From Bacterial Defense to Genetic Scalpel: The Complete History and Clinical Transformation of CRISPR

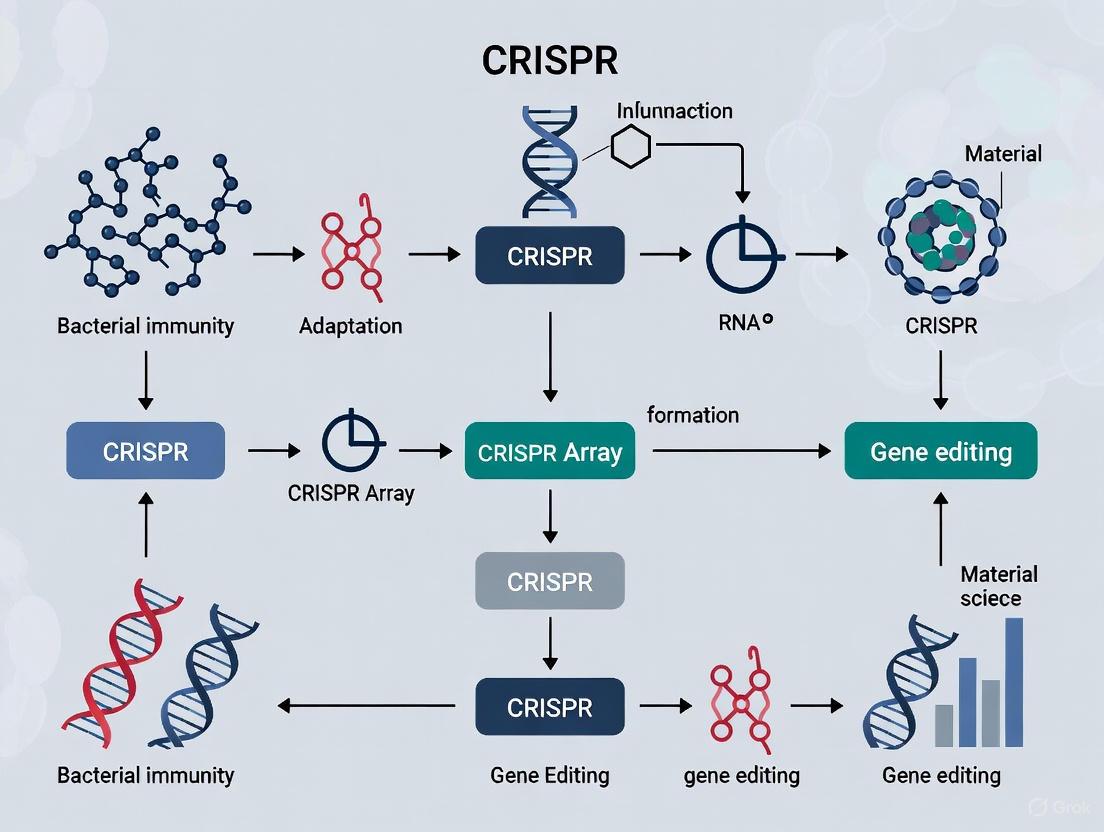

This article traces the remarkable journey of CRISPR-Cas systems from their initial discovery as a bacterial immune mechanism to their current status as a transformative technology in biomedicine.

From Bacterial Defense to Genetic Scalpel: The Complete History and Clinical Transformation of CRISPR

Abstract

This article traces the remarkable journey of CRISPR-Cas systems from their initial discovery as a bacterial immune mechanism to their current status as a transformative technology in biomedicine. We explore the foundational biology of CRISPR, detailing key discoveries from 1987 to the 2012 demonstration of programmable DNA cleavage. The review then examines the methodological leap to therapeutic applications, including the first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy and over 150 active clinical trials as of 2025. Critical analysis addresses persistent challenges like off-target effects and structural variations, while comparing CRISPR to alternative editing platforms. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides a comprehensive resource on the evolution, current landscape, and future trajectory of genome editing.

The Natural Blueprint: Decoding CRISPR as a Prokaryotic Immune System

In the mid-1980s, a fundamental research project on bacterial metabolism unexpectedly led to the first documented encounter with what would later be recognized as the CRISPR-Cas system. This discovery occurred not through targeted investigation of immune mechanisms, but rather during routine analysis of the iap gene (involved in isozyme conversion of alkaline phosphatase) in Escherichia coli [1] [2]. Yoshizumi Ishino and his team at Osaka University, while sequencing a 1.7-kbp DNA fragment spanning the iap gene region, stumbled upon an unusual set of repeated sequences in the 3' flanking region of the gene [1] [3] [2]. At the time, the scientific significance of these repeats was not understood, and their function remained enigmatic for nearly two decades. This initial finding marked the beginning of a long scientific journey that would ultimately revolutionize the field of genetics and genome engineering. The mysterious repeated sequence represented the first glimpse of a sophisticated adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, though its full implications would not be realized until the genomics era provided the necessary context and tools for functional analysis.

The 1987 Discovery: Technical Breakdown

Experimental Methodology and Technical Challenges

The discovery was made using the dideoxy sequencing method (Sanger sequencing), which was state-of-the-art in the mid-1980s [1]. The technical process involved several complex steps that presented significant challenges:

- Template Preparation: The target DNA fragment had to be cloned into M13 vectors to produce single-stranded template DNA for sequencing reactions [1].

- Sequencing Reaction: The chain termination reaction was performed using the Klenow fragment of E. coli polymerase I at 37°C, with reaction products labeled by incorporation of [α32P]dATP [1].

- Sequence Analysis: Sequence ladder images were obtained through autoradiography, requiring manual reading and interpretation [1].

The palindromic nature of the repeated sequences caused particular difficulties. The secondary structure formation led to nonspecific termination of the dideoxynucleotide incorporation reactions, making precise sequence reading exceptionally challenging [1]. This technical hurdle required months of painstaking work to precisely determine the sequence of what we now recognize as the CRISPR region—a task that contemporary technology can accomplish in a single day [1].

Structural Characteristics of the Discovered Repeats

Ishino and colleagues documented a unique arrangement of five highly homologous sequences of 29 nucleotides, arranged as direct repeats and separated by non-repetitive spacer sequences of 32 nucleotides [1] [2]. The key structural features included:

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of the Discovered Repeats in E. coli

| Feature | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat Length | 29 nucleotides | Unusual length for repetitive sequences |

| Spacer Length | 32 nucleotides | Variable sequences between repeats |

| Arrangement | 5 direct repeats with regular spacing | Distinct from typical tandem repeats |

| Palindromic Nature | Dyad symmetry within repeats | Potential for secondary structure formation |

| Genomic Location | 3' flanking region of iap gene | Located in intergenic space |

The researchers noted that these sequences showed no similarity to previously identified Repetitive Extragenic Palindromic (REP) sequences, indicating they had encountered a fundamentally new type of genetic element [1]. The repeats contained a dyad symmetry of 14 bp, suggesting potential to form stable secondary structures that might have functional significance [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods in the 1987 Discovery

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Context in 1987 Study |

|---|---|---|

| M13 Vectors (mp18/mp19) | Production of single-stranded DNA templates | Essential for dideoxy sequencing methodology |

| Klenow Fragment | DNA polymerase for dideoxy sequencing | Catalyzed chain termination reactions |

| [α32P]dATP | Radioactive labeling of DNA | Enabled visualization of sequence ladders |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (iap) Gene | Target gene for initial study | Served as reference point for unexpected discovery |

| Subcloning Techniques | Isolation of short DNA fragments | Required for sequencing manageable segments |

The Broader Historical Context and Significance

Connection to Subsequent CRISPR Research

The 1987 discovery remained an isolated curiosity for several years until similar sequences were identified in other organisms. In 1993, researchers observed comparable clustered repeats in the archaeon Haloferax mediterranei, which were initially termed Short Regularly Spaced Repeats (SRSRs) [1] [4]. Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante played a pivotal role in recognizing that these disparate findings in bacteria and archaea represented the same phenomenon [5] [3]. By 2000, Mojica had identified similar repeat clusters in 20 microbial species, confirming they belonged to a common family [3]. The term CRISPR was formally proposed in 2002 by Ruud Jansen et al. to standardize the nomenclature [1] [3].

The functional understanding of CRISPR began to emerge in 2005 when three independent research groups recognized that the spacer sequences between repeats matched fragments of bacteriophage DNA and plasmids [1] [5] [3]. This critical insight led to the hypothesis that CRISPR constitutes an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [5]. Experimental validation followed in 2007 when Barrangou et al. demonstrated that Streptococcus thermophilus could acquire new spacers from infecting bacteriophages and thereby develop resistance to subsequent infections [5] [3].

Methodological Evolution in CRISPR Research

The transition from initial discovery to functional characterization required significant advances in research methods:

CRISPR Research Methodology Evolution

The flow of methodological advances shows how the field progressed from basic observation to sophisticated manipulation of the CRISPR system. The automation of sequencing and development of bioinformatics tools were particularly crucial for recognizing the widespread distribution and common features of CRISPR loci across diverse microorganisms [1].

Timeline of Key Discoveries

Table 3: Major Milestones from Initial Discovery to Genome Editing Application

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Unusual repeats in E. coli | Ishino et al. | First documentation of CRISPR sequences |

| 1993-2000 | SRSRs in archaea and other bacteria | Mojica et al. | Recognition of common family of repeats |

| 2002 | cas genes identified | Jansen et al. | Discovery of genes associated with CRISPR |

| 2005 | Spacers match foreign DNA | Three independent groups | Hypothesis of adaptive immune function |

| 2007 | Experimental proof of adaptive immunity | Barrangou et al. | Demonstration of phage resistance mechanism |

| 2012 | CRISPR-Cas9 as programmable tool | Doudna, Charpentier, Siksnys | Development into genome editing technology |

The accidental discovery of unusual DNA repeats in E. coli in 1987 exemplifies how fundamental, curiosity-driven research can ultimately lead to transformative scientific breakthroughs. While the initial publication could only describe the unusual structure without understanding its function, it provided the essential foundation for deciphering the CRISPR-Cas system [1]. This discovery trajectory—from mysterious sequences to comprehensive understanding of an adaptive immune system and finally to revolutionary genome-editing technology—spanned nearly three decades and involved contributions from researchers worldwide [5].

The technological limitations of 1987, which made sequencing these repetitive regions so challenging, highlight how methodological advances can unlock the potential of earlier observations. Modern CRISPR-based technologies, including CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, base editing, and gene regulation tools, all trace their origins to this initial characterization of unusual repeats in E. coli [6] [7]. The journey from the first observation to the Nobel Prize-winning application of CRISPR-Cas9 in 2020 demonstrates the unpredictable but profound impact of basic scientific research on biological understanding and technological capability [8].

{Abstract} The transformative journey of CRISPR from a curious genetic sequence in prokaryotes to a revolutionary genome-editing technology is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology. This whitepaper examines the pivotal role of Francisco Mojica, who first identified CRISPR as a prokaryotic adaptive immune system. His crucial insight provided the foundational hypothesis that redirected CRISPR research from a biological curiosity to a focused investigation of a microbial defense mechanism, ultimately enabling the development of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. This document details the experimental evidence that validated Mojica's hypothesis, the molecular mechanisms of CRISPR adaptive immunity, and the key reagents that facilitated these discoveries, providing a comprehensive technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) locus was first observed in 1987 in Escherichia coli but its function remained enigmatic for years [9] [3]. These peculiar genetic elements, characterized by direct repeats interspaced with variable sequences, were noted in various bacterial and archaeal genomes without a clear understanding of their biological significance [8]. The pivotal turning point came through the persistent work of Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante, who throughout the 1990s studied these repetitive sequences in archaeal organisms such as Haloferax mediterranei [5].

By 2000, Mojica had recognized that these disparate repeat sequences shared common features across species and coined the term CRISPR through correspondence with Ruud Jansen, who first used the term in print in 2002 [5] [3]. The critical breakthrough occurred in 2005 when Mojica and colleagues performed a comprehensive bioinformatic analysis demonstrating that the variable spacer sequences between CRISPR repeats were derived from viral and plasmid DNA [5] [3]. This led Mojica to hypothesize, correctly, that CRISPR constitutes an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [5]. Concurrently, similar findings were reported by two other groups, but it was Mojica who first recognized the widespread nature and potential immunological function of these sequences [5] [3]. This hypothesis represented a paradigm shift in understanding prokaryotic defense mechanisms and set the stage for all subsequent CRISPR-based technologies.

Molecular Architecture of the CRISPR-Cas System

The CRISPR-Cas system consists of two fundamental genetic components: the CRISPR array and the cas (CRISPR-associated) genes [9] [10]. The CRISPR array is composed of an AT-rich leader sequence followed by short, partially palindromic repeats (typically 28-37 base pairs) separated by variable spacers of similar length (typically 32-38 bp) [9] [3]. These spacers originate from previously encountered foreign genetic elements and serve as a genetic memory of past infections [9] [10].

Flanking the CRISPR array are the cas genes, which encode the protein machinery responsible for the three stages of CRISPR-mediated immunity: adaptation, expression and biogenesis, and interference [9] [10]. While there is considerable diversity in CRISPR-Cas systems, classified into 2 classes, 6 types, and numerous subtypes, the universal presence of cas1 and cas2 across all types highlights their fundamental role in the adaptive immune function [9] [8]. The protein Cas1, in particular, is hypothesized to play a central role in the acquisition of new spacers, working in conjunction with other Cas proteins and potentially non-Cas cellular factors [10].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas System

| Component | Structure/Composition | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Array | Leader sequence + repeats (28-37 bp) + spacers (32-38 bp) [9] [3] | Genomic record of past infections; template for crRNA production |

| Spacers | Variable sequences derived from viruses/plasmids [9] [10] | Immunological memory; guides Cas proteins to complementary invader sequences |

| Repeats | Short, partially palindromic DNA sequences [9] | Form hairpin structures in RNA; processing signals during crRNA biogenesis |

| cas Genes | cas1, cas2 (universal); signature genes (cas3, cas9, cas10 for Types I, II, III) [9] [8] | Encode protein machinery for adaptation, crRNA processing, and target interference |

| Leader Sequence | AT-rich region upstream of CRISPR array [10] | Promoter for transcription; site for integration of new spacers |

Experimental Validation of Mojica's Adaptive Immunity Hypothesis

Key Evidence fromStreptococcus thermophilusResearch

The first experimental validation of Mojica's hypothesis came in 2007 from researchers at Danisco France SAS, who demonstrated that the CRISPR-Cas system in S. thermophilus provides acquired resistance against bacteriophages [9] [5]. This seminal study, led by Rodolphe Barrangou and Philippe Horvath, provided direct evidence that CRISPR is an adaptive immune system by showing that:

- Exposure to bacteriophages led to the acquisition of new spacers derived from the infecting phage genome into the CRISPR locus [9] [5].

- These newly acquired spacers were integrated at the leader end of the CRISPR array, creating a chronological record of infections [9].

- The presence of these spacers conferred specific, heritable immunity against subsequent infections by phages containing matching sequences [9] [10].

- The removal of these spacers eliminated the immunity, confirming their essential role in the defensive mechanism [3].

This research also highlighted that only a subpopulation of bacteria successfully acquired new spacers and became immunized, but this subpopulation gained a high level of specific resistance [9]. The study further established that the system could target various regions of the viral genome, including both DNA strands and both coding and non-coding sequences [9].

Elucidating the Mechanism: From DNA Targeting to RNA-Guided Cleavage

Following the validation of adaptive immunity, subsequent research focused on unraveling the molecular mechanism. Key experiments included:

- 2008 - CRISPR arrays are transcribed and processed into guide RNAs: John van der Oost's group demonstrated that the CRISPR locus is transcribed into a long precursor RNA, which is then processed into small CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that guide Cas proteins to the target DNA [5] [3].

- 2008 - DNA is the molecular target: Luciano Marraffini and Erik Sontheimer confirmed that the CRISPR system targets and cleaves DNA, not RNA, establishing its potential as a DNA-editing tool [5] [3].

- 2010 - Cas9 is the sole nuclease required for cleavage: Sylvain Moineau's team provided biochemical evidence that the Cas9 protein creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA at precise positions, a defining feature of Type II CRISPR systems [5].

- 2011 - Discovery of tracrRNA: Emmanuelle Charpentier's group identified a second, essential RNA molecule, trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which forms a duplex with crRNA to guide Cas9 [5].

Table 2: Key Experiments Validating CRISPR as an Adaptive Immune System

| Year | Lead Researcher(s) | Experimental System | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Francisco Mojica [5] | Computational analysis of multiple genomes | Spacers derive from viral/plasmid DNA | Formulated adaptive immunity hypothesis |

| 2007 | Rodolphe Barrangou, Philippe Horvath [9] [5] | Streptococcus thermophilus & phage challenge | Acquisition of phage-derived spacers confers specific immunity | First experimental proof of adaptive immunity |

| 2008 | John van der Oost [5] [3] | E. coli | CRISPR transcripts processed into small guide crRNAs | Elucidated the RNA-guided nature of the system |

| 2008 | Luciano Marraffini, Erik Sontheimer [5] [3] | Staphylococcus epidermidis | CRISPR system prevents plasmid conjugation by targeting DNA | Established DNA as the target molecule |

| 2010 | Sylvain Moineau [5] | S. thermophilus | Cas9 creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA | Identified the specific nuclease and its mechanism |

| 2011 | Emmanuelle Charpentier [5] | Streptococcus pyogenes | tracrRNA essential for crRNA maturation and Cas9 function | Completed the picture of the Cas9 guidance complex |

Diagram 1: CRISPR Adaptive Immunity Pathway and Key Discoveries

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The experimental breakthroughs in characterizing CRISPR relied on specific biological tools and reagents. The following table details key resources that were instrumental in these foundational studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Foundational CRISPR Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in CRISPR Research | Application in Key Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains\newline(S. thermophilus, E. coli) | Model organisms for studying CRISPR function [9] [5] | Phage challenge experiments (Barrangou 2007); Heterologous system validation (Siksnys 2011) [5] |

| Bacteriophages & Plasmids | Sources of exogenous DNA (protospacers) to challenge the CRISPR system [9] [10] | Trigger spacer acquisition; test immunization specificity and efficiency [9] |

| CRISPR Locus Clones | Defined genetic constructs for functional studies in heterologous hosts [5] | Demonstrated CRISPR systems are self-contained units (Sapranauskas et al., 2011) [5] |

| Cas Protein Purification Kits | Isolation of active Cas enzymes for biochemical characterization [5] | In vitro cleavage assays to define Cas9 mechanism (Gasiunas et al., 2012; Jinek et al., 2012) [5] |

| RNA Sequencing Reagents | Identification and characterization of small CRISPR-derived RNAs (crRNA, tracrRNA) [5] | Discovery of crRNA (van der Oost 2008) and tracrRNA (Charpentier 2011) [5] |

The Bridge to Genome Editing: How an Immunity Mechanism Became a Tool

The characterization of CRISPR as an adaptive immune system directly enabled its repurposing into a programmable genome-editing tool. Understanding that crRNAs guide Cas proteins to specific DNA sequences for cleavage provided the conceptual framework for engineering this system [9] [5]. The critical technical leap was the simplification of the dual-RNA (crRNA and tracrRNA) structure into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), creating a two-component system where a customizable sgRNA directs Cas9 to any DNA sequence adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [5] [11].

This reprogrammability was demonstrated in 2012-2013, when multiple groups showed that engineered CRISPR-Cas9 systems could edit genomes in human cells [5] [11]. The technology has since evolved beyond the original Cas9, with the discovery of other effectors like Cas12a (which targets DNA and has a different PAM requirement) and Cas13a (which targets RNA), further expanding the toolbox for basic research and therapeutic development [3]. The first FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapy, Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, marks the clinical realization of a technology that began with Mojica's crucial insight into a bacterial immune system [12] [11].

Francisco Mojica's recognition of CRISPR as a prokaryotic adaptive immune system represents one of the most consequential biological insights of the early 21st century. His hypothesis, built on astute bioinformatic analysis, provided the necessary framework that guided subsequent experimental research to validate and characterize the system's mechanisms. The collaborative work of scientists worldwide transformed this fundamental biological discovery into the precise and programmable CRISPR-Cas9 technology, ushering in a new era of genome engineering. Today, this technology is driving advances across biomedical research, with applications ranging from functional genomics and disease modeling to groundbreaking gene therapies, all stemming from the initial effort to understand an ancient form of microbial immunity.

The 2007 study by Barrangou, Horvath, and colleagues at Danisco marked a paradigm shift in molecular biology by providing the first experimental validation that the CRISPR-Cas system serves as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes. Working with Streptococcus thermophilus, a bacterium crucial for yogurt and cheese production, the team demonstrated that bacteria acquire new spacers from invading bacteriophages and integrate these sequences into their CRISPR loci, conferring specific resistance against subsequent viral attacks. This foundational research not only elucidated a fundamental microbial defense mechanism but also paved the way for the development of CRISPR-Cas9 into a revolutionary genome-editing tool. This whitepaper details the experimental methodologies, quantitative findings, and conceptual breakthroughs of the 2007 study, framing it within the broader history of CRISPR research from bacterial immunity to gene editing applications.

Prior to 2007, the function of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) remained largely enigmatic despite several key discoveries.

- Initial Discoveries: Unusual repetitive sequences were first reported in E. coli in 1987 [3], and were later characterized in archaea and numerous bacteria by Francisco Mojica, who also coined the CRISPR acronym [8] [5].

- Emerging Hypothesis: By 2005, bioinformatic analyses by Mojica and others revealed that the "spacer" sequences between CRISPR repeats often matched sequences from bacteriophages and plasmids [13] [8]. This led to the hypothesis that CRISPR, along with its associated cas genes, might function as a prokaryotic immune system [7] [3].

- The Critical Unresolved Question: While the hypothesis was compelling, direct experimental evidence was lacking. The scientific community required definitive proof that bacteria could acquire new immunity by incorporating viral DNA into their genomes and that this process was specific and heritable. The 2007 study was designed to fill this critical knowledge gap, driven by a practical need in the dairy industry to protect bacterial cultures from viral contamination [13].

Experimental System and Methodology

The research team employed a straightforward yet powerful model system to test the adaptive immunity hypothesis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key research materials and their functions in the 2007 study.

| Research Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Streptococcus thermophilus | Model bacterium; primary subject for studying CRISPR-mediated immunity. |

| Bacteriophages | Viral pathogens used to challenge bacteria and trigger immune response. |

| CRISPR-Spacer Specific Primers | Oligonucleotides for PCR amplification and sequencing of CRISPR loci to monitor spacer acquisition. |

| Cas Gene Inactivation Constructs | Genetic tools to disrupt specific cas genes (e.g., cas5, cas7) to determine their functional roles. |

Core Experimental Workflow

The experimental design followed a logical progression from observation to manipulation, as outlined below.

Diagram 1: Core experimental workflow for validating adaptive immunity.

Key Experiments and Quantitative Results

The study provided conclusive evidence through a series of interlinked experiments.

Spacer Acquisition and Phage Resistance

The team first infected a phage-sensitive strain of S. thermophilus with two different bacteriophages and analyzed the CRISPR loci in surviving daughter strains [13].

Table 2: Observed spacer acquisition and resulting phage resistance.

| Experimental Condition | Change in CRISPR Array | Resistance Phenotype After Re-challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Infection with Phage 1 | Gain of 1-4 new spacers | Resistant to Phage 1 |

| Infection with Phage 2 | Gain of 1-4 new spacers | Resistant to Phage 2 |

| Co-infection with Phage 1 & 2 | Gain of up to 4 spacers (mix from both phages) | Resistant to both Phage 1 and Phage 2 |

| No Phage Challenge (Control) | No change in CRISPR array | Remained phage-sensitive |

The DNA sequences of the newly acquired spacers were a perfect match to the genomes of the infecting phages, providing a molecular record of the infection history [13] [5]. Furthermore, the resistance was highly specific; bacteria were only immune to phages whose DNA matched the spacers they had acquired [13].

Direct Causation via Spacer Manipulation

To move beyond correlation, the researchers directly manipulated spacer content.

- Spacer Deletion: They removed a specific spacer from a virus-resistant bacterial strain. This modification rendered the bacteria susceptible to the virus again, demonstrating that the spacer was necessary for immunity [13].

- Spacer Addition: They introduced a spacer specific to a particular virus into a previously susceptible bacterial strain. This engineered strain gained resistance to that virus, proving that the spacer was sufficient to confer immunity [13] [7].

Functional Analysis of Cas Proteins

The role of Cas proteins was investigated by inactivating specific cas genes in virus-resistant bacteria [13].

Table 3: Impact of Cas gene inactivation on bacterial immunity.

| Inactivated Gene | Known/Predicted Function | Effect on Phage Resistance | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| cas5 | DNA-cutting enzyme (nuclease) | Loss of resistance | Essential for interfering with and inactivating viral DNA. |

| cas7 | Unknown at the time | Resistance maintained | Likely involved in the acquisition of new spacers, not interference. |

Discussion: Mechanistic Insight and Historical Impact

The Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas Adaptive Immunity

The 2007 study allowed Horvath and colleagues to propose a coherent model for CRISPR-Cas function, which subsequent research would elaborate on.

Diagram 2: Model of the adaptive immune process in bacteria.

Bridging Bacterial Immunity to Gene Editing Technology

The 2007 discovery was the crucial link that transformed CRISPR from a biological curiosity into a technological platform.

- Foundation for Gene Editing Tools: The demonstration that Cas9 was the sole nuclease required for interference [5] focused research efforts on this particular protein. The understanding that the system could be re-targeted simply by changing the spacer sequence was the fundamental insight that enabled its engineering for gene editing [13] [7].

- Direct Line to Nobel Prize: The work by Horvath and Barrangou established the functional principle. Subsequent research, including the characterization of the dual-RNA structure (crRNA and tracrRNA) by Charpentier, its simplification into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) by Doudna and Charpentier, and its adaptation for use in eukaryotic cells by Zhang and Church, built directly upon this foundation [8] [5] [14]. This collective effort culminated in the award of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Charpentier and Doudna.

The 2007 yogurt bacterium study served as the critical experimental validation that propelled the CRISPR field forward. By rigorously demonstrating that the CRISPR-Cas system provides heritable, sequence-specific adaptive immunity in bacteria, Barrangou, Horvath, and their team unlocked a new era in molecular biology. Their work, rooted in solving an industrial problem, provided the mechanistic blueprint that allowed other scientists to repurpose bacterial defense machinery into the versatile, precise, and powerful CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool. This tool is now revolutionizing basic research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology, illustrating how fundamental discovery research can have transformative and unforeseen impacts.

The transformation of the CRISPR-Cas system from a fundamental prokaryotic immune mechanism to a revolutionary genome-editing technology hinges on the discovery and understanding of its core molecular components: the Cas proteins, CRISPR RNA (crRNA), and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). These elements constitute the central machinery that allows bacteria and archaea to adaptively defend against invading genetic elements and provide researchers with a programmable platform for precise DNA manipulation. Within the broader history of CRISPR, the elucidation of these components represents the critical bridge between the observation of a natural bacterial immunity and the engineering of a versatile technological tool. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the discovery, function, and interplay of these core components, framing them within the scientific journey that has reshaped modern biological research and therapeutic development.

Historical Context: From Bacterial Repeats to an Adaptive Immune System

The understanding of CRISPR evolved from the observation of curious genetic repeats to the realization of a sophisticated, adaptive immune system. Table 1 summarizes the key historical milestones that led to the identification of the central machinery.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Discoveries of Core CRISPR Components

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers/Team | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Identification of unusual repetitive sequences in E. coli | Ishino et al. [8] | Initial discovery of what would later be known as CRISPR. |

| 2000 | Recognition of common features in disparate repeat sequences; coinage of "CRISPR" | Francisco Mojica [5] | Unified disparate observations and provided a defining name for the phenomenon. |

| 2002 | Identification of Cas (CRISPR-associated) genes | Ruud Jansen et al. [8] | Found genes consistently located near CRISPR loci, suggesting a functional relationship. |

| 2005 | Hypothesis of CRISPR as an adaptive immune system; spacer origins in phage genes | Mojica et al.; Pourcel et al. [5] | Proposed the biological function and noted spacer sequences matched viral or plasmid DNA. |

| 2005 | Discovery of Cas9 and the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | Alexander Bolotin et al. [8] [5] | Identified the key effector nuclease and the essential targeting motif. |

| 2007 | Experimental demonstration of adaptive immunity | Rodolphe Barrangou, Philippe Horvath et al. [8] [5] | Showed bacteria integrate new spacers upon phage exposure, conferring resistance. |

| 2008 | Identification of crRNAs as guides for interference | John van der Oost et al. [5] | Revealed that spacers are processed into small RNAs that guide targeting. |

| 2011 | Discovery of the essential tracrRNA | Emmanuelle Charpentier et al. [8] [15] [5] | Identified the second RNA component required for Cas9-mediated crRNA processing and DNA cleavage. |

The journey began in 1987 with the identification of unusual repetitive sequences in the E. coli genome, though their function remained unknown [8]. For years, Francisco Mojica was a central figure, recognizing these sequences as a distinct class and, in 2000, naming them CRISPR [5]. His critical insight in 2005, concurrently with another group, that the "spacer" sequences between repeats matched viral DNA, led to the correct hypothesis that CRISPR functions as an adaptive immune system [5]. That same year, Alexander Bolotin's discovery of the Cas9 gene and the PAM sequence provided essential clues about the specific machinery of the Type II CRISPR system [8] [5]. The system's adaptive nature was proven experimentally in 2007, and the mechanism was further clarified with the discovery that spacer sequences are transcribed into guide RNAs (crRNAs) [5]. The final, pivotal piece was the 2011 discovery of tracrRNA by Emmanuelle Charpentier, which completed the picture of the core machinery [8] [15] [5].

The Core Molecular Components

The functional unit of the Type II CRISPR-Cas system is composed of three core elements: the Cas protein effector, the crRNA, and the tracrRNA.

Cas Proteins: The Effector Enzymes

Cas proteins are the enzymes that execute the functions of the CRISPR system. The Cas9 nuclease is the hallmark effector of the Type II system.

- Function: Cas9 is a dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease that introduces double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in target DNA [7]. It contains two nuclease domains: an HNH domain that cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the crRNA guide, and a RuvC-like domain that cleaves the non-complementary strand [5].

- Discovery: Cas9 was first described in connection with CRISPR repeats in 2005 by Bolotin et al., who noted its novel nuclease motifs and its association with a specific sequence pattern adjacent to spacer targets (the PAM) [8].

- PAM Requirement: Cas9 requires a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence immediately following the target DNA region complementary to the crRNA. This requirement is critical for self versus non-self discrimination, preventing the Cas9 complex from attacking the bacterial genome's own CRISPR array [8] [5].

crRNA and tracrRNA: The Guidance System

The RNA components work in concert to direct Cas9 to its specific DNA target.

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): The crRNA is processed from a long precursor transcript (pre-crRNA) of the entire CRISPR array. Each mature crRNA contains a spacer sequence (typically 20 nucleotides in engineered systems) that is complementary to the target DNA, serving as the guide [8] [15].

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA): The tracrRNA is a small, non-coding RNA that is essential for crRNA maturation and Cas9 function. It is partially complementary to the repeat regions in the pre-crRNA.

- Discovery: Identified in 2011 by Charpentier et al. using high-throughput sequencing in Streptococcus pyogenes, it was one of the most abundant small RNAs in the cell [15] [5].

- Function: The tracrRNA base-pairs with the pre-crRNA repeats, forming a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structure. This duplex is a substrate for the host enzyme RNase III, which cleaves the pre-crRNA into individual, mature crRNAs [8] [15]. Furthermore, the mature tracrRNA remains associated with the crRNA and Cas9, forming the active ribonucleoprotein complex that surveils DNA [15].

Table 2: Core Molecular Components of the Type II CRISPR-Cas System

| Component | Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | Protein (Nuclease) | Effector enzyme; cleaves target DNA | Dual nuclease activity (HNH & RuvC domains); requires PAM for target recognition [8] [5]. |

| crRNA | RNA (Guide) | Specifies DNA target sequence | Contains the ~20 nt spacer sequence; processed from pre-crRNA; forms a duplex with tracrRNA [8] [15]. |

| tracrRNA | RNA (Trans-activating) | Facilitates crRNA maturation and Cas9 function | Base-pairs with crRNA repeat regions; essential for RNase III processing; part of the active complex [15] [5]. |

| PAM | DNA Motif | Self vs. non-self discrimination | Short (2-5 bp) DNA sequence adjacent to the target; required for Cas9 to initiate DNA unwinding and cleavage [8] [5]. |

The Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) Engineering Breakthrough

A pivotal moment in the transition from biological mechanism to biotechnological tool was the engineering of the single-guide RNA (sgRNA). In 2012, researchers led by Charpentier and Doudna demonstrated that the two essential RNA components, the crRNA and tracrRNA, could be fused into a single chimeric molecule via a synthetic loop [15] [5]. This sgRNA recapitulates the function of the natural dual-RNA complex but greatly simplifies the system for experimental and therapeutic use, as only one RNA molecule needs to be designed and delivered to program Cas9 [15].

Molecular Mechanism and Key Experimental Protocols

The functional interplay between the core components follows a precise sequence of events, from crRNA biogenesis to target cleavage.

The crRNA Biogenesis and DNA Interference Pathway

Diagram 1: crRNA biogenesis and DNA interference pathway. This workflow illustrates the natural process from RNA transcription to target DNA cleavage in the Type II CRISPR-Cas system.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

The elucidation of this pathway relied on several foundational experiments.

Experiment 1: Demonstrating the Role of tracrRNA in crRNA Processing (2011)

- Objective: To identify and characterize the function of tracrRNA in the Type II CRISPR system of Streptococcus pyogenes.

- Protocol:

- Identification: Perform dRNA-seq (differential RNA sequencing) on S. pyogenes to catalog all primary transcripts and processed small RNAs [15].

- Localization: Map abundant small RNAs to the genome, identifying tracrRNA adjacent to the cas9 gene and noting its complementarity to CRISPR repeats [15].

- Genetic Knockdown: Use a conditional knockout to deplete tracrRNA and analyze the CRISPR array transcript via Northern blot. Result: Accumulation of unprocessed pre-crRNA, demonstrating tracrRNA is essential for maturation [15].

- In Vitro Reconstitution: Purify Cas9, RNase III, pre-crRNA, and tracrRNA. Incubate components and analyze products by gel electrophoresis. Result: Cleavage of pre-crRNA into mature crRNAs only occurs when all components are present [15].

Experiment 2: In Vitro Reconstitution of DNA Cleavage (2012)

- Objective: To demonstrate that Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA are sufficient for programmable DNA cleavage.

- Protocol:

- Component Purification: Recombinantly express and purify Cas9 protein. Chemically synthesize or in vitro transcribe crRNA and tracrRNA (or a fused sgRNA) [5].

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Pre-incubate Cas9 with the guide RNAs to form the active complex.

- Cleavage Assay: Incubate the RNP complex with a target DNA plasmid containing a complementary target site and the correct PAM.

- Analysis: Analyze the reaction products by agarose gel electrophoresis. The successful introduction of a double-strand break will linearize a supercoiled plasmid, resulting in a distinct band shift [5].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR Core Machinery Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector | Provides the genetic template for expressing the Cas9 nuclease in heterologous systems (e.g., E. coli or human cells). | The initial work by Siksnys et al. (2011) cloned the entire S. thermophilus CRISPR-Cas locus into E. coli to demonstrate it was a self-contained unit [5]. |

| Guide RNA Cloning Backbone | Plasmid vector (often with a U6 promoter) for expressing sgRNA or the separate crRNA and tracrRNA components. | Vectors are designed for easy insertion of a 20-nt guide sequence to target any locus of interest [16]. |

| RNase III | Host endoribonuclease used in vitro to study the natural crRNA biogenesis pathway. | Used in Charpentier et al. (2011) to demonstrate its essential role in processing the pre-crRNA:tracrRNA duplex [15]. |

| Synthetic crRNA & tracrRNA | Chemically synthesized RNAs for in vitro biochemical assays and formation of RNP complexes for direct delivery. | Allows for precise control over RNA sequence and chemical modifications; essential for the foundational in vitro cleavage assays [5]. |

| Target DNA Plasmid (with PAM) | A substrate for in vitro cleavage assays to validate the activity and specificity of the assembled CRISPR complex. | Typically contains a supercoiled plasmid with a target sequence matching the guide spacer and the required PAM sequence [5]. |

From Natural Machinery to Programmable Tool

The complete understanding of the core machinery enabled its repurposing into a revolutionary technology. The key steps were:

- Heterologous Function: The demonstration that the CRISPR-Cas system from S. thermophilus could function in E. coli proved it was a portable, self-contained unit [5].

- Biochemical Characterization: Work from the Siksnys lab (2012) and the Charpentier/Doudna collaboration (2012) purified the Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex and definitively showed it could be reprogrammed to cut any DNA target of choice simply by changing the 20-nt guide sequence within the crRNA [5].

- sgRNA Engineering: The fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) dramatically simplified the system for widespread adoption [15] [5].

- Eukaryotic Genome Editing: The final leap was made in 2013 when multiple groups, including Feng Zhang and George Church, successfully adapted CRISPR-Cas9 for precise genome editing in human and mouse cells [5].

The Cleavage Mechanism of Cas9

Diagram 2: Cas9 DNA cleavage mechanism. The Cas9-sgRNA complex recognizes the target site via PAM binding and complementary base pairing. The HNH nuclease domain cleaves the target strand (complementary to the sgRNA), while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target strand, resulting in a blunt-ended double-strand break.

Frontiers and Future Directions

The exploration of the central CRISPR machinery continues to advance rapidly. Current research focuses on overcoming initial limitations and expanding functionality:

- Enhancing Specificity: Engineering high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF, eSpCas9) with reduced off-target effects through rational mutagenesis [7].

- Expanding the Toolbox: Discovery and characterization of novel Cas effectors beyond Cas9 (e.g., Cas12, Cas13) with different properties, PAM requirements, and the ability to target RNA [7] [17].

- Precision Editing: Development of "base editors" and "prime editors" that directly convert one base to another without causing a DSB, offering greater precision and safety for therapeutic applications [7] [18].

- AI-Driven Design: The use of large language models (LMs) to design novel, highly functional CRISPR-Cas proteins that do not exist in nature. A 2025 study demonstrated the AI-generated editor "OpenCRISPR-1," which is highly active and specific despite being 400 mutations away from any known natural Cas9 [19]. This represents a move from mining natural diversity to de novo computational creation of core machinery.

The discovery and functional characterization of the central machinery—Cas proteins, crRNA, and the essential tracrRNA—unlocked the true potential of the CRISPR system. What began as a fundamental inquiry into a bacterial immune mechanism has yielded a programmable platform that is simple, efficient, and versatile. The ongoing refinement and expansion of this core toolbox, from high-fidelity variants to AI-designed editors, continues to drive progress across basic research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology, solidifying its role as one of the most transformative technologies in modern science.

The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) represents a fundamental genetic signature that enables CRISPR-Cas systems to distinguish between self and non-self DNA, thereby driving the function of bacterial adaptive immunity. This technical guide examines Alexander Bolotin's seminal 2005 discovery of the PAM sequence and its pivotal role in CRISPR target recognition. We explore the mechanistic basis of PAM function, its necessity in CRISPR experiment design, and the evolving landscape of PAM utilization from natural systems to engineered variants with expanded targeting capabilities. Within the broader context of CRISPR history, Bolotin's identification of this essential motif provided the critical missing link that ultimately enabled the development of precise genome editing technologies now revolutionizing basic research and therapeutic development.

The CRISPR-Cas system represents a remarkable example of how fundamental bacterial microbiology can yield transformative technological applications. The journey from observing unusual genetic repeats in prokaryotes to programming precise genome editors hinges on understanding molecular recognition mechanisms. Central to this story is the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)—a short, specific DNA sequence that must flank CRISPR target sites for successful recognition and cleavage by Cas nucleases [20] [21].

The significance of the PAM extends far beyond its biochemical role; it represents the system's security mechanism for distinguishing invading viral DNA from the bacterium's own genetic material [20]. This self versus non-self discrimination capability proved to be the critical feature that allowed researchers to harness CRISPR as a programmable genome engineering tool rather than merely an interesting bacterial immunity phenomenon.

Alexander Bolotin's key finding emerged from his 2005 study of Streptococcus thermophilus at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) [22] [5]. While examining a newly sequenced CRISPR locus, Bolotin and colleagues noted not only novel Cas genes (including what would become known as Cas9) but also made a crucial observation: the spacers, which shared homology with viral genes, all contained a common sequence at one end [22] [5]. This conserved motif, later termed the protospacer adjacent motif, would prove essential for target recognition in CRISPR systems.

Historical Context: Bolotin's Key Discovery

The Research Landscape in 2005

By 2005, Francisco Mojica had already established that CRISPR sequences matched snippets from bacteriophage genomes, correctly hypothesizing that CRISPR functions as an adaptive immune system [22] [8] [5]. However, a fundamental question remained: how could bacterial cells maintain a library of viral DNA sequences without triggering self-destruction? The solution to this paradox emerged from Bolotin's analysis of Streptococcus thermophilus strain LMD-9.

Bolotin's key contribution was recognizing that while spacers in the bacterial CRISPR array lacked specific flanking sequences, the matching viral protospacers consistently contained a conserved nucleotide motif at one end [5]. This observation revealed the PAM's function as a "non-self" identifier—the bacterial genome lacked PAM sequences adjacent to stored spacers, thereby preventing autoimmune cleavage [20] [21].

Experimental Basis for PAM Identification

Bolotin's discovery emerged from computational analysis of spacer-protospacer alignments, a methodology that would become foundational for PAM characterization [23]. His team analyzed the S. thermophilus CRISPR locus and observed that:

- Spacer Origin: Spacers derived from extrachromosomal elements, primarily viruses

- Conserved Flanking Sequence: All protospacers shared a common adjacent motif

- Novel Cas Genes: The locus contained previously uncharacterized genes, including one encoding a large protein with predicted nuclease activity (later named Cas9)

This bioinformatic approach revealed that the PAM sequence was consistently present in viral DNA but absent from the bacterial CRISPR array, providing the first clue to its role in self/non-self discrimination [22] [5].

The Molecular Mechanism of PAM Function

Self Versus Non-Self Discrimination

The PAM sequence solves a critical security challenge for the CRISPR system: how to identify invading DNA while ignoring the bacterial genome's own CRISPR arrays. The mechanism is elegant in its simplicity:

- Invading DNA: Contains target sequence (protospacer) with adjacent PAM → cleavage occurs

- Bacterial CRISPR DNA: Contains spacer sequence without adjacent PAM → no cleavage [20] [21]

This discrimination occurs because Cas nucleases first search for PAM sequences before unwinding DNA to check for guide RNA complementarity [20] [23]. When Cas identifies the correct PAM, it undergoes conformational changes that enable DNA unwinding and subsequent guide RNA matching. Without PAM recognition, the interrogation process does not initiate, regardless of target sequence complementarity.

Structural Basis of PAM Recognition

Structural studies have revealed that Cas proteins contain specialized PAM-interacting domains that physically recognize specific DNA sequences [23]. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM interaction domain recognizes 5'-NGG-3' sequences through a combination of base-specific contacts and DNA distortion mechanisms. This specific protein-DNA interaction triggers conformational changes in Cas9 that facilitate:

- Local DNA melting to create a DNA "bubble"

- RNA-DNA hybridization between the guide RNA and target strand

- Nuclease activation and double-strand break formation 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM [20]

Table 1: PAM Sequences for Commonly Used CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| LbCas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

Figure 1: PAM-Mediated Target Recognition Cascade. The PAM sequence initiates a sequential process where (1) Cas9 recognizes the PAM, (2) unwinds adjacent DNA, (3) enables guide RNA complementarity checking, and (4) triggers DNA cleavage if matching occurs.

PAM Requirements in CRISPR Experiment Design

Target Site Selection Constraints

The PAM sequence imposes the primary constraint on CRISPR target site selection, as editing can only occur at genomic locations containing the appropriate nuclease-specific PAM [20]. For the most commonly used SpCas9, this means any target site must be followed by 5'-NGG-3' (where N is any nucleotide). This requirement fundamentally influences guide RNA design and experimental planning.

Several strategies have emerged to overcome PAM-imposed limitations:

- Nuclease Selection: Choosing alternative Cas proteins with different PAM requirements (see Table 1)

- PAM Engineering: Using engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities

- Target Locus Analysis: Identifying available PAM sequences near the desired edit site [20]

Experimental Determination of PAM Specificity

Several methodologies have been developed to characterize PAM requirements for novel or engineered Cas nucleases:

Plasmid Depletion Assay

This in vivo approach involves transforming a host expressing the CRISPR-Cas system with a plasmid library containing randomized DNA adjacent to a target sequence. Plasmids with functional PAM sequences are depleted, while those with non-functional PAMs are retained and quantified via next-generation sequencing [23].

Protocol:

- Clone a target sequence followed by a randomized NNNN region into a plasmid

- Transform the plasmid library into cells expressing the Cas nuclease and guide RNA

- Harvest plasmids after selection and sequence the randomized region

- Compare sequence abundance to the initial library to identify depleted PAMs

PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression)

This high-throughput method uses a catalytically dead Cas variant (dCas9) coupled to a transcriptional repressor. When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM, it represses GFP expression, enabling fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate and sequence functional PAM sequences [23].

Protocol:

- Create a target library with randomized PAM regions upstream of a GFP reporter

- Express dCas9-repressor fusion and guide RNA in host cells

- Sort low-GFP populations via FACS

- Isolate and sequence plasmids to identify functional PAM motifs

In Vitro Cleavage Selection

This biochemical approach incubates purified Cas nuclease with a DNA library containing randomized PAM regions, followed by sequencing of cleaved products to identify functional PAMs [23].

Protocol:

- Synthesize double-stranded DNA library with target sequence and randomized PAM region

- Incubate with purified Cas nuclease and guide RNA

- Isolate cleaved DNA fragments

- Sequence to determine PAM preferences

Table 2: PAM Identification Methods Comparison

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Required Resources | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Depletion | Survival of non-targeted plasmids | Medium | Expression system, NGS | Works in living cells |

| PAM-SCANR | Transcriptional repression of reporter | High | FACS, dCas9-repressor | Quantitative results |

| In Vitro Cleavage | Direct sequencing of cleaved DNA | High | Purified proteins, NGS | Controlled conditions |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | Protospacer alignment | Highest | Sequencing databases | Identifies natural PAMs |

PAM Diversity and Engineering

Natural PAM Diversity Across CRISPR Systems

The diversity of naturally occurring CRISPR systems provides researchers with an extensive toolkit of Cas nucleases with varying PAM requirements. This natural variation reflects evolutionary adaptation to different viral environments and enables targeting of distinct genomic regions [20] [23].

Class 2 CRISPR systems (including Cas9 and Cas12 proteins) demonstrate remarkable PAM diversity:

- Type II systems (Cas9): Typically recognize short PAM sequences (2-5 bp) adjacent to the target

- Type V systems (Cas12): Often recognize T-rich PAM sequences located upstream of the target

- Type VI systems (Cas13): Target RNA and utilize protospacer flanking sites (PFS) rather than PAMs [23]

Engineered Cas Variants with Altered PAM Specificity

Protein engineering approaches have generated Cas variants with expanded or altered PAM recognition, dramatically increasing targeting scope:

- xCas9: Recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs, broadening targeting range

- SpCas9-NG: Engineered to recognize NG PAMs instead of NGG

- SpRY: Near-PAMless variant recognizing NRN and to some extent NYN PAMs

- Engineered Cas12 variants: Such as hfCas12Max with simplified TN PAM requirement [20]

These engineered variants employ directed evolution and structure-based design to modify PAM-interacting domains while maintaining nuclease activity, enabling targeting of previously inaccessible genomic regions.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAM Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Expression Vector | Expresses Cas protein in target cells | SpCas9, SaCas9, LbCas12a |

| Guide RNA Cloning System | Enables programmable target recognition | sgRNA scaffold, crRNA expression |

| PAM Library Constructs | Randomized DNA sequences for PAM characterization | Plasmid depletion assays |

| dCas9-Repressor Fusions | Binds DNA without cleavage for PAM-SCANR | KRAB-dCas9, dCas9-Mxi1 |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Sequences PAM regions after selection | Illumina-compatible kits |

| Fluorescent Reporter Systems | Reports Cas binding via fluorescence | GFP under constitutive promoter |

| Cell Sorting Capability | Separates cells based on PAM activity | FACS with GFP detection |

| Cas1-Cas2 Complex | Studies spacer acquisition preferences | In vitro adaptation assays |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

PAM Considerations in Therapeutic Development

The transition of CRISPR technology from research tool to clinical application introduces additional PAM-related considerations. Therapeutic efficacy depends on targeting specific genomic loci, which may be constrained by PAM availability [12]. Key developments include:

- CASGEVY (exagamglogene autotemcel): The first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia utilizes ex vivo editing where PAM availability is carefully mapped near the BCL11A enhancer target [12]

- In Vivo Therapies: Intellia Therapeutics' NTLA-2001 for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis demonstrates systemic CRISPR delivery, requiring comprehensive PAM analysis at the TTR gene [12]

- Personalized Therapies: The first bespoke in vivo CRISPR treatment for CPS1 deficiency highlights how PAM mapping enables rapid therapeutic development for ultra-rare diseases [12]

PAM-Dependent Safety Considerations

PAM recognition contributes to CRISPR specificity but doesn't eliminate off-target concerns. Advanced therapeutic development employs:

- PAM Blocking Mutations: Engineering Cas variants that require longer or more specific PAMs to reduce off-target effects

- Computational Prediction: Identifying potential off-target sites with similar sequences and NGG PAMs

- GUIDE-Seq: Unbiased identification of off-target sites in clinical applications [21]

Figure 2: Evolution of PAM Understanding from Basic Research to Clinical Application. The timeline shows how PAM knowledge progressed from Bolotin's initial discovery through mechanistic understanding and protein engineering to current clinical applications.

Alexander Bolotin's identification of the PAM sequence provided the crucial missing piece in understanding CRISPR immune function—the mechanism for self versus non-self discrimination. This fundamental insight enabled the reprogramming of CRISPR systems into precise genome editing tools that have revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development.

Future directions in PAM research and application include:

- PAMless Editors: Continued development of truly PAM-independent nucleases for unrestricted targeting

- Disease-Specific Variants: Engineering Cas proteins with PAM preferences matching therapeutic target sites

- Multiplexed Editing: Utilizing Cas proteins with different PAM requirements for simultaneous editing at multiple loci

- Delivery Optimization: Matching PAM requirements with delivery constraints for in vivo applications

The evolution from Bolotin's initial observation to sophisticated clinical applications exemplifies how fundamental microbiological research can drive transformative technological advances. As CRISPR technology continues to mature, the PAM sequence remains central to expanding targeting capabilities while maintaining specificity—the delicate balance that will define the next generation of genome editing therapeutics.

The journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from a curious bacterial repeat sequence to a revolutionary gene-editing tool is a landmark in biotechnology. Initially identified as a component of the adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, which provides heritable immunity against mobile genetic elements by incorporating spacers from foreign DNA into CRISPR loci, the system was repurposed into a highly programmable DNA cleavage tool following the key discovery that the Cas9 nuclease activity is guided by a complex of crRNA and tracrRNA, later simplified to a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [8]. This historical foundation sets the stage for the critical biochemical interrogation of Cas9: to fully harness its potential and safely translate it into therapies, a rigorous, quantitative understanding of its enzymatic behavior is the essential final puzzle piece. This guide details the core experiments and methodologies that define the biochemical character of Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage, providing a resource for researchers driving the next wave of precision medicine.

Core Principles of Cas9-DNA Interaction

The Cas9-sgRNA complex performs target recognition and cleavage through a multi-step mechanism. The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short nucleotide sequence adjacent to the target DNA site, serves as the initial anchor point for Cas9 binding. Following PAM recognition, the sgRNA unwinds the DNA duplex and base-pairs with the target strand (protospacer), forming an R-loop structure that positions the nuclease domains (HNH and RuvC) for cleavage of the complementary and non-complementary DNA strands, respectively [8] [24]. This process is sensitive to allosteric regulation and structural remodeling, which can be influenced by factors such as temperature and the presence of non-specific competitors [25] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism of DNA recognition and cleavage by the Cas9-sgRNA complex.

Quantitative Characterization of Cleavage Kinetics and Specificity

Biochemical characterization yields critical quantitative parameters that predict Cas9 behavior in complex cellular environments. The data below summarize key performance metrics related to editing efficiency, kinetics, and specificity.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters of CRISPR-Cas9 Activity

| Parameter | Description | Experimental Value | Significance / Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous Recombination Efficiency [27] | Efficiency of inserting a large (~45 kb) donor fragment via HDR in mouse ESCs with CRISPR facilitation. | 11% - 16% | Demonstrates significant enhancement of HDR over traditional methods (0.05% efficiency), enabling large-scale genomic engineering. |

| Off-Target Mismatch Tolerance [28] [29] | Number of base pair mismatches between sgRNA and DNA that Cas9 can tolerate while still causing cleavage. | 3 - 5 bp | Underpins the primary risk of off-target editing; a key driver for developing high-fidelity variants. |

| sgRNA Assembly Kinetics [25] | The rate at which Cas9 and sgRNA form an active effector complex, delayed by non-specific RNA competitors. | Sensitive to RNA competitors | Complex formation rate, not just stability, can be a limiting factor in cells, influencing editing efficiency. |

| sgRNA Affinity (Kd) [25] | Equilibrium dissociation constant for Cas9 binding to a truncated sgRNA (lacking stem loops 2 & 3). | ~1 nM | Truncated guides retain high affinity, but their in vivo activity is lower, suggesting kinetics and stability are critical. |

Table 2: PAM Sequence Requirements for Different Cas9 Orthologues

Understanding PAM requirements is essential for determining targetable sites in a genome. The following table summarizes known PAM preferences for several characterized Cas9 proteins.

| Cas9 Orthologue | Source Organism | Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | Implications for Targetable Sequence Space |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spy Cas9 [24] | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG | The most commonly used variant; targets a site every ~8 bp on average in the human genome. |

| Sth1 Cas9 [24] | Streptococcus thermophilus (CRISPR1) | NNAGAAW (W = A or T) | Requires a longer, more specific PAM, drastically reducing potential target sites but increasing intrinsic specificity. |

| Sth3 Cas9 [24] | Streptococcus thermophilus (CRISPR3) | NGGNG | A relaxed PAM compared to Sth1, but still more constrained than Spy Cas9. |

| Blat Cas9 [24] | Brevibacillus laterosporus | NNNCNDD (D = A, G, or T) | Showcases the diversity of natural PAM sequences, expanding the toolbox for orthogonal genome editing. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Biochemical Characterization

Temperature-Dependent DNA Cleavage Assay

This protocol, adapted from established methods, is crucial for characterizing Cas9 enzymes from extremophiles or engineering variants with altered thermal stability [26]. It allows for qualitative and quantitative assessment of DNA cleavage efficiency across a broad temperature range.

Graphical Overview of Temperature-Dependent Cleavage Assay

Detailed Protocol Steps

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Incubate purified recombinant Cas9 protein with a molar excess of in vitro transcribed or synthetic sgRNA in a suitable binding buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl₂). A typical reaction uses 3 nM Cas9 and 5 nM sgRNA [25].

- Thermocycling: Subject the RNP mixture to a brief thermocycling protocol (e.g., 37°C for 10 min, followed by a slow ramp-down to room temperature) to facilitate proper complex formation.

- Temperature-Dependent Cleavage Reaction:

- Prepare reaction mixtures containing the pre-formed RNP complex and target DNA (e.g., a PCR-amplified fragment or plasmid containing the target protospacer and PAM).

- Distribute the mixture into separate PCR tubes and incubate them at different temperatures (e.g., from 25°C to 75°C) for a fixed duration (e.g., 30-60 minutes). The 5× reaction buffer final concentrations are 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM DTT, and 25% (w/v) glycerol [26].

- Reaction Termination: Stop the cleavage reaction by adding Proteinase K (e.g., 20 mg/mL stock) and incubating at 56°C for 15-30 minutes to digest the Cas9 protein.

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis:

- Purify the DNA and resolve the products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Visualize the DNA bands with a fluorescent nucleic acid stain (e.g., GelRed). The intact supercoiled/linear DNA substrate and the smaller cleaved products will be separated, allowing for quantification of the cleavage efficiency via densitometry.

In Vitro Determination of Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Requirements

Empirically defining the PAM sequence is a prerequisite for deploying any novel Cas9 orthologue. This method uses a randomized plasmid library to directly identify sequences that support Cas9 cleavage [24].

Workflow for Empirical PAM Determination

Detailed Protocol Steps

- Randomized PAM Library Construction: Clone a DNA oligonucleotide containing a fixed protospacer sequence (complementary to the sgRNA spacer) followed by a stretch of fully randomized nucleotides (e.g., 5-7 bp) into a plasmid vector. Transform into E. coli to generate a comprehensive library of potential PAM sequences [24].

- In Vitro Digestion: Isolate the plasmid library and digest it with purified Cas9 pre-loaded with the corresponding sgRNA. Use a range of Cas9 concentrations to assess cleavage efficiency in a dose-dependent manner.

- Capture of Cleaved Products: Ligate specific adapters to the blunt ends generated by Cas9 cleavage. To increase ligation efficiency, the ends can be tailed with a single dA nucleotide, and the adapters can contain a complementary dT overhang.

- PCR Enrichment and Sequencing: Amplify the cleaved (and now adapter-ligated) plasmid fragments using a primer binding to the adapter and another primer adjacent to the randomized PAM region. Subject the resulting PCR amplicons to deep sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify the PAM sequences by extracting the randomized region from sequencing reads that perfectly match the flanks of the protospacer. Generate a position frequency matrix (PFM) and sequence logo to visualize the PAM consensus [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful biochemical characterization relies on high-quality, well-defined reagents. The following table lists essential components for the experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cas9 Biochemical Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The core effector enzyme. Can be wild-type (wtCas9), catalytically dead (dCas9), or high-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1). | Requires high purity (>95%). Purification often involves affinity tags (e.g., His-tag). Source (mesophile vs. thermophile) determines optimal assay temperature [25] [26]. |

| In Vitro Transcribed or Synthetic sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to the specific DNA target. | Full-length sgRNAs (with all 3 stem loops) show superior performance and stability in vivo. Chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs (e.g., with 2'-O-Me, PS bonds) can enhance stability and reduce off-target effects [25] [29]. |

| Target DNA Substrate | The molecule to be cleaved. Can be a short double-stranded DNA oligo (e.g., "Cas9 beacon"), a PCR amplicon, or a plasmid. | Must contain the target protospacer and a functional PAM. Plasmid-based substrates are common for initial validation and PAM determination assays [25] [24]. |

| 5× In Vitro Cleavage Buffer [26] | Provides optimal ionic and pH conditions for Cas9 activity. | A typical recipe includes: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM DTT, and 25% glycerol. DTT should be added fresh. |

| Proteinase K | Terminates the cleavage reaction by digesting the Cas9 protein. | Prevents further cleavage during downstream analysis steps like gel loading [26]. |

| Cas9 Beacon / FRET Probes [25] | Fluorophore-quencher labeled dsDNA probes for real-time kinetic measurements of RNP assembly and DNA binding. | Allows for rapid quantification of binding kinetics and inhibition without gel electrophoresis. The signal increases upon Cas9 binding and strand displacement. |

Addressing the Critical Challenge of Off-Target Effects

A primary safety concern in therapeutic applications is off-target editing, where Cas9 cleaves unintended genomic sites with sequence similarity to the sgRNA. Biochemical studies have shown that wild-type Cas9 can tolerate up to 3-5 base pair mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA, depending on their position and distribution [28] [29].

Multiple strategies have been developed to mitigate this risk, informed by biochemical characterization:

- High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered mutants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) with redesigned protein-DNA interfaces to reduce tolerance for mismatches.

- Optimized sgRNA Design: Careful selection of sgRNAs with high predicted on-target activity and minimal homology to other genomic sites using in silico tools (e.g., CRISPOR). Guides with higher GC content and specific lengths (17-20 nt) can improve specificity [29].

- Alternative CRISPR Systems: Using Cas9 orthologues with longer or more complex PAM requirements (e.g., Sth1 Cas9) naturally reduces the number of potential off-target sites in the genome [24].

- RNP Delivery: The use of pre-assembled Cas9 protein-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, as opposed to plasmid DNA encoding the components, shortens the cellular exposure time to the nuclease, thereby reducing off-target activity [29].

- Advanced Detection Methods: Unbiased methods like GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) are employed to empirically identify off-target sites in relevant cell models, moving beyond purely computational prediction [28] [30] [29].

The Engineering Leap: Reprogramming CRISPR for Biomedical Applications

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and their associated Cas proteins originated from the study of an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes. This system allows bacteria and archaea to defend themselves against mobile genetic elements, such as viruses, by integrating short snippets of foreign DNA (spacers) into their own genome. These spacers, transcribed into short RNA molecules, then guide Cas nucleases to cleave complementary invading DNA sequences in a sequence-specific manner [8] [31]. The journey from this fundamental biological discovery to a revolutionary genome-editing tool was marked by key breakthroughs. A critical simplification came in 2012 when Jinek et al. demonstrated that the dual RNA components of the native system—the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA)—could be fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [8] [5]. This created a two-component system where the Cas9 nuclease could be programmed with a single RNA molecule to cut any DNA sequence complementary to the guide and adjacent to a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [32]. While this work established a programmable DNA-cutting enzyme in vitro, the pivotal paradigm shift occurred in early 2013, when multiple research groups independently demonstrated that this engineered CRISPR-Cas9 system could be harnessed to edit the genomes of eukaryotic cells [5] [32].

The Eukaryotic Breakthrough: Key Experimental Demonstrations

The successful adaptation of CRISPR-Cas9 for eukaryotic genome editing was a watershed moment, transforming the system from a powerful biochemical tool into a transformative technology for genetic research and therapy. The key challenge was to demonstrate that the bacterial Cas9-sgRNA complex could function within the more complex environment of a eukaryotic cell, which includes navigating the cytoplasm and entering the nucleus.

Landmark Publications of January 2013

Within a week in January 2013, two seminal papers were published that conclusively showed CRISPR-Cas9 could mediate genome editing in human and mouse cells.

Zhang Lab (Broad Institute/MIT): On January 3, a team led by Feng Zhang published the first report demonstrating CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in eukaryotic cells [5] [33]. Their work, published in Science, showed that the system could be used for targeted gene disruption and homology-directed repair (HDR) in human and mouse cells [5] [32]. A critical technical hurdle they overcame was the adaptation of the bacterial Cas9 for expression and function in mammalian cells. This involved codon-optimizing the Cas9 gene from Streptococcus pyogenes to enhance its expression in human cells and appending a nuclear localization signal (NLS) to the protein to ensure its transport into the nucleus [33]. They also developed expression strategies for the sgRNA using a U6 polymerase III promoter, which is efficient for producing small RNAs in mammalian cells [33] [32].

Church Lab (Harvard University): In the same issue of Science, a team led by George Church reported similar success, showing targeted genome editing in human cells [5]. This concurrent publication provided immediate, independent validation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system's functionality and versatility in eukaryotes, a critical factor for its rapid adoption by the scientific community.

The following table summarizes the core methodological details from these foundational studies:

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters from Landmark 2013 Eukaryotic CRISPR Studies

| Experimental Parameter | Zhang Lab (Cong et al.) | Church Lab (Mali et al.) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines Tested | Human (HEK293) & Mouse (N2a) cells | Human (HEK293) cells |

| Target Genes | EMX1, PVALB (human); Th (mouse) | EMX1, PVALB |

| Cas9 Source | Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) | Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) |

| Key Adaptations | Codon-optimized Cas9; Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) | Codon-optimized Cas9; Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) |

| Delivery Method | Plasmid transfection | Plasmid transfection |

| Editing Demonstrated | Multiplex gene editing; Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Gene disruption; HDR |

| Efficiency Reported | HDR efficiency of up to 38% (varies by locus) | Indel formation of 2% to 38% (varies by locus) |

Technical Hurdles and Innovative Solutions

The transition from a prokaryotic immune system to a eukaryotic editing tool required solving several key problems, as outlined in the workflow below. The teams led by Zhang and Church developed similar and critical solutions to enable this paradigm shift.

Diagram 1: Overcoming Technical Hurdles for Eukaryotic CRISPR

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Reagents for Early Eukaryotic CRISPR

The initial demonstrations of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells relied on a core set of engineered reagents that became the foundation for all subsequent applications. These components solved the critical problems of expression, localization, and function within a mammalian cellular environment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Eukaryotic CRISPR-Cas9

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Description | Role in Eukaryotic Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Cas9 | A version of the Cas9 gene where the nucleotide sequence is altered to match the codon usage bias of the target organism (e.g., human) without changing the amino acid sequence. | Dramatically improves the efficiency of Cas9 protein expression in mammalian cells [33] [32]. |

| Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) | A short amino acid sequence fused to the Cas9 protein, which acts as a "molecular zip code" to direct the protein through nuclear pores and into the nucleus. | Essential for targeting the Cas9 nuclease to the genomic DNA within the nucleus [33] [32]. |

| sgRNA Expression Cassette | A DNA construct, typically using the U6 small nuclear RNA promoter, to drive high-level expression of the single-guide RNA within the nucleus of mammalian cells. | Ensures robust production of the guide RNA component in the correct cellular compartment [33] [32]. |