CRISPR-Cas9 Double-Strand Break Formation: Molecular Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism for double-strand break (DSB) formation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR-Cas9 Double-Strand Break Formation: Molecular Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

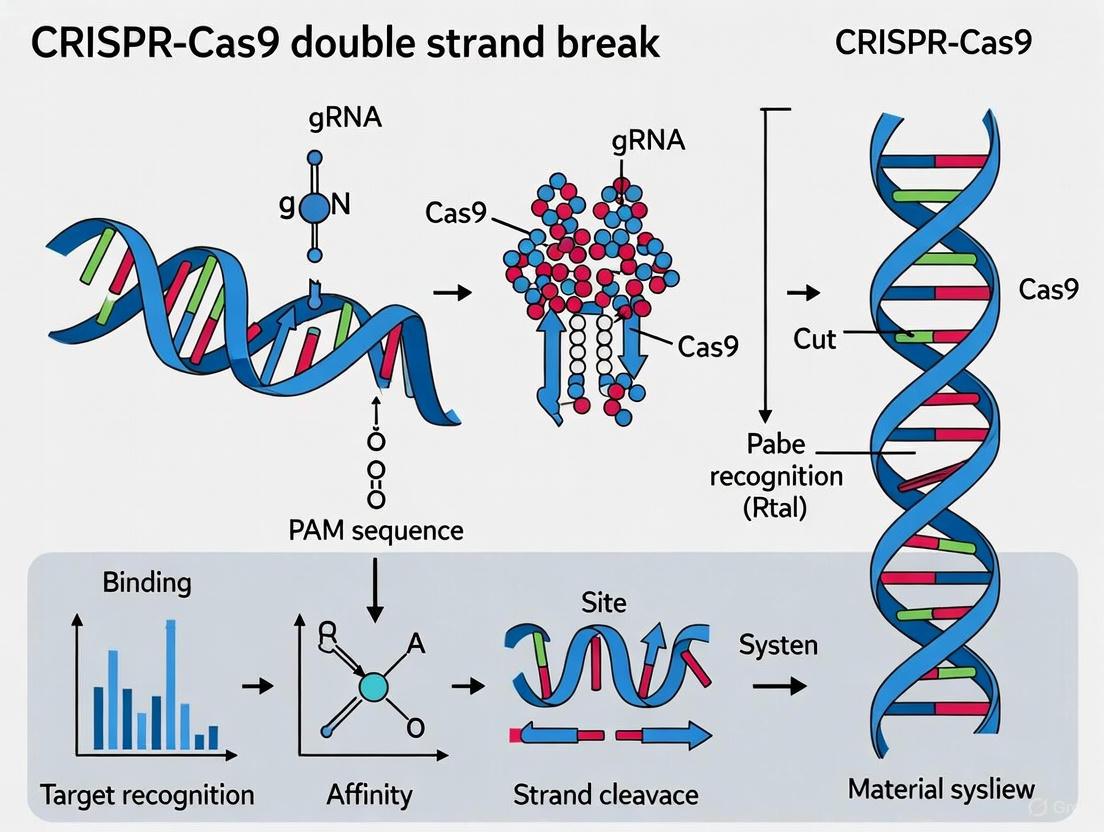

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism for double-strand break (DSB) formation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental structural biology of the Cas9-guide RNA complex and its programmable DNA targeting, detailing the precise molecular events from PAM recognition through R-loop formation to dual-nuclease cleavage. The content covers advanced therapeutic applications across genetic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases, including recently approved therapies and ongoing clinical trials. It addresses critical challenges including off-target effects, delivery limitations, and repair pathway control, while comparing CRISPR-Cas9 with alternative gene-editing platforms. The synthesis provides a roadmap for optimizing precision editing tools and translating mechanistic insights into clinical breakthroughs.

The Molecular Architecture of CRISPR-Cas9: Deconstructing the DNA Targeting Machinery

Cas9 Protein Architecture and Catalytic Mechanism

The CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) is an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease that serves as the central effector molecule in type II CRISPR-Cas systems. Its structure and activation mechanism provide the foundation for its genome-editing capabilities [1] [2].

Structural Organization and Domains

Cas9 exhibits a bilobed architecture composed of two primary lobes: the nuclease (NUC) lobe and the recognition (REC) lobe, connected by two linking segments [1]. The protein encompasses several critical domains and regions:

- RuvC Domain: Located in the NUC lobe, this domain cleaves the non-target DNA strand (the strand not complementary to the guide RNA). It forms a structural core consisting of a six-stranded β sheet surrounded by four α helices [1] [2].

- HNH Domain: This domain is responsible for cleaving the target DNA strand (the strand complementary to the guide RNA). In the apo-Cas9 structure (without bound nucleic acids), the HNH active site is often poorly ordered, suggesting conformational flexibility that becomes ordered upon DNA binding [1] [2].

- PAM-Interacting (PI) Domain: Situated within the NUC lobe, this domain recognizes the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that is essential for self versus non-self discrimination in bacterial immunity [2].

- REC Lobe (REC1, REC2, and REC3 domains): This lobe is primarily responsible for binding the guide RNA and facilitating the recognition of target DNA [2].

Table 1: Core Functional Domains of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9)

| Domain/Region | Primary Function | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| RuvC Domain | Cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand | Six-stranded β sheet core surrounded by α helices |

| HNH Domain | Cleaves the complementary DNA strand | β-β-α fold, undergoes conformational activation |

| REC Lobe | Facilitates guide RNA binding and target recognition | Primarily α-helical, interacts with guide RNA |

| PAM-Interacting Domain | Recognizes the NGG protospacer adjacent motif | Mediates initial DNA binding and unwinding |

| Arg-rich Region | Likely mediates nucleic acid binding | Connects the two structural lobes (residues 59-76) |

Conformational Activation and DNA Cleavage Mechanism

Cas9 undergoes significant structural rearrangements to transition from an inactive to a DNA-cleaving enzyme. In its apo state, Cas9 exists in a conformation that is incapable of DNA cleavage. The binding of the guide RNA induces a major reorientation of the structural lobes, forming a central channel where DNA substrates are bound. This RNA-induced activation is a critical step, "implicating guide RNA loading as a key step in Cas9 activation" [1].

The process of target DNA recognition and cleavage follows a defined sequence [2]:

- PAM Recognition: The Cas9-gRNA complex searches the DNA through 3D and 1D diffusion. The PAM-interacting domain first identifies a correct PAM sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9).

- DNA Unwinding: PAM binding triggers the unwinding of the adjacent double-stranded DNA, exposing the seed region near the PAM.

- R-loop Formation: The guide RNA undergoes strand invasion, testing for complementarity with the target DNA strand. If fully complementary, a stable R-loop structure forms, displacing the non-target DNA strand.

- Conformational Activation and Cleavage: Successful R-loop formation triggers a final conformational change in Cas9, positioning the HNH domain to cleave the target strand and the RuvC domain to cleave the non-target strand. The HNH domain cuts the target strand 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM, while the RuvC domain cuts the non-target strand 3-5 base pairs away, typically resulting in a blunt-ended double-strand break [2].

Guide RNA Design Principles

The guide RNA (gRNA) is the targeting component that dictates the specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Its design is paramount to the success and accuracy of any genome-editing experiment [3] [4].

gRNA Components and Function

The gRNA is a chimeric molecule that combines two natural RNA elements [2] [5]:

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): This component contains the ~20 nucleotide "spacer" sequence that defines the genomic target through Watson-Crick base pairing.

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA): This structural element binds to the Cas9 protein and is essential for its activation.

In most experimental applications, these two elements are fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) of approximately 100 nucleotides, which retains full functionality [2].

Key Parameters for Efficient gRNA Design

On-Target Efficiency

On-target efficiency predicts how effectively a gRNA will mediate editing at the intended target site. Several algorithm-based scoring methods have been developed from large-scale experimental datasets [3]:

- Rule Set 2 & 3: Developed by Doench et al., these models use machine learning (gradient-boosted regression trees) on data from thousands of gRNAs to predict efficiency. Rule Set 3 is the most current and considers the tracrRNA sequence for improved accuracy [3] [4].

- CRISPRscan: This algorithm is a predictive model based on the activity data of 1,280 gRNAs validated in vivo in zebrafish [3].

- Lindel: A logistic regression model that predicts the likelihood and spectrum of insertions and deletions (indels) resulting from Cas9-mediated cleavage, providing a frameshift ratio prediction [3].

Off-Target Minimization

Minimizing off-target effects is crucial for experimental specificity and therapeutic safety. Key assessment methods include [3]:

- Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) Score: This scoring matrix, referenced in Doench's 2016 work, is based on the activity of 28,000 gRNAs with single variations. A score below 0.05 (or 0.023 in some applications) is generally considered low risk [3].

- MIT Specificity Score (Hsu-Zhang Score): Developed from data on over 700 gRNA variants with 1-3 mismatches, this score helps identify potential off-target sites across the genome [3].

- Homology Analysis: A genome-wide search for sequences similar to the designed gRNA that also contain a valid PAM. Fewer than three nucleotide mismatches, particularly those far from the PAM, are of concern [3].

Table 2: gRNA Design Considerations for Different Experimental Goals

| Experimental Goal | Primary Design Consideration | Optimal gRNA Location | Key Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout (NHEJ) | gRNA Sequence Efficiency | 5' - 65% of protein-coding region | Avoid very N- or C-terminal to prevent functional truncated proteins [4]. |

| Precise Editing (HDR) | Proximity to Edit | Within ~30 nt of the desired edit [4] | Few gRNA choices; may need alternative Cas enzymes with different PAMs [4]. |

| CRISPRa (Activation) | Location relative to TSS | ~100 nt window upstream of TSS [4] | Accurate TSS annotation (e.g., FANTOM database) is critical [4]. |

| CRISPRi (Inhibition) | Location relative to TSS | ~100 nt window downstream of TSS [4] | Accurate TSS annotation is critical [4]. |

Workflow for gRNA Design and Selection

A robust gRNA selection process involves multiple steps to balance efficiency and specificity [3] [5]:

- Identify PAM Sites: Locate all NGG (for SpCas9) sequences in the target genomic region.

- Define Candidate gRNAs: For each PAM, identify the 20 nucleotides immediately 5' to it as the potential gRNA spacer sequence.

- Score for Efficiency: Use algorithms like Rule Set 3 to rank gRNAs by predicted on-target activity.

- Analyze for Specificity: Perform a genome-wide off-target analysis using CFD or MIT scoring to shortlist gRNAs with minimal off-target risks.

- Final Selection: For gene knockout, select 2-3 high-ranking gRNAs targeting different regions of the gene to control for target accessibility and confirm phenotype consistency [4].

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Cas9 Function and DSB Repair

Understanding the outcomes of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks requires precise methodologies to quantify editing efficiency and repair dynamics.

Quantifying DSB Dynamics with UMI-DSBseq

A advanced method for characterizing DSB induction and repair is UMI-DSBseq, a molecular and computational toolkit that enables multiplexed quantification of DSB intermediates and repair products by single-molecule sequencing [6].

Key Protocol Steps [6]:

- Delivery: Preassembled Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are delivered directly into cells (e.g., tomato protoplasts) via PEG-mediated transformation to ensure synchronized DSB induction.

- Time-Course Sampling: Cells are harvested at multiple time points (e.g., over 72 hours) post-transformation.

- Library Preparation: Genomic DNA is extracted and subjected to the UMI-DSBseq protocol:

- End Repair: DNA ends are repaired by fill-in of 3' overhangs.

- Adaptor Ligation: Adapters containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are ligated directly to both unrepaired DSBs and to intact molecules (at a flanking restriction enzyme site cleaved in vitro).

- Sequencing: Illumina sequencing-ready libraries are prepared and sequenced.

- Data Analysis: Sequencing reads are categorized into:

- Unrepaired DSBs

- Wild-type intact molecules (precisely repaired or uncut)

- Indel-containing products of error-prone repair

This approach allows researchers to directly measure the rates of Cas9 cutting, precise repair, and error-prone repair, revealing that precise repair can account for up to 70% of all repair events in plant protoplasts [6].

Standard Workflow for CRISPR Gene Knockout

A common CRISPR-Cas9 experiment for gene disruption follows this protocol [5]:

- Design gRNA: Target an early exon of the gene of interest using the principles in Section 2.

- Obtain gRNA:

- Option A (Synthetic): Order a chemically synthesized sgRNA.

- Option B (Plasmid-based): Clone the gRNA sequence into an expression plasmid (e.g., via Gibson Assembly) for delivery.

- Deliver CRISPR Components: Co-deliver Cas9 and gRNA expression constructs or preassembled RNPs into your target cells using system-appropriate methods (e.g., lipofection, electroporation, microinjection).

- Screen and Validate:

- Enrich edited cells via selection (if using a selectable marker).

- Screen candidate clones by PCR amplification of the target region.

- Sequence the PCR products to determine the exact indel sequences and identify homozygous edits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Sources / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 Nuclease | The effector protein that creates DSBs; can be delivered as protein, mRNA, or encoded in a plasmid. | Widely available from commercial suppliers (e.g., IDT, Thermo Fisher). |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Chemically synthesized single-guide RNA; offers immediate activity and avoids cloning steps. | Companies like GenScript, IDT, and Synthego provide synthesis services. |

| CRISPR Plasmids | DNA vectors for in-cell expression of Cas9 and gRNA; suitable for viral packaging (lentivirus, AAV). | Non-profit repositories (e.g., Addgene) are common sources. |

| HDR Donor Templates | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) or double-stranded DNA templates for precise editing. | For edits <200 nt, use ssODNs; for larger edits, use dsDNA fragments or plasmid donors. |

| gRNA Design Tools | Web-based platforms for designing and scoring gRNAs for on-target efficiency and off-target effects. | CRISPick (Broad Institute), CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR, GenScript Design Tool [3]. |

| Validation Primers | Oligonucleotides for PCR amplification and sequencing of the target locus to confirm edits. | Standard custom oligo synthesis. |

| AI Design Assistants | AI tools that leverage published data to automate experimental design and predict off-targets. | CRISPR-GPT (Stanford) acts as a gene-editing "copilot" for researchers [7]. |

Advanced Applications and Current Research Frontiers

The understanding of Cas9 structure and refinement of gRNA design principles has directly enabled the translation of CRISPR technology into therapeutic applications and advanced research tools.

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Genome Editing

CRISPR-based therapies have progressed rapidly into clinical trials, with the first medicines receiving approval [8]:

- Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel): This therapy, approved for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, uses ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 to edit hematopoietic stem cells to reactivate fetal hemoglobin [8].

- In Vivo CRISPR Therapies: Intellia Therapeutics' phase I trial for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) demonstrated the feasibility of systemic, in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 therapy. The treatment, delivered via lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that accumulate in the liver, achieved ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels that was sustained over two years [8].

- Personalized Therapies: A landmark case in 2025 reported the first personalized, on-demand in vivo CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency. The therapy was developed, approved, and delivered in just six months, establishing a regulatory precedent for bespoke gene therapies [8].

AI-Powered Experimental Design

The complexity of CRISPR experimental design has led to the development of AI tools to assist researchers. CRISPR-GPT, a large language model developed at Stanford Medicine, was trained on 11 years of expert discussions and published scientific papers [7]. It functions as a gene-editing "copilot" that can [7]:

- Generate experimental plans for specific goals (e.g., CRISPR activation).

- Predict potential off-target edits and their likely impact.

- Explain the rationale behind each design step, flattening the learning curve for novice users.

- Incorporate safeguards to prevent the design of unethical experiments (e.g., editing human embryos).

The revolutionary power of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing is built upon the foundational biology of the Cas9 protein's structure and its guided interaction with target DNA. The bilobed architecture, encompassing nuclease and recognition lobes, undergoes precise conformational changes that are activated by guide RNA binding and culminate in site-specific DNA cleavage. Harnessing this mechanism requires meticulous gRNA design informed by sophisticated algorithms that predict on-target efficiency and minimize off-target effects, with design strategies tailored to specific experimental goals from gene knockout to precise editing. As the field advances, these core principles of protein engineering and guide design are being augmented by AI-driven tools and sophisticated delivery systems, paving the way for an expanding frontier of therapeutic applications and fundamental research discoveries.

Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) recognition serves as the fundamental gateway that enables CRISPR-Cas systems to distinguish between self and non-self DNA, initiating a cascade of events culminating in targeted double-strand break (DSB) formation. This sequence-specific recognition mechanism, while constraining the targetable genomic space, provides the critical first step in DNA interrogation by CRISPR-associated nucleases. Recent structural and biochemical studies have elucidated the sophisticated molecular machinery underlying PAM binding, revealing how Cas nucleases achieve remarkable specificity while navigating the challenges of off-target effects. This technical review examines PAM recognition within the broader context of CRISPR-Cas9 mechanisms for DSB formation research, providing researchers with current methodologies, structural insights, and clinical implications of this pivotal process.

The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) adjacent to the target DNA region cleaved by the CRISPR system. This motif represents an essential recognition element that must be identified by the Cas nuclease before it can unwind the DNA and verify complementarity with the guide RNA [9]. In the context of bacterial adaptive immunity, the PAM serves a vital function in self versus non-self discrimination—while foreign viral DNA contains PAM sequences, the bacterial genome itself lacks these motifs adjacent to stored viral sequences in the CRISPR array, thus preventing autoimmunity [9] [10].

From a mechanistic perspective, the PAM is required for Cas nuclease activation and subsequent DSB formation. The most extensively characterized Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence located directly downstream of the target sequence in the genomic DNA [11]. The PAM is not part of the guide RNA sequence but must be present in the target DNA, generally found 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the Cas9 cut site [9]. This strategic positioning enables the PAM to serve as an initial binding site that triggers local DNA melting, allowing the guide RNA to interrogate the adjacent sequence through RNA-DNA pairing [2].

Molecular Mechanisms of PAM Recognition

Structural Basis of PAM Interaction

PAM recognition occurs primarily through specific domains within the Cas nuclease that interact directly with the DNA backbone and nucleobases. Structural studies have revealed that SpCas9 employs a PAM-interacting (PI) domain containing positively charged residues that form specific hydrogen bonds with the nucleobases of the PAM sequence [2] [12]. Specifically, residues R1333 and R1335 in SpCas9 confer specificity for the two guanines in the NGG PAM by forming four hydrogen bonds with their Hoogsteen faces [12].

When the Cas9-gRNA complex searches for target sites, it first binds to PAM sequences through a combination of 3D and 1D diffusion [2]. PAM recognition triggers conformational changes that destabilize the adjacent DNA duplex, facilitating initial unwinding of the seed region (the PAM-proximal portion of the target sequence) and enabling the guide RNA to initiate strand invasion [2]. This process leads to the formation of an R-loop structure—a triple-stranded intermediate comprising the RNA-DNA hybrid and displaced non-target DNA strand [2].

PAM-Dependent Activation Cascade

The molecular events following PAM recognition occur in a defined sequence:

- Initial PAM Binding: The Cas nuclease scans DNA for compatible PAM sequences through superficial contacts with the DNA backbone [10] [12].

- DNA Destabilization: PAM binding induces conformational changes in the Cas protein that destabilize the adjacent DNA duplex, typically melting 4-5 base pairs upstream of the PAM [2].

- Seed Region Interrogation: The guide RNA tests complementarity with the exposed single-stranded DNA in the seed region [2].

- R-loop Propagation: If seed pairing is successful, the R-loop extends through the entire target region, with full complementarity triggering nuclease activation [2] [12].

- DSB Formation: The HNH nuclease domain cleaves the target strand 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target strand 3-5 base pairs away [2].

Table 1: Key Domains Involved in PAM Recognition and DNA Cleavage

| Domain | Function | Specific Role in PAM Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| PAM-Interacting (PI) Domain | PAM recognition and binding | Contains residues that directly contact PAM nucleobases; determines PAM specificity |

| REC Lobe | Guide RNA handling and DNA hybridization | Facilitates DNA melting after PAM recognition; stabilizes R-loop formation |

| HNH Domain | Target strand cleavage | Activated upon complete R-loop formation; cleaves 3 bp upstream of PAM |

| RuvC Domain | Non-target strand cleavage | Cleaves non-target strand after conformational changes triggered by PAM binding |

PAM Diversity Across CRISPR Systems

The requirement for a specific PAM sequence varies considerably among different Cas nucleases, presenting both constraints and opportunities for genome engineering applications. While SpCas9 recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM, other Cas nucleases exhibit distinct PAM preferences, enabling targeting of different genomic regions [9].

Table 2: PAM Sequences for Various Cas Nucleases Used in CRISPR Experiments

| CRISPR Nuclease | Organism Isolated From | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered from Cas12i | TN and/or TNN |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRR(N) |

| NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT |

| CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNRYAC |

| LbCas12a (Cpf1) | Lachnospiraceae bacterium | TTTV |

| AacCas12b | Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus | TTN |

| Cas3 | in silico analysis of various prokaryotic genomes | No PAM requirement |

The diversity of PAM requirements has significant implications for experimental design. When a target genomic locus lacks the preferred PAM for a given nuclease, researchers can select an alternative Cas protein with a compatible PAM [9]. Furthermore, protein engineering approaches have generated Cas variants with altered PAM specificities, including near-PAMless versions such as SpRY-Cas9, which dramatically expand the targetable genome [12].

Experimental Approaches for PAM Identification

Several methodological approaches have been developed to identify and characterize PAM sequences for both natural and engineered Cas nucleases. These techniques range from computational predictions to high-throughput experimental screens.

In Silico Prediction Methods

Initial PAM identification often relies on bioinformatic analysis of protospacer sequences adjacent to CRISPR spacers. Tools such as CRISPRTarget and CRISPRFinder can extract spacer sequences and identify conserved PAM motifs through alignment-based approaches [10]. While computationally efficient, these methods depend on the availability of sequenced phage genomes and cannot distinguish between spacer acquisition motifs (SAMs) and target interference motifs (TIMs) [10].

High-Throughput Experimental Screens

Several experimental approaches have been developed for comprehensive PAM characterization:

Plasmid Depletion Assays: These assays introduce randomized DNA stretches adjacent to target sequences within plasmids transformed into hosts with active CRISPR-Cas systems. Plasmids with "inactive" PAMs are retained and identified via next-generation sequencing, revealing functional PAM elements through depletion patterns [10].

PAM-SCANR (PAM Screen Achieved by NOT-gate Repression): This high-throughput in vivo method utilizes catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a repressor domain. When dCas9 binds to a functional PAM, it represses GFP expression. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), plasmid purification, and sequencing then identify functional PAM motifs [10].

In Vitro Cleavage Assays: These approaches use purified Cas effector complexes to cleave DNA libraries containing randomized PAM sequences. Positive screening sequences enriched cleavage products, while negative screening sequences all remaining uncleaved targets [10]. These methods allow for larger library coverage and better control over reaction conditions but require purified, stable effector complexes [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for PAM Identification. This flowchart illustrates the major approaches for determining PAM specificity, combining computational and experimental methods.

PAM Engineering and PAMless Variants

Recent protein engineering efforts have focused on reducing PAM restrictions to expand the targetable genome. Directed evolution and structure-based engineering have produced Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities, with SpRY-Cas9 representing the most promiscuous variant [12].

SpRY-Cas9 contains multiple mutations (R1333P, R1335Q, A61R, L1111R, D1135L, S1136W, G1218K, E1219Q, N1317R, A1322R, and T1337R) that collectively enable recognition of virtually any PAM sequence [12]. Structural analyses reveal that SpRY achieves PAM flexibility through conformational adaptability within its PAM-interacting region, forming non-specific electrostatic interactions with the DNA backbone rather than specific base contacts [12].

However, this PAM flexibility comes with functional trade-offs. Single-molecule studies demonstrate that while SpRY binds target sequences with similar affinity to wild-type Cas9, it exhibits prolonged binding to off-target sites, resulting in slower target identification and increased potential for off-target effects [12]. The mechanism of PAMless recognition involves:

- Backbone interactions: SpRY forms extensive non-specific contacts with the phosphodiester backbone of target DNA

- Conformational flexibility: Solvent-exposed residues adopt different rotamers to accommodate diverse PAM sequences

- Reduced interrogation speed: SpRY cleaves target DNA approximately 1000-fold slower than wild-type Cas9

Research Reagent Solutions for PAM Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating PAM Recognition

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 Nuclease | Gold standard for PAM recognition studies | Requires 5'-NGG-3' PAM; widely characterized |

| SpRY-Cas9 | Near-PAMless variant for expanded targeting | Useful when target lacks canonical PAM; higher off-target potential |

| PAM-SCANR System | High-throughput PAM identification | Enables comprehensive PAM profiling in vivo |

| dCas9 Variants | Catalytically inactive Cas9 for binding studies | Useful for visualizing target search without cleavage |

| Structural Biology Tools | Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography | Elucidate molecular mechanisms of PAM recognition |

| Single-Molecule Imaging | DNA curtains, fluorescence microscopy | Visualize real-time target search and binding dynamics |

Clinical Implications and Safety Considerations

PAM recognition has direct implications for therapeutic genome editing applications. While relaxing PAM requirements expands potential therapeutic targets, it also introduces safety considerations. Off-target effects remain a primary concern for clinical translation, as Cas9 can tolerate mismatches between the guide RNA and DNA target, particularly in PAM-distal regions [13].

Recent studies have revealed that CRISPR editing can induce large structural variations (SVs), including chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions, beyond the well-characterized small indels [14]. These SVs raise substantial safety concerns for clinical applications and highlight the importance of comprehensive off-target assessment [14].

Strategies to mitigate off-target effects while maintaining efficient on-target editing include:

- High-fidelity Cas variants: Engineered Cas9 variants with enhanced specificity, such as HiFi Cas9 [13]

- Paired nickase systems: Using two Cas9 nickases to create adjacent single-strand breaks instead of a DSB [13]

- Computational guide design: Careful selection of guide sequences with minimal off-target potential using tools like Cas-OFFinder [13]

- Delivery optimization: Controlling Cas9 expression levels and duration to limit off-target exposure [8]

The ongoing clinical development of CRISPR-based therapies, including the recently approved Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, underscores the critical importance of understanding PAM recognition and its relationship to editing specificity [8] [15]. As of February 2025, over 150 active clinical trials are investigating CRISPR-based therapies across numerous disease areas, making the optimization of PAM recognition and target specificity more relevant than ever [15].

PAM recognition represents the critical initial step in CRISPR-mediated genome editing, serving as the gateway to target site specificity. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying PAM binding, the diversity of PAM requirements across Cas nucleases, and the experimental approaches for characterizing PAM interactions provides researchers with the foundation necessary for designing precise genome editing experiments. While recent engineering efforts have created Cas variants with relaxed PAM requirements, these advances come with trade-offs in specificity and kinetics that must be carefully considered in both basic research and therapeutic applications. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, the relationship between PAM recognition and editing outcomes will remain a central consideration for achieving specific and safe genome modification.

DNA interrogation represents the critical initial phase in the CRISPR-Cas mediated genome editing workflow, during which the Cas nuclease identifies and verifies its target DNA sequence prior to cleavage. This process encompasses two fundamental steps: protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) recognition and DNA unwinding to facilitate guide RNA-DNA hybridization, culminating in the formation of a three-stranded structure known as the R-loop [16] [17]. The efficiency and fidelity of this interrogation process directly determine the overall success and specificity of subsequent genome editing outcomes. Within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism research, understanding DNA interrogation is paramount for elucidating how double-strand breaks are initiated and controlled. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the molecular mechanics underlying DNA interrogation, synthesizing recent structural and biophysical findings to present a coherent model of target recognition from initial scanning to stable R-loop formation, with particular emphasis on implications for double-strand break formation research.

Molecular Mechanics of Target Recognition

PAM Recognition and Specificity

The CRISPR-Cas system initiates DNA interrogation through identification of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) flanking the target sequence. This step serves as an essential initial checkpoint that distinguishes self from non-self DNA, thereby preventing autoimmune targeting of the bacterial CRISPR locus [17] [18]. For Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpyCas9), the most extensively characterized Cas nuclease, the PAM sequence consists of a 5'-NGG-3' motif, where "N" represents any nucleotide [17]. PAM recognition is mediated through specific protein-DNA interactions that trigger conformational changes in the Cas complex, priming it for subsequent DNA unwinding.

Recent research reveals a fundamental trade-off between PAM-binding specificity and genome-editing efficiency. SpyCas9 variants with reduced PAM specificity demonstrate persistent non-selective DNA binding and recurrent failures to engage target sequences through stable guide RNA hybridization, ultimately leading to reduced editing efficiency in cellular environments [16]. This suggests that efficient editing is favored by specific yet weak PAM binding coupled with rapid DNA unwinding, rather than broad PAM recognition capabilities [16].

Table 1: PAM Requirements and Recognition Mechanisms Across CRISPR Systems

| CRISPR System | PAM Sequence | Recognition Mechanism | Specificity Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpyCas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Protein-DNA interactions via PI domain | High specificity required for efficient editing |

| Cas12a | 5'-TTTN-3' | Protein-DNA interactions | T-rich PAM enables targeting of distinct genomic regions |

| Type I-E Systems | Promiscuous recognition | Multi-subunit Cascade complex | Broader PAM recognition with reduced specificity |

DNA Unwinding and R-loop Formation Trajectory

Following PAM recognition, Cas nucleases initiate DNA unwinding to permit guide RNA hybridization with the target DNA strand. This process proceeds through a defined sequence of intermediates that have been characterized through sophisticated biophysical techniques. Single-molecule torque spectroscopy studies reveal that Cas12a orthologs engage target DNA through a multi-step pathway marked by distinct REC domain arrangements [19] [20].

The R-loop formation initiates with the generation of a seed bubble at the PAM-proximal region, involving unwinding of approximately 11 base pairs of dsDNA to scout for sequence complementarity [18]. This is followed by directional propagation of the R-loop toward the PAM-distal end, ultimately resulting in a full R-loop structure where approximately 20 base pairs of the guide RNA-DNA heteroduplex are formed [18]. Throughout this process, the non-target DNA strand is displaced, creating the characteristic three-stranded R-loop structure.

High-resolution structural studies of Type I-E Cascade systems reveal that PAM recognition induces severe DNA bending, leading to spontaneous DNA unwinding that nucleates from the seed sequence [18]. Cryo-EM snapshots of Thermobifida fusca Type I-E Cascade captured at different stages of R-loop formation show that initial PAM binding causes DNA bending, which in turn facilitates spontaneous DNA unwinding to form the seed-bubble intermediate [18].

Comparative Analysis of Cas9 and Cas12a Interrogation Mechanisms

Kinetic Intermediates and Conformational Transitions

The DNA interrogation pathways of Cas9 and Cas12a, while sharing fundamental similarities, exhibit distinct kinetic intermediates and conformational transitions. Single-molecule studies utilizing gold rotor bead tracking (AuRBT) have enabled direct observation of these intermediates at base-pair resolution under biologically relevant supercoiling conditions [19].

For Cas9, R-loop formation proceeds through a discrete intermediate corresponding to its approximately 9 bp seed region, with DNA supercoiling strongly modulating activity and specificity by controlling R-loop dynamics [19]. In contrast, Cas12a exhibits a more complex multi-step pathway with distinct intermediates, including a ~5 bp seed intermediate and a ~17 bp intermediate that likely represents a pre-cleavage conformation [19]. These intermediates display ortholog-dependent characteristics, with Acidaminococcus sp. Cas12a (AsCas12a) showing clear dwells in the ~5 bp intermediate during R-loop formation and collapse, a feature not observed in Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a) under identical conditions [19].

Table 2: Kinetic Intermediates in Cas9 and Cas12a R-loop Formation

| Parameter | Cas9 | Cas12a |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Intermediate Size | ~9 bp | ~5 bp |

| Secondary Intermediate | Not observed | ~17 bp |

| Downstream Unwinding | Limited | Transient "breathing" beyond R-loop |

| Supercoiling Sensitivity | High | Ortholog-dependent |

| Mismatch Tolerance | Increased on underwound DNA | Varies by ortholog |

Structural Determinants of Interrogation Fidelity

The structural features governing DNA interrogation fidelity differ significantly between Cas9 and Cas12a systems. Cas12a possesses dramatic domain flexibility that limits protein-DNA contacts until nearly complete R-loop formation, with distinct REC domain arrangements marking stages of R-loop formation [20]. This flexibility prevents premature nuclease activation, as the non-target strand is only pulled across the RuvC nuclease when domain docking occurs after extensive R-loop formation [20].

For Cas9, the two-step target capture mechanism involves initial PAM binding followed by DNA unwinding, with the balance between these steps crucial for editing efficiency [16]. Reduced PAM specificity creates kinetic traps that slow both target search and unwinding dynamics, ultimately diminishing genome-editing efficiency [16]. This mechanistic understanding has led to engineering strategies aimed at optimizing the two-step process for enhanced editing performance.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying DNA Interrogation

Single-Molecule Biophysical Approaches

Advanced single-molecule techniques have revolutionized our ability to probe DNA interrogation dynamics with unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution. Gold rotor bead tracking (AuRBT), a derivative of magnetic tweezers, enables direct measurement of R-loop formation at base-pair resolution under controlled DNA supercoiling conditions [19]. This methodology involves constraining a DNA tether containing a PAM and target sequence between a cover glass and a paramagnetic bead, while a gold nanoparticle attached to the DNA side is tracked at high speed to measure torque and twist changes associated with R-loop formation [19].

Single-molecule FRET (smFRET) provides complementary insights into conformational dynamics during DNA interrogation, particularly through monitoring distance changes between fluorescently labeled protein and DNA components. When combined with magnetic tweezers, these approaches can simulate cellular environments by applying supercoiling to DNA targets, replicating the topological stress encountered in physiological conditions [19]. The experimental workflow typically involves:

- DNA construct preparation with target sequences and flanking handles for attachment

- Surface immobilization of DNA molecules in flow chambers

- Protein and guide RNA introduction under controlled buffer conditions

- Data acquisition during supercoiling cycles to induce R-loop formation and collapse

- Change-point analysis to identify discrete transitions between interrogation states

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Single-Molecule DNA Interrogation Studies

Structural Biology Techniques

High-resolution structural biology methods have provided invaluable insights into the molecular architecture of CRISPR-DNA complexes during interrogation. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a particularly powerful approach, enabling visualization of transient intermediates along the R-loop formation pathway [18] [20]. Recent advances in cryo-EM have allowed researchers to capture wild-type Cas12a at various stages of R-loop formation and DNA delivery into the RuvC active site, revealing how domain flexibility guides the interrogation process [20].

The standard protocol for structural studies of DNA interrogation includes:

- Complex reconstitution by incubating Cas protein, guide RNA, and target DNA

- Vitrification through rapid freezing in liquid ethane

- Data collection using high-end cryo-electron microscopes

- Image processing and 3D reconstruction

- Model building and refinement into density maps

These structural approaches have revealed that Cas12a R-loop formation initiates from a 5-bp seed, with distinct REC domain arrangements marking progressive stages of R-loop formation [20]. Similarly, studies of Type I-E Cascade have captured structural snapshots of seed-bubble formation and full R-loop assembly, providing temporal and spatial resolution of key mechanistic steps [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Interrogation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9/dCas12a (Nuclease-deficient) | Enables R-loop studies without cleavage | Permits long, repeated measurements on single DNA molecules |

| Site-specifically labeled DNA constructs | Single-molecule visualization | Typically includes biotin/ligand handles for surface attachment |

| Gold nanoparticles (for AuRBT) | Torque and twist measurement | ~100nm particles attached to DNA for high-resolution tracking |

| Modified guide RNAs (fluorescently labeled) | FRET-based conformational monitoring | Fluorophore positioning critical for signal optimization |

| Supercoiled DNA substrates | Mimicking cellular DNA topology | Prepared through ligation and enzyme treatment |

| UMI-DSBseq toolkit | Quantifying DSB intermediates and repair products | Enables single-molecule resolution of repair dynamics [6] |

Implications for Double-Strand Break Formation Research

The mechanistic insights gleaned from DNA interrogation studies have profound implications for understanding and controlling double-strand break formation in CRISPR-based applications. Recent research utilizing the UMI-DSBseq toolkit for multiplexed quantification of DSB intermediates and repair products has revealed that 64-88% of target molecules are cleaved across three endogenous loci analyzed in tomato protoplasts, while indels resulting from error-prone repair ranged between 15-41% [6]. This significant discrepancy between cleavage and mutagenic repair rates highlights the substantial role of precise repair in determining final editing outcomes.

Kinetic modeling of DSB induction and repair dynamics suggests that indel accumulation is determined by the combined effect of DSB induction rates, processing of broken ends, and the balance between precise versus error-prone repair [6]. Precise repair accounts for most of the gap between cleavage and error repair, representing up to 70% of all repair events at certain targets [6]. These findings underscore how the fidelity of DNA interrogation and subsequent repair processes collectively shape the efficiency of CRISPR-mediated mutagenesis.

The influence of cellular factors on DSB repair further modulates editing outcomes. PARP1, a key DNA damage response protein, has been identified as a significant regulator of repair pathway choice following CRISPR-Cas9 induced DSBs [21]. PARP1 downregulation increases both NHEJ and MMEJ repair without altering homologous recombination, while PARP1 overexpression reduces NHEJ and HR efficiency [21]. This suggests that targeted modulation of DNA repair factors could provide a strategy for biasing DSB repair outcomes toward more predictable or precise edits.

DNA interrogation represents a sophisticated molecular process that governs the specificity and efficiency of CRISPR-mediated genome editing. The two-step mechanism of PAM recognition followed by directional R-loop formation through discrete intermediates ensures targeted DNA binding, while conformational transitions in Cas nucleases license subsequent nuclease activation. Single-molecule biophysical approaches and high-resolution structural biology have collectively illuminated the dynamic nature of this process, revealing how kinetic intermediates and cellular factors influence editing outcomes. Understanding DNA interrogation mechanics provides a fundamental framework for developing next-generation CRISPR tools with enhanced precision and efficacy, particularly for therapeutic applications requiring predictable double-strand break formation and repair. As research in this field advances, continued refinement of our DNA interrogation models will undoubtedly yield new insights into the complex interplay between target recognition, cleavage activation, and DNA repair in diverse genomic contexts.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has emerged as a revolutionary tool for genome editing, with its core functionality relying on the formation of precise double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA. The Cas9 endonuclease achieves this through the coordinated action of two distinct nuclease domains: the HNH and RuvC-like domains [22]. These domains operate via different mechanistic principles to cleave the two strands of the target DNA. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide sequence, while the RuvC-like domain cleaves the non-complementary strand [22] [23]. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms of these domains is fundamental to advancing CRISPR-based research and therapeutic applications, as it informs the development of more precise editing tools and helps mitigate challenges such as off-target effects.

Molecular Mechanisms of the HNH and RuvC Nuclease Domains

The HNH Nuclease Domain

The HNH domain is characterized by a ββα-metal fold and is responsible for cleaving the crRNA-complementary strand of the target DNA. This domain functions through a fixed-position cleavage mechanism [22]. Structural studies indicate that the HNH domain undergoes a large conformational rearrangement upon target DNA binding, positioning itself to catalyze cleavage at a specific phosphodiester bond located 3 base pairs upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [22]. The catalytic core of the HNH domain typically contains conserved histidine and asparagine residues that coordinate a metal ion (most commonly Mg²⁺) essential for hydrolyzing the DNA backbone [24].

The RuvC-like Nuclease Domain

The RuvC-like domain, which shares structural homology with the RNase H superfamily of nucleases, cleaves the DNA strand non-complementary to the crRNA. In contrast to the HNH domain, it employs a ruler-based cleavage mechanism [22]. This domain measures a fixed distance from the PAM sequence to determine its cleavage site, typically resulting in a cut 3-8 nucleotides upstream of the PAM [22]. The RuvC active site utilizes a DED catalytic motif that coordinates two metal ions to facilitate DNA cleavage, a mechanism conserved across the RNase H superfamily [25] [26].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of HNH and RuvC Nuclease Domains in Cas9

| Feature | HNH Domain | RuvC-like Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Origin | Widespread nuclease family found in colicins, homing endonucleases, and phage packaging proteins (e.g., HK97 gp74) [24] | Bacterial resolvase involved in Holliday junction resolution during DNA repair [25] |

| Primary Function in Cas9 | Cleaves the target DNA strand complementary to the crRNA guide sequence [22] | Cleaves the target DNA strand non-complementary to the crRNA guide sequence [22] |

| Cleavage Mechanism | Fixed position relative to the PAM sequence [22] | Ruler mechanism measuring distance from the PAM [22] |

| Catalytic Motif/Residues | Conserved His and Asn residues [24] | DED catalytic motif (Asp, Glu, Asp) [25] [26] |

| Metal Cofactor Dependence | Mg²⁺ dependent [22] | Mg²⁺ dependent [22] [26] |

| Key Structural Insight | Undergoes major conformational activation upon target binding [22] | Functions as a dimer; achieves sequence specificity through dynamic DNA probing [26] |

Experimental Characterization of Cleavage Mechanisms

In Vitro Cleavage Assays for Mechanism Determination

The distinct cleavage mechanisms of the HNH and RuvC domains were elucidated through carefully designed in vitro cleavage assays.

Protocol for In Vitro DNA Cleavage Assay (adapted from [22])

- Protein Purification: Express and purify recombinant Cas9 protein (e.g., from Streptococcus thermophilus LMG18311) using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- RNA Preparation: Generate single guide RNA (sgRNA) or crRNA/tracrRNA complexes via in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and subsequent gel purification.

- Assay Setup: Reconstitute the cleavage reaction by incubating purified Cas9 (e.g., 5 µM) with the guide RNA and a target DNA plasmid containing the protospacer and a cognate PAM sequence in an appropriate reaction buffer.

- Mutagenesis Analysis: To assign cleavage activity to specific domains, generate and purify catalytic dead mutants (e.g., HNH mutant H825A or RuvC mutant D15A) and repeat the assay. The loss of specific strand cleavage implicates the mutated domain.

- Product Analysis: Resolve the reaction products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Successful cleavage of the target plasmid will generate two smaller, quantifiable DNA fragments.

Structural Analysis of RuvC's Sequence Specificity

The sequence preference of the ancestral RuvC resolvase (for the consensus 5'-A/TTT↓G/C-3') provides a model for understanding nuclease specificity. Biochemical and structural studies, including X-ray crystallography and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, reveal that RuvC does not make direct base-specific contacts. Instead, it achieves specificity through a dynamic probing mechanism [26].

Key Experimental Workflow for RuvC HJ Resolution [26]

- Crystallization: Co-crystallize RuvC with a synthetic Holliday junction (HJ) DNA substrate.

- Data Collection & Structure Solution: Collect X-ray diffraction data and solve the structure of the RuvC-HJ complex.

- MD Simulations: Perform microsecond-scale MD simulations on the solved structure, replacing non-cognate DNA sequences with cognate ones to observe conformational changes.

- Biochemical Validation: Test predictions from the MD simulations (e.g., the role of specific residues like Arg76 in base flipping) using site-directed mutagenesis and in vitro cleavage assays with cognate versus non-cognate HJ substrates.

This combined approach revealed that RuvC induces strain at the HJ exchange point. For cognate sequences, the complex can access rare, high-energy states where a specific thymidine base flips out, allowing the scissile phosphate to move into the catalytic site. This conformational change is less feasible for non-cognate sequences, providing a kinetic barrier that ensures cleavage specificity [26].

Diagram 1: HNH and RuvC-like domain cleavage mechanisms leading to DSB formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Nuclease Mechanism Studies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying HNH and RuvC Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Dead Mutants | Assigns cleavage activity to a specific nuclease domain by ablating its function. | HNH mutant (e.g., H840A in SpCas9), RuvC mutant (e.g., D10A in SpCas9). Used in in vitro cleavage assays [22]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Orthologs | Comparative studies of cleavage mechanics and PAM requirements across different systems. | Streptococcus thermophilus LMG18311 Cas9, with distinct PAM specificity [22]. |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA/crRNA) | Directs Cas9 to a specific DNA target sequence for cleavage. | Designed as a ~20 nt sequence complementary to the target; can be produced by in vitro transcription [22] [23]. |

| Synthetic Holliday Junctions (HJs) | Substrate for studying the mechanism and specificity of ancestral RuvC resolvase. | Synthetic four-way DNA junctions with cognate (5'-A/TTT↓G/C-3') or non-cognate sequences for in vitro assays [26]. |

| Divalent Metal Cofactors | Essential catalytic cofactor for both HNH and RuvC-like nuclease activities. | Mg²⁺ is the primary physiological cofactor; required in reaction buffers for cleavage assays [22] [26]. |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Research

The detailed mechanistic understanding of HNH and RuvC domains directly fuels advances in CRISPR-based therapeutic development. The ability to create nickase variants (e.g., Cas9n, where one domain is inactivated) enables single-strand breaks for more precise editing with reduced off-target effects [23] [27]. Furthermore, this knowledge underpins the engineering of high-fidelity Cas9 variants and novel editors like prime editors, which bypass DSB formation altogether, thereby enhancing safety profiles for clinical applications [28] [29].

In drug discovery and functional genomics, CRISPR-Cas9 is instrumental for high-throughput screens to identify and validate new drug targets [30] [23] [29]. The precision of the dual nuclease system allows for the creation of more accurate disease models and the development of cell-based therapies, such as engineered CAR-T cells where specific genes are knocked out to enhance anti-tumor activity [23] [31]. A novel therapeutic approach involves weaponizing Cas9 to induce lethal DSBs specifically in aberrant cells (e.g., cancer cells or those harboring silent viral DNA) based on their unique DNA sequences, a strategy that is independent of gene expression or function [27].

Diagram 2: From mechanistic insight to application in research and therapy.

Structural Conformational Changes Driving the DNA Cleavage Process

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genome engineering by providing unprecedented precision in manipulating DNA sequences. At the heart of this technology lies the Cas9 endonuclease, which undergoes a series of sophisticated structural rearrangements to execute DNA cleavage. These conformational changes represent a critical regulatory mechanism that ensures the specificity of DNA targeting and cleavage, forming the foundation for reliable genome editing applications in therapeutic development [28].

This technical guide examines the structural basis of Cas9 activation, focusing on the dynamic transitions that enable the formation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism research, understanding these conformational changes is paramount for optimizing editing efficiency and specificity, particularly for drug development applications where off-target effects present significant safety concerns [32]. The precise molecular choreography between Cas9's domains serves as a final proofreading step before irreversible DNA cleavage occurs, making it a fundamental process for researchers to comprehend [33].

Structural Fundamentals of the Cas9 Enzyme

The Cas9 enzyme possesses a bilobed architecture consisting of two primary structural elements: the recognition (REC) lobe and the nuclease (NUC) lobe. The REC lobe, composed of REC1, REC2, and REC3 domains, is responsible for nucleic acid binding and recognition. The NUC lobe contains the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains that perform the DNA cleavage activity [34] [32].

Cas9 operates as an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease that requires a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for sequence-specific targeting. The sgRNA directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which is essential for initial DNA recognition [32]. Upon PAM binding, Cas9 initiates DNA unwinding, allowing the guide RNA to form a heteroduplex with the target DNA strand (TS), while displacing the non-target strand (NTS) [34].

The catalytic heart of Cas9 resides in its two nuclease domains: HNH cleaves the TS complementary to the sgRNA, while RuvC cleaves the NTS. These domains are spatially separated in the inactive state but undergo substantial repositioning to achieve catalytic competence [35]. The HNH domain exhibits remarkable conformational flexibility, sampling multiple states before adopting the active configuration necessary for DNA cleavage [36].

Table 1: Key Domains and Structural Elements of Cas9

| Domain/Element | Function | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| REC Lobe | Guide RNA and target DNA binding | Comprises REC1, REC2, REC3 domains; facilitates nucleic acid recognition |

| HNH Domain | Cleaves target DNA strand | Exhibits high conformational flexibility; contains catalytic residue H840 |

| RuvC Domain | Cleaves non-target DNA strand | Maintains relatively stable position; contains catalytic residue D10 |

| PAM Interface | Initial DNA recognition | Recognizes NGG sequence; allosterically activates nuclease domains |

| L1/L2 Linkers | Signal transduction | Connects structural elements; mediates allosteric communication |

Conformational States During DNA Cleavage Activation

Sequential Activation of the HNH Domain

The HNH domain undergoes a precisely orchestrated conformational transition to activate DNA cleavage. Structural studies have revealed at least three distinct states during this process. In the HNH-state 1 (inactive conformation), the HNH active site is positioned more than 32 Å from the DNA cleavage site, rendering it catalytically incompetent. In the intermediate HNH-state 2, the domain moves closer, but the catalytic site remains approximately 19 Å from the scissile phosphorus. Finally, in HNH-state 3 (active conformation), the HNH domain rotates approximately 170° around a central axis, bringing its active site to the optimal position for DNA cleavage [35].

This transition involves substantial structural rearrangements beyond simple translation. The linker region L2 (residues 906-923) undergoes a helix-to-loop conformational change that facilitates the dramatic reorientation of HNH. In the active state, the HNH domain establishes new contacts with the REC1 and PI domains through segments comprising residues 861-864, 872-876, and 903-906 [35]. These interactions stabilize the domain in its catalytically competent configuration.

Allosteric Coordination Between Nuclease Domains

The cleavage of both DNA strands is tightly coordinated through allosteric communication between the HNH and RuvC domains. The HNH domain serves as an allosteric regulator of RuvC activity—only when HNH adopts its active conformation does RuvC become fully capable of cleaving the NTS [33]. This mechanism ensures concerted firing of both nuclease domains, preventing single-strand nicks unless both domains are properly positioned.

Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that the L1 and L2 loops function as critical "signal transducers" in this allosteric network [32]. PAM binding initiates a population shift that propagates through these structural elements, inducing highly coupled motions of HNH and RuvC. This allosteric cross-talk creates a proofreading mechanism that verifies correct target recognition before permitting irreversible DNA cleavage [32].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of HNH Conformational States

| HNH State | Distance from Cleavage Site | Domain Rotation | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| State 1 (Inactive) | >32 Å | Reference state | Crystallographic state; HNH distal from DNA |

| State 2 (Intermediate) | ~19 Å | Partial rotation | Closer approach; not fully activated |

| State 3 (Active) | Catalytic distance | ~170° rotation | Contacts REC1 and PI domains; L2 linker in loop conformation |

Experimental Characterization of Conformational Dynamics

Cryo-Electron Microscopy Approaches

Cryo-EM has been instrumental in visualizing Cas9 conformational states at near-atomic resolution. A landmark 5.2 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of the Cas9-sgRNA-DNA ternary complex revealed the HNH domain in its active conformation (State 3), providing the first structural evidence of its repositioning for catalysis [35].

Experimental Protocol: Cryo-EM Structure Determination

- Complex Preparation: Incubate Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) with nuclease activity-dead mutations (D10A, H840A) with a 55-bp target DNA and corresponding 98-nt sgRNA to form a stable ternary complex

- Vitrification: Rapidly freeze the complex on cryo-EM grids to preserve native structure

- Data Collection: Acquire multiple micrographs using cryo-electron microscope

- 2D Classification: Identify and group similar particle images

- 3D Reconstruction: Apply single-particle analysis to generate initial density map

- Refinement: Iteratively refine the model against the density map to achieve final resolution [35]

This approach successfully captured the PAM-proximal region in a stable, base-paired form, while the PAM-distal end appeared more flexible, suggesting dynamic behavior during R-loop formation [35].

Single-Molecule FRET Methodologies

Single-molecule FRET (smFRET) has provided unprecedented insights into the real-time dynamics of Cas9 conformational changes. By site-specifically labeling Cas9 with donor and acceptor fluorophores, researchers have monitored domain movements under various binding conditions [33] [36].

Experimental Protocol: smFRET for HNH Conformational Monitoring

- Protein Engineering: Introduce cysteine residues at strategic positions (e.g., S355-S867 or S867-N1054) in a cysteine-free Cas9 background for specific dye labeling

- Fluorophore Conjugation: Label engineered cysteines with Cy3 (donor) and Cy5 (acceptor) maleimide dyes

- Complex Formation: Incubate labeled Cas9 with sgRNA and various DNA substrates (on-target, off-target, or mismatched)

- FRET Measurements: Monitor energy transfer efficiency between fluorophores using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy

- Data Analysis: Calculate (ratio)A values (acceptor fluorescence via energy transfer normalized to direct excitation) to quantify conformational states [33]

This methodology revealed that the HNH domain samples an equilibrium between active and inactive conformations, with on-target DNA stabilizing the active state and off-target substrates favoring inactive conformations [33]. The measured FRET efficiencies directly correlated with DNA cleavage activities, establishing a quantitative relationship between HNH positioning and catalytic function.

Diagram 1: smFRET Experimental Workflow for Cas9 Conformational Analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Computational approaches have complemented experimental methods in characterizing Cas9 conformational dynamics. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, particularly Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD), have enabled the exploration of large-scale transitions occurring on microsecond to millisecond timescales [32].

Computational Protocol: Enhanced Sampling MD Simulations

- System Preparation: Construct atomic models of Cas9 in various ligand-bound states using available crystal structures

- Solvation and Ionization: Embed the protein in explicit solvent with physiological ion concentrations

- Equilibration: Gradually relax the system through restrained and unrestrained MD simulations

- Enhanced Sampling: Apply GaMD methods to overcome energy barriers and observe rare transitions

- Pathway Analysis: Identify intermediate states and conformational pathways using dimensionality reduction techniques

- Validation: Compare simulated conformations with experimental structures and FRET data [32]

These simulations have predicted the existence of an active HNH conformation that was later confirmed experimentally, demonstrating the predictive power of modern computational approaches [32]. MD simulations have also revealed large-scale movements of the REC lobe (Rec2 domain translation of ~8-10 Å, Rec3 translation of ~5 Å) that accommodate HNH docking at the catalytic site [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Cas9 Conformational Changes

| Reagent/Method | Specific Application | Key Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Specificity studies | Reduced off-target cleavage; point mutations in REC3 or RuvC domains | Examples: eCas9, HypaCas9, evoCas9; maintain on-target efficiency |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Cas9 | smFRET experiments | Site-specific labeling for distance measurements | Cysteine-free background required; confirm functional activity post-labeling |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Structural studies | Vitrification of ternary complexes | Optimize freezing conditions to preserve native state |

| Modified DNA Substrates | Cleavage kinetics | On-target, off-target, and mismatched sequences | Design includes PAM and variable complementarity regions |

| MD Simulation Software | Computational modeling | All-atom dynamics with enhanced sampling | Requires significant computational resources; validate with experimental data |

Implications for Therapeutic Genome Editing

Understanding Cas9 conformational dynamics has direct implications for therapeutic genome editing applications. The proofreading mechanism mediated by HNH dynamics serves as a natural barrier against off-target effects, a major concern in clinical applications [33] [36]. Engineering efforts have leveraged this knowledge to develop high-fidelity Cas9 variants with improved specificity profiles.

The allosteric communication between Cas9 domains presents opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Small molecules that modulate these allosteric pathways could potentially fine-tune Cas9 activity, offering additional control over genome editing outcomes [32]. Additionally, the conformational checkpoint mechanism could be exploited to develop novel genome editing platforms with built-in safety features.

Recent research has also demonstrated the potential for weaponizing CRISPR/Cas9 to selectively eliminate aberrant cells by targeting genomic sequences unique to cancer cells or viral pathogens [27]. This approach leverages the precise DNA recognition and cleavage capabilities of Cas9, while understanding conformational dynamics ensures selective targeting without affecting healthy cells.

Diagram 2: Cas9 Conformational Activation Pathway for DNA Cleavage

The structural conformational changes driving DNA cleavage in CRISPR-Cas9 represent a sophisticated molecular mechanism that balances catalytic efficiency with target specificity. The dynamic transitions of the HNH domain, coupled with allosteric regulation of RuvC activity, create a proofreading system that verifies correct target recognition before permitting DNA cleavage. This understanding has enabled the development of improved genome editing tools with enhanced specificity profiles.

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these conformational dynamics is essential for advancing CRISPR-based therapeutic applications. The experimental and computational methodologies reviewed here provide a toolkit for investigating these processes, while engineered Cas9 variants offer improved platforms for precise genome manipulation. As structural biology techniques continue to evolve, particularly in cryo-EM and single-molecule imaging, our understanding of these fundamental processes will further refine the safety and efficacy of genome editing technologies for clinical applications.

From Mechanism to Medicine: Therapeutic Applications of CRISPR-Induced DSBs

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by providing unprecedented precision in genome editing. However, a critical understanding often overlooked is that the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery itself does not perform the genetic modification but rather serves as "molecular scissors" that create a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA [37] [38]. The actual genetic editing occurs through the cell's endogenous DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways, which are activated to resolve this break [38]. Two principal pathways compete to repair these breaks: error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and high-fidelity Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [37] [28]. The fundamental choice between these pathways determines the editing outcome, making their manipulation essential for achieving predictable genetic modifications in CRISPR-based experiments. Within the broader context of DSB formation research, understanding and controlling these endogenous cellular processes is what transforms a simple DNA cut into a powerful tool for genetic engineering, with profound implications for basic research and therapeutic development.

DNA Repair Mechanism Fundamentals

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The Rapid Response Mechanism

Non-Homologous End Joining is the cell's primary, fast-acting mechanism for repairing DSBs. This pathway functions throughout the cell cycle and operates by directly ligating the two broken ends of the DNA double helix without requiring a homologous template [37] [38]. Its key characteristic is its error-prone nature; the rejoining process often results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site [38]. These INDELs typically range from 1 to 10 base pairs and can disrupt gene function by causing frameshift mutations, leading to premature stop codons and effectively knocking out the gene [38]. The distinguishing features of NHEJ are its speed, as it is the cell's first line of defense against DSBs; its template independence, functioning without a homologous DNA template; and its high efficiency across all phases of the cell cycle [38]. While NHEJ is ideal for gene knockouts, it can also be co-opted for gene knock-in strategies with appropriately designed donor templates, though with less precision than HDR-based approaches [37].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): The Precision Repair Pathway

Homology-Directed Repair represents a high-fidelity alternative to NHEJ. Unlike the template-independent NHEJ pathway, HDR requires a homologous DNA template—such as a sister chromatid, a donor plasmid, or a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN)—to accurately repair the DSB [37] [38]. This template-dependent mechanism allows for precise genetic modifications, including nucleotide substitutions, gene corrections, or the insertion of larger DNA fragments such as fluorescent protein tags [37]. However, HDR's defining features also present practical limitations. Its precision comes at the cost of lower efficiency compared to NHEJ, and it is cell cycle-dependent, occurring primarily during the S and G2 phases when homologous templates are available through DNA replication [38]. This pathway is consequently less efficient in non-dividing or slowly dividing cells, such as neurons or cardiomyocytes [39]. For researchers aiming to perform precise gene knock-ins, point mutations, or gene corrections, HDR is the indispensable pathway, despite requiring additional experimental strategies to enhance its efficiency.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of NHEJ and HDR Pathways

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No | Yes (donor DNA with homology arms) |

| Primary Outcome | Small insertions/deletions (INDELs) | Precise sequence insertion/correction |

| Efficiency | High | Low to moderate |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | Active throughout all phases | Restricted to S and G2 phases |

| Kinetics | Fast (hours) | Slow (hours to days) |

| Key Applications | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Gene knock-ins, precise point mutations, gene correction |

| Major Advantage | Highly efficient in most cell types | High precision and accuracy |

| Major Limitation | Error-prone, introduces random INDELs | Low efficiency, requires donor design |

Experimental Strategies and Methodologies

Designing Experiments for NHEJ-Mediated Gene Knockouts

To successfully implement NHEJ for gene knockout studies, researchers must follow a structured experimental approach. The essential components required are the Cas9 nuclease (delivered as protein, plasmid, or mRNA) and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) complexed with Cas9 [38]. The experimental workflow begins with the careful design of sgRNAs that target early exonic regions of the gene of interest to maximize the likelihood of generating frameshift mutations. After delivering these components into the target cells, the editing outcome must be validated. This is typically done by extracting genomic DNA and using PCR to amplify the target region, followed by sequencing analysis to detect the spectrum of INDELs introduced at the cut site [38]. The efficiency of gene disruption is often quantified using mismatch detection assays (e.g., T7E1 or Surveyor assays) or, more accurately, by high-throughput sequencing methods. A critical consideration is that traditional short-read sequencing may miss large, on-target deletions (kilobase- to megabase-scale) that have been recently identified as a common outcome of CRISPR editing [14]. These large structural variations (SVs) can have profound functional consequences but are often undetected by standard amplification and sequencing approaches if primer binding sites are lost [14].

Implementing HDR for Precise Genetic Modifications

The implementation of HDR requires more complex experimental design compared to NHEJ-based approaches. In addition to the Cas9 nuclease and sgRNA, HDR experiments necessitate the design and delivery of a donor DNA template containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms that match the sequences surrounding the cut site [37] [38]. The length of these homology arms varies depending on the application: for ssODN templates used to introduce point mutations or small insertions, arms of 30-60 nucleotides are typically sufficient, while for plasmid-based donors for larger insertions, arms of 500-1000 nucleotides are common. To maximize HDR efficiency, researchers often employ strategic interventions to shift the cellular repair balance away from the dominant NHEJ pathway. These include cell cycle synchronization to enrich for cells in S/G2 phase where HDR is active [38], and the use of small molecule inhibitors targeting key NHEJ proteins such as DNA-PKcs (e.g., NU7441, M3814) [14] [38]. However, recent studies have revealed that some enhancement strategies, particularly the use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors like AZD7648, can inadvertently increase the frequency of large-scale chromosomal aberrations and translocations [14]. This underscores the importance of comprehensive genotoxic profiling when developing therapeutic editing approaches.

Addressing Unique Challenges in Non-Dividing Cells

Recent research has highlighted significant differences in DNA repair dynamics between dividing and non-dividing cells, with important implications for therapeutic editing in postmitotic cells such as neurons and cardiomyocytes. A 2025 study comparing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and iPSC-derived neurons revealed that Cas9-induced indels accumulate over a significantly longer time course in neurons—continuing to increase for up to two weeks post-transduction, compared to a few days in dividing cells [39]. Furthermore, neurons exhibit a different distribution of repair outcomes, with a strong bias toward small NHEJ-mediated indels and a suppression of the larger deletions typically associated with microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) that are more common in dividing cells [39]. These findings necessitate adapted experimental timelines and analytical approaches when working with clinically relevant non-dividing cells.

Advanced Technical Considerations and Risk Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Repair Studies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Controlling and Assessing DNA Repair Outcomes

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors | DNA-PKcs inhibitors (NU7441, M3814), 53BP1 inhibitors | Enhance HDR efficiency by suppressing competing NHEJ pathway [14] [38] |

| HDR Donor Templates | Single-stranded ODNs (ssODNs), double-stranded DNA plasmids with homology arms | Provide template for precise repair; design depends on edit size [38] |

| Cell Synchronization Agents | Aphidicolin, Thymidine, Nocodazole | Enrich cell populations in S/G2 phase where HDR is active [38] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Virus-like particles (VLPs), Electroporation, Chemical transfection | Enable efficient RNP delivery, especially in challenging cells like neurons [39] |

| Analysis Tools | Amplicon sequencing, CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS | Detect editing outcomes and structural variations [14] |

Emerging Risks: Structural Variations and Genomic Instability

Beyond the well-documented concerns about off-target effects, recent studies have revealed more pressing challenges associated with CRISPR editing, particularly the formation of large structural variations (SVs) including chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions [14]. These SVs represent substantial safety concerns for clinical translation and are often underestimated in standard editing assessments. The risk of such events appears particularly elevated in cells treated with DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance HDR, where surveys have shown not only a qualitative rise in the number of translocation sites but also an alarming thousand-fold increase in the frequency of these SVs [14]. Additionally, techniques that rely on short-read sequencing can dramatically overestimate HDR efficiency while concurrently underestimating INDEL frequencies when large deletions remove primer binding sites, rendering these events 'invisible' to standard analysis [14]. These findings highlight the critical need for comprehensive SV screening using specialized methods like CAST-Seq or LAM-HTGTS in therapeutic editing applications [14].

Visualization of Repair Pathways and Experimental Workflows

CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Repair Pathway Logic

Experimental Workflow for CRISPR Repair Studies