Debiasing the Lab: A Practical Guide to Mitigating Cognitive Bias in Materials Experimentation and Pharmaceutical R&D

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and addressing cognitive bias in experimental processes.

Debiasing the Lab: A Practical Guide to Mitigating Cognitive Bias in Materials Experimentation and Pharmaceutical R&D

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and addressing cognitive bias in experimental processes. Covering foundational concepts, practical mitigation methodologies, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and validation techniques, it synthesizes current research to offer actionable strategies. The guide aims to enhance R&D productivity, improve decision-making quality, and ultimately contribute to more robust and reliable scientific outcomes in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

The Unseen Variable: Understanding How Cognitive Bias Infiltrates Materials Science

Defining Cognitive Bias and Heuristics in Experimental Science

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between a cognitive bias and a heuristic? A heuristic is a mental shortcut or a "rule of thumb" that simplifies decision-making, often leading to efficient and fairly accurate outcomes [1]. A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, which is often a consequence of relying on heuristics [2] [3]. In essence, heuristics are the strategies we use to make decisions, while biases are the predictable gaps or errors that can result from those strategies [2].

Q2: Why are even experienced scientists susceptible to cognitive bias? Cognitive biases are a sign of a normally functioning brain and are not a reflection of intelligence or expertise [4]. The brain is hard-wired to use shortcuts to conserve mental energy and deal with uncertainty [5] [6]. Furthermore, the organization of scientific research can sometimes exacerbate these biases, for example, by making it difficult for scientists to change research topics, which reinforces loss aversion [4].

Q3: What are some common cognitive biases that specifically affect data interpretation? Several biases frequently skew data analysis:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek, interpret, and favor information that confirms one's existing beliefs or hypotheses [5] [3].

- Anchoring Bias: The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the "anchor") when making decisions [5].

- Survivorship Bias: The tendency to focus on the examples that "survived" a process and overlook those that did not, often leading to over-optimism [5].

- Automation Bias: The tendency to over-rely on automated systems or the first plausible AI-generated solution, which can cause one to stop searching for alternatives or dismiss contradictory information [7] [8].

Q4: Can training actually help reduce cognitive bias in research? Yes, evidence suggests that targeted training can be effective. One field study with graduate business students found that a single de-biasing training intervention could reduce biased decision-making by nearly one-third [9]. Awareness is the first step, and specific training can provide researchers with tools to recognize and counteract their own biased thinking.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Suspected Confirmation Bias in Experimental Design or Analysis

Symptoms:

- Dismissing or downplaying unexpected or contradictory data.

- Designing experiments or selecting data that can only validate a pre-existing hypothesis.

- Feeling threatened or defensive when a hypothesis is challenged.

Resolution Steps:

- Blind Analysis: Where possible, conduct analysis without knowing which sample belongs to which experimental group to prevent expectations from influencing results.

- Seek Disconfirmation: Actively design experiments or set aside resources to test your hypothesis by trying to disprove it, not just confirm it [4].

- Encourage Devil's Advocacy: In team meetings, assign a member to argue against the prevailing hypothesis to surface alternative interpretations [4].

- Pre-register Studies: Publicly document your hypotheses, experimental design, and analysis plan before conducting the research. This locks in your intent and prevents post-hoc reasoning.

Issue: Contextual Bias or Automation Bias in Pattern Recognition Tasks

Symptoms:

- In forensic science or image analysis, knowing extraneous information (e.g., a suspect's confession) influences the interpretation of physical evidence [8].

- Over-relying on the output or confidence score of an automated system (e.g., AI, AFIS, FRT) and ignoring one's own expert judgment or contradictory data [8].

Resolution Steps:

- Implement Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU): This procedure requires examiners to analyze the evidence in question before being exposed to any potentially biasing contextual information [8].

- Shuffle and Hide: When using automated systems that return a list of candidates, randomize the order of the list and hide the system's confidence scores before presenting them to the human examiner for interpretation [8].

- Independent Verification: Have a second, independent expert analyze the same data without exposure to the first examiner's conclusions or the biasing context.

Issue: Experimental Protocols Are Not Followed as Intended

Symptoms:

- Inconsistency between what the researcher intends for an experiment and what is actually carried out by students or technicians [10].

- Participants or staff misinterpret lab manual instructions, leading to inaccurate experiments.

Resolution Steps:

- Improve Manual Design: Develop manuals that consider both the causal conditions (the goal of the experiment) and the contextual conditions (the actual workspace and tools) to reduce the cognitive load and potential for biased interpretations [10].

- Use Visual Aids: Supplement written procedures with clear diagrams, flowcharts, and photographs to minimize ambiguity [10].

- Concurrent Verbal Protocol: During training or protocol validation, ask team members to "think aloud" as they follow the manual. This reveals their internal thought process and helps identify steps that are prone to biased interpretation [10].

Data Presentation: Common Cognitive Biases in Science

The table below summarizes key cognitive biases, their definitions, and a potential mitigation strategy relevant to experimental science [7] [5] [4].

| Bias | Definition | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmation Bias | Favoring information that confirms existing beliefs and ignoring contradictory evidence. | Actively seek alternative hypotheses and disconfirming evidence during experimental design [5]. |

| Anchoring Bias | Relying too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the "anchor"). | Establish analysis plans before collecting data. Consciously consider multiple initial hypotheses [5]. |

| Survivorship Bias | Concentrating on the examples that "passed a selection" while overlooking those that did not. | Actively account for and analyze failed experiments or dropped data points in your reporting [5]. |

| Automation Bias | Over-relying on automated systems, leading to the dismissal of contradictory information or cessation of search [7] [8]. | Use automated outputs as a guide, not a final answer. Implement independent verification steps [8]. |

| Loss Aversion / Sunk Cost Fallacy | The tendency to continue an investment based on cumulative prior investment (time, money) despite new evidence suggesting it's not optimal [7] [4]. | Create a research culture that rewards changing direction based on data, not just persisting on a single path [4]. |

| Social Reinforcement / Groupthink | The tendency to conform to the beliefs of a group, leading to a lack of critical evaluation. | Invite outside speakers to conferences and encourage internal criticism of dominant research paradigms [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol: "Blinded" Data Analysis to Mitigate Confirmation Bias

Objective: To prevent a researcher's expectations from influencing the collection, processing, or interpretation of data. Methodology:

- Sample Blinding: Ensure that all samples are coded in such a way that the analyst cannot identify which experimental group they belong to during data collection and initial processing.

- Automated Processing: Where feasible, use scripted, pre-defined algorithms for data processing to minimize manual intervention.

- Unblinding: Only after the initial analysis is complete and the results have been documented should the code be broken to assign groups for final interpretation. Key Consideration: This protocol is crucial in fields like pharmacology and materials testing where subjective measurement can be influenced by the desired outcome.

Protocol: Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU) to Mitigate Contextual Bias

Objective: To ensure that pattern comparison judgments (e.g., of forensic evidence, microscopy images) are made based solely on the physical evidence itself, without influence from extraneous contextual information [8]. Methodology:

- Initial Examination: The examiner first conducts a thorough analysis of the evidence in question (e.g., an unknown fingerprint, a microscopy image) in isolation.

- Documentation: The examiner documents their initial observations, findings, and conclusions.

- Controlled Information Reveal: Only after the initial examination is complete is the examiner provided with additional, context-setting information (e.g., the known sample for comparison, or other case information), and only in a managed, step-by-step fashion. Key Consideration: This protocol is directly applicable to any research involving comparative analysis, such as characterizing new material phases or comparing spectroscopic data.

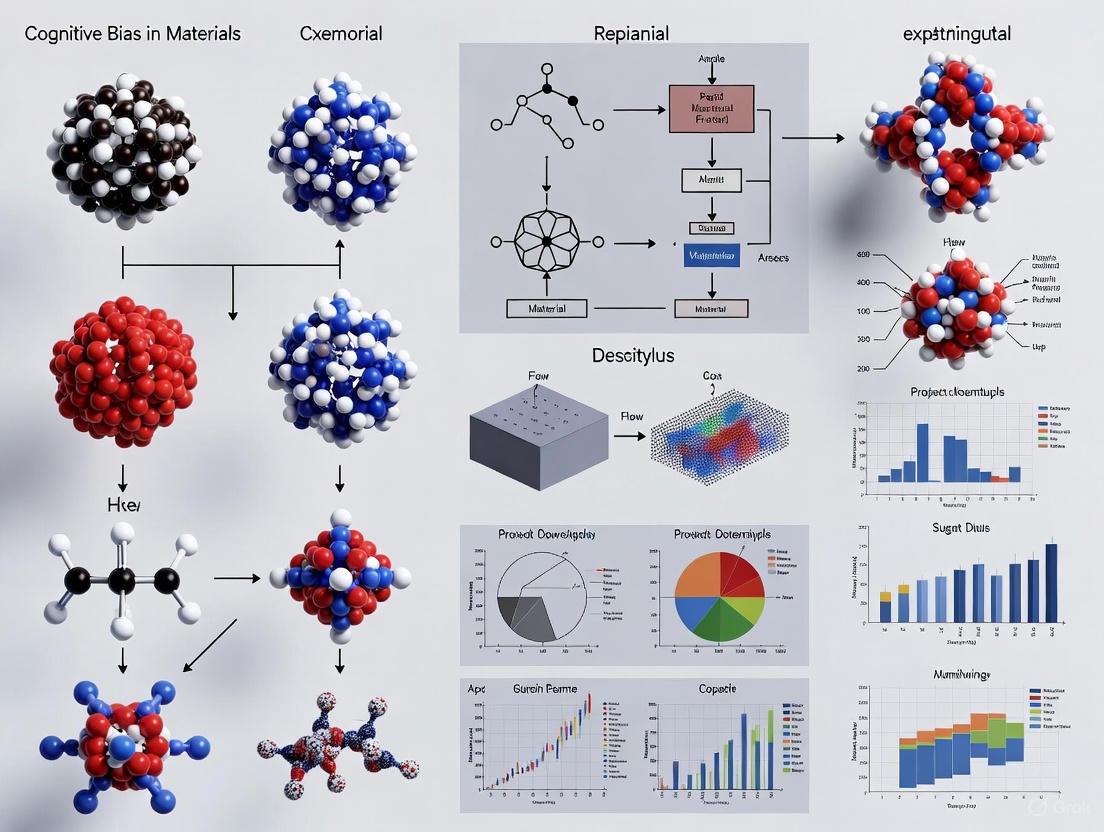

Visualization: Cognitive Bias in the Research Workflow

The following diagram maps where key cognitive biases most commonly intrude upon a generalized experimental research workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for a Bias-Aware Lab

This table details essential "reagents" for conducting rigorous, bias-aware research. These are conceptual tools and materials that should be standard in any experimental workflow.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pre-registration Template | A formal document template for detailing hypotheses, methods, and analysis plans before an experiment begins. This is a primary defense against confirmation bias and HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known). |

| Blinding Kits | Materials for anonymizing samples (e.g., coded containers, labels) to enable blinded data collection and analysis, mitigating observer bias. |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for LSU | A written protocol for Linear Sequential Unmasking to guard against contextual bias during comparative analyses [8]. |

| Devil's Advocate Checklist | A structured list of questions designed to challenge the dominant hypothesis and actively surface alternative explanations for predicted results [4]. |

| De-biasing Training Modules | Short, evidence-based training sessions to educate team members on recognizing and mitigating common cognitive biases [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identification and Mitigation

Confirmation Bias

Problem: A researcher selectively collects or interprets data in a way that confirms their pre-existing hypothesis about a new material's properties, leading to false positive results.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Are you giving more weight to data points that support your expected outcome?

- When analyzing results, do you actively look for disconfirming evidence or alternative explanations?

- Are you discounting anomalous data by attributing it to measurement error without rigorous investigation?

Solutions:

- Blinded Data Analysis: Implement protocols where the person analyzing the data is unaware of which samples belong to the experimental or control group [11].

- Pre-registration: Publicly document your research plan, including hypothesis and statistical analysis methods, before conducting the experiment [12].

- Consider-the-Opposite: Formally task yourself and your team with generating reasons why your primary hypothesis might be wrong [12] [13].

- Evidence Framework: Use standardized, structured formats to present all evidence, both supporting and conflicting, to avoid selective reporting [12].

Anchoring Bias

Problem: The initial value or early result in an experiment (e.g., the first few data points) exerts undue influence on all subsequent judgments and interpretations.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Are your estimates for unknown quantities clustering around an initial, potentially arbitrary value?

- Are you struggling to adjust your hypotheses sufficiently when new, contradictory data emerges?

- Is your evaluation of a supplier's or material's performance in one dimension affecting your objective assessment of its performance in other, unrelated dimensions [13]?

Solutions:

- Reference Case Forecasting: Before seeing results, establish a baseline forecast based on independent data or historical averages [12].

- Seek Independent Input: Consult with colleagues who were not involved in generating the initial estimate to get a fresh perspective [12].

- Mental Mapping: Use visual techniques to map out the entire decision process, which can help break the anchor's influence [13].

- Establish Quantitative Criteria: Prospectively set decision criteria and thresholds for success before data collection begins [12].

Sunk-Cost Fallacy

Problem: A researcher continues to invest time, resources, and effort into a failing research direction or experimental method because of the significant resources already invested, rather than because of its future potential.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Are you justifying continued investment in a project with phrases like "we've already come this far" or "we've spent too much to stop now"?

- Are you reluctant to terminate a project because it would mean admitting the past investment was wasted?

- Do you feel a sense of personal attachment or responsibility for the initial decision to pursue this path?

Solutions:

- Focus on Future Costs/Benefits: Consciously shift the decision framework to consider only future risks and rewards, ignoring irrecoverable investments [14] [15].

- Pre-Mortem Analysis: Imagine it is the future and your project has failed. Work backwards to write a history of that failure, identifying the reasons it might have occurred [12].

- Shift Perspective: Ask yourself: "If I were hired today to take over this project, with no prior investment, would I still continue to fund it?"

- Implement Structured Stopping Rules: Establish clear, quantitative go/no-go milestones for projects during the planning phase [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I'm a senior scientist. Are experienced researchers really susceptible to these biases? Yes. Expertise does not automatically confer immunity to cognitive biases. In fact, "champion bias" can occur, where the track record of a successful researcher leads others to overweight their opinions, neglecting the role of chance or other factors in their past successes [12]. Mitigation requires creating a culture of psychological safety where junior researchers feel empowered to question assumptions and decisions.

Q2: Our research is highly quantitative. Don't the data speak for themselves, making bias less of an issue? No. Biases can affect which data is collected, how it is measured, and how it is interpreted. Observer bias can influence the reading of instruments or subjective scoring [16] [11]. Furthermore, confirmation bias can lead to "p-hacking" or data dredging, where researchers run multiple statistical tests until they find a significant result [16]. Robust, pre-registered statistical plans are essential.

Q3: We use a collaborative team approach. Doesn't this eliminate individual biases? Team settings can mitigate some biases but also introduce others, such as "sunflower management" (the tendency for groups to align with the views of their leaders) [12]. Effective debiasing in teams requires structured processes, such as assigning a designated "devil's advocate" or using techniques like the "consider-the-opposite" strategy in group discussions [12] [13].

Q4: Can high cognitive ability prevent the sunk-cost fallacy? Research indicates that cognitive ability alone does not reliably alleviate the sunk-cost fallacy [15]. The bias is deeply rooted in motivation and emotion. This highlights the importance of using deliberate, structured decision-making processes and interventions (like the pre-mortem analysis) rather than relying on intelligence or willpower to overcome it.

Quantitative Data on Bias Impact and Mitigation

Documented Impact of Biases in Experimental Research

Table 1: Empirical Evidence of Bias Effects in Research

| Bias / Phenomenon | Research Context | Observed Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Blind Assessment | Life Sciences (Evolutionary Bio) | 27% larger effect sizes in non-blind vs. blind studies. | [11] |

| Observer Bias | Clinical Trials | Non-blind assessors reported a substantially more beneficial effect of interventions. | [11] |

| Anchoring Knock-on Effect | Supplier Evaluation | A low past-performance score in one dimension caused lower scores in other, unrelated dimensions. | [13] |

| Sunk-Cost Fallacy | Individual Decision-Making | The bias was statistically significant, and stronger with larger sunk costs. | [15] |

Efficacy of Debiasing Techniques

Table 2: Evidence for Debiasing Intervention Effectiveness

| Bias | Debiasing Technique | Evidence of Efficacy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchoring | Consider-the-Opposite | Effective at reducing the effects of high anchors in multi-dimensional judgments. | [13] |

| Anchoring | Mental-Mapping | Effective at reducing the effects of low anchors in multi-dimensional judgments. | [13] |

| Sunk-Cost | Focus on Thoughts & Feelings | An intervention prompting introspection on thoughts/feelings reduced sunk-cost bias more than a focus on improvement. | [14] |

| Multiple Biases | Prospective Quantitative Criteria | Setting decision criteria in advance mitigates anchoring, sunk-cost, and confirmation biases. | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol: Implementing a Blinded Analysis Workflow

Purpose: To prevent observer and confirmation bias during data collection and analysis. Materials: Coded samples, master list (held by third party), standard operating procedure (SOP) document.

- Sample Coding: Before analysis, have an independent lab member label all samples with a non-revealing code (e.g., A, B, C...). The master list linking codes to experimental groups is stored securely and separately.

- Blinded Phase: The researcher performing the experiments, measurements, and initial data processing works only with the coded samples. All data is recorded under the code IDs.

- Data Lock: Once all data collection is complete and the dataset is finalized, the analysis plan (pre-registered) is executed on the coded data.

- Unblinding: The master list is consulted to assign the correct group labels for the final interpretation and reporting of results [11].

Blinded Analysis Workflow

Protocol: Conducting a Pre-Mortem Analysis

Purpose: To proactively identify potential reasons for project failure, countering overconfidence and sunk-cost mentality. Materials: Team members, whiteboard or collaborative document.

- Brief the Team: Assume the project has failed spectacularly. The task is to generate reasons for this failure.

- Silent Generation: Give team members 5-10 minutes to independently write down all possible reasons for the failure, however unlikely.

- Round-Robin Sharing: Have each team member share one reason from their list, cycling until all ideas are captured.

- Discuss and Prioritize: Discuss the generated list and identify the 3-5 most credible threats.

- Develop Contingencies: For the top threats, brainstorm and document mitigation strategies or early warning signs [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Unbiased Research

Table 3: Key Resources for Mitigating Cognitive Bias

| Tool / Resource | Function in Bias Mitigation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Registration Template | Creates a time-stamped, unchangeable record of hypotheses and methods before experimentation; combats confirmation bias and HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known). | Use repositories like AsPredicted.org or OSF to document your experimental plan. |

| Blinding Kits | Allows for the physical separation of experimental groups; mitigates observer and performance bias. | Using identical, randomly numbered containers for control and test compounds in an animal study. |

| Structured Decision Forms | Embeds debiasing prompts (e.g., "List three alternative explanations") directly into the research workflow. | A form for reviewing data that requires the researcher to explicitly document disconfirming evidence. |

| Project "Tombstone" Archive | A repository of terminated projects with documented reasons for stopping; helps normalize project cessation and fights sunk-cost fallacy. | Reviewing the archive shows that terminating unproductive work is a standard, valued practice. |

| Independent Review Panels | Provides objective, external assessment free from internal attachments or champion bias. | A quarterly review of high-stakes projects by scientists from a different department. |

Clinical development is a high-risk endeavor, particularly Phase III trials, which represent the final and most costly stage of testing before a new therapy is submitted for regulatory approval. An analysis of 640 Phase III trials with novel therapeutics found that 54% failed in clinical development, with 57% of those failures (approximately 30% of all Phase III trials) due to an inability to demonstrate efficacy [17]. While a specific 90% failure rate is not directly documented in the provided research, the literature consistently highlights that the majority of late-stage failures can be attributed to various forms of bias that undermine the validity and reliability of trial results [12] [17]. This guide helps researchers identify and mitigate these biases.

FAQ: Key Questions on Bias in Clinical Research

Q1: What are the most common cognitive biases affecting drug development decisions? Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that can profoundly impact pharmaceutical R&D. Common ones include:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek, interpret, and favor information that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. For example, overweighting a positive Phase II trial and dismissing negative results as a "false negative" [12].

- Sunk-Cost Fallacy: The inclination to continue a project based on the historical investment of time and money, rather than its future probability of success [12].

- Anchoring and Optimism Bias: Rooting estimates to an initial, often optimistic, value and underestimating the likelihood of negative events, leading to unrealistic forecasts for Phase III outcomes [12] [17].

- Framing Bias: Making decisions based on how information is presented (e.g., emphasizing positive outcomes while downplaying side effects) rather than the underlying data [12].

Q2: How does publication bias affect the scientific record and clinical practice? Publication bias is the tendency to publish only statistically significant or "positive" results. This distorts the scientific literature, as "negative" trials—which show a treatment is ineffective or equivalent to standard care—often remain unpublished [18]. This can lead to:

- Inaccurate meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which form the basis for treatment guidelines.

- Repetition of failed research because other scientists are unaware of negative results.

- Ethical concerns as patients may be enrolled in trials for questions that have already been answered [19] [18].

Q3: What methodological biases threaten the internal validity of a clinical trial?

- Selection Bias: Occurs when the method of assigning participants to treatment or control groups produces systematic differences. This is conventionally mitigated by randomization [20].

- Performance Bias: Arises from systematic differences in the care provided to participants in different groups, aside from the intervention being studied. Blinding of participants and researchers is key to its prevention [16] [20].

- Detection Bias: Stems from systematic differences in how outcomes are assessed. This is also mitigated by blinding the outcome assessors [20].

- Attrition Bias: Happens when participants drop out of a study at different rates between groups, potentially skewing the results. An intention-to-treat analysis is a standard practice to help manage this [20] [21].

Q4: Why is diverse representation in clinical trials a bias mitigation strategy? A lack of diversity introduces selection bias and threatens the external validity of a trial. If a study population does not represent the demographics (e.g., sex, gender, race, ethnicity, age) of the real-world population who will use the drug, the results may not be generalizable [20]. This can lead to treatments that are less effective or have unknown side effects in underrepresented groups.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Bias

Use this guide to diagnose and address common bias-related problems in your research pipeline.

| Problem Symptom | Likely Type of Bias | Mitigation Strategies & Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Pipeline Progression: A project is continually advanced despite underwhelming or ambiguous data, often with the justification of past investment. | Sunk-Cost Fallacy [12] | Protocol: Implement prospective, quantitative decision criteria (e.g., Go/No-Go benchmarks) established before each development phase. Use pre-mortem exercises to imagine why a project might fail [12] [22]. |

| Trial Design & Planning: Overly optimistic predictions for Phase III success based on Phase II data; high screen failure rates; slow patient recruitment. | Anchoring, Optimism Bias, Selection Bias [12] [20] [17] | Protocol: Use reference case forecasting and input from independent experts to challenge assumptions. Review inclusion/exclusion criteria for unnecessary restrictiveness and perform a rigorous feasibility assessment before trial initiation [12] [17]. |

| Data Analysis & Interpretation: Focusing only on positive secondary endpoints when the primary endpoint fails; repeatedly analyzing data until a statistically significant (p<0.05) result is found. | Confirmation Bias, Reporting Bias, P-hacking [12] [18] [21] | Protocol: Pre-register the statistical analysis plan (SAP) before data collection begins. Commit to publishing all results, regardless of outcome. Use standardized evidence frameworks to present data objectively [12] [18]. |

| Publication & Dissemination: Only writing manuscripts for trials with "positive" results; a study is cited infrequently because its findings are null. | Publication Bias, Champion Bias [12] [19] | Protocol: Register all trials in a public repository (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov) at inception. Submit results to registries as required. Pursue journals and platforms dedicated to publishing null or negative results [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Unbiased Research

This table outlines essential "reagents" and tools for combating bias in your research process.

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Registration | To create a public, time-stamped record of a study's hypothesis, design, and analysis plan before data collection begins. | Combats HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known), p-hacking, and publication bias by locking in the research plan [18] [22]. |

| Randomization Software | To algorithmically assign participants to study groups, ensuring each has an equal chance of being in any group. | Mitigates selection bias, creating comparable groups and distributing confounding factors evenly [20] [22]. |

| Blinding/Masking Protocols | Procedures to prevent participants, care providers, and outcome assessors from knowing the assigned treatment. | Reduces performance bias and detection bias by preventing conscious or subconscious influence on the outcomes [16] [20]. |

| Standardized Reporting Guidelines (e.g., CONSORT) | Checklists and flow diagrams to ensure complete and transparent reporting of trial methods and results. | Fights reporting bias and spin by forcing a balanced and comprehensive account of the study [18]. |

| Independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) | A group of external experts who review interim trial data for safety and efficacy. | Helps mitigate conflicts of interest and confirmation bias within the sponsor's team by providing an objective assessment [19]. |

Visualizing Bias Mitigation: From Problem to Solution

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for integrating bias checks into the experimental lifecycle.

Decision Framework for Portfolio Management

This diagram outlines a debiased decision-making process for advancing or terminating a drug development project, specifically targeting the sunk-cost fallacy.

Foundational Concepts: Cognitive Bias in the Research Environment

What are cognitive biases and why should researchers care?

Cognitive biases are systematic deviations from normal, rational judgment that occur when people process information using heuristic, or mental shortcut, thinking [10]. In scientific research, these biases can significantly impact experimental outcomes by causing researchers to:

- Selectively focus on information that confirms existing beliefs

- Overlook contradictory data or evidence

- Make inconsistent judgments of the same evidence under different contexts

- misinterpret experimental results based on expectations rather than objective data

How do contextual and automation biases specifically affect experimental work?

Contextual bias occurs when extraneous information inappropriately influences professional judgment [8]. For example, knowing a sample came from a "high-risk" source might unconsciously influence how you interpret its experimental results.

Automation bias happens when researchers become over-reliant on instruments or software outputs, allowing technology to usurp rather than supplement their expert judgment [8]. This is particularly problematic when instruments provide confidence scores or ranked outputs that may contain inherent errors.

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Scenarios

Systematic Troubleshooting Framework

Effective troubleshooting requires a structured approach to overcome cognitive biases that might lead you to premature conclusions. Follow this six-step method adapted from laboratory best practices [23]:

Step 1: Identify the Problem Clearly define what went wrong without jumping to conclusions about causes. Example: "No PCR product detected on agarose gel, though DNA ladder is visible."

Step 2: List All Possible Explanations Brainstorm every potential cause, including obvious components and those that might escape initial attention. For PCR failure, this includes: Taq DNA Polymerase, MgCl₂, Buffer, dNTPs, primers, DNA template, equipment, and procedural steps [23].

Step 3: Collect Data Methodically

- Check controls: Determine if positive controls worked as expected

- Verify storage conditions: Confirm reagents haven't expired and were stored properly

- Review procedures: Compare your laboratory notebook with manufacturer's instructions and note any modifications

Step 4: Eliminate Explanations Based on collected data, systematically eliminate explanations you've ruled out. If positive controls worked and reagents were properly stored, you can eliminate the PCR kit as a cause [23].

Step 5: Check with Experimentation Design targeted experiments to test remaining explanations. For suspected DNA template issues, run gels to check for degradation and measure concentrations [23].

Step 6: Identify the Root Cause After eliminating most explanations, identify the remaining cause and implement solutions to prevent recurrence [23].

Troubleshooting Scenario: Failed Molecular Cloning

Table: Troubleshooting No Colonies on Agar Plates

| Problem Area | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Tests | Cognitive Bias Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competent Cells | Low efficiency, improper storage | Check positive control plate with uncut plasmid | Confirmation bias - overlooking cell quality due to excitement about experimental design |

| Antibiotic Selection | Wrong antibiotic, incorrect concentration | Verify antibiotic type and concentration match protocol | Automation bias - trusting lab stock solutions without verification |

| Procedure | Incorrect heat shock temperature | Confirm water bath at 42°C | Anchoring bias - relying on memory of previous settings rather than current measurement |

| Plasmid DNA | Low concentration, failed ligation | Gel electrophoresis, concentration measurement, sequencing | Contextual bias - assuming DNA is fine because previous preparations worked |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I recognize cognitive bias in my own experimental work?

Look for these warning signs:

- Selective data collection: Recording only results that match expectations

- Procedural drift: Gradually deviating from established protocols without documentation

- Confirmation tendencies: Designing experiments that can only confirm, not falsify, hypotheses

- Contextual influence: Changing interpretation of identical results based on different background information

What practical strategies can minimize bias in experimental design?

- Blinding: When possible, keep condition identities hidden during data collection and analysis

- Pre-registration: Document experimental plans and analysis methods before beginning work

- Systematic controls: Include appropriate positive, negative, and procedural controls in every experiment

- Independent verification: Have colleagues replicate key findings using the same protocols

- Comprehensive documentation: Record all results, including failed experiments and unexpected outcomes

The breadth-depth dilemma formalizes this trade-off. Research shows that with limited resources (less than 10 sampling opportunities), it's optimal to allocate resources broadly across many alternatives. With larger capacities, a sharp transition occurs toward deeply sampling a small fraction of alternatives, roughly following a square root sampling law where the optimal number of sampled alternatives grows with the square root of capacity [24].

What are effective decision-making strategies for research teams?

In consensus decision-making, studies show that groups often benefit from members willing to compromise rather than intractably insisting on preferences. Effective strategies include:

- Socially-minded approaches that consider group outcomes

- Simple heuristics that promote cooperation

- Clear communication of preferences without exaggeration

- Awareness that sophisticated cognition doesn't always guarantee better outcomes in group settings [25]

Visualizing Cognitive Bias in Experimental Workflows

Cognitive Bias Interference in Experimental Workflow: This diagram shows how different cognitive biases can interfere at various stages of the research process, potentially compromising experimental validity.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Molecular Biology

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Cognitive Bias Considerations | Quality Control Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification | Confirmation bias: assuming enzyme is always functional | Test with positive control template each use |

| Competent Cells | Host for plasmid transformation | Automation bias: trusting cell efficiency without verification | Always include uncut plasmid positive control |

| Restriction Enzymes | DNA cutting at specific sequences | Contextual bias: interpretation influenced by expected results | Verify activity with control DNA digest |

| Antibiotics | Selection pressure for transformed cells | Anchoring bias: using previous concentrations without verification | Confirm correct concentration for selection |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification | Automation bias: trusting kit performance implicitly | Include quality/quantity checks (Nanodrop, gel) |

Decision-Making Framework for Resource Allocation

Resource Allocation Decision Framework: This diagram illustrates the optimal strategy for allocating finite research resources based on sampling capacity, following principles of the breadth-depth dilemma [24].

By implementing these structured troubleshooting approaches, maintaining awareness of common cognitive biases, and following systematic decision-making frameworks, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and reproducibility of their experimental work while navigating the inherent tensions between efficient heuristics and comprehensive rational analysis.

In the pursuit of scientific truth, researchers in materials science and drug development navigate a complex landscape of data interpretation and experimental validation. The principle of epistemic humility—acknowledging the limits of our knowledge and methods—is not a weakness but a critical component of rigorous science. This technical support center addresses how cognitive biases systematically influence materials experimentation and provides practical frameworks for recognizing and mitigating these biases in your research.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, which can adversely affect scientific decision-making [26]. In high-stakes fields like drug development, where outcomes directly impact health and well-being, these biases can compromise research validity, lead to resource misallocation, and potentially affect public safety [27]. This guide provides troubleshooting approaches to help researchers identify and counter these biases through structured methodologies and critical self-assessment.

Understanding Cognitive Biases in Experimental Research

Common Research Biases and Their Impact

Cognitive biases manifest throughout the research process, from experimental design to data interpretation. The table below summarizes prevalent biases in experimental research, their manifestations, and potential consequences.

Table 1: Common Cognitive Biases in Experimental Research

| Bias Type | Definition | Common Manifestations in Research | Potential Impact on Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmation Bias [26] | Tendency to seek, interpret, and recall information that confirms pre-existing beliefs | - Selective data recording- Designing experiments that can only confirm hypotheses- Dismissing anomalous results | - Overestimation of effect sizes- Reproducibility failures- Missed discovery opportunities |

| Observer Bias [16] | Researchers' expectations influencing observations and interpretations | - Subjective measurement interpretation- Inconsistent application of measurement criteria- Selective attention to expected outcomes | - Measurement inaccuracies- Introduced subjectivity in objective measures- Compromised data reliability |

| Publication Bias [16] | Greater likelihood of publishing positive or statistically significant results | - File drawer problem (unpublished null results)- Selective reporting of successful experiments- Underrepresentation of negative findings | - Skewed literature- Inaccurate meta-analyses- Resource waste on false leads |

| Anchoring Bias [26] | Relying too heavily on initial information when making decisions | - Insufficient adjustment from preliminary data- Early results setting unrealistic expectations- Resistance to paradigm shifts despite new evidence | - Flawed experimental design parameters- Delayed recognition of significant findings- Inaccurate extrapolations |

| Recall Bias [16] | Inaccurate recollection of past events or experiences | - Selective memory of successful protocols- Incomplete lab notebook entries- Misremembered experimental conditions | - Protocol irreproducibility- Inaccurate methodological descriptions- Contaminated longitudinal data |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Bias in Experimental Workflows

Guide: Systematic Approach to Unexpected Experimental Results

Problem: You've obtained experimental results that contradict your hypothesis or established literature.

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology:

Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

Re-examine Raw Data and Experimental Conditions

- Verify instrument calibration and measurement techniques [28]

- Confirm positive and negative controls functioned as expected

- Check for environmental factors that may have influenced results (temperature, humidity, time of day)

- Action: Return to original data sources before any processing or transformation

Confirm Methodological Integrity

- Review protocol for any unintentional deviations [28]

- Verify reagent quality, concentrations, and storage conditions

- Confirm sample integrity and handling procedures

- Action: Repeat critical measurements using fresh preparations

Challenge Initial Assumptions and Consider Alternative Explanations

- Apply "consider the opposite" strategy by actively seeking disconfirming evidence [29]

- Generate multiple competing hypotheses that could explain the results

- Design a "crucial experiment" that can distinguish between alternative explanations

- Action: Discuss results with colleagues outside your immediate research group

Implement Blind Analysis Techniques

- Remove identifying labels from experimental groups during analysis [16]

- Use automated processing where possible to reduce subjective decisions

- Pre-register analysis plans before examining outcome data

- Action: Have a colleague independently analyze a subset of data

Document Comprehensive Findings Regardless of Outcome

- Report null results and unexpected findings with same rigor as positive results [27]

- Share methodological details that might help others avoid similar pitfalls

- Action: Maintain detailed lab notebooks with sufficient context for reproduction

Guide: Mitigating Observer Bias in Quantitative Measurements

Problem: Subjective judgment in data collection or analysis may be introducing systematic errors.

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology:

Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

Implement Blinding Procedures

- Code samples so experimenter cannot identify group assignments during measurement [16]

- Separate sample preparation from measurement tasks among different researchers

- Use third-party researchers for subjective assessments when possible

- Action: Develop a blinding protocol before beginning experiments

Standardize Measurement Protocols with Objective Criteria

- Define quantitative thresholds and decision rules before data collection [28]

- Use reference standards and controls in each experimental batch

- Establish clear categorical definitions with examples

- Action: Create a measurement protocol document with explicit criteria

Automate Data Collection Where Possible

- Use instrument-based measurements rather than visual assessments

- Implement image analysis algorithms for morphological assessments

- Utilize spectroscopic or chromatographic quantitative integrations

- Action: Validate automated methods against manual assessments

Establish Inter-rater Reliability

- Have multiple independent observers assess the same samples [16]

- Calculate statistical agreement (e.g., Cohen's kappa, intraclass correlation)

- Provide training until acceptable reliability is achieved

- Action: Include inter-rater reliability assessment in method validation

Validate with Control Experiments

- Include known positive and negative controls in each experiment

- Use "spiked" samples with known characteristics to test detection capability

- Perform recovery experiments to quantify measurement accuracy

- Action: Regularly test measurement systems with characterized controls

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Bias Identification and Awareness

Q: How can I recognize my own cognitive biases when I'm deeply invested in a research hypothesis?

A: This is a fundamental challenge in research. Effective strategies include:

- Pre-registration: Document your hypotheses, methods, and analysis plans before conducting experiments [27]. This creates a record of your initial expectations.

- Blind Analysis: Where possible, analyze data without knowing which group received which treatment [16].

- Devil's Advocate: Assign a team member to actively challenge interpretations and propose alternative explanations [29].

- Collaborative Critique: Regularly present raw data and preliminary findings to diverse colleagues outside your immediate project.

Q: Our team consistently interprets ambiguous data as supporting our main hypothesis. What structured approaches can break this pattern?

A: This pattern suggests strong confirmation bias. Implement these structured approaches:

- Alternative Hypothesis Testing: Systematically generate and test at least two competing explanations for each set of results [29].

- Results-Blinded Discussions: Discuss what various outcomes would mean for your hypotheses before unblinding results.

- Pre-mortem Analysis: Before finalizing conclusions, imagine your study failed and brainstorm possible reasons why [26].

- Quantitative Bias Assessments: Use statistical methods to estimate how strong an unmeasured bias would need to be to explain your results.

Methodological Considerations

Q: How can we design experiments that are inherently less susceptible to cognitive biases?

A: Several design strategies can reduce bias susceptibility:

- Double-Blind Designs: When possible, ensure both participants and experimenters are unaware of treatment assignments [16].

- Randomization: Implement proper randomization schemes rather than convenience sampling [27].

- Positive/Negative Controls: Include controls that should definitely work and definitely not work in each experiment.

- Methodological Triangulation: Use multiple different experimental approaches to address the same research question.

- Power Analysis: Conduct appropriate sample size calculations before experiments to avoid underpowered studies.

Q: What are the most effective ways to document and report failed experiments or null results?

A: Comprehensive documentation of all findings is crucial for scientific progress:

- Lab Notebook Standards: Maintain detailed records of all experiments regardless of outcome [28].

- Negative Results Repository: Consider depositing null result studies in specialized repositories.

- Methods Sections: Provide exhaustive methodological details even for unsuccessful approaches to help others.

- Alternative Formats: Explore brief communications, method papers, or data notes for valuable negative results.

- Internal Databases: Maintain institutional databases of attempted approaches and outcomes.

Systematic Approaches

Q: Are there structured frameworks for reviewing experimental designs for potential bias before beginning research?

A: Yes, implementing structured checkpoints significantly improves research quality:

- Experimental Design Review: Create a standardized checklist covering randomization, blinding, controls, and power analysis.

- Protocol Pre-registration: Register your study design, hypotheses, and analysis plan before data collection [27].

- Bias Assessment Tools: Adapt tools from evidence-based medicine (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool) for your field.

- External Consultation: Engage colleagues from different methodological backgrounds to review plans.

- Pilot Studies: Conduct small-scale pilot experiments specifically to identify methodological weaknesses.

Q: How can research groups create a culture that encourages identifying and discussing potential biases?

A: Cultural elements significantly impact bias mitigation:

- Psychological Safety: Foster an environment where questioning interpretations is welcomed, not punished [30].

- Regular Bias Discussions: Incorporate bias identification into lab meetings and journal clubs.

- Error Celebration: Acknowledge and learn from mistakes rather than hiding them.

- Diverse Perspectives: Include team members with different backgrounds and methodological training.

- Leadership Modeling: Senior researchers should openly discuss their own methodological uncertainties and past errors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Experimental Design

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Role in Bias Mitigation | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded Sample Coding System | Conceals group assignment during data collection | Prevents observer and confirmation biases by removing researcher expectations | Using third-party coding of treatment groups with revelation only after data collection |

| Pre-registration Platform | Documents hypotheses and methods before experimentation | Reduces HARKing (Hypothesizing After Results are Known) and selective reporting | Using repositories like AsPredicted or OSF to timestamp research plans before data collection |

| Automated Data Collection Instruments | Objective measurement without human intervention | Minimizes subjective judgment in data acquisition | Using plate readers, automated image analysis, or spectroscopic measurements rather than visual assessments |

| Positive/Negative Control Materials | Verification of experimental system performance | Detects systematic failures and validates method sensitivity | Including known active compounds and vehicle controls in each experimental batch |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and normalization standards | Ensures consistency across experiments and batches | Using certified reference materials for instrument calibration and quantitative comparisons |

| Electronic Lab Notebook with Version Control | Comprehensive experiment documentation | Creates immutable records of all attempts and results | Implementing ELNs that timestamp entries and prevent post-hoc modifications |

| Statistical Analysis Scripts | Transparent, reproducible data analysis | Preforms selective analysis and p-hacking | Using version-controlled scripts that document all analytical decisions |

| Data Visualization Templates | Standardized presentation of results | Prevents selective visualization that emphasizes desired patterns | Creating template graphs with consistent scales and representation of all data points |

Experimental Protocols for Bias-Resistant Research

Protocol: Double-Blind Experimental Design for Treatment Studies

Purpose: To minimize observer bias and confirmation bias in treatment-effect studies.

Materials:

- Test compounds and appropriate vehicle controls

- Coding system (numeric or alphanumeric)

- Independent third party for coding

- Sealed code envelope for emergency break

Methodology:

- Sample Size Calculation: Perform a priori power analysis to determine appropriate sample size [27].

- Randomization Scheme: Generate randomization sequence using computer-generated random numbers.

- Blinding Procedure:

- Provide all samples to independent third party for coding

- Maintain master list in secure, separate location

- Distribute coded samples to experimental researchers

- Experimental Execution:

- Conduct experiment using standardized protocols

- Record all data using code identifiers only

- Document any protocol deviations or unexpected events

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze data using code identifiers only

- Complete primary analysis before unblinding

- Document analytical decisions before unblinding

- Unblinding Procedure:

- Reveal group assignments only after completing analysis

- Document unblinding process and date

- Compare pre-unblinding and post-unblinding interpretations

Validation:

- Include positive and negative controls to verify system performance

- Assess blinding effectiveness by asking researchers to guess group assignments

- Document all steps for audit trail

Protocol: Pre-registration and Results-Blinded Analysis Workflow

Purpose: To prevent confirmation bias and selective reporting in data analysis.

Materials:

- Pre-registration platform (e.g., OSF, AsPredicted)

- Data management system

- Statistical analysis software

- Version control system

Methodology:

- Pre-registration Phase:

- Document primary research questions and hypotheses

- Specify primary and secondary outcome measures

- Define exclusion criteria and data handling procedures

- Outline planned statistical analyses

- Register protocol with timestamp before data collection

Data Collection Phase:

- Collect data according to pre-registered methods

- Implement quality control checks

- Document all data points, including outliers

- Maintain original, unprocessed data files

Analysis Phase:

- Begin with pre-registered analysis plan

- Conduct results-blinded exploration if needed

- Document all analytical decisions, including deviations from pre-registration

- Distinguish between confirmatory and exploratory analyses

Reporting Phase:

- Report all pre-registered analyses, regardless of outcome

- Clearly label exploratory analyses

- Share data and code when possible

- Discuss limitations and alternative explanations

Validation:

- Compare pre-registered and final analytical approaches

- Document reasons for any deviations from pre-registration

- Implement peer review of analytical code and decisions

The Debiasing Toolkit: Proven Methodologies for Bias-Resistant Research

FAQs on Cognitive Bias in Experimental Research

What are predefined success criteria and why are they critical in research?

Predefined success criteria are specific, measurable standards or benchmarks established before an experiment begins to objectively assess different outcomes and alternatives [31]. They are a fundamental guardrail against cognitive biases.

Using them ensures that all relevant aspects are considered, leading to more comprehensive and informed decisions [31]. More importantly, they provide a clear framework for evaluating data impartially, which helps prevent researchers from inadvertently cherry-picking results that confirm their expectations—a phenomenon known as confirmation bias [11] [32].

What is the connection between blinding and success criteria?

Success criteria define what to measure; blinding defines how to measure it without bias. Blinding is a key methodological protocol to ensure that success criteria are evaluated objectively.

Working "blind"—where the researcher is unaware of the identity or treatment group of each sample—is a powerful technique to minimize "experimenter effects" or "observer bias" [11]. This bias is strongest when researchers expect a particular result and can lead to exaggerated effect sizes. Studies have found that non-blind experiments tend to report higher effect sizes and more significant p-values than blind studies examining the same question [11].

What are common cognitive biases that affect materials experimentation?

Researchers are susceptible to several unconscious mental shortcuts, or heuristics, which can systematically skew data and interpretation [32].

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to search for, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses [11].

- Representativeness Heuristic: Judging that if one thing resembles another, they are likely connected, potentially overlooking more statistically relevant information [32].

- Availability Heuristic: Relying on the most immediate or easily recalled examples when evaluating a topic, rather than a comprehensive data set [32].

- Adjustment Heuristic: The failure to sufficiently adjust from an initial starting point or estimate, causing the starting point to overly influence the final conclusion [32].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Inconsistent or Non-Reproducible Results

Problem: Experimental outcomes vary unpredictably between trials or operators, making it difficult to draw reliable conclusions. Solution: A structured process to isolate variables and reduce subjectivity.

Step 1: Understand the Problem

- Ask Good Questions: Document every detail. What were the exact environmental conditions (temperature, humidity)? What was the precise batch of each reagent? What specific procedure did each operator follow?

- Gather Information: Review all raw data and lab notebooks. Compare the setup and process between successful and unsuccessful trials.

- Reproduce the Issue: Have a different researcher attempt to replicate the experiment using only the written protocol [33].

Step 2: Isolate the Issue

- Remove Complexity: Simplify the system to a known, baseline functioning state, then reintroduce variables one at a time [33].

- Change One Thing at a Time: Systematically vary one potential factor (e.g., reagent supplier, mixing speed, incubation time) while keeping all others constant to identify the root cause [33] [34].

- Compare to a Working Baseline: Directly compare materials and methods from a known, reproducible experiment against the current one to spot critical differences [33].

Step 3: Find a Fix or Workaround

- Test the Solution: Once a potential root cause is identified, run multiple controlled experiments to confirm that the change consistently resolves the issue.

- Document and Standardize: Update the official experimental protocol to incorporate the solution, preventing the issue for future researchers [33] [34].

Scenario 2: Data Analysis Yields Unexpected or Unfavorable Results

Problem: The collected data does not support the initial hypothesis, creating a temptation to re-analyze, exclude "outliers," or collect more data until a significant result is found (p-hacking). Solution: Rigid, pre-registered data analysis plans.

Step 1: Return to Predefined Criteria

- Re-examine Your Plan: Before collecting data, you should have defined your primary success metrics, statistical tests, and rules for handling outliers. Do not change these after seeing the results [31].

- Practice Active Listening: Apply the principle of "active listening" to your data. Let the data "speak" without interrupting it with your expectations. Avoid the tendency to explain away inconvenient data points [34].

Step 2: Apply Critical Thinking

- Break Down the Problem: Analyze the data objectively. Are the results truly negative, or do they suggest a different, interesting phenomenon?

- Consider Multiple Causes: Use logical reasoning to determine what the data actually implies, rather than what you hoped it would imply [34].

Step 3: Communicate with Integrity

- Show Empathy for the Scientific Process: Acknowledge that unexpected results are a normal part of science and can be just as valuable as confirmed hypotheses. Report your methods and findings transparently, including any "failed" experiments, to help the scientific community build an accurate body of knowledge [34].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Bias

Protocol 1: Implementing a Single-Blind Experimental Design

This protocol ensures the researcher collecting data is unaware of sample group identities to prevent subconscious influence on measurements.

Methodology:

- Sample Coding: An independent colleague not involved in the data collection should prepare and label all samples with a non-identifiable code (e.g., A, B, C... or 1, 2, 3...). This colleague maintains a master list linking codes to treatment groups.

- Randomization: The same colleague should randomize the order in which samples are processed and analyzed to avoid systematic errors.

- Blinded Analysis: The researcher performing the experiment and recording outcomes works only with the coded samples. The master list is not revealed until after all data collection and initial statistical analysis is complete.

- Revelation and Final Analysis: Once the data is locked, the code is broken, and the final group-wise analysis is performed.

Protocol 2: Pre-Registering Success Criteria and Analysis Plan

This protocol involves documenting your hypothesis, primary outcome measures, and statistical methods in a time-stamped document before beginning experimentation.

Methodology:

- Define Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Clearly state the main variable(s) that will answer your primary research question. List any exploratory outcomes separately.

- Specify Statistical Methods: Detail the exact statistical tests you will use, the alpha level for significance (e.g., p < 0.05), and how you will handle multiple comparisons.

- Establish Data Handling Rules: Pre-define rules for dealing with missing data, technical replicates, and the objective identification of outliers (e.g., using Grubbs' test or a pre-set threshold).

- Document and Submit: This plan can be registered in a dedicated repository (e.g., OSF) or simply documented in an internal, date-stamped lab notebook.

Visualizing the Bias-Resistant Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a structured decision-making workflow that integrates predefined criteria and blinding to minimize bias at key stages.

Structured Research Workflow

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Controlled Experimentation

The following table details essential materials and their functions in ensuring reproducible and unbiased experimental outcomes.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Mitigating Bias |

|---|---|

| Coded Sample Containers | Enables blinding by allowing samples to be identified by a neutral code (e.g., A1, B2) rather than treatment group, preventing measurement bias [11]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Provides a known baseline to compare against experimental results, helping to calibrate instruments and validate methods, thus reducing measurement drift and confirmation bias. |

| Pre-mixed Reagent Kits | Minimizes operator-to-operator variability in solution preparation, a key source of unintentional "experimenter effects" and irreproducible results [32]. |

| Automated Data Collection Systems | Reduces human intervention in data recording, minimizing errors and subconscious influences (observer bias) that can occur when manually recording measurements [11]. |

| Lab Information Management Systems (LIMS) | Enforces pre-registered experimental protocols and data handling rules, providing an audit trail and reducing "researcher degrees of freedom" after data collection begins [32]. |

Quantitative Impact of Blind Protocols on Research Outcomes

The table below summarizes empirical evidence on how the implementation of blind protocols affects research outcomes, demonstrating its importance as a success criterion.

| Study Focus | Finding on Effect Size (ES) | Finding on Statistical Significance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Sciences Literature | Non-blind studies reported higher effect sizes than blind studies of the same phenomenon. | Non-blind studies tended to report more significant p-values. | [11] |

| Matched Pairs Analysis | In 63% of pairs, the nonblind study had a higher effect size (median difference: 0.38). Lack of blinding was associated with a 27% increase in effect size. | Analysis confirmed blind studies had significantly smaller effect sizes (p = 0.032). | [11] |

| Clinical Trials Meta-Analysis | Past meta-analyses found a lack of blinding exaggerated measured benefits by 22% to 68%. | N/A | [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a pre-mortem, and how does it help our research team? A pre-mortem is a structured managerial strategy where a project team imagines that a future project has failed and then works backward to determine all the potential reasons that could have led to that failure [35]. It helps break groupthink, encourages open discussion about threats, and increases the likelihood of identifying major project risks before they occur [36] [35]. This process helps counteract cognitive biases like overconfidence and the planning fallacy [35].

How is a pre-mortem different from a standard risk assessment? Unlike a typical critiquing session where team members are asked what might go wrong, a pre-mortem operates on the assumption that the "patient" has already "died." [36] [35] This presumption of future failure liberates team members to voice concerns they might otherwise suppress, moving from a speculative to a diagnostic mindset.

When is the best time to conduct a pre-mortem? A pre-mortem is most effective during the all-important planning phase of a project, before significant resources have been committed [36].

A key team member seems overly optimistic about our experimental protocol. How can a pre-mortem help? Optimism bias is a well-documented cognitive bias that causes individuals to overestimate the probability of desirable outcomes and underestimate the likelihood of undesirable ones [37] [7]. The pre-mortem directly counters this by forcing the team to focus exclusively on potential failures, making it safe for dissenters to voice reservations about the project's weaknesses [36].

Our timelines are consistently too short. Can this technique address that? Yes. The planning fallacy, which is the tendency to underestimate the time it will take to complete a task, is a common source of project failure [37] [7]. By imagining a future where the project has failed due to a missed deadline, a pre-mortem can surface the true, underlying causes for potential delays.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

| Scenario | Implicated Cognitive Bias | Pre-Mortem Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently underestimating time and resources for experiments. | Planning Fallacy [37] [7] | Assume the experiment is months behind schedule. Brainstorm all possible causes: equipment delivery, protocol optimization, unexpected results requiring follow-up. |

| Dismissing anomalous data that contradicts the initial hypothesis. | Confirmation Bias [7] | Assume the hypothesis was proven completely wrong. Question why early warning signs (anomalous data) were ignored and implement blind analysis. |

| A new, complex assay is failing with no clear diagnosis. | Functional Fixedness [7] | Assume the assay never worked. Have team members with different expertise brainstorm failures from their unique perspectives to overcome fixedness. |

| Overreliance on a single piece of promising preliminary data. | Illusion of Validity [37] | Assume the key finding was non-reproducible. Identify all unverified assumptions and design controls to test them before scaling up. |

| A senior scientist's proposed method is followed without question. | Authority Bias [37] [7] | Assume the chosen methodology was fundamentally flawed. Anonymously list alternative methods that should have been considered. |

Cognitive Biases in Experimental Research

The following table summarizes key cognitive biases that the pre-mortem technique is designed to mitigate.

| Bias | Description | Impact on Materials Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Planning Fallacy [37] [7] | The tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions and overestimate the benefits. | Leads to unrealistic timelines for synthesis, characterization, and testing, causing project delays and budget overruns. |

| Optimism Bias [37] | The tendency to be over-optimistic about the outcome of plans and actions. | Can result in overlooking potential failure modes of a new material or chemical process, leading to wasted resources. |

| Confirmation Bias [7] | The tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms one's preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. | Researchers might selectively report data that supports their hypothesis while disregarding anomalous data that could be critical. |

| Authority Bias [37] [7] | The tendency to attribute greater accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure and be more influenced by that opinion. | Junior researchers may not challenge a flawed experimental design proposed by a senior team member, leading to collective error. |

| Illusion of Validity [37] | The tendency to overestimate one's ability to interpret and predict outcomes when analyzing consistent and inter-correlated data. | Overconfidence in early, promising data can lead to scaling up an experiment before it is properly validated. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Research Pre-Mortem

Objective: To proactively identify potential failures in a planned materials experimentation research project by assuming a future state of failure.

Materials & Preparation:

- Project plan or experimental design document.

- Writing materials or digital collaboration tool (whiteboard, shared document).

- Research team members (5-15 participants is ideal).

Methodology:

Preparation (10 mins): The project lead presents the finalized plan for the experiment or research project, ensuring all team members are familiar with the objectives, methods, and timeline.

Imagine the Failure (5 mins): The facilitator instructs the team: "Please imagine it is one year from today. Our project has failed completely and spectacularly. What went wrong?" [36] [35] Team members are given silent time to individually generate and write down all possible reasons for the failure.

Share Reasons (20-30 mins): The facilitator asks each participant, in turn, to share one reason from their list. This continues in a round-robin fashion until all potential failures have been documented where everyone can see them (e.g., on a whiteboard). This process ensures all voices are heard [36].

Open Discussion & Prioritization (20 mins): The team discusses the compiled list of potential failures. The goal is to identify the most significant and likely threats, not to debate whether a failure could happen.

Identify Mitigations (20 mins): For the top-priority threats identified, the team brainstorms and documents specific, actionable steps that can be incorporated into the project plan to either prevent the failure or mitigate its impact.

Review & Schedule Follow-up: The team agrees on the next steps for implementing the mitigations and schedules a follow-up meeting to review progress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Project Plan | A detailed document outlining the research question, hypothesis, experimental methods, controls, and timeline. Serves as the basis for the pre-mortem. |

| Pre-Mortem Facilitator | A neutral party (potentially rotated among team members) who guides the session, ensures psychological safety, and keeps the discussion productive. |

| Anonymous Submission Tool | A physical (e.g., notecards) or digital method for team members to submit initial failure ideas anonymously to reduce the influence of authority bias. |

| Risk Register | A living document, often a spreadsheet or table, used to track identified risks, their probability, impact, and the agreed-upon mitigation strategies. |

Pre-Mortem Workflow and Bias Mitigation

The following diagram illustrates the structured workflow of a pre-mortem and how each stage targets specific cognitive biases to improve project outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Blinding Failures and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Immediate Actions | Long-term Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unblinding of data analysts | Inadvertent disclosure in dataset labels; discussions with unblinded team members; interim analysis requiring unblinding [38] | Re-label datasets with non-identifying codes (A/B, X/Y); Document the incident and assess potential bias introduced [39] [38] | Implement a formal code-break procedure for emergencies only; Use independent statisticians for interim analyses [40] [39] |

| Inadequate allocation concealment | Non-robust randomization procedures; Assignments predictable from physical characteristics of materials [41] [42] | Have an independent biostatistician generate the allocation sequence; Verify concealment by attempting to predict assignments [41] | Use central randomization systems; Ensure test and control materials are physically identical in appearance, texture, and weight [42] [39] |

| Biased outcome assessment | Outcome measures are subjective; Data collectors are unblinded and have expectations [41] [43] | Use blinded outcome assessors independent of the research team; Validate outcome measures for objectivity and reliability [41] [43] | Automate data collection where possible; Use standardized, objective protocols for all measurements [43] [44] |

| Selective reporting of results | Data analyst is unblinded and influenced by confirmation bias, favoring a specific outcome [41] [45] | Pre-specify the statistical analysis plan before final database lock; Blind the data analyst until the analysis is complete [41] [38] | Register trial and analysis protocols in public databases; Report all outcomes, including negative findings [44] [45] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Implementing Blinding in Complex Scenarios

| Scenario | Blinding Challenge | Recommended Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical / Physical Intervention Trials | Impossible to blind the surgeon or practitioner performing the intervention [41] | Blind other individuals: Patients, postoperative care providers, data collectors, and outcome adjudicators can be blinded. Use large, identical dressings to conceal scars [41]. |

| Comparing Dissimilar Materials or Drugs | Test and control groups have different physical properties (e.g., color, viscosity, surface morphology) [42] [39] | Double-Dummy Design: Create two placebo controls, each matching one of the active interventions. Participants in each group receive one active and one placebo [42]. Over-encapsulation: Hide distinct materials within identical, opaque casings [42]. |

| Open-Label Trials (Blinding is impossible) | Participants and clinicians know the treatment assignment, creating high risk for performance and assessment bias [39] | Blind the outcome assessors and data analysts. Use objective, reliable primary outcomes. Standardize all other aspects of care and follow-up to minimize differential treatment [41] [39]. |

| Adaptive Trials with Interim Analyses | The study statistician must be unblinded for interim analysis, potentially introducing bias for the final analysis [38] | Independent Statistical Team: Employ a separate, unblinded statistician to perform interim analyses for the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The trial's lead statistician remains blinded until the final analysis [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core purpose of blinding data analysts in an experiment?

The core purpose is to prevent interpretation bias. When data analysts are unaware of group allocations, they cannot consciously or subconsciously influence the results. This includes preventing them from selectively choosing statistical tests, defining analysis populations, or interpreting patterns in a way that favors a pre-existing hypothesis (confirmation bias) [41] [40] [38]. Blinding ensures that the analysis is based on the data alone, not on the analysts' expectations.

Who else should be blinded in a trial besides the data analyst?

Blinding is not all-or-nothing; researchers should strive to blind as many individuals as possible. Key groups include:

- Participants: Prevents biased reporting of subjective outcomes and differential compliance [41].

- Clinicians/Researchers: Prevents differential administration of co-interventions or care [41] [43].

- Data Collectors: Ensures unbiased data recording and measurement [41].

- Outcome Adjudicators: Crucial for ensuring unbiased assessment of endpoints, especially those with any subjectivity [41] [43]. It is best practice to explicitly state who was blinded in the study report, rather than using ambiguous terms like "double-blind" [41] [40].

Our drug has a very distinct taste. How can we maintain blinding?

This is a common challenge in pharmacological trials. Simply using a "sugar pill" is insufficient. A robust approach involves:

- Placebo Matching: Develop a placebo that matches the active drug's sensory characteristics, including taste, smell, color, and viscosity. This may require adding flavor-masking agents or even reformulating the active drug itself to obscure its characteristics [42].