Harnessing Electromagnetic-Thermodynamic Material Behaviors for Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in understanding and applying the coupled electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors of materials for biomedical innovation.

Harnessing Electromagnetic-Thermodynamic Material Behaviors for Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in understanding and applying the coupled electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors of materials for biomedical innovation. It explores foundational principles of multiferroic, magnetic, and magnetoelectric materials, detailing synthesis and characterization methodologies for applications in targeted drug delivery, tissue engineering, and cancer therapy. The content addresses key challenges in biocompatibility, optimization, and scale-up, while providing comparative analyses of material performance and validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging these smart materials to develop next-generation diagnostic and therapeutic platforms.

Fundamental Principles of Coupled Behaviors in Smart Materials

Multiferroic materials, which simultaneously possess two or more ferroic order parameters, and magnetoelectrics, which exhibit coupling between magnetic and electric fields, have emerged as a transformative class of materials in condensed matter physics and materials science. This in-depth technical guide examines the fundamental principles, material systems, characterization methodologies, and underlying thermodynamics governing these advanced materials. Framed within the broader context of electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors in materials research, this review synthesizes current understanding of magnetoelectric coupling mechanisms, advanced fabrication techniques for thin films and nanostructures, and characterization protocols. Target toward researchers, scientists, and materials development professionals, this work also explores emerging applications and future research directions that leverage the unique functionalities of magnetoelectric multiferroics, particularly the compelling prospect of electrical control over ferromagnetism at room temperature.

Multiferroic materials are defined by the simultaneous presence of two or more primary ferroic properties—ferroelectricity, ferromagnetism, or ferroelasticity—within a single phase [1]. The magnetoelectric (ME) effect describes the phenomenon where an applied electric field induces a magnetization in the material, or conversely, an applied magnetic field induces an electric polarization [2]. This cross-coupling between magnetic and electrical order parameters enables novel functionalities that cannot be achieved in single-order-parameter materials, with particular interest in low-power electronic devices, advanced sensors, and next-generation memory technology.

The distinction between multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials is fundamental yet often misunderstood. A material can be multiferroic without being magnetoelectric if its ferroic orders do not couple to one another. Conversely, a magnetoelectric material may not be multiferroic if it exhibits coupling between magnetic and electric fields without possessing multiple ferroic order parameters [1]. This nuanced relationship underscores the complexity of these material systems and the importance of precise classification in research and development. The revival of interest in these materials over the past two decades has been driven largely by the technological goal of achieving electrical control of ferromagnetism at room temperature, which would enable transformative advances in spintronics, memory devices, and sensors [3] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Classifications

Order Parameters and Coupling Mechanisms

The fundamental physics of multiferroics and magnetoelectrics centers on the interplay between order parameters and the mechanisms that enable their coupling:

- Ferroelectric Order: Characterized by a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by an applied electric field, typically arising from off-center structural distortions leading to ionic displacement.

- Ferromagnetic Order: Defined by spontaneous magnetization that can be reoriented by applied magnetic fields, resulting from the parallel alignment of electron spins.

- Ferroelastic Order: Manifested by a spontaneous strain that can be reoriented by applied stress.

Magnetoelectric coupling emerges from various microscopic mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized as either intrinsic (single-phase) or extrinsic (composite) [2]. Intrinsic magnetoelectricity occurs in single-phase materials where the coupling is mediated through specific physical mechanisms, while extrinsic magnetoelectricity arises in composite materials where the coupling results from product-property interactions between piezoelectric and magnetostrictive phases.

Table 1: Classification of Magnetoelectric Coupling Mechanisms

| Category | Coupling Mechanism | Representative Materials | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic (Single-Phase) | Spin-driven ferroelectricity | TbMnO₃, TbMn₂O₅ | Magnetic ordering breaks spatial inversion symmetry, inducing polarization |

| Charge ordering | LuFe₂O₄ | Frustrated charge configurations create polar patterns [2] | |

| Geometric ferroelectricity | Hexagonal RMnO₃ (R=Y, Ho-Lu) | Non-centrosymmetric crystal structure enables ferroelectricity independent of magnetism | |

| Hybrid Improper Ferroelectricity | (Ca,Sr)₃Ti₂O₇ | Combination of non-polar rotational modes produces polarization [2] | |

| Extrinsic (Composite) | Product-property | BaTiO₃-CoFe₂O₄ nanocomposites | Strain-mediated coupling between piezoelectric and magnetostrictive phases [2] |

| Exchange bias | Ferromagnetic/Ferroelectric heterostructures | Interface-driven coupling effects |

Thermodynamic Framework

The thermodynamics of multiferroic systems provides a unified framework for understanding multicaloric effects—the thermal response to applied electric and magnetic fields. The general thermodynamic potential for a magnetoelectric multiferroic can be expressed as:

Φ = Φ₀ + αP² + βM² + γ₁P⁴ + γ₂M⁴ + δP²M² - E·P - H·M

where P is the polarization, M is the magnetization, E is the electric field, H is the magnetic field, α and β are harmonic coefficients, γ₁ and γ₂ are anharmonic coefficients, and δ represents the magnetoelectric coupling coefficient [4].

This Landau-type expansion captures the essential physics of coupled order parameters, with the magnetoelectric coupling term (δP²M²) enabling the cross-control of magnetic properties by electric fields and vice versa. The multicaloric effect in such systems comprises contributions from caloric effects associated with each ferroic property plus a cross-contribution arising from their interplay [4]. This framework has been successfully applied to diverse multiferroic classes, including metamagnetic shape-memory alloys and ferrotoroidic materials.

Material Systems and Synthesis Methods

Single-Phase Multiferroics

Single-phase multiferroics represent the fundamental pursuit of intrinsic magnetoelectric coupling, though their realization is challenged by competing electronic requirements for ferroelectricity (typically requiring empty d-orbitals) and ferromagnetism (typically requiring partially filled d-orbitals) [2]. Several material families have emerged as important single-phase systems:

- BiFeO₃: Perhaps the most studied single-phase multiferroic, exhibiting both ferroelectricity (TC ≈ 1100K) and antiferromagnetism (TN ≈ 640K) at room temperature. Its ferroelectricity originates from the stereochemical activity of Bi³⁺ 6s² lone pairs, while magnetism arises from Fe³⁺ cations.

- Hexagonal Manganites (h-RMnO₃, where R=Y, Ho-Lu): These materials display geometric ferroelectricity resulting from tilting of MnO₅ polyhedra and trimerization of rare-earth ions, coupled with antiferromagnetic ordering.

- Spin-induced Multiferroics (TbMnO₃, MnWO₄): In these materials, magnetic spiral structures break spatial inversion symmetry, inducing ferroelectric polarization through inverse Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction.

- Hybrid Improper Ferroelectrics: Materials such as (Ca,Sr)₃Ti₂O₇ achieve ferroelectricity through a combination of two non-polar rotational modes, providing a general design strategy for creating new multiferroics [2].

Composite Magnetoelectrics

Composite magnetoelectrics circumvent the inherent limitations of single-phase materials by combining separate piezoelectric and magnetostrictive phases that interact through strain mediation:

- Horizontal Multilayers: Thin-film heterostructures with alternating piezoelectric (e.g., BaTiO₃, PZT) and magnetostrictive (e.g., CoFe₂O₄, Terfenol-D) layers that couple through interface strain.

- Vertical Nanostructures: Self-assembled nanostructures such as CoFe₂O₄ pillars in BaTiO₃ matrix, where the large surface-to-volume ratio enhances strain transfer [3] [2].

- Polymer-Based Composites: Flexible magnetoelectric composites incorporating piezoelectric polymers (PVDF) with magnetostrictive particles, enabling applications in flexible electronics [5].

- Functionally Graded Composites: Recently developed materials with spatially varying composition to enhance magnetoelectric response across specific temperature ranges [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Multiferroic and Magnetoelectric Material Systems

| Material System | Type | Ferroelectric T_C | Magnetic TN/TC | ME Coupling Coefficient | Room Temperature Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiFeO₃ | Single-phase | ~1100 K | ~640 K (T_N) | Weak intrinsic | Yes |

| BaTiO₃-CoFe₂O₄ | Composite | ~400 K (BaTiO₃) | ~790 K (CoFe₂O₄) | High extrinsic (~1 V/cm·Oe) | Yes [2] |

| TbMnO₃ | Single-phase | ~28 K | ~41 K (T_N) | Strong intrinsic | No |

| Pb(Zr,Ti)O₃-Terfenol-D | Composite | ~650 K (PZT) | ~380 K (Terfenol-D) | Very high extrinsic (>10 V/cm·Oe) | Yes |

| h-YMnO₃ | Single-phase | ~1270 K | ~70-130 K (T_N) | Weak intrinsic | Partial (FE only at RT) |

Synthesis and Fabrication Protocols

The synthesis of high-quality thin films and nanostructures has been instrumental in advancing multiferroics research [3]. Key fabrication methodologies include:

Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD) for Complex Oxide Thin Films

Objective: Epitaxial growth of high-quality multiferroic oxide thin films (e.g., BiFeO₃, BaTiO₃) with controlled stoichiometry and crystallographic orientation.

Protocol:

- Target Preparation: Synthesize ceramic target of desired composition through solid-state reaction of precursor oxides with appropriate stoichiometry.

- Substrate Preparation: Select appropriate single-crystal substrates (e.g., SrTiO₃, MgO, LSAT) with suitable lattice matching. Prepare substrate surface through ultrasonic cleaning in organic solvents and thermal annealing in oxygen atmosphere.

- Deposition Parameters: Set substrate temperature to 600-800°C; maintain oxygen pressure of 100-300 mTorr; utilize KrF excimer laser (λ=248 nm) with energy density of 1-2 J/cm² and repetition rate of 1-10 Hz.

- Post-deposition Annealing: Anneal films in oxygen atmosphere at 400-600°C for 30-60 minutes to optimize oxygen stoichiometry and reduce point defects.

This approach has enabled the creation of atomically engineered ferroic layers that function as room-temperature magnetoelectric multiferroics [2].

Self-Assembly of Nanocomposite Structures

Objective: Fabricate vertical heterostructures with magnetostrictive nanopillars embedded in piezoelectric matrix.

Protocol:

- Target Design: Prepare composite targets with appropriate phase ratio or utilize sequential deposition through masked approaches.

- Immiscible System Selection: Identify material pairs with limited solid solubility (e.g., CoFe₂O₄-BaTiO₃) to enable phase separation during growth.

- Epitaxial Stabilization: Optimize deposition temperature (typically 650-800°C) to promote simultaneous crystallization of both phases while maintaining vertical alignment.

- Morphology Control: Regulate pillar size and spacing through manipulation of deposition rate (0.1-1 Å/s) and substrate orientation.

Such nanopatterned hybrid materials have demonstrated room-temperature magnetic switching of electric polarization [2].

Characterization Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Structural and Microstructural Characterization

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and Reciprocal Space Mapping (RSM)

Purpose: Determine crystal structure, phase purity, epitaxial relationships, and strain states in multiferroic thin films and heterostructures.

Experimental Protocol:

- Utilize high-resolution X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation source (λ=1.5406 Å).

- Perform θ-2θ scans to identify phase composition and out-of-plane lattice parameters.

- Conduct ω-scans (rocking curves) to assess crystalline quality and mosaic spread.

- Perform φ-scans to determine in-plane orientation relationships between film and substrate.

- Collect reciprocal space maps around asymmetric reflections to quantify strain states and relaxation mechanisms.

Expected Outcomes: For high-quality epitaxial BiFeO₃ films on SrTiO₃(001), (00l) reflections should appear without secondary phases, rocking curve FWHM values typically <0.1°, and RSM should demonstrate coherent or partially relaxed strain states.

Ferroelectric and Dielectric Characterization

Polarization-Electric Field (P-E) Hysteresis Measurements

Purpose: Quantify ferroelectric properties including spontaneous polarization, coercive field, and switching characteristics.

Experimental Protocol:

- Electrode Fabrication: Deposit top electrodes (Pt, Au) through sputtering or electron-beam evaporation with shadow masks (100-500 μm diameter).

- Measurement Setup: Utilize standardized ferroelectric test system (e.g., Radiant Technologies, AixACCT) with virtual ground circuit.

- Measurement Parameters: Apply triangular voltage waveforms at frequencies of 100 Hz-10 kHz with amplitudes sufficient to observe saturation polarization.

- Temperature Dependence: Conduct measurements across temperature range (80-700 K) using temperature-controlled stage to assess phase transitions.

Data Interpretation: For BiFeO₃ thin films, typical room-temperature values include remanent polarization (Pr) of 60-100 μC/cm² and coercive field (Ec) of 100-300 kV/cm.

Magnetic and Magnetoelectric Characterization

SQUID Magnetometry

Purpose: Measure magnetic moment as a function of applied field, temperature, and orientation to determine magnetic ordering temperatures, susceptibility, and anisotropy.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Mounting: Secure sample using non-magnetic holder (quartz, plastic straw) with specific orientation relative to applied field.

- Zero-Field Cooling/Field Cooling: Collect M(T) data under ZFC and FC conditions (typically 5-1000 Oe) to identify magnetic transitions and irreversibility.

- Hysteresis Loops: Measure M(H) at relevant temperatures with fields up to ±7 T to determine saturation magnetization, coercivity, and remanence.

Magnetoelectric Coupling Coefficient Measurement

Purpose: Directly quantify the magnetoelectric response by measuring induced polarization under applied AC magnetic field or induced magnetization under applied AC electric field.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Polish and electrode sample appropriately for electrical measurements; ensure uniform magnetic field exposure.

- Setup Configuration: Place sample between Helmholtz coils for AC magnetic field application (frequency typically 1-10 kHz); simultaneously shield from electromagnetic interference.

- Lock-in Detection: Measure induced voltage at the frequency of the applied AC magnetic field using lock-in amplifier referenced to the field frequency.

- DC Bias Superposition: Apply DC magnetic bias field (0-1 T) while measuring AC magnetoelectric response to determine field dependence.

The magnetoelectric coefficient is calculated as αME = δE/δH = Vout/(t·f·HAC), where Vout is the measured voltage, t is sample thickness, f is frequency, and H_AC is the applied AC magnetic field amplitude.

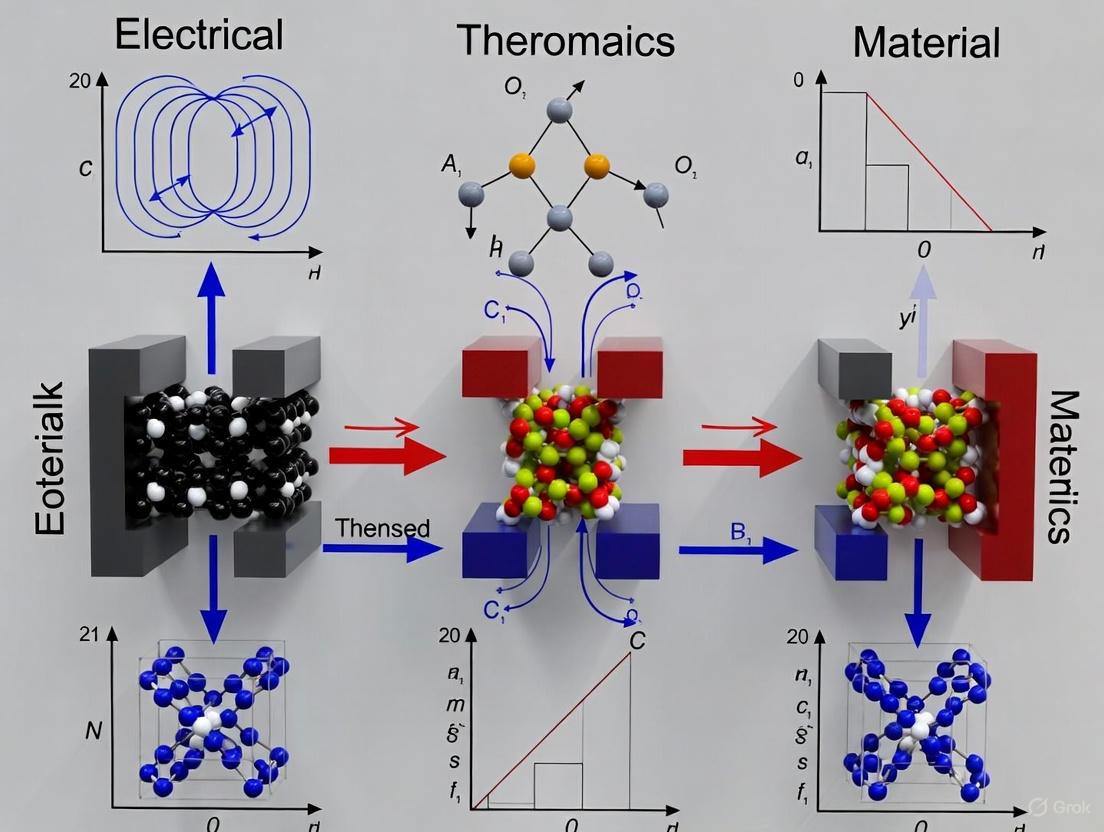

Visualization of Magnetoelectric Coupling and Material Design

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts and relationships in multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials.

Magnetoelectric Coupling Mechanisms

Multiferroic Materials Classification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Multiferroics Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Ferrite (BiFeO₃) | Single-phase multiferroic model system | Room-temperature multiferroic; Rhombohedral perovskite; G-type antiferromagnet | Epitaxial thin films; Polycrystalline ceramics; Nanostructures |

| Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃) | Piezoelectric matrix in composites | Ferroelectric T_C ≈ 400K; Large piezoelectric coefficient | BaTiO₃-CoFe₂O₄ nanocomposites; Multilayer heterostructures |

| Cobalt Ferrite (CoFe₂O₄) | Magnetostrictive phase in composites | Inverse spinel structure; Large magnetostriction; High coercivity | Embedded nanopillars in BaTiO₃; Core-shell nanoparticles |

| Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT) | High-performance piezoelectric | Large piezoelectric coefficients; Morphotropic phase boundary composition | PZT-Terfenol-D composites; Thin film heterostructures |

| Terfenol-D (TbₓDy₁₋ₓFe₂) | High-magnetostriction alloy | Giant magnetostriction (λ_s > 1000 ppm) at room temperature | Laminated composites; Polymer-matrix composites |

| Strontium Titanate (SrTiO₃) | Single-crystal substrate | Perovskite structure; Lattice matching for epitaxial growth | (001), (110), (111) orientations; Nb-doped conducting substrates |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | Polymer piezoelectric matrix | Flexible; Solution processable; Moderate piezoelectric response | Magnetoelectric polymer composites; Flexible devices |

Applications and Future Perspectives

The unique properties of multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials enable diverse technological applications:

- Low-Power Memory Devices: Magnetoelectric random access memory (MeRAM) utilizes voltage-controlled magnetic switching to overcome scaling limitations of conventional MRAM, potentially reducing writing energy by orders of magnitude [2].

- Magnetic Field Sensors: Magnetoelectric composites can detect small AC and DC magnetic fields with high sensitivity, applicable in biomedical imaging, navigation, and security systems.

- Energy Harvesting: Multiferroic composites can scavenge ambient electromagnetic energy, converting it to usable electrical power through magnetoelectric transduction.

- Spintronic Devices: Electric field control of magnetic domains enables energy-efficient spintronic logic devices and race-track memories.

- Tunable Microwave Electronics: The electric field control of magnetic permeability in multiferroic heterostructures allows for voltage-tunable inductors, filters, and phase shifters.

Future research directions focus on overcoming current limitations, particularly the enhancement of magnetoelectric coupling at room temperature, development of lead-free environmentally friendly alternatives, and improved understanding of interface coupling mechanisms [5] [2]. The integration of multiferroics with semiconductor technology and the exploration of topological structures such as skyrmions and polar vortices represent particularly promising avenues for both fundamental research and technological innovation [2].

This technical guide has comprehensively examined the fundamental principles, material systems, characterization methodologies, and applications of multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Situated within the broader context of electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors in materials research, these systems offer exceptional opportunities for scientific discovery and technological innovation. The continued advancement of this field requires interdisciplinary collaboration across materials synthesis, theoretical modeling, device engineering, and characterization science. As research progresses toward stronger magnetoelectric coupling at practical temperatures and the development of scalable fabrication processes, multiferroics are poised to enable transformative technologies that leverage the exquisite control of magnetic properties by electric fields and vice versa, potentially revolutionizing information storage, sensing, and energy conversion technologies.

Magnetic nanomaterials represent a cornerstone of modern materials science, distinguished from their bulk counterparts by their unique electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors at the nanoscale. These materials, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers, exhibit novel properties such as enhanced magnetism, superparamagnetism, and high surface-area-to-volume ratios, which are governed by quantum mechanical effects and finite-size phenomena [6] [7]. Their ability to respond to external magnetic fields enables precise control for targeted applications, bridging fundamental research with technological innovation across disciplines from biomedicine to energy and electronics. The classification of these nanomaterials is essential for understanding their structure-property relationships and tailoring them for specific functions, particularly in the context of their electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic interactions.

This review provides a systematic classification of magnetic nanomaterials, categorizing them into pure metals, metal oxides, and multicomponent systems. It examines their inherent magnetic characteristics, synthesis methodologies, and functional behaviors, framed within a broader thesis on the interplay between electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic properties in advanced materials research. Special emphasis is placed on their emerging applications in drug delivery, hyperthermia therapy, and diagnostic imaging, highlighting their transformative potential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Classification and Properties of Magnetic Nanomaterials

Magnetic nanomaterials are broadly classified based on their chemical composition and structural configuration. The primary categories include magnetic pure metals, magnetic metal oxides (including ferrites), and multicomponent magnetic nanoparticles such as core/shell structures or nanoclusters [6]. Each category possesses distinct magnetic behaviors, thermodynamic stability, and electrical transport properties, making them suitable for specific applications.

Table 1: Classification and Key Properties of Magnetic Nanomaterials

| Category | Examples | Key Magnetic Properties | Electrical & Thermodynamic Behaviors | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Metals | Fe, Co, Ni | Ferromagnetic, high saturation magnetization, large magnetic moment [6]. | High electrical conductivity; susceptible to oxidation, leading to thermodynamic instability; requires protective coatings [6]. | Magnetic separation, data storage [6]. |

| Metal Oxides | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄), Maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃) | Ferrimagnetic, often superparamagnetic at nanoscale [6] [7]. | Semi-conducting or insulating; inherent thermodynamic stability and biocompatibility [6] [7]. | Biomedicine (MRI, drug delivery, hyperthermia), biosensing [6] [7]. |

| Ferrites | MeFe₂O₄ (Me = Mn, Co, Zn) | Tunable magnetic anisotropy and coercivity based on the metal cation 'Me' [6]. | Variable electrical resistivity; thermodynamic properties can be engineered via composition [6]. | Hyperthermia agents, magnetic cores in electronics [6]. |

| Multicomponent/ Core-Shell | FePt@Fe₃O₄, Co@SiO₂ | Combined magnetic properties (e.g., high magnetization core with protective shell) [6]. | Shell material (e.g., silica, gold) modulates electrical interface and enhances thermodynamic (colloidal) stability in biological environments [6] [7]. | Theranostics, targeted drug delivery, catalysis [6] [7]. |

Magnetic Pure Metals

Nanoparticles of pure magnetic metals such as iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni) are characterized by their high saturation magnetization and strong magnetic moments, which are advantageous for applications requiring intense magnetic responses [6]. From a thermodynamic perspective, these metallic systems are highly susceptible to oxidation in air, which can degrade their magnetic performance and limit their utility. This instability necessitates the development of homogeneous, uniform coatings to protect the metallic core from its environment [6]. For instance, iron nanoparticles can be synthesized via the reduction of iron salts in aqueous solutions using sodium borohydride, but the process requires rigorous control over surface passivation to prevent combustion [6].

Magnetic Metal Oxides

Iron oxide nanoparticles, particularly magnetite (Fe₃O₄) and maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃), are among the most extensively studied magnetic metal oxides due to their favorable biocompatibility, thermodynamic stability, and robust magnetic properties [6] [7]. These materials often exhibit superparamagnetism—a phenomenon where nanoparticles do not retain magnetization in the absence of an external magnetic field, thus avoiding aggregation and enabling their use in biomedical applications like in vivo drug delivery [7]. Their electrical behavior ranges from semiconducting to insulating, which minimizes eddy current losses in alternating fields, a critical factor for hyperthermia therapy. Synthesis methods such as co-precipitation are simple and cost-effective, though they may result in polydisperse particles requiring post-synthesis modifications for improved stability [6] [7].

Multicomponent Magnetic Nanoparticles

Multicomponent nanoparticles, including core/shell structures and magnetic nanoclusters, are engineered to combine the advantageous properties of different materials while mitigating their individual limitations [6]. A common configuration involves a magnetic pure metal or metal oxide core encapsulated within a biocompatible shell, such as silica, gold, or polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) [7]. This architecture enhances the thermodynamic (colloidal) stability of the nanoparticles in physiological environments, reduces immune recognition, and provides a versatile surface for functionalization with drugs, targeting ligands, or diagnostic agents [6] [7]. The core dictates the magnetic response, while the shell governs the electrical interface and biological interactions, making these systems particularly powerful for theranostic applications that integrate therapy and diagnosis [7].

Synthesis Methods and Experimental Protocols

The synthesis of magnetic nanomaterials is critical for controlling their size, shape, crystallinity, and ultimately, their magnetic, electrical, and thermodynamic properties. The methods can be broadly categorized into chemical, physical, and biological approaches [7].

Chemical Synthesis Methods

Chemical methods are the most prevalent for producing monodisperse, high-purity nanoparticles with tailored surface characteristics.

- Co-precipitation: This is a simple and cost-effective method involving the simultaneous precipitation of ferrous (Fe²⁺) and ferric (Fe³⁺) ions from an aqueous salt solution in an alkaline medium to form iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄ or γ-Fe₂O₃) [7]. The protocol requires strict control over pH, ionic strength, and temperature to achieve desired size and magnetic properties. A typical protocol involves dissolving FeCl₃·6H₂O and FeCl₂·4H₂O in deoxygenated water at a molar ratio of 2:1, followed by the dropwise addition of a base like NH₄OH under inert atmosphere and vigorous stirring. The resulting black precipitate is then isolated by magnetic separation and washed thoroughly [7].

- Thermal Decomposition: This method produces highly crystalline, monodisperse nanoparticles by decomposing organometallic precursors (e.g., iron pentacarbonyl, Fe(CO)₅) in high-boiling organic solvents containing stabilizing surfactants (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) [6] [7]. A standard protocol involves heating the precursor solution to 250-300°C under a nitrogen atmosphere for several hours. This allows for precise control over size and shape, but the resulting hydrophobic nanoparticles often require a subsequent ligand exchange phase for biocompatibility [7].

- Sol-Gel Method: This process involves the hydrolysis and condensation of metal precursors (e.g., metal alkoxides) to form an inorganic network, often used for coating magnetic cores with silica or other oxides [7]. For instance, to create a silica shell (Fe₃O₄@SiO₂), magnetic nanoparticles are dispersed in a mixture of ethanol, water, and ammonia, followed by the dropwise addition of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS). The reaction proceeds for several hours, resulting in a core/shell structure that improves stability and provides a surface for further chemistry [7].

Physical and Biological Synthesis Methods

- Physical Methods: Techniques like laser ablation utilize a high-energy laser beam to vaporize a metal target submerged in a liquid medium, producing pure, contaminant-free nanoparticles [7]. Ball milling is a mechanical, top-down approach that grinds bulk magnetic materials into nanosized powders, though it often results in broad size distributions and irregular shapes [7].

- Biological Methods: These eco-friendly approaches use microorganisms (e.g., Magneto spirillum species producing magnetosomes) or plant extracts containing bioactive compounds as reducing and stabilizing agents to form biocompatible nanoparticles [7].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Synthesis and Functionalization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Protocol/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ferric/Ferrous Chlorides (FeCl₃, FeCl₂) | Iron precursors for co-precipitation synthesis of iron oxides [7]. | Used in a 2:1 molar ratio in aqueous solution under inert atmosphere [7]. |

| Oleic Acid & Oleylamine | Surfactants in thermal decomposition to control growth and prevent aggregation [7]. | Dissolved in high-boiling solvents (e.g., octadecene) with organometallic precursors [7]. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for silica coating via the sol-gel process [7]. | Hydrolyzes to form a uniform SiO₂ shell around the magnetic core, enhancing stability [7]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Biocompatible polymer for surface functionalization to improve stealth and circulation time in vivo [7]. | Conjugated to the nanoparticle surface via covalent bonding to amine or carboxyl groups [7]. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH) | Base to initiate precipitation in co-precipitation methods [7]. | Rapid addition under vigorous stirring is crucial for uniform nucleation [7]. |

| Dextran | Natural polymer for coating, enhancing colloidal stability and biocompatibility in biomedical applications [7]. | Often added during or immediately after the co-precipitation reaction [7]. |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for synthesizing and functionalizing magnetic nanomaterials, showing the main chemical, physical, and biological synthesis pathways leading to surface functionalization and final application.

Advanced Characterization and Interplay of Properties

Understanding the electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic coupling in magnetic nanomaterials is paramount for predicting their performance in practical applications. Advanced characterization techniques are employed to probe these interconnected properties.

Magnetic and Electrical Characterization

The magnetic properties of nanomaterials, including saturation magnetization, coercivity, and remanence, are typically measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) or a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer [6] [7]. For electrical characterization, impedance spectroscopy is used to measure the complex impedance (resistance and reactance) of materials, which is crucial for understanding their behavior in electronic circuits and under AC fields, such as in hyperthermia applications [8]. A key consideration in such measurements is the effect of Joule heating, where an alternating current (AC) passing through a material causes temperature fluctuations due to electrical resistance. This time-varying heating can lead to non-linear electrical responses and apparent inductance, which must be accounted for to avoid misinterpretation of a material's intrinsic magnetic behavior [8].

Thermodynamic and Magneto-Plastic Coupling

At the nanoscale, the thermodynamic stability of a system is significantly influenced by its surface energy and external fields. Furthermore, in ferromagnetic materials, a strong coupling often exists between magnetic states and mechanical deformation, known as magneto-plastic coupling [9]. Energy-based thermodynamic models have been developed to describe this phenomenon, where the magnetic anisotropy induced by mechanical rolling processes affects both the magnetic and elastic response of the material [9] [10]. This coupling is critical for applications in electrical steel sheets used in motors and transformers, where rotational magnetization and magnetostriction impact energy efficiency and core losses [10].

Applications in Biomedicine and Electronics

The unique properties of magnetic nanomaterials have led to their deployment in a wide array of advanced applications, particularly in biomedicine and electronics.

Biomedical Applications

In biomedicine, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) are the most widely used due to their biocompatibility and responsiveness to external magnetic fields [7]. Their applications are multifaceted:

- Targeted Drug Delivery: MNPs can be functionalized with therapeutic agents and guided to a specific site, such as a tumor, using an external magnetic field. This enhances drug concentration at the target site while minimizing systemic side effects [6] [7].

- Hyperthermia Therapy: When subjected to an alternating magnetic field, MNPs dissipate heat. This property is exploited to thermally ablate malignant cells by raising the temperature of the tumor environment to 41–46°C [7].

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): SPIONs act as excellent contrast agents in MRI, shortening the transverse relaxation time (T2) of surrounding water protons and producing darker images that improve diagnostic accuracy [7].

- Theranostics: MNPs serve as platforms that combine diagnostic capabilities (e.g., MRI contrast) with therapeutic functions (e.g., drug delivery or hyperthermia) in a single system, enabling personalized medicine approaches [7].

Electronic and Spintronic Applications

Beyond biomedicine, magnetic nanomaterials are pivotal in the development of next-generation electronics. Perovskite materials with the ABX₃ structure (e.g., manganites) exhibit remarkable properties like colossal magnetoresistance (CMR) and multiferroicity, where ferroelectric and magnetic orders coexist [11]. These materials are central to spintronics, a field that utilizes the spin of electrons, in addition to their charge, for information processing [11] [12]. Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated that magnetic waves, known as magnons, in antiferromagnetic materials can generate measurable electric signals [12]. This discovery, which bridges magnetism and electricity without the flow of electrical current, paves the way for computer chips that operate at terahertz frequencies with drastically lower power consumption [12].

Figure 2: Logical relationship between the inherent magnetic properties of nanomaterials, the functions they enable, and their resulting high-impact applications in biomedicine and electronics.

The systematic classification of magnetic nanomaterials from pure metals to complex oxides provides a foundational framework for understanding their electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors. This review has delineated how composition, structure, and synthesis protocol dictate these properties and, consequently, the functional application of the materials. While significant progress has been made, challenges remain in the large-scale, reproducible synthesis of monodisperse nanoparticles, the precise control over their surface chemistry, and a comprehensive understanding of their long-term fate in biological and environmental systems. Future research directions will likely focus on the development of more sophisticated multicomponent nanostructures, the exploration of novel magnetic phenomena such as altermagnetism [13], and the deepening of our knowledge regarding magneto-thermal and magneto-electric couplings at the nanoscale. Overcoming these hurdles will be essential to fully unlock the potential of magnetic nanomaterials in revolutionizing fields from personalized medicine to energy-efficient computing.

Thermodynamic Phase Transitions in Magnetic Spin Textures and Their Dynamics

The study of thermodynamic phase transitions in magnetic spin textures represents a frontier in condensed matter physics, bridging the electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors of advanced materials. Magnetic metamaterials—artificially engineered systems with tailored magnetic properties—enable the exploration of fundamental physics often inaccessible in naturally occurring crystals [14]. These systems display rich collective phenomena including highly frustrated states, topological protections, and complex phase diagrams governed by competing interactions. Understanding the thermodynamic properties of these magnetic textures is paramount for advancing future technologies in spintronics, quantum computing, and energy-efficient electronics [15] [16].

This technical overview examines thermodynamic phase transitions across diverse magnetic systems, focusing on experimental methodologies for detecting and characterizing these transitions, the underlying theoretical frameworks explaining observed behaviors, and potential applications leveraging these phenomena. The convergence of nanofabrication capabilities, advanced measurement techniques, and theoretical modeling has created a fertile ground for exploring and manipulating magnetic phase transitions in artificial spin systems.

Theoretical Foundations of Magnetic Phase Transitions

Magnetic phase transitions occur when a magnetic system undergoes a qualitative change in its spin configuration in response to varying external parameters such as temperature, magnetic field, or pressure. In frustrated magnetic systems, competing interactions prevent simultaneous minimization of all interaction energies, leading to massive degeneracy and often unexpected emergent behaviors.

Frustration and Degeneracy in Artificial Spin Systems

Artificial kagome spin ice exemplifies frustrated magnetism in engineered systems. This two-dimensional system consists of elongated single-domain nanomagnets arranged on a kagome lattice and coupled via dipolar interactions [14]. Each nanomagnet acts as a macroscopic Ising spin, aligned along its long axis. The geometry prevents simultaneous satisfaction of all interactions, creating a highly frustrated system with a vast number of quasi-degenerate states—the spin ice manifold.

Theoretical work predicts that upon cooling, such systems undergo consecutive phase transitions where long-range dipolar interactions progressively lift the degeneracy of the spin ice manifold [14]. The predicted sequence includes: a high-temperature disordered spin ice phase (Ice I) with only local vertex constraints; an intermediate charge-ordered phase (Ice II); and finally a long-range charge- and spin-ordered phase (LRO) at the lowest temperatures.

Topological Transitions and Skyrmion Formation

Beyond conventional magnetic ordering, certain systems host topological transitions characterized by the emergence of protected spin textures. In Fe/Gd multilayers, competition among dipolar interactions, perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, and exchange interactions leads to the formation of topologically non-trivial structures including bubbles and skyrmions [16]. Unlike in many skyrmion-host materials, this stabilization occurs without significant Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction, highlighting an alternative pathway for topological texture formation.

The phase behavior in such systems exhibits path dependence, where the specific sequence of applied fields and temperatures influences the final magnetic state [16]. This hysteresis and metastability reflect the complex energy landscape with multiple local minima separated by activation barriers.

Experimental Systems and Observed Phase Transitions

Artificial Kagome Spin Ice

Table 1: Phase Transitions in Artificial Kagome Spin Ice [14]

| Phase Name | Temperature Range | Magnetic Characteristics | Transition Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ice I (Disordered) | Highest temperatures | Highly degenerate spin ice manifold with local vertex rules | Crossover from paramagnetic regime |

| Ice II (Charge-ordered) | Intermediate temperatures | Partial lifting of degeneracy with charge order | Second-order phase transition |

| LRO (Long-range ordered) | Lowest temperatures | Full long-range charge and spin order | Second-order phase transition |

Experimental realization of artificial kagome spin ice employed nanomagnets of length 63 nm, width 26 nm, and thickness 6 nm, fabricated over large areas (nine 5×5 mm² arrays) to ensure thermodynamic behavior [14]. By varying inter-magnet separation (170 nm for strong coupling, 400 nm for weak coupling), researchers tuned interaction strengths and corresponding transition temperatures.

Muon spin relaxation (μSR) measurements revealed critical temperatures through peaks in the longitudinal relaxation rate (λL) at 35 K and 145 K for the strongly interacting sample, indicating two second-order phase transitions within the spin ice manifold [14]. The transverse relaxation rate (λT) showed changing slopes across these transitions, further confirming the different correlated states.

Van der Waals Magnetic Semiconductor CrSBr

Table 2: Magnetic Properties of CrSBr Thin Layers [15]

| Property | Observation | Measurement Technique | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic transitions | Antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic transitions at specific temperatures | Tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) | Reveals complex magnetic structure responsive to temperature and field |

| Layer-dependent behavior | Unique spin-flip processes in 4-layer vs. 5-layer devices | Vertical tunneling device configuration | Enables property tuning via thickness control |

| Energy-degenerate states | States with identical net magnetization but distinct rectification properties | Bias-dependent TMR measurements | Suggests diode-like behavior dependent on spin configuration |

CrSBr, a van der Waals magnetic semiconductor, exhibits A-type antiferromagnetic order with direct bandgap semiconductor characteristics [15]. Magnetotransport measurements in few-layer CrSBr using vertical tunneling devices revealed that tunneling magnetoresistance can discern spin configurations indistinguishable by other techniques like photoluminescence.

Researchers observed energy-degenerate states with identical net magnetization but distinct rectification properties, manifesting as diode-like behavior at positive and negative bias voltages [15]. In 5-layer CrSBr devices, an intriguing positive magnetoresistive state emerged under in-plane magnetic fields along the b-axis. A one-dimensional linear chain model successfully computed the magnetic states, elucidating the spin configurations responsible for observed transport phenomena.

Fe/Gd Multilayers and Topological Textures

Table 3: Spin Textures in Fe/Gd Multilayers [16]

| Magnetic Texture | Field Range (at 300K) | Identifying Signature | Topological Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stripe domains | μ₀H ≤ 110 mT | Distinct coherent spin wave mode (mₛₜ) | Trivial |

| Bubble/Skyrmion (BSK) lattice | 110 mT < μ₀H < 250 mT | Unique breathing mode (mբₛₖ) | Mixed trivial and non-trivial |

| Saturated state | μ₀H ≥ 250 mT | Incoherent magnetization recovery | Trivial |

Fe/Gd multilayers host a rich variety of magnetic textures including topologically trivial bubbles and protected skyrmions [16]. The [Fe(0.35 nm)/Gd(0.40 nm)]₁₆₀ multilayer system exhibits three distinct magnetic phases depending on the applied out-of-plane magnetic field at constant temperature: stripe domains, a bubble/skyrmion lattice, and a saturated single-domain state.

Time-resolved Kerr spectroscopy identified each phase through their coherent spin wave modes, with the BSK lattice exhibiting a characteristic "breathing mode" [16]. The stability ranges of these textures strongly depend on both temperature and magnetic field history, demonstrating path-dependent phase behavior.

Methodologies for Probing Magnetic Phase Transitions

Muon Spin Relaxation (μSR)

Muon spin relaxation serves as a sensitive local probe for detecting weak dipolar fields and critical fluctuations associated with magnetic phase transitions [14]. In this technique, spin-polarized muons implanted in a sample precess in local magnetic fields, with depolarization rates revealing field distributions and dynamics.

For artificial kagome spin ice, muons implanted in a gold capping layer few tens of nanometers above the nanomagnets detected stray fields of approximately 10 Gauss [14]. The technique measures two relaxation rates: transverse (λT, sensitive to both static field distributions and fluctuations) and longitudinal (λL, sensitive only to fluctuations). Peaks in λL indicate critical slowing down at phase transitions, providing unequivocal signatures of second-order transitions.

Tunneling Magnetoresistance (TMR)

Tunneling magnetoresistance measurements probe magnetic configurations through their influence on electron tunneling probabilities [15]. In vertical tunneling devices with CrSBr as the barrier material, electrical resistance changes reflect the relative alignment of magnetic moments between layers.

This technique proved particularly sensitive for distinguishing spin configurations in CrSBr that remained indistinguishable to optical techniques like photoluminescence [15]. The bias-dependent rectification behavior further enabled differentiation of energy-degenerate states with identical net magnetization.

Time-Resolved Kerr Spectroscopy

Time-resolved Kerr spectroscopy detects magnetic spin textures through their coherent dynamics following ultrafast optical excitation [16]. The polar Kerr rotation signal reveals both incoherent demagnetization and recovery processes, along with coherent spin wave modes characteristic of specific magnetic textures.

This technique enabled mapping of (H,T) phase diagrams for Fe/Gd multilayers, distinguishing stripe domains, bubble/skyrmion lattices, and saturated states through their unique frequency signatures [16]. The approach benefits from sensitivity to nanoscale spin configurations without requiring direct real-space imaging.

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Magnetic Spin Texture Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permalloy nanomagnets | Building blocks for artificial spin ice | Single-domain, thermally active at room temperature | [14] |

| CrSBr crystals | Van der Waals magnetic semiconductor | A-type antiferromagnetism, direct bandgap | [15] |

| Fe/Gd multilayers | Platform for topological spin textures | [Fe(0.35 nm)/Gd(0.40 nm)]₁₆₀ structure | [16] |

| Pt seed layer | Substrate for multilayer growth | 5 nm thickness, promotes oriented growth | [16] |

| Si₃N₄ membranes | Substrates for LTEM measurements | Electron-transparent for direct imaging | [16] |

| Low-energy muons | Probe for local magnetic fields | Spin-polarized, sensitive to weak fields | [14] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Phase Transition Detection via μSR

Spin Texture Phase Mapping

Applications and Technological Implications

The controlled manipulation of magnetic phase transitions and spin textures enables numerous technological applications, particularly in information storage and processing. Spintronic devices leverage both charge and spin degrees of freedom for improved efficiency and functionality [15]. The non-trivial topology of skyrmions and related textures offers protection against defects, potentially enabling robust memory elements and unconventional computing paradigms [16].

Magnetic phase transitions also show promise for sensing applications, where subtle changes in temperature or magnetic field induce dramatic resistance changes through transitions between magnetic states [15]. The bias-dependent rectification in CrSBr further suggests potential for spin-based diode elements.

In quantum technologies, the precise control over magnetic phases and their transitions provides a platform for exploring quantum coherence and many-body phenomena. The ability to engineer degeneracies and controlled lifting through temperature or field variations offers routes to quantum模拟 of frustrated systems.

Thermodynamic phase transitions in magnetic spin textures represent a vibrant research area connecting fundamental physics with technological innovation. Experimental advances in artificial spin systems, van der Waals magnets, and topological multilayers have revealed rich phase behaviors including sequential ordering transitions, path-dependent phase stability, and topological protection. Sophisticated probing techniques including μSR, TMR, and time-resolved Kerr spectroscopy enable characterization of these transitions across temperature, field, and excitation conditions.

The integration of these magnetic systems into functional devices promises advances in computing, sensing, and energy technologies. Future research will likely focus on achieving room-temperature stability of topological phases, enhancing tunability through material design, and exploiting dynamic control of phase transitions for novel functionality. As fabrication techniques advance to create increasingly complex magnetic metamaterials, and characterization methods improve to probe faster dynamics and smaller length scales, our understanding and utilization of magnetic phase transitions will continue to deepen and expand.

The Interplay of Lattice Dynamics, Electronic Structure, and Magnetic Properties

The electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors of materials emerge from the complex interplay between their lattice dynamics, electronic structure, and magnetic properties. Understanding this relationship is fundamental to advancing materials research, particularly in fields as diverse as energy storage, catalysis, and drug development, where precise material control is paramount. Lattice dynamics govern how atoms vibrate and how heat propagates through a material, directly influencing its thermal conductivity and phase stability. These atomic vibrations interact strongly with the material's electronic structure—the arrangement of energy levels and electron orbitals—which in turn dictates electronic conductivity and optical properties. Simultaneously, the magnetic properties, arising from electron spins and their ordering, can be significantly modulated by both the lattice and electronic degrees of freedom. This tripartite coupling determines key functional characteristics, from a material's response to external magnetic fields to its performance in thermoelectric or spintronic applications. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these interconnected phenomena, supplemented by detailed experimental protocols and data presentation standards to enable rigorous research and verification.

Core Theoretical Framework

Lattice Dynamics and Phonons

Lattice dynamics describe the collective vibrational modes of atoms in a crystalline solid. These quantized vibrations, known as phonons, are not merely background perturbations but are active participants in determining electronic and magnetic behavior. The phonon dispersion relation, ω(k), which describes the relationship between the frequency (ω) and wavevector (k) of these vibrational modes, is a fundamental property that can be calculated from first principles using Density Functional Theory (DFT). Key theoretical constructs include the dynamical matrix, whose eigenvalues yield the phonon frequencies, and the phonon density of states (DOS), which provides the number of vibrational modes at a specific frequency. Notably, anomalies in phonon dispersion, such as the Kohn anomaly, can signal strong electron-phonon coupling. The strength of this coupling, quantified by the electron-phonon coupling constant, λ, directly influences phenomena such as electrical resistivity in metals and conventional superconductivity. Furthermore, lattice vibrations mediate spin-lattice interactions, whereby phonons can modulate exchange interactions between localized magnetic moments, leading to effects such as magnon-phonon hybridization.

Electronic Structure Fundamentals

The electronic structure of a material encompasses the allowed electron energy levels and their occupancy. DFT has become the cornerstone for ab initio calculation of electronic properties, enabling the prediction of band structures, density of states, and Fermi surfaces. The Kohn-Sham equations provide a practical framework for approximating the many-body Schrödinger equation, with the choice of exchange-correlation functional (e.g., LDA, GGA, or hybrid functionals) critically impacting accuracy. For strongly correlated systems, such as those containing d- or f-electron elements, methods like DFT+U or Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT) are often necessary to correctly describe electronic behavior. The calculated electronic DOS reveals whether a material is a metal, semiconductor, or insulator. Crucially, the Fermi surface topology dictates electronic transport properties and determines which phonon modes can effectively scatter electrons. The interplay with lattice dynamics enters through the electron-phonon interaction, which can renormalize electron energies, open band gaps at specific wavevectors, and facilitate phase transitions.

Magnetic Properties and Interactions

Magnetic properties in materials originate from the spin and orbital angular momenta of electrons and their complex interactions. The primary magnetic interactions include:

- Exchange interaction: The quantum mechanical effect responsible for the alignment of neighboring spins, giving rise to ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism, or more complex magnetic orders.

- Spin-orbit coupling (SOC): An interaction between an electron's spin and its motion, which can lock spin and charge directions, leading to anisotropic magnetic properties and topologically non-trivial band structures.

- Magnetic anisotropy: The dependence of magnetic energy on the direction of magnetization, crucial for stabilizing long-range magnetic order.

The Heisenberg Hamiltonian, H = -Σ Jᵢⱼ Sᵢ · Sⱼ, where Jᵢⱼ is the exchange integral and Sᵢ is the spin angular momentum at site i, provides a simplified model for describing many magnetic systems. The interplay with electronic structure is profound, as the exchange interaction J is itself a consequence of the electronic configuration and interatomic distance. Similarly, lattice vibrations can modulate J, creating a pathway for thermal demagnetization and influencing magnetic phase transitions.

Interplay and Coupling Mechanisms

The coupling between lattice, electronic, and magnetic subsystems gives rise to rich phenomenology:

- Magnetostriction: The deformation of a crystal lattice in response to a change in its magnetization, and its inverse, the variation of magnetic properties with applied strain.

- Magneto-caloric effect: The change in temperature of a magnetic material upon the application or removal of a magnetic field, governed by the coupling between magnetic moments and the lattice thermal bath.

- Spin-phonon coupling: A mechanism where phonons modulate exchange interactions, observable as shifts in phonon frequencies below magnetic ordering temperatures.

- Electron-phonon coupling: The interaction between electrons and lattice vibrations that governs conventional superconductivity, electrical resistivity, and charge-density-wave formation.

- Anomalous Hall effect: A Hall voltage arising from the material's intrinsic magnetism and spin-orbit coupling, rather than the external magnetic field alone.

Table 1: Key Coupling Phenomena in Materials

| Coupling Mechanism | Theoretical Description | Experimental Signature | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron-Phonon | Eliashberg function α²F(ω), coupling constant λ | Kink in ARPES dispersion; Raman linewidth | Superconductivity; Resistivity |

| Spin-Phonon | Hamiltonian: H = Σ ∂Jᵢⱼ/∂u Sᵢ·Sⱼ u (u: atomic displacement) | Frequency shift in phonon spectra below T꜀ | Magnetostriction; Multiferroicity |

| Spin-Orbit | Hamiltonian: H = ξ L·S | Magnetic anisotropy; Anomalous Hall effect | Topological insulators; Spintronics |

The visualization below illustrates the fundamental interactions and experimental characterization methods connecting lattice dynamics, electronic structure, and magnetic properties:

Diagram 1: Core Interplay and Characterization

Experimental Methodologies

Sample Synthesis and Characterization

The foundation of reliable research in this field lies in meticulous sample preparation and characterization. Single-crystal samples are often essential for angle-resolved measurements, while high-quality polycrystalline samples suffice for many bulk property investigations. The synthesis method must be explicitly documented with sufficient detail to enable reproduction, including precursor materials, synthesis atmosphere, thermal treatment profiles, and post-synthesis processing [17]. For materials sensitive to oxidation or hydration, handling procedures under inert atmosphere should be specified.

Upon synthesis, comprehensive structural characterization is imperative. X-ray diffraction (XRD) provides fundamental crystal structure information, phase purity, and crystallite size. The Rietveld refinement method should be employed for quantitative phase analysis and lattice parameter determination. For microscopic analysis, scanning/transmission electron microscopy (S/TEM) reveals morphological features, crystal structure, and elemental distribution via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The experimental section should explicitly state instrument models, operating conditions, and data analysis methods [18]. Specific characterization data should be presented in a standardized sequence: yield, melting point (if applicable), elemental analysis, spectral data (UV, IR, NMR), and mass spectrometry data, following established reporting conventions [18].

Probing Lattice Dynamics

Inelastic neutron scattering (INS) is the most direct technique for measuring phonon dispersion relations throughout the Brillouin zone. INS provides momentum-resolved information about phonon energies and lifetimes. Raman and infrared spectroscopy offer complementary approaches for probing zone-center phonons, with each technique sensitive to different symmetry modes. X-ray scattering can also probe phonons, particularly with the high brilliance of synchrotron sources. For thermal properties, specific heat measurements reveal lattice contributions through the Debye model, while thermal conductivity measurements provide information about phonon transport and scattering processes.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Lattice Dynamics

| Technique | Information Obtained | Sample Requirements | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inelastic Neutron Scattering | Full phonon dispersion, Density of States | Large single crystals (~cm³), Deuteration may be needed | Energy resolution, Momentum transfer |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Zone-center optical phonons, Symmetry | Powder, thin film, single crystal | Laser wavelength, Polarization configuration |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Zone-center IR-active phonons | Powder pellet, thin film | Spectral resolution, Temperature range |

| Specific Heat | Lattice contribution, Debye temperature | Bulk sample, ~mg to g | Temperature range, Measurement technique (PPMS) |

Electronic Structure Characterization

Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) directly measures the electronic band structure, Fermi surface, and many-body effects in materials. With spin-resolution (Spin-ARPES), it can additionally probe spin-texture of bands. Scanning tunneling microscopy/spectroscopy (STM/STS) provides real-space imaging of electronic structure with atomic resolution, capable of mapping local density of states and identifying defects. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) probe element-specific unoccupied and occupied electronic states, respectively. For bulk electronic properties, transport measurements (resistivity, Hall effect, thermopower) provide indirect but crucial information about carrier concentration, mobility, and scattering mechanisms. When reporting spectroscopic data, authors should include instrument frequency, solvent, and standard where applicable, following established conventions for data presentation [18].

Magnetic Property Measurements

Superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry remains the standard for DC magnetization measurements, providing information about magnetic ordering temperatures, susceptibility, and hysteresis. For AC susceptibility, specialized options exist within SQUID systems. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) provides element-specific magnetization information and can separately probe spin and orbital moments. Neutron diffraction is the definitive technique for determining magnetic structures, capable of identifying complex antiferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic, or non-collinear spin arrangements. Mössbauer spectroscopy is particularly powerful for studying iron-containing materials, providing hyperfine parameters that reflect local magnetic environment. For all magnetic measurements, it is critical to report the applied field direction relative to crystal axes and the measurement protocol (e.g., zero-field-cooled vs field-cooled).

The workflow below outlines a comprehensive experimental approach to investigating the interplay between these subsystems:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Experimental Workflow

Data Presentation and Analysis

Structural and Compositional Data

All experimental data must be presented with sufficient detail to enable verification and reproduction. For structural data from diffraction experiments, lattice parameters with estimated uncertainties should be reported. The crystallographic information file (.cif) for new structures must be deposited in appropriate databases (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database for small molecules) [19]. For elemental analysis, both found and calculated values should be presented in the form: "Found: C, 63.1; H, 5.4. C₁₃H₁₃NO₄ requires C, 63.2; H, 5.3%" [18]. When reporting NMR data, the format should include: "δH(100 MHz; CDCl₃; Me₄Si) 2.3 (3 H, s, Me)" specifying instrument frequency, solvent, standard, chemical shift, integration, multiplicity, and assignment [18].

Spectroscopic Data

Spectroscopic data should be presented with clear peak assignments and interpretations. For IR spectroscopy, report as: "νmax/cm⁻¹ 3460 and 3330 (NH), 2200 (conj. CN), 1650 (CO)" including both wavenumber and proposed assignments [18]. UV-Vis data should follow: "λmax(EtOH)/nm 228 (ε/dm³ mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ 40 900), 262 (19 200)" specifying solvent, wavelength, and extinction coefficients [18]. For mass spectrometry: "m/z 183 (M+, 41%), 168 (38)" indicating mass-to-charge ratio, ion identity, and relative intensity [18].

Physical Property Measurements

Electrical transport data should include resistivity vs. temperature, Hall coefficient, and thermopower where applicable. All measurements should include error estimates or standard deviations from multiple measurements. For magnetic data, report both field-cooled and zero-field-cooled magnetization when relevant, and include hysteresis loops with clear indication of saturation magnetization, coercive field, and remanence. For thermal measurements, specific heat data should be presented as Cₚ vs. T, with possible separation into electronic and lattice contributions.

Table 3: Representative Physical Property Data for Selected Materials

| Material | Crystal Structure | Magnetic Ordering Temperature (K) | Electrical Resistivity at 300K (μΩ·cm) | Debye Temperature (K) | Dominant Coupling Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | bcc | T꜀ = 1043 (Ferromagnetic) | 9.7 | 470 | Exchange (direct) |

| MnF₂ | Rutile | T꜀ = 67 (Antiferromagnetic) | ~10¹² (Insulator) | 450 | Superexchange |

| La₂CuO₄ | Layered Perovskite | T꜀ = 320 (Antiferromagnetic) | Anisotropic | 390 | Superexchange |

| EuO | Rocksalt | T꜀ = 69 (Ferromagnetic) | Metal-insulator transition at T꜀ | 200 | Double Exchange |

| Cr | bcc | T꜀ = 311 (Antiferromagnetic) | 12.7 | 630 | Spin-density wave |

Computational Approaches

First-Principles Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the foundation for most first-principles calculations of materials properties. The choice of exchange-correlation functional is critical, with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) being widely used for structural properties. For more accurate electronic structure, particularly band gaps, hybrid functionals (HSE06) or GW approximations are often necessary. For strongly correlated systems, DFT+U incorporates an on-site Coulomb repulsion term to better describe localized d or f electrons. The projector augmented-wave (PAW) method and plane-wave basis sets with appropriate energy cutoffs represent standard technical approaches.

Calculating Specific Properties

Phonon spectra can be calculated using the finite displacement method or density functional perturbation theory (DFPT). The former involves creating supercells with atomic displacements and calculating force constants, while DFPT employs a linear response approach. For electron-phonon coupling, the preferred method involves computing the change in Kohn-Sham potential with respect to atomic displacements. Magnetic exchange parameters Jᵢⱼ can be extracted from DFT calculations by comparing the energies of different magnetic configurations or using the magnetic force theorem. For spin-phonon coupling, calculations typically involve computing phonon frequencies in different magnetic states or applying frozen phonon approaches to magnetic supercells.

Software and Implementation

Multiple software packages implement these computational methods, including VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, WIEN2k, and ABINIT. Computational details must be thoroughly documented, including pseudopotentials, basis set, k-point mesh, energy convergence criteria, and any U values applied. For reproducibility, computational data and input files should be deposited in appropriate repositories, as required by leading journals [19]. When reporting computational results, authors should include convergence tests with respect to key parameters to establish the numerical accuracy of their predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Elements (e.g., Fe, Mn, Eu) | Starting materials for sample synthesis | 99.99% purity or higher, metal basis | Argon glove box for air-sensitive materials |

| Single Crystal Substrates (e.g., MgO, SrTiO₃) | Epitaxial thin film growth | Lattice matching to target material | Surface preparation (annealing, etching) |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | NMR spectroscopy solvent | 99.8 atom % D | Moisture protection, storage conditions |

| Silicon Calibrant | XRD alignment and calibration | NIST-traceable standard | Surface cleanliness, proper mounting |

| Gadolinium Standard | Calibration of SQUID magnetometers | Temperature and field calibration | Avoid introduction of ferromagnetic impurities |

| Iridium Crucibles | Crystal growth of reactive materials | High-temperature stability, chemical inertness | Pre-cleaning at high temperature |

| Cryogenic Liquids (He, N₂) | Low-temperature measurements | Liquid He-4 (4.2K), Liquid N₂ (77K) | Safety protocols for cryogen handling |

Data Deposition and Reproducibility

Adherence to data sharing policies is essential for advancing materials research. All primary data supporting the conclusions of a study must be made available either through deposition in appropriate repositories or as supplementary information [19]. Specific data types have mandated deposition requirements: crystallographic data should be deposited with the Cambridge Structural Database (CCDC) or Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), theoretical input/output files in specialized repositories such as the NOMAD repository, and spectroscopic data in domain-specific databases [19]. The data availability statement has become a mandatory component of scientific publications, requiring precise description of how and where data can be accessed [19]. For computational studies, this includes deposition of input parameters and resulting structures. Authors should be prepared to provide original, unprocessed data to editors and reviewers during peer review if requested [18]. When data access is subject to controlled access due to privacy or ethical concerns, the data availability statement should precisely describe the conditions for access, including contact details and the expected timeframe for response to requests [19]. These practices ensure research verifiability and enable the scientific community to build upon published work.

Key Physical Descriptors Governing Proton Conduction and Ionic Diffusion

The pursuit of clean energy technologies, such as fuel cells and solid-state batteries, has placed the fundamental science of ion transport at the forefront of materials research. Understanding and controlling proton conduction and ionic diffusion is critical for developing next-generation energy converters and storage devices. These processes are governed by a complex interplay of atomic-scale interactions, collective dynamics, and material structure. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the key physical descriptors that dictate ionic mobility, framing them within the broader context of the electrical, magnetic, and thermodynamic behaviors of materials. It provides a comprehensive framework for researchers aiming to design advanced materials with tailored transport properties, detailing fundamental mechanisms, quantitative descriptors, experimental probing techniques, and essential research tools.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Proton and Ion Transport

Ionic conduction in condensed phases occurs through two primary mechanistic classes: structural diffusion (involving the concerted motion of charge carriers relative to the host matrix) and vehicular diffusion (involving the physical displacement of charged species).

The Grotthuss Mechanism and Proton Hopping

The Grotthuss mechanism describes proton transport via a structural diffusion process where protons move through a hydrogen-bonded network by successive bond formation and breaking [20]. This mechanism does not require the physical diffusion of the molecular species to which the protons are attached. In proton-conducting perovskites used in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), the Grotthuss mechanism decomposes into two elementary steps [21]:

- Proton Rotation: The reorientation of an O-H bond around a single oxygen ion within its coordination sphere.

- Proton Transfer: The jumping of a proton from an oxygen ion to an adjacent oxygen ion in a neighboring site.

The rate-limiting nature of these steps is governed by hydrogen bond strength. Generally, proton transfer exhibits a higher energy barrier than rotation and is thus often the rate-limiting step; however, in systems with very strong hydrogen bonds, the energy barrier for rotation becomes significant and non-negligible [21]. The formation of transient, strong hydrogen bonds, facilitated by thermal lattice vibrations (phonons), is crucial for enabling efficient proton transfer [21].

The Vehicle Mechanism

In contrast to the Grotthuss mechanism, the vehicle mechanism involves proton or ion transport via the physical diffusion of a charged carrier vehicle, such as a hydrated proton (H₃O⁺) or an ionic phosphate species (e.g., H₂PO₄⁻) [22]. This mechanism dominates when the hydrogen-bonded network is underdeveloped or when stable, diffusive charged species are present in high concentrations. The conductivity via this pathway is directly linked to the viscosity and structural relaxation dynamics of the medium, as it is governed by the same molecular friction that impedes molecular diffusion [20]. In many practical systems, such as diphosphoric acid, the total ionic conductivity results from a combination of both Grotthuss and vehicle contributions, each accounting for a significant portion of the overall conductivity [22].

Correlated Ionic Hopping and Orientational Memory

In solid-state ion conductors, the fundamental step of diffusion is an ion hop—a rare-event, large-amplitude translation between lattice sites. Recent nonlinear optical studies have revealed that these hops are not always memoryless, Markovian steps as assumed in simple random-walk models [23]. Instead, correlated hopping can occur, where the direction of a subsequent hop is influenced by the preceding one. This correlation leads to a persistence of orientational memory, measured as a transient anisotropy in hopping directions following an impulsive trigger. The relaxation of this anisotropy occurs over a finite timescale (picoseconds to nanoseconds), during which the full entropy of transport is not yet realized. This memory effect signifies that the ionic conduction process can be a multi-step, correlated phenomenon rather than a simple Poissonian process, which has critical implications for accurately predicting and modeling transport properties [23].

Quantitative Descriptors and Material Properties

The efficiency of ion conduction is governed by a set of quantifiable physical descriptors that determine the kinetics and thermodynamics of the transport process.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Descriptors Governing Proton and Ion Conduction

| Descriptor | Definition & Physical Meaning | Impact on Conduction | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (Eₐ) | Energy barrier for a hopping event (rotation or transfer). | Determines the temperature dependence of conductivity (Arrhenius law). | Proton transfer: ~0.28 eV in BaHfO₃; Rotation: ~0.15 eV [21]. |

| Attempt Frequency (ν₀) | Pre-exponential factor; vibrational frequency of the ion in its potential well. | Governs the intrinsic rate of hopping attempts. | Proton transfer: ~3000 cm⁻¹; Rotation: ~1500 cm⁻¹ [21]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Strength / Length | Measure of the interaction strength between a proton donor and acceptor. | Dictates the rate-limiting step; weaker bonds favor transfer as the bottleneck. | A critical length distinguishes strong/weak bonds [21]. |

| Glass Transition Temp. (T𝗀) | Temperature where a liquid or soft material becomes a glassy solid. | Below T𝗀, vehicle mechanism is frozen; only Grotthuss may operate. | Varies with material; can be tuned by molecular design [20]. |

| Transient Anisotropy Decay Time | Timescale for the loss of orientational memory after a triggering event. | Measures the persistence of correlated hopping; shorter times suggest faster memory loss. | ~10 ps at 300 K to ~3-4 ps at 620 K in K⁺ β-alumina [23]. |

Table 2: Contributions to Total Conductivity in Different Material Systems

| Material System | Total Conductivity | Grotthuss Contribution | Vehicle Contribution | Dominant Rate-Limiting Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diphosphoric Acid (H₄P₂O₇) at 160°C | ~0.2 S/cm | ~0.1 S/cm (estimated 50%) | ~0.1 S/cm (estimated 50%) | Proton transfer within H-bond network & diffusion of phosphate ions [22]. |

| Protic Ionic Liquid/Imidazole (Low [Imidazole]) | Composition-dependent | More pronounced | Less dominant | Proton transfer, as imidazole acts as a base pulling protons [24]. |

| Protic Ionic Liquid/Imidazole (High [Imidazole]) | Composition-dependent | Less favored (H-bonds too stable) | Dominant | Vehicle mechanism due to stable, chain-like H-bonding [24]. |

| BaHfO₃ Perovskite at 500 K | Governed by hopping rates | Primary mechanism (sole mechanism) | Not applicable | Proton transfer, due to higher barrier (0.28 eV) vs. rotation (0.15 eV) [21]. |

The relationship between key processes and descriptors in proton conduction can be visualized as a logical pathway, as shown in the following diagram.

Experimental Protocols for Probing Transport Mechanisms

Elucidating the dominant conduction mechanism and quantifying the relevant descriptors requires a combination of advanced experimental techniques.

Terahertz-Pumped Kerr Effect (TKE) Spectroscopy

This nonlinear optical method is used to impulsively trigger and temporally resolve anisotropic ionic hopping, providing direct insight into correlated ion dynamics [23].

Detailed Methodology:

- Pump Pulse: A single-cycle terahertz (THz) pulse (center frequency ~0.7 THz) is used to impulsively align ions or trigger hops along a preferential direction defined by the pump electric field vector.

- Probe Pulse: A delayed, weaker optical probe pulse is sent through the sample in a direction perpendicular to the pump.