From Chaos to Clarity: A Research-Driven Guide to Materials Data Standardization

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to implement robust materials data standardization.

From Chaos to Clarity: A Research-Driven Guide to Materials Data Standardization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to implement robust materials data standardization. It covers the foundational principles of the open science movement and the critical challenges of data veracity in materials science. The guide details a step-by-step methodological process for standardization, explores advanced tools and best practices for troubleshooting, and outlines rigorous validation techniques to ensure data integrity. By synthesizing these elements, the article aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to accelerate materials discovery, enhance reproducibility, and build a reliable foundation for AI-driven innovation in biomedical and clinical research.

Why Materials Data Standardization is the Foundation of Modern Research

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate common challenges in data-driven materials science, framed within the broader goal of improving materials data standardization.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My machine learning model performs well on training data but fails on new experimental data. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of an out-of-distribution prediction problem or a data veracity issue. The model has likely learned patterns specific to your limited training dataset that do not generalize to broader, real-world scenarios [1]. To troubleshoot:

- Check Data Domain: Ensure the new experimental data comes from the same distribution (e.g., similar synthesis conditions, measurement techniques) as your training data. Models can suffer significant performance drops when applied outside their training distribution [1].

- Validate Rigorously: Move beyond simple random train-test splits. Use temporal splits or domain-based splits to better simulate real-world performance [1].

- Review Data Quality: Inspect your training data for biases, inconsistencies, or errors. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is paramount; the predictive power of any model is contingent on the quality of the underlying data [2].

Q2: What are the key challenges in integrating computational and experimental materials data? Integrating these data types is a central challenge in data-driven materials science, primarily due to [2]:

- Lack of Standardization: Experimental and computational data are often collected and reported using different formats, standards, and metadata, creating integration barriers [2].

- Data Completeness: Experimental datasets may lack the precise parameters needed for computational models (or vice versa), creating a "data integration gap" [2].

- Data Longevity: The long-term accessibility and usability of both data types can be threatened without proper data management and preservation plans [2].

Q3: How can I ensure my computational research is reproducible? Adhering to best practices in data management and code sharing is essential [1].

- Document Code and Models: Clearly describe models, data sources, and training procedures. Use version control systems like Git for your code [1].

- Share Data and Code: Whenever possible, make the datasets and code used in your studies openly available in public repositories. This allows others to validate and build upon your work [1].

- Use Community Checklists: Utilize existing reproducibility checklists, such as the one provided by npj Computational Materials, to guide your research and reporting practices [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Generalization of Predictive Models

| # | Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define Applicability Domain | Explicitly map the chemical, structural, or processing space covered by your training data. | A clear boundary for reliable model predictions. |

| 2 | Implement Rigorous Validation | Use cross-validation methods like leave-one-cluster-out that test the model on chemically distinct data, not just random splits [1]. | A more realistic estimate of model performance on new data. |

| 3 | Perform Data Auditing | Check for and correct biases, outliers, and mislabeled data points in the training set. | A cleaner, more robust training dataset. |

| 4 | Report Uncertainty | Quantify and report prediction uncertainties for new data points, especially those near the edge of the applicability domain. | Informed and cautious interpretation of model outputs. |

Issue: Managing and Standardizing Heterogeneous Data

| # | Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adopt Standard Schemas | Use community-accepted data schemas (e.g., those from NOMAD, Materials Project) from the start of your project [1] [2]. | Consistent, interoperable data that is easier to share and integrate. |

| 2 | Use Persistent Identifiers | Assign unique and persistent identifiers (e.g., DOIs, ORCIDs) to your datasets and yourself. | Improved data traceability, citability, and credit attribution. |

| 3 | Leverage Data Repositories | Deposit final datasets in recognized, domain-specific repositories (e.g., JARVIS, AFLOW, OQMD) instead of personal servers [1]. | Enhanced data longevity, preservation, and community access. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standardized Workflow for Data-Driven Materials Characterization

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for generating standardized, machine-learning-ready data from materials characterization experiments.

Objective

To systematically characterize a material and produce a structured, annotated dataset suitable for upload to a materials data repository and subsequent data-driven analysis.

Experimental Workflow

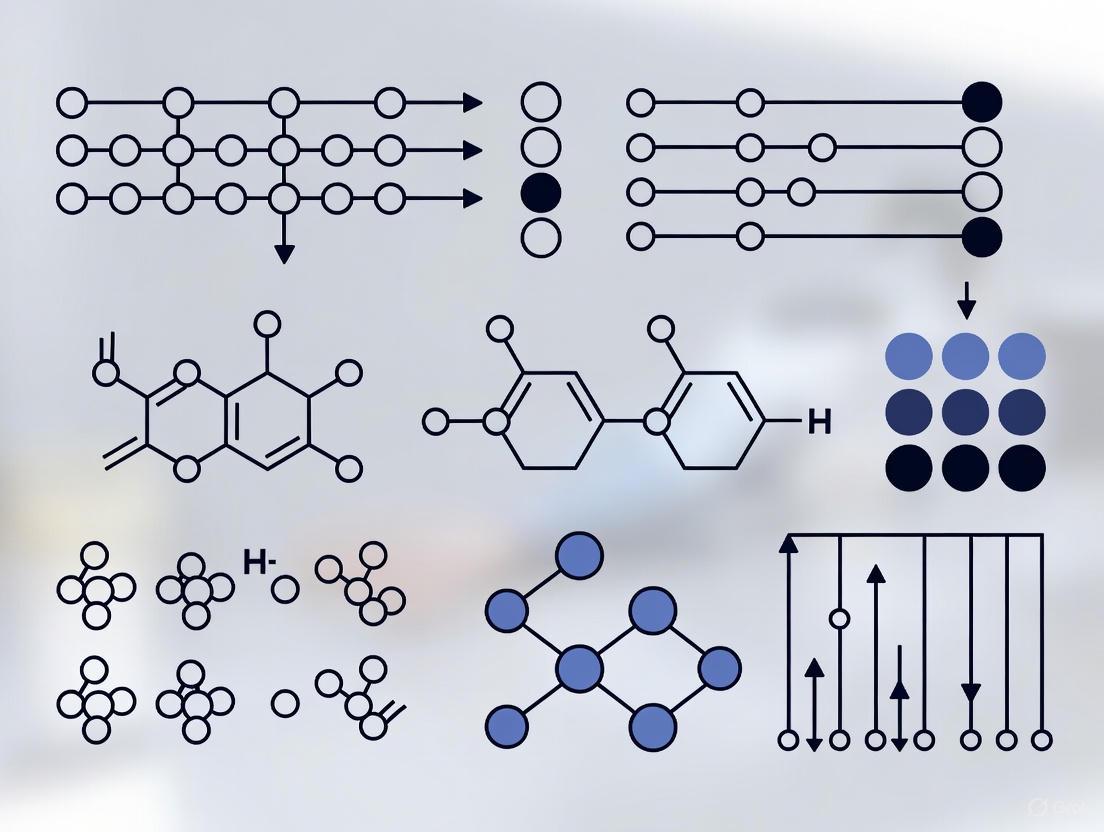

The following diagram illustrates the standardized data generation and management process:

Materials and Reagents

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Open Data Repositories (e.g., NOMAD, Materials Project, JARVIS) | Provide curated datasets for model training and benchmarking; serve as platforms for sharing research outputs [1]. |

| Machine Learning Software (e.g., scikit-learn, PyTorch, JAX) | Enable the development of predictive models to uncover hidden structure-property relationships from data [1]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Automated synthesis and characterization systems that generate large, consistent datasets required for robust data-driven analysis. |

| Computational Simulation Codes (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, LAMMPS) | Generate ab initio data to supplement experimental results and expand the available feature space [1]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation & Metadata Recording:

- Prepare the material sample according to your established synthesis protocol.

- Crucially, record all relevant metadata in a structured digital log (e.g., a spreadsheet or database). This must include:

- Precursor identities, concentrations, and purities.

- Synthesis conditions (temperature, time, pressure, atmosphere).

- Sample history (post-processing, aging).

Data Acquisition:

- Perform the characterization (e.g., XRD, SEM, spectroscopy).

- Save raw output files in non-proprietary, open formats (e.g., .txt, .csv, .cif) whenever possible.

- Automate data collection where feasible to minimize human error and increase throughput.

Data Curation & Standardization:

- Convert raw data into a structured format using a community schema.

- Annotate the data with the previously recorded metadata.

- Perform unit conversions to SI units where necessary.

- Include a clear text description of the data and the experimental conditions.

Data Repository Upload:

- Choose an appropriate public repository (e.g., NOMAD, Materials Project).

- Upload the structured dataset, ensuring all required metadata fields are completed.

- Obtain a persistent identifier (e.g., DOI) for your dataset.

Data Presentation: Key Quantitative Standards for Data Submissions

To ensure interoperability and reusability, the following data standards should be adhered to when preparing datasets for submission.

Table 1: Minimum Required Metadata for Experimental Datasets

| Metadata Field | Data Type | Description | Example Entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Composition | String | Chemical formula of the sample. | "SiO2", "Ti-6Al-4V" |

| Synthesis Method | Categorical | Technique used for sample preparation. | "Solid-State Reaction", "Chemical Vapor Deposition" |

| Characterization Technique | Categorical | Method used for measurement. | "X-ray Diffraction", "N2 Physisorption" |

| Measurement Conditions | Key-Value Pairs | Relevant environmental parameters. | "Temperature: 298 K", "Pressure: 1 atm" |

| Data License | Categorical | Usage rights for the dataset. | "CC BY 4.0" |

Table 2: Machine Learning Model Reporting Standards

| Item to Report | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Source | Repository name and dataset ID. | Ensures traceability and allows for assessment of data quality and potential biases [1]. |

| Model Architecture & Hyperparameters | Full technical description. | Enables model reproduction and verification [1]. |

| Applicability Domain | Description of the chemical/processing space the model was trained on. | Prevents misuse of the model on out-of-distribution samples and clarifies limitations [1]. |

| Performance Metrics | e.g., RMSE, MAE, R², with standard deviations from cross-validation. | Provides a standardized measure of model accuracy and robustness. |

FAQs on Open Science Implementation

What are the core aims of the Open Science movement? The Open Science movement aims to enhance the accessibility, transparency, and rigor of scientific publication. Its key focus is on improving the reproducibility and replication of research findings. This is often guided by frameworks like the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines, which include standards for data, code, materials, and study pre-registration [3].

I'm new to Open Science. What is the simplest way to start making my research more open? A great first step is to apply for Open Science Badges. These are visual icons displayed on your published article that signal to readers that your data, materials, or pre-registration plans are publicly available in a persistent location. They are an effective tool for incentivizing and recognizing open practices [3].

My data is very complex. How can I manage it to ensure others can understand and use it? Research Data Management (RDM) is the answer. RDM involves activities and strategies for the storage, organization, and description of data throughout the research lifecycle. This includes [4]:

- Using standardized file names and directory structures.

- Maintaining thorough documentation (e.g., protocols, data dictionaries).

- Formatting data according to accepted community standards. Proper RDM ensures usability for your team and the broader community, which is a foundation for open science and reproducibility [4].

What is a Data Availability Statement, and what must it include? A Data Availability Statement is a section in your article that describes the underlying data. It must include [5]:

- The name of the repository where the data is deposited.

- A persistent identifier (like a DOI or accession number) for the dataset.

- A brief description of the dataset's contents.

- A statement of the open license (e.g., CC0, CC-BY 4.0) applied to the data.

My data cannot be shared openly for ethical reasons. What should I do? You can use a controlled-access repository. These repositories restrict who can access the data and for what purposes. Your Data Availability Statement should clearly explain the reason for the restriction and the process for other researchers to request access [5].

Troubleshooting Common Open Science Workflows

Problem: Choosing a Repository for Data Deposit Selecting an appropriate data repository is a common point of confusion. The table below outlines the main types and when to use them.

| Repository Type | Description | Ideal For | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discipline-Specific | Community-recognized repositories for specific data types. | Data types with established community standards (e.g., genomic, crystallographic). | PRIDE (for proteomics), GenBank (for sequences) [5]. |

| Generalist | Repositories that accept data from any field of research. | When no discipline-specific repository exists. | Figshare, Zenodo [5]. |

| Institutional | Repositories provided by a university or research institution. | Affiliating your work with your institution; often integrated with other services. | CWRU's OSF, university data archives [6]. |

| Controlled-Access | Repositories that manage and vet data access requests. | Sensitive data that cannot be shared openly (e.g., human subject data). | LSHTM Data Compass [5]. |

Problem: Managing and Sharing Large or Complex Projects For complex projects involving code, documents, and data, a project management platform can be more effective than a simple repository.

- Solution: Use a platform like the Open Science Framework (OSF). OSF provides a cloud-based hub to store, share, and version-control all research materials. It integrates with services you may already use, like Google Drive, Box, and GitHub, allowing you to manage workflows in one place [6].

- Best Practices:

- Create separate components within your OSF project for different parts of your research (e.g., "Survey Data," "Analysis Code," "Manuscript Drafts") to stay organized [6].

- Use the version control feature to track changes to files automatically [6].

- Pre-register your study on OSF to create a time-stamped record of your research plan [3].

Problem: Ensuring Software and Analysis Code is Reproducible Sharing code is a key part of open science, but it requires specific steps to be reusable.

- Solution: Archive your code in a repository that provides a persistent identifier.

- Deposit your source code in a version control system like GitHub.

- Create a public registration or use a service like Zenodo to obtain a DOI for the specific version of the code used in your publication.

- Apply an OSI-approved open source license or a CC-BY 4.0 license to the code [5].

- What to Include: In your manuscript, provide a Software or Code Availability Statement with the DOI, a link to the code, and the license information [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For research focused on materials data standardization, certain tools and reagents are fundamental. The following table details key items and their functions in ensuring reproducible and well-documented experiments.

| Item / Reagent | Function & Importance in Standardization |

|---|---|

| Persistent Identifier (DOI, RRID) | Uniquely identifies a dataset, antibody, or software tool on the web. Critical for unambiguous citation and retrieval, ensuring everyone works with the exact same resource [5]. |

| Standardized Metadata Schema | A structured set of fields for describing your data (e.g., author, methods, parameters). Ensures data is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) for your team and others [4]. |

| Open Science Framework (OSF) | A free, cloud-based project management platform. Integrates storage, collaboration, and sharing of data, code, and documents, streamlining the open research workflow [6]. |

| Version Control (e.g., Git) | Tracks all changes to code and documentation. Essential for maintaining a record of who changed what and when, which is a cornerstone of computational reproducibility [4]. |

| Research Resource Identifier (RRID) | A unique ID for research resources like antibodies, cell lines, and software. Prevents ambiguity and improves reproducibility by precisely specifying the tools used in your methods section [5]. |

Experimental Workflow for an Open Science Project

The diagram below visualizes the key stages of a research project that adheres to open science mandates, from planning through to publication and sharing.

Data Management and Open Science Activities

The following table maps specific activities that support data management, reproducibility, and open science across the different stages of a research effort [4].

| Project Planning | Data Collection & Analysis | Data Publication & Sharing |

|---|---|---|

| Data Management Planning (e.g., creating a DMP) [4]. | Saving & backing up files [4]. | Assigning persistent identifiers (e.g., DOI) [6]. |

| Planning for open (e.g., including data sharing in consent forms) [4]. | Using open source tools [4]. | Sharing data & code in a repository [5]. |

| Preregistering study aims and methods [3]. | Using transparent methods and protocols [4]. | Publishing research reports openly (e.g., open access) [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Veracity

Why is my data producing unreliable predictive models?

Inaccurate or low-veracity data is a primary cause of model failure. This often stems from incomplete records, inconsistent formatting, or measurement errors that corrupt your training datasets [7] [8].

Detailed Methodology for Data Accuracy Testing

- Define Accuracy Requirements: Establish acceptable error rates, tolerances, and thresholds for critical data elements like material properties or synthesis parameters [7].

- Create Test Cases: Develop specific tests to verify data meets these requirements. For computational data, compare results against known accurate sources or high-fidelity benchmark calculations [7].

- Utilize Statistical Methods and Profiling: Employ statistical analysis and data profiling tools to identify outliers, anomalies, and values that fall outside expected physical or chemical ranges [7].

- Implement Automated Validation: Where possible, integrate automated validation checks into data pipelines to check for data type, range restrictions, and format compliance as new data is ingested [7].

How can I verify the completeness of my materials dataset?

Data completeness testing ensures all required data is present and no critical information is missing, which is vital for reproducible research [7].

Experimental Protocol for Completeness Verification

- Identify Mandatory Fields: Define all required data attributes for your experiments. For a materials synthesis dataset, this might include precursor concentrations, temperature, time, and environmental conditions [7].

- Profile Datasets: Systematically check all records and fields to verify they are populated with appropriate values. Scan for placeholders like "NULL" or "TBD" that indicate missing information [7].

- Check for Critical Gaps: Ensure no essential data is missing that could lead to misinformed conclusions or failed reproduction attempts [8].

Table: Key Data Veracity Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Research | Corrective Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Data Incompleteness [7] | Leads to biased models and inability to reproduce synthesis conditions. | Implement data completeness testing to identify and fill critical gaps in records [7]. |

| Data Inconsistency [7] | Prevents combining datasets from multiple labs or experiments, hindering collaboration. | Apply data consistency testing to enforce uniform formats, units, and naming conventions [7] [9]. |

| Measurement & Human Error [8] | Introduces noise and inaccuracies, corrupting the fundamental data for analysis. | Conduct data accuracy testing against known standards and use automated validation to reduce manual entry errors [7] [8]. |

Diagram: A Framework for Diagnosing and Addressing Data Veracity Issues

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Integration

Why can't I combine computational and experimental data effectively?

A lack of interoperability is the most common barrier. This occurs when datasets from different sources (e.g., simulations, lab equipment) use different formats, naming conventions, or lack the necessary metadata to be meaningfully combined [10].

Detailed Methodology for Achieving Interoperability

- Adopt a Shared Metadata Schema: Implement a community-standard metadata schema to describe your data. Metadata are attributes necessary to fully characterize, reproduce, and interpret your data [10].

- Use Formal Ontologies: Where available, use formal, accessible, and broadly applicable languages (ontologies) for knowledge representation. This ensures that terms like "bandgap" or "yield strength" are unambiguous across datasets [10].

- Ensure Full Provenance Tracking: Record the complete logical sequence of operations (the workflow) that produced the data. For a calculation, this includes all input parameters; for an experiment, it includes the detailed synthesis and measurement protocol [10].

How do I handle duplicate or conflicting data entries during integration?

Duplicate and inconsistently formatted data for the same material or component is a major source of chaos, leading to procurement errors in industry and flawed analysis in research [9].

Experimental Protocol for Data Deduplication and Standardization

- Identify Duplicates: Use data matching techniques to compare records from different sources. Look for the same entity (e.g., a specific chemical compound or spare part) represented with different names or formats [7] [9].

- Apply Standardization Rules: Define and enforce a single taxonomy for data entry. This includes standardizing units of measure, chemical nomenclature, and attribute ordering [9].

- Merge and Cleanse: Create a single, master record for each unique entity, merging information from duplicates after verification. Flag or remove obsolete records to maintain a clean dataset [9].

Table: Data Integration Hurdles and Standardization Strategies

| Hurdle | Consequence | Standardization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Incompatible Formats [10] | Creates data silos; prevents cross-disciplinary analysis. | Adopt FAIR-compliant metadata schemas and standard file formats for data exchange [10]. |

| Inconsistent Naming [9] | The same item appears as multiple entries, inflating inventory costs and confusing analysis. | Implement and enforce a unified taxonomy (e.g., UNSPSC) for all material descriptions [9]. |

| Missing Provenance [10] | Data cannot be reproduced or trusted for high-stakes decisions. | Record full workflow and provenance metadata for all data objects [10]. |

Diagram: The Data Integration Pathway from Multiple Silos to a Unified Resource

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Longevity

How can I ensure my data remains usable in 5-10 years?

The core challenge is preserving Reusability and Accessibility as technology evolves. Data that is "recyclable" or "repurposable" for future, unanticipated research questions provides long-term value [10].

Detailed Methodology for Ensuring Data Longevity

- Assign Persistent Identifiers (PIDs): Use Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) or permanent Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) for your datasets. This ensures they can be reliably found and cited long after project completion [10].

- Use Open and Documented Formats: Store data in non-proprietary, well-documented file formats. Avoid formats tied to specific, potentially obsolete, commercial software versions [10].

- Create Rich Metadata: Describe your data with comprehensive metadata that answers the "wh- questions": who, what, when, where, why, and how. This context is critical for others (including your future self) to understand and use the data correctly [10].

- Register in Searchable Resources: Deposit your data and its metadata in certified repositories or metadata registries (MDRs). These resources are designed for long-term preservation and make data findable [10].

What is the difference between data longevity and just backing up files?

While backups protect against data loss, longevity focuses on usability. A file from a 20-year-old proprietary program might be restored from a backup but remain unopenable. Longevity ensures the data and its meaning can be accessed and interpreted.

Experimental Protocol for a Longevity Audit

- Assess File Formats: Inventory all data formats in your archive. Flag proprietary or obscure formats for migration to open, standard alternatives.

- Check Metadata Completeness: Evaluate a sample of datasets against the FAIR principles. Can a colleague unfamiliar with the project find, access, and understand how to use this data?

- Verify Access Mechanisms: Test the APIs or access protocols for your stored data. Ensure they are still functional and well-documented [10].

Table: Threats to Data Longevity and Preservation Tactics

| Threat | Risk | Preservation Tactic |

|---|---|---|

| Format Obsolescence | Data becomes unreadable by modern software. | Use open, well-documented file formats for all data and metadata [10]. |

| Loss of Context [10] | Data exists but is incomprehensible, defeating repurposing. | Create rich metadata with full provenance, detailing the "who, what, when, where, why, and how" [10]. |

| Link Rot / Loss of Findability | Data exists in storage but cannot be located or accessed. | Assign Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) and register data in searchable repositories [10]. |

Diagram: The Data Longevity Lifecycle from Creation to Future Reuse

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Resources for Managing Materials Informatics Data

| Tool or Resource | Function | Relevance to Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| FAIR Data Principles [10] | A set of guiding principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) to make data shareable and machine-actionable. | Provides the foundational framework for addressing Integration and Longevity across all data management activities. |

| Formal Ontologies [10] | Formal, accessible, and shared languages for knowledge representation that define terms and their relationships unambiguously. | Critical for Integration, ensuring that data from different sources uses the same precise vocabulary. |

| Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) [10] | Permanent, unique identifiers like Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) that persistently point to a digital object. | Solves Longevity challenges by ensuring data remains findable and citable indefinitely, beyond the life of a specific web link. |

| Metadata Schema / Registry [10] | A structured framework for recording metadata, often managed within a metadata registry (MDR) that manages semantics and relationships. | The primary tool for Veracity and Longevity, providing the necessary context to understand, trust, and reuse data. |

| NOMAD Laboratory [10] | A central repository and set of tools for storing, sharing, and processing computational materials science data. | An exemplar platform implementing FAIR principles, helping to solve Integration and Longevity for computational data. |

| Citrine Informatics / SaaS Platforms [11] | Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) platforms that provide specialized AI-driven tools for materials data management and prediction. | Offers turnkey solutions for Veracity (through data validation) and Integration (by combining diverse data sources). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Materials Data Standardization

This technical support center provides practical solutions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals encountering issues in materials data standardization. The following guides and FAQs address common challenges in implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles and ontologies within a collaborative ecosystem [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our research group generates large volumes of synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD) data, but other labs struggle to understand our variable naming conventions. What is a sustainable solution?

A1: Implement a community-developed domain ontology. The lack of terminological consistency is a known challenge in SXRD, where data formats are highly multimodal (e.g., images, spectra, diffractograms) and naming conventions vary [12]. Adopting a formal ontology adds a layer of semantic description that can map multiple terms to the same concept, accommodating varying terminology while promoting consistency. The MDS-Onto framework provides an automated way to build such ontologies, which can be serialized into linked data formats like JSON-LD for easy understanding and modification by the scientific community [12].

Q2: When transferring photovoltaic (PV) assets, how can we prevent critical performance data loss and maintain the link between raw data and what it represents?

A2: Utilize an ontology to unify terminology across the PV supply chain. The frequent transfer of PV assets often leads to data loss, compounded by non-uniform instrumentation and incompatible software input formats (e.g., pvlib-python, PVSyst, SAM) [12]. A domain ontology for photovoltaics provides a standardized semantic model to retain the source and conditions of measurements (e.g., irradiance, temperature), ensuring that data like open-circuit voltage (Voc) and short-circuit current (Isc) are accurately interpreted long after the asset has changed hands [12].

Q3: What is the first step toward building a Knowledge Graph (KG) for our materials data to enable advanced reasoning?

A3: Developing a robust ontology is the crucial first step. A Knowledge Graph is a graph data structure that uses an ontology as its schema to organize information [12]. The ontology defines the entities (nodes) and relationships (edges) within the graph. The flexibility of this structure allows new data to be incorporated easily, and the semantic relationships enable the KG to perform inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning to derive implicit knowledge [12].

Q4: How can we make our research data simultaneously discoverable by both academic and industrial partners?

A4: Participate in a federated registry system that uses a controlled vocabulary and metadata schema. Initiatives like the International Materials Resource Registries (IMRR) aim to solve this exact problem [13]. By describing your resource (e.g., data repository, web service) using a common metadata schema that separates generic metadata from domain-specific metadata, you enable global discovery across institutional and sectoral boundaries [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Metadata Schema Across Collaborating Institutions

Problem: Different groups use different metadata fields and definitions, making combined data analysis difficult and error-prone.

Solution: Adopt and extend a core metadata schema.

Methodology:

- Identify a Core Schema: Start with a core, generic metadata schema. The IMRR initiative, for example, leverages existing schemas like Dublin Core and DataCite for generic concepts [13].

- Incorporate Domain Metadata: Add an "Applicability" section to the resource description for domain-specific metadata. A resource description can have multiple such sections for different domains (e.g., materials science, chemistry) using XML namespaces to avoid semantic collisions [13].

- Ensure Extensibility: The schema should be designed for evolution through pluggable extensions, allowing it to adapt to new resource types and scientific domains without disrupting existing records [13].

Validation: Use open software to validate resource description documents against the formal XML Schema definition [13].

Issue: Data and Metadata Are Not Machine-Actionable, Hindering Automated Analysis

Problem: Data files and their descriptors require manual interpretation, which is not scalable for large datasets or for use by AI/ML models.

Solution: Implement a formal ontology and serialize data using linked data formats.

Methodology:

- Ontology Positioning: Use a framework like MDS-Onto to position your domain ontology within the semantic web, connecting it to upper-level ontologies like the Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) to ensure interoperability [12].

- Template Creation: Use the ontology to create JSON-LD templates. These templates follow the variable naming conventions and hierarchical structures specified in the ontology [12].

- Data Serialization: Populate the JSON-LD templates with your experimental data and metadata. This serialization facilitates data findability and accessibility and makes the data machine-actionable [12].

Tools: The MDS-Onto framework includes a bilingual package called FAIRmaterials for ontology creation and FAIRLinked for FAIR data creation [12].

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Core Metadata Schema for Resource Discovery (Adapted from the International Materials Resource Registries model [13])

| Metadata Section | Key Elements | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | Identifier, Title | Uniquely names and references the resource. | DOI, Registry-assigned ID |

| Providers | Curator, Publisher | Identifies who is responsible for the resource. | University, Research Institute |

| Role | Resource Type | Classifies the type of resource. | Repository, Software, Database |

| Content | Subject, Description | Summarizes what the resource is about. | Keywords, Abstract |

| Access | Access URL, Rights | Explains how to access the resource. | HTTPS endpoint, License |

| Related | IsDerivedFrom, Cites | Links to other related resources. | Another dataset, Publication |

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional Computational and AI/ML-Assisted Material Models [14]

| Aspect | Traditional Computational Models | AI/ML-Assisted Models | Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | High interpretability, Physical consistency | Speed, Handling of complexity | Excellent prediction, Speed, Interpretability |

| Weaknesses | Can be slow for complex systems | May lack transparency ("black box") | Combines strengths of both approaches |

| Data Needs | Well-defined physical parameters | Large, standardized FAIR datasets | Integrated physical and data-driven inputs |

| Role in R&D | Foundation for advanced modelling | Surrogate models for rapid screening | Optimal for simulation and optimization |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Controlled Vocabulary for a Data Resource Registry

This protocol outlines the development of a controlled vocabulary to aid in the discovery of high-level data resources, as practiced by the RDA IMRR Working Group [13].

- Examine Existing Work: Review then-existing vocabularies, taxonomies, and ontologies in the target domain (e.g., materials science).

- Iterate with Experts: Collect input and refine terms through working group meetings, discussions, and workshops (e.g., VoCamp).

- Pilot and Refine: Use the vocabulary in a pilot application (e.g., a resource registry) and incorporate feedback from users registering their resources.

- Structure the Vocabulary: A three-level hierarchy of terms is often sufficient to provide specificity while minimizing the burden on those entering metadata. This can be combined with free-text keyword fields for additional detail [13].

Protocol 2: Building a Domain Ontology with the MDS-Onto Framework

This methodology describes the use of the MDS-Onto framework for creating interoperable ontologies in Materials Data Science [12].

- Framework Adoption: Utilize the MDS-Onto framework to simplify term matching by establishing a semantic bridge to the Basic Formal Ontology (BFO).

- Tool Selection: Use the FAIRmaterials package for ontology creation. The framework provides recommendations on knowledge representation language and online publication to boost findability.

- Integration and Reuse: Connect specific terms and relationships to pre-existing generalized concepts. Reuse and incorporate other relevant ontologies (e.g., ChEBI for chemical entities, NCIt for biomedical terms) if one ontology does not cover all needs.

- Generate Data Templates: Create JSON-LD templates from the ontology to standardize data serialization and enable the population of data and metadata using the established naming conventions.

Mandatory Visualizations

Workflow for Federated Resource Discovery

This diagram illustrates the logical workflow and architecture for discovering a data resource through a federated registry system that uses a shared metadata schema [13].

Ontology Development and Data Serialization Pathway

This diagram visualizes the pathway from ontology development to the creation of FAIR data using a structured framework, leading to the population of a Knowledge Graph [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key frameworks, tools, and platforms essential for materials data standardization research.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| MDS-Onto Framework | Ontology Framework | Provides an automated, unified framework for developing interoperable ontologies in Materials Data Science, simplifying term matching to the Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) [12]. |

| FAIRmaterials | Software Package | A bilingual package within MDS-Onto specifically designed for ontology creation [12]. |

| FAIRLinked | Software Package | A package within MDS-Onto for the creation of FAIR data [12]. |

| International Materials Resource Registries (IMRR) | Metadata Schema & Vocabulary | A controlled vocabulary and XML metadata schema designed to enable the discovery of materials data resources through a federated registry system [13]. |

| JSON-LD (JavaScript Object Notation for Linked Data) | Data Format | A linked data format for serializing data and metadata based on an ontology, making it machine-actionable and easier to share [12]. |

| Hybrid AI/ML & Physics-Based Models | Modeling Approach | Combines the interpretability of traditional physics-based models with the speed and complexity-handling of AI/ML, showing excellent results in prediction and optimization [14]. |

Technical Support & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

What does the "Ultimate Search Engine" do? The Materials Ultimate Search Engine (MUSE) is designed to allow researchers to search across a sea of curated academic and materials data content, not just one library's holdings. It uses powerful federated search to comb every content source you choose to curate, from scholarly journals and library archives to premium publisher resources and open-access materials, delivering a single, interactive list of rich results [15].

Why are my search results not showing data from our proprietary internal database? MUSE allows administrators to design content discovery solutions tailored to unique needs. If an internal source is missing, it may not yet be added to your curated list. Please contact your system administrator to ensure your proprietary database, along with other relevant sources like digital repositories and native databases, is configured within the MUSE discovery solution [15].

How does MUSE ensure the quality and comparability of materials data from different sources? MUSE is built upon the principle of data standardization, which is crucial for ensuring data quality, interoperability, and reuse. The platform incorporates standards and best practices for creating robust material datasets. This includes establishing requirements for data pedigree, focusing on process-structure-property relationships, and implementing FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) to maximize the utility of research data [16] [17].

A key standard for data submission is missing from the system. How can I request its inclusion? MUSE development is aligned with industry consortia like the Consortium for Materials Data and Standardization (CMDS), which works to accelerate standards adoption. The platform's data management system is optimized to incorporate common data dictionaries and exchange formats. Please submit a request for new standards through our support portal, and our team will evaluate it against our roadmap and ongoing standards development efforts [16].

What should I do if I encounter an authentication error when accessing a licensed journal through MUSE? MUSE employs a powerful proxy to manage authentication handshakes with various content sources. If you encounter an error, please try clearing your browser cache and cookies first. If the issue persists, report it to the support team, specifying the resource you were trying to access and the exact error message received [15].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Search Result Relevance | Overly broad search terms; Filters not applied. | Use more specific keywords and utilize the robust filtering options to narrow results by date, resource type, or subject. |

| Cannot Access Licensed Content | Expired institutional subscription; Proxy authentication failure. | Confirm your institution's subscription status. If valid, report the authentication error to technical support. |

| Inconsistent Data Display | Non-standardized data formats from source systems. | MUSE normalizes data, but legacy system variations can cause issues. Report specific instances for our team to address. |

| Slow Search Performance | High server load; Complex query processing vast sources. | Refine search query. Performance is optimized for comprehensive coverage across all curated content sources. |

| Missing Data from a Specific Lab System | Data source not integrated into the MUSE platform. | Request a new source integration through the official channel. Our team evaluates all new source requests. |

Data Standards and Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Data on Standardization Benefits

Adopting common data standards, such as those developed by the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) in clinical research, provides significant, measurable benefits to the research process [18]. The following table summarizes key quantitative advantages:

| Metric | Improvement with Standardization | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Study Start-up Time | Reduced by 70% to 90% | Using standard case report forms and validation documents [17] |

| Data Reproducibility | Over 70% of researchers failed to reproduce others' experiments | Survey highlights need for standards to ensure traceability [17] |

| Regulatory Submission Efficiency | Accelerated review and audit processes | CDISC-compliant data is easily navigable, reducing review time [18] |

| Data Management Costs | Significant long-term reduction | Mitigates time needed for data cleansing, validation, and integration [18] |

| ROI on Materials Data | Minimum 10:1 return on investment | Shared funding model for standardized data generation [16] |

Protocol for Establishing a Standardized Materials Dataset

This detailed methodology outlines the steps for generating a high-pedigree, standardized materials dataset suitable for ingestion and use within the MUSE platform, based on best practices from industry consortia [16].

Objective: To create a robust, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) dataset that captures the process-structure-property relationships of a material.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Standardized Data Management System | A secure platform for storing and managing data throughout its lifecycle, ensuring interoperability and implementing FAIR principles [16]. |

| Common Data Dictionary | Defines the precise terminology and format for all data elements (e.g., "ultimatetensilestrength" in MPa), ensuring consistency across datasets [16]. |

| Material Pedigree Standards | Guidelines for documenting the quality and origin of the material, including feedstock source, lot number, and material certification [16]. |

| In-situ Process Monitoring Equipment | Sensors (e.g., thermal cameras, photodiodes) to collect real-time data during material processing for quality assurance and defect detection [16]. |

| Data Equivalency Protocols | Methods for determining if data generated from different machines or processes can be considered equivalent based on material structure [16]. |

Methodology:

Project Scoping and Variable Identification:

- Define the specific material and process under investigation (e.g., Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Ti-6Al-4V).

- Identify and document the key independent (e.g., laser power, scan speed) and dependent (e.g., yield strength, porosity, microstructure) variables using the common data dictionary.

Design of Experiment (DOE):

- Develop a statistically designed experiment to efficiently explore the effect of process parameters on material structure and properties.

- Document the DOE matrix in a standardized digital format.

Sample Fabrication and In-situ Data Capture:

- Fabricate test specimens according to the DOE.

- Simultaneously, collect in-situ process monitoring data (e.g., melt pool morphology, thermal history) using the calibrated monitoring equipment. This data is crucial for linking the process to the resulting structure.

Post-Process Analysis and Metrology:

- Perform necessary post-processing (e.g., stress relief, HIP, surface finishing) as defined by the standard protocol.

- Conduct metrology to characterize the material's structure. This may include:

- Archival of all raw and processed data into the Data Management System with strict adherence to the common data dictionary.

Mechanical Property Testing:

- Perform mechanical testing (e.g., tensile, fatigue, hardness) according to relevant ASTM or ISO standards.

- Record all raw data, specimen geometry, and test conditions in the standardized format.

Data Curation, Integration, and Pedigree Assignment:

- Curate all data—from DOE parameters, in-situ sensor data, metrology results, to mechanical property data—into the unified Data Management System.

- Establish explicit links between the process parameters, the resulting material structure, and the final properties (PSP linkages).

- Assign a data pedigree level based on the completeness of metadata and adherence to the standard protocol.

Data Submission and Sharing:

- Upon final validation, the dataset is transferred to the MUSE platform or a member-only Data Management System, where it becomes a searchable, high-pedigree resource for the community [16].

Workflow and System Diagrams

MUSE Data Search and Integration Workflow

This diagram illustrates the logical flow of a user query through the MUSE system, showing how disparate data sources are integrated and standardized to deliver unified results.

Process-Structure-Property Relationship

This diagram visualizes the core logical relationship in materials science that the MUSE vision seeks to standardize and make searchable, linking manufacturing processes to material microstructure and final performance properties.

Building Your Standardization Framework: A Step-by-Step Blueprint

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common types of data sources in materials science? Researchers typically work with a combination of computational data from high-throughput simulations (e.g., density functional theory calculations) and experimental data from synthesis and characterization. A primary challenge is the heterogeneity in how this data is formatted and stored across different sources and research groups [2] [19].

My data is stored in custom file formats. How can I standardize it? The key is to adopt or develop a unified storage specification. This involves creating a framework that can automatically extract data from diverse formats—including discrete calculation files and existing databases—and map them to a standardized schema, often using flexible, document-oriented databases like MongoDB [19].

Why is integrating experimental and computational data so difficult? Experimental and computational data are often stored with different structures, levels of detail, and metadata. This creates a data integration gap. Overcoming it requires standardized metadata descriptors and data collection frameworks that can handle both data types from the outset [2].

How can I assess the quality of a dataset from a public repository? Always check for completeness and veracity. Scrutinize the associated metadata, the clarity of the data collection methodology, and any validation steps described. Be aware that models trained on such data can suffer from performance drops when applied to data outside their original training distribution, highlighting the need for rigorous validation [1].

Troubleshooting Common Data Collection and Standardization Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Data Formats | Use of different software and legacy systems generating non-standard outputs. | Implement a data collection framework that supports automatic extraction and conversion of multi-source heterogeneous data into a unified format [19]. |

| Poor Data Veracity | Incomplete metadata, unclear experimental protocols, or lack of validation. | Adopt a checklist for data reporting. Ensure clear descriptions of models, data, and training procedures are documented and shared [1]. |

| Difficulty Reusing Historical Data | Data was stored without a standard schema, making fusion and analysis difficult. | Map historical data to a new, comprehensive storage standard. Frameworks exist to assist in the automated analysis and extraction of raw data from various legacy formats [19]. |

| Limited Domain Applicability of Models | Predictive models are trained on data that does not represent the broader materials space. | Rigorously validate models on out-of-distribution data. Use techniques that assess model uncertainty and report the expected domain of applicability [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Automated Collection of Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data

This methodology outlines the steps for creating a standardized data collection pipeline.

1. Principle To overcome inconsistencies in materials data formats and storage methods by establishing a automated framework for the extraction, storage, and analysis of data from diverse sources, enabling efficient data fusion and reuse [19].

2. Materials and Reagents

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| MongoDB (NoSQL Database) | Serves as the core repository for standardized data, accommodating structured documents and offering robust query functions for large-scale datasets [19]. |

| Computational Data Files (e.g., VASP output) | Provide raw, high-throughput ab initio calculation results as a primary data source for population of the database [19]. |

| Existing Databases (e.g., OQMD) | Act as a secondary, structured data source that must be mapped and integrated into the new unified storage schema [19]. |

| Data Collection Framework | The custom software that performs automated extraction from source files and databases, transforms the data into the standard format, and manages its storage in MongoDB [19]. |

3. Procedure

- Source Evaluation: Determine if the data source is a structured database or a set of discrete calculation files [19].

- Data Extraction: Use the framework's specific extractors to parse the source data. For database sources, this may involve querying APIs. For files, it involves reading and interpreting specific output formats [19].

- Data Storage: The extracted data is transformed and stored in BSON format (Binary JSON) within MongoDB according to the pre-defined, unified schema [19].

- Data Analysis and Serving: The stored data is made accessible through a user-friendly interface for querying, retrieval, and use in downstream data-driven research, such as machine learning [19].

4. Data Analysis The final stored data should be validated for accuracy and completeness. Researchers can then access it for machine learning applications, property prediction, and materials discovery, significantly improving research efficiency [19].

Research Dataflow and Stakeholder Ecosystem

The following diagram illustrates the flow of data from its generation to its ultimate use, and the ecosystem of stakeholders involved in materials data science.

Critical Data Elements for Standardization

The table below summarizes the key elements that must be standardized to ensure data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR).

| Category | Critical Element | Description & Standardization Need |

|---|---|---|

| Material Identity | Atomic Structure & Composition | Crystalline structure (space group), chemical formula, and atomic coordinates must be explicitly defined using standard crystallographic information file (CIF) conventions or similar. |

| Provenance | Simulation Parameters & Experimental Conditions | For computational data: software, version, functional, convergence criteria. For experimental: synthesis method, temperature, pressure. Essential for reproducibility [1]. |

| Property Data | Calculated or Measured Properties | Properties (e.g., band gap, elastic tensor) must be reported with units and associated uncertainty. The method of measurement or calculation should be referenced. |

| Metadata | Data Collection & Processing Workflow | A complete description of the data flow, from raw data generation to the final reported value, including any filtering or analysis steps. This is a core component of modern data infrastructures [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a Common Data Model (CDM) and a Data Dictionary? A Common Data Model (CDM) is a standardized framework that defines the structure, format, and relationships of data tables within a database. It ensures that data from disparate sources is organized consistently. For example, the OMOP CDM is used for observational health data, providing a standard schema for patient records, drug exposures, and condition occurrences [20].

A Data Dictionary is a centralized repository of metadata that defines and describes the content of the data within the CDM. It provides detailed information about each data element, including its name, definition, data type, allowable values (controlled terminology), and its relationship to other elements [21]. Think of the CDM as the skeleton of your database and the data dictionary as the comprehensive user manual that explains every part of it.

FAQ 2: We are experiencing 'data standards fatigue' with the number of evolving standards. How can we manage this? The feeling of being overwhelmed by the continuous introduction and evolution of data standards is a common challenge, often termed "Data Standards Fatigue" [22]. To manage this:

- Identify Core Standards: Catalogue the standards relevant to your work and identify the core, non-negotiable ones to focus your efforts. For regulatory submissions, this includes standards like CDISC SDTM and ADaM [23].

- Adopt a Modular Governance Framework: Implement an agile data governance framework that can evolve alongside technological advancements. This helps manage issues of data ownership, quality, and compliance without stifling innovation [22].

- Leverage Automation and AI: Investigate AI-driven solutions to automate data standardization and validation. This reduces manual effort, minimizes errors, and can help bootstrap the standardization process by suggesting reusable data models [22].

FAQ 3: During the ETL process, how do we handle source data that does not conform to our chosen controlled terminologies? This is a central task in the ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process. The solution involves systematic mapping.

- Systematic Scanning and Mapping: Perform a thorough scan of your raw source database. Don't rely solely on documentation; verify by looking at the data itself [20].

- Develop Business Logic: Create detailed mapping specifications at the value level. This document defines how each source value is translated into a standard term from your chosen dictionary (e.g., MedDRA for adverse events or CDISC Controlled Terminology for clinical data) [21].

- Quality Control: Implement robust quality control measures, including regular audits and validation checks of the mapped data to ensure accuracy and consistency [21]. This process is iterative and should be documented comprehensively.

FAQ 4: What are the most critical success factors for a cross-functional team building a CDM? Success relies on a collaborative, interdisciplinary approach. Key factors include [20]:

- A Team, Not a Hero: A successful ETL and CDM build requires a village. Do not have one person attempt to do it all alone. Foster team design, team implementation, and team testing.

- Local Knowledge and Clinical Understanding: The team must include individuals with deep knowledge of the source data's capture process and clinicians who understand the medical context of the data.

- Thorough Documentation: Document early and often. The more details you capture in your data dictionary and ETL specifications, the fewer iterations and rework you will face later.

- Complete Design Before Implementation: A common pitfall is starting to code the ETL before the design is complete. Comprehensive specifications save unnecessary thrash during implementation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Data Leading to Failed Regulatory Compliance Checks

- Symptoms: Validation errors in submission packages, inability to combine datasets from different studies, regulatory queries about data quality.

- Root Cause: Lack of a unified data dictionary and enforced CDM, leading to inconsistent use of variables, formats, and controlled terminologies across studies.

- Solution:

- Establish a Centralized Data Dictionary: Develop a single source of truth that defines all data elements. For clinical data, this should align with standards like CDASH for data collection and SDTM for tabulation [23].

- Implement a Governance Council: Form a cross-functional governance body with representatives from data management, biostatistics, and clinical operations to oversee and approve all changes to the dictionary [22].

- Enforce Use of Controlled Terminology: Mandate the use of standardized code lists (e.g., CDISC CT) for all relevant data points to ensure consistency and avoid ambiguity [23] [21].

- Utilize Standard Data Exchange Formats: For regulatory submissions, use standardized metadata formats like Define-XML to describe the structure and content of your datasets, which is a requirement for agencies like the FDA and PMDA [23].

Problem: Inability to Integrate or Analyze Data from Multiple Research Studies

- Symptoms: High effort required to "map" one study's data to another, difficulty performing meta-analyses, low trust in combined results due to presumed data loss or misrepresentation.

- Root Cause: Data silos where each study or project uses its own unique data structures and definitions, lacking a common model.

- Solution:

- Adopt a Standardized CDM: Select and implement a common data model, such as the OMOP CDM for observational data, to provide a consistent structure for all data [20].

- Implement a Systematic ETL Process: Follow a documented process to load data from source systems into the CDM. This includes training on the CDM, scanning source data, drafting business logic for table, variable, and value-level mapping, and rigorous data quality checking at every step [20].

- Apply FAIR Principles: Ensure your data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. A well-documented data dictionary and a standard CDM are foundational to achieving these principles [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions for establishing a robust data standardization framework.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Controlled Terminology (CT) | Standardized lists of allowable values (e.g., for sex: M, F, U) that ensure data consistency and are required by regulators [23] [21]. |

| Therapeutic Area Standards (TAUGs) | Extend foundational standards (like SDTM) to represent data for specific diseases, providing disease-specific metadata and implementation guidance [24] [23]. |

| Data Governance Framework | A system of authority and procedures for managing data assets, ensuring data quality, security, and compliance throughout its lifecycle [22]. |

| ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) Tools | Software applications that automate the process of extracting data from sources, transforming it to fit the CDM and dictionary rules, and loading it into the target database [20]. |

| Define-XML | A machine-readable data exchange standard that provides the metadata (data about the data) for datasets submitted to regulators, describing their structure and content [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for CDM and Dictionary Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points for establishing a Golden Record through a CDM and Data Dictionary.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between data profiling and data auditing?

Data profiling is the process of examining data from its existing sources to understand its structure, content, and quality. It involves scanning datasets to generate summary statistics that help you assess whether data is complete, accurate, and fit for your intended use [25]. Data auditing is a broader, more systematic evaluation of an organization's data assets, practices, and governance to assess their accuracy, completeness, and reliability against predefined standards and regulatory requirements [26] [27]. Profiling is often a technical first step that informs the wider audit process.

Which data quality dimensions should I prioritize for materials science data?

For materials science data, which often involves complex property measurements and compositional information, the most critical dimensions are Accuracy, Completeness, and Consistency [28].

- Accuracy: Ensures that data correctly represents the real-world material or experiment it describes; is non-negotiable for predictive modeling [28].

- Completeness: Guarantees that all necessary data points are available, which is vital for reproducibility in research [28].

- Consistency: Ensures uniformity across datasets from different experiments or sources, preventing contradictions that jeopardize reliability [28].

Our research team is new to this; what is the simplest way to start data profiling?

The most straightforward way to begin is by using automated column profiling available in modern data catalogs or dedicated tools [29]. This technique scans your data tables and provides immediate summary statistics for each column (or attribute) in your dataset [30]. You will quickly get counts of null values, data types, patterns, and basic value distributions, giving you a instant snapshot of data quality without extensive manual inspection [29].

How can I handle duplicate records of material specimens or compounds in our database?

Identifying duplicates requires fuzzy matching techniques that go beyond exact string matching, as the same material might be recorded with slight variations [31]. This process is a core function of many data profiling and cleansing tools, which use algorithms to detect non-obvious duplicates based on similarity scores [25] [32]. For example, a tool might identify that "3 Pole Contactor 32 Amp 24V DC" and "Contactor, 3P, 24VDC Coil, 32A" refer to the same item, allowing you to merge the records [31].

Troubleshooting Common Data Quality Issues

Problem: High Number of Empty Values in Critical Fields

Issue: During profiling, you discover that key measurement fields (e.g., 'tensile strength', 'thermal conductivity') have a high percentage of null or empty values [28].

Solution:

- Implement Validation at Entry: Create and enforce data entry rules that make critical fields mandatory and validate formats at the point of data generation [32].

- Conduct Root Cause Analysis: Use diagnostic analytics to understand why data is missing. Is it a process failure, equipment interface issue, or a human error? [33]

- Establish Data Quality Metrics: Continuously track the "Number of Empty Values" as a key metric for your critical data fields to monitor improvement over time [28].

Problem: Inconsistent Naming Conventions for Materials

Issue: The same material or spare part is described inconsistently across different experiments or lab sites, leading to confusion and inaccurate analysis [31].

Solution:

- Define a Standard Taxonomy: Establish and document a single, controlled vocabulary and format for naming materials and parts (e.g., following a standard like UNSPSC) [31] [32].

- Apply Data Standardization: Use automated tools to parse existing entries and convert them into the predefined, uniform format [32].

- Utilize Data Profiling for Pattern Recognition: Run cross-column profiling to identify all the different naming patterns and variations currently in use, which will inform your standardization rules [30].

Problem: Suspected Data Inconsistencies Between Source and Analysis Database

Issue: The data used for analysis in a data warehouse seems to differ from the raw data produced by laboratory instruments, causing distrust in results.

Solution:

- Check Data Transformation Logs: Review the ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process for errors. A high number of "Data Transformation Errors" often points to underlying data quality issues, such as unexpected values or formats that cause the process to fail [28].

- Perform Data Reconciliation: Use data profiling to compare a sample of the source data against the data in the target database to ensure consistency and accuracy after transfer [26].

- Map Data Lineage: Use a tool that supports data lineage to visualize the complete flow of data from its source to its final form. This helps pinpoint where in the pipeline the inconsistency is introduced [29].

Data Quality Metrics for Materials Research

The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics to measure during data profiling and auditing. Tracking these over time is essential for demonstrating improvement [28].

| Metric | Definition | Target for High Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Data to Errors Ratio [28] | Number of known errors vs. total dataset size. | Trend of fewer errors while data volume holds steady or increases. |

| Number of Empty Values [28] | Count of entries in critical fields that are null or empty. | As close to zero as possible for mandatory fields. |

| Data Transformation Error Rate [28] | Percentage of ETL/ELT processes that fail. | A low and stable percentage, ideally under 1%. |

| Duplicate Record Percentage [28] | Proportion of records that are redundant. | Minimized, with a clear downward trend after remediation. |

| Data Time-to-Value [28] | Speed at which data can be transformed into business/research value. | A shortening timeframe, indicating less manual cleanup is needed. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Systematic Data Audit

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for assessing the current state of your materials data, as part of a broader data standardization effort [26].

1. Define the Audit Objectives and Scope Clearly outline the goals. For materials research, this could be: "Ensure all experimental data for the new polymer composite series is complete, accurate, and compliant with FAIR principles before building predictive models." [26]

2. Identify and Catalog Data Sources Create an inventory of all data sources. In a research context, this includes [26]:

- Internal databases (e.g., LIMS - Laboratory Information Management System).

- Electronic Lab Notebooks.

- Instrument output files.

- External or public data sources used for benchmarking.

3. Data Profiling and Initial Assessment This is the technical core of the audit.

- Perform Structure Discovery: Analyze data formats to ensure consistency (e.g., dates are all in YYYY-MM-DD, units are standardized to SI units) [30].

- Perform Content Discovery: Examine individual data rows for errors, outliers, or systemic issues in measurements [30].

- Calculate Quality Metrics: For key datasets, calculate the metrics listed in the table above (e.g., null counts, duplication rate) to establish a quantitative baseline [28].

4. Evaluate Data Quality and Governance Analyze the profiled data to uncover underlying quality issues. Assess if the data is timely, accurate, relevant, and complete. Simultaneously, review data security measures and access controls, especially for sensitive research data [26].

5. Check for Compliance and FAIRness Verify that data management practices align with relevant regulatory requirements (e.g., GDPR for personal data) and industry standards. Crucially for research, assess adherence to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles [26] [34].

6. Present Findings and Implement Changes Compile findings into a report that outlines the state of data sources, data quality, and compliance. Include clear recommendations for improvement. Use this report to drive data cleanup and process refinement [26].

Experimental Workflow: From Data Profiling to Auditing

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between data profiling and the broader data audit process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key software tools and their primary function in the data profiling and auditing process. Selecting the right tool is critical for an efficient and effective assessment [25] [29].

| Tool / Solution | Primary Function in Profiling/Auditing | Key Feature for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Alation [29] | Automated data catalog that embeds profiling into discovery workflows. | Provides data trust scores and integrates profiling results directly with business glossary definitions. |

| YData Profiling [25] | Open-source Python library for advanced profiling. | Generates detailed HTML reports with one line of code; ideal for data scientists familiar with Python. |

| IBM InfoSphereInformation Analyzer [30] | Enterprise-grade data discovery and analysis. | Strong relationship discovery (foreign key analysis) for complex, interconnected datasets. |

| Ataccama ONE [29] | AI-powered data quality management platform. | Features "pushdown profiling" for efficient execution directly within cloud data warehouses. |

| Great Expectations (GX) [25] | Python-based framework for data testing and quality. | Allows defining "Expectations" (unit tests for data), making data validation repeatable. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Visualization & Color Standardization

FAQ 1: My visualization fails automated accessibility checks. What are the minimum color contrast requirements?

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) define specific contrast ratios for text and visual elements [35] [36]. The requirements vary between Level AA (minimum) and Level AAA (enhanced).

Table: WCAG Color Contrast Requirements

Conformance Level Text Type Minimum Contrast Ratio Notes Level AA Small Text (below 18pt) 4.5:1 Standard for most body text [36]. Level AA Large Text (18pt+ or 14pt+bold) 3:1 Applies to large-scale text like headings [36]. Level AAA Small Text (below 18pt) 7:1 Enhanced requirement for higher accessibility [35] [37]. Level AAA Large Text (18pt+ or 14pt+bold) 4.5:1 Enhanced requirement for large text [35] [37]. Experimental Protocol: Validating Color Contrast

- Identify Test Elements: Compile all text elements and non-text graphical objects (e.g., data point markers, key lines) in your visualization.

- Measure Contrast: Use a color contrast analyzer (e.g., WebAIM Contrast Checker, axe DevTools) to determine the contrast ratio between the foreground (text/object) and background colors [36].

- Compare and Classify: For each element, compare the measured ratio against the required thresholds in the table above. Flag any element that does not meet the target conformance level.

- Iterate and Adjust: For failed elements, adjust the foreground or background color by modifying luminance, saturation, or hue until the contrast ratio is sufficient. Re-test until all elements pass.

FAQ 2: How do I select the correct type of color palette for my scientific data?

Using an inappropriate color palette can misrepresent the underlying data structure. The choice of palette should be dictated by the nature of your variable [38] [39].

Table: Guide to Data-Driven Color Palettes

Data Type Recommended Palette Scientific Application Implementation Notes Categorical (Qualitative) Distinct, unrelated hues. Differentiating between distinct sample groups, experimental conditions, or material classes [38] [40]. Limit palette to 5-7 colors for optimal human differentiation. Use tools like ColorBrewer or Adobe Color [38] [41] [42]. Sequential Shades of a single hue, from light to dark. Representing continuous values that progress from low to high, such as concentration, temperature, or pressure [38] [39]. Avoid using red-green gradients. Ensure each shade has a perceptible and uniform change in contrast [40]. Diverging Two contrasting hues that meet at a neutral central color. Highlighting data that deviates from a critical midpoint, such as profit/loss, gene expression up/down-regulation, or comparing results to a control value [38] [39]. The central color (e.g., white or light gray) should represent the neutral or baseline value. Experimental Protocol: Selecting and Applying a Color Palette

- Classify Your Variable: Determine if your data is categorical (distinct groups), sequential (ordered low-to-high), or diverging (values on both sides of a central point).

- Select a Base Palette: Based on the classification, choose an appropriate base palette from a trusted source like ColorBrewer, which offers accessible, pre-defined palettes.

- Test for Accessibility: Use simulation tools to check the palette for various forms of color vision deficiency (CVD). Ensure data is distinguishable without reliance on color alone (e.g., by adding patterns or direct labels) [40] [42].

- Apply and Document: Apply the palette consistently across all related visualizations. Document the color-to-value mapping in your methodology or figure legend.

FAQ 3: My chart becomes confusing when I have too many data categories. What is the optimal number of colors to use?

Cognitive science research indicates that the human brain can comfortably distinguish and recall a limited number of colors simultaneously. Exceeding this number increases cognitive load and reduces accuracy [41].

Table: Guidelines for Number of Colors in a Palette

Palette Context Recommended Maximum Rationale Categorical Data 5 to 7 distinct hues [41]. Aligns with the approximate number of objects held in short-term memory. Ensures colors are distinct and memorable [41]. For "Pop-Out" Effects Up to 9 colors [41]. Based on pre-attentive processing research; useful for highlighting specific data series among many. Inclusive Design 3 to 4 primary colors [41]. Prioritizes accessibility, ensuring the most frequently used colors are distinguishable by all users, including those with color vision deficiencies. Experimental Protocol: Managing Multi-Category Visualizations

- Prioritize and Group: If your data has more than 7 categories, assess if some can be logically grouped into a higher-level category.

- Use Interactive Highlighting: For static images, use a neutral gray for most data series and a single, highlight color to draw attention to one or two key series at a time [40] [42].

- Supplement with Other Encodings: Use other visual channels like shape (e.g., circles, squares) or texture (e.g., dashed, dotted lines) in conjunction with color to encode information [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Data Visualization Standardization

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| ColorBrewer 2.0 | Online tool for selecting safe, accessible, and colorblind-friendly color schemes for sequential, diverging, and qualitative data [40] [42]. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker | A tool to analyze the contrast ratio between two hex color values, ensuring they meet WCAG guidelines for text and background combinations [36]. |

| axe DevTools | An automated accessibility testing engine that can be integrated into development environments to identify contrast violations and other accessibility issues [36]. |

| Material Design Color Palette | A standardized, harmonious color system from Google that provides a full spectrum of colors with light and dark variants, useful for building a consistent UI/UX [43] [44]. |

| Viz Palette | A tool that helps preview and test color palettes in the context of actual charts and maps, allowing for refinement before final implementation [41]. |

Workflow Visualization: Data Standardization Process

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for applying standardization rules to materials data, from raw data to a validated, standardized dataset.

Color Palette Selection Logic