Electron Microscopy in Materials Characterization: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electron microscopy (EM) techniques for materials characterization, with a special focus on applications in pharmaceutical sciences and drug development.

Electron Microscopy in Materials Characterization: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electron microscopy (EM) techniques for materials characterization, with a special focus on applications in pharmaceutical sciences and drug development. It covers foundational EM principles, including Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), and explores advanced methodologies like cryo-TEM and 4D-STEM for analyzing radiation-sensitive materials. The content addresses critical challenges such as sample preparation artifacts and beam damage, offering optimization strategies and validation frameworks. By integrating recent advancements in AI, machine learning, and detector technology, this guide serves as an essential resource for researchers and scientists aiming to leverage EM for structural and chemical analysis at the nanoscale.

The Electron Microscopy Revolution: From Basic Principles to Nanoscale Imaging

Core Principles of Electron-Sample Interaction for Material Contrast

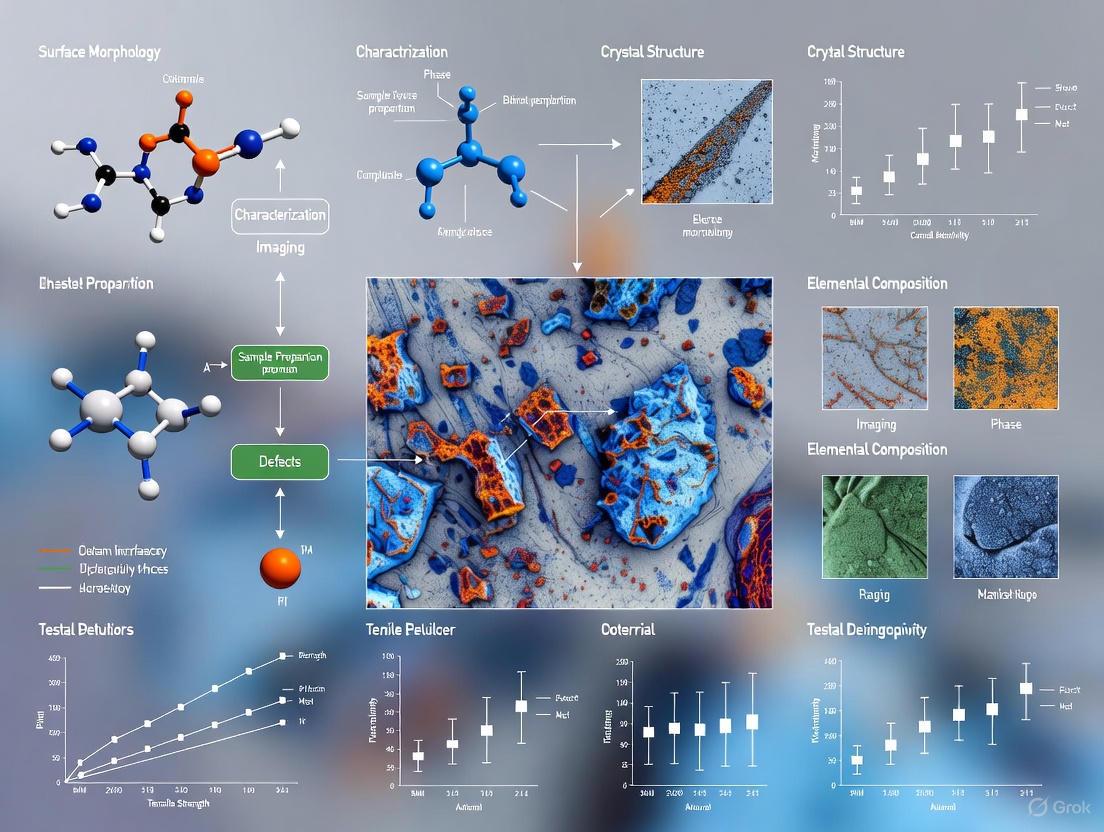

In materials characterization, the contrast in an electron micrograph is not merely an image; it is a direct visualization of electron-sample interactions. These interactions, which depend on the sample's elemental composition, density, and topography, generate detectable signals that form the basis of image contrast in both Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). This application note details the core principles behind these interactions and provides standardized protocols for leveraging them in materials science and drug development research.

Core Interaction Principles and Data Presentation

The fundamental signals generated by electron-sample interactions provide distinct information, which is summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Primary Electron-Sample Interactions and Their Role in Generating Material Contrast

| Interaction Signal | Detection Microscopy | Origin of Signal | Information Conveyed for Material Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backscattered Electrons (BSE) | SEM | Reflection of high-energy primary electrons after elastic scattering with sample atom nuclei [1]. | Atomic number contrast (Z-contrast); brighter areas correspond to heavier elements [1]. |

| Secondary Electrons (SE) | SEM | Ejection of low-energy electrons from the sample due to inelastic scattering with primary electrons [1]. | Topographical contrast; excellent for visualizing surface texture and morphology [2] [1]. |

| Transmitted Electrons (TE) | TEM | High-energy electrons that pass through a thin sample [3] [1]. | Mass-density and crystallographic contrast; denser or thicker regions appear darker [3]. |

| Elastically Scattered Electrons | TEM | Electrons that pass through the sample without energy loss but are deflected by atomic nuclei. | Used for diffraction contrast imaging, revealing grain boundaries, dislocations, and crystal structures. |

| Inelastically Scattered Electrons | TEM | Electrons that lose energy upon interacting with sample electrons. | Enables analytical techniques like Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) for elemental analysis [4]. |

| X-rays | SEM/TEM | Emission of characteristic X-rays after inner-shell ionization of sample atoms by the electron beam [4]. | Provides quantitative elemental composition and distribution via Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS/EDX) [4]. |

The workflow for selecting the appropriate technique based on these signals is outlined in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocols for Material Contrast

The following protocols are generalized for metallic and ceramic nanomaterials, common in advanced material research.

Protocol: Z-Contrast Imaging of a Composite Material Using SEM-BSE

Objective: To distinguish between different phases in a metal-ceramic composite based on atomic number contrast.

Materials:

- Composite material sample (e.g., Al-SiC).

- Standard SEM specimen mounts.

- Sputter coater.

Methodology:

- Sample Sectioning: If bulk, section the material to a size suitable for the SEM stub (typically < 10 mm in diameter).

- Mounting: Secure the sample onto an SEM stub using conductive carbon tape to prevent charging.

- Coating: Sputter-coat the sample with a thin layer (~5-10 nm) of a heavy metal like gold or platinum to enhance conductivity and secondary electron emission. For pure Z-contrast analysis with BSE, a carbon coat is preferable as it minimizes the masking of the sample's inherent elemental signal.

- Microscope Setup:

- Insert the sample into the SEM chamber and establish high vacuum.

- Set the accelerating voltage to 15-20 kV as a starting point.

- Switch to the BSE detector.

- Adjust the working distance to optimize signal and resolution (often ~10 mm).

- Image Acquisition:

- Scan the area of interest. The heavier element (e.g., SiC) will appear brighter than the lighter matrix (e.g., Al).

- Adjust contrast and brightness to maximize the differentiation between phases.

Protocol: Internal Structure Analysis of Nanoparticles Using TEM

Objective: To resolve the internal crystal structure, defects, and size distribution of synthesized nanoparticles.

Materials:

- Nanoparticle dispersion.

- TEM grids (e.g., Copper, Nickel, or Gold grids with a carbon film support) [3].

- Plasma cleaner (optional, but improves sample adherence).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute the nanoparticle solution in a volatile solvent (e.g., ethanol) to a suitable concentration to prevent aggregation.

- Pipette a small volume (3-5 µL) of the dispersion onto the carbon-coated side of the TEM grid.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate fully under ambient conditions or use a gentle blotting technique.

- Microscope Setup:

- Load the grid into the TEM holder.

- Insert the holder into the microscope and establish high vacuum.

- Start observation at a low magnification (e.g., 5,000X) to locate a suitable area.

- Image Acquisition:

- Switch to higher magnification to resolve individual nanoparticles.

- For crystalline materials, engage the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) mode to obtain diffraction patterns for phase identification [1].

- Acquire images at multiple locations to ensure a representative analysis of the sample.

Protocol: Multi-Elemental Mapping of a Biological-Inorganic Interface Using TEM-EDX

Objective: To visualize the spatial distribution of specific elements at the interface between a biomaterial and tissue, relevant to drug delivery system analysis.

Materials:

- Thin-sectioned (50-100 nm) sample of the hybrid material embedded in a resin [3] [4].

- Lanthanide-based stains (e.g., for specific targeting) [3].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Microscope Setup:

- Use a TEM equipped with an EDX detector.

- Set the accelerating voltage to 80-200 kV to ensure sufficient overvoltage for exciting the characteristic X-rays of the elements of interest.

- Data Acquisition:

- Locate the region of interest in TEM mode.

- Initiate an EDX area scan or mapping routine.

- The microscope will raster the beam across the area, collecting the full X-ray spectrum at each pixel.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the accompanying software to generate elemental maps by selecting the characteristic X-ray peaks for each element (e.g., Os M-line, N K-line, P K-line, S K-line) [4].

- Overlay these elemental maps onto the structural TEM image to correlate composition with morphology. Each element can be assigned a false color for clear visualization [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Key materials and their functions for electron microscopy sample preparation and analysis are listed below.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Electron Microscopy Sample Preparation

| Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Osmium Tetroxide (OsO₄) | A heavy metal stain used primarily in biological TEM to fix and contrast lipids and membranes by binding to unsaturated bonds [3]. |

| Lanthanide Salts | A group of rare-earth metals (e.g., lanthanum, cerium) used as stains in color TEM techniques. Each lanthanide has a unique X-ray signature, allowing them to be distinguished and false-colored in EDX analysis [3] [4]. |

| Conductive Metal Coatings | Thin layers of gold, platinum, or carbon sputtered onto non-conductive samples in SEM to prevent surface charging and to enhance secondary electron emission [1]. |

| TEM Grids | Small metal (Cu, Ni, Au) meshes that support the thin sample. They are non-reactive to avoid interfering with the electron beam [3]. |

| Resin Embedding Kits | (e.g., Epon, Araldite) Used to infiltrate and encapsulate biological or soft materials, allowing them to be sectioned into ultra-thin slices (50-100 nm) for TEM analysis [4]. |

| Immunogold Labels | Colloidal gold nanoparticles conjugated to antibodies. Used in immunolabeling to precisely localize specific proteins or antigens within a cellular structure under TEM [4]. |

Electron microscopy has become an indispensable tool in materials characterization, providing researchers with unparalleled capabilities to visualize and analyze material structures far beyond the limits of optical microscopy. Within the field of electron microscopy, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) represent two fundamental approaches with distinct capabilities and applications. SEM primarily provides topographical and compositional information from sample surfaces, while TEM offers insights into the internal structure, crystallography, and atomic details of materials. Understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of each technique is essential for researchers seeking to characterize materials effectively for applications ranging from drug development to nanotechnology. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of SEM and TEM methodologies, including detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate technique for their specific characterization needs.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Operating Principles

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) operates by scanning a focused beam of electrons across the surface of a sample in a raster pattern [5] [6]. When these high-energy electrons interact with atoms in the sample, they generate various signals including secondary electrons (SEs), backscattered electrons (BSEs), and characteristic X-rays [7]. Secondary electrons are low-energy electrons emitted from atoms near the surface and provide fine detail about surface topography due to their shallow escape depth (typically <10 nm) [7]. Backscattered electrons are higher-energy electrons elastically scattered by atomic nuclei, with intensity dependent on atomic number, making them useful for compositional contrast [7] [6]. These detected signals are converted into high-resolution images displaying surface characteristics.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) functions by transmitting a beam of electrons through an ultrathin sample (typically less than 100 nm thick) [5] [8]. As electrons pass through the specimen, they interact with its atoms, resulting in scattering, absorption, and diffraction [5]. The transmitted electrons carry information about the sample's internal structure, which is magnified and focused onto an imaging device such as a fluorescent screen or digital detector [8]. TEM imaging contrast arises from position-to-position differences in thickness, density, atomic number, crystal structure, or orientation, enabling atomic-resolution information about the internal structure of materials [8].

Technical Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of SEM and TEM Technical Specifications

| Parameter | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Surface topography and composition [5] | Internal structure and crystallography [5] |

| Resolution | 1-10 nanometers [5] | 0.1 nanometers or better [5] |

| Magnification | Up to 2,000,000× [7] [9] | Up to 50,000,000× [9] |

| Image Dimension | 3-D appearance [6] | 2-D projection [9] |

| Sample Thickness | Thick or bulk samples acceptable [9] | Ultrathin samples only (<100-150 nm) [5] [9] |

| Primary Signals | Secondary electrons, backscattered electrons, X-rays [7] | Transmitted electrons, diffracted electrons [8] |

| Key Applications | Surface morphology, fracture analysis, elemental mapping [7] [10] | Crystal defects, atomic structure, nanoparticle internal architecture [8] [11] |

Experimental Protocols

SEM Sample Preparation and Imaging Protocol

Objective: To prepare a conductive or non-conductive sample for surface analysis using Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Table 2: Essential Materials for SEM Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Conductive Adhesive | Rigidly mounts specimen to holder/stub [6] |

| Sputter Coater | Applies thin conductive layer to non-conductive samples [6] |

| Gold, Platinum, or Carbon Coating | Conductive materials for coating to prevent charging [6] |

| Chemical Fixatives (Glutaraldehyde, Formaldehyde) | Preserves and stabilizes biological structure [6] |

| Ethanol or Acetone Series | Dehydrates biological specimens [6] |

| Critical Point Dryer | Removes solvents without structural collapse [6] |

Procedure:

Sample Size Reduction: If necessary, reduce sample to appropriate size for SEM stage (typically up to several centimeters) [6].

Cleaning: Gently clean sample surface to remove debris or contaminants that may obscure features or outgas in vacuum [12].

Mounting: Affix sample to specimen stub using conductive adhesive (e.g., carbon tape, silver paste, or epoxy) to ensure electrical grounding [6].

Conductive Coating (for non-conductive samples):

- Place sample in sputter coater chamber

- Evacuate chamber to appropriate vacuum level

- Apply thin conductive coating (5-20 nm) of gold, gold/palladium, platinum, or carbon [6]

- Alternatively, use carbon tape to create conductive path for bulky samples

Alternative Preparation for Hydrated Samples:

Microscope Loading:

- Secure specimen stub into microscope stage

- Evacuate chamber to high vacuum (typically 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁵ Pa) [6]

Imaging Parameters Optimization:

Data Collection:

TEM Sample Preparation and Imaging Protocol

Objective: To prepare an electron-transparent thin sample for internal structure analysis using Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Table 3: Essential Materials for TEM Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Ultramicrotome | Cuts ultrathin sections (50-100 nm) of embedded samples [13] |

| Diamond or Glass Knives | Creates clean sections for ultramicrotomy [13] |

| Focus Ion Beam (FIB) | Site-specific thinning of materials samples [13] |

| Formvar/Carbon-Coated Grids | Supports ultrathin sections during imaging [8] |

| Embedding Resins | Infiltrates and supports biological and soft materials [6] |

| Heavy Metal Stains (Uranyl Acetate, Osmium Tetroxide) | Enhances contrast in biological specimens [6] [13] |

Procedure:

Sample Preparation Routes:

Route A (Biological Samples):

- Fix with primary fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde in buffer) for 2-4 hours

- Post-fix with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour

- Dehydrate through graded ethanol series (30%-100%)

- Infiltrate with resin (e.g., epoxy, Spurr's) progressively pure resin

- Embed in fresh resin and polymerize at appropriate temperature [6]

Route B (Materials Samples):

Sectioning:

- Trim resin block to create small pyramid facing knife

- Cut ultrathin sections (50-100 nm) using ultramicrotome with diamond knife

- Float sections on water surface in boat of diamond knife

- Collect sections on formvar/carbon-coated grids [13]

Staining (for Biological Samples):

Microscope Loading:

- Secure grid in appropriate holder

- Insert holder into microscope column

- Evacuate column to high vacuum (typically below 10⁻⁵ Pa) [13]

Imaging Parameters Optimization:

Data Collection:

Visualization of Technique Selection Workflows

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting between SEM and TEM techniques based on characterization needs and sample properties.

Figure 2: Signal generation and information content in SEM versus TEM techniques.

Applications in Materials Characterization

SEM Applications

SEM finds extensive application across diverse fields of materials characterization:

Nanomaterials Morphology: Determination of nanoparticle size, shape, and distribution. For metallic nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Pt) and oxide particles (TiO₂, ZnO), SEM confirms uniformity and degree of agglomeration [7]. Digital image analysis software generates particle size distributions from SEM micrographs, providing statistically meaningful measurements [7].

Surface Topography: Analysis of surface features including porosity, roughness, and texture. High-resolution SEM has resolved terraces as small as 1.2 nm on zeolite crystals, demonstrating capability to probe superfine surface structures [7].

Failure Analysis: Identification of fracture origins, corrosion sites, and manufacturing defects in materials [10]. SEM's large depth of field provides three-dimensional visualization of complex surfaces, particularly valuable for examining rough or hierarchical nanostructures [7].

Elemental Analysis: When equipped with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), SEM enables elemental identification and mapping across heterogeneous materials [7] [10]. Backscattered electron imaging provides strong contrast between regions of different atomic number, enabling visualization of multiphase composites, core-shell nanostructures, and embedded inclusions [7].

TEM Applications

TEM provides critical insights into internal material structures:

Crystal Defect Analysis: Identification and characterization of dislocations, stacking faults, and grain boundaries in crystalline materials [11]. TEM images of nanostructured alloys reveal highly pile-up dislocations, with corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns showing streak effects on spots [11].

Atomic Resolution Imaging: Visualization of atomic arrangements in materials, with modern TEMs achieving resolutions under 60 pm, capable of capturing atomic-scale details [13]. This enables direct observation of lattice fringes, interface structures, and defect configurations.

Nanoparticle Characterization: Detailed analysis of internal structure, size, shape, and crystallography of nanomaterials [11]. TEM reveals core-shell structures, with differences in contrast distinguishing core and shell materials in nanoparticles [11].

Biological Ultrastructure: Visualization of cellular organelles, viral structures, and macromolecular complexes [13]. Cryo-TEM techniques preserve biological samples in their native hydrated state, enabling structural biology studies without chemical fixation artifacts.

Advanced Applications and Correlative Approaches

Specialized Techniques

Environmental SEM (ESEM) represents a modified version of SEM that enables imaging of samples in their natural hydrated state or under low vacuum conditions [14]. This is particularly valuable for biological specimens that cannot withstand conventional electron microscopy preparation methods [14]. ESEM operates by maintaining a higher pressure chamber around the specimen (typically above 500 Pa) while differentially pumping the electron optical column to maintain high vacuum at the electron gun [6]. The gas environment around the sample in ESEM neutralizes charge and provides amplification of the secondary electron signal, eliminating the need for conductive coating of non-conductive samples [6].

Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) combines aspects of both SEM and TEM, utilizing a focused electron beam that is scanned across the sample in a raster pattern while detecting transmitted electrons [14] [13]. This technique offers the same high resolution as conventional TEM, with the difference being that beam focusing occurs before the beam strikes the specimen in STEM, whereas focusing occurs after transmission in TEM [14]. STEM is particularly valuable for Z-contrast imaging using high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detection, where contrast is approximately proportional to the square of the atomic number, enabling compositional mapping at atomic resolution [13].

Correlative Microscopy

Increasingly, researchers are employing correlative approaches that combine multiple microscopy techniques to gain comprehensive understanding of material systems. SEM and TEM can be effectively combined with other characterization methods:

SEM-FIB Integration: Focused Ion Beam (FIB) systems integrated with SEM enable site-specific sample preparation for TEM analysis, as well as 3D tomography through sequential milling and imaging [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for cross-sectional analysis of specific features in semiconductor devices and engineered materials.

SEM-EBSD Analysis: Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) in SEM provides crystallographic information including grain orientation, phase identification, and strain analysis [12]. When correlated with TEM-based crystallographic analysis, this provides multi-scale understanding of microstructure-property relationships.

Analytical TEM: Modern TEM systems incorporate multiple analytical capabilities including Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) [13]. EELS is particularly effective for analyzing light elements and understanding complex bonding states, while EDS provides elemental mapping capabilities for both light and heavy elements [13].

SEM and TEM represent complementary rather than competing techniques in the materials characterization toolkit. SEM excels in providing topographical and compositional information from sample surfaces with minimal preparation requirements, while TEM offers unparalleled resolution for investigating internal structures and crystallographic details at atomic scales. The choice between these techniques depends fundamentally on the specific research question, nature of the information required, sample properties, and available resources. Recent advances in both technologies, including environmental capabilities for SEM and aberration correction for TEM, continue to expand their applications across materials science, biological research, and nanotechnology. By understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of each technique, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools to advance their characterization objectives.

In electron microscopy research, comprehensive material characterization necessitates probing multiple physical properties simultaneously. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS), and Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) represent three cornerstone analytical techniques that, when integrated, provide a multifaceted understanding of a material's chemical, structural, and crystallographic nature. Individually, each technique offers unique insights; together, they enable researchers to establish critical links between a material's processing history, its microstructure, and its resulting properties [15] [16]. This application note details the essential protocols and synergistic applications of these techniques, framed within the context of advanced materials characterization for drug development and materials science.

EDS, EELS, and EBSD provide complementary data streams. EDS and EELS are both elemental analysis techniques used to determine chemical composition, distribution, and concentration, while EBSD exclusively probes crystallographic structure, orientation, and phase [17] [18]. The optimal technique or combination thereof depends on the specific research question, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of EDS, EELS, and EBSD techniques.

| Feature | EDS (Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy) | EELS (Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy) | EBSD (Electron Backscatter Diffraction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental composition & distribution [19] | Elemental composition, chemical bonding, & electronic structure [17] | Crystallographic orientation, phase, & strain [18] |

| Typical Instrument | SEM, TEM [17] | TEM [17] | SEM [18] |

| Spatial Resolution | 100s nm - 5 µm (SEM) [15] | Nanometer-level to atomic-level [17] | 10s - 100s nm [15] |

| Key Applications | Qualitative & quantitative elemental mapping, phase identification [15] [19] | High-resolution mapping, light element analysis, valence state determination [17] | Grain size, texture analysis, deformation mapping, grain boundary characterization [20] [18] |

| Sample Requirements | Bulk or thin samples, conductive or coated | Electron-transparent thin samples (for TEM) [17] | Tilted (~70°), polished crystalline surface [18] |

The integration of these techniques is particularly powerful. For instance, EDS and EBSD are "perfect partners" in the SEM, as their spatial resolutions are broadly similar and optimal analytical conditions (e.g., beam currents of 1-20 nA) overlap significantly [15]. This enables simultaneous data acquisition, correlating chemical and crystallographic information from the exact same sample area.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Simultaneous EDS and EBSD Analysis in the SEM

The combination of EDS and EBSD is a powerful workflow for holistic microstructural characterization [15] [16]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for integrated analysis:

- Sample Preparation: The sample must be prepared to a high-quality, polished finish free of surface deformation or contamination. For non-conductive samples, the application of a thin conductive coating (e.g., carbon) is essential to prevent charging and ensure high-quality EBSD patterns and EDS signals [18].

- Microscope and Detector Configuration: Mount the sample on a stage capable of high tilt (~70°). The ideal detector geometry involves mounting the EDS detector above the EBSD detector on the same side of the SEM chamber to enable simultaneous data collection [15].

- Optimal SEM Parameters: Set the accelerating voltage typically between 10-30 keV and the beam current between 1-20 nA. These parameters provide a sufficient X-ray count rate for EDS and generate high-quality Kikuchi patterns for EBSD [15].

- Simultaneous Data Acquisition: Define the region of interest and mapping parameters (step size, dwell time). Collect EDS spectra and EBSD patterns concurrently at each pixel. Modern large-area EDS detectors can collect hundreds of thousands of counts per second, providing high-quality elemental maps even at fast EBSD acquisition rates [15].

- Data Processing and Correlation: Process the datasets using integrated software. EBSD data provides phase maps, grain orientation maps, and texture information. EDS data yields elemental maps and quantitative composition. The software can use chemical information to assist in differentiating between crystallographically similar phases during EBSD indexing [15].

Protocol for EELS Analysis in the TEM

EELS is a high-resolution technique typically performed in a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) and is often compared with EDS for elemental analysis [17].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare an electron-transparent thin sample (typically < 100 nm thick) using techniques such as electropolishing, ion milling, or focused ion beam (FIB) milling.

- TEM and Spectrometer Alignment: Align the TEM for STEM (Scanning TEM) mode. The electron beam is focused to a fine probe and rastered across the sample. The EELS spectrometer must be calibrated for energy resolution.

- Data Acquisition: At each probe position, the transmitted electrons are collected by the spectrometer. The energy loss of these electrons is measured, generating a spectrum that contains edges corresponding to core-electron excitations, which are characteristic of each element [17]. The technique can achieve nanometer or even atomic-level spatial resolution [17].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the acquired spectra to extract quantitative elemental concentrations, map elemental distributions, and examine fine structure near ionization edges to determine chemical bonding and valence states.

Advanced Integrated Workflow

For the most comprehensive characterization, a correlative workflow can be employed. A single sample can be first analyzed in the SEM for large-area EDS and EBSD mapping to identify regions of interest. A site-specific cross-section can then be prepared via FIB and transferred to a TEM for high-resolution EELS and EDS analysis, providing atomic-scale chemical and structural information from the same feature.

Diagram 1: Integrated EDS and EBSD workflow for correlated analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful characterization relies on appropriate materials and tools. The following table lists key solutions and their functions for experiments involving EDS, EELS, and EBSD.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for EDS, EELS, and EBSD analysis.

| Category/Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | |

| Conductive Coatings (Carbon, Gold) | Applied to non-conductive samples to prevent electrostatic charging, which distorts imaging and analysis [18] [19]. |

| Polishing Suspensions (Alumina, Silica) | Used in final polishing steps to create a damage-free, smooth surface essential for high-quality EBSD patterns [18]. |

| Software & Data Analysis | |

| EBSD Indexing Software | Automates the matching of Kikuchi patterns to crystallographic databases for orientation and phase determination [18]. |

| Multivariate Statistical Analysis (e.g., PCA, k-means) | Used for mining large, multi-dimensional datasets (e.g., 4D-STEM ptychography) to distill salient features and separate statistically significant variations from noise [21]. |

| Python Libraries (e.g., kikuchipy, PyEBSD) | Open-source toolkits for processing, simulating, and indexing EBSD patterns, enabling customizable data analysis workflows [22] [23]. |

| Reference Materials | |

| Crystallographic Information Files (CIF) | Database files containing crystal structure parameters essential for phase identification and EBSD pattern indexing [15]. |

Data Management and Big Data Challenges

Contemporary electron microscopy, especially techniques like 4D-STEM ptychography which generates a full diffraction pattern at every scan position, is undergoing a "big-data revolution" [21] [24]. These datasets are characterized by high volume, velocity, and variety, posing significant challenges in data transfer, storage, and computation [24].

Effective management of these large data volumes (often terabytes per session) requires dedicated infrastructure and adherence to the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to ensure long-term data utility and reproducibility [24]. This involves implementing robust metadata standards, optimized computational workflows, and sustainable data lifecycle management plans.

The integrated application of EDS, EELS, and EBSD provides an unparalleled toolkit for deconstructing the complex relationships between a material's structure, chemistry, and performance. By leveraging their complementary strengths—through simultaneous EDS/EBSD acquisition in the SEM or high-resolution EELS/EDS in the TEM—researchers can build a comprehensive multiscale model of their material. As these techniques continue to evolve alongside advances in data analytics and automation, their combined power will be critical for driving innovation in materials science and drug development.

In the field of materials characterization, particularly in electron microscopy research, the ability to distinguish fine details is paramount. Resolving power, or resolution, is defined as the smallest distance between two separate points of an object that can still be distinguished as distinct entities when viewed through an optical instrument [25]. This fundamental concept differentiates true observational capability from mere magnification, which simply enlarges an image without necessarily revealing additional detail [26]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding resolution limits is crucial for interpreting data accurately and pushing the boundaries of what can be observed at the nanoscale.

The diffraction limit fundamentally constrains all imaging systems. When observing a point object through a circular aperture like a lens, the image formed is not a point but a diffraction pattern (the Airy pattern). The smallest detail that can be resolved is therefore limited by this diffraction effect [27]. In practical terms, resolution determines whether scientists can distinguish between two adjacent atoms, separate structural features in a pharmaceutical compound, or identify defects in a novel material.

Theoretical Foundations of Resolution Limits

The Abbe Diffraction Limit

The theoretical foundation for resolution in microscopy was established by Ernst Abbe, who related resolving power to the wavelength of the illumination source and the numerical aperture of the optical system. The Abbe criterion for the smallest resolvable distance (d) in a microscope is given by:

Δd = λ / (2n sinθ) [27]

Where:

- λ is the wavelength of the illumination source

- n is the refractive index of the imaging medium

- θ is the half-angle of the lens

The resolving power is mathematically defined as the inverse of this smallest resolvable distance:

Resolving Power = 1/Δd = (2n sinθ)/λ [27]

From this relationship, it's clear that resolution can be improved in two primary ways: decreasing the wavelength (λ) of the illumination source or increasing the numerical aperture (n sinθ) of the lens system [25].

Rayleigh's Criterion

For telescopic and microscopic systems, Rayleigh's criterion provides a practical standard for the minimum angular separation at which two point sources can be distinguished. According to this criterion, two points are considered resolvable when the central maximum of the diffraction pattern of one image coincides with the first minimum of the diffraction pattern of the other [27].

For a circular aperture, the angular separation (θ) is given by:

θ = 1.22(λ/D)

Where:

- λ is the wavelength of light

- D is the diameter of the aperture [27]

The inverse of this angular separation defines the resolving power of the instrument.

Resolution in Electron Microscopy

The Electron Wavelength Advantage

Electron microscopy overcame the fundamental limitation of light microscopy by utilizing electrons instead of photons as the illumination source. Since electrons have a much shorter wavelength than visible light, they offer significantly better resolving power [26].

The wavelength of electrons (λ) is determined by the accelerating voltage (V) in the electron microscope, approximated by:

λ = h / √(2meV)

Where:

- h is Planck's constant

- m is the mass of the electron

- e is the charge of the electron [28]

For a typical transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 100 keV, the electron wavelength is approximately 0.0037 nm, theoretically enabling atomic-scale resolution [28].

Practical Resolution Limits in Electron Microscopy

Despite the extremely short electron wavelengths, practical resolution limits in electron microscopy are constrained by multiple factors beyond theoretical calculations:

Table 1: Resolution Limits Across Microscope Types

| Microscope Type | Theoretical Resolution Limit | Practical Resolution | Key Limiting Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Microscope | ~200 nm | 200-300 nm | Wavelength of visible light (400-700 nm) [25] |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | 0.1 nm for 100 keV | ~0.2 nm for 100 keV | Lens aberrations, stability, sample preparation [28] |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | ~1 nm | 1-10 nm | Beam-sample interactions, signal-to-noise ratio [29] |

| Ultra-high Resolution SEM | < 1 nm | 0.5-1 nm | Electron source coherence, vibration control [29] |

The theoretical resolution of electron microscopes is mainly limited by the quality of electron optics, with spherical aberration correctors significantly improving the practical resolution limit [28]. For biological specimens in particular, resolution is typically worse than the theoretical limit by an order of magnitude due to additional factors including low contrast, radiation damage, and the quality of recording devices [28].

Quantitative Measures of Resolution

Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC)

In molecular electron microscopy, resolution assessment differs from traditional optical definitions due to the computational nature of structure determination. The Fourier Shell Correlation (FRC) measures the self-consistency of a reconstructed 3D structure by comparing different subsets of the data [28]. The FSC is calculated as the correlation coefficient between two independent 3D reconstructions on a shell-by-shell basis in Fourier space:

FSC(r) = [ΣF₁(r)·F₂*(r)] / [√(Σ|F₁(r)|² · Σ|F₂(r)|²)]

Where:

- F₁(r) and F₂(r) are Fourier transforms of two independent reconstructions

- The summation is over all Fourier components in a resolution shell [28]

The spatial frequency at which the FSC curve drops below a threshold value (commonly 0.143) is taken as the resolution of the reconstruction [28].

Experimental Protocols for Resolution Measurement

Protocol: Measuring Resolution via Fourier Shell Correlation in Single Particle Analysis

Data Splitting: Randomly divide the particle images into two independent sets of equal size.

Independent Reconstruction: Process each dataset separately through the entire reconstruction pipeline, including alignment, classification, and 3D reconstruction.

Fourier Transformation: Compute the 3D Fourier transforms of both final reconstructions.

Shell Correlation: Calculate the correlation coefficient between the two Fourier transforms within spherical shells of increasing spatial frequency.

Threshold Application: Determine the spatial frequency at which the FSC curve falls below the 0.143 threshold. Convert this spatial frequency to resolution in Ångströms.

Validation: Verify that the two independent reconstructions show similar structural features at the reported resolution.

This protocol leverages the principle that the resolution in EM is understood as a measure of self-consistency and reproducibility of the results, rather than the traditional concept of optical resolution [28].

Factors Limiting Practical Resolution

Instrumental Limitations

Even with advanced aberration correction, several instrumental factors constrain the practical resolution achievable in electron microscopy:

Lens Aberrations: Spherical and chromatic aberrations in electron lenses distort the electron wavefront, blurring the final image. While spherical aberration correctors have significantly improved resolution, they cannot eliminate all aberrations [28].

Source Coherence: The degree of coherence in the electron source affects interference patterns in high-resolution imaging. Field emission guns provide higher coherence than thermal emission sources, enabling better resolution [29].

Mechanical Stability: Vibrations from the environment or the instrument itself can cause image drift, limiting exposure times and resolution. Advanced vibration isolation systems are essential for ultra-high resolution SEMs [29].

Electromagnetic Interference: Stray electromagnetic fields can deflect the electron beam, distorting images. Proper shielding and stable power supplies are necessary for optimal performance [29].

Sample-Dependent Limitations

The specimen itself introduces several resolution-limiting factors:

Radiation Damage: Electron bombardment can damage or alter the sample, particularly biological specimens. The accepted dose for cryo-EM is typically limited to ~25 e⁻/Ų to minimize damage while maintaining sufficient signal [28].

Contrast Limitations: Biological materials consist mainly of light elements (C, N, O) with similar electron densities, resulting in inherently low contrast. Phase contrast techniques help but introduce their own resolution limits through the contrast transfer function [28].

Sample Thickness: Multiple scattering events in thick samples reduce resolution due to the "delocalization" of information. For atomic resolution TEM, samples must typically be <50 nm thick [30].

Preparation Artifacts: Dehydration, staining, and sectioning can introduce artifacts that limit the observable detail in biological samples [26].

Advanced Techniques Pushing Resolution Boundaries

Volume Electron Microscopy (vEM)

Volume Electron Microscopy (vEM) represents a suite of techniques developed to image cells, tissues, and small model organisms in three dimensions at nano- to micrometer resolutions [31]. These techniques include:

Serial Block-Face SEM (SBF-SEM): An ultramicrotome within the SEM chamber sequentially removes thin sections from the block face, which is imaged after each cut.

Focused Ion Beam SEM (FIB-SEM): A focused ion beam mills away thin layers of material, with the newly exposed surface imaged by the electron beam.

Array Tomography: Consecutive serial sections are collected and imaged individually, then computationally reconstructed into a 3D volume.

vEM techniques face unique resolution challenges, particularly in maintaining registration across large volumes and balancing the trade-off between field of view, resolution, and acquisition speed [31].

Aberration-Corrected Electron Microscopy

The development of aberration correctors has dramatically improved the practical resolution of electron microscopes. These systems use multipole lenses to compensate for the inherent spherical and chromatic aberrations of conventional electron lenses. The implementation of aberration correction has enabled:

- Sub-Ångström resolution in TEM, allowing direct imaging of atomic columns in materials [30]

- Improved signal-to-noise ratio at high resolution

- More precise quantitative analysis of atomic structures

Modern aberration-corrected TEMs can achieve resolutions of 50 pm, enabling not just atomic resolution but detailed analysis of bond lengths and atomic positions [30].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Resolution EM

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for High-Resolution Electron Microscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-Preparation Systems | Vitrification of aqueous samples | Preserves native hydration state; prevents ice crystal damage [28] |

| Heavy Metal Stains (e.g., Uranyl Acetate) | Electron density contrast enhancement | Improves visibility of biological structures; requires careful handling due to toxicity |

| Low-Vacuum Evaporators | Conductive coating of non-conductive samples | Prevents charging in SEM; critical for high-resolution imaging of insulating materials |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) Systems | Site-specific sample preparation | Enables cross-sectioning and TEM lamella preparation from specific regions of interest [31] |

| Aberration Correctors | Compensation of lens imperfections | Essential for sub-Ångström resolution TEM; requires specialized alignment protocols [30] |

| Direct Electron Detectors | High-efficiency electron detection | Superior to CCDs for high-resolution TEM; enables single-particle analysis at near-atomic resolution [28] |

| Ultra-Microtomes | Thin sectioning of embedded samples | Produces uniform thin sections (50-200 nm) for TEM; critical for artifact-free preparation |

| Plasma Cleaners | Sample surface purification | Removes hydrocarbon contamination that degrades resolution in high-resolution SEM and TEM |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Factors Determining Microscope Resolution

FSC Resolution Measurement Protocol

Understanding and optimizing resolving power remains fundamental to advancing materials characterization research using electron microscopy. While theoretical limits are established by fundamental physics—primarily the wavelength of the illumination source—practical resolution is determined by a complex interplay of instrumental factors, sample preparation, and computational methods. The continued development of aberration correction, direct electron detectors, and sophisticated reconstruction algorithms continues to push the boundaries of what is observable at the nanoscale. For researchers across materials science, structural biology, and pharmaceutical development, a thorough understanding of these resolution limits and measurement techniques is essential for proper experimental design and accurate interpretation of high-resolution imaging data.

Advanced EM Techniques in Action: From Battery Materials to Pharmaceutical Polymorphs

Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a revolutionary technique for determining high-resolution structures of biological macromolecules and materials without the need for crystallization. This capability is particularly crucial for studying radiation-sensitive specimens, which include most biological materials and soft matter, as they are susceptible to damage from the electron beam used in conventional electron microscopy [32] [33]. The fundamental principle of cryo-EM involves the rapid vitrification of aqueous samples to form a glass-like (vitreous) ice state, which preserves native structures in a near-physiological environment [32] [34]. Subsequent imaging at cryogenic temperatures (below -150 °C) significantly reduces radiation damage, allowing high-resolution data collection that was previously unattainable [32] [35] [33]. This methodology has transformed structural biology, materials science, and drug development by enabling researchers to visualize macromolecular complexes, viruses, and sensitive nanomaterials in their functional states.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Radiation Damage and Cryogenic Protection

Radiation damage to biological and sensitive materials arises from various interactions between illuminating electrons and specimen atoms, leading to mass loss, bond breakage, and structural alterations [35]. The primary protection mechanism in cryo-EM involves maintaining specimens at cryogenic temperatures (typically using liquid nitrogen or helium) during imaging. This reduces the adverse effects of electron irradiation by limiting atomic displacement and radical diffusion, effectively increasing the specimen's radiation tolerance [32] [35] [33]. At liquid nitrogen temperature, radiation damage is substantially reduced, allowing the use of higher electron doses to obtain images with improved signal-to-noise ratios [33].

Vitrification and Native State Preservation

Vitrification is the process of rapid cooling that transforms aqueous solutions into amorphous ice without crystal formation. Ice crystals can damage sample structures and cause strong electron diffraction that dramatically reduces resolution [34]. In practice, an aqueous sample solution is applied to a grid-mesh and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane or a mixture of liquid ethane and propane cooled to cryogenic temperatures [32]. This process occurs within milliseconds, trapping molecules in their native hydrated state and functional conformations [34] [36]. The resulting vitreous ice embeds specimens in a near-native environment, preserving structural integrity without chemical fixation, staining, or dehydration artifacts common in conventional EM techniques [34] [33].

Contrast Formation in Cryo-EM

Understanding contrast formation is essential for optimizing cryo-EM imaging. Unlike negative stain EM where heavy metals provide strong amplitude contrast, most biological macromolecules are "phase objects" that produce minimal amplitude contrast because they comprise atoms with similar atomic numbers to their aqueous buffer [37].

Phase Contrast Mechanism: Phase objects delay the electron wave, creating a phase shift without changing amplitude. Detectors record intensity (amplitude squared), making pure phase objects invisible without special imaging conditions [37]. Contrast is generated by intentionally collecting data out of focus (defocus), which introduces additional phase shifts to the scattered wave via the Contrast Transfer Function (CTF). The CTF describes the delocalization of density in sample particles caused by lens aberrations and defocus, characterized by oscillating Thon rings in Fourier space [37] [38]. Defocusing creates path length differences between scattered and unscattered electrons, leading to constructive and destructive interference that converts phase information into detectable amplitude variations [37].

Weak Phase Object Approximation: Cryo-EM commonly uses this approximation, assuming the sample only scatters a small proportion of the incoming wave, with the scattered wave having a constant π/2 phase shift. This simplifies the complex wave interaction model to a more computationally manageable form [37].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Optimization

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful cryo-EM analysis. The following protocol, adapted from JoVE with Methanocaldococcus jannaschii heat-shock protein (MjsHSP16.5) as a model system, addresses common challenges like uneven particle distribution [39].

Materials Required:

- Purified protein sample (> 0.5 mg/mL)

- Holey carbon-coated EM grids (copper or gold)

- Glow discharge system

- Vitrification device (e.g., Thermo Fisher Vitrobot)

- Cryogens: Liquid nitrogen, liquid ethane

- Dialysis membrane or size-exclusion columns for buffer exchange

Procedure:

Protein Purification and Characterization:

- Express and purify the target protein using standard chromatographic methods (e.g., affinity, ion-exchange).

- Perform final purification using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to isolate monodisperse complexes.

- Assess protein purity by SDS-PAGE and confirm homogeneity by analytical SEC or dynamic light scattering.

- Concentrate the protein to optimal concentration (typically 0.5-5 mg/mL, depending on complex size) using centrifugal filters.

- Remove aggregates by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C [39].

Buffer Optimization:

- Prepare a variety of buffer solutions with different compositions (buffer types, pH, and ionic strength) based on the target protein's biochemical properties.

- For MjsHSP16.5, a buffer containing 9 mM MOPS-Tris (pH 7.2), 50 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA was effective [39].

- Perform buffer exchange using microdialysis or SEC columns:

- Load protein solution into microdialysis buttons.

- Cover with pre-equilibrated dialysis membrane.

- Submerge in destination buffer at 4°C with buffer changes after 2 hours and continue overnight.

- Recover protein sample and measure concentration using Bradford assay [39].

Grid Preparation:

- Select appropriate grid type (amorphous holey carbon film most common).

- Render grids hydrophilic using glow discharge (60 seconds at 15 mA) [39].

- Apply 3-5 μL of optimized protein solution to the grid.

- Blot excess sample using filter paper (blot time optimized empirically, typically 2-6 seconds).

- Immediately plunge the grid into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen.

- Store vitrified grids under liquid nitrogen until data collection [32] [39].

Data Collection and Processing

Microscopy Conditions:

- Operate transmission electron microscope at 200-300 kV acceleration voltage.

- Maintain specimen temperature below -170°C throughout data collection.

- Use low-dose imaging techniques (total dose 20-40 electrons/Ų) to minimize radiation damage [36].

- Collect micrographs at multiple defocus values (typically 0.5-3.0 μm underfocus) to ensure complete frequency transfer [38] [40].

Image Processing Workflow:

- Pre-processing: Perform motion correction to compensate for beam-induced movement [40].

- CTF Estimation: Determine defocus parameters for each micrograph using programs like CTFFIND [38] [40].

- Particle Picking: Automatically select particle images from micrographs.

- 2D Classification: Group similar particle images to remove non-representative particles and assess particle quality.

- 3D Reconstruction: Generate initial model using ab initio methods or existing structures, then refine using iterative projection-matching algorithms [36].

- Post-processing: Sharpening and resolution estimation using Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cryo-EM Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Holey Carbon Grids | Sample support film | Amorphous carbon films with regularly spaced holes; choice of mesh material (Cu, Au) depends on sample properties [39] |

| Glow Discharge System | Creates hydrophilic grid surface | Ensments even sample distribution across grid; parameters require optimization for different grid types [39] |

| Liquid Ethane | Primary cryogen for vitrification | Superior heat transfer compared to liquid nitrogen alone; enables rapid cooling rates necessary for vitreous ice formation [32] |

| Optimization Buffers | Modifies sample stability and behavior | Varying composition (pH, salts, additives) addresses aggregation, preferred orientation; crucial for challenging samples [39] |

| Direct Electron Detectors | Records electron scattering events | High detective quantum efficiency (DQE) captures high-resolution information; fundamental to "resolution revolution" [32] [41] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | Final sample purification step | Removes aggregates and contaminants; ensures monodisperse sample preparation immediately before grid freezing [39] |

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Cryo-EM Versus Other Structural Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of Cryo-EM with Other Structural Biology Techniques

| Parameter | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Requirement | Minimal amounts (μL volumes), no crystallization needed [36] | Large amounts, high-quality crystals required [32] | Highly concentrated solutions, limited by molecular size |

| Resolution Range | Near-atomic to atomic (1.2-4.0 Å typical) [32] | Atomic (0.48-3.0 Å typical) [32] | Atomic for small proteins, limited to ~50 kDa |

| Native Environment | Preserved in vitreous ice [34] | Crystal packing environment | Solution state |

| Radiation Sensitivity | Reduced damage at cryogenic temperatures [35] | Radiation damage during data collection | No radiation damage |

| Size Limitations | Theoretical limit undetermined; practical challenges < 50 kDa [32] | Limited by crystal quality, not molecular size | Limited by molecular tumbling |

| Throughput | Medium (days to weeks) | Slow (crystallization bottleneck) | Fast for small proteins |

Applications to Radiation-Sensitive Materials

Cryo-EM has enabled structural studies of diverse radiation-sensitive materials previously inaccessible to high-resolution analysis:

Membrane Proteins: Cryo-EM is particularly valuable for determining structures of membrane proteins and ion channels, which are often difficult to crystallize [33]. The technique preserves these complexes in near-native lipid environments, providing insights into transport mechanisms and drug binding sites [36].

Dynamic Complexes: Single-particle analysis can resolve multiple conformational states within heterogeneous samples through computational classification [36]. This has revealed functional mechanisms in ribosomes, RNA polymerases, and other dynamic assemblies.

Viruses and Pathogens: Cryo-EM has elucidated structures of numerous viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 variants, revealing conformational changes in spike proteins that enhance infectivity [33].

Sensitive Nanomaterials: The technique has been successfully applied to radiation-sensitive nanomaterials such as perovskite nanocrystals, carbohydrate nanoparticles, and biomaterials, whose structural studies were previously limited by radiation damage [41].

Workflow and Data Processing Visualization

Diagram 1: Cryo-EM Single Particle Analysis Workflow. The process begins with sample preparation and vitrification, proceeds through data collection and computational processing, culminating in a refined 3D density map suitable for atomic model building.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Despite its transformative impact, cryo-EM presents several technical challenges that researchers must address:

Sample Optimization: Achieving high sample homogeneity remains critical [33]. Issues like preferential orientation at air-water interfaces can introduce reconstruction artifacts [39]. Buffer optimization, grid treatment, and additive screening are essential to overcome these challenges.

Size Limitations: While theoretical limits are undetermined, proteins smaller than ~50 kDa present practical challenges due to low signal-to-noise ratio [32]. Strategies like binding to antibody fragments or protein scaffolds increase effective particle size and improve reconstruction quality [32].

Resolution Limitations: Despite recent advances, most cryo-EM structures determined in 2020 were at 3-4 Å resolution, compared to a median of 2.05 Å for X-ray crystallography [32]. However, continued improvements in detectors and processing algorithms are rapidly closing this gap.

Contrast-Defocus Interplay: A 2024 benchmarking study demonstrated that for limited datasets, higher contrast images (associated with higher defocus) can yield superior resolution compared to low-defocus images, challenging conventional methodologies that prioritize low-defocus imaging for high-resolution work [40]. This highlights the importance of tailoring data collection strategies to specific experimental contexts.

Cryo-electron microscopy represents a powerful methodology for visualizing radiation-sensitive materials in their native states, overcoming fundamental limitations of conventional structural biology techniques. Through vitrification and cryogenic imaging, researchers can preserve functional conformations and study macromolecular mechanisms without crystallization requirements. While challenges remain in sample preparation for small proteins and achieving consistent atomic resolution, continued advancements in detector technology, image processing algorithms, and sample preparation methodologies promise to further expand cryo-EM's applications across structural biology, materials science, and drug development. The technique's unique capability to capture multiple conformational states and study dynamic complexes ensures its continuing role as an indispensable tool for understanding molecular structure and function.

Electron Diffraction Tomography (EDT) for Crystal Structure Analysis in Pharmaceutical Compounds

Electron Diffraction Tomography (EDT), particularly in its automated form (ADT), is an advanced structural characterization technique that is gaining significant importance in pharmaceutical research and development. This method enables the collection of three-dimensional electron diffraction data from nano-sized crystals, making it suitable for ab initio structure analysis of pharmaceutical compounds where growing large single crystals for X-ray diffraction is often impossible [42]. For the pharmaceutical industry, understanding the crystal structure of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients at the nanoscale is crucial as it directly impacts critical properties including solubility, stability, bioavailability, and manufacturability of drug products.

The technique is especially valuable for analyzing multiphase samples, polymorphs, and materials with local defects that are challenging to characterize using conventional powder X-ray diffraction methods [30]. EDT effectively bridges the gap between the need for high-resolution structural information and the practical limitations of pharmaceutical materials, which frequently exist as nano-crystalline powders or exhibit complex polymorphism that must be thoroughly characterized for regulatory approval. The ability to determine crystal structures from individual nanocrystals as small as a few hundred nanometers makes EDT particularly powerful for pharmaceutical applications where multiple solid forms may coexist or when material is limited during early development stages.

Key Advantages of EDT for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of EDT with Other Structural Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Sample Volume Required | Resolution | Pharmaceutical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Diffraction Tomography (EDT) | Nanograms (single nanocrystals) | Atomic level (structure solution) | Polymorph identification, API structure determination, nanocrystal characterization | Multiple scattering effects, requires thin samples |

| Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD) | Micrograms to milligrams (single crystals >10 μm) | Atomic level | Gold standard for complete structure determination | Requires large, well-formed single crystals |

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Milligrams (polycrystalline powder) | ~1 Å | Phase identification, quantitative analysis, polymorph screening | Limited for complex structures, reflection overlap |

| Solid-State NMR (ssNMR) | 10s-100s milligrams | Atomic environment level | Local structure, molecular motion, polymorphism | Lower resolution, requires large sample amounts |

EDT offers several distinct advantages for pharmaceutical crystal structure analysis that make it particularly valuable for drug development. First, electron diffraction patterns can be collected from single-crystal particles mere nanometers in diameter, making the technique ideal for characterizing pharmaceutical powders that effectively represent collections of single-crystal samples [30]. This capability is crucial during early drug development when only minimal amounts of material are available for characterization, or when dealing with compounds that resist crystallization into larger specimens suitable for conventional single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Second, electron diffraction demonstrates higher sensitivity to light elements such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen compared to X-ray diffraction [30]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly beneficial for pharmaceutical compounds predominantly composed of these lighter elements, allowing for more accurate determination of molecular orientation and hydrogen bonding patterns that profoundly influence solid-form properties and stability. Additionally, the almost flat Ewald sphere associated with electron diffraction results in easily interpretable diffraction patterns that represent two-dimensional sections of the reciprocal lattice, facilitating structure solution from nanocrystalline pharmaceutical materials [30].

EDT Experimental Protocol for Pharmaceutical Compounds

Sample Preparation Requirements

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EDT Analysis

| Item | Function in EDT Analysis | Pharmaceutical Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Electron Microscope with EDT capability | Data collection platform | Must support automated diffraction tomography and tilt series acquisition |

| Holey carbon TEM grids | Sample support | Copper or gold grids; 300-400 mesh size recommended |

| Double-tilt specimen holder | Crystal orientation | Enables precise tilting around multiple axes for complete data collection |

| Nanocrystalline pharmaceutical powder | Analysis target | API, polymorph, co-crystal, or salt form to be characterized |

| High-purity solvents | Sample dispersion | Methanol, ethanol, or acetone for preparing dilute suspensions |

| Ultrasonic bath | Sample dispersion | For creating homogeneous nanocrystal suspensions (30-60 seconds) |

| Anti-capillary tweezers | Grid handling | Precision tools for manipulating TEM grids during preparation |

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful EDT analysis of pharmaceutical compounds. Begin by preparing a dilute suspension of the nanocrystalline pharmaceutical powder in a volatile, high-purity solvent such as methanol or acetone using ultrasonic agitation for 30-60 seconds to ensure adequate dispersion without inducing phase transformations. Using anti-capillary tweezers, apply 2-3 μL of this suspension to a holey carbon TEM grid and allow it to dry completely in a clean, dust-free environment. For hygroscopic pharmaceutical compounds, perform grid preparation in a controlled humidity environment or glove box to prevent hydration during sample preparation. Assess the prepared grids initially using low-magnification TEM mode to identify suitably isolated nanocrystals of the target pharmaceutical compound, typically ranging from 100-500 nm in size, which represent optimal candidates for EDT data collection.

Data Collection Workflow

The EDT data collection process requires systematic acquisition of diffraction patterns while rotating the crystal around a single axis. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this process:

Begin the data collection process by identifying a well-isolated nanocrystal of the pharmaceutical compound using low-dose imaging techniques to minimize radiation damage. Orient the crystal to a starting position, typically at 0° tilt, and acquire a preliminary diffraction pattern to verify crystal quality and establish appropriate exposure conditions. Initiate the automated tilt series acquisition, collecting electron diffraction patterns at regular angular increments (typically 1°) while rotating the crystal through a tilt range of up to 180° to ensure comprehensive sampling of reciprocal space [30]. Modern implementations of Automated Diffraction Tomography (ADT) streamline this process through automation, systematically collecting hundreds of diffraction patterns while maintaining the crystal positioned in the electron beam throughout the tilt series [42]. Throughout data collection, employ dose-fractionation techniques and minimize electron exposure to preserve the structural integrity of the pharmaceutical nanocrystal, as many organic compounds are particularly sensitive to electron beam damage.

Data Processing and Structure Solution

Following data collection, process the acquired diffraction patterns using specialized software to reconstruct the three-dimensional reciprocal lattice from the collected two-dimensional diffraction patterns. This reconstruction generates a complete volumetric intensity dataset that serves as the foundation for subsequent structure solution. Extract integrated reflection intensities from this reconstructed dataset and proceed with structure solution using direct methods or charge-flipping algorithms similar to those employed in single-crystal X-ray crystallography. For pharmaceutical compounds with known molecular geometry but unknown crystal packing, consider employing molecular replacement techniques using the isolated molecular structure as a search model. Due to the frequent occurrence of dynamic scattering effects in electron diffraction, which result in intensities deviating from kinematic approximation, implement dedicated scattering correction algorithms or utilize recently developed approaches such as dynamical scattering correction to improve the accuracy of structure determination [30].

Practical Applications in Drug Development

EDT provides particular value in addressing several challenging scenarios commonly encountered in pharmaceutical development. First, the technique enables complete structure determination of new API polymorphs discovered during screening campaigns, even when these forms initially appear only as micro-crystalline material unsuitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction. This capability is crucial for establishing structure-property relationships early in development and making informed decisions about which solid forms to advance. Second, EDT can characterize minority polymorphs and phase impurities present in drug substance batches, identifying their crystal structures to understand their formation and develop appropriate control strategies. Third, the technique can resolve structures of degradation products and hydrates/solvates that may form during storage or processing, providing atomic-level insights into decomposition pathways and stability limitations.

Additionally, EDT finds application in characterizing pharmaceutical co-crystals and salts, where understanding the precise molecular interactions and packing arrangements is essential for predicting performance properties. The technique can also analyze drug-drug and drug-excipient interactions in solid formulations, providing structural insights into incompatibilities or stabilization mechanisms. For nanomedicine applications, EDT can determine the crystal structures of API nanocrystals engineered for enhanced dissolution and bioavailability, connecting nanoscale structural features to performance attributes. Finally, when dealing with patent challenges around crystal forms, EDT can provide definitive structural evidence to support intellectual property positions regarding novel solid forms.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While EDT offers powerful capabilities for pharmaceutical structure analysis, several technical considerations require attention for successful implementation. The phenomenon of multiple scattering (dynamic scattering) presents the most significant challenge, as electrons undergo several scattering events when passing through even relatively thin crystals, resulting in diffraction intensities that deviate from the kinematic approximation typically used in X-ray crystallography [30]. To mitigate this effect, employ strategies such as collecting data from the thinnest possible crystal regions, utilizing precession electron diffraction (PED) techniques that integrate over multiple slightly off-zone orientations, or applying specialized data collection protocols that optimize for quasi-kinematical data acquisition [30].

Beam sensitivity of organic pharmaceutical compounds represents another critical consideration, as the electron beam can readily damage molecular crystals, potentially altering their structure during data collection. Implement low-dose data collection strategies, utilize cryo-transfer holders to maintain samples at liquid nitrogen temperatures during analysis, and consider beam pre-conditioning approaches to minimize radiation damage effects. For complex pharmaceutical structures with large unit cells or low symmetry, ensure comprehensive data completeness by collecting tilt series over the widest possible angular range, ideally up to 180°, to minimize missing wedge artifacts and ensure adequate sampling of reciprocal space for successful structure solution.

Dual-Beam FIB/SEM for Precision Sample Preparation and 3D Nanofabrication

Within the broader context of materials characterization using electron microscopy research, Dual-Beam Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM) has emerged as a pivotal platform for nanoscale analysis and manipulation. This instrumentation combines the precise, site-specific sample modification capabilities of a focused ion beam with the high-resolution imaging of a scanning electron microscope [43] [44]. This synergy enables researchers and development professionals to conduct sophisticated investigations into the sub-surface structure and composition of a wide range of materials, from metallic alloys to biological tissues [45] [46]. The technology's ability to reveal critical structural detail—by making precise cuts with the FIB and immediately imaging the exposed surface with the high-resolution SEM—has led to its widespread adoption for solving complex materials challenges [44].

Key Applications of Dual-Beam FIB-SEM

The applications of Dual-Beam FIB-SEM are extensive and critical for advanced materials characterization. The table below summarizes the primary application areas and their significance within materials science research.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Dual-Beam FIB-SEM in Materials Characterization

| Application Area | Key Function | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| TEM Sample Preparation | Site-specific creation of electron-transparent lamellae (50–150 nm thick) for high-resolution analysis [44] [46]. | Enables atomic-resolution imaging and analysis in (S)TEM, which is fundamental for correlating microstructure with material properties [47]. |

| 3D Structural Analysis (Tomography) | Serial sectioning via sequential FIB milling and SEM imaging to generate multi-modal 3D datasets [43] [44]. | Provides crucial 3D insight into the morphology, distribution, and connectivity of phases, pores, and defects in heterogeneous materials [45]. |

| Nanoprototyping | Direct-write milling and beam-induced deposition for fabricating and modifying micro- and nanoscale devices [44]. | Accelerates R&D by allowing rapid functionality testing of nanoscale designs before committing to batch fabrication [44]. |

| Large-Volume Characterization | Use of Plasma FIB (PFIB) or Laser PFIB for cross-sectioning and analyzing millimeter-scale volumes [44] [45]. | Provides statistically relevant data and contextual information for materials with large representative volume elements, like composites and batteries [45]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Site-Specific Plan-View TEM Sample Preparation from Thin Films

This protocol, adapted from recent methodology, details the preparation of high-quality, plan-view TEM samples from thin films grown on substrates, which is essential for evaluating atomic structure and associated properties [47].

1. Sample Selection and Mounting:

- Select a substrate with a thin film of interest (e.g., BaSnO₃ on SrTiO₃ or IrO₂ on TiO₂, ranging from 20–80 nm in thickness) [47].

- Securely mount the sample onto an SEM stub using conductive tape or epoxy to ensure electrical and mechanical stability during the FIB-SEM process.

2. Initial SEM Inspection:

- Insert the sample into the Dual-Beam FIB-SEM instrument (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific Helios series) [46].

- Use the electron beam at low accelerating voltages (e.g., 1–5 kV) to locate the region of interest (ROI) on the thin film without inducing beam damage.

- Acquire secondary electron (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) images to document the initial surface morphology and material contrast.

3. Protective Layer Deposition:

- Use the electron beam or ion beam to deposit a protective layer of platinum or carbon directly over the ROI. This layer, typically 1–2 µm thick, shields the underlying film from damage during subsequent ion milling steps.

4. Rough Trench Milling:

- Using the gallium ion beam at high currents (e.g., 1–20 nA), mill two large trenches on either side of the protected ROI. This isolates a section of the thin film and provides access for lift-out.

5. Plan-View Lamella Lift-Out:

- Undercutting: Precisely mill beneath the protected ROI at a lower ion current to free it from the substrate, creating a plan-view lamella.

- Extraction: Use a micromanipulator needle (e.g., within an Easylift system) to weld, lift, and transfer the freed lamella onto a dedicated TEM grid [46].

6. Final Thinning and Cleaning:

- Weld the lamella securely to the TEM grid and cut the connection to the manipulator needle.

- Progressively thin the lamella to electron transparency (≤ 100 nm) using the ion beam at successively lower currents (e.g., from 0.5 nA down to 50 pA or lower).

- Perform a final "polishing" step at a very low energy (e.g., 2–5 kV) to remove amorphous damage layers created by higher-energy ions, resulting in a high-quality sample suitable for atomic-resolution STEM [47].

Protocol 2: Automated 3D Tomography via Serial Sectioning

This protocol outlines the procedure for generating 3D reconstructions of a sample's microstructure, which is invaluable for analyzing porous networks, composite materials, and phase distributions [44] [45].

1. Sample Preparation and Orientation:

- Prepare a polished cross-section of the material (e.g., an automotive oil filter casing, battery electrode, or rock sample) [45].

- Tilt the sample to approximately 52° to position it perpendicular to the ion beam for efficient milling and to ensure the electron beam is normal to the freshly milled surface for optimal imaging.

2. Setting Acquisition Parameters in Automation Software:

- Open the automated slice-and-view software (e.g., Auto Slice & View) [44].

- Define the milling and imaging parameters:

- Slice Thickness: Set the FIB milling depth per slice (e.g., 10–50 nm).

- Milling Current: Select an appropriate ion current for the desired slice thickness and material.