Encoder-Only vs. Decoder-Only Models: A Specialist's Guide for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and professionals in drug discovery on the strategic selection and application of encoder-only and decoder-only large language models.

Encoder-Only vs. Decoder-Only Models: A Specialist's Guide for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and professionals in drug discovery on the strategic selection and application of encoder-only and decoder-only large language models. It covers foundational architectural principles, details specific methodological applications in biomedical research—from target identification to clinical data processing—and offers practical optimization strategies. A rigorous comparative analysis equips readers to validate and choose the right model architecture, balancing efficiency, accuracy, and computational cost to accelerate and improve outcomes in pharmaceutical development.

Understanding the Core Architectures: From Transformers to Specialized LLMs

The transformer architecture, since its inception, has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of artificial intelligence and natural language processing. Its evolution has bifurcated into two predominant paradigms: encoder-only and decoder-only architectures, each with distinct computational characteristics and application domains. Encoder-only models, such as BERT and RoBERTa, utilize bidirectional attention mechanisms to develop deep contextual understanding of input text, making them exceptionally suited for interpretation tasks like sentiment analysis and named entity recognition [1]. Conversely, decoder-only models like the GPT series employ masked self-attention mechanisms that prevent the model from attending to future tokens, making them inherently autoregressive and optimized for text generation tasks [2] [1]. This architectural divergence represents more than mere implementation differences—it embodies fundamentally opposed approaches to language modeling that continue to drive innovation across research domains, including pharmaceutical development where both understanding and generation capabilities find critical applications [3].

The ongoing debate surrounding these architectures has gained renewed momentum with recent research challenging the prevailing dominance of decoder-only models. Studies demonstrate that encoder-decoder models, when enhanced with modern training methodologies, can achieve comparable performance to decoder-only counterparts while offering superior inference efficiency in certain contexts [4]. This resurgence of interest in encoder-decoder architectures coincides with growing concerns about computational efficiency and specialized domain applications, particularly in scientific fields like drug discovery where both comprehensive understanding and controlled generation are essential [3]. As we deconstruct these architectural blueprints, it becomes evident that the optimal choice depends heavily on specific task requirements, computational constraints, and desired outcome metrics.

Architectural Fundamentals: Encoder vs. Decoder

Encoder-Decoder Architecture

The original transformer architecture, as proposed in "Attention Is All You Need," integrated both encoder and decoder components working in tandem for sequence-to-sequence tasks like machine translation [1]. In this framework, the encoder processes the input sequence bidirectionally, meaning it can attend to all tokens in the input simultaneously—both preceding and following tokens—to create a rich, contextual representation of the entire input [5] [1]. This comprehensive understanding is then passed to the decoder, which generates the output sequence autoregressively, one token at a time, while attending to both the encoder's output and its previously generated tokens [1].

The encoder's bidirectional processing capability enables it to develop a holistic understanding of linguistic context, capturing nuanced relationships between words regardless of their positional relationships [1]. This characteristic makes encoder-focused models particularly valuable for tasks requiring deep comprehension, such as extracting meaningful patterns from scientific literature or identifying complex biomolecular relationships in pharmaceutical research [3]. The encoder's output represents the input sequence in a dense, contextualized embedding space that can be leveraged for various downstream predictive tasks.

Decoder-Only Architecture

Decoder-only architectures emerged as a simplification of the full encoder-decoder model, eliminating the encoder component entirely and relying exclusively on the decoder stack with masked self-attention [2] [1]. This architectural variant processes input unidirectionally, with each token only able to attend to previous tokens in the sequence, not subsequent ones [5] [2]. This causal masking mechanism ensures the model cannot "look ahead" at future tokens during training, making it inherently predictive and ideally suited for generative tasks [2].

The dominance of decoder-only architectures in contemporary LLMs stems from their remarkable generative capabilities and emergent properties [1]. Through pretraining on vast text corpora using simple next-token prediction objectives, these models develop sophisticated language understanding alongside generation abilities, enabling few-shot learning and in-context adaptation without parameter updates [1]. This combination of architectural simplicity and functional power has established decoder-only models as the default choice for general-purpose language modeling, though recent research suggests this dominance may not be universally justified across all application domains [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Encoder and Decoder Architectures

| Architectural Aspect | Encoder Models | Decoder Models | Encoder-Decoder Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Mechanism | Bidirectional (attends to all tokens) | Causal/masked (attends only to previous tokens) | Encoder: Bidirectional; Decoder: Causal |

| Primary Training Objective | Masked language modeling, next sentence prediction | Next token prediction | Sequence-to-sequence reconstruction |

| Information Flow | Comprehensive context understanding | Autoregressive generation | Understanding → Generation |

| Typical Applications | Text classification, sentiment analysis, information extraction | Text generation, conversational AI, code generation | Machine translation, text summarization, question answering |

| Example Models | BERT, RoBERTa | GPT series, Llama, Gemma | T5, BART, T5Gemma |

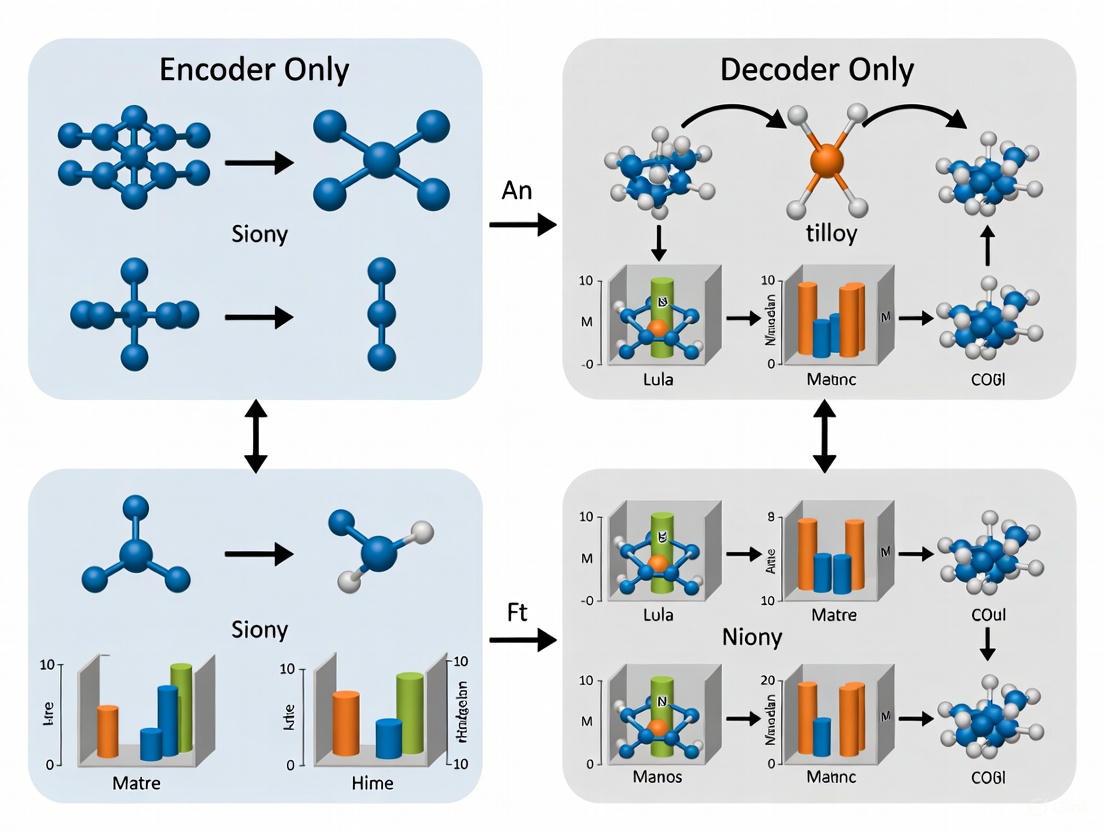

Visualizing Architectural Differences

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in information flow between encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder architectures:

Architecture Comparison: Information flow differences between transformer variants.

Empirical Analysis: Performance Comparison

Scaling Properties and Efficiency Metrics

Recent comparative studies have systematically evaluated the scaling properties of encoder-decoder versus decoder-only architectures across model sizes ranging from ~150M to ~8B parameters [4]. These investigations reveal nuanced trade-offs that challenge the prevailing preference for decoder-only models. When pretrained on the RedPajama V1 dataset (1.6T tokens) and instruction-tuned using FLAN, encoder-decoder models demonstrate compelling scaling properties and surprisingly strong performance despite receiving less research attention in recent years [4].

While decoder-only architectures generally maintain an advantage in compute optimality during pretraining, encoder-decoder models exhibit comparable scaling capabilities and context length extrapolation [4]. More significantly, after instruction tuning, encoder-decoder architectures achieve competitive and occasionally superior results on various downstream tasks while offering substantially better inference efficiency [4]. This efficiency advantage stems from the architectural separation of understanding and generation capabilities, allowing for computational optimization that might be particularly valuable in resource-constrained environments like research institutions or for deploying models at scale in production systems.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Architectural Paradigms (150M to 8B Scale)

| Evaluation Metric | Decoder-Only Models | Encoder-Decoder Models | Performance Differential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining Compute Optimality | High | Moderate | Decoder-only more compute-efficient during pretraining |

| Inference Efficiency | Moderate | High | Encoder-decoder substantially more efficient after instruction tuning |

| Context Length Extrapolation | Strong | Comparable | Similar capabilities demonstrated |

| Instruction Tuning Response | Strong | Strong | Both architectures respond well to instruction tuning |

| Downstream Task Performance | Varies by task | Comparable/Superior on some tasks | Encoder-decoder competitive and occasionally better |

| Training Data Requirements | Typically high (100B+ tokens) | Potentially lower (e.g., 100B tokens) | Encoder-decoder may require less data for similar performance |

Specialized Architectural Innovations

Beyond the fundamental encoder-decoder dichotomy, numerous specialized architectural innovations have emerged to address specific limitations of standard transformer architectures. DeepSeek's Multi-head Latent Attention (MLA) represents a significant advancement for long-context inference by reducing the size of the KV cache without compromising model quality [6]. Traditional approaches like grouped-query attention and KV cache quantization inevitably involve trade-offs between cache size and model performance, whereas MLA employs low-rank compression of key and value vectors while maintaining essential information through clever recomputation techniques [6].

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models constitute another transformative architectural evolution, decoupling model knowledge from activation costs by dividing feedforward blocks into multiple experts with context-dependent routing mechanisms [6]. This approach enables dramatic parameter count increases without proportional computational cost growth, though it introduces challenges like routing collapse where models persistently activate the same subset of experts [6]. DeepSeek v3 addresses this through auxiliary-loss-free load balancing and shared expert mechanisms that maintain training stability while leveraging MoE benefits [6].

The following diagram illustrates the key innovations in modern efficient transformer architectures:

Efficient Architecture Innovations: Key advancements improving transformer scalability.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comparative Scaling Studies

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for meaningful architectural comparisons. Recent encoder-decoder versus decoder-only studies employ standardized training and evaluation pipelines that isolate architectural effects from other variables [4]. The pretraining phase utilizes the RedPajama V1 dataset comprising 1.6T tokens, with consistent preprocessing and tokenization across experimental conditions [4]. Models across different scales (from ~150M to ~8B parameters) undergo training with carefully controlled compute budgets, enabling direct comparison of scaling properties and training efficiency.

During instruction tuning, researchers employ the FLAN collection with identical procedures applied to all architectural variants [4]. Evaluation encompasses diverse downstream tasks including reasoning, knowledge retrieval, and specialized domain applications, with metrics normalized to account for parameter count differences [4]. This methodological rigor ensures observed performance differences genuinely reflect architectural characteristics rather than training or evaluation inconsistencies.

Text-to-Image Generation Conditioning Analysis

Beyond traditional language tasks, specialized experimental protocols have been developed to evaluate architectural components in multimodal contexts. Studies investigating decoder-only LLMs as text encoders for text-to-image generation employ standardized training and evaluation pipelines that isolate the impact of different text embeddings [7]. Researchers train 27 text-to-image models with 12 different text encoders while controlling for all other variables, enabling precise attribution of performance differences to architectural features [7].

These experiments systematically analyze critical aspects including embedding extraction methodologies (last-layer vs. layer-normalized averaging across all layers), LLM variants, and model sizes [7]. The findings demonstrate that conventional last-layer embedding approaches underperform compared to more sophisticated layer-normalized averaging techniques, which significantly improve alignment with complex prompts and enhance performance in advanced visio-linguistic reasoning tasks [7]. This methodological approach exemplifies how controlled experimentation can reveal optimal configuration patterns for specific application domains.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "research reagents" – essential components and methodologies used in modern transformer architecture research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transformer Architecture Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Causal Self-Attention | Enables autoregressive generation by masking future tokens | PyTorch module with masked attention matrix [2] |

| Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) | Encodes positional information without increasing parameters | Standard implementation in models like Supernova [8] |

| Grouped Query Attention (GQA) | Reduces KV cache size by grouping query heads | 3:1 compression ratio used in Supernova [8] |

| Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA) | Advanced KV cache compression without quality loss | DeepSeek's latent dimension approach [6] |

| Mixture of Experts (MoE) | Increases parameter count without proportional compute increase | DeepSeek v3's auxiliary-loss-free load balancing [6] |

| RMSNorm | Computational efficiency improvement over LayerNorm | Used in efficient architectures like Supernova [8] |

| SwiGLU Activation | Enhanced activation function for feedforward networks | Modern alternative to ReLU/GELU [8] |

| Layer-Normalized Averaging | Extracts embeddings across all layers for better conditioning | Superior to last-layer embeddings in text-to-image [7] |

Domain-Specific Applications: Drug Discovery Case Study

The architectural dichotomy between encoder and decoder models takes on particular significance in specialized domains like pharmaceutical research, where both comprehension and generation capabilities are essential. Foundation models have demonstrated remarkable growth in drug discovery applications, with over 200 specialized models published since 2022 supporting diverse applications including target discovery, molecular optimization, and preclinical research [3].

Encoder-style architectures excel in analyzing existing biomedical literature, extracting relationships between chemical structures and biological activity, and predicting molecular properties—tasks requiring deep understanding of complex domain-specific contexts [3] [1]. Their bidirectional attention mechanisms enable comprehensive analysis of molecular structures and biomedical relationships, making them invaluable for target identification and validation phases. Decoder architectures, conversely, demonstrate exceptional capability in generative tasks like molecular design, compound optimization, and synthesizing novel chemical entities with desired properties [3] [5].

The emerging hybrid approach leverages both architectural paradigms in coordinated workflows, with encoder-style models identifying promising therapeutic targets through literature analysis and biological pathway understanding, while decoder-style models generate novel molecular structures targeting these pathways [3]. This synergistic application represents the cutting edge of AI-driven pharmaceutical research, demonstrating how architectural differences can be transformed from theoretical distinctions into complementary tools addressing complex real-world challenges.

The deconstruction of transformer architectures reveals a dynamic landscape where encoder-decoder and decoder-only paradigms each offer distinct advantages depending on application requirements and computational constraints. Recent research challenging decoder-only dominance suggests the AI community may have prematurely abandoned encoder-decoder architectures, which demonstrate compelling performance and efficiency characteristics when enhanced with modern training methodologies [4].

Future architectural evolution will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both paradigms while integrating specialized innovations like Multi-head Latent Attention for efficient long-context processing [6] and Mixture-of-Experts models for scalable parameter increases [6]. For scientific applications like drug discovery, domain-adapted architectures that incorporate specialized embeddings, structured knowledge mechanisms, and multi-modal capabilities will increasingly bridge the gap between general language modeling and specialized research needs [3].

The optimal architectural blueprint remains context-dependent, with decoder-only models maintaining advantages in general-purpose generation, while encoder-decoder architectures offer compelling efficiency for specific understanding-to-generation workflows [4] [5]. As transformer architectures continue evolving, this nuanced understanding of complementary strengths rather than absolute superiority will guide more effective application across research domains, from pharmaceutical development to specialized scientific discovery.

In the landscape of transformer architectures, encoder-only models represent a distinct paradigm specifically engineered for deep language understanding rather than text generation. Models like BERT, RoBERTa, and the recently introduced ModernBERT utilize a bidirectional attention mechanism, allowing them to process all tokens in an input sequence simultaneously while accessing both left and right context for each token [9] [10] [11]. This fundamental architectural characteristic makes them exceptionally powerful for comprehension tasks where holistic understanding of the input is paramount.

Unlike decoder-only models that process text unidirectionally (left-to-right) and excel at text generation, encoder-only models are trained using objectives like Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where randomly masked tokens must be predicted using surrounding context from both directions [9] [12]. This training approach produces highly contextualized embeddings that capture nuanced semantic relationships, making these models particularly suitable for scientific and industrial applications requiring precision, efficiency, and robust language understanding without the computational overhead of generative models [13] [12].

Architectural Framework and Core Mechanisms

Fundamental Components

The encoder-only architecture consists of stacked transformer encoder layers, each containing two primary sub-components [10]:

- Self-Attention Layer: Computes attention weights between all token pairs in the input sequence, enabling each token to contextualize itself against all others bidirectionally.

- Feed-Forward Neural Network: Further processes the contextualized representations through position-wise fully connected layers.

A critical differentiator from decoder architectures is the absence of autoregressive masking in the attention mechanism. Without masking constraints, the self-attention layers can establish direct relationships between any tokens in the sequence, regardless of position [10] [11].

Visualizing Bidirectional Attention

The following diagram illustrates the bidirectional attention mechanism that enables each token to contextualize itself against all other tokens in the input sequence:

Diagram 1: Bidirectional attention in encoder-only models. Each output embedding derives context from all input tokens.

Training Methodology: Masked Language Modeling

The core training objective for most encoder-only models is Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where:

- 15% of input tokens are randomly replaced with a

[MASK]token - The model must predict the original tokens using bidirectional context

- Unlike autoregressive training, predictions can utilize both preceding and subsequent tokens [9]

Additional pretraining objectives like Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) help the model understand relationships between sentence pairs, further enhancing representation quality for tasks requiring cross-sentence reasoning [9].

Performance Comparison: Encoder vs. Decoder Architectures

Task-Specific Capabilities

Different transformer architectures demonstrate distinct strengths based on their structural designs:

Table 1: Architectural suitability for NLP tasks

| Task Category | Suggested Architecture | Examples | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text Classification | Encoder-only | BERT, RoBERTa, ModernBERT | Bidirectional context enables holistic understanding [11] |

| Named Entity Recognition | Encoder-only | BERT, RoBERTa | Full context needed for entity boundary detection [11] |

| Text Generation | Decoder-only | GPT, LLaMA | Autoregressive design matches sequential generation [5] [11] |

| Machine Translation | Encoder-Decoder | T5, BART | Combines understanding (encoder) with generation (decoder) [11] |

| Summarization | Encoder-Decoder | BART, T5 | Requires comprehension then abstraction [11] |

| Question Answering (Extractive) | Encoder-only | BERT, RoBERTa | Context matching against full passage [11] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Recent empirical studies directly compare architectural performance across various natural language understanding tasks:

Table 2: Performance comparison on classification tasks (accuracy %)

| Model Architecture | Model Name | Sentiment Analysis | Intent Classification | Enhancement Report Approval | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-only | BERT-base | 92.5 | 94.2 | 73.1 | ~110M [14] [13] |

| Encoder-only | RoBERTa-base | 93.1 | 94.8 | 74.3 | ~125M [14] [13] |

| Encoder-only | ModernBERT-base | 95.7 | 96.2 | N/A | ~149M [12] |

| Decoder-only | LLaMA 3.1 8B | 89.3 | 90.1 | 79.0* | ~8B [14] [13] |

| Decoder-only | GPT-3.5-turbo | 90.8 | 91.5 | 75.2 | ~20B [14] |

| Traditional | LSTM+GloVe | 88.7 | 89.3 | 68.5 | ~50M [14] |

Note: LLaMA 3.1 8B achieved 79% accuracy on Enhancement Report Approval Prediction only after LoRA fine-tuning and incorporation of creator profile metadata [14]

Efficiency and Inference Metrics

Beyond raw accuracy, encoder models demonstrate significant advantages in computational efficiency:

Table 3: Computational efficiency comparison

| Metric | Encoder-only (ModernBERT-base) | Decoder-only (LLaMA 3.1 8B) | Advantage Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inference Speed (tokens/sec) | ~2,400 | ~380 | 6.3× [12] |

| Memory Footprint | ~0.6GB | ~16GB | ~26× [12] |

| Context Length | 8,192 tokens | 8,000 tokens | Comparable [12] |

| Monthly Downloads (HF) | ~1 billion | ~397 million | ~2.5× [12] |

The efficiency advantage is particularly pronounced in filtering applications. Processing 15 trillion tokens with a fine-tuned BERT model required 6,000 H100 hours (~$60,000), while the same task using decoder-only APIs would exceed $1 million [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Evaluation Workflow

Research comparing architectural performance typically follows rigorous experimental protocols:

Diagram 2: Standard experimental workflow for architectural comparison studies.

Key Experimental Design Elements

- Dataset Curation: Studies utilize established benchmarks (GLUE, SuperGLUE) and domain-specific corpora [14] [12]

- Fine-tuning Protocols: Encoder models typically use task-specific heads with cross-entropy loss; decoder models employ instruction tuning or LoRA [14]

- Evaluation Metrics: Standard classification metrics (accuracy, F1, precision, recall) with statistical significance testing [14] [13]

- Computational Controls: Experiments control for parameter count, training data size, and computational budget [4] [13]

For example, the Enhancement Report Approval Prediction study evaluated 18 LLM variants using strict chronological data splitting to prevent temporal bias, with comprehensive hyperparameter optimization for each architecture [14].

Table 4: Key research reagents and resources for encoder model experimentation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretrained Models | BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTa, ModernBERT | Foundation models for transfer learning | Hugging Face Hub [12] |

| Datasets | GLUE, SuperGLUE, domain-specific corpora | Benchmark performance evaluation | Academic repositories [14] [12] |

| Fine-tuning Frameworks | Transformers, Adapters, LoRA | Task-specific model adaptation | Open-source libraries [14] |

| Evaluation Suites | Scikit-learn, Hugging Face Evaluate | Standardized performance metrics | Python packages [14] |

| Computational Resources | GPU clusters, cloud computing | Model training and inference | Institutional/cloud providers |

Encoder-only models provide a computationally efficient yet highly effective architecture for natural language understanding tasks predominant in scientific research and industrial applications. Their bidirectional contextualization capabilities deliver state-of-the-art performance on classification, information extraction, and similarity analysis tasks while requiring substantially fewer computational resources than decoder-only alternatives [13] [12].

The recent introduction of ModernBERT demonstrates that ongoing architectural innovations continue to enhance encoder capabilities, including extended context lengths (8K tokens) and improved training methodologies [12]. For research institutions and development teams operating under computational constraints, encoder-only models represent a Pareto-optimal solution, balancing performance with practical deployability.

As the field evolves, the strategic combination of encoder-only models for comprehension tasks and decoder models for generation scenarios enables the development of sophisticated NLP pipelines that maximize both capability and efficiency—a consideration particularly relevant for resource-constrained research environments.

The field of natural language processing has witnessed a significant architectural evolution, transitioning from encoder-dominated paradigms to the current era dominated by decoder-only models. This shift represents more than a mere architectural preference; it reflects a fundamental rethinking of how machines learn, understand, and generate human language. Decoder-only models, characterized by their autoregressive design, predict the next token in a sequence based on all previous tokens, enabling powerful text generation capabilities that underpin modern systems like GPT-4, LLaMA, and Claude [15] [1].

Within the broader research context comparing encoder-only versus decoder-only architectures, this guide objectively examines the performance, experimental protocols, and practical applications of decoder-only models. While encoder-only models like BERT excel in understanding tasks through bidirectional context, and encoder-decoder hybrids like T5 handle sequence-to-sequence tasks, decoder-only architectures have demonstrated remarkable versatility and scaling properties, often achieving state-of-the-art results in both generative and discriminative tasks when sufficiently scaled [16] [17]. This analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive comparison grounded in experimental data and methodological details.

Architectural Comparison and Performance Analysis

Key Architectural Differences

The fundamental distinction between architectural paradigms lies in their attention mechanisms and training objectives. Encoder-only models utilize bidirectional self-attention, meaning each token in the input sequence can attend to all other tokens, creating a rich, contextual understanding ideal for classification and extraction tasks [1] [16]. In contrast, decoder-only models employ masked self-attention, where each token can only attend to previous tokens in the sequence, making them inherently autoregressive and optimized for text generation [1]. Encoder-decoder models combine both, using bidirectional attention for encoding and masked attention for decoding, suited for tasks like translation where output heavily depends on input structure [1] [16].

A critical theoretical advantage for decoder-only models is their tendency to maintain higher-rank attention weight matrices compared to the low-rank bottleneck observed in bidirectional attention mechanisms [16]. This suggests decoder-only architectures may have greater expressive power, as each token can retain more unique information rather than being homogenized through excessive contextual averaging [16].

Experimental Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance Across Model Architectures

| Model Architecture | Representative Models | Primary Training Objective | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | BERT, RoBERTa | Masked Language Modeling (MLM) | Excellent for classification, semantic understanding, produces high-quality embeddings [1] [17] | Poor at coherent long-form text generation [16] [17] |

| Decoder-Only | GPT series, LLaMA | Autoregressive Language Modeling | State-of-the-art text generation, strong zero-shot generalization, emergent abilities [1] [16] | Can struggle with tasks requiring full bidirectional context [17] |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5, BART | Varied (often span corruption or denoising) | Powerful for sequence-to-sequence tasks (translation, summarization) [1] [17] | Computationally more expensive, less parallelizable than decoder-only [16] |

Table 2: Inference Efficiency and Scaling Properties

| Architecture | Inference Efficiency | Scaling Trajectory | Context Window Extrapolation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | Highly parallelizable during encoding | Performance plateaus at smaller scales [16] | Naturally handles full sequence |

| Decoder-Only | Sequential generation, but innovations like pipelined decoders improve speed [18] | Strong scaling to hundreds of billions of parameters [16] | Demonstrated strong extrapolation capabilities [4] |

| Encoder-Decoder | Moderate, due to dual components | Competitive scaling shown in recent studies [4] | Depends on implementation |

Recent experimental evidence from direct architectural comparisons reveals nuanced performance differences. In a comprehensive study comparing architectures using 50B parameter models pretrained on 170B tokens, decoder-only models with generative pretraining demonstrated superior zero-shot generalization for generative tasks, while encoder-decoder models with masked language modeling performed best for zero-shot MLM tasks but struggled with answering open questions [16].

For inference efficiency, decoder-only models provide compelling advantages. The RADAr model, a transformer-based autoregressive decoder for hierarchical text classification, demonstrated comparable performance to state-of-the-art methods while providing a 2x speed-up at inference time [19]. Further innovations like pipelined decoders show potential for significantly improving generation speed without substantial quality loss or additional memory consumption [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pretraining Methodology for Decoder-Only Models

The training process for decoder-only models follows a self-supervised approach on large-scale text corpora. The fundamental protocol involves:

Data Preparation: Large text collections are processed into sequences of tokens. Each sequence is split into overlapping samples where the input is all tokens up to position i, and the target is the token at position i+1 [15]. For example:

- Input:

["This"]→ Target:"is" - Input:

["This", "is"]→ Target:"a" - Input:

["This", "is", "a"]→ Target:"sample"

- Input:

Autoregressive Objective: The model is trained to predict the next token in a sequence given all previous tokens, formally maximizing the likelihood: P(tokeni | token1, token2, ..., token{i-1}) [15] [1].

Architecture Configuration: A stack of identical decoder layers, each containing:

- Masked multi-head self-attention mechanism

- Feed-forward network (typically a multilayer perceptron)

- Layer normalization and skip connections [15]

Recent advancements have explored unified decoder-only architectures for multimodal tasks. OneCAT, a decoder-only auto-regressive model for unified understanding and generation, demonstrates how a pure decoder-only architecture can integrate understanding, generation, and editing within a single framework, eliminating the need for external vision components during inference [20].

Benchmarking and Evaluation Protocols

Rigorous evaluation of decoder-only models involves multiple benchmarks across different task categories:

- Generative Tasks: HumanEval, MBPP, and CodeContests for code generation; narrative generation tasks for creative writing [21]

- Reasoning Tasks: MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) for general knowledge and problem-solving [21]

- Conversational Quality: MT-Bench for multi-turn dialogue capabilities [21]

- Long-Context Understanding: LongBench for evaluating performance on extended contexts [21]

For specialized domains like STEM question answering, experimental protocols involve generating challenging multiple-choice questions using LLMs themselves, then evaluating model performance with and without context, creating a self-evaluation framework [22].

Efficiency Optimization Techniques

Several innovative methods have been developed to address the sequential decoding limitation of autoregressive models:

Pipelined Decoder Architecture: Initiates generation of multiple subsequences simultaneously, generating a new token for each subsequence at each time step to realize parallelism while maintaining autoregressive properties within subsequences [18].

Modality-Specific Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): Employs expert networks where different parameters are activated for different inputs or modalities, providing scalability without proportional compute cost increases [20] [17].

Architectural Diagrams and Workflows

Decoder-Only Transformer Architecture

Decoder-Only Model Data Flow

Decoder Block Detailed Components

Single Decoder Block Structure

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Components for Decoder-Model Development

| Research Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Base Architecture | Core transformer decoder blocks with autoregressive attention | GPT architecture, LLaMA, RADAr [19] [1] |

| Pretraining Corpora | Large-scale text data for self-supervised learning | RedPajama V1 (1.6T tokens), Common Crawl, domain-specific collections [4] [21] |

| Tokenization Tools | Convert text to model-readable tokens and back | Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), SentencePiece, WordPiece [15] |

| Positional Encoding | Inject sequence position information into embeddings | Learned positional embeddings, rotary position encoding (RoPE) [15] |

| Optimization Frameworks | Efficient training and fine-tuning | AdamW optimizer, learning rate schedulers, distributed training backends [1] |

| Instruction Tuning Datasets | Align model behavior with human instructions | FLAN collection, custom instruction datasets [4] |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | Standardized performance assessment | MMLU, HumanEval, MT-Bench, LongBench [21] |

| Efficiency Libraries | Optimize inference speed and memory usage | vLLM, Llama.cpp, TensorRT-LLM [21] |

The architectural landscape of large language models presents researchers with distinct trade-offs between understanding, generation, and efficiency. Decoder-only models have established dominance in generative applications and shown remarkable scaling properties, while encoder-only models maintain advantages in classification and semantic understanding tasks requiring bidirectional context [16] [17]. Encoder-decoder architectures offer compelling performance for sequence-to-sequence tasks but face efficiency challenges compared to single-stack alternatives [16].

For research and development professionals, selection criteria should extend beyond benchmark performance to include data privacy requirements, computational constraints, customization needs, and integration capabilities with existing scientific workflows [21]. The future of architectural development appears to be leaning toward specialized mixtures-of-experts and unified decoder-only frameworks that can efficiently handle multiple modalities and tasks within a single autoregressive paradigm [20] [17]. As the field progresses, the most impactful applications will likely come from strategically matching architectural strengths to specific research problems rather than pursuing one-size-fits-all solutions.

The rapid evolution of Large Language Models (LLMs) has been characterized by a fundamental architectural schism: the division between encoder-only models designed for comprehension and decoder-only models engineered for generation [1]. This architectural dichotomy is not merely a technical implementation detail but rather a core determinant of functional capability, performance characteristics, and ultimately, suitability for specific scientific applications [23]. In domains such as drug development and materials research, where tasks range from molecular property prediction (comprehension) to novel compound design (generation), understanding this architectural imperative becomes crucial for leveraging artificial intelligence effectively [24].

The original Transformer architecture, introduced in the landmark "Attention Is All You Need" paper, contained both encoder and decoder components working in tandem for sequence-to-sequence tasks like machine translation [1] [25]. However, subsequent research and development has seen these components diverge into specialized architectures, each with distinct strengths, training methodologies, and operational characteristics [16]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these architectures, grounded in experimental data and tailored to the needs of researchers and scientists navigating the complex landscape of AI tools for scientific discovery.

Architectural Fundamentals: How Encoders and Decoders Work

Core Components and Mechanisms

At their core, both encoder and decoder architectures are built upon the same fundamental building block: the self-attention mechanism [2]. However, they implement this mechanism in critically different ways that dictate their functional capabilities:

Encoder Architecture: Encoder-only models like BERT and RoBERTa utilize bidirectional self-attention, meaning each token in the input sequence can attend to all other tokens in both directions [1] [26]. This allows the encoder to develop a comprehensive, contextual understanding of the entire input sequence simultaneously. The training objective typically involves Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where random tokens in the input are masked and the model must predict them based on surrounding context [1] [16].

Decoder Architecture: Decoder-only models such as GPT, LLaMA, and PaLM employ causal (masked) self-attention, which restricts each token from attending to future tokens in the sequence [2] [25]. This unidirectional attention mechanism preserves the autoregressive property essential for text generation, where outputs are produced one token at a time, with each new token conditioned on all previous tokens [1] [2].

Visualizing the Architectural Differences

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how encoder and decoder architectures process information:

Performance Comparison: Experimental Evidence

Quantitative Analysis Across Task Types

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance of encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder architectures across various tasks. The following table summarizes key findings from recent research:

Table 1: Performance comparison of model architectures across different task types

| Architecture | Representative Models | Classification Accuracy | Generation Quality | Inference Speed | Training Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | BERT, RoBERTa, ModernBERT | High [22] [16] | Low [16] | Fast [26] | Moderate [26] | Bidirectional context understanding, efficiency [26] |

| Decoder-Only | GPT-4, LLaMA, PaLM | Moderate (requires scaling) [16] | High [27] [16] | Slow (autoregressive) [23] | High (parallel pre-training) [27] | Text generation, few-shot learning [1] |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5, BART, SMI-TED289M | High [24] | High [24] | Moderate [27] | Low (requires paired data) [27] | Sequence-to-sequence tasks [1] |

Specialized Performance in Scientific Domains

In scientific domains such as chemistry and drug discovery, the performance characteristics of these architectures manifest in specialized ways. A 2025 study introduced SMI-TED289M, an encoder-decoder model specifically designed for molecular analysis [24]. The model was evaluated across multiple benchmark datasets from MoleculeNet, demonstrating the nuanced performance patterns of different architectures in scientific contexts:

Table 2: Performance of SMI-TED289M encoder-decoder model on molecular tasks [24]

| Task Type | Dataset | Metric | SMI-TED289M Performance | Competitive SOTA | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | BBBP | ROC-AUC | 0.921 | 0.897 | Superior |

| Classification | Tox21 | ROC-AUC | 0.854 | 0.851 | Comparable |

| Classification | SIDER | ROC-AUC | 0.645 | 0.635 | Superior |

| Regression | QM9 | MAE | 0.071 | 0.089 | Superior |

| Regression | ESOL | RMSE | 0.576 | 0.580 | Superior |

| Reconstruction | MOSES | Valid/Unique | 0.941/0.999 | 0.927/0.998 | Superior |

The Scaling Perspective: How Model Size Affects Performance

The relationship between architecture and performance is further complicated by scaling effects. Research has demonstrated that encoder-only models typically achieve strong performance quickly with smaller model sizes but tend to plateau, while decoder-only models require substantial scale to unlock their full potential but ultimately achieve superior generalization at large scales [16].

A comprehensive study comparing architectures at the 50-billion parameter scale found that decoder-only models with generative pretraining excelled at zero-shot generalization for creative tasks, while encoder-decoder models with masked language modeling pretraining performed best for zero-shot MLM tasks but struggled with open-ended question answering [16]. This highlights how the optimal architecture depends not only on task type but also on the available computational resources and target model size.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Comparison

Benchmarking Encoder vs. Decoder Performance

To ensure valid comparisons between architectural approaches, researchers have developed standardized evaluation methodologies:

Multilingual Machine Translation Protocol [27]:

- Models Compared: mT5 (encoder-decoder) vs. Llama 2 (decoder-only)

- Languages: Focus on Indian regional languages (Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam)

- Evaluation Metrics: BLEU scores for translation quality, computational efficiency metrics

- Key Findings: Encoder-decoder models generally outperformed in translation quality and contextual understanding, while decoder-only models demonstrated advantages in computational efficiency and fluency

STEM MCQ Evaluation Protocol [22]:

- Dataset: LLM-generated STEM Multiple-Choice Questions from Wikipedia topics

- Models: DeBERTa v3 Large (encoder), Mistral-7B (decoder), Llama 2-7B (decoder)

- Methodology: Fine-tuning with and without context, comparison against closed-source models

- Key Findings: Encoder models (DeBERTa) and smaller decoder models (Mistral-7B) outperformed larger decoder models (Llama 2-7B) on reasoning tasks when appropriate context was provided

Molecular Property Prediction Workflow

For scientific applications, specialized evaluation protocols have been developed. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for evaluating model performance on molecular property prediction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate model architecture represents a critical strategic decision in AI-driven scientific research. The following table catalogues essential "research reagents" in the AI architecture landscape, with specific guidance for scientific applications:

Table 3: Research reagent solutions for AI-driven scientific discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Scientific Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder Models | BERT, ModernBERT | Text classification, named entity recognition, relation extraction | Ideal for literature mining, patent analysis, and knowledge base construction [26] |

| Decoder Models | GPT-4, LLaMA, PaLM | Hypothesis generation, research summarization, experimental design | Suitable for generating novel research hypotheses and explaining complex scientific concepts [25] |

| Encoder-Decoder Models | T5, SMI-TED289M | Molecular property prediction, reaction outcome prediction | Optimal for quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and reaction prediction [24] |

| Specialized Scientific Models | SMI-TED289M, MoE-OSMI | Molecular representation learning, property prediction | Domain-specific models pretrained on scientific corpora often outperform general-purpose models [24] |

| Efficiency Optimization | Alternating Attention, Unpadding | Handling long sequences, reducing computational overhead | Critical for processing large molecular databases or lengthy scientific documents [26] |

The architectural dichotomy between encoder and decoder models fundamentally dictates their functional capabilities, with encoder-focused architectures excelling at comprehension tasks and decoder-focused architectures dominating generation tasks [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this distinction has practical implications:

When to prefer encoder-style architectures:

- Molecular property prediction and classification [24]

- Scientific document analysis and information extraction [26]

- High-throughput screening and content moderation [26]

- Applications requiring bidirectional context understanding [23]

When to prefer decoder-style architectures:

- Hypothesis generation and research question formulation [25]

- Scientific writing assistance and summarization [1]

- Exploratory molecular design and optimization [24]

- Tasks requiring creative reasoning and analogical thinking [16]

When encoder-decoder models are optimal:

- Molecular representation learning and reconstruction [24]

- Reaction outcome prediction [24]

- Machine translation of scientific literature [27]

- Tasks requiring both deep understanding and sequential output [1]

The emerging trend toward hybridization and architecture-aware model selection promises to further enhance AI-driven scientific discovery, with models like ModernBERT demonstrating that encoder architectures continue to evolve with significant performance improvements [26]. As the AI landscape continues to mature, researchers who strategically match architectural strengths to specific scientific tasks will gain a significant advantage in accelerating discovery and innovation.

The evolution of Large Language Models (LLMs) has been largely defined by the competition and specialization between three core architectural paradigms: encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder models. While the transformer architecture introduced both encoder and decoder components for sequence-to-sequence tasks like translation [1], recent years have witnessed a significant architectural shift. The research community has rapidly transitioned toward decoder-only modeling, dominated by models like GPT, LLaMA, and Mistral [4] [28]. However, this transition has occurred without rigorous comparative analysis from a scaling perspective, raising concerns that the potential of encoder-decoder models may have been overlooked [4] [28]. Furthermore, encoder-only models like DeBERTaV3 continue to demonstrate remarkable performance in specific tasks [29], maintaining their relevance in the modern NLP landscape. This guide provides an objective comparison of these architectural families, focusing on their performance characteristics, scaling properties, and optimal application domains for research professionals.

Architectural Fundamentals and Historical Context

Core Architectural Differences

The fundamental differences between architectural families stem from their distinct approaches to processing input sequences and generating outputs:

Encoder-Only Models (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTa): These models utilize bidirectional self-attention to process entire input sequences simultaneously, capturing rich contextual relationships between all tokens [1]. They are pre-trained using objectives like masked language modeling, where random tokens in the input are masked and the model must predict the original tokens based on their surrounding context [1]. This architecture excels at understanding tasks but does not generate text autoregressively.

Decoder-Only Models (e.g., GPT series, LLaMA, Mistral): These models employ masked self-attention with causal masking, preventing each token from attending to future positions [30] [1]. This autoregressive property enables them to generate coherent sequences token-by-token while maintaining the constraint that predictions for position i can only depend on known outputs at positions less than i [1]. Pre-trained using causal language modeling, they simply predict the next token in a sequence [28].

Encoder-Decoder Models (e.g., T5, BART): These hybrid architectures maintain separate encoder and decoder stacks [28]. The encoder processes the input with bidirectional attention, while the decoder generates outputs using causal attention with cross-attention to the encoder's representations [1]. This decomposition often improves sample and inference efficiency for sequence-to-sequence tasks [28].

Evolution of Major Model Families

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Major Model Families

| Architecture | Representative Models | Key Innovations | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | BERT, RoBERTa, DeBERTaV3 | Bidirectional attention, Masked LM, Next-sentence prediction | Text classification, Named entity recognition, Sentiment analysis |

| Decoder-Only | GPT-3/4, LLaMA 2/3, Mistral, Gemma | Causal autoregressive generation, Emergent in-context learning | Text generation, Question answering, Code generation |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5, BART, Flan-T5 | Sequence-to-sequence learning, Transfer learning across tasks | Translation, Summarization, Text simplification |

The rapid ascent of decoder-only models has been particularly notable, with architectures like LLaMA 3 (8B and 70B parameters) and Mistral's Mixture-of-Experts models dominating recent open-source developments [31]. However, concurrent research has revisited encoder-decoder architectures (RedLLM) with enhancements from modern decoder-only LLMs, demonstrating their continued competitiveness, especially after instruction tuning [4] [28].

Experimental Comparison: Performance and Scaling

Methodology for Architectural Comparison

Recent rigorous comparisons between architectural families have employed standardized experimental protocols to enable fair evaluation. The RedLLM study implemented a controlled methodology with these key components [28]:

- Training Data: All models were pretrained on RedPajama V1 for approximately 1.6 trillion tokens to ensure consistent comparison of scaling properties without data quality confounders.

- Model Scales: Comprehensive comparison across multiple model sizes ranging from ~150 million to ~8 billion parameters to analyze scaling laws.

- Architectural Alignment: RedLLM (encoder-decoder) was enhanced with recent recipes from DecLLM (decoder-only), including rotary positional embedding with continuous positions, SwiGLU FFN activation, and RMSNorm for pre-normalization.

- Training Objectives: Decoder-only models used causal language modeling, while encoder-decoder models employed prefix language modeling for pretraining.

- Evaluation Framework: Models were evaluated on both in-domain (RedPajama samples) and out-of-domain (Paloma samples) data, with zero-shot and few-shot capabilities assessed across 13 diverse downstream tasks after instruction tuning on FLAN.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Model Architectures on STEM MCQs

| Model Architecture | Specific Model | STEM MCQ Accuracy | Key Strengths | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | DeBERTa V3 Large | High (Outperforms Llama 2-7B) | Superior on understanding tasks with provided context | Efficient inference |

| Decoder-Only | Mistral-7B Instruct | High (Outperforms Llama 2-7B) | Strong few-shot capability, text generation | Moderate inference cost |

| Decoder-Only | Llama 2-7B | Lower baseline | General language understanding | Moderate inference cost |

| Encoder-Decoder | RedLLM (Post-instruction tuning) | Comparable to Decoder-Only | Strong performance after fine-tuning, efficient inference | High inference efficiency |

In a specialized evaluation on challenging LLM-generated STEM multiple-choice questions, encoder-only models like DeBERTa V3 Large demonstrated remarkable performance when provided with appropriate context through fine-tuning, even outperforming some decoder-only models like Llama 2-7B [22]. This highlights that architectural advantages are often task-dependent and context-reliant.

Scaling Properties and Efficiency Analysis

Table 3: Scaling Properties and Efficiency Comparison

| Architecture | Scaling Exponent | Compute Optimality | Inference Efficiency | Context Length Extrapolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decoder-Only (DecLLM) | Similar scaling | Dominates compute-optimal frontier | Moderate efficiency | Strong capabilities |

| Encoder-Decoder (RedLLM) | Similar scaling | Less compute-optimal | Substantially better | Promising capabilities |

The comprehensive scaling analysis reveals that while both RedLLM and DecLLM show similar scaling exponents, decoder-only models almost dominate the compute-optimal frontier during pretraining [28]. However, after instruction tuning, encoder-decoder models achieve comparable zero-shot and few-shot performance to decoder-only models across scales while enjoying significantly better inference efficiency [28]. This presents a crucial quality-efficiency trade-off for research applications.

Figure 1: Workflow of Architectural Performance Across Training Stages

Specialized Applications in Scientific Domains

Performance on Scientific and Technical Tasks

Different architectural paradigms demonstrate distinct advantages for scientific and research applications:

Encoder-Only Models maintain strong performance on classification-based scientific tasks, with DeBERTaV3 remaining a top performer among encoder-only models even when newer architectures like ModernBERT are trained on identical data [29]. This suggests their performance edge comes from architectural and training objective optimizations rather than differences in data.

Decoder-Only Models exhibit emergent capabilities in complex reasoning tasks, with specialized versions like DeepSeek-R1 demonstrating strong performance in mathematical problem-solving, logical inference, and complex reasoning through self-verification and chain-of-thought reasoning [32] [33].

Encoder-Decoder Models show particular strength in tasks requiring sustained source awareness and complex mapping between input and output sequences, such as literature summarization, protocol translation, and data transformation tasks common in scientific workflows [30] [1].

Attention Mechanisms and Information Flow

A critical differentiator between architectures lies in their attention mechanisms and information flow:

Figure 2: Information Flow in Different Transformer Architectures

Decoder-only models face challenges with "attention degeneration," where decoder-side attention focus on source tokens degrades as generation proceeds, potentially leading to hallucinated or prematurely truncated outputs [30]. This is quantified through sensitivity analysis showing that as the generation index grows, sensitivity to the source diminishes in decoder-only structures [30]. Innovative approaches like Partial Attention LLM (PALM) have been developed to maintain source sensitivity for long generations [30].

Benchmarking Datasets and Evaluation Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Model Evaluation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Architectural Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RedPajama V1 | Pretraining Corpus | Large-scale text corpus for model pretraining | Universal across architectures |

| FLAN | Instruction Dataset | Collection of instruction-following tasks | Critical for instruction tuning |

| Paloma | Evaluation Benchmark | Out-of-domain evaluation dataset | Scaling law analysis |

| STEM MCQ Dataset | Specialized Benchmark | Challenging LLM-generated science questions | Evaluating reasoning with context |

| HumanEvalX | Code Benchmark | Evaluation of code generation capabilities | Decoder-only specialization |

These research reagents form the foundation for rigorous architectural comparisons. The STEM MCQ dataset, specifically created by employing various LLMs to generate challenging questions on STEM topics curated from Wikipedia, addresses the absence of benchmark STEM datasets on MCQs created by LLMs [22]. This enables more meaningful evaluation of model capabilities on scientifically relevant tasks.

The modern landscape of large language models reveals a nuanced architectural ecosystem where encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder models each occupy distinct optimal application domains. Encoder-only models like DeBERTaV3 continue to excel in understanding tasks and maintain competitive performance through architectural refinements [29]. Decoder-only models dominate generative applications and demonstrate superior compute optimality during pretraining [28]. Encoder-decoder architectures, often overlooked in recent trends, offer compelling performance after instruction tuning with substantially better inference efficiency [4] [28].

For research professionals, the architectural choice involves careful consideration of task requirements, computational constraints, and performance priorities. While the field has witnessed a pronounced shift toward decoder-only models, evidence suggests that encoder-decoder architectures warrant renewed attention, particularly for applications requiring both comprehensive input understanding and efficient output generation. Future architectural developments will likely continue to blend insights from all three paradigms, creating increasingly specialized and efficient models for scientific applications.

Translating Architecture to Action: LLM Applications in Drug Development Pipelines

Within the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence for scientific discovery, a architectural dichotomy has emerged: encoder-only versus decoder-only transformer models. While decoder-only models have recently dominated headlines for their generative capabilities, encoder-only models maintain critical importance in scientific domains requiring deep understanding and analysis of complex data patterns, particularly in druggable target identification. Encoder-only architectures, characterized by their bidirectional processing capabilities, excel at extracting meaningful representations from input sequences by examining both left and right context of each token simultaneously [5] [1]. This architectural advantage makes them exceptionally well-suited for classification and extraction tasks where comprehensive context understanding outweighs the need for text generation.

In pharmaceutical research, the identification and classification of druggable targets represents a foundational challenge with profound implications for therapeutic development. Traditional approaches struggle with the complexity of biological systems, data heterogeneity, and the high costs associated with experimental validation [34]. Encoder-only models offer a transformative approach by leveraging large-scale biomedical data to identify patterns and relationships that elude conventional computational methods. As the field progresses, understanding the specific advantages, implementation requirements, and performance characteristics of encoder-only architectures becomes essential for researchers aiming to harness AI for accelerated drug discovery.

Architectural Advantages of Encoder-Only Models for Biomedical Data

Encoder-only models possess distinct architectural characteristics that make them particularly effective for handling the complexities of biomedical data. Unlike decoder-only models that use masked self-attention to prevent access to future tokens, encoder-only models employ bidirectional attention mechanisms that process entire input sequences simultaneously [5] [1]. This capability is crucial for biological context understanding, where the meaning of a protein sequence element or chemical compound often depends on surrounding contextual information.

The pretraining objectives commonly used for encoder-only models further enhance their suitability for biomedical classification tasks. Through masked language modeling (MLM), these models learn to predict randomly masked tokens based on their surrounding context, forcing them to develop robust representations of biological language structure [1]. For example, when processing protein sequences, this approach enables the model to learn the relationships between amino acid residues and their structural implications. Additional pretraining strategies like next sentence prediction help models understand relationships between biological entities, such as drug-target interactions or pathway components [1].

Another significant advantage lies in the computational efficiency of encoder-only architectures for classification tasks. Unlike autoregressive decoding that requires sequential token generation, encoder models can process entire sequences in parallel during inference, resulting in substantially faster throughput for extractive and discriminative tasks [35]. This efficiency becomes particularly valuable when screening large compound libraries or analyzing extensive genomic datasets where rapid iteration is essential.

Table 1: Architectural Comparison for Biomedical Applications

| Feature | Encoder-Only Models | Decoder-Only Models | Relevance to Drug Target ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Mechanism | Bidirectional | Causal (Masked) | Full context understanding for protein classification |

| Training Objective | Masked Language Modeling | Next Token Prediction | Better representation learning for sequences |

| Inference Pattern | Parallel processing | Sequential generation | Faster screening of compound libraries |

| Output Type | Class labels, embeddings | Generated sequences | Ideal for classification tasks |

| Context Utilization | Full sequence context | Left context only | Comprehensive biomolecular pattern recognition |

Implementation Framework: optSAE-HSAPSO for Target Identification

Experimental Protocol and Model Architecture

A groundbreaking demonstration of encoder-only capabilities in drug discovery comes from the optSAE-HSAPSO framework, which integrates a Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) for feature extraction with a Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) algorithm for parameter optimization [36]. This approach specifically addresses key limitations in conventional drug classification methods, including overfitting, computational inefficiency, and limited scalability to large pharmaceutical datasets.

The experimental protocol begins with comprehensive data preprocessing of drug-related information from curated sources including DrugBank and Swiss-Prot. The input features encompass molecular descriptors, structural properties, and known interaction profiles that collectively characterize each compound's potential as a drug candidate. The processed data then feeds into the Stacked Autoencoder component, which performs hierarchical feature learning through multiple encoding layers, progressively capturing higher-level abstractions of the input data [36]. This deep representation learning enables the model to identify complex, non-linear patterns that correlate with druggability.

The HSAPSO optimization phase dynamically adjusts hyperparameters throughout training, balancing exploration and exploitation to navigate the complex parameter space efficiently [36]. Unlike static optimization methods, this adaptive approach continuously refines model parameters based on performance feedback, preventing premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. The integration of swarm intelligence principles enables robust optimization without relying on gradient information, making it particularly effective for the non-convex optimization landscapes common in deep learning architectures.

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

When evaluated on standard benchmarks, the optSAE-HSAPSO framework achieved remarkable performance metrics, including a 95.52% classification accuracy in identifying druggable targets [36]. This accuracy substantially outperformed traditional machine learning approaches like support vector machines and XGBoost, which typically struggle with the high dimensionality and complex relationships within pharmaceutical data. The model also demonstrated exceptional computational efficiency, processing samples in approximately 0.010 seconds each with remarkable stability (±0.003) across iterations [36].

The robustness of the approach was further validated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and convergence analyses, which confirmed consistent performance across both validation and unseen test datasets [36]. This generalization capability is particularly valuable in drug discovery contexts where model applicability to novel compound classes is essential. The framework maintained high performance across diverse drug categories and target classes, demonstrating its versatility for real-world pharmaceutical applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Drug Classification Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Computational Time (per sample) | Stability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE-HSAPSO | 95.52% | 0.010s | ±0.003 | High accuracy, optimized feature extraction |

| XGBoost | 94.86% | Not Reported | Lower | Good performance, limited scalability |

| SVM-based | 93.78% | Not Reported | Moderate | Handles high-dimension data, slower with large datasets |

| Traditional ML | 89.98% | Not Reported | Lower | Interpretable, struggles with complex patterns |

Encoder Specialization in Biomedical Domains: BioClinical ModernBERT

Domain Adaptation and Architecture Optimization

The development of BioClinical ModernBERT represents a specialized implementation of encoder-only architectures specifically designed for biomedical natural language processing tasks [37]. This model builds upon the ModernBERT architecture but incorporates significant domain adaptations through continued pretraining on the largest biomedical and clinical corpus to date, encompassing over 53.5 billion tokens from diverse institutions, domains, and geographic regions [37]. This extensive domain adaptation addresses a critical limitation of general-purpose language models when applied to specialized scientific contexts.

A key architectural enhancement in BioClinical ModernBERT is the extension of the context window to 8,192 tokens, enabled through rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) [37]. This expanded context capacity allows the model to process entire clinical notes and research documents without fragmentation, preserving critical long-range dependencies that are essential for accurate biomedical understanding. The model also features an expanded vocabulary of 50,368 terms (compared to BERT's 30,000), specifically tuned to capture the diversity and complexity of clinical and biomedical terminology [37].

The training methodology employed a two-stage continued pretraining approach, beginning with the base ModernBERT architecture and progressively adapting it to biomedical and clinical language patterns [37]. This strategy leverages transfer learning to preserve the general linguistic capabilities developed during initial pretraining while specializing the model's knowledge toward domain-specific terminology, relationships, and conceptual frameworks.

Performance Benchmarks and Applications

In comprehensive evaluations across four downstream biomedical NLP tasks, BioClinical ModernBERT established new state-of-the-art performance levels for encoder-based architectures [37]. The model demonstrated particular strength in named entity recognition, relation extraction, and document classification tasks essential for drug target identification. By processing longer context sequences, the model achieved superior performance in identifying relationships between biological entities dispersed throughout scientific literature and clinical documentation.

The practical utility of BioClinical ModernBERT in drug discovery pipelines includes its ability to extract structured information from unstructured biomedical text, such as identifying potential drug targets from research publications or clinical trial reports [37]. The model's bidirectional encoding capabilities enable it to capture complex relationships between genetic variants, protein functions, and disease mechanisms that would be challenging to discern with unidirectional architectures. Furthermore, the model's efficiency advantages make it suitable for large-scale literature mining applications, where thousands of documents must be processed to identify promising therapeutic targets.

Table 3: BioClinical ModernBERT Model Specifications

| Parameter | Base Model | Large Model | Significance for Target ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 150M | 396M | Scalable capacity for complex tasks |

| Context Window | 8,192 tokens | 8,192 tokens | Processes full documents without fragmentation |

| Vocabulary | 50,368 terms | 50,368 terms | Comprehensive biomedical terminology |

| Training Data | 53.5B tokens | 53.5B tokens | Extensive domain adaptation |

| Positional Encoding | RoPE | RoPE | Supports long-context understanding |

Comparative Analysis: Encoder vs. Decoder Architectures in Materials Research

The debate between encoder-only and decoder-only architectures extends beyond general NLP tasks to specialized applications in materials science and drug discovery. Recent research has systematically compared these architectural paradigms from a scaling perspective, evaluating performance across model sizes ranging from ~150M to ~8B parameters [4]. These investigations reveal that while decoder-only models generally demonstrate superior compute-optimal performance during pretraining, encoder-decoder and specialized encoder-only architectures can achieve comparable scaling properties and context length extrapolation capabilities [4].

For classification-focused tasks in drug discovery, encoder-only models exhibit distinct advantages in inference efficiency. After instruction tuning, encoder-based architectures achieve comparable and sometimes superior performance on various downstream tasks while requiring substantially fewer computational resources during inference [4]. This efficiency advantage becomes increasingly significant when deploying models at scale for high-throughput screening applications.

However, the architectural choice depends heavily on the specific requirements of the research task. Decoder-only models maintain advantages in generative applications, such as designing novel molecular structures or generating hypothetical compound profiles [38]. The emergent capabilities of large decoder models, including in-context learning and chain-of-thought reasoning, provide flexible problem-solving approaches that complement the specialized strengths of encoder architectures [1]. This suggests that integrated frameworks leveraging both architectural paradigms may offer the most powerful solution for comprehensive drug discovery pipelines.

Successful implementation of encoder-only models for drug target identification requires access to specialized data resources, computational frameworks, and evaluation tools. The following table summarizes key components of the research toolkit for encoder-based drug discovery pipelines:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Encoder-Based Target Identification

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Databases | DrugBank, Swiss-Prot, ChEMBL | Provides structured drug and target information | Publicly available with registration |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ZINC | Source molecular structures and properties | Open access |

| Domain-Adapted Models | BioClinical ModernBERT, BioBERT | Pretrained encoders for biomedical text | Some publicly available, others require request |

| Optimization Frameworks | HSAPSO, LoRA | Efficient parameter tuning and adaptation | Open source implementations available |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | MedNLI, BioASQ | Standardized performance assessment | Publicly available |

| Specialized Libraries | Transformers, ChemBERTa | Implementation of model architectures | Open source |

Encoder-only models represent a powerful and efficient architectural paradigm for drug target identification and classification tasks. Their bidirectional processing capabilities, computational efficiency, and specialized domain adaptations make them particularly well-suited for the complex challenges of pharmaceutical research. The demonstrated success of frameworks like optSAE-HSAPSO in achieving high-precision classification and BioClinical ModernBERT in extracting meaningful insights from biomedical literature underscores the transformative potential of these approaches.

As the field advances, several emerging trends are likely to shape the evolution of encoder architectures for drug discovery. The development of increasingly specialized encoders pretrained on domain-specific corpora will enhance performance on specialized tasks like binding site prediction and polypharmacology profiling. The integration of multimodal capabilities will enable encoders to process diverse data types, including molecular structures, omics profiles, and scientific literature within unified architectures [34]. Additionally, the emergence of hybrid architectures that strategically combine encoder and decoder components will provide balanced solutions that leverage the strengths of both approaches.

For researchers and drug development professionals, encoder-only models offer a validated pathway for enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of target identification workflows. By leveraging these architectures within comprehensive drug discovery pipelines, the pharmaceutical industry can accelerate the translation of biological insights into therapeutic interventions, ultimately reducing development timelines and improving success rates. The continued refinement of encoder architectures and their integration with experimental validation frameworks will further solidify their role as indispensable tools in modern drug discovery.

Leveraging Encoders for High-Throughput Data Extraction and Entity Recognition

Within materials science and drug development, the ability to automatically and accurately extract specific entities from vast volumes of unstructured text—such as research papers, lab reports, and clinical documents—is paramount for accelerating discovery. This task of Named Entity Recognition (NER) has become a key benchmark for natural language processing (NLP) models. The current landscape is dominated by two transformer-based architectural paradigms: the encoder-only models, exemplified by BERT and its variants, and the decoder-only models, which include large language models (LLMs) like GPT. While decoder-only models have captured significant attention for their generative capabilities, a growing body of evidence indicates that encoder-only architectures offer superior performance and efficiency for structured information extraction tasks. This guide provides a objective comparison of these architectures, underpinned by recent experimental data, to inform researchers selecting the optimal tools for high-throughput data extraction.

Fundamentally, both encoder and decoder architectures are built on the transformer's self-attention mechanism, but they are designed for different primary objectives [1].