CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing: Principles, Clinical Applications, and 2025 Outlook for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing: Principles, Clinical Applications, and 2025 Outlook for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of RNA-guided DNA targeting, double-strand break repair pathways, and the evolution of CRISPR systems from bacterial immunity to therapeutic applications. The content covers current methodological approaches including ex vivo and in vivo editing strategies, base editing, and prime editing technologies, while addressing critical challenges such as off-target effects, delivery limitations, and immune responses. Finally, it examines the validation framework through clinical trial progress and the transformative impact of AI on CRISPR optimization, synthesizing key developments that are shaping the future of gene therapy and precision medicine.

The CRISPR-Cas9 Blueprint: From Bacterial Immunity to Programmable Genome Engineering

The discovery of the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system and its development into the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology represents one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the 21st century. This revolutionary technology originated from the study of a simple bacterial immune defense mechanism and has since transformed nearly every field of biological research, from basic science to therapeutic development [1] [2]. The journey from fundamental bacteriological research to a precise genome-editing tool exemplifies how curiosity-driven science can yield transformative technologies with far-reaching implications. This whitepaper traces the historical discovery of CRISPR-Cas9, details its molecular mechanisms, classifies its system variants, and explores its applications in biomedical research and drug development, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical resource on this groundbreaking technology.

Historical Timeline of Key Discoveries

The development of CRISPR-Cas9 from an obscure bacterial sequence to a revolutionary gene-editing tool spanned nearly three decades of international scientific effort. The table below chronicles the pivotal discoveries that enabled this transformation.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key CRISPR-Cas Discoveries

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers/Teams | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Identification of unusual repetitive sequences in E. coli | Yoshizumi Ishino et al. [3] | First accidental discovery of CRISPR sequences |

| 1993-2005 | Characterization of CRISPR loci and function | Francisco Mojica et al. [4] | Recognized CRISPR as a distinct family; hypothesized adaptive immune function |

| 2005 | Spacer sequences match bacteriophage DNA; PAM identification | Mojica et al.; Bolotin et al. [4] | Confirmed CRISPR as adaptive immune system; discovered PAM requirement |

| 2006 | Hypothetical scheme for CRISPR as bacterial immune system | Eugene Koonin et al. [4] | Computational prediction of CRISPR immune function |

| 2007 | Experimental demonstration of adaptive immunity | Philippe Horvath et al. [4] | Showed CRISPR integrates new phage DNA and provides resistance |

| 2008 | CRISPR spacers transcribed into guide RNAs | John van der Oost et al. [4] | Identified crRNAs that guide Cas proteins to targets |

| 2008 | CRISPR acts on DNA targets | Marraffini & Sontheimer [4] | Demonstrated DNA, not RNA, is the molecular target |

| 2010 | Cas9 cleaves target DNA | Sylvain Moineau et al. [4] | Showed Cas9 creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA |

| 2011 | Discovery of tracrRNA | Emmanuelle Charpentier et al. [4] | Identified tracrRNA essential for Cas9 system |

| 2011 | CRISPR functions heterologously in other species | Virginijus Siksnys et al. [4] | Demonstrated CRISPR works across species boundaries |

| 2012 | Biochemical characterization; single-guide RNA engineering | Siksnys et al.; Doudna & Charpentier [4] | Purified Cas9 complex; created simplified sgRNA system |

| 2013 | CRISPR adapted for genome editing in eukaryotic cells | Feng Zhang et al.; George Church et al. [4] | First demonstration of CRISPR editing in human and mouse cells |

The initial discovery phase began in 1987 when Japanese researcher Yoshizumi Ishino and colleagues accidentally cloned unusual repetitive sequences interspersed with spacer sequences while analyzing the iap gene in E. coli [3]. For years, these mysterious sequences remained biological curiosities without known function. Through the 1990s, researchers including Francisco Mojica documented similar structures across diverse bacteria and archaea, with Mojica ultimately proposing the acronym "CRISPR" in 2002 [4] [3]. The critical functional insight came in 2005 when Mojica and others recognized that spacer sequences matched viral DNA fragments, correctly hypothesizing that CRISPR constitutes an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes [4] [1].

The subsequent mechanistic elucidation phase revealed how this immune system operates. In 2008, van der Oost's team showed spacer sequences are transcribed into CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that guide Cas proteins [4], while Marraffini and Sontheimer demonstrated DNA targeting [4]. The pivotal Cas9 protein was identified by Bolotin in 2005 [4], with Moineau confirming its DNA cleavage function in 2010 [4]. Charpentier's discovery of tracrRNA in 2011 completed the understanding of the natural system [4]. The final technological transformation occurred when multiple groups recognized CRISPR's potential as a programmable gene-editing tool. In 2012, teams led by Siksnys and by Doudna and Charpentier independently reconstituted the CRISPR-Cas9 system in vitro, demonstrating programmable DNA cleavage [4] [1]. The field exploded in 2013 when Zhang and Church's labs simultaneously adapted CRISPR-Cas9 for efficient genome editing in eukaryotic cells [4], establishing the technology as a revolutionary tool for genetic engineering.

Molecular Mechanism and System Classification

The Natural CRISPR-Cas Immune System in Bacteria

In its natural context, the CRISPR-Cas system provides adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea through a three-stage process that protects against viral infections and plasmid transfer [5] [2]:

Adaptation (Spacer Acquisition): When a virus first infects a bacterium, the Cas1-Cas2 complex recognizes and cleaves foreign DNA into short fragments called protospacers. These fragments are then integrated as new spacers into the CRISPR array within the host genome, creating a molecular memory of the infection [5] [2].

Expression and Maturation: During subsequent infections, the CRISPR locus is transcribed as a long precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA). This pre-crRNA is processed into short, mature crRNAs, each containing a single spacer sequence that serves as a guide to recognize matching viral DNA [5].

Interference: The mature crRNAs assemble with Cas proteins to form effector complexes. When these complexes encounter nucleic acids matching the crRNA spacer sequence, they cleave and destroy the invading genetic material, thus providing immunity [5].

A critical component in self/non-self discrimination is the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short, specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target site in the viral genome. The PAM requirement ensures that the CRISPR system attacks only invading DNA while avoiding autoimmunity against the bacterial host's own CRISPR arrays [4] [5].

Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR-Cas systems exhibit remarkable diversity and are classified into two main classes based on their effector complex architecture [5]:

Table 2: Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Class | Types | Signature Protein | Effector Complex | Target | tracrRNA Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I, III, IV | Cas3 (Type I), Cas10 (Type III) | Multi-subunit complex | DNA (I, IV), DNA/RNA (III) | No |

| Class 2 | II, V, VI | Cas9 (Type II), Cas12 (Type V), Cas13 (Type VI) | Single protein | DNA (II, V), RNA (VI) | Yes (for most) |

Class 1 systems utilize multi-protein effector complexes and are found in both bacteria and archaea. Type I systems employ the Cascade complex for target recognition and Cas3 for DNA degradation. Type III systems target both RNA and DNA, while Type IV systems remain poorly characterized [5].

Class 2 systems utilize a single, large effector protein for interference and have been the primary focus for biotechnological applications due to their simplicity [5] [2]. Type II systems use Cas9, which requires both crRNA and tracrRNA for function and creates blunt-ended double-strand breaks in DNA. Type V systems employ Cas12 proteins, which process their own crRNAs and create staggered DNA breaks. Type VI systems utilize Cas13, which targets RNA rather than DNA [5].

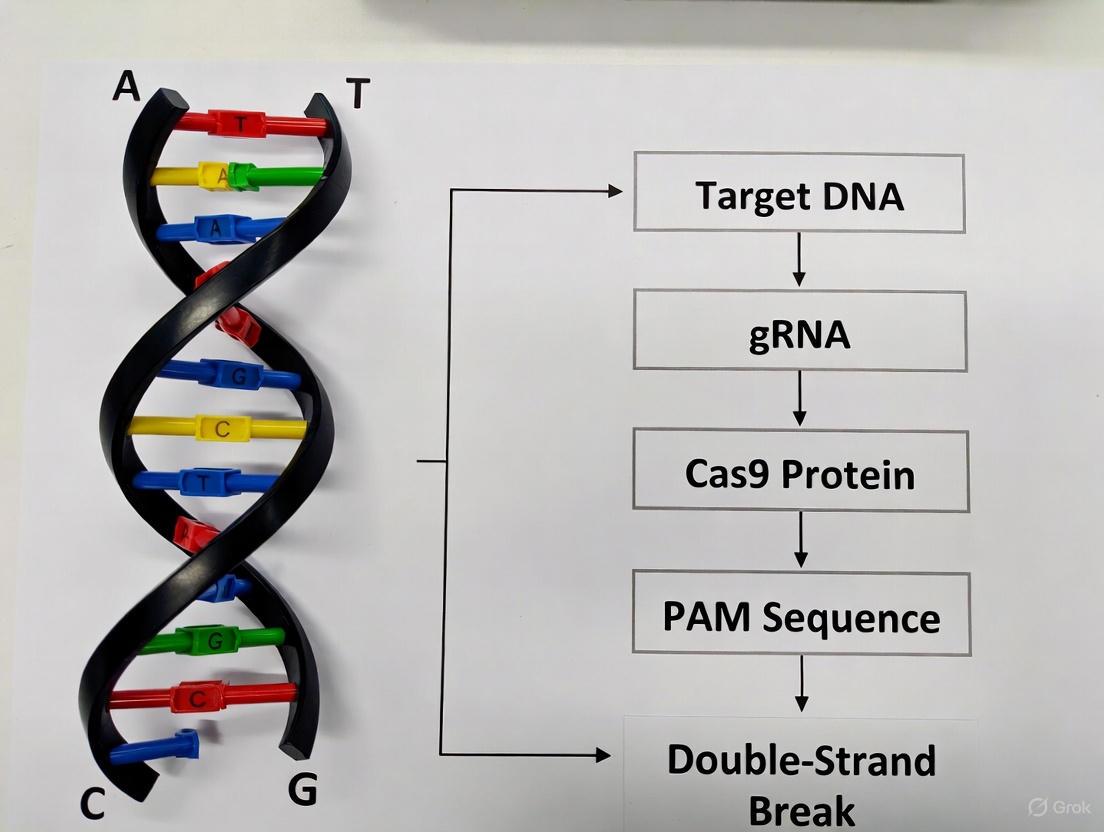

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanism of the Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system:

Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Editing

The transformation of CRISPR-Cas9 from a bacterial immune system to a versatile genome-editing tool required several key engineering advancements. Researchers simplified the natural two-RNA system (crRNA and tracrRNA) by creating a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) chimera, combining essential elements into one easily programmable molecule [4] [5]. The engineered system requires only two components: the Cas9 nuclease and the sgRNA, which can be programmed to target virtually any DNA sequence adjacent to a PAM [5].

When delivered into cells, the Cas9-sgRNA complex induces double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations. These breaks activate the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery, primarily through two pathways [5] [6]:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site, leading to gene knockouts.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a donor DNA template to introduce specific genetic modifications, such as point mutations or gene insertions.

The balance between these pathways varies by cell type, with NHEJ dominating in most mammalian cells and HDR occurring primarily in cycling cells [6].

Advanced CRISPR Tool Development and Technical Considerations

Engineered Cas9 Variants and Novel Editors

Beyond wild-type Cas9, researchers have developed numerous engineered variants with enhanced capabilities [5] [3]:

- High-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9-1.1) with reduced off-target effects through mutations that decrease non-specific DNA binding [3].

- Cas9 nickases that cut only one DNA strand, improving specificity when used in pairs [3].

- Dead Cas9 (dCas9) with inactivated catalytic domains, serving as a programmable DNA-binding platform for transcriptional regulation (CRISPRa/CRISPRi), epigenetic modification, or imaging [7] [3].

- Base editors that enable direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without creating DSBs, reducing indel formation [1].

- Prime editors that use a reverse transcriptase domain fused to Cas9 nickase to directly write new genetic information into target sites [1].

- Cas12 and Cas13 systems that target DNA and RNA respectively, expanding editing capabilities [5] [3].

Experimental Considerations and Controls

Robust experimental design is essential for successful CRISPR applications. Key considerations include:

- sgRNA Design: Careful selection of target sequences with minimal off-target potential and maximal on-target efficiency using validated algorithms.

- Delivery Methods: Choosing appropriate delivery systems (viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation) based on cell type and application [1] [8].

- Controls: Including multiple sgRNAs per target, non-targeting sgRNA controls, and Cas9-only controls to account for non-specific effects.

- Validation: Confirming edits through Sanger sequencing, next-generation sequencing, and functional assays.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | Wild-type SpCas9, High-fidelity variants, Base editors | Creates DSBs at target sites; specific editing functions | Choose based on PAM requirements, specificity needs, and desired edit type |

| Guide RNA Systems | sgRNA expression vectors, crRNA-tracrRNA complexes | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Optimize sgRNA sequence with minimal off-target potential |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors, Lentiviral vectors, Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Consider payload size, cell type compatibility, and toxicity |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA donors with homology arms | Enables precise HDR-mediated editing | Design with sufficient homology arms; optimize concentration |

| Detection & Validation | T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, NGS-based methods | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | Use multiple orthogonal validation methods |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing experiment:

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

CRISPR-Cas9 has demonstrated remarkable potential in therapeutic applications, with the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapy, Casgevy, approved for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia in 2024 [9]. Current clinical applications include:

Genetic Disorders

- Sickle Cell Disease and Beta Thalassemia: CRISPR-mediated disruption of the BCL11A gene to reactivate fetal hemoglobin production [9].

- Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR): Intellia Therapeutics' LNP-delivered CRISPR system targeting the TTR gene in the liver, showing ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels in clinical trials [9].

- Hereditary Angioedema (HAE): CRISPR-based reduction of kallikrein protein, with clinical trials showing 86% reduction in target protein and significant reduction in attacks [9].

Oncology Applications

- CAR-T Cell Engineering: CRISPR-mediated editing of T cells to enhance antitumor activity and overcome resistance [9] [6].

- Tumor Model Generation: Creating precise cellular and animal models for cancer research and drug screening [7] [6].

- Oncogene Disruption: Direct targeting of driver oncogenes in tumors, such as EGFRvIII in glioblastoma [6].

Infectious Diseases

- HIV Resistance: Engineering CCR5 knockout in T cells to confer HIV resistance [2].

- Antiviral Strategies: Targeting viral genomes, including HIV reservoirs and HPV [2].

- CRISPR-Enhanced Phage Therapy: Developing CRISPR-equipped bacteriophages to treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections [9].

The therapeutic landscape continues to expand, with ongoing clinical trials in areas including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and rare genetic conditions [9].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite rapid progress, several challenges remain in the broad application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology:

Technical Hurdles

- Off-target Effects: Unintended editing at similar genomic sequences remains a concern, though high-fidelity variants and improved sgRNA design have substantially mitigated this risk [2] [10].

- Delivery Efficiency: Achieving efficient, tissue-specific delivery in vivo continues to challenge clinical translation, with ongoing development of viral and non-viral delivery systems [1] [8].

- Editing Efficiency: HDR rates remain low in many therapeutically relevant cell types, particularly non-dividing cells [7].

- Immune Responses: Pre-existing immunity to bacterial Cas proteins may limit therapeutic efficacy in some patients [1].

Safety and Ethical Considerations

- Genomic Instability: Large deletions and chromosomal rearrangements have been reported at editing sites, requiring careful safety assessment [6].

- Germline Editing: Heritable genome modifications raise significant ethical concerns and are currently subject to moratoria in many countries [2].

- Regulatory Frameworks: Evolving regulations seek to balance innovation with appropriate oversight, particularly for genetically modified organisms and clinical applications [2].

Recent technological advances show promise in addressing these challenges. Novel anti-CRISPR proteins enable precise temporal control over editing activity, reducing off-target effects [10]. Advanced delivery systems, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), have demonstrated clinical success and enable redosing strategies [9]. The continued discovery of novel Cas proteins with diverse properties expands the targeting range and specificity of CRISPR systems [5] [3].

As the field progresses, CRISPR-Cas9 technology is poised to enable increasingly sophisticated applications in basic research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology. The ongoing refinement of editing precision, delivery efficiency, and safety profiles will further establish this revolutionary technology as an indispensable tool for biological research and medical innovation.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development since its discovery, providing an unprecedented ability to perform precise genome editing [11]. This technology originates from a adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea that protects against invading viruses and foreign genetic material [12] [13]. The core molecular machinery of this system consists of three essential components: a guide RNA (gRNA) that provides targeting specificity, a CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease that executes DNA cleavage, and a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) that enables self versus non-self discrimination [14] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise structure, function, and interplay of these three components is fundamental to designing effective experiments and developing safe therapeutic applications. This technical guide examines each component in detail, providing the foundational knowledge required for advanced CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing research.

The Guide RNA (gRNA): Molecular Address System

The guide RNA serves as the targeting module of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, directing the Cas nuclease to specific genomic locations with precision. This synthetic RNA molecule combines two natural RNA components—the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) containing the target-specific spacer sequence, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) that serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [15]. In engineered systems, these are often combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplicity [15] [16].

Structural Components and Design Principles

The gRNA contains two critical functional regions:

- Spacer Sequence: A user-defined 17-20 nucleotide sequence that determines targeting specificity through complementary base pairing with the target DNA [16]

- Scaffold Sequence: A structural component that binds to the Cas nuclease and facilitates the conformational changes required for activation [16]

The targeting specificity of the gRNA follows well-established rules. The seed sequence (8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) is particularly critical for initial DNA interrogation and binding [16]. Mismatches between the gRNA and target DNA in this seed region typically inhibit target cleavage, while mismatches toward the 5' end distal to the PAM are often tolerated [16].

Experimental Considerations for gRNA Design

Successful genome editing experiments require careful gRNA selection with attention to:

- Target Uniqueness: The 20-nucleotide spacer sequence must be unique compared to the rest of the genome to minimize off-target effects [16]

- Genomic Context: Accessibility of the target site within chromatin structure can significantly impact editing efficiency

- Minimizing Off-Target Effects: Bioinformatic tools are essential for predicting potential off-target sites with similar sequences [11]

Advanced applications utilize modified gRNA designs, including truncated gRNAs with shorter spacers to enhance specificity, and engineered mismatches in the PAM-distal region to promote faster Cas9 turnover after cleavage [17].

The Cas Nuclease: Molecular Scissor

The CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease functions as the effector module that creates double-strand breaks in target DNA. The most widely used nuclease is Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), though numerous alternatives with distinct properties have been characterized and engineered for specialized applications [12] [16].

Structural Domains and Cleavage Mechanism

Cas nucleases exhibit a conserved bilobed architecture consisting of:

- REC Lobe (Recognition Lobe): Primarily responsible for binding the gRNA and facilitating target recognition [15]

- NUC Lobe (Nuclease Lobe): Contains the catalytic domains responsible for DNA cleavage [15]

Within the NUC lobe, two nuclease domains execute DNA cleavage:

- HNH Domain: Cleaves the target DNA strand complementary to the gRNA spacer sequence [15]

- RuvC Domain: Cleaves the non-target DNA strand [15]

These domains work coordinately to create a double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [16]. The cleavage mechanism generates blunt ends for Cas9, while other nucleases like Cas12a create staggered ends with 5' overhangs [12].

Cas Nuclease Engineering and Variants

The limitations of wild-type SpCas9 have prompted extensive engineering efforts to improve its properties:

Table 1: Engineered Cas9 Variants with Enhanced Properties

| Variant Name | Key Modifications | Functional Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) | Weakened interactions with non-target DNA strand | Reduced off-target effects |

| SpCas9-HF1 | Disrupted Cas9-DNA phosphate backbone interactions | Enhanced specificity |

| HypaCas9 | Increased proofreading capability | Improved mismatch discrimination |

| evoCas9 | Multiple domain mutations | Decreased off-target effects |

| xCas9 3.7 | Mutations in multiple domains | Expanded PAM recognition (NG, GAA, GAT) and increased specificity |

| Sniper-Cas9 | Not specified | Reduced off-target activity; compatible with truncated gRNAs |

| SuperFi-Cas9 | Not specified | Increased fidelity with reduced nuclease activity |

Additional Cas orthologs beyond SpCas9 offer natural alternatives with distinct properties:

Table 2: Naturally Occurring Cas Nuclease Variants

| Nuclease | Source Organism | PAM Sequence | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN | Smaller size for viral delivery |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT | Enhanced specificity |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC | Compact size |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV | Creates staggered cuts; simpler gRNA |

| Cas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN | Thermostable variant available |

| Cas9d | Deltaproteobacteria | NGG | Compact size (747 aa); suitable for AAV delivery |

Recent structural studies of the compact Cas9d system have revealed a novel RNA-coordinated target Engagement Module (REM), where a segment of the sgRNA scaffold interacts with the REC domain to form a functional hybrid module that precisely monitors heteroduplex complementarity, resulting in lower mismatch tolerance compared to SpyCas9 [15].

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): Self vs. Non-Self Discriminator

The protospacer adjacent motif is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that follows immediately downstream of the target DNA region recognized by the gRNA [14] [12]. This sequence is absolutely required for Cas nuclease activity and serves as the primary mechanism for distinguishing between self and non-self DNA in bacterial immunity.

Biological Function and Recognition Mechanism

In native bacterial CRISPR systems, the PAM prevents autoimmunity by ensuring that Cas nucleases only target foreign DNA. While the bacterial CRISPR array contains spacer sequences derived from viruses, these sequences lack the adjacent PAM sequence, protecting the host genome from cleavage [12] [13]. The PAM recognition mechanism involves specific domains within the Cas nuclease. For SpCas9, the PAM-interacting (PI) domain recognizes the NGG motif, while in Cas9d, both the WED and PI domains collaborate in PAM recognition [15].

Structural analyses have revealed that key residues (Asn651, Lys649, and Lys715 in Cas9d) form specific hydrogen bonds with the PAM sequence, with alanine substitution of these residues abolishing or reducing target cleavage [15]. Upon PAM binding, the Cas nuclease undergoes conformational changes that destabilize the adjacent DNA duplex, enabling interrogation of sequence complementarity between the gRNA and target DNA [14].

PAM Requirements Across Cas Variants

Different Cas nucleases recognize distinct PAM sequences, which constrains their targeting ranges:

Table 3: PAM Sequences for Various CRISPR Nucleases

| CRISPR Nucleases | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNGRRN |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| StCas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | NNAGAAW |

| LbCpf1 (Cas12a) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AsCpf1 (Cas12a) | Acidaminococcus sp. | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| BhCas12b v4 | Bacillus hisashii | ATTN, TTTN and GTTN |

| Cas14 | Uncultivated archaea | T-rich PAM sequences for dsDNA cleavage |

| Cas3 | Various prokaryotic genomes | No PAM requirement |

The requirement for specific PAM sequences initially limited the targeting range of CRISPR systems, inspiring engineering efforts to develop variants with altered PAM specificities. Notable achievements include SpCas9-NG (recognizes NG PAMs), SpG (recognizes NGN PAMs), and SpRY (recognizes NRN and NYN PAMs, approaching PAM-less editing) [16].

Integrated Molecular Mechanism

The functional integration of the gRNA, Cas nuclease, and PAM recognition creates a highly specific genome editing system. The coordinated mechanism proceeds through distinct stages:

PAM Recognition and Complex Activation: The Cas nuclease scans DNA for appropriate PAM sequences, with recognition triggering conformational changes that activate the complex [14] [13]

DNA Melting and Seed Binding: PAM binding induces local DNA melting, allowing the seed region of the gRNA to interrogate potential complementarity [13] [16]

R-loop Propagation and Conformational Changes: If seed pairing is successful, the RNA-DNA heteroduplex extends, inducing structural rearrangements in the REC lobe and activating the nuclease domains [17]

Target Cleavage and Product Release: The HNH and RuvC domains create coordinated breaks in both DNA strands, after which the complex may remain bound until displaced by cellular machinery [17]

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Target Recognition and Cleavage Mechanism

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vitro Cleavage Assay

A fundamental experiment for characterizing CRISPR-Cas9 activity involves in vitro cleavage assays:

Protocol:

- Reconstitute RNP Complex: Incubate purified Cas nuclease (1-5 μM) with synthesized gRNA (1.2-2× molar ratio) in reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5) for 10-15 minutes at 25°C

- Add DNA Substrate: Introduce target DNA (100-500 nM) containing the appropriate PAM sequence

- Initiate Reaction: Incubate at 37°C for predetermined time points (15 minutes to several hours)

- Terminate Reaction: Add STOP buffer (10 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS)

- Analyze Products: Separate cleavage products using agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with appropriate DNA staining

Applications: This assay determines cleavage efficiency, kinetics, and specificity under controlled conditions, and can be adapted for high-throughput screening of gRNA efficacy or PAM specificity [18] [17].

PAM Identification Assays

Determining the PAM specificity of novel Cas nucleases requires specialized approaches:

PAM Depletion/Screening Assay:

- Library Construction: Create a plasmid library with randomized DNA sequences adjacent to a fixed target site

- Transformation: Introduce the library into bacterial cells expressing the functional CRISPR-Cas system

- Selection: Allow the system to cleave plasmids with functional PAM sequences

- Sequencing Analysis: Recover surviving plasmids and sequence the PAM region to identify depleted (functional) PAM sequences [13]

Alternative Method - PAM-SCANR: This high-throughput in vivo method uses a catalytically dead Cas variant (dCas9) coupled with a GFP reporter system. Functional PAM binding represses GFP expression, enabling FACS sorting and sequencing to identify all functional PAM motifs [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Examples / Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vectors | Delivery of Cas nuclease to cells | Addgene: #41815 (SpCas9), #42229 (SaCas9) |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | Expression of single or multiple gRNAs | Addgene: #41824, #52961, #67978 |

| Cas9 Nickase Variants | Increased specificity through paired nicking | Addgene: #41816 (D10A mutant) |

| High-Fidelity Cas9s | Reduced off-target effects | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 |

| PAM-Flexible Variants | Expanded targeting range | xCas9, SpCas9-NG, SpRY |

| Anti-CRISPR Proteins | Inhibition of Cas9 activity after editing | LFN-Acr/PA system for rapid Cas9 inhibition |

| Bioinformatics Tools | gRNA design and off-target prediction | CHOPCHOP, CRISPResso, Cas-OFFinder |

Recent advances in reagent development include the LFN-Acr/PA system, a cell-permeable anti-CRISPR protein system that rapidly shuts down Cas9 activity after genome editing is complete, reducing off-target effects and improving clinical safety [19]. This system uses a component derived from anthrax toxin to introduce anti-CRISPR proteins into human cells within minutes, boosting genome-editing specificity by up to 40% [19].

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Experimental Workflow

The core molecular components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system—the guide RNA, Cas nuclease, and PAM sequence—function as an integrated molecular machine that enables precise genome editing. The continuing evolution of these components through protein engineering and synthetic biology approaches is expanding the capabilities and applications of this transformative technology. For research and therapeutic development, understanding the fundamental principles governing these components and their interactions provides the foundation for designing effective experiments and developing safe genetic therapies. As the field advances, the ongoing characterization of novel Cas nucleases, refinement of gRNA design principles, and engineering of PAM specificity will further enhance the precision and utility of CRISPR-based genome editing.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a paradigm shift in genome engineering, offering an unprecedented ability to perform targeted modifications within complex genomes. Its core function hinges on a fundamental biological event: the creation of a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in DNA. This controlled DNA damage is the catalyst that enables all subsequent genome editing outcomes, from gene knockouts to precise corrections. For research and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of this cutting mechanism is not merely academic; it is essential for designing effective experiments, interpreting results, and developing safe therapeutic interventions. This guide details the molecular actors, the step-by-step mechanism of DNA cleavage, and the critical experimental methodologies used to study and harness this powerful process.

Molecular Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The CRISPR-Cas9 system's precision stems from its two essential components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). These elements work in concert to locate and cleave a specific DNA sequence.

- The Cas9 Nuclease: Cas9 is a multi-domain DNA endonuclease. Structurally, it comprises two primary lobes: the recognition (REC) lobe, which is responsible for binding the gRNA, and the nuclease (NUC) lobe [20] [21]. The NUC lobe contains two independent catalytic domains and a PAM-interaction domain:

- HNH Domain: Cleaves the DNA strand that is complementary to the gRNA (the target strand) [20] [21].

- RuvC Domain: Cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand (the non-target strand) [20] [21].

- PAM-Interacting Domain: Essential for initiating the binding to the target DNA by recognizing a short, adjacent sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [20] [21].

- The Guide RNA (gRNA): The gRNA is a synthetic chimeric RNA that combines the functions of two natural RNAs: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [20] [22]. The 5' end of the gRNA contains a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA, dictating the system's specificity. The 3' end forms a hairpin structure that serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 protein [20] [21].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 Cutting Machinery

| Component | Type | Key Function in DNA Cutting |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Protein (Multidomain Enzyme) | Executes the double-stranded DNA break via its HNH and RuvC nuclease domains [20] [21]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | RNA Molecule | Provides sequence specificity by binding to complementary target DNA via its spacer sequence; also activates Cas9 [20] [21]. |

| Spacer Sequence | 18-20 nt region of gRNA | Determines the target genomic locus through Watson-Crick base pairing [20]. |

| Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | Short DNA sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3') | A mandatory recognition site adjacent to the target sequence; enables Cas9 to initiate DNA binding [20] [21] [22]. |

The Step-by-Step Mechanism of DNA Cleavage

The process of DNA cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 is a coordinated, multi-stage mechanism that ensures high fidelity and specificity.

- Complex Assembly: The Cas9 nuclease binds to the gRNA to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. This association induces a conformational change in Cas9, activating it for DNA surveillance [21].

- PAM Recognition and DNA Binding: The Cas9-gRNA complex scans the DNA. The PAM-interacting domain checks for the presence of a correct PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for the common S. pyogenes Cas9) [21] [22]. PAM recognition is a critical first step that triggers local DNA melting, unwinding the double helix adjacent to the PAM [21].

- Target Verification and R-Loop Formation: If a PAM is found, the "seed sequence" near the PAM initiates hybridization with the gRNA. If the DNA sequence is fully complementary to the gRNA spacer, the RNA-DNA hybrid extends, displacing the non-complementary DNA strand and forming a structure known as an R-loop [21].

- Conformational Activation and Double-Strand Break: Successful R-loop formation induces a final conformational change in Cas9, positioning the nuclease domains for cleavage. The HNH domain cleaves the target strand (the one hybridized to the gRNA), and the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target strand [20] [21]. This coordinated action typically results in a blunt-ended double-strand break 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [20] [21].

Diagram 1: The CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Cutting Mechanism. This workflow illustrates the sequential process from complex assembly to double-strand break formation, highlighting key steps like PAM recognition and R-loop formation.

Cellular Repair of Cas9-Induced Breaks

The DSB generated by Cas9 is not the end point of genome editing; it is the beginning of a cellular repair process. The outcome of editing is entirely determined by which of the cell's endogenous DNA repair pathways resolves the break [21] [23]. The two primary pathways are Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR).

Table 2: Major DNA Repair Pathways for CRISPR-Cas9-Induced Breaks

| Repair Pathway | Mechanism | Cellular Context | Typical Editing Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Ligates broken ends directly without a template. Error-prone [20] [21]. | Active throughout cell cycle; predominant in post-mitotic cells (e.g., neurons) [20] [23]. | Small insertions or deletions (indels); leads to gene knockouts. |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | Uses microhomologous sequences (5-25 bp) flanking the break for end joining. Error-prone [21]. | Active in S/G2/M phases of dividing cells [23]. | Larger deletions; distinct indel pattern. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Uses a homologous DNA template (donor) for precise repair [20] [21]. | Restricted to late S/G2 phases; inefficient in non-dividing cells [20] [23]. | Precise gene insertion or correction. |

Diagram 2: DNA Repair Pathway Choices After a CRISPR-Cas9 Break. The cellular machinery repairs the DSB via competing pathways, leading to different genetic outcomes, from error-prone indels to precise corrections.

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Studying DSB Mechanics

Cutting-edge research into CRISPR-Cas9 cutting and repair dynamics relies on sophisticated protocols. The following methodologies are critical for quantifying and understanding DSB mechanics in various biological contexts.

Protocol: Quantifying DSB Kinetics and Repair in Human Neurons

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 Nature Communications study, highlights the unique challenges of editing in non-dividing cells [23].

- Objective: To characterize the efficiency, outcome, and timing of CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSB repair in post-mitotic human neurons.

- Key Methodology:

- Cell Model Generation: Differentiate human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) into cortical-like excitatory neurons. Validate post-mitotic state (Ki67-negative) and neuronal identity (NeuN-positive) [23].

- Cas9 Delivery via VLPs: Use Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) pseudotyped with VSVG/BRL glycoproteins to efficiently deliver pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) into neurons. This method achieves high transduction efficiency without relying on cell division [23].

- Time-Course Analysis: Harvest cells at multiple time points post-transduction (e.g., days 1, 4, 7, 14). Extract genomic DNA and perform next-generation sequencing (e.g., amplicon sequencing) of the target locus.

- Data Analysis: Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to quantify the percentage of indels and the spectrum of insertion/deletion mutations at each time point.

- Expected Results: Unlike dividing cells, where indels plateau within days, neurons show a prolonged accumulation of indels over up to two weeks, reflecting slower DSB repair kinetics and a preference for NHEJ over MMEJ pathways [23].

Protocol: Single-Molecule Dynamics of DSB Repair (UMI-DSBseq)

This method provides high-resolution, quantitative data on DSB intermediates and repair products simultaneously [24].

- Objective: To simultaneously quantify DSB intermediates and final repair products at an endogenous locus, enabling the measurement of precise repair rates.

- Key Methodology:

- RNP Delivery: Deliver pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP into cells (e.g., tomato protoplasts or human cells) via PEG-mediated transformation or electroporation for synchronized DSB induction [24].

- Library Preparation (UMI-DSBseq):

- DNA Extraction: Harvest cells at multiple time points post-editing.

- End Repair: Use enzymes to create blunt ends on all DNA molecules, including unrepaired DSBs.

- Adaptor Ligation: Ligate adaptors containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to all blunt ends. This labels each original DNA molecule, allowing for accurate quantification and tracking of DSBs and intact molecules after sequencing [24].

- PCR Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify the target region and perform high-throughput sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: A custom computational pipeline (e.g., available on GitHub) categorizes each sequenced molecule as:

- Unrepaired DSB: Molecule with adaptor ligated at the cut site.

- Precisely Repaired: Sequence identical to the original, unedited allele.

- Error-Repaired: Contains indels [24].

- Expected Results: This technique revealed that precise repair (scar-less re-ligation) accounts for a significant majority of repair events, explaining the gap between high cleavage rates and lower observed indel frequencies [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for CRISPR-Cas9 DSB Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Description | Application in DSB Research |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 Nuclease | The standard Cas9 protein from S. pyogenes; creates blunt-ended DSBs. | The core effector protein for inducing targeted DSBs in most experimental systems [20] [21]. |

| Pre-assembled RNP | A complex of purified Cas9 protein and synthetic gRNA. | Gold standard for transient delivery; reduces off-target effects and allows for synchronized DSB induction in various cells, including primary and non-dividing cells [23] [24]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered particles that deliver protein cargo (e.g., Cas9 RNP) instead of genetic material. | Enables efficient delivery of CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect cells, such as neurons [23]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Lipid-based vesicles that encapsulate and deliver CRISPR cargo. | A leading method for in vivo systemic delivery of CRISPR components, particularly to the liver [9]. |

| UMI-DSBseq | A molecular and computational toolkit using Unique Molecular Identifiers. | Enables multiplexed, single-molecule quantification of DSB intermediates and repair products over time, providing direct measurement of cutting and repair rates [24]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | High-throughput DNA sequencing technologies. | The primary method for analyzing editing outcomes, including indel spectrum, efficiency, and off-target assessment via targeted amplicon sequencing. |

The creation of a targeted double-strand break is the foundational event that unlocks the full potential of CRISPR-Cas9 as a genome-editing tool. From the initial assembly of the Cas9-gRNA complex to the recognition of the PAM sequence and the final catalytic cleavage, each step is a marvel of biological precision. However, the ultimate genetic outcome is not written by CRISPR alone but is determined by the cell's own repair machinery. As research advances, the growing toolkit—from VLPs and LNPs for delivery to UMI-DSBseq for single-molecule resolution analysis—empowers scientists to dissect these mechanisms with ever-greater clarity. This deep understanding is paramount for translating CRISPR technology from a powerful laboratory technique into safe and effective therapeutic agents, paving the way for a new era in genetic medicine and drug discovery.

Non-Homologous End Joining vs. Homology-Directed Repair

In CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the Cas9 nuclease creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA, but the genetic outcome is entirely determined by the cell's endogenous repair pathways [25]. The competition between two principal mechanisms—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—represents a fundamental biological crossroads that dictates the precision and result of the edit [26]. Understanding and controlling these pathways is crucial for advancing therapeutic applications, as NHEJ is efficient but error-prone, while HDR offers precision but operates at low efficiency, particularly in non-dividing cells [23] [26].

This guide provides a technical comparison of NHEJ and HDR, details their molecular mechanisms, and synthesizes current strategies for manipulating these pathways to achieve desired editing outcomes, framing this discussion within the practical context of CRISPR-Cas9 research.

DNA Repair Pathway Fundamentals

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is an error-prone DNA repair pathway that functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [25]. Its key characteristic is the frequent introduction of small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair junction [27]. While this makes NHEJ ideal for generating gene knockouts, its lack of precision is a significant limitation for edits requiring accuracy [25]. NHEJ is the predominant and most efficient DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells [28].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a precise repair mechanism that uses a homologous DNA sequence—such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template—to accurately repair the DSB [25]. This pathway is essential for precise gene edits, including nucleotide substitutions, gene insertions, and the creation of tagged proteins [25] [26]. However, a major limitation is that HDR is inherently less efficient than NHEJ and is primarily active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it particularly challenging to use in non-dividing cells [23] [26].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of NHEJ and HDR

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No template needed [25] | Requires homologous donor template (e.g., sister chromatid, ssDNA, dsDNA donor) [25] |

| Primary Role in CRISPR | Gene knockouts; introduction of INDELs [25] | Precise gene knock-ins; nucleotide substitutions [25] [26] |

| Fidelity | Error-prone; often results in small insertions/deletions (indels) [25] [27] | High-fidelity; enables precise, defined edits [25] |

| Efficiency | High; dominant pathway in most mammalian cells [26] [28] | Low; inefficient, especially in non-dividing cells [23] [26] |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all cell cycle phases [23] | Primarily restricted to S and G2 phases [23] |

| Key Enzymes/ Factors | DNA-PKcs, Ku70/80, DNA Ligase IV [27] [29] | RAD51, BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD52 [28] |

Pathway Mechanics and Experimental Workflows

Visualizing the Core Pathways and Key Experiments

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental decision between NHEJ and HDR after a CRISPR-induced break, and a key experimental workflow for studying these pathways in non-dividing cells.

Diagram 1: CRISPR Repair Pathway Decision

Diagram 2: Studying Repair in Non-Dividing Cells

Beyond NHEJ and HDR: Alternative Repair Pathways

The DSB repair landscape is more complex than the simple NHEJ-HDR dichotomy. Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) are two alternative, error-prone pathways that significantly contribute to imprecise editing outcomes, even when NHEJ is suppressed [28].

MMEJ relies on short microhomology sequences (2-20 base pairs) flanking the DSB for repair, typically resulting in deletions [28]. SSA requires longer homologous sequences and is mediated by Rad52, leading to deletions of the intervening sequence [28]. Studies show that inhibiting key effectors of these pathways—such as POLQ for MMEJ or Rad52 for SSA—can reduce specific imprecise integration patterns and improve the proportion of perfect HDR events [28].

Strategic Pathway Manipulation for Enhanced Editing

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Modulation

Researchers have developed chemical and genetic strategies to shift the balance from the dominant NHEJ pathway toward HDR. The table below summarizes key small molecules used for this purpose and their quantified effects.

Table 2: Small Molecule Modulators of DNA Repair Pathways

| Small Molecule | Target/Pathway | Effect on Editing | Quantified Enhancement | Key Considerations / Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repsox | TGF-β signaling inhibitor; promotes NHEJ [30] | Increases NHEJ-mediated knockout efficiency [30] | 3.16-fold increase in porcine cells (RNP delivery) [30] | Acts in a cell cycle-independent manner [30] |

| AZD7648 | DNA-PKcs inhibitor (NHEJ inhibitor) [27] | Intended to enhance HDR by suppressing NHEJ [27] | - | Risk: Can cause exacerbated genomic aberrations (large deletions, chromosomal translocations) [27] |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | NHEJ pathway inhibitor [28] | Increases perfect HDR frequency in knock-in [28] | ~3-fold increase in knock-in efficiency (5.2% to 16.8%) [28] | Established method, but imprecise integration still occurs [28] |

| ART558 | POLQ inhibitor (MMEJ inhibitor) [28] | Reduces large deletions; can increase perfect HDR frequency [28] | Significant increase in perfect HDR; reduces large (≥50 nt) deletions [28] | Suppressing MMEJ can improve precision [28] |

| D-I03 | Rad52 inhibitor (SSA inhibitor) [28] | Reduces asymmetric HDR and other imprecise donor integrations [28] | Reduces specific imprecise integration patterns [28] | Effect may depend on nature of DNA cleavage ends [28] |

| Zidovudine (AZT) | Thymidine analog; suppresses HDR [30] | Enhances NHEJ-mediated gene knockout [30] | 1.17-fold increase in porcine cells [30] | - |

Optimizing Donor Template Design for HDR

The structure and delivery of the donor template are critical factors for successful HDR. Key parameters include:

- Strandedness and Orientation: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors often outperform double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). In potato protoplasts, an ssDNA donor in the "target" orientation (coinciding with the sgRNA-recognized strand) achieved the highest HDR efficiency [31].

- Homology Arm (HA) Length: While longer HAs (e.g., 300 bp to 1 kb) are traditionally used and can increase HDR efficiency [32], shorter HAs can be sufficient. Studies in potato and animal models show that ssDNA donors with HAs as short as 30-50 nucleotides can support efficient HDR or homology-mediated integration [31] [32].

- Template Delivery: Using RNP complexes (pre-assembled Cas9 protein and guide RNA) along with the donor template is a highly efficient strategy for both NHEJ and HDR, as it minimizes the time the nuclease is active and can reduce off-target effects [28] [31].

Advanced Research and Clinical Implications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying NHEJ and HDR

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 and sgRNA; enables transient editing, high efficiency, and reduced off-target effects [28] [31]. |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) | Engineered particles (e.g., VSVG/BRL-pseudotyped) for efficient delivery of CRISPR components into challenging cells like human neurons [23]. |

| ssDNA Donor Template | Single-stranded oligonucleotide with homology arms; often leads to higher HDR efficiency than dsDNA, especially with short inserts [31]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) | Chemical suppresses the dominant NHEJ pathway to increase the relative frequency of HDR events [28]. |

| Pathway-Specific Inhibitors (ART558, D-I03) | Tools to dissect the roles of MMEJ (via POLQ inhibition) and SSA (via Rad52 inhibition) in imprecise repair outcomes [28]. |

| Long-Read Amplicon Sequencing (PacBio) | Essential for comprehensive genotyping; detects large deletions and complex structural variations missed by short-read sequencing [27] [28]. |

Addressing Genomic Stability and Safety Concerns

A pressing concern in therapeutic genome editing is the potential for on-target genomic aberrations beyond small indels. Recent studies reveal that CRISPR/Cas9 editing can lead to large structural variations (SVs), including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [27]. These events are particularly aggravated by the use of certain HDR-enhancing strategies, such as DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648), which can cause a thousand-fold increase in the frequency of chromosomal translocations [27]. This underscores the critical need for advanced genotyping methods like long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) or assays like CAST-Seq to thoroughly assess editing outcomes and ensure patient safety [27] [28].

Cell-Type Specific Repair Responses

The choice of cell model is paramount, as DNA repair is not universal. A landmark 2025 study demonstrated that postmitotic human neurons repair Cas9-induced DSBs differently than genetically identical dividing cells (iPSCs) [23]. Neurons exhibit a much narrower distribution of indel outcomes, favor NHEJ-like repair, and accumulate edits over a prolonged period of up to two weeks, contrasting with the rapid repair seen in dividing cells [23]. This has profound implications for developing therapies for neurological diseases and highlights that editing strategies optimized in common cell lines may not translate to clinically relevant postmitotic cells.

The interplay between NHEJ and HDR forms the cornerstone of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing outcomes. While NHEJ offers a robust tool for gene disruption, HDR holds the promise of precise genetic surgery. Current research is focused on tilting this balance toward precision by inhibiting competing pathways, optimizing donor templates, and adapting strategies to specific cell types. However, emerging challenges, such as the risk of on-target structural variations and the unique repair landscape of non-dividing cells, demand continued innovation in tool development and safety assessment. A deep understanding of these cellular repair pathways is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for the safe and effective clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins constitute an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that provides sequence-specific protection against mobile genetic elements such as viruses and plasmids [33] [34]. These systems capture fragments of invading nucleic acids and incorporate them as "spacers" within CRISPR arrays in the host genome, creating a heritable genetic record of past infections [35] [34]. Upon subsequent encounters, the arrays are transcribed and processed into CRISPR RNA (crRNA) that guides Cas proteins to recognize and cleave complementary foreign nucleic acids, thereby conferring immunity [36] [33]. The natural diversity of these systems is remarkable, with CRISPR-Cas loci identified in approximately 50% of sequenced bacterial genomes and nearly 90% of sequenced archaea [34].

The classification of CRISPR-Cas systems reflects their evolutionary relationships and functional mechanisms. Systems are primarily categorized into two classes based on the architecture of their effector modules [37] [36]. Class 1 systems utilize multi-subunit effector complexes, while Class 2 systems employ single, large protein effectors [38] [39]. This fundamental distinction has profound implications for both the natural biology of these systems and their technological applications, particularly in genome editing where Class 2 systems have been more widely adopted due to their simplicity [36] [35]. Understanding this diversity provides the foundation for harnessing these systems for basic research and therapeutic development.

Classification and Genomic Organization

Hierarchical Structure of CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR-Cas classification employs a multifaceted approach that combines sequence similarity, phylogenetic analysis, gene neighborhood examination, and experimental data to establish evolutionary relationships [39]. The hierarchical structure progresses from broad categories to specific variants: Class → Type → Subtype → Variant [39]. The current classification encompasses 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, representing a significant expansion from the 6 types and 33 subtypes documented in 2020, reflecting the rapid discovery of novel systems [40].

The two-class division is based on effector complex architecture. Class 1 systems (types I, III, IV, and VII) employ multisubunit effector complexes in which different Cas proteins assemble into a complex that mediates crRNA processing and target interference [37] [40]. In contrast, Class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) utilize a single, large multidomain effector protein for the same functions [36] [38]. This classification system continues to evolve as new variants are discovered through computational mining of genomic and metagenomic databases [40] [35].

Genomic Locus Architecture

CRISPR-Cas loci typically consist of several key components: the CRISPR array itself, composed of direct repeats alternating with variable spacers; an AT-rich leader sequence that often serves as a promoter for array transcription; and cas genes that encode the Cas proteins responsible for adaptation, expression, and interference functions [34]. The adaptation module, containing Cas1 and Cas2 proteins, is relatively conserved across most systems and is responsible for acquiring new spacers from invading DNA [36]. The effector module shows substantially greater diversity and defines the specific type and subtype of each system [36] [38].

Some CRISPR-Cas systems exist in "non-autonomous" forms that lack essential components, particularly the adaptation module genes cas1 and cas2 [36]. These systems may depend on adaptation modules encoded elsewhere in the genome or may have specialized functions that do not require spacer acquisition [36] [39]. Type IV systems represent a prominent example of this non-autonomous architecture, typically lacking adaptation modules and often being encoded on plasmids rather than chromosomal DNA [39].

Class 1 CRISPR-Cas Systems: Multi-Subunit Effector Complexes

Class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems represent the evolutionarily ancestral form of CRISPR immunity and are the most abundant in prokaryotes [39]. These systems comprise approximately 90% of all identified CRISPR-Cas loci in bacteria and archaea, with near-universal presence (close to 100%) in archaeal genomes [37] [36]. Despite their natural abundance, Class 1 systems have been less widely adopted for biotechnological applications compared to Class 2 systems, primarily due to the practical challenges of reconstituting multi-protein complexes in heterologous systems [39].

The defining feature of Class 1 systems is their utilization of multi-subunit effector complexes, often referred to as Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) complexes [34] [39]. These complexes typically consist of multiple Cas protein subunits that assemble in uneven stoichiometry to form a functional unit capable of crRNA binding, target recognition, and in some cases, nucleic acid cleavage [36]. Recent advances in genetic engineering have begun to overcome the technical challenges of working with Class 1 systems, leading to increased interest in their unique properties for specialized applications [39].

Type I Systems

Type I systems represent the most prevalent CRISPR-Cas type in nature and utilize a characteristic effector complex that recruits the Cas3 protein for DNA degradation [37] [39]. The Cascade complex varies in composition across subtypes but typically includes Cas5, Cas6, Cas7, and Cas8 proteins in various combinations [39]. Cas6 often functions as the pre-crRNA processing enzyme, cleaving the long primary transcript into individual crRNA units within the repeats [34].

A defining feature of type I systems is the Cas3 protein, which contains both helicase and nuclease activities [37] [39]. After the Cascade complex identifies and binds to a target DNA sequence complementary to the crRNA guide, it recruits Cas3, which processively degrades extended regions of DNA [39]. This mechanism results in large-scale DNA deletions rather than precise double-strand breaks, making type I systems particularly useful for applications requiring extensive genomic rearrangements [39]. Type I systems are further divided into seven subtypes (I-A through I-G) based on the specific composition of their Cascade complexes and accessory proteins [37].

Type III Systems

Type III CRISPR-Cas systems are considered among the most complex and are hypothesized to represent the evolutionary ancestor of all other CRISPR systems [39]. These systems are characterized by the presence of Cas10, a multidomain protein that serves as the large subunit of the effector complex [37] [40]. Cas10 typically contains a polymerase/cyclase domain that synthesizes cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) second messengers upon target recognition [40].

Unlike other CRISPR types, type III systems can target both RNA and DNA, though DNA cleavage is considered their primary immune function [39]. These systems can cleave RNA directly through the effector complex or indirectly by activating non-specific RNases through the cOA signaling pathway [40]. Recent analyses have identified new subtypes (III-G, III-H, and III-I) that exhibit reductive evolution, with some losing the cOA signaling pathway or specific nuclease activities [40]. The type III systems demonstrate exceptional complexity in their regulatory mechanisms and interference capabilities.

Type IV Systems

Type IV CRISPR-Cas systems represent atypical, non-autonomous systems that lack key components of canonical CRISPR-Cas immunity [39]. These systems are typically missing adaptation modules (cas1 and cas2) and often lack functional nuclease effectors, particularly in subtypes IV-A and IV-B [39]. Type IV systems are frequently encoded on plasmids rather than bacterial chromosomes and contain a distinct Cas7-type protein as their defining feature [39].

The precise biological function of type IV systems remains enigmatic, though evidence suggests they may participate in plasmid competition or regulate conjugation by targeting specific DNA sequences [39]. Unlike most other CRISPR types, type IV systems appear to have diverged from adaptive immunity functions and may represent specialized systems for nucleic acid targeting in the context of mobile genetic element competition [39]. The IV-C subtype uniquely contains a helicase domain resembling cas10, suggesting functional diversity within this type [39].

Type VII Systems

Type VII represents the most recently classified CRISPR-Cas system, identified through deep terascale clustering of microbial genomic data [40] [39]. These systems are characterized by the presence of Cas14 (also referred to as Cas7-11 in type III-E systems), an effector protein containing a metallo-β-lactamase (β-CASP) domain [40]. Type VII loci typically lack adaptation modules and are often found associated with substituted repeats in their CRISPR arrays, suggesting infrequent spacer acquisition [40].

Structural analysis reveals that type VII effector complexes can comprise up to 12 subunits, making them among the largest Class 1 complexes [40]. Despite their classification as Class 1 systems, type VII effector complexes target RNA in a crRNA-dependent manner, with cleavage mediated by the nuclease activity of Cas14 [40]. Phylogenetic and structural evidence suggests that type VII systems evolved from type III systems through a reductive evolutionary process, retaining the RNA-targeting capability while simplifying certain complex features [40].

Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems: Single-Effector Proteins

Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems are defined by their utilization of a single, large multidomain effector protein for crRNA processing and target interference [36] [38]. These systems represent approximately 10% of all identified CRISPR-Cas loci and are found almost exclusively in bacterial genomes, with no documented occurrences in hyperthermophiles [36]. The relative simplicity of Class 2 systems, particularly the requirement for only a single effector protein, has made them ideal for adaptation as genome engineering tools [36] [35].

The discovery and characterization of Class 2 effectors has expanded dramatically through computational mining of genomic and metagenomic datasets [36] [35]. By using Cas1 or CRISPR arrays as "bait" in large-scale searches, researchers have identified numerous novel Class 2 variants with diverse properties [36] [38]. This exploration has revealed that Class 2 systems have evolved on multiple independent occasions through recombination events between Class 1 adaptation modules and effector proteins acquired from distinct mobile genetic elements [36] [38].

Type II Systems

Type II systems are the best-characterized Class 2 systems, largely due to the revolutionary applications of their effector protein, Cas9, in genome editing [33] [34]. These systems typically include cas1, cas2, and cas9 genes, along with the additional RNA components tracrRNA and frequently csn2 [38]. Cas9 is a large multidomain protein that contains two distinct nuclease domains: an HNH domain that cleaves the target DNA strand complementary to the crRNA guide, and a RuvC-like domain that cleaves the non-target strand [33] [34].

A defining feature of type II systems is their requirement for two RNA components: the crRNA, which contains the guide sequence for target recognition, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which facilitates pre-crRNA processing and Cas9 activation [34]. In laboratory applications, these are often fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to simplify implementation [34]. Cas9 requires a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site, typically 5'-NGG-3' for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 [33]. Type II systems are divided into three subtypes (II-A, II-B, and II-C) based on variations in their accessory proteins and genetic architecture [39].

Type V Systems

Type V CRISPR-Cas systems utilize Cas12 (formerly known as Cpf1) as their effector protein and exhibit several distinctive features compared to Cas9 [34] [39]. Cas12 proteins contain a single RuvC-like nuclease domain that cleaves both strands of target DNA, creating staggered ends with 5' overhangs rather than the blunt ends produced by Cas9 [34]. Type V systems typically recognize T-rich PAM sequences (5'-TTTV-3') and do not require a tracrRNA for function, relying solely on crRNA for guidance [34].

The type V category has expanded to include numerous subtypes (A-I and U) with diverse properties [39]. Among these, several notable variants have been characterized: Cas12a (Cpf1) processes its own pre-crRNA arrays, enabling multiplexed targeting from a single transcript [39]; Cas12f (Cas14) represents an exceptionally small effector (400-700 amino acids) that targets single-stranded DNA [39]; and certain type V variants have been engineered as CRISPR-associated transposases (CASTs) capable of inserting large DNA fragments without creating double-strand breaks [39]. This functional diversity makes type V systems particularly valuable for specialized applications beyond standard gene editing.

Type VI Systems

Type VI systems are defined by their use of Cas13 effectors, which represent the only CRISPR systems that exclusively target RNA rather than DNA [34] [39]. Cas13 proteins contain two higher eukaryotes and prokaryotes nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domains that mediate RNA cleavage activity [38] [34]. Upon recognition of a target RNA sequence complementary to the crRNA guide, Cas13 exhibits collateral RNase activity, non-specifically cleaving nearby RNA molecules in addition to the target [34].

This collateral cleavage effect has been harnessed for diagnostic applications, most notably in the SHERLOCK (Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing) platform for detecting specific nucleic acid sequences [37] [34]. Type VI systems include four subtypes (VI-A through VI-D) with variations in their targeting requirements and cleavage specificities [33]. The RNA-targeting capability of type VI systems provides a powerful approach for transcript knockdown, RNA editing, and nucleic acid detection without permanent genomic alteration [39].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR-Cas Systems

Structural and Functional Comparison

The fundamental architectural differences between Class 1 and Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems translate to distinct functional characteristics and biological implications. Class 1 systems, with their multi-subunit effectors, generally exhibit more complex regulation and potentially more sophisticated target recognition mechanisms [36]. The Cascade complexes of Class 1 systems often undergo conformational changes upon target binding that activate nuclease functions or recruit additional effector proteins [36]. In contrast, Class 2 systems employ a single protein that integrates all functions required for interference, resulting in simpler but potentially less regulatable activity [38].

The evolutionary distribution of the two classes reveals intriguing patterns. Class 1 systems dominate in archaea and are more prevalent in bacteria, particularly in thermophilic environments [36]. This distribution suggests possible advantages of multi-subunit effectors in certain environmental conditions or cellular contexts. Class 2 systems show a more restricted phylogenetic range, being largely confined to bacteria and absent from hyperthermophiles, indicating possible evolutionary constraints on their origin or maintenance [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Major CRISPR-Cas Types and Their Characteristics

| Class | Type | Effector Complex/Protein | Target | Signature Proteins | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I | Multi-subunit Cascade | dsDNA | Cas3 | Recruits Cas3 for processive DNA degradation; most common type |

| Class 1 | III | Multi-subunit complex | ssRNA/DNA | Cas10 | Targets both RNA and DNA; produces signaling molecules |

| Class 1 | IV | Multi-subunit complex | dsDNA | Distinct Cas7 | Non-autonomous; often plasmid-encoded; function not fully characterized |

| Class 1 | VII | Multi-subunit complex | RNA | Cas14 | β-CASP nuclease; evolved from type III; targets RNA |

| Class 2 | II | Cas9 | dsDNA | Cas9 | Requires tracrRNA; creates blunt-end DSBs; most widely used in editing |

| Class 2 | V | Cas12 | dsDNA | Cas12 | Creates staggered DSBs; self-processes pre-crRNA; no tracrRNA needed |

| Class 2 | VI | Cas13 | RNA | Cas13 | RNA-guided RNA cleavage; exhibits collateral activity |

Quantitative Distribution in Prokaryotes

The relative abundance of different CRISPR-Cas types reveals striking patterns in their natural distribution. Class 1 systems collectively account for approximately 90% of all identified CRISPR-Cas loci across prokaryotes, with type I systems alone representing the majority of these [37] [36]. Among Class 2 systems, type II is the most prevalent, followed by types V and VI [36]. The recently identified type VII systems appear to be relatively rare compared to the more established types [40].

Analysis of CRISPR-Cas system abundance shows a characteristic "long-tail" distribution, with the well-characterized systems being relatively common while newly discovered variants are typically rare [40]. This pattern suggests that numerous additional rare variants remain to be discovered in undersampled taxonomic groups and environments [40]. The differential distribution of CRISPR types across phylogenetic lineages and habitats reflects both evolutionary history and functional adaptation to specific ecological niches and defensive requirements.

Table 2: Natural Abundance and Distribution of CRISPR-Cas Systems

| System | Approximate Abundance | Primary Phylogenetic Distribution | Notable Subtypes/Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 Type I | ~60% of all systems | Bacteria and Archaea | I-A to I-G (I-E most studied) |

| Class 1 Type III | ~30% of all systems | Primarily Archaea | III-A to III-I (III-A, III-B most common) |

| Class 1 Type IV | Rare | Bacteria (plasmid-encoded) | IV-A, IV-B, IV-C |

| Class 1 Type VII | Rare | Archaea | Cas14-containing systems |

| Class 2 Type II | ~7% of all systems | Bacteria only | II-A, II-B, II-C (II-A includes SpCas9) |

| Class 2 Type V | ~2% of all systems | Bacteria only | V-A to V-I, V-U (V-A includes Cas12a/Cpf1) |

| Class 2 Type VI | ~1% of all systems | Bacteria only | VI-A to VI-D (VI-B includes Cas13b) |

Experimental Methodologies for CRISPR-Cas System Characterization

Computational Discovery Pipelines

The discovery of novel CRISPR-Cas systems has been revolutionized by computational pipelines that mine the vast amount of sequence data available in genomic and metagenomic databases [36] [35]. These pipelines typically employ a multi-step process beginning with the identification of "seed" sequences that indicate the potential presence of a CRISPR-Cas system [36]. The most common seeds are the Cas1 protein, which is highly conserved and present in most systems, or CRISPR arrays themselves, which can identify non-autonomous systems lacking adaptation modules [36].

Following seed identification, the genomic neighborhood surrounding the seed is analyzed for the presence of additional cas genes and CRISPR arrays [36] [38]. Putative effector proteins are identified based on size (>500 amino acids for Class 2 effectors) and the presence of characteristic domains such as RuvC, HNH, or HEPN [38]. Candidate loci are then compared against profiles of known systems to classify them into established types or identify novel variants [36]. This approach has led to the discovery of numerous novel systems, including additional subtypes of types V and VI, and the recently identified type VII systems [36] [40].

Figure 1: Computational Pipeline for CRISPR-Cas System Discovery. This workflow illustrates the bioinformatics approach used to identify novel CRISPR-Cas systems from genomic and metagenomic sequence data.

Functional Characterization of Novel Systems

Once a novel CRISPR-Cas system has been identified computationally, experimental characterization is essential to validate its function and determine its molecular mechanisms. The initial functional assessment typically involves heterologous expression in a model system such as E. coli to test for interference activity against target sequences [38]. This approach determines whether the system can protect against phage infection or plasmid transformation in a sequence-specific manner [38].

Detailed biochemical characterization includes in vitro reconstruction of the interference reaction using purified components to assess target recognition requirements, cleavage patterns, and cofactor dependencies [38]. For Class 2 systems, this involves expression and purification of the effector protein and synthesis of the corresponding crRNA [38]. For Class 1 systems, the process is more complex, requiring co-expression and purification of multiple subunits that assemble into the functional effector complex [39]. Molecular characterization determines key properties such as PAM requirements (for DNA-targeting systems), target specificity, cleavage kinetics, and potential collateral activity [38].

Molecular Analysis Techniques

Specific experimental approaches have been developed to characterize key aspects of CRISPR-Cas system function. PAM identification typically employs plasmid transformation assays where libraries of potential target sequences containing randomized PAM regions are tested for interference [38]. Alternatively, in vitro selection methods like SELEX can identify preferred PAM sequences by assessing protein binding to randomized DNA libraries [38].

Target cleavage specificity is often evaluated using in vitro cleavage assays with synthetic target sequences, followed by gel electrophoresis to visualize cleavage products and determine cut sites [38]. For systems with putative RNase activity, RNA cleavage assays with fluorescently labeled substrates can detect cleavage products with high sensitivity [38]. High-throughput methods like RNA-seq can comprehensively map cleavage specificity and identify potential off-target effects [38].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas System Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET, pBAD, mammalian expression vectors | Heterologous expression of Cas effectors and complex components |

| Guide RNA Templates | Synthetic DNA oligos, gRNA expression vectors | Provision of crRNA and tracrRNA components for target recognition |

| Target Substrates | Plasmid libraries, synthetic oligonucleotides, phage DNA | Testing interference activity and sequence requirements |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | E. coli BL21, HEK293T, phage susceptibility assays | Functional testing in cellular environments |

| Purification Systems | Affinity tags (His-tag, GST-tag), chromatography resins | Isolation of recombinant Cas proteins and complexes |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorescent reporters, antibodies, nucleotide analogs | Monitoring cleavage activity, protein expression, and localization |

Applications in Research and Therapeutic Development

Genome Editing and Regulation