From Molecule to Medicine: A PSPP Framework for Accelerating Drug Development

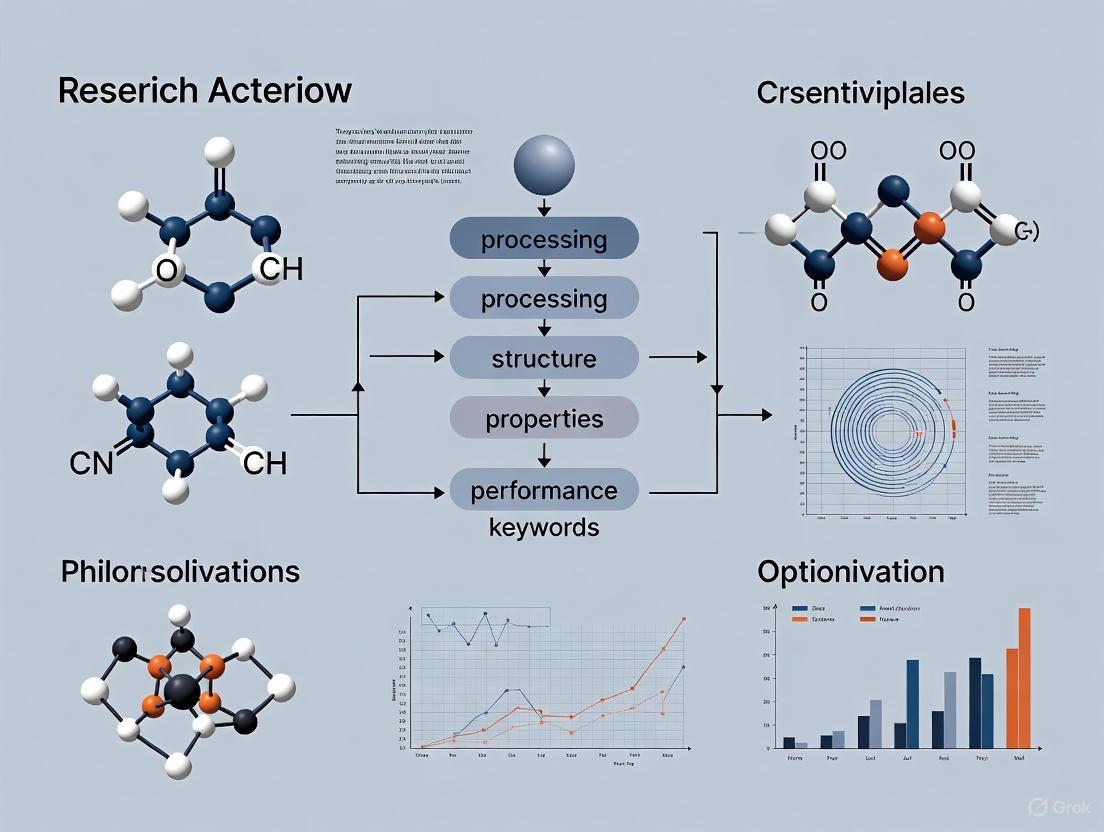

This article explores the critical role of the Process-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) framework in modern drug development.

From Molecule to Medicine: A PSPP Framework for Accelerating Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of the Process-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) framework in modern drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how this established materials science paradigm is being adapted to optimize pharmaceutical pipelines. The content spans from foundational PSPP principles and their application in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) to advanced data-driven modeling for troubleshooting and the validation required for regulatory success. By synthesizing these elements, the article provides a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging quantitative PSPP relationships to enhance efficacy, safety, and efficiency from early discovery to post-market surveillance.

The PSPP Paradigm: A Foundational Framework for Modern Drug Development

The Process-Structure-Property-Performance (PSPP) framework is a foundational paradigm in materials science that establishes a critical chain of causality from how a material is made, to its internal architecture, its measurable characteristics, and its ultimate effectiveness in a real-world application [1] [2] [3]. This systematic approach provides researchers with a structured methodology for designing and optimizing new materials, as the processing conditions dictate the material's internal structure, which in turn governs its intrinsic properties, ultimately determining its performance in a specific operating environment [3]. Understanding these interrelationships is essential for inverse design, where target performance requirements guide the selection of optimal properties, structures, and processing routes.

This framework's utility extends far beyond traditional metallurgy or polymer science. It offers a powerful lens for analyzing complex, multi-stage challenges in other fields, such as pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) [4]. In drug development, the "process" can be equated with drug discovery and manufacturing protocols, the "structure" with the drug's chemical and formulation composition, the "properties" with its efficacy and safety profile, and the "performance" with its therapeutic success and market viability [4]. This whitepaper will dissect the PSPP framework's application in two distinct domains—advanced materials and pharmaceutical pipelines—to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a unified perspective on optimizing complex research and development endeavors.

PSPP in Materials Science and Engineering

Foundational Principles and Application

In materials science, the PSPP framework is not merely a conceptual model but a practical guide for research and development. The "process" involves synthesis and fabrication techniques such as 3D printing, solvent casting, or hot-pressing [1] [2]. These methods directly create the material's internal "structure," including features like crystallinity, porosity, and particle distribution [2] [3]. The structure then manifests in observable "properties"—mechanical (strength, elasticity), thermal (conductivity, stability), magnetic (responsiveness, anisotropy), and degradation behavior [1] [2]. Finally, these properties collectively determine the material's "performance" in its intended application, whether it's a biodegradable implant, a precision sensor, or an environmental robot [1].

The following workflow illustrates the causal relationships and key feedback mechanisms within the PSPP framework for materials design:

Case Study: Magnetic Polymer Composites for Robotics

The development of magnetically responsive polymer composites (MPCs) for untethered miniaturized robotics offers a compelling case study of the PSPP framework in action [1]. In this advanced application, the precise control of each PSPP element is critical for achieving targeted and high-precision actuation.

Processing: MPCs are fabricated using techniques like 3D printing, photolithography, and replica molding [1]. A key consideration during processing is the thermal stability of both polymer matrices and magnetic fillers. Temperatures exceeding a polymer's thermal degradation temperature (Td) can cause defects, while processing above the Curie temperature (Tcurie) of magnetic fillers can erase pre-programmed magnetization profiles, directly impacting the final robot's functionality [1].

Structure: The processing method dictates the composite's internal architecture, specifically the distribution and alignment of magnetic particles (e.g., NdFeB microflakes, Fe3O4 nanospheres) within the polymer matrix [1]. Magnetic fields can be applied during processing to create directional particle assemblies, enhancing magnetic anisotropy, which is a crucial structural feature for controlled locomotion [1].

Properties: The composite's structure directly defines its actuation properties. A uniform particle distribution ensures consistent magnetization, while anisotropic structures create directional magnetic responsiveness. The resulting properties include magnetic torque generation, bending stiffness, and spontaneous magnetic responsiveness (magnetization), enabling actuation at low external magnetic field strengths (<100 mT) [1].

Performance: These properties culminate in the robot's operational performance, enabling diverse locomotion modes such as crawling, rolling, undulating, and corkscrew-like propulsion [1]. This performance is leveraged in applications like targeted drug delivery, microfluidic control, and microplastic removal, where precise movement in confined spaces is paramount [1].

Table 1: PSPP Relationships in Magnetic Polymer Composites for Robotics

| PSPP Element | Key Considerations | Impact on Next Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Process | 3D printing, solvent casting, application of magnetic fields during curing, thermal control (Tg, Tm, Td, Tcurie) [1] | Determines homogeneity and alignment of magnetic fillers within the polymer matrix. |

| Structure | Magnetic particle distribution (uniform vs. anisotropic), polymer chain orientation, porosity [1] | Governs the degree and directionality of magnetic responsiveness and mechanical integrity. |

| Property | Magnetic anisotropy, torque generation, bending stiffness, magnetization strength [1] | Dictates the type and efficiency of actuation (e.g., rolling, crawling) under external magnetic fields. |

| Performance | Targeted drug delivery, precision polishing, pollutant removal, locomotion in confined spaces [1] | The ultimate application success, driven by the effective integration of previous stages. |

Case Study: Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Biopolymers

The PSPP framework is equally critical in the design of sustainable materials, such as polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolymers. PHAs are bio-derived, biodegradable polyesters investigated as alternatives to conventional plastics [2].

Processing: PHAs are biosynthesized by microbes under specific fermentation conditions [2]. Downstream processing, including extraction and thermoforming (e.g., injection molding, extrusion), is influenced by their relatively narrow thermal processing windows [2].

Structure: The specific PHA copolymer structure (e.g., PHB, PHBV, PHBHHx) and its resulting crystallinity, molecular weight, and monomer composition are determined by the biosynthetic pathway and processing history [2].

Properties: The structural attributes dictate key material properties, including mechanical strength, brittleness, biodegradation rate, and biocompatibility [2]. The limited chemical diversity of commercially available PHAs currently restricts the accessible range of these properties [2].

Performance: The properties determine the material's suitability for applications such as compostable packaging, medical implants, and agricultural films [2]. A major performance challenge is achieving degradation rates and mechanical properties comparable to less expensive biopolymers like polylactic acid (PLA) [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Data for Common PHA Biopolymers [2]

| PHA Type | Approximate Cost (USD/lb) | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHB (P3HB) | $1.81 - $3.20 | High crystallinity, brittle, biocompatible | Basic packaging, specialty medical devices |

| PHBV (P3HB3HV) | Higher than PHB | Reduced brittleness, tunable degradation | Films, containers, drug delivery matrices |

| PHBHHx | Higher than PHB | Improved flexibility and toughness | Flexible packaging, advanced medical implants |

Experimental Protocols in Materials Science

Adhering to standardized experimental protocols is vital for establishing robust PSPP relationships. The following methodologies are commonly employed:

Protocol for Characterizing Magnetic Polymer Composites [1]:

- Fabrication: Prepare composites using a chosen method (e.g., DIW 3D printing). Apply a magnetic field during the curing process to induce magnetic anisotropy in the fillers.

- Structural Analysis: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to analyze the dispersion and alignment of magnetic particles within the polymer matrix.

- Property Measurement: Employ a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) to measure magnetic hysteresis and quantify magnetic properties like saturation magnetization and coercivity.

- Performance Testing: Actuate the fabricated robot in a controlled fluid environment using a Helmholtz coil system to apply programmable magnetic fields. Quantify locomotion efficiency (velocity, precision) via high-speed camera tracking.

Protocol for Analyzing PHA Biopolymers [2]:

- Processing/Biosynthesis: Biosynthesize PHA polymers in a bioreactor using engineered microbial strains (e.g., Cupriavidus necator) and specific carbon feedstocks.

- Structural Characterization: Use techniques like Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) for monomer composition. Determine crystallinity via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

- Property Testing: Perform tensile tests (ASTM D638) to determine mechanical properties. Assess biodegradation through enzymatic hydrolysis or controlled soil burial tests, monitoring mass loss over time.

- Performance Evaluation: Test the material in the target application (e.g., mechanical performance of a molded package, biocompatibility and degradation rate of a tissue engineering scaffold in vitro).

PSPP in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Mapping the PSPP Framework onto Drug Development

The pharmaceutical R&D pipeline can be effectively analyzed through the PSPP framework, translating its principles from materials to medicine. This perspective helps deconstruct the complex, high-attrition journey of drug development [4].

Process: This encompasses the entire drug discovery and development workflow, including target identification, lead compound optimization, preclinical studies, clinical trial execution (Phases I-III), and manufacturing process development [4]. The efficiency of this process is a major determinant of overall R&D productivity.

Structure: In the pharmaceutical context, "structure" refers to the chemical structure of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and the formulation design of the final drug product (e.g., tablet, injectable). This includes excipients and delivery mechanisms.

Property: The structure dictates the drug's critical quality properties, which include bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy (potency), safety (toxicity) profile, pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion), and chemical stability [4].

Performance: This is the ultimate measure of a drug's success in the real world, encompassing clinical trial outcomes, regulatory approval, real-world therapeutic success, market adoption, and commercial viability [4]. It also includes post-market performance regarding safety and its impact on public health.

The following diagram maps the PSPP framework onto the key stages of the pharmaceutical R&D pipeline:

Quantitative Analysis of the Pharmaceutical Pipeline

The pharmaceutical industry faces severe PSPP-related challenges, characterized by soaring costs, prolonged timelines, and high failure rates, which threaten its traditional R&D model [4].

- Soaring Costs and Diminishing Returns: The cost of bringing a new drug to market is estimated at $2.229 billion to $2.6 billion in 2024. Concurrently, R&D margins are projected to decline from 29% to 21% of total revenue by the end of the decade. The internal rate of return (IRR) for R&D, a key profitability metric, though rebounding, remains low at 5.9% in 2024 [4].

- Persistent Attrition and Timelines: The success rate for drugs entering Phase 1 clinical trials has plummeted to a mere 6.7% in 2024, down from 10% a decade ago. The industry collectively spent $7.7 billion on clinical trials for assets that were ultimately terminated in a recent cycle. Furthermore, the total development time from Phase 1 to regulatory filing now exceeds 100 months (over 8 years), a 7.5% increase in the last five years [4].

- The Patent Cliff: An immediate strategic threat is the "patent cliff," where exclusivity loss on blockbuster drugs opens the market to generics. Between 2025 and 2029, an estimated $350 billion of revenue is at risk due to patent expirations [4].

Table 3: Key Performance Indicators and Challenges in Pharmaceutical R&D [4]

| Metric | Current Value / Trend | Strategic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Average Cost to Launch New Drug | $2.229+ Billion | Creates immense pressure to improve R&D efficiency and prioritize high-potential candidates. |

| Phase 1 Success Rate | 6.7% (2024) | Necessitates early, data-driven "go/no-go" decisions to fail fast and cheaply. |

| Total Development Time | >100 Months (7.5% increase) | Demands adoption of agile methodologies and regulatory fast lanes to accelerate timelines. |

| Revenue at Risk from Patent Cliff | $350 Billion (2025-2029) | Drives aggressive M&A, in-licensing, and focus on novel mechanisms of action to replenish pipelines. |

Strategic Pillars for PSPP Optimization in Pharma

To revitalize the R&D pipeline, companies are focusing on strategic pillars that enhance the predictability and efficiency of the PSPP chain [4].

- Data-Driven Discovery: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to transform the "Process" stage. AI accelerates target identification by analyzing complex biological datasets and optimizes lead compounds by predicting their efficacy and safety properties, thereby de-risking development [4].

- Open Innovation and Partnerships: Mitigating risk and diversifying the pipeline through M&A, in-licensing, and strategic collaborations. This provides access to external expertise and late-stage assets to counter the patent cliff [4].

- Agility and Efficiency: Adopting adaptive trial designs and a "fail fast, fail cheap" philosophy. This involves rigorous, data-driven decisions to terminate programs that do not show strong signs of clinical activity, reallocating resources to more promising candidates [4].

- Portfolio Reimagination: Focusing R&D efforts on areas of high unmet medical need and novel mechanisms of action (MoAs). This strategy, exemplified by the success of GLP-1 agonists, is crucial for achieving higher returns and securing new intellectual property [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of research within the PSPP framework, in both materials science and pharmaceuticals, relies on a suite of essential reagents, materials, and computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for PSPP-Driven Research

| Category | Item / Technology | Function in PSPP Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Science | Magnetic Fillers (NdFeB, Fe3O4) [1] | Provide magnetic responsiveness, enabling actuation in polymer composites. |

| Polymer Matrices (Thermosets, Thermoplastics) [1] | Form the structural body of the composite, determining mechanical and thermal properties. | |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) [2] | Serve as sustainable, biodegradable base materials for developing eco-friendly products. | |

| Pharmaceutical R&D | AI/ML Platforms for Drug Discovery [4] | Analyze vast datasets to identify biological targets and optimize lead compounds (Process). |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Systems [4] | Rapidly test thousands of compounds for biological activity, accelerating Property assessment. | |

| Bioreactors for API Biosynthesis [2] | Enable the scalable production (Process) of biologically-derived APIs and polymers. | |

| Analytical & Computational | Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) [1] | Characterizes micro- and nano-scale Structure (e.g., particle dispersion, porosity). |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) [3] | Measures thermal transitions (e.g., Tm, Tg, crystallinity), a key Property of materials. | |

| Multiphysics Simulation Software [3] | Models the entire PSPP chain computationally, predicting performance from process parameters. |

The PSPP framework provides a universal and powerful logic for navigating the complexities of research and development, from designing advanced functional materials to optimizing pharmaceutical pipelines. In materials science, it creates a direct, causal pathway from fabrication to function, as evidenced by the precise design of magnetic robots and sustainable biopolymers [1] [2]. In pharmaceuticals, it offers a structured lens to analyze and address the critical challenges of cost, attrition, and timelines, emphasizing the need for data-driven strategies and efficient capital allocation [4].

The cross-disciplinary application of PSPP reveals a common theme: success hinges on a deep, quantitative understanding of the relationships between each stage. The future of innovation in both fields will be driven by the integration of advanced tools like AI and multiscale modeling to better predict, control, and optimize these PSPP relationships, thereby de-risking development and accelerating the creation of high-performance materials and life-saving therapeutics [1] [4] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this framework is not just an academic exercise but a strategic imperative for achieving breakthrough performance.

The journey of a drug from concept to clinic is governed by the fundamental interplay of its Processing, Structure, Properties, and Performance (PSPP). This framework provides a systematic approach for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the complex landscape of modern therapeutics. Molecular structure forms the foundational blueprint, dictating the biological properties and interactions with physiological systems. These properties, in turn, determine how the body processes the drug through absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), ultimately governing its clinical performance in terms of efficacy and safety [5]. Understanding these core components and their intricate relationships is crucial for optimizing drug candidates, reducing attrition rates in late-stage development, and delivering effective therapies to patients. This technical guide examines each component through the lens of contemporary research methodologies, including artificial intelligence-driven structure analysis, advanced biomarker applications, and integrated experimental protocols that together form the backbone of modern pharmaceutical science.

Molecular Structure Analysis: From Atomic Configuration to System Interaction

Molecular structure serves as the fundamental starting point in the PSPP framework, defining all subsequent drug behaviors. Modern analysis extends beyond simple 2D representation to encompass 3D conformation, electronic distribution, and dynamic flexibility, all of which determine how a drug interacts with biological systems.

Advanced Structural Characterization Techniques

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for encoding drug molecular graphs. The GNNBlock approach addresses the critical challenge of balancing local substructural features with global molecular architecture [6]. This method comprises multiple GNN layers that expand the model's receptive field to capture substructural patterns across various scales. Through feature enhancement strategies and gating units, the model re-encodes structural features and filters redundant information, leading to more refined molecular representations [6]. For target proteins, local encoding strategies simulate the essence of drug-target interaction where only protein fragments in binding pockets interact with drugs, utilizing variant convolutional networks for fragment-level analysis [6].

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) relies on accurate 3D structural information of biological targets. The field has witnessed unprecedented growth in available structures through advances in structural biology techniques like cryo-electron microscopy and computational predictions from AlphaFold, which has generated over 214 million unique protein structures [7]. These structures enable virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries encompassing billions of compounds, dramatically expanding accessible chemical space [7]. The Relaxed Complex Method incorporates molecular dynamics simulations to account for target flexibility and cryptic pockets, providing more accurate binding predictions by docking compounds against representative target conformations sampled from simulations [7].

Structural Dynamics in Drug-Target Interactions

Understanding the dynamic nature of both drug molecules and their targets is crucial for predicting interaction outcomes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable for modeling conformational changes within ligand-target complexes upon binding [7]. Accelerated MD methods address the challenge of crossing substantial energy barriers within simulation timeframes by adding a boost potential to smooth the system potential energy surface, enabling more efficient sampling of distinct biomolecular conformations [7].

For drug molecules themselves, structural properties including lipophilicity (Log P), molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, topological polar surface area (TPSA), and rotatable bonds significantly influence biological interactions. These parameters form the basis of drug-likeness assessments such as Lipinski's Rule of Five and subsequent refinements that help prioritize compounds with higher probability of success [5].

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors and Their Impact on Drug Properties

| Molecular Descriptor | Structural Influence | Impact on Drug Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity (Log P/Log D) | Hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance | Membrane permeability, solubility, metabolism |

| Molecular Weight | Molecular size | Permeability, oral bioavailability |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors | Polar interactions | Solubility, membrane permeation |

| Topological Polar Surface Area | Molecular polarity | Oral bioavailability, blood-brain barrier penetration |

| Rotatable Bonds | Molecular flexibility | Conformational adaptability, binding entropy |

| Ionization Constant (pKa) | Ionization state | Solubility, permeability, tissue distribution |

Biological Properties and Experimental Assessment

Biological properties represent the functional manifestation of molecular structure, encompassing physicochemical characteristics, binding affinities, and pharmacological activities that determine how a drug behaves in biological systems.

Fundamental Property Profiles

Drug properties comprise structural, physicochemical, biochemical, pharmacokinetic, and toxicity characteristics that collectively determine a compound's suitability as a therapeutic agent [5]. The concept of "drug-like properties" refers to those compounds with sufficiently acceptable ADME properties and toxicity profiles to survive through Phase I clinical trials [5]. Key properties include solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and safety parameters, each playing a critical role in the compound's eventual success.

Ionization characteristics profoundly impact drug properties through their influence on solubility and permeability. The pH-partition hypothesis describes how ionized molecules exhibit higher aqueous solubility but lower membrane permeability compared to their neutral counterparts [5]. This relationship creates a fundamental tradeoff that medicinal chemists must navigate, as expressed by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equations for acids and bases:

- Acids: S = S₀(1 + 10^(pH - pKa))

- Bases: S = S₀(1 + 10^(pKa - pH))

Where S₀ represents the solubility of the neutral compound [5].

Property Optimization Strategies

Multi-parameter optimization approaches have evolved from simple rule-based systems to sophisticated computational models that balance efficacy, selectivity, PK properties, and safety [5]. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and physiologically based PK (PBPK) approaches enable more accurate prediction of human clinical outcomes based on preclinical property data [5].

The "three pillars of survival" concept emphasizes the fundamental principles that drug candidates must fulfill: exposure at the site of action, target binding, and expression of functional pharmacological activity [5]. Drug properties primarily focus on the first pillar, ensuring adequate drug exposure at the intended site of action through optimized ADME characteristics.

Table 2: Biological Property Optimization Strategies

| Property Challenge | Experimental Assessment | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Solubility | Kinetic and thermodynamic solubility assays | Salt formation, prodrugs, formulation approaches, structural modification to reduce crystal lattice energy |

| Poor Permeability | PAMPA, Caco-2, MDCK assays | Reduce hydrogen bond count, lower TPSA, moderate lipophilicity, prodrug approaches |

| Rapid Metabolism | Liver microsomes, hepatocyte stability assays | Structural blocking of metabolic soft spots, introduction of metabolically stable groups |

| Toxicity | Cytotoxicity assays, genetic toxicity screening, cardiovascular safety profiling | Structural alert mitigation, isosteric replacement, prodrug strategies |

Drug Processing: ADME Principles and Experimental Methodologies

Drug processing encompasses the disposition of pharmaceutical compounds within biological systems, following the fundamental principles of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME). Understanding these processes is essential for predicting in vivo performance based on molecular structure and biological properties.

Absorption and Distribution Mechanisms

Absorption processes determine the rate and extent to which a drug enters systemic circulation. The biopharmaceutics classification system categorizes drugs based on solubility and permeability characteristics, providing a framework for predicting absorption behavior. For oral administration, both solubility and permeability must be balanced, often requiring careful manipulation of pKa to maintain adequate dissolution while allowing sufficient neutral species for membrane permeation [5].

Distribution throughout the body determines drug access to target sites and contributes to volume of distribution and half-life. Particularly challenging is blood-brain barrier penetration for CNS-targeted therapeutics. Computational studies have identified optimal property ranges for CNS drugs, including molecular weight (~305), ClogP (~2.8), topological polar surface area (~45), and hydrogen bond donors (≤1) [5]. P-glycoprotein susceptibility represents an additional critical factor influencing brain exposure.

Metabolism and Excretion Pathways

Metabolism represents the primary clearance mechanism for most small molecule drugs, with hepatic enzymes—particularly cytochrome P450 family—mediating oxidative transformations. Metabolic stability assays using liver microsomes or hepatocytes provide early assessment of clearance potential, while metabolite identification studies reveal structural vulnerabilities. Transporters play increasingly recognized roles in both hepatic and renal elimination, requiring dedicated assessment during lead optimization.

Excretion pathways include renal elimination of hydrophilic compounds and biliary excretion of larger, more lipophilic molecules. These processes collectively determine systemic exposure and elimination half-life, directly impacting dosing regimen design. The integration of in vitro ADME data into PBPK models enables quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetics, bridging the gap between molecular properties and clinical performance.

Clinical Performance: Biomarkers and Efficacy Assessment

Clinical performance represents the ultimate validation of the PSPP framework, where optimized molecular structures with favorable properties and processing characteristics demonstrate therapeutic value in human populations.

Biomarker Applications in Clinical Development

Biomarkers, defined as "defined characteristics measured as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention" [8], play increasingly critical roles in modern drug development. The BEST resource categorizes biomarkers into seven distinct types, each with specific applications throughout the drug development continuum [9].

Diagnostic biomarkers identify patients with specific diseases, while prognostic biomarkers define higher-risk populations to enhance trial efficiency [9]. Predictive biomarkers enable selection of patients most likely to respond to treatment, as exemplified by EGFR mutation status in non-small cell lung cancer guiding EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor use [9]. Pharmacodynamic/response biomarkers provide early readouts of biological activity, while safety biomarkers detect potential adverse effects earlier than traditional clinical signs [9].

Table 3: Biomarker Categories and Clinical Applications

| Biomarker Category | Clinical Use | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptibility/Risk | Identify individuals with increased disease risk | BRCA1/2 mutations for breast/ovarian cancer |

| Diagnostic | Diagnose disease presence | Hemoglobin A1c for diabetes mellitus |

| Monitoring | Track disease status or treatment response | HCV RNA viral load for hepatitis C infection |

| Prognostic | Predict disease outcome independent of treatment | Total kidney volume for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| Predictive | Predict response to specific treatments | EGFR mutation status in non-small cell lung cancer |

| Pharmacodynamic/Response | Measure biological response to therapeutic intervention | HIV RNA viral load in HIV treatment |

| Safety | Monitor potential drug-induced toxicity | Serum creatinine for acute kidney injury |

Biomarker Qualification and Regulatory Acceptance

The Biomarker Qualification Program provides a structured framework for regulatory acceptance of biomarkers through a collaborative, multi-stage process [8]. Fit-for-purpose validation recognizes that the level of evidence needed to support biomarker use depends on the specific context of use and application purpose [9]. This approach tailors validation requirements to the biomarker type and intended decision-making context.

The qualification process involves three distinct stages: Letter of Intent submission, Qualification Plan development, and Full Qualification Package preparation [8]. Successful qualification enables biomarker use across multiple drug development programs within the specified context of use, promoting consistency and reducing duplication of effort throughout the industry [9].

Integrated Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that bridge molecular structure to biological activity and processing characteristics, enabling comprehensive PSPP profiling.

GNNBlock-DTI Protocol for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Purpose: Predict interaction between drug compounds and target proteins using graph neural networks with enhanced substructure encoding.

Methodology:

- Drug Representation: Convert drug SMILES strings to molecular graphs using RDKit, with node embeddings constructed from atomic properties (Atomic Symbol, Formal Charge, Degree, IsAromatic, IsInRing) totaling 64 dimensions [6].

- GNNBlock Architecture: Implement multiple GNN layers as a GNNBlock unit to capture hidden structural patterns within local ranges. Apply feature enhancement strategy to re-encode structural features and utilize gating units for redundant information filtering [6].

- Target Protein Encoding: Represent targets as both amino acid sequences and residue-level graphs. For sequences, use ProtBert embeddings encoded through multi-scale CNNs. For graphs, construct using ProtBert and ESM-1b encodings processed through weighted GCNs [6].

- Interaction Prediction: Combine drug and target embeddings, feed to Multilayer Perceptron classifier for DTI prediction.

Output: Probability scores for drug-target interactions with visualization of key substructural features contributing to binding.

Biomarker Analytical Validation Protocol

Purpose: Establish performance characteristics of biomarker measurement assays for specific contexts of use.

Methodology:

- Precision Assessment: Conduct within-run and between-run replicates at multiple concentrations covering the assay range. Calculate coefficient of variation with acceptance criteria typically <20% for biological biomarkers [9].

- Accuracy Evaluation: Compare measured values to reference standards or validated methods. Demonstrate recovery of 85-115% across the analytical measurement range [9].

- Sensitivity Determination: Establish limit of detection and lower limit of quantification through serial dilution of analyte in biological matrix.

- Specificity Verification: Test cross-reactivity with related analytes and potential interfering substances present in the biological matrix.

- Stability Assessment: Evaluate analyte stability under storage, freeze-thaw, and processing conditions relevant to the intended use.

Output: Validated assay protocol with defined performance characteristics supporting the biomarker's context of use in drug development.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

Purpose: Identify potential drug candidates through computational docking to target structures.

Methodology:

- Target Preparation: Obtain 3D protein structure from PDB or AlphaFold database. Process structure by adding hydrogen atoms, optimizing side-chain orientations, and defining binding site [7].

- Compound Library Preparation: Curate screening library from commercial sources or enumerate virtual compounds. Prepare 3D structures with proper protonation states and tautomers.

- Molecular Docking: Perform high-throughput docking using appropriate software. Utilize hierarchical approaches with fast initial screening followed by more rigorous secondary screening [7].

- Post-Docking Analysis: Cluster top-ranking poses, visualize binding interactions, and prioritize compounds based on complementary interaction patterns.

- Experimental Validation: Procure or synthesize top-ranked compounds for biochemical and cellular assays to confirm activity.

Output: Ranked list of potential hit compounds with predicted binding modes and interaction patterns.

Visualization of Core Pathways and Workflows

PSPP Integration Pathway

Biomarker Qualification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Polar aprotic solvent for compound dissolution | Cell culture assays, stock solution preparation [10] [5] |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Molecular graph generation from SMILES strings, descriptor calculation [6] |

| Liver Microsomes | Hepatic metabolic enzyme systems | Metabolic stability assessment, metabolite identification [5] |

| Caco-2/MDCK Cells | Intestinal/kidney epithelial cell models | Permeability screening, transporter studies [5] |

| ProtBert/ESM-1b | Protein language models | Protein sequence embedding, structure-function prediction [6] |

| AlphaFold Database | Protein structure prediction repository | Target structure access for structure-based design [7] |

| REAL Database | Commercially available compound library | Virtual screening, hit identification [7] |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Analytical test systems | Biomarker quantification, validation studies [9] |

The PSPP framework provides a systematic approach for navigating the complex journey from molecular structure to clinical performance. By understanding the fundamental relationships between these core components, drug development professionals can make more informed decisions, optimize resource allocation, and increase the probability of technical success. Emerging methodologies—including AI-enhanced structure analysis, biomarker-guided development, and integrated computational-experimental approaches—continue to refine our ability to predict and optimize drug behavior across the development continuum. The future of pharmaceutical research lies in increasingly sophisticated integration of these components, leveraging quantitative modeling and predictive analytics to accelerate the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients while maintaining rigorous safety and efficacy standards.

The fundamental paradigm of modern drug discovery rests on the principle that a compound's molecular structure is the primary determinant of its biological activity and therapeutic potential. This structure-activity relationship (SAR) forms the critical link between chemical design and clinical outcomes, enabling researchers to systematically optimize compound efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetic properties. Understanding these relationships allows for the transition from observed biological effects to rational drug design, transforming drug discovery from a largely empirical process to a predictive science. The molecular structure of a compound dictates its physical-chemical properties, its interaction with biological targets, and its behavior in complex physiological environments, ultimately determining its therapeutic performance [11].

Advances in computational methods and structural biology have dramatically enhanced our ability to decipher and exploit these relationships. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, in particular, has emerged as an indispensable tool for predicting biological activity from chemical structure, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [11]. Furthermore, recent research has illuminated how specific structural features govern fundamental biological processes, such as the formation of biomolecular condensates through phase separation—a mechanism with profound implications for cellular organization and function [12]. This technical guide explores the molecular foundations of biological activity, provides detailed methodologies for establishing structure-activity relationships, and demonstrates their application in therapeutic development.

Molecular Foundations of Biological Activity

Key Structural Determinants of Bioactivity

A molecule's biological activity is governed by specific structural features that determine its interactions with biological targets. These features include:

- Molecular size and shape: Determines the ability to fit into binding pockets of target proteins.

- Electronic distribution: Influences binding affinity through electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and cation-π interactions.

- Hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity balance: Affects membrane permeability, solubility, and distribution within the body.

- Stereochemistry: The spatial arrangement of atoms can dramatically impact binding specificity and metabolic stability.

- Functional group composition: Specific chemical groups mediate direct interactions with biological targets through covalent and non-covalent bonding.

The presence of particular structural motifs can dramatically influence biological outcomes. For instance, in RNA-binding proteins, arginine-rich RGG/RG motifs facilitate phase separation through cation-π interactions, enabling the formation of biomolecular condensates that organize cellular biochemistry [12]. Similarly, the incorporation of five- and six-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycles in drug candidates often improves target selectivity and physicochemical properties through their action as cyclic bioisosteres [13].

Molecular Interactions with Biological Targets

The binding of a drug molecule to its biological target occurs through complementary structural and electronic interactions. Multivalent interactions—multiple simultaneous binding events between a molecule and its target—are particularly effective drivers of high-affinity binding and can induce phase separation to form biomolecular condensates [12]. These interactions include:

- π-π stacking between aromatic rings

- Electrostatic interactions between charged groups

- Hydrogen bonding between donor and acceptor atoms

- Hydrophobic effects that drive the sequestration of non-polar surfaces

- Van der Waals forces that optimize shape complementarity

Proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) or low-complexity domains (LCDs) exemplify how structural flexibility facilitates multivalent interactions. These regions lack stable tertiary structures but contain multiple interaction sites that enable the formation of dynamic molecular networks central to cellular signaling and regulation [12].

Figure 1: The Structural Determinants of Bioactivity. This diagram illustrates how molecular structure influences physicochemical properties, which drive specific molecular interactions with biological targets to ultimately determine therapeutic outcomes.

Methodologies for Establishing Structure-Activity Relationships

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR modeling represents a cornerstone approach for quantitatively linking molecular structure to biological activity. These mathematical models correlate structural descriptors of compounds with their measured biological activities, enabling the prediction of activities for novel compounds [11]. The general QSAR equation takes the form:

Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃...)

Where D₁, D₂, D₃ represent molecular descriptors that quantitatively encode structural features [11].

The development of robust QSAR models follows a systematic workflow:

- Data Collection and Curation: Compiling a dataset of compounds with reliable biological activity data

- Descriptor Calculation: Computing numerical representations of molecular structures

- Feature Selection: Identifying the most relevant descriptors for the biological endpoint

- Model Training: Establishing mathematical relationships between descriptors and activity

- Validation: Rigorously testing model performance on external compounds

Table 1: QSAR Modeling Techniques and Applications

| Modeling Technique | Key Features | Optimal Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Linear relationship between descriptors and activity; highly interpretable | Initial SAR exploration; datasets with clear linear trends | Cannot capture complex non-linear relationships |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Non-linear modeling; capable of learning complex patterns | Complex SAR with multiple interacting factors | Requires large datasets; "black box" interpretation |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Effective for classification and regression; handles high-dimensional data | Binary activity classification; virtual screening | Parameter sensitivity; computational intensity |

| Random Forest | Ensemble method; robust to noise and outliers | Large diverse chemical libraries; feature importance ranking | Limited extrapolation beyond training set domain |

Experimental Protocol: QSAR Model Development for NF-κB Inhibitors

The following detailed protocol outlines the development of validated QSAR models for predicting NF-κB inhibitory activity, based on a case study of 121 compounds [11]:

Step 1: Data Set Compilation and Preparation

- Identify 121 compounds with reported half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values against NF-κB from scientific literature

- Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) to create a normally distributed response variable

- Apply Kennard-Stone algorithm or random selection to divide compounds into training set (≈80 compounds, 66%) and test set (≈41 compounds, 34%)

- Ensure structural diversity and activity range representation in both sets

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Generate optimized 3D molecular structures for all compounds using molecular mechanics force fields

- Calculate topological, geometrical, and electronic descriptors using software such as DRAGON, PaDEL, or alvaDesc

- Apply genetic algorithm or stepwise selection to identify most relevant descriptors

- Remove highly correlated descriptors (r > 0.95) to minimize multicollinearity

- Select 5-10 optimal descriptors based on statistical significance and chemical interpretability

Step 3: Model Development Using Multiple Linear Regression

- Construct MLR model using training set data: pIC₅₀ = a + b₁D₁ + b₂D₂ + ... + bₙDₙ

- Apply least-squares regression to estimate coefficients (b₁, b₂, ..., bₙ) and intercept (a)

- Evaluate model statistical parameters: correlation coefficient (R²), standard error of estimate, F-statistic

- Ensure all regression coefficients are statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Step 4: Artificial Neural Network Model Development

- Design feed-forward neural network architecture with 8 input neurons (descriptors), 11 hidden neurons, and 1 output neuron (pIC₅₀)

- Implement backpropagation algorithm with sigmoid activation functions

- Train network using training set with early stopping to prevent overfitting

- Optimize learning rate and momentum parameters through grid search

Step 5: Model Validation and Applicability Domain

- Internal Validation: Calculate leave-one-out cross-validated R² (Q²) for training set

- External Validation: Predict pIC₅₀ values for test set compounds

- Calculate predictive R² and root mean square error for test set predictions

- Define applicability domain using leverage approach to identify reliable prediction boundaries

- Identify outliers and analyze structural features responsible for prediction errors

This protocol yields validated QSAR models capable of predicting NF-κB inhibitory activity for novel compounds, with the ANN model typically demonstrating superior predictive performance compared to MLR for complex biological targets [11].

Figure 2: QSAR Modeling Workflow. This diagram outlines the systematic process for developing validated QSAR models, from data preparation through model application.

Advanced Molecular Representation Methods

Modern approaches to molecular representation have evolved beyond traditional descriptors to AI-driven methods that better capture structural complexity:

- Language model-based representations: Treat molecular strings (SMILES) as chemical language, using transformer architectures to learn contextual structural representations [14]

- Graph-based representations: Represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, employing graph neural networks to capture topological relationships [14]

- Multimodal learning: Integrate multiple representation types (structural, physicochemical, topological) for enhanced predictive capability [14]

- Contrastive learning: Leverage self-supervised learning to create representations that highlight structurally similar compounds with similar activities [14]

These advanced representations have demonstrated particular utility in scaffold hopping—identifying structurally distinct compounds that share similar biological activity—by capturing essential pharmacophoric features while enabling exploration of diverse chemical space [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Structure-Activity Relationship Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in SAR Studies | Application Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Curated bioactivity database providing structure-activity data for drug discovery | Source of compound activity data for QSAR model development | Data quality varies; requires curation and standardization [15] |

| DRAGON/alvaDesc Software | Molecular descriptor calculation for quantitative structural representation | Generation of topological, constitutional, and quantum-chemical descriptors | Different descriptor sets may be optimal for different biological endpoints [11] |

| Polymer Fingerprints (PFP) | Polymer-specific structural representation for machine learning applications | Decoding polymer structures for property prediction using neural networks | Requires specialized decoding tools for polymer informatics [16] |

| Molecular Fingerprints (ECFP) | Binary representation of molecular substructures for similarity assessment | Similarity searching, virtual screening, and clustering analysis | Radius and bit length parameters significantly impact performance [14] |

| CURATED CRISPR/Cas Systems | Gene editing and imaging tools for target validation and mechanistic studies | Investigating molecular mechanisms of condensate formation in cellular models | Enables real-time monitoring of biomolecular condensates [12] |

| Optogenetic Tools | Light-controlled protein oligomerization for precise manipulation of cellular processes | Controlling biomolecular condensate formation and dissolution with temporal precision | Enables mechanistic studies of phase separation dynamics [12] |

Case Studies and Therapeutic Applications

Biomolecular Condensates and Neurodegenerative Disease

The relationship between molecular structure and biological activity is strikingly illustrated in the formation of biomolecular condensates through liquid-liquid phase separation. Specific structural features drive this process:

- Low-complexity domains (LCDs) in RNA-binding proteins like TDP-43 and FUS enable multivalent interactions that promote phase separation [12]

- Cation-π interactions involving arginine-rich motifs (RGG/RG) significantly lower the threshold for condensation [12]

- Aromatic residues (tyrosine, phenylalanine) in LCDs enhance phase separation propensity through π-π interactions [12]

In neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), mutations in these domains alter the material properties of condensates, leading to pathogenic solidification and neuronal dysfunction [12]. This understanding enables therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating condensate dynamics without disrupting essential cellular functions.

Structure-Based Optimization in Drug Discovery

Recent drug approvals exemplify strategic structural optimization to enhance therapeutic outcomes:

- Golidocitinib: Strategic placement of solubilizing groups achieved dual benefits of enhanced target selectivity and improved physicochemical properties [13]

- Zorifertinib: Careful control of rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond donors, and molecular lipoliphicity optimized blood-brain barrier penetration while maintaining oral bioavailability [13]

These case studies demonstrate how systematic structure-based optimization addresses key challenges in drug development, including tissue-specific distribution, metabolic stability, and target selectivity.

Table 3: Structural Modifications and Their Therapeutic Impacts

| Structural Feature | Biological Consequence | Therapeutic Impact | Example Compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-containing heterocycles | Enhanced target binding through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions | Improved potency and selectivity | Inavolisib, Vorasidenib [13] |

| Controlled rotatable bonds | Reduced molecular flexibility improves membrane penetration | Enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration | Zorifertinib [13] |

| Optimized lipophilicity | Balanced hydrophobicity for membrane permeability and solubility | Favorable tissue distribution and oral bioavailability | Aprocitentan, Ensitrelvir [13] |

| Intrinsically disordered regions | Facilitates multivalent interactions and phase separation | Biomolecular condensate formation with implications for multiple diseases | TDP-43, FUS proteins [12] |

| Post-translational modification sites | Alters interaction surfaces and binding affinity | Regulation of condensate dynamics in response to cellular signals | SRRM2, Ki-67 proteins [12] |

The critical link between molecular structure and biological activity represents both a fundamental scientific principle and a practical framework for therapeutic development. Through established methodologies like QSAR modeling and emerging approaches including AI-driven molecular representation, researchers can systematically decipher this relationship to design compounds with optimized therapeutic profiles. The integration of structural biology, computational chemistry, and cellular neuroscience has revealed how specific molecular features govern complex biological phenomena, from targeted protein inhibition to biomolecular condensate formation. As these approaches continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the development of precisely targeted therapeutics with enhanced efficacy and reduced adverse effects, ultimately improving patient outcomes across a spectrum of human diseases.

In modern pharmaceutical research, the journey from a theoretical compound to a marketable drug is notoriously lengthy, expensive, and fraught with high failure rates [17]. This process, which can cost approximately $2.8 billion and take 12-15 years to complete, demands strategies to improve efficiency and decision-making [17]. Quantitative modeling approaches have emerged as indispensable tools in this context, providing a mechanistic framework to predict how drugs will behave in biological systems before extensive experimental work begins. By integrating processing structure properties performance data, these models help researchers bridge the gap between initial compound design and final therapeutic outcome.

These computational techniques enable scientists to move beyond empirical observations to a more principled understanding of drug behavior. The models serve as a virtual testing ground, allowing for the in silico evaluation of drug candidates under a wide range of physiological conditions and patient characteristics. This guide focuses on two pivotal mechanistic modeling approaches: Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and its more comprehensive extension, Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP). These methodologies represent the cutting edge in model-informed drug discovery and development (MID3), supporting critical decisions from early discovery through clinical development and regulatory submission [18] [19] [20].

Core Modeling Approaches: PBPK and QSP

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK modeling is a compartment and flow-based approach to pharmacokinetic modeling where each compartment represents a discrete physiological entity, such as an organ or tissue, connected by the circulating blood system [21] [20]. These models are constructed using a "bottom-up" approach, starting with known physiology and drug-specific parameters [21]. The fundamental principle is to create a mathematical representation that mirrors the actual structure and function of the biological system, allowing researchers to simulate drug concentration-time profiles not just in plasma but in specific tissues of interest [20].

The history of PBPK modeling dates back to 1937 with Teorell's pioneering work, but its widespread application in the pharmaceutical industry has accelerated over the past decade due to several key developments [20]. Critical advancements include improved methods for predicting tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients (Kp values) from in vitro and in silico data, and the emergence of commercial platforms like Simcyp, GastroPlus, and PK-SIM that have made this methodology more accessible [20]. Regulatory agencies now frequently encounter PBPK analyses in submissions, particularly for assessing complex drug-drug interactions and special population dosing [20].

Key Components of PBPK Models

A typical PBPK model consists of several integrated components:

System-Specific Parameters: These include tissue volumes (or weights) and tissue blood flow rates specific to the species of interest (e.g., human, rat, dog) [20]. These parameters are typically obtained from physiological literature and remain fixed for a given population.

Drug-Specific Parameters: These compound-specific properties include molecular weight, lipophilicity (Log P), acid dissociation constant (pKa), plasma protein binding, and permeability [20]. These are determined through in vitro experiments and structure-based predictions.

Process-Specific Parameters: These describe the key ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) processes, including clearance mechanisms (enzymatic metabolism, transporter-mediated uptake/efflux) and absorption parameters [20].

PBPK models typically represent major tissues and organs, including adipose, bone, brain, gut, heart, kidney, liver, lung, muscle, skin, and spleen [20]. Two primary kinetic frameworks govern drug distribution in these models: perfusion rate-limited kinetics for small lipophilic molecules where blood flow is the limiting factor, and permeability rate-limited kinetics for larger polar molecules where membrane permeability becomes the rate-determining step [20].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Modeling

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) represents an extension of PBPK modeling that integrates drug pharmacokinetics with a mechanistic understanding of pharmacological effects on tissues and organs [21]. As a discipline, QSP has matured over the past decade and is now increasingly applied in both academia and industry to address diverse problems throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline [18] [19]. QSP models typically incorporate features of the drug (dose, regimen, target site exposure) with target biology, downstream effectors at molecular, cellular, and pathophysiological levels, and functional endpoints of interest [19].

The power of QSP lies in its ability to provide a common "denominator" for quantitative comparisons, enabling researchers to evaluate multiple therapeutic modalities for a given target, compare a novel compound against established treatments, or optimize combination therapy approaches [19]. This is particularly valuable in complex disease areas like oncology and immuno-oncology, where therapeutic combinations are increasingly the standard of care [19]. QSP models have demonstrated impact across various applications, from supporting new indications for approved drugs to enabling rational selection of drug combinations based on efficacy projections [19].

The QSP Workflow

A mature QSP modeling workflow is essential for efficient, reproducible model development and qualification [19]. This workflow typically follows these key stages:

Data Programming and Standardization: Converting raw data from various sources into a standardized format that constitutes the basis for all subsequent modeling tasks [19].

Data Exploration and Model Conceptualization: Assessing data consistency across experimental settings, identifying trends, and developing an initial model structure based on biological knowledge [19].

Model Implementation and Parameter Estimation: Encoding the mathematical representation of the biological system and estimating parameters through fitting to experimental data, often using a multi-start strategy to identify globally optimal solutions [19].

Model Qualification and Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluating parameter identifiability, computing confidence intervals, and assessing how uncertainty in parameters affects model outputs [19].

Model Application and Communication: Using the qualified model to simulate experimental scenarios and effectively communicating results to multidisciplinary teams and stakeholders [19].

Comparative Analysis: PBPK vs. QSP vs. PopPK

Table 1: Comparison of Key Quantitative Modeling Approaches in Drug Development

| Feature | PBPK (Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic) | QSP (Quantitative Systems Pharmacology) | PopPK (Population Pharmacokinetic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Bottom-up, mechanistic [21] | Bottom-up, systems-level mechanistic [21] [19] | Top-down, empiric [21] |

| Model Components | Physiologic organs/tissues with blood flow connections [21] [20] | Drug PK, target biology, downstream effectors, pathophysiological processes [19] | Abstract compartments without direct physiological meaning [21] |

| Primary Focus | Predicting drug concentration in plasma and specific tissues over time [21] [20] | Predicting both drug concentration and pharmacological effect [21] [19] | Identifying sources of variability in a drug's kinetic profile [21] |

| Parameter Source | In vitro and pre-clinical data, physiology [21] [20] | Integration of diverse data types (multi-omics, clinical, in vitro) [19] | Fitting to observed clinical PK data [21] |

| Handling of Variability | Typically describes the typical subject without variability [21] | Can incorporate variability; emerging hybrid approaches with PopPK [19] | Estimates inter-individual variability and residual error [21] |

| Key Applications | Drug-drug interactions, pediatric extrapolation, first-in-human dose prediction [21] [20] | Mechanism of action analysis, dose/regimen optimization, combination therapy selection [19] | Covariate analysis (age, renal function), dosing individualization [21] |

| Regulatory Use | Accepted for DDI and specific extrapolations [20] | Growing impact from discovery to late-stage development [19] | Well-established for covariate analysis and dosing justification [21] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

PBPK Model Development Protocol

The development of a PBPK model follows a systematic, iterative process:

System Selection and Parameterization:

- Select the appropriate physiological system (e.g., human, rat, dog) and define system-specific parameters, including organ weights/tissues volumes and blood flow rates, sourced from physiological literature [20].

- For human models, specific populations (e.g., pediatric, geriatric, impaired organ function) can be represented by modifying the baseline physiology using published data [20].

Drug Parameterization:

- Determine key drug-specific physicochemical properties, including molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), acid dissociation constant (pKa), and blood-to-plasma ratio [20].

- Measure in vitro ADME parameters: permeability (e.g., Caco-2, PAMPA), metabolic stability (e.g., liver microsomes, hepatocytes), plasma protein binding, and transporter kinetics [20].

- Apply In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) to scale in vitro clearance data to whole-organ clearance [20].

Model Implementation:

- Implement the model structure in a suitable software platform (e.g., MATLAB, R, or commercial tools like GastroPlus or Simcyp) using a system of ordinary differential equations [20].

- For each tissue compartment, define the distribution kinetics (typically perfusion-rate limited for small molecules) [20].

- Incorporate relevant clearance mechanisms (hepatic, renal) based on the elimination pathways identified for the drug [20].

Model Verification and Refinement:

- Verify the model by comparing simulated plasma and tissue concentration-time profiles against observed in vivo data (preclinical or clinical) [20].

- If discrepancies exist, refine specific drug parameters (e.g., tissue partition coefficients, clearance) within physiologically plausible ranges to improve the fit [20].

- Evaluate model performance using goodness-of-fit criteria and visual predictive checks [20].

QSP Model Development Protocol

QSP model development is a knowledge-driven, iterative process focused on capturing essential biological mechanisms:

Problem Formulation and Scope Definition:

Knowledge Assembly and Data Curation:

- Conduct a comprehensive literature review to assemble prior knowledge on rate constants, binding affinities, baseline concentrations, and physiological parameters [19] [22].

- Create a standardized database of relevant quantitative data from diverse sources (publications, internal experiments, public databases), noting experimental conditions and variability [19].

Mathematical Representation:

- Translate the biological network into a mathematical framework using ordinary differential equations (ODEs), partial differential equations (PDEs), or agent-based models (ABMs) to describe the dynamics of system components [19] [22].

- Incorporate the drug PK sub-model (which can be a PBPK model) and link drug concentration at the site of action to target engagement and downstream pharmacological effects [19].

Parameter Estimation and Model Calibration:

- Identify model parameters that are not well-constrained by prior knowledge for estimation against experimental data [19].

- Use a multi-start parameter estimation strategy to fit the model to the assembled data, which may include in vitro dose-response, biomarker time-course, and clinical endpoint data [19].

- Apply profile likelihood or similar methods to assess parameter identifiability and confidence intervals [19].

Model Qualification and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Perform local and global sensitivity analyses to identify parameters that most significantly influence key model outputs [19] [22].

- Qualify the model by testing its predictive performance against data sets not used during model calibration [19].

- Document model assumptions, limitations, and evaluation results thoroughly [19].

Visualization of Modeling Workflows

PBPK Model Structure and Workflow

Diagram 1: PBPK model development workflow.

QSP Workflow and Model Scope

Diagram 2: QSP workflow and multi-scale model scope.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial PBPK Platforms | Simcyp Simulator, GastroPlus, PK-SIM [20] | Integrated software for PBPK model development, simulation, and population-based analysis. |

| QSP Modeling Software | MATLAB, R, Python (with ODE solvers) [19] [22] | Flexible programming environments for implementing and simulating custom QSP models. |

| General-Purpose PK/PD Tools | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix WinNonlin | Population PK/PD analysis and parameter estimation using non-linear mixed effects methods. |

| In Vitro ADME Assays | Human liver microsomes, hepatocytes, transfected cell lines [20] | Generation of drug-specific metabolism and transport parameters for IVIVE in PBPK. |

| Protein Binding Assays | Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration [20] | Determination of fraction unbound in plasma and tissues for PBPK parameterization. |

| Physicochemical Property Assays | Log P/D, pKa, solubility, permeability (PAMPA, Caco-2) [20] | Characterization of fundamental drug properties governing distribution and absorption. |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA, MSD, qPCR, flow cytometry [19] | Generation of quantitative time-course data for QSP model calibration and validation. |

Quantitative modeling approaches like PBPK and QSP represent a paradigm shift in drug development, moving the industry from largely empirical methods toward more mechanistic, predictive frameworks. These approaches directly support the processing structure properties performance research paradigm by mathematically formalizing the relationship between a drug's structural attributes, its physicochemical properties, how it is processed in the body, and its ultimate performance as a therapeutic agent [23].

The integration of these modeling methodologies throughout the drug development pipeline enables more informed decision-making, potentially reducing late-stage attrition and accelerating the delivery of new medicines to patients. As these fields mature, best practices for model development, qualification, and communication are coalescing into standardized workflows, fostering greater acceptance by regulatory agencies and enhancing their impact on drug development strategy [19] [20]. For today's drug development professionals, proficiency in these quantitative foundations is no longer optional but essential for navigating the complexities of modern therapeutic development.

PSPP in Action: Methodologies and Applications Across the Drug Development Lifecycle

Implementing Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) as a PSPP Tool

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is defined as a “quantitative framework for prediction and extrapolation, centered on knowledge and inference generated from integrated models of compound, mechanism and disease level data and aimed at improving the quality, efficiency and cost effectiveness of decision making” [24]. This approach uses a variety of quantitative methods to help balance the risks and benefits of drug products in development, with the potential to improve clinical trial efficiency, increase the probability of regulatory success, and optimize drug dosing without dedicated trials [25]. The concept that R&D decisions are “informed” rather than “based” on model-derived outputs is a central tenet of this approach [24].

The Preclinical Screening Platform for Pain (PSPP) is a program created by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) to identify and profile non-opioid, non-addictive therapeutics for pain [26]. This program provides an efficient, rigorous, one-stop screening resource to accelerate the discovery of effective pain therapies through a structured evaluation process that includes in vitro abuse liability and safety assessment, pharmacokinetics, side effect profiling, efficacy in pain models, and in vivo abuse liability testing [26].

The integration of MIDD approaches as a tool within the PSPP framework represents a powerful synergy that can enhance the prediction accuracy of therapeutic efficacy and safety during preclinical development. This combination aligns with the broader research paradigm of processing-structure-properties-performance (PSPP), where the "processing" refers to drug development methodologies, "structure" relates to the chemical and biological organization of therapeutic compounds, "properties" encompass the pharmacological characteristics, and "performance" denotes the ultimate therapeutic efficacy and safety.

MIDD Methodologies: A Quantitative Toolkit for PSPP

The implementation of MIDD within PSPP utilizes a diverse set of quantitative modeling approaches, each with distinct applications throughout the drug development continuum. These methodologies enable researchers to extract maximum information from limited preclinical data, particularly valuable for pain therapeutic development where patient populations may be limited and the need for non-opioid alternatives is urgent.

Table 1: Core MIDD Methodologies and Their PSPP Applications

| Methodology | Technical Description | PSPP Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Computational modeling to predict biological activity based on chemical structure [27] | Prioritize lead compounds with optimal analgesic properties and minimal abuse liability |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | Mechanistic modeling of the interplay between physiology and drug product quality [27] | Predict tissue-specific exposure in pain-relevant pathways and potential off-target effects |

| Population Pharmacokinetics (PPK) | Modeling approach to explain variability in drug exposure among individuals [27] | Understand how physiological factors influence analgesic exposure in diverse populations |

| Exposure-Response (ER) | Analysis of relationship between drug exposure and effectiveness or adverse effects [27] | Establish therapeutic window for pain relief versus side effects |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Integrative modeling combining systems biology and pharmacology [27] | Model pain pathways and mechanism of action within complex biological networks |

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Quantitative analysis of aggregated data from multiple studies [27] | Contextualize new analgesic efficacy against existing treatment landscape |

Fit-for-Purpose Implementation Strategy

Successful implementation of MIDD within PSPP requires a fit-for-purpose approach that aligns modeling tools with specific questions of interest and context of use [27]. This strategic framework ensures that models are appropriately matched to development milestones, guiding progression from early discovery through regulatory approval. A model or method is not considered fit-for-purpose when it fails to define the context of use, lacks data quality, or has insufficient model verification, calibration, and validation [27].

The fundamental principle involves selecting MIDD approaches based on:

- Question of Interest: The specific scientific or clinical question to be addressed

- Context of Use: How the model output will inform decision-making

- Model Evaluation: Rigorous assessment of model performance and limitations

- Influence and Risk: Consideration of the model's impact on development decisions and consequences of incorrect predictions [27]

Integrated Workflow: MIDD within PSPP Framework

The incorporation of MIDD methodologies enhances the standard PSPP workflow by adding predictive modeling layers at each stage of evaluation. This integration enables more informed decision-making about which assets should advance to subsequent testing phases, optimizing resource allocation and accelerating the development timeline.

Figure 1: Integrated MIDD-PSPP Workflow: This diagram illustrates the enhanced PSPP evaluation process with MIDD components at each stage, culminating in model-informed decisions.

MIDD-Enhanced PSPP Evaluation Stages

In Vitro Assessment Enhancement: QSAR models predict binding affinity to opioid receptors and secondary targets associated with abuse liability prior to experimental testing [27]. This computational filtering prioritizes compounds with desired characteristics for experimental validation.

Pharmacokinetic Prediction: PBPK modeling generates predictions of tissue distribution, particularly relevant for pain therapeutics that may need to reach peripheral tissues, the central nervous system, or both [27]. These models help establish appropriate dose ranges for subsequent behavioral assessments.

Side Effect Profiling with QSP: Quantitative Systems Pharmacology models simulate mechanism-based predictions on potential side effects by mapping compound activity onto biological pathways [27]. This approach identifies potential tolerability issues and neurological side effects through computational simulation before comprehensive in vivo testing.

Efficacy Optimization: Exposure-Response and Population PK/PD modeling analyzes the relationship between drug exposure and analgesic efficacy across validated preclinical pain models [27]. These models help identify optimal dosing regimens and predict human efficacious doses.

Abuse Liability Assessment: Model-Based Meta-Analysis contextualizes new compound data against known abuse liability profiles of reference compounds [27]. This comparative approach strengthens abuse potential assessment throughout the evaluation pipeline.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Integrated QSAR-PBPK Modeling for Lead Optimization

This protocol describes a standardized approach for combining QSAR and PBPK modeling to prioritize lead compounds within the PSPP framework.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Chemical structures of candidate compounds (SMILES notation or 3D coordinates)

- Biochemical assay data for calibration (IC50, Ki values where available)

- Physiological parameters for relevant species (body weight, organ volumes, blood flow rates)

- Software platforms for molecular modeling and PBPK simulation

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Compile chemical structures and experimental data for 10-50 candidate compounds representing structural diversity around lead chemotype.

- QSAR Model Development:

- Calculate molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, and thermodynamic)

- Develop partial least squares regression or machine learning model to predict target affinity

- Validate model using 5-fold cross-validation and external test set

- PBPK Model Construction:

- Incorporate compound-specific parameters (logP, pKa, blood-to-plasma ratio)

- Build multi-compartment model with relevant tissue compartments (brain, spinal cord)

- Incorporate plasma protein binding and blood cell partitioning

- Integrated Simulation:

- Run PBPK simulations across therapeutic dose range