cell adhesion for transfection and screening in weakly adherent lines like HEK293T. |

| ONPG (o-Nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) | Colorimetric substrate for β-galactosidase [25] | Detect successful HDR events in reporter-based screens. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | e.g., DNA-PKcs, ATM, PARP inhibitors [23] [22] | Chemically perturb specific pathways to study cross-talk and compensation. |

The competition between DNA double-strand break repair pathways is a meticulously orchestrated process central to genomic integrity. The cell cycle, through the action of CDKs, establishes a fundamental temporal window for homology-dependent repair. Within this framework, a dynamic network of key proteins, most notably the antagonistic duo of 53BP1 and BRCA1, executes fine control over the initiation of DNA end resection—the critical commitment step. The resulting balance between c-NHEJ, HR, and error-prone pathways like MMEJ and SSA determines the fidelity of repair. Disruption of this equilibrium is a hallmark of cancer and a target for therapeutic intervention. Modern tools, including multi-pathway reporters and precise quantification methods, continue to reveal the profound complexity of this regulatory network, offering new insights for both basic science and the development of targeted therapies that exploit DNA repair deficiencies in disease.

The cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is critical for maintaining genomic integrity. For decades, repair pathway discussions have centered on two primary mechanisms: classical non-homologous end joining (C-NHEJ), an error-prone ligation process active throughout the cell cycle, and homology-directed repair (HDR), an error-free pathway that utilizes sister chromatid templates during S and G2 phases [4]. However, this binary view is insufficient to explain the complexity of DSB repair outcomes. Two additional pathways, microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA), play significant roles in DSB repair, particularly when primary pathways are compromised or under specific cellular contexts [26] [27].

MMEJ and SSA are often categorized as "alternative" end-joining pathways, yet they constitute distinct mechanistic entities with unique genetic requirements and mutational signatures [27] [28]. Both pathways are inherently mutagenic, typically resulting in deletions that can jeopardize genomic stability, but also provide backup repair capacity essential for cell survival [26] [29]. Understanding these pathways is paramount in cancer research, as their dysregulation contributes to oncogenic transformations and presents therapeutic vulnerabilities [30] [31]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of MMEJ and SSA mechanisms, regulatory networks, experimental methodologies, and their implications in disease and therapy.

Pathway Mechanisms and Genetic Requirements

Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ)

MMEJ repairs DSBs through the alignment of microhomologous sequences (typically 5-25 base pairs) internal to the broken ends prior to joining [26] [28]. Unlike C-NHEJ, MMEJ operates independently of core NHEJ factors such as Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, and Ligase IV [28]. The distinguishing feature of MMEJ repair is the characteristic deletions flanking the original break site that preserve the microhomology region used for alignment [26].

The MMEJ mechanism proceeds through several coordinated steps:

- End resection: The MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex initiates 5'-3' end resection to generate single-stranded DNA overhangs [26] [28].

- Microhomology search and annealing: Resected ends align through complementary microhomologous sequences, a process facilitated by PARP1 and Polθ [27] [28].

- Flap removal and gap filling: Non-homologous 3' ssDNA flaps are excised, and any gaps are filled by DNA polymerases, with Polθ playing a specialized role in mammalian cells [28].

- Ligation: DNA Ligase III/XRCC1 complexes complete the joining process [26].

Figure 1: MMEJ involves end resection, microhomology annealing, and ligation, resulting in characteristic deletions.

Single-Strand Annealing (SSA)

SSA repairs DSBs between two direct repeat sequences oriented in the same direction [27] [29]. This pathway is distinct from other DSB repair mechanisms in its requirement for significantly longer homologous regions (often hundreds of base pairs) and its exclusive production of deletion mutations without a requirement for RAD51 [27] [29].

The SSA mechanism involves:

- * Extensive end resection*: DSB ends undergo substantial 5'-3' resection that extends through the repeat sequences, generating long 3' ssDNA overhangs [27].

- Annealing of complementary repeats: The RAD52 protein facilitates annealing of the exposed homologous repeat sequences [27] [29].

- Flap removal: Non-homologous 3' ssDNA tails are cleaved by the ERCC1-XPF endonuclease, with potential involvement of the Rad1-Rad10 complex in yeast [27] [29].

- Gap filling and ligation: Any remaining gaps are filled by DNA polymerases, and the nicks are sealed by DNA ligases to complete repair [27].

Figure 2: SSA uses extensive resection and RAD52-mediated annealing of direct repeats, deleting the intervening sequence.

Comparative Analysis of DSB Repair Pathways

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major DSB Repair Pathways

| Feature | C-NHEJ | MMEJ | SSA | HDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No | No | Yes (direct repeats) | Yes (sister chromatid) |

| Homology Length | None | 5-25 bp microhomology | >25 bp (often 100s of bp) | Extensive homology |

| Key Proteins | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4-Lig4 | PARP1, Polθ, Lig3-XRCC1, MRN | RAD52, ERCC1-XPF, MRN | RAD51, BRCA2, RAD54 |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (small indels) | Highly mutagenic (large deletions) | Mutagenic (deletions) | High fidelity |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases | S/G2 phase [28] | S/G2 phase | Late S/G2 phase |

| Deletion Outcome | Small or none | Deletion with microhomology at junction | Complete deletion between repeats | Accurate restoration |

Table 2: Genetic Requirements for MMEJ and SSA Across Model Organisms

| Factor | Function | MMEJ Requirement | SSA Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRN Complex | End resection, end bridging | Required [26] [28] | Required [27] |

| CtIP | Promotes end resection | Required in mammals [26] | Required [27] |

| RAD52 | DNA annealing, mediator | Not required [27] | Essential [27] [29] |

| RAD51 | Strand invasion, homology search | Not required | Not required (inhibitory) [27] |

| PARP1 | End binding, synapsis promotion | Required [27] [28] | Not required [27] |

| DNA Polθ | Gap filling, microhomology annealing | Required in mammals [28] | Not required |

| ERCC1-XPF | 3' flap endonuclease | Possibly involved | Essential [27] |

| Ligase III | Ligation of ends | Required [28] | Not fully determined |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Established Assays for Pathway Analysis

Researchers employ both plasmid-based and chromosomal assays to study MMEJ and SSA mechanisms:

Plasmid-based recombination assays involve transforming linearized plasmid DNA with defined end structures into cells [26]. For MMEJ studies, oligonucleotides with microhomology regions are ligated to linearized plasmids prior to transformation [26]. SSA assays utilize plasmids containing interrupted reporter genes with direct repeats flanking the DSB site; successful SSA restores reporter gene function through deletion of the intervening sequence [27].

Chromosomal DSB repair assays utilize rare-cutting endonucleases (HO, I-SceI) or CRISPR/Cas9 to create site-specific breaks in chromosomal DNA [26] [17]. These systems can be engineered with microhomology regions or direct repeats at defined distances from the break site to specifically monitor MMEJ or SSA events [26] [29]. Newer technologies using zinc-finger nucleases or CRISPR/Cas9 have enhanced the precision of these assays [26] [17].

High-throughput translocation sequencing approaches detect chromosomal translocations resulting from error-prone repair, with MMEJ contributing significantly to translocations bearing microhomology at junctions [26]. Class switch recombination (CSR) in developing B-cells provides a physiological context for studying MMEJ, as repair of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) breaks in switch regions often occurs via MMEJ, especially in C-NHEJ deficient cells [26].

Protocol: Analyzing MMEJ and SSA in CRISPR-Mediated Endogenous Tagging

A recent comprehensive study detailed a method to dissect the contributions of multiple DSB repair pathways in CRISPR-mediated knock-in [17]:

Cell Preparation and Transfection:

- Utilize hTERT-immortalized RPE1 (human retinal pigment epithelial) cells or other diploid cell lines.

- Prepare donor DNA by PCR using primers containing 90-base homology arms.

- Form RNP complexes by mixing recombinant Cpf1 (or Cas9) with in vitro transcribed guide RNAs.

- Electroporate RNP complexes and donor DNA into cells using optimized parameters.

Pathway Inhibition:

- Immediately post-electroporation, treat cells with specific pathway inhibitors for 24 hours:

- NHEJ inhibition: Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2

- MMEJ inhibition: ART558 (POLQ inhibitor)

- SSA inhibition: D-I03 (Rad52 inhibitor)

- Include DMSO-only treated controls for baseline comparison.

- Immediately post-electroporation, treat cells with specific pathway inhibitors for 24 hours:

Outcome Analysis:

- After 4 days, analyze knock-in efficiency via flow cytometry for fluorescent protein tagging.

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify target loci using PCR primers flanking the integration site.

- Perform long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) for comprehensive genotyping.

- Classify repair outcomes using computational frameworks like "knock-knock" to categorize sequences as perfect HDR, imprecise integration, indels, or WT [17].

Data Interpretation:

- MMEJ inhibition typically reduces large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels.

- SSA inhibition decreases asymmetric HDR events and partial donor integrations.

- Combined pathway inhibition reveals additive effects on precise editing efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying MMEJ and SSA

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| ART558 | POLQ inhibitor targeting MMEJ | MMEJ suppression increases perfect HDR frequency in CRISPR editing [17] |

| D-I03 | Rad52 inhibitor targeting SSA | SSA suppression reduces asymmetric HDR and partial donor integration [17] |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | NHEJ pathway inhibitor | Enhancing HDR efficiency reveals competing alternative pathways [17] |

| Olaparib | PARP1 inhibitor affecting MMEJ | Established PARP1 role in MMEJ but not SSA [27] |

| I-SceI and HO endonucleases | Rare-cutting endonucleases for chromosomal DSB assays | Demonstrated kinetics and genetic requirements of SSA and MMEJ [26] [29] |

| POLQ-knockout cells | Genetic model for MMEJ deficiency | Revealed synthetic lethality with HR deficiency in cancers [28] |

Regulatory Networks and Pathway Choice

The decision between DSB repair pathways is tightly regulated throughout the cell cycle and involves competitive interactions between repair factors [26] [28]. MMEJ and SSA are both suppressed during G0/G1 phases but increase during S and G2 phases when end resection is more active [28]. Several key factors influence pathway choice:

End resection extent serves as a critical determinant: limited resection favors C-NHEJ, while extensive resection promotes MMEJ, SSA, or HDR [27]. The MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) initiates resection, with CtIP further promoting the process in mammalian cells [26] [27]. 53BP1 and RIF1 protect DNA ends from resection, favoring C-NHEJ, while their removal allows resection to proceed [27].

Competitive binding between Ku70/80 and PARP1 at DNA ends represents an early branch point, with Ku binding favoring C-NHEJ and PARP1 binding promoting MMEJ [26] [27]. Similarly, RAD52 and RAD51 compete for binding to resected DNA ends, with RAD52 directing repair toward SSA and RAD51 toward HDR [27]. Interestingly, RAD51 depletion increases SSA frequency, suggesting that RAD51 normally suppresses this mutagenic pathway [27] [29].

Chromatin context and break nature also influence pathway choice. SSA is favored when DSBs occur between long direct repeats, while MMEJ is engaged when short microhomologies are present near break ends [26] [29]. Breaks in heterochromatic regions or complex breaks with damaged termini may preferentially engage MMEJ over C-NHEJ [26].

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Roles in Carcinogenesis and Genome Instability

MMEJ and SSA contribute significantly to genomic instability through their characteristic mutagenic outcomes [26] [28]. MMEJ-associated deletions and chromosomal translocations have been implicated in oncogenic transformations, particularly in lymphoid malignancies where repair of RAG-induced breaks by MMEJ can lead to translocations between IgH and c-Myc loci [26]. Approximately half of oncogenic translocations in C-NHEJ-deficient murine models display extensive microhomology at junctions [26].

SSA-mediated deletions between dispersed repetitive elements (Alu, LINE) can eliminate tumor suppressor genes or create oncogenic fusion proteins [27]. The propensity for SSA to cause large genomic deletions makes it particularly dangerous for genome stability. Both pathways are upregulated in many cancers, with MMEJ-associated genes (POLQ, FEN1, LIG3, PARP1) frequently overexpressed [28].

Synthetic Lethality and Targeted Therapies

Therapeutic strategies exploiting MMEJ and SSA vulnerabilities show considerable promise:

POLQ inhibition exhibits synthetic lethality with homologous recombination deficiency, particularly in BRCA-mutant ovarian and breast cancers [28]. HR-deficient tumors upregulate POLQ and become dependent on MMEJ for DSB repair; POLQ inhibition selectively kills these cells while sparing normal cells with functional HR [28].

PARP inhibitors (olaparib, etc.) target both MMEJ and base excision repair, creating synthetic lethality with HR deficiency [31]. These agents have shown significant clinical success in HR-deficient cancers [31].

Combination therapies simultaneously targeting multiple repair pathways offer enhanced efficacy. For example, combining PARP inhibitors with RAD52 inhibition may target both HR-deficient and HR-proficient tumors [17] [31]. In CRISPR gene editing, combined inhibition of NHEJ, MMEJ, and SSA significantly improves precise HDR efficiency [17].

MMEJ and SSA represent distinct, mechanistically defined pathways that significantly expand our understanding of DSB repair beyond the classical NHEJ-HDR dichotomy. While traditionally viewed as backup pathways, they play active roles in normal physiology and disease states, particularly cancer. Their mutagenic nature contributes to genomic instability and oncogenesis, while also creating therapeutic vulnerabilities through synthetic lethal interactions.

The growing toolkit of pathway-specific inhibitors and sophisticated genomic assays continues to reveal complex interpathway regulation and context-dependent pathway engagement. Future research will undoubtedly refine our understanding of these pathways in development, aging, and disease, while paving the way for increasingly precise therapeutic interventions that exploit the unique genetic dependencies of cancer cells.

Strategic Implementation: Choosing and Applying NHEJ or HDR for Your Research Goals

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic research, enabling precise modifications to the DNA of various organisms. At the core of this technology lies the cell's innate DNA repair machinery, which is activated in response to CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs). Two primary repair pathways compete to resolve these breaks: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) [32] [3]. While HDR enables precise, template-driven edits, NHEJ operates as an efficient but error-prone mechanism that directly ligates broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [3]. This inherent characteristic of NHEJ—often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels)—makes it particularly suitable for gene knockout strategies where the goal is to disrupt gene function [3]. Understanding when and how to leverage NHEJ is crucial for researchers designing effective gene disruption experiments, especially within the broader context of comparing NHEJ and HDR applications across different research objectives.

The Biological Basis of NHEJ

The NHEJ Mechanism

The NHEJ pathway initiates when the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recognizes and binds to broken DNA ends, forming a ring-like structure that encircles the DNA [32]. This complex then recruits and activates downstream repair factors. The primary sub-pathway for repairing CRISPR-Cas9-induced blunt-ended DSBs involves the Ku-XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex, which catalyzes the direct re-ligation of the DNA ends [32]. Alternative sub-pathways may engage nucleases like Artemis to process damaged ends or polymerases such as Pol μ and Pol λ to fill in small gaps before ligation [32]. Unlike HDR, which is restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, NHEJ is active throughout all cellular phases, contributing to its status as the dominant DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells [33] [32].

NHEJ Repair Outcomes

Contrary to the traditional view of NHEJ as exclusively error-prone, emerging evidence suggests a surprising degree of precision in its repair. Studies indicate that accurate NHEJ accounts for approximately 50% of repair events when two adjacent DSBs are induced by paired Cas9-gRNAs [34]. However, the repair is often characterized by small, stochastic insertions or deletions (indels) [3] [35]. When a single DSB is introduced within a coding exon, these indels can disrupt the reading frame, leading to premature stop codons and effective gene knockout [3]. The specific indel signature can vary based on cellular context; for instance, cells deficient in core NHEJ components (e.g., LIG4, XRCC4) may still achieve efficient mutagenic repair through alternative pathways like POLQ-dependent alternative end joining (alt-EJ), which typically generates larger deletions [35].

When to Choose NHEJ Over HDR: A Strategic Framework

Comparative Advantages of NHEJ and HDR

The decision to utilize NHEJ or HDR hinges on the experimental goal. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each pathway to guide this decision.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of NHEJ and HDR for Genome Editing

| Feature | NHEJ Pathway | HDR Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No | Yes (donor DNA with homology arms) |

| Primary Application | Gene knockout, gene disruption | Precise knock-in, point mutations, tag insertion |

| Editing Efficiency | High (dominant pathway) | Low (typically 0.5-20% in mammalian cells) [33] |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | Active throughout all phases | Restricted to S and G2 phases [33] |

| Repair Outcome | Error-prone (indels) or accurate ligation [34] | Precise, using homologous template |

| Key Inhibitors | Scr7 (targets DNA Ligase IV) [33], Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 [17] | - |

| Ideal Use Cases | Loss-of-function studies, functional genomics screens | Disease modeling, gene correction, protein tagging |

Specific Applications for NHEJ

- Gene Knockout Studies: NHEJ is the preferred mechanism for generating gene knockouts, as the introduction of indels into coding exons effectively disrupts the open reading frame, leading to loss of gene function [3].