Functionalized MOFs for CO2 Capture: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis of Performance, Mechanisms, and Future Applications

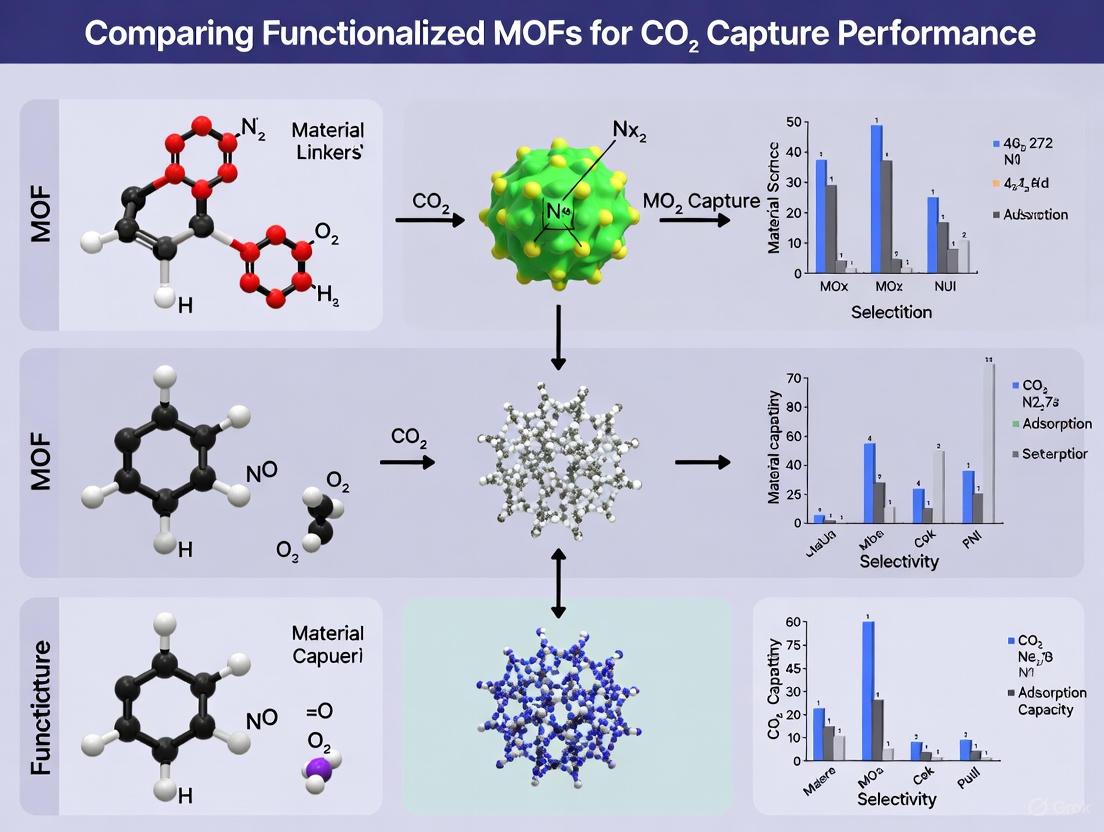

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of various functionalized Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for carbon dioxide capture, addressing key considerations for researchers and scientists.

Functionalized MOFs for CO2 Capture: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis of Performance, Mechanisms, and Future Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of various functionalized Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for carbon dioxide capture, addressing key considerations for researchers and scientists. It explores foundational mechanisms of CO2 adsorption through chemisorption and physisorption, evaluates contemporary synthesis and functionalization methodologies, and examines performance optimization strategies for challenging environments. The analysis includes comparative assessment of MOFs against other porous materials and different MOF families, highlighting commercialization progress, scalability challenges, and environmental impact considerations. By synthesizing recent advancements and practical implementation challenges, this review aims to guide the development of next-generation, high-efficiency MOF-based carbon capture technologies.

The Fundamental Building Blocks of MOFs for Carbon Capture

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline porous materials formed through the self-assembly of metal ions or clusters and organic linkers, creating structures with exceptional porosity and surface area. [1] [2] Their chemical tunability allows for precise design of materials for specific applications, making them a premier platform for advanced technologies like carbon capture, catalysis, and energy storage. [3] [2] This guide objectively compares the performance of various functionalized MOFs, focusing on their efficacy in CO2 capture, a critical technology for mitigating climate change. [4] [5]

Core Structural Principles of MOFs

The defining characteristic of MOFs is their extreme porosity. This arises from their network structure, where inorganic metal nodes are connected by organic linkers, forming a framework with a vast internal surface area. [1] Just a few grams of MOF powder can have an internal surface area the size of a football pitch, making them the most porous known solid materials. [6] This porosity is not static; it can be tuned by selecting different building blocks. The size and geometry of the organic ligands directly influence the pore size and volume, while the choice of metal node affects the coordination environment and framework stability. [1] [7]

A key advantage of MOFs over traditional porous materials like zeolites or activated carbon is their highly tunable structure. [1] [5] This tunability operates on two levels: first, through the selection of primary building blocks during synthesis, and second, through post-synthetic modification of the framework itself. [2] This allows for the incorporation of various functional groups—such as -NH2, -NO2, or -SO2—that can dramatically alter the chemical properties and gas affinity of the MOF, enabling optimization for specific tasks like selective CO2 adsorption. [4] [7]

Performance Comparison of Functionalized MOFs for CO₂ Capture

The performance of MOFs in CO2 capture is evaluated using multiple metrics, including adsorption selectivity (Sads), which measures the material's ability to preferentially adsorb CO2 over other gases like N2; working capacity (ΔN), the usable amount of CO2 captured per cycle; and energy efficiency (η), which balances performance with the energy cost of regeneration. [4] Functionalization introduces specific chemical groups that interact strongly with CO2 molecules, enhancing these metrics.

The following table summarizes the performance of different functionalized MOFs compared to a non-functionalized (pristine) benchmark, based on a high-throughput computational screening of 4,797 structures. [4]

Table 1: Comparative CO₂ Capture Performance of Functionalized MOFs

| Functional Group | CO₂ Working Capacity (ΔN, mmol/g) | CO₂/N₂ Selectivity (Sads) | CO₂/CH₄ Selectivity (Sads) | Key Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine (None) | 2.34 | 40.36 | 24.94 | Physisorption / Van der Waals forces |

-NO2 (Nitro) |

5.91 - 7.94 | 176.87 | 121.11 | Enhanced polar interactions |

-SO2 (Sulfonyl) |

5.91 - 7.94 | 215.54 | 149.94 | Strong polar interactions and dipole moments |

-OLi (Lithium alkoxide) |

5.91 - 7.94 | 267.44 | 158.64 | Very strong electrostatic interactions |

-NH2 (Amino) |

Moderate increase | 46 | 31 (reported elsewhere) [4] | Chemisorption / Acid-base reaction |

A critical trade-off in optimization is that enhanced CO2 affinity often increases the energy required to release the captured CO2 and regenerate the material. The -OLi group, while showing the highest selectivity, also has a high isosteric heat of adsorption (-30.09 kJ/mol), which can reduce renewability by approximately 50%. [4] To resolve this, a holistic energy efficiency (η) metric is used. When this is considered, the -SO2 functional group emerges as a top performer (η = 12.78 for CO₂/N₂), balancing exceptional capture performance with manageable energy inputs for regeneration. [4]

Table 2: Energy and Stability Metrics of Functionalized MOFs

| Functional Group | Isosteric Heat of Adsorption (Qst, kJ/mol) | Estimated Renewability (R) | Energy Efficiency (η) for CO₂/N₂ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine (None) | ~24 - 31 (varies) | High (Baseline) | 2.18 |

-NO2 |

-29.15 | Reduced by ~50% | Not Specified |

-SO2 |

-29.96 | Reduced by ~50% | 12.78 |

-OLi |

-30.09 | Reduced by ~50% | Not Specified |

-NH2 |

~31 (reported elsewhere) [4] | Lower due to H₂O competition [4] | Not Specified |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The synthesis and functionalization of MOFs require a specific set of chemical reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions in MOF research, particularly for CO2 capture studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MOF Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function and Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors (e.g., Zn, Cu, Cr salts) | Serves as the source of metal ions or Secondary Building Units (SBUs) that form the nodes of the MOF framework. [1] [5] |

| Organic Linkers (e.g., terephthalate, imidazolates) | Multidentate molecules that connect metal nodes to form the porous framework; the backbone for functionalization. [1] [3] |

Functional Group Modifiers (e.g., -NH2, -NO2, -SO2 precursors) |

Introduced via post-synthetic modification or directly on the linker to tune the MOF's chemical affinity and selectivity for CO2. [4] [5] |

| Polar Solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO) | Used in solvothermal synthesis to dissolve metal salts and organic linkers, facilitating self-assembly into crystalline MOFs. [5] |

| Amine-based Solvents (e.g., MEA) | Common industrial absorbents for CO2; used as a benchmark for comparing the performance of MOF-based capture systems. [2] |

Standard Experimental Workflows

The development and evaluation of functionalized MOFs follow a systematic workflow, from material design to performance assessment. High-throughput computational screening has become a powerful tool for navigating the vast design space efficiently. [4]

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Screening Workflow for MOFs. APS: Adsorbent Performance Score; Ssp: Sorbent Selection Parameter; η: Energy Efficiency.

A critical part of the workflow involves understanding how structural modifications affect the MOF's electronic properties, which in turn govern host-guest interactions with CO2 molecules. Computational methods like Density-Functional Theory (DFT) are key for this. [7]

Diagram 2: MOF Electronic Structure Tuning for Enhanced CO₂ Capture.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Computational Screening Protocol

This protocol, derived from a study screening 4,797 MOFs, identifies top candidates before resource-intensive lab synthesis. [4]

- Database Construction: Use software like Topologically based Crystal Constructor (ToBaCCo) to generate hypothetical MOF structures. Inputs include:

- Topological blueprints (e.g., 36 common net topologies).

- Molecular building blocks: 10 metal centers (e.g., Zn, Cu) and 144 functionalized ligands (18 base ligands modified with 8 functional groups:

–NH2,–NO2,–CH3,–CF3,–SH2,–SO2,–OH, and–OLi).

- Structural Filtering: Eliminate non-viable structures by applying filters. A common filter is a Porosity Limiting Diameter (PLD) below 3.3 Å (the kinetic diameter of CO2) to ensure CO2 molecules can enter the pores.

- Property Calculation: Use computational methods (e.g., Grand Canonical Monte Carlo simulations) to calculate key performance indicators for the remaining structures:

- Adsorption selectivity (Sads) for CO₂ over N₂ and/or CH₄.

- Working capacity (ΔN) between adsorption and desorption conditions.

- Isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) to estimate regeneration energy.

- Multi-Metric Evaluation: Rank candidates using composite metrics like:

- Adsorbent Performance Score (APS)

- Sorbent Selection Parameter (Ssp)

- Energy Efficiency (η), which integrates performance with energy inputs.

Experimental CO₂ Adsorption Measurement (Breakthrough Test)

This protocol measures the dynamic adsorption capacity and selectivity of a synthesized MOF under mixed-gas conditions, closely mimicking real-world applications. [8]

- Sorbent Preparation: Activate the synthesized MOF sample (e.g., ~100-500 mg) under vacuum or inert gas flow at elevated temperature (e.g., 150°C) to remove all solvent and moisture from the pores.

- Gas Mixture Preparation: Prepare a gas mixture representing a target stream, such as 15% CO₂ and 85% N₂ for post-combustion flue gas simulation.

- Breakthrough Test Setup:

- Pack the activated MOF into a fixed-bed adsorption column.

- Maintain the column at a constant temperature (e.g., 25-40°C).

- Pass the gas mixture through the column at a constant flow rate (e.g., 10-100 mL/min).

- Effluent Concentration Monitoring: Use a downstream detector (e.g., Mass Spectrometer or Gas Chromatograph) to measure the concentration of CO₂ and other gases exiting the column in real-time.

- Data Analysis:

- Record the breakthrough time when the outlet CO₂ concentration reaches a defined percentage (e.g., 10%) of the inlet concentration.

- Calculate the dynamic adsorption capacity by integrating the area above the breakthrough curve.

- Calculate selectivity based on the different breakthrough times of CO₂ and the competing gas (e.g., N₂).

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a critical technology for mitigating global climate change by reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Among different capture techniques, adsorption using porous solid sorbents has gained significant attention as a promising alternative to traditional liquid amine scrubbing, which faces challenges related to energy-intensive regeneration, corrosion, and solvent expense [9]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as particularly versatile adsorbents due to their exceptional structural tunability, high surface areas, and programmable pore environments [5].

The effectiveness of MOFs in capturing CO2 fundamentally depends on two primary mechanisms: physisorption and chemisorption. Physisorption involves weak van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and quadrupole moments, while chemisorption entails stronger chemical bond formation through acid-base reactions or covalent bonding [5]. The strategic design of MOFs, particularly through functionalization, enables precise control over these mechanisms to optimize CO2 capture performance under various conditions. This review comprehensively compares these pathways within functionalized MOFs, providing researchers with experimental data, methodologies, and frameworks to guide material selection and design.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Material Design

Physisorption in MOFs

Physisorption relies on non-covalent interactions between CO2 molecules and the adsorbent surface. In MOFs, these interactions occur through several mechanisms:

- Van der Waals forces: Generated through induced dipole interactions between CO2 and the framework

- Quadrupole interactions: CO2 possesses a significant quadrupole moment that interacts with electric fields within MOF pores

- π-π interactions: Aromatic rings in organic linkers can interact favorably with CO2 molecules

The performance of physisorption is heavily influenced by MOF textural properties. Higher surface areas provide more sites for gas adsorption, while optimal pore architecture facilitates gas diffusion and accessibility to adsorption sites [5]. Pore size distribution and overall pore volume are critical for maximizing physisorption capacity, with optimal performance typically observed when pore dimensions are slightly larger than the kinetic diameter of CO2 molecules (approximately 3.3 Å) [4].

A key advantage of physisorptive MOFs is their lower regeneration energy requirements compared to chemisorbents. Since the binding forces are weaker, CO2 can typically be desorbed through modest changes in temperature or pressure, making these materials energy-efficient for cyclic capture processes [9].

Chemisorption in MOFs

Chemisorption involves the formation of stronger chemical bonds between CO2 and specific functional groups within the MOF structure. This pathway typically provides:

- Higher binding energies (typically 40-100 kJ/mol)

- Improved selectivity for CO2 over other gases

- Enhanced performance in low-pressure or dilute CO2 streams

The most common strategy for introducing chemisorptive sites in MOFs is through amine functionalization, where amine-containing molecules are grafted onto the framework or incorporated as part of the organic linker [5]. These functional groups react with CO2 to form carbamates or ammonium carbamates through acid-base reactions.

Recent advances have expanded the chemical diversity of chemisorptive MOFs beyond amine chemistry. Functional groups including -SO2, -OLi, and -NO2 have demonstrated significant enhancements in CO2 capture performance, with computational screening revealing substantial improvements in working capacity and selectivity [4]. For instance, incorporating -SO2 groups increased CO2 selectivity over N2 from 40.36 in pristine MOFs to 215.54 in functionalized versions [4].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Functionalized MOFs for CO2 Capture

| Functional Group | CO2 Uptake (mmol/g) | CO2/N2 Selectivity | Isosteric Heat (kJ/mol) | Working Capacity (mmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine MOF | 1.44-1.95 | 24.94/40.36 | 24-31 | 2.34 |

| -NH2 | 1.94-2.23 | 46-387 | ~31 | 3.12 |

| -NO2 | 2.1-2.5 | 121.11/176.87 | -29.15 | 5.91 |

| -SO2 | 2.23* | 149.94/215.54 | -29.96 | 7.94 |

| -OLi | 2.5* | 58.64/267.44 | -30.09 | 6.87 |

| -OH | 1.82* | 34.17/35.43 | -33.63 | 3.45 |

| -COOH | 1.82* | 34.17/35.43 | -30.10 | 2.98 |

Note: Values marked with * represent representative examples from specific MOF families. Performance metrics vary based on MOF structure and measurement conditions [4] [5].

Table 2: Trade-offs Between Physisorption and Chemisorption Dominated MOFs

| Parameter | Physisorption-Dominated | Chemisorption-Dominated |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy | Low (20-40 kJ/mol) | High (40-100 kJ/mol) |

| Regeneration Energy | Low | High |

| Adsorption Kinetics | Fast | Slower |

| Capacity at Low P | Low | High |

| Capacity at High P | High | Moderate |

| Moisture Tolerance | Variable | Generally Good |

| Cyclic Stability | Excellent | Good to Moderate |

| Temperature Range | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of Functionalized MOFs

Amine-Functionalized MOFs Protocol:

- Method: Solvothermal synthesis

- Procedure: Combine amine-based ligand with metal source (e.g., Cu, Zn, Mg) in organic solvent (typically DMF). Transfer to Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 85-120°C for 12-48 hours. Cool slowly to room temperature. Recover crystals via filtration and activate under vacuum at elevated temperatures (150-200°C) [5].

- Key Considerations: Amine loading must be optimized to balance CO2 capacity with porosity retention. Excessive functionalization can block pores and reduce accessibility.

High-Throughput Computational Screening:

- Database Construction: Systematic generation of MOF structures using topologically-based crystal construction (ToBaCCo) tools, incorporating diverse functional groups (-NH2, -NO2, -CH3, -CF3, -SH2, -SO2, -OH, -OLi) on organic ligands combined with various metal centers [4].

- Screening Metrics: Evaluation based on multiple performance indicators including adsorption selectivity (Sads), working capacity (ΔN), adsorbent performance score (APS), sorbent selection parameter (Ssp), and renewability (R) [4].

- Energy Efficiency Analysis: Introduction of a novel energy efficiency (η) metric that holistically evaluates both adsorption performance and energy inputs (desorption heat, pressure-swing energy, net loss) [4].

Characterization Techniques

- Surface Area and Porosity: N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K analyzed using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory for surface area and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method for pore size distribution [5] [10].

- Structural Analysis: Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) to determine crystallinity, phase purity, and structural integrity after functionalization [5] [11].

- Chemical Functionality: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify and quantify functional groups and their interactions with CO2 [10].

- Thermal Stability: Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to assess framework stability and decomposition profiles under operational conditions [10].

- Adsorption Performance: CO2 adsorption isotherms measured volumetrically or gravimetrically at relevant temperatures (25-40°C) and pressures (0-1 bar for post-combustion capture, up to 30 bar for pre-combustion) [5] [10].

Advanced Analysis and Emerging Trends

Machine Learning in MOF Screening

The vast chemical space of possible MOF structures necessitates advanced computational approaches for efficient screening. Recent studies have demonstrated the power of machine learning (ML) in predicting CO2 adsorption performance and guiding experimental synthesis:

- Ensemble Learning Models: Integration of multiple regression algorithms (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, Support Vector Regression, Multi-Layer Perceptron) into custom ensemble strategies significantly improves prediction accuracy for CO2 uptake, achieving R² values up to 0.9833 [12].

- Feature Importance Analysis: ML models identify pressure and temperature as the most influential features for CO2 adsorption, followed by BET surface area and pore volume [12].

- High-Throughput Datasets: The Open DAC 2025 (ODAC25) dataset provides nearly 60 million DFT calculations across 15,000 MOFs with four adsorbates (CO2, N2, O2, and H2O), enabling robust training of ML models and accelerating sorbent discovery [13].

Water-Enhanced CO2 Capture

The presence of water vapor in flue gas and ambient air traditionally complicates CO2 capture, as water often competes with CO2 for adsorption sites. However, recent studies have revealed a counterintuitive phenomenon: certain MOFs exhibit enhanced CO2 uptake under humid conditions through several mechanisms:

- Dipole-Quadrupole Interactions: Water molecules coordinated to open metal sites in MOFs like Cu-HKUST-1 generate electric fields that enhance CO2 adsorption through interactions with its quadrupole moment, increasing uptake by approximately 5 wt% at 2-4% relative humidity [14].

- Optimal Pyrene Stacking: MOFs with parallel aromatic rings (e.g., M-TBAPy series with M = Al, Ga) at optimal interlayer distances (6.5-7.0 Å) create favorable binding sites for CO2 while exhibiting lower affinity for H2O, maintaining performance in humid conditions [11].

- Defect Engineering: Missing linker defects in UiO-66 promote water-enhanced CO2 capture at low water loadings (1.5 mol/kg) and low CO2 partial pressures (<5 kPa) [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MOF CO2 Capture Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Form metal nodes and secondary building units (SBUs) | Metal nitrates (e.g., Zn(NO3)2, Cu(NO3)2), chlorides, or acetates; Selection influences framework stability and open metal sites [5] |

| Organic Linkers | Bridge metal nodes to create porous frameworks | Carboxylate-based (e.g., terephthalate, TBAPy), azolates; Aromaticity and length control pore size and functionality [11] |

| Functionalization Agents | Introduce specific chemical groups for enhanced CO2 binding | Amines (e.g., ethylenediamine), -SO2, -OLi, -NO2 containing molecules; Grafted post-synthesis or incorporated as modified linkers [4] [5] |

| Solvents | Medium for solvothermal synthesis and activation | Dimethylformamide (DMF), diethylformamide, acetonitrile, water; Choice affects crystallization and final morphology [5] |

| Modulators | Control crystal growth and introduce defects | Monocarboxylic acids (e.g., acetic acid, benzoic acid); Concentration influences crystal size and defect density [11] |

| Characterization Standards | Validate material properties and performance | N2 (77K) for surface area analysis, CO2 (273K, 298K) for capture capacity, reference materials for instrument calibration [5] [10] |

The strategic selection between chemisorption and physisorption pathways in functionalized MOFs enables precise optimization of CO2 capture materials for specific applications. Physisorption-dominated MOFs offer advantages in regeneration energy and cyclic stability, making them suitable for high-pressure or high-concentration capture scenarios. In contrast, chemisorption-dominated MOFs excel in low-pressure applications and environments where high selectivity is paramount.

Functionalization with specific groups (-SO2, -OLi, -NH2, -NO2) dramatically enhances CO2 capture performance, but introduces trade-offs between adsorption strength and regenerability that must be carefully balanced [4]. Emerging computational approaches, including high-throughput screening and machine learning, are accelerating the discovery of optimal materials by efficiently navigating the vast MOF design space [4] [12] [13].

Future research directions should focus on developing more cost-effective synthesis routes, enhancing material stability under real-world conditions, and designing multi-functional MOFs that integrate capture with subsequent conversion of CO2 to valuable products [9] [15]. The ongoing refinement of both chemisorptive and physisorptive MOFs will continue to advance carbon capture technologies, contributing significantly to global climate mitigation efforts.

The escalating concentration of atmospheric CO₂ is a principal driver of global climate change, necessitating the development of efficient carbon capture technologies [16] [14]. Among various adsorbents, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as a premier class of porous materials due to their exceptional tunability, high surface areas, and structural diversity [16] [17]. The performance of MOFs in CO₂ capture is primarily governed by three key metrics: capacity (the amount of CO₂ adsorbed), selectivity (the preferential adsorption of CO₂ over other gases like N₂), and kinetics (the rate of adsorption/desorption) [16]. While unmodified MOFs show promise, their practical application is often hindered by insufficient performance in these areas under real-world conditions [16]. This guide objectively compares the performance of functionalized MOFs against their pristine counterparts and other alternatives, providing a detailed analysis of the experimental data and methodologies that underpin these advancements.

Performance Metrics Comparison

The following tables summarize quantitative data on the CO₂ capture performance of various MOFs, highlighting the effects of different functionalization strategies on capacity, selectivity, and kinetics.

Table 1: Comparison of CO₂ Adsorption Capacity in Functionalized vs. Pristine MOFs

| MOF Name | Functionalization Strategy | CO₂ Capacity | Conditions (Temp, Pressure) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUST-4 | Dual-ligand strategy (Cd/Zn heterometallic) | 168 cm³/g | 25 °C, 1 bar | [18] |

| MOF-177 | TEPA (tetraethylenepentamine) impregnation | 3.8 mmol·g⁻¹ | 298 K, 1 bar | [16] |

| MOF-177 | Pristine (unmodified) | 1.18 mmol·g⁻¹ | 298 K, 1 bar | [16] |

| IUST-2 | Pristine (Zn-based) | ~85 cm³/g (estimated from data) | 25 °C, 1 bar | [18] |

| IUST-3 | Pristine (Cd-based) | ~95 cm³/g (estimated from data) | 25 °C, 1 bar | [18] |

| Cu-HKUST-1 | Hydrated (4 wt% water) | ~5% increase vs. dry | 298 K, 1 bar | [14] |

Table 2: CO₂ Selectivity and Kinetic Performance of Functionalized MOFs

| MOF Name | Functionalization | CO₂/N₂ Selectivity | Kinetics & Stability Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUST-4 | Dual-ligand (Cd/Zn) | Significantly enhanced (Stronger Eₐᵈₛ=-0.11 eV) | 86.1% capacity retention after 10 cycles | [18] |

| Diamine-appended MOFs | e.g., N,N'-dimethylethylenediamine | High for CO₂ over H₂O | Introduces chemisorption, may affect kinetics | [14] |

| M-HKUST-1 (M=Zn, Co, Ni) | Water coordination at open metal sites | Enhanced selectivity over N₂ | Improved capacity at low humidity; degrades at high RH | [14] |

| UiO-66 | Presence of missing-linker defects | Enhanced at low H₂O loading | Stable; performance dependent on defect type | [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of performance data for functionalized MOFs, researchers adhere to standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines the key stages from material synthesis to performance evaluation, while the subsequent section details common synthesis and characterization techniques.

Experimental Workflow for MOF Evaluation

Synthesis and Functionalization Protocols

The path to tailoring MOF properties begins with synthesis and functionalization, which directly influence the material's intrinsic structure and potential active sites.

Synthesis Methods: The formation of MOFs is highly dependent on reaction parameters like temperature, duration, and pH [16].

- Solvothermal/Hydrothermal Synthesis: This is a conventional method involving reactions in a sealed vessel at elevated temperatures, which promotes crystallization [16] [19].

- Sonochemical Synthesis: This method utilizes ultrasonic radiation to generate bubbles that collapse violently, creating local hot spots. This enables fast, eco-friendly reactions and uniform crystal growth, as demonstrated in the synthesis of IUST-series MOFs [18].

- Electrochemical Synthesis: An alternative technique that allows for better control over the synthesis process and the formation of thin MOF films [19].

Functionalization Strategies: Incorporating specific functional groups is crucial for enhancing CO₂ affinity.

- Pre-synthetic Functionalization: This involves using pre-functionalized organic linkers (e.g., with -NO₂, -OH, -COOH, -SO₃H) during the initial synthesis to directly incorporate desired functionalities into the MOF framework [16].

- Post-synthetic Modification (PSM): This strategy involves modifying pre-formed MOFs, for example, by grafting amine-containing molecules like diamines onto open metal sites (OMSs) to create strong chemisorption sites for CO₂ [16] [14].

Characterization and Performance Testing

Once synthesized, MOFs undergo rigorous characterization and testing to link their physical and chemical properties to performance metrics.

Material Characterization: Essential for confirming successful synthesis and understanding structural properties.

- Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): Used to verify the crystalline structure and phase purity of the synthesized MOF by comparing the diffraction pattern to a simulated one [18].

- Surface Area and Porosity Analysis (BET): Determines the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution through N₂ adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K [16] [18].

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Identifies the presence of specific functional groups (e.g., amines, carboxylates) within the MOF structure [18].

- Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): Provides visual information on the morphology, size, and shape of MOF crystals [18].

Adsorption Capacity and Kinetics Testing: These experiments measure the core performance metrics.

- Gravimetric Method: A widely used technique where a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) measures the change in mass of the MOF sample as it is exposed to a stream of CO₂ at a specific temperature and pressure. This directly quantifies the CO₂ uptake capacity [14].

- Volumetric Method: Uses equipment like a manometric gas sorption analyzer to measure gas adsorption by monitoring pressure changes in a calibrated volume. This method was used to measure binary (CO₂/H₂O) adsorption isotherms for UiO-66 [14].

- Kinetic Modeling: Experimental adsorption data is often fitted to models like the Elovich model (which describes chemisorption kinetics) and the Langmuir model (which assumes monolayer adsorption) to understand the adsorption mechanism and rate. A high coefficient of determination (R² > 0.95) indicates a good fit [18].

Selectivity and Stability Assessment: Critical for evaluating practical viability.

- Selectivity Measurement: CO₂/N₂ selectivity can be determined experimentally using:

- Binary Gas Mixture Experiments: Flowing a gas mixture (e.g., typical flue gas composition: 4% CO₂, 75% N₂, 9% H₂O) and measuring the adsorbed amounts of each component [14].

- Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST): A theoretical method commonly used to predict mixture adsorption equilibria and selectivity from single-component gas adsorption isotherms [16] [14].

- Cyclic Stability Testing: The MOF undergoes repeated cycles of CO₂ adsorption and regeneration (often by applying heat or vacuum). The retention of adsorption capacity over multiple cycles (e.g., 10 cycles as for IUST-4 [18]) is a key indicator of the material's durability and economic feasibility.

- Selectivity Measurement: CO₂/N₂ selectivity can be determined experimentally using:

Mechanisms of CO₂ Capture in MOFs

The enhanced performance of functionalized MOFs can be attributed to specific adsorption mechanisms, which are visualized below and detailed in the subsequent sections.

CO₂ Adsorption Mechanisms in MOFs

Physical Adsorption (Physisorption)

Physisorption relies on weak intermolecular forces and is often reversible with minimal energy input.

- Electrostatic Interactions: This is a key mechanism where the electric field within the MOF pore interacts with the quadrupole moment of the CO₂ molecule. For instance, in hydrated Cu-HKUST-1, water molecules coordinated to open metal sites generate an electric field that enhances CO₂ adsorption via dipole-quadrupole interactions [14].

- Van der Waals Forces and Kinetic Sieving: These are universal attractive forces that are stronger in MOFs with high surface areas and ultramicropores, whose size is comparable to that of a CO₂ molecule. This allows for the selective exclusion of larger N₂ molecules [16].

- Gating Effects: Some flexible MOFs possess dynamic frameworks that can undergo structural changes ("gate opening") in response to specific gas stimuli like CO₂, leading to highly selective adsorption [16].

Chemical Adsorption (Chemisorption)

Chemisorption involves the formation of stronger, often reversible, chemical bonds and is central to many functionalization strategies.

- Acid-Base Reaction: This is the primary mechanism in amine-functionalized MOFs. The basic amine groups (e.g., in grafted diamines) react with the acidic CO₂ molecule to form carbamate or bicarbonate species, providing high selectivity, though sometimes at the cost of slower kinetics [14].

- Coordination to Open Metal Sites (OMS): Unsaturated metal centers in the MOF nodes can act as strong, specific adsorption sites for CO₂ molecules. The strength of this interaction can be tuned by the choice of metal, as seen in the superior adsorption energy of heterometallic IUST-4 [16] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key materials and computational tools used in the research and development of functionalized MOFs for CO₂ capture.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MOF-based CO₂ Capture Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Serves as the metal node (inorganic building unit) for MOF synthesis. | Nitrates, chlorides, or acetates of Zn, Cu, Cd, Zr, etc. [18] [19] |

| Organic Linkers | Multitopic organic molecules that connect metal nodes to form the framework. | Carboxylates (e.g., OBA), azoles (e.g., imidazoles), nitrogen-containing ligands (e.g., DPTTZ) [18] [19] |

| Amine Functionalizers | Used in Post-Synthetic Modification to introduce CO₂ chemisorption sites. | Diamines like N,N'-dimethylethylenediamine [14] or TEPA for impregnation [16] |

| Solvents | Medium for MOF synthesis and modification. | Dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol, ethanol, water, acetonitrile [16] [18] |

| Computational Databases | For high-throughput screening and prediction of MOF properties. | Open DAC 2025 (ODAC25): Contains ~70 million DFT calculations on 15,000 MOFs for DAC [20] |

| Modulators | Chemicals used to control crystal growth and induce defects. | Monocarboxylic acids (e.g., formic acid, acetic acid) [14] |

| Gas Sorption Analyzer | Instrument for measuring gas adsorption capacity and textural properties. | Used for obtaining N₂ (77 K) and CO₂ (273-298 K) isotherms [16] [18] |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Instrument for measuring gas uptake (gravimetrically) and thermal stability. | Used for CO₂ capacity tests and assessing regeneration temperature [14] |

The strategic functionalization of MOFs—through methods such as amine grafting, heterometallic incorporation, and linker functionalization—significantly enhances their performance in CO₂ capture by improving capacity, selectivity, and kinetics beyond the capabilities of pristine MOFs. Experimental data confirms that tailored materials like IUST-4 and amine-impregnated MOF-177 can achieve substantially higher CO₂ uptake and stability. The advancement of large-scale computational datasets, such as the Open DAC 2025, coupled with robust experimental protocols, provides researchers with powerful tools for the rational design and discovery of next-generation MOF sorbents. As the field progresses, the focus will increasingly shift towards optimizing these materials for performance under realistic, humid conditions and reducing synthesis costs to enable widespread industrial deployment.

The escalating concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is a primary driver of climate change, necessitating the rapid development of efficient carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies [21]. Among the various strategies, adsorption using solid porous materials has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional amine-based liquid solvents, offering lower regeneration energy, enhanced moisture resistance, and a reduced environmental footprint [21] [22]. This guide provides an objective comparison of three principal classes of adsorbents—Zeolites, Activated Carbons, and Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)—focusing on their performance in CO2 capture. The content is framed within broader research on functionalized MOFs, which demonstrate how material tunability can enhance capture performance [5].

Comparative Performance of Adsorbent Material Classes

The performance of an ideal CO2 adsorbent is governed by a balance of properties, including high uptake capacity, selectivity, stability under operating conditions, and economic viability [21] [22]. The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of zeolites, activated carbons, and MOFs against these criteria.

Structural Properties and Material Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Properties and Characteristics

| Property | Zeolites | Activated Carbons | MOFs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Type | Crystalline aluminosilicates [21] | Amorphous carbon [21] | Hybrid crystalline materials with metal nodes & organic linkers [5] |

| Porosity | Microporous [21] | Microporous/Mesoporous [21] | Ultra-porous (up to 90% free volume) [23] |

| Primary CO2 Capture Mechanism | Electrostatic interactions, molecular sieving [24] | Physisorption [21] | Physisorption, chemisorption (if functionalized) [21] [5] |

| Tunability | Moderate (cation exchange, framework composition) [21] | Low (primarily through precursor selection & activation) [21] | Very High (via metal nodes, organic linkers, & post-synthetic modification) [5] [23] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimental CO2 Adsorption Performance and Key Metrics

| Performance Metric | Zeolites | Activated Carbons | MOFs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Area (m²/g) | 300 - 1,500 [21] [23] [25] | 400 - 2,500 [21] [23] | 1,500 - 7,000+ [21] [23] [25] |

| CO2 Adsorption Capacity (mmol/g) | 3.5 - 5.0 [21] | 3.3 - 5.0 [21] | 5.5 - 8.0 [21] |

| Relative Cost (USD/kg) | 2 - 10 [21] | 1 - 5 [21] | 100 - 500 [21] |

| Moisture Resistance | Low (hydrophilic, competes with CO2) [21] | High [21] | Variable; can be designed for high resistance [21] |

| Regeneration Ease | High (but may require high temperatures ~300°C) [23] [22] | High (low regeneration temperature ~100°C) [23] | Moderate to High (regeneration temperature ~100°C, but some may degrade) [21] [23] |

| Cyclic Stability | High [22] | High [22] | Moderate to High (dependent on functionalization and structure) [5] [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Adsorbent Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols are critical for the objective comparison of adsorbent materials. The following methodologies are commonly employed in research and development.

Material Synthesis and Functionalization

- MOF Synthesis (Solvothermal Method): This common method involves dissolving metal salt precursors (e.g., copper nitrate, zinc acetate) and organic ligands (e.g., terephthalic acid, imidazolates) in an organic solvent like N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF). The solution is heated in a Teflon-lined autoclave at a controlled temperature (e.g., 85-120°C) for several hours to several days to facilitate crystal growth [5].

- Amine Functionalization of MOFs: Amine grafting can be achieved via post-synthetic modification. The synthesized MOF is immersed in a solution containing an aminosilane compound, such as N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropylmethyldiethoxysilane. The mixture is stirred under an inert atmosphere at elevated temperatures (e.g., 60-80°C) for a set period, after which the solid is collected, washed, and vacuum-dried to yield the amine-functionalized MOF [5].

Material Characterization Techniques

- Surface Area and Porosity (BET Method): The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution are determined by measuring the quantity of nitrogen gas adsorbed at its boiling point (77 K) across a range of relative pressures. The data is analyzed using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory for surface area and density functional theory (DFT) for pore size distribution [21] [5].

- Crystallinity and Structure (X-ray Diffraction - XRD): Powder XRD (PXRD) is used to confirm the crystallinity and phase purity of the synthesized material. The sample is scanned with Cu Kα radiation, and the resulting diffraction pattern is compared against a simulated pattern from a known crystal structure to verify structural integrity [5].

- Thermal Stability (Thermogravimetric Analysis - TSA): The thermal stability and degradation profile of the adsorbent are assessed by heating a small sample (e.g., 10 mg) from room temperature to 800°C under a nitrogen or air atmosphere, while continuously measuring the weight loss [22].

CO2 Adsorption Performance Testing

- Adsorption Capacity Measurement: CO2 uptake is typically measured using a gravimetric or volumetric method. For a standard test, a known mass of degassed adsorbent is exposed to a pure CO2 stream or a CO2/N2 mixture at a specified temperature (e.g., 25°C) and pressure (e.g., 1 bar). The amount of CO2 adsorbed is recorded until equilibrium is reached [21] [22].

- Cyclic Adsorption-Desorption (Regeneration) Testing: The adsorbent's stability and regenerability are evaluated over multiple cycles. A common protocol involves adsorbing CO2 at 25-40°C and 1 bar, followed by desorption via Temperature Swing Adsorption (TSA) by heating to 100-120°C under a nitrogen purge, or via Vacuum Swing Adsorption (VSA) by reducing the pressure [22]. The adsorption capacity is tracked over dozens of cycles to assess durability.

- Selectivity Determination: Selectivity of CO2 over N2 can be estimated from single-gas adsorption isotherms using ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) or directly measured by conducting breakthrough experiments. In a breakthrough setup, a gas mixture (e.g., 15% CO2, 85% N2) is passed through a packed bed of adsorbent, and the composition of the effluent gas is monitored over time [26].

Performance Trade-offs and Decision Pathways

The selection of an optimal adsorbent involves navigating trade-offs between performance, stability, and cost. The following diagram synthesizes the key comparative findings from the data to outline a logical decision pathway for material selection.

Adsorbent Selection Pathway This decision pathway helps navigate the primary trade-offs between cost, capacity, and operational conditions when selecting a CO2 adsorbent.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Adsorbent Research and Testing

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Zeolite 13X-APG | A commercial alkali metal aluminosilicate with a FAU framework, widely used as a benchmark zeolite material for CO2 capture studies in VPSA processes [27]. |

| HKUST-1 (MOF-199) | A copper-based MOF featuring open metal sites; commonly used as a prototypical MOF to study CO2 adsorption and the effects of functionalization [5]. |

| Aminosilanes (e.g., AEAPDMS) | Organosilicon compounds containing an amine group; used for post-synthetic grafting to create amine-functionalized MOFs and silica materials, enhancing CO2 selectivity and stability [5]. |

| Terephthalic Acid | A common organic linker (ligand) used in the solvothermal synthesis of numerous MOFs, including MOF-5 and UiO-66 [5]. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | A polar aprotic solvent frequently used in the solvothermal synthesis of MOFs to dissolve metal salts and organic linkers [5]. |

| Simulated Flue Gas (e.g., 15% CO2, 85% N2) | A standard gas mixture used in laboratory settings to mimic the composition of post-combustion flue gas from power plants for realistic adsorption testing [22] [27]. |

Zeolites, activated carbons, and MOFs each present a distinct profile of advantages and limitations for CO2 capture. Zeolites offer low cost and high selectivity but are compromised by moisture. Activated carbons provide excellent moisture resistance and the lowest cost, though with generally lower selectivity. MOFs lead in uptake capacity and tunability but face challenges in cost and hydrothermal stability. The ongoing development of functionalized MOFs, particularly amine-grafted variants, aims to enhance performance in real-world conditions [5]. The optimal choice of adsorbent is not universal but depends heavily on the specific operational parameters, economic constraints, and environmental conditions of the intended application. Future research directions will likely focus on creating hybrid systems and scaling up synthesis to make high-performance materials like MOFs economically viable for widespread industrial deployment [21] [22].

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) represent a class of porous hybrid materials that have revolutionized the design of functional porous solids. Their defining structural advantages—ultrahigh surface areas and exceptional design flexibility—position them as superior materials for applications like CO₂ capture when compared to traditional alternatives such as zeolites and activated carbons. This guide objectively compares the performance of functionalized MOFs against these conventional materials, focusing on their application in CO₂ capture research.

Structural Fundamentals and Performance Advantages

The fundamental structure of MOFs, composed of metal ions or clusters connected by organic linkers, creates a highly porous and crystalline network [28] [29]. This architecture is the source of their unique properties.

- Ultrahigh Surface Area: The porous nature of MOFs results in an exceptionally high specific surface area, significantly greater than that of many traditional porous materials. This provides a vast interface for interactions with gas molecules like CO₂ [29] [30].

- Tunable Porosity: Unlike the fixed pore sizes of zeolites, the pore geometry and size in MOFs can be precisely controlled through careful selection of the metal clusters and organic linkers during synthesis. This allows for strategic design of pores optimized for specific molecular separations [28] [29].

- Design Flexibility and Functionalization: The organic linkers in MOFs can be readily modified with various functional groups (e.g., -NH₂, -OH, -Br). This enables post-synthetic fine-tuning of the chemical environment within the pores to enhance host-guest interactions, a level of customization not possible with most conventional materials [31] [29].

The following table summarizes a performance comparison between MOFs and traditional adsorbents for CO₂ capture.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MOFs vs. Traditional Adsorbents for CO₂ Capture

| Feature | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Zeolites | Activated Carbon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Surface Area (m²/g) | Up to 7,000 [30] | Moderate (Typically < 1000) | High (Typically 500-3,000) |

| Pore Tunability | Highly tunable in size and functionality [28] | Fixed, rigid pores | Limited control, broad pore distribution |

| CO₂ Adsorption Mechanism | Physisorption & Tailored Chemisorption [32] | Primarily physisorption/ion-exchange | Physisorption |

| Functionalization | High, via linker design and post-synthetic modification [31] | Limited | Limited |

| Selectivity Enhancement | Functionalization (e.g., -NH₂), open metal sites [32] | Cation exchange | Surface chemistry modification |

| Stability | Variable; some (e.g., UiO-66) exhibit high water/chemical stability [31] | High thermal and hydrothermal stability | High thermal stability, but combustible |

Experimental Data and Performance in CO₂ Capture

The theoretical advantages of MOFs translate into measurable performance benefits. Research has shown that specific functionalizations can drastically alter both the dynamic properties and the gas uptake capabilities of MOFs.

Table 2: Impact of Functional Groups on UiO-66 Series for CO₂ Capture

| Functional Group (X) | Dynamic Property (FWHM Å)* | Influence on CO₂ Uptake | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| -H | Baseline | Baseline | Static electronic effects, pore size |

| -NH₂ | 2.01 Å (More rigid) | Increased [31] | Combined static electronic and restricted dynamic effects |

| -Br | 4.02 Å (More flexible) | Decreased [31] | Dynamic rotation properties of the linker |

| -OH / -CH₃ | Intermediate | Varies | Polarity and functional group size |

*FWHM (Full Width at Half Maximum): A measure of the benzene ring rotational flexibility in the linker, with a lower value indicating greater local rigidity [31].

The data demonstrates that introducing an amino group (-NH₂) not only changes the chemical environment but also restricts the rotation of the organic linker, enhancing local rigidity. This correlated with higher CO₂ uptake, indicating that functionalization can influence gas capture through both static electronic effects and dynamic structural properties [31].

Furthermore, incorporating MOFs into composite materials, such as with polymers, can enhance their stability and mitigate issues like premature gas or drug release, making them more viable for industrial applications [29].

Key Experimental Protocols for MOF Evaluation

To obtain the performance data cited in this guide, researchers employ a suite of standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines the key stages from material synthesis to performance evaluation.

Diagram Title: MOF Research Workflow

Synthesis and Functionalization

MOFs can be synthesized through various methods, including conventional solvothermal/hydrothermal reactions, as well as contemporary approaches like microwave-assisted, electrochemical, and mechanochemical synthesis [33] [28]. For CO₂ capture, a common functionalization strategy is amine-grafting, where MOFs are treated with amine-containing compounds to introduce sites for strong, selective chemisorption of CO₂ [32].

Characterization Techniques

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Used to confirm the successful formation of the desired crystalline MOF structure and its stability after functionalization or testing [33].

- Surface Area and Porosity Analysis (BET): Measures the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution using nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77K [33].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Assesses the thermal stability of the MOF by measuring weight changes as a function of temperature in a controlled atmosphere [33].

- Integrated Differential Phase Contrast STEM (iDPC-STEM): An advanced electron microscopy technique that allows direct, real-space imaging of both metal nodes and organic linkers. It can be used to visualize the dynamic behavior of linkers, such as the rotation of benzene rings, and how it is influenced by functional groups [31].

Performance Testing for CO₂ Capture

- Gas Sorption Isotherms: CO₂ adsorption capacity is typically measured using volumetric or gravimetric sorption analyzers. Isotherms are collected at relevant temperatures (e.g., 0°C for pre-combustion, 25-50°C for post-combustion capture) and pressures (e.g., 1 bar for flue gas conditions, up to 30 bar for pure CO₂ or storage) [32].

- Cyclic Stability and Regeneration: The adsorbent is subjected to multiple adsorption-desorption cycles (e.g., using pressure or temperature swings) to evaluate the long-term stability and regenerability of the material, which is critical for economic viability [32] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for MOF CO₂ Capture Research

| Item | Function in Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Forms the inorganic "nodes" of the MOF structure. | Metal salts (e.g., ZrCl₄ for UiO-66, Zn(NO₃)₂ for ZIF-8) [28]. |

| Organic Linkers | Connects metal nodes to form the porous framework. | p-benzenedicarboxylic acid (BDC); BDC-X for functionalized UiO-66 (X = -NH₂, -Br, etc.) [31]. |

| Functionalization Agents | Post-synthetically modifies the MOF to enhance CO₂ affinity. | Amine compounds (e.g., ethylenediamine) for grafting [32]. |

| Solvents | Medium for MOF synthesis and processing. | Dimethylformamide (DMF), water, methanol [33]. |

| Reference Adsorbents | Benchmark for performance comparison. | Zeolite 13X, Activated Carbon [32]. |

| Analysis Gases | For adsorption capacity and selectivity tests. | High-purity CO₂, N₂, and their mixtures to simulate flue gas [32]. |

Synthesis Techniques and Functionalization Strategies for Enhanced CO2 Capture

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) represent a class of crystalline porous materials composed of metal ions or clusters connected by organic bridging ligands. Their structural diversity, exceptional porosity, and vast surface areas (up to 7000 m²/g) have positioned them as promising materials for numerous applications, particularly carbon dioxide capture [16] [30]. The performance of MOFs in adsorbing CO₂ is intrinsically linked to their synthesis method, which governs critical characteristics such as specific surface area, pore architecture, crystallinity, and the presence of structural defects or functional groups [5].

Traditionally, MOFs have been synthesized via energy-intensive solvothermal methods. However, the field is increasingly shifting toward sustainable synthesis pathways that reduce environmental impact and operational costs while maintaining, or even enhancing, material performance [33]. This review provides a objective comparison of contemporary MOF synthesis techniques, evaluating their influence on the structural properties and CO₂ adsorption efficacy of the resulting frameworks. A particular focus is placed on the transition from conventional solvothermal methods to greener alternatives, analyzing how these different synthesis pathways tailor MOFs for optimal performance in carbon capture applications.

Conventional and Contemporary Synthesis Methods

The synthesis of MOFs has evolved from classic solvothermal methods to a range of contemporary techniques that offer improved efficiency, scalability, and environmental compatibility. The formation and final characteristics of MOFs are heavily influenced by experimental parameters such as reaction temperature, duration, and solution pH [16].

Conventional Solvothermal Synthesis

Solvothermal synthesis is one of the most historically prevalent methods for MOF production. This process typically involves dissolving metal precursors and organic linkers in a high-boiling-point organic solvent, most commonly N,N'-Dimethylformamide (DMF). The reaction mixture is heated in a sealed autoclave at elevated temperatures (often between 100-130°C) for periods ranging from hours to days, generating autogenous pressure [34]. For example, a standard protocol for synthesizing MOF-801 solvothermally involves dissolving fumaric acid and zirconium oxychloride in a solvent mixture of DMF and formic acid, then heating at 130°C for 10 hours [34]. The main drawbacks of this method include the use of hazardous solvents, high energy consumption, and lengthy reaction times, which pose challenges for scalability and environmental sustainability [35].

Contemporary Green Synthesis Methods

In response to the limitations of conventional methods, several greener synthesis strategies have been developed. These approaches aim to reduce or eliminate toxic solvents, lower energy requirements, and shorten reaction times.

Green Room Temperature Synthesis: This method utilizes water as a benign solvent and proceeds at ambient conditions. The synthesis of MOF-801, for instance, can be achieved by dissolving zirconium oxychloride and fumaric acid in a water/formic acid mixed solvent and stirring at room temperature for 90 minutes, followed by a 48-hour crystallization period [34]. This approach completely avoids high temperatures and toxic solvents.

Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: This technique uses microwave radiation to heat the reaction mixture uniformly and rapidly. It significantly reduces synthesis time from days to minutes or hours while promoting the formation of small, uniform crystals due to instantaneous nucleation [33].

Mechanochemical Synthesis: This solvent-free or solvent-less method relies on mechanical grinding to initiate chemical reactions between solid precursors. It is highly sustainable, as it minimizes waste and eliminates the need for solvent removal and purification [33].

Electrochemical Synthesis: This method involves applying an electrical current to a reaction mixture containing metal electrodes and organic linkers. It allows for continuous MOF production and better control over reaction kinetics, making it suitable for industrial scale-up [33].

Sonochemical Synthesis: Utilizing ultrasound energy, this method creates localized hot spots of high temperature and pressure, which accelerate nucleation and reduce crystal size. This leads to faster reaction rates and the formation of nanoparticles with high purity [33].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflows for solvothermal versus green synthesis pathways, highlighting key differences in their operational parameters and the characteristics of the resulting MOF materials.

Experimental Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The choice of synthesis method profoundly impacts the physical and chemical properties of MOFs, which in turn dictate their performance in CO₂ capture applications. Comparative studies provide quantitative data to evaluate these relationships.

Case Study: MOF-801 Synthesis and Water Adsorption Performance

A direct comparative study of MOF-801 synthesized via solvothermal (SS-MOF-801) and green room-temperature (GS-MOF-801) methods revealed significant differences in material characteristics and performance [34].

Table 1: Characteristics of MOF-801 Synthesized via Different Methods

| Property | Solvothermal Synthesis (SS-MOF-801) | Green Room-Temperature Synthesis (GS-MOF-801) |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Surface Area | 365 m²/g | 691 m²/g |

| Maximum Water Adsorption Capacity (25°C, 80% RH) | 36.7 g/100 g | 41.1 g/100 g |

| Adsorption at Low Humidity (25°C, 30% RH) | ~28 g/100 g (estimated) | 31.5 g/100 g |

| Crystallite Size | Larger crystals | ~66 nm |

| Key Advantage | High crystallinity | 89% higher surface area, superior adsorption capacity |

This study demonstrates that green synthesis can yield MOFs with markedly improved textural properties. The GS-MOF-801 exhibited an 89% higher specific surface area and a 12% greater maximum water adsorption capacity compared to its solvothermal counterpart [34]. The authors attributed this enhancement to the material's smaller crystal size, greater hydrophilicity, and a potentially higher concentration of defects, which create more adsorption sites [34].

The Critical Role of Functionalization in CO2 Capture

While synthesis method dictates the framework's physical structure, post-synthetic functionalization is often the key to achieving high CO₂ adsorption capacity and selectivity. This is particularly true for incorporating nitrogen-containing groups, such as amines, which strongly interact with CO₂ molecules.

Unmodified MOFs often exhibit insufficient CO₂ capture performance for practical applications. For instance, unmodified MOF-177 has a CO₂ uptake of only 1.18 mmol·g⁻¹ at 1 bar and 298 K. In contrast, after impregnation with tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA), its capacity rises dramatically to 3.8 mmol·g⁻¹ under identical conditions [16]. Functional groups can be incorporated via two primary strategies:

- Direct Synthesis: Using pre-functionalized organic linkers during the initial synthesis.

- Post-Synthetic Modification (PSM): Utilizing coordinatively unsaturated metal sites or structural defects to graft functional groups onto a pre-formed framework [16].

Common functional groups for CO₂ capture include -NO₂, -OH, -COOH, and -SO₃H, with amine-functionalization being particularly effective due to its strong chemical affinity for CO₂ [16] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Synthesis Methods for MOFs in Environmental Applications

| Synthesis Method | Key Features | Advantages | Disadvantages | Impact on CO2 Capture Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvothermal | High-boiling solvents (e.g., DMF), sealed autoclave, high T/P. | High crystallinity, well-defined pores. | High energy use, toxic solvents, slow. | Provides baseline framework; often requires post-functionalization for high capacity. |

| Green (Room Temp/Aqueous) | Water/ethanol solvent, ambient T/P. | Low cost, safe, scalable, sustainable. | May have less crystalline control. | Can create defects/smaller crystals that increase surface area and access to active sites. |

| Microwave-Assisted | Dielectric heating, rapid energy transfer. | Very fast, uniform nucleation, small crystals. | Potential for hot spots, scale-up challenges. | Rapid synthesis of uniform nanoparticles with high surface-to-volume ratio. |

| Mechanochemical | Grinding solid precursors, minimal solvent. | Solvent-free, low waste, simple. | Potential for amorphous phases. | Enables direct integration of functional groups during synthesis. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Characterization for MOF Synthesis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The synthesis and functionalization of MOFs require a specific set of chemical reagents and materials. The table below details key components and their functions in the synthesis process.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MOF Synthesis and Functionalization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions or clusters (Secondary Building Units - SBUs). | Zirconium oxychloride (ZrOCl₂·8H₂O) for Zr-based MOFs like MOF-801 [34]. |

| Organic Linkers | Multifunctional molecules that connect metal nodes to form the framework. | Fumaric acid as a linker in MOF-801; terephthalic acid in many other MOFs [34]. |

| High-Boiling Solvents | Reaction medium for solvothermal synthesis. | N,N'-Dimethylformamide (DMF), N,N'-Diethylformamide (DEF) [34]. |

| Green Solvents | Sustainable reaction medium for green synthesis. | Water, ethanol, methanol [35] [34]. |

| Modulators | Chemicals that control crystal growth and morphology. | Formic acid, acetic acid, monovalent anions [34]. |

| Amine Functionalizing Agents | Imparts strong CO₂ chemisorption sites via post-synthetic modification. | Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA), polyethyleneimine (PEI) [16] [5]. |

Essential Characterization Techniques

To correlate synthesis methods with CO₂ capture performance, comprehensive characterization is essential. Key techniques include:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines the crystallinity, phase purity, and structural integrity of the synthesized MOF. Both single-crystal (SCXRD) and powder (PXRD) methods are used, with PXRD being standard for rapid phase identification [5] [33].

- Nitrogen Physisorption: Measures the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution at liquid nitrogen temperature. This is critical as high surface area and tailored pore architecture are directly linked to enhanced gas adsorption capacity [5] [34].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Assesses the thermal stability of the framework and determines the optimal temperature for activating the material (removing solvent) without degrading its structure [33] [34].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies the presence of specific functional groups and chemical bonds within the MOF, confirming successful linker incorporation and functionalization [34].

The synthesis of metal-organic frameworks has progressively expanded from traditional, energy-intensive solvothermal methods to a diverse toolkit of contemporary, greener techniques. Evidence indicates that sustainable methods, such as room-temperature aqueous synthesis, can not only reduce environmental impact but also produce MOFs with superior textural properties, such as higher surface area and enhanced adsorption capacity, as demonstrated by the case of MOF-801 [34].

For the specific application of CO₂ capture, the synthesis method provides the foundational porous scaffold, but post-synthetic functionalization—particularly with amines—is often the decisive factor for achieving high performance. The future of MOF synthesis lies in optimizing these green pathways for industrial scalability, which is crucial for commercial applications like carbon capture, where the MOF market is expected to grow significantly [30]. Future research should focus on integrating functional groups directly during green synthesis and further exploring the relationship between synthesis-induced defects and gas adsorption mechanisms to design next-generation, high-performance MOFs for a sustainable future.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as promising nanomaterials for effective CO₂ capture due to their high surface area, highly porous and diverse structures, and ease of modification. [5] Among various modification strategies, amine functionalization has proven particularly effective for enhancing CO₂ affinity and selectivity. This approach involves incorporating amine groups (-NH₂) into MOF structures, significantly improving their performance in carbon capture applications, especially under realistic conditions involving flue gas and humidity. [36] [37]

The exceptional capability of amine-functionalized MOFs stems from the strong interactions between basic amine sites and acidic CO₂ molecules, which can occur through physisorption, chemisorption, or cooperative mechanisms. [37] This review provides a comprehensive comparison of amine-functionalized MOFs, examining their synthesis methodologies, performance metrics under varying conditions, and potential for commercial deployment in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies.

Synthesis Techniques and Functionalization Methods

Direct Synthesis Approaches

Direct synthesis incorporates amine-functionalized ligands during MOF construction, ensuring homogeneous distribution of amine sites throughout the framework. This method typically employs solvothermal techniques, combining amine-based ligands with metal sources in organic solvents like DMF, followed by heating in Teflon-lined autoclaves. [5] For instance, HKUST-1–NH₂ and MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂ have been successfully synthesized using 2-aminoterephthalic acid as an organic linker via hydrothermal methods without adding hydrofluoric acid. [38]

The mixed-linker strategy represents another effective direct synthesis approach, blending non-amine and amine-functionalized ligands in precise ratios. Research on Ti-based MOFs (MIP-207) demonstrated that replacing portions of the H₃BTC ligand with 5-aminoisophthalic acid (5-NH₂-H₂IPA) produced MIP-207-NH₂ materials with maintained structural integrity when the mole ratio of H₃BTC to 5-NH₂-H₂IPA was less than 1:1. [39] This method allows precise control over amine loading while preserving the parent MOF's structural characteristics.

Post-Synthetic Modification

Post-synthetic modification involves grafting amine molecules onto pre-synthesized MOFs, often through impregnation techniques. This method is particularly valuable for introducing amines into MOFs that cannot sustain direct synthesis conditions. MIL-100(Cr) has been successfully modified with polyethyleneimine (PEI), tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA), and diethanolamine (DEA) via impregnation, significantly enhancing CO₂ capture performance under direct air capture conditions. [40]

Another post-synthetic approach involves grafting alkylamine molecules onto unsaturated metal sites. Studies on M₂(dobdc) and its expanded version M₂(dobpdc) have shown that functionalization with alkyldiamines creates ammonium carbamate chains through cooperative chemi-physisorption mechanisms, resulting in step-shaped adsorption isotherms ideal for carbon capture applications. [37]

Table 1: Comparison of Amine Functionalization Methods for MOFs

| Functionalization Method | Key Characteristics | Representative MOFs | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Synthesis | Amine groups incorporated via functionalized ligands during MOF assembly | HKUST-1–NH₂, MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂, MIP-207-NH₂ series | Homogeneous amine distribution; preserved crystallinity | Limited by ligand compatibility; may alter framework topology |

| Post-Synthetic Impregnation | Amine compounds physically loaded into MOF pores | PEI-MIL-100(Cr), TEPA-MIL-101 | High amine loading; applicable to various MOFs | Potential pore blockage; may reduce surface area |

| Post-Synthetic Grafting | Amine molecules chemically bonded to unsaturated metal sites | mmen-Mg₂(dobpdc), en-Mg-MOF-74 | Strong amine-framework bonds; cooperative adsorption | Requires specific open metal sites; complex synthesis |

Performance Comparison of Amine-Functionalized MOFs

CO₂ Uptake Capacities

Amine functionalization significantly enhances CO₂ uptake capacities across various MOF families, particularly at low pressures and ambient conditions relevant to post-combustion carbon capture. Experimental data demonstrate substantial improvements compared to their non-functionalized counterparts:

MIP-207-NH₂-25% exhibits CO₂ capture performance of 3.96 mmol g⁻¹ at 0°C and 2.91 mmol g⁻¹ at 25°C, representing increases of 20.7% and 43.3%, respectively, compared to unmodified MIP-207. [39] Breakthrough experiments further confirmed that the dynamic CO₂ adsorption capacity and CO₂/N₂ separation factors of MIP-207-NH₂-25% increased by approximately 25% and 15%, respectively. [39]

PEI-modified MIL-100(Cr) achieves a CO₂ uptake of 1.21 mmol g⁻¹ under direct air capture conditions while maintaining over 90% of its initial capacity after 20 cycles. [40] Under humid conditions, the CO₂ adsorption performance of these solid amine materials further improves due to enhanced utilization of amine sites, particularly increased accessibility of secondary amines. [40]

Molecular simulation studies provide additional insights, showing that mmen-Mg₂(dobpdc) exhibits high cyclic working capacities ideal for temperature swing adsorption processes, with superior CO₂ uptake and regenerability for flue gas mixtures. [37] Importantly, these studies also reveal that more amine functional groups grafted onto MOFs and/or full functionalization of metal centers do not necessarily lead to better CO₂ separation capabilities due to steric hindrances. [37]

Table 2: Comparative CO₂ Adsorption Performance of Selected Amine-Functionalized MOFs

| MOF Material | Functionalization Method | CO₂ Capacity (mmol/g) | Conditions | Selectivity | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-207-NH₂-25% | Mixed linker | 2.91 | 25°C, 1 bar | Significantly enhanced CO₂/N₂ | Maintained after multiple cycles |

| HKUST-1–NH₂ | Direct synthesis | Improved uptake | Not specified | Enhanced | Excellent over 10 cycles |

| MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂ | Direct synthesis | Improved uptake | Not specified | Enhanced | Excellent over 10 cycles |

| Cr-50%PEI | PEI impregnation | 1.21 | DAC conditions | High | >90% capacity after 20 cycles |

| mmen-Mg₂(dobpdc) | Diamine grafting | High | Flue gas conditions | Ultrahigh (up to 230) | Good regenerability |

Selectivity and Stability

Beyond adsorption capacity, amine functionalization significantly enhances CO₂ selectivity against competing gases like N₂ and CH₄, a critical parameter for practical applications. Amine-functionalized MIL-101(Cr) demonstrates dramatically increased CO₂/N₂ selectivity, with PEI-impregnated MIL-101 achieving selectivities up to 1,200 at 50°C, and alkylamine-tethered MIL-101 reaching selectivities of 346. [37] Similarly, mmen-Cu-BTTri and diamine-grafted Mg₂(dobpdc) exhibit high selectivities of 327 and up to 230, respectively, under post-combustion conditions. [37]

Stability under practical operating conditions represents another crucial advantage of amine-functionalized MOFs. HKUST-1–NH₂ and MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂ not only show improved CO₂ uptake capability but also excellent and stable regenerability over multiple adsorption-desorption cycles. [38] PEI-modified MIL-100(Cr) exhibits strong coordination and high oxidative stability compared to TEPA-modified adsorbents, making it particularly suitable for direct air capture applications where oxidative degradation is a concern. [40]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis Protocols

Direct Synthesis of Amine-Functionalized MOFs: The hydrothermal method for synthesizing amine-functionalized MOFs like HKUST-1–NH₂ and MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂ typically involves dissolving metal precursors (copper nitrate for HKUST-1 or chromium salts for MIL-101) and 2-aminoterephthalic acid in deionized water. [38] The mixture is transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 100-120°C for 12-24 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the crystalline product is collected by filtration, washed with solvents like DMF and methanol to remove unreacted species, and activated under vacuum at elevated temperatures (typically 150°C) to remove solvent molecules from the pores. [38]

Post-Synthetic Impregnation: For amine impregnation, the pristine MOF (e.g., MIL-100(Cr)) is first activated under vacuum to remove any adsorbed species. [40] Separately, the amine compound (PEI, TEPA, or DEA) is dissolved in an appropriate solvent such as methanol. The activated MOF is then added to the amine solution and stirred for several hours to ensure thorough impregnation. The resulting solid is collected by filtration, washed with fresh solvent to remove surface-adsorbed amines, and dried under vacuum. The amine loading can be controlled by adjusting the concentration of the amine solution and the impregnation time. [40]

Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization is essential for verifying successful amine functionalization and understanding structure-performance relationships:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD) determines the crystallinity, phase purity, and structural integrity of amine-functionalized MOFs. Both single-crystal and powder XRD are employed, with the latter particularly useful for monitoring structural changes during functionalization. [5]

- N₂ Physisorption at -196°C measures surface area and porosity using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method, revealing how amine incorporation affects textural properties. [39]

- Elemental Analysis accurately determines the percentage content of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen, providing quantitative data on amine loading. [39]

- Scanning Electron Microscopy visualizes morphological changes after amine functionalization. [39]

- Thermogravimetric Analysis assesses thermal stability and determines optimal activation conditions. [39]

Adsorption Testing Protocols

Static Adsorption Measurements: CO₂ adsorption isotherms are typically measured using commercially available gas adsorption analyzers (e.g., Quantachrome Autosorb-iQ). [39] Prior to measurements, samples are degassed under vacuum at 150°C for 8 hours to remove adsorbed species. Isotherms are collected at relevant temperatures (0°C and 25°C) using temperature-controlled baths. Data is collected across a pressure range up to 1 bar to assess low-pressure capture performance. [39]

Dynamic Breakthrough Experiments: Breakthrough tests provide more realistic performance evaluation under flowing conditions. These experiments utilize a packed-bed reactor system where the adsorbent is packed into a column. [39] Gas mixtures simulating flue gas (typically 15% CO₂, 85% N₂) or other relevant compositions are passed through the bed at controlled flow rates. Effluent concentrations are monitored using gas analyzers or mass spectrometers. The breakthrough curve provides data on dynamic adsorption capacity and selectivity under practical conditions. [39]

Cyclic Stability Testing: Long-term stability is assessed through repeated adsorption-desorption cycles. Typically, adsorption is conducted at lower temperatures (25-35°C), followed by regeneration at elevated temperatures (100-150°C) under nitrogen flow or vacuum. [40] Capacity retention after multiple cycles indicates the material's practical viability and regeneration energy requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Amine-Functionalized MOF Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Aminoterephthalic Acid | Amine-functionalized linker for direct synthesis | HKUST-1–NH₂, MIL-101(Cr)–NH₂ synthesis [38] |

| 5-Aminoisophthalic Acid (5-NH₂-H₂IPA) | Mixed linker for amine functionalization | MIP-207-NH₂ series [39] |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Amine source for post-synthetic impregnation | MIL-100(Cr) modification [40] |

| N,N'-dimethylethylenediamine (mmen) | Diamine for grafting to open metal sites | mmen-Mg₂(dobpdc) functionalization [37] |

| Ethylenediamine (en) | Short-chain diamine for grafting | en-Mg-MOF-74 modification [37] |

| Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) | Branched polyamine for impregnation | MIL-100(Cr) modification [40] |

Computational Studies and Performance Prediction

Computational approaches have become indispensable tools for screening and optimizing amine-functionalized MOFs, complementing experimental studies. Molecular simulations can accurately predict CO₂ separation potentials, providing molecular-level insights that may not be accessible experimentally. [41] [37]

Large-scale computational screening of MOF databases has identified key structural parameters correlating with high CO₂ separation performance. Studies suggest that MOFs with optimal performance for CO₂ separation from flue gas and landfill gas typically exhibit isosteric heats of adsorption (ΔQst⁰) > 30 kJ/mol, pore-limiting diameters between 3.8-5 Å, largest cavity diameters between 5-7.5 Å, porosities (ϕ) between 0.5-0.75, surface areas < 1000 m²/g, and densities > 1 g/cm³. [41]