Decoding Antimicrobial Resistance: A Comprehensive Guide to Metagenomic NGS Analysis

The escalating global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demands advanced surveillance tools.

Decoding Antimicrobial Resistance: A Comprehensive Guide to Metagenomic NGS Analysis

Abstract

The escalating global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demands advanced surveillance tools. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) offers a powerful, culture-independent approach for comprehensively profiling antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) within complex microbial communities, from clinical to environmental samples. This article provides a foundational understanding of mNGS for AMR analysis, explores diverse methodological workflows and their real-world applications, addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies, and critically evaluates the technology's performance against traditional diagnostic methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and practical insights, empowering the scientific community to harness mNGS for precise AMR monitoring and the development of targeted countermeasures.

The mNGS Revolution in AMR Surveillance: Principles and Promise

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) represents a transformative approach in clinical microbiology, enabling hypothesis-free detection of pathogens directly from clinical specimens. Unlike traditional culture and targeted molecular assays, mNGS can simultaneously identify bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites without prior knowledge of the causative agent [1]. This "unbiased" detection capability is particularly valuable for diagnosing polymicrobial infections, fastidious organisms, and cases where conventional methods fail [1] [2].

The fundamental principle of mNGS involves comprehensive sequencing of all nucleic acids (DNA and/or RNA) in a clinical sample, followed by bioinformatic analysis to classify sequences against microbial reference databases [2]. This culture-independent approach bypasses the limitations of traditional methods that require specific growth conditions or targeted primer designs. A key advantage of mNGS lies in its dual capability to not only identify pathogens but also detect antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, providing critical information for treatment decisions [3] [4]. However, it is important to recognize that mNGS workflows are subject to various sources of bias introduced during sample preparation, library construction, and bioinformatic analysis, all of which can affect sensitivity and taxonomic resolution [1].

Diagnostic Performance and Comparative Analysis

Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated the superior sensitivity of mNGS compared to conventional methods across various infection types. In central nervous system infections, mNGS has demonstrated diagnostic yields as high as 63%, compared to less than 30% for conventional approaches [1]. For lower respiratory tract infections, mNGS detected bacteria in 71.7% of cases, significantly higher than culture (48.3%) [5].

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of mNGS Across Infection Types

| Infection Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comparative Method | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periprosthetic Joint Infection | 89 | 92 | Culture | Meta-analysis of 23 studies [6] |

| Pediatric Severe Pneumonia | 96.6 | 51.6 | Culture | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [5] |

| Central Nervous System Infections | ~63 | ~90 | Conventional methods | Diagnostically challenging cases [1] |

| Culture-negative PJI | Significantly higher | ~60 | Culture | Detects additional rare pathogens [2] |

For periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), a systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that mNGS exhibits higher sensitivity than targeted NGS (tNGS) while maintaining adequate specificity, confirming its clinical value for infection detection [6]. The pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing PJI were 0.89 and 0.92 for mNGS, compared to 0.84 and 0.97 for tNGS [6].

In respiratory infections, mNGS has proven particularly valuable for immunocompromised patients and those with complex clinical presentations. One study on lower respiratory tract infections established that the logarithm of reads per kilobase per million mapped reads [lg(RPKM)] showed the best performance for identifying true-positive pathogenic bacteria, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.99 and an optimal lg(RPKM) threshold of -1.35 [7].

Antimicrobial Resistance Detection Capabilities

The ability to predict antimicrobial resistance simultaneously with pathogen detection represents one of the most significant advantages of mNGS technology. By identifying resistance genes and mutations in clinical samples, mNGS provides early insights into antimicrobial susceptibility patterns before traditional phenotypic results are available [3] [4].

Table 2: Performance of mNGS for Antimicrobial Resistance Prediction

| Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various bacteria | Carbapenems | 67.74 | 85.71 | Pediatric severe pneumonia [5] |

| Various bacteria | Penicillins | 28.57 | 75.00 | Pediatric severe pneumonia [5] |

| Various bacteria | Cephalosporins | 46.15 | 75.00 | Pediatric severe pneumonia [5] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Carbapenems | 94.74 | N/R | Clinical isolates [5] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | β-lactams | >80 | N/R | 53 clinical samples [4] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Aminoglycosides | >80 | N/R | 53 clinical samples [4] |

The detection performance varies significantly among different pathogens and antibiotics. For instance, mNGS shows higher sensitivity for predicting carbapenem resistance compared to penicillins and cephalosporins [5]. In Acinetobacter baumannii, mNGS demonstrated excellent performance for detecting resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and minocycline, with class-specific accuracy exceeding 80% [4].

Recent advances in bioinformatic tools have enhanced AMR detection capabilities. The Chan Zuckerberg ID (CZ ID) AMR module represents an open-access, cloud-based workflow designed to integrate detection of both microbes and AMR genes in mNGS and single-isolate whole-genome sequencing data [3]. This tool leverages the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) and associated Resistance Gene Identifier software, enabling broad detection of both microbes and AMR genes from Illumina data [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Processing and Nucleic Acid Extraction

The standard workflow for mNGS begins with sample collection, typically from sterile sites (CSF, blood, tissue) or non-sterile sites (BALF, sputum) with different contamination control measures [1] [7]. For bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples, the protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge 1 mL of BALF at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes to collect microorganisms and human cells [5].

- Host DNA Depletion: Resuspend the precipitate in 50 μL and treat with Benzonase (1 U) and 0.5% Tween 20, followed by incubation at 37°C for 5 minutes [5]. This critical step improves microbial signal by reducing host nucleic acid contamination.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Transfer 600 μL of the mixture to tubes containing ceramic beads for bead beating using a homogenizer. Extract nucleic acid from 400 μL of pretreated samples using a commercial pathogen DNA kit, eluting in 60 μL of elution buffer [5].

- RNA Processing: For RNA extraction, use a viral RNA kit followed by removal of ribosomal RNA. Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase and dNTPs [5].

For plasma samples, collect 3 mL of peripheral blood, process within 8 hours with centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C [4]. The plasma is then transferred to sterile tubes for processing.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation follows standardized protocols with some variations between platforms:

- Library Construction: Use library construction kits according to manufacturer's instructions. For Illumina platforms, DNA/cDNA libraries are constructed using the KAPA low throughput library construction kit [5].

- Enrichment: For targeted approaches, aliquot 750 ng of library from each sample for hybrid capture-based enrichment of microbial probes through one round of hybridization [5].

- Quality Control: Assess library quality using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit followed by the High Sensitivity DNA kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer [5].

- Sequencing: Load library pools onto sequencers (e.g., Illumina Nextseq CN500) for 75 cycles of single-end sequencing, generating approximately 20 million reads for each library [5].

For BGI platforms, the process includes enzymatic digestion, end repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification to generate sequencing libraries. Verify fragment sizes (approximately 300 bp) using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and determine library concentrations using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [4].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of mNGS data involves multiple steps to distinguish true pathogens from background noise and contaminants:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Raw sequencing reads undergo deduplication, trimming, and quality filtering using tools like fastp [5] [4].

- Host Read Removal: Map reads to the human genome (GRCh38) using alignment software such as Bowtie2 or BWA, then remove matching sequences [5] [3] [4].

- Taxonomic Classification: Classify remaining reads using tools like Centrifuge against comprehensive microbial databases containing bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic reference genomes [5].

- AMR Gene Detection: Two parallel approaches are commonly used:

- Pathogen-of-Origin Prediction: Use k-mer-based approaches to link AMR genes to specific pathogen species and predict chromosomal versus plasmid location [3].

The CZ ID platform automates this workflow in a cloud-based environment, making analysis accessible to researchers with limited bioinformatics expertise [3]. A sample with 50 million reads typically takes less than 5 hours to process after upload [3].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for mNGS Workflow

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini Kit | Pathogen DNA extraction from clinical samples | Effective for low-biomass samples [5] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp Viral RNA Kit | RNA extraction for viral detection | Maintains RNA integrity [5] |

| Host Depletion | Benzonase + Tween 20 | Host nucleic acid degradation | Critical for improving microbial signal [5] |

| Library Preparation | KAPA low throughput library construction kit | Library construction for Illumina platforms | Optimized for low-input samples [5] |

| Target Enrichment | SeqCap EZ Library (Roche) | Hybrid capture-based enrichment | Improves sensitivity for targeted pathogens [5] |

| rRNA Depletion | Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit | Ribosomal RNA removal for RNA sequencing | Enhances non-rRNA transcript detection [5] |

| Quality Control | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | DNA quantification | Accurate measurement of low-concentration samples [5] [4] |

| Quality Control | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Fragment size analysis | Quality assessment of libraries [5] [4] |

| Database | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | AMR gene reference | Curated resistance gene information [3] |

| Analysis Tool | Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) | AMR gene detection | Matches sequences to CARD database [3] |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promising capabilities, mNGS implementation faces several technical and operational challenges. Sample processing workflows often require host DNA depletion to improve microbial signal in low-biomass specimens, and bioinformatic pipelines must be standardized to ensure reproducibility [1]. The high abundance of host-derived nucleic acids remains a significant barrier, particularly in blood and tissue samples [1].

Regulatory frameworks are beginning to accommodate metagenomic assays, but validation procedures and reimbursement models remain inconsistent and underdeveloped [1]. Ethical considerations, including incidental findings, patient privacy, and disparities in access, must be addressed to ensure equitable implementation [1].

Future directions involve artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate taxonomic classification, AMR gene detection, and clinical reporting, reducing turnaround times and improving interpretability [1]. Emerging approaches such as host transcriptome profiling and single-cell RNA sequencing are showing promise in differentiating bacterial versus viral infections and predicting disease severity [1]. Combining host immune signatures with microbial sequencing data may enable real-time, precision-guided infectious disease management [1].

Ultra-portable sequencing technologies capable of generating results within hours are being evaluated for use in emergency departments, border surveillance, and field hospitals [1]. These advancements, coupled with open-access platforms like CZ ID that democratize pathogen genomic analysis, represent important steps toward collaborative efforts to combat the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance [3].

Application Note: Overcoming the Limitations of Traditional Antimicrobial Resistance Detection

The pervasive threat of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) necessitates a paradigm shift in surveillance and diagnostic strategies. Traditional, culture-based methods are fundamentally limited by their inability to capture the vast majority of environmental microbes, their predisposition toward known pathogens, and their narrow scope [8] [9]. This application note details how metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) addresses these critical gaps through its three core advantages: culture-independence, hypothesis-free discovery, and comprehensive analysis of the resistome. By providing a direct, unbiased view of the genetic material in any sample, mNGS is transforming our ability to monitor and understand AMR dynamics across human, animal, and environmental ecosystems [10].

Quantitative Advantages of mNGS over Traditional AST

The table below summarizes the performance of mNGS against traditional antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods across key parameters.

Table 1: A comparative analysis of metagenomic NGS and traditional methods for AMR profiling.

| Feature | Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | Traditional Culture & AST |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency on Culture | Culture-independent; analyzes genetic material directly from samples [1] | Mandatory; requires isolation and growth of pathogens [9] |

| Discovery Capability | Hypothesis-free; detects novel, unexpected, and co-infecting pathogens and ARGs [11] [1] | Targeted; only identifies pre-selected, cultivable organisms [8] |

| Scope of Analysis | Comprehensive; profiles all ARGs, virulence factors, and mobile genetic elements in the "resistome" [8] [10] | Narrow; typically profiles resistance in a single, isolated pathogen [9] |

| Turnaround Time | ~5-9 hours for pathogen ID and first AMR gene detection with rapid protocols [12] | 16-20 hours for MIC results alone, plus additional time for culture [13] [14] |

| Throughput | High-throughput; capable of processing and sequencing multiple samples in parallel [9] | Low-throughput; intensive manual labor for each isolate [15] |

| Key Limitation | High computational complexity and cost; challenges in genotype-phenotype correlation [11] [14] | Fails for non-culturable, fastidious, or slow-growing organisms [1] [9] |

Protocol: A Detailed Workflow for mNGS-Based Resistome Analysis

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for shotgun metagenomic sequencing to characterize the antibiotic resistome in complex samples, such as clinical specimens or environmental samples. The workflow incorporates best practices for host DNA depletion to ensure sufficient microbial sequencing coverage.

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Sample Collection and Pre-processing

- Sample Types: Collect samples (e.g., fecal matter, water, soil, milk) in sterile containers [10]. Transport immediately in a cold chain (2-8°C) to the laboratory [10].

- Critical Pre-processing for High-Host-DNA Samples: For samples like milk or blood that contain abundant host DNA, a dedicated host DNA depletion step is crucial.

- Method: Use a combination of a commercial host depletion kit (e.g., MolYsis Complete5), 10% bile extract (Ox bile), and micrococcal nuclease treatment [12].

- Rationale: This combination has been shown to effectively enrich bacterial DNA, reducing bovine DNA reads to an average of 17% while increasing pathogen (Staphylococcus aureus) reads to 66.5% [12].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

- DNA Extraction: Perform extraction using kits validated for complex samples, such as the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit for fecal samples or the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit for environmental samples [10]. Assess DNA concentration and integrity using a fluorometer and agarose gel electrophoresis [10].

- Library Preparation: Use ~1 ng of genomic DNA with a high-throughput library preparation kit (e.g., Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit). Clean up the libraries using AMPure XP beads [10].

Sequencing and Real-Time Analysis

- Platform Selection: For real-time analysis, use a long-read sequencer like the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION. For high-accuracy short-read data, use an Illumina platform [1] [9].

- Sequencing Execution: Pool normalized libraries and load onto the sequencer. For rapid results, even a 40-minute MinION run can be sufficient for initial bacterial identification and detection of the first AMR genes [12].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

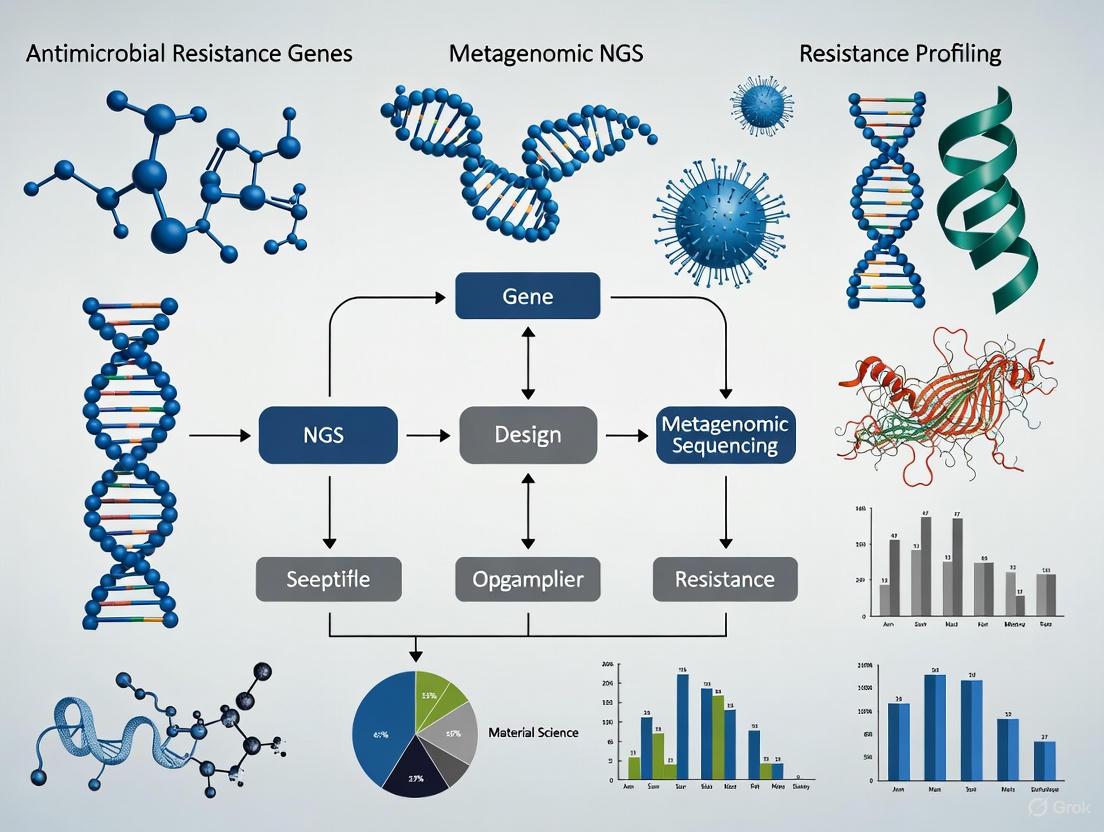

The following diagram illustrates the core bioinformatic workflow for processing mNGS data to profile AMR.

Diagram 1: Bioinformatic workflow for mNGS-based AMR analysis.

- Quality Control: Process raw sequences (e.g., using FASTP) to eliminate low-quality reads and adapters [16].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Use tools like MetaPhlAn to classify the microbial community composition against databases of clade-specific marker genes [10].

- Metagenome Assembly: De novo assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT [16].

- ARG and MGE Annotation: Predict open reading frames (ORFs) from contigs (e.g., with Prodigal). Annotate these ORFs against curated ARG databases (e.g., deepARG) and MGE databases using BLAST-based tools (e.g., DIAMOND) with strict E-value cut-offs (e.g., ≤ 1e-5) [16] [8].

- Advanced Analysis: For higher-resolution analysis, perform metagenomic binning (e.g., with MetaWRAP) to generate metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). This allows for the direct linkage of ARGs with specific bacterial hosts and their pathogenic potential [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key reagents, kits, and databases essential for conducting mNGS-based AMR studies.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Host DNA Depletion Kit | Selectively degrades host DNA to enrich for microbial sequences in high-host-content samples. | MolYsis Complete5, MolYsis Plus [12] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from complex matrices (stool, soil, water). | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, DNeasy PowerFood Microbial Kit [16] [10] |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from extracted DNA. | Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit [10] |

| Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput sequencing of prepared libraries. | Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq (short-read), Oxford Nanopore MinION (long-read) [16] [12] |

| ARG Reference Database | Curated collection of sequences for annotating and identifying antibiotic resistance genes. | deepARG, METABOLIC, VB12Path (for specific metabolic traits) [16] [8] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Software and pipelines for data QC, assembly, taxonomic profiling, and functional annotation. | FASTP, MEGAHIT, MetaPhlAn, Prodigal, DIAMOND, MetaWRAP [16] [10] |

Integrated Data Analysis and Visualization

The power of mNGS is fully realized in the integration of different data layers. As demonstrated in a study of urban lakes, binning analysis can reconstruct Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) that actively participate in specific metabolic processes (like vitamin B12 synthesis) while also carrying ARGs and demonstrating pathogenicity [16]. This level of integration provides unprecedented insight into the hosts and co-factors of resistance dissemination.

From Data to Actionable Insights

The final stage involves synthesizing the analyzed data into a coherent report that includes:

- The Resistome Profile: A list of detected ARGs and their abundances.

- Pathogen Identification: A list of detected pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- Mobility Assessment: Identification of MGEs (plasmids, integrons, transposons) co-located with ARGs, indicating horizontal transfer potential [8].

- Risk Evaluation: Tools like MetaCompare can be employed to estimate resistome risk by evaluating the coexistence of ARGs, MGEs, and human pathogens [16].

Resistome Profiling, Horizontal Gene Transfer, and Mobile Genetic Elements

Resistome profiling refers to the comprehensive analysis of all antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) within a microbial community (the 'resistome') [17]. This approach leverages metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to detect and characterize ARGs directly from clinical or environmental samples, bypassing the need for culturing and enabling the surveillance of resistant pathogens and the discovery of novel resistance mechanisms [10] [1]. A critical force shaping the resistome is horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which allows the rapid sharing of genetic material between bacteria, including ARGs [10]. This process is primarily facilitated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids, transposons, and integrons, which act as vectors for the acquisition and dissemination of resistance traits among bacterial populations [18] [19]. The interplay between these concepts is fundamental to understanding the evolution and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a major global health threat causing millions of deaths annually [1].

Table 1: Key Concepts in AMR Research

| Concept | Description | Role in AMR |

|---|---|---|

| Resistome | The full collection of antibiotic resistance genes in a microbial community [17]. | Defines the potential for resistance in a given environment or sample. |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | The movement of genetic material between bacteria that are not in a parent-offspring relationship [10]. | Enables rapid acquisition and spread of ARGs across bacterial populations and species. |

| Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) | DNA sequences that can move within or between DNA molecules and cells [18] [19]. | Acts as a vehicle for ARGs during HGT, driving the evolution of multidrug-resistant pathogens. |

Experimental Protocols for Resistome Analysis

This section details standard and emerging wet-lab and computational protocols for resistome profiling, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Sample Processing and Metagenomic Sequencing

The initial phase involves extracting total DNA from diverse samples to prepare sequencing libraries.

Protocol: Metagenomic DNA Sequencing for Resistome Profiling

- Sample Collection: The protocol begins with the collection of samples from targeted environments. For instance, studies have analyzed human and animal fecal samples, soil, drinking water, and riverbed sediments [10]. Samples should be immediately transported on ice or preserved using reagents like RNAlater.

- DNA Extraction: Total genomic DNA is extracted using commercial kits. For fecal samples, the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit is commonly used, while environmental samples like soil may require the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [10]. DNA concentration and integrity are quantified using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Following extraction, 1 ng of genomic DNA is used as input for library preparation with kits such as the Illumina MiSeq Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit [10]. The constructed libraries are then sequenced on platforms like the Illumina MiSeq to generate paired-end reads (e.g., 2x151 bp). For applications requiring long reads or point-of-care testing, portable Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencers like the MinION can be deployed [1].

Targeted Enrichment for Cost-Effective Resistome Profiling

While shotgun metagenomics is powerful, targeted enrichment can be a more cost-effective strategy for deepening the sequencing of specific genes.

Protocol: Targeted Resistome Profiling using CARPDM-Generated Probe Sets

- Principle: This method uses hybridization probes to enrich metagenomic DNA for ARG sequences prior to sequencing, significantly increasing the number of reads mapping to resistance genes and lowering detection limits [20].

- Probe Set Design: The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Probe Design Machine (CARPDM) software is used to generate open-source, up-to-date hybridization probe sets from the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [20]. Two example sets are:

- allCARD: Targets all genes in CARD's protein homolog models (n=4,661).

- clinicalCARD: Focuses on a clinically relevant subset of genes (n=323).

- In-House Probe Synthesis: A key feature of this protocol is a method for in-house synthesis of probe sets, which can save up to $350 per reaction, making the technique more accessible [20].

- Enrichment and Sequencing: The synthesized probes are used in a bait-capture hybridization with the metagenomic DNA. The enriched DNA is then sequenced, with demonstrated increases in resistance-gene mapping reads of up to 594-fold for allCARD and 598-fold for clinicalCARD [20].

Targeted Resistome Profiling Workflow

Bioinformatic Analysis for Resistome Characterization

After sequencing, raw data is processed to identify and quantify ARGs and their genetic contexts.

Protocol: Computational Resistome Analysis from mNGS Data

- Gene Prediction: For assembled metagenomic contigs or whole genomes, gene prediction is performed using tools like Prodigal (v2.6.3) with the 'meta' option specified [21].

- ARG Annotation: Predicted genes are compared against specialized ARG databases using BLASTp. Standard parameters include:

- Clustering and Abundance Calculation: To resolve redundancy, ARGs can be clustered into families using algorithms like the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm [21]. The relative abundance of ARGs is calculated as the number of ARGs divided by the total number of predicted genes in the sample [21].

- High-Resolution Profiling with GROOT: For unassembled sequencing reads, tools like GROOT (Graphing Resistance Out Of meTagenomes) offer a fast and accurate alternative. GROOT uses a variation graph representation of ARG databases and a locality-sensitive hashing Forest indexing scheme to rapidly classify reads and reconstruct full-length gene sequences, improving accuracy in profiling similar ARG variants [17]. It can process a 2 GB metagenome in approximately 2 minutes on a single CPU [17].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Resistome Profiling

| Category | Item / Tool | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | DNA extraction from fecal samples [10]. |

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | DNA extraction from complex environmental samples like soil [10]. | |

| Illumina MiSeq Nextera XT Kit | Library preparation for shotgun metagenomic sequencing [10]. | |

| CARPDM Probe Sets | Custom hybridization probes for targeted enrichment of ARGs from CARD [20]. | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Prodigal | Prediction of protein-coding genes in metagenomic and genomic sequences [21]. |

| GROOT | Fast resistome profiling directly from metagenomic reads using variation graphs [17]. | |

| MetaPhlAn | Profiling microbial community composition from metagenomic data [10]. | |

| Reference Databases | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | Curated repository of ARGs, proteins, and antibiotics [20]. |

| ISfinder | Centralized database for insertion sequences (IS) [18] [19]. |

Investigating Horizontal Gene Transfer and MGEs

Understanding the dynamics of AMR requires moving beyond a simple catalog of ARGs to analyze their mobilization via HGT and MGEs.

Key Mobile Genetic Elements in AMR

MGEs are diverse and facilitate the movement of ARGs through different mechanisms.

- Insertion Sequences (IS): These are the simplest MGEs, typically short sequences ( <3 kb) containing only a transposase gene flanked by inverted repeats [18]. They can insert into genes, potentially inactivating them, or provide promoters that drive the expression of adjacent ARGs [19]. For example, ISAba1 inserted upstream of the blaOXA-51-like gene in Acinetobacter baumannii can lead to carbapenem resistance [19].

- Transposons: These are larger than IS and carry additional genes, such as ARGs. Composite transposons consist of a cargo gene (e.g., an ARG) flanked by two copies of the same or related IS, which can mobilize the entire unit [18] [19]. An example is Tn10, which carries a tetracycline resistance gene [19].

- Integrons: These are genetic platforms that can capture and express gene cassettes, most commonly ARGs [19]. They contain an intI gene encoding an integrase, a recombination site (attI), and a promoter for expressing the captured genes [18].

- Plasmids and ICEs: Plasmids are self-replicating MGEs that can transfer between cells via conjugation and often carry multiple ARGs [18] [22]. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) can excise from the chromosome and transfer to a recipient cell via conjugation [18].

Protocol: Detecting HGT and MGE-Associated ARGs

Long-read sequencing is critical for resolving the genomic context of ARGs, as short reads cannot span repetitive MGE sequences.

Protocol: Resolving ARG Context with Long-Read Sequencing

- Principle: Long-read sequencing technologies, such as those from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), generate reads that are thousands of bases long. This allows them to span entire MGEs and resolve whether an ARG is located on a chromosome or a plasmid, and its specific association with IS, transposons, or integrons [22].

- Procedure: High-molecular-weight DNA is extracted and sequenced on a long-read platform. The resulting reads are assembled into complete, closed genomes (for isolates) or higher-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). ARGs and MGEs are then annotated in the assembled genomes. The proximity and linkage of ARGs to MGEs are analyzed to provide direct evidence of their mobilizable nature [22].

- Application: This approach has been used to demonstrate that antibiotic selection can drive the duplication of ARGs via transposition in experimental evolution, and that duplicated ARGs are highly enriched in clinical and livestock-associated bacterial isolates, indicating strong ongoing selection [22].

MGEs as ARG Vectors

Integrated Application Notes

The combined application of these protocols provides powerful insights into AMR dynamics across different environments.

- One Health Surveillance: A study in Kathmandu, Nepal, used shotgun metagenomics on human, avian, and environmental samples, identifying 53 ARG subtypes [10]. Poultry samples showed the highest ARG diversity, suggesting intensive antibiotic use in agriculture as a key driver. The study also detected frequent HGT events, identifying gut microbiomes as critical reservoirs for ARGs, thus underscoring the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in the spread of AMR [10].

- Environmental Monitoring: Resistome profiling of urban gutter ecosystems in India revealed high levels of bacteria resistant to penicillin, cephalosporin, and other antibiotic classes [23]. Beta-lactamase activity was confirmed via a nitrocefin hydrolysis assay. Metagenomic analysis further linked the resistome to specific microbial families like Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonadaceae, and to metabolic pathways that may indirectly foster resistance development [23].

- Occupational Risk Assessment: Metagenomic analysis of a composting facility identified airborne human-pathogenic antibiotic-resistant bacteria (HPARB) carrying a greater diversity and abundance of ARGs and virulence factors than those found in the compost itself [24]. Key enriched ARGs in the air included mexF, tetW, and vanS, highlighting an underappreciated route of occupational exposure to enhanced AMR risks [24].

Linking Microbial Community Dynamics to Antibiotic Resistance Gene Abundance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents a major global threat to public health and ecosystems, with drug-resistant infections projected to cause nearly 2 million deaths annually by 2050 [25]. The resilience and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) within microbial communities are heavily influenced by complex ecological dynamics and environmental factors. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a transformative tool for analyzing ARGs in diverse microbial communities without cultivation, enabling comprehensive insights into resistance mechanisms and transmission pathways [8] [26].

This Application Note provides detailed protocols for investigating the relationship between microbial community dynamics and ARG abundance using metagenomic approaches. We present standardized methodologies for sample processing, DNA extraction, sequencing, and computational analysis, with particular emphasis on tracking mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that facilitate horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Metagenomics and qPCR for ARG Analysis

| Parameter | Metagenomic Sequencing | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Coverage | Broad coverage of known and novel ARGs [27] | Limited to targeted ARGs with known sequences [27] |

| Sensitivity | Lower sensitivity for rare ARGs [27] | High sensitivity for detecting low-abundance targets [27] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Relative abundance based on read mapping [27] | Absolute quantification with high accuracy [27] |

| Throughput | High-throughput, community-wide profiling [8] | Medium throughput, limited by primer availability [28] |

| MGE Detection | Can link ARGs to plasmids, integrons, phages [25] [8] | Requires separate assays for MGE targets [28] |

| Cost per Sample | Higher | Lower |

Table 2: Temporal Dynamics of ARG Classes in Urban Wastewater [28]

| ARG Class | Detection Frequency (%) | Absolute Abundance Range (copies/L) | Dominant Gene Subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | 70-90% | 6.94×10⁴ - 9.47×10⁴ | aph, aadA1, strB, aadA-02 |

| β-lactams | 70-87% | 9.36×10³ - 2.17×10⁴ | blaOXY, fox5, blaCTXM-01, blaOXA-30 |

| Sulfonamides/Trimethoprim | 67-83% | 8.83×10³ - 1.09×10⁴ | dfrA, sul2 |

| Multidrug | 50-70% | 3.25×10³ - 5.19×10³ | Multiple efflux pumps |

| MLSB | 50-65% | 1.94×10³ - 4.66×10³ | erm, mef, msr |

| Tetracyclines | 45-60% | 2.07×10³ - 3.20×10³ | tet(M), tet(32), tet(35) |

Metagenomic Co-Assembly Protocol for Enhanced ARG Detection

Principle

Co-assembly merges sequencing data from multiple related samples to improve gene recovery and facilitate detection of low-abundance ARGs that may be missed in individual assemblies. This approach is particularly valuable for low-biomass samples like airborne microbiomes where sequencing depth may be limited [25].

Materials and Reagents

- DNA extraction kit optimized for environmental samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit)

- Quality control reagents: Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit, Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit

- Library preparation kit: Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina)

- Sequencing reagents: Illumina NextSeq or NovaSeq sequencing chemistry

- Bioinformatics software: MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes assembler, BBtools for quality control

Procedure

Sample Grouping Strategy

- Group samples based on taxonomic and functional characteristics

- Ensure similar environmental origins or experimental conditions

- Recommended group size: 5-10 samples for optimal co-assembly [25]

Sequencing Read Pooling

- Pool quality-filtered reads from all samples in the group

- Use consistent normalization approaches to avoid bias

- Recommended sequencing depth: ~30 million reads per group for saturation [25]

Co-assembly Execution

- Run MEGAHIT with metagenomic mode:

megahit -r pooled_reads.fq -o coassembly_output --min-contig-len 500 - Alternatively, use metaSPAdes:

metaspades.py -o coassembly_output -s pooled_reads.fq

- Run MEGAHIT with metagenomic mode:

Quality Assessment

- Compare assembly metrics: genome fraction, duplication ratio, mismatches per 100 kbp

- Evaluate contig length distribution (N50, maximum contig length)

- Validate with reference genomes representing expected taxa

Gene Prediction and Annotation

- Predict open reading frames using Prodigal:

prodigal -i coassembly.fna -a proteins.faa -p meta - Annotate ARGs using RGI with CARD database:

rgi main -i proteins.faa -o arg_annotations -t protein

- Predict open reading frames using Prodigal:

Expected Results

Co-assembly typically produces longer contigs (762,369 contigs ≥500 bp) compared to individual assembly (455,333 contigs), with significantly greater total contig length (555.79 million bp vs. 334.31 million bp) [25]. This enhances the ability to link ARGs to mobile genetic elements and determine genomic context.

Integrated Workflow for Community-ARG Dynamics

Workflow for analyzing microbial community dynamics and ARG abundance

Tracking Mobile Genetic Elements and Horizontal Gene Transfer

MGE Detection Protocol

Principle: Identify plasmids, integrons, transposons, and bacteriophages that facilitate horizontal transfer of ARGs between diverse microbial taxa [8].

Procedure:

Extract Contigs Potentially Encoding MGEs

- Screen assembled contigs using PlasFlow for plasmid identification

- Run geNomad for viral and plasmid sequence detection

- Use IntegronFinder for integron identification

Identify ARG-MGE Linkages

- Detect ARGs and MGEs on same contig using RGI and mobileOG-db

- Calculate linkage probability based on genetic distance

- Apply network analysis to identify ARG-MGE co-occurrence patterns

Validate HGT Potential

- Analyze flanking sequences of ARGs for MGE-associated features

- Identify insertion sequence elements adjacent to ARGs

- Detect integron cassette structures containing ARGs

Expected Results: In atmospheric samples, co-assembly approaches reveal ARGs against aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, fosfomycin, glycopeptides, quinolones, and tetracyclines, though many may not be clearly linked to mobile elements due to community complexity [25].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Product/Tool | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | DNA extraction from diverse environmental samples | Optimal for low-biomass samples [25] |

| Wet Lab | Nextera XT DNA Library Prep | Metagenomic library preparation | Compatible with low-input DNA [27] |

| Bioinformatics | ResistoXplorer | Visual, statistical analysis of resistome data | Web-based tool for exploratory analysis [29] |

| Bioinformatics | AMRViz | Genomics analysis & visualization of AMR | Provides end-to-end pipeline management [30] |

| Bioinformatics | MEGAHIT | Metagenome assembly | Efficient for complex communities [25] |

| Database | CARD Database | Reference ARG sequences | Comprehensive resistance gene database [26] |

| Database | ResFinder | ARG detection & subtyping | Specialized for resistance surveillance [27] |

| Analysis | RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier) | ARG annotation from sequences | Integrates with CARD database [26] |

Data Analysis and Visualization Protocol

Statistical Analysis of Community-ARG Associations

Procedure:

Normalization and Transformation

- Apply CSS normalization to account for uneven library sizes

- Use log-ratio transformations for compositional data

- Rarefy to even sequencing depth when comparing alpha diversity

Differential Abundance Testing

- Implement metagenomeSeq with zero-inflated Gaussian model

- Use DESeq2 or edgeR adapted for metagenomic data

- Apply Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing

Network Analysis

- Construct co-occurrence networks using SparCC or SPIEC-EASI

- Calculate topological features: betweenness centrality, modularity

- Identify keystone taxa influencing ARG distribution

Temporal Analysis

- Track persistent (core) versus transient ARGs across time series

- Calculate ARG turnover rates using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity

- Identify seasonal patterns in resistance prevalence [28]

Visualization with ResistoXplorer

Procedure:

Upload Data Format

- Prepare ARG abundance table with samples as columns, genes as rows

- Include metadata table with experimental factors

- Format according to ResistoXplorer specifications [29]

Composition Profiling

- Generate alpha diversity rarefaction curves

- Create ordination plots (PCoA, NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis distances

- Visualize ARG class distribution across sample groups

Functional Profiling

- Aggregate ARGs by drug class resistance mechanism

- Compare functional profiles across experimental conditions

- Identify enriched resistance mechanisms

Association Network Visualization

- Construct ARG-microbe association networks

- Apply enrichment analysis to identify significant associations

- Export publication-quality figures

Applications and Case Studies

Atmospheric ARG Transport During Dust Storms

Background: Airborne transport represents an understudied pathway for ARG dissemination across geographical barriers [25].

Methods Implementation:

- Sample air during clear weather and dust storm events

- Apply metagenomic co-assembly to enhance gene recovery

- Link detected ARGs to potential bacterial hosts

- Assess mobility potential through MGE association

Key Findings: Co-assembly of atmospheric samples reveals resistance genes against clinically important antibiotics, demonstrating potential for long-range airborne spread of antibiotic resistance [25].

Wastewater-Based Epidemiology of Community AMR

Background: Urban wastewater provides integrated assessment of community-wide resistance patterns [28].

Methods Implementation:

- Collect wastewater samples monthly over 5-month period

- Extract DNA and analyze 123 ARGs and 13 MGEs using qPCR

- Identify persistent (core) versus transient resistance genes

- Correlate ARG abundance with seasonal factors

Key Findings: Approximately 50% of tested ARG subtypes were consistently detected across all months, with maximum absolute abundance in winter months, highlighting persistent core resistome in urban communities [28].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 4: Common Technical Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low ARG detection sensitivity | Insufficient sequencing depth | Increase to ≥30 million reads; implement co-assembly [25] |

| Incomplete MGE linkage | Fragmented assemblies | Apply long-read sequencing; use hybrid assembly approaches |

| High false positive ARGs | Database mismatches | Use curated databases; apply conservative identity thresholds |

| Poor community resolution | Low biomass sample | Optimize DNA extraction; include amplification steps |

| Inconsistent temporal patterns | Sampling frequency | Increase sampling points; align with environmental drivers [28] |

| Compositional data artifacts | Uneven library sizes | Apply proper normalization (CSS, log-ratio) [29] |

This protocol collection provides comprehensive methodologies for investigating the dynamic relationships between microbial communities and antibiotic resistance genes. The integrated approach combining wet lab procedures, bioinformatics analyses, and visualization tools enables researchers to track the emergence and dissemination of resistance determinants across diverse environments. Standardized application of these protocols will enhance comparability across studies and contribute to the global understanding of antimicrobial resistance dynamics within the One Health framework.

The Critical Role of Bioinformatics and Reference Databases in Data Interpretation

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents a critical global health challenge, linked to millions of deaths annually [31]. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a transformative tool for infectious disease diagnostics, enabling the hypothesis-free detection of a broad spectrum of pathogens and their resistance genes directly from clinical samples [31]. However, the power of this culture-independent approach is entirely dependent on robust bioinformatics pipelines and comprehensive reference databases. Without sophisticated computational tools, the vast and complex datasets generated by mNGS are uninterpretable. This application note details the essential protocols and resources for accurately identifying AMR genes from mNGS data, framing them within the critical context of data interpretation for researchers and drug development professionals.

The fundamental challenge in mNGS for AMR analysis lies in distinguishing genuine resistance determinants from background noise and understanding their clinical relevance. Unlike whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of isolated bacterial strains, mNGS involves sequencing all nucleic acids in a sample, resulting in a mixture of host, pathogen, and environmental DNA [31]. This complexity introduces several analytical hurdles, including high levels of host DNA, the need for sensitive detection of low-abundance genes, and the functional annotation of discovered genes. Bioinformatics tools and curated databases are the essential components that overcome these hurdles, translating raw sequence data into actionable insights for managing drug-resistant infections.

Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Databases for AMR Detection

A wide array of bioinformatic tools has been developed to identify AMR genes from sequencing data. These tools primarily function by comparing sequenced DNA or protein fragments against curated databases of known resistance genes and mutations. The selection of the tool and database directly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy of the analysis. Key tools include ResFinder, the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), AMRFinderPlus, and newer, more comprehensive platforms like AmrProfiler [32] [33].

These tools differ in their algorithms, database composition, and the types of resistance mechanisms they detect. While early tools focused mainly on acquired resistance genes, modern pipelines have expanded to detect chromosomal mutations, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) mutations, and other complex resistance mechanisms. For instance, AmrProfiler is the first tool to systematically report mutations in rRNA genes, which is critical for identifying resistance to antibiotics like macrolides and oxazolidinones in Gram-positive bacteria [32]. The choice of tool often depends on the specific application, the required comprehensiveness, and the user's bioinformatics expertise.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Bioinformatic Tools for AMR Gene Detection

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Database Source & Size | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmrProfiler | Identifies acquired AMR genes, core gene mutations, and rRNA mutations. | Integrates ResFinder, CARD & Reference Gene Catalog; 7,588 unique AMR gene alleles [32]. | Three specialized modules; analyzes ~18,000 bacterial species; reports rRNA copy number mutation ratio. | Web server dependent; may have processing delays with large datasets. |

| ResFinder | Detects acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. | Custom database; 3,150 alleles [32]. | User-friendly online platform; widely used and cited. | Limited coverage for point mutations; can miss known AMR genes [32]. |

| CARD | Comprehensive identification of AMR genes and mutations. | Custom curated database; 4,793 unique AMR gene alleles [32]. | Extensive ontology of resistance terms; includes broad mechanism data. | Confidence in AMR relevance can be low for some entries [32]. |

| AMRFinderPlus | Detects AMR genes, point mutations, and stress resistance elements. | NCBI Reference Gene Catalog; 6,637 AMR gene alleles [32]. | Detects a wide range of mechanisms; stand-alone tool. | Can be challenging for non-bioinformaticians to use [32]. |

Protocol for AMR Gene Detection from mNGS Data

Sample Processing, Sequencing, and Quality Control

The initial steps involve converting a clinical sample into high-quality sequencing data suitable for bioinformatic analysis.

- Sample Collection & Nucleic Acid Extraction: Collect clinical specimen (e.g., blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, cerebrospinal fluid) in appropriate sterile containers. Extract total DNA/RNA using standardized commercial kits, ensuring sufficient yield and integrity. For RNA viruses, include a reverse transcription step to generate cDNA.

- Library Preparation & Host DNA Depletion: Convert the extracted nucleic acids into a sequencing library using library preparation kits. This typically involves fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. To significantly improve the detection of microbial content, implement host DNA depletion techniques (e.g., probe-based hybridization) prior to or during library prep, especially for samples with high human host content [31].

- Sequencing: Load the prepared library onto a next-generation sequencer (e.g., Illumina, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), or PacBio). For short-read platforms, aim for a minimum of 10-20 million reads per sample. ONT's portable devices like the MinION enable real-time, point-of-care sequencing [31].

- Raw Data Quality Control & Preprocessing: Perform initial quality assessment on the raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files). Use tools like FastQC to evaluate per-base sequence quality, GC content, and adapter contamination. Subsequently, preprocess the reads with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases, sequencing adapters, and short reads.

Bioinformatic Analysis for AMR Gene Identification

This core protocol transforms quality-controlled reads into a list of annotated AMR genes.

- Taxonomic Profiling (Optional but Recommended): Classify the sequencing reads to determine the microbial composition of the sample. This provides context for the AMR genes found. Tools like Kraken2 or Centrifuge can be used for rapid taxonomic assignment.

- Resistance Gene Detection: This is the central step for AMR analysis. This protocol uses AmrProfiler as a comprehensive example.

- Input: Preprocessed reads (after step 4 above) should be assembled into contigs using a de novo assembler like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes. The final assembly (FASTA file) is the input for AmrProfiler.

- Tool Access: Navigate to the AmrProfiler web server at

https://dianalab.e-ce.uth.gr/amrprofiler[32]. - Module 1 - Acquired AMR Genes:

- Upload the genome assembly file.

- Select the "Acquired AMR Genes" module.

- Set user-defined thresholds for identity (e.g., ≥90%) and coverage (e.g., ≥80%) to filter hits. This ensures high-confidence matches.

- Execute the analysis. The tool performs a BLASTX search against its curated database of 7,588 AMR gene alleles [32].

- Module 2 - Core Gene Mutations:

- Select the "Core Gene Mutations" module.

- Specify the bacterial species of interest from the ~18,000 available.

- Run the analysis to detect mutations in resistance-associated core genes (e.g., gyrA, parC) compared to a reference genome.

- Module 3 - rRNA Genes and Mutations:

- Select the "rRNA Genes and Mutations" module.

- This module identifies all 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA gene copies and detects mutations compared to the species-specific reference, calculating the mutated-to-total rRNA copy number ratio [32].

- Results Interpretation: AmrProfiler generates a table of all identified AMR alleles, core gene mutations, and rRNA mutations, along with metadata such as product names and associated phenotypes [32]. Correlate these findings with the taxonomic profile and clinical data.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for detecting antimicrobial resistance using mNGS, from sample preparation to final analysis.

Diagram 1: mNGS AMR Analysis Workflow: This chart outlines the process from sample to AMR report, highlighting key stages including host DNA depletion and comprehensive bioinformatic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the aforementioned protocols requires a suite of reliable laboratory and computational resources. The following table details essential materials and their functions in mNGS-based AMR studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for mNGS-based AMR Analysis

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Processing | Total Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy/RNeasy) | Isolates high-quality, PCR-amplifiable DNA/RNA from complex clinical samples. |

| Host Depletion Kits (e.g., NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit) | Selectively removes human host DNA to increase microbial sequencing depth [31]. | |

| Library Prep & Sequencing | Library Preparation Kits (e.g., Illumina Nextera XT, ONT Ligation Kit) | Fragments nucleic acids and attaches platform-specific adapters for sequencing. |

| Sequencing Flow Cells (e.g., Illumina MiSeq, ONT MinION R9) | Solid-phase surface where clonal amplification and sequencing-by-synthesis occur. | |

| Bioinformatics & Databases | AmrProfiler Web Server | Open-access tool for comprehensive AMR gene, mutation, and rRNA analysis [32]. |

| CARD & ResFinder Databases | Curated reference databases of known AMR genes used for sequence alignment and annotation [32] [33]. | |

| RefSeq Genome Database | NCBI's comprehensive collection of reference genomes for mutation analysis and comparison [32]. |

The accurate interpretation of mNGS data for antimicrobial resistance research is fundamentally reliant on the synergistic use of advanced bioinformatics tools and meticulously curated reference databases. As the field progresses, the integration of these computational resources with standardized wet-lab protocols will be paramount for translating raw genomic data into clinically actionable information that can inform stewardship and drug development efforts.

From Sample to Insight: mNGS Workflows and Applications in AMR Research

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents a critical global health threat, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to nearly 5 million more [8]. Effectively combating this crisis requires robust surveillance strategies that can track the emergence and dissemination of resistance genes across human, animal, and environmental reservoirs—the core principle of the One Health approach [34] [35].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized AMR surveillance, moving beyond traditional, slower culture-based methods. Two powerful NGS methodologies are now at the forefront: shotgun metagenomics and targeted NGS (tNGS). Shotgun metagenomics provides a comprehensive, unbiased view of all genetic material in a sample, while tNGS uses enrichment techniques to focus sequencing power on specific genomic targets [36]. This application note details the strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases for each method to guide researchers in selecting the right tool for their AMR research objectives.

Shotgun Metagenomics (SMg)

Shotgun metagenomics involves sequencing all nucleic acids in a sample without prior targeting, allowing for the simultaneous detection of a vast array of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea) and their genes, including known and novel antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence factors [8] [34]. Its principal strength lies in its unbiased, hypothesis-free approach, making it ideal for pathogen discovery, characterizing complex microbial communities, and comprehensively profiling the "resistome" [34] [10].

Targeted NGS (tNGS)

Targeted NGS employs enrichment techniques to selectively sequence predefined genomic regions of interest before sequencing. The two primary tNGS approaches are:

- Amplification-based tNGS: Uses ultra-multiplex PCR with panels of primers to amplify specific target pathogens and ARGs [36].

- Capture-based tNGS: Uses solution-phase hybrid capture with probe panels to enrich for target sequences [36].

The key advantage of tNGS is its enhanced sensitivity for pre-specified targets, achieved by reducing host and non-target background DNA [37] [38].

Head-to-Head Comparison

The choice between shotgun metagenomics and tNGS involves balancing multiple factors, including scope, sensitivity, cost, and turnaround time. The table below summarizes their comparative performance based on recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Shotgun Metagenomics and Targeted NGS for AMR Surveillance

| Feature | Shotgun Metagenomics (SMg) | Targeted NGS (tNGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope & Bias | Unbiased, hypothesis-free; detects expected and novel pathogens/ARGs [34]. | Targeted, hypothesis-driven; limited to predefined pathogens/ARGs on the panel [37]. |

| Sensitivity | Lower sensitivity for low-abundance targets due to high background [36]. | Higher sensitivity for targeted pathogens/ARGs; superior for low-biomass samples [38] [36]. |

| Polymicrobial Infection Detection | Excellent; can characterize complex communities [10]. | Capture-based: Good. Amplification-based: Can struggle with mixed templates [36]. |

| Turnaround Time (TAT) | Longer (~20 hours reported) [36]. | Shorter than SMg; streamlined workflow [37]. |

| Cost | Higher (e.g., ~$840/sample reported) [36]. | Lower cost per sample [36]. |

| Ability to Detect Novel ARGs/Pathogens | Yes [8]. | No, limited to panel content. |

| Typing & Context | Enables strain-level typing, phylogenetic analysis, and ARG linkage to Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) [39] [40]. | Primarily for identification; limited contextual genomic information. |

| Ideal Use Case | Discovery, resistome profiling, One Health environmental screening, outbreak investigation of unknown origin [34] [10]. | Routine diagnostics, rapid results, confirming suspected pathogens, testing when resources are limited [38] [36]. |

A 2025 comparative study on lower respiratory infections quantitatively underscored these trade-offs. While SMg identified the most species (80), capture-based tNGS demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy (93.17%) and sensitivity (99.43%) against a comprehensive clinical standard. Amplification-based tNGS, though fast and cost-effective, showed poor sensitivity for gram-positive (40.23%) and gram-negative (71.74%) bacteria [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Shotgun Metagenomic Analysis of AMR

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating resistomes in human, animal, and environmental samples [10] and periprosthetic infections [39].

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (e.g., fecal, tissue, water, soil) in sterile containers. Immediately freeze at -80°C or preserve in RNAlater or glycerol buffer to maintain nucleic acid integrity [10].

- Homogenization: Mechanically homogenize samples using bead beating with vortex adapters to ensure efficient lysis of diverse microorganisms, particularly those in biofilms [39].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial kits designed for complex samples (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit). Include a step to remove host DNA using nucleases (e.g., Benzonase) to increase microbial sequencing depth [36] [10].

- Quality Control: Quantify DNA using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and assess quality/fragment size via agarose gel electrophoresis or Bioanalyzer [10].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Library Construction: Use Illumina Nextera XT or similar library prep kits for double-stranded DNA. For RNA virus detection, include a step for ribosomal RNA depletion and reverse transcription [36].

- Sequencing: Perform shotgun sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq). Aim for a minimum of 20 million high-quality reads per sample to ensure sufficient depth for detecting low-abundance ARGs [36] [39].

Bioinformatic Analysis for AMR Profiling:

- Quality Control and Host Depletion: Use Fastp to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads. Map reads to the host genome (e.g., hg38) using BWA and remove aligning reads [36].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Classify remaining reads using Kraken2/Bracken or MetaPhlAn against microbial genome databases [39] [10].

- ARG and MGE Detection: Align reads to AMR databases (e.g., NCBI's Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance Reference Gene Database, ResFinder, CARD) using tools like SRST2 or ABRicate. For MGEs (plasmids, integrons, transposons), use dedicated databases and tools [8] [39].

- Assembly and Contextual Analysis (Optional but Recommended): For complex analysis, assemble reads into contigs using metaSPAdes. Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using MaxBin. This allows for linking ARGs to their bacterial hosts and associated MGEs, providing insight into horizontal gene transfer potential [39] [40].

Protocol for Targeted NGS (tNGS) for AMR

This protocol is based on clinical studies using tNGS for pathogen identification and ARG detection in respiratory infections and periprosthetic joint infections (PJI) [38] [36].

Sample Processing and Targeted Enrichment: For Capture-based tNGS:

- DNA Extraction: Extract total nucleic acids from samples (e.g., BALF, sonicate fluid) using kits like MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [36].

- Library Preparation: Construct sequencing libraries from extracted DNA.

- Hybrid Capture: Incubate libraries with biotinylated probes designed to target specific genomic regions of pathogens and ARGs. Wash away non-hybridized DNA [36].

- Amplification: Amplify the captured target libraries via PCR.

For 16S rRNA Gene-based tNGS (for Bacterial ID):

- DNA Extraction: As above.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V1-V3, V3-V4) using broad-range primers [38].

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplicons.

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequencing: Sequence the enriched libraries on mid-output Illumina platforms (e.g., MiSeq, MiniSeq). Fewer reads are required compared to SMg (e.g., ~100,000 reads/sample) [38] [36].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples based on barcodes.

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality reads.

- Pathogen/ARG Identification: For capture-based tNGS, align reads to a curated database of pathogens and ARGs. For 16S tNGS, cluster high-quality sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and assign taxonomy using a reference database (e.g., SILVA) [38].

- Interpretation: Apply thresholds for positivity. For 16S tNGS, this may include a minimum read abundance (e.g., >10% of total reads) and verification that the species is not a known contaminant [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic AMR Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from complex matrices (stool, soil, sonicate fluid). | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit [36] [10]. |

| Host Depletion Reagents | Selective removal of human/host DNA to increase microbial sequencing depth. | Benzonase, Tween20 [36]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from fragmented DNA. | Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit, Ovation Ultralow System V2 [36]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Multiplex PCR or hybrid-capture panels for enriching pathogen and ARG sequences. | AmpliSeq for Illumina Antimicrobial Resistance Panel, Respiratory/Urinary Pathogen ID/AMR Enrichment Panels [41]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplification of conserved bacterial 16S rRNA gene regions for taxonomic profiling. | 515F/806R (targeting V3-V4 regions) [10]. |

| Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput sequencing of prepared libraries. | Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq; Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platforms [41] [40]. |

| Bioinformatic Databases | Reference databases for taxonomic assignment and ARG/MGE identification. | NCBI AMR Reference Gene Database, CARD, ResFinder, SILVA (16S rRNA) [38] [39]. |

Application within a One Health Framework

Genomic AMR surveillance is most effective when implemented within a One Health framework, integrating data from human, animal, and environmental sectors [34] [35]. Shotgun metagenomics and tNGS play complementary roles in this endeavor.

Shotgun metagenomics is exceptionally well-suited for initial environmental reconnaissance and resistome profiling. For instance, a 2025 study in Nepal used SMg on human and animal feces, soil, and water, identifying 53 ARG subtypes and demonstrating that poultry samples served as significant resistance reservoirs. This approach revealed frequent horizontal gene transfer events, highlighting the interconnectedness of resistomes across different ecosystems [10].

Targeted NGS finds its strength in focused surveillance and clinical diagnostics. Its high sensitivity is crucial for monitoring specific high-priority pathogens (e.g., WHO priority pathogens) and their associated resistance mechanisms in clinical or veterinary settings [34]. For example, tNGS showed a positive percent agreement of 72.1% for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection, significantly outperforming culture (52.9%) and proving invaluable in culture-negative cases [38].

The decision between shotgun metagenomics and targeted NGS is not a matter of choosing the universally superior technology, but rather the right tool for the specific research question and context.

- Choose Shotgun Metagenomics for exploratory studies, comprehensive resistome characterization, pathogen discovery, and when investigating the genetic context of ARGs (e.g., linkage to MGEs) is a priority [8] [39] [10].

- Choose Targeted NGS for routine surveillance of known pathogens, rapid clinical diagnostics, when sample input or pathogen biomass is low, and when cost and turnaround time are critical factors [38] [36].

Future advancements will see greater integration of these approaches, such as using SMg for broad surveillance to inform the design of more comprehensive tNGS panels. Furthermore, the adoption of long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) is overcoming historical limitations in metagenomics. These technologies enable more complete genome assemblies, precise plasmid reconstruction, and novel methods for linking ARG-carrying plasmids to their bacterial hosts through DNA methylation profiling, thereby providing a more holistic view of AMR transmission dynamics [40]. As these tools evolve and standardize, they will profoundly enhance our ability to conduct proactive, integrated AMR surveillance across the One Health spectrum.

Within metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) research on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the choice between whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis is a critical determinant of experimental success. This sample preparation decision significantly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and representativeness of detected pathogens and their resistance genes. wcDNA provides a comprehensive view of intact microorganisms, whereas cfDNA offers a snapshot of recently lysed cells and extracellular genetic material, each with distinct advantages for specific clinical and research scenarios. Framed within the broader objective of analyzing antimicrobial resistance genes, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate sample preparation methodology.

Performance Comparison: wcDNA vs. cfDNA

The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA extraction methods leads to significant differences in performance metrics, influenced by the sample type and the target pathogens. The following table summarizes key comparative data from recent clinical studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of wcDNA and cfDNA mNGS in Clinical Studies

| Study & Sample Type | Metric | wcDNA mNGS | cfDNA mNGS | Conventional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Infections (BALF) [42] | Detection Rate | 83.1% | 91.5% | 26.9% |

| Total Coincidence Rate | 63.9% | 73.8% | 30.8% | |

| CNS Infections (CSF) [43] | Sensitivity | 32.0% | 60.2% | 20.9% |

| Body Fluid Samples [44] | Concordance with Culture | 63.33% | 46.67% | (Benchmark) |

| Mean Host DNA Proportion | 84% | 95% | Not Applicable |

- Pathogen-Specific Efficiency: The superiority of cfDNA is particularly pronounced for certain pathogen types. In pulmonary infections, cfDNA detected a significantly higher proportion of fungi (31.8% vs 19.7% for wcDNA), viruses (38.6% vs 14.3%), and intracellular microbes (26.7% vs 6.7%) that would have been missed by the other method [42]. Similarly, for central nervous system (CNS) infections, most viral (72.6%) and mycobacterial (68.8%) pathogens were detected exclusively by cfDNA mNGS [43].

- Microbial Load Considerations: The advantage of cfDNA is most evident for pathogens with low microbial loads. For microbes with low reads per million (RPM), cfDNA detects a greater number and diversity of fungi, viruses, and intracellular organisms. In contrast, the ability of both methods to detect microbes with high loads is comparable [42].

- Host DNA Contamination: A critical technical consideration is the higher proportion of host DNA in cfDNA extracts from body fluids, averaging 95% compared to 84% in wcDNA extracts. This high background of host nucleic acids can potentially impact the sensitivity of pathogen detection by reducing the sequencing depth available for microbial reads [44].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and Preprocessing

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) / Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): Collect samples into sterile containers. Transport immediately on ice for processing [42] [43].

- Urine Samples: Centrifuge 1 mL of urine at 20,000 × g for 5 minutes. Discard 800 μL of supernatant and resuspend the pellet in the remaining 200 μL [45].

- Stool Samples: For gut microbiome analysis, standardize handling using a stool preprocessing device (SPD) prior to DNA extraction to improve yield, standardization, and recovery of Gram-positive bacteria [46].

DNA Extraction Protocols

A cfDNA Extraction Protocol

This protocol is adapted for BALF or CSF samples using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit [42] [43].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the BALF or CSF sample to remove cells and debris. Use the resulting supernatant for extraction.

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract DNA from the supernatant using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- DNA Quantification: Measure the concentration and quality of the extracted cfDNA using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit 4.0).

This gentle extraction avoids the DNA shearing associated with vigorous cell lysis, making it suitable for recovering fragmented cfDNA from pathogens.

B wcDNA Extraction Protocol

This protocol is for comprehensive lysis of all cells in a sample and is suitable for various body fluids [42] [43] [44].

- Direct Processing: Use the total BALF or CSF sample without preliminary centrifugation.

- Bead-Beating Lysis: Subject the sample to mechanical lysis using a bead-beating method with ceramic, glass, or zirconia beads to ensure rupture of tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria).

- DNA Purification: Extract and purify total DNA using a kit such as the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or the DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit.

- Alternative: Enzymatic Lysis: For long-read sequencing applications where DNA integrity is paramount, enzymatic lysis can be employed. Incubate the sample with a lytic enzyme solution (e.g., MetaPolyzyme) at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle shaking [45].

Library Construction and Sequencing

- Library Preparation: Construct DNA libraries using a low-input library preparation kit (e.g., QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit). For AMR-focused studies, hybrid capture-based enrichment with probes designed for microbial genomes and resistance genes can be employed [5].

- Quality Control: Assess library quality using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

- Sequencing: Sequence qualified libraries on a next-generation platform (e.g., Illumina Nextseq 550) to a depth of approximately 20 million reads per library [5].

Bioinformatic Analysis for AMR Gene Detection

- Preprocessing: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads from the raw sequencing data.

- Host Depletion: Map reads to the host reference genome (e.g., hg38) and subtract them to enrich for microbial sequences.

- Taxonomic Profiling: Align non-host reads to a comprehensive microbial genome database (e.g., NCBI) to identify pathogenic species.

- AMR Gene Identification: Detect known resistance genes by aligning sequences against curated AMR databases such as the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using tools like the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) [47].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel and distinct steps in wcDNA and cfDNA analysis.

Application in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Research

The accurate prediction of AMR phenotypes from mNGS data presents a significant challenge and opportunity. mNGS can simultaneously detect pathogenic species and their resistance-associated genes or mutations directly from clinical samples, providing a culture-independent diagnostic tool [5].

- Performance in Pediatric Pneumonia: A recent study on pediatric severe pneumonia demonstrated that mNGS has variable predictive performance for AMR, which is highly dependent on both the bacterial species and the class of antibiotic. For instance, the sensitivity of mNGS in predicting carbapenem resistance was relatively high (67.74%), particularly for Acinetobacter baumannii (94.74%). However, its sensitivity for predicting resistance to penicillins and cephalosporins was much lower (28.57% and 46.15%, respectively) [5].

- Complementary Role to Phenotypic Testing: These findings indicate that while mNGS shows promise as a rapid supplementary tool for AMR prediction, it currently cannot replace conventional phenotypic susceptibility testing (PST). The correlation between the presence of a resistance gene and the phenotypic expression of resistance is not always absolute, necessitating a combined approach for clinical decision-making [5].

- Benchmarking and Standardization: The development of gold-standard reference datasets, such as those comprising 174 bacterial genomes with known AMR profiles, is vital for benchmarking bioinformatic tools and pipelines used to predict AMR from both genomic and metagenomic sequencing data [47].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

Successful implementation of wcDNA and cfDNA protocols requires specific laboratory reagents and instruments. The following table lists key solutions for the core experimental procedures described in this document.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Vendor/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Micro Kit | DNA extraction from supernatant (cfDNA) or pellet (wcDNA). | QIAGEN |

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit | wcDNA extraction with robust bead-beating for difficult-to-lyse cells. | QIAGEN |

| MetaPolyzyme | Enzymatic lysis for gentle extraction of HMW DNA, suitable for long-read sequencing. | Sigma Aldrich |

| QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit | Library construction from low-concentration DNA extracts. | QIAGEN |

| IndiSpin Pathogen Kit | DNA extraction and purification, used in comparative method studies. | Indical Bioscience |

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit | Isolation of high molecular weight DNA for long-read sequencing. | Zymo Research |

| Benzonase | Enzymatic host nucleic acid depletion to enrich for microbial sequences. | Sigma |

| Nextseq 550 Platform | High-throughput sequencing of constructed libraries. | Illumina |

| MinION Device | Portable, real-time long-read sequencing. | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |